- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 21 July 2017

Treatment outcomes in schizophrenia: qualitative study of the views of family carers

- Joanne Lloyd 1 ,

- Helen Lloyd 2 ,

- Ray Fitzpatrick 3 &

- Michele Peters 3

BMC Psychiatry volume 17 , Article number: 266 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

28k Accesses

13 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

Schizophrenia is a complex, heterogeneous disorder, with highly variable treatment outcomes, and relatively little is known about what is important to patients. The aim of the study was to understand treatment outcomes informal carers perceive to be important to people with schizophrenia.

Qualitative interview study with 34 individuals and 8 couples who care for a person with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed by a thematic framework based approach.

Carers described well-recognised outcomes of importance, alongside more novel outcomes relating to: Safety (of the patient/others); insight (e.g. into non-reality of psychotic phenomena); respite from fear, distress or pain; socially acceptable behaviour; getting out of the house; attainment of life milestones; changes in personality and/or temperament; reduction of vulnerability to stress; and several aspects of physical health.

Conclusions

These findings have the potential to inform the development of patient- or carer- focused outcome measures that take into account the full range of domains that carers feel are important for patients.

Peer Review reports

Improving treatment outcomes and quality of life for people with long-term mental health conditions are key aims of health care policy [ 1 , 2 ]. Schizophrenia is a particularly important target, being associated with poor quality of life [ 3 ] and individual and societal impacts [ 4 , 5 , 6 ], and requiring long-term treatment [ 7 ]. Antipsychotic medications can ameliorate some symptoms and improve quality of life [ 3 , 8 , 9 ], but individual responses vary [ 10 , 11 ], and many discontinue medication due to poor efficacy or debilitating side effects [ 12 , 13 ]. Treatment outcomes are often assessed by clinician ratings, and/or symptom scales [ 14 ], but patients and carers may prioritise different outcomes to clinicians [ 15 , 16 , 17 ], and controlling symptoms is not the only outcome of importance [ 14 ]. The recovery literature draws attention to the importance of recognising a broad array of outcome domains in schizophrenia treatment, highlighting the relevance of improved social and domestic functioning, alongside subjective wellbeing, optimism and empowerment (e.g. [ 18 , 19 ]). Patients and relatives, in particular, refer to subjective wellbeing when defining ‘remission’, in contrast to traditional clinical definitions focused around reduced symptom scores [ 17 ]. People with schizophrenia value outcomes such as achieving life milestones, feeling safe, improved physical activity, employment, a positive sense of self and psychosocial outcomes [ 20 ]. Understanding the full range of treatment outcomes important to people with schizophrenia and their carers is key for ensuring that clinical practice, research and assessment are aligned with patient and carer priorities [ 4 , 21 ].

While people with schizophrenia can give valid and reliable accounts of outcomes [ 22 , 23 , 24 ], symptoms can make it difficult to participate in research [ 25 ], and carers represent a valuable additional resource [ 15 , 21 , 26 ]. Furthermore, carers have the potential to influence treatment decisions [ 26 ], and experience, indirectly, the impact of outcomes. This study sought to explore the treatment outcomes that carers feel are important for people with schizophrenia. It used a framework informed by a thematic review of the existing literature on treatment outcomes of importance to patients and carers, and a consensus conference with professionals, carers and patients, and aimed to identify whether carers report any outcome domains that have not been emphasised in the current literature.

Design of the study

A qualitative study using in-depth semi-structured interviews was conducted with self-identified ‘carers’ of a family member with a diagnosis of schizophrenia made at least 2 years previously. Ethical approval was obtained from NHS East of Scotland Research Ethics Service (EoSRES) REC 1 by proportionate review (Application Number 13/ES/0143). All participants gave written informed consent.

Participants and recruitment

A total of 34 individuals and 8 couples were interviewed (i.e. 50 people in 42 interviews). While qualitative methodology papers tend to avoid prescribing hard guidelines for sample sizes for qualitative studies, 25–30 participants have been deemed an acceptable minimum by Dworkin [ 27 ] and this number is usually sufficient for reaching data saturation. An email circulated by charity ‘Rethink Mental Illness’ was responded to by 102 people who were screened via telephone to confirm that they were the carer of someone with a ≥ 2-year diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Within this self-selecting convenience sample, participants were then recruited purposively to generate a relatively heterogeneous final sample, consisting of 38 females and 12 males, aged from 20s–80s (48% in their 60s, 26% in their 50s, and the remainder in their 20s, 40s, 70s or 80s), and coming from urban (e.g. Greater London) and rural (e.g. Wiltshire) locations. Thirty-seven were the mother of a person with schizophrenia, 10 were the father or stepfather, one the husband, one the wife, and one the sibling. Duration of illness of the patients discussed ranged from 2 to 20+ years, with a modal duration of 11–15 years (42%). The majority ( n = 44) cared for someone with schizophrenia, and six cared for someone with schizoaffective disorder.

Most participants chose to be interviewed at home, but approximately 20% chose to come to the University. At the beginning of the interviews, carers re-confirmed that the patient had received a formal diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder from a GP or psychiatrist, at least two years prior to the interview. Carers were then asked what they felt were important outcomes of treatment for the patient who they cared for: at present; at a time when the patient was particularly ill or unwell; at a time when they were more stable; and at a time when they were doing particularly well. Prompts were designed to encourage participants to discuss both directly-experienced outcomes, and important/desired but unattained outcomes. In addition, a series of prompts relating to key outcomes were compiled based on the conceptual review of the literature and feedback from a consensus conference, but were not in fact utilised in any of the interviews, as participants spontaneously discussed a broad array of outcomes of importance in response to the preliminary, general questions. After the initial 6 interviews, when it became apparent that participants identified multiple outcomes in response to the primary questions, without need for prompts, the researchers agreed that all future interviews in the study would proceed without prompts. Carers were encouraged to expand upon ideas that they themselves raised in relation to outcomes, rather than directed towards any specific topic. It was felt that this strengthened the data, as it reduced the potential for investigator bias. The topic guide, which was reviewed for tone and content prior to use by two carers and one person with schizophrenia, can be found in online Additional file 1 . Interview duration ranged from 40 to 125 min (average, approx. 60 min).

Interviews were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber, and anonymised. Transcripts were analysed in NVivo 8 by JL, using a thematic, framework based approach [ 28 ]. This involved the creation of a preliminary framework based on a literature review and consensus conference. Transcripts were then analysed, with themes being coded into appropriate categories within that framework, wherever appropriate categories existed. Where themes did not fit well into an existing category, novel categories were created. Interviews were continued until no further novel categories emerged, by which point all categories had been spontaneously mentioned by several participants, and saturation was deemed to have been reached. Once all interviews had been coded, the categories were reviewed by the research team, to ensure that they were representative of all the statements coded within them. Where categories were ambiguous, e.g. contained material that could potentially be better conceptualised within different domains, or could be better represented by different titles, they were revised, and the material coded within them was re-coded in order to ensure that it was coded within the most appropriate category. A final framework that encompassed the original and the novel categories was then agreed amongst the researchers. All of the interviews were then re-coded, using the final framework. In this second iteration, the majority of the material was coded into the same categories as during the initial coding. However, this process was important to ensure that any statements that had originally been coded into categories within the preliminary framework, but in retrospect better-reflected a novel category that had been added to the final framework, were coded appropriately. RF and MP independently cross-checked the final categorisation by coding a random selection of 6 transcripts, and no disagreements emerged. Categorized data were summarized and synthesized, and the resultant categories (and associations between them) were interpreted in relation to the categories already identified within the literature and consensus conference. After the final coding, the number of interviews in which each category occurred was calculated.

Outcomes of importance in schizophrenia reported by the carers included symptom related outcomes, quality of life, functional outcomes, personal recovery, physical health and lifestyle, and satisfaction with treatment. Table 1 lists these outcomes, and their sub-categories, and the proportion of interviews in which they occurred (using the conventions: ‘few’ for 2–10% ( n = 1–4), ‘some’ for 12–24% ( n = 5–10), ‘many’ for 25–50% ( n = 11–21), and ‘most’ for >50% ( n = 22–42)). It was not necessary for a participant to overtly state that an outcome had been experienced by the person they care for, in order to code their statement as an endorsement of that domain. While ‘endorsement’ of an outcome domain did, in some cases, take this form, any statement that either explicitly or implicitly indicated that a domain was relevant or important to that carer, was also coded within that domain. For example, where a carer identified that the person they cared for experienced ongoing difficulties with engaging in physical activity, or that they wished the person they cared for could have the energy to engage in physical activity, this was interpreted as the carer indicating that being able to engage in physical activity was an important outcome, and hence it was coded within the ‘physical activity’ category.

The categories in Table 1 were first identified through a literature review and consensus conference and subsequently adapted to include the newly identified and/or expanded categories from the interview data reported here. Standard font indicates categories which were pre-identified from the literature review (and replicated in the current study), and italic font indicates novel/ modified categories which emerged from the current study (which are illustrated by quotations in Tables 3 and 4 , and discussed below). All categories in Table 1 were identified as relevant by at least some of the carers interviewed, and the majority were mentioned in >50% of the interviews.

Symptom-related outcomes (Table 2 )

Safety was mentioned in most interviews, and encompassed safety from dangerous behaviours prompted by psychosis (such as absconding/ putting oneself or others into risky situations); from health risks linked to negative symptoms (e.g. not eating, living in squalor); and from potential for deliberate self-harm related to affective symptoms.

‘It's great for it to be diagnosed, to be put on your medication and you're safe’ [C41]

The importance of reduction of, or relief from fear, distress and emotional (or even physical) pain was raised in most interviews, often closely related to positive symptoms, but at the level of their physical and emotional consequences.

‘He was absolutely intimidated by his environment… he felt frightened and threatened’ [C25]

Insight was also mentioned in most interviews, encompassing both recognition that current/prior psychotic phenomena are not real, and understanding that one has a long-term illness. It was described as a gatekeeper to many other treatment benefits, partly through its impact upon treatment adherence, and was important in helping people deal with residual psychotic phenomena.

‘He can rationalise…although he hears the voices he has a sense of reality.’ [C40]

Side-effects are not described in detail here as they are well reported within existing literature (e.g. [ 29 ]), but they were identified as important in the majority of interviews, and in addition to commonly-reported side effects (e.g. weight gain and fatigue), a few participants mentioned negative impact of medication on imagination and/or creativity, and concerns over toxicity of medication during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Quality of life (Table 2 )

The concept of ‘social acceptability’ was raised in most interviews, i.e. behaving in a socially appropriate way and avoiding bizarre/unconventional behaviour. Many discussed the importance of treatment in helping patients avoid illegal behaviour (sometimes precipitated by symptoms).

‘[When] he's not taking his medication, he occasionally offends people in the street’ [C25]

Functional outcomes (Table 3 )

The domain of ‘life milestones’ was added to encompass many carers’ reports of the importance of reaching key life/developmental milestones, such as attaining qualifications, learning to drive, moving out of the caregiver’s home, or having a family.

‘I think he missed out all his twenties and thirties so maybe catching up in some ways.’ [C03]

Simply ‘getting out’ of the house was mentioned in most interviews, and was consequently added as a sub-category of ‘leisure pursuits’. This encompassed the importance of being well enough to leave the house, which was something many patients needed to achieve before the more ambitious step of engaging in structured leisure activities or even activities of daily living.

‘The worst time that we've had was… when he was so unwell he didn’t go out the house for a year’ [C24]

A novel sub-category of ‘pets’ was added within the ‘role functioning and productivity’ category, because the importance of being able to care for a pet was raised in some interviews.

Personal recovery (Table 3 )

The importance of ‘personality/temperament’ was raised in most interviews, and was often particularly valued by carers themselves. This encompassed emergence of aspects of the patient’s character, such as sense of humour, consideration, and thoughtfulness, and of a generally calmer temperament, more ‘like oneself’.

‘He reverted to his old self. You could reason with him, you could have a laugh with him’ [C46]

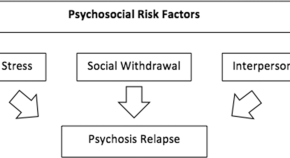

The vast majority of carers also mentioned ‘vulnerability/sensitivity’ to all kinds of stress, in most cases as a residual difficulty that treatment failed to resolve, rather than a positive, attained outcome.

‘Although he seems fairly even I don’t think it would take a huge amount to kick him over the edge.’ [C06]

Physical health and lifestyle (Table 4 )

Exercise/physical activity and diet/weight were raised by the majority of carers, who sometimes described how treatment facilitated physical activity and healthy diet (by improving symptoms that create barriers), but also described how side-effects (such as alteration in appetite/metabolism, and fatigue) could act as barriers.

‘On such a high dose… of a sedating medication. Motivation is just not there’. [C46]

Many described the importance of outcomes related to drugs/alcohol/smoking, such as decreased reliance upon substances previously used to self-medicate positive or affective symptoms, or compensate for lack of social/functional activities.

‘She was drinking herself to sleep, I think, mostly because she had recurrent nightmares, and day time nightmares’ [C50]

Daily routine was mentioned in many interviews, in relation to sleep and waking, eating and self-care, and was described both as a factor that contributed to improving other outcomes, and as an outcome in itself.

Principle findings

All the schizophrenia treatment outcomes identified in the literature review and consensus conference preceding the study (i.e. symptom-related outcomes; functional outcomes; personal recovery; quality of life; and satisfaction with treatment) were confirmed in these qualitative interviews, along with several novel sub-categories within existing domains and a novel category of physical health and lifestyle, thus giving a deeper understanding of outcomes in this condition. While a large proportion of the sample endorsed most of the themes, it should be noted that frequency information are indicative of the frequency of these domains within our sample, and cannot be extrapolated from to estimate the prevalence of these concerns in carers of persons with schizophrenia.

While the importance of physical activity for persons with schizophrenia is recognised within the literature [ 30 ], and low levels of physical activity have been demonstrated empirically to be associated with poorer outcomes in schizophrenia [ 31 ], its importance as a treatment outcome is not expressed in existing outcome measures. This highlights the need to consider physical activity as a potentially relevant outcome domain in its own right. Designing interventions for schizophrenia that include attention to physical health and lifestyle, could help improve outcomes for many patients.

Safety of the patient (and those around them), and reduction of their fear, distress or pain, were considered important by most carers, and it is easy to see why they would value these outcomes, relating to resolution of negative practical and emotional consequences of symptoms. While the importance of these outcomes may be intuitive, they are not explicitly represented in current outcome measures, and this study is novel in highlighting their particular salience. These outcomes could be described as ‘secondary’, in the sense that they could be logically expected to follow on from the more ‘primary’ outcome of amelioration of (particularly, positive) symptoms. However, it could also be argued that there are other means of reducing patients’ fear, distress, or pain, aside from by symptom resolution, and thus outcome measures could benefit from assessing the extent to which treatments help to reduce a patient’s experience of these negative states. This could help professionals to gain a fuller understanding of how a given treatment programme is impacting on the individual’s level of fear and distress.

Most carers also valued insight which they often reported to be associated with improved communication with the person with schizophrenia, and a return of their personality and/or of a more favourable, ‘normal’ temperament. This is consistent with findings that insight in schizophrenia is associated with social cognition [ 32 ], and lower scores on an aggression scale [ 33 ]. Carers also described insight’s importance for enabling patients to apply cognitive strategies to counter paranoid thoughts, delusions or hallucinations, consistent with the finding that insight can be predictive of prognosis [ 34 ]. Monitoring level of insight may be beneficial in order to inform decisions about when cognitive interventions may be more effective. Exploring the value of educating carers in ways to cope with poor insight in the person for whom they care, could be another important target for future work.

Within functional outcomes, many carers talked of ‘getting out’ (i.e. leaving the house), similar to the existing domain of engaging in leisure pursuits, but at a more preliminary level. Caring for pets, similarly, could be conceptualised as a specific form of role functioning/productivity. Where residual difficulties are considerable and/or recovery is particularly limited, less ‘ambitious’ functional outcomes such as these may be particularly relevant. This is consistent with the observation that traditional social functioning measures may not be relevant to people with severe disabilities related to schizophrenia [ 35 ], and with carers’ comments about reduced potential and lowering of expectations. From carers’ references to a range of key developmental/life events such as moving out of the family home, getting a job, learning to drive, and having a romantic relationship, we identified ‘reaching life milestones’ as an important and novel outcome. Because schizophrenia onset is typically during adolescence or early adulthood [ 36 ], before traditional milestones have been reached, it is logical that the reaching of milestones would for many be the goal, rather than the resumption of familial, domestic, occupational or educational roles and responsibilities. This highlights the fact that functional outcome measures in schizophrenia may need to take subtle levels of attainment into account, in order to accurately capture small gains.

Within the realm of ‘personal recovery’ many carers highlighted the importance of changes in personality and temperament, and several described the return of the person they used to know as the most important outcome; understandably so, considering that these are good outward indicators of wellness and ‘personal recovery’ and directly impact upon the patient-carer relationship. Indeed, temperament has been linked with functional outcomes and psychological health [ 37 ]. Also relating to personal recovery, many carers discussed patients’ vulnerability (to stress, and in general) and sensitivity, consistent with empirical findings of increased biological reactivity to stress in schizophrenia [ 38 ]. These were typically described as residual unresolved difficulties, and several carers reported that they limited patients’ attainment of functional outcomes and acted as precipitants of relapse, requiring careful monitoring. This could indicate a potential benefit to be found in involving carers, where appropriate, in helping patients to monitor level of stress, and react quickly to try and reduce its impact.

In the sub-category of ‘leading a normal life’, a number of carers spoke of the importance of treatment for helping patients to avoid socially unacceptable/antisocial/illegal behaviours, (often precipitated by positive symptoms), in order to reduce risk of arrest or sectioning, facilitate social interactions and minimise stigma – consistent with findings that socially unacceptable behaviour is strongly associated with stigma in schizophrenia [ 39 ].

Consistent with other studies, many carers expressed desire for greater monitoring of physical health [ 40 ]. Exercise/physical activity, diet, and weight were all salient concerns; again consistent with findings of elevated obesity [ 41 ] and low activity [ 42 ] in schizophrenia/severe mental illness. A wide range of contributing factors were cited by the carers, including medication side effects, positive, negative and affective symptoms, and eating replacing less attainable leisure pursuits. Several also described patients who used alcohol or drugs to self-medicate and/or compensate for a lack of alternative leisure outlets; consistent with reported motivations for substance use in schizophrenia [ 43 ]. Some carers did describe physical health benefits of treatment, e.g. where it reduced use of drugs or alcohol for self-medication, or reduced symptoms enough to allow patients to exercise or shop for healthy food. In relation to lifestyle more generally, several carers emphasised the importance of routine, as a desirable outcome and useful intervention for facilitating the attainment of other outcomes (consistent with a study where people with schizophrenia rated organization of time as a useful coping strategy [ 44 ]). The discovery that physical health is an important concern in schizophrenia is not novel, but this study does support the growing body of work emphasising the importance of incorporating physical health interventions into schizophrenia treatment programmes (e.g. [ 45 ]).

Strengths and limitations

This study confirms the key treatment outcome categories found in the current literature, and contributes evidence of additional outcomes that carers feel are important for patients but are not apparently captured in current thinking about, and measurement of, schizophrenia outcomes. However, there are some possible biases in the sample. The majority of carers interviewed were parents of a person with schizophrenia, with a gender bias in the sample, such that around three quarters of participants were female. However, this is in line with the gender balance found in other convenience samples of carers of persons with schizophrenia [ 46 ], and reflects the fact that mothers are most frequently the primary carer in schizophrenia [ 47 ]. It is possible that spouses, siblings, or children (or those of a younger age in general) may have different perceptions of what the important outcomes are. Most participants were recruited via Rethink Mental Illness, which may have meant they were particularly well-informed about features of schizophrenia and issues around treatment. Finally, the patients discussed were typically quite advanced in chronicity (in most cases >10 years post-diagnosis). While carers were asked to discuss outcomes that they felt were important at different phases of illness, it is nevertheless possible that carers of patients more immediately post-diagnosis would report different outcomes. Future studies could benefit from exploring outcomes with younger carers with different relationships to the patient, from a range of backgrounds, and those caring for people more early post-diagnosis.

The outcomes carers identified as being important for patients may not be identical to the outcomes that patients themselves would identify. However, there is generally good agreement between the two [ 21 ], and as agents who potentially influence patients’ treatment decisions [ 16 ], and experience the consequences of the illness [ 48 ], carers’ views are important in their own right. Furthermore, we were able to gain insight into outcomes that might not otherwise have been represented, as most of the carers interviewed reported that the patients they were speaking about would have been unwilling/unable to participate (e.g. ‘he hates talking about it when he was really ill… he said, “It makes me feel so ill again” [C41]).

The findings from this study contribute to our understanding of the full range of treatment outcomes that carers feel are important to people with schizophrenia, and could contribute to ensuring research, treatment planning and assessment are aligned with the needs and priorities of patients [ 4 ]. The breadth of information gleaned from these interviews with family carers indicates what an important resource this population represents. Furthermore, it is clear that informal carers typically bear a high burden of care in schizophrenia [ 49 ]. Working with carers to gain insights and coordinate interventions, where appropriate, could be a valuable way for professionals to develop person-centred approaches in schizophrenia. Outcomes of treatment should ideally be assessed with measures that both complement existing clinical scales and incorporate patient and carer priorities. The domains and more specific experience emphasised here should inform the further development of such patient- or carer- focused outcome measures in order to ensure more appropriate and complete evaluation of interventions.

Centre for Mental Health, Department of Health, Mind, NHS Confederation Mental Health Network, R.M. Illness. Turning point: No health without mental health. Implementation framework 2012. London: Department of Health; 2012.

Department of Health. NHS Outcomes Framework 2012/13. London: Department of Health; 2012.

Google Scholar

Bobes J, Garcia-Portilla MP, Bascaran MT, Saiz PA, Bousono M. Quality of life in schizophrenic patients. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2007;9(2):215–26.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Schizophrenia Commission. The abandoned illness: a report from the Schizophrenia Commission. London: Rethink Mental Illness; 2012.

Eack SM, Newhill CE. Psychiatric symptoms and quality of life in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(5):1225–37.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Jin H, Mosweu I. The Societal Cost of Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016.

Ascher-Svanum H, Faries DE, Zhu B, Ernst FR, Swartz MS, Swanson JW. Medication adherence and long-term functional outcomes in the treatment of schizophrenia in usual care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(3):453–60.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Leucht S, Tardy M, Komossa K, Heres S, Kissling W, Salanti G, Davis JM. Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9831):2063–71.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Wehmeier PM, Kluge M, Schneider E, Schacht A, Wagner T, Schreiber W. Quality of life and subjective well-being during treatment with antipsychotics in out-patients with schizophrenia. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(3):703–12.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Wehmeier PM, Kluge M, Schacht A, Helsberg K, Schreiber WG, Schimmelmann BG, Lambert M. Patterns of physician and patient rated quality of life during antipsychotic treatment in outpatients with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(8):676–83.

Levine SZ, Rabinowitz J, Faries D, Lawson AH, Ascher-Svanum H. Treatment response trajectories and antipsychotic medications: examination of up to 18 smonths of treatment in the CATIE chronic schizophrenia trial. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1–3):141–6.

Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, Keefe RS, Davis SM, Davis CE, Lebowitz B, Hsiao J, Severe J. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia: primary efficacy and safety outcomes of the clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:S32.

Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, Samara M, Barbui C, Engel RR, Geddes JR, Kissling W, Stapf MP, Lassig B, Salanti G, Davis JM. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;392:951–62.

Article Google Scholar

Mortimer AM. Symptom rating scales and outcome in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191(50):s7–s14.

Shepherd G, Murray A, Muijen M. Perspectives on schizophrenia: a survey of user, family carer and professional views regarding effective care. J Ment Health. 1995;4(4):403–22.

Bridges JFP, Slawik L, Schmeding A, Reimer J, Naber D, Kuhnigk O. A test of concordance between patient and psychiatrist valuations of multiple treatment goals for schizophrenia. Health Expect. 2013;16(2):164–76.

Karow A, Naber D, Lambert M, Moritz S, Initiative E. Remission as perceived by people with schizophrenia, family members and psychiatrists. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(6):426–31.

Warner R. Recovery from schizophrenia and the recovery model. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22(4):374–80.

Karow A, Moritz S, Lambert M, Schottle D, Naber D, Initiative E. Remitted but still impaired? Symptomatic versus functional remission in patients with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(6):401–5.

Lloyd H, Lloyd J, Fitzpatrick R, Peters M. The role of life context and self-defined well-being in the outcomes that matter to people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Health Expect. 2017; 1–12. doi: 10.1111/hex.12548 .

Balaji M, Chatterjee S, Brennan B, Rangaswamy T, Thornicroft G, Patel V. Outcomes that matter: a qualitative study with persons with schizophrenia and their primary caregivers in India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2012;5(3):258–65.

Voruganti L, Heslegrave R, Awad AG, Seeman MV. Quality of life measurement in schizophrenia: reconciling the quest for subjectivity with the question of reliability. Psychol Med. 1998;28(1):165–72.

Reininghaus U, Priebe S. Measuring patient-reported outcomes in psychosis: conceptual and methodological review. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201(4):262–7.

Baumstarck K, Boyer L, Boucekine M, Aghababian V, Parola N, Lancon C, Auquier P. Self-reported quality of life measure is reliable and valid in adult patients suffering from schizophrenia with executive impairment. Schizophr Res. 2013;147:58–67.

Kaminsky A, Roberts LW, Brody JL. Influences upon willingness to participate in schizophrenia research: an analysis of narrative data from 63 people with schizophrenia. Ethics Behav. 2003;13(3):279–302.

Rettenbacher MA, Burns T, Kemmler G, Fleischhacker WW. Schizophrenia: attitudes of patients and professional Carers towards the illness and antipsychotic medication. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2004;37(03):103–9.

Dworkin SL. Sample size policy for qualitative studies using in-depth interviews. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(6):1319–20.

Ritchie J, Spencer L. In: Bryman A, Burgess B, editors. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research, in Analyzing qualitative data. London: Routledge; 1993. p. 173–94.

Fischer EP, Shumway M, Owen RR. Priorities of consumers, providers, and family members in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(6):724–9.

Soundy A, Freeman P, Stubbs B, Probst M, Coffee P, Vancampfort D. The transcending benefits of physical activity for individuals with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. Psychiatry Res. 2014;220(1–2):11–9.

Vancampfort D, Knapen J, Probst M, Scheewe T, Remans S, De Hert M. A systematic review of correlates of physical activity in patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(5):352–62.

Quee PJ, van der Meer L, Bruggeman R, de Haan L, Krabbendam L, Cahn W, Mulder NC, Wiersma D, Aleman A. Insight in psychosis: relationship with neurocognition, social cognition and clinical symptoms depends on phase of illness. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(1):29–37.

Ekinci O, Ekinci A. Association between insight, cognitive insight, positive symptoms and violence in patients with schizophrenia. Nord J Psychiatry. 2013;67(2):116–23.

Saravanan B, Jacob KS, Johnson S, Prince M, Bhugra D, David AS. Outcome of first-episode schizophrenia in India: longitudinal study of effect of insight and psychopathology. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(6):454–9.

Burns T, Patrick D. Social functioning as an outcome measure in schizophrenia studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116(6):403–18.

de Girolamo G, Dagani J, Purcell R, Cocchi A, McGorry PD. Age of onset of mental disorders and use of mental health services: needs, opportunities and obstacles. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2012;21(1):47–57.

Eklund M, Hansson L, Bengtsson-Tops A. The influence of temperament and character on functioning and aspects of psychological health among people with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2004;19(1):34–41.

Mizrahi R, Addington J, Rusjan PM, Suridjan I, Ng A, Boileau I, Pruessner JC, Remington G, Houle S, Wilson AA. Increased stress-induced dopamine release in psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(6):561–7.

Loganathan S, Murthy SR. Experiences of stigma and discrimination endured by people suffering from schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50(1):39–46.

Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, Buchanan RW, Casey DE, Davis JM, Kane JM, Lieberman JA, Schooler NR, Covell N, Stroup S, Weissman EM, Wirshing DA, Hall CS, Pogach L, Pi-Sunyer X, Bigger JT Jr, Friedman A, Kleinberg D, Yevich SJ, Davis B, Shon S. Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(8):1334–49.

Scott D, Happell B. The high prevalence of poor physical health and unhealthy lifestyle behaviours in individuals with severe mental illness. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2011;32(9):589–97.

McNamee L, Mead G, MacGillivray S, Lawrie SM. Schizophrenia, poor physical health and physical activity: evidence-based interventions are required to reduce major health inequalities. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203(3):239–41.

Gregg L, Barrowclough C, Haddock G. Development and validation of a scale for assessing reasons for substance use in schizophrenia: the ReSUS scale. Addict Behav. 2009;34(10):830–7.

Lee PW, Lieh-Mak F, Yu KK, Spinks JA. Coping strategies of schizophrenic patients and their relationship to outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:177–82.

Stubbs B, Firth J, Berry A, Schuch FB, Rosenbaum S, Gaughran F, Veronesse N, Williams J, Craig T, Yung AR, Vancampfort D. How much physical activity do people with schizophrenia engage in? A systematic review, comparative meta-analysis and meta-regression. Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2–3):431–40.

Svettini A, Johnson B, Magro C, Saunders J, Jones K, Silk S, Hargarter L, Schreiner A. Schizophrenia through the carers’ eyes: results of a European cross-sectional survey. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2015;22(7):472–83.

Wancata J, Freidl M, Krautgartner M, Friedrich F, Matschnig T, Unger A, Fruhwald S, Gossler R. Gender aspects of parents’ needs of schizophrenia patients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(12):968–74.

Gutierrez-Maldonado J, Caqueo-Urizar A, Kavanagh DJ. Burden of care and general health in families of patients with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40(11):899–904.

Nordstroem AL, Talbot D, Bernasconi C, Berardo CG, Lalonde J. Burden of illness of people with persistent symptoms of schizophrenia: a multinational cross-sectional study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2017;63(2):139–50.

Mojtabai R, Corey-Lisle PK, Ip EH, Kopeykina I, Haeri S, Cohen LJ, Shumaker S. The patient assessment questionnaire: initial validation of a measure of treatment effectiveness for patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2–3):857–66.

Matza LS, Phillips GA, Revicki DA, Ascher-Svanum H, Malley KG, Palsgrove AC, Faries DE, Stauffer V, Kinon BJ, George Awad A, Keefe RSE, Naber D. Validation of a clinician questionnaire to assess reasons for antipsychotic discontinuation and continuation among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2–3):835–42.

Kitchen H, Rofail D, Heron L, Sacco P. Cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia: a review of the humanistic burden. Adv Ther. 2012;29(2):148–62.

Mueser KT. Should psychosocial treatment for schizophrenia focus on the proximal or distal consequences of the disorder? J Ment Health. 2012;21(6):525–30.

Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT Jr, Marder SR. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(2):214–9.

Kikkert MJ, Schene AH, Koeter MW, Robson D, Born A, Helm H, Nose M, Goss C, Thornicroft G, Gray RJ. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: exploring patients’, carers’ and professionals’ views. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(4):786–94.

Rogers A, Day JC, Williams B, Randall F, Wood P, Healy D, Bentall RP. The meaning and management of neuroleptic medication: a study of patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(9):1313–23.

Weiden P, Rapkin B, Mott T, Zygmunt A, Goldman D, Horvitz-Lennon M, Frances A. Rating of medication influences (ROMI) scale in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20(2):297–310.

Rosenheck R, Stroup S, Keefe RS, McEvoy J, Swartz M, Perkins D, Hsiao J, Shumway M, Lieberman J. Measuring outcome priorities and preferences in people with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:529–36.

McCabe R, Saidi M, Priebe S. Patient-reported outcomes in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191(50):s21–8.

DiBonaventura M, Gabriel S, Dupclay L, Gupta S, Kim E. A patient perspective of the impact of medication side effects on adherence: results of a cross-sectional nationwide survey of patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):20.

Naber D. A self-rating to measure subjective effects of neuroleptic drugs, relationships to objective psychopathology, quality of life, compliance and other clinical variables. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;10(Suppl 3):133–8.

PubMed Google Scholar

Wilkinson G, Hesdon B, Wild D, Cookson R, Farina C, Sharma V, Fitzpatrick R, Jenkinson C. Self-report quality of life measure for people with schizophrenia: The SQLS. British J Psychiatry. 2000;177:42–6.

Gerlinger G, Hauser M, De Hert M, Lacluyse K, Wampers M, Correll CU. Personal stigma in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a systematic review of prevalence rates, correlates, impact and interventions. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):155–64.

Cuffel BJ, Fischer EP, Owen RR, Smith GR. An instrument for measurement of outcomes of Care for Schizophrenia: issues in development and implementation. Eval Health Prof. 1997;20(1):96–108.

Andresen R, Caputi P, Oades L. Stages of recovery instrument: development of a measure of recovery from serious mental illness. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40(11–12):972–80.

Bullock WA, Young SL. The mental health recovery measure (MHRM). In: Bullock, et al., editors. Measuring the promise of recovery: a compendium of recovery and recovery-related instruments, Part II W.A. Cambridge: Evaluation Center@HSRI; 2005.

Giffort D, Schmook A, Woody C, Vollendorf C, Gervain M. The recovery assessment scale, in can we measure recovery? A compendium of recovery and recovery-related instruments, R.O. Ralph, K. Kidder, and D. Phillips, Editors. Cambridge: Human Services Research Institute; 2000. p. 7–8 52–55.

Resnick SG, Fontana A, Lehman AF, Rosenheck RA. An empirical conceptualization of the recovery orientation. Schizophr Res. 2005;75(1):119–28.

Bloom BL, Miller A. The consumer recovery outcomes system (CROS 3.0): assessing clinical status and progress in persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Colorado Springs: CROS, LLC/Colorado Health Networks; 2004.

Gibson S, Brand S, Burt S, Boden Z, Benson O. Understanding treatment non-adherence in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a survey of what service users do and why. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):153.

McCabe R, Bullenkamp J, Hansson L, Lauber C, Martinez-Leal R, Rossler W, Salize HJ, Svensson B, Torres-Gonzalez F, van den Brink R, Wiersma D, Priebe S, The Therapeutic Relationship and Adherence to Antipsychotic Medication in Schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2012;7(4).

Download references

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Rethink Mental Illness in advertising the study, and the input of all the carers who took part.

This work was supported by EUFAMI, the European Federation of Associations of Families with Mental Illness.

Dr. Joanne Lloyd was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Oxford whilst working on drafts of this article. Dr. Helen Lloyd was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South West Peninsula whilst commenting on drafts of this paper. Throughout this project, Prof Ray Fitzpatrick and Dr. Michele Peters were supported by the Department of Health funded Policy Research Unit on Quality and Outcomes of Person Centred Care (QORU), a collaboration between the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the Universities of Kent and Oxford. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Availability of data and materials

Anonymised transcripts are available from the corresponding author.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Psychology, Sport and Exercise, Staffordshire University, Stoke on Trent, UK

Joanne Lloyd

Peninsula Medical School, Plymouth University, Plymouth, Devon, UK

Helen Lloyd

Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Old Road Campus, Oxford, OX3 7LF, UK

Ray Fitzpatrick & Michele Peters

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MP and RF conceived the study and raised the funding. JL and HL conducted the interviews and led the data analysis. MP and RF contributed to the analysis. All authors were involved in writing the publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Michele Peters .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval was obtained from NHS East of Scotland Research Ethics Service (EoSRES) REC 1 by proportionate review (Application Number 13/ES/0143). All participants gave written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Participants have given consent that anonymised quotes can be used in publications.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

Lloyd et al., Treatment outcomes in schizophrenia: qualitative study of the views of family carers. Interview schedule. (DOCX 12 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lloyd, J., Lloyd, H., Fitzpatrick, R. et al. Treatment outcomes in schizophrenia: qualitative study of the views of family carers. BMC Psychiatry 17 , 266 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1418-8

Download citation

Received : 16 December 2016

Accepted : 04 July 2017

Published : 21 July 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1418-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Schizophrenia

BMC Psychiatry

ISSN: 1471-244X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Original article

- Open access

- Published: 12 August 2022

Positive symptoms of schizophrenia and their relationship with cognitive and emotional executive functions

- Pamela Ruiz-Castañeda 1 , 2 ,

- Encarnación Santiago Molina 3 ,

- Haney Aguirre Loaiza 4 &

- María Teresa Daza González ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6561-8982 1 , 2

Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications volume 7 , Article number: 78 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

8 Citations

Metrics details

Positive symptoms of schizophrenia are associated with significant difficulties in daily functioning, and these difficulties have been associated with impaired executive functions (EEFF). However, specific cognitive and socio-emotional executive deficits have not been fully established.

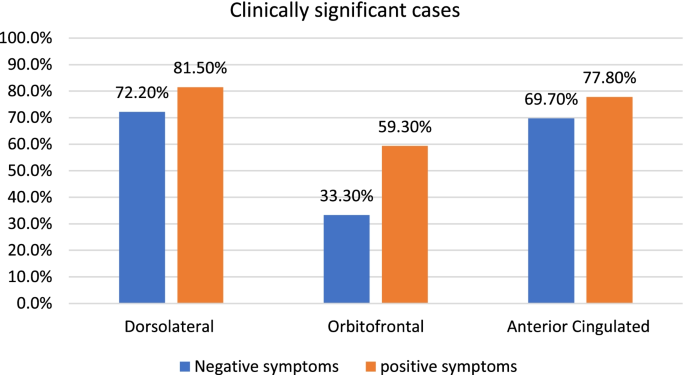

The present study has several objectives. First, we aimed to examine the specific deficits in cognitive and socio-emotional EEFF in a group of patients with schizophrenia with a predominance of positive symptoms, as well as to determine if these patients present clinically significant scores in any of the three fronto-subcortical behavioral syndromes: Dorsolateral, Orbitofrontal, or Anterior Cingulate.

The sample consisted of 54 patients, 27 with a predominance of positive symptoms, and 27 healthy controls matched for gender, age, and education. The two groups completed four cognitive and three socio-emotional EEFF tasks. In the group of patients, positive symptoms were evaluated using the scale for the Evaluation of Positive Symptoms (SANS), while the behavioral alterations associated with the three fronto-subcortical syndromes were evaluated using the Frontal System Behavior Scale (FrSBe).

The patients, in comparison with a control group, presented specific deficits in cognitive and socio-emotional EEFF. In addition, a high percentage of patients presented clinically significant scores on the three fronto-subcortical syndromes.

The affectation that these patients present, in terms of both cognitive and emotional components, highlights the importance of developing a neuropsychological EEFF intervention that promotes the recovery of the affected cognitive capacities and improves the social and emotional functioning of the affected patients.

Introduction

The study of the positive symptoms (PS) of schizophrenia (such as prominent delusions, hallucinations, formal thought disorder, and bizarre behavior) is of particular interest both because of the severity of these symptoms and their consequences for the daily functioning of the patient and their impact on their caregivers. This psychotic clinic is usually associated with more significant social stigma and a higher rate of relapses and hospitalizations (Green, 1996 ; Holmén et al., 2012 ).

From a neuropsychological point of view, current research has realized that the study of neurocognition has important implications for understanding the prognosis, treatment, and neural systems of schizophrenia (Green et al., 2019 ; Molina & Tsuang, 2020 ; Seidman & Mirsky, 2017 ). Various investigations have suggested that the most pronounced neurocognitive deficits in these patients could occur in executive functions (EEFF) (Addington & Addington, 2000 ; Díaz-Caneja et al., 2019 ; Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2013 ; Mingrone et al., 2013 ; Nieuwenstein et al., 2001 ). These functions are directly related to the quality of life and are considered significant predictors of the patient's prognosis (Bobes García & Saiz Ruiz, 2013 ). Several studies have highlighted these deficits as a strong predictor for the development of psychiatric disorders (Ancín et al., 2013 ; Sawada et al., 2017 ). Thus, the study carried out by Bolt et al. ( 2019 ) in patients with “ultra-high risk” of suffering from psychosis found that the EEFF were the only neurocognitive domain that emerged as a significant predictor of the transition to threshold psychosis full. The patients who had more pronounced deficits in this domain were those who developed psychosis in a mean period of 3.4 years. Similarly, Eslami et al. ( 2011 ) found that EEFF deficits at baseline were significant predictors of social functioning and occupational decline within one year. Therefore, these types of results could indicate that FFEE deficits may be a highly sensitive indicator of disease transition risk and poor functional outcomes.

Furthermore, in the scientific literature, a distinction has been established between the more cognitive aspects of EEFF, also called “ cool ” components, and the more socio-emotional, or “ hot ” components (Peterson & Welsh, 2014 ; Prencipe et al., 2011 ; Welsh & Peterson, 2014 ).

Cool EEFF include those cognitive processes manifested in analytical and non-emotional situations, primarily associated with the dorsolateral regions of the prefrontal cortex (Henri-Bhargava et al., 2018; Kamigaki, 2019). Within these EEFF, we would find at least three central components: (1) the processes of coding/maintenance and updating of information in working memory (WM); (2) inhibitory control; and (3) cognitive flexibility (Miyake & Friedman, 2013 ; Miyake et al., 2000 ). In addition, other more complex functions such as planning, abstract reasoning, or problem-solving are developed from these central components. In contrast, hot EEFF include those processes involved in contexts that require emotion, motivation, and tension between immediate gratification and long-term rewards (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012 ; Zelazo & Mller, 2007 ). Are mediated by the ventromedial and orbitofrontal cortices that support behaviors that require emotional regulation, decision-making in situations of uncertainty, recognition of facial expressions and their emotional content, as well as in the ability to infer the perspective of others, also known as mentalization or theory of mind (ToM) (Welsh & Peterson, 2014 ; Zimmerman et al., 2016).

Regarding decision-making in situations of uncertainty, it is a complex process that could be defined as the choice of an option among a set of alternatives, considering the possible results of the choices and their consequences on behavior (Kim & Lee, 2012 ; Xiao et al., 2012). Within this framework, Damasio ( 1994 ) postulates his “Somatic Marker” hypothesis to explain the role of emotions in reasoning and decision-making. In this sense, a Somatic Marker is an automatic emotional response that it is produced by the perception of a certain situation, and which in turn evokes past experiences. Specifically, the neural system for the acquisition of Somatic Marker signals is found in the orbitofrontal and ventromedial portion of the prefrontal cortex. Regarding the theory of the mind, authors such as Zimmerman et al. (2016) describe it as an emotional function that refers to the processes responsible for the perception and identification of emotions, such as empathizing with the affective state of another person. Specifically, the neuroanatomical network associated with ToM includes the medial prefrontal region of the prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, the amygdala, the temporoparietal junction, and the temporal sulcus, bilateral superior–posterior (Amodio & Frith, 2006 ; Ilzarbe et al., 2021 ; Zemánková et al., 2018 ).

Regarding the alterations in cool EEFF presented by patients with a predominance of PS, the results reported to date are inconclusive. On the one hand, studies that have analyzed EEFF through classical paper-and-pencil neuropsychological tests (e.g., Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; Trail Making Test A and B) have reported poor performance in these patients, suggesting general executive impairment (Addington et al., 1991 ; Zakzanis, 1998 ). Moreover, correlations have been reported between PS such as formal thought disorders and persistently bizarre behavior with cool executive components, such as inhibition and cognitive flexibility, pointing to a marked deficit in inhibitory control (Brazo et al., 2002 ; Laplante et al., 1992 ; Li et al., 2017 ; Subramaniam et al., 2008 ). On the other hand, other symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations have been moderately related to difficulties in processing speed, cognitive flexibility, and information updating processes in WM (Ibanez-Casas et al., 2013 ; Laloyaux et al., 2018 ). It has even been proposed that the PS are possible consequences of the deficits in self-monitoring capacity that are shown by these patients (Spironelli & Angrilli, 2015 ).

However, and in contrast to these investigations, other studies suggest conservation of EEFF in these patients (Berenbaum et al., 2008 ; Clark et al., 2010 ) or at least a minimal relationship with PS. Thus, some studies report low or null correlations between symptoms such as delusions or hallucinations and performance on verbal fluency, WM, and attention tasks (Berenbaum et al., 2008 ). Similarly, null correlations have been observed between delusions and hallucinations and performance on tasks that assess resolution problems, working memory, verbal and visual memory, and processing speed, and, using these same tasks, low or moderate correlations with symptoms such as formal thought disorders or bizarre behavior (Ventura et al., 2010 ).

An important question is whether these results could be influenced by the clinical or socio-demographic variables of the sample. In this regard, some studies (Addington et al., 1991 ; Zakzanis, 1998 ) have concluded that performance on EEFF tests is not related to the age of the participants, the number of admissions, the age of disease onset, or type of medication (chlorpromazine equivalents).

The literature on socio-emotional or hot EEFF has also yielded mixed results. Regarding decision-making in situations of uncertainty (participants do not have direct information about the disadvantages of their choices and do not have the opportunity to establish a reasonable strategy at the beginning of the task (Pedersen et al., 2017 )), the studies that have examined the performance of patients with a predominance of PS in the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT) show inconsistent results. Some studies have found negative correlations between symptoms such as hallucinations and prominent delusions and performance on this task compared to controls. In particular, a higher PS score was correlated with a lower Net Score (number of disadvantageous options minus the number of advantageous options), fewer advantageous choices (Struglia et al., 2011 ), and a greater number of disadvantageous choices (Pedersen et al., 2017 ). Other studies, however, using the same paradigm (IGT), did not find differences in performance compared to controls or correlations between IGT performance and symptomatology (Evans et al., 2005 ; Ritter et al., 2004 ; Wilder et al., 1998 ).

Regarding the ability to infer mental states or theory of mind, a generalized deterioration has been reported in these patients, particularly in those with marked PS such as delusions and hallucinations (Corcoran et al., 1995 ). However, in contrast, it has been hypothesized that for the development of certain PS such as persecutory delusions, an intact theory of mind is required, since this is necessary for inferring the intentions of others, even though these inferences are not correct (Peyroux et al., 2019 ; Walston et al., 2000 ).

When analyzing the possible influence of clinical and demographic variables on the results of these studies, although the studies have not considered this as a primary objective, the patients were matched with the control group in terms of age, gender, or education, which has led the authors to suggest that these variables are not the cause of the results and that patients perform the task in a different way to controls (Corcoran et al., 1995 ; Peyroux et al., 2019 ).

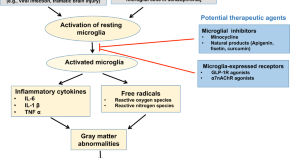

On the other hand, from a neuropsychological point of view, it has been suggested that the heterogeneity and diversity of symptoms shown by patients with schizophrenia could be a consequence of a malfunction of brain circuits of fronto-subcortical origin (Fornito et al., 2012 ; Penadés & Gastó, 2010 ). According to this approach, schizophrenia tends to be considered as a neuronal connectivity disorder and its different symptomatology could be explained by using the distributed neural network model (Goldman-Rakic, 1994 ; Pantelis & Brewer, 1995 ; Wang et al., 2014 ). This model posits that control of any cognitive function is distributed across several interconnected nuclei throughout the brain. The interruption of any of these nuclei or their interconnections would produce changes in cognitive function (Baars & Cage, 2010 ). In this sense, the involvement of these prefrontal areas and/or their connections with other subcortical regions (e.g., the fronto-subcortical circuits of prefrontal origin: Dorsolateral syndrome, related to executive deficits; Orbitofrontal syndrome, related to disinhibition; and syndrome Anterior Cingulate, related to apathetic behaviors (Bonelli & Cummings, 2007 ; Tekin & Cummings, 2002 )), could result in specific deficits in the different cool and hot components of the EEFF (Slachevsky Ch. et al., 2005 ).

In this sense, and regarding the brain areas involved in the PS of schizophrenia, these are not yet fully established. Some inferences in this regard have been obtained from patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) who have developed clinical symptoms and behaviors like those presented in patients with PS in schizophrenia after the injury. Psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations, persecutory delusions, and thought disorders (loosening of associations, tangentiality, or thought blockage) occur more frequently in patients with TBI than in the general population (Fujii & Ahmed, 2002 ; Sachdev et al., 2001 ).

Similarly, a high percentage of patients with TBI also show significant alterations upon neuropsychological examination, similar to those presented by patients with psychotic symptoms, particularly in executive functions and memory (Berrios, 2013 ). These alterations have been associated with post-traumatic structural lesions located in different brain regions, such as the frontal cortex (dorsolateral and orbitofrontal), and, in those structures that form the so-called fronto-subcortical circuits (Alexander et al., 1986 ; Pettersson-Yeo et al., 2011 ).

Therefore, and in summary of the above, two main conclusions can be drawn. First, a review of the current literature has revealed inconclusive results regarding the level of alteration in cool and hot EEFF presented by schizophrenic patients with a predominance of PS. Moreover, there is no conclusive relationship between specific executive components and PS.

Second, the findings of neuroanatomical studies on the affectation of the fronto-subcortical circuits in TBI patients who develop behaviors and PS similar to those presented by patients with schizophrenia could suggest possible alterations of these circuits in schizophrenic patients. Therefore, it is possible that patients with schizophrenia with a predominance of PS present behaviors associated with the so-called fronto-subcortical syndromes (Dorsolateral Prefrontal Syndrome, related to executive deficits; Orbitofrontal syndrome, related to disinhibition; and Anterior or Mesial Cingulate Syndrome, related to apathic behaviors). However, to our knowledge, there is no previous study that has explored the possible involvement of the fronto-subcortical circuits in patients with positive symptoms from the presence of behaviors associated with fronto-subcortical syndromes.

Thus, the present study had several objectives. First, we aimed to study the specific deficits in cool and hot EEFFEF in a group of patients with schizophrenia with a predominance of PS, in comparison with a control group of healthy participants matched for age, gender, and educational level. Second, we set out to study the influence of the main clinical variables (years of evolution of the disease, clinical treatment device, and pharmacological treatment) on executive task performance shown by these patients. Third, we aimed to explore the possible relationship between the severity of PS (hallucinations, delusions, bizarre behavior, and formal thought disorders) with performance on both cool and hot EEFF tasks. And, finally, we wanted to confirm if these patients present clinically significant scores on any of the three fronto-subcortical behavioral syndromes: Dorsolateral, Orbitofrontal, or Anterior Cingulate. (These were measured through the self-reported version of the Frontal System Behavior Scale—FrSBe.)

Considering the previous literature concerning our first objective, we expect psychotic patients with a predominance of PS to show significantly poorer performance on the EEFFEF tasks in comparison with healthy controls. Moreover, in terms of clinical variables, we expect that the years of disease duration, the clinical treatment device, and the type of pharmacological treatment could affect the performance of patients on EEFF tasks.

Regarding the third objective, we expect that the patients with the highest scores on the scale for the Evaluation of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) also show poorer performance on the EEFFEF tasks. Regarding the fourth objective, we anticipate that these patients with a predominance of PS will present some of the frontal behavioral syndromes.

Materials and methods

Participants.

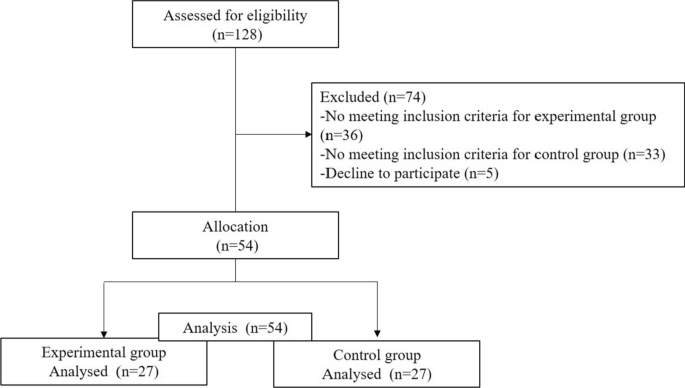

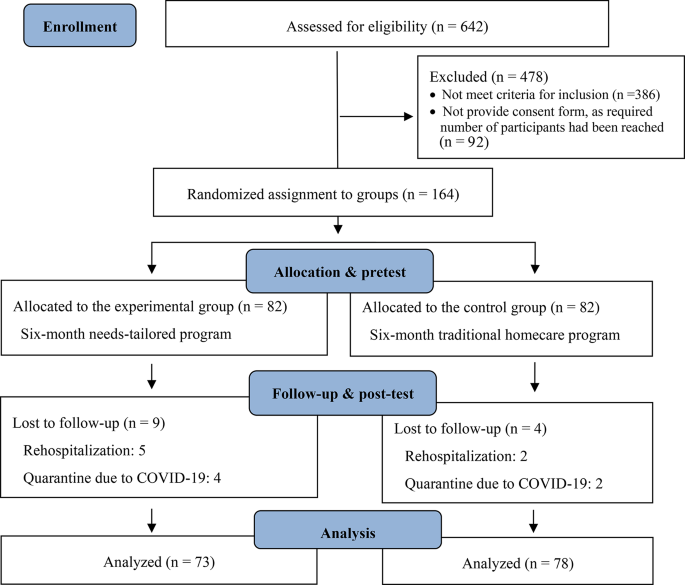

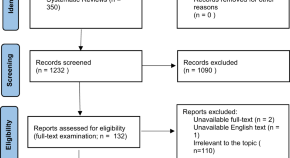

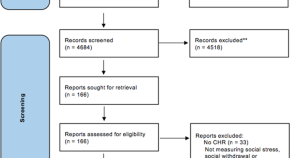

The initial sample consisted of 128 participants (age range: min = 20, max = 61, M age = 37.4, SD = 10.7). The selection process is shown in Fig. 1 . The final sample consisted of n = 54 participants (age range: min = 20, max = 60), of both genders: men ( n = 49, 74.2%, M age = 43.6, SD = 11.0), women ( n = 17, 25.8%, M age = 44.2, SD = 11.0); 27 patients with schizophrenia, and 27 participants assigned to the control group.

Flow of participants throughout the study

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion of the experimental group

Inclusion criteria.

Patients between 18 and 57 years.

Defined diagnosis of schizophrenia

Minimum of two years of evolution of the disease

PS predominance. For this, those patients who showed a higher percentage score in the Evaluation of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) than in the Scale for the Evaluation of Negative Symptoms (SANS) were selected.

Likewise, the psychopathological stability and motivation of the patient were considered, selecting psychopathologically stable patients to carry out the evaluation. The referral psychiatrist established this criterion based on prior knowledge of the patient's clinical status, ensuring sufficient compensation and motivation for participation in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Participants whose main diagnosis is an organic mental disorder, a different medical or psychological illness.

Electroconvulsive treatment in the last 2 years,

Patients with very low motivation for active participation in the study.

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion of the control group

Subjects between 18 and 57 years

Subjects who could be matched with the patients in age, gender, and educational level.

Have no history of mental, neurological, or substance abuse illness,

Not be medicated with any psychotropic medication.

Those participants who did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded.

The patients were selected from the various medical facilities of the Mental Health unit of the reference Hospital Complex of the city. Regarding the socio-demographic variables, three levels were established according to the years of schooling: basic (6 years), medium (between 7 and 12 years), and high (more than 12 years). Regarding the clinical variables, for the duration of the illness, two levels were established according to the sample mean: a group with a shorter duration off illness (less than 11 years) and another group with a longer duration of illness (more than 11 years). Regarding clinical treatment service, two levels were established according to whether they received treatment in an inpatient or outpatient setting. For pharmacological treatment, two levels were established according to whether they took typical or/and atypical medications, and other medications unrelated to mental illness. The control group was matched with the patients in terms of age, gender, and years of schooling. The selected participants had no history of mental, neurological, or substance abuse illness and were not taking any psychotropic medications. The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Centro-Almería belonging to the Torrecárdenas Hospital Complex in the city of Almería (protocol code 52,780. approval date: 26 / 10/2014). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Execution tasks

For the study of cool EEFF, four different neuropsychological tasks were used: 1) the Sternberg-type task, which assesses the processes of encoding/maintaining information in working memory (WM); 2) the 2-back task, which evaluates the monitoring and updating processes of information in WM; 3) the Number–Letter task, which assesses cognitive flexibility or ability to change or alternate the mental set; and 4) a computerized version of the Tower of Hanoi (THO), which evaluates the planning processes involved in the preparation of ordered sequences of actions to achieve specific objectives.

Regarding the hot EEFF, the following three tasks were used: 1) a computerized version of the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT) which assesses decision-making processes in situations of uncertainty; 2) a computerized task for the recognition of facial emotional expressions, and 3) a pencil and paper version of the Hinting task that evaluates the theory of mind (ToM) (See Table 1 ). For a more detailed description of the cool and hot EEFF tasks used in the present study, see Ruiz-Castañeda et al. (Ruiz-Castañeda et al., 2020 ).

Scales for the evaluation of psychotic symptoms and frontal behavioral syndromes

To evaluate positive and negative symptoms, the Scale for the Evaluation of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (Andreasen, 1984 ) and the Scale for the Evaluation of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (Beck & Chaudhari, 1976 ) were used. The behavioral alterations associated with the three frontal syndromes: Dorsolateral Syndrome (executive dysfunction); Orbitofrontal Syndrome (disinhibition); and Anterior or Mesial Cingulate Syndrome (apathy), were evaluated using the Spanish version of the Frontal System Behavior Scale (FrSBe) (Grace & Malloy, 2001 ; Pedrero-Pérez et al., 2009 ) .

For all participants (experimental and controls), the EEFF tasks were administered by two researchers so that one of them always carried out the evaluation, while the second investigator supervised these evaluations. For the patients, the evaluation took place across two individual sessions of approximately 50 min, each with the necessary breaks required by the participant. In the case of the control group, most of them required a single session of approximately 60 min, with the necessary breaks. The evaluation sessions were carried out individually in a quiet room using a laptop.

In the case of patients, the SANS and SAPS scales were administered by the referral physicians (psychiatrists or clinical psychologists). The self-reported version of the FrSBe Scale could be completed by the patient independently (in the researcher's presence) or by the researcher, always trying to ensure the maximum understanding of the questions.

To select psychotic patients with a predominance of PS, the following procedure was applied. Once the patients' referral psychiatrists or clinical psychologists completed the SAPS and SANS scales for each patient, the total scores for each scale were calculated. Each score was then transformed into a percentage. For the SAPS scale, the percentage is calculated based on the maximum score obtained on this scale (170), following the same procedure for the SANS scale (maximum score = 150). Finally, those patients who had a higher percentage on the SAPS scale ( M = 24.0, DT = 16,3) than on the SANS ( M = 15.1, SD = 14.4) were selected.

Statistical analysis

The data were processed through a descriptive and frequency analysis to characterize the socio-demographic and clinical variables. In the exploratory analysis of the data of the response variables, missing data were found, which were imputed to the median value of each group. Outliers were maintained to ensure consistency with the performance of the evaluated. Gender was matched in each group (n = 17 male, n = 10 female). Age was compared with the Mann–Whitney U test, and education level was assessed with X . 2

The direct scores of the neuropsychological tasks were transformed into Z scores. Two multivariate analysis models (MANOVA) were carried out, one with all the measures of the cool EEFF tasks and the other with the measures of the hot EEFF tasks. The first model was EEFF- cool * groups (9 × 2), and the second model was EEFF- hot * groups (6 × 2). Assumptions of normality for hypothesis testing were checked through standardized residuals in both groups. The assumption of equality of covariances was estimated with Box's test, and the multivariate Lambda test of Wilks (Λ) was used. The analysis of multiple comparisons between patients and controls was corrected with Sidak’s procedure. For the comparisons that showed significant differences, the confidence interval (95% CI) of the differences was reported. The effect size was estimated with eta squared ( η p 2 ), using the following values: < 0.01 small, 0.06 moderate, and > 0.14 strong (Cohen, 1988 ).

Pearson's r correlation analyses were conducted between PS and EEFF tasks. To check whether the patients with PS had clinically significant scores in any of the three frontal behavioral syndromes, the direct scores obtained on the FrSBe scale were converted into standardized scores ( T ) according to the age, education, and gender of the participant. With these T scores, three ranges of affectation can be obtained according to their cutoff point: no risk (< 59 points); high risk or borderline (60 to 64); and clinically significant (> 65). The data analyses were conducted using SPSS v.23.0. Post hoc statistical power ( 1-β ) was calculated with G * Power software (Faul et al., 2009 ).

No significant differences were found between patients and controls in age [U( N patients = 33, N controls ) = 542.0, z = − 0.03, p = 0.974], gender [ X 2 (1) = 0.79 , p = 0.778], or years of education [ X 2 (2) = 0.83 , p = 0.959]. The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 2 .

Cool EEFF tasks

The descriptive data of the cool EEFF comparing patients with controls are shown in Table 3 . The MANOVA analysis revealed a significant interaction between the cool EEFF and the groups [ Wilks’ Λ = 0.498, F (9, 44) = 4.93, p < 0.001, ηp 2 = 0.50, 1-β = 0.99 ]. Better performance on the cool EEFF tasks was observed in the control group.

A main effect was found in the two conditions of the information coding/maintenance task in WM (Sternberg-type task) [low load: F (1, 52) = 4.86, p = 0.032, ηp 2 = 0.08, 1-β = 0.58 ; and high load: F (1, 52) = 8.19, p = 0.006, ηp 2 = 0.136, 1-β = 0.8 0]. Likewise, a main effect was found for the task of updating the information in WM (2-Back task) [ F (1, 52) = 16.69, p < 0.001, ηp 2 = 0.243, 1-β = 0.9 8].

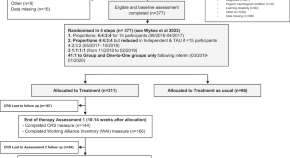

Regarding performance on the task that assesses cognitive flexibility (Number–Letter task), only significant “task-switching costs” (TSC) were observed with reaction time (TSC TR ) [ F (1, 52) = 5.38, p = 0.024, ηp 2 = 0.094, 1-β = 0.6 24]. Regarding the planning task (Tower of Hanoi), only one main effect was observed with the latency measure in the short planning condition [ F (1, 52) = 5.27, p = 0.026, ηp 2 = 0.092, 1-β = 0.6 15] (See Fig. 2 ).

Cool EEFF compared between patients and controls. Note : TSC = Task-switching costs. RT = Response time. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001

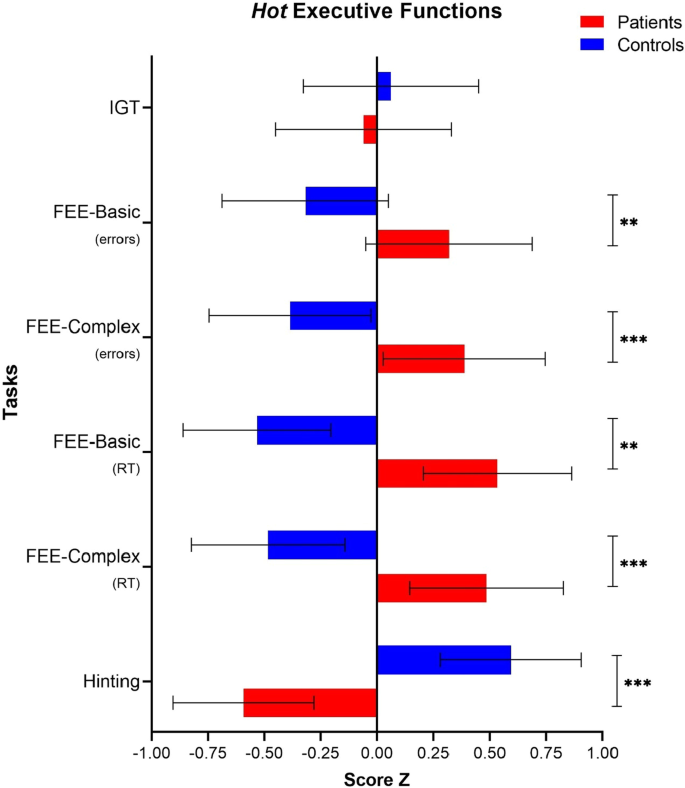

Hot EEFF tasks

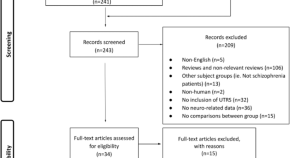

The descriptive data of the hot EEFF comparing patients and controls are shown in Table 4 . The MANOVA analysis revealed a significant interaction between the hot EEFF tasks and the groups [ Wilks’ Λ = 0.475, F (6, 47) = 8.642, p < 0.001, ηp 2 = 0.52, 1-β = 1.0 ]. Better performance on the hot EF tasks was observed in the control group.

Regarding the task that assesses decision-making under conditions of uncertainty (Iowa Gambling Task), the analysis of the Net Score measure (Nº of Advantageous choices—Total Nº of disadvantageous choices) did not show a significant effect [ F (1, 52) = 0.19, p = 0.657, ηp 2 = 0.004, 1-β = 0.07 ].

In contrast, the task that measures the recognition of facial emotional expressions showed significant effects on errors, both in basic facial expressions [ F (1, 52) = 5.993, p = 0.018, ηp 2 = 0.10, 1-β = 0.67 ], as in complex facial expressions [ F (1, 52) = 9.34, p = 0.004, ηp 2 = 0.15, 1-β = 0.85 ]. Similarly, significant effects were also observed in reaction times, both for the condition of basic facial expressions [ F (1, 52) = 21.20, p < 0.001, ηp 2 = 0.29, 1-β = 0.99 ], as complex [ F (1, 52) = 16.34, p < 0.001, ηp 2 = 0.23, 1-β = 0.98 ]. Finally, the performance of the task that assesses the theory of mind (Hinting Task) was significant [ F (1, 52) = 29.06, p < 0.001, ηp 2 = 0.35, 1-β = 1.0 ] (See Fig. 3 ).

Hot EEFF compared between patients and controls. Note : IGT = Iowa Gambling Task. FEE = Facial emotional expressions. RT = Response time. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001

Clinical variables and patient performance in hot and cool EEFF tasks

Regarding the variable years of disease evolution , differences were only observed in the errors of the planning task (Tower of Hanoi) in the condition of precision in short planning [ t (31) = − 2.51, p = 0.034, d = 0.71 95%CI (− 1.86, − 0.08)]; that is, patients with a short disease evolution (less than 11 years) showed better performance [ n = 15; M = − 0.25, SD = 0.62], than the patients with long disease evolution (more than 11 years) [ n = 12; M = 0.71, SD = 1.3]. Based on these results, we wanted to analyze whether the short evolution group showed similar performance to the control group [ n = 27; M = − 0.17, SD = 0.88] and found that these two groups did not differ.

Regarding the clinical device in which the patients received the intervention, no significant differences were found in performance between patients with an outpatient intervention (n = 17) and patients with in-hospital intervention (n = 10).

Regarding pharmacological treatment , no significant differences were found between the group of patients taking typical and/or atypical antipsychotics (n = 23) and those receiving other medication unrelated to mental illness (n = 4). Given these results, we wanted to check whether there were significant differences between those patients who were taking typical medications or a combination of typical and atypical ( n = 4), and those who were only taking atypical medications or other non-psychotropic medications ( n = 23), finding no significant differences between these two groups.

Correlations between positive symptoms and performance on the cool and hot EEFF tasks