- Our Writers

- How to Order

- Assignment Writing Service

- Report Writing Service

- Buy Coursework

- Dissertation Writing Service

- Research Paper Writing Service

- All Essay Services

Speech Writing

Introduction Speech

Introduction Speech - A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

11 min read

People also read

The 10 Key Steps for Perfect Speech Writing

Understanding Speech Format - Simple Steps for Outlining

How to Start A Speech - 13 Interesting Ideas & Examples

20+ Outstanding Speech Examples for Your Help

Common Types of Speeches that Every Speechwriter Should Know

Good Impromptu Speech Topics for Students

Entertaining Speech Topics for Your Next Debate

Understanding Special Occasion Speech: Types, Steps, Examples and Tips

How to Write the Best Acceptance Speech for Your Audience?

Presentation Speech - An Ultimate Writing Guide

Commemorative Speech - Writing Guide, Outline & Examples

Farewell Speech - Writing Tips & Examples

How to Write an Extemporaneous Speech? A Step-by-Step Guide

Crafting the Perfect Graduation Speech: A Guide with Examples

Introduction speeches are all around us. Whenever we meet a new group of people in formal settings, we have to introduce ourselves. That’s what an introduction speech is all about.

When you're facing a formal audience, your ability to deliver a compelling introductory speech can make a lot of difference. With the correct approach, you can build credibility and connections.

In this blog, we'll take you through the steps to craft an impactful introduction speech. You’ll also get examples and valuable tips to ensure you leave a lasting impression.

So, let's dive in!

- 1. What is an Introduction Speech?

- 2. How to Write an Introduction Speech?

- 3. Introduction Speech Outline

- 4. 7 Ways to Open an Introduction Speech

- 5. Introduction Speech Example

- 6. Introduction Speech Ideas

- 7. Tips for Delivering the Best Introduction Speech

What is an Introduction Speech?

An introduction speech, or introductory address, is a brief presentation at the beginning of an event or public speaking engagement. Its primary purpose is to establish a connection with the audience and to introduce yourself or the main speaker.

This type of speech is commonly used in a variety of situations, including:

- Public Speaking: When you step onto a stage to address a large crowd, you start with an introduction to establish your presence and engage the audience.

- Networking Events: When meeting new people in professional or social settings, an effective introduction speech can help you make a memorable first impression.

- Formal Gatherings: From weddings to conferences, introductions set the tone for the event and create a warm and welcoming atmosphere.

In other words, an introduction speech is simply a way to introduce yourself to a crowd of people.

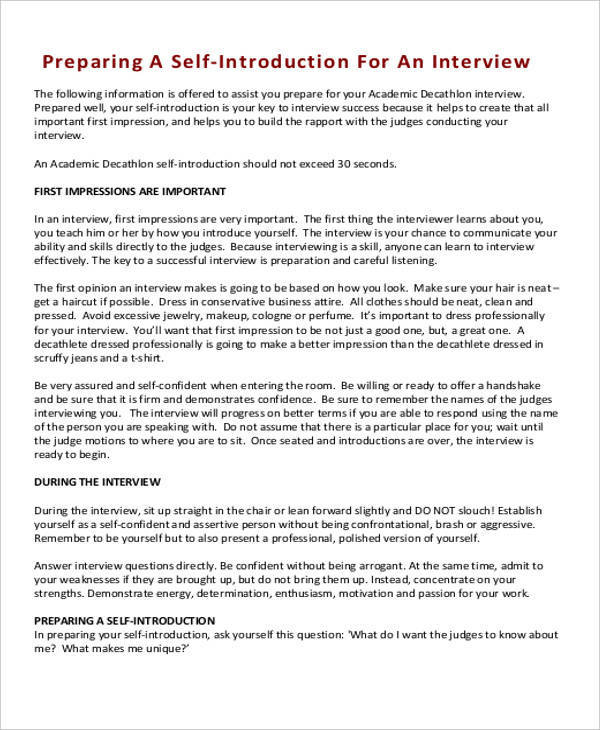

How to Write an Introduction Speech?

Before you can just go and deliver your speech, you need to prepare for it. Writing a speech helps you organize your ideas and prepare your speech effectively.

Here is how to introduce yourself in a speech.

- Know Your Audience

Understanding your audience is crucial. Consider their interests, backgrounds, and expectations to tailor your introduction accordingly.

For instance, the audience members could be your colleagues, new classmates, or various guests depending on the occasion. Understanding your audience will help you decide what they are expecting from you as a speaker.

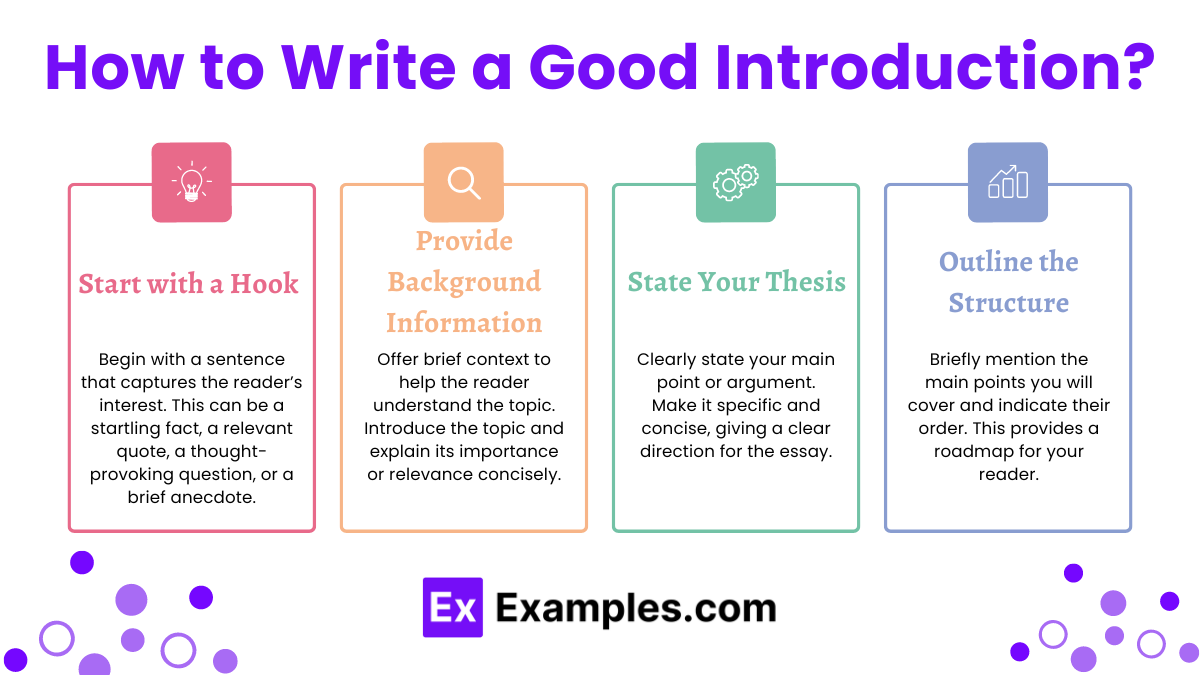

- Start with a Hook

Begin with a captivating opening line that grabs your audience's attention. This could be a surprising fact, a relevant quote, or a thought-provoking question about yourself or the occasion.

- Introduce Yourself

Introduce yourself to the audience. State your name, occupation, or other details relevant to the occasion. You should mention the reason for your speech clearly. It will build your credibility and give the readers reasons to stay with you and read your speech.

- Keep It Concise

So how long is an introduction speech?

Introduction speeches should be brief and to the point. Aim for around 1-2 minutes in most cases. Avoid overloading the introduction with excessive details.

- Highlight Key Points

Mention the most important information that establishes the speaker's credibility or your own qualifications. Write down any relevant achievements, expertise, or credentials to include in your speech. Encourage the audience to connect with you using relatable anecdotes or common interests.

- Rehearse and Edit

Practice your introduction speech to ensure it flows smoothly and stays within the time frame. Edit out any unnecessary information, ensuring it's concise and impactful.

- Tailor for the Occasion

Adjust the tone and content of your introduction speech to match the formality and purpose of the event. What works for a business conference may not be suitable for a casual gathering.

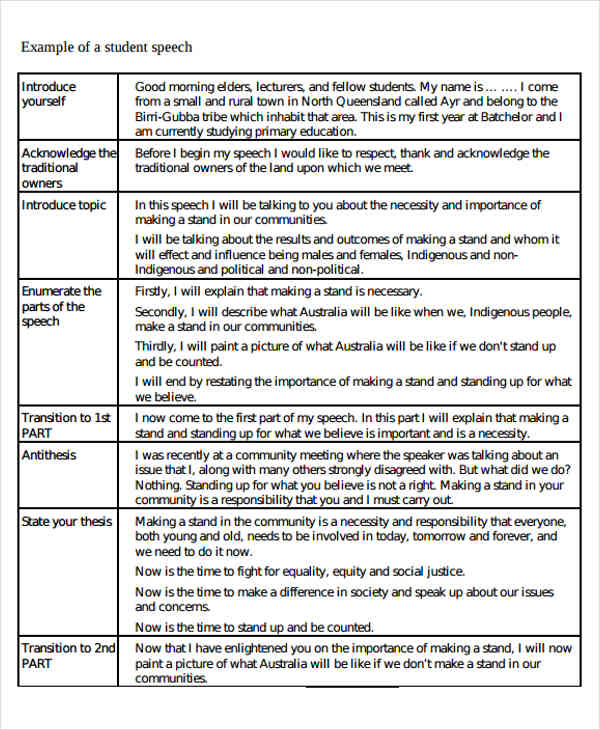

Introduction Speech Outline

To assist you in creating a structured and effective introduction speech, here's a simple outline that you can follow:

|

Here is an example outline for a self-introduction speech.

Outline for Self-Introduction Speech

7 Ways to Open an Introduction Speech

You can start your introduction speech as most people do:

“Hello everyone, my name is _____. I will talk about _____. Thank you so much for having me. So first of all _______”

However, this is the fastest way to make your audience lose interest. Instead, you should start by captivating your audience’s interest. Here are 7 ways to do that:

- Quote

Start with a thought-provoking quote that relates to your topic or the occasion. E.g. "Mahatma Gandhi once said, 'You must be the change you want to see in the world."

- Anecdote or Story

Begin with a brief, relevant anecdote or story that draws the audience in. It could be a story about yourself or any catchy anecdote to begin the flow of your speech.

Pose a rhetorical question to engage the audience's curiosity and involvement. For example, "Have you ever wondered what it would be like to travel back in time, to experience a moment in history?”

- Statistic or Fact

Share a surprising statistic or interesting fact that underscores the significance of your speech. E.g. “Did you know that as of today, over 60% of the world's population has access to the internet?”

- “What If” Scenario

Paint a vivid "What if" scenario that relates to your topic, sparking the audience's imagination and curiosity. For example, "What if I told you that a single decision today could change the course of your life forever?"

- Ignite Imagination

Encourage the audience to envision a scenario related to your topic. For instance, "Imagine a world where clean energy powers everything around us, reducing our carbon footprint to almost zero."

Start your introduction speech with a moment of silence, allowing the audience to focus and anticipate your message. This can be especially powerful in creating a sense of suspense and intrigue.

Introduction Speech Example

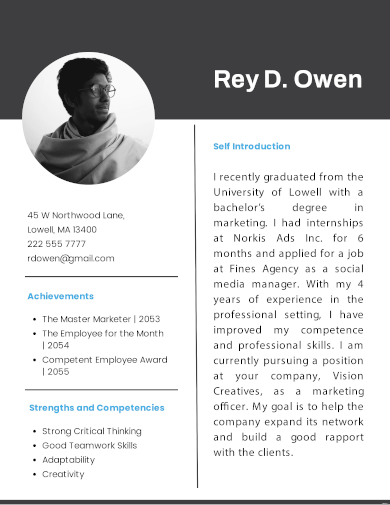

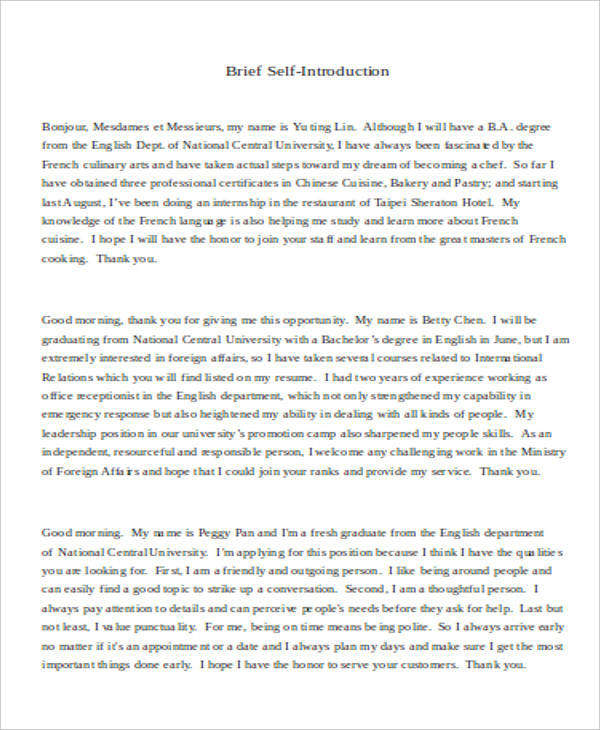

To help you understand how to put these ideas into practice, here are the introduction speech examples for different scenarios.

Introduction Speech Writing Sample

Short Introduction Speech Sample

Self Introduction Speech for College Students

Introduction Speech about Yourself

Student Presentation Introduction Speech Script

Teacher Introduction Speech

New Employee Self Introduction Speech

Introduction Speech for Chief Guest

Moreover, here is a video example of a self introduction. Watch it to understand how you should deliver your speech:

Want to read examples for other kinds of speeches? Find the best speeches at our blog about speech examples !

Introduction Speech Ideas

So now that you’ve understood what an introduction speech is, you may want to write one of your own. So what should you talk about?

The following are some ideas to start an introduction speech for a presentation, meeting, or social gathering in an engaging way.

- Personal Story: Share a brief personal story or an experience that has shaped you, introducing yourself on a deeper level.

- Professional Background: Introduce yourself by highlighting your professional background, including your career achievements and expertise.

- Hobby or Passion: Discuss a hobby or passion that you're enthusiastic about, offering insights into your interests and what drives you.

- Volunteer Work: Introduce yourself by discussing your involvement in volunteer work or community service, demonstrating your commitment to making a difference.

- Travel Adventures: Share anecdotes from your travel adventures, giving the audience a glimpse into your love for exploring new places and cultures.

- Books or Literature: Provide an introduction related to a favorite book, author, or literary work, revealing your literary interests.

- Achievements and Milestones: Highlight significant achievements and milestones in your life or career to introduce yourself with an impressive track record.

- Cultural Heritage: Explore your cultural heritage and its influence on your identity, fostering a sense of cultural understanding.

- Social or Environmental Cause: Discuss your dedication to a particular social or environmental cause, inviting the audience to join you in your mission.

- Future Aspirations: Share your future goals and aspirations, offering a glimpse into what you hope to achieve in your personal or professional life.

You can deliver engaging speeches on all kinds of topics. Here is a list of entertaining speech topics to get inspiration.

Tips for Delivering the Best Introduction Speech

Here are some tips for you to write a perfect introduction speech in no time.

Now that you know how to write an effective introduction speech, let's focus on the delivery. The way you present your introduction is just as important as the content itself.

Here are some valuable tips to ensure you deliver a better introduction speech:

- Maintain Eye Contact

Make eye contact with the audience to establish a connection. This shows confidence and engages your listeners.

- Use Appropriate Body Language

Your body language should convey confidence and warmth. Stand or sit up straight, use open gestures, and avoid fidgeting.

- Mind Your Pace

Speak at a moderate pace, avoiding rapid speech. A well-paced speech is easier to follow and more engaging.

- Avoid Filler Words

Minimize the use of filler words such as "um," "uh," and "like." They can be distracting and detract from your message.

- Be Enthusiastic

Convey enthusiasm about the topic or the speaker. Your energy can be contagious and inspire the audience's interest.

- Practice, Practice, Practice

Rehearse your speech multiple times. Practice in front of a mirror, record yourself, or seek feedback from others.

- Be Mindful of Time

Stay within the allocated time for your introduction. Going too long can make your speech too boring for the audience.

- Engage the Audience

Encourage the audience's participation. You could do that by asking rhetorical questions, involving them in a brief activity, or sharing relatable anecdotes.

Mistakes to Avoid in an Introduction Speech

While crafting and delivering an introduction speech, it's important to be aware of common pitfalls that can diminish its effectiveness. Avoiding these mistakes will help you create a more engaging and memorable introduction.

Here are some key mistakes to steer clear of:

- Rambling On

One of the most common mistakes is making the introduction too long. Keep it concise and to the point. The purpose is to set the stage, not steal the spotlight.

- Lack of Preparation

Failing to prepare adequately can lead to stumbling, awkward pauses, or losing your train of thought. Rehearse your introduction to build confidence.

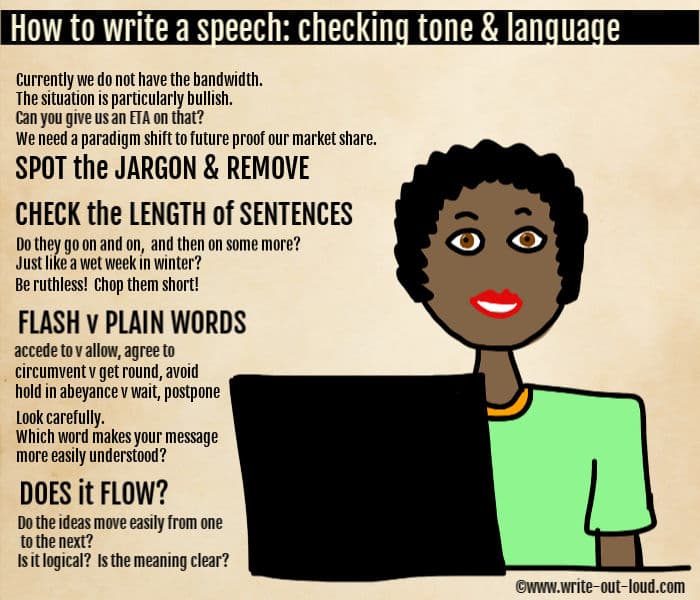

- Using Jargon or Complex Language

Avoid using technical jargon or complex language that may confuse the audience. Your introduction should be easily understood by everyone.

- Being Too Generic

A generic or uninspiring introduction can set a lackluster tone. Ensure your introduction is tailored to the event and speaker, making it more engaging.

- Using Inappropriate Humor

Be cautious with humor, as it can easily backfire. Avoid inappropriate or potentially offensive jokes that could alienate the audience.

- Not Tailoring to the Occasion

An introduction should be tailored to the specific event's formality and purpose. A one-size-fits-all approach may not work in all situations.

To Conclude,

An introduction speech is more than just a formality. It's an opportunity to engage, inspire, and connect with your audience in a meaningful way.

With the help of this blog, you're well-equipped to shine in various contexts. So, step onto that stage, speak confidently, and captivate your audience from the very first word.

Moreover, you’re not alone in your journey to becoming a confident introducer. If you ever need assistance in preparing your speech, let the experts help you out.

MyPerfectWords.com offers a custom essay service with experienced professionals who can craft tailored introductions, ensuring your speech makes a lasting impact.

Don't hesitate; hire our professional speech writing service to deliver top-quality speeches at your deadline!

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Dr. Barbara is a highly experienced writer and author who holds a Ph.D. degree in public health from an Ivy League school. She has worked in the medical field for many years, conducting extensive research on various health topics. Her writing has been featured in several top-tier publications.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

How to Start a Speech: 7 Tips and Examples for a Captivating Opening

By Status.net Editorial Team on December 12, 2023 — 10 minutes to read

1. Choosing the Right Opening Line

Finding the perfect opening line for your speech is important in grabbing your audience’s attention. A strong opening line sets the stage for the points you want to make and helps you establish a connection with your listeners.

1. Start with a question

Engage your audience from the very beginning by asking them a thought-provoking question related to your topic. This approach encourages them to think, and it can create a sense of anticipation about what’s coming next.

- “Have you ever wondered how much time we spend on our phones every day?”

2. Share a personal story

A relatable personal story can create an emotional connection with your audience. Make sure your story is short, relevant to your speech, and ends with a clear point.

- “When I was a child, my grandmother used to tell me that every kind deed we do plants a seed of goodness in the world. It was this philosophy that inspired me to start volunteering.”

3. Use a quote or a statistic

Incorporate a powerful quote or an intriguing statistic at the outset of your speech to engage your audience and provide context for your topic.

- “As the great Maya Angelou once said, ‘People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.'”

4. Make them laugh

Injecting a little humor into your opening line puts everyone at ease and makes your speech more memorable. Just make sure your joke is relevant and doesn’t offend your audience.

- “They say an apple a day keeps the doctor away, but if the doctor is cute, forget the fruit!”

5. Paint a mental picture

Draw your audience in by describing a vivid scene or painting an illustration in their minds. This creates an immersive experience that makes it easier for your audience to follow your speech.

- “Picture this: you’re walking down the beach, and you look out on the horizon. The sun is setting, and the sky is a breathtaking canvas of reds, oranges, and pinks.”

2. Using a Personal Story

Sharing a personal story can be a highly effective way to engage your audience from the very beginning of your speech. When you open your talk with a powerful, relatable story, it helps create an emotional connection with your listeners, making them more invested in what you have to say.

Think about an experience from your life that is relevant to the topic of your speech. Your story doesn’t have to be grand or dramatic, but it should be clear and vivid. Include enough detail to paint a picture in your audience’s minds, but keep it concise and on point.

The key to successfully using a personal story is to make it relatable. Choose a situation that your audience can empathize with or easily understand. For example, if you’re giving a speech about overcoming adversity, you could talk about a time where you faced a seemingly insurmountable challenge and overcame it.

Make sure to connect your story to the main point or theme of your speech. After sharing your experience, explain how it relates to the topic at hand, and let your audience see the relevance to their own lives. This will make your speech more impactful and show your listeners why your personal story holds meaning.

3. Making a Shocking Statement

Starting your speech with a shocking statement can instantly grab your audience’s attention. This technique works especially well when your speech topic relates to a hot-button issue or a controversial subject. Just make sure that the statement is relevant and true, as false claims may damage your credibility.

For example, “Believe it or not, 90% of startups fail during their first five years in the market.” This statement might surprise your listeners and make them more receptive to your ideas on how to avoid pitfalls and foster a successful business.

So next time you’re crafting a speech, consider opening with a powerful shocking statement. It could be just the thing to get your audience sitting up and paying full attention. (Try to keep your shocking statement relevant to your speech topic and factual to enhance your credibility.)

4. Using Humor

Humor can be an excellent way to break the ice and grab your audience’s attention. Opening your speech with a funny story or a joke can make a memorable first impression. Just be sure to keep it relevant to your topic and audience.

A good joke can set a light-hearted tone, lead into the importance of effective time management, and get your audience engaged from the start.

When using humor in your speech, here are a few tips to keep in mind:

- Be relatable: Choose a story or joke that your audience can easily relate to. It will be more engaging and connect your listeners to your message.

- Keep it appropriate: Make sure the humor fits the occasion and audience. Stay away from controversial topics and avoid offending any particular group.

- Practice your delivery: Timing and delivery are essential when telling a joke. Practice saying it out loud and adjust your pacing and tone of voice to ensure your audience gets the joke.

- Go with the flow: If your joke flops or doesn’t get the reaction you were hoping for, don’t panic or apologize. Simply move on to the next part of your speech smoothly, and don’t let it shake your confidence.

- Don’t overdo it: While humor can be useful in capturing your audience’s attention, remember that you’re not a stand-up comedian. Use it sparingly and focus on getting your message across clearly and effectively.

5. Incorporating a Quote

When you want to start your speech with a powerful quote, ensure that the quote is relevant to your topic. Choose a quote from a credible source, such as a famous historical figure, a well-known author, or a respected expert in your field. This will not only grab your audience’s attention but also establish your speech’s credibility.

For example, if you’re giving a speech about resilience, you might use this quote by Nelson Mandela: “The greatest glory in living lies not in never falling, but in rising every time we fall.”

Once you’ve found the perfect quote, integrate it smoothly into your speech’s introduction. You can briefly introduce the source of the quote, providing context for why their words are significant. For example:

Nelson Mandela, an inspirational leader known for his perseverance, once said: “The greatest glory in living lies not in never falling, but in rising every time we fall.”

When you’re incorporating a quote in your speech, practice your delivery to ensure it has the intended impact. Focus on your tone, pace, and pronunciation. By doing so, you can convey the quote’s meaning effectively and connect with your audience emotionally.

Connect the quote to your main points by briefly explaining how it relates to the subject matter of your speech. By creating a natural transition from the quote to your topic, you can maintain your audience’s interest and set the stage for a compelling speech.

In our resilience example, this could look like:

“This quote by Mandela beautifully illustrates the power of resilience. Today, I want to share with you some stories of remarkable individuals who, like Mandela, overcame obstacles and rose every time they fell. Through their experiences, we might learn how to cultivate our own resilience and make the most of life’s challenges.”

6. Starting with a Question

Opening your speech with a question can be a great way to engage your audience from the start. This strategy encourages your listeners to think and become active participants in your presentation. Your opening question should be related to your core message, sparking their curiosity, and setting the stage for the following content. Here are a few examples:

- For a motivational speech : “Have you ever wondered what you would do if you couldn’t fail?”

- For a business presentation : “What’s the biggest challenge your team faces daily, and how can we overcome it?”

- For an educational talk : “How does the way we use technology today impact the future of our society?”

When choosing the right starting question, consider your audience. You want to ask something that is relevant to their experiences and interests. The question should be interesting enough to draw their attention and resonate with their emotions. For instance, if you’re presenting to a group of entrepreneurs, gear your question towards entrepreneurship, and so on.

To boost your question’s impact, consider using rhetorical questions. These don’t require a verbal response, but get your audience thinking about their experiences or opinions. Here’s an example:

- For an environmental speech : “What kind of world do we want to leave for our children?”

After posing your question, take a moment to let it sink in, and gauge the audience’s reaction. You can also use a brief pause to give the listeners time to think about their answers before moving on with your speech.

7. Acknowledging the Occasion

When starting a speech, you can acknowledge the occasion that brought everyone together. This helps create a connection with your audience and sets the stage for the rest of your speech. Make sure to mention the event name, its purpose, and any relevant individuals or groups you would like to thank for organizing it. For example:

“Hello everyone, and welcome to the 10th annual Charity Gala Dinner. I’m truly grateful to the fundraising committee for inviting me to speak tonight.”

After addressing the event itself, include a brief personal touch to show your connection with the topic or the audience. This helps the audience relate to you and gain interest in what you have to say. Here’s an example:

“As a long-time supporter of this cause, I am honored to share my thoughts on how we can continue making a difference in our community.”

Next, give a brief overview of your speech so the audience knows what to expect. This sets the context and helps them follow your points. You could say something like:

“Tonight, I’ll be sharing my experiences volunteering at the local food bank and discussing the impact of your generous donations.”

Frequently Asked Questions

What are some effective opening lines for speeches.

A powerful opening line will grab your audience’s attention and set the stage for the rest of your speech. Some effective opening lines include:

- Start with a bold statement: “The world needs your creativity now more than ever.”

- Share a surprising fact: “Did you know that the average person spends (…) years of their life at work?”

- Pose a thought-provoking question: “What would you attempt to do if you knew you could not fail?”

- Tell a short, engaging story: “When I was 10 years old, I discovered my passion for baking in my grandmother’s kitchen.”

Can you provide examples of engaging introductions for speeches?

- Use humor: “As a kid, I believed that 7 pm bedtime was a form of torture. Now, as an adult, I find myself dreaming of 7 pm bedtime.”

- Share a personal experience: “On a trip to Italy, I found myself lost in the winding streets of a small village. It was there, amidst my confusion, that I stumbled upon the best gelato I’d ever tasted.”

- Use an analogy: “Starting a new business is like taking a journey into the unknown. There will be challenges to overcome, and you’ll need resilience, determination, and a strong compass.”

Which speech styles can make a powerful impact on the audience?

Different speech styles will resonate with different audiences. Some styles to consider include:

- Inspirational: Motivate your audience to take action or overcome challenges.

- Storytelling: Share personal experiences or anecdotes to illustrate your points and keep listeners engaged.

- Educational: Provide useful information and insights to help your audience learn or grow.

- Persuasive: Present a compelling argument to convince your audience to adopt a particular perspective or take specific action.

How do successful speakers establish a connection with their listeners?

Establishing a connection with your listeners is key to delivering an impactful speech. Some ways to connect with your audience include:

- Show empathy: Demonstrating understanding and concern for your audience’s feelings and experiences will generate a sense of trust and connection.

- Be relatable: Share personal stories or examples that allow your audience to see themselves in your experiences, thus making your speech more relatable.

- Keep it genuine: Avoid overrehearsing or coming across as scripted. Instead, strive for authenticity and flexibility in your delivery.

- Encourage participation: Engaging your audience through questions, activities, or conversation can help build rapport and make them feel more involved.

What are some techniques for maintaining a friendly and professional tone in speeches?

To maintain a friendly and professional tone in your speeches, consider these tips:

- Balance humor and seriousness: Use humor to lighten the mood and engage your audience, but make sure to also cover the serious points in your speech.

- Speak naturally: Use your everyday vocabulary and avoid jargon or overly formal language when possible.

- Show respect: Acknowledge differing opinions and experiences, and treat your audience with courtesy and fairness.

- Provide useful information: Offer valuable insights and solutions to your audience’s concerns, ensuring they leave your speech feeling more informed and empowered.

- Emotional Intelligence (EQ) in Leadership [Examples, Tips]

- Effective Nonverbal Communication in the Workplace (Examples)

- Empathy: Definition, Types, and Tips for Effective Practice

- How to Improve Key Communication Skills

- 38 Empathy Statements: Examples of Empathy

- What is Self Compassion? (Exercises, Methods, Examples)

Speech introductions

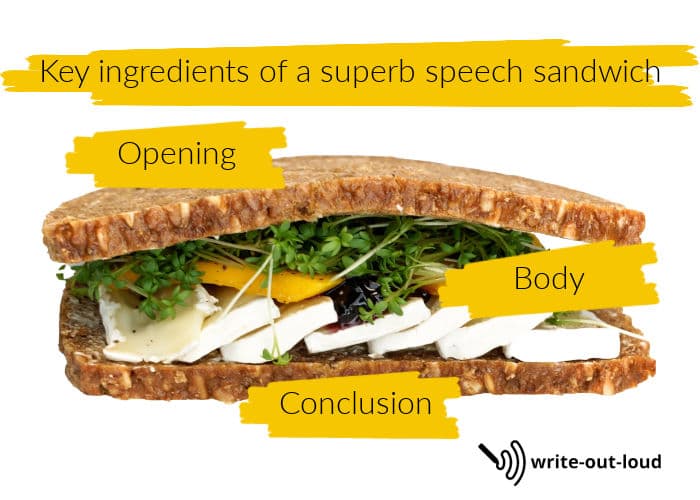

The introduction and conclusion of a speech are essential. The audience will remember the main ideas even if the middle of the speech is a mess or nerves overtake the speaker. So if nothing else, get these parts down!

Introduction

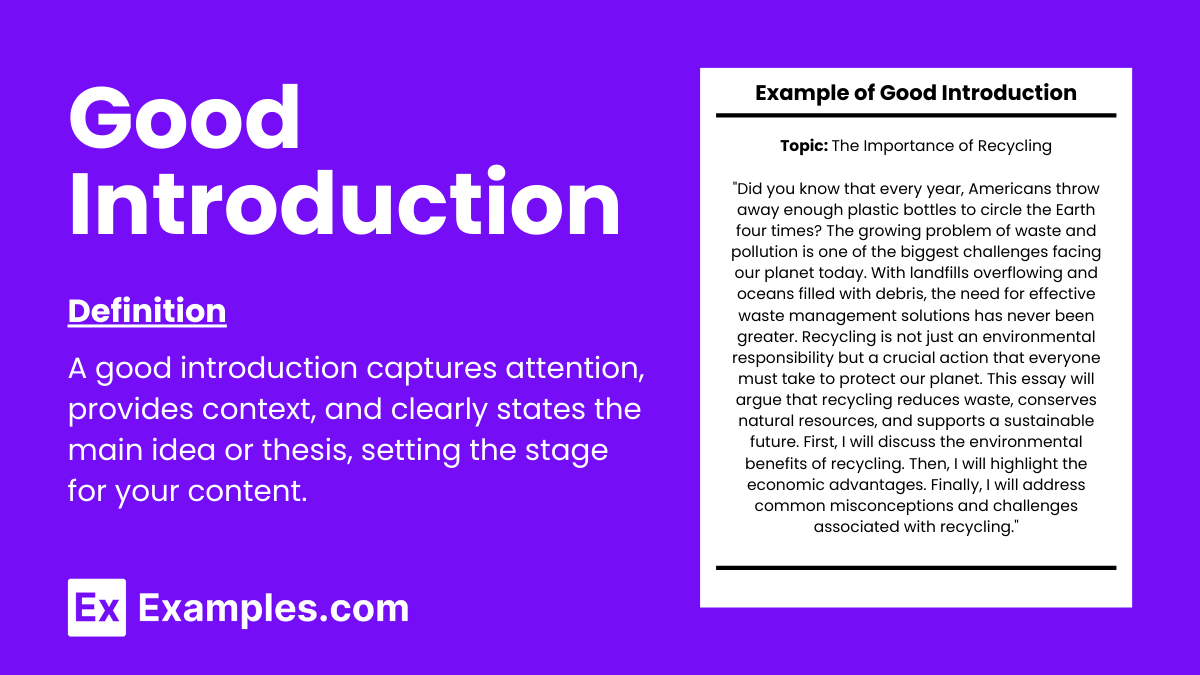

The introduction gives the audience a reason to listen to the remainder of the speech. A good introduction needs to get the audience’s attention, state the topic, make the topic relatable, establish credibility, and preview the main points. Introductions should be the last part of the speech written, as they set expectations and need to match the content.

Attention getters

The first few sentences of a speech are designed to catch and maintain the audience’s attention. Attention getters give the audience a reason to listen to the rest of the speech. Your attention getter helps the audience understand and reflect on your topic.

- Speaker walks up to stage with notes stuck to hands with jelly.

- Did you know there is a right way to make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich?

- Rob Gronkowski once said, “Usually, about 2 hours before a game, I stuff in a nice peanut butter and jelly [sandwich] with chocolate milk.”

- A little boy walks in from a long day at school, telling his mom that he is starving. His mom is confused because she knows she sent him to school with a full lunch. As she opens his lunch box, she sees his peanut butter and jelly, with the grape jelly smeared on the side of the bag. She realizes there has to be a better way to make a PB&J.

- Bring in a clear sandwich bag with jelly seeping through the bread of a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

Logical orientation

Once the audience is invested in the speech, logical orientation tells the audience how the speaker will approach and develop the topic.

- Peanut butter on both sides of the bread with jelly in the middle is the best way to make a PB&J.

- PB&Js have developed a bad reputation, because of the jelly making the bread soggy and hands sticky.

Psychological orientation

Like the logical orientation of a speech, the psychological orientation is also going to provide the audience with a map for how and why the topic is being presented.

- Most of us remember our moms – dads too – packing a peanut butter and jelly sandwich in our lunches. We also remember how the jelly did not just stay in the sandwich, but became a new stain on our shirts and the glue that held all the playground dirt to our hands.

- We can end this torture for future generations by making sure all parents are aware of the best way to make a PB&J.

- I have eaten numerous PB&Js myself, but my real authority on the topic comes from being a mom of two boys and the maker of many PB&Js.

Both the logical and psychological orientations give the audience a road map for the speech ahead as well as cues for what to listen to. This will help the audience transition from the introduction to the main points of the speech.

Beebe, S. A., & Beebe, S. J. (2012). A concise public speaking handbook . Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Lucas, S. (2012). The art of public speaking . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Sprague, J. & Stuart, D. (2013). The speaker's compact handbook, 4th ed . Portland: Ringgold, Inc.

Vrooman, S. S. (2013). The zombie guide to public speaking: Why most presentations fail, and what you can do to avoid joining the horde . Place of publication not identified: CreateSpace.

15 Powerful Speech Opening Lines (And How to Create Your Own)

Hrideep barot.

- Public Speaking , Speech Writing

Powerful speech opening lines set the tone and mood of your speech. It’s what grips the audience to want to know more about the rest of your talk.

The first few seconds are critical. It’s when you have maximum attention of the audience. And you must capitalize on that!

Instead of starting off with something plain and obvious such as a ‘Thank you’ or ‘Good Morning’, there’s so much more you can do for a powerful speech opening (here’s a great article we wrote a while ago on how you should NOT start your speech ).

To help you with this, I’ve compiled some of my favourite openings from various speakers. These speakers have gone on to deliver TED talks , win international Toastmaster competitions or are just noteworthy people who have mastered the art of communication.

After each speaker’s opening line, I have added how you can include their style of opening into your own speech. Understanding how these great speakers do it will certainly give you an idea to create your own speech opening line which will grip the audience from the outset!

Alright! Let’s dive into the 15 powerful speech openings…

Note: Want to take your communications skills to the next level? Book a complimentary consultation with one of our expert communication coaches. We’ll look under the hood of your hurdles and pick two to three growth opportunities so you can speak with impact!

1. Ric Elias

Opening: “Imagine a big explosion as you climb through 3,000 ft. Imagine a plane full of smoke. Imagine an engine going clack, clack, clack. It sounds scary. Well I had a unique seat that day. I was sitting in 1D.”

How to use the power of imagination to open your speech?

Putting your audience in a state of imagination can work extremely well to captivate them for the remainder of your talk.

It really helps to bring your audience in a certain mood that preps them for what’s about to come next. Speakers have used this with high effectiveness by transporting their audience into an imaginary land to help prove their point.

When Ric Elias opened his speech, the detail he used (3000 ft, sound of the engine going clack-clack-clack) made me feel that I too was in the plane. He was trying to make the audience experience what he was feeling – and, at least in my opinion, he did.

When using the imagination opening for speeches, the key is – detail. While we want the audience to wander into imagination, we want them to wander off to the image that we want to create for them. So, detail out your scenario if you’re going to use this technique.

Make your audience feel like they too are in the same circumstance as you were when you were in that particular situation.

2. Barack Obama

Opening: “You can’t say it, but you know it’s true.”

3. Seth MacFarlane

Opening: “There’s nowhere I would rather be on a day like this than around all this electoral equipment.” (It was raining)

How to use humour to open your speech?

When you use humour in a manner that suits your personality, it can set you up for a great speech. Why? Because getting a laugh in the first 30 seconds or so is a great way to quickly get the audience to like you.

And when they like you, they are much more likely to listen to and believe in your ideas.

Obama effortlessly uses his opening line to entice laughter among the audience. He brilliantly used the setting (the context of Trump becoming President) and said a line that completely matched his style of speaking.

Saying a joke without really saying a joke and getting people to laugh requires you to be completely comfortable in your own skin. And that’s not easy for many people (me being one of them).

If the joke doesn’t land as expected, it could lead to a rocky start.

Keep in mind the following when attempting to deliver a funny introduction:

- Know your audience: Make sure your audience gets the context of the joke (if it’s an inside joke among the members you’re speaking to, that’s even better!). You can read this article we wrote where we give you tips on how you can actually get to know your audience better to ensure maximum impact with your speech openings

- The joke should suit your natural personality. Don’t make it look forced or it won’t elicit the desired response

- Test the opening out on a few people who match your real audience. Analyze their response and tweak the joke accordingly if necessary

- Starting your speech with humour means your setting the tone of your speech. It would make sense to have a few more jokes sprinkled around the rest of the speech as well as the audience might be expecting the same from you

4. Mohammed Qahtani

Opening: Puts a cigarette on his lips, lights a lighter, stops just before lighting the cigarette. Looks at audience, “What?”

5. Darren Tay

Opening: Puts a white pair of briefs over his pants.

How to use props to begin your speech?

The reason props work so well in a talk is because in most cases the audience is not expecting anything more than just talking. So when a speaker pulls out an object that is unusual, everyone’s attention goes right to it.

It makes you wonder why that prop is being used in this particular speech.

The key word here is unusual . To grip the audience’s attention at the beginning of the speech, the prop being used should be something that the audience would never expect. Otherwise, it just becomes something that is common. And common = boring!

What Mohammed Qahtani and Darren Tay did superbly well in their talks was that they used props that nobody expected them to.

By pulling out a cigarette and lighter or a white pair of underwear, the audience can’t help but be gripped by what the speaker is about to do next. And that makes for a powerful speech opening.

6. Simon Sinek

Opening: “How do you explain when things don’t go as we assume? Or better, how do you explain when others are able to achieve things that seem to defy all of the assumptions?”

7. Julian Treasure

Opening: “The human voice. It’s the instrument we all play. It’s the most powerful sound in the world. Probably the only one that can start a war or say “I love you.” And yet many people have the experience that when they speak people don’t listen to them. Why is that? How can we speak powerfully to make change in the world?”

How to use questions to open a speech?

I use this method often. Starting off with a question is the simplest way to start your speech in a manner that immediately engages the audience.

But we should keep our questions compelling as opposed to something that is fairly obvious.

I’ve heard many speakers start their speeches with questions like “How many of us want to be successful?”

No one is going to say ‘no’ to that and frankly, I just feel silly raising my hand at such questions.

Simon Sinek and Jullian Treasure used questions in a manner that really made the audience think and make them curious to find out what the answer to that question is.

What Jullian Treasure did even better was the use of a few statements which built up to his question. This made the question even more compelling and set the theme for what the rest of his talk would be about.

So think of what question you can ask in your speech that will:

- Set the theme for the remainder of your speech

- Not be something that is fairly obvious

- Be compelling enough so that the audience will actually want to know what the answer to that question will be

8. Aaron Beverley

Opening: Long pause (after an absurdly long introduction of a 57-word speech title). “Be honest. You enjoyed that, didn’t you?”

How to use silence for speech openings?

The reason this speech opening stands out is because of the fact that the title itself is 57 words long. The audience was already hilariously intrigued by what was going to come next.

But what’s so gripping here is the way Aaron holds the crowd’s suspense by…doing nothing. For about 10 to 12 seconds he did nothing but stand and look at the audience. Everyone quietened down. He then broke this silence by a humorous remark that brought the audience laughing down again.

When going on to open your speech, besides focusing on building a killer opening sentence, how about just being silent?

It’s important to keep in mind that the point of having a strong opening is so that the audience’s attention is all on you and are intrigued enough to want to listen to the rest of your speech.

Silence is a great way to do that. When you get on the stage, just pause for a few seconds (about 3 to 5 seconds) and just look at the crowd. Let the audience and yourself settle in to the fact that the spotlight is now on you.

I can’t put my finger on it, but there is something about starting the speech off with a pure pause that just makes the beginning so much more powerful. It adds credibility to you as a speaker as well, making you look more comfortable and confident on stage.

If you want to know more about the power of pausing in public speaking , check out this post we wrote. It will give you a deeper insight into the importance of pausing and how you can harness it for your own speeches. You can also check out this video to know more about Pausing for Public Speaking:

9. Dan Pink

Opening: “I need to make a confession at the outset here. Little over 20 years ago, I did something that I regret. Something that I’m not particularly proud of. Something that in many ways I wish no one would ever know but that here I feel kind of obliged to reveal.”

10. Kelly McGonigal

Opening: “I have a confession to make. But first I want you to make a little confession to me.”

How to use a build-up to open your speech?

When there are so many amazing ways to start a speech and grip an audience from the outset, why would you ever choose to begin your speech with a ‘Good morning?’.

That’s what I love about build-ups. They set the mood for something awesome that’s about to come in that the audience will feel like they just have to know about.

Instead of starting a speech as it is, see if you can add some build-up to your beginning itself. For instance, in Kelly McGonigal’s speech, she could have started off with the question of stress itself (which she eventually moves on to in her speech). It’s not a bad way to start the speech.

But by adding the statement of “I have a confession to make” and then not revealing the confession for a little bit, the audience is gripped to know what she’s about to do next and find out what indeed is her confession.

11. Tim Urban

Opening: “So in college, I was a government major. Which means that I had to write a lot of papers. Now when a normal student writes a paper, they might spread the work out a little like this.”

12. Scott Dinsmore

Opening: “8 years ago, I got the worst career advice of my life.”

How to use storytelling as a speech opening?

“The most powerful person in the world is the storyteller.” Steve Jobs

Storytelling is the foundation of good speeches. Starting your speech with a story is a great way to grip the audience’s attention. It makes them yearn to want to know how the rest of the story is going to pan out.

Tim Urban starts off his speech with a story dating back to his college days. His use of slides is masterful and something we all can learn from. But while his story sounds simple, it does the job of intriguing the audience to want to know more.

As soon as I heard the opening lines, I thought to myself “If normal students write their paper in a certain manner, how does Tim write his papers?”

Combine such a simple yet intriguing opening with comedic slides, and you’ve got yourself a pretty gripping speech.

Scott Dismore’s statement has a similar impact. However, just a side note, Scott Dismore actually started his speech with “Wow, what an honour.”

I would advise to not start your talk with something such as that. It’s way too common and does not do the job an opening must, which is to grip your audience and set the tone for what’s coming.

13. Larry Smith

Opening: “I want to discuss with you this afternoon why you’re going to fail to have a great career.”

14. Jane McGonigal

Opening: “You will live 7.5 minutes longer than you would have otherwise, just because you watched this talk.”

How to use provocative statements to start your speech?

Making a provocative statement creates a keen desire among the audience to want to know more about what you have to say. It immediately brings everyone into attention.

Larry Smith did just that by making his opening statement surprising, lightly humorous, and above all – fearful. These elements lead to an opening statement which creates so much curiosity among the audience that they need to know how your speech pans out.

This one time, I remember seeing a speaker start a speech with, “Last week, my best friend committed suicide.” The entire crowd was gripped. Everyone could feel the tension in the room.

They were just waiting for the speaker to continue to know where this speech will go.

That’s what a hard-hitting statement does, it intrigues your audience so much that they can’t wait to hear more! Just a tip, if you do start off with a provocative, hard-hitting statement, make sure you pause for a moment after saying it.

Silence after an impactful statement will allow your message to really sink in with the audience.

Related article: 5 Ways to Grab Your Audience’s Attention When You’re Losing it!

15. Ramona J Smith

Opening: In a boxing stance, “Life would sometimes feel like a fight. The punches, jabs and hooks will come in the form of challenges, obstacles and failures. Yet if you stay in the ring and learn from those past fights, at the end of each round, you’ll be still standing.”

How to use your full body to grip the audience at the beginning of your speech?

In a talk, the audience is expecting you to do just that – talk. But when you enter the stage and start putting your full body into use in a way that the audience does not expect, it grabs their attention.

Body language is critical when it comes to public speaking. Hand gestures, stage movement, facial expressions are all things that need to be paid attention to while you’re speaking on stage. But that’s not I’m talking about here.

Here, I’m referring to a unique use of the body that grips the audience, like how Ramona did. By using her body to get into a boxing stance, imitating punches, jabs and hooks with her arms while talking – that’s what got the audience’s attention.

The reason I say this is so powerful is because if you take Ramona’s speech and remove the body usage from her opening, the entire magic of the opening falls flat.

While the content is definitely strong, without those movements, she would not have captured the audience’s attention as beautifully as she did with the use of her body.

So if you have a speech opening that seems slightly dull, see if you can add some body movement to it.

If your speech starts with a story of someone running, actually act out the running. If your speech starts with a story of someone reading, actually act out the reading.

It will make your speech opening that much more impactful.

Related article: 5 Body Language Tips to Command the Stage

Level up your public speaking in 15 minutes!

Get the exclusive Masterclass video delivered to your inbox to see immediate speaking results.

You have successfully joined our subscriber list.

Final Words

So there it is! 15 speech openings from some of my favourite speeches. Hopefully, these will act as a guide for you to create your own opening which is super impactful and sets you off on the path to becoming a powerful public speaker!

But remember, while a speech opening is super important, it’s just part of an overall structure.

If you’re serious about not just creating a great speech opening but to improve your public speaking at an overall level, I would highly recommend you to check out this course: Acumen Presents: Chris Anderson on Public Speaking on Udemy. Not only does it have specific lectures on starting and ending a speech, but it also offers an in-depth guide into all the nuances of public speaking.

Being the founder of TED Talks, Chris Anderson provides numerous examples of the best TED speakers to give us a very practical way of overcoming stage fear and delivering a speech that people will remember. His course has helped me personally and I would definitely recommend it to anyone looking to learn public speaking.

No one is ever “done” learning public speaking. It’s a continuous process and you can always get better. Keep learning, keep conquering and keep being awesome!

Lastly, if you want to know how you should NOT open your speech, we’ve got a video for you:

Enroll in our transformative 1:1 Coaching Program

Schedule a call with our expert communication coach to know if this program would be the right fit for you

High-Stakes Presentations: Strategies for Engaging and Influencing Senior Leaders

Crisis Leadership 101: Cultivating Empathy While Exercising Authority

Lost Voice? Here’s How to Recover Sore Throat and Speak Again

- [email protected]

- +91 98203 57888

Get our latest tips and tricks in your inbox always

Copyright © 2023 Frantically Speaking All rights reserved

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8 Effective Introductions and Powerful Conclusions

Learning objectives.

- Identify the functions of introductions and conclusions.

- Understand the key parts of an introduction and a conclusion.

- Explore techniques to create your own effective introductions and conclusions.

Introductions and conclusions can be challenging. One of the most common complaints novice public speakers have is that they simply don’t know how to start or end a speech. It may feel natural to start crafting a speech at the beginning, but it can be difficult to craft an introduction for something which doesn’t yet exist. Many times, creative and effective ideas for how to begin a speech will come to speakers as they go through the process of researching and organizing ideas. Similarly, a conclusion needs to be well considered and leave audience members with a sense of satisfaction.

In this chapter, we will explore why introductions and conclusions are important, and we will identify various ways speakers can create impactful beginnings and endings. There is not a “right” way to start or end a speech, but we can provide some helpful guidelines that will make your introductions and conclusions much easier for you as a speaker and more effective for your audience.

The Importance of an Introduction

The introduction of a speech is incredibly important because it needs to establish the topic and purpose, set up the reason your audience should listen to you and set a precedent for the rest of the speech. Imagine the first day of a semester long class. You will have a different perception of the course if the teacher is excited, creative and clear about what is to come then if the teacher recites to you what the class is about and is confused or disorganized about the rest of the semester. The same thing goes for a speech. The introduction is an important opportunity for the speaker to gain the interest and trust of the audience.

Overall, an effective introduction serves five functions. Let’s examine each of these.

Gain Audience Attention and Interest

The first major purpose of an introduction is to gain your audience’s attention and get them interested in what you have to say. While your audience may know you, this is your speeches’ first impression! One common incorrect assumption beginning speakers make that people will naturally listen because the speaker is speaking. While many audiences may be polite and not talk while you’re speaking, actually getting them to listen and care about what you are saying is a completely different challenge. Think to a time when you’ve tuned out a speaker because you were not interested in what they had to say or how they were saying it. However, I’m sure you can also think of a time someone engaged you in a topic you wouldn’t have thought was interesting, but because of how they presented it or their energy about the subject, you were fascinated. As the speaker, you have the ability to engage the audience right away.

State the Purpose of Your Speech

The second major function of an introduction is to reveal the purpose of your speech to your audience. Have you ever sat through a speech wondering what the basic point was? Have you ever come away after a speech and had no idea what the speaker was talking about? An introduction is critical for explaining the topic to the audience and justifying why they should care about it. The speaker needs to have an in-depth understanding of the specific focus of their topic and the goals they have for their speech. Robert Cavett, the founder of the National Speaker’s Association, used the analogy of a preacher giving a sermon when he noted, “When it’s foggy in the pulpit, it’s cloudy in the pews.” The specific purpose is the one idea you want your audience to remember when you are finished with your speech. Your specific purpose is the rudder that guides your research, organization, and development of main points. The more clearly focused your purpose is, the easier it will be both for you to develop your speech and your audience to understand your core point. To make sure you are developing a specific purpose, you should be able to complete the sentence: “I want my audience to understand…” Notice that your specific speech purpose is phrased in terms of expected audience responses, not in terms of your own perspective.

Establish Credibility

One of the most researched areas within the field of communication has been Aristotle’s concept of ethos or credibility. First, and foremost, the idea of credibility relates directly to audience perception. You may be the most competent, caring, and trustworthy speaker in the world on a given topic, but if your audience does not perceive you as credible, then your expertise and passion will not matter to them. As public speakers, we need to communicate to our audiences why we are credible speakers on a given topic. James C. McCroskey and Jason J. Teven have conducted extensive research on credibility and have determined that an individual’s credibility is composed of three factors: competence, trustworthiness, and caring/goodwill (McCroskey & Teven, 1999). Competence is the degree to which a speaker is perceived to be knowledgeable or expert in a given subject by an audience member.

The second factor of credibility noted by McCroskey and Teven is trustworthiness or the degree to which an audience member perceives a speaker as honest. Nothing will turn an audience against a speaker faster than if the audience believes the speaker is lying. When the audience does not perceive a speaker as trustworthy, the information coming out of the speaker’s mouth is automatically perceived as deceitful.

Finally, caring/goodwill is the last factor of credibility noted by McCroskey and Teven. Caring/goodwill refers to the degree to which an audience member perceives a speaker as caring about the audience member. As indicated by Wrench, McCroskey, and Richmond, “If a receiver does not believe that a source has the best intentions in mind for the receiver, the receiver will not see the source as credible. Simply put, we are going to listen to people who we think truly care for us and are looking out for our welfare” (Wrench, McCroskey & Richmond, 2008). As a speaker, then, you need to establish that your information is being presented because you care about your audience and are not just trying to manipulate them. We should note that research has indicated that caring/goodwill is the most important factor of credibility. This understanding means that if an audience believes that a speaker truly cares about the audience’s best interests, the audience may overlook some competence and trust issues.

Credibility relates directly to audience perception. You may be the most competent, caring, and trustworthy speaker in the world on a given topic, but if your audience does not perceive you as credible, then your expertise and passion will not matter to them.

Trustworthiness is the degree to which an audience member perceives a speaker as honest.

Caring/goodwill is the degree to which an audience member perceives a speaker as caring about the audience member.

Provide Reasons to Listen

The fourth major function of an introduction is to establish a connection between the speaker and the audience, and one of the most effective means of establishing a connection with your audience is to provide them with reasons why they should listen to your speech. The idea of establishing a connection is an extension of the notion of caring/goodwill. In the chapters on Language and Speech Delivery, we’ll spend a lot more time talking about how you can establish a good relationship with your audience. This relationship starts the moment you step to the front of the room to start speaking.

Instead of assuming the audience will make their own connections to your material, you should explicitly state how your information might be useful to your audience. Tell them directly how they might use your information themselves. It is not enough for you alone to be interested in your topic. You need to build a bridge to the audience by explicitly connecting your topic to their possible needs.

Preview Main Ideas

The last major function of an introduction is to preview the main ideas that your speech will discuss. A preview establishes the direction your speech will take. We sometimes call this process signposting because you’re establishing signs for audience members to look for while you’re speaking. In the most basic speech format, speakers generally have three to five major points they plan on making. During the preview, a speaker outlines what these points will be, which demonstrates to the audience that the speaker is organized.

A study by Baker found that individuals who were unorganized while speaking were perceived as less credible than those individuals who were organized (Baker, 1965). Having a solid preview of the information contained within one’s speech and then following that preview will help a speaker’s credibility. It also helps your audience keep track of where you are if they momentarily daydream or get distracted.

Putting Together a Strong Introduction

Now that we have an understanding of the functions of an introduction, let’s explore the details of putting one together. As with all aspects of a speech, these may change based on your audience, circumstance, and topic. But this will give you a basic understanding of the important parts of an intro, what they do, and how they work together.

Attention Getting Device

An attention-getter is the device a speaker uses at the beginning of a speech to capture an audience’s interest and make them interested in the speech’s topic. Typically, there are four things to consider in choosing a specific attention-getting device:

- Topic and purpose of the speech

- Appropriateness or relevance to the audience

First, when selecting an attention-getting device is considering your speech topic and purpose. Ideally, your attention-getting device should have a relevant connection to your speech. Imagine if a speaker pulled condoms out of his pocket, yelled “Free sex!” and threw the condoms at the audience. This act might gain everyone’s attention, but would probably not be a great way to begin a speech about the economy. Thinking about your topic because the interest you want to create needs to be specific to your subject. More specifically, you want to consider the basic purpose of your speech. When selecting an attention getter, you want to make sure that you select one that corresponds with your basic purpose. If your goal is to entertain an audience, starting a speech with a quotation about how many people are dying in Africa each day from malnutrition may not be the best way to get your audience’s attention. Remember, one of the goals of an introduction is to prepare your audience for your speech . If your attention-getter differs drastically in tone from the rest of your speech the disjointedness may cause your audience to become confused or tune you out completely.

Possible Attention Getters

These will help you start brainstorming ideas for how to begin your speech. While not a complete list, these are some of the most common forms of attention-getters:

- Reference to Current Events

- Historical Reference

- Startling Fact

- Rhetorical Question

- Hypothetical Situation

- Demonstration

- Personal Reference

- Reference to Audience

- Reference to Occasion

Second, when selecting an attention-getting device, you want to make sure you are being appropriate and relevant to your specific audience. Different audiences will have different backgrounds and knowledge, so you should keep your audience in mind when determining how to get their attention. For example, if you’re giving a speech on family units to a group of individuals over the age of sixty-five, starting your speech with a reference to the television show Gossip Girl may not be the best idea because the television show may not be relevant to that audience.

Finally, the last consideration involves the speech occasion. Different occasions will necessitate different tones or particular styles or manners of speaking. For example, giving a eulogy at a funeral will have a very different feel than a business presentation. This understanding doesn’t mean certain situations are always the same, but rather taking into account the details of your circumstances will help you craft an effective beginning to your speech. When selecting an attention-getter, you want to make sure that the attention-getter sets the tone for the speech and situation.

Tones are particular styles or manners of speaking determined by the speech’s occasion.

Link to Topic

The link to the topic occurs when a speaker demonstrates how an attention-getting device relates to the topic of a speech. This presentation of the relationship works to transition your audience from the attention getter to the larger issue you are discussing. Often the attention-getter and the link to the topic are very clear. But other times, there may need to be a more obvious connection between how you began your attention-getting device and the specific subject you are discussing. You may have an amazing attention-getter, but if you can’t connect it to the main topic and purpose of your speech, it will not be as effective.

Significance

Once you have linked an attention-getter to the topic of your speech, you need to explain to your audience why your topic is important and why they should care about what you have to say. Sometimes you can include the significance of your topic in the same sentence as your link to the topic, but other times you may need to spell out in one or two sentences why your specific topic is important to this audience.

Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a short, declarative sentence that states the purpose, intent, or main idea of a speech. A strong, clear thesis statement is very valuable within an introduction because it lays out the basic goal of the entire speech. We strongly believe that it is worthwhile to invest some time in framing and writing a good thesis statement. You may even want to write a version of your thesis statement before you even begin conducting research for your speech in order to guide you. While you may end up rewriting your thesis statement later, having a clear idea of your purpose, intent, or main idea before you start searching for research will help you focus on the most appropriate material.

Preview of Speech

The final part of an introduction contains a preview of the major points to be covered by your speech. I’m sure we’ve all seen signs that have three cities listed on them with the mileage to reach each city. This mileage sign is an indication of what is to come. A preview works the same way. A preview foreshadows what the main body points will be in the speech. For example, to preview a speech on bullying in the workplace, one could say, “To understand the nature of bullying in the modern workplace, I will first define what workplace bullying is and the types of bullying, I will then discuss the common characteristics of both workplace bullies and their targets, and lastly, I will explore some possible solutions to workplace bullying.” In this case, each of the phrases mentioned in the preview would be a single distinct point made in the speech itself. In other words, the first major body point in this speech would examine what workplace bullying is and the types of bullying; the second major body point in this speech would discuss the characteristics of both workplace bullies and their targets; and lastly, the third body point in this speech would explore some possible solutions to workplace bullying.

Putting it all together

The importance of introductions often leads speakers to work on them first, attending to every detail. While it is good to have some ideas and notes about the intro, specifically the thesis statement, it is often best to wait until the majority of the speech is crafted before really digging into the crafting of the introduction. This timeline may not seem intuitive, but remember, the intro is meant to introduce your speech and set up what is to come. It is difficult to introduce something that you haven’t made yet. This is why working on your main points first can help lead to an even stronger introduction.

Why Conclusions Matter

Willi Heidelbach – Puzzle2 – CC BY 2.0.

As public speaking professors and authors, we have seen many students give otherwise good speeches that seem to fall apart at the end. We’ve seen students end their three main points by saying things such as “OK, I’m done”; “Thank God that’s over!”; or “Thanks. Now what? Do I just sit down?” It’s understandable to feel relief at the end of a speech, but remember that as a speaker, your conclusion is the last chance you have to drive home your ideas. When a speaker opts to end the speech with an ineffective conclusion, or no conclusion at all, the speech loses the energy that’s been created, and the audience is left confused and disappointed. Instead of falling prey to emotional exhaustion, remind yourself to keep your energy up as you approach the end of your speech, and plan ahead so that your conclusion will be an effective one.

Of course, a good conclusion will not rescue a poorly prepared speech. Thinking again of the chapters in a novel, if one bypasses all the content in the middle, the ending often isn’t very meaningful or helpful. So to take advantage of the advice in this chapter, you need to keep in mind the importance of developing a speech with an effective introduction and an effective body. If you have these elements, you will have the foundation you need to be able to conclude effectively. Just as a good introduction helps bring an audience member into the world of your speech, and a good speech body holds the audience in that world, a good conclusion helps bring that audience member back to the reality outside of your speech.

In this section, we’re going to examine the functions fulfilled by the conclusion of a speech. A strong conclusion serves to signal the end of the speech and helps your listeners remember your speech.

Signals the End

The first thing a good conclusion can do is to signal the end of a speech. You may be thinking that showing an audience that you’re about to stop speaking is a “no brainer,” but many speakers don’t prepare their audience for the end. When a speaker just suddenly stops speaking, the audience is left confused and disappointed. Instead, we want to make sure that audiences are left knowledgeable and satisfied with our speeches. In the next section, we’ll explain in great detail about how to ensure that you signal the end of your speech in a manner that is both effective and powerful.

Aids Audience’s Memory of Your Speech

The second reason for a good conclusion stems out of some research reported by the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus back in 1885 in his book Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology (Ebbinghaus, 1885). Ebbinghaus proposed that humans remember information in a linear fashion, which he called the serial position effect. He found an individual’s ability to remember information in a list (e.g. a grocery list, a chores list, or a to-do list) depends on the location of an item on the list. Specifically, he found that items toward the top of the list and items toward the bottom of the list tended to have the highest recall rates. The serial position effect finds that information at the beginning of a list (primacy) and information at the end of the list (recency) are easier to recall than information in the middle of the list.

So what does this have to do with conclusions? A lot! Ray Ehrensberger wanted to test Ebbinghaus’ serial position effect in public speaking. Ehrensberger created an experiment that rearranged the ordering of a speech to determine the recall of information (Ehrensberger, 1945). Ehrensberger’s study reaffirmed the importance of primacy and recency when listening to speeches. In fact, Ehrensberger found that the information delivered during the conclusion (recency) had the highest level of recall overall.

Steps of a Conclusion

Matthew Culnane – Steps – CC BY-SA 2.0.

In the previous sections, we discussed the importance a conclusion has on a speech. In this section, we’re going to examine the three steps to building an effective conclusion.

Restatement of the Thesis

Restating a thesis statement is the first step to a powerful conclusion. As we explained earlier, a thesis statement is a short, declarative sentence that states the purpose, intent, or main idea of a speech. When we restate the thesis statement at the conclusion of our speech, we’re attempting to reemphasize what the overarching main idea of the speech has been. Suppose your thesis statement was, “I will analyze Barack Obama’s use of lyricism in his July 2008 speech, ‘A World That Stands as One.’” You could restate the thesis in this fashion at the conclusion of your speech: “In the past few minutes, I have analyzed Barack Obama’s use of lyricism in his July 2008 speech, ‘A World That Stands as One.’” Notice the shift in tense. The statement has gone from the future tense (this is what I will speak about) to the past tense (this is what I have spoken about). Restating the thesis in your conclusion reminds the audience of the main purpose or goal of your speech, helping them remember it better.

Review of Main Points

After restating the speech’s thesis, the second step in a powerful conclusion is to review the main points from your speech. One of the biggest differences between written and oral communication is the necessity of repetition in oral communication. When we preview our main points in the introduction, effectively discuss and make transitions to our main points during the body of the speech, and review the main points in the conclusion, we increase the likelihood that the audience will retain our main points after the speech is over.

In the introduction of a speech, we deliver a preview of our main body points, and in the conclusion, we deliver a review . Let’s look at a sample preview:

In order to understand the field of gender and communication, I will first differentiate between the terms biological sex and gender. I will then explain the history of gender research in communication. Lastly, I will examine a series of important findings related to gender and communication.

In this preview, we have three clear main points. Let’s see how we can review them at the conclusion of our speech:

Today, we have differentiated between the terms biological sex and gender, examined the history of gender research in communication, and analyzed a series of research findings on the topic.

In the past few minutes, I have explained the difference between the terms “biological sex” and “gender,” discussed the rise of gender research in the field of communication, and examined a series of groundbreaking studies in the field.

Notice that both of these conclusions review the main points initially set forth. Both variations are equally effective reviews of the main points, but you might like the linguistic turn of one over the other. Remember, while there is a lot of science to help us understand public speaking, there’s also a lot of art as well. You are always encouraged to choose the wording that you think will be most effective for your audience.

Concluding Device

The final part of a powerful conclusion is the concluding device. A concluding device is a final thought you want your audience members to have when you stop speaking. It also provides a definitive sense of closure to your speech. One of the authors of this text often makes an analogy between a gymnastics dismount and the concluding device in a speech. Just as a gymnast dismounting the parallel bars or balance beam wants to stick the landing and avoid taking two or three steps, a speaker wants to “stick” the ending of the presentation by ending with a concluding device instead of with, “Well, umm, I guess I’m done.” Miller observed that speakers tend to use one of ten concluding devices when ending a speech (Miller, 1946). The rest of this section is going to examine these ten concluding devices and one additional device that we have added.

Conclude with a Challenge

The first way that Miller found that some speakers end their speeches is with a challenge. A challenge is a call to engage in some activity that requires a special effort. In a speech on the necessity of fund-raising, a speaker could conclude by challenging the audience to raise 10 percent more than their original projections. In a speech on eating more vegetables, you could challenge your audience to increase their current intake of vegetables by two portions daily. In both of these challenges, audience members are being asked to go out of their way to do something different that involves effort on their part.

Conclude with a Quotation

A second way you can conclude a speech is by reciting a quotation relevant to the speech topic. When using a quotation, you need to think about whether your goal is to end on a persuasive note or an informative note. Some quotations will have a clear call to action, while other quotations summarize or provoke thought. For example, let’s say you are delivering an informative speech about dissident writers in the former Soviet Union. You could end by citing this quotation from Alexander Solzhenitsyn: “A great writer is, so to speak, a second government in his country. And for that reason, no regime has ever loved great writers” (Solzhenitsyn, 1964). Notice that this quotation underscores the idea of writers as dissidents, but it doesn’t ask listeners to put forth the effort to engage in any specific thought process or behavior. If, on the other hand, you were delivering a persuasive speech urging your audience to participate in a very risky political demonstration, you might use this quotation from Martin Luther King Jr.: “If a man hasn’t discovered something that he will die for, he isn’t fit to live” (King, 1963). In this case, the quotation leaves the audience with the message that great risks are worth taking, that they make our lives worthwhile, and that the right thing to do is to go ahead and take that great risk.

Conclude with a Summary

When a speaker ends with a summary, they are simply elongating the review of the main points. While this may not be the most exciting concluding device, it can be useful for information that was highly technical or complex or for speeches lasting longer than thirty minutes. Typically, for short speeches (like those in your class), this summary device should be avoided.

Conclude by Visualizing the Future

The purpose of a conclusion that refers to the future is to help your audience imagine the future you believe can occur. If you are giving a speech on the development of video games for learning, you could conclude by depicting the classroom of the future where video games are perceived as true learning tools and how those tools could be utilized. More often, speakers use visualization of the future to depict how society would be, or how individual listeners’ lives would be different if the speaker’s persuasive attempt worked. For example, if a speaker proposes that a solution to illiteracy is hiring more reading specialists in public schools, the speaker could ask her or his audience to imagine a world without illiteracy. In this use of visualization, the goal is to persuade people to adopt the speaker’s point of view. By showing that the speaker’s vision of the future is a positive one, the conclusion should help to persuade the audience to help create this future.

Conclude with an Appeal for Action

Probably the most common persuasive concluding device is the appeal for action or the call to action. In essence, the appeal for action occurs when a speaker asks their audience to engage in a specific behavior or change in thinking. When a speaker concludes by asking the audience “to do” or “to think” in a specific manner, the speaker wants to see an actual change. Whether the speaker appeals for people to eat more fruit, buy a car, vote for a candidate, oppose the death penalty, or sing more in the shower, the speaker is asking the audience to engage in action.

One specific type of appeal for action is the immediate call to action. Whereas some appeals ask for people to engage in behavior in the future, an immediate call to action asks people to engage in behavior right now. If a speaker wants to see a new traffic light placed at a dangerous intersection, he or she may conclude by asking all the audience members to sign a digital petition right then and there, using a computer the speaker has made available ( http://www.petitiononline.com ). Here are some more examples of immediate calls to action:

- In a speech on eating more vegetables, pass out raw veggies and dip at the conclusion of the speech.