Ask the publishers to restore access to 500,000+ books.

Internet Archive Audio

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Pathways 2: reading, writing, and critical thinking

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

5 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station14.cebu on March 10, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- Email Sign-Up

We can't find what you're looking for.

Please try your search again.

Liberal Arts ITS Digital Audio Catalog

- ar-0-27 Elementary Modern Standard Arabic

- ch-0-02 Chinese Pin Yin and Writing

- ch-1-01 Listening Comprehension

- ch-1-02 Reading Quiz

- ch-1-05 Chinese 412K Language Lessons

- ch-1-06 Integrated Chinese, Level 1

- ch-1-07 Integrated Chinese: Level 2 - Part 1

- ch-2-35 Language Lessons

- ch-2-36 Language Lessons

- ch-2-37 Language Lessons

- ch-2-38 Homework Exercises

- ch-2-39 Business Chinese

- ch-2-40 Close the Deal

- ch-2-41 Business Chinese for Success - Real Cases from Real Companies

- dn-0-10 Aktivt dansk

- en-0-04 New Person to Person 1

- en-0-05 Fundamentals of English Grammar - Fourth Edition

- en-0-09 Grammar Sense 2; Second Edition

- en-0-10 All Clear 1: Listening and Speaking, Second Edition

- en-0-11 Reading Explorer 5

- en-0-55 New Interchange 3

- en-0-60 The Oxford Picture Dictionary

- en-0-61 Accurate English

- en-0-62 The Idiom Adventure - Fluency in Speaking and Listening

- en-0-64 New Interchange 2

- en-0-66 Illustrated Everyday Idioms with Stories 2

- en-0-67 Person to Person 1 - Communicative Speaking and Listening Skills - Third Edition

- en-0-68 All Clear 3, Listening and Speaking, Second Edition

- en-0-69 For Your Information 2: Reading and Vocabulary Skills, Second Edition

- en-0-70 Longman Introductory Course for the TOEFL Test: IBT

- en-0-71 Well Said - Second Edition

- en-0-72 Oxford Picture Dictionary, Second Edition

- en-0-73 Mosaic One Reading - Silver Edition

- en-0-74 Well Said: Pronunciation for Clear Communication, Third Edition

- en-0-75 Grammar Dimensions 3: Form, Meaning, and Use, Fourth Edition

- en-0-76 Grammar Dimensions 4 - Form, Meaning, and Use, Fourth Edition

- en-0-77 Sound Concepts: An Integrated Pronunciation Course

- en-0-78 Communicating on Campus

- en-0-80 Longman Introductory Course for the TOEFL Test - Second Edition

- en-0-81 Grammar Sense 4; Second Edition

- en-0-82 More Speak English Like an American; First Edition

- en-0-83 NorthStar 1: Listening and Speaking, 2nd Edition

- en-0-84 NorthStar 2: Listening and Speaking, 3rd Edition

- en-0-85 World Languages - Key Concepts 1: Listening, Note Taking, and Speaking Across the Disciplines

- en-0-86 Active Skills for Reading: Intro, 2nd Edition

- en-0-87 Let's Talk 1: Second Edition

- en-0-88 Let's Talk 2: Second Edition

- en-0-89 Grammar and Beyond: Class Audio CD 1

- en-0-90 Express to the TOEFL iBT Test

- en-0-91 Short Cuts: An Interactive English Course, Book I

- en-0-92 Can You Believe It? - Book 2

- en-0-93 Active Skills for Reading: Intro, 3rd Edition

- en-0-94 Well Said: Pronunciation for Clear Communication, 4th Edition

- en-0-95 Cambridge IELTS Trainer

- en-0-96 Focus On Acedemic Skills for IELTS

- en-0-97 Pathways 1: Reading, Writing, and Critical Thinking

- en-0-98 Grammer in Context 1 - Sixth Edition

- en-0-99 Grammar Explorer 3

- en-0-100 TOEFL iBT Prep Plus - 2018-19

- en-1-16 Quest: Listening and Speaking in the Academic World, Book 2

- en-1-40 Can You Believe It? - Stories and Idioms from Real Life - Book 2

- en-1-41 The Idiom Advantage: Fluency in Speaking and Listening

- en-1-44 Quest: Listening and Speaking in the Academic World, Book 1

- en-1-45 Join the Club, Book 1

- en-1-47 Grammar in Context 3, Third Edition

- en-1-50 Talk It Up! Listening, Speaking and Pronunciation

- en-1-51 Talk It Over! Listening, Speaking, and Pronunciation, 2nd Edition

- en-1-52 Talk It Through! Listening, Speaking, and Pronunciation

- en-1-53 Grammar Sense 3

- en-1-55 New Interchange 3

- en-1-56 Focus on Grammar - A High-Intermediate Course for Reference and Practice

- en-1-57 Grammar Links 2, 2nd Edition

- en-1-58 NorthStar 5: Listening and Speaking, 3rd Edition

- en-1-61 North Star Listening and Speaking High Intermediate, Second Edition

- en-1-62 Zero In! Phrasal Verbs in Context - Intermediate

- en-1-63 Focus on Grammar: An Intermediate course for Reference and Practice - Second Edition

- en-1-64 Focus on Grammar: A High-Intermediate Course for Reference and Practice, 2nd Ed.

- en-1-65 In No Time Flat!

- en-1-66 Grammar Sense 3

- en-1-67 Grammar in Context 2 - Fourth Edition

- en-1-68 Grammar in Context 3 - Fourth Edition

- en-1-69 College Oral Communication 4

- en-1-70 Hot Topics 2

- en-1-71 Quest: Listening and Speaking, Book 1 - Second Edition

- en-1-72 Quest: Listening and Speaking, Book 2 - Second Edition

- en-1-73 Touchstone Level 4

- en-1-74 Interactions Access: A Listening/Speaking - Silver Edition

- en-1-75 Interactions Access: A Listening/Speaking - Silver Edition

- en-1-76 World Class Reading 3 - A Reading Skills Text

- en-1-77 Open Forum 2 - Academic Listening and Speaking

- en-1-78 College Oral Communication 2

- en-1-79 College Oral Communication 3

- en-1-80 Grammar in Context 3 - Fifth Edition

- en-1-81 Can You Believe It? - Stories and Idioms from Real Life - Book 3

- en-1-82 Lecture Ready 2: Strategies for Academic Listening, Note-taking, and Discussion

- en-1-83 Grammar Sense 2

- en-1-84 Grammar in Context 2 - Fifth Edition

- en-1-85 Grammar and Beyond Class 3

- en-1-90 Learning English for Academic Purposes

- en-1-91 Real Reading 1: Creating an Authentic Reading Experience

- en-1-92 NorthStar 1: Listening and Speaking, Third Edition

- en-1-93 NorthStar 2: Listening and Speaking, 4th Edition

- en-1-94 Active Skills for Reading: One, Third Edition

- en-1-95 Real Reading 3: Creating an Authentic Reading Experience

- en-1-96 Academic Encounters Level 3: Life in Society

- en-1-97 21st Century Communication - Listening, Speaking, and Critical Thinking 4

- en-1-98 Oxford Picture Dictionary, Third Edition

- en-1-99 Pathways 3: Reading, Writing, and Critical Thinking

- en-1-100 Academic Encounters Level 2 Listening and Speaking - 2nd Edition

- en-1-101 Fifty-Fifty, A Speaking and Listening Course: Book One, 3rd Edition

- en-2-02 Grammar Sense 3

- en-2-03 Clear Speech: Pronunciation and Listening Comprehension in North American English 4th Edition

- en-2-06 Speaking Solutions

- en-2-12 Clear Speech: Pronunciation and Listening in North American English, Second Edition

- en-2-16 All Clear Book: Idioms and Context

- en-2-26 Focus on Grammar - An Advanced Course for Reference and Practice

- en-2-28 All Clear!: Advanced

- en-2-33 North Star Listening and Speaking Advanced, Second Edition

- en-2-36 New Person to Person 2

- en-2-44 Person to Person 2 - Communicative Speaking and Listening Skills - Thrid Edition

- en-2-45 Clear Speech - Third Edition

- en-2-53 Join the Club - Book 2

- en-2-54 Consider the Issues: Listening and Critical Thinking Skills

- en-2-55 True Colors 4

- en-2-56 Longman - Preparation course for the TOEFL Test - Next Generation iBT

- en-2-57 Quest: Listening and Speaking in the Academic World - Book 3

- en-2-58 Focus on Grammar 1 - Second Edition

- en-2-59 Focus on Grammar 2 - Third Edition

- en-2-60 Focus on Grammar 3 - Third Edition

- en-2-61 Focus on Grammar 4 - Third Edition

- en-2-62 Focus on Grammar 5 - Third Edition

- en-2-63 Touchstone

- en-2-64 Key Concepts 2 - Listening, Note Taking, and Speaking Across the Disciplines

- en-2-65 Quest: Listening and Speaking, Book 3 - Second Edition

- en-2-66 Lecture Ready 3: Strategies for Academic Listening, Note-Taking, and Discussion

- en-2-67 Longman - Preparation course for the TOEFL Test - Test: iBT, Second Edition

- en-2-68 All Clear 2 - Listening and Speaking, Third Edition

- en-2-69 Interactions 1 Listening and Speaking: Silver Edition

- en-2-70 Open Forum 3 - Academic Listening and Speaking

- en-2-71 Real Talk 1 - Authentic English in Context

- en-2-72 Speechcraft: Workbook for International TA Discourse

- en-2-73 Speechcraft: Workbook for Academic Discourse

- en-2-74 Grammar Form and Function - Book 2, Second Edition

- en-2-75 Grammar Form and Function - Book 3, Second Edition

- en-2-76 Communication Strategies 4

- en-2-77 Speechcraft: Discourse Pronunciation for Advanced Learners

- en-2-78 Speak English Like an American

- en-2-79 Understanding and Using English Grammar - Fourth Edition

- en-2-80 Reading Explorer 2

- en-2-81 Grammar Sense 4: Advanced Grammar and Writing

- en-2-82 Reading Explorer 3; First Edition

- en-2-83 NorthStar 3: Listening and Speaking, Third Edition

- en-2-84 Pathways: Listening, Speaking, and Critical Thinking - Level 3

- en-2-85 Focus on Grammar 1 - 3rd Edition

- en-2-86 Focus on Grammar 2 - 4th Edition

- en-2-87 Focus on Grammar 3 - 4th Edition

- en-2-88 Focus on Grammar 4 - 4th Edition

- en-2-89 North Star 4: Listening and Speaking, 3rd Edition

- en-2-90 Focus on Grammar 5 - 4th Edition

- en-2-91 Let's Talk 3: Second Edition

- en-2-92 NorthStar 4: Listening and Speaking, Fourth Edition

- en-2-93 NorthStar 5: Listening and Speaking, Fifth Edition

- en-2-94 Grammar Sense 1, Second Edition

- en-2-95 Reading Explorer 5, Second Edition

- en-2-96 21st Century Commincation Level 1: Listen, Speaking and Critical Thinking

- en-2-97 21st Century Commincation Level 2: Listen, Speaking and Critical Thinking

- en-2-98 21st Century Commincation Level 3: Listen, Speaking and Critical Thinking

- en-2-99 Pathways 4: Reading, Writing, and Critical Thinking

- en-2-100 Grammar and Beyond Class Audio 4

- en-2-101 Pathways 3: Listening, Speaking, and Critical Thinking, Second Edition

- en-2-102 Accurate English ESL: A Complete Course in Pronunciation

- en-2-103 Pathways 1: Listening, Speaking, and Critical Thinking, Second Edition

- en-2-104 Pathways 2: Reading, Writing, and Critical Thinking, Second Edition

- en-2-105 Pathways 4: Listening, Speaking, and Critical Thinking, Second Edition

- en-2-106 Pathways 2: Listening, Speaking, and Critical Thinking, Second Edition

- fr-0-01 Intrigue

- fr-1-01 Intrigue

- fr-2-05 Sons et sens - La prononciation du français en contexte

- fr-2-08 À votre tour!

- fr-2-15 Les Six Amis

- fr-2-65 French Basic Course

- fr-2-66 French Basic Course

- fr-2-69 Advanced Oral Expression

- fr-2-71 Advanced Oral Expression

- fr-2-89 Savoir Dire, First Edition

- fr-2-94 Savoir Dire, Second Edition

- fr-2-95 Rencontres au Père Tranquille

- fr-9-03 Poémes Choisis

- gr-0-05 Deutsch: Na klar! An Introductory German Course - Fourth Edition

- gr-2-02 Zertifikat Deutsh für den Beruf

- it-0-22 Italiano in Diretta

- it-0-30 In giro per l'Italia: A Brief Introduction to Italian

- it-0-31 In giro per l'Italia: A brief Introduction to Italian - Second Edition

- it-2-02 In viaggio: Moving Toward Fluency in Italian

- jp-0-02 Yookoso! An Invitation to Contemporary Japanese, Second Edition

- jp-0-03 Yookoso! An Invitation To Contemporary Japanese, Third Edition

- jp-2-01 Yookoso!

- jp-2-02 An Integrated Approach to Intermediate Japanese

- jp-2-13 Getting Down to Business: Japanese for Business People

- jp-2-19 An Integrated Approach to Intermediate Japanese (Revised Edition)

- cc-6-02 Classics of Latin Poetry and Prose by Caesar, Cicero, Catullus, Horace and Vergil

- mm-0-02 Malayalam: A University Course and Reference Grammar

- ps-0-22 Golestan (Dibache)

- ps-0-27 Persian for America(ns)

- ps-1-10 Persian audio for 312L

- ps-2-02 Ri Ri

- ps-2-09 A Stone on a Grave

- ps-2-25 Tajiki Textbook and Reader

- qe-0-01 An Introduction to Spoken Bolivian Quechua

- rs-0-01 Russian Stage One: Live from Moscow

- rs-2-26 Play

- sk-0-03 Intro to Sanskrit

- sp-0-21 Puntos de Partida, 7th edition

- sp-0-22 Impresiones - Introductory Spanish, First Edition

- sp-2-06 Punto y Aparte

- sp-2-09 Curso de Fonética y Fonología Españolas

- sp-2-23 Spanish Pronunciation

- sp-2-61 Advanced Oral Expression for Teachers

- el-cid Cantar de Mio Cid

- sw-0-09 Nybörjarsvenska

- sw-0-10 Uttalsövningar

- tm-0-02 Tamil Pronunciation

- tr-0-02 Turkish Volume 1: Basic Course

- tr-0-03 Turkish 1: A Communication Approach

- tr-2-09 Readings

- tr-2-10 Readings

- ur-0-06 Let's Study Urdu

- ur-1-111 Speech 2

pathways 3 reading writing and critical thinking answer key pdf

Pathways 3 Reading, Writing, and Critical Thinking Answer Key. seen a widespread change in attitudes toward. urbanization.) 2. b (Explanation: This closeness reduces the cost of. transporting goods, people, and ideas, and allows. people to be more productive.) 3. a (Explanation: …cities tend to produce fewer.

This document is an answer key for a reading, writing, and critical thinking pathway. It provides answers and explanations for questions about a reading on urbanization and collecting standardized information on cities with populations over 20 million. The reading discusses how collecting this information can help understand challenges faced by growing cities and potential solutions.

Pathways LS Student Book Level 3 Unit 1 Sample Unit pathways reading, writing, and critical thinking answer key pathways reading, writing, and critical thinking

Students practice the critical thinking skill introduced in the Understanding the Reading section in Reading 1. • Have students work in pairs to look back at Reading 2 and find a sentence that is certain and one that is less certain.

Pathways 3 (2e) Reading, Writing, And Critical Thinking - Free ebook download as PDF File (.pdf) or read book online for free.

Access-restricted-item true Addeddate 2023-03-17 22:20:22 Autocrop_version ..14_books-20220331-.2 Boxid IA40872208 Camera Sony Alpha-A6300 (Control) Collection_set printdisabled External-identifier urn:lcp:pathwaysreadingw0000mari_f3s5:epub:fd1be63b-b003-41c4-a78a-8000df424694 urn:lcp:pathwaysreadingw0000mari_f3s5:lcpdf:9f2d2689-8e9a-4386-95d1-ffbc1e770efe Foldoutcount 0 Identifier ...

Pathways, Second Edition, is a global, five-level academic English program. Carefully-guided lessons develop the language skills, critical thinking, and learning strategies required for academic success. Using authentic and relevant content from National Geographic, including video, charts, and other infographics, Pathways prepares students to work effectively and confidently in an academic ...

This document contains the answer key for a vocabulary extension activity in a Pathways Reading, Writing, and Critical Thinking student book. It lists vocabulary words and their corresponding answers across 10 units.

Notes /type/text Access-restricted-item true Addeddate 2024-02-13 22:17:35 Autocrop_version ..14_books-20220331-.2 Bookplateleaf 0002 Boxid IA40917320 Camera USB PTP Class Camera Collection_set printdisabled External-identifier urn:lcp:pathways3reading0000nati:epub:25eb3658-da18-4063-87af-3d33aae84afd urn:lcp:pathways3reading0000nati:lcpdf:020fef6d-3d73-4b72-9d60-4ba830d27a37 Foldoutcount 0 ...

Carefully-guided lessons develop the language skills, critical thinking, and learning strategies required for academic success. Using authentic and relevant content from National Geographic, including video, charts, and other infographics, Pathways prepares students to work effectively and confidently in an academic environment.

Pathways Reading, Writing, and Critical Thinking is a best-selling, five-level academic skills series that combines highly visual, real-world content and rigorous language instruction to help students develop the skills, language, and critical thinking they need for academic success. Exploring academic topics through authentic readings, videos, photos, and infographics, students connect to ...

Pathways is National Geographic's new four-level academic skills series that features reading & writing and listening & speaking strands to help learners develop the language and skills needed to achieve academic success.

Pathways is National Geographic Learning's reading and writing skills series that helps learners develop the language skills needed to achieve academic success. Learners develop academic literacy skills through content, images, and video from National Geographic. This innovative series provides learners with a pathway to success!

Pathways 3 Reading, Writing, and Critical Thinking Answer Key National Geographic Learning 2. consumption; majority 3. phenomenon; increasingly (Note: The plural of phenomenon is phenomena.)

Pathways 3 RW - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free.

Request A Spark Trial View Sampler Contact A Rep Overview Downloads Components View Sampler

Source: Andrey Rudakov. Far away in the Kaluga Oblast, about a hundred miles from Moscow, retired armed forces captain Andrey Davydov has built his own village.

Kaluga Oblast - Overview Kaluga Oblast is a federal subject of Russia located in the center of the European part of the country, about 94 km south-west of Moscow, part of the Central Federal District. Kaluga is the capital city of the region.

Report with financial data, key executives contacts, ownership details & and more for Stroikeramika ZAO (Kaluga Oblast) in Russia. Report is available for immediate purchase & download from EMIS.

Exam test pathways reading, writing, and critical thinking answer key pathways reading, writing, and critical thinking answer key unit social relationships

File tài liệu, đáp án,... pathways reading, writing, and critical thinking answer key pathways reading, writing, and critical thinking answer key unit happiness

Pathways is National Geographic's new four-level academic skills series that features reading & writing and listening & speaking strands to help learners develop the language and skills needed to achieve academic success

Kaluga Oblast is a region in Central Russia, bordered by Bryansk Oblast to the southwest, Smolensk Oblast to the northwest, Moscow Oblast to the northeast, Tula Oblast to the east, and Oryol Oblast to the southeast.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- 110 Baker St. Moscow, ID 83843

- 208.882.1226

A Classical & Christ-Centered Education

Secondary Curriculum

The secondary school is divided into two stages… grades 7-8 (the Logic Stage) and grades 9-12 (the Rhetoric Stage).

In grades 7-8, the students take the mastered information from the Grammar Stage and bring it into ordered relationships. Students begin to apply logic, assessing the validity of arguments and learning to view information critically with more discerning minds.

In grades 9-12, students learn to articulate eloquently and persuasively, and to use the tools of knowledge and understanding acquired in the earlier stages. This is the point at which the strength of a classical education is made fully visible.

Click here for an overview of the Logos School secondary curriculum.

Click for our 2-page School Profile

The Knight’s Creed and Commitment

Class Schedules

Spring 2024 Finals Schedule 7th-12th grades only.

24-25 Fall Class Schedule 7th-12th grades only.

Senior Course Options:

By the time students reach their senior year in high school, they have usually developed interests in specific areas. Therefore, they will be given the opportunity to pursue those areas through the following senior course options. These options are designed to allow students the opportunity to learn one or two subjects well. As Dorothy Sayers says, “Whatever is mere apparatus may now be allowed to fall into the background, while the trained mind is gradually prepared for specialization in the “subjects” which, when the Trivium is completed, it should be perfectly well equipped to tackle on its own.” (from The Lost Tools of Learning) These options should aid the transition from the completion of the Trivium to the more specialized study that is a part of a college or university education.

Option 1: College or Online Class

This is a 1 credit option in which a student enrolls in a college or online class. Approved subjects include math, science, theology, humanities, and fine arts. The class must be taken for credit and the student must submit a transcript to receive credit toward Logos graduation. Areas of study that do not qualify are recreational classes and/or self-guided courses with little accountability.

Option 2: Internship

The internship is a 1/2 credit option intended to provide seniors with the opportunity to study a career. Students must work a minimum of 2 hours per week on their internship. A variety of internships have been approved in the past (interning with an elementary or secondary Logos teacher, riding along with police officers, observing at a local vet clinic, etc.). Students are not allowed to be paid for the time they spend as an intern. Parents are responsible to provide oversight and any necessary supervision or screening (background checks, etc.) for this experience.

Procedures for Both Options

1. At least two weeks before the beginning of each semester, students must submit a written proposal to the principal, via email. Late proposals will not be considered. Proposals must describe the following:

a. the main purpose of and goals for the program

b. the work that the student will be doing weekly to achieve these goals (include the website link for online classes)

c. the number of hours per week that the student will be participating in the program

2. Students have two days to resubmit proposals that have been denied.

Guidelines for Both Options

1. Credit will not be granted for work completed before a proposal is approved.

2. Students will receive a grade of E, S, or U at the end of each quarter and semester.

3. Failure to make satisfactory progress in the first semester will disqualify the student from participating in these programs during the second semester.

4. Students may only request approval for one semester at a time.

Dialectic Speech Meet

The following is information for the Dialectic Speech Meet for the 7 th -9 th grade students. Most of the work and grading is done during English class. For the final meet onwards, the students will perform their pieces with students from other classes in the same category. That afternoon during 7 th period there will be an assembly to hear the top performances from each category.

- Mid-December – information goes home

- Mid-January – Selections are due

- Toward the end of January – Piece is presented for a grade

- Beginning of February – Speech Meet

Dialectic Speech Meet Guidelines Dialectic Speech Meet Judge’s Form Dialectic Speech Meet Selection Ideas

Rhetoric Speech Meet

The following is information for the upcoming Rhetoric Speech Meet for the 10 th -12 th grade students. Please note a few differences between the Dialectic Speech Meet of the 7 th -9 th graders and the Rhetoric Speech Meet:

- Poetry must be through the Poetry Out Loud program.

- Readers Theater and the Original Oratory categories are allowed.

- Children’s books and plays are allowed as sources for material.

- There is no memory check. Pieces will be presented once in class for a grade, and once at the meet for a test grade.

- Mid-September – Information goes home.

- Beginning of October – Selections are due.

- Mid-October – The piece is presented for a memory grade.

- Beginning of November– Speech Meet

Guidelines Judging Form Selection Ideas

Scriabin Association

Founded to celebrate scriabin, scriabinism and scriabinists…, the texts of scriabin’s works: some observations of a performer-researcher-teacher. by simon nicholls.

The handwriting of any individual is a kind of self-portrait, and reading a handwritten letter can give an indication of the writer’s character and state of mind, and of his or her attitude to the content of the letter. An author’s manuscript often yields valuable information about the creative process; the manuscripts of Dickens or Dostoevsky provide many examples. Examining such a document is a very different experience from reading a novel in cold print. With a musical manuscript, the spacing, the character of the pen-strokes and of the musical handwriting, as well as details of layout which cannot always be exactly reproduced by the process of engraving, give similar information, valuable to the student and to the performer. Beyond factual information, the visual impression of the manuscript, the Notenbild , can be a direct stimulus from the composer to the interpreter’s imagination. In this way, study of the composer’s manuscript can lead both to a narrowing of the possibility of textual error and to a widening of the possibilities of imaginative response to interpretation.

Examining the manuscripts of any great composer or literary author is always a thrilling experience. I have spent many hours studying Scriabin’s manuscripts in the Glinka Museum, Moscow, which holds in its vast archive many fair and rough copies of complete works as well as sketches by Scriabin. The first thing which strikes one is the extreme beauty and clarity of the scores. The slender exactitude of the writing and drawing corresponds to the delicacy and transparency of Scriabin’s own playing of his music, and makes it clear to the interpreter that a similar clarity, precision and grace is demanded in his or her own performance – something extremely difficult to achieve. The care with which the manuscripts were prepared confirms the testimony of Scriabin’s friend and biographer, Leonid Sabaneyev, who was bemused by the care taken by the composer in the placing of slurs, the choice of sharps or flats in accidentals (contributing in many cases to an analysis of the harmony concerned), the spacing of the lines of the musical texture over the staves and the upward or downward direction of note stems.

It was Heinrich Schenker who pointed out the expressive and structural significance of the manuscript notation of Beethoven, and who was instrumental in establishing an archive in the Austrian National Library, Vienna, of photographic reproductions of musical manuscripts. His pioneering work has led gradually to the present wealth of Urtext editions and facsimiles of many composers’ manuscripts. Reproductions of Skryabin’s manuscripts have been published by Muzyka (Moscow), Henle (Munich) and the Juilliard School (New York; their manuscript collection is available online). [1] These reproductions cover several significant compositions by Scriabin: Sonata no. 5, op. 53; Two pieces, op. 59; Poème-nocturne, op. 61; Sonata no. 6, op. 62; Two poèmes, op. 63; Sonata no. 7, op. 64. The remarks below have no pretensions to system or completeness; they are merely observations based on initial study, and intended as a stimulus to others to examine the manuscripts for themselves.

In maturity, Scriabin took immense care with his manuscripts. Speaking to Sabaneyev, he compared the difficulty of writing down a conception in sound to the process of rendering a three-dimensional object on a flat surface. As a student and as a young composer, though, Scriabin was by no means ideally accurate or painstaking in his notation. This was the cause of Rimsky-Korsakov’s irritated response to the manuscript score of Scriabin’s Piano Concerto – the elder composer initially considered it to be too full of mistakes to be worthy of serious attention. Mitrofan Belaieff, Scriabin’s publisher, patron and mentor, frequently begged the composer to be more careful in correcting proofs. The original editions, particularly of the early works, contain many errors which originate in some cases from Scriabin’s manuscript and in others from poor proofreading – as far as we can tell; some early manuscripts are now lost.

We are indebted to the fine musician Nikolai Zhilyayev for correct editions of Scriabin’s music. Zhilyayev knew Scriabin well and discussed many misprints with the composer; others he detected by his own scrupulous and scholarly work and prodigious memory. As Scriabin’s harmony and voice-leading were impeccably systematic and logical at all stages of his development, those who have had to do with the old editions will know that is often possible to correct mistakes by analogy or knowledge of harmonic style.

Zhilyayev was the revising editor for a new edition of Scriabin’s music, published by the Soviet organisation Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo muzykal’nyi sektor (State publisher, musical division – ‘Muzsektor’) from the 1920s on, each work or opus number being issued separately. These beautifully prepared editions are painstakingly annotated, corrections being indicated in two layers: those discussed with the composer and therefore beyond doubt, and those which Zhilyayev considered likely (and he was usually right). This work was the basis of the complete edition of the piano music published by Gosudarstvennoe muszykal’noe izdatel’stvo (State musical publishing house – ‘Muzgiz’) in three volumes (1947, 1948 and 1953). [2] Zhilyayev fell victim to Stalin’s terror; he was arrested in 1937 and shot in the following year. His name does not appear on this three-volume edition.

A new complete edition is appearing gradually under the imprint Muzyka–P. Jurgenson. The general editor is Valentina Rubtsova, biographer of Scriabin and head of research at the Scriabin Museum, Moscow, assisted by Pavel Shatsky. As in Rubtsova’s editions for Henle, full credit is given to Zhilyayev, and the annotations as to origins and variants are very thorough in this valuable new edition.

A very limited number of Scriabin’s manuscripts has been available in facsimile until now. The collection of ‘Youthful and Early Works’ prepared by Donald Garvelmann and published in New York in 1970 by Music Treasure Publications [3] contains a facsimile of the early E flat minor sonata (without opus number) of 1889, a typical youthful manuscript of the composer, rather heavy in its style of penmanship. The manuscript of the op. 11 preludes (excerpts are shown in ill.1), though tidier, shows a similar style.

ill. 1) Extract of Op. 11 Preludes manuscript

The Russian website ‘Virtual’nye vystavki’ (‘Virtual exhibitions’) [4] gives in facsimile the first page of the Etude op. 8 no. 12, with more fingering than is shown in the Belaieff edition, and also the first page of the manuscript score of the Poem of Ecstasy , providing a striking example of the change in the composer’s manuscript style. A facsimile on the site of the first two pages of the score of the Piano Concerto shows some of the copious blue-pencilling of Rimsky-Korsakov from the occasion mentioned earlier, and the site also reproduces Skryabin’s letter of apology to Rimsky-Korsakov apologising for the errors and blaming neuralgia. [5] Comparison of this letter with the one to the musicologist N. F. Findeizen dated 26 December 1907, also viewable on the site, gives another clear example of the change in Scriabin’s handwriting. [6]

Op. 53: Sonata no. 5

A facsimile of the Fifth Sonata has been published by Muzyka. [7] The manuscript of this work was presented to the Skryabin Museum, Moscow, by the widow of the pianist and composer Alfred Laliberté, to whom Scriabin had given the manuscript. This is a very different document from the early E flat minor sonata manuscript, and shows Scriabin’s fastidious and calligraphically exquisite mature hand. By this time both Scriabin’s music manuscript and his handwriting had developed an elongated ‘upward-striving’ manner. We might make a comparison with the remark of Boris Pasternak that the composer ‘had trained himself various kinds of sublime lightness and unburdened movement resembling flight’ [8] – the handwriting is expressive of this quality. Examples of Scriabin’s handwriting in letters to Belaieff in 1897 (ill. 2) and to the composer and conductor Felix Blumenfeld in 1906 (ill. 3) show the dramatic difference in handwriting style that developed.

ill. 2) Scriabin’s handwriting 1897

ill. 3) Scriabin’s handwriting 1906

The manuscript of the Fifth Sonata shows that, although Scriabin spoke French, he did not immediately provide a French text for the epigraph, which is from the verse Poem of Ecstasy . This poem was written in Russian at the same period that the symphonic poem was composed. There is a request on the manuscript to the engraver to leave space for a French version. The French text, which is the usual source of English translations, does not reflect the Russian with complete accuracy: the forces mystérieuses , ‘mysterious forces’, which are being called into life are skrytye stremlen’ya , ‘hidden strivings’, in the original. [9] In other words, it is open to doubt that any sort of ‘magical ritual’, in a superstitious sense, is being depicted in this work, a suggestion made (perhaps in a figurative sense) by the early writer on Scriabin Evgenii Gunst and elaborated upon by the composer’s British-American biographer, Alfred Swan. The epigraph may be regarded as an invocation of Scriabin’s own inner aspirations, the creative power which the composer equated with the divine principle.

Work on the Fifth Sonata started in 1907, at a period when a rift had developed between Scriabin and the publishing house of Belaieff. The committee running the publishers after the death of Belaieff had proposed a renegotiation of fees. It is possible that Scriabin was unaware of the preferential and generous treatment Belaieff had accorded him; certainly, he was offended by the proposals and withdrew from his agreement with the publishers. The Sonata was published at Scriabin’s own expense, but was taken into the publishing concern run by the conductor Serge Koussevitsky, Rossiiskoe muzykal’noe izdatel’stvo (RMI). Later still, Scriabin quarrelled with Koussevitsky too, and the composer’s last works were published by the firm which had brought out his very first published compositions, Jurgenson.

The main differences between the manuscript of the Fifth Sonata and most modern printed texts are:

1) a missing set of ties at the barline between bars 98 and 99. These ties are also missing in RMI, and in the edition printed at Scriabin’s own expense. [10] Muzgiz adds the ties in dotted lines, by analogy with the parallel passage at bars 359–360. The commentary to the Muzgiz edition states that sketches of the work make use of an abbreviated notation at this point which could have led to this misunderstanding, as the editors describe it. Christoph Flamm’s notes to the Bärenreiter edition are definite as to Scriabin’s intention not to tie over this barline, citing the repetition of accidentals in bar 99 as being conclusive proof. [11]

2) the movement of the middle voice in bars 122–123, 126–127, 136–137, 383–384, 387–388, 397–398 ( Meno vivo sections): the manuscript gives a downward resolution in the middle voice (d flat – c in the first passage and g flat – f in the second) whereas the printed editions give an upward resolution (d flat – d natural and g flat – g). It is as if only at a second attempt (as revised for the printed version) has Scriabin fully realised the implications of his own (then very new) harmony: the resolutions as printed resolve into the augmented harmony around them, whereas the resolutions in the earlier version do not. Knowing about this early version, moreover, adds point to the grandiose version of the same section at bars 315–316, 319–20 and 323–324, where the downward resolution is retained. One might think of the meno vivo sections as being potential states, and the grandiose version as representing a fully realised condition.

It should be remembered that the Sonata was composed at breakneck speed, completed in a few days, and revised afterwards; Valentina Rubtsova, editor of the facsimile, suggests that the manuscript provides a glimpse into the composer’s creative laboratory. She further points out that Scriabin uses double barlines to indicate structural divisions, whereas publishers’ house style often requires a double bar at any change of key-signature or time-signature. This has resulted in the insertion of a number of non-authentic double bars in some published versions of the Fifth Sonata. Double bars occur in the manuscript in the following places only:

before bar 47 (beginning of main sonata exposition)

before bar 120 ( Meno vivo , the second subject area)

before bar 367 (indicating, perhaps a slight hesitation before this rising sequence)

before bar 381 (parallel passage to bar 120).

The visual effect of the manuscript is therefore more continuous than that of the printed edition. It should be mentioned that the Urtext printed version given in the volume containing the manuscript is a corrected version of the RMI edition. This edition was prepared with the composer’s agreement and during his lifetime. The manuscript, though, is an invaluable source for the reasons given above.

A similar use of double barlines to that in the Sonata no. 5 is made elsewhere by Scriabin, including in the Sonata no. 6 (see below) and the Sonata no. 8. It can be said, from these examinations, that Scriabin uses double barlines structurally or even expressively, and that they often should be made audible in some way, in sharp contradistinction to the purely ‘grammatical’ double bars referred to above. The definition of ‘sometimes’ and ‘often’ is a non-scientific one and comes down to the player’s own interpretive insight, but where there is a double barline and no change of time- or key-signature, the double bar clearly has structural significance.

The addition of a double bar by a publisher can confuse the interpreter. For example, Bach’s engraved edition of his own Second Partita has no double bar, in fact no barline at all, at the beginning of the third section of the Sinfonia (ill. 4.) The insertion of a double bar at this point, even in some ‘Urtext’ editions (because of the change of time-signature) leads many performers to treat the final chord of the middle section like a ‘starter’s pistol’ for the quicker final section, which, as consideration of the musical content will quickly demonstrate, starts on the second quaver of the bar with the fugue subject.

ill. 4) Manuscript of Sinfonia from Bach’s Keyboard Partita no. 2

The notes by Valentina Rubtsova to the facsimile of the Fifth Sonata mention Scriabin’s differing use of rallentando in its full version and of the abbreviation rall. , and the possible implications of such usage for performance:

[…] in b. 382 Scriabin indicated molto rallentando , while in b. 386 and 390 he confined himself to [a] shortened and somewhat careless rall. It seems that the theme sounded to him just like that: with a more substantial broadening in b.382 and in a somewhat generalized manner in b. 386 and 390. [12]

A related expressive function of details in the writing of performance directions will be noted below in the case of the Poème-Nocturne , op. 61.

Now we move to a group of Scriabin’s manuscripts, recently published on line by the Juilliard School of New York. The works with opus numbers 52, 53 and 58 to 64 were published by Koussevitsky’s firm, RMI, mentioned above. (The Poem of Ecstasy , op. 54, was already contracted to Belaieff, as were opp. 56 and 57; there is no work with the number 55.) Opp. 59 and 61 to 64 (op. 60 is an orchestral score, Prometheus ) were bound together in one volume at some time. Koussevitsky’s archive went with him when he left Russia in 1920. The majority of the archive is now in the Library of Congress, but this volume somehow came onto the open market, and was sold at Sotheby’s in 2000. The purchaser, Bruce Kovner, businessman, collector and philanthropist, generously donated his entire collection to Juilliard School in 2006, and Juilliard have made the contents of the volume he purchased available in excellent facsimile online [13] – a huge step forward in making Scriabin manuscript facsimiles available to the musical public. The Sonata No. 7 has also been published in an equally excellent facsimile by Henle with informative notes by Valentina Rubtsovsa. [14] Some observations on these manuscripts follow.

Op. 59 no. 1, Poème

b. 15: an accidental is missing before the r. h. d sharp, third quaver of the bar. This mistake, as well as the missing accidental in b. 13, was reproduced in the first edition, but corrected by Zhilyayev.

b.19: the fifth quaver in r. h. is spelled in the manuscript as b double flat, harder to read than the a natural printed in most editions, but consistent with the d flat bass of this bar and typical of Scriabin’s fastidiousness in his choice of accidentals. The spelling was reproduced in the first edition, but altered without comment by Zhilyayev, who did not have the manuscript available. (This manuscript was also not available to the editors at the time of preparation of the Muzyka-Jurgenson edition.) Subsequent editions, including Muzyka-Jurgenson, followed Zhilyayev’s reading. The ‘spelling’ of a note may well have an effect on the player of a wind or string instrument as regards actual pitch, and Sabaneyev discussed this with Scriabin. But a good pianist will often respond by minute adjustments of touch to the difference of inner hearing caused by enharmonic differences of spelling. [15]

b. 23–25: there is evidence in these bars of erased octave doublings in the right hand phrases, though the lower octave to the initial a, r.h. second quaver of bar 23, has not been erased – a mistake rightly queried by the editor. Here, the texture is delicate and transparent, but it will be remembered that Scriabin often preferred single notes to octaves in passages of powerful sonority where an effect of brightness was desirable (e.g. final climaxes of the Fifth Sonata and Vers la Flamme ). Sabaneyev criticised the composer for scoring his orchestral music with doublings at the unison rather than the octave, but this seems to have been Scriabin’s preference in many places.

b. 28 and 30: The three r.h. quavers which continue the middle voice at the end of these bars were first written by Scriabin in the upper staff, but then erased and put into the lower staff, clarifying the voice-leading. This is an example of the care taken by the composer in the optical presentation of his voices.

b. 34: the manuscript and the first edition have d natural in r.h. upper voice, second, fourth and sixth quavers. This error was corrected by Zhilyayev, who changed these notes to d sharps, noting the analogy in bar 6.

b. 36: the tie between third and fourth quavers of the bar in r.h. is missing in the manuscript, but was supplied in the first edition – possibly a correction in proof by the composer.

b. 38: the acciaccatura at the beginning of the bar for both hands was written by Scriabin with a quaver tail without the customary cross-stroke. This seems to have been the composer’s usual habit – compare the beginning of the Sixth Sonata, written in the same way, as well as other instances – and, in the case of the present Poème, the notation was altered in the first edition. The RMI edition of the Sonata, however, shows the acciaccatura with a quaver-type tail, though many later editions add a cross-stroke. It may be felt that in both cases Scriabin’s notation may suggest a more deliberate execution of the acciaccaturas.

b.39: note the beautiful and unusual notation of the final sonority, a single stem uniting sounds many octaves apart and played by two hands. It is suggestive of the deep and strange sonority of this ending. It is given by most editions, but not by Peters, who ‘normalise’ the notation here. [16]

Op. 59 no. 2, Prelude

A number of errors in the manuscript were correctly questioned by the editor, and further inconsistencies were corrected by Zhilyayev.

The rhythm at the beginning of bar 40, though, (marked avec defi – Scriabin omitted the acute accent on the second letter of défi ) written as three even quavers, was retained in the first edition and subsequent ones despite having been questioned by the editor. Muzgiz, following Zhilyayev, queries whether it should be made consistent with the dotted rhythm of other similar bars. The Peters edition by Günter Philipp adopts this suggestion. [17] The present writer is of the opinion that the three even quavers help to express Scriabin’s suggested ‘defiance’.

Intriguingly, a slip of paper was pasted over the original manuscript at bars 26–28. This is at the position, characteristic of Scriabin’s short pieces, where the opening material begins to be repeated in transposition. The repeated chords on the paper slip, which anticipate the coda from bar 54 to 57, may have been a late compositional addition by Scriabin. (Other paper slips are observable, pasted into the manuscript of the Sonata no. 6.)

Op. 61, Poème-Nocturne

(The manuscript of this work was also not available to the editors of Muzyka-Jurgenson, who were, however, able to consult a rough draft, as in the case of op. 59.)

Space will not permit a detailed analysis of longer works such as this, but some interesting features present themselves. The first page of the manuscript is written in two inks, blue and black. On the first system, the clefs and the r.h. phrase from the downbeat of bar one are written in blue, whereas the upbeat is written in black. A list of incipits for projected works by Scriabin exists in the Glinka Museum archives, and has been examined by the present writer. This list corresponds to a description by Sabaneyev of a collection of thematic material ‘for sonatas’. In the list, the Poème-Nocturne theme lacks its upbeat. Perhaps the addition of the upbeat was a late inspiration, like Beethoven’s last-minute addition of a two-note upbeat to the slow movement of the Hammerklavier sonata. At the recapitulation, b. 109, the theme starts on the downbeat.

In bar 3 and the corresponding passage, bar 110, Scriabin writes the molto più vivo directly over the l. h. figure on the second beat. This is placed too late in Muzgiz, but correctly in Muzyka-Jurgenson.

Scriabin’s usual practice is to write his performance directions or remarki in lower-case letters, but in the Poème-Nocturne and some other works this practice is departed from in certain places. The new ideas at bar 29 and 33 are marked in the manuscript Avec langueur and Comme en un rêve – suggesting, perhaps, that the arrival of these new ideas should be ‘shown’ by the player in some way, possibly by a very slight elongation of the rests before them, as with the start of a new sentence or paragraph in a text which is read aloud. The same thing happens at Avec une soudaine langueur ( sic ) in bar 52, and Avec une passion naissante and De plus en plus passionné in bars 77 and 79. The first edition reproduces this peculiarity, but not Muzgiz or Muzyka-Jurgenson. It has not been possible to determine whether they are following Zhilyayev, as seems likely. [18]

The addition in printed editions, including the first, of a poco acceler. [ sic in RMI] over the barline of bb. 46-47 is clear evidence of intervention by the composer at proof stage.

The long slur at comme un murmure confus (bar 103 to 110) is correctly reproduced in the editions known to this writer, but seeing it drawn so clearly and with such certainty in the manuscript is a reminder not to yield to the temptation to ‘explain’ the structure of this mysterious passage, and especially not to render the arrival of the recapitulation in bar 109 with any excessive degree of clarity. The piece reflects Scriabin’s exploration of states of consciousness on the borders of sleep, as he explained to Sabaneyev. On the other hand, the remarka at the point of arrival of the recapitulation ( Avec une grace [sic] capricieuse [19] ) does have the capital letter we have come to expect in this work when important thematic ideas are presented.

Op. 62: Sonata no. 6

This work is so successfully suggestive of dark areas of the spirit that a listener once suggested to the present writer, after a performance of the Sixth Sonata, that the music was evidence of psychosis in the composer’s own mind. The listener was, of course, making an error like that of Don Quixote at the puppet show – mistaking dramatic presentation for reality. The lucidity of the manuscript, as well as the highly organised and disciplined musical structure, show that Scriabin knew very well what he was doing.

Towards the end of the work there is a notorious high d written, which exceeds the range of the keyboard (bar 365). This note has also been quoted to me by music-lovers as evidence of Scriabin’s supposed delusional condition. Firstly, it should be pointed out that the d is dictated by analogy with bar 330. We can make a comparison with Ravel in this case. In the climax of Ravel’s Jeux d’eau there is a bottom note which, harmony dictates, should be G sharp, but as the note does not exist on most keyboards, Ravel wrote A. [20] Similarly, Ravel ‘faked’ octaves at the bottom of the piano in the recapitulation of Scarbo by writing sevenths. Scriabin, ever an idealist, preferred to write the pitch required by the music and to leave the solution to the interpreter. [21] Furthermore, the whole phrase from bar 365 to 367 is written an octave lower in the manuscript than in the first edition, thus bringing the d within the keyboard range. [22] An explanation for the late change between manuscript and first edition, which transposes the phrase up an octave, may be that Scriabin never performed this very difficult work – the premiere was entrusted to Elena Beckman-Shcherbina. Perhaps, in working on the piece with her and hearing the passage played up to tempo, Scriabin suggested that she try the phrase an octave higher, as the analogy with bar 330 demands, and realised that the chord flashes by with the substitution of c for d as the top note practically unheard. In her memoirs, Bekman-Shcherbina describes Scriabin’s detailed work with her on his compositions, but, alas, gives no details of the work which must have taken place on the Sixth Sonata.

The composer’s notation of the acciaccatura which starts the Sixth Sonata has already been mentioned (see above, Poème op 59 no. 1.) As in the case of the acciaccatura which sets off the Sonata in A minor by Mozart (K.310), this opening should not be played too glibly, but with a certain weight. Indeed, for a player whose hand cannot stretch the initial chords, it is a help to know that this arresting opening should not be hurried over. More importantly, an execution on the slow side helps to emphasise the sombre, unyielding severity of the opening sonority. It is perhaps unfortunate that publishers’ ‘house styles’ lead to a routine ‘correction’ of Scriabin’s notation of the acciaccatura.

‘House style’ has also led to the omission in some editions of the Sixth Sonata of a number of ‘structural’ double bars provided in the manuscript by Scriabin. Scriabin wrote double bars before b. 92 (coda of exposition), 124 (beginning of development), 206 (recapitulation), 268 (end of recapitulation of second subject. As this last-mentioned place involves a change of time signature, the double bar is technically required, and is reproduced in printed editions, but there is a definite break in the atmosphere here.) The calligraphic beauty and clarity of b. 244–267, a notoriously complex passage, repays study.

Op. 64: Sonata no. 7

The manuscript of Sonata no. 7 is commented upon in detail by Valentina Rubtsova in her notes to the facsimile published by Henle, and these notes are published online. [23] They repay careful study, and Rubtsova gives an account of the other manuscript versions of the Sonata, one of which the present writer has examined in the Glinka Museum. The existence of this text, with its many alterations and differences from the finished version, calls into question the accusation, made by Sabaneyev and since repeated, that Scriabin established a ‘scheme’ of empty numbered bars and proceeded to ‘fill’ it with music. While numbers were clearly important to the composer in establishing a ‘crystalline’ form, the procedure of composition was far more complex than that, as the painstaking work shown in these manuscripts reveals.

Ill.5 is a reproduction of the first page of Scriabin’s earlier draft, with the remarka ‘Prophétique’ for the opening ‘fanfare’ motive. This marking, later rejected, gives a sense of the gesture of this musical idea, which is essential to the close connection of the Sonata with Scriabin’s idea of the ‘Mystery’, something he discussed with Sabaneyev. While visiting an exhibition in London’s Tate Gallery of paintings by the English artist George Frederic Watts (1817–1904), the present writer was struck by the convulsive, ‘prophetic’ gesture depicted in Watts’ ‘Jonah’ (1894), a painting which is reproduced online. [24] The performance of these opening bars needs to be as striking and dramatic as Watts’ painting.

ill. 5) 1st page from manuscript of Sonata 7

Op. 63, 2 Poèmes

In the second of these short works, some l. h. notes in the chords in b. 6 and 7 have been erased; these notes are relocated to the upper stave, where they belong musically, and marked m.g. (The m.d. in bar 7 is a characteristic slip, rightly questioned by the editor). The top note of these chords is shown in the manuscript as f natural and was so published in the RMI edition. Zhilyayev, who had discussed this passage with the composer, corrected this to f sharp. [25] The first notation shows how essential the gesture of hand-crossing was to Scriabin’s conception of the sonority here. Some pianists make the simultaneity of sounding of notes into a priority, but a letter by Scriabin to Belaieff which has been dated to December 1894 shows that spreading of chords was essential to his conception at times (such spreading was, in any case, far more prevalent at that period than now). In this letter, Scriabin writes that the ‘wide chords’ in bb. 9-10 of the Impromptu op. 10 no. 2 ‘must be played by the left hand alone, for the character of their sonority in performance depends on this.’ [26]

The Scriabin facsimiles which have been made available in Russia and America are invaluable sources of information and inspiration, and studying them brings us just a little nearer to the composer. It is hoped that the notes above will encourage players and music lovers to investigate them, and also that more facsimiles may follow in the future.

Simon Nicholls, 2016.

[1] http://juilliardmanuscriptcollection.org/composers/scriabin-aleksandr/

[2] This edition was the basis of those of the sonatas, preludes and etudes reprinted by Dover, though some of the editions chosen for reprinting contained errors not present in the complete edition. Dover did not reproduce the essential information that nuances and rubatos given in brackets in these editions, notably in the op. 8 etudes, were from instructions given by Skryabin to Mariya Nemenova-Lunts while she was studying with the composer.

[3] This edition was republished in limited numbers by the Scriabin Society of the U.S.A.

[4] http://expositions.nlr.ru/ex_manus/skriabin/index.php

[5] The letter is dated ‘19 th April’ by Scriabin and dated to 1896 on the website. The edition by Kashperov of Scriabin’s letters (A. Scriabin, Pis’ma , Muzyka, Moscow, 1965/2003, attributes it to 1897 (p. 168–169, letter 144.)

[6] This letter is given by Kashperov ( op.cit. ) on p. 492–3, letter no. 545.

[7] Scriabin: Sonata no. 5, op. 53. Urtext and facsimile. Muzyka, Moscow, 2008.

[8] Boris Pasternak, An Essay in Autobiography , trans. Manya Harari, Collins and Harvill, London, 1959, p. 44.

[9] I am grateful to the distinguished scholar of Russian literature Avril Pyman for pointing this out (private communication). The French text was added by hand by the composer to the proofs of the first edition (information from the notes by Christoph Flamm to Skrjabin: Sämtliche Klaviersonaten II, Bärenreiter, 2009, p. 43), but perhaps we should trust Scriabin’s Russian, his native tongue, rather than his French in this case.

[10] Ibid. , p. 44.

[11] Muzgiz, vol. 3, commentary, p. 295. Christoph Flamm, loc. cit. The printed version supplied in the Muzyka edition of the facsimile adds the ties in dotted lines, following Muzgiz. It is certainly tempting to make the ‘correction’: most pianists play the tied version, which persists in many editions. But such bringing into line of parallel passages should not be done automatically.

[12] Valentina Rubtsova, notes to facsimile of Scriabin Sonata no. 5, p.57.

[13] Cf. n. 1, above.

[14] Alexander Skrjabin: Klaviersonate Nr. 7 op. 64. Faksimile nach dem Autograph. G. Henle Verlag, Munich, 2015. The foreword is also available online: http://www.henle.de/media/foreword/3228.pdf

[15] Cf. Paul Badura-Skoda, Interpreting Mozart on the Keyboard , trans. Leo Black, Barrie & Rockliff, London, 1962, p. 290 for a brief discussion of one example of this problem. Brahms wrote against any attempt to improve on Chopin’s orthography at the time of the preparation of a new complete edition of the Chopin piano works (letter to Ernst Rudorff, late October or early November 1877, quoted in Franz Zagiba, Chopin und Wien , Bauer, Vienna, 1951, p.130.) All this comment is made about a single accidental because the orthography of Scriabin’s late music is such a wide-reaching, fascinating and important topic, perhaps seen by some students of the music only as an irritating difficulty of reading, and this is one small example of it. For a discussion of Scriabin’s orthography and its significance see George Perle, ‘Scriabin’s Self-Analyses’, Music Analysis, Vol. 3 no. 2 (1984), p. 101–122.

[16] Skrjabin, Klavierwerke III , ed. Günter Philipp, Peters, Leipzig 1967.

[17] Ibid . Philipp notes the variant in an editor’s report, p. 98.

[18] Christoph Flamm discusses Scriabin’s remarki , and comments that the composer accepted with indifference the publishers’ treatment of his upper or lower-case letters ( op. cit. , p. 42). Nonetheless, these small ms. differences can be infinitely valuable suggestions to the performer. Flamm points out that even the size of the letters in which a remarka is written can be of significance for the performer.

[19] Scriabin spoke good French, but accents sometimes go missing in his writing. This circumstance could perhaps be compared with his tendency to miss out accidentals.

[20] The present writer has read a gramophone record review in which this famous bass note was described as a ‘wrong note.’

[21] The Austrian piano firm Bösendorfer added a few bass notes to the range of its largest instruments. Apart from making Ravel’s bass notes possible to ‘correct’, the bass strings add to the resonance of the piano. No such advantage attaches to an addition to the top of the keyboard.

[22] Noted by Darren Leaper.

[23] Cf. n. 15, above.

[24] http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/watts-jonah-n01636

[25] Muzgiz, vol. 3, commentary, p. 296.

[26] Kashperov, op. cit. , p. 87.

- Words, Language & Grammar

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Pathways: Reading, Writing, and Critical Thinking 2: Student Book 2A/Online Workbook 2nd Edition

- ISBN-10 133762490X

- ISBN-13 978-1337624909

- Edition 2nd

- Publisher Heinle ELT

- Publication date February 14, 2018

- Language English

- Dimensions 8.3 x 0.3 x 10.7 inches

- See all details

Customers who bought this item also bought

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Heinle ELT; 2nd edition (February 14, 2018)

- Language : English

- ISBN-10 : 133762490X

- ISBN-13 : 978-1337624909

- Item Weight : 13.6 ounces

- Dimensions : 8.3 x 0.3 x 10.7 inches

- #1,408 in Reading Skills Reference (Books)

- #3,448 in Foreign Language Instruction (Books)

- #3,534 in English as a Second Language Instruction

About the author

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read book recommendations and more.

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 80% 10% 4% 1% 5% 80%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 80% 10% 4% 1% 5% 10%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 80% 10% 4% 1% 5% 4%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 80% 10% 4% 1% 5% 1%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 80% 10% 4% 1% 5% 5%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

It came with the code, great

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

A Gentleman in Moscow: Q & A

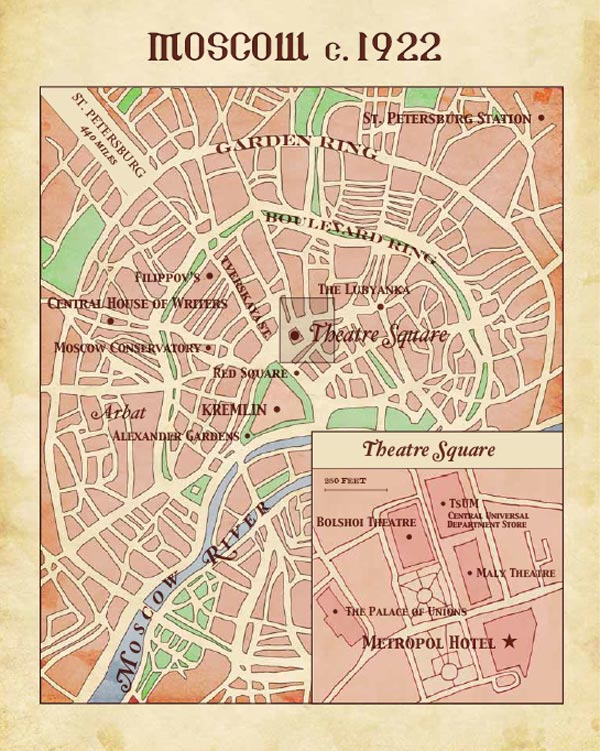

Click image to enlarge

For those who did not get to attend one of the events for A GENTLEMAN MOSCOW, you can watch my full speech here in which I discuss my novel, the history of the Metropol Hotel, and my writing process in some detail.

A GENTLEMAN IN MOSCOW tells the story of a Russian aristocrat living under house arrest in a luxury hotel for more than thirty years. What was the origin of the idea?

Over the two decades that I was in the investment business, I travelled a good deal for my firm. Every year, I would spend weeks at a time in the hotels of distant cities meeting with clients and prospects. In 2009, while arriving at my hotel in Geneva (for the eighth year in a row), I recognized some of the people lingering in the lobby from the year before. It was as if they had never left. Upstairs in my room, I began playing with the idea of a novel in which a man is stuck in a grand hotel. Thinking that he should be there by force, rather than by choice, my mind immediately leapt to Russia—where house arrest has existed since the time of the Tsars. In the next few days, I sketched out most of the key events of A Gentleman in Moscow ; over the next few years, I built a detailed outline; then in 2013, I retired from my day job and began writing the book.

What is the nature of your fascination with Russia?

I am hardly a Russologist. I don’t speak the language, I didn’t study the history in school, and I have only been to the country a few times. But in my twenties, I fell in love with the writers of Russia’s golden age: Gogol, Turgenev, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky. Later, I discovered the wild, inventive, and self-assured writing styles of Russia’s early 20 th century avant-garde including the poet Mayakovsky, the dancer Nijinsky, the painter Malevich, and the filmmaker Eisenstein. Going through those works, it began to seem like every accomplished artist in Russia had his own manifesto. The deeper I delved into the country’s idiosyncratic psychology, the more fascinated I became.

Kazan Cathedral is a perfect symbol of Russia’s mystique for me during the Soviet era. Built in 1636 on Red Square to commemorate both the liberation of Moscow from interlopers and the beginning of the Romanov dynasty, Kazan was among Russia’s oldest and most revered cathedrals. In 1936, the Bolsheviks celebrated the 300 th anniversary of its consecration by razing it to the ground. In part, they leveled the cathedral to clear Red Square for military parades, but also to punctuate the end of Christianity in Russia. But Peter Baranovsky, the architect who was directed to oversee the dismantling, secretly drafted detailed drawings of the cathedral and hid them away. More than fifty years later, when Communist rule came to its end, the Russians used Baranovsky’s drawings to rebuild the church stone for stone.

I find every aspect of this history enthralling. The cathedral itself is a reminder of Russia’s heritage—ancient, proud, and devout. Through the holy landmark’s destruction we get a glimpse of how ruthless and unsentimental the Russian people can be. While through the construction of its exact replica, we see their almost quixotic belief that through careful restoration, the actions of the past can effectively be erased. But most importantly, at the heart of this history is a lone individual who at great personal risk carefully documented what he was destroying in the unlikely chance that it might some day be rebuilt. The Soviet era abounds with sweeping cultural changes and with stoic heroes who worked in isolation at odds with the momentum of history towards some brighter future.

This is your second novel set in the first half of the 20 th Century. Can you talk about your interest in the period?

My interest in writing about the early twentieth century is neither a reflection of a love of history, nor a nostalgia for a bygone era. What has attracted me to the period is that it has a proximate distance to the present. It is near enough in time that it seems familiar to most readers, but far enough away that they have no firsthand knowledge of what actually happened. This provides me with the liberty to explore the narrow border between the unbelievably actual and the convincingly imagined.

I generally like to mix glimpses of history with flights of fancy until the reader isn’t exactly sure of what’s real and what isn’t. In terms of A Gentleman in Moscow , for instance, the launch of the world’s first nuclear power plant in Russia in 1954 is an historical fact, but the assembly of Party leaders to observe the blacking-out of Moscow is an invention. Similarly, the little copper plates on the bottom of antiques designating them as property of the People are a fact, while the wine bottles stripped of their labels are a fiction.

What sort of research did you do for the book?

Rather than pursuing research driven projects, I like to write from areas of existing fascination. Even as young man, I was a fan of the 1920s and 1930s, eagerly reading the novels, watching the movies, and listening to the music of the era. I used this deep-seated familiarity as the foundation for inventing my version of 1938 New York in Rules of Civility . Similarly, I chose to write A Gentleman in Moscow because of my longstanding fascination with Russian literature, culture, and history. Most of the texture of the novel springs from the marriage of my imagination with that interest. For both novels, once I had finished the first draft, I did some applied research in order to fine tune details.

What was the biggest challenge in writing the book?

Initially, I imagined that the central challenge posed by the book was that I was trapping myself, my hero, and my readers in a single building for thirty-two years. But my experience of writing the novel ended up being similar to that of the Count’s experience of house arrest: the hotel kept opening up in front of me to reveal more and more aspects of life.

In the end, a much greater challenge sprang from the novel’s geometry. Essentially, A Gentleman in Moscow takes the shape of a diamond on its side. From the moment the Count passes through the hotel’s revolving doors, the narrative begins opening steadily outward. Over the next two hundred pages detailed descriptions accumulate of people, rooms, objects, memories, and minor events, many of which seem almost incidental. But then, as the book shifts into its second half, the narrative begins to narrow and all of the disparate elements from the first half converge. Bit characters, passing remarks, incidental objects come swirling together and play essential roles in bringing the narrative to its sharply pointed conclusion.

When effective, a book like this can provide a lot of unexpected satisfactions to the reader. The problem is that the plethora of elements in the first half can bog readers down making them so frustrated or bored that they abandon the book. So, my challenge was to craft the story, the point of view, and the language in such a way that readers enjoy the first half and feel compelled to continue despite their uncertainty of where things are headed. Whether or not I succeeded in doing so is up to you.

Does the book have a central theme?

I certainly hope not. In crafting a novel, I do not have an essential message I am trying to communicate. Rather, I hope to create a work of art that, while being satisfyingly cohesive, contains such a richness of images, ideas, and personalities that it can prompt varied responses from reader to reader, and from reading to reading.

In essence, I want to gather together a pile of brightly colored shards of glass. But rather than assemble these shards into a mosaic with a fixed image, I want to drop them into the bottom of a kaleidoscope where, thanks to a glint of sunlight and the interplay of mirrors, they render an intricate beauty which the reader can reconfigure by the slightest turn of the wrist.

Can you describe your process?

My process for writing A Gentleman in Moscow was very similar to my process for writing Rules of Civility . In both cases, I designed the book over a period of years—ultimately generating a outline which detailed the settings, events, and interactions of characters, as well as the evolution of personalities and themes chapter by chapter. Once I’m ready to start writing, my goal is to complete the first draft in a relatively short period of time. Thus I wrote the first draft of Rules of Civility in a year and the first draft of Gentleman in Moscow in eighteen months.

While I’m working on my first draft I don’t share my work. But once I’ve completed that draft, I give it to my wife, my editor in New York, my editor in London, my agent, and four friends on the same day, asking that they give me feedback within three weeks. I then use their varied feedback to begin the revision process. For both books, I revised the initial draft three times from beginning to end over three years.

While I work with a very detailed outline, when the writing is going well it provides me with plenty of surprises. I was in the middle of writing the bouillabaisse scene in A Gentleman in Moscow , for instance, when I discovered that Andrey was a juggler. I was in the middle of drafting Sofia’s fitting, when I discovered (alongside the Count) that Marina had designed a dressless dress. And I was in the midst of the second or third draft when I noticed for the first time that moment in Casablanca when Rick sets upright the toppled cocktail glass.

Can you comment on the structure of the book?

As you may have noted, the book has a somewhat unusual structure. From the day of the Count’s house arrest, the chapters advance by a doubling principal: one day after arrest, two days after, five days, ten days, three weeks, six weeks, three months, six months, one year, two years, four years, eight years, and sixteen years after arrest. At this midpoint, a halving principal is initiated with the narrative leaping to eight years until the Count’s escape, four years until, two years, one year, six months, three months, six weeks, three weeks, ten days, five days, two days, one day and finally, the turn of the revolving door.

While odd, this accordion structure seems to suit the story well, as we get a very granular description of the early days of confinement; then we leap across time through eras defined by career, parenthood, and changes in the political landscape; and finally, we get a reversion to urgent granularity as we approach the denouement. As an aside, I think this is very true to life, in that we remember so many events of a single year in our early adulthood, but then suddenly remember an entire decade as a phase of our career or of our lives as parents.

How do you think of A GENTLEMAN IN MOSCOW in relation to RULES OF CIVILITY?

When I was deciding what to do after Rules , I picked A Gentleman from among a handful of projects I had been considering. In retrospect, I see that my choice was probably influenced by an unconscious desire for change, because the two novels are a study in contrasts. Where the former takes place over a single year, the latter spans thirty-two. Where the former roves across a city, the latter takes place in one building. Where the former is from the perspective of a young working class woman on the rise, the latter is from the perspective of an aging gentleman who has lost everything. And where the former is virtually free of children and parents, the latter is very much concerned with generational relationships. One last difference is that A Gentleman in Moscow is much longer than Rules of Civility ; but it has the same cover price, so you get 50% more words for your money!

Can you tell us a little about the Metropol Hotel?

The Metropol is a real hotel which was built in the center of Moscow in 1905 and which is still welcoming guests today. Contrary to what you might expect, the hotel was a genuine oasis of liberty and luxury during the Soviet era despite being around the corner from the Kremlin and a few blocks from the head quarters of the secret police.

Because the Metropol was one of the few fine hotels in Moscow at the time, almost anyone famous who visited the city either drank at, dined at, or slept at the Metropol. As a result, we have an array of firsthand accounts of life in the hotel from prominent Americans including John Steinbeck, e. e. cummings, and Lillian Hellman. You can survey these accounts and read a short history of the hotel at The Metropol section of this web site.

Are any of the characters in the novel based on real people?

None of the novel’s central characters are based on historical figures, or on people that I have known. That said, I have pick-pocketed my own life for loose change to include in the book such as these three examples: