How did COVID-19 affect Americans’ well-being and mental health?

Subscribe to global connection, emily dobson , emily dobson ph.d. student - university of maryland carol graham , carol graham senior fellow - economic studies @cgbrookings tim hua , and tim hua student - middlebury college, former intern - global economy and development sergio pinto sergio pinto doctoral student, university of maryland.

April 8, 2022

COVID-19 has justifiably raised widespread public concern about mental health worldwide. In the U.S., the pandemic was an unprecedented shock to society at a time when the nation was already coping with a crisis of despair and related deaths from suicides, overdoses, and alcohol poisoning. Meanwhile, COVID-19’s impact was inequitable: Deaths were concentrated among the elderly and minorities working in essential jobs, groups who up to the pandemic had been reporting better mental health. We still do not fully understand how the shock has affected society’s well-being and mental health.

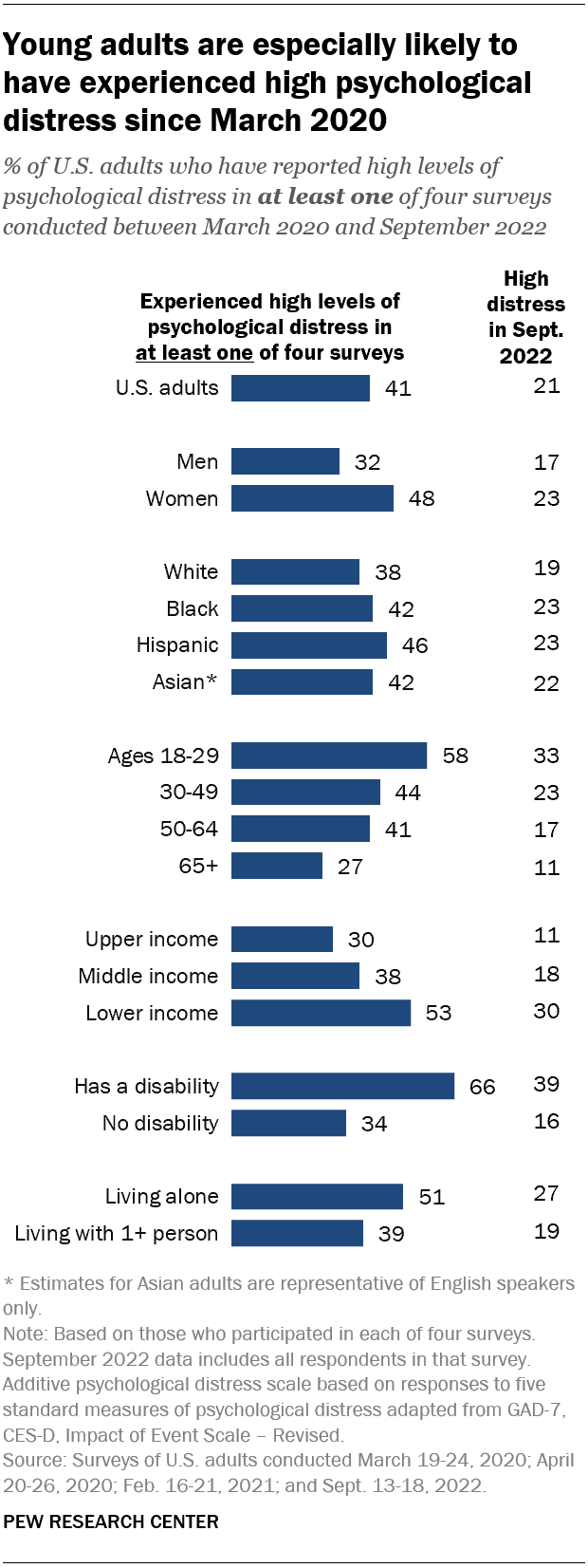

In a recent paper in which we compared trends in 2019-2020 using several nationally representative datasets, we found a variety of contrasting stories. While data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and the 2020 Household Pulse Survey (HPS) containing the same mental health screening questions for depression and anxiety show that both increased significantly, especially among young and low-income Americans in 2020, we found no such changes when analyzing alternative depression questions that are also asked in a consistent manner in the 2019-2020 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and the 2019-2020 NHIS. Despite the differences in trends, the basic determinants of mental health were similar in three data sets in the same two years.

Our findings raise questions about the robustness of the many studies claiming unprecedented increases in depression and anxiety among the young compared to older cohorts. Many of them, due to the urgency created by COVID-19 and a paucity of good, consistent data, matched datasets and used different questions therein in their attempt to identify changes in the trends between the two years. The inconsistency in the outcome changes over time across datasets points to the need for caution in drawing conclusions, as well as in relying too heavily on a single study; results generated from different data may differ considerably.

Given the paucity of comparable data and the usual one-year lag in the release of the final mortality data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), we also tried to get a handle on changes in patterns in mental health by examining emergency medical services (EMS) data calls related to behavior, overdoses, suicide attempts, and gun violence. The EMS data has the advantage of using the same methods and samples over the two-year period. We found an increase in gun violence and opioid overdose calls in 2020 after lockdowns, but surprisingly, a sharp decrease in behavioral health calls and no change in suicide-related EMS activations. The latter trend is a puzzle, but possible explanations include opioid overdose deaths increasing markedly and possibly substituting for suicide deaths. Alternatively, many older men—who are the demographic groups with the most suicide deaths—died of COVID-19 in that same period; another tragic “substitution” effect.

Finally, we looked at whether over the long run there is a relationship between poor mental health and later deaths of despair in micropolitan and metropolitan statistical areas (MMSAs). We found modest support for that possibility. Based on mental health reports in the BRFSS and CDC mortality data, we find that two-to-three-year-lagged bad mental health days (at the individual level) are associated with higher rates of deaths of despair (at the MMSA level), and that the two-to-four-year-lagged rates of deaths of despair are associated with a higher number of bad mental health days in later years. We cannot establish a direction of causality, but it is possible that there are vicious circles at play with individual trends in mental health contributing to broader community distress, and communities with more despair-related deaths likely to have more mental health problems later as a result.

Our analysis, based on many different datasets and indicators of despair, does not contradict other studies in that despair is an ongoing problem in the U.S., as reflected by both mental health reports and trends in EMS activations. However, we do find that the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are mixed, and that while some trends, such as opioid overdose deaths, worsened in 2020 compared to 2019, others, such as in some mental health reports and in suicide rates, improved slightly. Our work does not speak to the longer-term mental health consequences of the pandemic, but it does suggest that there were deep pockets of both despair and resilience throughout it. It also suggests that caution is necessary in drawing policy implications from any one study.

Related Content

Emily Dobson, Carol Graham, Tim Hua, Sergio Pinto

April 4, 2022

Carol Graham, Fred Dews

January 28, 2022

Related Books

Carol Graham

March 28, 2017

August 8, 2012

Global Economy and Development

Isabel V. Sawhill, Kai Smith

May 29, 2024

Harris A. Eyre, Carol Graham

January 3, 2022

- COVID-19 and your mental health

Worries and anxiety about COVID-19 can be overwhelming. Learn ways to cope as COVID-19 spreads.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, life for many people changed very quickly. Worry and concern were natural partners of all that change — getting used to new routines, loneliness and financial pressure, among other issues. Information overload, rumor and misinformation didn't help.

Worldwide surveys done in 2020 and 2021 found higher than typical levels of stress, insomnia, anxiety and depression. By 2022, levels had lowered but were still higher than before 2020.

Though feelings of distress about COVID-19 may come and go, they are still an issue for many people. You aren't alone if you feel distress due to COVID-19. And you're not alone if you've coped with the stress in less than healthy ways, such as substance use.

But healthier self-care choices can help you cope with COVID-19 or any other challenge you may face.

And knowing when to get help can be the most essential self-care action of all.

Recognize what's typical and what's not

Stress and worry are common during a crisis. But something like the COVID-19 pandemic can push people beyond their ability to cope.

In surveys, the most common symptoms reported were trouble sleeping and feeling anxiety or nervous. The number of people noting those symptoms went up and down in surveys given over time. Depression and loneliness were less common than nervousness or sleep problems, but more consistent across surveys given over time. Among adults, use of drugs, alcohol and other intoxicating substances has increased over time as well.

The first step is to notice how often you feel helpless, sad, angry, irritable, hopeless, anxious or afraid. Some people may feel numb.

Keep track of how often you have trouble focusing on daily tasks or doing routine chores. Are there things that you used to enjoy doing that you stopped doing because of how you feel? Note any big changes in appetite, any substance use, body aches and pains, and problems with sleep.

These feelings may come and go over time. But if these feelings don't go away or make it hard to do your daily tasks, it's time to ask for help.

Get help when you need it

If you're feeling suicidal or thinking of hurting yourself, seek help.

- Contact your healthcare professional or a mental health professional.

- Contact a suicide hotline. In the U.S., call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline , available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Or use the Lifeline Chat . Services are free and confidential.

If you are worried about yourself or someone else, contact your healthcare professional or mental health professional. Some may be able to see you in person or talk over the phone or online.

You also can reach out to a friend or loved one. Someone in your faith community also could help.

And you may be able to get counseling or a mental health appointment through an employer's employee assistance program.

Another option is information and treatment options from groups such as:

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Self-care tips

Some people may use unhealthy ways to cope with anxiety around COVID-19. These unhealthy choices may include things such as misuse of medicines or legal drugs and use of illegal drugs. Unhealthy coping choices also can be things such as sleeping too much or too little, or overeating. It also can include avoiding other people and focusing on only one soothing thing, such as work, television or gaming.

Unhealthy coping methods can worsen mental and physical health. And that is particularly true if you're trying to manage or recover from COVID-19.

Self-care actions can help you restore a healthy balance in your life. They can lessen everyday stress or significant anxiety linked to events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Self-care actions give your body and mind a chance to heal from the problems long-term stress can cause.

Take care of your body

Healthy self-care tips start with the basics. Give your body what it needs and avoid what it doesn't need. Some tips are:

- Get the right amount of sleep for you. A regular sleep schedule, when you go to bed and get up at similar times each day, can help avoid sleep problems.

- Move your body. Regular physical activity and exercise can help reduce anxiety and improve mood. Any activity you can do regularly is a good choice. That may be a scheduled workout, a walk or even dancing to your favorite music.

- Choose healthy food and drinks. Foods that are high in nutrients, such as protein, vitamins and minerals are healthy choices. Avoid food or drink with added sugar, fat or salt.

- Avoid tobacco, alcohol and drugs. If you smoke tobacco or if you vape, you're already at higher risk of lung disease. Because COVID-19 affects the lungs, your risk increases even more. Using alcohol to manage how you feel can make matters worse and reduce your coping skills. Avoid taking illegal drugs or misusing prescriptions to manage your feelings.

Take care of your mind

Healthy coping actions for your brain start with deciding how much news and social media is right for you. Staying informed, especially during a pandemic, helps you make the best choices but do it carefully.

Set aside a specific amount of time to find information in the news or on social media, stay limited to that time, and choose reliable sources. For example, give yourself up to 20 or 30 minutes a day of news and social media. That amount keeps people informed but not overwhelmed.

For COVID-19, consider reliable health sources. Examples are the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Other healthy self-care tips are:

- Relax and recharge. Many people benefit from relaxation exercises such as mindfulness, deep breathing, meditation and yoga. Find an activity that helps you relax and try to do it every day at least for a short time. Fitting time in for hobbies or activities you enjoy can help manage feelings of stress too.

- Stick to your health routine. If you see a healthcare professional for mental health services, keep up with your appointments. And stay up to date with all your wellness tests and screenings.

- Stay in touch and connect with others. Family, friends and your community are part of a healthy mental outlook. Together, you form a healthy support network for concerns or challenges. Social interactions, over time, are linked to a healthier and longer life.

Avoid stigma and discrimination

Stigma can make people feel isolated and even abandoned. They may feel sad, hurt and angry when people in their community avoid them for fear of getting COVID-19. People who have experienced stigma related to COVID-19 include people of Asian descent, health care workers and people with COVID-19.

Treating people differently because of their medical condition, called medical discrimination, isn't new to the COVID-19 pandemic. Stigma has long been a problem for people with various conditions such as Hansen's disease (leprosy), HIV, diabetes and many mental illnesses.

People who experience stigma may be left out or shunned, treated differently, or denied job and school options. They also may be targets of verbal, emotional and physical abuse.

Communication can help end stigma or discrimination. You can address stigma when you:

- Get to know people as more than just an illness. Using respectful language can go a long way toward making people comfortable talking about a health issue.

- Get the facts about COVID-19 or other medical issues from reputable sources such as the CDC and WHO.

- Speak up if you hear or see myths about an illness or people with an illness.

COVID-19 and health

The virus that causes COVID-19 is still a concern for many people. By recognizing when to get help and taking time for your health, life challenges such as COVID-19 can be managed.

- Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. National Institutes of Health. https://covid19.nih.gov/covid-19-topics/mental-health. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Mental Health and COVID-19: Early evidence of the pandemic's impact: Scientific brief, 2 March 2022. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mental_health-2022.1. Accessed March 12, 2024.

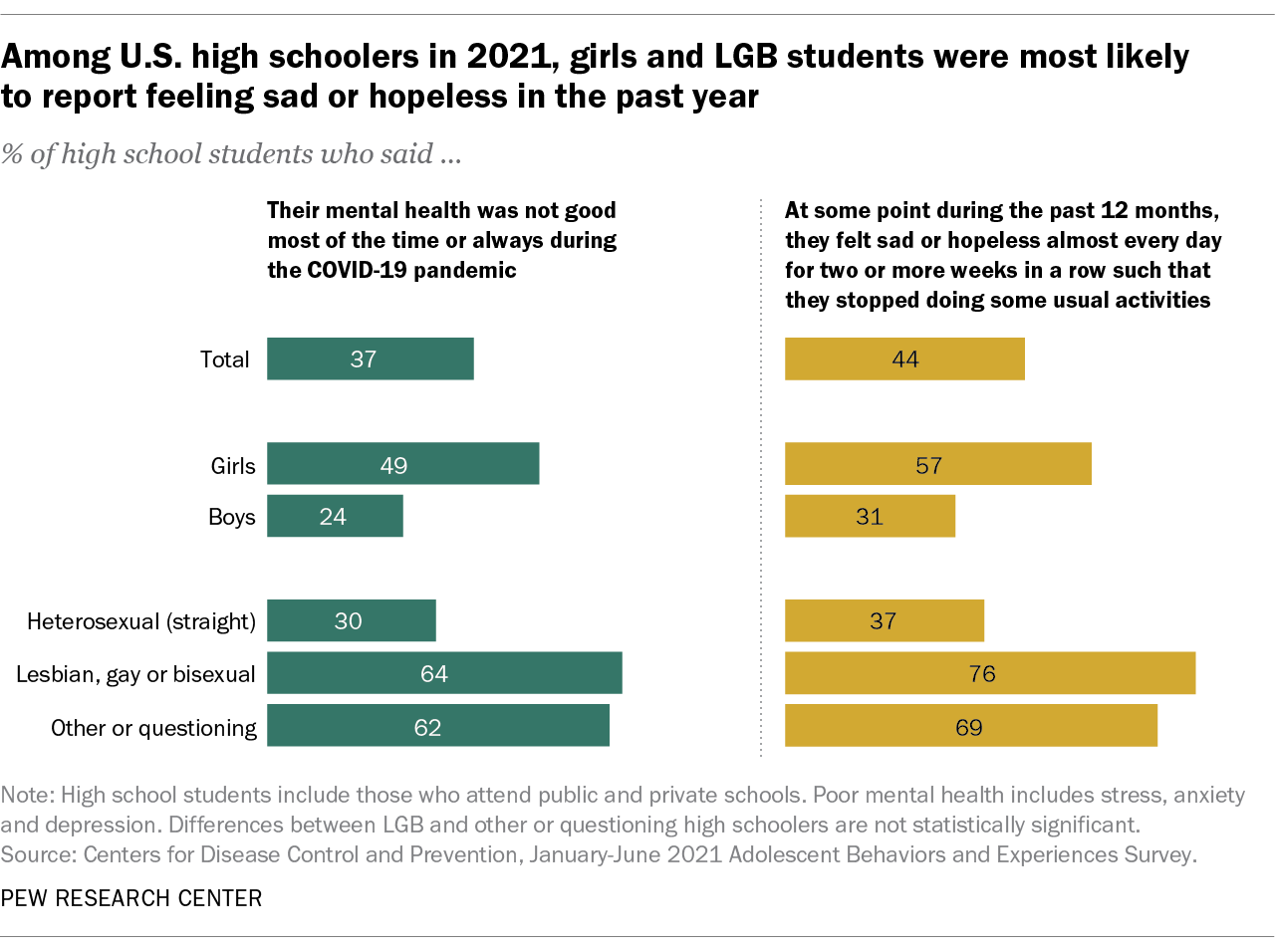

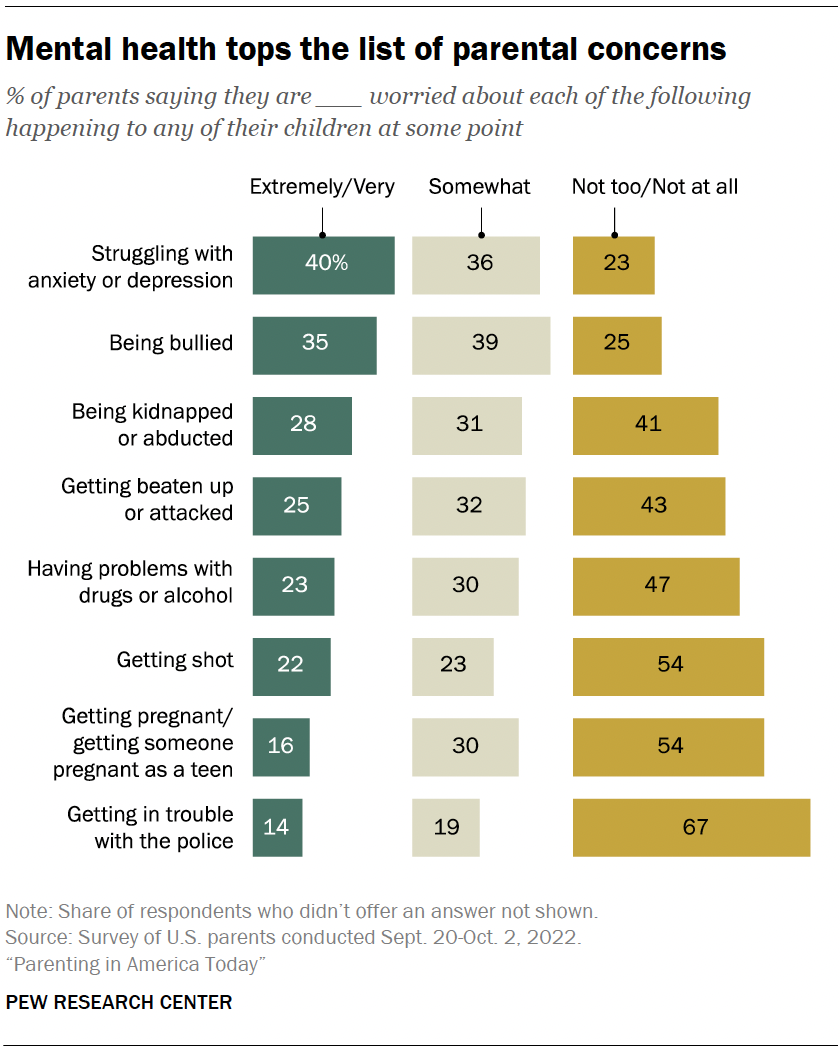

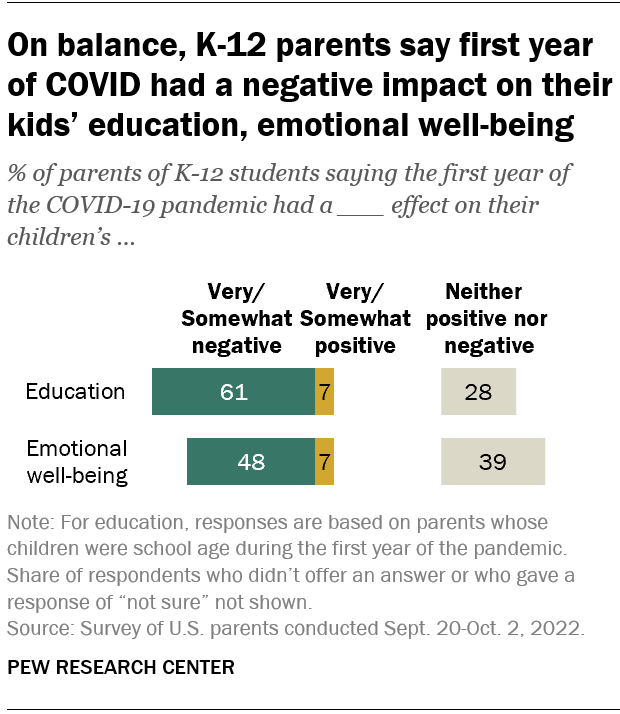

- Mental health and the pandemic: What U.S. surveys have found. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/03/02/mental-health-and-the-pandemic-what-u-s-surveys-have-found/. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Taking care of your emotional health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://emergency.cdc.gov/coping/selfcare.asp. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- #HealthyAtHome—Mental health. World Health Organization. www.who.int/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/healthyathome/healthyathome---mental-health. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Coping with stress. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/stress-coping/cope-with-stress/. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Manage stress. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/myhealthfinder/topics/health-conditions/heart-health/manage-stress. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- COVID-19 and substance abuse. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/covid-19-substance-use#health-outcomes. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- COVID-19 resource and information guide. National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/Support-Education/NAMI-HelpLine/COVID-19-Information-and-Resources/COVID-19-Resource-and-Information-Guide. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Negative coping and PTSD. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/gethelp/negative_coping.asp. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Health effects of cigarette smoking. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/index.htm#respiratory. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- People with certain medical conditions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Your healthiest self: Emotional wellness toolkit. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/health-information/emotional-wellness-toolkit. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- World leprosy day: Bust the myths, learn the facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/leprosy/world-leprosy-day/. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- HIV stigma and discrimination. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/hiv-stigma/. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Diabetes stigma: Learn about it, recognize it, reduce it. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/features/diabetes_stigma.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Phelan SM, et al. Patient and health care professional perspectives on stigma in integrated behavioral health: Barriers and recommendations. Annals of Family Medicine. 2023; doi:10.1370/afm.2924.

- Stigma reduction. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/od2a/case-studies/stigma-reduction.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Nyblade L, et al. Stigma in health facilities: Why it matters and how we can change it. BMC Medicine. 2019; doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1256-2.

- Combating bias and stigma related to COVID-19. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19-bias. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Yashadhana A, et al. Pandemic-related racial discrimination and its health impact among non-Indigenous racially minoritized peoples in high-income contexts: A systematic review. Health Promotion International. 2021; doi:10.1093/heapro/daab144.

- Sawchuk CN (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. March 25, 2024.

Products and Services

- A Book: Endemic - A Post-Pandemic Playbook

- Begin Exploring Women's Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- A Book: Future Care

- Antibiotics: Are you misusing them?

- COVID-19 and vitamin D

- Convalescent plasma therapy

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

- COVID-19: How can I protect myself?

- Herd immunity and respiratory illness

- COVID-19 and pets

- COVID-19 antibody testing

- COVID-19, cold, allergies and the flu

- Long-term effects of COVID-19

- COVID-19 tests

- COVID-19 drugs: Are there any that work?

- COVID-19 in babies and children

- Coronavirus infection by race

- COVID-19 travel advice

- COVID-19 vaccine: Should I reschedule my mammogram?

- COVID-19 vaccines for kids: What you need to know

- COVID-19 vaccines

- COVID-19 variant

- COVID-19 vs. flu: Similarities and differences

- COVID-19: Who's at higher risk of serious symptoms?

- Debunking coronavirus myths

- Different COVID-19 vaccines

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)

- Fever: First aid

- Fever treatment: Quick guide to treating a fever

- Fight coronavirus (COVID-19) transmission at home

- Honey: An effective cough remedy?

- How do COVID-19 antibody tests differ from diagnostic tests?

- How to measure your respiratory rate

- How to take your pulse

- How to take your temperature

- How well do face masks protect against COVID-19?

- Is hydroxychloroquine a treatment for COVID-19?

- Loss of smell

- Mayo Clinic Minute: You're washing your hands all wrong

- Mayo Clinic Minute: How dirty are common surfaces?

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Pregnancy and COVID-19

- Safe outdoor activities during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Safety tips for attending school during COVID-19

- Sex and COVID-19

- Shortness of breath

- Thermometers: Understand the options

- Treating COVID-19 at home

- Unusual symptoms of coronavirus

- Vaccine guidance from Mayo Clinic

- Watery eyes

Related information

- Mental health: What's normal, what's not - Related information Mental health: What's normal, what's not

- Mental illness - Related information Mental illness

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- Open access

- Published: 11 April 2023

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, anxiety, and depression

- Ida Kupcova 1 ,

- Lubos Danisovic 1 ,

- Martin Klein 2 &

- Stefan Harsanyi 1

BMC Psychology volume 11 , Article number: 108 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

21 Citations

46 Altmetric

Metrics details

The COVID-19 pandemic affected everyone around the globe. Depending on the country, there have been different restrictive epidemiologic measures and also different long-term repercussions. Morbidity and mortality of COVID-19 affected the mental state of every human being. However, social separation and isolation due to the restrictive measures considerably increased this impact. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), anxiety and depression prevalence increased by 25% globally. In this study, we aimed to examine the lasting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the general population.

A cross-sectional study using an anonymous online-based 45-question online survey was conducted at Comenius University in Bratislava. The questionnaire comprised five general questions and two assessment tools the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS). The results of the Self-Rating Scales were statistically examined in association with sex, age, and level of education.

A total of 205 anonymous subjects participated in this study, and no responses were excluded. In the study group, 78 (38.05%) participants were male, and 127 (61.69%) were female. A higher tendency to anxiety was exhibited by female participants (p = 0.012) and the age group under 30 years of age (p = 0.042). The level of education has been identified as a significant factor for changes in mental state, as participants with higher levels of education tended to be in a worse mental state (p = 0.006).

Conclusions

Summarizing two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, the mental state of people with higher levels of education tended to feel worse, while females and younger adults felt more anxiety.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The first mention of the novel coronavirus came in 2019, when this variant was discovered in the city of Wuhan, China, and became the first ever documented coronavirus pandemic [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. At this time there was only a sliver of fear rising all over the globe. However, in March 2020, after the declaration of a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), the situation changed dramatically [ 4 ]. Answering this, yet an unknown threat thrust many countries into a psycho-socio-economic whirlwind [ 5 , 6 ]. Various measures taken by governments to control the spread of the virus presented the worldwide population with a series of new challenges to which it had to adjust [ 7 , 8 ]. Lockdowns, closed schools, losing employment or businesses, and rising deaths not only in nursing homes came to be a new reality [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. Lack of scientific information on the novel coronavirus and its effects on the human body, its fast spread, the absence of effective causal treatment, and the restrictions which harmed people´s social life, financial situation and other areas of everyday life lead to long-term living conditions with increased stress levels and low predictability over which people had little control [ 12 ].

Risks of changes in the mental state of the population came mainly from external risk factors, including prolonged lockdowns, social isolation, inadequate or misinterpreted information, loss of income, and acute relationship with the rising death toll. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, anxiety and depression prevalence increased by 25% globally [ 13 ]. Unemployment specifically has been proven to be also a predictor of suicidal behavior [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. These risk factors then interact with individual psychological factors leading to psychopathologies such as threat appraisal, attentional bias to threat stimuli over neutral stimuli, avoidance, fear learning, impaired safety learning, impaired fear extinction due to habituation, intolerance of uncertainty, and psychological inflexibility. The threat responses are mediated by the limbic system and insula and mitigated by the pre-frontal cortex, which has also been reported in neuroimaging studies, with reduced insula thickness corresponding to more severe anxiety and amygdala volume correlated to anhedonia as a symptom of depression [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Speaking in psychological terms, the pandemic disturbed our core belief, that we are safe in our communities, cities, countries, or even the world. The lost sense of agency and confidence regarding our future diminished the sense of worth, identity, and meaningfulness of our lives and eroded security-enhancing relationships [ 24 ].

Slovakia introduced harsh public health measures in the first wave of the pandemic, but relaxed these measures during the summer, accompanied by a failure to develop effective find, test, trace, isolate and support systems. Due to this, the country experienced a steep growth in new COVID-19 cases in September 2020, which lead to the erosion of public´s trust in the government´s management of the situation [ 25 ]. As a means to control the second wave of the pandemic, the Slovak government decided to perform nationwide antigen testing over two weekends in November 2020, which was internationally perceived as a very controversial step, moreover, it failed to prevent further lockdowns [ 26 ]. In addition, there was a sharp rise in the unemployment rate since 2020, which continued until July 2020, when it gradually eased [ 27 ]. Pre-pandemic, every 9th citizen of Slovakia suffered from a mental health disorder, according to National Statistics Office in 2017, the majority being affective and anxiety disorders. A group of authors created a web questionnaire aimed at psychiatrists, psychologists, and their patients after the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Slovakia. The results showed that 86.6% of respondents perceived the pathological effect of the pandemic on their mental status, 54.1% of whom were already treated for affective or anxiety disorders [ 28 ].

In this study, we aimed to examine the lasting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the general population. This study aimed to assess the symptoms of anxiety and depression in the general public of Slovakia. After the end of epidemiologic restrictive measures (from March to May 2022), we introduced an anonymous online questionnaire using adapted versions of Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) [ 29 , 30 ]. We focused on the general public because only a portion of people who experience psychological distress seek professional help. We sought to establish, whether during the pandemic the population showed a tendency to adapt to the situation or whether the anxiety and depression symptoms tended to be present even after months of better epidemiologic situation, vaccine availability, and studies putting its effects under review [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ].

Materials and Methods

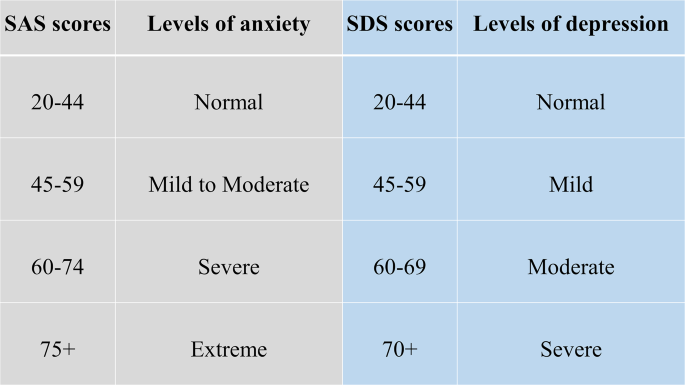

This study utilized a voluntary and anonymous online self-administered questionnaire, where the collected data cannot be linked to a specific respondent. This study did not process any personal data. The questionnaire consisted of 45 questions. The first three were open-ended questions about participants’ sex, age (date of birth was not recorded), and education. Followed by 2 questions aimed at mental health and changes in the will to live. Further 20 and 20 questions consisted of the Zung SAS and Zung SDS, respectively. Every question in SAS and SDS is scored from 1 to 4 points on a Likert-style scale. The scoring system is introduced in Fig. 1 . Questions were presented in the Slovak language, with emphasis on maintaining test integrity, so, if possible, literal translations were made from English to Slovak. The questionnaire was created and designed in Google Forms®. Data collection was carried out from March 2022 to May 2022. The study was aimed at the general population of Slovakia in times of difficult epidemiologic and social situations due to the high prevalence and incidence of COVID-19 cases during lockdowns and social distancing measures. Because of the character of this web-based study, the optimal distribution of respondents could not be achieved.

Categories of Zung SAS and SDS scores with clinical interpretation

During the course of this study, 205 respondents answered the anonymous questionnaire in full and were included in the study. All respondents were over 18 years of age. The data was later exported from Google Forms® as an Excel spreadsheet. Coding and analysis were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0, Armonk, NY, USA). Subject groups were created based on sex, age, and education level. First, sex due to differences in emotional expression. Second, age was a risk factor due to perceived stress and fear of the disease. Last, education due to different approaches to information. In these groups four factors were studied: (1) changes in mental state; (2) affected will to live, or frequent thoughts about death; (3) result of SAS; (4) result of SDS. For SAS, no subject in the study group scored anxiety levels of “severe” or “extreme”. Similarly for SDS, no subject depression levels reached “moderate” or “severe”. Pearson’s chi-squared test(χ2) was used to analyze the association between the subject groups and studied factors. The results were considered significant if the p-value was less than 0.05.

Ethical permission was obtained from the local ethics committee (Reference number: ULBGaKG-02/2022). This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were carried out following the institutional guidelines. Due to the anonymous design of the study and by the institutional requirements, written informed consent for participation was not required for this study.

In the study, out of 205 subjects in the study group, 127 (62%) were female and 78 (38%) were male. The average age in the study group was 35.78 years of age (range 19–71 years), with a median of 34 years. In the age group under 30 years of age were 34 (16.6%) subjects, while 162 (79%) were in the range from 31 to 49 and 9 (0.4%) were over 50 years old. 48 (23.4%) participants achieved an education level of lower or higher secondary and 157 (76.6%) finished university or higher. All answers of study participants were included in the study, nothing was excluded.

In Tables 1 and 2 , we can see the distribution of changes in mental state and will to live as stated in the questionnaire. In Table 1 we can see a disproportion in education level and mental state, where participants with higher education tended to feel worse much more than those with lower levels of education. Changes based on sex and age did not show any statistically significant results.

In Table 2 . we can see, that decreased will to live and frequent thoughts about death were only marginally present in the study group, which suggests that coping mechanisms play a huge role in adaptation to such events (e.g. the global pandemic). There is also a possibility that living in times of better epidemiologic situations makes people more likely to forget about the bad past.

Anxiety and depression levels as seen in Tables 3 and 4 were different, where female participants and the age group under 30 years of age tended to feel more anxiety than other groups. No significant changes in depression levels based on sex, age, and education were found.

Compared to the estimated global prevalence of depression in 2017 (3.44%), in 2021 it was approximately 7 times higher (25%) [ 14 ]. Our study did not prove an increase in depression, while anxiety levels and changes in the mental state did prove elevated. No significant changes in depression levels go in hand with the unaffected will to live and infrequent thoughts about death, which were important findings, that did not supplement our primary hypothesis that the fear of death caused by COVID-19 or accompanying infections would enhance personal distress and depression, leading to decreases in studied factors. These results are drawn from our limited sample size and uneven demographic distribution. Suicide ideations rose from 5% pre-pandemic to 10.81% during the pandemic [ 35 ]. In our study, 9.3% of participants experienced thoughts about death and since we did not specifically ask if they thought about suicide, our results only partially correlate with suicidal ideations. However, as these subjects exhibited only moderate levels of anxiety and mild levels of depression, the rise of suicide ideations seems unlikely. The rise in suicidal ideations seemed to be especially true for the general population with no pre-existing psychiatric conditions in the first months of the pandemic [ 36 ]. The policies implemented by countries to contain the pandemic also took a toll on the population´s mental health, as it was reported, that more stringent policies, mainly the social distancing and perceived government´s handling of the pandemic, were related to worse psychological outcomes [ 37 ]. The effects of lockdowns are far-fetched and the increases in mental health challenges, well-being, and quality of life will require a long time to be understood, as Onyeaka et al. conclude [ 10 ]. These effects are not unforeseen, as the global population suffered from life-altering changes in the structure and accessibility of education or healthcare, fluctuations in prices and food insecurity, as well as the inevitable depression of the global economy [ 38 ].

The loneliness associated with enforced social distancing leads to an increase in depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress in children in adolescents, with possible long-term sequelae [ 39 ]. The increase in adolescent self-injury was 27.6% during the pandemic [ 40 ]. Similar findings were described in the middle-aged and elderly population, in which both depression and anxiety prevalence rose at the beginning of the pandemic, during the pandemic, with depression persisting later in the pandemic, while the anxiety-related disorders tended to subside [ 41 ]. Medical professionals represented another specific at-risk group, with reported anxiety and depression rates of 24.94% and 24.83% respectively [ 42 ]. The dynamic of psychopathology related to the COVID-19 pandemic is not clear, with studies reporting a return to normal later in 2020, while others describe increased distress later in the pandemic [ 20 , 43 ].

Concerning the general population, authors from Spain reported that lockdowns and COVID-19 were associated with depression and anxiety [ 44 ]. In January 2022 Zhao et al., reported an elevation in hoarding behavior due to fear of COVID-19, while this process was moderated by education and income levels, however, less in the general population if compared to students [ 45 ]. Higher education levels and better access to information could improve persons’ fear of the unknown, however, this fact was not consistent with our expectations in this study, as participants with university education tended to feel worse than participants with lower education. A study on adolescents and their perceived stress in the Czech Republic concluded that girls are more affected by lockdowns. The strongest predictor was loneliness, while having someone to talk to, scored the lowest [ 46 ]. Garbóczy et al. reported elevated perceived stress levels and health anxiety in 1289 Hungarian and international students, also affected by disengagement from home and inadequate coping strategies [ 47 ]. Wathelet et al. conducted a study on French University students confined during the pandemic with alarming results of a high prevalence of mental health issues in the study group [ 48 ]. Our study indicated similar results, as participants in the age group under 30 years of age tended to feel more anxious than others.

In conclusion, we can say that this pandemic changed the lives of many. Many of us, our family members, friends, and colleagues, experienced life-altering events and complicated situations unseen for decades. Our decisions and actions fueled the progress in medicine, while they also continue to impact society on all levels. The long-term effects on adolescents are yet to be seen, while effects of pain, fear, and isolation on the general population are already presenting themselves.

The limitations of this study were numerous and as this was a web-based study, the optimal distribution of respondents could not be achieved, due to the snowball sampling strategy. The main limitation was the small sample size and uneven demographic distribution of respondents, which could impact the representativeness of the studied population and increase the margin of error. Similarly, the limited number of older participants could significantly impact the reported results, as age was an important risk factor and thus an important stressor. The questionnaire omitted the presence of COVID-19-unrelated life-changing events or stressors, and also did not account for any preexisting condition or risk factor that may have affected the outcome of the used assessment scales.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to compliance with institutional guidelines but they are available from the corresponding author (SH) on a reasonable request.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–33.

Liu Y-C, Kuo R-L, Shih S-R. COVID-19: the first documented coronavirus pandemic in history. Biomed J. 2020;43:328–33.

Advice for the public on COVID-19 – World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public . Accessed 13 Nov 2022.

Osterrieder A, Cuman G, Pan-Ngum W, Cheah PK, Cheah P-K, Peerawaranun P, et al. Economic and social impacts of COVID-19 and public health measures: results from an anonymous online survey in Thailand, Malaysia, the UK, Italy and Slovenia. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e046863.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mofijur M, Fattah IMR, Alam MA, Islam ABMS, Ong HC, Rahman SMA, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the social, economic, environmental and energy domains: Lessons learnt from a global pandemic. Sustainable Prod Consum. 2021;26:343–59.

Article Google Scholar

Vlachos J, Hertegård E, Svaleryd B. The effects of school closures on SARS-CoV-2 among parents and teachers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:e2020834118.

Ludvigsson JF, Engerström L, Nordenhäll C, Larsson E, Open Schools. Covid-19, and child and teacher morbidity in Sweden. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:669–71.

Miralles O, Sanchez-Rodriguez D, Marco E, Annweiler C, Baztan A, Betancor É, et al. Unmet needs, health policies, and actions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a report from six european countries. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12:193–204.

Onyeaka H, Anumudu CK, Al-Sharify ZT, Egele-Godswill E, Mbaegbu P. COVID-19 pandemic: a review of the global lockdown and its far-reaching effects. Sci Prog. 2021;104:368504211019854.

The Lancet null. India under COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet. 2020;395:1315.

Lo Coco G, Gentile A, Bosnar K, Milovanović I, Bianco A, Drid P, et al. A cross-country examination on the fear of COVID-19 and the sense of loneliness during the First Wave of COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2586.

COVID-19 pandemic. triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide. https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide . Accessed 14 Nov 2022.

Bueno-Notivol J, Gracia-García P, Olaya B, Lasheras I, López-Antón R, Santabárbara J. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2021;21:100196.

Hajek A, Sabat I, Neumann-Böhme S, Schreyögg J, Barros PP, Stargardt T, et al. Prevalence and determinants of probable depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in seven countries: longitudinal evidence from the european COvid Survey (ECOS). J Affect Disord. 2022;299:517–24.

Piumatti G, Levati S, Amati R, Crivelli L, Albanese E. Trajectories of depression, anxiety and stress among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic in Southern Switzerland: the Corona Immunitas Ticino cohort study. Public Health. 2022;206:63–9.

Korkmaz H, Güloğlu B. The role of uncertainty tolerance and meaning in life on depression and anxiety throughout Covid-19 pandemic. Pers Indiv Differ. 2021;179:110952.

McIntyre RS, Lee Y. Projected increases in suicide in Canada as a consequence of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113104.

Funkhouser CJ, Klemballa DM, Shankman SA. Using what we know about threat reactivity models to understand mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Behav Res Ther. 2022;153:104082.

Landi G, Pakenham KI, Crocetti E, Tossani E, Grandi S. The trajectories of anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic and the protective role of psychological flexibility: a four-wave longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2022;307:69–78.

Holt-Gosselin B, Tozzi L, Ramirez CA, Gotlib IH, Williams LM. Coping strategies, neural structure, and depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study in a naturalistic sample spanning clinical diagnoses and subclinical symptoms. Biol Psychiatry Global Open Sci. 2021;1:261–71.

McCracken LM, Badinlou F, Buhrman M, Brocki KC. The role of psychological flexibility in the context of COVID-19: Associations with depression, anxiety, and insomnia. J Context Behav Sci. 2021;19:28–35.

Talkovsky AM, Norton PJ. Negative affect and intolerance of uncertainty as potential mediators of change in comorbid depression in transdiagnostic CBT for anxiety. J Affect Disord. 2018;236:259–65.

Milman E, Lee SA, Neimeyer RA, Mathis AA, Jobe MC. Modeling pandemic depression and anxiety: the mediational role of core beliefs and meaning making. J Affect Disorders Rep. 2020;2:100023.

Sagan A, Bryndova L, Kowalska-Bobko I, Smatana M, Spranger A, Szerencses V, et al. A reversal of fortune: comparison of health system responses to COVID-19 in the Visegrad group during the early phases of the pandemic. Health Policy. 2022;126:446–55.

Holt E. COVID-19 testing in Slovakia. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:32.

Stalmachova K, Strenitzerova M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on employment in transport and telecommunications sectors. Transp Res Procedia. 2021;55:87–94.

Izakova L, Breznoscakova D, Jandova K, Valkucakova V, Bezakova G, Suvada J. What mental health experts in Slovakia are learning from COVID-19 pandemic? Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62(Suppl 3):459–66.

Rabinčák M, Tkáčová Ľ, VYUŽÍVANIE PSYCHOMETRICKÝCH KONŠTRUKTOV PRE, HODNOTENIE PORÚCH NÁLADY V OŠETROVATEĽSKEJ PRAXI. Zdravotnícke Listy. 2019;7:7.

Google Scholar

Sekot M, Gürlich R, Maruna P, Páv M, Uhlíková P. Hodnocení úzkosti a deprese u pacientů se zhoubnými nádory trávicího traktu. Čes a slov Psychiat. 2005;101:252–7.

Lipsitch M, Krammer F, Regev-Yochay G, Lustig Y, Balicer RD. SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections in vaccinated individuals: measurement, causes and impact. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22:57–65.

Accorsi EK, Britton A, Fleming-Dutra KE, Smith ZR, Shang N, Derado G, et al. Association between 3 doses of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and symptomatic infection caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and Delta Variants. JAMA. 2022;327:639–51.

Barda N, Dagan N, Cohen C, Hernán MA, Lipsitch M, Kohane IS, et al. Effectiveness of a third dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine for preventing severe outcomes in Israel: an observational study. Lancet. 2021;398:2093–100.

Magen O, Waxman JG, Makov-Assif M, Vered R, Dicker D, Hernán MA, et al. Fourth dose of BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide setting. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1603–14.

Dubé JP, Smith MM, Sherry SB, Hewitt PL, Stewart SH. Suicide behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis of 54 studies. Psychiatry Res. 2021;301:113998.

Kok AAL, Pan K-Y, Rius-Ottenheim N, Jörg F, Eikelenboom M, Horsfall M, et al. Mental health and perceived impact during the first Covid-19 pandemic year: a longitudinal study in dutch case-control cohorts of persons with and without depressive, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2022;305:85–93.

Aknin LB, Andretti B, Goldszmidt R, Helliwell JF, Petherick A, De Neve J-E, et al. Policy stringency and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis of data from 15 countries. The Lancet Public Health. 2022;7:e417–26.

Prochazka J, Scheel T, Pirozek P, Kratochvil T, Civilotti C, Bollo M, et al. Data on work-related consequences of COVID-19 pandemic for employees across Europe. Data Brief. 2020;32:106174.

Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59:1218–1239e3.

Zetterqvist M, Jonsson LS, Landberg Ã, Svedin CG. A potential increase in adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury during covid-19: a comparison of data from three different time points during 2011–2021. Psychiatry Res. 2021;305:114208.

Mooldijk SS, Dommershuijsen LJ, de Feijter M, Luik AI. Trajectories of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in a population-based sample of middle-aged and older adults. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;149:274–80.

Sahebi A, Nejati-Zarnaqi B, Moayedi S, Yousefi K, Torres M, Golitaleb M. The prevalence of anxiety and depression among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;107:110247.

Stephenson E, O’Neill B, Kalia S, Ji C, Crampton N, Butt DA, et al. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and depression in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2022;303:216–22.

Goldberg X, Castaño-Vinyals G, Espinosa A, Carreras A, Liutsko L, Sicuri E et al. Mental health and COVID-19 in a general population cohort in Spain (COVICAT study).Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;:1–12.

Zhao Y, Yu Y, Zhao R, Cai Y, Gao S, Liu Y, et al. Association between fear of COVID-19 and hoarding behavior during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating role of mental health status. Front Psychol. 2022;13:996486.

Furstova J, Kascakova N, Sigmundova D, Zidkova R, Tavel P, Badura P. Perceived stress of adolescents during the COVID-19 lockdown: bayesian multilevel modeling of the Czech HBSC lockdown survey. Front Psychol. 2022;13:964313.

Garbóczy S, Szemán-Nagy A, Ahmad MS, Harsányi S, Ocsenás D, Rekenyi V, et al. Health anxiety, perceived stress, and coping styles in the shadow of the COVID-19. BMC Psychol. 2021;9:53.

Wathelet M, Duhem S, Vaiva G, Baubet T, Habran E, Veerapa E, et al. Factors Associated with Mental Health Disorders among University students in France Confined during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2025591.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to provide our appreciation and thanks to all the respondents in this study.

This research project received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Medical Biology, Genetics and Clinical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University in Bratislava, Sasinkova 4, Bratislava, 811 08, Slovakia

Ida Kupcova, Lubos Danisovic & Stefan Harsanyi

Institute of Histology and Embryology, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University in Bratislava, Sasinkova 4, Bratislava, 811 08, Slovakia

Martin Klein

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

IK and SH have produced the study design. All authors contributed to the manuscript writing, revising, and editing. LD and MK have done data management and extraction, SH did the data analysis. Drafting and interpretation of the manuscript were made by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stefan Harsanyi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical permission was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Medical Biology, Genetics and Clinical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University in Bratislava (Reference number: ULBGaKG-02/2022). The need for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Medical Biology, Genetics and Clinical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University in Bratislava due to the anonymous design of the study. This study did not process any personal data and the dataset does not contain any direct or indirect identifiers of participants. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were carried out following the institutional guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kupcova, I., Danisovic, L., Klein, M. et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, anxiety, and depression. BMC Psychol 11 , 108 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01130-5

Download citation

Received : 14 November 2022

Accepted : 20 March 2023

Published : 11 April 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01130-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Mental Health

On This Page: -->

Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Frequently asked questions, mental health resources.

NIH has compiled a library of resources related to COVID-19 and mental illnesses and disorders, including condition-specific and population-specific resources.

An Urgent Issue

Both SARS-CoV-2 and the COVID-19 pandemic have significantly affected the mental health of adults and children. In a 2021 study, nearly half of Americans surveyed reported recent symptoms of an anxiety or depressive disorder, and 10% of respondents felt their mental health needs were not being met. Rates of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorder have increased since the beginning of the pandemic. And people who have mental illnesses or disorders and then get COVID-19 are more likely to die than those who don’t have mental illnesses or disorders.

Mental health is a focus of NIH research during the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers at NIH and supported by NIH are creating and studying tools and strategies to understand, diagnose, and prevent mental illnesses or disorders and improve mental health care for those in need.

How COVID-19 Can Impact Mental Health

If you get COVID-19, you may experience a number of symptoms related to brain and mental health, including:

Cognitive and attention deficits (brain fog)

Anxiety and depression

Suicidal behavior

Data suggest that people are more likely to develop mental illnesses or disorders in the months following infection, including symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). People with Long COVID may experience many symptoms related to brain function and mental health.

How the Pandemic Affects Developing Brains

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children is not yet fully understood. NIH-supported research is investigating factors that may influence the cognitive, social, and emotional development of children during the pandemic, including:

Changes to routine

Virtual schooling

Mask wearing

Caregiver absence or loss

Financial instability

Not Everyone Is Affected Equally

While the COVID-19 pandemic can affect the mental health of anyone, some people are more likely to be affected than others. People who are more likely to experience symptoms of mental illnesses or disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic include:

People from racial and ethnic minority groups

Mothers and pregnant people

People with financial or housing insecurity

People with disabilities

People with preexisting mental illnesses or substance use problems

Health care workers

People who belong to more than one of these groups may be at an even greater risk for mental illness.

Telehealth’s Potential to Help

The pandemic has prevented many people from visiting health care professionals in person, and as a result, telehealth has been more widely adopted during this time. Telehealth visits for mental health and substance use disorders increased significantly from 2020 to 2021 and now make up nearly half of all total visits for behavioral health.

Widespread adoption of telehealth services may help people who otherwise would not be able to access mental health support, such as people in rural areas or places with few providers.

I have a preexisting mental illness. Is COVID-19 more dangerous to me?

COVID-19 can be worse for people with mental illnesses. Data suggest that people who reported symptoms of anxiety or depression had a greater chance of being hospitalized after a COVID-19 diagnosis than people without those symptoms.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that having mood disorders and schizophrenia spectrum disorders can increase a person’s chances of having severe COVID-19. People with mental illnesses who belong to minority groups are also more likely to get COVID-19. And people with schizophrenia are significantly more likely to get COVID-19 and more likely to die from it.

Despite these risks, effective treatments are available. If you have a preexisting mental illness and get COVID-19, talk to your health care professional to determine the treatment plan that’s appropriate for you.

I’m experiencing symptoms of a mental illness or disorder. What should I do?

If you are experiencing symptoms of anxiety, depression, or any other mental illness or disorder, there are ways you can get help. For immediate help:

Call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 (para ayuda en español, llame al 988)

Call or text the Disaster Distress Helpline , 1-800-985-5990 (press 2 for Spanish)

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration can help you find mental health or substance use specialists.

Talk to your health care professional or mental health care professional. Together, you can work on a plan to manage or reduce your symptoms.

What research is NIH doing on the mental health impacts of COVID-19?

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and other NIH Institutes have created research initiatives to address mental health for people in general and for the most vulnerable people specifically. Examples of this research include:

NIH's Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER) Initiative has launched RECOVER-NEURO , a clinical trial that will test interventions to combat cognitive problems caused by Long COVID, including brain fog, memory problems, difficulty with attention, thinking clearly, and problem solving.

NIMH launched a five-year research study called RECOUP-NY to promote the mental health of New Yorkers from communities hard-hit by COVID-19. The study will test the use of a new care model called Problem Management Plus (PM+) that can be used by non-specialists.

A study funded by NIMH is examining the use of mobile apps to address mental health disparities .

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) is funding research to understand the effects of mask usage for children , including any impacts on their emotional and brain development.

NIMH is funding research on the impacts of the pandemic on underserved and vulnerable populations and on the cognitive, social, and emotional development of children .

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) is funding research on how COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 affect the causes and consequences of alcohol misuse .

A collaborative study supported by NIMH and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) enrolled more than 3,600 people from all 50 U.S. states to understand the stressors affecting people during the pandemic.

Mental Health Resources by Topic

A library of resources related to COVID-19 and mental illnesses and disorders

Page last updated: September 28, 2023

- High Contrast

- Increase Font

- Decrease Font

- Default Font

- Turn Off Animations

Last updated 27/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine

- > Volume 37 Issue 4: Themed Issue: COVID-19 and Ment...

- > Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: looking back...

Article contents

Introduction, mental health effects of covid-19, research priorities, financial support, conflict of interest, ethical standards, mental health and the covid-19 pandemic: looking back and moving forward.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 December 2020

COVID-19 continues to exert unprecedented challenges for society and it is now well recognised that mental health is a key healthcare issue related to the pandemic. The current edition of the Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine focusses on the impact of COVID-19 on mental illness by combining historical review papers, current perspectives and original research. It is important that psychiatrists leading mental health services in Ireland continue to advocate for mental health supports for healthcare workers and their patients, while aiming to deliver services flexibly. As the pandemic evolves, it remains to be seen whether the necessary funding to deliver effective mental healthcare will be allocated to psychiatric services. Ongoing service evaluation and research is needed as the myriad impacts of the pandemic continue to evolve. In a time of severe budgetary constraints, ensuring optimum use of scare resources becomes an imperative.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to present the greatest global health challenge in modern history. While emerging data is improving our understanding of the virus and its impact on health, societal cohesion and world economies, the situation globally continues to evolve. As such, findings and learnings that emerge at one point of the pandemic can appear to have relatively limited utility at another point. Arguably, never in living memory has there been a global phenomenon impacting population mental health in such a dynamic fashion. The challenge for mental health science is to capture and report these dynamic trends in a timely manner to inform and support psychiatrists implementing evidence-based care in this uniquely challenging environment. A parallel requirement is that such services are adequately resourced to meet the needs of both service user and provider.

This COVID-19-themed issue of the Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine aims to provide a more nuanced understanding of the multifaceted mental health impact of the pandemic to date. In so doing, we sincerely hope that this issue will provide colleagues with a timely and useful resource in these uncertain times.

A number of commentators in the popular media have noted that one potential silver-lining of this pandemic has been a mainstreaming of mental health within the broader considerations of the health impact of the pandemic. It is has been noted that mental health needs have never been as central to public discourse as during recent media discussions about the impact of the various restrictions implemented due to the pandemic. The assumption that this increased consideration of mental health will indeed represent a true and meaningful shift in public policy towards psychiatric services and, by extension, increased funding, is yet to be borne out. Indeed, there remains a very real risk that this discourse will merely serve to enhance the already considerable societal focus on psychological well-being and continue to marginalise the moderate to severe end of the mental illness spectrum. It is particularly noteworthy that certain high-risk groups with pre-existing mental illness might remain most vulnerable to the potentially deleterious psychological impact of the pandemic, notwithstanding that many patients within these groups may display significant resilience. An ambiguous focus on mental health , which fails to take account of the urgent needs of overextended and under-resourced psychiatric services, represents a clear and pressing concern. Within this exceptional set of circumstances, the compelling need for effective advocacy emanating from psychiatrists to constructively inform and shape public discourse has been brought sharply into focus.

As predicted at the outset of the first wave of the pandemic, psychiatric morbidity is peaking later than the physical health consequences of the pandemic (Gunnell et al. Reference Gunnell, Appleby, Arensman, Hawton, John and Kapur 2020 ), and current trends suggest that this peak will indeed endure for longer than the impact on physical health. Emerging data from services nationwide indicates increasing referrals to psychiatric services following the initial pandemic lockdown, and ongoing evaluation of referrals to psychiatric services is now needed.

A further strategy which can help to determine the effects of the current pandemic is a reflection on historical events and the retrospective lessons that may be learned from them. Two historical papers in this issue focus on previous pandemics and other global events to evaluate how mental illness was impacted at the time. The multifaceted impact of COVID-19 on population mental health may not be realised for some time and it is important to start planning now for ongoing consequences such as the potential severe economic consequences in the months and years ahead.

Another somewhat double-edged silver-lining of the pandemic is the increased acknowledgement of the psychological burden associated with frontline healthcare service provision (Behrman et al. Reference Behrman, Baruch and Stegen 2020 ; Faderani et al. Reference Faderani, Monks, Peprah, Colori, Allen, Amphlett and Edwards 2020 ). Pre-pandemic data indicated a high-level of stress and burnout among doctors in Ireland (McNicholas et al. Reference McNicholas, Sharma, Oconnor and Barrett 2020 ; Humphries et al. Reference Humphries, McDermott, Creese, Matthews, Conway and Byrne 2020 ). Calls have been consistently made since the outset of the pandemic to enshrine the well-being of healthcare staff as a central tenet of the overall model of healthcare service response (Unadkat and Farquhar, Reference Unadkat and Farquhar 2020 ). This pro-active approach was advocated not only because protecting staff was recognised as the right thing to do but also to buffer against the predictable psychological consequences of providing healthcare within extremely challenging and rapidly-changing circumstances (Maunder et al. Reference Maunder, Leszcz, Savage, Adam, Peladeau and Romano 2008 ).

This Special Issue highlights some of the array of tools which have been proposed as helpful to clinicians to off-set stress and enhance resilience. To this end, there are considerations of mindfulness and story-telling which are proffered as possible means to pause and reflect and indeed the somewhat unique (for this journal) inclusion of poetry and prose represents an attempt to support and highlight the importance of enacting such strategies. Undoubtedly, however, research into what are described as psychological preparedness tools for healthcare workers is at a nascent stage and considerable further research is required prior to widespread implementation.

It is unsurprising, therefore, that while comprehensive Pandemic Preparedness Tools (Adelaja et al. Reference Adelaja, Sayma, Walton, McLachlan, de Boisanger and Bartlett-Pestell 2020 ) all incorporate specific elements designed to support the psychological well-being of healthcare staff, it appears reasonable to assert that additional support structures or tools have not been the experience of clinicians working throughout the pandemic. Indeed, a recent survey by the British Medical Association reported that 40% of the 6650 respondents indicated a worsening in their mental health status compared to pre-pandemic (Rimmer, Reference Rimmer 2020 ), with 10% describing their mental health as much worse . This is broadly in keeping with data from previous pandemics which suggest that, of those who experience negative psychological sequelae, the majority of healthcare staff will experience transient psychological distress rather than diagnosable moderate–severe conditions (Greenberg et al. Reference Greenberg, Docherty, Gnanapragasam and Wessely 2020 ; Maunder et al. Reference Maunder, Hunter, Vincent, Bennett, Peladeau and Leszcz 2003 , Reference Maunder, Lancee, Balderson, Bennett, Borgundvaag and Evans 2006 , Reference Maunder, Leszcz, Savage, Adam, Peladeau and Romano 2008 ).

These figures remain concerning however, and while Irish data does not exist, if the medical population in Ireland experiences similar trends to our international colleagues, the overall prevalence rates and service need for doctors as psychiatric patients will rise significantly. As psychiatrists, we have a particular duty to highlight these risks; effective advocacy within this context is paramount. Moreover, this underscores a recognised pressing but under-considered need to develop doctor specific psychiatry services within the psychiatric service framework in Ireland. This model, already piloted in England and extended in the context of the pandemic, has seen an exponential rise in referrals over the latter stages of the pandemic (Conference Proceedings for Occupational Health and Burnout among Healthcare Workers: https://www.ucd.ie/medicine/capsych/summerschool2020/ ).

As outlined above, the constantly evolving nature of the pandemic presents an unprecedented challenge to researchers aiming to identify strategies for addressing the mental health issues arising in the current pandemic. Risk factors for mental illness may coalesce in different ways at different time points of the pandemic waves. By extension, the particulars of service need and delivery will also shift against this backdrop and it is important that psychiatric services remain flexible in service delivery at this time. Despite these challenges, it is crucial to prioritise an integrated approach to psychiatric translational research in Ireland which can inform service innovation and development. The efforts of colleagues to continue to innovate and examine outcomes despite the aforementioned complexities and myriad pressures is indeed laudable and worthwhile as our efforts to transform and remodel services can have real impact for our service users.

As with the first edition dedicated to COVID-19, we sincerely hope that this themed issue provides a useful resource to colleagues as we continue to grapple with unprecedented demands. There is currently no road map to inform how the situation will evolve and what will be the ultimate extent of service need. Once again, we are most grateful to all contributors who, despite unparalleled service pressures, have taken the time to reflect and share perspectives on their experiences, innovations and clinical practice. This issue highlights the extraordinary demands on psychiatric services and the likely enduring nature of this need in the years to come as longer-term impacts of the pandemic, particularly potential economic contraction, exert their toll on population mental illness. Effective advocacy for our patients, ourselves and our colleagues remains paramount.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors have no conflict of interest to disclore.

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 37, Issue 4

- B. Gavin (a1) , J. Lyne (a2) (a3) and F. McNicholas (a4) (a5)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2020.128

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 09 July 2021

Public mental health problems during COVID-19 pandemic: a large-scale meta-analysis of the evidence

- Xuerong Liu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9236-5773 1 ,

- Mengyin Zhu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5561-9570 1 ,

- Rong Zhang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4516-4116 2 ,

- Jingxuan Zhang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8979-5107 1 ,

- Chenyan Zhang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2945-6584 3 ,

- Peiwei Liu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2660-1106 4 ,

- Zhengzhi Feng ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6144-5044 1 &

- Zhiyi Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1744-4647 1 , 2

Translational Psychiatry volume 11 , Article number: 384 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

103 Citations

46 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Psychiatric disorders

- Scientific community

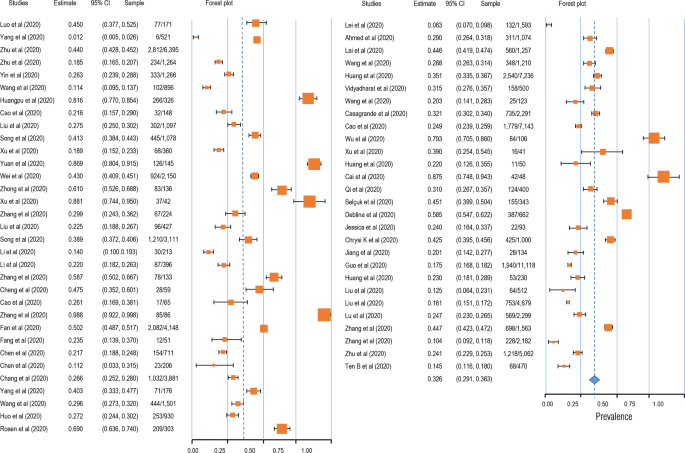

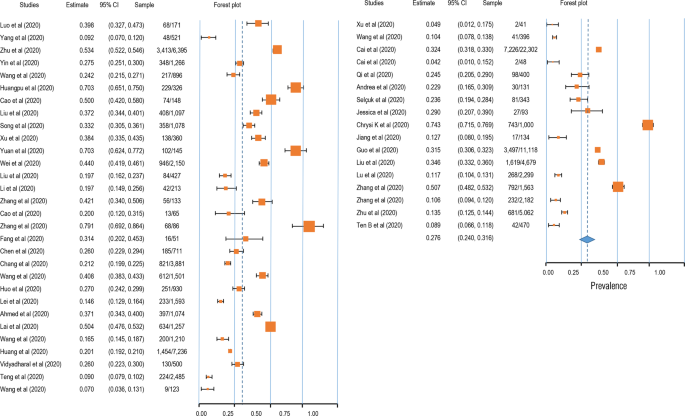

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has exposed humans to the highest physical and mental risks. Thus, it is becoming a priority to probe the mental health problems experienced during the pandemic in different populations. We performed a meta-analysis to clarify the prevalence of postpandemic mental health problems. Seventy-one published papers ( n = 146,139) from China, the United States, Japan, India, and Turkey were eligible to be included in the data pool. These papers reported results for Chinese, Japanese, Italian, American, Turkish, Indian, Spanish, Greek, and Singaporean populations. The results demonstrated a total prevalence of anxiety symptoms of 32.60% (95% confidence interval (CI): 29.10–36.30) during the COVID-19 pandemic. For depression, a prevalence of 27.60% (95% CI: 24.00–31.60) was found. Further, insomnia was found to have a prevalence of 30.30% (95% CI: 24.60–36.60). Of the total study population, 16.70% (95% CI: 8.90–29.20) experienced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Subgroup analysis revealed the highest prevalence of anxiety (63.90%) and depression (55.40%) in confirmed and suspected patients compared with other cohorts. Notably, the prevalence of each symptom in other countries was higher than that in China. Finally, the prevalence of each mental problem differed depending on the measurement tools used. In conclusion, this study revealed the prevalence of mental problems during the COVID-19 pandemic by using a fairly large-scale sample and further clarified that the heterogeneous results for these mental health problems may be due to the nonstandardized use of psychometric tools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder after infectious disease pandemics in the twenty-first century, including COVID-19: a meta-analysis and systematic review

Mental disorders following COVID-19 and other epidemics: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction.

Since the end of 2019, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak has continued to spread worldwide. Researchers rapidly identified the cause of COVID-19 to be the transmission of serious acute respiratory syndrome by a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) [ 1 ]. Unfortunately, due to the lack of effective cures and vaccines, the ability of public medical systems to guard against COVID-19 is deteriorating rapidly. Although approved vaccines are now available, their safety is still a concern [ 2 , 3 ]. Further, because of reports regarding the potential to be reinfected with COVID-19, public panic is still spreading even though COVID-19 transmission has been contained substantially [ 4 ]. To date, projections regarding the end of the COVID-19 pandemic around the world are still far from optimistic. There were more than 158.95 million confirmed cases and 3.30 million deaths by May 11, 2021 (supported by Johns Hopkins University), a situation that has led to unprecedented losses and stress.