John Nash’s Super Short PhD Thesis: 26 Pages & 2 Citations

in Math | July 9th, 2018 2 Comments

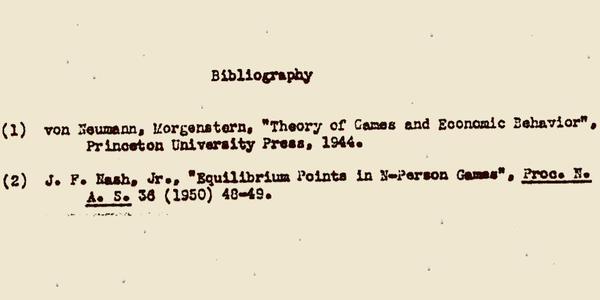

When John Nash wrote “Non Cooperative Games,” his Ph.D. dissertation at Princeton in 1950, the text of his thesis ( read it online ) was brief. It ran only 26 pages. And more particularly, it was light on citations. Nash’s diss cited two texts: John von Neumann & Oskar Morgenstern’s Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944), which essentially created game theory and revolutionized the field of economics; the other cited text, “Equilibrium Points in n‑Person Games,” was an article written by Nash himself. And it laid the foundation for his dissertation, another seminal work in the development of game theory, for which Nash won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1994 .

The reward of inventing a new field is having a slim bibliography.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in June, 2015.

Related Content:

The Shortest-Known Paper Published in a Serious Math Journal: Two Succinct Sentences

The World Record for the Shortest Math Article: 2 Words

Free Online Math Courses

Free Math Textbooks

by OC | Permalink | Comments (2) |

Related posts:

Comments (2), 2 comments so far.

Sometimes doctoral dissertations are long on footnotes and bibliography — and short on original thinking. John Nash reversed the academic trend. Reminds me of the Renaissance painter who was asked for evidence of his ability to draw. He drew a near-perfect circle on a canvas, and was accepted by the master as an apprentice.

Excellent concept and articles.…worth reading.…pl forward more reading

Thanks and regards

Dr B Vijay Sarthi

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1500 Free Courses

- 1000+ MOOCs & Certificate Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Beat & Tweets

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Receive our newsletter!

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Book Lists By

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Favorite Movies

- Kurosawa's 100

- David Lynch

- Werner Herzog

- Woody Allen

- Wes Anderson

- Luis Buñuel

- Roger Ebert

- Susan Sontag

- Scorsese Foreign Films

- Philosophy Films

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

©2006-2024 Open Culture, LLC. All rights reserved.

- Advertise with Us

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 24 June 2015

John Forbes Nash (1928–2015)

- Martin A. Nowak 1

Nature volume 522 , page 420 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

31k Accesses

90 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Mathematics and computing

Master of games and equations.

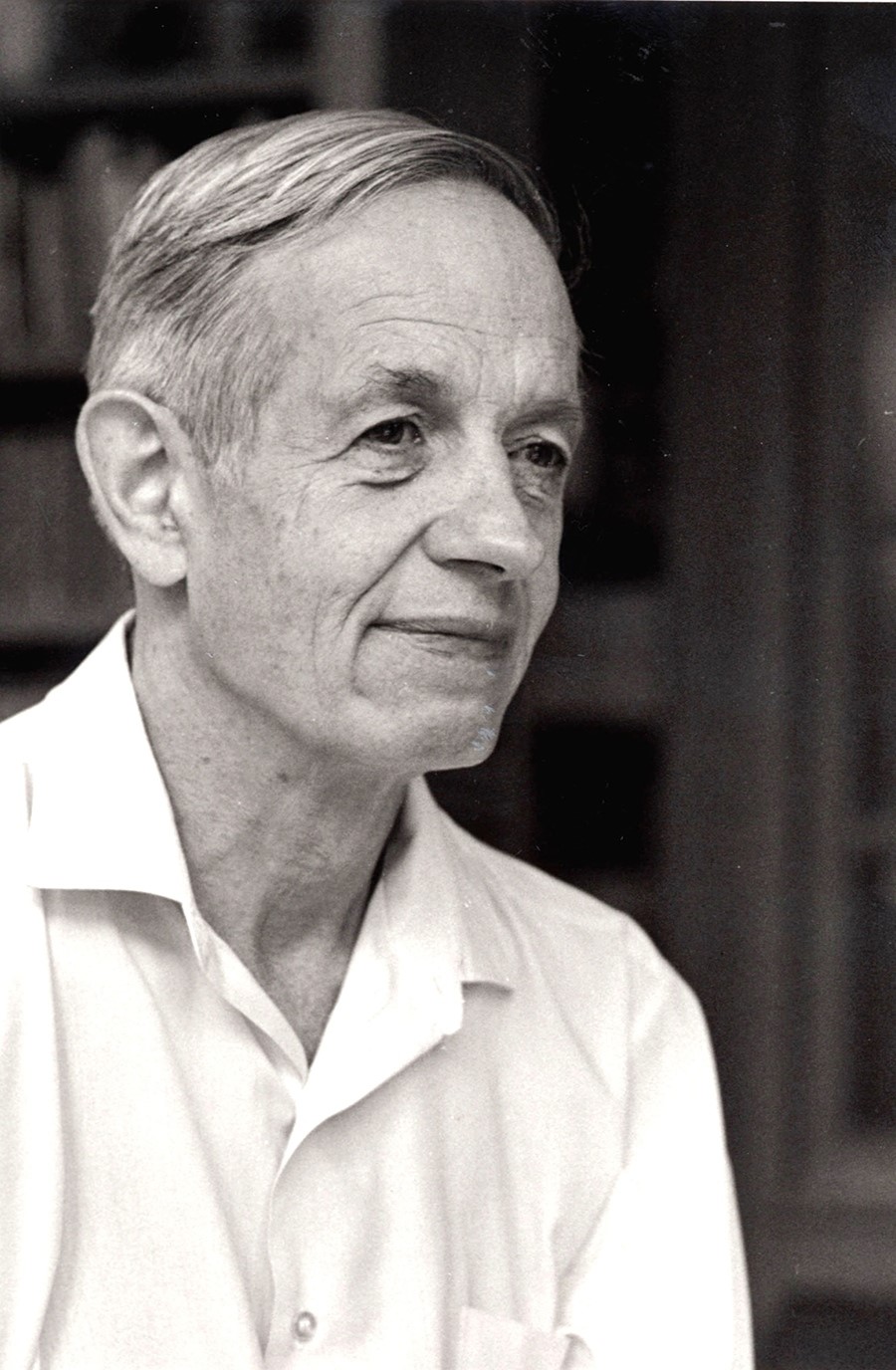

John Forbes Nash, an exalted mathematician whose life took dramatic turns between genius, mental illness and celebrity status, made major contributions to game theory, geometry and the field of partial differential equations.

Nash, who died on 23 May, was born in Bluefield, West Virginia, in 1928. His father was an electrical engineer and his mother a schoolteacher. In 1945, after excelling in mathematics at high school, he attended the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. At first he studied chemical engineering, but soon after enrolling he switched to chemistry and then to maths.

In Nash's final year, one of his professors wrote a recommendation letter for the 19-year-old supporting his application to graduate school. It simply stated: “He is a mathematical genius.” In 1948, Nash was accepted by Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and by Princeton University in New Jersey. He chose Princeton.

As a PhD student, Nash proved the existence of the equilibrium that now carries his name. His 1950 paper 'Equilibrium points in n -person games', contains about 330 words, two references and not one equation (J. F. Nash Jr Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 36 , 48–49; 1950). One of the citations is the 1944 book Theory of Games and Economic Behavior — in which mathematician John von Neumann and economist Oskar Morgenstern introduce game theory, a mathematical approach for studying strategic and economic decisions.

The Nash equilibrium is a position in a game from which none of the players can change their strategy to improve their pay-off. Imagine a game with two players (yourself and another person) and two strategies, A and B. If you both choose A, your pay-off is 2. If you choose A and your opponent chooses B, you score 0. If you choose B and the other player chooses A, your pay-off is 3. If you both choose B, you score 1. The same applies to your opponent.

In this example, the Nash equilibrium occurs when both players choose B. If both players choose B, their pay-off is 1; if either player switches to A, their pay-off falls to 0. In other words, neither player can independently switch their strategy and improve their pay-off. Observe that if both players select A, there is no Nash equilibrium because you could improve your pay-off by switching to B.

Calculating the Nash equilibrium can be a formidable task in a complex game. There is also the uncertainty over whether the person you are playing against is sufficiently rational to play the equilibrium strategy. If both players are rational and their rationality is common knowledge, they would play it. But experiments often reveal that people are not rational. Regardless of whether people actually play the Nash equilibrium in social or economic interactions, working out what it is (or what the Nash equilibria are) is the first step to analysing any game.

Although dismissed at the time by von Neumann as a triviality, the Nash equilibrium has been used to analyse all sorts of competitive situations. As well as being key to decision-making in economics and politics, the idea is important in biology. Here, the nearly equivalent concept, formulated by evolutionary biologist John Maynard Smith in the 1970s is called an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS). If all members of a population adopt an ESS, then natural selection prevents a rare mutant from spreading.

On completing his PhD, Nash joined the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge in 1951. He worked — first as an instructor and later as a professor — in the mathematics faculty until he resigned in 1959. It was while he was at MIT that Nash met and married Alicia Lopez-Harrison de Lardé, a physics student there.

Among mathematicians, Nash is best known for his work in real algebraic geometry and nonlinear partial differential equations. He was not afraid to tackle the hardest problems in the field, and he succeeded. In 1957, he — in parallel with Italian mathematician Ennio de Giorgi — solved Hilbert's nineteenth problem involving partial differential equations.

It was during a talk in 1959 on what is seen to be one of the hardest problems in maths — the Riemann hypothesis — that the audience realized that there was something wrong with Nash. His talk was incomprehensible.

He was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia that year. Over the next two decades, Nash was in and out of hospitals. He underwent therapy, and for a while left the United States and sought asylum in Switzerland in an attempt to escape his imagined tormentors. For many years he wandered around the Princeton campus. Throughout this period, Alicia, who divorced Nash in 1963, oversaw much of his care.

In the late 1980s, Nash reappeared in academic circles, and in 1994 he was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his work on game theory. The Nobel and the 2001 film A Beautiful Mind , based on journalist Sylvia Nasar's book of the same name, which recounted Nash's struggles, propelled him into the limelight.

In May this year, Nash received the Abel prize from the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters for his work on partial differential equations. On the way back from the celebration in Norway, John and Alicia (who had remarried in 2001) were killed in a car accident in a taxi on the New Jersey turnpike. John was 86.

I met John in 1998 at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Over the years, I gave several talks there that he attended. One summer's day, when the usual sitting arrangements for lunch were disrupted by the closure of the main kitchen, I noticed John, the physicist Edward Witten and Andrew Wiles, the British mathematician who proved Fermat's last theorem, sitting down together at a small table. I wondered which of them would start the conversation. None of them did. I seem to remember that they ate their meal in silence.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Martin A. Nowak is professor of mathematics and biology, and director of the Program for Evolutionary Dynamics at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.,

Martin A. Nowak

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Martin A. Nowak .

Related links

Related links in nature research.

'Beautiful mind' John Nash adds Abel Prize to his Nobel

Nature special: John Nash

Related external links

Nobelprize.org: John Nash biography

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nowak, M. John Forbes Nash (1928–2015) . Nature 522 , 420 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/522420a

Download citation

Published : 24 June 2015

Issue Date : 25 June 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/522420a

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: AI and Robotics newsletter — what matters in AI and robotics research, free to your inbox weekly.

John Nash: The Genius Who Shaped Game Theory and Economics

- Publication date January 18, 2024

John Nash’s profound impact on economics and mathematics is a story of intellectual brilliance, personal struggle, and enduring legacy. His journey from a precocious student to a Nobel laureate illuminates the intersection of pure mathematics and economic theory.

Early Life and Education

Born in 1928 in Bluefield, West Virginia, Nash showed early signs of extraordinary intellectual ability. His parents, recognizing his talent, nurtured his academic interests. Nash’s advanced understanding of mathematics led him to take college-level courses while still in high school.

Academic Prodigy at Carnegie and Princeton

Nash’s academic prowess continued to flourish at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, where he completed both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in mathematics by the age of 19. His remarkable abilities were encapsulated in the succinct recommendation from his adviser, attesting to his “mathematical genius.”

Groundbreaking Work at Princeton

Nash’s time at Princeton University was pivotal. His doctoral dissertation, “Non-Cooperative Games,” was a mere 28 pages but laid the groundwork for modern game theory. The Nash equilibrium, a concept introduced in this work, transformed the understanding of decision-making processes in economics, where multiple actors with conflicting interests are involved.

Professional Life and Mental Health Struggles

Nash’s professional tenure at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and his work as a codebreaker for the U.S. government were marked by his developing symptoms of mental illness. Diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, Nash’s life took a turn as he faced immense personal challenges. Despite these struggles, his intellectual contributions continued, and he resumed his academic career at Princeton.

Nobel Prize and Recognition

In 1994, Nash’s groundbreaking work was recognized with the Nobel Prize in Economics. This accolade brought his contributions to a wider audience, bridging the gap between abstract mathematical theories and practical economic applications.

Cultural Impact and “A Beautiful Mind”

Nash’s life story, marked by both triumph and adversity, was vividly captured in Sylvia Nasar’s biography “A Beautiful Mind” and the subsequent Academy Award-winning film. These works brought Nash’s story and the complexity of his theories to a global audience, making Nash a household name.

A Tragic End and Enduring Legacy

John Nash’s life tragically ended in a taxi crash in 2015, soon after receiving the Abel Prize, one of the highest honors in mathematics. His death marked the loss of one of the most brilliant minds of the 20th century.

Nash’s work continues to influence a wide range of fields, from economics and mathematics to biology and political science. His legacy lives on through the Nash equilibrium, a concept that has become a fundamental tool in understanding complex systems where strategic interactions occur. John Nash remains a symbol of how intellectual prowess can overcome personal challenges and contribute to the broader understanding of our world.

John Nash (1928–2015)

- First Online: 29 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Panayotis G. Michaelides 3 &

- Theodoulos Eleftherios Papadakis 3

467 Accesses

After having studied this chapter, the reader should be able to:

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Nash ( 1995 ).

Nash ( 1996 ).

Leonard ( 1994 ).

Fragnelli and Gambarelli ( 2015 ).

Nasar ( 1998 ).

Rubinstein ( 1995 ).

Our discussion follows Myerson ( 1999 ).

Cournot ( 1838 ).

Myerson ( 1999 ).

Borel ( 1921 ).

von Neumann ( 1928 ).

Myerson ( 1999 )

von Neumann and Morgenstern ( 1944 ).

Screpanti and Zamagni ( 2005 ).

Nash ( 1950b ).

Nash ( 1950a ).

Nash ( 1951 ).

Mornati ( 2018 ).

Varoufakis ( 2007 ).

Milnor ( 1995 ).

Economist ( 2016 ).

Colman et al. ( 2018 ).

Myerson ( 1978 ).

Kreps and Wilson ( 1982 ).

Harsanyi ( 1967 –1968).

Aumann ( 1974 ).

Fellman ( 2007 )

Daskalakis et al. ( 2009 ).

Babichenko and Rubinstein ( 2020 ).

Daskalakis et al. ( 2009 , p. 196).

See also Karlin and Perez ( 2017 , p. 84).

Schwartz-Shea ( 2002 )

Margaret Thatcher in Brittan ( 2013 ).

Bix ( 2007 ).

Aumann, R. J. (1974). Subjectivity and correlation in randomized strategies. Journal of Mathematical Economics, 1 , 67–96.

Article Google Scholar

Babichenko, Y., & Rubinstein, A. (2020). Communication complexity of approximate Nash equilibria. Games and Economic Behavior, 134 (July), 376–398.

Google Scholar

Bix, B. (2007). Philosophy of law: Theory and interpretative framework . Kritiki Publications.

Borel, E. (1921). La théorie du jeu et les equation intégrales à noyau symétrique gauche. ComptesRendus de l’Académie des Sciences, 173 , 1304–1308.

Brittan, S. (2013, April 18). Thatcher was right—There is no ‘society’. Financial Times . Retrieved April 1, 2021, from https://www.ft.com/content/d1387b70-a5d5-11e2-9b77-00144feabdc0

Colman, A. M., Pulford, B. D., & Krockow, E. M. (2018). Persistent cooperation and gender differences in repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma games: Some things never change. Acta Psychological, 187 , 1–8.

Cournot, A. (1838). Recherches sur les Principes Mathématiques de la Théorie des Richesses . Hachette.

Daskalakis, C., Goldberg, P. W., & Papadimitriou, C. H. (2009). The complexity of computing a Nash equilibrium. SIAM Journal on Computing, 39 (3), 195–259.

Economist. (2016, August 26). Prison breakthrough. Game Theory . Retrieved March 30, 2021, from https://amp.economist.com/schools-brief/2016/08/20/prison-breakthrough

Fellman, P. V. (2007). The Nash equilibrium revisited: Chaos and complexity hidden in simplicity . Fellman Southern New Hampshire University.

Fragnelli, V., & Gambarelli, G. (2015). John Forbes Nash (1928–2015). The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 22 (5), 923–926.

Harsanyi, J. C. (1967–1968). Games with incomplete information played by ‘Bayesian’ players. Management Science , 14, 159–182.

Karlin, A., & Perez, Y. (2017). Game theory, alive . American Mathematical Society.

Book Google Scholar

Kreps, D., & Wilson, R. (1982). Sequential equilibria. Econometrica, 50 , 863–894.

Leonard, R. J. (1994). Reading Cournot, Reading Nash: The creation and stabilisation of the Nash equilibrium. Economic Journal, 104 , 492–511.

Milnor, J. (1995). A Nobel prize for John Nash. Mathematical Intelligencer, 17 (3), 11–17.

Mornati, F. (2018). Vilfredo Pareto: An intellectual biography volume I . Palgrave Studies in the History of Economic Thought.

Myerson, R. B. (1978). Refinements of the Nash equilibrium concept. International Journal of Game Theory, 7 , 73–80.

Myerson, R. B. (1999). Nash equilibrium and the history of economic theory. Journal of Economic Literature, 37 (3), 1067–1082.

Nasar, S. (1998). A beautiful mind . Simon & Schuster.

Nash, J. (1950a). The bargaining problem. Econometrica, 18 , 155–162.

Nash, J. (1950b). Equilibrium points in n-person games. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A., 36 , 48–49.

Nash, J. (1951). Noncooperative games. Annals of Mathematics, 54 , 289–295.

Nash, J. (1995). The Nobel Prizes 1994 (T. Frängsmyr, Ed.) Nobel Foundation.

Nash, J. (1996). Essays on game theory . Edward Elgar.

Rubinstein, A. (1995). John Nash: The master of economic modeling. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 97 , 9–13.

Schwartz-Shea, P. (2002). Theorizing gender for experimental game theory: Experiments with “Sex Status” and “Merit Status” in an asymmetric game. Sex Roles, 47 , 301–319.

Screpanti, E., & Zamagni, S. (2005). An outline of the history of economic thought . OUP.

Varoufakis, G. (2007). Game theory . Gutenberg Publications.

von Neumann, J. (1928). On the theories of parlor games. MathematischeAnnalen, 100 , 295–320.

von Neumann, J., & Morgenstern, O. (1944). Theory of games and economic behavior . Princeton University Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

National Technical University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Panayotis G. Michaelides & Theodoulos Eleftherios Papadakis

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Michaelides, P.G., Papadakis, T.E. (2023). John Nash (1928–2015). In: History of Economic Ideas. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19697-3_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19697-3_10

Published : 29 January 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-19696-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-19697-3

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance Economics and Finance (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

MIT Libraries logo MIT Libraries

Year 91 – 1951: “Non-cooperative Games” by John Nash, in: Annals of Mathematics 54 (2)

Posted on April 7, 2011 in All years , Uncategorized

Over the past 60 years, game theory has been one of the most influential theories in the social sciences, pervasive in economics, political science, business administration, and military strategy – the disciplines most consulted by the powers-that-be for “real-world,” high-stakes decisions. But just as there would be no semiconductors or (God forbid) laser pointers if not for the abstruse mathematics of quantum theory, game theory can be traced back to theoretical work by academic mathematicians. In a set of papers in the 1950s, mathematician John Forbes Nash set forth breakthrough ideas that helped transform game theory from an ivory tower abstraction into an indispensable analytical tool used by strategists from Wall Street to the Pentagon.

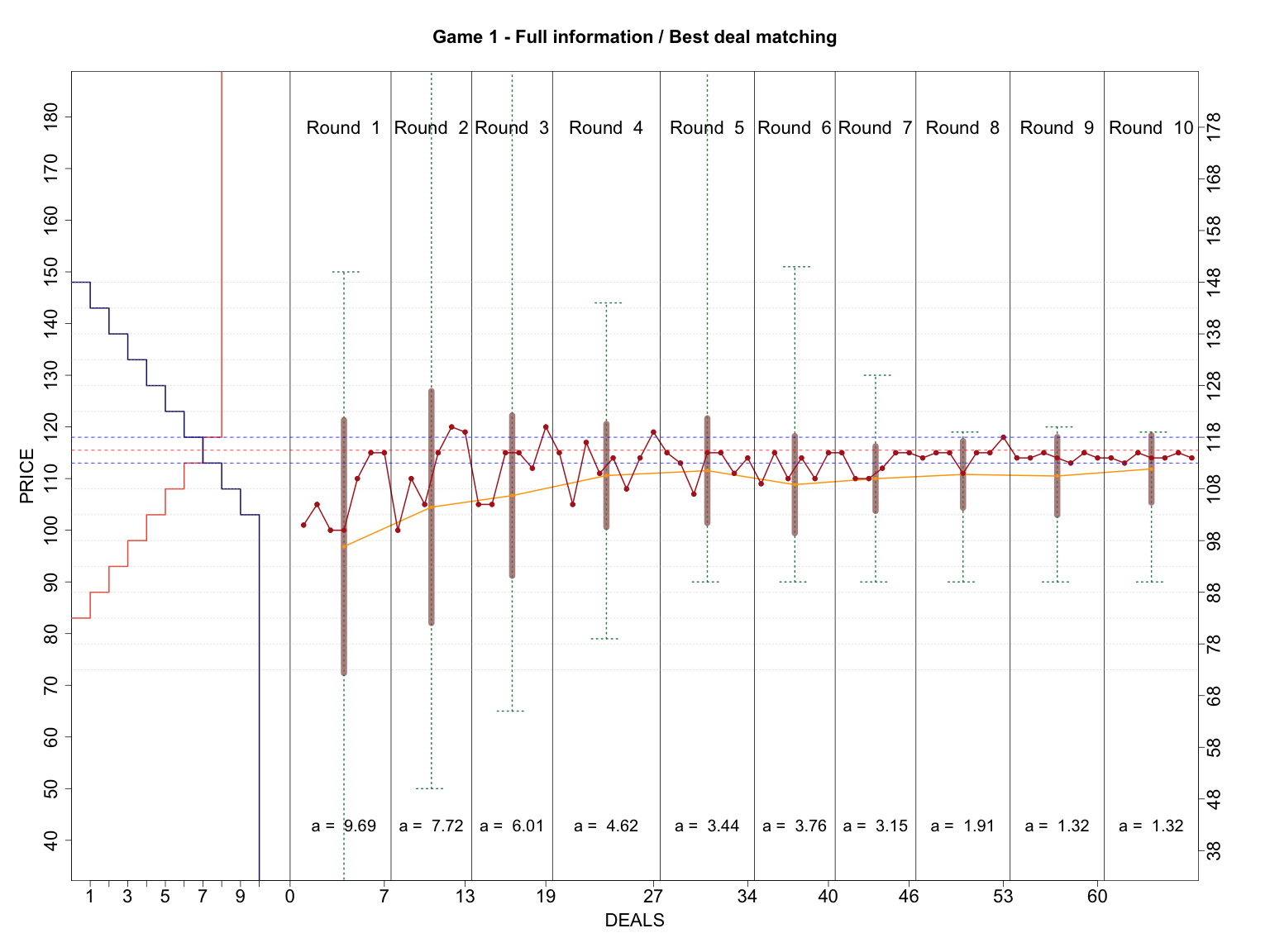

The foundational game theory work of mathematician John von Neumann and economist Oskar Morgenstern, published in 1944, provided a framework for solutions to zero-sum games, where one player’s win was the other’s loss. Nash, in his dissertation research at Princeton (published in this and three other papers), extended game theory to n -person games in which more than one party can gain, a better reflection of practical situations. Nash demonstrated that “a finite non-cooperative game always has at least one equilibrium point” or stable solution. This result came to be called the “Nash equilibrium,” a situation where no one player can get a better payoff by changing strategies, so long as other players also keep their strategies. Using Nash’s framework, predictions can be made about the outcomes of strategic interactions.

Based on Nash’s advances, game theory developed into one of the pre-eminent tools of economics in the second half of the 20th century. In recognition of his breakthrough work, Nash was joint recipient of the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1994 for “pioneering analysis of equilibria in the theory of non-cooperative games.”

If visions of Russell Crowe have danced in your head while you’ve been reading this post, that’s probably because you remember that Crowe played John Forbes Nash in the 2001 film A Beautiful Mind (at least we hope that’s why). Part of the movie takes place at MIT, portraying Nash’s years as an instructor in mathematics at the Institute, where he worked from 1951 to 1959, until mental illness curtailed his mathematical career.

Find it in the library

John Nash and his contribution to Game Theory and Economics

Distinguished Research Professor of Economics, University of Technology Sydney

Disclosure statement

John Wooders receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

University of Technology Sydney provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

A two-page paper published by John Nash in 1950 is a seminal contribution to the field of Game Theory and of our general understanding of strategic decision-making. That paper, “ Equilibrium points in N-person games ”, introduced a cornerstone concept which came to be known as Nash equilibrium .

Game theory is concerned with situations where decisions interact – where the “payoff” or reward for a decision maker depends not only on his or her own decision but also on the decisions of others.

Such situations are pervasive in real life. The payoff for a buyer in an auction, for example, depends not only on the amount he bids but also on the bids of the other buyers. If the buyer’s bid is not the highest, then he loses the auction. Likewise, the profit realised by a firm depends not only on the price it sets for its product but also on the prices set by its competitors. In a tennis match, the likelihood the server will win a point depends on whether she delivers the serve to the receiver’s left or right and whether the receiver correctly anticipates it.

Auctions, price setting and tennis are all examples of “non-cooperative” strategic interactions that mathematicians and economists refer to as “games”. They are non-cooperative because decision makers take their actions independently and are unable to enter into binding agreements with others regarding their actions, either because such agreements are illegal (when setting prices) or because they have no incentive to do so (as in tennis).

The notion of Nash equilibrium, developed in Nash’s 1950 paper, is the basis of how economists predict the outcome of strategic interactions.

Informally, a Nash equilibrium is a list of actions, one for each decision maker, such that each decision maker’s action is best for him, given the actions of the others. Such a list of actions is an equilibrium (or stable point), since no decision maker has an incentive to change his action.

Consider a driver approaching an intersection. She stops when she approaches a red light and she continues without concern when she approaches a green light. It is a Nash equilibrium when all drivers behave this way. When approaching a red light it is best to stop since the crossing traffic has a green light and will continue. When approaching a green light it is best to continue since the crossing traffic has a red light and will stop. Thus it is in each driver’s own interest to play her part in the equilibrium, given that everyone else does. No traffic cop is required.

Nash equilibrium also allows for the possibility that decision makers follow randomised strategies. Allowing for randomisation is important for the mathematics of game theory because it guarantees that every (finite) game has a Nash equilibrium.

Randomisation is also important in practice in commonly played games such as Two-up, Rock-Paper-Scissors, poker and tennis. We all know from our own experience how to play Rock-Paper-Scissors against a sophisticated opponent: play each action with equal probability, independently of the actions and outcomes in past plays. Indeed, this is exactly what Nash equilibrium predicts. Nash’s theory applies to any game with any number of decision makers, whereas John von Neumann’s 1928 Minimax Theorem applies only to “zero-sum” games with two players.

Interestingly, data collected from championship tennis matches has shown that the serve-and-return behaviour of professional players is consistent with both von Neumann’s Minimax Theory and Nash’s generalisation.

Nash’s work dealt with games in which each decision maker takes his or her action without knowing the actions taken by others, and in which no decision-maker has private information. John Harsanyi extended the notion of Nash equilibrium to deal with strategic interactions, such as in auctions, in which decision-makers have private information. (In an auction, buyers know the value they place on the item being sold, but they don’t know how other buyers value the item.)

Reinhardt Selten extended the notion of Nash equilibrium to deal with dynamic interactions, in which one or more decision-makers observe the action of another before taking their own action. In 1994, Nash shared the Nobel Prize in Economics with Harsanyi and Selten for these contributions.

While Nash is best known for his contribution to non-cooperative game theory, he also made a seminal contribution to cooperative game theory with the development of the Nash bargaining solution.

Nash’s work has had a profound impact in economics. Knowledge of game theory is essential training for every professional economist and it is a common – and popular – subject for undergraduate students as well. Nash’s work not only revolutionised modern economics, it has also had an important impact in fields as diverse as computer science, political science, sociology and biology.

His work on game theory won him a Nobel Prize for economics in 1994 and he just recently received Norway’s Abel prize for mathematics.

John Nash remained active at scientific conferences around the world. He was happy to talk with students, many of whom wanted a picture with him too. He and his wife, Alicia were both killed in a car accident on the New Jersey Turnpike on Saturday, May 24 on their way home from receiving the prize.

Both were kind people and they will be missed.

- Mathematics

- Game theory

Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

John F. Nash, Jr.

John Nash Jr., a legendary fixture of Princeton University’s Department of Mathematics renowned for his breakthrough work in mathematics and game theory as well as for his struggle with mental illness, died with his wife, Alicia, in an automobile accident May 23 in Monroe Township, New Jersey. He was 86, she was 82.

During the nearly 70 years that Nash was associated with the University, he was an ingenious doctoral student; a specter in Princeton’s Fine Hall whose brilliant academic career had been curtailed by his struggle with schizophrenia; then, finally, a quiet, courteous elder statesman of mathematics who still came to work every day and in the past 20 years had begun receiving the recognition many felt he long deserved. He had held the position of senior research mathematician at Princeton since 1995.

Nash was a private person who also had a strikingly public profile, especially for a mathematician. His life was dramatized in the 2001 film “A Beautiful Mind” in which he and Alicia Nash were portrayed by actors Russell Crowe and Jennifer Connelly. The film centered on his influential work in game theory, which was the subject of his 1950 Princeton doctoral thesis and the work for which he received the 1994 Nobel Prize in economics.

At heart, however, Nash was a devoted mathematician whose ability to see old problems from a new perspective resulted in some of his most astounding and influential work, friends and colleagues said.

At the time of their deaths, the Nashes were returning home from Oslo, Norway, where John had received the 2015 Abel Prize from the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, one of the most prestigious honors in mathematics. The prize recognized his seminal work in partial differential equations, which are used to describe the basic laws of scientific phenomena. For his fellow mathematicians, the Abel Prize was a long-overdue acknowledgment of his contributions to mathematics.

For Nash to receive his field’s highest honor only days before his death marked a final turn of the cycle of astounding achievement and jarring tragedy that seemed to characterize his life. “It was a tragic end to a very tragic life. Tragic, but at the same time a meaningful life,” said Sergiu Klainerman, Princeton’s Eugene Higgins Professor of Mathematics, who was close to John and Alicia Nash, and whose own work focuses on partial differential equation analysis.

“We all miss him,” Klainerman said. “It was not just the legend behind him. He was a very, very nice person to have around. He was very kind, very thoughtful, very considerate and humble. All that contributed to his legacy in the department. The fact that he was always present in the department, I think that by itself was very moving. It’s an example that stimulated people, especially students. He was an inspiring figure to have around, just being there and showing his dedication to mathematics.”

Princeton President Christopher L. Eisgruber said Sunday that the University community was “stunned and saddened by news of the untimely passing of John Nash and his wife and great champion, Alicia.”

“Both of them were very special members of the Princeton University community,” Eisgruber said. “John’s remarkable achievements inspired generations of mathematicians, economists and scientists who were influenced by his brilliant, groundbreaking work in game theory, and the story of his life with Alicia moved millions of readers and moviegoers who marveled at their courage in the face of daunting challenges.”

Although Nash did not teach or formally take on students, his continuous presence in the department over the past several decades, coupled with the almost epic triumphs and trials of his life, earned him respect and admiration, said David Gabai, the Hughes-Rogers Professor of Mathematics and department chair.

“John Nash, with his long history of achievements and his incredible battle with mental health problems, was hugely inspirational,” Gabai said. “It’s a huge loss not to have him around anymore.”

Gabai said the Nashes regularly attended department events such as receptions, special teas, and special dinners, and they also were very supportive of undergraduate education and regularly attended undergraduate events. Gabai, who was with the couple in Norway when John received the Abel Prize, likened their deaths to the department losing two family members.

Even in the 1970s when Nash, still struggling with mental illness, was an elusive presence known as the “Phantom of Fine Hall,” his reputation for bravely original thinking motivated aspiring mathematicians, said Gabai, who was a Princeton graduate student at the time. Nash’s creativity helped preserve the department’s emphasis on risk-taking and exploration, he said.

“In those days, he was very present, but rarely said anything and just wandered benignly through Fine Hall. Nevertheless, we all knew that the mathematics he did was really spectacular,” Gabai said. “It went beyond proving great results. He had a profound originality as if he somehow had insights into developing problems that no one had even thought about.

“I think he prided himself that he had his way of thinking about things,” Gabai continued. “He was such an extraordinary exemplar of the things that this department strives for. Beyond great originality, he demonstrated tremendous tenacity, courage and fearlessness.”

Since winning the Nobel Prize , Nash had entered a long period of renewed activity and confidence — which coincided with Nash’s greater control of his mental state — that allowed him to again put his creativity to work, Klainerman said. He met Nash upon joining the Princeton faculty in 1987, but his doctoral thesis had made use of a revolutionary method introduced by Nash in connection to the Nash embedding theorems, which the Norwegian Academy described as “among the most original results in geometric analysis of the twentieth century.”

“When he got the Nobel Prize, there was this incredible transformation,” Klainerman said. “Prior to that we didn’t realize he was becoming normal again. It was a very slow process. But after the prize he was like a different person. He was much more confident in himself.”

During their frequent talks in recent years, Nash would offer unique perspectives on numerous topics spanning mathematics and current events, Klainerman said. “Even though his mind wasn’t functioning as it did in his youth, you could tell that he had an interesting point of view on everything. He was always looking for a different angle than everybody else. He always had something interesting to say.”

Nash’s quick and distinctive mind still shone in his later years, said Michail Rassias, a visiting postdoctoral research associate in mathematics at Princeton who was working with Nash on the upcoming book, “Open Problems in Mathematics.” He and Nash had just finished the preface of their book before Nash left for Oslo. They agreed upon a quote from Albert Einstein that resonated with Nash (although Nash pointed out that Einstein was a physicist, not a mathematician, Rassias said): “Learn from yesterday, live for today, hope for tomorrow. The important thing is not to stop questioning.”

“Even at 86, his mind was still open,” Rassias said. “He still wanted to have new ideas. Of course, he couldn’t work like when he was 20, but he still had this spark, the soul of a young mathematician. The fact that he moved slowly and talked with a quiet voice had nothing to do with the enthusiasm with which he did mathematics. It was very inspirational.”

Sixty years younger than Nash, Rassias said his work with Nash began with a conversation in the Fine Hall commons room in September.

“I could tell there was mathematical chemistry between us and that led to this intense collaboration. He was very simple, very open to discussing ideas with new people if you said something that attracted his interest,” Rassias said. “Nash gave this impression that he was distant, but when you actually had the opportunity to talk to him he was not like that. He tended to walk alone, but if you got the courage to talk to him it would be very natural for him to talk to you.”

Rassias has been inspired by the enthusiasm and willingness with which a person of Nash’s stature dedicated months of his time to working with a young mathematician. It was an example Rassias hopes to emulate during his own career.

“Remembering what John Nash did for me, I will definitely try to give all my heart and soul to younger people in all steps of their careers,” Rassias said. “I also will try to keep my mind and enthusiasm for math alive to the end. That is something I will try to achieve like him.”

Born in Bluefield, West Virginia, in 1928, Nash received his doctorate in mathematics from Princeton in 1950 and his graduate and bachelor’s degrees from Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in 1948.

His honors included the American Mathematical Society’s 1999 Leroy P. Steele Prize for Seminal Contribution to Research and the 1978 John von Neumann Theory Prize. Nash held membership in the National Academy of Sciences and in 2012 was an inaugural fellow of the American Mathematical Society.

Nash is survived by his sister, Martha Nash Legg, and sons John David Stier and John Charles Martin Nash. He had his younger son, John Nash, with Alicia shortly after their marriage in 1957, which ended in divorce in 1963. They remarried in 2001.

Despite their divorce, Alicia, who was born in El Salvador in 1933, endured the peaks and troughs of Nash’s life alongside him, Klainerman said. Their deaths at the same time after such a long life together of highs and lows seemed literary in its tragedy and romance, he said.

“They were a wonderful couple,” Klainerman said. “You could see that she cared very much about him, and she was protective of him. You could see that she cared a lot about his image and the way he felt. I felt it was very moving.

“Coming home from Oslo, he must have been extremely happy, and she must have been extremely happy for him,” he continued. “They went for the apotheosis of his career, and died in this terrible way on the way back. But they were together.”

-By Morgan Kelley, Princeton University Office of Communications

John F Nash PhD

Project Details

In this page you can find Nash’s PhD thesis:

- Original document

- Transcribed into tex/pdf *

*: Thanks to Rebeca Duarte Miguel for this, and to Jeek Midford for spotting some spelling mistakes.

Others form category

List of Experimental Economic Labs of the world

Game Theory Online Tools

Game Theory Society

Experiments on SciOn

Game Theory Nobelists

Software for Experiments

Online courses about Game Theory

GT in the media

Top 10 Game Theorists on Google Scholar

ETH Controversies Workshops

Modellbildung: Game theory and strategic interaction

Game Theory Movie

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

John Nash's Dissertation. Non-cooperative Games, May 1950, is available in PDF format Non-Cooperative_Games_Nash.pdf.The dissertation is provided for research use only. [Note: Chapter 6 of The Essential John Nash, edited by Harold W. Kuhn and Sylvia Nasar (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2001) contains a facsimile of Nash's 1950 Ph.D. dissertation on non-cooperative games.]

Title: Nash.pdf Created Date: 12/11/2001 4:05:15 PM

The work of John F. Nash Jr. in game theory. HW Kuhn, JC Harsanyi, R Selten, JW Weibull, E van Damme. 25. 1994. The agencies method for modeling coalitions and cooperation in games. JF Nash Jr. International Game Theory Review 10 (04), 539-564. , 2008. 20.

When John Nash wrote "Non Cooperative Games," his Ph.D. dissertation at Princeton in 1950, the text of his thesis ( read it online) was brief. It ran only 26 pages. And more particularly, it was light on citations. Nash's diss cited two texts: John von Neumann & Oskar Morgenstern's Theory of Games ...

We would like to show you a description here but the site won't allow us.

John Forbes Nash, Jr. (June 13, 1928 - May 23, 2015), known and published as John Nash, was an American mathematician who made fundamental contributions to game theory, real algebraic geometry, differential geometry, and partial differential equations. Nash and fellow game theorists John Harsanyi and Reinhard Selten were awarded the 1994 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics.

John Forbes Nash, an exalted mathematician whose life took dramatic turns between genius, mental illness and celebrity status, made major contributions to game theory, geometry and the field of ...

NON-COOPERATIVE GAMES. JOHN NASH. (Received October 11, 1950) Introduction. Von Neumann and Morgenstern have developed a very fruitful theory of two-person zero-sum games in their book Theory of Games and Economic Be- havior. This book also contains a theory of n-person games of a type which we would call cooperative.

Nash's work; see Leonard (1994), Kuhn (1994), Milnor (1995), Rubinstein (1995), van Damme and Weibull (1995), Myerson (1996), and Binmore's introduction to the collected game-theory papers of Nash (1996). A detailed biography of John Nash has been written by Sylvia Nasar (1998). In this paper, to show how Nash's work was a major turning-point ...

Abstract. John F. Nash, Jr., submitted his Ph.D. Dissertation entitled Non-cooperative games to Princeton University in 1950. Read it 58 years later, and you will find the germs of various later developments in game theory. Some of these are presented below, followed by a discussion concerning dynamic aspects of equilibrium.

The work of John Nash in game theory. E. Damme, H. Kuhn, +4 authors. P. Hammerstein. Published 1995. Economics. TLDR. This research presents a meta-analyses of the evolutionary history of decision-making in response to the crisis of confidence in the 1970s and its consequences. Expand.

John F. Nash, Jr., submitted his Ph.D. dissertation entitled Non-Cooperative Games to Princeton University in 1950. Read it 58 years later, and you will find the germs of various later developments in game theory. Some of these are presented below, followed by a discussion concerning dynamic aspects of equilibrium.

His doctoral dissertation, "Non-Cooperative Games," was a mere 28 pages but laid the groundwork for modern game theory. The Nash equilibrium, a concept introduced in this work, transformed the understanding of decision-making processes in economics, where multiple actors with conflicting interests are involved.

Science. 19 Jun 2015. Vol 348, Issue 6241. p. 1324. DOI: 10.1126/science.aac7085. On 23 May, John Nash and his wife Alicia were killed in a car accident in New Jersey. This tragedy came just after he received, at age 86, yet another distinguished award. John's contributions were in pure mathematics and game theory, which continues to influence ...

At Princeton, John Nash began working on Game Theory with John von Neumann and Harold Kuhn, while his supervisor was Albert Tucker. ... In his doctoral dissertation at Princeton, Nash worked further on his idea of non-cooperative equilibrium. Most of his dissertation was published in the Annals of Mathematics.

The foundational game theory work of mathematician John von Neumann and economist Oskar Morgenstern, published in 1944, provided a framework for solutions to zero-sum games, where one player's win was the other's loss. ... Nash, in his dissertation research at Princeton (published in this and three other papers), ...

A two-page paper published by John Nash in 1950 is a seminal contribution to the field of Game Theory and of our general understanding of strategic decision-making. That paper, " Equilibrium ...

2015. John Nash Jr., a legendary fixture of Princeton University's Department of Mathematics renowned for his breakthrough work in mathematics and game theory as well as for his struggle with mental illness, died with his wife, Alicia, in an automobile accident May 23 in Monroe Township, New Jersey. He was 86, she was 82.

John Forbes Nash, Jr., died on May 23, 2015 in a car crash. He was returning from Norway, where he had been ... The state of game theory when Nash went to the Princeton Mathematics Department to do his Ph.D. in 1948: ... Noncooperative Games, Ph.D. Dissertation Princeton, 1950, and Annals of Mathematics 1951 (announced in

Length: 50 pic 3 pts, 212 mm. Journal of Economic Theory ET2148. journal of economic theory 69, 153 185 (1996) The Work of John Nash in Game Theory. Nobel Seminar, December 8, 1994 The document that follows is the edited version of a Nobel Seminar held December 8, 1994, and is devoted to the contributions to game theory of John Nash.

John Nash (born June 13, 1928, Bluefield, West Virginia, U.S.—died May 23, 2015, near Monroe Township, New Jersey) was an American mathematician who was awarded the 1994 Nobel Prize for Economics for his landmark work, first begun in the 1950s, on the mathematics of game theory.He shared the prize with John C. Harsanyi and Reinhard Selten.In 2015, Nash won (with Louis Nirenberg) the Abel ...

In game theory, the Nash equilibrium is the most commonly-used solution concept for non-cooperative games. ... In his Ph.D. dissertation, John Nash proposed two interpretations of his equilibrium concept, with the objective of showing how equilibrium points can be connected with observable phenomenon. ...

John F Nash PhD. Project Details. In this page you can find Nash's PhD thesis: Original document; Transcribed into tex/pdf* *: Thanks to Rebeca Duarte Miguel for this, and to Jeek Midford for spotting some spelling mistakes. Documents ... ETH - GAME THEORY 2017. Heinrich H Nax