PhD Program Rankings (Adapted from US News and World Report)

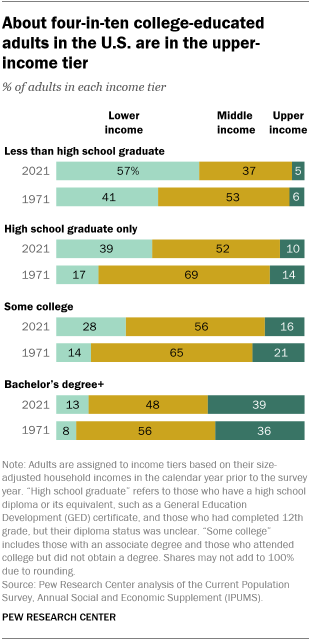

Below are reputation scores and ranks of the top 27 PhD programs in Psychology, including top-ranked schools in each of six subspecialties. From US News and World Report, “America’s Best Graduate Schools” rank/school average reputation score.

Rank School Average reputation score

1 Stanford Univ. 4.8

2 Univ. of California-Berkeley 4.6

2 Univ. of Michigan-Ann Arbor 4.6

4 Univ. of Illinois-Urbana-Champaign 4.5

4 Yale Univ. 4.5

6 Harvard Univ. 4.4

6 Univ. of California-Los Angeles 4.4

6 Univ. of Minnesota-Twin Cities 4.4

9 Carnegie Mellon Univ. 4.2

9 Princeton Univ. 4.2

9 Univ. of Pennsylvania 4.2

9 Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison 4.2

13 Indiana Univ.-Bloomington 4.1

13 Univ. of California-San Diego 4.1

13 Univ. of North Carolina-Chapel Hill 4.1

16 Johns Hopkins Univ. 4.0

16 Univ. of Colorado-Boulder 4.0

16 Univ. of Texas-Austin 4.0

19 Cornell Univ. 3.9

19 Duke Univ. 3.9

19 Northwestern Univ. 3.9

19 Univ. of Chicago 3.9

19 Univ. of Washington 3.9

24 Columbia Univ. 3.8

24 Ohio State Univ. 3.8

24 Univ. of California-Irvine 3.8

24 Univ. of Virginia 3.8

Top Specialty Programs

C linical Psychology

1. Univ. of Minnesota-Twin Cities

2. Univ. of Illinois-Urban a-Champaign

3. Univ. of Michigan-Ann Arbor

4. Univ. of California-Los Angeles

5. Univ. of Washington

Co unseling Psychology

1. Univ. of Maryland-College Park

2. Ohio State Univ.

3. Univ. of Minnesota-Twin Cities

4. Univ. of Missouri-Columbia

5. Univ. of Iowa

Developme n tal

2. Univ. of Virginia

2. Stanford Univ.

4. Univ. of Michigan-Ann Arbor

5. Univ. of Illinois-Urban a-Champaign

5. Univ. of California-Berkeley

Expe ri menta l P sychology

1. Stanford Univ.

2. Univ. of Michigan-Ann Arbor

3. Univ. of California-Berkeley

4. Univ. of Illinois-Urban a-Champaign

5. Carnegie Mellon Univ.

I ndustrial / Organizational

2. Univ. of Maryland-College Park

3. Michigan State Univ.

4. Ohio State Univ.

5. Bowling Green State Univ.

5. Univ. of Illinois-Urbana-Champaign

Schoo l Psychology

1. Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison

2. Univ. of Texas-Austin

3. Univ. of South Carolina-Columbia

3. Univ. of Nebraska-Lincoln

3. Columbia Univ.

(The response rate for psychology was 34%, the lowest response rate for the six PhD fields surveyed. Political Science had the highest response rate, at 54%.)

Reprinted with permission from US News and World Report. Copyright, 1995, US News and World Report.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

New Report Finds “Gaps and Variation” in Behavioral Science at NIH

A new NIH report emphasizes the importance of behavioral science in improving health, observes that support for these sciences at NIH is unevenly distributed, and makes recommendations for how to improve their support at the agency.

APS Advocates for Psychological Science in New Pandemic Preparedness Bill

APS has written to the U.S. Senate to encourage the integration of psychological science into a new draft bill focused on U.S. pandemic preparedness and response.

APS Urges Psychological Science Expertise in New U.S. Pandemic Task Force

APS has responded to urge that psychological science expertise be included in the group’s personnel and activities.

Privacy Overview

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Getting a Ph.D. in Psychology

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Verywell / Evan Polenghi

Ph.D. vs. Psy.D.

Job opportunities, earning a degree, specialty areas, alternatives.

Getting a Ph.D. in psychology can open up a whole new world of career opportunities. For many careers paths in psychology-related career paths, a doctoral degree is necessary to obtain work and certification. A Ph.D. is one option, but it is not the only educational path that's available to reach some of these goals.

A Ph.D., or doctor of philosophy, is one of the highest level degrees you can earn in the field of psychology . If you're considering pursuing a graduate degree, you might be wondering how long it takes to earn a Ph.D. in psychology . Generally, a bachelor's degree takes four years of study. While a master's degree requires an additional two to three years of study beyond the bachelor's, a doctoral degree can take between four to six years of additional graduate study after earning your bachelor's degree.

Recently, a new degree option known as the Psy.D. , or doctor of psychology, has grown in popularity as an alternative to the Ph.D. The type of degree you decide to pursue depends on a variety of factors, including your own interests and your career aspirations.

Before deciding which is right for you, research your options and decide if graduate school in psychology is even the best choice for you. Depending on your career goals, you might need to earn a master's or doctoral degree in psychology in order to practice in your chosen field. In other instances, a degree in a similar subject such as counseling or social work may be more appropriate.

A doctorate in psychology is required if you want to open your own private practice.

If you want to become a licensed psychologist, you must earn either a Ph.D. or a Psy.D. in clinical or counseling psychology.

In most cases, you will also need a doctorate if you want to teach and conduct research at the college or university level. While there are some opportunities available for people with a master's degree in various specialty fields, such as industrial-organizational psychology and health psychology , those with a doctorate will generally find higher pay, greater job demand, and more opportunity for growth.

In order to earn a Ph.D. in psychology, you need to first begin by earning your bachelor's degree. While earning your undergraduate degree in psychology can be helpful, students with bachelor's degrees in other subjects can also apply their knowledge to psychology Ph.D. programs . Some students in doctorate programs may have a master's degree in psychology , but most doctorate programs do not require it.

After you’ve been admitted to a graduate program, it generally takes at least four years to earn a Ph.D. and another year to complete an internship. Once these requirements have been fulfilled, you can take state and national exams to become licensed to practice psychology in the state where you wish to work.

Once you enter the graduate level of psychology, you will need to choose an area of specialization, such as clinical psychology , counseling psychology, health psychology, or cognitive psychology . The American Psychological Association (APA) accredits graduate programs in three areas: clinical, counseling, and school psychology. If you are interested in going into one of these specialty areas, it's important to choose a school that has received accreditation through the APA.

For many students, the choice may come down to a clinical psychology program versus a counseling psychology program. There are many similarities between these two Ph.D. options, but there are important distinctions that students should consider. Clinical programs may have more of a research focus while counseling programs tend to focus more on professional practice. The path you choose will depend largely on what you plan to do after you complete your degree.

Of course, the Ph.D. in psychology is not the only graduate degree option. The Psy.D. is a doctorate degree option that you might also want to consider. While there are many similarities between these two degrees, traditional Ph.D. programs tend to be more research-oriented while Psy.D. programs are often more practice-oriented.

The Ph.D. option may be your top choice if you want to mix professional practice with teaching and research, while the Psy.D. option may be preferred if you want to open your own private psychology practice.

In the book "An Insider's Guide to Graduate Programs in Clinical and Counseling Psychology," authors John C. Norcross and Michael A. Sayette suggest that one of the key differences between the two-degree options is that the Ph.D. programs train producers of research while Psy.D. programs train consumers of research. However, professional opportunities for practice are very similar with both degree types.

Research suggests that there are few discernible differences in terms of professional recognition, employment opportunities, or clinical skills between students trained in the Ph.D. or Psy.D. models. One of the few differences is that those with a Ph.D. degree are far more likely to be employed in academic settings and medical schools.

Social work, counseling, education, and the health sciences are other graduate options that you may want to consider if you decide that a doctorate degree is not the best fit for your interests and career goals.

A Word From Verywell

If you are considering a Ph.D. in psychology, spend some time carefully researching your options and thinking about your future goals. A doctoral degree is a major commitment of time, resources, and effort, so it is worth it to take time to consider the right option for your goals. The Ph.D. in psychology can be a great choice if you are interested in being a scientist-practitioner in the field and want to combine doing research with professional practice. It's also great training if you're interested in working at a university where you would teach classes and conduct research on psychological topics.

University of Pennsylvania; School of Arts and Sciences. Information for applicants .

American Psychological Association. Doctoral degrees in psychology: How are they different, or not so different?

U.S. Department of Labor. Psychologists . Occupational Outlook Handbook .

Norcross JC, Sayette MA. An Insider's Guide to Graduate Programs in Clinical and Counseling Psychology (2020/2021 ed.) . New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2020.

Davis SF, Giordano PJ, Licht CA. Your Career in Psychology: Putting Your Graduate Degree to Work . John Wiley & Sons; 2012. doi:10.1002/9781444315929

US Department of Education. Bachelor's, master's, and doctor's degrees conferred by postsecondary institutions, by sex of student and discipline division: 2016-17 .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Utility Menu

Psychology Graduate Program

- Psychology Department

- Resources for Applicants

PPREP (Prospective Ph.D. & RA Event in Psychology) - an informational event for individuals interested in pursuing research positions and/or doctorates in psychology

PRO-TiP (PhD Resources and Online Tips Page) - provides insight into what constitutes a strong application and address questions that frequently come up each year

GENERAL RESOURCES

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Graduate study in psychology .

Psychology Grad School Wiki for Prospective Psych Grad Students. (n.d.). 2021 psychology grad school positions .

GRE RESOURCES

Educational Testing Service. (n.d.). GRE fee reduction program .

Educational Testing Service. (n.d.). GRE General Test at home .

Educational Testing Service. (n.d.). Prepare for the GRE General Test .

CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY-SPECIFIC RESOURCES

Prinstein, M. (2017). Mitch’s uncensored advice for applying to graduate school in clinical psychology .

US and Canada Clinical/Counseling Psych PhD GRE Requirements (Google Sheet)

- FAQ for Applicants

Best Psychology Schools

Ranked in 2022, part of Best Social Sciences and Humanities Schools

Studying the intricacies of the

Studying the intricacies of the human experience is central to a psychology program. With a graduate degree, psychologists are able to work in health facilities, schools and the government. These are the top psychology programs. Each school's score reflects its average rating on a scale from 1 (marginal) to 5 (outstanding), based on a survey of academics at peer institutions. Read the methodology »

- Clear Filters

PhD Admission FAQ

General Information

When is the application due and how do i apply .

NOW CLOSED- The application is due on November 30, 2023 at 11:59 PM Pacific Time.

Apply using the application portal .

How long does it take to get a PhD in Psychology at Stanford?

The PhD program is designed to be completed in five years of full-time study. Actual time will depend on students' prior background, progress, and research requirements. The minimum residency requirement for the PhD degree is 135 units of completed coursework and research units.

What are the requirements for the PhD degree in Psychology?

Please consult the PhD Requirements page .

What are the different subfields within the graduate program in Psychology?

- Affective Science

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Neuroscience

- Social Psychology

What is the Department's teaching requirement?

PhD students must complete at least five quarters of teaching assistantship (TA) under the supervision of a faculty member. Students are required to attend a TA training workshop in their second year. In addition, students are encouraged to take advantage of department and university teacher training programs. Students for whom English is a second language are expected to acquire sufficient fluency in English. All international students must be approved by Stanford’s EFS department .

How many students apply to the Stanford Psychology PhD? How many are admitted? What are the demographics?

Stanford provides public reports with summary data about graduate programs and graduate admissions. Please consult the public dashboards published by Stanford's office of Institutional Research & Decision Support on doctoral admissions , doctoral enrollment and demographics , and doctoral completion and time-to-degree .

Is there a standalone Master of Arts program in Psychology?

The Department of Psychology does not offer a terminal Master’s degree program. Current doctoral students within the Department or in another Stanford graduate program may apply to be awarded a Master of Arts in Psychology during the course of their PhD program.

Does your department have a program in Clinical Psychology? Are you accredited by the APA?

No. Our department does not have a program in Clinical Psychology. As such, we are not accredited by the APA.

Do you have any advice about getting into grad school?

The Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences offers an online resource for prospective graduate school applicants: Guide on Getting Into Grad School . We encourage applicants to take advantage of this resource.

Financial Support

What is the annual cost of attending your program.

All students admitted to the Psychology PhD program receive five years of 12-month funding. Financial support is provided through a combination of fellowship stipend and salary, and assistantship salary and tuition allowance. Information about the cost of attendance and funding options are available from the Financial Aid Office .

What type of financial support do you offer?

All students admitted to the Psychology PhD program receive five years of 12-month funding. Financial support is provided through a combination of fellowship stipend and salary, and assistantship salary and tuition allowance. Funding is contingent upon satisfactory academic progress. Students are encouraged to pursue fellowships offered by the University and by national organizations, such as the National Science Foundation.

Stanford University also offers the Knight-Hennessy Scholars program, designed to build a multidisciplinary community of Stanford graduate students dedicated to finding creative solutions to the world's greatest challenges. The program awards up to 100 high-achieving students every year with full funding to pursue graduate education at Stanford, including the PhD in Psychology. To be considered, you must apply to Knight-Hennessy Scholars and separately apply to the Psychology Department. Note that the Knight-Hennessy Scholars program application deadline is in the spring before the autumn application cycle.

Do you offer support for the summer months?

Yes, funding is offered for 12 months a year for 5 full years, including 5 summers.

Preparing for Admission

Am i eligible to apply if my undergraduate major is not in psychology.

An undergraduate major in Psychology is not required; applicants from other backgrounds can apply and be admitted. All applicants should have sufficient foundational knowledge and research experience prior to the program to allow them to go straight into graduate-level coursework and conduct research.

My undergraduate degree was completed outside the United States. Is my degree eligible?

Please refer to the Stanford Graduate Admission Office's table of minimum level requirements for international academic credentials . These credential requirements are set by the University and nonnegotiable.

If I have prior graduate work, can it be transferred to the PhD program?

No, the Department of Psychology does not allow the transfer of unit credits from your previous program.

How competitive is admission to the PhD program?

Admission to our program is highly competitive. About 10-15 admits enter the program each year and are chosen from a pool of over 600 applicants. These students are selected on the basis of a strong academic background as demonstrated by previous coursework, research experience, and letters of recommendation. Please be assured that the Department reviews each application very carefully and makes decisions on an individual basis.

The Application Process

How do i apply.

Please visit the PhD Admissions page for instructions on how to apply to the Psychology PhD Program, graduate application requirements, and the link to the online application.

Is there an application fee? If so, can I apply for a fee waiver?

The fee to apply for graduate study at Stanford is $125, see Application Fee . Fee waivers are available for some applicants. Please visit Graduate Admissions for information on applying for an Application Fee Waiver .

Can I submit another application to a different department within the University?

You may only apply to one degree program per academic year. However, you may apply concurrently to one departmental program and to a professional school program (law, medicine, or business).

I'm interested in the joint JD/PhD in Law and Psychology - how does it work?

Students interested in the JD/Ph.D. joint degree must apply and gain entrance separately to the School of Law and the Psychology Ph.D. program. Additionally, students must secure permission from each degree program to pursue the joint degree. Interest in both degrees should be noted on the student’s admissions applications and may be considered by the admissions committee of each program. Alternatively, an enrolled student in either the Law School or the Psychology department may apply to add the other degree and undertake the joint degree program, preferably during their first year of study. Students participating in the JD/Ph.D. joint degree program are not eligible to transfer and receive credit for a masters, or other degree, towards the Psychology Ph.D.

Students interested in the MPP/Ph.D. joint degree must apply and gain entrance to the Public Policy program’s MPP degree and the Psychology Ph.D. program. Students should note their interest in both degrees on their graduate admissions applications. Additionally, students must secure permission from each degree program to pursue the joint degree

Which faculty are accepting new students this year?

All active faculty are potentially accepting new students each year. In your application, we ask you to list the top 3 faculty you are most interested in working with. Multiple readers will review your application in full regardless of who you list.

My institution does not report GPAs on a 4.0 grading scale. How should I report my GPA on the application?

Please do not convert your GPA to a 4.0 grading scale. You should enter “0.00” for the GPA and use the “Unconverted GPA” and “Unconverted GPA System” fields instead. A link to detailed instructions for reporting GPA is located near these fields on the application.

I attended multiple undergraduate institutions. In what order should I list them on the application?

The institution where you earned or expect to earn your Bachelor's degree should be listed as "Post-Secondary Institution 1." The remaining institutions don’t have to follow a particular order. List all institutions that were attended for at least one full academic year. Please note that you must submit a transcript for all courses taken towards your undergraduate degree, including those from your nonprimary institutions.

When should I submit my transcripts if my degree will still be in progress at the time of the application deadline?

The most current version of your unofficial transcript must be submitted as part of your electronic application, even if the grades from your fall term are not available. The absence of these grades will have no impact on the review of your application. If you are admitted and enrolled, we will ask you to submit your final transcript showing all grades and proof of degree conferral.

Should I submit official transcripts?

At the time of your initial application, please only submit your unofficial transcripts. Submit the unofficial transcripts as part of your electronic application, per the instructions in the application portal. A short list of applicants who move forward to the next stage of the review process will be contacted with instructions for submitting official transcripts at a later stage.

It may be helpful to understand the difference. Unofficial transcripts are transcripts issued by your college or university directly to you, the student, which you then submit to Stanford for review. Official transcripts are transcripts issued by your college or university directly to Stanford University, usually by secure electronic transfer and sometimes in hard copy in signed and sealed envelopes. The key difference is that an official transcript has never been directly handled by the applicant.

Do you have a minimum GPA score?

We do not require applicants to have a minimum GPA for consideration, and we do not release information about the average GPAs of accepted students. As a guideline, successful applicants typically earn undergraduate cumulative GPAs among the top of their class. However, please keep in mind that admission to our graduate program depends on a combination of factors, and all areas of a student’s application are weighed similarly when applications are reviewed. If our research areas meet your educational goals, we encourage you to submit an application.

May I contact the faculty directly during the application process?

Applicants are not prohibited from reaching out to faculty directly during the application cycle. However, please understand that our faculty are extremely busy, and it is quite possible that you will receive either a very short response or no response at all. This does not mean the faculty are not interested in your application. All applications will be read and reviewed in full during the formal review process. Note that per Department policy, all faculty are potentially accepting graduate students in any given cycle, so you do not need to contact faculty in advance to see if that specific mentor is accepting students for the coming year.

Can I meet with Department staff either by phone or email before I apply to discuss my application materials or ask general questions about the program?

No, the Department staff do not have meetings with or provide individualized advising for prospective applicants. Please understand that this is a matter of bandwidth and equity. We do not have the ability to offer personalized service to all interested applicants, so we do not offer them at all. By Department policy, our staff do not provide any evaluative feedback on prospective applicants' materials, so please do not contact us with CVs, academic histories, etc to request feedback or ask about odds for acceptance. For support in crafting your application, we recommend that you turn to your existing network of mentors (e.g., your letter writers) and/or the resources offered by your current or prior academic institution(s).

TOEFL and GRE

Is the general gre required is the subject gre required.

No, the Stanford Psychology PhD program does not require the general GRE or the subject GRE. We will not be collecting any information related to GRE exam scores on the application. Please do not submit GRE scores to Stanford for our program.

What is the TOEFL exam, and am I required to take it?

The TOEFL is a standardized test of English language proficiency. Per University policy, the TOEFL exam is required for international, non-native English speakers who apply to any Stanford graduate program.

The TOEFL score requirements are waived for international non-native English speakers who have received a Bachelor’s or Master’s degree from an institution in the United States or another English-speaking country. Therefore, applicants with these degrees from the U.S., Australia, Canada (except Quebec), New Zealand, Singapore, Ireland, and the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, Wales) are exempt from taking the TOEFL and do not need to submit the TOEFL waiver request form.

When should I take the TOEFL?

The TOEFL must be taken by the published application deadline.

What is the minimum TOEFL score required for admission?

Please visit the website of Stanford's Office of Graduate Admissions for more information on the University’s minimum requirements.

If my TOEFL score falls below the University’s minimum, am I still eligible to apply?

Yes, you may still apply. If your TOEFL scores fall below the University's minimum requirements and you are admitted, Stanford may require you to take an English placement exam and/or English classes.

May I submit the IELTS instead of the TOEFL to demonstrate English proficiency?

The IELTS is not accepted at Stanford University; only the TOEFL is accepted to provide proof of proficiency in English.

How do I request a TOEFL exemption or waiver?

For all questions related to TOEFL exemptions or waivers please refer to the website of Stanford’s Office of Graduate Admissions . Please note that the central office makes all final decisions regarding TOEFL waivers; the Department of Psychology is not involved in the approval of TOEFL waivers.

How do I check the status of my TOEFL scores?

Log in to your application account. It may take up to two weeks after submitting your application or sending the scores (whichever occurs later) for your official scores to show as received. Processing may be delayed or halted if the name or birthdate on the score report does not exactly match the information on your application.

Why does my TOEFL status show as “Not Applicable” even though I submitted a TOEFL score?

This may be because you listed English as your first language in the application. Please note that “first language” refers to your native language.

Is there a department code for ETS to use in order to send in my scores?

No, there are no individual department code. Use the Stanford University score recipient code 4704 to send your TOEFL scores.

Statements of Purpose

How long should my statement of purpose be.

We strongly recommend that your statement of purpose be around two pages in length.

What should I include in my statement of purpose?

Please consult the Stanford Graduate Admissions FAQ page for more information on the Statement of Purpose.

Letters of Recommendation

When are the letters of recommendation due.

The letters of recommendation have the same deadline as the rest of the application. This year, the deadline is November 30, 2023.

How many recommendations do I need, and who should I ask to be my recommenders?

Applicants need three recommendations from faculty or others qualified to evaluate your potential for graduate study. At least one evaluation and letter should be from a faculty member at the last school you attended as a full-time student (unless you have been out of school for more than five years). Substitutions for faculty recommendations may include work associates or others who can comment on your academic potential for graduate work.

My recommender will not be able to submit his/her letter by the application deadline. Will my application still be considered?

Letters of recommendation must be submitted by the application deadline. As such, we strongly encourage you to contact your recommenders directly to remind them of our deadline. If your recommender misses the deadline, please contact psych-admissions [at] stanford.edu (psych-admissions[at]stanford[dot]edu) . Depending on the circumstances, Department staff may collect the letter via email and forward it to the faculty to add to your file. That said, the program expects applicants to do everything possible to ensure that letters are submitted on time via the secure online system.

Can my recommenders submit their letters via email, fax, or postal service?

No. Recommenders must submit their letters via Stanford’s online recommender system.

My recommenders are having technical difficulties with the online letters of recommendation process. Who should they contact?

Should any of your recommenders experience technical difficulties with the online letters of recommendation process, please refer them to our application database provider's letters of recommendation help page or have them submit a Help Request Form directly to our application database provider.

Additional Materials and Updates

I realized i made a mistake on my application and/or uploaded the wrong version of my documents. what do i do.

Depending on the timing and the nature of the error, our staff may be able to correct your application. Please send an email to psych-admissions [at] stanford.edu (psych-admissions[at]stanford[dot]edu) . Include your full name, a complete description of the error, and attach the correct version of the file (if applicable). The Department reserves the right to decline to update your application after the deadline has passed. Requests will be reviewed on a case-by-case basis.

If you need to change your recommenders, please use the Activity Status Page. Note: The order of recommenders cannot be changed.

May I submit a resume/CV, list of publications, etc. as part of my application?

Applicants are permitted to upload one additional document to the online application, under the “Document Uploads” section.

Is there an interview process?

Yes, our faculty interview prospective students before making final admission decisions.

When are the interviews?

The interviews for the current admissions cycle are likely to be in February 2021. We anticipate that all interviews will take place virtually.

When can I expect to find out the decision on my application?

The Department of Psychology aims to issue all offers of admission to PhD degree applicants by the end of March.

I applied in a prior cycle and was not admitted. Can I apply again?

Applicants who applied in prior cycles and were previously not admitted are welcome to reapply if they can demonstrate significant progress made since they last applied. We encourage you to use your Statement of Purpose to explain this progress.

All documents must be resubmitted with a new application. We do not keep records from past applications.

I still have questions!

If you have questions that are not answered on this page or the Stanford Graduate Admissions FAQ page , please email psych-admissions [at] stanford.edu (psych-admissions[at]stanford[dot]edu) . If your questions are already covered on this page, your email may not receive a response.

Note that our Department staff are experts on the logistics and administration of the application, but do not answer questions related to research topics or faculty fit. Per Department policy, Department staff will not offer any evaluative feedback on application materials or applicants' academic background. Unfortunately, due to the extremely high volume of inquiries, we cannot provide individual status updates for applicants at any point in the process.

The Best Online Doctorate in Psychology Programs

Staff Writers

Contributing Writer

Learn about our editorial process .

Updated April 19, 2024

thebestschools.org is an advertising-supported site. Featured or trusted partner programs and all school search, finder, or match results are for schools that compensate us. This compensation does not influence our school rankings, resource guides, or other editorially-independent information published on this site.

Are you ready to discover your college program?

A Ph.D in psychology prepares graduates for careers as licensed psychologists, research psychologists, and psychology professors. Doctoral students examine human behavior, social interactions, and mental health treatments. The degree also incorporates practical training through a supervised internship or practicum, helping students develop the skills needed for careers in psychology.

With a psychology degree , graduates can work many different psychology jobs . For example, psychologists earn a median annual salary of over $92,740, and a doctorate meets the requirements for most careers in this field.

Our list includes the top psychology programs offering some online coursework. It is important to note that while several doctorate in psychology programs offer online courses, there are no fully online psychology doctoral programs accredited by the American Psychological Association (APA). Thus, rather than ranking schools, we list these programs alphabetically to help prospective applicants find the program that best matches their needs.

This article also explores the differences between Ph.D. and Psy.D. degrees, common courses and specialization options, and careers for graduates who earn doctorates in psychology.

Featured Online Schools

The best doctoral psychology programs available online.

We use trusted sources like Peterson's Data and the National Center for Education Statistics to inform the data for these schools. TheBestSchools.org is an advertising-supported site. Featured or trusted partner programs and all school search, finder, or match results are for schools that compensate us. This compensation does not influence our school rankings, resource guides, or other editorially-independent information published on this site. from our partners appear among these rankings and are indicated as such.

#1 The Best Online Doctorate in Psychology Programs

California Southern University

- Costa Mesa, CA

The doctor of psychology program at California Southern University offers an online option for doctoral students. Degree-seekers benefit from flexible course options through the private institution. Doctoral students conduct research and participate in academic conferences.

The 66-credit doctoral program incorporates advanced psychology coursework. After passing comprehensive examinations, doctoral candidates spend 1-2 years researching and writing their dissertation. With a doctorate in psychology, professionals work in academia, research, and leadership roles.

Doctoral students pay for the program with federal financial aid, fellowships, and scholarships. Contact the psychology program to learn more about doctoral admission requirements.

California Southern University at a Glance:

Accepts Transfer Credits: Accepted

#2 The Best Online Doctorate in Psychology Programs

Fielding Graduate University

- Santa Barbara, CA

- Online + Campus

Doctoral students seeking an online psychology program benefit from the Ph.D. in clinical psychology program at Fielding Graduate University. The private university provides flexible enrollment options to meet the needs of diverse degree-seekers. Doctoral students conduct research and participate in academic conferences.

The doctoral program includes a rigorous curriculum in psychology. Doctoral candidates advance in the program by passing comprehensive exams and writing an original dissertation. Graduates with a doctorate pursue roles in research, academia, and leadership.

Online doctoral students can pay for their degree with scholarships, fellowships, and other forms of financial aid. Reach out to the program to learn more about the application process and start dates.

Fielding Graduate University at a Glance:

Online Student Enrollment: 944

Online Master's Programs: 2

Graduate Tuition Rate: $17,292

#3 The Best Online Doctorate in Psychology Programs

Southern California Seminary

- El Cajon, CA

The doctor of psychology program at Southern California Seminary offers an online option for doctoral students. At the private university, degree-seekers participate in virtual classrooms to earn a doctorate. Doctoral students work closely with faculty mentors and career advisors.

In the online psychology program, graduate learners complete advanced classes. After passing comprehensive examinations, doctoral candidates begin working on an original dissertation project. A doctorate in psychology prepares graduates for careers in academia, research, and leadership.

Online doctoral students at the accredited institution qualify for several forms of financial aid. Prospective applicants can contact the program to learn more about the enrollment process and start dates.

Southern California Seminary at a Glance:

Online Student Enrollment: 130

Student-to-Faculty Ratio: 8-to-1

Graduate Tuition Rate: $15,588

#4 The Best Online Doctorate in Psychology Programs

The Chicago School of Professional Psychology

- Chicago, IL

The online Ph.D. in international psychology program at The Chicago School of Professional Psychology ranks among the best in the field. At the private university, degree-seekers participate in virtual classrooms to earn a doctorate. Doctoral students receive library access, research support, and career services.

During the online program, learners take doctoral courses to earn their degree. The psychology program also requires passing scores on a comprehensive examination and the successful defense of an original dissertation project. With a doctorate in psychology, professionals work in academia, research, and leadership roles.

Doctoral students attending the accredited institution online qualify for several forms of financial aid. Reach out to the program to learn more about transfer credit policies, research support, and admission requirements.

The Chicago School of Professional Psychology at a Glance:

Student-to-Faculty Ratio: 4-to-1

Graduate Tuition Rate: $20,610

#5 The Best Online Doctorate in Psychology Programs

Touro University Worldwide

- Los Alamitos, CA

The doctor of psychology in human and organizational psychology program at Touro University Worldwide offers an online option for doctoral students. Thanks to a flexible format, the private institution makes it easier to complete a doctorate. Doctoral students benefit from support services like career advising.

The online program requires doctoral coursework. After passing comprehensive examinations, doctoral candidates conduct research for their dissertation. As the terminal degree in psychology, the doctoral program trains graduates for roles in academia, research, and industry.

At the accredited institution, online doctoral students qualify for scholarships, federal loans, and other forms of financial aid. Reach out to the program to learn more about transfer credit policies, research support, and admission requirements.

Touro University Worldwide at a Glance:

Online Student Enrollment: 1,903

Online Master's Programs: 8

Online Doctoral Programs: 1

Student-to-Faculty Ratio: 11-to-1

Graduate Tuition Rate: $9,000

Online Doctorate in Psychology Programs Ranking Guidelines

We selected these degree programs based on quality, curricula, school awards, rankings, and reputation.

What Is an Online Ph.D. in Psychology?

Doctoral degrees in psychology cannot be conducted completely online. However, some programs do make some coursework available to learners online, helping them complete their graduate studies from anywhere.

The typical curricula for a Ph.D. in psychology emphasizes research and prepares graduates for academic and research roles. Doctoral students take courses in research design and methods, psychology statistics, and cognitive development. Ph.D. programs also offer specialized coursework in neuroscience and affective science.

A Ph.D. in psychology builds strong research and analytical skills. In addition to coursework, each doctoral student must pass a comprehensive examination and conduct research within their specialization. The degree culminates in an original doctoral dissertation that contributes to the field of psychology. After graduation, professionals with Ph.D. degrees in psychology typically work as psychology professors or researchers.

Earning a Ph.D in psychology typically takes 5-7 years, depending on the program and whether the doctoral student completes an internship. Applicants generally need a master's degree in psychology and a strong GPA to gain admission. Some Ph.D. programs in psychology offer fellowships and other forms of funding for doctoral students.

What Is an Online Psy.D. in Psychology?

As with the online Ph.D. in psychology, an online Psy.D. in psychology refers to a doctorate in psychology program where some but not all coursework is offered online. A Psy.D. degree trains graduates for clinical roles and licensure as psychologists. Common courses include psychology research methods, psychopharmacology, and psychological testing. Doctoral students also examine research in evidence-based practice. Online Psy.D. programs also incorporate supervised internships to strengthen clinical skills.

Within a Psy.D. program, graduate students focus on specialty areas such as counseling psychology, child psychology , or behavioral psychology. After completing coursework requirements and passing a comprehensive examination, doctoral candidates conduct clinical research in their specialization areas. Degree-seekers analyze clinical problems or examine topics based on original research, then write research-based dissertations.

Earning a Psy.D. typically takes 4-6 years for full-time students. Some programs offer accelerated or part-time enrollment options. Applicant often need a master's in psychology to gain admission to a Psy.D. program.

What's the Difference Between a Psy.D. and a Ph.D. in Psychology?

At the doctoral level, psychology offers Psy.D. and Ph.D. degrees. The two pathways offer different coursework and prepare graduates for different careers.

A Psy.D. emphasizes clinical training for careers in psychology, while a Ph.D. focuses on research and academic training. Licensed psychologists who work directly with patients often hold Psy.D. degrees, while psychology professors typically have Ph.D. degrees. In addition, a Ph.D. typically takes more time than a Psy.D.; while a Psy.D. can take as little as four years, a Ph.D. often requires 5-7 years.

When comparing Ph.D. and Psy.D. programs, prospective psychologists should consider their professional goals. Those seeking research or academic positions may prefer a Ph.D., while those considering careers as licensed psychologists should pursue Psy.D. degrees.

Choosing an Online Doctoral Psychology Program

When choosing a partially online doctoral program, prospective students must weigh several factors. For many, program cost, specialization options, and program length rank among the most important concerns.

Ph.D. and Psy.D. degrees prepare psychologists for different career paths, so applicants should also consider which degree aligns best with their goals. Candidates should also consider enrollment options, course delivery methods, internship options, and tuition discounts when evaluating partially online doctorates in psychology.

By examining these factors, future psychologists can ensure that they find the best fit for their unique needs and career aspirations.

Accreditation for Online Psychology Degree Programs

Prospective applicants should always research program and university accreditation when choosing a partially online doctorate in psychology. Accredited programs follow best practices for educating psychologists, and only graduates of APA-accredited programs qualify for licensure as psychologists. Applicants should also research other state licensure requirements before choosing a program.

What Else Can I Expect From a Doctoral Psychology Program?

Doctoral-level psychology students take courses in areas like counseling psychology, evidence-based practice, human development, and psychopharmacology. These courses build advanced knowledge and skills in psychology. Doctoral students often further specialize their training by choosing concentrations like clinical psych, school psychology, or developmental psychology.

After completing coursework requirements, doctoral candidates must pass examinations and meet any internship requirements. Most programs also require a research-based doctoral dissertation in the candidate's specialization.

Common Courses for an Online Doctorate in Psychology

- Child and Adolescent Therapy: In this class, psychology students strengthen their counseling and treatment skills for children and adolescents. The coursework emphasizes clinical practice and diagnostic approaches for professionals in clinical, child, counseling, and school psychology.

- Clinical Supervision and Consultation: Students practice their supervision skills and learn how to oversee less experienced workers in the field. The course also trains psychology graduates for consultation and mediation roles.

- Community Psychology and Social Justice: The course examines psychology during times of social change. Learners explore social justice in a mental health context and its impact on society more broadly.

- Evidence-Based Practice: Doctoral students examine current research in psychology to identify applications in clinical practice. The course covers topics like evaluating evidence and applying practical research.

- Intellectual and Personality Testing: Psychology students learn to administer and interpret personality assessments. The course covers the theoretical foundations of personality testing and how to perform clinical diagnoses based on those tests.

- Psychopharmacology: In this course, doctoral students learn about the human body and its interactions with drugs. The course emphasizes mental health needs, pharmacological approaches to treating mental health issues, and drug abuse and addiction.

Psychology Specializations

- Collapse All

Clinical Psychology

A clinical psychology specialty emphasizes mental healthcare and research-based practice. Within clinical psychology, doctoral students specialize in demographics, like child psychology and geriatric mental health. The specialty trains learners to apply psychology research in diverse clinical settings.

Developmental Psychology

Developmental psychology examines human growth and development across the lifespan. Doctoral students in this specialty conduct research on childhood development, social and emotional development, and information processing. The specialty prepares graduates for careers in research and academia.

School Psychology

A school psychology specialty emphasizes mental health in young learners. Doctoral students explore learning and behavior, including challenges to academic and social development. These psychologists work with children, families, and schools to help students thrive in education.

Social Psychology

Social psychology examines individual behavior in social settings. This specialty focuses on human interactions and their impact on people's beliefs and feelings. Social psychologists can apply their skills in several settings, including workplaces.

How Long Does It Take to Complete an Online Doctorate in Psychology Program?

No psychology doctorate program is fully online, but earning a partially online doctorate in psychology takes around five years, depending on the program. Many Ph.D. programs require at least five years to complete coursework, research, and a dissertation, and some also require an internship. A Psy.D. program typically takes 4-6 years, including internship requirements.

Some programs offer accelerated or part-time options, which can change degree timelines. Enrollees may also complete coursework faster through a self-paced, asynchronous model, though only online courses are offered asynchronously. Because the length varies, prospective doctoral students should be sure to research prospective programs' requirements and enrollment options before applying.

Psychology Jobs

With a doctorate in psychology, graduates can pursue careers as psychologists and psychology professors. In these career paths, psychologists can conduct research, educate students, and provide clinical services. A psychology doctorate also prepares graduates for supervisory roles, such as healthcare executive.

Other psychology careers include school or educational psychologist, industrial-organizational (I/O) psychologist, and clinical social worker. This section explores common psychology jobs, including the earning potential, licensure requirements, and projected job growth for each career.

Postsecondary Psychology Teachers

Postsecondary psychology teachers, also known as psychology professors, teach at the college level. They educate undergraduate and graduate students on different topics in psychology, including research, behavioral psychology, and human development. In addition to developing syllabi, psychology professors create assignments and exams to assess student learning. These professors also conduct research and publish their work.

A tenure-track psychology professor typically needs a Ph.D., though some colleges hire candidates with Psy.D. degrees to teach clinical psychology or for adjunct positions. Psychology professors may need special licensure, depending on their research and teaching areas.

Median Annual Salary

Projected Growth Rate

Psychologists

Psychologists research behavior and the decision-making process. In specializations like clinical or counseling psychology, they work with individuals and groups managing emotional or behavioral problems. Psychologists also conduct research into human development, identify organizational dynamics, and test neurological responses, often publishing their research.

Most psychologist jobs require a doctorate, though a school psychologist or I/O psychologist may hold only a master's degree. A Psy.D. prepares psychologists for clinical roles and professional licensure. A licensed psychologist typically needs a doctorate, passing scores on a national exam, and supervised professional experience. Psychologists can also pursue specialty certification.

Medical and Health Services Managers

Medical and health services managers, also known as healthcare executives, coordinate services in hospitals, medical practices, and other healthcare organizations. They set policy for their units, analyze data on quality, and implement plans to improve efficiency and effectiveness. Healthcare executives also ensure their organizations follow laws and regulations.

With psychology training, healthcare executives can work for community health and behavioral health facilities, including inpatient treatment centers. They also need administrative training in management and budgeting, and medical and health services managers often hold graduate degrees. The career path does not require a professional license.

Psychology Professional Organizations

Professional organizations help doctoral students expand their professional networks and prepare to transition into clinical practice, research roles, or other psychology careers. These organizations offer career resources, scholarships, and professional development support for doctoral candidates. They may also offer discounted student memberships.

APA represents over 122,000 researchers, clinicians, educators, and students in psychology. The association promotes psychology as a discipline, accredits psychology programs, and offers career resources for students. Members can visit the psychology help center for clinical support or read APA publications to stay current with the field. The association also awards scholarships and fellowships.

Since its founding in 1941, ICP has connected psychologists around the world. Members benefit from annual conferences and newsletters, mentorship opportunities, and professional development resources, such as webinars. This organization also offers travel and recognition awards for members.

AASP dates back to 1985 and represents sports and performance psychology professionals. Members work with athletes, business professionals, and military personnel to improve their physical and mental performance. The association offers professional certifications, hosts an annual conference with networking opportunities, and provides webinars and publications to help practitioners stay current in the field. AASP also offers grants and a student center.

Paying for Your Online Doctorate in Psychology Degree

Doctoral programs typically cost tens of thousands in tuition and fees, even when courses are offered partially online. Fortunately, doctoral students qualify for many forms of financial aid to pay for their degrees.

To start, students should fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), which qualifies filers for federal student loans and work-study programs. In addition to federal loans, students can also use private loans to cover costs. Many states also support degree-seekers with grants or scholarships.

Institutional support helps many graduate students earn psychology degrees. Universities often award fellowships, scholarships, and other forms of financial aid to help recruit and retain students. Some doctoral fellowships include tuition waivers and stipends. To learn about the options at your school, check with the student assistance or finance office.

Finally, psychology degree-seekers qualify for scholarships offered by professional associations, private foundations, and private donors. For example, the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology offers both scholarships and fellowships. The APA also offers scholarships and fellowships for psychology doctoral students.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you become a psychologist with an online degree.

Yes, though there are no accredited psychology doctorates that are available fully online. Instead, programs offer a mix of online and in-person coursework. Psychologists who earn APA-accredited degrees partially online qualify for a professional license in most states. Some career paths, including academia and research, may not require a license.

Are Online Psy.D. Programs APA Accredited?

The APA does not currently accredit any fully online Psy.D. programs. However, the APA does accredit hybrid programs. Always check local state requirements for psychologist licensure before enrolling in a psychology doctoral program to ensure that it meets specifications.

Can You Earn a Doctorate in Psychology Completely Online?

No. As of 2021, the APA — the only agency authorized to accredit psychology doctoral programs — does not accredit any fully online programs.

Learn more, do more.

More topic-relevant resources to expand your knowledge., popular with our students..

Highly informative resources to keep your education journey on track.

Take the next step toward your future with online learning.

Discover schools with the programs and courses you’re interested in, and start learning today.

Clinical Psychology

Mission statement.

Our mission is to advance knowledge that promotes psychological well-being and reduces the burden of mental illness and problems in living and to develop leading clinical scientists whose skills and knowledge will have a substantial impact on the field of psychology and the lives of those in need. Our faculty and graduate students promote critical thinking, innovation, and discovery, and strive to be leaders in their field, engaging in and influencing research, practice, policy, and education. Our pursuit of these goals is guided by the values of collaboration, mutual respect, and fairness, our commitment to diversity, and the highest ethical standards.

Information about the Clinical Psychology Graduate Major

UCLA’s Clinical Psychology program is one of the largest, most selective, and most highly regarded in the country and aims to produce future faculty, researchers, and leaders in clinical science, who influence research, policy development, and practice. Clinical science is a field of psychology that strives to generate and disseminate the best possible knowledge, whether basic or applied, to reduce suffering and to advance public health and wellness. Rather than viewing research and intervention as separable, clinical science construes these activities as part of a single, broad domain of expertise and action. Students in the program are immersed in an empirical, research-based approach to clinical training. This, in turn, informs their research endeavors with a strong understanding of associated psychological phenomena. The UCLA Clinical Science Training Programs employs rigorous methods and theories from multiple perspectives, in the context of human diversity. Our goal is to develop the next generation of clinical scientists who will advance and share knowledge related to the origins, development, assessment, treatment, and prevention of mental health problems.

Admissions decisions are based on applicants’ research interests and experiences, formal coursework in psychology and associated fields, academic performance, letters of recommendation, dedication to and suitability for a career as a clinical scientist, program fit, and contributions to an intellectually rich, diverse class. Once admitted, students engage with faculty in research activities addressing critical issues that impact psychological well-being and the burden of mental illness, using a wide range of approaches and at varying levels of analysis. Their integrated training is facilitated by on-campus resources including the departmental Psychology Clinic, the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, and the David Geffen School of Medicine.

Our program philosophy is embodied in, and our goals are achieved through, a series of training activities that prepare students for increasingly complex, demanding, and independent roles as clinical scientists. These training activities expose students to the reciprocal relationship between scientific research and provision of clinical services, and to various systems and methods of intervention, assessment, and other clinical services with demographically and clinically diverse populations. The curriculum is designed to produce scientifically-minded scholars who are well-trained in research and practice, who use data to develop and refine the knowledge base in their field, and who bring a reasoned empirical perspective to positions of leadership in research and service delivery.

The program’s individualized supervision of each student in integrated research and practice roles provides considerable flexibility. Within the parameters set by faculty interests and practicum resources, there are specializations in child psychopathology and treatment, cognitive-behavior therapy, clinical assessment, adult psychopathology and treatment, family processes, assessment and intervention with distressed couples, community psychology, stress and coping, cognitive and affective neuroscience, minority mental health, and health psychology and behavioral medicine. The faculty and other research resources of the Department make possible an intensive concentration in particular areas of clinical psychology, while at the same time ensuring breadth of training.

Clinical psychology at UCLA is a six-year program including a full-time one-year internship, at least four years of which must be completed in residence at UCLA. The curriculum in clinical psychology is based on a twelve-month academic year. The program includes a mixture of coursework, clinical practicum training, teaching, and continuous involvement in research. Many of the twenty clinical area faculty, along with numerous clinical psychologists from other campus departments, community clinics, and hospitals settings, contribute to clinical supervision. Clinical training experiences typically include four and a half years of part-time practicum placements in the Psychology Clinic and local agencies. The required one-year full-time internship is undertaken after the student has passed the clinical qualifying examinations and the dissertation preliminary orals. The student receives the Ph.D. degree when both the dissertation and an approved internship are completed.

Accreditation

PCSAS – Psychological Clinical Science Accreditation System

The Graduate Program in Clinical Psychology at UCLA was accredited in 2012 by the Psychological Clinical Science Accreditation System (PCSAS). PCSAS was created to promote science-centered education and training in clinical psychology, to increase the quality and quantity of clinical scientists contributing to the advancement of public health, and to enhance the scientific knowledge base for mental and behavioral health care. The UCLA program is deeply committed to these goals and proud to be a member of the PCSAS Founder’s Circle and one of the group of programs accredited by PCSAS. (Psychological Clinical Science Accreditation System, 1800 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Suite 402, Washington, DC 20036-1218. Telephone: 301-455-8046). Website: https://www.pcsas.org

APA CoA – American Psychological Association Commission on Accreditation

The Graduate Program in Clinical Psychology at UCLA has been accredited by the American Psychological Association Commission on Accreditation since 1949. (Office of Program Consultation and Accreditation, American Psychological Association, 750 First Street NE. Washington, DC 20002-4242. Telephone: 202-336-5979 .) Website: http://www.apa.org/ed/accreditation/

Future Accreditation Plans:

Against the backdrop of distressing evidence that mental health problems are increasingly prevalent and burdensome, the field of psychological clinical science must think innovatively to address the unmet mental health needs of vulnerable populations. UCLA’s clinical psychology program remains committed to training clinical psychological scientists who will become leaders in research, dissemination, and implementation of knowledge, policy development, and evidence-based clinical practice. This commitment is firmly rooted in our overall mission of promoting equity and inclusion, adhering to ethical standards, and developing collaborations in all aspects of clinical psychology.

Increasingly, we believe that significant aspects of the academic and clinical-service requirements of accreditation by the American Psychological Association (APA) obstruct our training mission. Too often, APA requirements limit our ability to flexibly adapt our program to evolving scientific evidence, student needs, and global trends in mental health. Like many other top clinical science doctoral programs, we see our longstanding accreditation by the Psychological Clinical Science Accreditation System (PCSAS) as better aligned with our core values, including advancement of scientifically-based training.

Accordingly, we are unlikely to seek renewal of our program’s accreditation by APA, which is set to expire in 2028. The ultimate decision about re-accreditation will be made with the best interests and well-being of current and future students in our program in mind. To that end, we will continue to monitor important criteria that will determine the career prospects of students completing a doctoral degree in clinical psychology from programs accredited only by PCSAS. For example, we are working to understand the potential implications for securing excellent predoctoral internships and eligibility for professional licensure across jurisdictions in North America. Although the UCLA clinical psychology program has no direct influence over these external organizations, we are excited to continue to work to shape this evolving training landscape with the Academy of Psychological Clinical Science (APCS) and leaders from other clinical science programs.

Our ongoing monitoring of trends in clinical psychology training is encouraging for PCSAS-accredited programs. However, evolving circumstances could result in our program changing its opinion with respect to seeking APA re-accreditation in the future. In the spirit of transparency and empowering potential applicants to make informed choices for their own professional development, we are pleased to share our thinking on these important issues.

Notice to Students re: Professional Licensure and Certification

University of California programs for professions that require licensure or certification are intended to prepare the student for California licensure and certification requirements. Admission into programs for professions that require licensure and certification does not guarantee that students will obtain a license or certificate. Licensure and certification requirements are set by agencies that are not controlled by or affiliated with the University of California and licensure and certification requirements can change at any time.

The University of California has not determined whether its programs meet other states’ educational or professional requirements for licensure and certification. Students planning to pursue licensure or certification in other states are responsible for determining whether, if they complete a University of California program, they will meet their state’s requirements for licensure or certification. This disclosure is made pursuant to 34 CFR §668.43(a)(5)(v)(C).

NOTE: Although the UCLA Clinical Psychology Program is not designed to ensure license eligibility, the majority of our graduates do go on to become professionally licensed. For more information, please see https://www.ucop.edu/institutional-research-academic-planning/content-analysis/academic-planning/licensure-and-certification-disclosures.html .

Clinical Program Policy on Diversity-Related Training

In light of our guiding values of collaboration, respect, and fairness, this statement is to inform prospective and current trainees, faculty, and supervisors, as well as the public, that our trainees are required to (a) attain an understanding of cultural and individual diversity as related to both the science and practice of psychology and (b) provide competent and ethical services to diverse individuals. Our primary consideration is always the welfare of the client. Should such a conflict arise in which the trainee’s beliefs, values, worldview, or culture limits their ability to meet this requirement, as determined by either the student or the supervisor, it should be reported to the Clinic and Placements Committee, either directly or through a supervisor or clinical area faculty member. The Committee will take a developmental view, such that if the competency to deliver services cannot be sufficiently developed in time to protect and serve a potentially impacted client, the committee will (a) consider a reassignment of the client so as to protect the client’s immediate interests, and (b) request from the student a plan to reach the above-stated competencies, to be developed and implemented in consultation with both the trainee’s supervisor and the Clinic Director. There should be no reasonable expectation of a trainee being exempted from having clients with any particular background or characteristics assigned to them for the duration of their training.

Clinical Program Grievance Policies & Procedures

Unfortunately, conflicts between students and faculty or with other students will occur, and the following policies and procedures are provided in an effort to achieve the best solution. The first step in addressing these conflicts is for the student to consult with their academic advisor. If this option is not feasible (e.g. the conflict is with the advisor) or the conflict is not resolved to their satisfaction, then the issue should be brought to the attention of the Director of Clinical Training. If in the unlikely event that an effective solution is not achieved at this level, then the student has the option of consulting with the Department’s Vice Chair for Graduate Studies. Students also have the option of seeking assistance from the campus Office of Ombuds Services and the Office of the Dean of Students. It is expected that all such conflicts are to be addressed first within the program, then within the Department, before seeking a resolution outside of the department.

More Clinical Psychology Information

- For a list of Required Courses please see the Psychology Handbook

- Psychology Clinic

- Student Admissions Outcomes and Other Data

- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

Graduate Program

History and overview of the program.

The San Diego campus of the University of California was formally established in 1958 around the nucleus of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. It has since become one of the most renowned research universities in the United States. The Department of Psychology was formed in 1965 and first admitted graduate students in 1966. For the 2021/2022 academic year, there are 79 graduate students in the Department's doctoral program. As of June 30, 2021, 426 doctoral degrees have been awarded.

The Department remains committed to the belief that the best training for a career in psychology, even one in clinical psychology, is a strong background in Experimental Psychology . As such, conducting experimental research is the primary activity of graduate students in our program.

Each graduate student in our Department works closely with one or more faculty advisor(s) throughout their graduate career, in an apprenticeship system that distinguishes our Department from others. Our graduate students are actively involved in research design, implementation, analysis, and publication processes, and they are treated more like colleagues than students.

Graduate students in our program start off by conducting a year-long independent research project, which serves as a major criterion in the evaluation of our first year students. In addition to conducting well-supervised, original research in their respective labs, our students take classes (seminars and proseminars), teach and mentor undergraduate students, participate in lab meetings and journal clubs, and attend Department-sponsored events, such as Brown Bag meetings and our Colloquium Speaker Series .

Our Department and the greater University are committed to providing a safe and supportive environment for all our members. Click on the following links to read our Department Climate Statement , and the UC San Diego Principles of Community .

- Research Areas

- Undergraduate Program

- Top 10 Online Marriage and Family Counseling Degree Programs

- 20 Best Online Master’s in Pastoral Counseling Degree Programs 2018

- Top 30 Master’s in Marriage and Family Counseling Online Degree Programs

- Genetic Counseling

- Career Counseling

- Addiction Counseling

- Marriage Counseling

- Christian Counseling

- Mental Health Counseling

- Privacy Policy

25 Most Affordable Online Doctoral Programs in Psychology for 2021

Are you passionate about the field of psychology and looking to earn an advanced degree? If you have a master’s degree in psychology, it’s time to pursue a doctoral degree and grow as a clinical, counseling, or research psychologist. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, psychologists’ jobs will increase by 14 percent through 2026, faster than other professions. To stay ahead of this demand, opting for a doctoral program now is the right career choice.

How can an online doctorate in psychology help?

An online doctorate in psychology equips students with the knowledge and skills to qualify for a range of professional opportunities. They are prepared to practice in different branches of psychology based on their specialization. It also prepares students for state licensures. Doctorate graduates work in various settings, including Mental health centers, Government agencies, Social service agencies, and Healthcare organizations. What does the online doctorate in psychology curricula entail? Online psychology Ph.D. classes vary by school. The curricula are a mix of core course requirements, electives, specializations, a clinical internship, or supervised practicum. The blend of these formats teaches students to apply the scientific method towards research and daily work. They learn to investigate the elements behind mental illness and treatment. Students gain an understanding of the research ethics and the American Psychological Association (APA) citation.

What can you do with an online doctorate in psychology?

- Clinical psychologist

- Forensic psychologist

- Research psychologist

- Political strategist

- Educational consultant

- Academician/Professor

- Private practice psychologist

Here we have shortlisted the top 25 schools that offer affordable online doctoral programs in Psychology. These programs are designed for working professionals who are looking to gain penultimate degrees in their field. They offer flexibility and self-paced formats to allow students to balance their work-life commitments as they study. They follow the same rigorous curricula as the traditional campus programs. We have considered the schools’ accreditation, rankings, faculty, tuition, student support systems, and curricula. Schools have been ranked based on the affordability of their programs.

Rating and Ranking Methodology

Tuition

- Net Price Below $10,000: 4 points

- Net Price Below $15,000: 3 points

- Net Price Below $18,000: 2 points

- Net Price Below $20,000: 1 point

Program Flexibility (asynchronous course delivery, hybrid options, part-time/full-time schedule, etc. ) – 1 point per item Online Student Support Network (faculty mentors/advisors, etc.)— 1 point per item Accreditation (School-Wide and Program-Specific) – 1 point per item “Wow” Factor – 1 point.

#25 New York University Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development

New york, ny.

Doctor of Occupational Therapy Online

Visit Website Points: 5

NYU Steinhardt offers an online The Online Doctor of Occupational Therapy program. Students can customize their degree through an individualized curriculum and a wide variety of elective and clinical specialization courses. It helps them become well-rounded clinicians and grow as a leader in the field. Elective courses include:

- Leadership in Occupational Therapy

- Promoting Family Resilience and Family-Centered Services

- Disability in a Global Context