Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

The goal of a research proposal is twofold: to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting research are governed by standards of the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, therefore, the guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to determine that the research problem has not been adequately addressed or has been answered ineffectively and, in so doing, become better at locating pertinent scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of conducting scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those findings. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your proposal is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to investigate.

- Why do you want to do the research? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of in-depth study. A successful research proposal must answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to conduct the research? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having difficulty formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here for strategies in developing a problem to study.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise . A research proposal must be focused and not be "all over the map" or diverge into unrelated tangents without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review . Proposals should be grounded in foundational research that lays a foundation for understanding the development and scope of the the topic and its relevance.

- Failure to delimit the contextual scope of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.]. As with any research paper, your proposed study must inform the reader how and in what ways the study will frame the problem.

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research . This is critical. In many workplace settings, the research proposal is a formal document intended to argue for why a study should be funded.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar . Although a research proposal does not represent a completed research study, there is still an expectation that it is well-written and follows the style and rules of good academic writing.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues . Your proposal should focus on only a few key research questions in order to support the argument that the research needs to be conducted. Minor issues, even if valid, can be mentioned but they should not dominate the overall narrative.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal. Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing most college-level academic papers, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. The text of proposals generally vary in length between ten and thirty-five pages, followed by the list of references. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like, "Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

Most proposals should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea based on a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and to be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in two to four paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that research problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Answer the "So What?" question by explaining why this is important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This is where you explain the scope and context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. It can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is most relevant in explaining the aims of your research.

To that end, while there are no prescribed rules for establishing the significance of your proposed study, you should attempt to address some or all of the following:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing; be sure to answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care?].

- Describe the major issues or problems examined by your research. This can be in the form of questions to be addressed. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain the methods you plan to use for conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Describe the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you plan to study, but what aspects of the research problem will be excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts, theories, or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while at the same time, demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methodological approaches they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, when stated, their recommendations. Also pay attention to any suggestions for further research.

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your proposed study in relation to the arguments put forth by other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically or chronologically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you review more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

NOTE: Do not shy away from challenging the conclusions made in prior research as a basis for supporting the need for your proposal. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. Highlighting the problematic conclusions strengthens your proposal. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

To help frame your proposal's review of prior research, consider the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: describe what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate among scholars?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, and methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.].

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that you have a plan worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and proposed methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

Describe the overall research design by building upon and drawing examples from your review of the literature. Consider not only methods that other researchers have used, but methods of data gathering that have not been used but perhaps could be. Be specific about the methodological approaches you plan to undertake to obtain information, the techniques you would use to analyze the data, and the tests of external validity to which you commit yourself [i.e., the trustworthiness by which you can generalize from your study to other people, places, events, and/or periods of time].

When describing the methods you will use, be sure to cover the following:

- Specify the research process you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results obtained in relation to the research problem. Don't just describe what you intend to achieve from applying the methods you choose, but state how you will spend your time while applying these methods [e.g., coding text from interviews to find statements about the need to change school curriculum; running a regression to determine if there is a relationship between campaign advertising on social media sites and election outcomes in Europe ].

- Keep in mind that the methodology is not just a list of tasks; it is a deliberate argument as to why techniques for gathering information add up to the best way to investigate the research problem. This is an important point because the mere listing of tasks to be performed does not demonstrate that, collectively, they effectively address the research problem. Be sure you clearly explain this.

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers and pitfalls in carrying out your research design and explain how you plan to address them. No method applied to research in the social and behavioral sciences is perfect, so you need to describe where you believe challenges may exist in obtaining data or accessing information. It's always better to acknowledge this than to have it brought up by your professor!

V. Preliminary Suppositions and Implications

Just because you don't have to actually conduct the study and analyze the results, doesn't mean you can skip talking about the analytical process and potential implications . The purpose of this section is to argue how and in what ways you believe your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the subject area under investigation. Depending on the aims and objectives of your study, describe how the anticipated results will impact future scholarly research, theory, practice, forms of interventions, or policy making. Note that such discussions may have either substantive [a potential new policy], theoretical [a potential new understanding], or methodological [a potential new way of analyzing] significance. When thinking about the potential implications of your study, ask the following questions:

- What might the results mean in regards to challenging the theoretical framework and underlying assumptions that support the study?

- What suggestions for subsequent research could arise from the potential outcomes of the study?

- What will the results mean to practitioners in the natural settings of their workplace, organization, or community?

- Will the results influence programs, methods, and/or forms of intervention?

- How might the results contribute to the solution of social, economic, or other types of problems?

- Will the results influence policy decisions?

- In what way do individuals or groups benefit should your study be pursued?

- What will be improved or changed as a result of the proposed research?

- How will the results of the study be implemented and what innovations or transformative insights could emerge from the process of implementation?

NOTE: This section should not delve into idle speculation, opinion, or be formulated on the basis of unclear evidence . The purpose is to reflect upon gaps or understudied areas of the current literature and describe how your proposed research contributes to a new understanding of the research problem should the study be implemented as designed.

ANOTHER NOTE : This section is also where you describe any potential limitations to your proposed study. While it is impossible to highlight all potential limitations because the study has yet to be conducted, you still must tell the reader where and in what form impediments may arise and how you plan to address them.

VI. Conclusion

The conclusion reiterates the importance or significance of your proposal and provides a brief summary of the entire study . This section should be only one or two paragraphs long, emphasizing why the research problem is worth investigating, why your research study is unique, and how it should advance existing knowledge.

Someone reading this section should come away with an understanding of:

- Why the study should be done;

- The specific purpose of the study and the research questions it attempts to answer;

- The decision for why the research design and methods used where chosen over other options;

- The potential implications emerging from your proposed study of the research problem; and

- A sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship about the research problem.

VII. Citations

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used . In a standard research proposal, this section can take two forms, so consult with your professor about which one is preferred.

- References -- a list of only the sources you actually used in creating your proposal.

- Bibliography -- a list of everything you used in creating your proposal, along with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem.

In either case, this section should testify to the fact that you did enough preparatory work to ensure the project will complement and not just duplicate the efforts of other researchers. It demonstrates to the reader that you have a thorough understanding of prior research on the topic.

Most proposal formats have you start a new page and use the heading "References" or "Bibliography" centered at the top of the page. Cited works should always use a standard format that follows the writing style advised by the discipline of your course [e.g., education=APA; history=Chicago] or that is preferred by your professor. This section normally does not count towards the total page length of your research proposal.

Develop a Research Proposal: Writing the Proposal. Office of Library Information Services. Baltimore County Public Schools; Heath, M. Teresa Pereira and Caroline Tynan. “Crafting a Research Proposal.” The Marketing Review 10 (Summer 2010): 147-168; Jones, Mark. “Writing a Research Proposal.” In MasterClass in Geography Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning . Graham Butt, editor. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), pp. 113-127; Juni, Muhamad Hanafiah. “Writing a Research Proposal.” International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 1 (September/October 2014): 229-240; Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005; Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Punch, Keith and Wayne McGowan. "Developing and Writing a Research Proposal." In From Postgraduate to Social Scientist: A Guide to Key Skills . Nigel Gilbert, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 59-81; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences , Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- << Previous: Writing a Reflective Paper

- Next: Generative AI and Writing >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6 Preparing Your Research Proposal

More often than not, there will be a few steps that you’ll have to take before you can start gathering and analyzing data in pursuit of an answer to your research question. Preparing a research proposal is a milestone in any research project and is often required by sponsoring institutions in order to transition from ‘the ‘planning’ phase to the ‘doing’ phase. So why, you might ask, are we talking about this step in phase III, ‘writing’? That’s a great question and it has to do, primarily, with the order of thought and the information that must be included in a research proposal. In this chapter, we’ll cover the basic requirements of most research proposals and address the requirements and responsibilities of a researcher.

Chapter 6: Learning Objectives

Before you prepare to implement your research methodology, it is likely that you’ll need to gain approval to continue. As we explore the development of the research proposal, you’ll be able to:

- Describe the individual elements of a research proposal

- Delineate between the rationale and implementation portions of a research proposal

- Discuss the ethical tenets which govern researchers

- Define the purpose of an institutional review board

- Compare categories of institutional review board applications

What is a research proposal?

A research proposal can be thought of as the general blueprint for a proposed research project. There are very few instances wherein research projects can be pursued without support of a sponsoring institution. That is, a healthcare system, hospital, or academic institution. To receive support from a sponsoring institution, a researcher must articulate a clear plan for their research process to include:

- An overview of the literature which supports the investigation

- A statement of the problem

- A statement of purpose

- A hypothesis or central question

- An overview of how participants will be identified, selected, contacted or data will be identified, analyzed, and protected

- An overview of the proposed methodology (i.e. approach to the study)

- An acknowledgment that participants, data, and results will be treated ethically throughout the study

- A timeline for the project

As Crawford, Burkholder, and Cox (2020) describe, these items can be split into separate portions of a research proposal, the rationale (i.e. Whye) and implementation (i.e. How).

As we discussed in previous chapters, developing a robust rationale for your research will help guide the entire research process. The introduction to your research proposal should include a general description of why the research should be conducted. Aside from your general interest, the introduction to the research should be firmly rooted in the available evidence which, first identifies a problem; second, identifies a purpose for the pursuit of inquiry into the problem; and finally, articulates a clear and focused research question which addresses the gap in current knowledge on the topic.

Implementation

Outlining your plan for implementation is essential to gain approval to conduct your research. Equally important to developing a well-articulated rationale, the identification of a clear methodology for how you will implement your approach is an important component of a research proposal.

A plan of implementation can be presented in several ways. However, an inclusive plan should include the following elements (Crawford, Burkholder, & Cox, 2020):

- How you will select participants or identify ‘what’ is included in your investigation

- How you will measure what you’re investigating

- What type of data you will collect and how

- How you will analyze the data

- Frame the terms that specify your investigation

- Qualities of the study that are inherent to the study, but may be overlooked as obvious unless addressed

- Delimitations narrow the scope of the study regarding what it does not include. Limitations are an acknowledgement of the weaknesses of the study design or methodology (Spoiler: there are limitations to EVERY study).

- Influence practice?

- Impact policy?

- Provide a foundation for future research?

We’ve spent a lot of time discussing how to identify a problem, a purpose, articulate a question, and identify a sample and the selection and implementation of an appropriate approach. Ethical considerations of the researcher is another essential topic for any researcher to cover. Here, we’ll provide a general overview of ethical considerations that are required of sponsoring institutions to ensure the ethical treatment of study participants and related data.

As a clinician, you’re likely familiar with the tenets of bedside bioethics that guide clinical practice:

- Autonomy : The right to self-direction and control

- Beneficence : The intention to do ‘good’, or what is in the best interest of the patient

- Non-Maleficence : The goal to ‘do no harm’ in practicing

- Justice : The pursuit of fairness and equity

These basic tenets of care do not change much when viewed through the lens of a researcher. However, it is important to note the foundation upon which research ethics were built. In 1974, the National Research Act was drafted in response to blatant abuse of research methods such as the Tuskegee study and resulted in the establishment of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research.The ethical principles which guide researchers are derived outlined by the Belmont Report (HHS.gov) and include:

- Autonomy : Respect for a person to make personal choices and provisions and protections to be provided for participants belonging to vulnerable populations

- Beneficence : The intention to do what is morally right; to minimize risk and maximize benefits

- Justice : To promote equity among the treatment of individuals and groups

Researchers must address the ways in which they intent to uphold these principles in their proposed research project. Methods by which they do this include:

- Voluntary Informed Consent : Informed consent is a process which ensures that a participant is educated in terms that they can understand about the risks inherent to their participation. This process underscores respect through the provision of consent for a voluntary act (HHS.gov, n.d.)

- Avoidance of Harm : Avoidance of harm is related to the ethical tenet of beneficence and is the primary responsibility of the researcher

- Assessment of Risk: The common rule mandates that researchers ensure that the risk to potential participants in a research study are minimized and that the research cannot impose risk that outweighs the potential benefit of the outcomes.

- Right to Withdrawal: Participants must be made aware of their rights to withdraw from the study at any time, for any reason, without consequences.

- Responsibility to Terminate: The principle investigator has the responsibility to terminate the research intervention should it be made clear that the intervention has either a detrimental effect on participants or an overwhelmingly positive effect such that it would be unethical to continue the study.

Universal research practices which promote these principles must be included in a research proposal in order to conduct research at most institutions and are outlined in the Common Rule which regulates the functions of institutional review boards (IRBs).

Institutional Review Board

An IRB is a formally designated group which has been established to protect the rights and welfare of human subjects recruited to participate in research; specifically research conducted at, or supported by, a specific institution. Here it is important to understand what is meant by the terms ‘research’ and ‘human subjects’. In regards to the requirement of IRB review, the term research means a systematic investigation, development, testing and evaluation designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge (University of Southern California, n.d.). Human subjects in relation to research refers to a living individual who’s information or biospecimens are used or analyzed to generate either identifiable private information or biospecimens for the purpose of generalizable information (University of Southern California, n.d.).

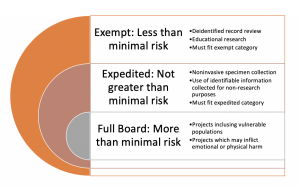

Although there are some details which will differ between organizations, there are general categories of human subject research which must be reviewed by an IRB. These classifications are designated by the degree of risk assumed by the participants and the ability of the researcher to mitigate those risks. Minimal risk is described by the federal regulations as the probability and magnitude of physical or psychological harm that is normally encountered in the daily lives, or in the routine medical, dental, or psychological examination of healthy persons (Electronic Code of Federal Regulations, n.d). Generally, research proposals will fall into one of the following categories:

- Exempt : Exempt research poses no more than minimal risk to adult, non-vulnerable populations.

- Expedited : Research that poses no more than minimal risk to participants and fits into one of the expedited categories described in federal regulations 45 CFR 46.110 (HHS.gov)

- Full Board : Research that does not qualify for either exempt or expedited review and poses more than minimal risk to participants. This type of review requires the approval from a full membership of an IRB.

Projects that don’t need IRB approval

Projects which are not considered human subjects research are not required to be reviewed by an IRB. Quality improvement projects do not typically require formal IRB review. However, individual institutional requirements should be reviewed and followed; preferably, in the planning phase of your research project to ensure that the requirements of your specific review align with both your approach and your timeline.

Key Takeaways

- Research proposals can be split into two primary components: The rational and the plan of implementation

- The introduction of your research proposal should encompass a description of your problem, purpose, and research question

- The identification of your research approach should be firmly guided by the ethical tenets of autonomy, beneficence, and justice

- The researcher has an ethical responsibility to protect participants from risk

- An institutional review board is a formal board charged with reviewing risks associated with research projects

- There are differing levels of institutional review; assumption of risk is the primary factor in classifying level of IRB review

Crawford, L.M., Burkholder, G.J., Cox, K.A. (2020). Writing the Research Proposal. In G.J. Burkholder, K.A Cox, L.M. Crawford, and J.H. Hitchcock (Eds.), Research design and methods: An applied guide for the scholar-practitioner (pp. 309-334). Sage Publications

Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. (2020, August, 17). Protection of human subjects . Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/retrieveECFR?gp=&SID=83cd09e1c0f5c6937cd9d7513160fc3f&pitd=20180719&n=pt45.1.46&r=PART&ty=HTML#se45.1.46_1104

Health and Human Services. (2020, August, 14). The Belmont report . Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/index.html

University of Southern California. (2020, August, 17). Office for the protection of research subjects . University of Southern California. https://oprs.usc.edu/irb-review/types-of-irb-review/

The right to self direction and control

The intention to do 'good'

The intention to do no harm

Pursuit of fairness and equity

A systematic investigation

Living persons participating in research

Probability of harm that does not exceed that encountered in every day life

IRB classification for research projects that do not pose more than minimal risk to adult, non-vulnerable populations

Classification of IRB approval for research that does not pose more than minimal risk, but fits into federally regulated categories.

IRB Classification for research that does pose more than minimal risk for participants

Practical Research: A Basic Guide to Planning, Doing, and Writing Copyright © by megankoster. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Ch. 7 - Proposal Review, Approval, and Submission

7.1 Required Institutional Signature 7.2 Internal Review of Research Proposals 7.3 Internal Review of Proposals for Projects other than Research 7.4 Sponsor Limitation of Proposals from Institution 7.5 Procedures for the Submission of Proposals 7.6 Pre-Award Audit/Request for Additional Information

return to Table of Contents

7.1 Required Institutional Signature

Because Caltech certifies compliance with sponsor requirements and accepts certain responsibilities at the time a proposal is submitted, sponsors typically require a real or electronic signature from the applicant institution in addition to one from the PI. The signature of an institutional or authorized official indicates the organization complies with sponsor and governmental regulations, has adequate facilities and infrastructure to complete the project, and offers to perform the described work within the requested budget and any listed cost sharing commitment.

The Caltech Way

All proposals to sponsors for grants, contracts and cooperative agreements must be reviewed and approved by the Division Chair and submitted by the Office of Sponsored Research.

The Office of Sponsored Research is the Institute contact point for sponsored activities when a formal agreement (e.g., a grant, contract, or cooperative agreement) with the Institute is contemplated that includes terms and conditions, i.e., the funds will not be classified as a gift.

Caltech Faculty Handbook Chapter 7

7.2 Internal Review of Research Proposals

A formal proposal review process ensures key issues are reviewed by all stakeholders within an institution. Areas of review include: facilities and space commitments, conflict of interest, involvement of human subjects and/or vertebrate animals, and cost sharing commitments.

All institutional reviews must be completed prior to the submission of a proposal to a sponsor. The Division Approval Form for Sponsored Projects must be completed to document internal reviews and approvals of proposals prior to submission.

All applications for new, noncompeting continuation, renewal or supplemental awards or revisions to proposals or program budgets requested by the sponsor must be accompanied by a completed and signed Division Approval Form (DAF) .

The Administrative Committee on Sponsored Research is appointed by the President and reports to the Vice Provost for Research. The Committee is responsible for reviewing certain types of research proposals before an award can be accepted by the Institute. These include:

- Proposals submitted to for-profit sponsors (excluding federal flow-through funds)

- Proposals submitted to foreign entities

- Proposals requesting annual funding in excess of $5 million or total funding that exceeds $10 million

- Proposals referred to the Committee by the Vice Provost for Research or the Office of Sponsored Research

Caltech Faculty Handbook Chapter 7 (pg. 7/28)

Caltech Institute Research & Compliance Committees website

7.3 Internal Review of Proposals for Projects other than Research

The Institute seeks funding from government and private agencies for activities that are research-related, but not in themselves research. Examples include: instrumentation programs, training programs, student support, building renovations.

Research-related proposals follow the same procedures as research proposals, i.e., completion of a Divisional Approval Form, submission to the Office of Sponsored Research through the Division Chair. (see Section 7.2)

Proposals for testing programs require DAF approval from the Division Chair and/or other official responsible for the involved laboratory or facility, and the Office of Sponsored Research.

Proposals for graduate student fellowships, individual graduate student financial support and institutional training grants require approval of the Dean of Graduate Studies on the DAF.

Proposals for educational programs, summer institutes, equipment and renovation of facilities require a completed DAF.

7.4 Sponsor Limitation of Proposals from Institution

Public and private sponsors may limit the number of proposals that can be submitted by each institution for certain funding programs. These programs are referred to as "limited submissions." Information regarding such a restriction is usually found in the sponsor's program guidelines or announcement of availability of funding. Attention is required by the institution and PI in order to avoid disqualification or delays that could result from submissions exceeding the limitation.

The Provost's Office coordinates the selection of proposals in "limited submission" cases. When a limited submission announcement is received, the Provost's Office forwards the announcement to the Division Chairs and outlines the internal review process.

The Provost, in consultation with the Division Chairs and/or the Vice Provosts, determines which of the interested PIs may apply. The list of approved PIs is forwarded to the Office of Sponsored Research (OSR) with instructions to submit only these proposals for the limited submission deadline.

Proposals received by OSR without having been subject to the internal review process will be forwarded to the Provost's office for guidance. Investigators who were unaware of the Provost's review requirement will also be referred to the Provost's office.

7.5 Procedures for the Submission of Proposals

Once a proposal has been reviewed internally by various stakeholders, it is submitted to the Office of Sponsored Research (OSR), the Caltech office responsible for submitting it to the sponsor. This office is also the "office of record," the office assigned responsibility for retaining copies of proposals (and any resulting awards) as official records of the institution.

All proposals to sponsors for grants, contracts and cooperative agreements must be submitted along with the signed Division Approval Form (DAF) to the Office of Sponsored Research at least three (3) business days prior to the agency due date.

If the proposal is being submitted to a foreign entity, or to a commercial sponsor (other than for Federal flow through funds), OSR requires an electronic copy of the full proposal for review by the Administrative Committee on Sponsored Research. This review generally takes place following the submission of the proposal.

Sponsored Research, Frequently Asked Questions

The Office of Sponsored Research is often reviewing many proposals simultaneously for the same deadline, in addition to processing awards and miscellaneous award transactions, and assisting divisional staff. In order to provide a clearer idea to faculty and divisional staff regarding what OSR can do, we have prepared the following guideline:

With at least 3 days' lead time prior to submission, OSR will perform a complete review, including:

- Comparison of proposal to sponsors' guidelines (e.g. forms and formatting)

- Review of budget (calculation, rates, relevance to project description, cost-sharing)

- Division Approval Form

- Compliance issues (e.g., human/animal subjects, health and safety, conflict of interest)

- PI Eligibility to Submit

With1 to 2days' lead time prior to submission, OSR will review at least the following:

- Review of budget for correct rates and cost sharing

- Divisional Approval Form

With less than 1 day's time prior to submission,OSR may only be able to verify that the PI and Division Chair have signed the Divisional Approval Form (the minimum requirement for any proposal to be submitted).

This is not intended to represent the most OSR can do, but the minimum OSR will do. If possible, OSR will provide a more thorough review than these minima, time permitting. The OSR team will let PIs know when a proposal will receive less than a complete review due to time constraints.

The following are some tips to facilitate the proposal approval process:

- E-mail or fax a copy of the Division Approval Form, cover page, budget, and budget explanation to OSR for pre-approval. The budget is usually the most time consuming portion of a proposal to check, and advance copies allow OSR to help correct possible errors while the text is still in its draft stage.

- E-mail or call the Office of Sponsored Research if the proposal is being submitted in response to a specific Broad Agency Announcement, Request for Proposals, Research Announcement, etc. so that OSR can review the proposal along with the solicitation guidelines.

- E-mail or fax information regarding the submission of the proposal. This enables OSR to begin preparing the cover letter for the proposal.

- The end of the month is usually the busiest time for proposal submission.

- Allow time for corrections and make sure a contact is available. In many cases, proposals sent to OSR are ready to be signed and submitted without further correction or revision. However, there are times when corrections need to be made, particularly if a budget has not been sent in advance or if a PI is applying to an agency with which he/she is unfamiliar. Allowing time for corrections helps to ensure the proposal is at its best when it is sent out. The PI and or a divisional contact should be available to make corrections until the proposal is ready to submit to the agency.

Deadlines vary widely among sponsors and sponsor programs. Proposal deadlines can be based upon a postmark by the U.S. Postal Service or receipt in the sponsor's mail room. With electronic systems, an accepted proposal may mean the electronic proposal file has been transferred and processed by one or two systems. In most cases, sponsors will not consider proposals that miss a deadline.

7.6 Pre-Award Audit/Request for Additional Information

Some sponsors perform pre-award audits or request additional information concerning the project as part of the proposal review process. For this reason, it is advisable for PI's to maintain a complete copy of each proposal, along with all supporting documents used in the development of the proposal budget.

During a proposal review, a sponsor may indicate a willingness to support a project at a reduced level of funding. If requested by the sponsor, a revised budget should be submitted through the Office of Sponsored Research. It is important for investigators to be aware that a discussion should occur related to how the scope of work will be reduced to accommodate the revised budget.

Documents related to unfunded proposals should be retained while pending a funding decision and for 18 months after a proposal has been denied.

Once funded, the proposal record becomes part of the award file and falls under the disposition schedule related to the award. Documents related to funded proposals should be retained for one year after the expiration or termination of the award.

Record Retention and Disposition Policy (8/2008)

Records Retention Schedule (9/2011)

Click to go to Chapter 8

Writing Your Research Proposal

5 Essentials You Need To Keep In Mind

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | June 2023

Writing a high-quality research proposal that “sells” your study and wins the favour (and approval) of your university is no small task. In this post, we’ll share five critical dos and don’ts to help you navigate the proposal writing process.

This post is based on an extract from our online course , Research Proposal Bootcamp . In the course, we walk you through the process of developing an A-grade proposal, step by step, with plain-language explanations and loads of examples. If it’s your first time writing a research proposal, you definitely want to check that out.

Overview: 5 Proposal Writing Essentials

- Understand your university’s requirements and restrictions

- Have a clearly articulated research problem

- Clearly communicate the feasibility of your research

- Pay very close attention to ethics policies

- Focus on writing critically and concisely

1. Understand the rules of the game

All too often, we see students going through all the effort of finding a unique and valuable topic and drafting a meaty proposal, only to realise that they’ve missed some critical information regarding their university’s requirements.

Every university is different, but they all have some sort of requirements or expectations regarding what students can and can’t research. For example:

- Restrictions regarding the topic area that can be research

- Restrictions regarding data sources – for example, primary or secondary

- Requirements regarding methodology – for example, qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods-based research

- And most notably, there can be varying expectations regarding topic originality – does your topic need to be super original or not?

The key takeaway here is that you need to thoroughly read through any briefing documents provided by your university. Also, take a look at past dissertations or theses from your program to get a feel for what the norms are . Long story short, make sure you understand the rules of the game before you start playing.

2. Have a clearly articulated research problem

As we’ve explained many times on this blog, all good research starts with a strong research problem – without a problem, you don’t have a clear justification for your research. Therefore, it’s essential that you have clarity regarding the research problem you’re going to address before you start drafting your proposal. From the research problem , the research gap emerges and from the research gap, your research aims , objectives and research questions emerge. These then guide your entire dissertation from start to end.

Needless to say, all of this starts with the literature – in other words, you have to spend time reading the existing literature to understand the current state of knowledge. You can’t skip this all-important step. All too often, we see students make the mistake of trying to write up a proposal without having a clear understanding of the current state of the literature, which is just a recipe for disaster. You’ve got to take the time to understand what’s already been done before you can propose doing something new.

3. Demonstrate the feasibility of your research

One of the key concerns that reviewers or assessors have when deciding to approve or reject a research proposal is the practicality/feasibility of the proposed research , given the student’s resources (which are usually pretty limited). You can have a brilliant research topic that’s super original and valuable, but if there is any question about whether the project is something that you can realistically pull off, you’re going to run into issues when it comes to getting your proposal accepted.

So, what does this mean for you?

First, you need to make sure that the research topic you’ve chosen and the methodology you’re planning to use is 100% safe in terms of feasibility . In other words, you need to be super certain that you can actually pull off this study. Of greatest importance here is the data collection and analysis aspect – in other words, will you be able to get access to the data you need, and will you be able to analyse it?

Second, assuming you’re 100% confident that you can pull the research off, you need to clearly communicate that in your research proposal. To do this, you need to proactively think about all the concerns the reviewer or supervisor might have and ensure that you clearly address these in your proposal. Remember, the proposal is a one-way communication – you get one shot (per submission) to make your case, and there’s generally no Q&A opportunity . So, make it clear what you’ll be doing, what the potential risks are and how you’ll manage those risks to ensure that your study goes according to plan.

If you have the word count available, it’s a good idea to present a project plan , ideally using something like a Gantt chart. You can also consider presenting a risk register , where you detail the potential risks, their likelihood and impact, and your mitigation and response actions – this will show the assessor that you’ve really thought through the practicalities of your proposed project. If you want to learn more about project plans and risk registers, we cover these in detail in our proposal writing course, Research Proposal Bootcamp , and we also provide templates that you can use.

Need a helping hand?

4. Pay close attention to ethics policies

This one’s a biggy – and it can often be a dream crusher for students with lofty research ideas. If there’s one thing that will sink your research proposal faster than anything else, it’s non-compliance with your university’s research ethics policy . This is simply a non-negotiable, so don’t waste your time thinking you can convince your institution otherwise. If your proposed research runs against any aspect of your institution’s ethics policies, it’s a no-go.

The ethics requirements for dissertations can vary depending on the field of study, institution, and country, so we can’t give you a list of things you need to do, but some common requirements that you should be aware of include things like:

- Informed consent – in other words, getting permission/consent from your study’s participants and allowing them to opt out at any point

- Privacy and confidentiality – in other words, ensuring that you manage the data securely and respect people’s privacy

- If your research involves animals (as opposed to people), you’ll need to explain how you’ll ensure ethical treatment, how you’ll reduce harm or distress, etc.

One more thing to keep in mind is that certain types of research may be acceptable from an ethics perspective, but will require additional levels of approval . For example, if you’re planning to study any sort of vulnerable population (e.g., children, the elderly, people with mental health conditions, etc.), this may be allowed in principle but requires additional ethical scrutiny. This often involves some sort of review board or committee, which slows things down quite a bit. Situations like this aren’t proposal killers, but they can create a much more rigid environment , so you need to consider whether that works for you, given your timeline.

5. Write critically and concisely

The final item on the list is more generic but just as important to the success of your research proposal – that is, writing critically and concisely .

All too often, students fall short in terms of critical writing and end up writing in a very descriptive manner instead. We’ve got a detailed blog post and video explaining the difference between these two types of writing, so we won’t go into detail here. However, the simplest way to distinguish between the two types of writing is that descriptive writing focuses on the what , while analytical writing draws out the “so what” – in other words, what’s the impact and relevance of each point that you’re making to the bigger issue at hand.

In the case of a research proposal, the core task at hand is to convince the reader that your planned research deserves a chance . To do this, you need to show the reviewer that your research will (amongst other things) be original , valuable and practical . So, when you’re writing, you need to keep this core objective front of mind and write with purpose, taking every opportunity to link what you’re writing about to that core purpose of the proposal.

The second aspect in relation to writing is to write concisely . All too often, students ramble on and use far more word count than is necessary. Part of the problem here is that their writing is just too descriptive (the previous point) and part of the issue is just a lack of editing .

The keyword here is editing – in other words, you don’t need to write the most concise version possible on your first try – if anything, we encourage you to just thought vomit as much as you can in the initial stages of writing. Once you’ve got everything down on paper, then you can get down to editing and trimming down your writing . You need to get comfortable with this process of iteration and revision with everything you write – don’t try to write the perfect first draft. First, get the thoughts out of your head and onto the paper , then edit. This is a habit that will serve you well beyond your proposal, into your actual dissertation or thesis.

Wrapping Up

To recap, the five essentials to keep in mind when writing up your research proposal include:

If you want to learn more about how to craft a top-notch research proposal, be sure to check out our online course for a comprehensive, step-by-step guide. Alternatively, if you’d like to get hands-on help developing your proposal, be sure to check out our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research journey, step by step.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

Thanks alot, I am really getting you right with focus on how to approach my research work soon, Insha Allah, God blessed you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

SOC W 505/506 Foundations of Social Welfare Research

- What is a Research Proposal?

- Qualitative Research

- Quantitative Research

- General Research Methods

- IRB's and Research Ethics

- Data Management and Analysis

Information on Writing a Research Proposal

From the Sage Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement and Evaluation:

Research proposals are written to propose a research project and oftentimes request funding, or sponsorship, for that research. The research proposal is used to assess the originality and quality of ideas and the feasibility of a proposed project. The goal of the research proposal is to convince others that the investigator has (a) an important idea; (b) the skills, knowledge, and resources to carry out the project; and (c) a plan to implement the project on time and within budget. This entry discusses the process of developing a research proposal and the elements of an effective proposal.

For a graduate student, a research proposal may be required to begin the dissertation process. This serves to communicate the research focus to others, such as members of the student’s dissertation committee. It also indicates the investigator’s plan of action, including a level of thoroughness and sufficient detail to replicate the study. The research proposal could also be considered as a contract, once members of the committee agree to the execution of the project.

Requirements may include: an abstract, introduction, literature review, method section, and conclusion. A research proposal has to clearly and concisely identify the proposed research and its importance. The background literature should support the need for the research and the potential impact of the findings.

The method section proposes a comprehensive explanation of the research design, including subjects, timeline, and data analysis. Research questions should be identified as well as measurement instruments and methods to answer the research questions. Proposals for research involving human subjects identify how the investigators will protect participants throughout their research project.

Proposals often require engaging in an external review either by an external evaluator or advisory board consisting of expert consultants in the field. References are included to provide documentation about the supporting literature identified in the proposal. Appendixes and supplemental materials may also be included, following the sponsoring organization’s guidelines. As a general rule, educational research proposals follow the American Psychological Association formatting guidelines and publishing standards. If funding is being requested, it is important for the proposal to identify how the research will benefit the sponsoring organization and its constituents.

The success of a research proposal depends on both the quality of the project and its presentation. A proposal may have specific goals, but if they are neither realistic nor desirable, the probability of obtaining funding is reduced. Similar to manuscripts being considered for journal articles, reviewers evaluate each research proposal to identify strengths and criticisms based on a general framework and scoring rubric determined by the sponsoring organization. Research proposals that meet the scoring criteria are considered for funding opportunities. If a proposal does not meet the scoring criteria, revisions may be necessary before resubmitting the proposal to the same or a different sponsoring organization.

Common mistakes and pitfalls can often be avoided in research proposal writing through awareness and careful planning. In an effective research proposal, the research idea is clearly stated as a problem and there is an explanation of how the proposed research addresses a demonstrable gap in the current literature. In addition, an effective proposal is well structured, frames the research question(s) within sufficient context supported by the literature, and has a timeline that is appropriate to address the focus and scope of the research project. All requirements of the sponsoring organization, including required project elements and document formatting, need to be met within the research proposal. Finally, an effective proposal is engaging and demonstrates the researcher’s passion and commitment to the research addressed.

- << Previous: Databases

- Next: Qualitative Research >>

- Last Updated: Aug 11, 2023 2:12 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uw.edu/hsl/sw505

Be boundless

1959 NE Pacific Street | T334 Health Sciences Building | Box 357155 | Seattle, WA 98195-7155 | 206-543-3390

© 2024 University of Washington | Seattle, WA

Writing a Research Proposal

- First Online: 10 April 2022

Cite this chapter

- Fahimeh Tabatabaei 3 &

- Lobat Tayebi 3

811 Accesses

A research proposal is a roadmap that brings the researcher closer to the objectives, takes the research topic from a purely subjective mind, and manifests an objective plan. It shows us what steps we need to take to reach the objective, what questions we should answer, and how much time we need. It is a framework based on which you can perform your research in a well-organized and timely manner. In other words, by writing a research proposal, you get a map that shows the direction to the destination (answering the research question). If the proposal is poorly prepared, after spending a lot of energy and money, you may realize that the result of the research has nothing to do with the initial objective, and the study may end up nowhere. Therefore, writing the proposal shows that the researcher is aware of the proper research and can justify the significance of his/her idea.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

A. Gholipour, E.Y. Lee, S.K. Warfield, The anatomy and art of writing a successful grant application: A practical step-by-step approach. Pediatr. Radiol. 44 (12), 1512–1517 (2014)

Article Google Scholar

L.S. Marshall, Research commentary: Grant writing: Part I first things first …. J. Radiol. Nurs. 31 (4), 154–155 (2012)

E.K. Proctor, B.J. Powell, A.A. Baumann, A.M. Hamilton, R.L. Santens, Writing implementation research grant proposals: Ten key ingredients. Implement. Sci. 7 (1), 96 (2012)

K.C. Chung, M.J. Shauver, Fundamental principles of writing a successful grant proposal. J. Hand Surg. Am. 33 (4), 566–572 (2008)

A.A. Monte, A.M. Libby, Introduction to the specific aims page of a grant proposal. Kline JA, editor. Acad. Emerg. Med. 25 (9), 1042–1047 (2018)

P. Kan, M.R. Levitt, W.J. Mack, R.M. Starke, K.N. Sheth, F.C. Albuquerque, et al., National Institutes of Health grant opportunities for the neurointerventionalist: Preparation and choosing the right mechanism. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 13 (3), 287–289 (2021)

A.M. Goldstein, S. Balaji, A.A. Ghaferi, A. Gosain, M. Maggard-Gibbons, B. Zuckerbraun, et al., An algorithmic approach to an impactful specific aims page. Surgery 169 (4), 816–820 (2021)

S. Engberg, D.Z. Bliss, Writing a grant proposal—Part 1. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 32 (3), 157–162 (2005)

D.Z. Bliss, K. Savik, Writing a grant proposal—Part 2. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 32 (4), 226–229 (2005)

D.Z. Bliss, Writing a grant proposal—Part 6. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 32 (6), 365–367 (2005)

J.C. Liu, M.A. Pynnonen, M. St John, E.L. Rosenthal, M.E. Couch, C.E. Schmalbach, Grant-writing pearls and pitfalls. Otolaryngol. Neck. Surg. 154 (2), 226–232 (2016)

R.J. Santen, E.J. Barrett, H.M. Siragy, L.S. Farhi, L. Fishbein, R.M. Carey, The jewel in the crown: Specific aims section of investigator-initiated grant proposals. J. Endocr. Soc. 1 (9), 1194–1202 (2017)

O.J. Arthurs, Think it through first: Questions to consider in writing a successful grant application. Pediatr. Radiol. 44 (12), 1507–1511 (2014)

M. Monavarian, Basics of scientific and technical writing. MRS Bull. 46 (3), 284–286 (2021)

Additional Resources

https://grants.nih.gov

https://grants.nih.gov/grants/oer.htm

https://www.ninr.nih.gov

https://www.niaid.nih.gov

http://www.grantcentral.com

http://www.saem.org/research

http://www.cfda.gov

http://www.ahrq.gov

http://www.nsf/gov

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Dentistry, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI, USA

Fahimeh Tabatabaei & Lobat Tayebi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Tabatabaei, F., Tayebi, L. (2022). Writing a Research Proposal. In: Research Methods in Dentistry. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98028-3_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98028-3_4

Published : 10 April 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-98027-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-98028-3

eBook Packages : Engineering Engineering (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- louisville.edu

- PeopleSoft HR

- PeopleSoft Campus Solutions

- PeopleSoft Financials

- Business Ops

- Cardinal Careers

- Undergraduate

- International

- Online Learning

Office of Research and Innovation

- Events and Trainings

- News Stories

- Grand Challenges

- Research Challenge Trust Fund

- Publications and Reports

- University of Louisville Scholar and Distinguished Scholar Program

- Monthly Town Hall Recordings

- Find Funding

- Proposal Development and Submission

- Compliance and Regulatory

- IRB Submissions

- Non-Funded Agreements

- Grants Management

- Hiring and Purchasing

- Innovation and Technology Transfer

- Industry Partnerships

- Clinical Trials

- Research Centers and Institutes

- Core Facilities

- Publishing and Presenting

- Training and Workshops

- Research Handbook

- Grand Challenges / Research Priorities

- Research Systems and Tools

- Sponsoring Research

- Licensing Technologies

- Launching a Startup

- Co-location and Land

- Working with our Students

- Research Capabilities

- Get started

- Pay and Benefits

- Post-Doc Association - UofL Chapter

- Post-Doc Appointing Approval Form

- Trainings and Workshops

- Children in Research

- Open Trials

- Offices and Staff

- Unit Research Offices

- Newsletter Signup

- CHAPTER FOUR: Proposal Review, Approval, and Submission

- / Researchers

- / Research Handbook

- / CHAPTER FOUR: Proposal Review, Approval, and Submission

4.1 Review and Approval Responsibilities

4.2 Institutional Cover Sheet iRIS eProposal / Proposal Clearance Form (PCF) / Transmit for Review and Initial Assessment (TRIA)-Multi-Institutional Research Application (MIRA)

4.3 Other Pre-Submission Approvals and Requirements

4.4 Proposal Review

4.5 Signature Authority

4.6 Unfunded Proposals

Proposals must be reviewed and have the appropriate approvals prior to submission to an external funding agency. The review process includes review by the department chair/unit head, the respective dean or designee and potential review and approval by University compliance offices/committees such as the Human Subjects Protection Program/Institutional Review Board (IRB) and Animal Use/Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Review and approval by the Office of Sponsored Programs Administration is the final step in the process prior to proposal submission.

All proposals submitted to external funding agencies must list the “University of Louisville Research Foundation, Inc.” as the award recipient unless the submission is required to be from the University. At least five (5) business days prior to submission to the Sponsor, the proposal must be submitted to OSPA for final review and approval.

Submission to OSPA is via the Integrated Research Information System (iRIS), by either the eProposal or the Proposal Short Form. The system’s eProposal is a comprehensive electronic packet which incorporates information required on the institutional cover sheet, proposal documents and sponsor forms. Alternately, the iRIS system offers a Proposal Short Form to which a conventional cover sheet and proposal documents can be uploaded. In this case, a completed and signed Proposal Clearance Form (PCF) or Transmit for Review and Initial Assessment (TRIA) – Multi-Institutional Research Application (MIRA) must accompany proposal submission to OSPA.

The institutional cover sheet - whether in the form of eProposal, Proposal Clearance Form (PCF) or Multi-Institutional Research Application TRIA-MIRA enables review of administrative, policy, and fiscal issues related to the proposal. The eProposal/PCF/TRIA-MIRA consists of a series of informational items and questions to assist the Principal Investigator/Project Director (PI/PD) and University reviewers in assessing potential risks and obligations should the proposal be funded. In addition to the signatures of the PI/PD and co-Investigators, signatures of the department chair/unit head and respective dean or designee are typically required.

The TRIA-MIRA or PCF Clinical Attachment is utilized for all clinical trials and sponsored research requiring approval of the Biomedical IRB and any other project/study that uses hospital facilities (for example, Jewish Hospital & St. Mary’s Healthcare Services, Norton Healthcare, or University of Louisville Hospital) or resources to conduct the research. The information on the PCF/TRIA-MIRA is shared with the respective hospital/study site and is used by the respective hospital/study site to grant approval for the research study to be conducted at their facility.

When University personnel from more than one academic department are participating in a proposed project, all appropriate department chairs/unit heads and deans must provide approval (by signing the PCF/MIRA) prior to submission of the proposal to OSPA for institutional approval.

If an award is received for which no proposal was submitted, an eProposal/PCF/TRIA-MIRA must be completed, signed, and submitted to OSPA prior to award establishment in PeopleSoft.

PIs/PDs are required to conduct research and manage the financial and regulatory aspects of sponsored projects in compliance with University policy, Federal and state law and Sponsor requirements. PIs/PDs must ensure that they and members of their research team(s) meet all compliance requirements, including any necessary disclosure(s) and training requirements.

Several areas of regulatory compliance may need to be considered when submitting proposals to an external funding agency. Examples include:

1) Conflict of Interest (COI);

2) Human Subjects Protection;

3) Animal Subjects Protection;

4) Biosafety and Radiation Safety;

5) Export and Secure Research Control.

See Chapter Nine of the Research Handbook for additional information on these and other research regulations.

If a proposed project requires UofL participants to interact with or handle human subjects, animals, or agents impacting environmental health and safety (e.g., recombinant DNA; pathogenic organisms; human blood, tissues, cell lines, or other potentially infectious materials [OPIM]), a proposal must be submitted to the appropriate committee(s) for internal review and approval prior to activation of an award. External Sponsors have different policies regarding the status of regulatory approvals at the time of proposal submission; while most will accept “pending review” or “pending approval,” some require full regulatory approval prior to submission. PIs/PDs should review the regulatory requirements of Sponsors when developing proposals for external funding.

Documentation of institutional approval (e.g., an approval letter) for actions “pending” at the time of proposal must be provided to OSPA prior to activation of an award (chartfield establishment). In limited situations OSPA may establish a chartfield prior to regulatory approval. As an example, for clinical trials, a chartfield may be established for site initiation visits and other limited startup activities prior to receiving final Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval [NOTE: no human subjects may be consented/enrolled into the trial until the IRB has granted formal approval].

All applications and proposals for external funding must be reviewed and approved by OSPA for consistency with Sponsor and Federal guidelines and University policies prior to submission. OSPA also reviews the budget for accuracy and proper format, ensure the correct application of fringe benefit and Facilities and Administrative Cost (aka F&A or indirect cost) rates, and verify University cost-sharing commitments.

Draft copies of all documents, including the draft budget may be submitted to OSPA for preliminary review and comment. This is particularly helpful for complex proposals, such as those with multi-year budgets, subagreements, and/or cost sharing commitments. It should be noted that preliminary review and comment does not constitute official approval for submission.

OSPA must receive the following items for review prior to granting approval for proposal submission:

1) eProposal, or completed and signed PCF and PCF Clinical Attachment (if applicable). Completed and signed TRIA-MIRA may be used for non-federal clinical proposals;

2) Proposal, including abstract, budget, budget justification, and Sponsor forms. A final copy of the proposal for OSPA files should be submitted at the time of proposal review (if electronic) or within two weeks following submission;

3) For proposals involving subrecipients, completed Subrecipient Commitment Form , budget, budget justification, and scope of work;

4) Indication of regulatory approval status (e.g., IRB, IACUC, DEHS);

5) Confirmation that all participants on the project, regardless of role, have completed the Attestation and Disclosure Form ; and

6) Approval in writing of all committed University cost sharing or matching obligations.

Only specific designees within OSPA have been granted signature authority by the President of the University. Under no circumstance is a PI/PD to sign a proposal to an external funding agency on behalf of the University and/or University of Louisville Research Foundation, Inc. without the prior approval of an Authorized Institutional Official.

Upon receipt of notification that a proposal will not be funded, the PI/PD should inform OSPA. OSPA retains copies of unfunded proposals for one year following notification that the proposal will not be funded.

1. General Information

2. Pre-Proposal Activities

3. Development, Budgeting

4. Proposal Review, Approval & Submission

5. Award Acceptance & Account Establishment

6. Financial Management of Awards

7. Admin/Non-Financial Management of Awards

8. Industry Awards & Agreements

9. Research Regulations

10. Service Centers

University of Louisville

Louisville, Ky. 40202

502.852.6512, 502.852.8361 (Fax)

Looking for a unit within the Office of Research and Innovation? Contact information here .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

How Do I Review Thee? Let Me Count the Ways: A Comparison of Research Grant Proposal Review Criteria Across US Federal Funding Agencies