- Criminal Law Assignment Help

- Taxation Law Assignment Help

- Business Law Assignment Help

- Contract Law Assignment Help

- Civil Law Assignment Help

- Land Law Assignment Help

- Tort Law Assignment Help

- Company Law Assignment Help

- Employment Law Assignment Help

- Environmental Law Assignment Help

- Commercial Law Assignment Help

- Criminology Assignment Help

- Corporate Governance Law Assignment Help

- Constitutional Law Assignment Help

- Operations Assignment Help

- HRM Assignment Help

- Marketing Management Assignment Help

- 4 Ps Of Marketing Assignment Help

- Strategic Marketing Assignment Help

- Project Management Assignment Help

- Strategic Management Assignment Help

- Risk Management Assignment Help

- Organisational Behaviour Assignment Help

- Business Development Assignment Help

- Change Management Assignment Help

- Consumer Behavior Assignment Help

- Operations Management Assignment Help

- Public Relations Assignment Help

- Supply Chain Management Assignment Help

- Conflict Management Assignment Help

- Environmental Assignment Help

- Public Policy Assignment Help

- Childcare Assignment Help

- Business Report Writing Help

- Pricing Strategy Assignment Help

- Corporate Strategy Assignment Help

- Managerial Accounting Assignment Help

- Capital Budgeting Assignment Help

- Accounting Assignment Help

- Cost Accounting Assignment Help

- Financial Accounting Assignment Help

- Corporate Finance Assignment Help

- Behavioural Finance Assignment Help

- Financial Ethics Assignment Help

- Financial Management Assignment Help

- Financial Reporting Assignment Help

- Forensic Accounting Assignment Help

- International Finance Assignment Help

- Cost-Benefit Analysis Assignment Help

- Financial Engineering Assignment Help

- Financial Markets Assignment Help

- Private Equity and Venture Capital Assignment Help

- Psychology Assignment Help

- Sociology Assignment Help

- English Assignment Help

- Political Science Assignment Help

- Arts Assignment Help

- Civil Engineering Assignment Help

- Computer Science And Engineering Assignment Help

- Economics Assignment Help

- Climate Change Economics Assignment Help

- Java Assignment Help

- MATLAB Assignment Help

- Database Assignment Help

- PHP Assignment Help

- UML Diagram Assignment Help

- Web Designing Assignment Help

- Networking Assignment Help

- Chemistry Assignment Help

- Biology Assignment Help

- Nursing Assignment Help

- Biotechnology Assignment Help

- Mathematics Assignment Help

- Assignment Assistance

- Assignment Help Online

- Cheap Assignment Help

- Assignment Paper Help

- Solve My Assignment

- Do My Assignment

- Get Assignment Help

- Urgent Assignment Help

- Write My Assignment

- Assignment Provider

- Quality Assignment Help

- Make My Assignment

- Online Assignment Writers

- Paid Assignment Help

- Top Assignment Help

- Writing Assignment For University

- Buy Assignment Online

- All Assignment Help

- Academic Assignment Help

- Assignment Help Tutors

- Student Assignment Help

- Custom Assignment Writing Service

- English Essay Help

- Law Essay Help

- Management Essay Help

- MBA Essay Help

- History Essay Help

- Literature Essay Help

- Online Essay Help

- Plagiarism Free Essay

- Write My Essay

- Admission Essay Help

- TOK Essay Help

- Best Essay Writing Service

- Essay Assignment Help

- Essay Writers Online

- Professional Essay Writers

- Academic Writing

- Homework Help

- Dissertation Help

- University Assignment Help

- College Assignment Help

- Research Paper Writing Help

- Case Study Help

- Coursework Help

- Thesis Help

- PowerPoint Presentation Service

- Job Openings

Top 50 Organizational Behaviour Dissertation Topics Trending in 2021

- July 7, 2021 July 15, 2021

The behaviour of the workforce is directly proportional to the efficiency output in a production cycle. It is the motivation, activities promoting teamwork and on-time grievance redressal that help the worker to nurture his or her skills. Besides, it dynamically contributes to the exponential growth of the organization. The study of organizational behaviour is regarded as an integral part of any management course. It helps a management aspirant to delve into an in-depth study of the human psychology and behaviour in the given organizational settings. It is primarily the study and analysis of the interface between the human behaviour and the organization, as well as the organization itself.

GET HELP INSTANTLY Place your order to get best assignment help

(since 2006)

Introduction

The study of organisational behaviour standardly comprises of many dissertations, case studies, essays, and thesis papers to reflect the conceptual clarity of the student. To successfully clear this management subject with the desired grades, the students are required to attend all the given assignment homework on time. All these submissions are required to be made with an unmatched quality of eloquent writing prowess. The management students who prefer to attend their organisational behaviour homework themselves without professional assignment help , always counter numerous hurdles to begin with.

The selection of the right organisational behaviour assignment topic is one of the quibbling bulwarks that can curtail the pace of swift assignment submission. Here, our prima-facie motto is to help our students irrespective of the fact whether they are hiring our assignment writing services or not. We have created the list of the top organisational behaviour dissertation topics after conducting an intense number of research and brainstorming sessions. While creating the list, we have made sure that the students from all kinds of management backgrounds, course curriculums, and diversified nations could reap benefits out of the give piece of information.

The Principle Elements of an Organisational Behaviour Study

There are in total four main elements of a successful organisational behaviour (OB) study –

- People: The people to people contact is somehow extremely crucial to induce the cohesiveness between the team members to improve the overall productivity. The groups of people within the organization may change, form or dissolve. Time to time team-building activities and effectual grievance redressal mechanism could boost a sense of belongingness between the organisation and its manpower.

- Structure: The structural layout of the organisation and the delegation of authority somehow segregate the rights, duties, functions, and responsibilities of all the members of the organisation in a crystal-clear sense. The behavioural approach and the outlook of the members of the organization is decided on the grounds of the designation and the level in the hierarchy that they are occupying. Yet, right from the designation of the CEO to the executives and supervisors operating at the lower level, certain structural traits like communication, mutual understanding and respect would always remain common at all levels.

- Technology: If we speak in terms of the contemporary scenario of the organisational work culture, then the absence of technology could either make the functioning difficult or impossible. It is primarily because of the intervention of the technology, that we could access physical and economic resources to make the jobs of the people easy. The assistance could be procured through machines, methods, and tools. The technology could enforce restrictions on the freedom of the people but deliver efficiency in terms of the contingent nature of tasks at diverse scale of operations.

- External Environment: The organisational behaviour not only get influenced by the internal environment but the external one as well. The functions of an organization exist in a larger social system and external environmental forces like socio-cultural, political, economic, technological, legal, and geographical forces. These are some of the typical external environmental forces that impact the attitudes, working conditions and motives of the people. In a similar sense, there are circumstances, where the organisations could also have an impact over the environment, but its degree would certainly be less than the vice-versa.

When students seek dissertation help related to different OB topics, these are some of the principle elements that frequently occur in the homework assigned at different stages of the course curriculum.

Read our sample page of a management topic by going through the below link to behold how eloquently our writers could blend diverse topics like management and healthcare in single assignment order.

Must read: change management in the healthcare facility – sample, the organizational behaviour models that are critical for management students to understand.

The online assignment help rendered by the professionals are primarily based upon the time-tested models of organisational behaviour. Let us briefly throw some light over them one after the other –

- Autocratic Model: This OB model emphasises on the rule that the employees are required to be instructed in detail and constantly motivated to perform in their job. Here, it is the job of the manager to conduct all the thinking part. The formalization of the entire process is done by the managers, and they wield the authority to give command to the entire workforce.

- Custodial Model: The model is more revolving around the economic and social security of the employee. Here, the companies do offer high scale pay, financial packaging, health benefits, corporate cars, and other forms of incentives. The model is induced to make sure that the employee shall remain loyal and dependent on the company, rather than the supervisor, manager, or the boss.

- Supportive Model: The model sustains around the motivation and value given to the employee, instead of money and command being the driving factor. The relationship between the manager and the employee goes beyond the day-to-day activity and role. The model is more effective in developed nations, in comparison of developing nations, where monetary gains and delegation of authority play a very pivotal role.

- Collegian Model: How good it would be a model with no worry about the job status or title? How good it would be if our manager would act as a supportive coach, instead of being bossy? Well, this model functions in an organizational structure where all the colleagues work as a team. There is no boss or subordinates and participates coordinate better to achieve the assigned target rate.

- System Model: One of the most popular and emerging OB models in the contemporary corporate arena. Here, the managers try to nurture a culture sharing authenticity, transparency, and social intelligence. The motto is to link the employees emotionally and psychologically with the interests of the organization and make them more accountable for their actions.

The questions that frequently appear in OB dissertation assignments tend to revolve around the models that we discussed above. Some of the models are comparatively more preferred and practiced than the rest.

What are We Intended to Gain by Sharing a Well-Researched List of 50 Topics?

Well, our motto is to help the students save their time, energy, and resources to focus solely on the content. We have seen a plethora of students spending ridiculous amounts of time just on topic selection. What is essential for the students to understand here is that the selection of the right topic is not going to earn them the premium grades. It is the presentation of the right topic in the right content and format that become game-changer for them. The number of OB topics listed below are the ones that do matter in the prevalent managerial culture and that can help score some brownie points in the eyes of the evaluator.

Explore our business analytics sample at the below link to witness our optimum standards of assignment writing dedicated to quality-oriented students.

Must read: business analytics – demand forecasting – sample, top 50 organizational behaviour dissertation topics for the year 2021.

The following is the list of OB dissertation topics that can turn out to be a prudent choice for the number of assignment submissions that you make in future –

- The resistance of the employees towards organisational change and the right measures to curb the same

- The work environment stressors: The link between the job performance and the well-being of the employees

- Conflict management in the cross-functional project teams in a Singaporean corporate culture

- The role of social networks in the field of global talent management

- Apply the ‘Theory of Planned Behaviour’ in the assessment of the attitude of students towards self-employment

- Measuring the collective mindfulness as well as navigating its nomological network

- Recognizing and rewarding the employees: How the IT professionals in Germany and in France are motivated and rewarded?

- The incorporation of organisational identity in the turnaround research: A case study

- The top 10 findings on the resilience and the engagement of the employee

- The competition straight from the inside out

- How to overcome the virtual meeting fatigue during the pandemic crisis?

- Why good leaders fail?

- Building up better work models to effectively function in the next normal

- Promoting employee wellness within an organization, now and post the Chinese Covid-19 pandemic

- Turbulent times anticipate dynamic rules: Discuss

- The courage to be candid: The merits and demerits in an organisational setup

- The personal network utility to nurture an inclusive culture

- Putting up blinders can actually help us see more clearly: Discuss

- Redesigning the workspace to propel social interaction

- How to set customer satisfaction as one of the key yardsticks for healthy organisational behaviour?

- Counterproductive behaviour at work: The adversities and remedies

- How creative at the workplace could bring in more job satisfaction?

- Cyberloafing at the work: How it is a matter of grave concern than we actually imagine?

- Employee theft: The right measures for the culture of integrity and work ethics

- How technological innovation could enhance the job performance at the workplace?

- Organisational retaliatory behaviour: The causes and the measures to ensure minimal impact

- Whistle-blowing culture and how it changed the American work culture forever?

- Withdrawal Behaviour: Absenteeism and lateness and the countermeasures to prevent the same

- Conflicting value systems and their impact on complex work culture

- Managerial research and pursuit of opportunity: Elaborate

- How TMT diversity and CEO values jointly influence the culture of a corporate world?

- The emerging role of the team-players in a multicultural organisation setup

- How the external factors could actually impact the motivation of an employee, and eventually his or her behaviour?

- The situations of interpersonal conflict and how it can change the overall scheme of things in an organisational setup?

- Emotional responses of entrepreneurs to a situation of bankruptcy

- How the study of correct organizational behaviour could actually increase the chances of survival within an organisation?

- How promoting cultural connections in MNCs can actually promote the organisational culture?

- Need Theory Perspective: Motivational preferences of the workforce

- Investigation and assessment of the motivational factors at work

- A rationalised utility of the link between the social capital and the organisational learning

- Bullying before the occurrences of sexual harassment: Preventing the inevitable

- Conspiracies at the workplace: Recognizing and neutralising the root cause

- Effective strategies for the management at the age of boycotts

- Creation of an OB mentoring program that works at all levels

- The repercussions of bad management on employee behaviour and what are the possible remedies?

- Leveraging the organisational identity to gain a competitive edge

- Spiritual leadership and its impact on the outlook of the organisational workforce

- The role of positive organisational communities pre-and-post organisational goals

- The organisational behaviour for specially-abled workers to make their role more constructive to the organisational settings

- Managing successfully the dark side of the competitive rivalry before it affects the interpersonal relations within an organisational setting

And with that, we come to the end of the top 50 OB assignment topics that can not only fulfil our dissertation topic requirements, but also the assignment writing requirements of various other formats. The requirements related to topic selection for case study help , essay help , research paper writing help , or thesis help can also be referred and met with the given list of topics.

Care to master finest dissertation writing skills in just two weeks? Well, we are more than glad to help! Read the below article to let the experts hone your skills right away!!

Must read: wish to master dissertation skills in 2 weeks learn from the experts here.

The organisational behaviour dissertation topics enlisted above would cover various dynamic aspects of corporate culture revolving around the human behaviour. The topic list would not only help you cover the assignment topic demand for all the upcoming semesters, but also impressing your colleagues with topic suggestion prowess. It makes the efforts of assignment writing more seamless as the student could customise his or her writing as per the liking or aptitude of a specific type of OB topic.

Nevertheless, the requirements of the students are not merely confined to OB dissertation topic recommendation only. There are situations where management students prefer to hire paid assignment help to get their regular assignments done with perfection. The reasons can be associated with the lack of subject clarity, lack of time and resources or commitment to other critical events like exams or co-curricular activities. You can visit organisational behaviour assignment help at Thoughtful Minds to order online homework help related to all OB topics at the most competitive rates from the industry professionals of more than 15 years of experience.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

4 Organizational Behavior’s Contributions to Evidence-Based Management

Denise M. Rousseau is H. J. Heinz II Professor of Organizational Behavior and Public Policy at the Heinz School of Public Policy and Management at Carnegie Mellon University.

- Published: 18 September 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Organizational Behavior (OB) is a social science that has discovered general principles regarding the organization and management of work. One of management research’s more mature fields, OB’s contribution to evidence-based Management (EBMgt) stems from its large body of programmatic, cumulative research. This chapter provides an overview of OB research, including its history, standards for evidence, and domains of study. It distinguishes between science- and practice-oriented OB research and their respective evidence criteria to better show different ways OB research can inform EBMgt. OB research has identified several hundred evidence-based principles to inform practice, and this chapter provides examples. The chapter concludes by discussing how OB scholars, educators, and practitioners can further EBMgt practice.

Organizational Behavior’s Contribution to Evidence-Based Management

This chapter provides an overview of the background and focus of the OB field and its findings. It uses examples of well-established findings to demonstrate the sort of actionable principles OB contributes to guide evidence-informed practice. It then assesses the state of OB practice and education. The chapter concludes with implications for how practitioners, educators, and researchers can further the development and use of OB knowledge in evidence-based management (EBMgt).

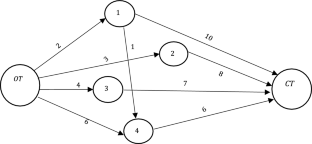

Organizational behavior has been a mainstay in professional management education for decades. The field’s goals are to understand human behavior in organizations and provide knowledge useful to practitioners. These two goals often coincide. Here’s an example from one manager’s experience: Jim Fuchs, a midlevel manager in an American firm, came up to me after a session on change management in my business school’s executive program. “Let me show you what I do when I see a need to convince the supervisors reporting to me that we need to change something about how we manage our people,” he said, going over to one of the classroom’s flip charts. “I learned Porter and Lawler’s model of motivation back while I was an undergraduate [business major],” he said, as he sketched out a diagram (Figure 4.1 ). “First, to get people to put out effort in new ways, they have to see that a certain kind of new behavior is more likely to bring them rewards [effort-reward probability] they care about [value of reward]. Then, they need to put out the right kind of effort to produce the performance we need [effort→performance accomplishment], which means they need to know what new thing they’re supposed to be doing [role perceptions] and have the ability to do it [abilities and traits]. If you put the right rewards, skills, and expectations in place, you get the right results and your employees stay motivated.” I commented that this might be one of the best examples of how an undergraduate OB course can be useful. Jim laughed and said, “At this point, my supervisors know this model by heart.”

Jim Fuch’s diagram for discussing design and change adapted from Porter and Lawler.

This classic evidence-based motivation model, as Lyman Porter and Edward Lawler ( 1968 ) formally presented it, is a bit more detailed (Figure 4.2 ) than Jim’s diagram—consistent with the large and diverse body of evidence on which it is based. Yet Jim’s adaptation of it has the essentials. Importantly, Jim drew upon this scientifically developed framework in his day-to-day management practice, applying it wherever he judged it to be useful. By using this model regularly, his staff learned how to think more systematically about why employees do what they do on the job and how to motivate them to do more and do better. Jim Fuchs’s approach fulfills an important objective of science: to think clearly about the social and physical world and make informed interventions in it. It also exemplifies a simple but adaptable way in which OB research (and well-supported theory) can contribute to EBMgt.

Porter and Lawler’s motivational model.

At this writing, OB is arguably one of the more developed bodies of scientific knowledge relevant to management practice. Like the broader field of managerial and organizational research of which it is a part, OB is a social science. MBA and undergraduate business programs incorporate a good deal of the field’s evidence into courses on decision making, leadership, and teams (Chartiers, Brown & Rynes, 2011 ). Along with other research-oriented fields such as marketing and advertising (Armstrong, 2011 ), OB offers a substantial research base to inform management education and practice. Some OB findings are already distilled into useable form (e.g., Locke, 2009 ) for management education, professional and personal development, and problem solving. At the same time, making it easier for practitioners to know about and use the OB evidence base continues to be a work in progress.

A Century of Research

Research on fundamental processes in organizing and managing work began with the activities of OB’s parent disciplines, industrial-organizational psychology (known as work and organization psychology in Europe; Munsterberg, 1913 ), industrial sociology (Miller & Form, 1951 ), public administration (Follett, 1918 ; Gulick, & Urwick, 1937 ; Simon, 1997 ) and general management (Drucker, 1974 ; McGregor, 1960 ). Early empirical work focused on employee selection, testing, vocational choice, and performance (Munsterberg, 1913 ); group dynamics, supervisory relations and incentives (e.g., Hawthorne studies, Roethlisberger & Dickson, 1939 ); worker attitudes (Likert, 1932 ; Kornhauser, 1922 ); and leadership, authority, and control (Selznick, 1945; Braverman, 1974 ).

The formal label “organizational behavior” emerged in the 1960s and 1970s, as business schools responded to criticism that what they were teaching was more opinion and armchair theorizing than validated knowledge (Gordon & Howell, 1959 ). Schools began hiring social scientists to promote the use of research to understand and solve organizational problems and provide more science-based business education (Porter & McKibbin, 1988 ). OB departments sprang up where once stood more eclectic “management” or “personnel” units.

Today’s OB researchers come from many fields. Some identify OB as their home discipline, typically completing doctorates in business schools. Others originate in and often continue to identify with psychology, sociology, human development, or economics. All these researchers share an interest in how humans behave in organizations. As just one example of the cross-pollination between behavioral science and business disciplines prevalent in OB, the author of this chapter is an OB professor with a doctorate in industrial-organizational (I-O) psychology who has taught in both psychology departments and schools of business and public-sector management.

Today, OB research is prevalent worldwide, with thousands of researchers currently at work expanding the OB knowledge base. The largest professional association focused management research is the Academy of Management. In 2011, the Academy had over 19,000 members. Its OB division had nearly 4,000 active academic members and more than 400 executive/practitioner members, and the human-resources division, whose research (and some of its members) overlap OB, had almost 2,500 academic members and 300 executive/practitioner members. Other professional associations outside the United States also have members who are actively adding to the OB knowledge base.

Forces at multiple levels drive how humans behave in organizations. OB research investigates individual and group behavior along with formal and informal organization-wide dynamics. The types of phenomena that intersect the OB field range from the oil-rig worker trying to decide whether to report hazardous job conditions to the conflict-ridden top- management team whose infighting undermines how the company’s frontline managers perform. As a multilevel field, OB scholarship rides the organizational elevator from individual personality, beliefs, and behavior to group dynamics to organizational- and industry-level practices that affect how people act and respond in organizations.

The largest body of OB research addresses individual and group behaviors and their ultimate causal connections with organizational performance and member well-being. This wide array of studies on individuals and groups is the reason academics sometimes refer to OB scholars and their research as “micro” (as opposed to more “macro” areas of organizational theory or strategic management, see Madhavan & Mahoney, chapter 5 of this volume), as in “she’s a micro person.” However, the term micro is not a particularly accurate description for the OB field (Rousseau, 2011 ). A good deal of OB research examines such organization-level phenomena as culture or change implementation (e.g., Schein, 2010 ), but the micro/macro distinction remains common in academic OB-speak.

OB Research Philosophy and Objectives

The research philosophy underlying OB is largely in-line with evidence-based management (Briner, Denyer & Rousseau, 2009 ; Rousseau, chapter 1 of this volume), with its aspiration to improve organization-based decision making and to tackle applied problems in ways that balance economic interests with the well-being of workers (Argyris, 1960 ; Katz & Kahn, 1966 ; Munsterberg, 1913 ; Viteles, 1932 ).

Historically, OB research has been responsive to business trends and practice concerns. Over time, its emphasis has shifted—from productivity to global competitiveness and quality; from employee security to employability (see Rousseau, 1997 , for an assessment of trends from 1970s to 1990s). Indeed, critics inside and outside the field have long argued that it tends to emphasize managerial and performance-related concerns over the concerns of workers and other stakeholders (Baratz, 1965 ; Ghoshal, 2005 )—an appraisal echoed by Hornung (chapter 22 of this volume) and other critical theorists.

On the other hand, OB research addressed the worker experience on the job even prior to the famous Hawthorne studies at Western Electric (Roethlisberger & Dickson, 1939 ) or the popularity of work-satisfaction questionnaires (originally developed for Kimberly Clark by Kornhauser and Sharp ( 1932 ; Zickar, 2003 ). Since then, a good deal of research concentrates on the effects of work and organizations on the well-being of workers, families, clients, and the general public (e.g., Gardell, 1977 ; Karasek, 2004 , Kossek & Lambert, 2005 ). More recently, the “Positive Organizational Behavior” movement has expanded both the goals of organizational research and the outcomes it studies to include how workers can thrive in organizational settings (Dutton & Ragins, 2006 ). The large and growing body of OB research is wide-ranging in its economic and social implications.

Focus on Cumulative Findings

My sense is that supporting EBMgt comes relatively naturally to many OB scholars and educators. As Chartier and colleagues ( 2011 ) report, OB educators typically rely on evidence more than do faculty in the fields they surveyed, such as international business or strategy. Part of this reliance is attributable to the cumulative findings in certain core OB research areas. The field’s history and tendency toward sustained interest in particular topics makes possible the cumulative research that is generally valued in the evidence-based practice movement (Barends, ten Have, & Huisman, chapter 2 of this volume). OB’s accumulated findings contrast with newer management-research fields, such as strategy and organizational theory (Madhavan & Mahoney, chapter 5 of this volume) where less attention has yet been paid to creating integrative knowledge (cf. Whitley, 1984 ; 2000 ). As such, OB scholars have, over time, pulled together and built on the available evidence on an array of management issues. The result provides evidence-informed practitioners and educators with numerous well-supported principles of human behavior, organizing, and managing, with considerable practical value (e.g., Locke, 2009 ). I present examples of these principles later, after discussing a key reason that cumulative findings in OB research can produce these principles, that is, the largely agreed-on norms for what constitutes evidence in the OB field.

Criteria for Evidence

Generally speaking, the OB field has certain widely held norms about what constitutes sufficient evidence to make claims regarding the truth of a research finding. Norms are particularly well articulated for what I refer to here as OB’s “science-oriented evidence.” These norms, exemplified by the seminal work of Cook and Campbell ( 1979 ), emphasize the value of (1) controlled observations to rule out bias and (2) consistency with the real world to promote the generalizability of findings. Classic academic or scholarly research is motivated to understand the world (i.e., to develop and test theory). Less widely discussed or, perhaps, agreed upon, are the norms or standards for OB’s “practice-oriented evidence.” Practice-oriented research investigates what practitioners actually do in organizations. In particular, a practice orientation demonstrates what happens when scientific evidence is acted upon in real-world settings. The goals of science- and practice-oriented research differ. Thus, each necessarily emphasizes somewhat different indicators of evidence quality.

Note that the same study can have both science and practice goals. For example, employee participation systems have been investigated to test scientific theories of voice and motivation as well as such systems’ practical impacts on productivity and their sustainability over time (e.g., the Rushton project, Goodman, 1979 ). Equitable pay practices have been examined to evaluate equity and justice theories and impact on employee theft (Greenberg, 1990 ). Job enrichment interventions have tested both theory regarding optimal levels of job autonomy and impact on the quality of wastewater treatment (Cordery, Morrison, Wright, & Wall, 2010 ). Such studies are proof that science and practice goals can go hand-in-hand.

Criteria for Science-Oriented OB Evidence

The general goal of science-oriented research is to interpret and understand. OB research pursues this goal by relying largely on a body of studies , rather than on the results of any single study, in evaluating a particular finding’s validity. Because all studies are limited in some fashion, no single study is sufficient to establish a scientific fact. Good evidence constitutes a “study of studies,” where individual or primary studies are considered together in order to allow the credibility of their overall findings to be assessed (Briner & Denyer, chapter 7 of this volume; Rousseau, Manning, & Denyer, 2008 . Systematically interpreting all relevant studies is the general standard for determining the merit of any claims regarding evidence (Hunter & Schmidt, 1990 ). (N.B.: Practitioners are more likely to use rapid reviews, that is, quick searches through a few studies to see if agreed-upon findings exist, and other expedient assessments of published evidence when no systematic review is available.) The most common form of systematic review in OB is the meta-analysis , a quantitative analysis of multiple studies to determine the overall strength or consistency of an observed effect (e.g., job satisfaction’s effect on performance). It is not unusual for OB meta-analyses to review hundreds of studies, combining results for 30,000+ individuals—as in the case of the impact of general mental ability on occupational attainment and job performance (Schmidt & Hunter, 2004 ). OB’s roots in psychology have shaped its research methods and aligned its culture of evidence largely with that of psychology, where use of meta-analysis is common. Say, for example, that 90 studies exist on the relationship of flexible work hours with staff retention and performance. Meta-analysis standards typically mandate examination of all 90 studies—whether published or not—to see what findings, if any, the studies together support and to examine the nature of any inconsistencies across the studies.

There is a world of difference between a systematic review of a body of studies (e.g., a meta-analysis) and a more casual or “unsystematic” literature review. A systematic review has a methods section that details how the review was conducted and what specific technical requirements were used (Briner & Denyer, chapter 7 of this volume). In contrast, conventional literature reviews are highly vulnerable to the biases authors display in their choice of studies to include. Studies included in conventional literature reviews reflect the author’s priorities and focus and, thus, may not represent the body of research. In conducting a systematic review of science-oriented studies, the following indicators of evidence quality are evaluated.

Construct validity: Is the purported phenomenon real? A basic requirement of evidence is construct validity, which asks whether the underlying notion or concept jibes with the observed facts. In the case of flexible hours, is there a set of common practices companies pursuing flexible hours actually use? Or do many different kinds of practices go by the label “flexible hours”? Do we have reason to treat the “flexible hours” of a 4/40 workweek as the same as the flexibility workers exercise over their own daily stop-and-start times? If research findings reveal that the 4/40 work week and personal control over work hours differ in their consequences for workers and employers, we are likely to conclude that “flexibility” in reality takes several distinct forms. As in the case of flexibility’s potential effects on worker motivation or company performance, any test of cause-effect relationship needs to first establish a clear meaning and construct validity for the concept of interest. In the case of flexibility, concepts of flexibility with clearer construct validity are “reduced hours”—where the hours worked are fewer than the normal work week—and “working-time control”—where workers exercise personal control over when they work (not how many hours per se ).

As illustrated, the term “flexible hours” can have so many different meanings that it is not a single coherent construct. Similar issues exist for popular notions like “morale” or “emotional intelligence,” phrases used colloquially to refer to a variety of things. Morale can mean group esprit de corps or individual satisfaction, each driven by very different forces in organizations. Similarly, emotional intelligence (EI) is used to refer to an emotional competency (Goleman, 1995 ) or a form of intelligence in social relations distinct from general intelligence (Mayer, Salovey & Caruso, 2000 ). Further, some object to equating emotion and reason, arguing that EI cannot be a form of intelligence (Locke, 2005 ). As with the preceding flexibility example, the key is to develop a clear definition of the construct being studied, so that the study’s findings can best be interpreted and used by others.

Because scholars tend to be concerned with construct clarity (terminology, definition, and distinctions), practitioners looking into the OB literature to answer a practice question usually need to try a variety of key words or seek out an academic for guidance, in order to identify the proper scientific terms (which may include some jargon specific to the field) that the relevant research uses (Werner, chapter 15 of this volume).

Internal validity: Do the observed effects or relationships indicate causality? Internal validity is the degree to which a study’s results are free of bias (Cook & Campbell, 1979 ). If bias cannot be ruled out, then any relationship we observe, such as a correlation between rewards and performance, may be due to measurement error, methodological problems, or some uncontrolled third variable like the state of the economy. It’s unlikely any single study will be bias-free. In contrast, several studies with different settings, methods, and so forth can cancel out potential biases. Internal validity is established when a body of studies show comparable findings across different research designs, such as experiments and longitudinal studies. As we are able to use these comparable findings to rule out the potential effects from measurement error, methodological problems, and other alternative explanations, it is more likely that the observed effect is real and caused by the particular factor(s) investigated.

External validity: How widespread is the effect? Why does it hold sometimes and not others? External validity (sometimes called generalizability) refers to the extent to which a result holds across populations, settings, procedures, and time periods (Cook & Campbell, 1979 ). A study might provide information about the conditions under which a phenomenon is likely to be observed or repeated elsewhere. Attention to the circumstances surrounding the finding helps us understand its generalizability and provides information regarding why a finding might apply in some circumstances and not others. Relevant details can tell us if there are conditions, not part of the phenomenon itself, which influence its occurrence or consequences. Such is the case where the effects of rewards on performance depend on the way rewards are distributed (to all employees vs. only high performers vs. various employees, but unsystematically, Lawler, 1971 ; 1990 ) or the extent to which the effects of high-involvement work systems depend on appropriate workforce training and rewards (cf. MacDuffie, 1995 ). Another way context impacts generalizability is by changing the meanings people give to the event, behavior, practice, or phenomenon studied. Prior events or historical factors, such as a previously failed change, can lead an otherwise promising practice to fail because people view the new practice through the lens of that previous failure. Or, society itself can give the phenomenon a distinct meaning: how people experience “close supervision” in the relatively authoritarian culture of Turkey is likely to differ from egalitarian Norway (House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, 2004 ). The same set of directive behaviors from a boss might appropriately coordinate work in one culture but be viewed as controlling micro-management in the other.

Criteria for Practice-Oriented OB Evidence

The goals of practice-oriented research are to identify what works (or doesn’t) in real-life settings and to learn which circumstances affect how those practices work. Both scholars and practitioners conduct practice-oriented research. Scholars seek to obtain information on how practitioners approach the decisions they make and the actions they take. Practitioners conduct their own research, often in the form of pilot tests or evaluation studies, to gauge the impact of a company policy or program. Practice-oriented research is directed toward particular problems and settings that practitioners care about. Design science’s collaborations among academics, end users, and an organization’s technical experts are a form of practice-oriented research (Van Aken & Romme, chapter 3 of this volume). Key criteria for practice-oriented evidence are discussed next.

Detailed description: What are the conditions of practice? Practice-oriented evidence is useful in part because it describes what practitioners actually do and the conditions under which they do it. Data can be gathered in many ways: via interviews, observations, and surveys, in forms both qualitative and quantitative. Perlow’s ( 1997 ) study of how a company implemented its flexibility policy used interviews and observations. This study uncovered how employees received mixed signals about the acceptability of flexibility and the role that position and status in the company played in determining whose requests for flexibility were granted.

Another example of practice-oriented research is investigations of how practitioners actually use an evidence-based process. Pritchard, Harrell, DiazGranadeos & Guzman ( 2008 ) investigated why differences existed in the results of an organizational analysis and assessment system known as PROMES. Their investigation revealed the kinds of implementation behaviors that affected PROMES’s outcomes. The extent to which PROMES implementers adhered to the system’s specified procedures affected their overall productivity gains, as did the quality of the information they provided the organization.

Given the widespread variation in how organizations implement routines (e.g., performance appraisals) or interventions (e.g., quality programs) there is a lot of value in practitioner-oriented studies that examine how sensitive the expected outcomes are to whether practitioners adhere to specified procedures. In medical research, for example, practice-oriented research indicates that diabetics who adjust or fine-tune their regimen for self-testing and administering insulin enjoy better health outcomes than those strictly following their clinicians’ orders (e.g., Campbell et al., 2003 ). Despite this example, noncompliance with standard procedures can be associated with poorer outcomes as in the case of PROMES just mentioned. Practice-oriented research provides crucial information about the sensitivity of interventions and practices to variability in compliance.

The variability in adherence to prescribed processes and procedures is referred to as implementation compliance . Implementation compliance is a major issue in implementing evidence-based practices. In the case of PROMES, consultants and managers who implemented the technique but did not fully follow its standard instructions oversaw programs with fewer performance gains than did those who adhered more closely to the specified PROMES procedures. Companies that follow fads have been known to “implement the label” but not the actual practices on which the evidence is based. So-called engagement or talent management programs, for example, might really be the same old training and development activities the company has always followed, with a catchy new name. Attention to the actual activities implemented is critical to understanding what works, what doesn’t, and why.

Real-world applicability: Are the outcome variables relevant to practice ? Practice-oriented research focuses on end points that are important to managers, customers, employees, and their organizations. In recent years, research/practice gaps in health care have been reduced by more patient-oriented research, tapping the patient outcomes that clinicians and their patients care about, such as morbidity, mortality, symptom reduction, and quality of life. This focus on practice-oriented outcomes in medicine contrasts with the theory-centric outcomes of science- (or disease-) oriented medical research. In the latter, outcomes typically take the form of specific physiological indicators (e.g., left ventricular end-diastolic volume or the percentage of coronary artery stenosis [Ebell, Barry, Slawson, & Shaughnessy, 1999 ]). Similarly, practice-oriented OB evidence includes outcomes of practical significance, such as the level of savings or improved employee retention, data often available from an organization’s own records. In contrast, theory-centric outcomes in OB research might include interpersonal organizational citizenship behavior or employee role-based self-efficacy, typically using indicators that academics have developed.

As part of his executive master’s thesis, banker Tom Weber took up the challenge of testing whether a leadership training program for the bank’s managers would actually change their behavior and the bank’s performance. In contrast to the typical large sample sizes of academic research, this study relied on numbers more typical of the bank’s actual training programs. Using a sample of 20 managers, 9 were randomly assigned to the training group, and the remainder to the control group, which received no training. To provide the kind of support training often required in a busy work setting, leadership development (“the treatment”) consisted of a one-day group session followed by four individual monthly booster sessions. Results demonstrated that subordinates of the trained managers reported increases in their managers’ charisma, intellectual stimulation, and consideration than did subordinates of control-group managers. Using archival data from his bank’s branches, Weber found that the training led to increased personal loan and credit card sales in the branches supervised by the trained managers. These outcomes were selected for their real-world relevance, rather than theoretical interest (cf. Verschuren, 2009 ). This study, undertaken because a practicing manager questioned the practical value of transformational leadership training, ultimately was published in a major research journal (Barling, Weber, & Kelloway, 1996 ).

Effect size: How strong is the effect or relationship? The effect size is a measure of the strength of the relationship observed between two variables (Hedges & Okin, 1985 ). It is a statistical criterion useful to practitioners and academics. Academic researchers rely on effect sizes to interpret experimental results. For example, where two or more treatment conditions are manipulated, effect sizes can tell which treatment is more powerful. Effect sizes are also central to meta-analyses and allow comparison of the relative effects of several factors (e.g., whether personality or intelligence is more important to worker performance).

From a practice perspective, a large effect size for the relationship between mental ability and job performance means that increasing the general intelligence of the workforce can have substantial impact on worker contributions to the firm. Small effect sizes can mean that practitioners looking for an intervention that improves outcomes ought to look elsewhere. Such is the case in a study of software engineering, where a collection of technologies used in actual projects had only a 30 percent impact on reliability and no effect on productivity (Card, McGarry, & Page, 1987 ). Instead, human and organizational factors appear to have stronger effects on software productivity than tools and methods (Curtis, Crasner, & Iscoe, 1988 ).

In the context of practice, effect sizes are often most useful when judged in relation to costs. Even a small effect can be important in practice. If it can be gained at minimal cost, it may be worth the slight effort required. For example, it is relatively easy to create a general sense of group identity (where co-workers in a department view themselves as an in-group, distinct from others). Group identity is positively related to willingness to help peers (and negatively related to helping outsiders.). Its benefits (and costs) are relatively easy to induce, one reason why logos and group nicknames are so popular (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000 ). Systematic research reviews can be very useful to practice when they provide both effect sizes and cost/benefit information. Now we turn to the kinds of well-established findings OB research produces.

Some Well-Established OB Findings

The primary knowledge products of OB research are principles , that is, general truths about the way the world works. Massive amounts of data have been accumulated and integrated to develop these principles, each of which sums up a regularity manifest in organizations and their members. For purposes of this chapter, a few well-established OB principles are summarized to illustrate OB’s relevance to the practice of EBMgt. (Additional evidence-based OB principles are summarized in Cialdini, 2009 ; Latham, 2009 ; and Locke, 2009 ).

Readers will note that these principles take one of two forms. The majority are forms of declarative knowledge (“what is”)—facts or truth claims of a general nature, such as the goal-setting principle, “Specific goals tend to be associated with higher performance than general goals” (Latham, 2009 ). Less often, these principles represent procedural knowledge (“how to”); these are task behaviors or applications found to be effective in acting on the general principle or fact. As an example, take the finding, “The goal and the measure of performance effectiveness used should be aligned,” as is the case when a goal of 15 percent increase in logger productivity is measured as the number of trees cut down divided by the hours it takes to cut down those trees (Latham, 2009 , p.162). By its very nature, declarative knowledge tends to be general and applicable to lots of different circumstances. Specific goals can take many forms across countless work settings. In contrast, procedural knowledge is more situation-specific and may need to be adapted as circumstances change (Anderson, 2010 ). In some situations, no single goal may be adequate to reflect productivity, and thus more than one measure of performance effectiveness may need to be used.

Making Decisions

Decision making is a fundamental process in organizations. Making decisions is the core activity managers perform. A prominent principle in management education is bounded rationality: Human decision makers are limited in the amount of information they can pay attention to at one time and in their capacity to think about and process information fully (Simon, 1997 ). Indeed, such are the limits of individual decision-making capabilities that having too much choice tends to keep people from making any decision at all (Schwartz, 2004 , pp. 19–20). Schwartz’s research demonstrated that giving shoppers at an upscale grocery only six choices (in this case, of jam) increased the likelihood that they would choose to buy some, in contrast to giving them 24 choices. In the case of Schwartz’s study of customer choices, these findings also have practical utility in terms of both boosting sales and making the best use of shelf space.

The pervasive effects of bounded rationality make it necessary for EBMgt practices to be structured in a fashion that is compatible with our cognitive limits as human beings. To aid more systematic and informed decisions, another evidence-based principle of a procedural nature applies, that is, develop and use a few standard but adaptable procedures or tools to improve the success of organizational decisions (Larrick, 2009 ). Decision supports are pragmatic tools that can be designed to aid practitioners in making evidence-informed decisions. A checklist, for example, might use Yates’s 10 Cardinal Rules (Yates, 2003 ; Yates & Potwoworski, chapter 12 of this volume) as steps to follow in making a good decision. Evidence-informed decision-making procedures need to be simple to use, because complexity or perceived difficulty can keep people from using them. Contemporary medical practice has numerous decision supports (Gawande, 2009 ) such as patient care protocols, handbooks on drug interactions, online decision trees, and specific tests indicating whether a course of treatment applies. In contrast, business practices in OB’s domain appear to make limited use of decision supports (e.g., hiring, giving feedback, running meetings, dealing with performance problems, etc.).

Hiring Talent