Fighting for fair school construction funding in California

What can colleges learn from the pro-Palestinian protesters’ deal at a UC campus?

Why California schools call the police

How earning a college degree put four California men on a path from prison to new lives | Documentary

Patrick Acuña’s journey from prison to UC Irvine | Video

Family reunited after four years separated by Trump-era immigration policy

Calling the cops: Policing in California schools

Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in Higher Education: California and Beyond

Superintendents: Well paid and walking away

Keeping California public university options open

College in Prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

May 14, 2024

Getting California kids to read: What will it take?

April 24, 2024

Is dual admission a solution to California’s broken transfer system?

Teacher Voices

Now is the time for schools to invest in special-education inclusion models that benefit all students

Kimberly Berry

November 10, 2021.

Ivan was a fourth grader with big brown eyes, a wide smile and a quiet demeanor who refused to enter my classroom. “Everyone thinks I’m stupid,” he’d say. I’ve changed his name to protect his privacy.

At the time, my school employed a pull-out model for students with disabilities, meaning they were removed from their assigned classrooms to receive specialized services and supports. This left Ivan feeling embarrassed, ostracized and resistant to putting forth academic effort.

One in 8 students in U.S. public schools have an individualized education plan, or IEP, making them eligible for special education services. About 750,000 students with disabilities attend California public schools. Many, like Ivan, do not respond well to being substantially separated from their peers. Research suggests that inclusion models designed to integrate students with and without disabilities into a single learning environment can lead to stronger academic and social outcomes.

At Caliber ChangeMakers Academy — where I have been a program specialist for five of the 10 years I have worked with students with disabilities — we knew an inclusion model was best for Ivan and many others. Yet, we didn’t think we had the tools or resources to make it possible.

We were wrong.

Schools can support students like Ivan — and those of all abilities — to learn from and alongside one another in an inclusive setting without exorbitant costs if they rethink how they allocate resources and develop educators’ confidence and competence in teaching all students in a general education setting.

In 2019, we began intentionally organizing staff, time and money toward inclusion, and we did so without spending more than similar public schools do that don’t focus on inclusion.

Now, with the infusion of federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funding, schools have additional resources to invest in this approach now, in service to longer-term, sustainable change.

The nonprofit Education Resource Strategies studied our school and three others in California that are doing this work without larger investments of resources. Their analysis examines the resource shifts that inclusion-focused schools employ and can be tapped by other schools considering this work, taking a “do now, build toward” approach that addresses student needs and sustains these changes even after the emergency federal funding expires. Many of their recommendations mirror the steps we took to pursue an inclusion model.

It didn’t happen overnight, but three steps were important to our efforts to adopt a more inclusive model for teaching and learning:

- Shift special education staff into general education classrooms to support targeted group sizes. At Caliber ChangeMakers Academy, special education teachers are departmentalized, each serving as a co-teacher to two general education teachers, leveraging their content expertise to share responsibility for classroom instruction. That means some special education teachers now teach students who are not part of their caseload. That means they are tracking the goals of more students, which also means that young people have more specialty educators working together to support their individual needs.

- Prioritize connected professional learning around inclusion for all teachers . We adjusted teachers’ schedules to incorporate collaborative time for general education and special education teachers to meet before, during and after lessons to plan engaging, differentiated instruction for all. On the surface, the reduction in individual planning time might be a challenge. However, our teachers have found that they now feel more prepared, effective and connected because they have a partner to turn to for feedback, suggestions and encouragement.

- Invest in social-emotional and mental health staff to narrow the scope of special education teachers. These staff members work to reduce unnecessary special education referrals and mitigate troubles facing students regardless of their disability status. They also can help address unexpected challenges, meaning special education teachers can spend more time in general education classrooms. A tradeoff we made is to slightly increase class sizes with fewer general administrative and support staff to prioritize hiring experienced social-emotional learning and mental health professionals.

For schools eager to adopt a more inclusive instructional model, now is the time. The emergency federal funding creates unprecedented opportunities for school and system leaders to build research-backed, sustainable inclusion models that can better meet the needs of all students, including students with disabilities.

I’ve seen firsthand that inclusive, diverse classrooms can provide powerful learning opportunities for all students.

As for Ivan, he’s now in eighth grade and thriving in an inclusive, co-teaching classroom. He went from completing almost no academic work independently to completing science lab reports on his own, working in collaborative groups in his English class and declaring that he loves math. Because our school invested in and normalized differentiated supports in an inclusive setting, now Ivan and many other students are getting what they need to be successful academically, socially and emotionally.

Kimberly Berry is a special education program specialist at Caliber ChangeMakers Academy in Vallejo.

The opinions in this commentary are those of the author. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us .

Share Article

Comments (3)

Leave a comment, your email address will not be published. required fields are marked * *.

Click here to cancel reply.

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy .

Karina Villalona 3 years ago 3 years ago

I speak as a mom of two kids in co-teaching collaborative classes for their 4 main academic subjects, as well as a former teacher, and a school psychologist for 19 years. I agree with much of what Ms. Berry states. Co-teaching programs can be very successful for both general and special education students if all of the appropriate supports are in place (as listed by Ms. Berry). However, it is important to clarify that this … Read More

I speak as a mom of two kids in co-teaching collaborative classes for their 4 main academic subjects, as well as a former teacher, and a school psychologist for 19 years. I agree with much of what Ms. Berry states. Co-teaching programs can be very successful for both general and special education students if all of the appropriate supports are in place (as listed by Ms. Berry).

However, it is important to clarify that this model is not a panacea. Students with cognitive skills that are far below the average range have also shared how incredibly frustrating being in co-teaching classes can be for them. Even with support from the special education teacher, the pacing for some students is way too fast. In addition, depending on what the student’s specific classification is, co-teaching on its own does not allow an opportunity for remedial instruction.

My daughters are dyslexic. They participate in co-teaching with a lot of support from the special education teacher. They have one period of direct instruction in reading via an Orton-Gillingham based program and one period of Resource Room daily which allows them to work on content from the general education classes that they might need to review, break down or preview.

So, yes, co-teaching can be great for some students when the program is well managed and staffed; however, we cannot ignore the need for small group supports and remedial instruction when necessary.

Craig 3 years ago 3 years ago

Studies cited showing benefits of inclusion model typically suffer from selection bias, and there are no significant data on the effects of inclusion models on neurotypical peers. Does the author of this piece have data showing results that support her claims? Also, what do the teachers in this program have to say about it, in the first person? If this is truly working as presented it will be a game changer.

Monica Saraiya 3 years ago 3 years ago

The inclusion model is not a one size fits all one. Students with significant learning differences do not receive the services that best meet their needs in this model. As with all practices in education, inclusion must be one, but not the only way to service students who need specialized help with their learning.

EdSource Special Reports

San Bernardino County: Growing hot spot for school-run police

Why open a new district-run police department? “We need to take our safety to another level.”

Safety concerns on the rise in LAUSD; Carvalho looks to police

The Los Angeles Unified School District has reinstated police to two of its campuses — continuing an ebb and flow in its approach to law enforcement.

Going police-free is tough and ongoing, Oakland schools find

Oakland Unified remains committed to the idea that disbanding its own police force can work. Staff are trained to call the cops as a last resort.

When California schools summon police

EdSource investigation describes the vast police presence in K-12 schools across California.

EdSource in your inbox!

Stay ahead of the latest developments on education in California and nationally from early childhood to college and beyond. Sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email.

Stay informed with our daily newsletter

Because differences are our greatest strength

4 benefits of inclusive classrooms

By The Understood Team

Expert reviewed by Ginny Osewalt

At a glance

In an inclusive classroom, general education teachers and special education teachers work together to meet the needs of students.

This gives special education students the support they need while they stay in a general education classroom.

All students can benefit from inclusive classrooms.

When kids are found eligible for special education services , families often have concerns. A common one is that their child will be placed in a different classroom, apart from other kids. But the truth is that most kids who get services spend the majority of their time in general education classrooms. Many of those classrooms are what’s known as inclusive (or inclusion) classrooms.

In an inclusive classroom, general education teachers and special education teachers work together to meet the needs of all students.

This is key. As Carl A. Cohn, EdD, executive director of the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence, points out, “It’s important … to realize that special education students are first and foremost general education students.”

Many schools have inclusive classrooms. In part, that’s because of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). This law says that students who get special education services should learn in the least restrictive environment (LRE). That means they should spend as much time as possible with students who don’t get special education services.

Inclusive classes are set up in a number of ways. Some use a collaborative team teaching (or co-teaching) model. With co-teaching, there’s a special education teacher in the room all day.

Other inclusive classes have special education teachers push in at specific times during the day to teach (instead of pulling kids out of class to a separate room). In either case, both teachers are available to help all students.

Studies show that inclusion is beneficial for all students — not just for those who get special education services. In fact, research shows that inclusive education has positive short-term and long-term effects for all students.

Kids with special education needs who are in inclusive classes are absent less often. They develop stronger skills in reading and math. They’re also more likely to have jobs and pursue education after high school.

The same research shows that their peers benefit, too. They’re more comfortable with and more tolerant of differences. They also have increased positive self-esteem and diverse, caring friendships.

Read on to learn more benefits of inclusive classrooms.

1. Tailors teaching for all learners

All students learn differently. This is a principle of inclusive education. In an inclusive classroom, teachers weave in specially designed instruction and support that can help students make progress. These strategies are helpful for all students. Kids may be given opportunities to move around or use fidgets. And teachers often put positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS) in place.

Another key teaching strategy is to break students into small groups. When teachers use small groups, they can tailor their teaching to the way each student learns best. This is known as differentiated instruction .

Teachers meet the needs of all students by presenting lessons in different ways and using the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework. For example, they may use multisensory instruction . In math, that may mean using visual aids and manipulatives like cubes or colored chips to help kids learn new concepts. (See more examples of multisensory math techniques .)

Some classrooms may have an interactive whiteboard. On it, kids can use their fingers to write, erase, and move images around on the large screen. This teaching tool can also be used to turn students’ work into a video, which can be exciting for kids and help keep them engaged.

2. Makes differences less “different”

Inclusive classrooms are filled with diverse learners, each of whom has strengths and challenges. Inclusion gives kids a way to talk about how everyone learns in their own way. They may find that they have more in common with other kids than they thought. This can go a long way in helping kids know that difference is just a normal part of life. It can also help kids build and maintain friendships.

3. Provides support to all students

In more traditional special education settings, many kids are “pulled out” for related services like speech therapy or for other specialized instruction. An inclusive class often brings speech therapists, reading specialists , and other service providers into the classroom.

These professionals can provide information and suggestions to help all students. If kids aren’t eligible for special education but still need some extra support, they can get it informally.

4. Creates high expectations for all

In an Individualized Education Program (IEP), a student’s goals should be based on the academic standards for their state. Those standards lay out what all students are expected to learn in math, reading, science, and other subjects by the end of the school year.

Differentiated instruction and co-teaching in a general education classroom make it easier for students with standards-based IEPs to be taught the same material as their classmates.

In some schools, only certain classrooms are designated as inclusive. In that case, schools may assign general education students randomly to inclusive or noninclusive classes. Other schools may choose students who benefit from the emphasis on meeting the needs of all learners at all ability levels.

Investigate the supports and services that might be available in an inclusive classroom. Explore the various models of collaborative team teaching .

Key takeaways

All students benefit from the resources available in an inclusive classroom.

The special education teacher can help all kids in an inclusive classroom, not just students who need special education support.

In an inclusive classroom, teachers often break students into small groups and teach them based on their specific learning needs.

Explore related topics

The Role of Special Education Teachers in Promoting an Inclusive Classroom

The adoption of inclusive education strategies—where special education students are immersed in classrooms with typically developing peers—has increased rapidly in recent decades. More than 60 percent of students with disabilities spend at least 80 percent of their school day in general education classrooms, according to the US National Center for Education Statistics.

Studies have shown that inclusive learning benefits all students in the classroom by providing thoughtful, personalized instruction and promoting individuality and equity. A student with autism might feel calmer when surrounded by a diverse peer group, while a nondisabled student might learn how to form positive relationships with a greater variety of children.

Establishing a successful integrated learning environment is a complex task involving teachers, administrators, and families. Special education and general education teachers often work together to develop a curriculum and create a positive student culture. In an inclusive classroom, special education teachers have the essential role of ensuring that students with disabilities or special needs receive a quality education.

Why Adopt Inclusive Learning?

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) states that students with individual education plans (IEPs) must be educated in the least-restrictive environments (LREs) available. Under IDEA, inclusive education (or mainstreaming) has become a standard operating procedure for US public schools. Students with IEPs can range from individuals with Down syndrome or forms of autism to those with speech impediments or dyslexia—all of which require varying levels of support.

Under IDEA, if a differently abled student’s needs can be met in a general classroom, with or without the support of a special education teacher or paraprofessional, they must be educated in that environment. When needs are not fully met in a general classroom, some students spend part of their days in a resource room or in pullout sessions, while others are educated entirely in a special education classroom.

While there is some debate about whether inclusive instruction is the best way to serve students with disabilities, there is mounting evidence that inclusive learning improves educational outcomes. Inclusive educational settings lead to stronger math and reading skills, higher attendance and graduation rates, and fewer behavioral problems, according to an evaluation of more than 280 studies from 25 countries by Abt Associates. In addition to promoting academic success for students with disabilities, inclusive learning can help improve social cognition in typically developing students.

Role of Special Education Teachers in Inclusive Classrooms

For inclusion to show positive benefits, the learning environment and instructional models must be carefully established to provide strong learning opportunities for all students. Special education and general education teachers must have mutual respect and open minds toward the philosophy of inclusion, as well as strong administrative support and knowledge of how to meet the needs of students with disabilities. The involvement of a special education teacher is crucial to the success of a combined learning environment in a number of areas:

Curriculum Design

Special education teachers help craft the lessons for inclusive classrooms to ensure that the needs of students with disabilities are considered. Teachers may work together to develop a curriculum that is accessible to all students, or the special education teacher might make modifications to the general education teacher’s lesson plans. A special education teacher will also create supplemental learning materials for specific students, including visual, manipulative, text, and technology resources, and determine when one-on-one lessons might be needed.

Teachers must examine students’ strengths, weaknesses, interests, and communication methods when crafting lessons. The students’ IEPs must be carefully followed to meet achievement goals. As many general education teachers have limited training in inclusive learning, it is important for the special education teacher to help the instructor understand why certain accommodations are needed and how to incorporate them.

Classroom Instruction

Many inclusive classrooms are based on a co-teaching model, where both teachers are present all day. Others use a push-in model, where special education teachers provide lessons at certain times during the day. It takes extensive cooperation between general and special education teachers to implement a truly inclusive classroom. Special education teachers often sit with or near students with IEPs to monitor their progress and provide any special instructions or supplemental learning materials. Students require varying levels of individual instruction and assistance, based on their unique needs.

Teachers might also pull students out of the classroom for one-on-one lessons or sensory activities, or arrange for time with counselors, speech therapists, dyslexia coaches, and other specialized personnel. Special education instructors may need to make sure that paraprofessionals or therapists are present in the classroom at certain times to assist the students. To help maintain a positive climate, they also might assist the general education teacher in presenting lessons to the entire class, grading papers, enforcing rules, and other classroom routines. General and special education teachers might break classes into smaller groups or stations to provide greater engagement opportunities.

Learning Assessments

Another role of special education teachers in inclusive classrooms is to conduct regular assessments to determine whether students are achieving academic goals. Lessons must be periodically evaluated to determine whether they are sufficiently challenging without overwhelming the students. Students should gain a feeling of self-confidence and independence in general education settings but should also feel sufficiently supported. Special education teachers also organize periodic IEP meetings with each student, their family, and certain staff members to determine whether adjustments need to be made to the student’s plan.

Advocating for Students

Special education teachers serve as advocates for students with disabilities and special needs. This includes ensuring that all school officials and employees understand the importance of inclusion and how to best implement inclusion in all campus activities. Advocacy might include requesting inclusion-focused professional development activities—especially programs that help general education teachers better understand inclusion best practices—or providing information to community members about success rates of inclusive teaching.

Communication with parents is also essential for inclusive classroom success. Families should receive regular updates on a child’s academic, social, and emotional development through phone calls, emails, and other communication means. Parents can help students prepare for classroom routines. Expectations for homework and classroom participation should be established early on.

Learn More About Inclusive Education

Special education and general education teachers can develop a greater understanding of inclusive learning and other progressive teaching methods by pursuing an advanced education degree. American University’s School of Education gives students the skills to drive meaningful change in educational environments. The school’s Master of Education in Education Policy and Leadership and Master of Arts in Teaching degrees prepare teachers to take on transformative leadership roles and create equitable learning environments for all students.

Disproportionality in Special Education: Impact on Student Performance and How Administrators Can Help

What Is Holistic Education? Understanding the History, Methods, and Benefits

What Is Lunch Shaming? How Accessibility to Lunch Impacts Student Learning

Abt Associates, “A Summary of the Evidence on Inclusive Education”

ASCD InService, “Inclusive Classrooms: Looking at Special Education Today”

Houston Chronicle, “The Role of a Special Ed Teacher in an Inclusion Classroom”

EducationNext, “Has Inclusion Gone Too Far?”

Education Week, “Students with Disabilities Deserve Inclusion. It’s Also the Best Way to Teach”

Noodle, “The Benefits of Inclusive Education: What Special Education Teachers Need to Know”

Understood, “4 Benefits of Inclusive Classrooms”

Request Information

AU Program Helper

This AI chatbot provides automated responses, which may not always be accurate. By continuing with this conversation, you agree that the contents of this chat session may be transcribed and retained. You also consent that this chat session and your interactions, including cookie usage, are subject to our privacy policy .

Special Education Guide

What’s Inclusion? Theory and Practice

When journeying into the realm of special education you will almost certainly come across the term inclusion. Parents, you may stumble upon the word while trying to determine what possibilities exist for your child. Teachers, you likely encounter inclusion every year when you receive your class roster, identify the students with individualized education programs (IEPs) and evaluate how you can best instruct your class. At times the process may seem like a hassle, spawned by a politically-correct society. On the other hand, disability advocates eagerly argue for inclusion, pointing to the benefits the practice offers.

Understanding Inclusion

Before you can enter the debate on inclusion, you must first understand what inclusion is. Effectively grasping this concept entails two tasks: defining inclusion and understanding the theory behind the concept. The Wisconsin Education Association Council (WEAC) defines inclusion as “a term which expresses commitment to educate each child, to the maximum extent appropriate, in the school and classroom he or she would otherwise attend.”

Supporters of inclusion maintain that it is a civil rights issue—recognizing the rights that people with disabilities deserve. These rights include equal access and equal opportunity. The first attempt to secure equal access and equal opportunity inside schools originated with a law passed in 1975, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act. This legislation was revised in in 1990, 1997 and 2004, and was renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). On the other side of the inclusion theory is the fact that nowhere within IDEA is the term “inclusion” mentioned. The law asks that each child be educated in the least restrictive environment; the very least restrictive environment is the general education classroom.

One significant difference between the original 1975 regulation and current-day IDEA involves the level of requirements placed upon schools. Generally speaking, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act resulted in segregated classrooms, although that was not a mandate of the law, rather entry into a relatively unknown field of education. However, as other civil rights movements have shown, separate does not mean equal. IDEA has had reauthorizations with each moving the language to placing more emphasis upon the general education classroom and general education curriculum. While often confused—even by educators—there still remains no specific reference to inclusion or location of services to disabled children, other than “least restrictive environment.”

Putting Inclusion into Practice

IDEA doesn’t necessarily mandate inclusion. Given the vast discrepancies within the realm of special needs, the “least restrictive environment” is determined on a case-by-case basis. Practicality plays a big role in deciding whether an inclusive environment best suits a child. Parents, you alone do not get to make this decision. At the same time, neither does your school’s administration. Everyone on a child’s IEP team collaborates to reach a verdict. (See The IEP Process Explained to learn all about IEPs.)

Two major sections of the IEP help to determine if inclusion is right for the child or not. The first is the legal definition of special education: “specially designed instruction.” Whether the child is placed in a general education classroom or pulled out for some other form of service, he or she MUST receive specially designed instruction in his or her area(s) of weakness. Some inclusion advocates tend to consider only adaptations and modifications, however, if only those are provided, then the child is not receiving special education.

The adaptations needed by a student prove quite vital when considering his or her classroom placement. These come in two forms: accommodations and modifications. Essentially, they assist students with special needs by compensating for any disability-related obstacles, giving students the tools to excel. After all, a pupil with special needs is unlikely to thrive if he or she is simply dumped into a general education classroom. (For an in-depth look at adaptations and the differences between accommodations and modifications read Adaptations, Accommodations, and Modifications .)

The Anti-Inclusion Argument

As previously mentioned, debate exists over inclusion. Common anti-inclusion arguments involve concern over how inclusion will change the learning environment for other students, as well concerns centering on the expenses of inclusion. For instance, in “ Inclusion in the Classroom ,” the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities lists “fear that general education classrooms will be disrupted if students with disabilities are included” as a barrier to inclusion.

WEAC offers an example of an anti-inclusion argument centering on financial motives as it describes the view of James Kauffman of the University of Virginia: inclusion is “a policy driven by an unrealistic expectation that money will be saved.” The Vanderbilt Kennedy Center provides another example of a financially-based concern, naming lack of funding as a reason that schools might not support the adaptations needed for inclusion.

There is considerable research evidence that inclusionary practices are at least as effective as those provided by a pull-out delivery method. While this is true, most the research is new and more needs to be completed to fully understand what might be best for children with special needs.

The Pro-Inclusion Argument

Meanwhile, those who support inclusion point to the benefits which result from incorporating students with disabilities into general education classrooms. Educators and all students (essentially, everybody) benefits through interacting with different people. Integrating students with disabilities into the classroom may also force teachers to leave their comfort zones and learn new techniques to become better instructors.

Proponents of inclusion cite enhanced social interaction as a big benefit for students of all levels of ability. Friendships, otherwise unimaginable, form, and these bonds allow kids to understand diversity in ways that textbooks and formal classroom lectures can’t. While not a traditional subject such as math and science, diversity proves important in creating an open-minded society. Throughout their lives, students will encounter others who do not think or act as they do; by learning how to work and interact with these individuals, they gain an advantage not only in the classroom, but also in life in general.

Inclusion can also trigger enhanced collaboration between educators. For example, if a child has a learning disability that makes it difficult to read, his or math teacher may need to confer with other teachers to find a way to help that student with word problems.

Perhaps the most important benefit of inclusion rests in the academic benefits for students with special needs. These students become engaged in their education as opposed to staying unchallenged inside segregated classrooms. In other words, inclusion gives students with disabilities the best chances to thrive academically.

There is also a newly developed body of evidence derived from co-teaching, where the special education teacher joins with the general education teacher for areas of student weakness. The team approach is proving to be possibly one of the best methods of including special education students, while providing both accommodations and modifications and specially designed instruction.

NASET.org Home Page

Exceptional teachers teaching exceptional children.

- Overview of NASET

- NASET Leadership

- Directors' Message

- Books by the Executive Directors

- Mission Statement

- NASET Apps for iPhone and iPad

- NASET Store

- NASET Sponsors

- Marketing Opportunities

- Contact NASET

- Renew Your Membership

- Membership Benefits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Membership Categories

- School / District Membership Information

- Gift Membership

- Membership Benefit for Professors Only

- NASET's Privacy Policy

- Forgot Your User Name or Password?

- Contact Membership Department

- Resources for Special Education Teachers

- Advocacy (Board Certification for Advocacy in Special Education) BCASE

- Board Certification in Special Education

- Inclusion - Board Certification in Inclusion in Special Education (BCISE) Program

- Paraprofessional Skills Preparation Program - PSPP

- Professional Development Program (PDP) Free to NASET Members

- Courses - Professional Development Courses (Free With Membership)

- Forms, Tables, Checklists, and Procedures for Special Education Teachers

- Video and Power Point Library

- IEP Development

- Exceptional Students and Disability Information

- Special Education and the Law

- Transition Services

- Literacy - Teaching Literacy in English to K-5 English Learners

- Facebook - Special Education Teacher Group

- NASET Sponsor's Products and Services

- ADHD Series

- Assessment in Special Education Series

- Autism Spectrum Disorders Series

- Back to School - Special Review

- Bullying of Children

- Classroom Management Series

- Diagnosis of Students with Disabilities and Disorders Series

- Treatment of Disabilities and Disorders for Students Receiving Special Education and Related Services

- Discipline of Students in Special Education Series

- Early Intervention Series

- Genetics in Special Education Series

- How To Series

Inclusion Series

- IEP Components

- JAASEP - Research Based Journal in Special Education

- Lesser Known Disorders

- NASET NEWS ALERTS

- NASET Q & A Corner

- Parent Teacher Conference Handouts

- The Practical Teacher

- Resolving Disputes with Parents Series

- RTI Roundtable

- Severe Disabilities Series

- Special Educator e-Journal - Latest and Archived Issues

- Week in Review

- Working with Paraprofessionals in Your School

- Author Guidelines for Submission of Manuscripts & Articles to NASET

- SCHOOLS of EXCELLENCE

- Exceptional Charter School in Special Education

- Outstanding Special Education Teacher Award

- Board Certification Programs

- Employers - Job Posting Information

- Latest Job Listings

- Professional Development Program (PDP)

- Employers-Post a Job on NASET

- PDP - Professional Development Courses

- Board Certification in Special Education (BCSE)

- Board Certification in IEP Development (BCIEP)

- NASET Continuing Education/Professional Development Courses

- HONOR SOCIETY - Omega Gamma Chi

- Other Resources for Special Education Teaching Positions

- Highly Qualified Teachers

- Special Education Career Advice

- Special Education Career Fact Sheets

- FAQs for Special Education Teachers

- Special Education Teacher Salaries by State

- State Licensure for Special Education Teachers

Go to the PDP Menu

Introduction.

NASET is proud to offer a new series devoted exclusively to the concept of inclusion as a special education setting and working in an inclusive setting.. This series will cover all aspects of inclusion focusing especially on understanding this population and what skills and information are necessary if you are asked to teach this population of students. However, to understand who is included in this population we must first clarify several concepts, definitions, and foundational issues.

At the end of this series you should:

- Understand concepts and terminology associated with inclusion.

- Understand the different categories of exceptional students. To understand historical and legal development of special education and its relevance in today’s schools.

- To understand contemporary issues of educating students with mild disabilities, including foundations, theories, and conceptual models.

- To understand the purpose and procedures for screening, pre-referral, referral, identification, and placement of students with mild disabilities.

- To understand concepts and definitions, prevalence, and causes of mild disabilities.

- To understand the legal rights of persons with mild disabilities.

- To understand the related service options for children with mild disabilities

- To gain knowledge of the physical, cognitive, and learning characteristics of persons with severe/profound disabilities

- To be able to identify components of Individual Educational Plans for students with mild disabilities.

- To develop instructional strategies and tactics for teaching the acquisition of new behaviors and skills to students with mild disabilities.

- To develop skills for independently seeking information about educational and related services for students with mild disabilities.

- To understand the procedures for developing, implementing and amending Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) for students with disabilities.

- To understand methods of planning and managing teaching/learning environments for students with disabilities.

- To become familiar with the use of instructional technology to differentiate instruction.

- To become familiar with the use of assistive technology to facilitate instruction.

- To become familiar with the development and implementation of positive behavioral interventions.

As you progress through this series, you will be presented with principles, foundations, classroom management techniques and other practical factors for working with students in an inclusive setting.

Latest and Archived Issues

Latest issue: promoting success: the role of advocacy and family involvement in fostering academic and social development for students with down syndrome, archived issues:, enhancing inclusion: a comprehensive literature review on supporting students with disabilities in mainstream classrooms click here, inclusiveness for students with autism spectrum disorders click here, manifestation determination click here, help get me out of here: inclusion in the high school environment click here, how culture affects inclusion: a literature review click here, partnering for greatness - click here, learners with special gifts and talents click here, exceptional students - click here, least restrictive environment placements - click here, accommodations, modification and supports for students with disabilities - click here, alternative educational delivery systems - click here, promoting positive social interactions in an inclusion setting for students with learning disabilities - click here, teaching students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder - click here, teaching students with emotional and behavioral disorders - click here, teaching students with intellectual disabilities - click here, teaching students with learning disabilities - click here, learners with autism spectrum disorders - click here, learners with communication disorders - click here, discipline of students with disabilities - click here, integrated co-teaching services - click here, challenges to collaboration, inclusion and best practices within the special education community - click here, preschool inclusion videos - click here, publications.

- Inclusion Series- Exceptional Students

- Inclusion Series- Least Restrictive Environment Placements

- Inclusion Series- Accommodations, Modifications and Supports for Students with Disabilities

- Inclusion Series- Alternative Educational Delivery Systems

- Inclusion Series- Promoting Positive Social Interactions in an Inclusion Setting for Students with Learning Disabilities

- Inclusion Series- Teaching Students with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

- Inclusion Series- Teaching Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- Inclusion Series- Teaching Students with Intellectual Disabilities

- Inclusion Series- Teaching Students with Learning Disabilities

- Inclusion Series - Learners with Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Inclusion Series- Learners with Communication Disorders

- Inclusion Series- Discipline of Students with Disabilities

- Inclusion Series- Learners with Special Gifts and Talents

- Inclusion Series- Integrated Co-Teaching Services

- Inclusion Series- Partnering for Greatness

- Inclusion Series- Challenges to Collaboration, Inclusion and Best Practices within the Special Education Community

- Inclusion Series- Preschool Inclusion Videos

- Inclusion Series- How Culture Affects Inclusion: A Literature Review

- Inclusion Series- Help! Get Me Out of Here: Inclusion in the High School Environment

- Inclusion Series- Manifestation Determination

- Inclusion Series- Inclusiveness for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Inclusion Series- Enhancing Inclusion: A Comprehensive Literature Review on Supporting Students with Disabilities in Mainstream Classrooms

- Inclusion Series- Promoting Success: The Role of Advocacy and Family Involvement in Fostering Academic and Social Development for Students with Down Syndrome

©2024 National Association of Special Education Teachers. All rights reserved

- Skip to Nav

- Skip to Main

- Skip to Footer

New research review questions the evidence for special education inclusion

Please try again

For the past 25 years, U.S. policy has urged schools to keep students with disabilities in the same classrooms with their general education peers unless severe disabilities prevent it. It seems a humane policy not to wall off those with disabilities and keep them apart from society. Who would argue against it?

Schools have embraced inclusion. According to the most recent data from 2020-21 school year, two thirds of the 7 million students with disabilities who receive special education services spent 80% or more of their time in traditional classrooms. Separation is less common today; only one out of every eight students with disabilities was taught separately in a special-needs only environment most of the time.

But a recent international analysis of all the available research on special education inclusion found inconsistent results. Some children thrived while others did very badly in regular classrooms. Overall, students didn’t benefit academically, psychologically or socially from the practice. Math and reading scores, along with psychosocial measures, were no higher for children with disabilities who learned in general education classrooms, on average, compared to children who learned in separate special education classrooms.

“I was surprised,” said Nina Dalgaard, lead author of the inclusion study for the Campbell Collaboration , a nonprofit organization that reviews research evidence for public policy purposes. “Despite a rather large evidence base, it doesn’t appear that inclusion automatically has positive effects. To the contrary, for some children, it appears that being taught in a segregated setting is actually beneficial.”

Many disability advocates balked at the findings, published in December 2022, on social media. An influential lobbying organization, the National Center for Learning Disabilities, said it continues to believe that inclusion is beneficial for students and that this study will “not change” how the disability community advocates for students.

“Students with disabilities have a right to learn alongside their peers, and studies have shown that this is beneficial not only for students with disabilities but also for other students in the classroom,” said Lindsay Kubatzky, the organization’s director of policy and advocacy.

“Every student is different, and ‘inclusion’ for one student may look different from others. For some, it could be a classroom separate from their peers, but that is rarely the case.”

The Campbell Collaboration study is a meta-analysis, which means it is supposed to sweep up all the best research on a topic and use statistics to tell us where the preponderance of the evidence lies. Dalgaard, a senior researcher at VIVE—The Danish Centre for Social Science Research, initially found over 2,000 studies on special education inclusion. But she threw out 99 percent of them, many of which were quite favorable to inclusion. Most were qualitative studies that described students’ experiences in an inclusion classroom but didn’t rigorously track academic progress. Among those that did monitor math or reading, many of them simply noted how much students improved in an inclusive setting, but didn’t compare those gains with how students might have otherwise fared in a separate special-needs only setting.

Fewer than 100 studies had comparison groups, but still most of those didn’t make the cut because the students in inclusive settings were vastly different from those in separate settings. Special education is a particularly difficult area to study because researchers cannot randomly assign students with disabilities to different treatments. Schools tend to keep children with milder disabilities in a regular classroom and teach only those with the most severe disabilities separately. In comparing how both groups fare, it should be no surprise that students with milder disabilities outperform those with more severe disabilities. But that’s not good evidence that inclusion is better. “It’s a serious, confounding bias,” Dalgaard said.

In the end, Dalgaard was left with only 15 studies where the severity of the disability was somehow noted so that she could compare apples to apples. These 15 studies covered more than 7,000 students, ages six through 16, across nine countries. Four of the studies were conducted in the United States with the others in Europe.

The disabilities in the studies ranged widely, from the most common ones, such as dyslexia, ADHD, speech impairments and autism, to rarer ones, such as Down syndrome and cerebral palsy. Some students had mild versions; others had more severe forms. I asked Dalgaard if she found clues in the results as to which disabilities were more conducive to inclusion. I was curious if children with severe dyslexia, for example, might benefit from separate instruction with specially trained reading teachers for the first couple of years after diagnosis.

Dalgaard said there wasn’t enough statistical evidence to untangle when inclusion is most beneficial. But she did notice in the underlying studies that students with autism seem to be better off in a separate setting. For example, their psychosocial scores were higher. But more studies would be needed to confirm this.

She also noticed that how a school goes about including students with disabilities mattered. In schools that used a co-teaching model, one regular teacher and one trained in special education, students fared better in inclusion classrooms. Again, more research is needed to confirm this statistically. And, even if co-teaching proves to be effective over multiple studies, not every school can afford to hire two teachers for every classroom. It’s particularly cost-prohibitive in middle and high school as teachers specialize in subjects.

Instead, Dalgaard noted that inclusion is often a cost-cutting practice because schools save money when they no longer run separate classrooms or schools for children with disabilities. “In some cases, children with disabilities no longer had access to the same resources. It’s not supposed to happen this way, but it does in some places,” said Dalgaard. “That is probably why the results of the meta-analysis show that some children actually learn more in segregated settings.”

I was surprised to learn from Dalgaard that no sound meta-analysis has found “clear” benefits for special education inclusion. Indeed, previous meta-analyses have found exactly the same inconsistent or very small positive results, she said. This latest Campbell Collaboration study was commissioned to see if newer research, published from 2000 to September 2021, would move the dial. It did not.

As a nation, we spend an estimated $90 billion a year in federal, state and local taxpayer funds on educating children with disabilities. We ought to know more about how to best help them learn.

*Correction: This story has been updated with the correct spelling of Lindsay Kubatzky’s name.

This story about special education inclusion was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter .

We track anonymous visitor behavior on our website to ensure you have a great experience. Learn more about our Privacy Policy .

- The Learning Accelerator

- Resources & Guidance

- Parabola Project

- What can teaching and learning practice look like?

- What are the conditions needed for success?

- How can blended learning help?

- How can I support quality remote and hybrid learning?

- Lovett Elementary School

- Trailblazer Elementary School

- The Forest School Online

- Valor Collegiate Academies

- ASU Prep Digital

- Lindsay High School

- Laurel Springs School

- Pleasant View Elementary School

- My Tech High

- CICS West Belden

- Bronx Arena High School

- Map Academy

- ReNEW DTA Academy

- Virtual Learning Academy Charter School (VLACS)

- Cisco Junior High School

- Locust Grove Middle School

- Crossroads FLEX High School

- Roots Elementary

- Gem Prep Online

- LPS Richmond

- Texas Tech University K-12

- Montana Digital Academy

- Cajon Valley Home School Program

- Valor Preparatory Academy of Arizona

- Teaching & Learning Practices

- Conditions for Success & Scale

- Train Your People

- Research & Measurement

- Learning Commons

- Problems of Practice

- Targeted and Relevant

- Differentiated pathways and materials

Full Inclusion of Students with Learning Disabilities

Providing special education resources to students with additional need in general education classrooms

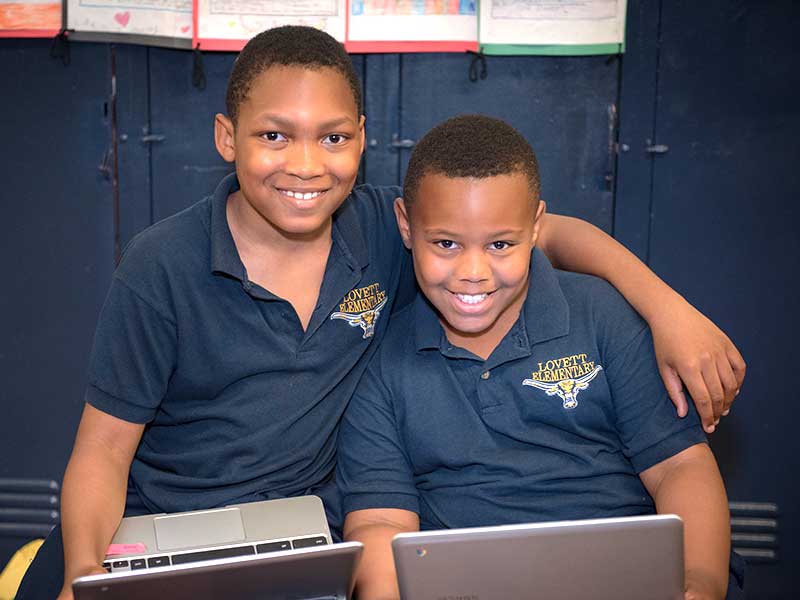

Lovett operates in a full inclusion model for their students with learning disabilities (those who have an Individualized Education Plan or “IEP”). All students are fully integrated into the general education classrooms, and no students are pulled out of the general education classroom for special instruction.

Recognizing that nearly all of their students have unique learning needs, regardless of IEP status, Lovett tries to incorporate as many adults in the classroom as possible, including those who might traditionally serve students with learning disabilities. This includes the general education teacher, special education teacher, aides, and student teachers from University of Illinois at Chicago . Given that Lovett operates within a blended rotation model, these adults can all help promote learning in different ways (facilitating small groups, prompting independent work, etc.), allowing special attention to be paid to those that need it. Not only does this approach better meet the needs of all students, but it also reduces the stigma around being a students with learning disabilities as students recognize that everyone sometimes needs special help.

(This Approach is Illustrative of LEAP's Learner Focused Strategies)

Student Does

- Students with learning disabilities have an Individualized Education Plan and may receive modified instruction based on that plan.

Students are grouped based on instructional need, so a group may contain a mix of students with and without IEPs (students do not know who has one and who doesn’t).

Teacher Does

- Special education teachers support four or five classrooms.

Special education teachers create a weekly schedule to ensure all of his or her students are getting the support they need (based on their Individualized Education Plan).

Special education and general education teachers coordinate during weekly planning sessions to figure out the best time for special education teachers to be in the classroom.

Special education teachers work in classrooms addressing students with the lowest skill levels during core content blocks when students are grouped based on abilities . This practice often enables them to reach all of their students in a single classroom.

All teachers modify content and instruction based on individual student needs .

Technology Does

- Provides data via online programs on student progress for individual skills, helping to identify student needs.

Provides NWEA data to help teachers understand which students need the most support in certain skill areas.

Featured Artifact

Blended benefits for students with learning differences at lovett.

Lovett educators discuss the benefits of a blended environment for their students with learning differences. Learn More

Strategy Resources

Teacher planning to meet the needs of students with learning differences at lovett.

Lovett educators discuss how they plan throughout the week to meet the needs of their... Learn More

Multiple Adults in the Classroom at Lovett

Lovett strives to maximize the number of educators in the classroom. This video discusses "why"... Learn More

Lovett Elementary in Chicago provides blended and personalized learning to its students in grades 2-5.

- Our Mission

Special Education: Promoting More Inclusion at Your School

It is all too rare for discussions of school culture and climate and SEL to focus explicitly on students with disabilities. A shining exception is the Inclusive Schools Climate Initiative (ISCI), a pilot project at Rutgers University, developed through a partnership with the Office of Special Education Programs at the NJ Department of Education. Eighteen schools are involved in the pilot project, and each one carries out an inclusion-focused assessment of school climate, the formulation of an ISCI leadership team, and the development and implementation of a School Climate Improvement Plan (SCIP).

SCIP's are unique to each school and include goals and a range of activities that are designed to promote changes or to sustain aspects of school climate that best support inclusion. I am pleased to be able to share what I have learned through conversations with Dr. Lerman, who is the director of ISCI.

Maurice Elias: Why was it important to develop inclusive schools?

Dr. Lerman: It is now absolutely clear that the success of students with disabilities in more inclusive settings depends on meeting both their academic and social and emotional needs. This, in turn, requires a school climate that is a psychologically inclusive space where all students better understand one another, feel safe and supported, have positive relationships, and are more respectful and accepting of each other.

How has the ISCI pilot addressed school climate, specifically to support inclusion?

A key part of improving school climate is to assess. The ISCI is piloting a school climate assessment that is unique in its focus on the dimensions that are important for included students' success. These include: supportive relationships, a strong sense of connectedness to school, the development of positive social skills and pro-social behaviors, workplace settings where teachers and staff have positive relationships and feel respected and valued, perceptions of disabilities, and perceptions of the extent to which the school is inclusive. All students, teachers, certified and non-certified staff, administrators, and parents should have input by completing surveys tailored to them.

How can SEL be used by schools to make them more inclusive?

Some practical ideas for educators include organizing homeroom periods to be inclusive.

Also, classrooms should have programs of disability awareness at the beginning of the school year, and then adapt this if new included children come in later on in the year. This involved education all students about disabilities/abilities, emphasizing everyone's strengths, having 2-3 "buddies" for students with disabilities to make sure they are included and seen as part of the mainstream, as well as to provide them with social-emotional and academic assistance.

These "buddying" responsibilities can be rotated by marking period and extend outside the classroom to all parts of the school building, the bus, and extracurricular activities. Teachers should also be prepared to ensure that the students with disabilities are not isolated. This can be accomplished through strategic seating arrangements and monitoring overall classroom interaction patterns.

Here are other ideas:

- Increasing inclusion in elective classes, such as choir and art, by increasing the number of students with disabilities involved and engaged in these activities alongside students in general education programs. Again, buddying in these specialized classes is a very effective support strategy that benefits all involved. In some schools, servicing as a buddy can be counted as part of school service.

- Creating a more inclusive UNITY Club to recognize and appreciate the differences between people. Unity Clubs usually focus on cultural and ethnic diversity. By including students with disabilities in these clubs, another area of diversity can be addressed. Schools also may wish to explore Project UNIFY , run by Special Olympics, which provides excellent materials for unified and inclusive sports and youth leadership and service programs.

- Implementing a cross-age Reading Buddies program; most often, this is designed for kindergarten and upper-level elementary students to increase their vocabulary, develop their self-esteem and social skills, and enhance their love of books and reading. Students with disabilities can be either the reader or the recipient. In some cases, older students without disabilities read to younger students with disabilities. In other cases, older students with disabilities read to younger students with and without disabilities.

- Implementing a mentoring program where high school students with disabilities mentor middle school students with and without disabilities in an after-school program.

- Developing inclusive Service-Learning Projects so that general education and special education students work together and reflect on service initiatives. Also implementing increased levels of professional development that focus on issues such as diversity and disability.

Also, faculty are often less prepared to understand and work with students with disabilities than one might expect. Use faculty meetings and professional learning communities meetings to increase knowledge regarding disabilities, improved teaching techniques, and better classroom management techniques.

Reviewing content areas and highlight literature at all age levels that focus on empathy, diversity, disability, including writing assignments related to this literature, emphasize key figures in science (e.g., Einstein) and public life (e.g., Nelson Rockefeller, Franklin Roosevelt) with learning and other disabilities, and incorporate into the physical education curriculum an understanding of Special Olympics and its rationale and international, national and state-level presence, and consider more of a focus on unified sports.

Also important: broadening school-wide recognition systems to include students with disabilities. Review and expand how to honor student achievements around civic responsibility and character, positive behavior and resilience in the face of pressures. Rewards can include lunch with the principal or community leaders or first responders or college students.

Benefits and Costs of More Inclusion

The above suggestions are only some of many that the ISCI has implemented, and Brad Lermen is available ( [email protected] ) to follow up on these and others, including linking interested individuals with schools implementing specific ideas.

The costs are minimal and the benefits are felt mainly in the heart and soul of students and staff alike who resonate to doing the right thing and seeing the sparkling eyes and appreciative warmth of the included students. That said, this work is not an inoculation.

Great attention must be given to the schools to which included students will be transitioning, to help those schools to also have a more inclusive climate. However, as they will soon find, being asked to be more inclusive is at least as beneficial for those providing inclusion as it is for those receiving it.

The Hechinger Report

Covering Innovation & Inequality in Education

PROOF POINTS: New research review questions the evidence for special education inclusion

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

The Hechinger Report is a national nonprofit newsroom that reports on one topic: education. Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get stories like this delivered directly to your inbox. Consider supporting our stories and becoming a member today.

Get important education news and analysis delivered straight to your inbox

- Weekly Update

- Future of Learning

- Higher Education

- Early Childhood

- Proof Points

For the past 25 years, U.S. policy has urged schools to keep students with disabilities in the same classrooms with their general education peers unless severe disabilities prevent it. It seems a humane policy not to wall off those with disabilities and keep them apart from society. Who would argue against it?

Schools have embraced inclusion. According to the most recent data from 2020-21 school year, two thirds of the 7 million students with disabilities who receive special education services spent 80 percent or more of their time in traditional classrooms. Separation is less common today; only one out of every eight students with disabilities was taught separately in a special-needs only environment most of the time.

But a recent international analysis of all the available research on special education inclusion found inconsistent results. Some children thrived while others did very badly in regular classrooms. Overall, students didn’t benefit academically, psychologically or socially from the practice. Math and reading scores, along with psychosocial measures, were no higher for children with disabilities who learned in general education classrooms, on average, compared to children who learned in separate special education classrooms.

“I was surprised,”said Nina Dalgaard, lead author of the inclusion study for the Campbell Collaboration , a nonprofit organization that reviews research evidence for public policy purposes. “Despite a rather large evidence base, it doesn’t appear that inclusion automatically has positive effects. To the contrary, for some children, it appears that being taught in a segregated setting is actually beneficial.”

Many disability advocates balked at the findings, published in December 2022, on social media. An influential lobbying organization, the National Center for Learning Disabilities, said it continues to believe that inclusion is beneficial for students and that this study will “not change” how the disability community advocates for students.

“Students with disabilities have a right to learn alongside their peers, and studies have shown that this is beneficial not only for students with disabilities but also for other students in the classroom,” said Lindsay Kubatzky, the organization’s director of policy and advocacy. “Every student is different, and ‘inclusion’ for one student may look different from others. For some, it could be a classroom separate from their peers, but that is rarely the case.”

The Campbell Collaboration study is a meta-analysis, which means it is supposed to sweep up all the best research on a topic and use statistics to tell us where the preponderance of the evidence lies. Dalgaard, a senior researcher at VIVE—The Danish Centre for Social Science Research, initially found over 2,000 studies on special education inclusion. But she threw out 99 percent of them, many of which were quite favorable to inclusion. Most were qualitative studies that described students’ experiences in an inclusion classroom but didn’t rigorously track academic progress. Among those that did monitor math or reading, many simply noted how much students improved in an inclusive setting, but didn’t compare those gains with how students might have otherwise fared in a separate special-needs-only setting.

Fewer than 100 studies had comparison groups, but still most of those didn’t make the cut because the students in inclusive settings were vastly different from those in separate settings. Special education is a particularly difficult area to study because researchers cannot randomly assign students with disabilities to different treatments. Schools tend to keep children with milder disabilities in a regular classroom and teach only those with the most severe disabilities separately. In comparing how both groups fare, it should be no surprise that students with milder disabilities outperform those with more severe disabilities. But that’s not good evidence that inclusion is better. “It’s a serious, confounding bias,” Dalgaard said.

In the end, Dalgaard was left with only 15 studies where the severity of the disability was somehow noted so that she could compare apples to apples. These 15 studies covered more than 7,000 students, ages six through 16, across nine countries. Four of the studies were conducted in the United States with the others in Europe.

The disabilities in the studies ranged widely, from the most common ones, such as dyslexia, ADHD, speech impairments and autism, to rarer ones, such as Down syndrome and cerebral palsy. Some students had mild versions; others had more severe forms. I asked Dalgaard if she found clues in the results as to which disabilities were more conducive to inclusion. I was curious if children with severe dyslexia, for example, might benefit from separate instruction with specially trained reading teachers for the first couple of years after diagnosis.

Dalgaard said there wasn’t enough statistical evidence to untangle when inclusion is most beneficial. But she did notice in the underlying studies that students with autism seem to be better off in a separate setting. For example, their psychosocial scores were higher. But more studies would be needed to confirm this.

She also noticed that how a school goes about including students with disabilities mattered. In schools that used a co-teaching model, one regular teacher and one trained in special education, students fared better in inclusion classrooms. Again, more research is needed to confirm this statistically. And, even if co-teaching proves to be effective over multiple studies, not every school can afford to hire two teachers for every classroom. It’s particularly cost-prohibitive in middle and high school as teachers specialize in subjects.

Instead, Dalgaard noted that inclusion is often a cost-cutting practice because schools save money when they no longer run separate classrooms or schools for children with disabilities. “In some cases, children with disabilities no longer had access to the same resources. It’s not supposed to happen this way, but it does in some places,” said Dalgaard. “That is probably why the results of the meta-analysis show that some children actually learn more in segregated settings.”

I was surprised to learn from Dalgaard that no sound meta-analysis has found “clear” benefits for special education inclusion. Indeed, previous meta-analyses have found exactly the same inconsistent or very small positive results, she said. This latest Campbell Collaboration study was commissioned to see if newer research, published from 2000 to September 2021, would move the dial. It did not.

As a nation, we spend an estimated $90 billion a year in federal, state and local taxpayer funds on educating children with disabilities. We ought to know more about how to best help them learn.

This story about special education inclusion was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter .

Related articles

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

Jill Barshay SENIOR REPORTER

(212)... More by Jill Barshay

Letters to the Editor

At The Hechinger Report, we publish thoughtful letters from readers that contribute to the ongoing discussion about the education topics we cover. Please read our guidelines for more information. We will not consider letters that do not contain a full name and valid email address. You may submit news tips or ideas here without a full name, but not letters.

By submitting your name, you grant us permission to publish it with your letter. We will never publish your email address. You must fill out all fields to submit a letter.

re: https://hechingerreport.org/proof-ponts-new-research-review-questions-the-evidence-for-special-education-inclusion/ Ref: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cl2.1291 The effects of inclusion on academic achievement, socioemotional development and wellbeing of children with special educational needs

Jill Barshay, Hechinger Reports cc Dr. Nina Dalgaard

It is important to conduct periodic meta-analysis of topics related to public policy, funding and other aspects of education.

I disagree with the reporting by Jill Bashay regarding special education learner inclusion/exclusion.

The reason for my disagreement is that the referenced study authors report contains the authors’ data collection and meta-analysis conclusions (see below) that valid information for meta-analysis is inadequate. My read of the Dalgaard met-analysis report suggests that the two extremes – full inclusion or full exclusion – of SEN students in the ‘normal’ population may be harmful but is really unknown. Therefore, until more and better research is achieved, some logical blend of inclusion/exclusion can be designed and implemented to achieve learning and social integration objectives. My opinion comes from leading manufacturing ventures that have intentionally accommodated “SEN” adults successfully in ways that give them personal work settings along with collaborative opportunities. The emotional intelligence for diversity, equity and inclusion is, I believe, better achieved by starting in the K-12 system.

Larry Gebhardt Ph.D., Captain US Navy (Retired) Pocatello, Idaho

Data Collection and Analysis The total number of potentially relevant studies constituted 20,183 hits. A total of 94 studies met the inclusion criteria, all were non-randomised studies. The 94 studies analysed data from 19 different countries. Only 15 studies could be used in the data synthesis. Seventy-nine studies could not be used in the data synthesis as they were judged to be of critical risk of bias and, in accordance with the protocol, were excluded from the meta-analysis on the basis that they would be more likely to mislead than inform. The 15 studies came from nine different countries. Separate meta-analyses were conducted on conceptually distinct outcomes. All analyses were inverse variance weighted using random effects statistical models. Sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the robustness of pooled effect sizes across components of risk of bias.

Authors’ Conclusions The overall methodological quality of the included studies was low, and no experimental studies in which children were randomly assigned to intervention and control conditions were found. The 15 studies, which could be used in the data synthesis, were all, except for one, judged to be in serious risk of bias. Results of the meta-analyses do not suggest on average any sizeable positive or negative effects of inclusion on children’s academic achievement as measured by language, literacy, and math outcomes or on the overall psychosocial adjustment of children. The average point estimates favoured inclusion, though small and not statistically significant, heterogeneity was present in all analyses, and there was inconsistency in direction and magnitude of the effect sizes. This finding is similar to the results of previous meta-analyses, which include studies published before 2000, and thus although the number of studies in the current meta-analyses is limited, it can be concluded that it is very unlikely that inclusion in general increases or decreases learning and psychosocial adjustment in children with special needs. Future research should explore the effects of different kinds of inclusive education for children with different kinds of special needs, to expand the knowledge base on what works for whom.

Of course inclusion, just in general, doesn’t increase outcomes. Just like exclusion, just in general, doesn’t help anyone. So many other things have to be true. What the kids and adults are actually doing when they are being ‘included,’ matters the most. Is there one general education teacher with 25 kids and kids with disabilities are just in class receiving whole group instruction without any targeted supports? Is there a strong co-teaching model led by two content experts with most time spent in small groups? Is the special educator a content expert? If you think about what is true about a self-contained classroom that would, arguably, be better for a student, those things can be replicated within a general education setting. As a school leader, professor, former self-contained, and inclusion teacher, there is no arguing with the notion that a non-verbal student with autism is NOT categorically better off in an autism classroom than in an inclusion classroom with strong language models. The structure of the classroom and the roles of adults have to be strategically designed so that kids benefit from any classroom structure, inclusion or otherwise. I have trained hundreds of school leaders all across the country and have learned that most schools don’t know how to do inclusion well. Let’s talk about that.

I am in total agreement with Tony Barton’s comment. Jill Barshay’s article reinforced what we know: that the right set-up plays a critical role in the outcome. Therefore, since there are so few properly conducted studies, we must focus our attention to ensure that our students with disabilities are all in settings that are conducive to progress in all domains- academically, psychologically and socially. Ensuring all our educators are properly trained is the first step. I have also found that I will create the learning environment for each struggling student based on the current conditions – and include each student’s personality traits as part of the assessment done to determine where the student will truly feel best and progress most. This is similar to a general statement regarding pain. One can never compare his pain to another since pain is physiological and cannot be measured via comparison. Since the personality and individual abilities of the student, teacher, assistant and special educator all will impact the student’s outcome- it is hard to measure and determine where success is most feasible without being aware of all variables. I agree that most schools don’t know how to do inclusion well- or don’t have the staff to properly support it. This article is great in raising our collective awareness of why the Campbell Study couldn’t be more targeted and concise with its results and what we can do to support our students best.