Writing about COVID-19 in a college admission essay

by: Venkates Swaminathan | Updated: September 14, 2020

Print article

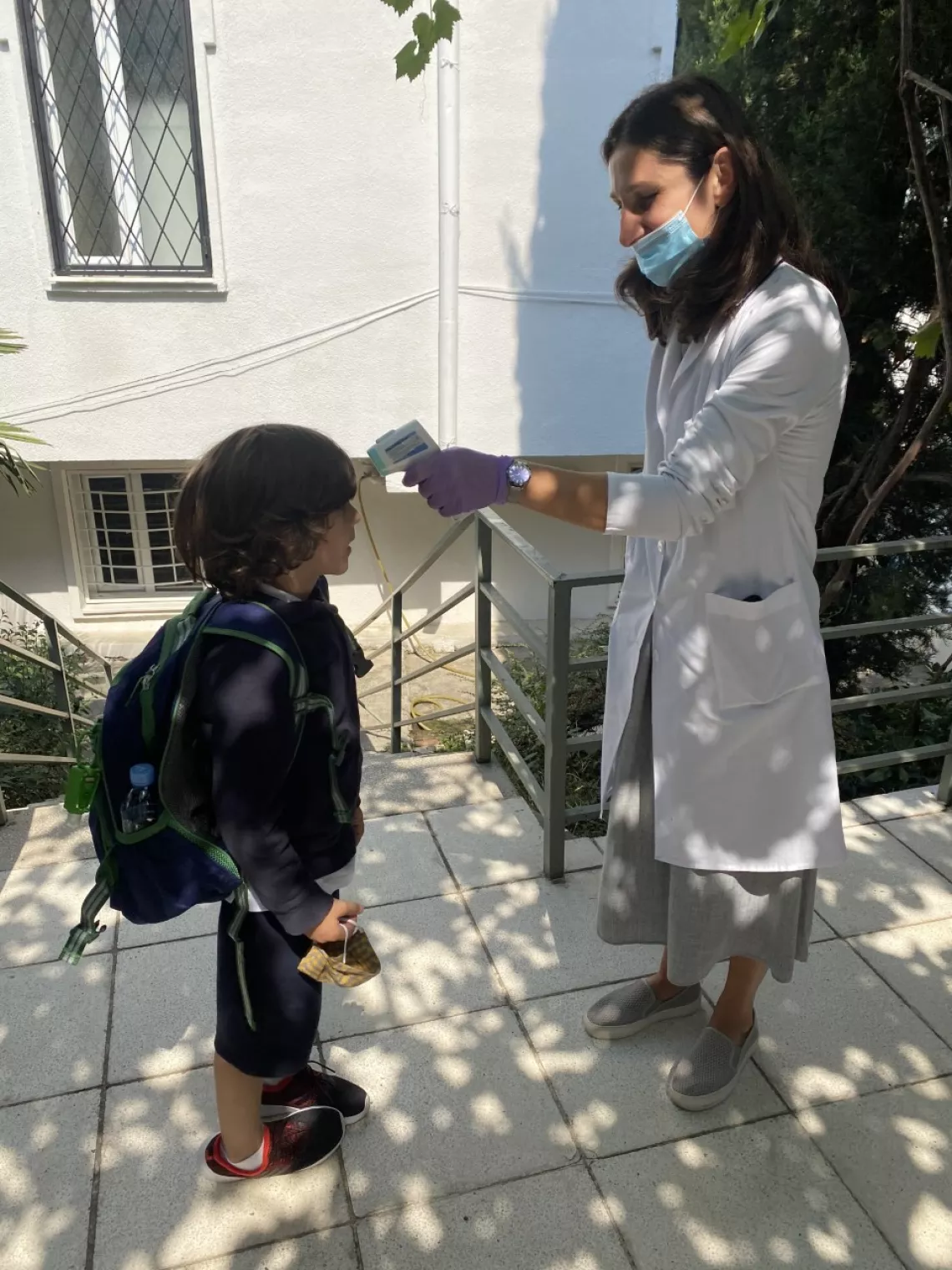

For students applying to college using the CommonApp, there are several different places where students and counselors can address the pandemic’s impact. The different sections have differing goals. You must understand how to use each section for its appropriate use.

The CommonApp COVID-19 question

First, the CommonApp this year has an additional question specifically about COVID-19 :

Community disruptions such as COVID-19 and natural disasters can have deep and long-lasting impacts. If you need it, this space is yours to describe those impacts. Colleges care about the effects on your health and well-being, safety, family circumstances, future plans, and education, including access to reliable technology and quiet study spaces. Please use this space to describe how these events have impacted you.

This question seeks to understand the adversity that students may have had to face due to the pandemic, the move to online education, or the shelter-in-place rules. You don’t have to answer this question if the impact on you wasn’t particularly severe. Some examples of things students should discuss include:

- The student or a family member had COVID-19 or suffered other illnesses due to confinement during the pandemic.

- The candidate had to deal with personal or family issues, such as abusive living situations or other safety concerns

- The student suffered from a lack of internet access and other online learning challenges.

- Students who dealt with problems registering for or taking standardized tests and AP exams.

Jeff Schiffman of the Tulane University admissions office has a blog about this section. He recommends students ask themselves several questions as they go about answering this section:

- Are my experiences different from others’?

- Are there noticeable changes on my transcript?

- Am I aware of my privilege?

- Am I specific? Am I explaining rather than complaining?

- Is this information being included elsewhere on my application?

If you do answer this section, be brief and to-the-point.

Counselor recommendations and school profiles

Second, counselors will, in their counselor forms and school profiles on the CommonApp, address how the school handled the pandemic and how it might have affected students, specifically as it relates to:

- Grading scales and policies

- Graduation requirements

- Instructional methods

- Schedules and course offerings

- Testing requirements

- Your academic calendar

- Other extenuating circumstances

Students don’t have to mention these matters in their application unless something unusual happened.

Writing about COVID-19 in your main essay

Write about your experiences during the pandemic in your main college essay if your experience is personal, relevant, and the most important thing to discuss in your college admission essay. That you had to stay home and study online isn’t sufficient, as millions of other students faced the same situation. But sometimes, it can be appropriate and helpful to write about something related to the pandemic in your essay. For example:

- One student developed a website for a local comic book store. The store might not have survived without the ability for people to order comic books online. The student had a long-standing relationship with the store, and it was an institution that created a community for students who otherwise felt left out.

- One student started a YouTube channel to help other students with academic subjects he was very familiar with and began tutoring others.

- Some students used their extra time that was the result of the stay-at-home orders to take online courses pursuing topics they are genuinely interested in or developing new interests, like a foreign language or music.

Experiences like this can be good topics for the CommonApp essay as long as they reflect something genuinely important about the student. For many students whose lives have been shaped by this pandemic, it can be a critical part of their college application.

Want more? Read 6 ways to improve a college essay , What the &%$! should I write about in my college essay , and Just how important is a college admissions essay? .

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

How our schools are (and aren't) addressing race

The truth about homework in America

What should I write my college essay about?

What the #%@!& should I write about in my college essay?

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

What Life Was Like for Students in the Pandemic Year

- Share article

In this video, Navajo student Miles Johnson shares how he experienced the stress and anxiety of schools shutting down last year. Miles’ teacher shared his experience and those of her other students in a recent piece for Education Week. In these short essays below, teacher Claire Marie Grogan’s 11th grade students at Oceanside High School on Long Island, N.Y., describe their pandemic experiences. Their writings have been slightly edited for clarity. Read Grogan’s essay .

“Hours Staring at Tiny Boxes on the Screen”

By Kimberly Polacco, 16

I stare at my blank computer screen, trying to find the motivation to turn it on, but my finger flinches every time it hovers near the button. I instead open my curtains. It is raining outside, but it does not matter, I will not be going out there for the rest of the day. The sound of pounding raindrops contributes to my headache enough to make me turn on my computer in hopes that it will give me something to drown out the noise. But as soon as I open it up, I feel the weight of the world crash upon my shoulders.

Each 42-minute period drags on by. I spend hours upon hours staring at tiny boxes on a screen, one of which my exhausted face occupies, and attempt to retain concepts that have been presented to me through this device. By the time I have the freedom of pressing the “leave” button on my last Google Meet of the day, my eyes are heavy and my legs feel like mush from having not left my bed since I woke up.

Tomorrow arrives, except this time here I am inside of a school building, interacting with my first period teacher face to face. We talk about our favorite movies and TV shows to stream as other kids pile into the classroom. With each passing period I accumulate more and more of these tiny meaningless conversations everywhere I go with both teachers and students. They may not seem like much, but to me they are everything because I know that the next time I am expected to report to school, I will be trapped in the bubble of my room counting down the hours until I can sit down in my freshly sanitized wooden desk again.

“My Only Parent Essentially on Her Death Bed”

By Nick Ingargiola, 16

My mom had COVID-19 for ten weeks. She got sick during the first month school buildings were shut. The difficulty of navigating an online classroom was already overwhelming, and when mixed with my only parent essentially on her death bed, it made it unbearable. Focusing on schoolwork was impossible, and watching my mother struggle to lift up her arm broke my heart.

My mom has been through her fair share of diseases from pancreatic cancer to seizures and even as far as a stroke that paralyzed her entire left side. It is safe to say she has been through a lot. The craziest part is you would never know it. She is the strongest and most positive person I’ve ever met. COVID hit her hard. Although I have watched her go through life and death multiple times, I have never seen her so physically and mentally drained.

I initially was overjoyed to complete my school year in the comfort of my own home, but once my mom got sick, I couldn’t handle it. No one knows what it’s like to pretend like everything is OK until they are forced to. I would wake up at 8 after staying up until 5 in the morning pondering the possibility of losing my mother. She was all I had. I was forced to turn my camera on and float in the fake reality of being fine although I wasn’t. The teachers tried to keep the class engaged by obligating the students to participate. This was dreadful. I didn’t want to talk. I had to hide the distress in my voice. If only the teachers understood what I was going through. I was hesitant because I didn’t want everyone to know that the virus that was infecting and killing millions was knocking on my front door.

After my online classes, I was required to finish an immense amount of homework while simultaneously hiding my sadness so that my mom wouldn’t worry about me. She was already going through a lot. There was no reason to add me to her list of worries. I wasn’t even able to give her a hug. All I could do was watch.

“The Way of Staying Sane”

By Lynda Feustel, 16

Entering year two of the pandemic is strange. It barely seems a day since last March, but it also seems like a lifetime. As an only child and introvert, shutting down my world was initially simple and relatively easy. My friends and I had been super busy with the school play, and while I was sad about it being canceled, I was struggling a lot during that show and desperately needed some time off.

As March turned to April, virtual school began, and being alone really set in. I missed my friends and us being together. The isolation felt real with just my parents and me, even as we spent time together. My friends and I began meeting on Facetime every night to watch TV and just be together in some way. We laughed at insane jokes we made and had homework and therapy sessions over Facetime and grew closer through digital and literal walls.

The summer passed with in-person events together, and the virus faded into the background for a little while. We went to the track and the beach and hung out in people’s backyards.

Then school came for us in a more nasty way than usual. In hybrid school we were separated. People had jobs, sports, activities, and quarantines. Teachers piled on work, and the virus grew more present again. The group text put out hundreds of messages a day while the Facetimes came to a grinding halt, and meeting in person as a group became more of a rarity. Being together on video and in person was the way of staying sane.

In a way I am in a similar place to last year, working and looking for some change as we enter the second year of this mess.

“In History Class, Reports of Heightening Cases”

By Vivian Rose, 16

I remember the moment my freshman year English teacher told me about the young writers’ conference at Bread Loaf during my sophomore year. At first, I didn’t want to apply, the deadline had passed, but for some strange reason, the directors of the program extended it another week. It felt like it was meant to be. It was in Vermont in the last week of May when the flowers have awakened and the sun is warm.

I submitted my work, and two weeks later I got an email of my acceptance. I screamed at the top of my lungs in the empty house; everyone was out, so I was left alone to celebrate my small victory. It was rare for them to admit sophomores. Usually they accept submissions only from juniors and seniors.

That was the first week of February 2020. All of a sudden, there was some talk about this strange virus coming from China. We thought nothing of it. Every night, I would fall asleep smiling, knowing that I would be able to go to the exact conference that Robert Frost attended for 42 years.

Then, as if overnight, it seemed the virus had swung its hand and had gripped parts of the country. Every newscast was about the disease. Every day in history, we would look at the reports of heightening cases and joke around that this could never become a threat as big as Dr. Fauci was proposing. Then, March 13th came around--it was the last day before the world seemed to shut down. Just like that, Bread Loaf would vanish from my grasp.

“One Day Every Day Won’t Be As Terrible”

By Nick Wollweber, 17

COVID created personal problems for everyone, some more serious than others, but everyone had a struggle.

As the COVID lock-down took hold, the main thing weighing on my mind was my oldest brother, Joe, who passed away in January 2019 unexpectedly in his sleep. Losing my brother was a complete gut punch and reality check for me at 14 and 15 years old. 2019 was a year of struggle, darkness, sadness, frustration. I didn’t want to learn after my brother had passed, but I had to in order to move forward and find my new normal.

Routine and always having things to do and places to go is what let me cope in the year after Joe died. Then COVID came and gave me the option to let up and let down my guard. I struggled with not wanting to take care of personal hygiene. That was the beginning of an underlying mental problem where I wouldn’t do things that were necessary for everyday life.

My “coping routine” that got me through every day and week the year before was gone. COVID wasn’t beneficial to me, but it did bring out the true nature of my mental struggles and put a name to it. Since COVID, I have been diagnosed with severe depression and anxiety. I began taking antidepressants and going to therapy a lot more.

COVID made me realize that I’m not happy with who I am and that I needed to change. I’m still not happy with who I am. I struggle every day, but I am working towards a goal that one day every day won’t be as terrible.

Coverage of social and emotional learning is supported in part by a grant from the NoVo Foundation, at www.novofoundation.org . Education Week retains sole editorial control over the content of this coverage. A version of this article appeared in the March 31, 2021 edition of Education Week as What Life Was Like for Students in the Pandemic Year

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

“I miss my school!”: Examining primary and secondary school students’ social distancing and emotional experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic

Verena letzel-alt.

1 Section for Teacher Education and Research, University of Trier, Universitätsring 15, 54296 Trier, Germany

Marcela Pozas

2 Professional School of Education, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Unter den Linden 6, 10099 Berlin, Germany

3 School of Psychology, University of Monterrey, Monterrey, Mexico

Christoph Schneider

With the rapid spread of Covid-19, countries around the world implemented strict protocols ordering schools to close. As a result, educational institutions were forced to establish a new form of schooling by implementing emergency remote education. Learning from home during the Covid-19 pandemic brought numerous changes, challenges, and stressors to students’ daily lives. In this context, major concerns have been raised based on the reports of students’ negative experiences resulting from social distancing and isolation. Given the impact of Covid-19 on many aspects of students’ lives, in particular their social and school experiences, research that provides insights into the consequences of this health crisis for students’ well-being has become important. This study aims to explore students’ experiences of social distancing and its relation to their negative emotional experiences during Germany’s first Covid-19–related school closure. Findings indicate that both primary and secondary students missed their friends and classmates and that primary school students perceived higher levels of social distancing. However, a linear regression analysis indicated that the older the students were, the more negatively affected they were by social distancing. The implications of the study’s results and further lines of research are discussed.

With the rapid spread of the Coronavirus (Covid-19), governments around the world imposed restrictions in order to reduce the risk of infection (UNESCO, 2020 ). Among these restrictions, social distancing became the most recommended measure, fundamentally affecting people’s lives (Greenhow & Chapman, 2020 ). Across media, social distancing was labeled as the new normal, while scientific literature defined it as the subjective perceived distance to a person or to members of a group (Beck, 2020 ). In the face of such a public health crisis, in which social distancing was compulsory, nearly all countries worldwide had to abruptly close their schools in March 2020. These immediate measures severely affected the education sector (Education International, 2020 ; Wyse et al., 2020 ), forcing educational institutions to establish a new form of schooling by implementing emergency remote education (ERE) (Bozkurt & Sharma, 2020 ). Students had to learn from home and utilize digital media to learn and study, while school administrators and teachers had to transition to an online environment within a very short amount of time (Wolff et al., 2020 ). Homeschooling, in the form of ERE during the Covid-19 pandemic can be defined as a form of distance learning organized by schools, supported by teachers, and accompanied by parents (Meyer, 2020 ). For a limited amount of time, an individual home-learning situation takes the place of learning in classrooms or learning groups. It is important to note that homeschooling as a response to the Covid-19 pandemic should not be confused with the concept of homeschooling widely known in the US, where parents voluntarily plan and organize their own children’s learning (Ladenthin, 2018 ).

Learning from home during the Covid-19 pandemic brought numerous changes, challenges, and stressors to students’ daily lives (Styck et al., 2021 ). The traditional school-based structure of learning, in which teachers are present to guide and support students, disappeared, and students’ daily routines were altered. Students were forced to organize their learning process themselves, which demanded self-regulated learning competences (Fischer et al., 2020 ). In addition, learning from home limited students’ interactions with their teachers, classmates, and friends to exchanges via online platforms (Wyse et al., 2020 ).

The term social distancing has been used frequently in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic. However, its theoretical construct and operationalization are still being discussed and developed. Conventionally, social distancing can be understood as maintaining physical distance from other people (Abel & McQueen, 2020 ; Aminnejad & Alikhani, 2020 ). For the purpose of the present study, however, social distancing is defined as the subjective, perceived distance to another person or to members of a group (Beck, 2020 ). Current research conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns reports that social distancing can have a negative impact on mental health in the form of conditions such as depression, anxiety, and loneliness (Abel & McQueen, 2020 ; Armbruster & Klotzbücher, 2020; Xie et al., 2020 ). Despite social distancing, however, people can remain in contact using digital devices for chatting, telephoning, and video calling. Moreover, a stronger contact with one’s own family may counterbalance the missing physical closeness to others (Pozas et al., 2021 ; Adami et al., 2020 ; Saad & Gupta, 2020 ). Flack et al. ( 2020 ) highlighted that teachers consider their students to be socially isolated as a result of ERE during the pandemic. Additionally, the authors reported that perceptions among primary school teachers in particular are that the emotional experience of social distancing affects students' academic performance. (López et al., 2017 ). According to Schreiber and Jenny ( 2020 ), emotional experiences can be defined as positive and negative affective activations. A high level of activation is crucial for an affective activation to be considered either positive or negative. Being highly motivated, for example, can be considered a high activation state with a positive affect, whereas being nervous or worried are examples of a high activation state with a negative affect (Schreiber & Jenny, 2020 ). According to Huber and Helm ( 2020b ), a majority of students indicated that they experienced stress due to distance learning; however, most students did not name specific challenges. It is important to mention that Huber and Helm ( 2020b ) took into account only learning challenges and not those with regard to social distancing.

Recent research on both parents’ and students’ experiences during the Covid-19 crisis has shown that social distancing has provided families with both positive and negative experiences. On the one hand, because parents had to work from home, parents and children felt that time spent together as a family was a positive aspect of the shutdown (Pozas et al., 2021 ). Furthermore, studies focusing solely on students’ experiences during the Covid-19 school closures have shown that students found that working on their own and planning their learning according to their own educational needs was beneficial (Holtgrewe et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, major concerns have been raised based on reports of students’ negative experiences (Flack et al., 2020 ). A recent study by Styck et al. ( 2021 ) indicated that not meeting friends in person was the greatest stressor among elementary, middle, and high school students in the United States. This result is in accord with scientific literature pointing out that remote education may evoke feelings of disconnection (Smith & Taveras, 2005 ). Moreover, studies by Xie et al. ( 2020 ) and Zhou et al. ( 2020 ) suggest that students are experiencing significant levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms due to social isolation during the lockdown. A detailed study by Demaray et al. ( 2021 ) indicated that there were gender differences regarding anxiety and depression symptoms associated with stressors due to Covid-19, with an alarmingly high level of depressive symptoms for high school female students. Similarly, Karasmanaki and Tsantopoulos ( 2021 ) and Styck et al. ( 2021 ) reported that female participants experienced more stress in comparison to their male counterparts, especially when it came to fears of social distancing (Fedorenko et al., 2020 ). In sum, it can be assumed that student experiences during social distancing (or isolation) from school are particularly relevant in the current homeschooling context (Brooks et al., 2020 ; Demaray et al., 2021 ; Flack et al., 2020 ; Kira et al., 2020 ; Styck et al., 2021 ; Taylor et al., 2020 ).

Given the far-reaching impact of Covid-19 on many aspects of students’ lives, in particular their social and school experiences, research is of the utmost importance for providing insights into the impact of this health crisis on students’ emotional well-being (Huber & Helm, 2020a ) and for supporting the development of intervention measures (Styck et al., 2021 ). More research should provide a better understanding of the specific characteristics of individuals and contexts that can have potentially negative outcomes on students (Demaray et al., 2021 ). A fair amount of recent research has reported on challenges and stressors, such as lack of resources, family conflict, social distancing, and fear of illness. However, given the importance of a child’s microsystem, such as the school context (Demaray et al., 2021 ), the concrete experiences of children while physically distanced from their school should also be the subject of research. Moreover, research specifically focused on disasters and health crises has shown that it is important to consider gender and age (and educational stage) differences with regard to impacts (Brock et al., 2016 ; Spagnolo et al., 2020 ). Hence, the present study aims to determine if there were significant differences in students’ experiences of social distancing according to gender and educational stage (primary and secondary school) as well as variations in the impact of social distancing on students’ emotional experiences. The following research questions led the data analyses:

- How do students experience social distancing with regard to their school life?

- Are there differences across gender and educational stage with regard to the experiences of social distancing?

- How are students’ experiences of social distancing related to their emotional experiences?

Participants

The data for this study were collected in Germany in a project known as Student-Parents-Teachers in Homeschooling (SCHELLE, following the German term Schüler/-innen-Eltern-Lehrkräfte) (see Letzel et al., 2020 ). The data were collected from an online survey taken from April to June 2020, coinciding with the first lockdown of the Covid 19 pandemic. Students had to provide their parents’ or tutors’ consent before accessing the online survey. The sample consisted of 150 students (62% female) with a mean age of 15.27 years. Grouped according to educational stage, 6.7% of the students were from primary school (grades one to four) and 93.3% from secondary school (grades five to thirteen). To the best of our knowledge, there was currently no existing, evaluated, and validated scale that fit the research questions in this study. Therefore, the authors decided to develop a scale based on previous literature. The student experiences of social distancing scale see (see Table Table1 1 for the German -language version and English translation) was developed based on the work of Beck ( 2020 ) and Bronfenbrenner’s Process-Person-Context-Time model (Tudge et al., 2009 ), from which important components were identified. These include:

- Proximal processes (reciprocal interactions between a developing human being and one or more of the persons, objects, and elements in his or her immediate environment)

- The microsystem (the immediate setting in which the developing human can engage in proximal processes, in this case, the school)

- The macrotime (events in the larger society within and across generations that affect or are affected by processes and outcomes of human development over the life course, in this case the Covid-19 pandemic crisis).

Means, standard deviations, t-statistics, and effect size

After intensive literature study and in cooperation with representatives from science, schools, and educational planning, four items were constructed. It was decided to use a 4-point Likert scale (1= I do not agree at all to 4 = I fully agree) to avoid the potential of a tendency to the middle (Jonkisz et al., 2012 ). The scale was introduced with a short instruction asking students to indicate how they evaluate and perceive their current situation at school given the Covid-19 school closure (“Think about your experiences during the Covid-19 homeschooling situation. Please check the response that most represents your experience”.). The items were developed in German and translated into English for this publication.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was carried out for the four items using principal components analyses with varimax rotation. The Kaiser-Guttman criterion (retain all factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0) was used to identify the number of factors (Osborne & Costello, 2009 ). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was .65, exceeding the recommended value of .06 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007 ), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity reached statistical significance (χ 2 (6) = 180.15, p < .001), indicating that there was sufficient communality in the manifest variables and that the data are suitable for the factor analysis (Field, 2013 ; Pallant, 2010 ). The EFA with the 4 items yielded one single factor accounting for 58.04% of the variance. Table Table1 1 shows the factor loading of the four items on the single factor named as ‘Student Experiences of Social Distancing’. The reliability of the four-item scale was α = .75. The inter-item correlation ranged from .47 to .64. Although the inter-item correlations for two items are relatively moderate, the reliability of the scale did not improve by removing them. Hence, all four items were kept in the scale.

To assess students’ positive and negative activation, the short-form scale for positive activation, negative activation, and valence (PANAVA) scale was used (Schallberger, 2005 ). The PANAVA scale measures students’ positive and negative activation by asking the participants to indicate their emotional state on a 7-point scale consisting of eight items of opposite adjective pairs, with four items representing the positive activations and four the negative activations (Schreiber & Jenny, 2020 ). Positive activation is represented by the adjective pairs “no energy–full of energy”, “tired–wide awake”, “listless–highly motivated”, and “bored–enthusiastic”, with the first adjective expressing a state of low positive activation and the second a state of high positive activation. The items illustrating negative activation are: “relaxed–stressed”, “peaceful–angry”, “calm–nervous”, and “free of worry–worried”. In each case, the first adjective indicates an emotional state of low negative activation and the second an emotional state of high negative activation (Schallberger, 2005 ). Previous research gives evidence that the PANAVA scales possess acceptable internal consistencies. (For the positive activation scale, the value of Cronbach’s alpha is α = .86, and for the negative activation scale, α = .86). For the sample of this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the positive activation was α = .81, and for the negative activation scale α = .78. The students’ reports on their positive and negative activation before distance learning occurred in retrospectively, since the data collection took place during distance learning.

Data analysis

The analyses within this study were conducted using SPSS 27. In order to get detailed insights into research question 1 (the students’ experiences of social distancing) one-sample t-tests were calculated separately for the social distancing scale’s four items. Concerning research question 2, gender differences were analyzed using an independent sample t-test in which, given the imbalance in sample size between primary and secondary students, education -stage differences were explored through a Mann-Whitney nonparametric test (Field, 2013 ). Finally, in order to examine research question 3, two multiple linear regression analyses were performed and students’ emotional experiences of positive and negative activation were calculated.

One sample t test on each item (based on a scale of 1 to 4 where the theoretical mean is 2.5) was calculated. From Table Table1 1 it can be seen that items 1 and 2 were rated higher by the sample, whereas items 3 and 4 were not statistically significant. The effect size of item 1 is large, while that of item 2 is medium, according to Cohen’s d results, where an effect size of 0.20 is small, 0.50 is medium, and 0.8 or above is large (Cohen, 1988 ). Item 2, “I miss my classmates”, had the highest effect size (d = .90), followed by item 1, “I miss my friends” (d = .73).

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of all variables under study can be found in Table Table2. 2 . A one -sample t test was conducted to explore at a scale-level students’ general social distancing experience. Given that the empirical answer score is above the theoretical mean value of the scale (M = 2.5) (t(146) = 8.82, p < .001), the findings indicate that students perceive a high level of distance and separation from their peers, teachers, school, and friends. The results of an independent t-test show that female and male students have a similar perception of social distance (t(144) = − .38, n.s.). Given that more than 90% of the respondents were in secondary school, it was decided to explore potential differences between primary and secondary school students using the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test (Field, 2013 ). The results show that primary school students perceive a higher degree of social distance (Mdn = 3.00) than secondary school students (Mdn = 2.00), U = 231, z = − 2.95, r = − .25.

Factor loadings and inter-item correlation of the items on the students’ experiences of social distancing scale (N = 150 )

The first multiple regression model was conducted to see if age, gender, educational stage, and social distancing level predicted students’ positive activation during the Covid-19 related homeschooling. As seen from Table Table3, 3 , the analyses revealed that both students’ age and social distancing negatively predict their positive activation. It appears that the younger the students are and the less social distancing they experience, the higher their positive activation.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of all variables

*p < .05; **p < .01

The second multiple regression model was calculated to explore whether age, gender, educational stage, and social distancing level predicted students’ negative activation during the Covid-19 related homeschooling. The results show again that students’ age and the experienced social distancing predicted their negative activation. However, as seen from Table Table3, 3 , this is opposite to the previous model, meaning that the older the students are and the higher the levels of social distancing they experience, the more negative activation occurred.

The results of this study give a first impression of how students experienced social distancing from their school, teachers, and classmates as well as the impact it had on their emotional experiences. With regard to the item-level analyses, students rated significantly higher those items related to missing their friends and classmates. This result goes in line with findings from Styck et al. ( 2021 ) in the United States and Heidrich et al. ( 2022 ) in Austria, where students also reported not seeing their friends and classmates as the highest stressor during the Covid-19 school shutdown. However, it is important to highlight that in the present study the item ‘I miss my classmates’ had the largest effect size. Thus, these results strengthen the argument that the school context is a crucial microsystem for children and youth, particularly during the current Covid-19 crisis (Demaray et al., 2021 ).

Furthermore, the findings from this study reported no significant differences across students’ gender. Hence, both female and male participants missed school and their peers in a similar way. This result is similar to the findings of Heidrich et al. ( 2022 ) with an Austrian student sample but contradicts findings from studies such as the one from Fedorenko et al. ( 2020 ) that clearly indicated gender differences. For instance, Fedorenko et al. ( 2020 ) found that female participants reported higher levels of fear of social distancing. However, the discrepancy between the studies may stem from the country and surveyed sample context (United States vs. Germany) and the different research focus. Further research is needed to explore in detail these contrasting results in order to determine whether country -specific or other variables come into play (Table (Table4 4 ).

Multiple regression models

+ p <.10; * p < .05; ** p < .01

Consistent with the findings of Heidrich et al. ( 2022 ), the data analyses indicated that younger students (those in primary school) experienced high levels of social distancing. Previous research has also raised concerns about the potential negative impact of social distancing on the well-being of primary school students (Flack et al., 2020 ). The present study seems consistent with such conclusions, since primary school students clearly rated a higher level of distance, loneliness, and disconnection from their peers, teachers, and school context.

Finally, with regard to the results obtained from the multiple linear regression, it can be concluded that social distancing has a critical impact on students’ emotional experiences. A manifold of research has widely discussed the negative impact of social distancing on children and adolescents. For instance, Ellis et al. ( 2020 ) found that students’ stress over social distancing during the Covid-19–related closures was strongly associated with increased feelings of loneliness and depression. However, as seen from the correlation analyses and both multiple linear regression models, older students appear to be more negatively affected by social distancing. That is, the older the students are, the lower their positive activation and the higher their negative activation as a result of social distancing. Similar findings reported by Wang et al. ( 2021 ) have revealed that social distancing predicted an increase in adolescents’ stress and decreases in their positive activation.

Limitations and considerations for further research

Underlying this study are several limitations that must be considered. First, given the sample size (N=150), it was not possible to establish two samples in order to carry out confirmatory factor analyses as well as validation procedures (i.e., criterion, construct, and content validity) (Svensson, 2011 ). However, because of the unprecedented situation presented by the pandemic, there were no available, well-established instruments that could be implemented. Second, the number of primary school students is relatively low compared to the number of secondary students. Therefore, the results of this study must be considered with caution. Nonetheless, the decision to compare educational stages was derived from available international research that has pointed out differences between primary and secondary school with regard to the effects of social isolation (Demaray et al., 2021 ; Flack et al., 2020 ; Styk et al., 2020). Third, the study used data collected in Germany; thus, generalizing the results to other countries is problematic as differences across countries can be identified only when research follows a cross-country approach and uses the same instruments. Given the features of the scale we used (it is short, reliable, and easy-to-administer), it has the potential to be used internationally, as well, following other countries’ respective back translations and validation studies. This would provide insights that help us better understand potential contextual differences, as in Fedorenko et al. ( 2020 ). Finally, the data stem from a cross-sectional study; it would be desirable to use the scale in a longitudinal study that would also provide insights into the development of students’ social distancing experiences, as the pandemic is a phenomenon that students around the world may encounter in the future.

Conclusions

Despite its limitations, the present study highlights the severe impact of social distancing on students’ emotional experiences and well-being. Students’ experience a drastic reduction in their social interactions during Covid-19 school-related closures. This reduction appears to challenge their need for relatedness in ways that have contributed to higher levels of negative affect and reduced positive activation. Given that the Covid-19 pandemic is still and will most likely continue to be quite an unpredictable situation, it is of upmost importance for schools and teachers to support students’ social interaction. Lastly, the study’s results only strengthen what Bozkurt and Sharma ( 2020 , p. 106) conclude: “Perhaps, one of the lessons we must draw from this experience is that no amount of technology is able to replace face-to-face interaction or the care and emotion present in a classroom”.

Biographies

is a Postdoc at the University of Trier, Department for Teacher Education and Research. Her research interests are inclusion, inclusive practices, diversity, differentiation, differentiated instruction, digitalization in education, virtual reality in education and educational quality. Before changing her profession to research, she worked as a teacher in different school tracks in Germany.

holds a professorship with focus on inclusion and participation within the school context in the Professional School of Education, Humboldt University. Her main research interests are inclusion, differentiated instruction, motivation and interest, as well as digital learning.

is professor of Educational Sciences at the University of Trier, where he is responsible for assessment education in teacher education. His research includes the development of student teachers’ assessment competence, differentiated instruction in secondary education, and factors influencing the academic self-concept in diverse classrooms.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Verena Letzel-Alt, Email: ed.reirt-inu@leztel .

Marcela Pozas, Email: [email protected] .

Christoph Schneider, Email: ed.reirt-inu@credienhcs .

- Abel, T., & McQueen, D. (2020). The Covid-19 pandemic calls for spatial distancing and social closeness: Not for social distancing!. International Journal of Public Health, 65 (3), 231–231. 10.1007/s00038-020-01366-7 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Adami, E., Al Zidjaly, N., Canale, G., Djonov, E., Ghiasian, M. S., Gualberto, C., & Zhang, Y. (2020). PanMeMic manifesto: Making meaning in the Covid-19 pandemic and the future of social interaction. Working Papers in Urban Language and Literacies no 273, 273

- Aminnejad, R., & Alikhani, R. (2020). Physical distancing or social distancing: that is the question. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d'anesthésie, 67 (10), 1457–1458. 10.1007/s12630-020-01697-2 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Beck V. "You can say you to me"—Subjektivität von sozialkörperlicher Distanz in Zeiten der Corona-Pandemie [Social and physical distance subjective perspectives in times of the Corona pandemic] In: Beiring R, editor. Die Psyche in Zeiten der Corona-Krise: Herausforderungen und Lösungsansätze für Psychotherapeuten und soziale Helfer. Klett-Cotta; 2020. pp. 151–162. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bozkurt A, Sharma RC. Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to Coronavirus pandemic. Asian Journal of Distance Education. 2020; 15 :1–6. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brock, S. E., Nickerson, A. B., Reeves, M. A., Conolly, C. N., Jimerson, S. R., Pesce, R. C. & Lazzaro, B. R. (2016). School crisis prevention and intervention: The PREPaRE model (2nd ed.). National Association of School Psychologists.

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020; 395 (10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Demaray, M. K., Ogg, J. A., Malecki, C. K., & Styck, K. M. (2021). Covid-19 stress and coping and associations with internalizing problems in 4th through 12th grade students. School Psychology Review , 1–20.

- Education International (2020). Guiding principles on the Covid-19 pandemic . https://www.ei-ie.org/en/item/23276:guiding-principles-on-the-covid-19-pandemic .

- Ellis BJ, Del Giudice M, Dishion TJ, Figueredo AJ, Gray P, Griskevicius V, Wilson DS. The evolutionary basis of risky adolescent behavior: Implications for science, policy, and practice. Developmental Psychology. 2020; 48 (3):598–623. doi: 10.1037/a0026220. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fedorenko EJ, Kibbey MM, Contrada RJ, Farris SG. Psychosocial predictors of virus and social distancing fears in undergraduate students living in a US Covid-19 "hotspot". Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2020; 50 (3):217–233. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2020.1866658. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Field, A. P. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics: And sex and drugs and rock 'n' roll (4th ed.). Sage.

- Fischer C, Fischer-Ontrup C, Schuster C. Individuelle Förderung und selbstreguliertes Lernen [Individualization and self-regulated learning] In: Fickermann D, Edelstein B, editors. Langsam vermisse ich die Schule …. Waxmann Verlag GmbH; 2020. pp. 136–152. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flack, C. B., Walker, L., Bickerstaff, A., Earle, H., & Margetts, C. (2020). Educator perspectives on the impact of Covid-19 on teaching and learning in Australia and New Zealand. Pivot Professional Learning .

- Greenhow C, Chapman A. Social distancing meets social media: Digital tools for connecting students, teachers, and citizens in an emergency. Information and Learning Sciences. 2020; 121 (5/6):341–352. doi: 10.1108/ILS-04-2020-0134. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Heidrich F, Pozas M, Letzel-Alt V, Lindner KT, Schneider C, Schwab S. Austrian students’ perceptions of social distancing and their emotional experiences during distance learning due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Education. 2022 doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.862306. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Holtgrewe, U., Lindorfer, M., Siller, C., & Vana, I. (2020). Von Risikogruppen zu Gestaltungschanchen: Lernen im Ausnahmezustand [From risk groups to chances: Learning in critical times]. https://www.zsi.at/object/publication/5699/attach/LiA-Momentum20-final[1_.pdf.

- Huber SG, Helm C. Covid-19 and schooling: Evaluation, assessment and accountability in times of crises—reacting quickly to explore key issues for policy, practice and research with the school barometer. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability. 2020; 32 :237–270. doi: 10.1007/s11092-020-09322-y. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huber, S. G., & Helm, C. (2020b). Lernen in Zeiten der Corona-Pandemie. Die Rolle familiärer Merkmale für das Lernen von Schülerinnen: Befunde vom Schul-Barometer in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz [Learning in times of the Corona pandemic: The role of family characteristics for students‘ learning: Results from the School Barometer in Germany, Austria and Switzerland]. In D. Fickermann & B. Edelstein (Eds.), Langsam vermisse ich die Schule…. Schule während und nach der Corona-Pandemie (pp. 37–60). Waxmann.

- Jonkisz E, Moosbrugger H, Brandt H. Planung und Entwicklung von psychologischen Tests und Fragebogen [Planning and development of psychological tests and questionnaires] In: Moosbrugger K, Kelava A, editors. Testtheorie und Fragebogenkonstruktion. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 27–72. [ Google Scholar ]

- Karasmanaki, E., & Tsantopoulos, G. (2021). Impacts of social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic on the daily life of forestry students. Children and youth services review, 120 , 105781. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105781 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Kira IA, Shuwiekh HAM, Rice KG, Ashby JS, Elwakeel SA, Sous MSF, Jamil HJ. Measuring Covid-19 as traumatic stress: Initial psychometrics and validation. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2020; 26 (3):220–237. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2020.1790160. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ladenthin V. Homeschooling. In: Barz H, editor. Handbuch Bildungsreform und Reformpädagogik. Springer; 2018. pp. 519–525. [ Google Scholar ]

- Letzel V, Pozas M, Schneider C. Energetic students, stressed parents, and nervous teachers: A comprehensive exploration of inclusive homeschooling during the Covid-19 crisis. Open Education Studies. 2020; 2 :159–170. doi: 10.1515/edu-2020-0122. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- López, V., Oyanedel, J. C., Bilbao, M., Torres, J., Oyarzún, D., Morales, M., Ascorra, P., & Carrasco, C. (2017). School achievement and performance in chilean high schools: The mediating role of subjective wellbeing in school-related evaluations. Frontiers in Psychology, 8 , Article 1189. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01189 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Meyer, H. (2020). Didaktische Ansprüche an Homeschooling und Fernunterricht . https://unterrichten.digital/2020/05/07/hilbert-meyer-homeschooling .

- Osborne JW, Costello AB. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pan Pacific Management Review. 2009; 12 (2):131–146. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pallant, J. (2010). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS/Julie Pallant (4th ed.). Open University Press.

- Pozas M, Letzel V, Schneider C. ‘Homeschooling in times of Corona’: Exploring German and Mexican primary school students’ and parents’ chances and challenges during homeschooling. European Journal of Special Needs. 2020 doi: 10.1080/08856257.2021.1874152. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Saad, A. A., & Gupta, P. (2020). Role of social media in teaching and learning process: An overview of lockdown period due to Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Indian Research, 8 (2), 32–38.

- Schallberger, U. (2005). Kurzskalen zur Erfassung der Positiven Aktivierung, Negativen Aktivierung und Valenz in Experience Sampling Studien (PANAVA-KS). Theoretische und methodische Grundlagen, Konstruktvalidität und psychometrische Eigenschaften bei der Beschreibung intra- und interindividueller Unterschiede [Short scales for the assessment of positive activation, negative activation, and valence in experience sampling studies (PANAVA-KS). Theoretical and methodological foundations, construct validity, and psychometric properties in describing intra- and 625 interindividual differences]: Forschungsberichte aus dem Projekt "Qualität des Erlebens in Arbeit und Freizeit", Nr. 6. Fachrichtung Angewandte Pschologie des Psychologischen Instituts der Universität.

- Schreiber, M., & Jenny, G. J. (2020). Development and validation of the ‘lebender emoticon panava’ scale (le-panava) for digitally measuring positive and negative activation, and valence via emoticons. Personality and Individual Differences, 160 , 109923. 10.1016/j.paid.2020.109923

- Smith GG, Taveras M. The missing instructor. Elearn. 2005; 1 :1. doi: 10.1145/1070931.1070933. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spagnolo PA, Manson JE, Joffe H. Sex and gender differences in health: What the Covid-19 pandemic can teach us. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020; 173 (5):385–386. doi: 10.7326/M20-1941. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Styck KM, Malecki CK, Ogg J, Demaray MK. Measuring Covid-19-related stress among 4th through 12th grade students. School Psychology Review. 2021; 50 (4):530–545. doi: 10.1080/2372966X.2020.1857658. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Svensson, E. D. (2011) Validity of scales. In M. Lovric (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science . Springer. 10.1007/978-3-642-04898-2_98.

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics . Pearson.

- Taylor S, Landry CA, Paluszek MM, Fergus TA, McKay D, Asmundson GJG. Development and initial validation of the Covid stress scales. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2020; 72 :102232. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102232. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tudge JRH, Mokrova I, Hatfield BE, Karnik RB. Uses and misuses of Bronfenbrenner's bioecological theory of human development. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2009; 1 (4):198–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2009.00026.x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- UNESCO (2020). Education: From disruption to recovery . https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse .

- Wang MT, Scanlon CL, Hua M, Belmont AM, Zhang AL, Del Toro J. Social distancing and adolescent psychological well-being: The role of practical knowledge and exercise. Academic Pediatrics. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.10.008. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wolff, W., Martarelli, C. S., Schüler, J. & Bieleke, M. (2020). High boredom proneness and low trait self-control impair adherence to social distancing guidelines during the Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 17 (15). [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Wyse AE, Stickney EM, Butz D, Beckler A, Close CN. The potential impact of Covid-19 on student learning and how schools can respond. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 2020; 39 (3):60–64. doi: 10.1111/emip.12357. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Xie X, Xue Q, Zhou Y, Zhu K, Liu Q, Zhang J, Song R. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the Coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei province, China. JAMA Paediatrics. 2020; 174 (9):898–900. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1619. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhou S-J, Wang L-L, Yang R, Yang X-J, Zhang L-G, Guo Z-C, Chen J-X. Sleep problems among Chinese adolescents and young adults during the Coronavirus-2019 pandemic. Sleep Medicine. 2020; 74 :39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.06.001. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Op-Ed: Here’s everything I missed as a COVID-era student. Will any of it ever come back?

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

I don’t know what most of the kids in my grade look like. I’ve never gone to a high school dance. My last “regular” school year began in the fall of 2018; that was seventh grade. This week, I start 10th grade.

I have watched many movies about high school. Not one was about a kid eating by themselves at a desk while another student six feet away also eats alone. And I’ve yet to see a movie about students who are only allowed into school every other day.

On a Friday in March 2020, my French teacher looked up from her computer and said we wouldn’t be coming to school on Monday. My first thought was, I hope this lasts for two weeks instead of just one. I could use a vacation.

Adults told me school would be back in a week, maybe two. Now, 18 months and two unusual school years later, I am looking for the stash of masks I wasn’t supposed to need for sophomore year.

This past school year I was scheduled to attend school in-person every other day between September and April. But there was not a lot of consistency. School sometimes would go virtual for a few days, a teacher would be out, or schedules would change because of positive coronavirus cases or exposures, or updated regulations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, state or school district.

My in-person school days started with me putting on the mask that I would wear until 4 p.m. I got on the bus at 6:46 a.m. Even in a Massachusetts winter, my bus still had to have all the windows open. I was not allowed to sit with anyone, so I listened to Spotify to pass the time.

My first class began with the national anthem and the Pledge of Allegiance over the PA system, and then the speaker would remind me to sanitize and wash my hands.

Classes were quiet. I don’t think anyone knew how to act. There was no chatter before or after class, just silence. We didn’t have lockers and we weren’t allowed to hang out in the hallways. There were school officials stationed around the building to make sure we complied.

More than once I would be looking forward to seeing a friend but would get to school and that person wouldn’t be there. Those who tested positive for the virus, or were close contacts of someone who had, had to either quarantine or show negative tests to come back to school.

If a teacher had to stay home, I had to spend that class period in study hall instead. A few times there were so many teachers out that more study hall space had to be created to accommodate all the students whose classes were missing a teacher.

I went back in person full time in April. A friend and I made a bet about how many coronavirus cases there would be in the first week. I won. I guessed there would be at least 15 cases. We hit that by Wednesday. Fortunately, cases dropped after a few weeks.

That first day with all students back, the number of people in the building doubled, class sizes doubled, and space between desks halved. This followed all COVID-19 protocols, but it was still scary. Going to school meant the possibility of getting seriously ill. The good thing was the eerie silence in the building disappeared. Talking was back.

The COVID-19 pandemic has robbed me of memories. I worked so hard in eighth-grade French class, and it took away my spring class trip to Quebec. It canceled my eighth-grade graduation trip to Washington. I didn’t get a proper middle school graduation.

Losing the chance to make those memories was awful, but the day-to-day protocols in high school felt worse.

At robotics, I had to space six feet out from my teammates while working on a robot that was 18 inches tall and wide. One person would go to the robot and the others would step away. Jazz band rehearsal took up the entire auditorium — we weren’t allowed to sit next to one another, so we had to spread out to play.

I wasn’t allowed to high-five other teammates at cross-country practice after a long run or challenging workout. At the beginning of softball season, I had to wear a mask underneath my catcher’s helmet.

Hanging out with friends was entering the local cafe two at a time, ordering a muffin, walking to the town commons, and eating while sitting in a circle six feet apart from one another.

I am not anti-mask or anti-vaccine. I know life can go back to when there was no fear of getting sick, no masks and no social distancing. We have vaccines that allow for this.

I’m about to return to school in person every day, hopefully for the entire school year. As of now my school is not mandating vaccines, but my state just required that masks be worn indoors until at least Oct. 1 . For now, the only certainty I have about my sophomore year is that the rules will keep on changing.

Adults tell me that the way my generation is handling the pandemic is inspiring. That’s a wonderful compliment. But I’d rather have my regular life back.

Sidhi Dhanda is about to start her sophomore year at Hopkinton High School in Hopkinton, Mass.

More to Read

Opinion: California’s new rules allow COVID-positive kids in school. Here’s the problem

Jan. 22, 2024

Commentary: I was a NOVID — until I wasn’t

Nov. 1, 2023

Opinion: How my memories of 9/11 are helping me find an ‘after’ to the pandemic

Sept. 11, 2023

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

California school district becomes first in nation to go all electric buses

May 18, 2024

World & Nation

Biden says 1954 high court ruling on school desegregation was about more than education

May 17, 2024

Sonoma State president retires after being placed on leave for supporting anti-Israel boycott

UCLA Academic Senate rejects censure and ‘no confidence’ vote on Chancellor Gene Block

‘I miss school’: How students are coping with remote learning during coronavirus pandemic

“In my opinion, I think that this is very annoying and I think people will agree,” A. Falcon, a fifth-grader at P.S. 290Q in Ridgewood, said about New York City’s public schools shutting down as a result of the coronavirus outbreak.

For Falcon — whose mother requested her son’s full name not be used — and many of the 1.1 million students in NYC’s school system, the largest school system in the country, the city’s decision to close schools was an abrupt, but necessary measure to stop the spread of the pandemic.

“For many people, school is really fun. You get to meet new friends and goof around at recess after learning new things,” Falcon told QNS. “And for teachers, they get to pass down knowledge to their students. Not only is there math and ELA, but also specials like P.E., science, art and music! But then it came along to the U.S.”

The decision to close schools wasn’t an easy or quick one. Mayor Bill de Blasio and Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza received pushback from many parents, educators and fellow elected officials who felt that schools should’ve closed much sooner.

“I was worried about the disease spreading throughout all of the public schools because although the death rate was low, the more people who get it, the more will die,” Jamie A. said. “I was especially worried for those who have family members with compromised health because if the children carried it home it would put those family members at risk.”

Although schools are closed until Monday, April 20, students still have about three months left of classes. De Blasio recently said there’s a good chance schools won’t open again for the rest of the school year.

As a result, a whole new way of learning and teaching had to take place — remote learning . In anticipation of the city announcing schools would close, many schools throughout the city began to prepare by creating packets and homework for students to take home.

The Department of Education (DOE) then gave teachers a week to train for virtual education, where many teachers, some of which never used online tools, got familiar with resources like Google Classroom and Zoom. Remote learning officially kicked off on March 23.

“I feel sad I cannot see my friends,” said Jordan Turkoglu, a first-grader at P.S. 290Q. “I have some school work but it’s not a lot and I feel sad I cannot see my teacher. I’m happy because I saw some of my friends on video yesterday. I do want to play with my friends but now I cannot.”

“It’s not too stressful and you can work at your own pace without the teacher going too fast during the lesson,” she said. “But I had many questions about my work and the teacher can’t answer the questions right away, so that wastes time and the students might end up doing the assignment wrong if they don’t get it either.”

“Yesterday we learned about money in my math class, and it was helpful because there were videos that helped me understand. It was fun to see comments from my friends on the computer,” Malik said. “But I miss school because there are a lot of fun activities like gym, and you get to make a lot of friends. I didn’t do my music class yet on my computer and I hope it will be like class at school where we get to learn about different singers. I miss hearing my music teacher, Miss Schwab, play the piano.”

Carranza said they estimate about 300,000 students don’t have devices. The DOE distributed 25,000 iPads to students who need it the most, and there are companies offering free internet deals — but there’s still a big disparity between students who have the resources they need and those who don’t.

Jacob Altamirano, a fifth-grader at P.S. 290Q, is worried about the services some students in District 75 (P.S. 277Q, which shares the same building) will miss due to the shutdown, such as counseling, physical therapy, Special Education Teacher Support Services (SETTS) and Individualized Education Program (IEPs).

“Our speech and SETTS are very important for us to continue to develop and do well in school. I hope and wish that me and my friends can continue to see our very important teachers, even if it is online, so we can continue to learn and grow,” Altamirano said.

In a press conference on March 23, Carranza said that the DOE is still developing the remote learning model, and all schools have had to develop their own way of dealing with the change. He asked the school community for “flexibility and patience.”

“It’s also great for the school community because it’s bringing families together,” Leon said. “Teachers, staff members and students get to go home with their families and enjoy this time off as well. It’s a positive thing because families get to spend more time together.”

About the Author

Jobs in new york, add your job.

- Mark Halberstam, Esq. Legal Secretary

- parkingticket.com Court Advocate – NYC Parking Violations Bureau

- FuseFX Corp Compositor, Digital Matte Painter

View all jobs…

Things to do in queens.

Post an Event

Little Explorers at the Queens Zoo Queens Zoo

Family Play Date JCC Chabad LIC

Ayuda gratuita en línea con los deberes y mucho más para niños de primaria a secundaria. Queens Public Library

Oratorio Society of Queens “Faure to Broadway” Spring Concert Queensborough Performing Arts Center

Earth Day event- Paint with Ms. Butterfly Queens Public Library Maspeth

MICROSOFT WORD Y MICROSOFT EXCEL EN ESPAÑOL Woodside Library

View All Events…

Latest News

Get Queens in your inbox

Dining & nightlife.

Entertainment

Police & Fire

Related Articles

More from Around New York

Lainey Wilson wins big at the 2024 Academy of Country Music Awards, including the top honor

Study outlines positive impact of 20 years of marriage equality in America

Hear From LGBTQ Voices In A Queer Election Year

Bryant Park Yoga is Back This Summer (and yoga essentials!)

Queens’ job board.

What the Covid-19 Pandemic Revealed About Remote School

The unplanned experiment provided clear lessons on the value—and limitations—of online learning. Are educators listening?

Katherine Reynolds Lewis, Undark Magazine

:focal(512x344:513x345)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/03/d6/03d60640-f6dd-4840-984d-22d3f18f1d73/gettyimages-1282746597.jpg)

The transition to online learning in the United States during the Covid-19 pandemic was, by many accounts, a failure. While there were some bright spots across the country, the transition was messy and uneven — countless teachers had neither the materials nor training they needed to effectively connect with students remotely, while many of those students were bored , isolated, and lacked the resources they needed to learn. The results were abysmal: low test scores, fewer children learning at grade level, increased inequity, and teacher burnout. With the public health crisis on top of deaths and job losses in many families, students experienced increases in depression, anxiety, and suicide risk.

Yet society very well may face new widespread calamities in the near future, from another pandemic to extreme weather, that will require a similarly quick shift to remote school. Success will hinge on big changes, from infrastructure to teacher training, several experts told Undark. “We absolutely need to invest in ways for schools to run continuously, to pick up where they left off. But man, it’s a tall order,” said Heather L. Schwartz, a senior policy researcher at RAND. “It’s not good enough for teachers to simply refer students to disconnected, stand-alone videos on, say, YouTube. Students need lessons that connect directly to what they were learning before school closed.”

More than three years after U.S. schools shifted to remote instruction on an emergency basis, the education sector is still largely unprepared for another long-term interruption of in-person school. The stakes are highest for those who need it most: low-income children and students of color, who are also most likely to be harmed in a future pandemic or live in communities most affected by climate change. But, given the abundance of research on what didn’t work during the pandemic, school leaders may have the opportunity to do things differently next time. Being ready would require strategic planning, rethinking the role of the teacher, and using new technology wisely, experts told Undark. And many problems with remote learning actually trace back not to technology, but to basic instructional quality. Effective remote learning won’t happen if schools aren’t already employing best practices in the physical classroom, such as creating a culture of learning from mistakes, empowering teachers to meet individual student needs, establishing high expectations, and setting clear goals supported by frequent feedback. While it’s ambitious to envision that every school district will create seamless virtual learning platforms — and, for that matter, overcome challenges in education more broadly — the lessons of the pandemic are there to be followed or ignored.

“We haven’t done anywhere near the amount of planning or the development of the instructional infrastructure needed to allow for a smooth transition next time schools need to close for prolonged periods of time,” Schwartz said. “Until we can reach that goal, I don’t have high confidence that the next prolonged school closure will be substantially more successful.”

Before the pandemic, only 3 percent of U.S. school districts offered virtual school, mostly for students with unique circumstances, such as a disability or those intensely pursuing a sport or the performing arts, according to a RAND survey Schwartz co-authored. For the most part, the educational technology companies and developers creating software for these schools promised to give students a personalized experience. But the research on these programs, which focused on virtual charter schools that only existed online, showed poor outcomes . Their students were a year behind in math and nearly a half-year behind in reading, and courses offered less direct time with a teacher each week than regular schools have in a day.

The pandemic sparked growth in stand-alone virtual academies, in addition to the emergency remote learning that districts had to adopt in March 2020. Educators’ interest in online instructional materials exploded, too, according to Schwartz, “and it really put the foot on the gas to ramp them up, expand them, and in theory, improve them.” By June 2021, the number of school districts with a stand-alone virtual school rose to 26 percent. Of the remaining districts, another 23 percent were interested in offering an online school, the report found.

But the sheer magnitude of options for online learning didn’t necessarily mean it worked well, Schwartz said: “It’s the quality part that has to come up in order for this to be a really good, viable alternative to in person instruction.” And individualized, self-directed online learning proved to be a pipe dream — especially for younger children who needed support from a parent or other family member even to get online, much less stay focused.

“The notion that students would have personalized playlists and could curate their own education was proven to be problematic on a couple levels, especially for younger and less affluent students,” said Thomas Toch, director of FutureEd, an education think tank at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. “The social and emotional toll that isolation and those traumas took on students suggest that the social dimension of schooling is hugely important and was greatly undervalued, especially by proponents for an increased role of technology.”

Students also often didn’t have the materials they needed for online school, some lacking computers or internet access at home. Teachers didn’t have the right training for online instruction , which has a unique pedagogy and best practices. As a result, many virtual classrooms attempted to replicate the same lessons over video that would’ve been delivered at school. The results were overwhelmingly bad, research shows. For example, a 2022 study found six consistent themes about how the pandemic affected learning, including a lack of interaction between students and with teachers, and disproportionate harm to low-income students. Numb from isolation and too many hours in front of a screen, students failed to engage in coursework and suffered emotionally .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/05/e1/05e16ea9-bd7f-4fbf-846e-177f05272f72/gettyimages-1229757662.jpg)

After some districts resumed in-person or hybrid instruction in the 2020 fall semester, it became clear that the longer students were remote, the worse their learning delays . For example, national standardized test scores for the 2020-2021 school year showed that passing rates for math declined about 14 percentage points on average, more than three times the drop seen in districts that returned to in-person instruction the earliest, according to a 2021 National Bureau of Economic Research study . Even after most U.S. districts resumed in-person instruction, students who had been online the longest continued to lag behind their peers. The pandemic hit cities hardest and the effects disproportionately harmed low-income children and students of color in urban areas.

“What we did during the pandemic is not the optimal use of online learning in education for the future,” said Ashley Jochim, a researcher at the Center on Reinventing Public Education at Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College. “Online learning is not a full stop substitute for what kids need to thrive and be supported at school.”

Children also largely prefer in-person school. A 2022 Pew Research Center survey suggested that 65 percent of students would rather be in a classroom, 9 percent would opt for online only, and the rest are unsure or prefer a hybrid model. “For most families and kids, full-time online school is actually not the educational solution they want,” Jochim said.

Virtual school felt meaningless to Abner Magdaleno, a 12th grader in Los Angeles. “I couldn’t really connect with it, because I’m more of, like, a social person. And that was stripped away from me when we went online,” recalled Magdaleno. Mackenzie Sheehy, 19, of Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, found there were too many distractions at home to learn. Her grades suffered, and she missed the one-on-one time with teachers. (Sheehy graduated from high school in 2022.)

Many teachers feel the same way. “Nothing replaces physical proximity, whatever the age,” said Ana Silva, a New York City English teacher. She enjoyed experimenting with interactive technology during online school, but is grateful to be back in person. “I like the casual way kids can come to my desk and see me. I like the dynamism — seeing kids in the cafeteria. Those interactions are really positive, and they were entirely missing during the online learning.”

During the 2022-2023 school year, many districts initially planned to continue online courses for snow days and other building closures. But they found that the teacher instruction, student experience, and demands on families were simply too different for in-person versus remote school, said Liz Kolb, an associate professor in the School of Education at the University of Michigan. “Schools are moving away from that because it’s too difficult to quickly transition and blend back and forth among the two without having strong structures in place,” Kolb said. “Most schools don’t have those strong structures.”

In addition, both families and educators grew sick of their screens. “They’re trying to avoid technology a little bit. There’s this fatigue coming out of remote learning and the pandemic,” said Mingyu Feng, a research director at WestEd, a nonprofit research agency. “If the students are on Zoom every day for like, six hours, that seems to be not quite right.”

Despite the bumpy pandemic rollout, online school can serve an important role in the U.S. education system. For one, online learning is a better alternative for some students. Garvey Mortley, 15, of Bethesda, Maryland, and her two sisters all switched to their district’s virtual academy during the pandemic to protect their own health and their grandmother’s. This year, Mortley’s sisters went back to in-person school, but she chose to stay online. “I love the flexibility about it,” she said, noting that some of her classmates prefer it because they have a disability or have demanding schedules. “I love how I can just roll out of bed in the morning, and I can sit down and do school.” Some educators also prefer teaching online, according to reports of virtual schools that were inundated with applications from teachers because they wanted to keep working from home . Silva, the New York high school English teacher, enjoys online tutoring and academic coaching, because it facilitates one-on-one interaction.

And in rural districts and those with low enrollment, some access to online learning ensures students can take courses that could otherwise be inaccessible. “Because of the economies of scale in small rural districts, they needed to tap into online and shared service delivery arrangements in order to provide a full complement of coursework at the high school level,” said Jochim. Innovation in these districts, she added, will accelerate: “We’ll continue to see growth, scalability, and improvement in quality.”

There were also some schools that were largely successful at switching to online at the start of the pandemic, such as Vista Unified School District in California, which pooled and shared innovative ideas for adapting in March 2020; the school quickly put together an online portal so that principals and teachers could share ideas and the district could allot the necessary resources. Digging into examples like this could point the way to the future of online learning, said Chelsea Waite, a senior researcher at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, who was part of a collaborative project studying 70 schools and districts that pivoted successfully to online learning. The project found three factors that made the transition work: a focus on resilience, collaboration, and autonomy for both students and educators; a healthy culture that prioritized relationships; and strong yet flexible systems that were accustomed to adaptation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/60/64/606453dd-d157-45da-a865-5161f95b6f08/gettyimages-1228656332.jpg)