The computer revolution: how it's changed our world over 60 years

![write a term paper on how the computer as revolutionize the practice mass communication The BlueGene/L supercomputer is presented to the [media] at the Lawerence Livermore National Laboratory in Livermore, California, October 27, 2005. The BlueGene/L is the world's fastest supercomputer and will be used to ensure [U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile] is safe and reliable without testing. The BlueGene/L computer made by IBM can perform a record 280.6 trillion operations per second.](https://assets.weforum.org/article/image/large_2JLMYGrCYRb1GpPLelIHRm1J15hLVXSttNz3qV_Gu54.jpg)

The BlueGene/L supercomputer can perform 280.6 trillion operations per second. Image: REUTERS/KimberlyWhite

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Justin Zobel

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Digital Communications is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, digital communications.

It is a truism that computing continues to change our world. It shapes how objects are designed, what information we receive, how and where we work, and who we meet and do business with. And computing changes our understanding of the world around us and the universe beyond.

For example, while computers were initially used in weather forecasting as no more than an efficient way to assemble observations and do calculations, today our understanding of weather is almost entirely mediated by computational models.

Another example is biology. Where once research was done entirely in the lab (or in the wild) and then captured in a model, it often now begins in a predictive model, which then determines what might be explored in the real world.

The transformation that is due to computation is often described as digital disruption . But an aspect of this transformation that can easily be overlooked is that computing has been disrupting itself.

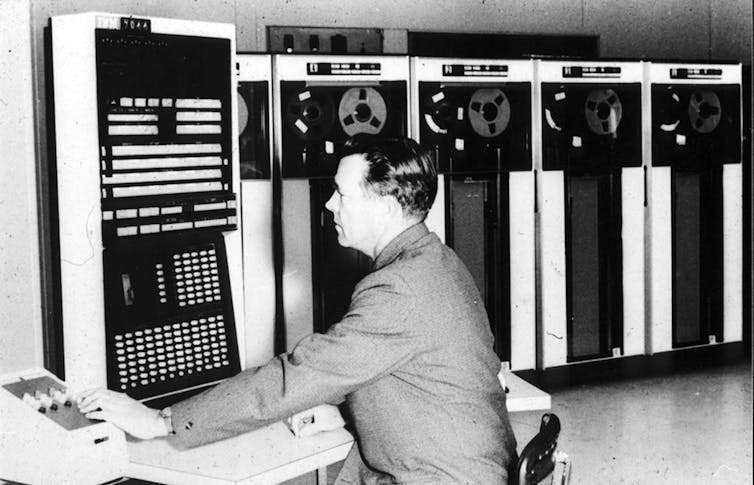

Evolution and revolution

Each wave of new computational technology has tended to lead to new kinds of systems, new ways of creating tools, new forms of data, and so on, which have often overturned their predecessors. What has seemed to be evolution is, in some ways, a series of revolutions.

But the development of computing technologies is more than a chain of innovation – a process that’s been a hallmark of the physical technologies that shape our world.

For example, there is a chain of inspiration from waterwheel, to steam engine, to internal combustion engine. Underlying this is a process of enablement. The industry of steam engine construction yielded the skills, materials and tools used in construction of the first internal combustion engines.

In computing, something richer is happening where new technologies emerge, not only by replacing predecessors, but also by enveloping them. Computing is creating platforms on which it reinvents itself, reaching up to the next platform.

Getting connected

Arguably, the most dramatic of these innovations is the web. During the 1970s and 1980s, there were independent advances in the availability of cheap, fast computing, of affordable disk storage and of networking.

Compute and storage were taken up in personal computers, which at that stage were standalone, used almost entirely for gaming and word processing. At the same time, networking technologies became pervasive in university computer science departments, where they enabled, for the first time, the collaborative development of software.

This was the emergence of a culture of open-source development, in which widely spread communities not only used common operating systems, programming languages and tools, but collaboratively contributed to them.

As networks spread, tools developed in one place could be rapidly promoted, shared and deployed elsewhere. This dramatically changed the notion of software ownership, of how software was designed and created, and of who controlled the environments we use.

The networks themselves became more uniform and interlinked, creating the global internet, a digital traffic infrastructure. Increases in computing power meant there was spare capacity for providing services remotely.

The falling cost of disk meant that system administrators could set aside storage to host repositories that could be accessed globally. The internet was thus used not just for email and chat forums (known then as news groups) but, increasingly, as an exchange mechanism for data and code.

This was in strong contrast to the systems used in business at that time, which were customised, isolated, and rigid.

With hindsight, the confluence of networking, compute and storage at the start of the 1990s, coupled with the open-source culture of sharing, seems almost miraculous. An environment ready for something remarkable, but without even a hint of what that thing might be.

The ‘superhighway’

It was to enhance this environment that then US Vice President Al Gore proposed in 1992 the “ information superhighway ”, before any major commercial or social uses of the internet had appeared.

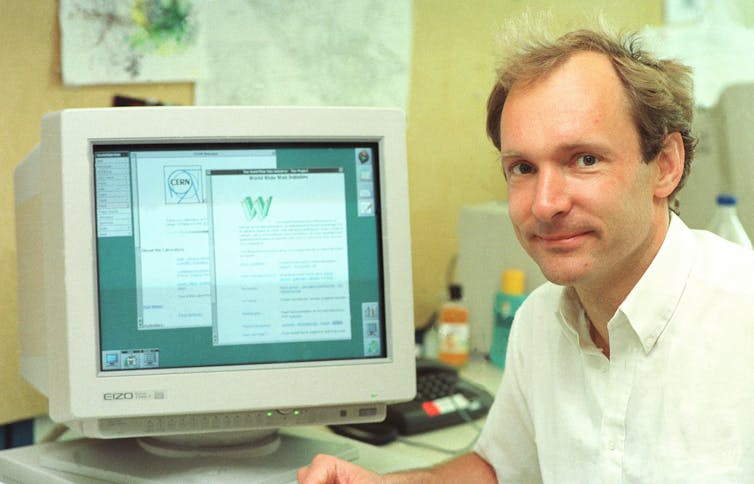

Meanwhile, in 1990, researchers at CERN, including Tim Berners-Lee , created a system for storing documents and publishing them to the internet, which they called the world wide web .

As knowledge of this system spread on the internet (transmitted by the new model of open-source software systems), people began using it via increasingly sophisticated browsers. They also began to write documents specifically for online publication – that is, web pages.

As web pages became interactive and resources moved online, the web became a platform that has transformed society. But it also transformed computing.

With the emergence of the web came the decline of the importance of the standalone computer, dependent on local storage.

We all connect

The value of these systems is due to another confluence: the arrival on the web of vast numbers of users. For example, without behaviours to learn from, search engines would not work well, so human actions have become part of the system.

There are (contentious) narratives of ever-improving technology, but also an entirely unarguable narrative of computing itself being transformed by becoming so deeply embedded in our daily lives.

This is, in many ways, the essence of big data. Computing is being fed by human data streams: traffic data, airline trips, banking transactions, social media and so on.

The challenges of the discipline have been dramatically changed by this data, and also by the fact that the products of the data (such as traffic control and targeted marketing) have immediate impacts on people.

Software that runs robustly on a single computer is very different from that with a high degree of rapid interaction with the human world, giving rise to needs for new kinds of technologies and experts, in ways not evenly remotely anticipated by the researchers who created the technologies that led to this transformation.

Decisions that were once made by hand-coded algorithms are now made entirely by learning from data. Whole fields of study may become obsolete.

The discipline does indeed disrupt itself. And as the next wave of technology arrives (immersive environments? digital implants? aware homes?), it will happen again.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Fourth Industrial Revolution .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How the Internet of Things (IoT) became a dark web target – and what to do about it

Antoinette Hodes

May 17, 2024

How can GenAI be optimized for people and processes?

May 15, 2024

Here’s how virtual reality can boost refugee crisis awareness and action

AI is changing the shape of leadership – how can business leaders prepare?

Ana Paula Assis

May 10, 2024

Earth observation will unlock huge economic and climate value for these 6 industries by 2030

Brett Loubert, Bridget Fawcett and Helen Burdett

May 7, 2024

UK proposal to ban smartphones for kids, and other technology stories you need to know

Visual Life

- Creative Projects

- Write Here!

Karunaratne, Indika & Atukorale, Ajantha & Perera, Hemamali. (2011). Surveillance of human- computer interactions: A way forward to detection of users' Psychological Distress. 2011 IEEE Colloquium on Humanities, Science and Engineering, CHUSER 2011. 10.1109/CHUSER.2011.6163779.

June 9, 2023 / 1 comment / Reading Time: ~ 12 minutes

The Digital Revolution: How Technology is Changing the Way We Communicate and Interact

This article examines the impact of technology on human interaction and explores the ever-evolving landscape of communication. With the rapid advancement of technology, the methods and modes of communication have undergone a significant transformation. This article investigates both the positive and negative implications of this digitalization. Technological innovations, such as smartphones, social media, and instant messaging apps, have provided unprecedented accessibility and convenience, allowing people to connect effortlessly across distances. However, concerns have arisen regarding the quality and authenticity of these interactions. The article explores the benefits of technology, including improved connectivity, enhanced information sharing, and expanded opportunities for collaboration. It also discusses potential negative effects including a decline in in-person interactions, a loss of empathy, and an increase in online anxiety. This article tries to expand our comprehension of the changing nature of communication in the digital age by exposing the many ways that technology has an impact on interpersonal interactions. It emphasizes the necessity of intentional and thoughtful communication techniques to preserve meaningful connections in a society that is becoming more and more reliant on technology.

Introduction:

Technology has significantly transformed our modes of communication and interaction, revolutionizing the way we connect with one another over the past few decades. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has acted as a catalyst, expediting this transformative process, and necessitating our exclusive reliance on digital tools for socializing, working, and learning. Platforms like social media and video conferencing have emerged in recent years, expanding our options for virtual communication. The impact of these changes on our lives cannot be ignored. In this article, we will delve into the ways in which technology has altered our communication and interaction patterns and explore the consequences of these changes for our relationships, mental well-being, and society.

To gain a deeper understanding of this topic, I have conducted interviews and surveys, allowing us to gather firsthand insights from individuals of various backgrounds. Additionally, we will compare this firsthand information with the perspectives shared by experts in the field. By drawing on both personal experiences and expert opinions, we seek to provide a comprehensive analysis of how technology influences our interpersonal connections. Through this research, we hope to get a deeper comprehension of the complex interactions between technology and people, enabling us to move mindfully and purposefully through the rapidly changing digital environment.

The Evolution of Communication: From Face-to-Face to Digital Connections:

In the realm of communication, we have various mediums at our disposal, such as face-to-face interactions, telephone conversations, and internet-based communication. According to Nancy Baym, an expert in the field of technology and human connections, face-to-face communication is often regarded as the most personal and intimate, while the phone provides a more personal touch than the internet. She explains this in her book Personal Connections in the Digital Age by stating, “Face-to-face is much more personal; phone is personal as well, but not as intimate as face-to-face… Internet would definitely be the least personal, followed by the phone (which at least has the vocal satisfaction) and the most personal would be face-to-face” (Baym 2015). These distinctions suggest that different communication mediums are perceived to have varying levels of effectiveness in conveying emotion and building relationships. This distinction raises thought-provoking questions about the impact of technology on our ability to forge meaningful connections. While the internet offers unparalleled convenience and connectivity, it is essential to recognize its limitations in reproducing the depth of personal interaction found in face-to-face encounters. These limitations may be attributed to the absence of nonverbal cues, such as facial expressions, body language, and tone of voice, which are vital elements in understanding and interpreting emotions accurately.

Traditionally, face-to-face interactions held a prominent role as the primary means of communication, facilitating personal and intimate connections. However, the rise of technology has brought about significant changes, making communication more convenient but potentially less personal. The rise of phones, instant messaging, and social media platforms has revolutionized how we connect with others. While these digital tools offer instant connectivity and enable us to bridge geographical distances, they introduce a layer of blockage that may impact the depth and quality of our interactions. It is worth noting that different communication mediums have their strengths and limitations. Phone conversations, for instance, retain a certain level of personal connection through vocal interactions, allowing for the conveyance of emotions and tones that text-based communication may lack. However, even with this advantage, phone conversations still fall short of the depth and richness found in face-to-face interactions, as they lack visual cues and physical presence.

Internet-based communication, on the other hand, is considered the least personal medium. Online interactions often rely on text-based exchanges, which may not fully capture the nuances of expression, tone, and body language. While the internet offers the ability to connect with a vast network of individuals and share information on a global scale, it may not facilitate the same depth and authenticity that in-person or phone conversations can provide. As a result, establishing meaningful connections and building genuine relationships in an online setting can be challenging. Research and observations support these ideas. Figure 1. titled “Social Interaction after Electronic Media Use,” shows the potential impact of electronic media on social interaction (source: ResearchGate). This research highlights the need to carefully consider the effects of technology on our interpersonal connections. While technology offers convenience and connectivity, it is essential to strike a balance, ensuring that we do not sacrifice the benefits of face-to-face interactions for the sake of digital convenience.

![write a term paper on how the computer as revolutionize the practice mass communication Social interaction vs. electronic media use: Hours per day of face-to-face social interaction declines as use of electronic media [6].](https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ajantha-Atukorale/publication/254056654/figure/fig1/AS:298056646971392@1448073650081/Social-interaction-vs-electronic-media-use-Hours-per-day-of-face-to-face-social.png)

Figure 1: Increased reliance on electronic media has led to a noticeable decrease in social interaction.

The Limitations and Effects of Digital Communication

In today’s digital age, the limitations and effects of digital communication are becoming increasingly evident. While the phone and internet offer undeniable benefits such as convenience and the ability to connect with people regardless of geographical distance, they fall short in capturing the depth and richness of a face-to-face conversation. The ability to be in the same physical space as the person we’re communicating with, observing their facial expressions, body language, and truly feeling their presence, is something unique and irreplaceable.

Ulrike Schultze, in her thought-provoking TED Talk titled “How Social Media Shapes Identity,” delves further into the impact of digital communication on our lives by stating, “we construct the technology, but the technology also constructs us. We become what technology allows us to become” (Schultze 2015). This concept highlights how our reliance on digital media for interaction has led to a transformation in how we express ourselves and relate to others.

The influence of social media has been profound in shaping our communication patterns and interpersonal dynamics. Research conducted by Kalpathy Subramanian (2017) examined the influence of social media on interpersonal communication, highlighting the changes it brings to the way we interact and express ourselves (Subramanian 2017). The study found that online communication often involves the use of abbreviations, emoticons, and hashtags, which have become embedded in our online discourse. These digital communication shortcuts prioritize speed and efficiency, but they also contribute to a shift away from the physical action of face-to-face conversation, where nonverbal cues and deeper emotional connections can be fostered.

Additionally, the study emphasizes the impact of social media on self-presentation and identity construction. With the rise of platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, individuals have a platform to curate and present themselves to the world. This online self-presentation can influence how we perceive ourselves and how others perceive us, potentially shaping our identities in the process. The study further suggests that the emphasis on self-presentation and the pressure to maintain a certain image on social media can lead to increased stress and anxiety among users.

Interviews:

I conducted interviews with individuals from different age groups to gain diverse perspectives on how technology and social media have transformed the way we connect with others. By exploring the experiences of a 21-year-old student and an individual in their 40s, we can better understand the evolving dynamics of interpersonal communication in the digital age. These interviews shed light on the prevalence of digital communication among younger generations, their preference for convenience, and the concerns raised by individuals from older age groups regarding the potential loss of deeper emotional connections.

When I asked the 21-year-old classmate about how technology has changed the way they interact with people in person, they expressed, “To be honest, I spend more time texting, messaging, or posting on social media than actually talking face-to-face with others. It’s just so much more convenient.” This response highlights the prevalence of digital communication among younger generations and their preference for convenience over traditional face-to-face interactions. It suggests that technology has significantly transformed the way young people engage with others, with a greater reliance on virtual interactions rather than in-person conversations. Additionally, the mention of convenience as a driving factor raises questions about the potential trade-offs in terms of depth and quality of interpersonal connections.

To gain insight from an individual in their 40s, I conducted another interview. When asked about their experiences with technology and social media, they shared valuable perspectives. They mentioned that while they appreciate the convenience and accessibility offered by technology, they also expressed concerns about its impact on interpersonal connections. They emphasized the importance of face-to-face interactions in building genuine relationships and expressed reservations about the potential loss of deeper emotional connections in digital communication. Additionally, they discussed the challenges of adapting to rapid technological advancements and the potential generational divide in communication preferences.

Comparing the responses from both interviews, it is evident that there are generational differences in the perception and use of technology for communication. While the 21-year-old classmate emphasized convenience as a primary factor in favor of digital communication, the individual in their 40s highlighted the importance of face-to-face interactions and expressed concerns about the potential loss of meaningful connections in the digital realm. This comparison raises questions about the potential impact of technology on the depth and quality of interpersonal relationships across different age groups. It also invites further exploration into how societal norms and technological advancements shape individuals’ preferences and experiences.

Overall, the interviews revealed a shift towards digital communication among both younger and older individuals, with varying perspectives. While convenience and connectivity are valued, concerns were raised regarding the potential drawbacks, including the pressure to maintain an idealized online presence and the potential loss of genuine connections. It is evident that technology and social media have transformed the way we communicate and interact with others, but the interviews also highlighted the importance of maintaining a balance and recognizing the value of face-to-face interactions in fostering meaningful relationships.

I have recently conducted a survey with my classmates to gather insights on how technology and social media have influenced communication and interaction among students in their daily lives. Although the number of responses is relatively small, the collected data allows us to gain a glimpse into individual experiences and perspectives on this matter.

One of the questions asked in the survey was how often students rely on digital communication methods, such as texting, messaging, or social media, in comparison to engaging in face-to-face conversations. The responses indicated a clear trend towards increased reliance on digital communication, with 85% of participants stating that they frequently use digital platforms as their primary means of communication. This suggests a significant shift away from traditional face-to-face interactions, highlighting the pervasive influence of technology in shaping our communication habits.

Furthermore, the survey explored changes in the quality of interactions and relationships due to the increased use of technology and social media. Interestingly, 63% of respondents reported that they had noticed a decrease in the depth and intimacy of their connections since incorporating more digital communication into their lives. Many participants expressed concerns about the difficulty of conveying emotions effectively through digital channels and the lack of non-verbal cues that are present in face-to-face interactions. It is important to note that while the survey results provide valuable insights into individual experiences, they are not representative of the entire student population. The small sample size limits the generalizability of the findings. However, the data collected does shed light on the potential impact of technology and social media on communication and interaction patterns among students.

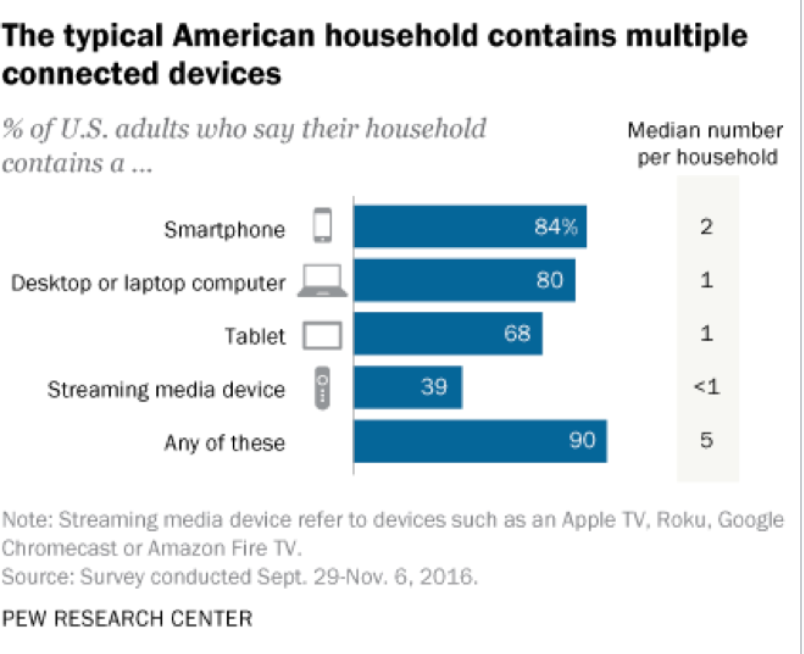

Expanding on the topic, I found an insightful figure from Business Insider that sheds light on how people utilize their smartphones (Business Insider). Figure 2. illustrates the average smartphone owner’s daily time spent on various activities. Notably, communication activities such as texting, talking, and social networking account for a significant portion, comprising 59% of phone usage. This data reinforces the impact of digital communication on our daily lives, indicating the substantial role it plays in shaping our interactions with others. Upon comparing this research with the data, I have gathered, a clear trend emerges, highlighting that an increasing number of individuals primarily utilize their smartphones for communication and interaction purposes.

Figure 2: The breakdown of daily smartphone usage among average users clearly demonstrates that the phone is primarily used for interactions.

The Digital Make Over:

In today’s digital age, the impact of technology on communication and interaction is evident, particularly in educational settings. As a college student, I have witnessed the transformation firsthand, especially with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The convenience of online submissions for assignments has led to a growing trend of students opting to skip physical classes, relying on the ability to submit their work remotely. Unfortunately, this shift has resulted in a decline in face-to-face interactions and communication among classmates and instructors.

The decrease in physical attendance raises concerns about the potential consequences for both learning and social connections within the academic community. Classroom discussions, collaborative projects, and networking opportunities are often fostered through in-person interactions. By limiting these experiences, students may miss out on valuable learning moments, diverse perspectives, and the chance to establish meaningful connections with their peers and instructors.

Simon Lindgren, in his thought-provoking Ted Talk , “Media Are Not Social, but People Are,” delves deeper into the effects of technology and social media on our interactions. Lindgren highlights a significant point by suggesting that while technology may have the potential to make us better individuals, we must also recognize its potential pitfalls. Social media, for instance, can create filter bubbles that limit our exposure to diverse viewpoints, making us less in touch with reality and more narrow-minded. This cautionary reminder emphasizes the need to approach social media thoughtfully, seeking out diverse perspectives and avoiding the pitfalls of echo chambers. Furthermore, it is crucial to strike a balance between utilizing technology for educational purposes and embracing the benefits of in-person interactions. While technology undoubtedly facilitates certain aspects of education, such as online learning platforms and digital resources, we must not overlook the importance of face-to-face communication. In-person interactions allow for nuanced non-verbal cues, deeper emotional connections, and real-time engagement that contribute to a more comprehensive learning experience.

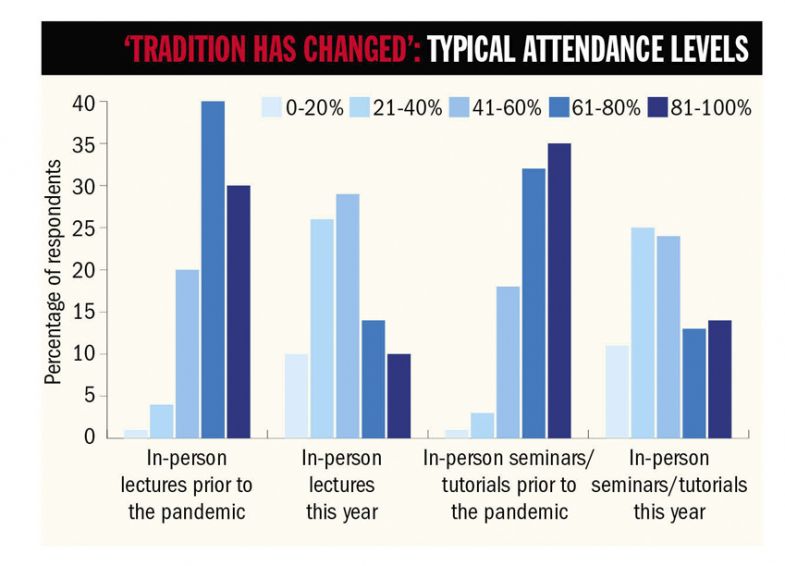

A study conducted by Times Higher Education delved into this topic, providing valuable insights. Figure 3. from the study illustrates a significant drop in attendance levels after the pandemic’s onset. Undeniably, technology played a crucial role in facilitating the transition to online learning. However, it is important to acknowledge that this shift has also led to a decline in face-to-face interactions, which have long been regarded as essential for effective communication and relationship-building. While technology continues to evolve and reshape the educational landscape, it is imperative that we remain mindful of its impact on communication and interaction. Striking a balance between digital tools and in-person engagement can help ensure that we leverage the benefits of technology while preserving the richness of face-to-face interactions. By doing so, we can foster a holistic educational experience that encompasses the best of both worlds and cultivates meaningful connections among students, instructors, and the academic community.

Figure 3: This graph offers convincing proof that the COVID-19 pandemic and the extensive use of online submission techniques are to blame for the sharp reduction in in-person student attendance.

When asked about the impact of online submissions for assignments on physical attendance in classes, the survey revealed mixed responses. While 73% of participants admitted that the convenience of online submissions has led them to skip classes occasionally, 27% emphasized the importance of in-person attendance for better learning outcomes and social interactions. This finding suggests that while technology offers convenience, it also poses challenges in maintaining regular face-to-face interactions, potentially hindering educational and social development, and especially damaging the way we communicate and interact with one another. Students are doing this from a young age, and it comes into huge effect once they are trying to enter the work force and interact with others. When examining the survey data alongside the findings from Times Higher Education, striking similarities become apparent regarding how students approach attending classes in person with the overall conclusion being a massive decrease in students attending class which hinders the chance for real life interaction and communication. the convenience and instant gratification provided by technology can create a sense of detachment and impatience in interpersonal interactions. Online platforms allow for quick and immediate responses, and individuals can easily disconnect or switch between conversations. This can result in a lack of attentiveness and reduced focus on the person with whom one is communicating, leading to a superficial engagement that may hinder the establishment of genuine connections.

Conclusion:

Ultimately, the digital revolution has profoundly transformed the way we communicate and interact with one another. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated this transformation, leading to increased reliance on digital tools for socializing, working, and learning. While technology offers convenience and connectivity, it also introduces limitations and potential drawbacks. The shift towards digital communication raises concerns about the depth and quality of our connections, as well as the potential loss of face-to-face interactions. However, it is essential to strike a balance between digital and in-person engagement, recognizing the unique value of physical presence, non-verbal cues, and deeper emotional connections that face-to-face interactions provide. By navigating the digital landscape with mindfulness and intentionality, we can harness the transformative power of technology while preserving and nurturing the essential elements of human connection.

Moving forward, it is crucial to consider the impact of technology on our relationships, mental well-being, and society. As technology continues to evolve, we must be cautious of its potential pitfalls, such as the emphasis on self-presentation, the potential for increased stress and anxiety, and the risk of forgetting how to interact in person. Striking a balance between digital and face-to-face interactions can help ensure that technology enhances, rather than replaces, genuine human connections. By prioritizing meaningful engagement, valuing personal interactions, and leveraging the benefits of technology without compromising the depth and quality of our relationships, we can navigate the digital revolution in a way that enriches our lives and fosters authentic connections.

References:

Ballve, M. (2013, June 5). How much time do we really spend on our smartphones every day? Business Insider. Retrieved April 27, 2023. https://www.businessinsider.com/how-much-time-do-we-spend-on-smartphones-2013-6

Baym, N. (2015). Personal Connections in the Digital Age (2nd ed.). Polity.

Karunaratne, Indika & Atukorale, Ajantha & Perera, Hemamali. (2011). Surveillance of human- computer interactions: A way forward to detection of users’ Psychological Distress. 2011 IEEE Colloquium on Humanities, Science and Engineering, CHUSER 2011. 10.1109/CHUSER.2011.6163779. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Social-interaction-vs-electronic-media-use-Hours-per-day-of-face-to-face-social_fig1_254056654

Lindgren, S. (2015, May 20). Media are not social, but people are | Simon Lindgren | TEDxUmeå . YouTube. Retrieved April 27, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nQ5S7VIWE6k

Ross, J., McKie, A., Havergal, C., Lem, P., & Basken, P. (2022, October 24). Class attendance plummets post-Covid . Times Higher Education (THE). Retrieved April 27, 2023, from https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/class-attendance-plummets-post-covid

Schultze, U. (2015, April 23). How social media shapes identity | Ulrike Schultze | TEDxSMU . YouTube. Retrieved April 27, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CSpyZor-Byk

Subramanian, Dr. K .R. “Influence of Social Media in Interpersonal Communication – Researchgate.” ResearchGate.Net , www.researchgate.net/profile/Kalpathy-Subramanian/publication/319422885_Influence_of_Social_Media_in_Interpersonal_Communication/links/59a96d950f7e9b2790120fea/Influence-of-Social-Media-in-Interpersonal-Communication.pdf. Accessed 12 May 2023 .

And So It Was Written

Author: Anonymous

Published: June 9, 2023

Word Count: 3308

Reading time: ~ 12 minutes

Edit Link: (emailed to author) Request Now

ORGANIZED BY

Articles , Published

MORE TO READ

Add yours →.

- What Does Ois Stands For - Quant RL

Provide Feedback Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

A TRU Writer powered SPLOT : Visual Life

Blame @cogdog — Up ↑

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

10.1.3: Evolution of Mass Communication

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 109755

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Societies have long had a desire to find effective ways to report environmental dangers and opportunities; circulate opinions, facts, and ideas; pass along knowledge, heritage, and lore; communicate expectations to new members; entertain in an expansive manner; and broaden commerce and trade (Schramm). The primary challenge has been to find ways to communicate messages to as many people as possible. Our need-to-know prompted innovative ways to get messages to the masses.

Before writing, humans relied on oral traditions to pass on information. “It was only in the 1920s-according to the Oxford English Dictionary-that people began to speak of 'the media’ and a generation later, in the 1950s, of a ‘communication revolution’, but a concern with the means of communication is very much older than that” (Briggs & Burke 1). Oral and written communication played a major role in ancient cultures. These oral cultures used stories to document the past and impart cultural standards, traditions, and knowledge. With the development of alphabets around the world over 5000 years ago, written language with ideogrammatic (picture-based) alphabets like hieroglyphics started to change how cultures communicated.

Still, written communication remained ambiguous and did not reach the masses until the Greeks and Romans resolved this by establishing a syllabic alphabet representing sounds. But, without something to write on, written language was inefficient. Eventually, paper making processes were perfected in China, which spread throughout Europe via trade routes (Baran). Mass communication was not quick, but it was far-reaching (Briggs & Burke). This forever altered how cultures saved and transmitted cultural knowledge and values. Any political or social movement throughout the ages can be traced to the development and impact of the printing press and movable metal type (Steinberg). With his technique, Guttenberg could print more than a single page of specific text. By making written communication more available to larger numbers of people, mass printing became responsible for giving voice to the masses and making information available to common folks (McLuhan & Fiore). McLuhan argued that Gutenberg’s evolution of the printing press as a form of mass communication had profound and lasting effects on culture, perhaps the most significant invention in human history.

Mass Communication Study Then

In 1949, Carl I. Hovland, Arthur A. Lumsdaine, and Fred D. Sheffield wrote the book Experiments on Mass Communication. They looked at two kinds of films the Army used to train soldiers. First, they examined orientation and training films such as the “Why We Fight” that were intended to teach facts to the soldiers, as well as generate a positive response from them for going to war. The studies determined that significant learning did take place by the soldiers from the films, but primarily with factual items. The Army was disappointed with the results that showed that the orientation films did not do an effective job in generating the kind of positive responses they desired from the soldiers. Imagine, people were not excited about going to war.

With the transition to the industrial age in the 18th century, large populations headed to urban areas, creating mass audiences of all economic classes seeking information and entertainment. Printing technology was at the heart of modernization WHICH led to magazines, newspapers, the telegraph, and the telephone. At the turn of the century (1900), pioneers like Thomas Edison, Theodore Puskas, and Nikola Tesla literally electrified the world and mass communication. With the addition of motion pictures and radio in the early 1900s, and television in the 40s and 50s, the world increasingly embraced the foundations of today’s mass communication. In the 1970s cable started challenging over-the-air broadcasting and traditional program distribution making the United States a wired nation. In 2014, there was an estimated 116.3 million homes in America that own a TV (Nielson, 2014 Advance National TV Household Universe Estimate). While traditionally these televisions would display only the programs that are chosen to be broadcast by cable providers, more and more households have chosen to become more conscious media consumers and actively choose what they watch through alternative viewing options like streaming video.

Today, smart T.V.'s and streaming devices have taken over the market. Many American households have multiple devices – especially smartphones. A third of American households have three or more smartphones, compared with 23% that have three or more desktops, 17% that have three or more tablets and only 7% that have three or more streaming media devices. These new forms of broadcasting have created a digital revolution. Thanks to Netflix and other streaming services we are no longer subjected to advertisements during our shows. Similarly, streaming services like Hulu provide the most recent episodes as they appear on cable that viewers can watch any time. These services provide instant access to entire seasons of shows (which can result in binge watching).

The Information Age eventually began to replace the ideals of the industrial age. In 1983 Time Magazine named the PC the first "Machine of the Year." Just over a decade later, PCs outsold televisions. Then, in 2006, Time Magazine named “you” as the person of the year for your use of technology to broaden communication. "You" took advantage of changes in global media. Chances are that you, your friends, and family spend hours engaged in data-mediated communication such as emailing, texting, or participating in various form of social media. Romero points out that, “The Net has transformed the way we work, the way we get in contact with others, our access to information, our levels of privacy and indeed notions as basic and deeply rooted in our culture as those of time and space” (88). Social media has also had a large impact in social movements across the globe in recent years by providing the average person with the tools to reach wide audiences around the world for the first time in history.

If you're reading this for a college class, you may belong to the millennial or Z generation. Free wifi, apps, alternative news sources, Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube and Twitter have become a way of life. Can you imagine a world without communication technology? How would you find out the name of that song stuck in your head? If you wanted to spontaneously meet up with a friend for lunch, how would you let them know? Mass communication has become such an integral part of our daily lives, most people probably could not function through the day without it. What started as email quickly progressed to chat rooms and basic blogs, such as LiveJournal. From there, we saw the rise and fall of the first widely used social media platform, Myspace. Though now just a shadow of the social media powerhouse it once was, Myspace paved the way for social media to enter the mainstream in forms of websites such as Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Snapchat, and Instagram. Facebook has evolved into a global social media site. It’s available in 37 languages and has over 2.07 billion users--That's 1/4 of the world's population. Mark Zuckerberg created Facebook in 2005 while studying at Harvard University, and it has universally changed the way we communicate, interact, and share our lives with friends, family, and acquaintances. Many people argue about the good and bad qualities of having a Facebook profile, it can be looked at as your “digital footprint” in social media. While Facebook is a platform to connect socially, it has also received tremendous criticism for its use as a platform for influencing geopolitics, including the 2016 US President election. Here's a short YouTube video from rapper/poet Prince Ea about Facebook and the effects of social media on society.

Another example of mainstream social media is Twitter. Twitter allows for quick 280 character or less status updates (called tweets) for registered users. Tweets can be sent from any device with access to internet in a fast, simple way that connects with a number of people, whether they be family, friends or followers. Twitter's microblogging format allows for people to share their daily thoughts and experiences on a broad and sometimes public stage. The simplicity of Twitter allows it to be used as a tool for entertainment and blogging, but also as a way of organizing social movements and sharing breaking news. President Donald Trump is fond of using Twitter as a means of communicating, a first in Presidential politics.

Mass Communication Study Now

With new forms of communication emerging rapidly, it is important to note the corresponding changes to formal language and slang terms. UrbanDictionary.com is a famous site that can introduce any newbie to the slang world by presenting them various definitions for a term they don’t recognize, describe its background, and provide examples for how it’s used in context. For example, one of the most popular definitions claims that the word ‘ hella ’ is said to originate from the streets of San Francisco in the Hunters Point neighborhood. “It is commonly used in place of ‘really’ or ‘very’ when describing something.”

Snapchat is a newer social media platform used by more and more people every day. The function of Snapchat allows the user to send a photo (with the option of text) that expires after a few seconds. It can be looked at like a digital self-destructing note you would see in an old spy movie. Unlike its competitors, Snapchat is used in a less professional manner, emphasizing humor and spontaneity over information efficiency. Contrary to Facebook, there is no pressure to pose, or display your life. Rather, it is more spontaneous. It’s like the stranger you wink at in the street or a hilarious conversation with a best friend.

In this age of information overload, multiple news sources, high-speed connections, and social networking, life seems unimaginable without mass communication. Can you relate to your parents’ stories about writing letters to friends, family, or their significant others? Today, when trying to connect with someone we have a variety ways of contacting them; we can call, text, email, Facebook message, tweet, and/or Snapchat; the options are almost endless and ever-changing. Society today is in the midst of a technological revolution. Only a few years ago families were arguing over landline internet cable use and the constant disruptions from incoming phone calls. Now, we have the ability to browse the web anytime on smart phones. Since the printing press, mass communication has literally changed the ways we think and interact as humans. We take so much for granted as “new technologies are assimilated so rapidly in U.S. culture that historic perspectives are often lost in the process” (Fidler 1). With all of this talk and research about mass communication, what functions does it serve for us?

Mass Communication Now

The expansion of mass media brings new challenges and opportunities to ensure inclusion, so that all have access to the information available through these mediums. Making information accessible to all is important and necessary. Websites have begun using disability accessible features to allow as many people as possible access to online communication. Check out this article on how to make sure your website is disability friendly.

- Search Menu

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Submit?

- About Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication

- About International Communication Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Constraints on internet research, rethinking definitions, viewing the internet as mass medium, applying theories to cmc, critical mass, interactivity, uses and gratifications, social presence and media richness theory, network approaches.

- < Previous

The Internet as Mass Medium

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Merrill Morris, Christine Ogan, The Internet as Mass Medium, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , Volume 1, Issue 4, 1 March 1996, JCMC141, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.1996.tb00174.x

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The Internet has become impossible to ignore in the past two years. Even people who do not own a computer and have no opportunity to “surf the net” could not have missed the news stories about the Internet, many of which speculate about its effects on the ever-increasing number of people who are on line. Why, then, have communications researchers, historically concerned with exploring the effects of mass media, nearly ignored the Internet? With 25 million people estimated to be communicating on the Internet, should communication researchers now consider this network of networks [1] a mass medium? Until recently, mass communications researchers have overlooked not only the Internet but the entire field of computer-mediated communication, staying instead with the traditional forms of broadcast and print media that fit much more conveniently into models for appropriate research topics and theories of mass communication.

However, this paper argues that if mass communications researchers continue to largely disregard the research potential of the Internet, their theories about communication will become less useful. Not only will the discipline be left behind, it will also miss an opportunity to explore and rethink answers to some of the central questions of mass communications research, questions that go to the heart of the model of source-message-receiver with which the field has struggled. This paper proposes a conceptualization of the Internet as a mass medium, based on revised ideas of what constitutes a mass audience and a mediating technology. The computer as a new communication technology opens a space for scholars to rethink assumptions and categories, and perhaps even to find new insights into traditional communication technologies.

This paper looks at the Internet, rather than computer-mediated communication as a whole, in order to place the new medium within the context of other mass media. Mass media researchers have traditionally organized themselves around a specific communications medium. The newspaper, for instance, is a more precisely defined area of interest than printing-press-mediated communication, which embraces more specialized areas, such as company brochures or wedding invitations. Of course, there is far more than a semantic difference between conceptualizing a new communication technology by its communicative form than by the technology itself. The tradition of mass communication research has accepted newspapers, radio, and television as its objects of study for social, political, and economic reasons. As technology changes and media converge, those research categories must become flexible.

Mass communications researchers have overlooked the potential of the Internet for several reasons. The Internet was developed in bits and pieces by hobbyists, students, and academics ( Rheingold, 1994 ). It didn't fit researchers' ideas about mass media, locked, as they have been, into models of print and broadcast media. Computer-mediated communication (CMC) at first resembled interpersonal communication and was relegated to the domain of other fields, such as education, management information science, and library science. These fields, in fact, have been doing research into CMC for nearly 20 years ( Dennis & Gallupe, 1993 ; O'Shea & Self, 1983 ), and many of their ideas about CMC have proven useful in looking at the phenomenon as a mass medium. Both education and business researchers have seen the computer as a technology through which communication was mediated, and both lines of research have been concerned with the effects of this new medium.

Disciplinary lines have long kept researchers from seeing the whole picture of the communication process. Cathcart and Gumpert (1983) recognized this problem when they noted how speech communication definitions “have minimized the role of media and channel in the communication process” (p. 267), even as mass communication definitions disregarded the ways media function in interpersonal communication: “We are quite convinced that the traditional division of communication study into interpersonal, group and public, and mass communication is inadequate because it ignores the pervasiveness of media” (p. 268).

The major constraint on doing mass communication research into the Internet, however, has been theoretical. In searching for theories to apply to group software systems, researchers in MIS have recognized that communication studies needed new theoretical models: “The emergence of new technologies such as GSS (Group Support Systems, software that allows group decision-making), which combine aspects of both interpersonal interaction and mass media, presents something of a challenge to communication theory. With new technologies, the line between the various contexts begins to blur, and it is unclear that models based on mass media or face-to-face contexts are adequate” ( Poole & Jackson, 1993 , p. 282).

Not only have theoretical models constrained research, but the most basic assumptions behind researchers' theories of mass media effects have kept them from being able to see the Internet as a new mass medium. DeFleur and Ball-Rokeach's attitude toward computers in the fifth edition of their Theories of Mass Communication (1989) is typical. They compare computers to telephones, dismissing the idea of computer communication as mass communication: “Even if computer literacy were to become universal, and even if every household had a personal computer equipped with a modem, it is difficult to see how a new system of mass communication could develop from this base alone” (pp. 335-336). The fact that DeFleur and Ball-Rokeach find it difficult to envision this development may well be a result of their own constrained perspective. Taking the telephone analogy a step further, Lana Rakow (1992) points out that the lack of research on the telephone was due in part to researchers' inability to see it as a mass medium. The telephone also became linked to women, who embraced the medium as a way to overcome social isolation. [2]

However, a new communication technology can throw the facades of the old into sharp relief. Marshall McLuhan (1960) recognized this when, speaking of the computer, he wrote, “The advent of a new medium often reveals the lineaments and assumptions, as it were, of an old medium” (p. 567). In effect, a new communication technology may perform an almost postmodern function of making the unpresentable perceptible, as Lyotard (1983) might put it. In creating new configurations of sources, messages, and receivers, new communication technologies force researchers to examine their old definitions. What is a mass audience? What is a communication medium? How are messages mediated?

Daniel Bell (1960) recognized the slippery nature of the term mass society and how its many definitions lacked a sense of reality: “What strikes one about these varied uses of the concept of mass society is how little they reflect or relate to the complex, richly striated social relations of the real world” (p. 25). Similarly, the term mass media, with its roots in ideas of mass society, has always been difficult to define. There is much at stake in hanging on to traditional definitions of mass media, as shown in the considerable anxiety in recent years over the loss of the mass audience and its implications for the liberal pluralist state. The convergence of communication technologies, as represented by the computer, has set off this fear of demassification, as audiences become more and more fragmented. The political and social implications of mass audiences and mass media go beyond the scope of this paper, but the current uneasiness and discussion over the terms themselves seem to indicate that the old idea of the mass media has reached its limit ( Schudson, 1992 ; Warner, 1992 ).

Critical researchers have long questioned the assumptions implicit in traditional media effects definitions, looking instead to the social, economic, and historical contexts that gave rise to institutional conceptions of media. Such analysis, Fejes (1984) notes, can lead to another unquestioning set of assumptions about the media's ability to affect audiences. As Ang (1991) has pointed out, abandoning the idea of the mass media and their audiences impedes an investigation of media institutions' power to create messages that are consumed by real people. If the category of mass medium becomes too fuzzy to define, traditional effects researchers will be left without dependent variables, and critical scholars will have no means of discussing issues of social and political power.

A new communication technology such as the Internet allows scholars to rethink, rather than abandon, definitions and categories. When the Internet is conceptualized as a mass medium, what becomes clear is that neither mass nor medium can be precisely defined for all situations, but instead must be continually rearticulated depending on the situation. The Internet is a multifaceted mass medium, that is, it contains many different configurations of communication. Its varied forms show the connection between interpersonal and mass communication that has been an object of study since the two-step flow associated the two ( Lazarsfeld, Berelson, & Gaudet, 1944 ). Chaffee and Mutz (1988) have called for an exploration of this relationship that begins “with a theory that spells out what effects are of interest, and what aspects of communication might produce them” (p. 39). The Internet offers a chance to develop and to refine that theory.

How does it do this? Through its very nature. The Internet plays with the source-message-receiver features of the traditional mass communication model, sometimes putting them into traditional patterns, sometimes putting them into entirely new configurations. Internet communication takes many forms, from World Wide Web pages operated by major news organizations to Usenet groups discussing folk music to E-mail messages among colleagues and friends. The Internet's communication forms can be understood as a continuum. Each point in the traditional model of the communication process can, in fact, vary from one to a few to many on the Internet. Sources of the messages can range from one person in E-mail communication, to a social group in a Listserv or Usenet group, to a group of professional journalists in a World Wide Web page. The messages themselves can be traditional journalistic news stories created by a reporter and editor, stories created over a long period of time by many people, or simply conversations, such as in an Internet Relay Chat group. The receivers, or audiences, of these messages can also number from one to potentially millions, and may or may not move fluidly from their role as audience members to producers of messages.

Producers and audiences on the Internet can be grouped generally into four categories: (a) one-to-one asynchronous communication, such as E-mail; (b) many-to-many asynchronous communication, such as Usenet, electronic bulletin boards, and Listservers that require the receiver to sign up for a service or log on to a program to access messages around a particular topic or topics; (c) synchronous communication that can be one-to-one, one-to-few, or one-to-many and can be organized around a topic, the construction of an object, or role playing, such as MUDs (Multi-User Dungeons and their various transformations as MOOs, MUCKs and MUSHs), Internet Relay Chat and chat rooms on commercial services; and (d) asynchronous communication generally characterized by the receiver's need to seek out the site in order to access information, which may involve many-to-one, one-to-one, or one-to-many source-receiver relationships (e.g., Web sites, gophers, and FTP sites).

Reconceptualizing the audience for the communication that takes place on the Internet is a major problem, one that becomes increasingly important as commercial information providers enter the Internet in greater numbers. To date, thousands of commercial sources have created home pages or gopher sites for people to access their services or information about those services. As of September 1995, search tools on the Internet turned up as many as 123 different U.S. newspaper services and more than 1,300 magazine services with distinct web sites. Some newspapers seem to be creating home pages to mark their place in cyberspace until their managers determine how to make them commercially viable. Others may be moving to the Internet out of fear of the electronic competition. Thus, it remains difficult to envision the future of traditional mass media on the Internet-who will be the audience, how will that audience access the information and entertainment services, and what profit might be made from the services?

A parallel question investigates the impact of Internet communication on the audience. Mass communications researchers will want to examine information-seeking and knowledge gaps as well as a range of uses-and-gratifications-based questions concerning the audience. Since the Internet is also being used for entertainment as well as information, effects researchers will want to know whether the Internet is a functional equivalent of other entertainment media and whether there are negative effects in the distribution of pornography and verbal attacks (e.g., flaming and virtual rapes) on members of the audience. There are also questions of audience addiction to certain types of Internet communication and entertainment.

When the uses of the Internet as a mass medium are explored, questions arise about the nature of its communicative content. As commercial providers increase on the Internet, and more political information is provided, the problem of who sets the agenda for the new medium also becomes a concern.

Credibility is another issue with mass media. Traditional mass media make certain claims about the veracity of their information. The Internet makes few such claims at the moment, and it is possible that the concept of credibility will also change as a result. Recently, on a feminist newsnet group, an individual began to post what appeared to be off-base comments to a serious discussion of feminist issues. Several days later it was determined that “Mike” was a computer-generated personage and not a real contributor to the discussion at all. At present there is no way to know when the Mikes on the Internet are even real, let alone credible ( Ogan, 1993 ). Consequently, we wish to underscore the fundamental importance of this issue.

Traditional mass media have addressed the issue within their organizations, hiring editors and fact checkers to determine what information is accurate. Source credibility will vary on the Internet, with commercial media sites carrying relatively more credibility and unknown sources carrying less. A much greater burden will be placed on the user to determine how much faith to place in any given source.

Another question relates to the interchangeability of producers and receivers of content. One of the Internet's most widely touted advantages is that an audience member may also be a message producer. To what extent is that really the case? We may discover a fair amount about the producers of messages from the content of their electronic messages, but what about the lurkers? Who are they and how big is this group? To what extent do lurkers resemble the more passive audience of television sitcoms? And why do they remain lurkers and not also become information providers? Is there something about the nature of the medium that prevents their participation?

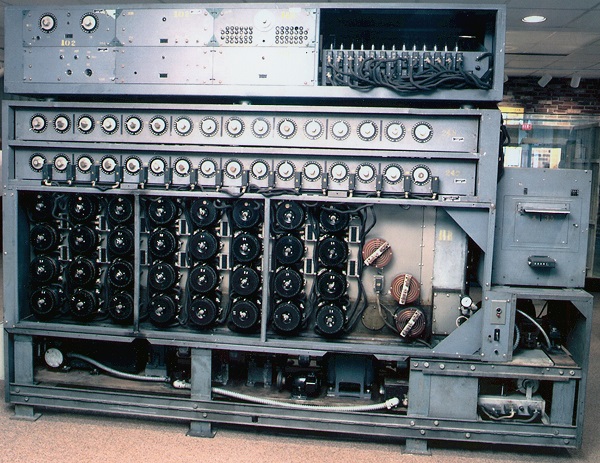

Other questions concern production of culture, social control, and political communication. Will the Internet ultimately be accessible to all? How are groups excluded from participation? Computers were originally created to wage war and have been developed in an extremely specific, exclusive culture. Can we trace those cultural influences in the way messages are produced on the Internet?

In an overview of research on computers in education, O'Shea and Self (1983) note that the learner-as-bucket theory had dominated. In this view, knowledge is like a liquid that is poured into the student, a metaphor similar to mass communication's magic-bullet theory. This brings up another aspect to consider in looking at mass communication research into CMC-the applicability of established theories and methodologies to the new medium. As new communication technologies are developed, researchers seem to use the patterns of research established for existing technologies to explain the uses and effects of the new media. Research in group communication, for example, has been used to examine the group uses of E-mail networks ( Sproull & Kiesler, 1991 ). Researchers have studied concepts of status, decision-making quality, social presence, social control, and group norms as they have been affected by a technology that permitted certain changes in group communication.

This kind of transfer of research patterns from one communication technology to another is not unusual. Wartella and Reeves (1985) studied the history of American mass communication research in the area of children and the media. With each new medium, the effects of content on children were discussed as a social problem in public debate. As Wartella and Reeves note, researchers responded to the public controversy over the adoption of a new media technology in American life.

In approaching the study of the Internet as a mass medium, the following established concepts seem to be useful starting points. Some of these have originated in the study of interpersonal or small group communication; others have been used to examine mass media. Some relate to the nature of the medium, while others focus on the audience for the medium.

This conceptual framework has been adopted from economists, physicists, and sociologists by organizational communication and diffusion of innovation scholars to better understand the size of the audience needed for a new technology to be considered successful and the nature of collective action as applied to electronic media use ( Markus, 1991 ; Oliver et al., 1985 ). For any medium to be considered a mass medium, and therefore economically viable to advertisers, a critical mass of adopters must be achieved. Interactive media only become useful as more and more people adopt, or as Rogers (1986) states, “the usefulness of a new communication system increases for all adopters with each additional adopter” (p. 120). Initially, the critical mass notion works against adoption, since it takes a number of other users to be seen as advantageous to adopt. For example, the telephone or an E-mail system was not particularly useful to the first adopters because most people were unable to receive their messages or converse with them. Valente (1995) notes that the critical mass is achieved when about 10 to 20 percent of the population has adopted the innovation. When this level has been reached, the innovation can be spread to the rest of the social system. Adoption of computers in U.S. households has well surpassed this figure, but the modem connections needed for Internet connection lag somewhat behind.

Because a collection of communication services-electronic bulletin boards, Usenet groups, E-mail, Internet Relay Chats, home pages, gophers, and so forth-comprise the Internet, the concept of critical mass on the Internet could be looked upon as a variable, rather than a fixed percentage of adopters. Fewer people are required for sustaining an Internet Relay Chat conference or a Multi-User Dungeon than may be required for an electronic bulletin board or another type of discussion group. As already pointed out, a relatively large number of E-mail users are required for any two people to engage in conversation, yet only those two people constitute the critical mass for any given conversation. For a bulletin board to be viable, its content must have depth and variety. If the audience who also serve as the source of information for the BBS is too small, the bulletin board cannot survive for lack of content. A much larger critical mass will be needed for such a group to maintain itself-perhaps as many as 100 or more. The discretionary data base, as defined by Connolly and Thorn (1991) is a “shared pool of data to which several participants may, if they choose, separately contribute information” (p. 221). If no one contributes, the data base cannot exist. It requires a critical mass of participants to carry the free riders in the system, thus supplying this public good to all members, participants, or free riders. Though applied to organizations, this refinement of the critical mass theory is a useful way of thinking about Listservs, electronic bulletin boards, Usenet groups, and other Internet services, where participants must hold up their end of the process through written contributions.

Each of these specific Internet services can be viewed as we do specific television stations, small town newspapers, or special interest magazines. None of these may reach a strictly mass audience, but in conjunction with all the other stations, newspapers, and magazines distributed in the country, they constitute mass media categories. So the Internet itself would be considered the mass medium, while the individual sites and services are the components of which this medium is comprised.

This concept has been assumed to be a natural attribute of interpersonal communication, but, as explicated by Rafaeli (1988) , it is more recently applied to all new media, from two-way cable to the Internet. From Rafaeli's perspective, the most useful basis of inquiry for interactivity would be one grounded in responsiveness. Rafaeli's definition of interactivity “recognizes three pertinent levels: two-way (noninteractive) communication, reactive (or quasi-interactive) communication, and fully interactive communication” (1988, p. 119). Anyone working to conceptualize Internet communication would do well to draw on this variable and follow Rafaeli's lead when he notes that the value of a focus on interactivity is that the concept cuts across the mass versus interpersonal distinctions usually made in the fields of inquiry. It is also helpful to consider interactivity to be variable in nature, increasing or decreasing with the particular Internet service in question.

Though research of mass media use from a uses-and-gratifications perspective has not been prevalent in the communication literature in recent years, it may help provide a useful framework from which to begin the work on Internet communication. Both Walther (1992b) and Rafaeli (1986) concur in this conclusion. The logic of the uses-and-gratifications approach, based in functional analysis, is derived from “(1) the social and psychological origins of (2) needs, which generate (3) expectations of (4) the mass media and other sources, which lead to (5) differential patterns of media exposure (or engagement in other activities), resulting in (7) other consequences, perhaps mostly unintended ones” ( Blumler and Katz, 1974 ).

Rosengren (1974) modified the original approach in one way by noting that the “needs” in the original model had to be perceived as problems and some potential solution to those problems needed to be perceived by the audience. Rafaeli (1986) regards the move away from effects research to a uses-and-gratifications approach as essential to the study of electronic bulletin boards (one aspect of the Internet medium). He is predisposed to examine electronic bulletin boards in the context of play or Ludenic theory, an extension of the uses-and-gratifications approach, which is clearly a purpose that drives much of Internet use by a wide spectrum of the population. Rafaeli summarizes the importance of this paradigm for electronic communication by noting uses-and-gratifications' comprehensive nature in a media environment where computers have not only home and business applications, but also work and play functions.

Additionally, the uses-and-gratifications approach presupposes a degree of audience activity, whether instrumental or ritualized. The concept of audience activity should be included in the study of Internet communication, and it already has been incorporated in one examination of the Cleveland Freenet ( Swift, 1989 ).

These approaches have been applied to CMC use by organizational communication researchers to account for interpersonal effects. But social presence theory stems from an attempt to determine the differential properties of various communication media, including mass media, in the degree of social cues inherent in the technology. In general, CMC, with its lack of visual and other nonverbal cues, is said to be extremely low in social presence in comparison to face-to-face communication ( Walther, 1992a ).

Media richness theory differentiates between lean and rich media by the bandwidth or number of cue systems within each medium. This approach ( Walther, 1992a ) suggests that because CMC is a lean channel, it is useful for simple or unequivocal messages, and also that it is more efficient “because shadow functions and coordinated interaction efforts are unnecessary. For receivers to understand clearly more equivocal information, information that is ambiguous, emphatic, or emotional, however, a richer medium should be used” (p. 57).

Unfortunately, much of the research on media richness and social presence has been one-shot experiments or field studies. Given the ambiguous results of such studies in business and education ( Dennis & Gallupe, 1993 ), it can be expected that over a longer time period, people who communicate on Usenets and bulletin boards will restore some of those social cues and thus make the medium richer than its technological parameters would lead us to expect. As Walther (1992a) argues: “It appears that the conclusion that CMC is less socioemotional or personal than face-to-face communication is based on incomplete measurement of the latter form, and it may not be true whatsoever, even in restricted laboratory settings” (p. 63). Further, he notes that though researchers recognize that nonverbal social context cues convey formality and status inequality, “they have reached their conclusion about CMC/face-to-face differences without actually observing the very non-verbal cues through which these effects are most likely to be performed” (p. 63).

Clearly, there is room for more work on the social presence and media richness of Internet communication. It could turn out that the Internet contains a very high degree of media richness relative to other mass media, to which it has insufficiently been compared and studied. Ideas about social presence also tend to disguise the subtle kinds of social control that goes on on the Net through language, such as flaming.

Grant (1993) has suggested that researchers approach new communication technologies through network analysis, to better address the issues of social influence and critical mass. Conceptualizing Internet communities as networks might be a very useful approach. As discussed earlier, old concepts of senders and receivers are inappropriate to the study of the Internet. Studying the network of users of any given Internet service can incorporate the concept of interactivity and the interchangeability of message producers and receivers. The computer allows a more efficient analysis of network communication, but researchers will need to address the ethical issues related to studying people's communication without their permission.