Unit 1: What Is Philosophy?

LOGOS: Critical Thinking, Arguments, and Fallacies

Heather Wilburn, Ph.D

Critical Thinking:

With respect to critical thinking, it seems that everyone uses this phrase. Yet, there is a fear that this is becoming a buzz-word (i.e. a word or phrase you use because it’s popular or enticing in some way). Ultimately, this means that we may be using the phrase without a clear sense of what we even mean by it. So, here we are going to think about what this phrase might mean and look at some examples. As a former colleague of mine, Henry Imler, explains:

By critical thinking, we refer to thinking that is recursive in nature. Any time we encounter new information or new ideas, we double back and rethink our prior conclusions on the subject to see if any other conclusions are better suited. Critical thinking can be contrasted with Authoritarian thinking. This type of thinking seeks to preserve the original conclusion. Here, thinking and conclusions are policed, as to question the system is to threaten the system. And threats to the system demand a defensive response. Critical thinking is short-circuited in authoritarian systems so that the conclusions are conserved instead of being open for revision. [1]

A condition for being recursive is to be open and not arrogant. If we come to a point where we think we have a handle on what is True, we are no longer open to consider, discuss, or accept information that might challenge our Truth. One becomes closed off and rejects everything that is different or strange–out of sync with one’s own Truth. To be open and recursive entails a sense of thinking about your beliefs in a critical and reflective way, so that you have a chance to either strengthen your belief system or revise it if needed. I have been teaching philosophy and humanities classes for nearly 20 years; critical thinking is the single most important skill you can develop. In close but second place is communication, In my view, communication skills follow as a natural result of critical thinking because you are attempting to think through and articulate stronger and rationally justified views. At the risk of sounding cliche, education isn’t about instilling content; it is about learning how to think.

In your philosophy classes your own ideas and beliefs will very likely be challenged. This does not mean that you will be asked to abandon your beliefs, but it does mean that you might be asked to defend them. Additionally, your mind will probably be twisted and turned about, which can be an uncomfortable experience. Yet, if at all possible, you should cherish these experiences and allow them to help you grow as a thinker. To be challenged and perplexed is difficult; however, it is worthwhile because it compels deeper thinking and more significant levels of understanding. In turn, thinking itself can transform us not only in thought, but in our beliefs, and our actions. Hannah Arendt, a social and political philosopher that came to the United States in exile during WWII, relates the transformative elements of philosophical thinking to Socrates. She writes:

Socrates…who is commonly said to have believed in the teachability of virtue, seems to have held that talking and thinking about piety, justice, courage, and the rest were liable to make men more pious, more just, more courageous, even though they were not given definitions or “values” to direct their further conduct. [2]

Thinking and communication are transformative insofar as these activities have the potential to alter our perspectives and, thus, change our behavior. In fact, Arendt connects the ability to think critically and reflectively to morality. As she notes above, morality does not have to give a predetermined set of rules to affect our behavior. Instead, morality can also be related to the open and sometimes perplexing conversations we have with others (and ourselves) about moral issues and moral character traits. Theodor W. Adorno, another philosopher that came to the United States in exile during WWII, argues that autonomous thinking (i.e. thinking for oneself) is crucial if we want to prevent the occurrence of another event like Auschwitz, a concentration camp where over 1 million individuals died during the Holocaust. [3] To think autonomously entails reflective and critical thinking—a type of thinking rooted in philosophical activity and a type of thinking that questions and challenges social norms and the status quo. In this sense thinking is critical of what is, allowing us to think beyond what is and to think about what ought to be, or what ought not be. This is one of the transformative elements of philosophical activity and one that is useful in promoting justice and ethical living.

With respect to the meaning of education, the German philosopher Hegel uses the term bildung, which means education or upbringing, to indicate the differences between the traditional type of education that focuses on facts and memorization, and education as transformative. Allen Wood explains how Hegel uses the term bildung: it is “a process of self-transformation and an acquisition of the power to grasp and articulate the reasons for what one believes or knows.” [4] If we think back through all of our years of schooling, particularly those subject matters that involve the teacher passing on information that is to be memorized and repeated, most of us would be hard pressed to recall anything substantial. However, if the focus of education is on how to think and the development of skills include analyzing, synthesizing, and communicating ideas and problems, most of us will use those skills whether we are in the field of philosophy, politics, business, nursing, computer programming, or education. In this sense, philosophy can help you develop a strong foundational skill set that will be marketable for your individual paths. While philosophy is not the only subject that will foster these skills, its method is one that heavily focuses on the types of activities that will help you develop such skills.

Let’s turn to discuss arguments. Arguments consist of a set of statements, which are claims that something is or is not the case, or is either true or false. The conclusion of your argument is a statement that is being argued for, or the point of view being argued for. The other statements serve as evidence or support for your conclusion; we refer to these statements as premises. It’s important to keep in mind that a statement is either true or false, so questions, commands, or exclamations are not statements. If we are thinking critically we will not accept a statement as true or false without good reason(s), so our premises are important here. Keep in mind the idea that supporting statements are called premises and the statement that is being supported is called the conclusion. Here are a couple of examples:

Example 1: Capital punishment is morally justifiable since it restores some sense of

balance to victims or victims’ families.

Let’s break it down so it’s easier to see in what we might call a typical argument form:

Premise: Capital punishment restores some sense of balance to victims or victims’ families.

Conclusion: Capital punishment is morally justifiable.

Example 2 : Because innocent people are sometimes found guilty and potentially

executed, capital punishment is not morally justifiable.

Premise: Innocent people are sometimes found guilty and potentially executed.

Conclusion: Capital punishment is not morally justifiable.

It is worth noting the use of the terms “since” and “because” in these arguments. Terms or phrases like these often serve as signifiers that we are looking at evidence, or a premise.

Check out another example:

Example 3 : All human beings are mortal. Heather is a human being. Therefore,

Heather is mortal.

Premise 1: All human beings are mortal.

Premise 2: Heather is a human being.

Conclusion: Heather is mortal.

In this example, there are a couple of things worth noting: First, there can be more than one premise. In fact, you could have a rather complex argument with several premises. If you’ve written an argumentative paper you may have encountered arguments that are rather complex. Second, just as the arguments prior had signifiers to show that we are looking at evidence, this argument has a signifier (i.e. therefore) to demonstrate the argument’s conclusion.

So many arguments!!! Are they all equally good?

No, arguments are not equally good; there are many ways to make a faulty argument. In fact, there are a lot of different types of arguments and, to some extent, the type of argument can help us figure out if the argument is a good one. For a full elaboration of arguments, take a logic class! Here’s a brief version:

Deductive Arguments: in a deductive argument the conclusion necessarily follows the premises. Take argument Example 3 above. It is absolutely necessary that Heather is a mortal, if she is a human being and if mortality is a specific condition for being human. We know that all humans die, so that’s tight evidence. This argument would be a very good argument; it is valid (i.e the conclusion necessarily follows the premises) and it is sound (i.e. all the premises are true).

Inductive Arguments : in an inductive argument the conclusion likely (at best) follows the premises. Let’s have an example:

Example 4 : 98.9% of all TCC students like pizza. You are a TCC student. Thus, you like pizza.

Premise 1: 98.9% of all TCC students like pizza

Premise 2: You are a TCC student.

Conclusion: You like pizza. (*Thus is a conclusion indicator)

In this example, the conclusion doesn’t necessarily follow; it likely follows. But you might be part of that 1.1% for whatever reason. Inductive arguments are good arguments if they are strong. So, instead of saying an inductive argument is valid, we say it is strong. You can also use the term sound to describe the truth of the premises, if they are true. Let’s suppose they are true and you absolutely love Hideaway pizza. Let’s also assume you are a TCC student. So, the argument is really strong and it is sound.

There are many types of inductive argument, including: causal arguments, arguments based on probabilities or statistics, arguments that are supported by analogies, and arguments that are based on some type of authority figure. So, when you encounter an argument based on one of these types, think about how strong the argument is. If you want to see examples of the different types, a web search (or a logic class!) will get you where you need to go.

Some arguments are faulty, not necessarily because of the truth or falsity of the premises, but because they rely on psychological and emotional ploys. These are bad arguments because people shouldn’t accept your conclusion if you are using scare tactics or distracting and manipulating reasoning. Arguments that have this issue are called fallacies. There are a lot of fallacies, so, again, if you want to know more a web search will be useful. We are going to look at several that seem to be the most relevant for our day-to-day experiences.

- Inappropriate Appeal to Authority : We are definitely going to use authority figures in our lives (e.g. doctors, lawyers, mechanics, financial advisors, etc.), but we need to make sure that the authority figure is a reliable one.

Things to look for here might include: reputation in the field, not holding widely controversial views, experience, education, and the like. So, if we take an authority figure’s word and they’re not legit, we’ve committed the fallacy of appeal to authority.

Example 5 : I think I am going to take my investments to Voya. After all, Steven Adams advocates for Voya in an advertisement I recently saw.

If we look at the criteria for evaluating arguments that appeal to authority figures, it is pretty easy to see that Adams is not an expert in the finance field. Thus, this is an inappropropriate appeal to authority.

- Slippery Slope Arguments : Slippery slope arguments are found everywhere it seems. The essential characteristic of a slippery slope argument is that it uses problematic premises to argue that doing ‘x’ will ultimately lead to other actions that are extreme, unlikely, and disastrous. You can think of this type of argument as a faulty chain of events or domino effect type of argument.

Example 6 : If you don’t study for your philosophy exam you will not do well on the exam. This will lead to you failing the class. The next thing you know you will have lost your scholarship, dropped out of school, and will be living on the streets without any chance of getting a job.

While you should certainly study for your philosophy exam, if you don’t it is unlikely that this will lead to your full economic demise.

One challenge to evaluating slippery slope arguments is that they are predictions, so we cannot be certain about what will or will not actually happen. But this chain of events type of argument should be assessed in terms of whether the outcome will likely follow if action ‘x” is pursued.

- Faulty Analogy : We often make arguments based on analogy and these can be good arguments. But we often use faulty reasoning with analogies and this is what we want to learn how to avoid.

When evaluating an argument that is based on an analogy here are a few things to keep in mind: you want to look at the relevant similarities and the relevant differences between the things that are being compared. As a general rule, if there are more differences than similarities the argument is likely weak.

Example 7 : Alcohol is legal. Therefore, we should legalize marijuana too.

So, the first step here is to identify the two things being compared, which are alcohol and marijuana. Next, note relevant similarities and differences. These might include effects on health, community safety, economic factors, criminal justice factors, and the like.

This is probably not the best argument in support for marijuana legalization. It would seem that one could just as easily conclude that since marijuana is illegal, alcohol should be too. In fact, one might find that alcohol is an often abused and highly problematic drug for many people, so it is too risky to legalize marijuana if it is similar to alcohol.

- Appeal to Emotion : Arguments should be based on reason and evidence, not emotional tactics. When we use an emotional tactic, we are essentially trying to manipulate someone into accepting our position by evoking pity or fear, when our positions should actually be backed by reasonable and justifiable evidence.

Example 8 : Officer please don’t give me a speeding ticket. My girlfriend broke up with me last night, my alarm didn’t go off this morning, and I’m late for class.

While this is a really horrible start to one’s day, being broken up with and an alarm malfunctioning is not a justifiable reason for speeding.

Example 9 : Professor, I’d like you to remember that my mother is a dean here at TCC. I’m sure that she will be very disappointed if I don’t receive an A in your class.

This is a scare tactic and is not a good way to make an argument. Scare tactics can come in the form of psychological or physical threats; both forms are to be avoided.

- Appeal to Ignorance : This fallacy occurs when our argument relies on lack of evidence when evidence is actually needed to support a position.

Example 10 : No one has proven that sasquatch doesn’t exist; therefore it does exist.

Example 11 : No one has proven God exists; therefore God doesn’t exist.

The key here is that lack of evidence against something cannot be an argument for something. Lack of evidence can only show that we are ignorant of the facts.

- Straw Man : A straw man argument is a specific type of argument that is intended to weaken an opponent’s position so that it is easier to refute. So, we create a weaker version of the original argument (i.e. a straw man argument), so when we present it everyone will agree with us and denounce the original position.

Example 12 : Women are crazy arguing for equal treatment. No one wants women hanging around men’s locker rooms or saunas.

This is a misrepresentation of arguments for equal treatment. Women (and others arguing for equal treatment) are not trying to obtain equal access to men’s locker rooms or saunas.

The best way to avoid this fallacy is to make sure that you are not oversimplifying or misrepresenting others’ positions. Even if we don’t agree with a position, we want to make the strongest case against it and this can only be accomplished if we can refute the actual argument, not a weakened version of it. So, let’s all bring the strongest arguments we have to the table!

- Red Herring : A red herring is a distraction or a change in subject matter. Sometimes this is subtle, but if you find yourself feeling lost in the argument, take a close look and make sure there is not an attempt to distract you.

Example 13 : Can you believe that so many people are concerned with global warming? The real threat to our country is terrorism.

It could be the case that both global warming and terrorism are concerns for us. But the red herring fallacy is committed when someone tries to distract you from the argument at hand by bringing up another issue or side-stepping a question. Politicians are masters at this, by the way.

- Appeal to the Person : This fallacy is also referred to as the ad hominem fallacy. We commit this fallacy when we dismiss someone’s argument or position by attacking them instead of refuting the premises or support for their argument.

Example 14 : I am not going to listen to what Professor ‘X’ has to say about the history of religion. He told one of his previous classes he wasn’t religious.

The problem here is that the student is dismissing course material based on the professor’s religious views and not evaluating the course content on its own ground.

To avoid this fallacy, make sure that you target the argument or their claims and not the person making the argument in your rebuttal.

- Hasty Generalization : We make and use generalizations on a regular basis and in all types of decisions. We rely on generalizations when trying to decide which schools to apply to, which phone is the best for us, which neighborhood we want to live in, what type of job we want, and so on. Generalizations can be strong and reliable, but they can also be fallacious. There are three main ways in which a generalization can commit a fallacy: your sample size is too small, your sample size is not representative of the group you are making a generalization about, or your data could be outdated.

Example 15 : I had horrible customer service at the last Starbucks I was at. It is clear that Starbucks employees do not care about their customers. I will never visit another Starbucks again.

The problem with this generalization is that the claim made about all Starbucks is based on one experience. While it is tempting to not spend your money where people are rude to their customers, this is only one employee and presumably doesn’t reflect all employees or the company as a whole. So, to make this a stronger generalization we would want to have a larger sample size (multiple horrible experiences) to support the claim. Let’s look at a second hasty generalization:

Example 16 : I had horrible customer service at the Starbucks on 81st street. It is clear that Starbucks employees do not care about their customers. I will never visit another Starbucks again.

The problem with this generalization mirrors the previous problem in that the claim is based on only one experience. But there’s an additional issue here as well, which is that the claim is based off of an experience at one location. To make a claim about the whole company, our sample group needs to be larger than one and it needs to come from a variety of locations.

- Begging the Question : An argument begs the question when the argument’s premises assume the conclusion, instead of providing support for the conclusion. One common form of begging the question is referred to as circular reasoning.

Example 17 : Of course, everyone wants to see the new Marvel movie is because it is the most popular movie right now!

The conclusion here is that everyone wants to see the new Marvel movie, but the premise simply assumes that is the case by claiming it is the most popular movie. Remember the premise should give reasons for the conclusion, not merely assume it to be true.

- Equivocation : In the English language there are many words that have different meanings (e.g. bank, good, right, steal, etc.). When we use the same word but shift the meaning without explaining this move to your audience, we equivocate the word and this is a fallacy. So, if you must use the same word more than once and with more than one meaning you need to explain that you’re shifting the meaning you intend. Although, most of the time it is just easier to use a different word.

Example 18 : Yes, philosophy helps people argue better, but should we really encourage people to argue? There is enough hostility in the world.

Here, argue is used in two different senses. The meaning of the first refers to the philosophical meaning of argument (i.e. premises and a conclusion), whereas the second sense is in line with the common use of argument (i.e. yelling between two or more people, etc.).

- Henry Imler, ed., Phronesis An Ethics Primer with Readings, (2018). 7-8. ↵

- Arendt, Hannah, “Thinking and Moral Considerations,” Social Research, 38:3 (1971: Autumn): 431. ↵

- Theodor W. Adorno, “Education After Auschwitz,” in Can One Live After Auschwitz, ed. by Rolf Tiedemann, trans. by Rodney Livingstone (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003): 23. ↵

- Allen W. Wood, “Hegel on Education,” in Philosophers on Education: New Historical Perspectives, ed. Amelie O. Rorty (London: Routledge 1998): 302. ↵

LOGOS: Critical Thinking, Arguments, and Fallacies Copyright © 2020 by Heather Wilburn, Ph.D is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

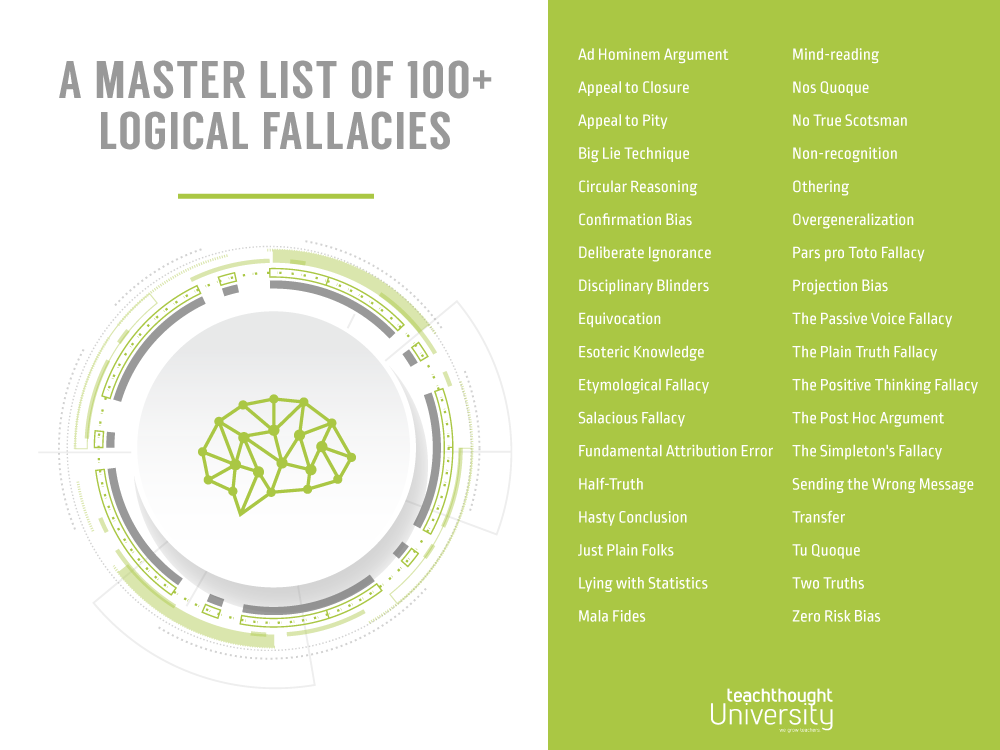

147 Logical Fallacies: A Master List With Examples

Logical fallacies are irrational arguments made through faulty reasoning common enough to be named for its respective logical failure.

A Complete Logical Fallacies List With Examples For Critical Thinking

contributed by Owen M. Wilson , University of Texas El Paso

A logical fallacy is an irrational argument made through faulty reasoning common enough to be named for the nature of its respective logical failure.

The A Priori Argument

Also: Rationalization; Dogmatism, Proof Texting

A corrupt argument from logos, starting with a given, pre-set belief, dogma, doctrine, scripture verse, ‘fact’ or conclusion and then searching for any reasonable or reasonable-sounding argument to rationalize, defend or justify it. Certain ideologues and religious fundamentalists are proud to use this fallacy as their primary method of ‘reasoning’ and some are even honest enough to say so.

Example: Since we know there is no such thing as ‘evolution,’ a prime duty of believers is to look for ways to explain away growing evidence, such as is found in DNA, that might suggest otherwise.

The opposite of this fallacy is the Taboo.

See also the Argument from Ignorance.

See also A Comprehensive List Of 180 Cognitive Biases And Heuristics

Also: The Con Artist’s Fallacy; The Dacoit’s Fallacy; Shearing the Sheeple; Profiteering; ‘Vulture Capitalism,’ ‘Wealth is a disease, and I am the cure.’

A corrupt argument from ethos, arguing that because someone is intellectually slower, physically or emotionally less capable, less ambitious, less aggressive, older or less healthy (or simply more trusting or less lucky) than others, s/he ‘naturally’ deserves less in life and may be freely victimized by those who are luckier, quicker, younger, stronger, healthier, greedier, more powerful, less moral or more gifted (or who simply have more immediate felt need for money, often involving some form of addiction). This fallacy is a ‘softer’ argumentum ad baculum. When challenged, those who practice this fallacy seem to most often shrug their shoulders and mumble ‘Life is ruff and you gotta be tuff [ sic ],’ ‘You gotta do what you gotta do to get ahead in this world,’ ‘It’s no skin off my nose,’ ‘That’s free enterprise,’ ‘That’s the way life is!’ or similar.

Actions have Consequences

The contemporary fallacy of a person in power falsely describing an imposed punishment or penalty as a ‘consequence’ of another’s negative act.

Example: The consequences of your misbehavior could include suspension or expulsion.’

A corrupt argument from ethos, arrogating to oneself or to one’s rules or laws an ethos of cosmic inevitability, i.e., the ethos of God, Fate, Karma, Destiny or Reality Itself. Illness or food poisoning is likely ‘consequences’ of eating spoiled food, while being ‘grounded’ is a punishment for , not a ‘consequence,’ of childhood misbehavior. Freezing to death is a natural ‘consequence’ of going out naked in subzero weather but going to prison is a punishment for bank robbery, not a natural, inevitable or unavoidable ‘consequence,’ of robbing a bank. Not to be confused with the Argument from Consequences, which is quite different.

An opposite fallacy is that of Moral Licensing.

See also Blaming the Victim.

The Ad Hominem Argument

Also: ‘Personal attack,’ ‘Poisoning the well’

The fallacy of attempting to refute an argument by attacking the opposition’s intelligence, morals, education, professional qualifications, personal character or reputation, using a corrupted negative argument from ethos. E.g., ‘That so-called judge;’ or ‘He’s so evil that you can’t believe anything he says.’ Another obverse of Ad Hominem is the Token Endorsement Fallacy, where, in the words of scholar Lara Bhasin, ‘Individual A has been accused of anti-Semitism, but Individual B is Jewish and says Individual A is not anti-Semitic, and the implication, of course, is that we can believe Individual B because, being Jewish, he has special knowledge of anti-Semitism. Or, a presidential candidate is accused of anti-Muslim bigotry, but someone finds a testimony from a Muslim who voted for said candidate, and this is trotted out as evidence against the candidate’s bigotry.’ The same fallacy would apply to a sports team offensively named after a marginalized ethnic group, but which has obtained the endorsement (freely given or paid) of some member, traditional leader or tribal council of that marginalized group so that the otherwise offensive team name and logo magically become ‘okay’ and nonracist.

The opposite of this is the ‘Star Power’ fallacy.

See also ‘Guilt by Association.’

See also 16 Characteristics Of A Critical Thinking Classroom

The Affective Fallacy

Also: The Romantic Fallacy; Emotion over Reflection; ‘Follow Your Heart’

An extremely common modern fallacy of Pathos, that one’s emotions, urges or ‘feelings’ are innate and in every case self-validating, autonomous, and above any human intent or act of will (one’s own or others’), and are thus immune to challenge or criticism. (In fact, researchers now [2017] have robust scientific evidence that emotions are actually cognitive and not innate. ) In this fallacy one argues, ‘I feel it, so it must be true. My feelings are valid, so you have no right to criticize what I say or do, or how I say or do it.’ This latter is also a fallacy of stasis, confusing a respectful and reasoned response or refutation with personal invalidation, disrespect, prejudice, bigotry, sexism, homophobia, or hostility. A grossly sexist form of the Affective Fallacy is the well-known crude fallacy that the phallus ‘Has no conscience’ (also, ‘A man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do;’ ‘Thinking with your other head.’), i.e., since (male) sexuality is self-validating and beyond voluntary control what one does with it cannot be controlled either and such actions are not open to criticism, an assertion eagerly embraced and extended beyond the male gender in certain reifications of ‘Desire’ in contemporary academic theory.

See also, Playing on Emotion. Opposite to this fallacy is the Chosen Emotion Fallacy (thanks to scholar Marc Lawson for identifying this fallacy), in which one falsely claims complete, or at least reliable prior voluntary control over one’s own autonomic, ‘gut level’ affective reactions. Closely related if not identical to this last is the ancient fallacy of Angelism, falsely claiming that one is capable of ‘objective’ reasoning and judgment without emotion, claiming for oneself a viewpoint of Olympian ‘disinterested objectivity’ or pretending to place oneself far above all personal feelings, temptations or bias.

See also, Mortification.

Alphabet Soup

A corrupt modern implicit fallacy from ethos in which a person inappropriately overuses acronyms, abbreviations, form numbers and arcane insider ‘shop talk’ primarily to prove to an audience that s/he ‘speaks their language’ and is ‘one of them’ and to shut out, confuse or impress outsiders. E.g., ‘It’s not uncommon for a K-12 with ASD to be both GT and LD;’ ‘I had a twenty-minute DX Q-so on 15 with a Zed-S1 and a couple of LU2’s even though the QR-Nancy was 10 over S9;’ or ‘I hope I’ll keep on seeing my BAQ on my LES until the day I get my DD214.’ See also, Name Calling. This fallacy has recently become common in media pharmaceutical advertising in the United States, where ‘Alphabet Soup’ is used to create false identification with and to exploit patient groups suffering from specific illnesses or conditions, e.g., ‘If you have DPC with associated ZL you can keep your B2D under control with Luglugmena®. Ask your doctor today about Luglugmena® Helium Tetracarbide lozenges to control symptoms of ZL and to keep your B2D under that crucial 7.62 threshold. Side effects of Luglugmena® may include K4 Syndrome, which may lead to lycanthropic bicephaly, BMJ and occasionally, death. Do not take Luglugmena® if you are allergic to dogbite or have type D Flinder’s Garbosis…’

Alternative Truth

Also: Alt Facts; Counterknowledge; Disinformation; Information Pollution

A newly-famous contemporary fallacy of logos rooted in postmodernism, denying the resilience of facts or truth as such. Writer Hannah Arendt, in her The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) warned that ‘The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the dedicated communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction, true and false, no longer exists.’ Journalist Leslie Grass (2017) writes in her Blog Reachoutrecovery.com, ‘Is there someone in your life who insists things happened that didn’t happen, or has a completely different version of events in which you have the facts? It’s a form of mind control and is very common among families dealing with substance and behavior problems.’ She suggests that such ‘Alternate Facts’ work to ‘put you off balance,’ ‘control the story,’ and ‘make you think you’re crazy,’ and she notes that ‘presenting alternate facts is the hallmark of untrustworthy people.’

The Alternative Truth fallacy is related to the Big Lie Technique.

See also Gaslighting, Blind Loyalty, The Big Brain/Little Brain Fallacy, and Two Truths

The Appeal to Closure :

The contemporary fallacy that an argument, standpoint, action, or conclusion no matter how questionable must be accepted as final or else the point will remain unsettled, which is unthinkable because those affected will be denied ‘closure.’ This fallacy falsely reifies a specialized term (closure) from Gestalt Psychology while refusing to recognize the undeniable truth that some points will indeed remain open and unsettled, perhaps forever. E.g., ‘Society would be protected, real punishment would be inflicted, crime would be deterred and justice served if we sentenced you to life without parole, but we need to execute you in order to provide some closure.’ See also, Argument from Ignorance, and Argument from Consequences.

The opposite of this fallacy is the Paralysis of Analysis.

The Appeal to Heaven

Also: Argumentum ad Coelum, Deus Vult, Gott mit Uns, Manifest Destiny, American Exceptionalism, or the Special Covenant

An ancient, extremely dangerous fallacy (a deluded argument from ethos) that of claiming to know the mind of God (or History, or a higher power), who has allegedly ordered or anointed, supports or approves of one’s own country, standpoint or actions so no further justification is required and no serious challenge is possible. (E.g., ‘God ordered me to kill my children,’ or ‘We need to take away your land, since God [or Scripture, or Manifest Destiny, or Fate, or Heaven] has given it to us as our own.’) A private individual who seriously asserts this fallacy risks ending up in a psychiatric ward, but groups or nations who do it are far too often taken seriously. Practiced by those who will not or cannot tell God’s will from their own, this vicious (and blasphemous) fallacy has been the cause of endless bloodshed over history. See also, Moral Superiority, and Magical Thinking. Also applies to deluded negative Appeals to Heaven, e.g., ‘You say that famine and ecological collapse due to climate change are real dangers during the coming century, but I know God wouldn’t ever let that happen to us!’

The opposite of the Appeal to Heaven is the Job’s Comforter fallacy.

The Appeal to Nature

Also: Biologizing; The Green Fallacy

The contemporary romantic fallacy of ethos (that of ‘Mother Nature’) that if something is ‘natural’ it has to be good, healthy and beneficial. E.g., ‘Our premium herb tea is lovingly brewed from the finest freshly-picked and delicately dried natural T. Radicans leaves. Those who dismiss it as mere ‘Poison Ivy’ don’t understand that it’s 100% organic, with no additives, GMO’s or artificial ingredients It’s time to Go Green and lay back in Mother’s arms.’ One who employs or falls for this fallacy forgets the old truism that left to itself, nature is indeed ‘red in tooth and claw.’ This fallacy also applies to arguments alleging that something is ‘unnatural,’ or ‘against nature’ and thus evil ( The Argument from Natural Law ) e.g. ‘Homosexuality should be outlawed because it’s against nature,’ arrogating to oneself the authority to define what is ‘natural’ and what is unnatural or perverted. E.g., during the American Revolution British sources widely condemned rebellion against King George III as ‘unnatural,’ and American revolutionaries as ‘perverts,’ because the Divine Right of Kings represented Natural Law, and according to 1 Samuel 15:23 in the Bible, rebellion is like unto witchcraft.

The Appeal to Pity

Also: ‘Argumentum ad Miserecordiam’

The fallacy of urging an audience to ‘root for the underdog’ regardless of the issues at hand. A classic example is, ‘Those poor, cute little squeaky mice are being gobbled up by mean, nasty cats ten times their size!’ A contemporary example might be America’s uncritical popular support for the Arab Spring movement of 2010-2012 in which The People (‘The underdogs’) were seen to be heroically overthrowing cruel dictatorships, a movement that has resulted in retrospect in chaos, impoverishment, anarchy, mass suffering, civil war, the regional collapse of civilization and rise of extremism, and the largest refugee crisis since World War II. A corrupt argument from pathos. See also, Playing to Emotions. The opposite of the Appeal to Pity is the Appeal to Rigor, an argument (often based on machismo or on manipulating an audience’s fear) based on mercilessness. E.g., ‘I’m a real man, not like those bleeding hearts, and I’ll be tough on [fill in the name of the enemy or bogeyman of the hour].’ In academia this latter fallacy applies to politically-motivated or elitist calls for ‘Academic Rigor,’ and rage against university developmental/remedial classes, open admissions, ‘dumbing down’ and ‘grade inflation.’

The Appeal to Tradition

Also: Conservative Bias; Back in Those Good Times, ‘The Good Old Days’

The ancient fallacy that a standpoint, situation, or action is right, proper, and correct simply because it has ‘always’ been that way, because people have ‘always’ thought that way, or because it was that way long ago (most often meaning in the audience members’ youth or childhood, not before) and still continues to serve one particular group very well. A corrupted argument from ethos (that of past generations). E.g., ‘In America, women have always been paid less, so let’s not mess with long-standing tradition.’ See also Argument from Inertia, and Default Bias. The opposite of this fallacy is The Appeal to Novelty (also, ‘Pro-Innovation bias,’ ‘Recency Bias,’ and ‘The Bad Old Days;’ The Early Adopter’s Fallacy), e.g., ‘It’s NEW, and [therefore it must be] improved!’ or ‘This is the very latest discovery–it has to be better.’

Appeasement

Also: ‘Assertiveness,’ ‘The squeaky wheel gets the grease;’ ‘I know my rights!’

This fallacy, most often popularly connected to the shameful pre-World War II appeasement of Hitler, is in fact still commonly practiced in public agencies, education and retail business today, e.g. ‘Customers are always right, even when they’re wrong. Don’t argue with them, just give’em what they want so they’ll shut up and go away, and not make a stink–it’s cheaper and easier than a lawsuit.’ Widespread unchallenged acceptance of this fallacy encourages offensive, uncivil public behavior and sometimes the development of a coarse subculture of obnoxious, ‘assertive’ manipulators who, like ‘spoiled’ children, leverage their knowledge of how to figuratively (or sometimes even literally!) ‘make a stink’ into a primary coping skill in order to get what they want when they want it. The works of the late Community Organizing guru Saul Alinsky suggest practical, nonviolent ways for groups to harness the power of this fallacy to promote social change, for good or for evil.

See also Bribery.

The Argument from Consequences

Also: Outcome Bias

The major fallacy of logos, arguing that something cannot be true because if it were the consequences or outcome would be unacceptable.

Example: Global climate change cannot be caused by human burning of fossil fuels, because if it were, switching to non-polluting energy sources would bankrupt American industry,’ or ‘Doctor, that’s wrong! I can’t have terminal cancer, because if I did that’d mean that I won’t live to see my kids get married!’

Not to be confused with Actions have Consequences.

The Argument from Ignorance

Also: Argumentum ad Ignorantiam

The fallacy is that since we don’t know (or can never know, or cannot prove) whether a claim is true or false, it must be false, or it must be true. E.g., ‘Scientists are never going to be able to positively prove their crazy theory that humans evolved from other creatures because we weren’t there to see it! So, that proves the Genesis six-day creation account is literally true as written!’ This fallacy includes Attacking the Evidence (also, ‘Whataboutism’; The Missing Link fallacy), e.g. ‘Some or all of your key evidence is missing, incomplete, or even faked! What about that? That proves you’re wrong and I’m right!’ This fallacy usually includes fallacious ‘Either-Or Reasoning’ as well: E.g., ‘The vet can’t find any reasonable explanation for why my dog died. See! See! That proves that you poisoned him! There’s no other logical explanation!’ A corrupted argument from logos, and a fallacy commonly found in American political, judicial and forensic reasoning. The recently famous ‘Flying Spaghetti Monster’ meme is a contemporary refutation of this fallacy–simply because we cannot conclusively disprove the existence of such an absurd entity does not argue for its existence.

See also A Priori Argument, Appeal to Closure, The Simpleton’s Fallacy, and Argumentum ex Silentio.

The Argument from Incredulity

The popular fallacy of doubting or rejecting a novel claim or argument out of hand simply because it appears superficially ‘incredible,’ ‘insane’ or ‘crazy,’ or because it goes against one’s own personal beliefs, prior experience or ideology. This cynical fallacy falsely elevates the saying popularized by Carl Sagan, that ‘Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof,’ to an absolute law of logic. See also Hoyle’s Fallacy. The common, popular-level form of this fallacy is dismissing surprising, extraordinary or unfamiliar arguments and evidence with a wave of the hand, a shake of the head, (saying) ‘that’s crazy!’

The Argument from Inertia

Also: ‘Stay the Course’

The fallacy that it is necessary to continue on a mistaken course of action regardless of pain and sacrifice involved and even after discovering it is mistaken, because changing course would mean admitting that one’s decision (or one’s leader, or one’s country, or one’s faith) was wrong, and all one’s effort, expense, sacrifice, and even bloodshed was for nothing, and that’s unthinkable. A variety of the Argument from Consequences, E for Effort, or the Appeal to Tradition. See also ‘Throwing Good Money After Bad.’

The Argument from Motives

Also Questioning Motives

The fallacy of declaring a standpoint or argument invalid solely because of the evil, corrupt or questionable motives of the one making the claim. E.g., ‘Bin Laden wanted us to withdraw from Afghanistan, so we have to keep up the fight!’ Even evil people with the most corrupt motives sometimes say the truth (and even good people with the highest and purest motives are often wrong or mistaken). A variety of the Ad Hominem argument. The opposite side of this fallacy is falsely justifying or excusing evil or vicious actions because of the perpetrator’s apparent purity of motives or lack of malice. (E.g., ‘Sure, she may have beaten her children bloody now and again but she was a highly educated, ambitious professional woman at the end of her rope, deprived of adult conversation and stuck between four walls for years on end with a bunch of screaming, fighting brats, doing the best she could with what little she had. How can you stand there and accuse her of child abuse?’)

See also Moral Licensing.

Argumentum ad Baculum

Also: Argument from the Club,’ ‘Argumentum ad Baculam,’ ‘Argument from Strength,’ ‘Muscular Leadership,’ ‘Non-negotiable Demands,’ ‘Hard Power,’ Bullying, The Power-Play, Fascism, Resolution by Force of Arms, Shock, and Awe.

The fallacy of ‘persuasion’ or ‘proving one is right’ by force, violence, brutality, terrorism, superior strength, raw military might, or threats of violence. E.g., ‘Gimmee your wallet or I’ll knock your head off!’ or ‘We have the perfect right to take your land, since we have the big guns and you don’t.’ Also applies to indirect forms of threat. E.g., ‘Give up your foolish pride, kneel down and accept our religion today if you don’t want to burn in hell forever and ever!’ A mainly discursive Argumentum ad Baculum is that of forcibly silencing opponents, ruling them ‘out of order,’ blocking, censoring, or jamming their message, or simply speaking over them or/speaking more loudly than they do, this last a tactic particularly attributed to men in mixed-gender discussions.

Argumentum ad Mysteriam

ALSO: ‘Argument from Mystery;’ also Mystagogy.

A darkened chamber, incense, chanting or drumming, bowing and kneeling, special robes or headgear, holy rituals, and massed voices reciting sacred mysteries in an unknown tongue have a quasi-hypnotic effect and can often persuade more strongly than any logical argument. The Puritan Reformation was in large part a rejection of this fallacy. When used knowingly and deliberately this fallacy is particularly vicious and accounts for some of the fearsome persuasive power of cults. An example of an Argumentum ad Mysteriam is the ‘ Long Ago and Far Away ‘ fallacy, the fact that facts, evidence, practices or arguments from ancient times, distant lands and/or ‘exotic’ cultures seem to acquire a special gravitas or ethos simply because of their antiquity, language or origin, e.g., publicly chanting Holy Scriptures in their original (most often incomprehensible) ancient languages, preferring the Greek, Latin, Assyrian or Old Slavonic Christian Liturgies over their vernacular versions, or using classic or newly invented Greek and Latin names for fallacies in order to support their validity.

See also, Esoteric Knowledge. An obverse of the Argumentum ad Mysteriam is the Standard Version Fallacy.

Argumentum ex Silentio

Also: Argument from Silence

The fallacy that if available sources remain silent or current knowledge and evidence can prove nothing about a given subject or question this fact in itself proves the truth of one’s claim. E.g., ‘Science can tell us nothing about God. That proves God doesn’t exist.’ Or ‘Science admits it can tell us nothing about God, so you can’t deny that God exists!’ Often misused in the American justice system, where, contrary to the 5th Amendment and the legal presumption of innocence until proven guilty, remaining silent or ‘taking the Fifth’ is often falsely portrayed as proof of guilt. E.g., ‘Mr. Hixon can offer no alibi for his whereabouts the evening of January 15th. This proves that he was in fact in room 331 at the Smuggler’s Inn, murdering his wife with a hatchet!’ In today’s America, choosing to remain silent in the face of a police officer’s questions can make one guilty enough to be arrested or even shot.

See also, Argument from Ignorance.

Availability Bias

Also: Attention Bias, Anchoring Bias

A fallacy of logos stemming from the natural tendency to give undue attention and importance to information that is immediately available at hand, particularly the first or last information received, and to minimize or ignore broader data or wider evidence that clearly exists but is not as easily remembered or accessed. E.g., ‘We know from experience that this doesn’t work,’ when ‘experience’ means the most recent local attempt, ignoring overwhelming experience from other places and times where it ha s worked and does work. Also related is the fallacy of Hyperbole [also, Magnification, or sometimes Catastrophizing] where an immediate instance is immediately proclaimed ‘the most significant in all of human history,’ or the ‘worst in the whole world!’ This latter fallacy works extremely well with less-educated audiences and those whose ‘whole world’ is very small indeed, audiences who ‘hate history’ and whose historical memory spans several weeks at best.

The Bandwagon Fallacy

Also: Argument from Common Sense, Argumentum ad Populum

The fallacy of arguing that because ‘everyone,’ ‘the people,’ or ‘the majority’ (or someone in power who has widespread backing) supposedly thinks or does something, it must therefore be true and right. E.g., ‘Whether there actually is large scale voter fraud in America or not, many people now think there is and that makes it so.’ Sometimes also includes Lying with Statistics , e.g. ‘Over 75% of Americans believe that crooked Bob Hodiak is a thief, a liar and a pervert. There may not be any evidence, but for anyone with half a brain that conclusively proves that Crooked Bob should go to jail! Lock him up! Lock him up!’ This is sometimes combined with the ‘Argumentum ad Baculum,’ e.g., ‘Like it or not, it’s time to choose sides: Are you going to get on board the bandwagon with everyone else, or get crushed under the wheels as it goes by?’ Or in the 2017 words of former White House spokesperson Sean Spicer, ”They should either get with the program or they can go,’ A contemporary digital form of the Bandwagon Fallacy is the Information Cascade, ‘ in which people echo the opinions of others, usually online, even when their own opinions or exposure to information contradicts that opinion. When information cascades form a pattern, this pattern can begin to overpower later opinions by making it seem as if a consensus already exists.’ (Thanks to Teaching Tolerance for this definition!)

See also Wisdom of the Crowd, and The Big Lie Technique.

For the opposite of this fallacy see the Romantic Rebel fallacy.

The Big Brain/Little Brain Fallacy

Also: the Führerprinzip; Mad Leader Disease

A not-uncommon but extreme example of the Blind Loyalty Fallacy below, in which a tyrannical boss, military commander, or religious or cult-leader tells followers ‘Don’t think with your little brains (the brain in your head), but with your BIG brain (mine).’ This last is sometimes expressed in positive terms, i.e., ‘You don’t have to worry and stress out about the rightness or wrongness of what you are doing since I, the Leader. am assuming all moral and legal responsibility for all your actions. So long as you are faithfully following orders without question I will defend you and gladly accept all the consequences up to and including eternal damnation if I’m wrong.’

The opposite of this is the fallacy of ‘Plausible Deniability.’ See also, ‘Just Do It!’, and ‘Gaslighting.’

The Big ‘But’ Fallacy

Also: Special Pleading

The fallacy of enunciating a generally-accepted principle and then directly negating it with a ‘but.’ Often this takes the form of the ‘Special Case,’ which is supposedly exempt from the usual rules of law, logic, morality, ethics or even credibility E.g., ‘As Americans, we have always believed on principle that every human being has God-given, inalienable rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, including in the case of criminal accusations a fair and speedy trial before a jury of one’s peers. BUT, your crime was so unspeakable and a trial would be so problematic for national security that it justifies locking you up for life in Guantanamo without trial, conviction or possibility of appeal.’ Or, ‘Yes, Honey, I still love you more than life itself, and I know that in my wedding vows I promised before God that I’d forsake all others and be faithful to you ‘until death do us part,’ but you have to understand, this was a special case…’

See also, ‘Shopping Hungry,’ and ‘We Have to do Something !’

The Big Lie Technique

Also: the Bold Faced Lie; ‘Staying on Message.’

The contemporary fallacy of repeating a lie, fallacy, slogan, talking-point, nonsense-statement, or deceptive half-truth over and over in different forms (particularly in the media) until it becomes part of daily discourse and people accept it without further proof or evidence. Sometimes the bolder and more outlandish the Big Lie becomes the more credible it seems to a willing, most often angry audience. E.g., ‘What about the Jewish Problem?’ Note that when this particular phony debate was going on there was no ‘Jewish Problem,’ only a Nazi Problem, but hardly anybody in power recognized or wanted to talk about that, while far too many ordinary Germans were only too ready to find a convenient scapegoat to blame for their suffering during the Great Depression. Writer Miles J. Brewer expertly demolishes The Big Lie Technique in his classic (1930) short story, ‘The Gostak and the Doshes.’ However, more contemporary examples of the Big Lie fallacy might be the completely fictitious August 4, 1964 ‘Tonkin Gulf Incident’ concocted under Lyndon Johnson as a false justification for escalating the Vietnam War, or the non-existent ‘Weapons of Mass Destruction’ in Iraq (conveniently abbreviated ‘WMD’s’ in order to lend this Big Lie a legitimizing, military-sounding ‘Alphabet Soup’ ethos), used in 2003 as a false justification for the Second Gulf War. The November, 2016 U.S. President-elect’s statement that ‘millions’ of ineligible votes were cast in that year’s American. presidential election appears to be a classic Big Lie.

See also, Alternative Truth; The Bandwagon Fallacy, the Straw Man, Alphabet Soup, and Propaganda.

Blind Loyalty

Also: Blind Obedience, Unthinking Obedience, the ‘Team Player’ appeal, the Nuremberg Defense

The dangerous fallacy that an argument or action is right simply and solely because a respected leader or source (a President, expert, one’s parents, one’s own ‘side,’ team or country, one’s boss or commanding officers) says it is right. This is over-reliance on authority, a gravely corrupted argument from ethos that puts loyalty above truth, above one’s own reason and above conscience. In this case a person attempts to justify incorrect, stupid or criminal behavior by whining ‘That’s what I was told to do,’ or ‘I was just following orders.’

See also, The Big Brain/Little Brain Fallacy, and The ‘Soldiers’ Honor’ Fallacy.

Blood is Thicker than Water

Also: Favoritism; Compadrismo; ‘For my friends, anything.’

The reverse of the ‘Ad Hominem’ fallacy, a corrupt argument from ethos where a statement, argument or action is automatically regarded as true, correct and above challenge because one is related to, knows and likes, or is on the same team or side, or belongs to the same religion, party, club or fraternity as the individual involved. (E.g., ‘My brother-in-law says he saw you goofing off on the job. You’re a hard worker but who am I going to believe, you or him? You’re fired!’) See also the Identity Fallacy.

Brainwashing

Also: Propaganda, ‘Radicalization.’

The Cold War-era fantasy that an enemy can instantly win over or ‘radicalize’ an unsuspecting audience with their vile but somehow unspeakably persuasive ‘propaganda,’ e.g., ‘Don’t look at that website! They’re trying to brainwash you with their propaganda!’ Historically, ‘brainwashing’ refers more properly to the inhuman Argumentum ad Baculum of ‘beating an argument into’ a prisoner via a combination of pain, fear, sensory or sleep deprivation, prolonged abuse and sophisticated psychological manipulation (also, the ‘ Stockholm Syndrome .’). Such ‘brainwashing’ can also be accomplished by pleasure (‘ Love Bombing ,’); e.g., ‘Did you like that? I know you did. Well, there’s lots more where that came from when you sign on with us!’ (See also, ‘Bribery.’) An unspeakably sinister form of persuasion by brainwashing involves deliberately addicting a person to drugs and then providing or withholding the substance depending on the addict’s compliance. Note: Only the other side brainwashes. ‘We’ never brainwash.

Also: Material Persuasion, Material Incentive, Financial Incentive

The fallacy of ‘persuasion’ by bribery, gifts or favors is the reverse of the Argumentum ad Baculum. As is well known, someone who is persuaded by bribery rarely ‘stays persuaded’ in the long term unless the bribes keep on coming in and increasing with time.

See also Appeasement.

Calling ‘Cards’

A contemporary fallacy of logos, arbitrarily and falsely dismissing familiar or easily-anticipated but valid, reasoned objections to one’s standpoint with a wave of the hand, as mere ‘cards’ in some sort of ‘game’ of rhetoric, e.g. ‘Don’t try to play the ‘Race Card’ against me,’ or ‘She’s playing the ‘Woman Card’ again,’ or ‘That ‘Hitler Card’ won’t score with me in this argument.’ See also, The Taboo, and Political Correctness.

Circular Reasoning

Also: The Vicious Circle; Catch 22, Begging the Question, Circulus in Probando

A fallacy of logos where A is because of B, and B is because of A, e.g., ‘You can’t get a job without experience, and you can’t get experience without a job.’ Also refers to falsely arguing that something is true by repeating the same statement in different words. E.g., ‘The witchcraft problem is the most urgent spiritual crisis in the world today. Why? Because witches threaten our very eternal salvation.’ A corrupt argument from logos. See also the ‘Big Lie technique.’

The Complex Question

The contemporary fallacy of demanding a direct answer to a question that cannot be answered without first analyzing or challenging the basis of the question itself. E.g., ‘Just answer me ‘yes’ or ‘no’: Did you think you could get away with plagiarism and not suffer the consequences?’ Or, ‘Why did you rob that bank?’ Also applies to situations where one is forced to either accept or reject complex standpoints or propositions containing both acceptable and unacceptable parts. A corruption of the argument from logos.

A counterpart of Either/Or Reasoning.

Confirmation Bias

A fallacy of logos, the common tendency to notice, search out, select and share evidence that confirms one’s own standpoint and beliefs, as opposed to contrary evidence. This fallacy is how ‘fortune tellers’ work–If I am told I will meet a ‘tall, dark stranger’ I will be on the lookout for a tall, dark stranger, and when I meet someone even marginally meeting that description I will marvel at the correctness of the ‘psychic’s’ prediction. In contemporary times Confirmation Bias is most often seen in the tendency of various audiences to ‘curate their political environments, subsisting on one-sided information diets and [even] selecting into politically homogeneous neighborhoods’ ( Michael A. Neblo et al., 2017, Science magazine ). Confirmation Bias (also, Homophily) means that people tend to seek out and follow solely those media outlets that confirm their common ideological and cultural biases, sometimes to a degree that leads a the false (implicit or even explicit) conclusion that ‘everyone’ agrees with that bias and that anyone who doesn’t is ‘crazy,’ ‘looney,’ evil or even ‘radicalized.’

See also, ‘Half Truth,’ and ‘Defensiveness.’

A fallacy of ethos (that of a product), the fact that something expensive (either in terms of money, or something that is ‘hard fought’ or ‘hard won’ or for which one ‘paid dearly’) is generally valued more highly than something obtained free or cheaply, regardless of the item’s real quality, utility or true value to the purchaser. E. g., ‘Hey, I worked hard to get this car! It may be nothing but a clunker that can’t make it up a steep hill, but it’s mine , and to me it’s better than some millionaire’s limo.’ Also applies to judging the quality of a consumer item (or even of its owner! ) primarily by the item’s brand, price, label or source, e.g., ‘Hey, you there in the Jay-Mart suit! Har-har!’ or, ‘Ooh, she’s driving a Mercedes! ‘

Default Bias

Also: Normalization of Evil, ‘Deal with it;’ ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it;’ Acquiescence; ‘Making one’s peace with the situation;’ ‘Get used to it;’ ‘Whatever is , is right;’ ‘It is what it is;’ ‘Let it be, let it be;’ ‘This is the best of all possible worlds [or, the only possible world];’ ‘Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t.’

The logical fallacy of automatically favoring or accepting a situation simply because it exists right now, and arguing that any other alternative is mad, unthinkable, impossible, or at least would take too much effort, expense, stress, or risk to change. The opposite of this fallacy is that of Nihilism (‘Tear it all down!’), blindly rejecting what exists in favor of what could be, the adolescent fantasy of romanticizing anarchy, chaos (an ideology sometimes called political ‘ Chaos Theory ‘), disorder, ‘permanent revolution,’ or change for change’s sake.

Defensiveness

Also: Choice-support Bias: Myside Bias

A fallacy of ethos (one’s own), in which after one has taken a given decision, commitment or course of action, one automatically tends to defend that decision and to irrationally dismiss opposing options even when one’s decision later on proves to be shaky or wrong. E.g., ‘Yeah, I voted for Snith. Sure, he turned out to be a crook and a liar and he got us into war, but I still say that at that time he was better than the available alternatives!’

See also ‘Argument from Inertia’ and ‘Confirmation Bias.’

Deliberate Ignorance

Also: Closed-mindedness; ‘I don’t want to hear it!’; Motivated Ignorance; Tuning Out; Hear No Evil, See No Evil, Speak No Evil [The Three Monkeys’ Fallacy]

As described by author and commentator Brian Resnik on Vox.com (2017), this is the fallacy of simply choosing not to listen, ‘tuning out’ or turning off any information, evidence or arguments that challenge one’s beliefs, ideology, standpoint, or peace of mind, following the popular humorous dictum: ‘Don’t try to confuse me with the facts; my mind is made up!’ This seemingly innocuous fallacy has enabled the most vicious tyrannies and abuses over history, and continues to do so today.

See also Trust your Gut, Confirmation Bias, The Third Person Effect, ‘They’re All Crooks,’ the Simpleton’s Fallacy, and The Positive Thinking Fallacy.

Diminished Responsibility

The common contemporary fallacy of applying a specialized judicial concept (that criminal punishment should be less if one’s judgment was impaired) to reality in general. E.g., ‘You can’t count me absent on Monday–I was hungover and couldn’t come to class so it’s not my fault.’ Or, ‘Yeah, I was speeding on the freeway and killed a guy, but I was buzzed out of my mind and didn’t know what I was doing so it didn’t matter that much.’ In reality the death does matter very much to the victim, to his family and friends, and to society in general. Whether the perpetrator was high or not does not matter at all since the material results are the same. This also includes the fallacy of Panic , a very common contemporary fallacy that one’s words or actions, no matter how damaging or evil, somehow don’t ‘count’ because ‘I panicked!’ This fallacy is rooted in the confusion of ‘consequences’ with ‘punishment.’

See also ‘Venting.’

Disciplinary Blinders

A very common contemporary scholarly or professional fallacy of ethos (that of one’s discipline, profession or academic field), automatically disregarding, discounting or ignoring a priori otherwise-relevant research, arguments and evidence that come from outside one’s own professional discipline, discourse community or academic area of study. E.g., ‘That might be relevant or not, but it’s so not what we’re doing in our field right now.’ See also, ‘Star Power’ and ‘Two Truths.’ An analogous fallacy is that of Denominational Blinders , arbitrarily ignoring or waving aside without serious consideration any arguments or discussion about faith, morality, ethics, spirituality, the Divine or the afterlife that come from outside one’s own specific religious denomination or faith tradition.

Dog-Whistle Politics

An extreme version of reductionism and sloganeering in the public sphere, a contemporary fallacy of logos and pathos in which a brief phrase or slogan of the hour, e.g., ‘Abortion,’ ‘The 1%,’ ‘9/11,’ ‘Zionism,”Chain Migration,’ ‘Islamic Terrorism,’ ‘Fascism,’ ‘Communism,’ ‘Big government,’ ‘Taco trucks!’, ‘Tax and tax and spend and spend,’ ‘Gun violence,’ ‘Gun control,’ ‘Freedom of choice,’ ‘Lock ’em up,’, ‘Amnesty,’ etc. is flung out as ‘red meat’ or ‘chum in the water’ that reflexively sends one’s audience into a snapping, foaming-at-the-mouth feeding-frenzy. Any reasoned attempt to more clearly identify, deconstruct or challenge an opponent’s ‘dog whistle’ appeal results in puzzled confusion at best and wild, irrational fury at worst. ‘Dog whistles’ differ widely in different places, moments and cultural milieux, and they change and lose or gain power so quickly that even recent historic texts sometimes become extraordinarily difficult to interpret. A common but sad instance of the fallacy of Dog Whistle Politics is that of candidate ‘debaters’ of differing political shades simply blowing a succession of discursive ‘dog whistles’ at their audience instead of addressing, refuting or even bothering to listen to each other’s arguments, a situation resulting in contemporary (2017) allegations that the political Right and Left in America are speaking ‘different languages’ when they are simply blowing different ‘dog whistles.’

See also, Reductionism..

The ‘Draw Your Own Conclusion’ Fallacy

Also: the Non-argument Argument; Let the Facts Speak for Themselves

In this fallacy of logos, an otherwise uninformed audience is presented with carefully selected and groomed, ‘shocking facts’ and then prompted to immediately ‘draw their own conclusions.’ E.g., ‘Crime rates are more than twice as high among middle-class Patzinaks than among any other similar population group–draw your own conclusions.’ It is well known that those who are allowed to ‘come to their own conclusions’ are generally much more strongly convinced than those who are given both evidence and conclusion upfront. However, Dr. William Lorimer points out that ‘The only rational response to the non-argument is ‘So what?’ i.e. ‘What do you think you’ve proved, and why/how do you think you’ve proved it?” Closely related (if not identical) to this is the well-known ‘Leading the Witness’ Fallacy , where a sham, sarcastic or biased question is asked solely in order to evoke a desired answer.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

A cognitive bias that leads people of limited skills or knowledge to mistakenly believe their abilities are greater than they actually are. (Thanks to Teaching Tolerance for this definition!) E.g., ‘I know Washington was the Father of His Country and never told a lie, Pocahontas was the first Native American, Lincoln freed the slaves, Hitler murdered six million Jews, Susan B. Anthony won equal rights for women, and Martin Luther King said ‘I have a dream!’ Moses parted the Red Sea, Caesar said ‘Et tu, Brute?’ and the only reason America didn’t win the Vietnam War hands-down like we always do was because they tied our generals’ hands and the politicians cut and run. See? Why do I need to take a history course? I know everything about history!’

E’ for Effort

Also: Noble Effort; I’m Trying My Best; The Lost Cause

The common contemporary fallacy of ethos that something must be right, true, valuable, or worthy of respect and honor solely because one (or someone else) has put so much sincere good-faith effort or even sacrifice and bloodshed into it. (See also Appeal to Pity; Argument from Inertia; Heroes All; or Sob Story). An extreme example of this fallacy is Waving the Bloody Shirt ( also , the ‘Blood of the Martyrs’ Fallacy) , the fallacy that a cause or argument, no matter how questionable or reprehensible, cannot be questioned without dishonoring the blood and sacrifice of those who died so nobly for that cause. E.g., ‘ Defend the patriotic gore / That flecked the streets of Baltimore.. .’ (from the official Maryland State Song).

See also Cost Bias, The Soldier’s Honor Fallacy, and the Argument from Inertia.

Either/Or Reasoning

Also: False Dilemma, All or Nothing Thinking; False Dichotomy, Black/White Fallacy, False Binary

A fallacy of logos that falsely offers only two possible options even though a broad range of possible alternatives, variations, and combinations are always readily available. E.g., ‘Either you are 100% Simon Straightarrow or you are as queer as a three dollar bill–it’s as simple as that and there’s no middle ground!’ Or, ‘Either you’re in with us all the way or you’re a hostile and must be destroyed! What’s it gonna be?’ Or, if your performance is anything short of perfect, you consider yourself an abject failure. Also applies to falsely contrasting one option or case to another that is not really opposed, e.g., falsely opposing ‘Black Lives Matter’ to ‘Blue Lives Matter’ when in fact not a few police officers are themselves African American, and African Americans and police are not (or ought not to be!) natural enemies. Or, falsely posing a choice of either helping needy American veterans or helping needy foreign refugees, when in fact in today’s United States there are ample resources available to easily do both should we care to do so.

See also, Overgeneralization.

Equivocation

The fallacy of deliberately failing to define one’s terms, or knowingly and deliberately using words in a different sense than the one the audience will understand. (E.g., President Bill Clinton stating that he did not have sexual relations with ‘that woman,’ meaning no sexual penetration, knowing full well that the audience will understand his statement as ‘I had no sexual contact of any kind with that woman.’) This is a corruption of the argument from logos, and a tactic often used in American jurisprudence. Historically, this referred to a tactic used during the Reformation-era religious wars in Europe, when people were forced to swear loyalty to one or another side and did as demanded via ‘equivocation,’ i.e., ‘When I solemnly swore true faith and allegiance to the King I really meant to King Jesus, King of Kings, and not to the evil usurper squatting on the throne today.’ This latter form of fallacy is excessively rare today when the swearing of oaths has become effectively meaningless except as obscenity or as speech formally subject to perjury penalties in legal or judicial settings.

The Eschatological Fallacy

The ancient fallacy of arguing, ‘This world is coming to an end, so…’ Popularly refuted by the observation that ‘Since the world is coming to an end you won’t need your life savings anyhow, so why not give it all to me?’

Esoteric Knowledge

Also: Esoteric Wisdom; Gnosticism; Inner Truth; the Inner Sanctum; Need to Know

A fallacy from logos and ethos, that there is some knowledge reserved only for the Wise, the Holy or the Enlightened, (or those with proper Security Clearance), things that the masses cannot understand and do not deserve to know, at least not until they become wiser, more trusted or more ‘spiritually advanced.’ The counterpart of this fallacy is that of Obscurantism (also Obscurationism, or Willful Ignorance), that (almost always said in a basso profundo voice) ‘There are some things that we mere mortals must never seek to know!’ E.g., ‘Scientific experiments that violate the privacy of the marital bed and expose the deep and private mysteries of human sexual behavior to the harsh light of science are obscene, sinful and morally evil. There are some things that we as humans are simply not meant to know!’ For the opposite of this latter, see the ‘Plain Truth Fallacy.’

See also, Argumentum ad Mysteriam.

Essentializing

A fallacy of logos that proposes a person or thing ‘is what it is and that’s all that it is,’ and at its core will always be the way it is right now (E.g., ‘All terrorists are monsters, and will still be terrorist monsters even if they live to be 100,’ or ”The poor you will always have with you,’ so any effort to eliminate poverty is pointless.’). Also refers to the fallacy of arguing that something is a certain way ‘by nature,’ an empty claim that no amount of proof can refute. (E.g., ‘Americans are cold and greedy by nature,’ or ‘Women are naturally better cooks than men.’) See also ‘Default Bias.’ The opposite of this is Relativizing, the typically postmodern fallacy of blithely dismissing any and all arguments against one’s standpoint by shrugging one’s shoulders and responding ‘ Whatever…, I don’t feel like arguing about it;’ ‘It all depends…;’ ‘That’s your opinion; everything’s relative;’ or falsely invoking Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, Quantum Weirdness or the Theory of Multiple Universes in order to confuse, mystify or ‘refute’ an opponent.

See also, ‘Red Herring’ and ‘Appeal to Nature.’

The Etymological Fallacy

Also: ‘The Underlying Meaning’

A fallacy of logos, drawing false conclusions from the (most often long-forgotten) linguistic origins of a current word, or the alleged meanings or associations of that word in another language. E.g., ‘As used in physics, electronics and electrical engineering the term ‘hysteresis’ is grossly sexist since it originally came from the Greek word for ‘uterus’ or ‘womb.” Or, ‘I refuse to eat fish! Don’t you know that the French word for ‘fish’ is ‘poisson,’ which looks just like the English word ‘poison’? And doesn’t that suggest something to you?’ Famously, postmodern philosopher Jacques Derrida played on this fallacy at great length in his (1968) ‘Plato’s Pharmacy.’

The Excluded Middle

A corrupted argument from logos that proposes that since a little of something is good, more must be better (or that if less of something is good, none at all is even better). E.g., ‘If eating an apple a day is good for you, eating an all-apple diet is even better!’ or ‘If a low fat diet prolongs your life, a no-fat diet should make you live forever!’ An opposite of this fallacy is that of Excluded Outliers , where one arbitrarily discards evidence, examples or results that disprove one’s standpoint by simply describing them as ‘Weird,’ ‘Outliers,’ or ‘Atypical.’ See also, ‘The Big ‘But’ Fallacy.’ Also opposite is the Middle of the Road Fallacy (also, Falacia ad Temperantiam; ‘The Politics of the Center;’ Marginalization of the Adversary), where one demonstrates the ‘reasonableness’ of one’s own standpoint (no matter how extreme) not on its own merits, but solely or mainly by presenting it as the only ‘moderate’ path among two or more obviously unacceptable extreme alternatives. E.g., anti-Communist scholar Charles Roig (1979) notes that Vladimir Lenin successfully argued for Bolshevism in Russia as the only available ‘moderate’ middle path between bomb-throwing Nihilist terrorists on the ultra-left and a corrupt and hated Czarist autocracy on the right. As Texas politician and humorist Jim Hightower famously declares in an undated quote, ‘The middle of the road is for yellow lines and dead armadillos.’

The ‘F-Bomb’

Also: Cursing; Obscenity; Profanity

An adolescent fallacy of pathos, attempting to defend or strengthen one’s argument with gratuitous, unrelated sexual, obscene, vulgar, crude or profane language when such language does nothing to make an argument stronger, other than perhaps to create a sense of identity with certain young male ‘urban’ audiences. This fallacy also includes adding gratuitous sex scenes or ‘adult’ language to an otherwise unrelated novel or movie, sometimes simply to avoid the dreaded ‘G’ rating. Related to this fallacy is the Salacious Fallacy , falsely attracting attention to and thus potential agreement with one’s argument by inappropriately sexualizing it, particularly connecting it to some form of sex that is perceived as deviant, perverted or prohibited (E.g., Arguing against Bill Clinton’s presidential legacy by continuing to wave Monica’s Blue Dress, or against Donald Trump’s presidency by obsessively highlighting his past boasting about genital groping). Historically, this dangerous fallacy was deeply implicated with the crime of lynching, in which false, racist accusations against a Black or minority victim were almost always salacious in nature, and the sensation involved was successfully used to whip up public emotion to a murderous pitch.

See also, Red Herring.

The False Analogy

The fallacy of incorrectly comparing one thing to another in order to draw a false conclusion. E.g., ‘Just like an alley cat needs to prowl, a normal adult can’t be tied down to one single lover.’ The opposite of this fallacy is the Sui Generis Fallacy (also, Differance), a postmodern stance that rejects the validity of analogy and of inductive reasoning altogether because any given person, place, thing or idea under consideration is ‘sui generis’ i.e., different and unique, in a class unto itself.

Finish the Job

The dangerous contemporary fallacy, often aimed at a lesser-educated or working-class audience, that an action or standpoint (or the continuation of that action or standpoint) may not be questioned or discussed because there is ‘a job to be done’ or finished, falsely assuming ‘jobs’ are meaningless but never to be questioned. Sometimes those involved internalize (‘buy into’) the ‘job’ and make the task a part of their own ethos.

Example: ‘Ours is not to reason why / Ours is but to do or die.’) Related to this is the ‘ Just a Job’ fallacy. (E.g., ‘How can torturers stand to look at themselves in the mirror? But I guess it’s OK because for them it’s just a job like any other, the job that they get paid to do.’)

See also ‘Blind Loyalty,’ ‘The Soldiers’ Honor Fallacy’ and the ‘Argument from Inertia.’

The Free Speech Fallacy

The infantile fallacy of responding to challenges to one’s statements and standpoints by whining, ‘It’s a free country, isn’t it? I can say anything I want to!’ A contemporary case of this fallacy is the ‘ Safe Space,’ or ‘Safe Place,’ where it is not allowed to refute, challenge or even discuss another’s beliefs because that might be too uncomfortable or ‘triggery’ for emotionally fragile individuals. E.g., ‘All I told him was, ‘Jesus loves the little children,’ but then he turned around and asked me ‘But what about birth defects?’ That’s mean. I think I’m going to cry!’ Prof. Bill Hart Davidson (2017) notes that ‘Ironically, the most strident calls for ‘safety’ come from those who want us to issue protections for discredited ideas. Things that science doesn’t support AND that have destroyed lives – things like the inherent superiority of one race over another. Those ideas wither under demands for evidence. They *are* unwelcome. But let’s be clear: they are unwelcome because they have not survived the challenge of scrutiny.’ Ironically, in contemporary America ‘free speech’ has often become shorthand for freedom of racist, offensive or even neo-Nazi expression, ideological trends that once in power typically quash free speech. Additionally, a (201) scientific study has found that, in fact, ‘ people think harder and produce better political arguments when their views are challenged ‘ and not artificially protected without challenge.

The Fundamental Attribution Error

Also: Self Justification

A corrupt argument from ethos, this fallacy occurs as a result of observing and comparing behavior. ‘You assume that the bad behavior of others is caused by character flaws and foul dispositions while your behavior is explained by the environment. So, for example, I get up in the morning at 10 a.m. I say it is because my neighbors party until 2 in the morning (situation) but I say that the reason why you do it is that you are lazy. Interestingly, it is more common in individualistic societies where we value self volition. Collectivist societies tend to look at the environment more. (It happens there, too, but it is much less common.)’ [Thanks to scholar Joel Sax for this!] The obverse of this fallacy is Self Deprecation (also Self Debasement) , where, out of either false humility or a genuine lack of self-esteem, one deliberately puts oneself down, most often in hopes of attracting denials, gratifying compliments, and praise.

Gaslighting