Roman Jakobson papers

- Print Generating

- Collection Overview

- Collection Organization

- Container Inventory

Scope and Contents

While the scope and content notes with each series of guide to the Roman Jakobson papers describe the contents of the collection sequentially, this note provides a topical overview of Jakobson's life and accomplishments and suggests where in the collection material on a topic may be found. Because so much revolves around Czechoslovakia, a discussion of relevant material is first, followed by a description of materials on specific scholarly topics. Czechoslovakia Jakobson came to Czechoslovakia as a young man of twenty-four in 1920 as a member of the first Soviet foreign mission. There he continued his education, adopted Czechoslovakia as his cultural homeland, became a professor of linguistics, and established a reputation as a linguistic scholar. Unfortunately, the collection contains little material from this crucial and formative period of Jakobson's life. In 1939, when he fled to escape Nazi persecution, most of his personal and professional papers were lost. A few items, including correspondence with Count N. S. Trubetzkoy and some of his notebooks of lectures, were hidden by friends and later sent to him in the United States. As a press attaché of the first communist government in Europe, Jakobson was often viewed with suspicion, both personally and professionally (see Series 7). However, as he continued his studies in Prague and later taught at Masaryk University in Brno, participating actively in the intellectual and artistic life of the country, his contributions won him the respect of his colleagues and new countrymen (see writings about Jakobson between 1920 and 1939). Jakobson was one of the founders in 1926 of the Prague Linguistic Circle, and he served as vice-president for thirteen years. Originally an association of six linguists, it grew into the most advanced and influential linguistic school of thought in pre-war Europe. Unfortunately, no papers survive from this important era in Jakobson's life. Also lacking is documentation on Devetsil, an avant-garde group of prominent young poets, writers, and artists who enthusiastically supported new socialist ideas. (They chose for their name the Czech word for a healing herb.) Two poems by Vítězslav Nezval, an outstanding young poet and member of Devetsil, written for Jakobson and probably in Nezval's hand, can be found in General Correspondence (Subseries 8A, box 119c, folder 94). There are also some letters from another member, Jaroslav Seifert, winner of the 1984 Nobel Prize for Literature. These letters are from the 1960s and are filed in Universities - Foreign (Series 3, box 4, folders 19-22). Jakobson's activities as a professor of linguistics at Masaryk University from 1930 to 1939 are documented in lecture notes and course outlines. These provide comprehensive summaries of some of Jakobson's views and research on Czech medieval poetry, Russian phonology and grammar, and the Byzantine mission (Subseries 6B, Unpublished Writings, box 31). The collection also contains a nearly complete record of Jakobson's scholarly output from the Czech years, copies of and some background material for nearly 300 articles and studies he wrote between 1926 and 1939 (Subseries 6A, Published Writings). He received increasing support from the Czech scholarly community, which recognized his contribution to the development of Czech linguistics and literary analysis (Series 7, box 38). Jakobson's ties to Czechoslovakia remained strong after his escape in 1939. His respect for Czech culture and tradition were publicized in Moudrost starých Čechů (The Wisdom of the Old Czechs), his detailed defense of Czech culture against the pseudo-scientific attacks promoted by Nazi collaborators (boxes 9 & 10). The work was the result of extensive study and research, reflected partially in previously published articles (1938i, 1939f, & 1939g) and documented further by extensive research notes. Once in the United States, Jakobson contributed to Czech journals and Czech American newspapers (see Subseries 6a, Published Writings) and spoke out strongly against Czech emigré author Egon Hostovsky for portraying Czech intellectuals as Nazi collaborators in his book Seven Times in the Main Role . Jakobson argued that writers should be held morally responsible for what they publish. This position embroiled him in a debate with other emigrés who advocated artistic freedom under any circumstances. Jakobson's arguments and the fierce attacks of his opponents are well documented (box 32, folders 47 & 48; box 38, folder 48). After the Communists took power in Czechoslovakia in 1948, Jakobson's ties with the country were cut off. Under the liberal Dubcek regime, Jakobson was invited to attend the Slavic Congress held in Prague in 1968. His second visit followed the Soviet invasion in 1969 when Jakobson attended a symposium on Constantine the Philosopher. Jakobson sensed that it might be his last visit and delivered an address at the close of the symposium expressing his undiminished affection for the country and heritage in which he had spent his early manhood (Unpublished Writings, box 35, folder 19). Jakobson continued to correspond with friends in Czechoslovakia. Letters from friends such as linguist Bohuslav Havranek and Ladislav Novomesky, writer, poet, friend, and member of Devetsil, reveal the close ties Jakobson maintained with that country. The correspondence with Jan Mukarovsky, a structuralist and close friend, ends in 1948, when Mukarovsky recanted his former work and rejected his friends. Topical Areas Researchers looking for material on specific topics should look first in Published Writings. The documentation of Jakobson's published work is organized chronologically, based on Stephen Rudy's bibliography Roman Jakobson 1896-1982: A Complete Bibliography of His Writings , 1990), but the topical arrangement of Selected Writings can be used as a subject guide. The Published Writings section includes a large amount of notes and background material on the subjects Jakobson wrote about, filed with the appropriate articles. The material in Published Writings is not referred to in this description. See instead the Scope and Contents note for Series 6. General Linguistics and Structuralism The term "structuralism" was probably first used by Jakobson at the I International Congress of Linguistics in The Hague in 1928. Jakobson and the Prague Linguistic School developed the structuralist and functional approach to language and the concept of markedness, starting in the area of phonology, which was later extended to morphology and syntax. Jakobson continued to develop his particular method of structural analysis throughout his career. He first introduced it to American students in his courses at École Libre and Columbia. As an early example we have notes for a course called "Structural Linguistic Analysis" from the 1940s (box 32, folder 38). The principles of structural analysis and the concept of a synchronic and diachronic view of language are summarized in transcripts of two lectures Jakobson gave in Prague in 1957: "Synchronie a diachronie v jazykovědě" and "Zásady strukturální analýzy" (box 34, folders 37-42). Drafts and numerous notes for an entry for Enciclopedia Italiana in the 1970s summarize Jakobson's most general ideas of structuralism (Unpublished Writings, box 36, folders 1-15). Jakobson's linguistic studies are represented in the collection by his lectures, of which there are transcripts, tapes, and notes. In 1976-1977 Jakobson presented a number of lectures on the history of linguistics in which he gave an overview of the development of the field. These include "Saussurean and Contemporary Linguistics" of 1965, the "History of Linguistics" series from the 1970s, "Six Decades I have Witnessed" of 1976, "Three Lectures" and "Remarks on Structuralism" of 1976, and "Present Vistas" given at MIT in 1977 (box 36). Jakobson's early linguistic research was oriented to phonology and done with the cooperation of other prominent linguists such as Horace Lunt, Morris Halle, and Gunnar Fant. This research is documented in materials related to his activities at Harvard and MIT. For more detailed information, see the Scope and Contents note for Universities - United States - Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The records filed under "Linguistics" and "Research Laboratory of Electronics" document research in communication processes (box 3, folders 74 -77 & 80-82). One of the richest sources on linguistics in the unpublished material is the complete transcript of ten lectures presented at the International Seminar in Linguistic Theory in Tokyo in 1967 (where Jakobson presented his linguistic theories in detail). It is likely that it was for these lectures that Jakobson drew together his notes on various areas of linguistics, now filed in Unpublished Writings, box 35, folders 32-57. Slavic Studies During his career, Jakobson made numerous contributions to the study of Slavic antiquities, literature, mythology, and folklore, both oral and written, as well as poetics and comparative studies. As early as the 1930s, Jakobson was captivated by the Cyrillo-Methodian mission. Course notes from classes taught at Masaryk University in 1936-1937 show that his interest was not only from the linguistic perspective, i.e., Church-Slavonic as the oldest Slavic script and literary language, but from a social viewpoint as well. He saw in the work of Constantine the Philosopher (Cyril) the earliest evidence of attempts at national self-determination and the first manifestation of democratic ideals (box 31, folders 79 & 80). Notes from the 1950s concerning the Christianization of the Slavs offer more insight into Jakobson's views on the significance of the subject (box 33, folders 29 & 30). While Jakobson's scholarly contributions to Slavic studies were many, his efforts to encourage and support the spread of Slavic programs in the United States and Europe were equal. Once in the United States, Jakobson became a leading figure in the organization of Slavic departments at Columbia and Harvard, and he helped find jobs for many emigrants from Nazi Europe (box 2, folders 13-15 & 29-31). Notes and drafts of courses and lectures on Slavic history and civilization illustrate the material he used to train a new generation of Slavists (Unpublished Writings, box 32). Jakobson worked to organize Slavists in an international network. Correspondence, work plans, resolutions, minutes, and reports document his organizing efforts and his participation in Slavic conferences, congresses, and symposia. Records of the Slavic International Congresses and the International Committee of Slavists present a picture of an international community of scholars and Jakobson's influence on that community, as well as an outline of the development of Slavic studies in the United States over a period of forty years (boxes 4 & 5). Additional material on Slavic congresses and publications is found in Universities - United States - Harvard University (Dumbarton Oaks, box 2, folder 47). Included is Jakobson's correspondence with his longtime colleague and friend, Byzantine scholar Father Francis Dvorník. Russian Studies Jakobson, a Russian native, taught Russian language and literature throughout his life. Notes from his earliest lectures from Brno deal with all aspects of the Russian language, especially Russian phonology (box 31, folders 48-60). The course notes represent the essence of Jakobson's approach to Russian studies, showing all his innovations in linguistics, most significantly the development of his theory of distinctive features. Jakobson continued to develop his phonological investigation of the Russian language at Harvard in the early 1950s. With Gunnar Fant and Morris Halle, he systematically defined the relationships among all known phonetic features (box 2, folders 55-59; box 6, folders 37 & 38). Drafts and extensive notes document Jakobson's work on Russian morphology (Russian declension, nouns, and verbs) where Jakobson applied the principles he discovered in his phonological studies. The material documents Jakobson's innovative approach to the study of the structure of the verb and the Russian case system. There are, in all, ten courses on Russian, including a comprehensive set of lecture notes from the Harvard years. Numerous notes and drafts illustrate his interest in Russian literature. Much of Jakobson's work on Russian epic tradition is documented in his work on the Igor' Tale, the classic epic, the authenticity of which Jakobson demonstrated in 1948 in La Geste du Prince Igor(Scope and Contents note, Published Writings). Jakobson's relationship with his friend Vladimir Maíàkovskii found expression in his structural insights into several of Maíàkovskii's poems (see Published Writings). In an interview with Swedish radio Jakobson remembered him as a friend as well as a poet (box 36, folder 35). There is also a transcript of a discussion at the Institute of World Literatures in Moscow in 1956 where Jakobson talked about his publications about Maíàkovskii and his relationship with Teodor Nette (box 34, folder 36). Jakobson's work on Russian poetess Marina Tsvetaeva is documented in a response to Simon Karlinsky's review of the English translation of Tsvetaeva's poems. Jakobson analyzed her poem "Pis'm" (A Letter) in detail and drafted a short article criticizing Karlinsky's failure to understand her verses (box 34, folders 94-96; box 35, folder 1). Notes for studies on Pasternak, Esenin, and Pushkin document more of Jakobson's work on Russian poetry (box 35, folders 10, 22-27). As a major Russian scholar, Jakobson was asked to act as consultant on several projects with other scholars and institutions. Correspondence with Wayne State University, 1963-1967, documents his role as consultant on the publication of a new Russian dictionary (box 4, folder 6) and a Russian textbook published by the Nature Method Center. The textbook's method was based on learning vocabulary and grammatical structure in the situational context (box 30, folders 73-77). In 1980 Jakobson presented a series of lectures, "Universal Paths of Russian Language, Literature, and Culture," at Wellesley College. Notes for this series summarize his work and views on Russian language and literature (box 36, folders 74-80). Semiotics According to Umberto Eco in "The Influence of Roman Jakobson on the Development of Semiotics," Jakobson was "the major catalyst in the contemporary semiotic reaction," and his entire work was a quest for semiotics. Jakobson's linguistic writings testify to that observation. Jakobson himself did not publish extensively on the subject of semiotics. We have only notes contained in four folders in Unpublished Writings (box 35, folders 65-68). He gave important lectures on the subject, however, such as "Signatum a Designatum" delivered at the Colloque International de Semiologie in Krazmierz, Poland, in 1966, of which we have a draft (box 34, folder 77). There are also notes for "Some Questions of Linguistic Semantics," given in Moscow in 1966, and other lectures given in Chicago and France in 1970 and 1972. Additional material describing Jakobson's interest in the subject of semiotics is found in records of his participation in semiotic congresses, symposia, conferences, and seminars (box 5, folders 21-23; box 6, folders 4-11), including correspondence with Umberto Eco, Julia Kristeva and others. Some of the letters concern Jakobson's attendance at events and some are related to reviews of books and articles on semiotics, revealing Jakobson's cooperation with the journal Semiotics.

- Creation: 1908 - 1982

- Jakobson, Roman, 1896-1982 (Person)

Language of Materials

Includes material in English, French, German, Russian, Czech, and other Slavic languages.

Conditions Governing Access

Materials in this collection are open unless they are marked as restricted. Restrictions are noted in the container list.

Intellectual Property Rights

Copyright of of materials in this collection is retained by the Roman Jakobson Trust.

Conditions Governing Use

Access to collections in the Department of Distinctive Collections is not authorization to publish. Please see the MIT Libraries Permissions Policy for permission information. Copyright of some items in this collection may be held by respective creators, not by the donor of the collection or MIT.

Biographical Note

Roman O. Jakobson, 1896-1982, A.B., Lazarev Institute of Oriental Languages, Moscow; A.M. 1918, Moscow University; Ph.D. 1930, Prague University, taught at Masaryk University in Brno, Czechoslovakia, 1933-1939. He fled to Scandinavia when the Nazis invaded and came to the United States in 1941, where he began teaching at l'Ecole Libre des Hautes in New York. He was visiting professor of linguistics at Columbia University, 1943-1946, then was appointed to the Thomas G. Masaryk Chair of Czechoslovak Studies, a position he occupied from 1946 to 1949. In 1949 he joined the faculty of Harvard University, where he was Samuel Hazzard Cross Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures and General Linguistics until he became emeritus in 1965. He was concurrently, appointed in April 1957, Visiting Institute Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for 1957-1958 and reappointed Visiting Institute Professor for a six month period beginning July 1958. He continued in his role at MIT until he became emeritus in 1970. Jakobson's role in linguistics is unique. His work helped to define modern linguistics and gain its recognition as an independent science. He expanded the borders of linguistics to incorporate such areas as phonetics, semantics, poetics, Slavic studies, language acquisition and pathology, and mythology. His main contributions were to establish phonological distinctive features, to define constants and tendencies, variants and invariants, to discover unity in variety, with respect for the individual and unique in language. He drew upon the work of earlier linguists, especially Ferdinand de Saussure and Baudouin de Courtenay. However, his concept of linguistics and his introduction of structural methods were original and influenced linguists all over the world. His written works include books and articles on linguistic subjects, mythology, and epic poetry and metrics, including works on the Igor' Tale. His elaborated theories of language and communication have impacted such disciplines as anthropology, art criticism, and brain research.

Roman Jakobson: A Brief Chronology, compiled by Stephen Rudy

141.5 Cubic Feet (137 record cartons, 12 manuscript boxes, 1 half manuscript box, 3 card boxes, 7 folios, 1 film reel)

Additional Description

This collection documents the career of Roman Jakobson. Jakobson was Samuel Hazzard Cross Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures and General Linguistics at Harvard University from 1949 until becoming emeritus in 1965. He was concurrently, appointed in April 1957, Visiting Institute Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for 1957-1958, reappointed Visiting Institute Professor for a six month period beginning July 1958. He continued in his role at MIT until he became emeritus in 1970. Known as a founder of modern structural linguistics, he elaborated theories of language and communication that have impacted such disciplines as anthropology, art criticism and brain research. Published and unpublished writings by Jakobson, correspondence, and research and lecture notes document Jakobson's scholarly contributions to linguistics, poetics, mythology, folklore, literature, and cognitive studies. The collection also includes Jakobson's correspondence with linguist Prince Nikolai Sergeevich Trubetskoy and extensive materials concerning Jakobson's lifelong study of the Russian classic epic, Igor’ Tale.

Physical Location

Materials are stored off-site. Advance notice is required for use.

Source of Acquisiton

Materials were given to the Department of Distinctive Collections (formerly the Institute Archives and Special Collections) by Krystyna Pomarska Jakobson. Materials in boxes 135 to 150 were received in October 2012 from the Jakobson Foundation.

Bibliography

- Jakobson, Roman. Selected Writings. 8 vols. ʾs-Gravenhage: Mouton, 1962-1988 http://library.mit.edu/item/000222888 MIT Libraries

- Roman Jakobson, 1896-1982: A Complete Bibliography of His Writings, compiled and edited by Stephen Rudy. Berlin; New York : Mouton de Gruyter, 1990. http://library.mit.edu/item/000493045 MIT Libraries

Processing Information note

Box 118 was repacked into three separate boxes; 118 a, 118 b, 118c in November 2015 after conservation work done on some reprints and reprints were foldered. Container list updated to reflect correct box. Folios 1-6 were renumbered in December 2019. Folio 1 is now oversize folder 153, folios 2-5 and 7 are now in box 152, and folio 6 is now oversize folder 154.

Film in box 151 is a gift from sent from Marshall Blonsky. Can't find accession information, to do: check control file.

Conservation needed

Some paper items deteriotating in boxes 119a and in 119c, folder 81 specifically

Related Names

- Benveniste, Emile, 1902-1976 (Person)

- Bruner, Jerome S. (Jerome Seymour) (Person)

- École libre des hautes études (New York, N.Y.) (Organization)

- Dvornik, Francis, 1893-1975 (Person)

- Eco, Umberto (Person)

- Fant, Gunnar (Person)

- Ferrell, James (Person)

- Halle, Morris (Person)

- Hand, Wayland D. (Wayland Debs), 1907-1986 (Person)

- Havránek, Bohuslav (Person)

- Holenstein, Elmar (Person)

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude (Person)

- Lord, Albert Bates (Person)

- Lotz, John, 1913-1973 (Person)

- Lunt, Horace G. (Horace Gray), 1918-2010 (Person)

- Masarykova universita v Brně (Organization)

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Committee for Communications Sciences (Organization)

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir, 1893-1930 (Person)

- Mukařovský, Jan (Person)

- Nabokov, Vladimir Vladimirovich, 1899-1977 (Person)

- Nezval, Vitězslav, 1900-1958 (Person)

- Novomeský, Laco (Person)

- Ossabaw Island Project Foundation (Organization)

- Picchio, Riccardo, 1923-2011 (Person)

- Pírková-Jakobsonová, Svatava (Person)

- Pomorska, Krystyna (Person)

- Pražský linguistický kroužek (Organization)

- Ridder, Peter de, 1923-2009 (Person)

- Rudy, Stephen (Person)

- Schapiro, Meyer, 1904-1996 (Person)

- Schoonveld, C. H. van (Person)

- Sebeok, Thomas A. (Thomas Albert), 1920-2001 (Person)

- Seifert, Jaroslav, 1901-1986 (Person)

- Simmons, Ernest J. (Ernest Joseph), 1903-1972 (Person)

- Sommerfelt, Alf (Person)

- Stankiewicz, Edward (Person)

- Svejkovsky, Frantisek (Person)

- Szeftel, Marc (Person)

- Trubetskoi, Nikolai Sergeevich, kniaz, 1890-1938 (Person)

- Tsvetaeva, Marina, 1892-1941 (Person)

- Wasson, R. Gordon (Robert Gordon), 1898-1986 (Person)

- Waugh, Linda R. (Person)

- Wellek, Rene (Person)

- Whatmough, Joshua, 1897-1964 (Person)

- Wolfson, Harry Austryn, 1887-1974 (Person)

- Schmitt, Francis Otto, 1903-1995 (Person)

- Worth, Dean S. (Person)

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Department of Linguistics and Philosophy (Organization)

- Institute Professors

- Czech language -- Research.

- Czech literature -- Research.

- Linguistics -- Research

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology -- Faculty

- Semiotics -- History.

- Slavic languages -- Research.

- Slavic literature -- Research.

- Structuralism (Literary analysis) -- History.

Uniform Title

- Slovo o polku Igoreve.

Finding Aid & Administrative Information

Revision statements.

- 2021 July 12: Edited by Lana Mason to remove aggrandizing terms in the abstract, biographical, and scope and content notes description.

Physical Storage Information

- Box: 1 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 2 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 3 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 4 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 5 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 7 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 8 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 9 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 10 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 11 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 12 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 13 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 14 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 15 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 16 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 17 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 18 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 19 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 20 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 21 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 22 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 23 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 24 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 25 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 26 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 27 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 28 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 29 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 30 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 31 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 32 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 33 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 34 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 35 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 36 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 37 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 38 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 39 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 40 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 41 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 42 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 43 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 44 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 45 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 46 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 47 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 48 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 49 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 50 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 51 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 52 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 53 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 54 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 55 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 56 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 57 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 58 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 59 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 60 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 61 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 62 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 63 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 64 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 65 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 66 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 67 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 68 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 69 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 70 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 71 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 72 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 73 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 74 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 75 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 76 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 77 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 78 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 79 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 80 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 81 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 82 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 83 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 84 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 85 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 86 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 87 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 88 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 89 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 90 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 91 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 92 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 93 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 94 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 95 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 96 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 97 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 98 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 99 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 100 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 101 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 102 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 103 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 104 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 105 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 106 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 107 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 108 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 109 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 110 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 111 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 112 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 113 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 114 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 115 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 116 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 117 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 120 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 121 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 122 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 123 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 124 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 125 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 126 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 127 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 128 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 129 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 130 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 131 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 132 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 133 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 134 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 135 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 137 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 138 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 139 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 140 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 141 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 142 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 143 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 144 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 145 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 146 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 147 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 148 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 149 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 150 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 151 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 119a (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 119b (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 119c (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 136 (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 137 A (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 137 B (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 137 C (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 50A&B (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 118b (Mixed Materials)

- Box: 118a (Mixed Materials)

Repository Details

Part of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Libraries. Department of Distinctive Collections Repository

Collection organization

Roman Jakobson Papers, MC-0072, box X. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Distinctive Collections, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Cite Item Description

Roman Jakobson Papers, MC-0072, box X. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Distinctive Collections, Cambridge, Massachusetts. https://archivesspace.mit.edu/repositories/2/resources/633 Accessed May 21, 2024.

Get Reference Help | Submit a Correction Privacy | Permissions | Accessibility

Metadata content created by MIT Libraries is CC BY-NC , unless otherwise noted. Notify us of copyright concerns.

Russia’s role in world politics: power, ideas, and domestic influences

- Introduction

- Published: 03 May 2018

- Volume 56 , pages 713–725, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Elias Götz 1 &

- Neil MacFarlane 2

1687 Accesses

6 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

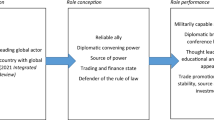

Russia’s role in world politics has become the object of a spirited debate among policymakers, think-tank analysts, and academics. Much of this debate focuses on one central question: What are the main drivers, or causes, of Moscow’s increasingly proactive and assertive foreign policy? The purpose of this special issue is to address this question by focusing on the interplay of power, ideas, and domestic influences. Our introductory article sets the scene for this analytical endeavor. More specifically, the article has three aims: (1) to review the existing explanations of Moscow’s assertiveness; (2) to discuss the challenges, opportunities, and benefits of employing eclectic approaches in the study of Russian foreign policy; and (3) to outline the contributions of the articles that follow.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Australia and the Ukraine crisis: deterring authoritarian expansionism

Bringing imperialism back in: for an anthropology against empire in the twenty-first century.

Identity, status and role in UK foreign policy: Brexit and beyond

Allison, R. 2013. Russia and Syria: Explaining alignment with a regime in crisis. International Affairs 89 (4): 795–823.

Google Scholar

Ambrosio, T. 2006. The political success of Russia-Belarus relations: Insulating Minsk from a color revolution. Demokratizatsiya 14 (3): 407–434.

Ambrosio, T. 2009. Authoritarian Backlash: Russian Resistance to Democratization in the Former Soviet Union . Burlington: Ashgate.

Bock, A.M., I. Henneberg, and F. Plank. 2014. “If you compress the spring, it will snap back hard”: The Ukrainian crisis and the balance of threat theory. International Journal 70 (1): 101–109.

Bremmer, I., and S. Charap. 2007. The Siloviki in Putin’s Russia: Who they are and what they want. Washington Quarterly 30 (1): 83–92.

Byman, D.L., and K.M. Pollack. 2001. Let us now praise great men: Bringing the statesman back in. International Security 25 (4): 107–146.

Cadier, D. 2015. Policies towards the Post-Soviet Space: The Eurasian Economic Union as an Attempt to Develop Russia’s Structural Power? In Russia’s foreign policy: Ideas, domestic politics and external relations , ed. D. Cadier, and M. Light, 156–174. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cadier, D., and M. Light. 2015. Conclusion: Foreign policy as the continuation of domestic politics by other means. In Russia’s foreign policy: Ideas, domestic politics and external relations , ed. D. Cadier, and M. Light, 204–216. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Charap, S., and C. Welt. 2015. Making sense of Russian foreign policy. Problems of Post-Communism 62 (2): 67–70.

Checkel, J.T. 2013. Theoretical pluralism in IR: Possibilities and limits. In Handbook of international relations , 2nd ed, ed. W. Carlsnaes, T. Risse, and B.A. Simmons, 220–241. London: Sage.

Clunan, A.L. 2009. The social construction of Russia’s resurgence: Aspirations, identity, and security interests . Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Clunan, A.L. 2014. Historical aspirations and the domestic politics of Russia’s pursuit of international status. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 47 (3–4): 281–290.

Cohen, A. 2007. Domestic factors driving Russia’s foreign policy . Washington, DC: Backgrounder No. 2048, The Heritage Foundation.

Forsberg, T., R. Heller, and R. Wolf. 2014. Special issue: Status and emotions in Russian foreign policy. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 47 (3–4): 261–268.

Forsberg, T., and C. Pursiainen. 2017. The psychological dimension of Russian foreign policy: Putin and the annexation of Crimea. Global Society 31 (2): 220–244.

Götz, E. 2015. It’s geopolitics, stupid: Explaining Russia’s Ukraine policy. Global Affairs 1 (1): 3–10.

Götz, E. 2017. Putin, the state, and war: The causes of Russia’s near abroad assertion revisited. International Studies Review 19 (2): 228–253.

Hill, R. 2015. How Vladimir Putin’s world view shapes Russian foreign policy. In Russia’s foreign policy: Ideas, domestic politics and external relations , ed. D. Cadier, and M. Light, 42–61. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hopf, T. 2002. Social construction of international politics: Identities and foreign policies, Moscow, 1955 and 1999 . Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Hopf, T. 2005. Identity, legitimacy, and the use of military force: Russia’s great power identities and military intervention in Abkhazia. Review of International Studies 31 (S1): 225–243.

Hopf, T. 2006. Moscow’s foreign policy, 1945–2000: Identities, institutions, and interests. In The Cambridge History of Russia (Vol. 3): The Twentieth Century , ed. R.G. Suny, 662–705. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hopf, T. 2016. ‘Crimea is ours’: A discursive history. International Relations 30 (2): 227–255.

Jupille, J., J.A. Caporaso, and J.T. Checkel. 2003. Integrating institutions: Rationalism, constructivism, and the study of the European Union. Comparative Political Studies 36 (1–2): 7–40.

Kagan, R. 2008. The return of history and the end of dreams . New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Kaplan, R.D. 2016. Eurasia’s coming anarchy: The risks of Chinese and Russian weakness. Foreign Affairs 95 (2): 33–41.

Korolev, A. 2017. Theories of non-balancing and Russia’s foreign policy. Journal of Strategic Studies (online first). https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2017.1283614 .

Article Google Scholar

Krastev, I., and S. Holmes. 2014. Russia’s aggressive isolationism. The American Interest , 10 December.

Krickovic, A. 2016. Catalyzing conflict: The internal dimension of the security dilemma. Journal of Global Security Studies 1 (2): 111–126.

Krickovic, A. 2017. The symbiotic China-Russia partnership: Cautious riser and desperate challenger. The Chinese Journal of International Politics 10 (3): 299–329.

Larson, D.W., and A. Shevchenko. 2010. Status seekers: Chinese and Russian responses to U.S. primacy. International Security 34 (4): 63–95.

Larson, D.W., and A. Shevchenko. 2014. Russia says no: Power, status, and emotions in foreign policy. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 47 (3–4): 269–279.

Mankoff, J. 2007. Russia and the West: Taking the longer view. Washington Quarterly 30 (2): 123–135.

Marten, K. 2015. Informal political networks and Putin’s foreign policy: The examples of Iran and Syria. Problems of Post-Communism 62 (2): 71–87.

Matz, J. 2001. Constructing a post-Soviet international political reality: Russian foreign policy towards the newly independent states, 1990–95 . Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.

Mearsheimer, J.J. 2014. Why the Ukraine crisis is the West’s fault: The liberal delusions that provoked Putin. Foreign Affairs 93 (5): 77–89.

Mendras, M. 2015. The rising cost of Russia’s authoritarian foreign policy. In Russia’s foreign policy: Ideas, domestic politics and external relations , ed. D. Cadier, and M. Light, 80–96. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mercer, J. 2017. The illusion of international prestige. International Security 41 (4): 133–168.

Monteiro, N.P., and K.G. Ruby. 2009. IR and the false promise of philosophical foundations. International Theory 1 (1): 15–48.

Neumann, I.B. 2008. Russia as a great power, 1815–2007. Journal of International Relations and Development 11 (2): 128–151.

Neumann, I.B. 2016. Russia’s Europe, 1991-2016: Inferiority to superiority. International Affairs 92 (6): 1381–1399.

Nye Jr., J.S. 2015. The challenge of Russia’s decline. Project Syndicate , 14 April.

Saradzhyan, S. 2016. Is Russia declining? Demokratizatsiya 24 (3): 399–418.

Shevtosva, L. 2010. Lonely power . Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Sil, R. 2009. Simplifying pragmatism: From social theory to problem-driven eclecticism. International Studies Review 11 (3): 648–652.

Sil, R., and P.J. Katzenstein. 2010. Beyond paradigms: Analytical eclecticism in the study of world politics . London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Smith, S. 2003. Dialogue and the reinforcement of orthodoxy in international relations. International Studies Review 5 (1): 141–143.

Staun, J. 2007. Siloviki vs. liberal - technocrats: The fight for Russia and its foreign policy . DIIS Report No. 9. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies.

Tansey, O. 2016. The problem with autocracy promotion. Democratization 23 (1): 141–163.

Tsygankov, A.P. 2006. Projecting confidence, Not Fear: Russia’s Post-Imperial Assertiveness. Orbis 50 (4): 677–690.

Tsygankov, A.P. 2009. Russia in the post-western world: The end of the normalization paradigm? Post-Soviet Affairs 25 (4): 347–369.

Tsygankov, A.P. 2010. Russia’s foreign policy: Change and continuity in national identity , 2nd ed. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Tsygankov, A.P. 2012. Russia and the West from Alexander to Putin: Honor in international relations . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vanderhill, R. 2013. Promoting authoritarianism abroad . Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Way, L.A. 2015. The limits of autocracy promotion: The case of Russia in the ‘near abroad’. European Journal of Political Research 54 (4): 691–706.

Wilson, A. 2014. The Ukraine crisis brings the threat of democracy to Russia’s doorstep. European View 13 (1): 67–72.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Uppsala University, Box 514, 75120, Uppsala, Sweden

Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford, Manor Road Building, Manor Road, Oxford, OX1 3UQ, UK

Neil MacFarlane

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Elias Götz .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Götz, E., MacFarlane, N. Russia’s role in world politics: power, ideas, and domestic influences. Int Polit 56 , 713–725 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-018-0162-0

Download citation

Published : 03 May 2018

Issue Date : December 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-018-0162-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Foreign policy

- International relations theory

- Analytical eclecticism

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Econ Journal Watch

Scholarly comments on academic economics, adam smith and his russian admirers of the eighteenth century, by michael p. alekseev, read this article.

- Read Now PDF

Mikhail Pavlovich Alekseev (1896–1981) was, at the time of his passing, “generally recognized as the most eminent living Russian specialist…

Reproduced here is an essay by Michael P. (Mikhail Pavlovich) Alekseev. In the 1760s two students from Russia, Semyon Efimovich Desnitsky (1740–1789) and Ivan Andreevich Tretyakov (1735–1776), attended Glasgow University, learned directly from Adam Smith, John Millar, and others, returned to Russia, and commenced a tradition of Smithian thought in Russia. Alekseev tells of other Russian Smithians including N. S. Mordinov (1754–1845), Ekaterina Romanovna Dashkova (1744–1810), Alexander Romanovich Vorontsov (1741–1805), Semyon Romanovich Vorontsov (1744–1832), Christian von Schlözer (1774–1831), Heinrich Friedrich von Storch (1766–1835), M. A. Balugiansky (1769–1847), Nikolay Turgenev (1789–1871), and the great author Alexander Pushkin (1799–1837). Alekseev writes: “After the war of 1812 Adam Smith became extremely popular among the liberal youth of Russia who were organizing secret circles. In endowing the hero of his novel Eugene Onegin with a taste for economic problems and by making him read Adam Smith, Pushkin merely reproduced the actual feature of the time, the writer himself having had the same taste.”

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

From "Icons in Space" to Space in Icons: Pictorial Models for Public and Private Ritual in the Thirteenth-Century Mosaics of San Marco in Venice" in Alexei Lidov. ed., Hierotopy. Comparative Sutdies of Sacred Spaces (Moscow: Indrik, 2009)

Related Papers

Johanna Bokedal

Alexei Lidov , Maria Lidova , Maria Cristina Carile , Fr. Maximos Constas , jelena bogdanovic , Andreas Rhoby , Annemarie Carr

Word and Image 28.2

Rossitza Schroeder

Jelena Trkulja

John Peponis , Gianna Stavroulaki

We analyze the principles that govern the visibility of icons in churches and museums. We develop methods for enriching visibility analysis by taking into consideration not only the arrangement but also the illumination of space. Finally, we suggest that there are some important differences between the viewing principles that apply in churches, as sites of primary familiarization, and museums as sites of recontextualization of icons.

Maria Lidova

Spatial icons. The miraculous performance with the Hodegetria of Constantinople. In the book: Hierotopy. Creation of Sacred Spaces in Byzantium and Medieval Russia. Edited by A. Lidov. Published by “Progress-tradition” in Moscow, 2006, p. 349-372.

Alexei Lidov

This paper aims to present a historical reconstruction of a very powerful, but up to recently almost neglected ‘spatial icon’ — the Tuesday miraculous performance with the Hodegetria of Constantinople. Spatial icons are iconic images created in space. It is a new layer of subjects never discussed before in the history of Byzantine art and culture. The Hodegetria performance consisted of carrying a heavy icon by a single bearer on his shoulders giving the impression that the icon carried a bearer, hence this performance was also named “the flying Hodegetria”. This ritual was likely to have appeared as a commemoration-reenactment of the miraculous deliverance of Byzantium in year 626, when the siege of the city was raised after the icon was carried around the wall of the city. The creators of the Tuesday performance did not mean to present a historical drama reconstructing a particular event, but they used the paradigmatic story of the year 626 to make an iconic re-enactment of the Virgin’s appearance and miraculous protection over the city and a cosmic image of salvation. The Tuesday performance might be considered as a special type of Byzantine creativity, that I term hierotopy.

Sladjana Jovanovic

David Narvaez

Fifth International Space Syntax Symposium, Delft University of Technology, (ed.Akkelies van Nes), Delft, The Netherlands, Vol.2, 251-263

Gianna Stavroulaki

RELATED PAPERS

Chamara Seneviratne

Efstratios Stylianidis

Umweltwissenschaften und Schadstoff-Forschung

Gerald Schmidt

Applied Soil Ecology

petra van vliet

Journal of Studies in Science and Engineering

Eugene Atamewan

Kaywalee Chatdarong

Intellectica. Revue de l'Association pour la Recherche Cognitive

Philippe Lalitte

42th INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF REPRESENTATION DISCIPLINES TEACHERS. CONGRESS OF UNIONE ITALIANA PER IL DISEGNO. PROCEEDINGS 2020. LINGUAGGI

Giovanna Spadafora

Wardani Muhamad

17-Trần Hoàng Trung Kiên

Quaternary International

MAHESH THAKKAR

Mélanie Tiago

Journal of Clinical Medicine

giuseppe uccello

DOAJ (DOAJ: Directory of Open Access Journals)

Moira Zuazo

Bernard Fontaine

Annals of Physics

Janos Polonyi , Pierre Gosselin

Circulation Journal

Chaoyang Chen

RePEc: Research Papers in Economics

Tor Eriksson

Teologia w Polsce

Sławomir Zatwardnicki

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Advanced Search

Article Navigation

The frist comprehensive publication conceived

China pictorial.

China Pictorial launched in 1950 and designed as a vehicle for presenting captivating photographs alongside informative and interesting articles, China Pictorial became the first comprehensive publication conceived after the founding of the People's Republic in 1949. The inceptive masthead of the magazine was inscribed by the late Chairman Mao Zedong.

For more than 50 years, China Pictorial has been devoted to covering major domestic and international events, reporting on those issues most important to the people, reflecting dramatic reforms of society and bearing full witness to the rapid development of China. It has been distributed throughout China, covering all provinces, municipalities, autonomous regions, the Hong Kong and Macao Special Administrative Regions, as well as more than 100 countries and regions around the world.

Today, China Pictorial has reshaped itself and diversified its business. There are the Chinese and English edition of China Pictorial, the Russian and Korean edition of China, and the Chinese edition of Vogue—all in print, and the editions of China Pictorial at the website.

A National Journal of Literature & Discussion

The Sad State of Cultural Life In Moscow (Or Peking) As Viewed From Peking (Or Moscow)

By lowell r. tillett.

During the last decade Cold War rhetoric has taken an unexpected turn. The quantity and intensity of angry exchanges between capitalism and Communism have subsided almost everywhere, while the two major practitioners of Communism have been having it out. Moscow and Peking have blasted each other with charges more scurrilous and personal than the wildest anti-Communist might have ventured in the fifties. In May, 1970, the New York Times, reflecting on the fact that Mao had included in his celebration of Lenin’s centennial a comparison of Brezhnev and Hitler, and Moscow had reciprocated with a charge that Mao was a philanderer who had murdered his own son, observed that “even at the height of the Cold War, it is doubtful that any official American pronouncement matched, much less exceeded, the bitterness” of such exchanges.

Lost in the shadoAvs of the more newsworthy arguments about borders, nuclear war, and leadership of world Communism, is another aspect of the unprecedented Sino-Soviet ideological quarrel—a no-holds-barred and below-the-belt brawl on the nature and function of culture in a Communist society. Each of the Communist giants contends that the other is a traitor to Marxism and has done irreparable harm to the cause of proletarian culture.

This enormous, orchestrated propaganda campaign is carried on not only in the press, but especially by round-the-clock broadcasts over the back fence from Radio Moscow and Radio Peking. The Soviet Party journal Kommunist complained in 1969 that two-thirds of some Chinese newspapers were filled with anti-Soviet material and that Radio Peking was broadcasting to the USSR up to fifty hours per day on forty frequencies, including some reserved for distress calls. The Soviet press and radio were answering on the same scale, the latter intensifying its effort beginning in that year through “Radio Peace and Progress,” beaming broadcasts from Tashkent in the languages of the Chinese minority peoples, as well as standard Chinese.

The campaign has had its ups and clowns. It grew more and more intense from 1967, reaching a peak in the summer of 1969. It was then turned off like a faucet for a few months—neither Moscow nor Peking saying a disparaging word about the other—while border talks were being held. It has had periodic outbursts since. The Soviets have recently made occasional references to the relaxation of Mao’s cultural policies, but have not retreated from their basic charges. The Chinese have not retreated one iota, but have observed long periods of silence on the subject.

Each side holds that the other has strayed from the Marxist path and betrayed the proletariat. The method of betrayal is the same in either case: the Communist Party of China (or the Soviet Union) has been “kidnapped” by a small clique, which is building its power and ruling for selfish goals. Each side assigns a definite date to the betrayal. The Chinese claim that Stalin hewed to the Marxist line, but soon after his death that “buffoon,” Khrushchev, and his “renegade revisionist clique” began a clandestine but systematic program for “the all-round restoration of capitalism.” The Soviets hold that at roughly the same time the Chinese Party lost its battle against Mao, who is not a Marxist at all, but an unprincipled opportunist Avho has built a fearful “personality cult” through purge and intimidation.

The cultural policies of each power, as observed by the other, are an important manifestation of the Marxist heresy and a means of realizing the tyrants’ goals. Each side presents a caricature of the other and in the process reveals something about itself. The Chinese have concentrated on detecting and exposing capitalistic characteristics in Soviet culture; the Soviets have dwelt on the wild, romantic, whimsical experimentation of Maoism, which “has nothing in common with Marxism.”

In support of their proposition that the Soviet “renegades” are restoring capitalism, the Chinese point to what they consider scandalous wage differentials and examples of high living, in the worst tradition of bourgeois capitalists, among Soviet leaders. These cases prove to Chinese satisfaction that a new class division is growing in the USSR and that the class struggle—that hallmark of a capitalist society—is not only present, but is intensifying.

The Chinese find many examples of extravagant living among the “high-salaried privileged stratum.” While among Soviet workers “two or three families share a single room,” the tycoons are concerned about luxurious second houses by the sea. One villa on the Black Sea “has two swimming pools, one for fresh water and another for salt water” and another has a special room for the master’s dog. While Soviet workers suffer from periodic food shortages, their leaders enjoy “beef and mutton from Mongolia, champagne from France, onions from Poland, grapes from Bulgaria.” And while the Avorkers complain of shortages of shoes and underwear, the privileged squander hard currency on imported fashions. As evidence, the Chinese once wryly quoted a compliment from the camp of the enemy: Die Welt’s opinion that the Soviet Union “has never seen a Party chief as fashionable as Brezhnev . . ., with a silvery grey necktie and an impeccable, well-tailored black suit, he is so smartly groomed that he gives no thought at all about Lenin’s style of dress.”

It is little wonder that Soviet leaders, seduced by these capitalist comforts, should be diverted from the causes of the people. “When these fat and comfortable Communists . . .tog themselves up in Italian fashion, sip a glass of martini [sic] and bounce to the rhythm of American jazz, how it is possible for them to think of the liberation fighters in the South Vietnamese jungles, the starving peasants in the Indian countryside, and the Afro-Americans in Harlem?”

The evils of the system are not confined to the “upper strata,” but have seeped down to another group which can only be identified by its capitalist nomenclature, the middle class. The Chinese have denounced such capitalist trappings as pawnshops, classified advertising, and the free markets where agricultural products and handicrafts are sold by individuals. When the Moscow Pawnshops Administration tried in 1967 to promote its operations by offering better guarantees, transactions by telephone, and even house calls by the pawnbroker, the Chinese press rose to the occasion, asking rhetorically, “Just what is a pawnshop?. . . Whatever the color of its signboard, and whatever its sidelines, its main business is usury, in other words, sucking the blood out of the poor. It is rather strange that thriving pawnbrokers should be a sign of the transition to Communism and that the workers will enter Communist society with wads of pawn tickets in their pockets.”

The Chinese were also disturbed by the proliferation of classified advertisements in the Moscow evening newspaper. The mere existence of such ads was regarded as prima facie evidence of a capitalist society, since “advertising in the bourgeois press is a medium by which capitalists push sales, carry out cut-throat competition, and grab profits.” But the Chinese turned the knife in the wound by noting the business being transacted: villas and summer cottages wanted, medals wanted, lottery tickets wanted, jobs wanted, and divorce announcements. “Multiplying like fungi , . . .these ads reek with the stink of bourgeois ideology and way of life.”

The Chinese share with the Russians great fears about the profit motive in the private sector of Soviet agriculture. They regard the free markets, where products from the private plots are sold as “a paradise for kulaks and speculators. . . . In the free markets, people rub shoulders in crowds. They push and jostle each other. It is a sickening scene of noise and confusion, with hawkings to attract customers, angry bargaining, etc.”

The Chinese also detect signs of restored capitalism in the trappings of popular culture in the USSR. What could be more symptomatic of decadent bourgeois society than fashion shows, fashion magazines, beauty shops, nude pictures, fancy wedding ceremonies, dog shows, and comic strips?

According to the Chinese, “the Soviet revisionists have discarded the plain working-class clothing of Lenin for the sophisticated styles of the bourgeoisie.” They publish “fashion and hair style magazines to corrupt the Soviet people, particularly the youth,” and have staged fashion shows at home and abroad. At one “Soviet fashion design show” in Washington, the models wore fashions by “the Soviet Union’s best-known avant garde designer, who copied the cowboy pants and mini-skirts of the West.”

The Chinese claim that even the Communist Youth League, the customary apprenticeship to the Communist Party, has entered the race for fashion and beauty. They were alarmed to find out that “there is a Beauty Parlor for Young Communist League Members and Youths” in Leningrad, where discussions on “new hair fashions” and “hair-do contests” are held every Sunday. And “in Moscow, so-called clubs for girls have been set up in some cultural palaces to attract young women workers to study “the secrets of beauty culture” and “problems of love. ” Is this following the behest of Lenin?”

It is only a short step from the fashion show to the even more decadent dog show. “The Soviet revisionists also put on dog shows in Moscow similar to those in New York and London and went so far as to make this thing fashionable. All this is the height of rottenness.”

In popular Soviet wedding ceremonies, Peking detects a throwback to tsarist days. “In Moscow nowadays, one often sees troikas of the type common in the days of old Russia galloping by. They carry no ordinary passengers, but cater to newlyweds,” carrying them to the wedding palace. The hiring of troikas has become a thriving business, for, according to TASS, “wedding vehicles have been booked up for the whole spring season.”

For the younger set, Soviet authorities have tried to make learning about scientific subjects more palatable by using the form of the comic strip. The Chinese reaction was this:

The Soviet revisionists have resorted to new methods of corrupting the young by churning out “science” fiction and comics modeled after “Alley-Oop,” “Blonclie,” “Batman,” etc. Under the pretext of disseminating scientific knowledge, such garbage from the Soviet press fosters venomous fantasy.

Having set the Soviet Union on such a dangerous course, the leaders have accepted the uglier features of bourgeois society—unsavory night life, increasing crime, alcoholism, and prostitution. When the Soviet press called on recreation officials to “brighten up night life,” the Chinese press wondered what the workers, who “toil from dawn to dusk,” could possibly do with a nightclub. They have no time to loaf, and such “decadent and licentious recreation is completely alien” to them. Nightclubs are “the hallmark of the Western way of life” where “bourgeois ladies and gentlemen and their offspring, who fatten on the sweat and blood of the working people . . .squander their ill-gotten gains.” And “since night clubs are being readied, brothels, gambling houses, and other such foul trades will also make their public appearance before long.”

On at least one of these subjects, alcoholism, the Chinese get plenty of ammunition from the Soviet press. But characteristically they accentuate the negative, citing the most glaring cases from Soviet articles, without acknowledging that the whole purpose of the Soviet discussion is remedial. They suggest that Ivan drinks a lot to cover his disillusionment with the régime, his sorrow for a revolution betrayed.

The Soviet counterpart of the Chinese charges of restored capitalism in the USSR is the contention that Mao’s erratic ideas and adventurism have wrecked traditional Chinese culture and have not put anything worthwhile in its place. Maoist thoughts not only drive out the harder currency of creative ideas; they serve as a religious opiate: “Mao Tse-tung’s thoughts do not differ from the religious intoxicants which develop the minds of the people and promise them a better lot—in another world.” Furthermore, Mao has a deep anti-intellectual streak (“the more books you read, the more stupid you become”) and Chinese intellectuals have been the scapegoats for the failure of his many experiments. As a result of all this, the Soviets see China as a cultural wasteland.

According to Marxism cultural life, like almost everything else, is based on economic underpinnings and the Soviets contend that Mao has failed the Chinese people at this basic point. The standard of living in China remains at a very low level, and there is no plan to improve it substantially in the foreseeable future. According to Mao’s doctrine of “primitive asceticism” all incentiA r es to material gain are denounced, and poverty is a virtue. While the Chinese rail against wage differentials in the USSR, the Russians deplore the grinding poverty of the whole Chinese population, a condition which is accepted and lauded by the leadership. One Soviet spokesman cited the chorus from a popular Chinese play:

First you walked barefoot. Then you put on rag slippers, and then—rubber shoes. This time you may wish to sport leather shoes, or even high boots. What will become of you in this process of bourgeois degradation?

Another Soviet position in this quarrel rings strange in the Western ear, for vis-à-vis the Chinese, they are champions of the rights of the individual against the demands of the state. They charge that Mao has so completely subdued, “brainwashed,” and regimented the Chinese people that there are no areas of individual freedom left, and this includes all cultural life at a personal level. The demands for group activity are so great that a Chinese can no longer enjoy the simplest pleasures—taking a walk, going fishing, playing cards, or taking a nap on his day off. Such activities have been condemned as bourgeois. One Soviet broadcast lamented Mao’s purge of billions of goldfish. “The Peking press, . . .calling for greater revolutionary vigilance, urged the people to destroy the fishbowls and to carry out the revolution, because goldfish breeding was an assault by the bourgeoisie on the proletariat.”

The goal of Maoist cultural policy, in the Soviet view, is to reduce the individual to the rôle of an ant in the giant anthill. Several phrases on this theme, which were upheld as ideals in China during the Cultural Revolution, have been quoted in contempt in Soviet propaganda. Workers are asked to become “little stainless screws” in Mao’s machine. According to the diary of a Chinese soldier, “although a cog is small, its rôle is inestimable. I want to be a cog always, . . .cleaned and protected so that it does not rust.” The peasant’s variant has him aspiring to be “an obedient buffalo of the great helmsman,” and children pledge themselves as “red seedlings.”

Chinese culture has been submerged in the morass of Mao worship. Instead of reading traditional Chinese literature (much of which has perished in the flames of the Cultural Revolution) Chinese children memorize twenty quotations per day from Mao’s thought. Mao quotations are chanted at meals and at public rallies. “From the very early morning Peking’s streets are filled with a roar which comes from loudspeakers. . . . It is impossible to collect one’s thoughts and think about what is happening.” There is no escape in visiting the theater or the music hall, in listening to the radio, or reading the popular press, which are all saturated with Mao themes.

The Soviets are also, rather surprisingly, the champions of traditional cultural values and have given much attention to the cultural nihilism of the Cultural Revolution. While the Chinese were citing Marx and Lenin passages calling for the destruction of bourgeois culture and the remolding of intellectuals, the Soviets have cited other passages emphasizing the need for continuity and critical assimilation of the culture of the past.

In the fine arts the Chinese are somewhere to the right of Stalin; they advocate socialist realism with a vengeance. Every work of art is judged strictly on its utility in furthering the revolution, and any work that does not do so in a straightforward way is a “poisonous weed” which must be eradicated. One of the earliest criticisms of Khrushchev’s cultural policy was that he had permitted the rehabilitation of “revisionist royalist writers” who had quite properly been suppressed by Stalin. Among these were Mikhail Zoshchenko and Anna Akhmatova, who shared the heresy of ideological neutrality in some of their works. Like Stalin, the Chinese regard non-conforming literature to be extremely detrimental: “a single bullet can only kill a single person, but the influence of a single reactionary novel can harm ten thousand people.”

The Chinese have attacked more than a dozen Soviet writers, but their main efforts have been made against three. Mikhail Sholokhov has drawn more fire from Chinese critics than all other Soviet writers combined. They regard him as the most dangerous kind of cultural figure, a counter-revolutionary who manages to hoodwink his countrymen, a “termite that sneaked into the revolutionary camp.”

In the Chinese view, Sholokhov’s works are full of counter-revolutionary messages, and his characters are not properly oriented. In “And Quiet Flows the Don” Grigory is an out-and-out white guard, whose tragic experiences are treated sympathetically. Sholokhov weighs the personal sufferings of his characters against the Revolution and questions whether the sacrifice was worth it. Furthermore, the author “exaggerated the counter-revolutionary rebellion,” stated openly that “there were too many bad elements” in the Bolshevik Party, and pointed out the “excessive actions” of the Red Army against the enemy-—all “impermissible” according to Maoist literary standards. In “Virgin Soil Upturned” Sholokhov “maliciously distorted the features of the poor and lower-middle peasants and vilified them as opponents of collectivization.” He “prettifies the class enemy” and “describes collectivization as a series of endless disasters.”

Sholokhov’s Nobel prize confirms Chinese suspicions. “Sholokhov, in a state of awed excitement, accepted the Nobel prize for literature, which even the French bourgeois writer Jean-Paul Sartre would not accept. In Sartre’s words, to accept the prize would be to receive “a distinction reserved for the writers of the West or for the traitors of the East. “”

Konstantin Simonov’s popular war novels, “The Living and the Dead” and “Days and Nights,” have been attacked for their strong condemnation of war. In Mao’s view the violence and destructiveness of wars should not be emphasized to the exclusion of the positive results of just wars, which are the means by which the working class will destroy imperialism. In Mao’s words, “war is politics with bloodshed.” But Simonov’s novels, concerning the German invasion of Russia in 1941 and the battle of Stalingrad, view war in a totally negative way. There is too much gore, not enough glory. The main characters only want to survive—to survive for such selfish reasons as to return to a lover or to school. Simonov would “stamp out the flames of peoples’ revolutionary wars.” Besides, he emphasizes the might of the German army and the weakness of the Red Army. He had the Red Army falling back to Stalingrad because of weakness and not to launch a counter-attack, as the Chinese prefer to have it.

Yevgeny Yevtushenko, who is always referred to as a “playboy poet,” has committed all the cardinal sins: he has condemned Stalin, China, and written anti-war poetry. Furthermore, he is a writer “who sold his soul” to United States imperialism. He first came to fame for “brutally defaming Stalin after the Twentieth Congress of the CPSU. This clown described himself as “weeping like all others when Stalin died. ” Yet before his tears were dry, he had trod upon Khrushchev’s heels in attacking Stalin.” Yevtushenko’s “mud-slinging” poems against the Cultural Revolution have drawn heavy fire from the Chinese, as have his popular recital trips to the West.

Soviet criticism of the current Chinese literary scene seldom involves specific writers or works, since the main Soviet complaint is that the Cultural Revolution and the Maoist cult have destroyed old literary works and prevented new ones from being written. “In effect, sentence of death has been pronounced on China’s centuries-old culture.” A 1969 broadcast charged that not a single novel had been published in China during the last four years and that the author of the last one was soon in trouble. The fate of foreign literature in China was equally bad. According to Sovetskaya Kultura, “between 1949 and 1956, 2683 works of classical Russian and Soviet literature had been published in the Chinese language in a total of 66,500,000.” But these have all been swept away in “the prairie fire of the Cultural Revolution.” Soviet accounts are full of descriptions of book burning, the destruction of bookshops and libraries, and of trash heaps which serve as collection points for condemned literature. Meanwhile three billion copies of Mao’s works have been turned out in China.

The Russians do single out one Chinese writer for biting criticism, and it cuts to the quick: they have a very low opinion of the literary efforts of Mao Tse-tung. His poems are always vague and sometimes incomprehensible. One of the Russian translators of Mao’s poetry stated in an interview that “these verses are incomprehensible, not merely on first reading; even readers with philological education cannot explain the meaning of some phrases exactly.” Red Guards sing Mao’s words “frequently without understanding their meaning.”

Furthermore, Mao’s poetry is ideologically suspect. The Soviet verdict on one of his poems was that “it is merely an imitation of decadent court poetry, full of embellishing phrases.” Other Soviet critics have noted that “Mao’s imagination has always been captivated by the imagery and personalities of the rulers of old imperial China. Moreover, Mao’s personality has clear traces of the characteristics of the Chinese Emperors.” Radio Moscow has broadcast detailed analyses of “Yellow Stork Flying,” one of Mao’s most popular poems, detecting almost precise figures found in the verse of one of the Tang emperors, “an aesthete, whose life . . .was given over to meditations concerning the apparition of the yellow stork.”

“Counter-revolutionary plays dominate the Soviet stage”—so reads a typical Chinese critique. Popular Soviet plays are condemned for sowing “the virus of pacifism,” “distorting facts about the anti-fascist war” with Hitler, “repudiating the Stalin cult, vilifying the dictatorship of the proletariat,” and for advocating “a life of eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow you die.”

Chinese objections to the Soviet theater center about their attacks on Konstantin Stanislavsky, whose method acting has drawn frequent fire from Peking. The core of the method, as the Chinese see it, is the “self,” the “innermost I.” Such “stinking egoism” is a betrayal of class consciousness. According to the method, the actor who plays a landlord or capitalist must delve into his sub-consciousness and evoke all those hated traits of the class enemy. He “becomes” the landlord or capitalist and presents his new “self” in the best possible light. This is intolerable for current Chinese critics, who argue that all characters, including the darkest villains, must be played from a proletarian viewpoint. There must never be the slightest doubt about the true colors of the actors; the theater must occupy itself with showing the class struggle in action. “If the proletariat does not turn the theater into a red revolutionary crucible, then the bourgeoisie will change it into a black and stinking dyeing vat, disseminating the ideological poison of the bourgeoisie and contaminating the ideology of the masses.”

Soviet films come in for the same treatment. Blunderbuss attacks on Soviet films strongly suggest that the Chinese critics have not had an opportunity to see what they are condemning, the giveaway coming in some variation of the clause: “such titles alone suffice to show what these movies peddle and what sort of creatures their producers are.”

One favorite theme of Chinese critics is the growing popularity of United States films in the USSR. Peking regarded the Moscow Film Festival of 1969 as “a sickening spectacle of dewy-eyed admirers standing spellbound before the altar of Western imperialist films, . . .a disgusting exhibition of the clique’s maneuver to use the junk cranked out by the bourgeois scum . . .to promote the full-scale capitalist restoration.”

Among Soviet film figures the director Grigory Chukrai shares the villainous rôle of Sholokhov among the Chinese, and for some of the same reasons. His pictures are soft on war, and besides he made the tactical error of commenting unfavorably on Chinese films in an article for the British magazine, Films and Filming, observing that “with dogmatism and logic alone the Chinese artist cannot make good films.” Taking on his best known films one by one, a Chinese critic condemned “The Forty-First” as a flimsy love story, in which “human nature overcomes class nature, and the enemies become lovers”; “Ballad of a Soldier” is really a “condemnation of war, [showing] how the anti-fascist patriotic War wrecked people’s happiness”; “The Clear Sky” is an anti-Stalin diatribe: “when Stalin dies, “the ice melts” and “the sky clears. ” ” Chukhari’s films are all revisionist, reeking of the “odor of bourgeois humanism and pacifism.”

The Soviet view of Chinese theater and film is similar to that on literature, emphasizing cultural nihilism and political subservience. By one Soviet account, “of 3,000 theatrical companies which existed until quite recently, less than ten are alive. The silence of the Chinese theater is proof of the crisis in its art, until recently extremely popular and widespread in China.” The “spectacular revolutionary plays” which have replaced the classics are artistically worthless, and are mere propaganda pieces. “The theater in China has become a primitive means of frontal propaganda for the political lines of the present leadership.”

The Soviets also react sharply to the repudiation of Stanislavsky and to the Chinese practice of casting all characters from the proletarian viewpoint. One Soviet visitor reported a shocking experience on a visit backstage in Peking: “I was looking for the actor whom we liked very much and who appeared in the rôle of a Japanese intelligence officer. Finally I discovered him at the end of the line; it turned out that he had no right to stand next to the actors appearing in positive rôles.”

Soviet critics also regret the demise of the popular theater in China.

In the old days Chinese rural areas were blessed with popular forms of art; Chinese theatrical performers would tell stories and give performances and magic shows. . . . Thousands upon thousands of native theatrical groups used to roam from village to village giving performances, but the Maoists today have wiped out the native arts the same way they have wiped out the professional arts.

The Russians have complained about the arid film fare as well. They have from time to time reeled off the titles of films showing in Peking; all feature Chairman Mao in the titles, and most are produced by his wife, Chiang Ching. Chinese documentaries are especially deplored for their anti-Soviet bias.

Impugning the merits of “Swan Lake” is for the Russians as low a blow as discrediting Mao’s poetry for the Chinese. A Red Guard penned the following reaction:

Treasured as a masterpiece by people like you and your kind, the ballet “Swan Lake” has been going on and on for decades but the performances remain the same. What can “Swan Lake” arouse in a revolutionary of this era . . .except disgust for its corrosive rôle in leading people astray into a world far removed from real life?

A presumably more mature critic in Red Flag found it to be “a cacophony of primitive dance melodies [which] can in no way compare with the elevated music being written today in China to the words of Mao Tse-tung.” The plot is as bad as the music: “Evil genius romps about the stage, suppressing everything, while devils have become the main characters! This is indeed a sinister picture of the restoration of capitalism on the stage.”

Soviet music critics weep for the fate of the Peking opera, whose rich repertory of hundreds of masterpieces has been eliminated and replaced by a handful of worthless “revolutionary model operas.” One reason the Peking opera had to go was that Mao’s henchmen felt implied threats from its Aesopian language: “in every character, in every situation, the Maoists’ sick imagination felt an allusion.” The same fate has befallen the ballet, whose ballerinas now carry rifles to attack imaginary bourgeois fortresses.

The Chinese critics are most indignant of all when it comes to popular music—specifically the Soviet surrender to the wishes of young people to hear jazz and other mod music from the West.

Disguised as “cultural co-operation,” degenerate Western music, commercialized jazz, has become the rage in the Soviet revisionist musical, dancing, and theatrical world. . . . As a result, various weird-named American and British jazz bands have performed in the Soviet Union.

The Russians could hardly be expected to defend jazz festivals, but they do counter such charges with their own broadsides against the politicization of popular music. In one commentary they noted that the stirring old songs of the Chinese revolutionary movement had been abandoned, and new words had been set to the tunes. The new lyrics “praise Mao, his current policies, and the threat of war from the Soviet Union” and are “published in all newspapers and endlessly broadcast by the radio.”