Answers & Comments

Robert H. Jackson Center

Mr. justice jackson.

Charles S. Desmond, Paul A. Freund, Justice Potter Stewart & Lord Shawcross, Mr. Justice Jackson: Four Lectures in His Honor (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1969) (with introductions by Whitney North Seymour, John Lord O’Brian, Judge Charles D. Breitel and Justice John M. Harlan).

Publication Year

Collections.

- About Robert H. Jackson

Recently Added

Robert h. jackson center newsletter archive, tea time with the jackson center with audra wilson, tea time with the jackson center: the louisiana bucket brigade, tea time with the jackson center: environmental justice, jackson day: excerpts from “nuremberg”, nuremberg opening statement-75th anniversary reading, visiting guidelines, speech and writing, why learned and augustus hand became great.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

On the Greatest Speech of Jesse Jackson’s Life

David masciotra revisits the 1988 democratic convention.

Jesse Jackson began his address at the 1988 Democratic Convention by introducing the audience to Rosa Parks. Raising her hand in the air, and smiling wide and bright, he christened her the “mother of the Civil Rights Movement.” “Those of us here think we are sitting, but we are standing on the shoulders of giants,” Jackson declared before reciting the names of whites, blacks, Christians, Jews, and atheists who died, from bullets flying into their bodies, knife wounds, and brutal beatings to make American democracy credible, and the rainbow coalition possible, with their work in the civil rights movement.

National political conventions were once the settings of political combat and backroom calculation. In an unpredictable, and often unmoored, display of infighting, approximate in sight and sound to the floor of New York Stock Exchange, party delegates would actually select their presidential and vice presidential nominees at the convention. John Kennedy, for example, fought, lobbied, and brokered deals in order to have his name in the VP slot on the Adlai Stevenson ticket of 1956. He fell short, but did not accept his defeat until mere minutes before the delegate count. Gore Vidal depicted the high energy and intrigue of past conventions with his play about the battle for a presidential nomination, The Best Man .

In the 1970s, due to the healthy shift in emphasis from party elites to primary voters in nomination power, conventions became little more than expensive celebrations of the hosting party. Rather than capturing the intricate machinations of realpolitik, they began to resemble cheerleading exhibitions in which the greatest reward awaited the speaker or presenter who could wave his pom-poms and perform cartwheels with the most enthusiasm. For Jackson to begin his speech, not with a triumphalist tribute to the Democratic Party, but a reminder of the bloodbath and body count that was necessary for America to construct a genuine democracy signaled a different theory and practice of convention oratory.

“My audience was not those on the convention floor” Jackson told me, “It was those watching on television who never got involved in party politics before—the outsiders, the marginalized, the first time voters our campaign brought into things.” Jackson had an hour on primetime television. He was not about to waste it on the bromides of bumper sticker slogans. The address was an electric and emotional hybrid of populist advocacy for a left turn in American politics, but also a fiery homily on the secular rewards of faith, and the human spirit’s capacity to overcome the catastrophes of fate and the cruelties of man. Jackson weaved together political logic and data supportive of his political claims, but when he sang and shouted in sermonic delivery, he relied upon the evidence of his own experience. Transforming the Omni Coliseum of Atlanta, Georgia, into a Pentecostal temple, he gave a testimony.

Democratic nominee Michael Dukakis was reportedly nervous about allowing Jackson to speak at the convention. “When he gets through,” the candidate told a journalist in tones of consternation, “none of us will be able to meet that standard.” Writing in the New York Times , a paper previously unfriendly to Jackson’s presidential campaign, veteran columnist E. J. Dionne claimed that Jackson’s “rousing” performance “did nothing to dim Dukasis’ prediction.”

The prophet, according to popular misinterpretation, is a clairvoyant who might accurately identify tomorrow’s winning lottery numbers, or prevent a child from running across the street because she can envision an inevitable hit and run. Theology and history offers a much richer understanding of the term “prophecy,” and makes clear that it is not synonymous with psychic power. Abraham Joshua Heschel, the rabbi who became a close friend and supporter of Dr. King, explained in his book, The Prophets , that the prophet does not speak for God; he reminds his audience of “God’s voice for the voiceless.” Heschel’s theological interpretation submits that “prophecy is the voice that God has lent to the silent agony, a voice to the plundered poor, to the profane riches of the world.”

Theologian and religious historian, Richard Lischer, writes in The Preacher King: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Word that Moved America that in ancient Israel there were two forms of prophets—central prophets and peripheral prophets. Those on the periphery moved among the poor, gave unsparing and scathing denunciations of power, and never obtained access to the monarchy. Central prophets advised and consulted with kings, struggling valiantly to persuade them to serve the will of the people and keep their covenant with God. King, according to Lischer’s analysis, spent the last years of his life as a peripheral prophet, especially as his message and mission became increasingly radical. When he met with President John Kennedy, and later President Lyndon Johnson, to discuss civil rights legislation, however, he was a central prophet. Jackson never amassed the official influence of King, but with the success of his presidential campaigns, he began to move from the margins to the center.

Heschel writes that he chose to rigorously study the ancient prophets of Judaism when he realized that “the terms, motivations, and concerns that dominate our thinking may prove destructive of the roots of human responsibility and treasonable to the ultimate ground of human solidarity.” Prophecy offers a redemptive alternative. It is the “exegesis of existence from a divine perspective.”

I look at the world from a secular vantage point. Prophecy and speculation over the supernatural means little to me, and I do not believe that a God moves through any speaker, even the most extraordinary. Heschel and Lischer’s theological arguments construct a helpful frame through which to look at certain moments, however, if one can take the questionable liberty of demystifying prophecy. Leaving differing beliefs in the existence of a divinity aside, perhaps one can argue that a prophetic moment is that which enables access to the highest truth of the human condition—the truth of universal human fraternity, the truth of suffering, and the redemptive power of love; the truth that has inspired much of religion, the best of art; the truth to which we aspire in our most magnificent moments. If it is possible to understand prophecy from that perspective, the 1988 Democratic Convention address from Jesse Jackson is the only moment in modern American history when prophecy conquered politics.

Mario Cuomo, the late governor of New York, is famous for his contention that an effective political leader “campaigns in poetry, but governs in prose.” Jackson’s rhetoric at the 1988 convention aspired to reach the heights of poetic grandeur. Its central ambition was to rescue the values of progressive unification around causes of justice from abstraction through their articulation in concrete terminology. He told a heartwarming story of his grandmother, and her tactics borne of privation and desperation, for keeping warm the children in her home:

When I was a child growing up in Greenville, South Carolina my grandmama could not afford a blanket. She didn’t complain, and we did not freeze. Instead she took pieces of old cloth—patches, wool, silk, gabardine, crockersack—only patches, barely good enough to wipe off your shoes with. But they didn’t stay that way very long. With sturdy hands and a strong cord, she sewed them together into a quilt, a thing of beauty and power and culture. Now, Democrats, we must build such a quilt.

Jackson transitioned from his homespun wisdom to the most important political battles of his time, many of them still ongoing, by identifying the isolated issues of social justice as “patches.” When workers fight for fair wages, Jackson thundered, they are right, but their patch alone is insufficient. When mothers petition for child care, equal pay, and paid family leave, they are right, but their patch is still too small. When Black people fight for civil rights, when Latino immigrants work toward an opportunity for citizenship, and when gays argue for equality, they are all righteous in their devotion, but their respective patches are not individually big enough.

“Be as wise as my grandmama,” Jackson advised, “pull the patches and the pieces together, bound by a common thread. When we form a great quilt of unity and common ground, we’ll have the power to bring about health care and housing and jobs and education and hope to our nation.”

Like King making compassionate reference to the financial precarity he shared with his prison guard, Jackson identified common ground with class interest. Few within the Democratic Party spoke with adequate aggression against “Reganomics,” which Jackson defined as a set of policies based on the idea that “the rich have too little money, and the poor have too much.” In his address to the nation, he referred to the extreme income gains of the top 1 percent, along with the data indicating that the wealthiest Americans paid 20 percent less in taxes in the 1980s than they did in the 1970s. The middle class, working class, and poor, meanwhile, were slipping further away from domestic stability on a daily basis. Jackson implored his fellow Democrats that for the party to maintain a laudable and likable identity, it must believe in government as “a tool of democracy” working with the “consent of the governed” to improve living conditions for all Americans, but most especially those who live under the threat of illness, disability, poverty, or bigotry. After most politicians ignored rising inequality for decades, the few voices in the public square who warned of the dangers of austerity, and the destructiveness of policies giving advantage to the rich over everyone else, resound with greater prescience and profundity. The proposals of the Jackson candidacy—radical for their time and place, but pedestrian in Canada and Western Europe—are now those that dominate the platforms of most major Democratic Party leaders.

The speech soared not when Jackson spoke in the prose of politics, but when he offered the poetry of testimony. In his address, he is able to transcend the political and reach toward the prophetic. Not content to merely make a practical case for the poor, he advanced their dignity and asserted their humanity.

They work hard everyday. I know, I live amongst them. They catch the early bus. They work every day. They raise other people’s children. They work everyday. They clean the streets. They work everyday. They drive dangerous cabs. They change the beds you slept in in these hotels last night and can’t get a union contract. They work everyday. No, no, they’re not lazy. Someone must defend them because it’s right and they cannot speak for themselves. They work in hospitals. I know they do. They wipe the bodies of those who are sick with fever and pain. They empty their bedpans. They clean out their commodes. No job is beneath them, and yet when they get sick they cannot lie in the bed they made up every day. America, that is not right.

The United States is the only free and wealthy country that denies its people the most basic of human services. It is alone in the developed world in its cruelty toward the poor, forbidding them access to medicine when they are sick, threatening them with bankruptcy if they desire to take off work to care for a dying parent or spouse, burdening them with decades of debt for pursuing an education, and making their poorest children come of age in conditions of filth and infection.

Abuse, slander, and mistreatment of the poor is not only harmful public policy. It is a violation of the essence of democracy. Walt Whitman, writing in Leaves of Grass , identifies the “password primeval” and “ancient sign” of democracy among the “deformed persons . . . the diseased and despairing . . . the rights of those that others are down upon.” The great American bard prefaces his identification of the democratic voice with the promise, “I will accept nothing which all cannot have their counterpart of on the same terms.” Jackson sings in Whitman verse in his 1988 address; not only advocating for the humanity of the diseased and despairing but also affirming and advancing it in real time. Just as Whitman announced on the opening pages of his epic that every atom belonging to him as good, belongs to you, Jackson articulates something far beyond representation of the dispossessed, but political, social, and spiritual intimacy.

With a simple refrain—“I understand”—Jackson could separate himself from the other mere politicians and establish a familial and experiential kinship with his audience, beginning by broadcasting the criticism of skeptics:

“Jesse Jackson, you don’t understand my situation. You be on television. You don’t understand. I see you with the big people. You don’t understand my situation.” I understand. You see me on TV, but you don’t know the me that makes me, me. They wonder, “Why does Jesse run?” because they see me running for the White House. They don’t see the house I’m running from. I have a story. I wasn’t always on television. Writers were not always outside my door. When I was born late one afternoon, October 8th, in Greenville, South Carolina, no writers asked my mother her name. Nobody chose to write down our address. My mama was not supposed to make it, and I was not supposed to make it. You see, I was born of a teenage mother, who was born of a teenage mother. I understand.

I know abandonment, and people being mean to you, and saying you’re nothing and nobody and can never be anything. I understand.

Jesse Jackson is my third name. I’m adopted. When I had no name, my grandmother gave me her name. My name was Jesse Burns until I was 12. So I wouldn’t have a blank space, she gave me a name to hold me over. I understand when nobody knows your name. I understand when you have no name.

I understand. I wasn’t born in the hospital. Mama didn’t have insurance. I was born in the bed at the house. I really do understand. Born in a three-room house, bathroom in the backyard, slop jar by the bed, no hot and cold running water. I understand.

Wallpaper used for decoration? No. For a windbreaker. I understand. I’m a working person’s person. That’s why I understand you whether you’re black or white. I understand work. I was not born with a silver spoon in my mouth. I had a shovel programmed for my hand. My mother, a working woman. So many of the days she went to work early, with runs in her stockings. She knew better, but she wore runs in her stockings so that my brother and I could have matching socks and not be laughed at at school. I understand.

At 3 o’clock on Thanksgiving Day, we couldn’t eat turkey because momma was preparing somebody else’s turkey at 3 o’clock. We had to play football to entertain ourselves. And then around 6 o’clock she would get off the Alta Vista bus and we would bring up the leftovers and eat our turkey—leftovers, the carcass, the cranberries—around 8 o’clock at night. I really do understand.

“I had a life, an experience, that most of the others (politicians) did not, because American politics had become so caught up in the affairs of the wealthy. So, on a spiritual matter, I was simply trying to say, ‘I understand your pain, your difficulty, your challenges,’” Jackson told me when I asked about his refrain for the crescendo of his speech. “My grandmother almost did not vote for me,” he remembered, “Because she could not read or write. It was hard for her, because she would have to admit her illiteracy. So, I understand. It was simple.” Jackson continued with a practical application of his philosophy that still eludes most Democrats, especially those who in the aftermath of Trump immediately began to focus on the white working class—“Democrats were obsessed with regaining some of the votes of the white men who went to Reagan. I thought it more important to get those we never had, because they never registered, but were our natural allies, than scramble and make compromises for those we lost. That’s how Barack won in 2008. He brought out the rainbow.”

As Jackson reaches his soaring conclusion in the speech, he addresses those whose voices society often places on mute, those who suffer through degradation, and those whose lives, both painful and heroic, are often without advocacy in the nexus of corporate media and major party politics. His voice rising in a full-throated shout, Jackson exercised the politics of friendship, and, in doing so, demands a friendship of politics. In a culture that too often evaluates worth and character according to the narrow and shallow metrics of wealth, glamor, and power, Jackson advanced a deeper alternative of universal beauty and sublimity.

In your wheelchairs. I see you sitting here tonight in those wheelchairs. I’ve stayed with you. I’ve reached out to you across our nation. Don’t you give up. I know it’s tough sometimes. People look down on you. It took you a little more effort to get here tonight. And no one should look down on you, but sometimes mean people do. The only justification we have for looking down on someone is that we’re going to stop and pick them up. But even in your wheelchairs, don’t you give up. We cannot forget 50 years ago when our backs were against the wall, Roosevelt was in a wheelchair. I would rather have Roosevelt in a wheelchair than Reagan on a horse.

As Jackson offers his homiletic helping of encouragement, the camera catches a man on the convention floor, sitting in a wheelchair. His face cracks into a half smile, but his eyes betray sadness. It is not presumptuous to imagine that Jackson’s words about “mean people” cut his heart like a scalpel. As soon as Jackson uttered the words, “look down on you,” the same man raises his thumb in the air. He never allows it to drop. Even as the crowd goes wild with Jackson’s comparison of FDR to Ronald Reagan, he keeps his arm extended, his thumb pointing toward the sky. It is in the coupling of Jackson’s words and that man’s facial expression and approving gesture that a politics of transcendence emerges, and through that emergence one gains an ability to accurately appraise the stakes of an argument. More than taxation, regulation, and even law, political debate can, in its most ambitious moments, raise the most crucial inquiries into what a society values. If we, as a people, would rather affirm the dignity of the man in the wheelchair than tacitly provide aid and encouragement to the mean people who look down on him, we must make a series of decisions, and those decisions must go beyond personal behavior and private charity. They must implicate the very essence of our society—how we organize our institutions, and how we exercise our power.

“Every one of those funny labels they put on you, those of you who are watching this broadcast in the projects, on the corners, I understand,” Jackson announced in a softer, more delicate enunciation. He then continued in the final emphasis of exactly what his campaign meant, and who it was meant for: “Call you outcast, low down, you can’t make it, you’re nothing, you’re from nobody, subclass, underclass; when you see Jesse Jackson, when my name goes in nomination, your name goes in nomination.”

__________________________________

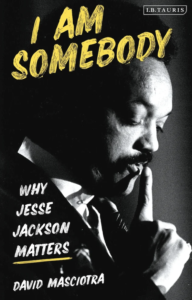

From I Am Somebody: Why Jesse Jackson Matters by David Masciotra. Used with the permission of I. B. Tauris & Company. Copyright © 2021 by David Masciotra.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

David Masciotra

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

What It's Like to Learn to Sing in Your Fifties

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Jackson, Jimmie Lee

December 16, 1938 to February 26, 1965

On the night of 18 February 1965, an Alabama state trooper shot Jimmie Lee Jackson in the stomach as he tried to protect his mother from being beaten at Mack’s Café. Jackson, along with several other African Americans, had taken refuge there from troopers breaking up a night march protesting the arrest of James Orange, a field secretary for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in Marion, Alabama. Jackson died from his wounds eight days later. Speaking at his funeral, Martin Luther King called Jackson “a martyred hero of a holy crusade for freedom and human dignity” (King, 3 March 1965).

Jimmie Lee Jackson was born in Marion, Alabama, on 16 December 1938. At age 26, the former soldier was the youngest deacon in his church, the father of a young daughter, and worked as a laborer.

Throughout late 1963 and 1964, local black activists in Selma and nearby Marion campaigned for their right to vote. By the time King and the SCLC arrived in Selma on 2 January 1965 to support the campaign, Jackson had already attempted to register to vote several times. King chose to bring SCLC to the region because he was aware of the brutality of local law enforcement officials, led by the sheriff of Dallas County, James G. Clark . King thought that unprovoked and overwhelming violence by whites against nonviolent blacks would capture the attention of the nation and pressure Congress and President Lyndon Johnson to pass voting rights legislation.

On the night Jackson was shot, he marched with his sister, mother, 82-year-old grandfather, and other protesters from Zion United Methodist Church, where King’s colleague C. T. Vivian had just spoken, toward the city jail where Orange had been imprisoned earlier that day. When the local police, aided by state troopers, violently broke up the march, demonstrators ran back to the church, nearby houses, and businesses for safety. In the melee, Jackson and his family sought refuge with others in Mack’s Café. Troopers followed the protesters inside and began beating people. After Jackson was shot, troopers chased him outside and continued to beat him until he collapsed. In addition to Jackson, at least half a dozen others were hospitalized for the blows they received from troopers.

King visited Jackson at the Good Samaritan Hospital in Selma four days after he was shot. Jackson was conscious, and King recalled his words during the eulogy he delivered to the overflowing Zion Church: “I never will forget as I stood by his bedside a few days ago … how radiantly he still responded, how he mentioned the freedom movement and how he talked about the faith that he still had in his God. Like every self-respecting Negro, Jimmie Jackson wanted to be free ... We must be concerned not merely about who murdered him but about the system, the way of life, the philosophy which produced the murderer” (King, 3 March 1965). Many were enraged that no case was opened against James Bonard Fowler, the Alabama state trooper who shot Jackson. Fowler acknowledged shooting Jackson at close range in an affidavit given the night of the shooting and told his story publicly in 2005 for an article in Sojourners Magazine . He claimed that Jackson attempted to take his pistol from him, and called the shooting self defense. Marion police chief T. O. Harris claimed that protesters had attacked law enforcement officers with rocks and bottles, but news reporters on the scene saw troopers beating protesters as they tried to escape, and black witnesses said no bottles were ever thrown. Forty years later, in May 2007, Fowler was indicted for Jackson’s murder.

In the weeks following Jackson’s death, SCLC organized a march from Selma to Montgomery , the state capitol. An SCLC brochure explained that Jackson’s death was “the catalyst that produced the march to Montgomery.” On 7 March 1965, the day the march first set off from Selma, Sheriff Jim Clark’s deputies attacked demonstrators with tear gas, batons, and whips. Images of the attack were nationally televised and at least one network interrupted regular programming to broadcast the violence of “Bloody Sunday.” Two white civil rights workers, Viola Liuzzo and Reverend James Reeb , were later killed during the campaign. In August, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed into law.

Branch, Pillar of Fire , 1998.

John Fleming, “Former Trooper Arraigned in 1965 Murder Case,” Anniston Star , 11 July 2007.

John Fleming, “Who Killed Jimmy Lee Jackson?” Sojourners Magazine 34 (April 2005): 20–24.

Garrow, Protest at Selma , 1978.

King, Eulogy for Jimmie Lee Jackson, 3 March 1965, MMFR .

SCLC, Let There Be Understanding of the Call to Boycott in Alabama (Atlanta: SCLC, April 1965), SHLMP-WHi .

- Latest News

- Latest Issue

- Asked and Answered

- Legal Rebels

- Modern Law Library

- Bryan Garner on Words

- Intersection

- On Well-Being

- Mind Your Business

- My Path to Law

- Storytelling

- Supreme Court Report

- Adam Banner

- Erwin Chemerinsky

- Marcel Strigberger

- Nicole Black

- Susan Smith Blakely

- Members Who Inspire

- Celebrating the powerful eloquence of Justice…

Celebrating the powerful eloquence of Justice Robert Jackson

By Bryan A. Garner

October 1, 2016, 2:50 am CDT

Justice Robert Jackson. Photograph by AP Images

This year marks two important anniversaries concerning the great Justice Robert H. Jackson: Seventy-five years ago, in 1941, he took his seat on the U.S. Supreme Court; and 70 years ago he was on sabbatical from the court to serve as chief counsel for the United States in the prosecution of senior Nazi officials at Nuremberg. This month, the Center for American and International Law in Dallas is hosting a symposium—one of many around the country—to assess the significance of those postwar prosecutions. Much of the interest and energy will focus on Jackson himself.

Doubtless because Jackson was so unusually eloquent, a majority of the current justices name him as their favorite writer ever to serve on the court. Let’s see why. We’ll primarily consider two documents: his majority opinion in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette and his opening and closing arguments at Nuremberg. There are countless other examples you might seek out as well.

Barnette was decided in June 1943. The United States was embroiled in World War II. It was a time when worries, fears and patriotism ran high. In this atmosphere, the West Virginia board of ed, emboldened by a 3-year-old opinion of the court ( Minersville School District v. Gobitis ), passed a resolution requiring all children to salute the flag and recite the Pledge of Allegiance. A group of Jehovah’s Witnesses objected that their civil liberties had been infringed, and they sued.

memorable phrasing

The Jackson opinion for the majority is a thing of beauty. It’s rather like Shakespeare’s Hamlet : Almost every line is quotable. In the eight-page opinion, Jackson quotes very little and cites only two cases. The opinion reads like one of the most powerful essays you’ll ever see.

After explaining the petitioners’ basic objection to the flag salute and pledge, Jackson coolly sets forth the consequences: “Failure to conform is ‘insubordination’ dealt with by expulsion. Readmission is denied by statute until compliance. Meanwhile, the expelled child is ‘unlawfully absent’ and may be proceeded against as a delinquent. His parents or guardians are liable to prosecution and if convicted are subject to fine not exceeding $50 and jail term not exceeding 30 days.”

These aren’t idle threats: “Children of this faith have been expelled from school and are threatened with exclusion for no other cause. Officials threaten to send them to reformatories maintained for criminally inclined juveniles. Parents of such children have been prosecuted and are threatened with prosecutions for causing delinquency.”

A preliminary question in the case was whether the pledge is a form of speech protected by the First Amendment. Yes, wrote Jackson: “There is no doubt that, in connection with the pledges, the flag salute is a form of utterance. Symbolism is a primitive but effective way of communicating ideas. The use of an emblem or flag to symbolize some system, idea, institution or personality is a shortcut from mind to mind. ... A person gets from a symbol the meaning he puts into it, and what is one man’s comfort and inspiration is another’s jest and scorn.” The paragraph is refreshingly free from citations to authority. None were needed.

The 1940 Gobitis decision had suggested that the flag-salute controversy confronted the court with “the problem which Lincoln cast in memorable dilemma: ‘Must a government of necessity be too strong for the liberties of its people, or too weak to maintain its own existence?”

Jackson’s answer amounted to a blast: “It may be doubted whether Mr. Lincoln would have thought that the strength of government to maintain itself would be impressively vindicated by our confirming power of the state to expel a handful of children from school. Such oversimplification, so handy in political debate, often lacks the precision necessary to postulates of judicial reasoning. If validly applied to this problem, the utterance cited would resolve every issue of power in favor of those in authority and would require us to override every liberty thought to weaken or delay execution of their policies.” Again, not a single citation of anything—just close analysis of the issues.

You’ll have noticed by now that Jackson used words really well. (Please don’t write to me about the restrictive which es where we’d prefer that s. He had a foible.) His verbs, his nouns and even his adjectives are fresh and bold: “That [boards of education] are educating the young for citizenship is reason for scrupulous protection of constitutional freedoms of the individual, if we are not to strangle the free mind at its source and teach youth to discount important principles of our government as mere platitudes.”

One of his most memorable phrases was a literary allusion deriving from Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” (1751). But you needn’t even know the poem to get the point. The allusion appears in the second sentence here: “The action of Congress in making flag observance voluntary and respecting the conscience of the objector in a matter so vital as raising the Army contrasts sharply with these local regulations in matters relatively trivial to the welfare of the nation. There are village tyrants as well as village Hampdens, but none who acts under color of law is beyond reach of the Constitution.”

In his tight essay, Jackson expresses truths that seem prescient today: “One’s right to life, liberty and property, to free speech, a free press, freedom of worship and assembly, and other fundamental rights may not be submitted to vote; they depend on the outcome of no election.” Or this haunting image (remember it was 1943, and nobody in America knew anything about the horrifying extent of Hitler’s death camps): “Those who begin coercive elimination of dissent soon find themselves exterminating dissenters. Compulsory unification of opinion achieves only the unanimity of the graveyard.”

Enduring insights

Jackson reminded his readers from time to time of his lawyerly credentials. He liked the word therein . But notice how he could be eloquent even with that smidgin of legalese: “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation [note the alliteration], it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein. If there are any circumstances which permit an exception, they do not now occur to us.”

Small wonder that many constitutional scholars consider Barnette their favorite majority opinion of all time.

Justice Felix Frankfurter, by contrast, wrote a long and quotation-filled dissent in which he begins defensively: “One who belongs to the most vilified and persecuted minority in history is not likely to be insensible to the freedoms guaranteed by our Constitution.” He alone wanted to enforce the expulsions from school. It was not his best moment—and, in fairness, we should note that his career was full of excellent moments.

But back to Jackson. When necessary to avert immediate dangers posed by those exhorting violence, he was ready to grant government the power of intervention. In a 1949 case, he dissented from a decision overturning the breach-of-peace conviction of a former priest whose incendiary pro-fascist and anti-Semitic rhetoric had provoked two mobs to clash. Citing the necessity of public order, Jackson warned in his dissent: “If the court does not temper its doctrinaire logic with a little practical wisdom, it will convert the constitutional Bill of Rights into a suicide pact.” Again, his clarion, pithy insights are enduringly relevant.

In 1945–46, when he took leave from the court to prosecute war crimes in Germany, some of his colleagues were unimpressed. Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone thought the Nuremberg trials amounted to a fake show of victors’ justice. He said privately: “Jackson is away conducting his high-grade lynching party in Nuremberg.”

But in his opening statement, Jackson delivered some of the most powerful words ever uttered in any courtroom: “The wrongs which we seek to condemn and punish have been so calculated, so malignant and so devastating that civilization cannot tolerate their being ignored because it cannot survive their being repeated. That four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury, stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgment of the law is one of the most significant tributes that power has ever paid to reason.”

And in his July 1946 closing statement, he said: “If you were to say of these men that they are not guilty, it would be as true to say there has been no war, there are no slain, there has been no crime.”

This article originally appeared in the October 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Powerful Eloquence: Celebrating the words of Justice Robert Jackson.”

Bryan A. Garner, the president of LawProse Inc., is the author most recently of "Garner's Modern English Usage," "The Chicago Guide to Grammar, Usage, and Punctuation" and "Guidelines for Drafting and Editing Legislation."

Related topics:

U.s. supreme court | legal history | legal writing | bryan garner on words, you might also like:.

- New Legalese: You may have heard a deepfake, but what about 'Twiqbal'?

- Can you spot the wrong words in Bryan Garner's quiz?

- Bryan Garner's 2023 legal writing tips

- Blissful Ignorance: Bad writers may be happier than good ones

- Bring some brio to your writing to add clarity, says Bryan Garner

Give us feedback, share a story tip or update, or report an error.

- 2 lawyers and client die in law office shooting; 1 attorney was alleged gunman

- Shake-up in US News' 2024 law school rankings

- 'Venue is not a continental breakfast' judge forced to eat his words after 5th Circuit blocks transfer

- 'Sense of entitlement' led BigLaw partner to 'brazenly' appear at deposition and act 'obnoxious,' sanctions bid says

- David Boies can't ignore clients' liability releases by 'simply invoking' name 'Epstein,' sanctions bid says

Topics: Career & Practice

It's a quick goodbye for many departing associates, new NALP Foundation report finds

Tikkun Olam: When public service is a sacred obligation

Users Keepers: Pirates, zombies and adverse possession

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

JACKSON DELIVERS IMPASSIONED PLEA FOR UNIFIED PARTY

By Howell Raines, Special To the New York Times

- July 18, 1984

In an intense, cadenced speech to the Democratic National Convention, the Rev. Jesse Jackson moved tonight to heal the divisions created by his Presidential candidacy and added his voice to the chorus calling for a party united behind the candidacy of Walter F. Mondale. The black civil rights leader stirred a roar of approval at the convention's second session when he opened his speech with a forthright pledge: I will be proud to support the nominee of this convention for the Presidency of the United States.

Alluding to the bitter disputes that arose within the party after he used language considered derogatory to Jews, Mr. Jackson assumed a tone of contrition as he called for a knitting together of the Democratic constituencies.

No Question of Loyalty

If I have caused anyone discomfort, created pain or revived someone's fears, that was not my truest self, he said. Charge it to my head, not to my heart.

I am not a perfect servant, I am a public servant doing my best against the odds. Be patient. God is not finished with me yet.

Mr. Jackson's speech, evangelical in tone and full of biblical allusions, answered the longstanding question of his loyalty to the party in the general election.

Even in our fractured state, all of us count and all of us fit somewhere, he said. But we have not proven that we can win and make progress without each other. We must come together.

The speech, which marked a dramtic crest in the convention, also capped a day of feverish, behind-the-scenes negotiations intended to deflate the grievances dividing Mr. Mondale, Mr. Jackson and Senator Gary Hart of Colorado.

Mr. Jackson's conciliatory speech came only after a decisive display of political control in which Mr. Mondale won four showdown votes and nailed down a political deal that deflated another challenge by agreeing Mr. Hart's call for a plank limiting the use of American troops abroad.

Mr. Mondale's victory was sealed by the bargain that joined his delegates and Mr. Hart's to vote down a Jackson plank, calling for abolition of runoff primaries, that once threatened to disrupt the convention and divide the party along racial and regional lines. But by that time, Mr. Jackson and Mr. Mondale's advisors had agreed to a compromise on the affirmative action plank that soothed Mr. Jackson and took away the sting of his overall defeat on the platform issues.

Negotiations With Rivals

As the debate was joined on the convention floor over five disputed planks in the party platform, Mr. Mondale's advisers negotiated feverishly to come to terms wih Mr. Hart and Mr. Jackson, his two rivals for the nomination.

The feverish negotiations underscored the fragility of the unity surge that followed the keynote address Monday by Governor Cuomo of New York, in which he called on the party to still its babble of arguing voices and come together behind Mr. Mondale and Representative Geraldine A. Ferraro, his choice as running mate.

Despite Mr. Cuomo's call for unity, the three men seeking the Presidential nomination and their representaives grappled for advantage throughout the day on five plaform issues.

In the end, the superior delegate support and the deal-making of the Mondale team dominated the final shape of the platform and strengthened Mr. Mondale's grasp on this convention after it had been threatened by a series of political missteps over the weekend.

Today, in a display of political muscle, Mr. Mondale was able to carry four showdown votes on platform issues after a sealing a pivotal bargain with Mr. Hart.

The Mondale forces reluctantly accepted the Colorado Senator's plank to limit the use of American troops abroad. In return, the former Vice Presdient got the delegate votes that aassured he would be able to defeat Mr. Jackson on platform porposals that could have divided the party along racial and regional lines.

After the delegates convened at 2 P.M., Pacific time, Mr. Mondale quickly defeated minority planks calling for reduction in military spending and for a pledge that the United States would not make first use of nuclear weapons. Thanks to the compromise with Mr. Hart, the showdown vote on Mr. Jackson's proposal for a plank eliminaing runoff primaries was also voted down.

In a face-saving compromise, Mr. Jackson was able to get the Mondale camp to write in some of his language on an affirmative action plank, but his effort to call for racial quotas was rejected.

High Stakes for Mondale

The stakes in this party feud were high for Mr. Mondale because of the damage done to his image by his unsuccessful attempt to oust Charles T. Manatt as chairman of the Democratic National Committee and his abrupt decision to install Bert Lance, an unpopular figure with many of his supporters, as general chairman of the campaign. So Mr. Mondale and his senior advisers spared no effort in the floor votes or negotiations.

For example, Mayor Andrew Young of Atlanta was called on to put his credentials as a civil rights leader on the line and speak against Mr. Jackson's attempt to pass a plank barring runoff primaries. Mr. Young faced heavy booing but the Mondale side prevailed, as it did later when Mayor Ricahrd Arrington of Birmingham, Ala., gaveled through the compromise on affirmative action. Jackson Apologizes Again

In his address, Mr. Jackson again apologized for any discomfort caused other Democrats by his candidacy, which was marked by reports that he had made a derogatory reference to Jews and favored Arab nations over Israel. He noted a historical alliance beween blacks and Jews in causes such as civil rights.

As Mr. Jckson's speech began to move the audience, he departed from his text and in a rolling summation in gospel cadence he reaffirmed his personal devotion to the abolition of runoffs and other voting rights issues.

But Mr. Jackson also restated his theme of party unity as the overriding goal, as he recited a list of what he saw as President Reagan's offenses against the members of Mr. Jackson's rainbow coalition.

Mr. Reagan is trying to substitute flags and prayer cloths for jobs, food, clothing, education, health care and housing, Mr. Jackson shouted. He has cut food stamps, children's breakfast and lunch programs, the WIC program for pregnant mothers and infants and then he says, 'Let us pray.'

Mr. Mondale hailed the address as one of the great speeches of our time. In noting Mr. Jackson's appeal for forgiveness, Mr. Mondale said, We all make mistakes.

He said he planned to greet Mr. Jackson on the stage Thursday night, when Mr. Mondale expects to deliver his acceptnce speech for the Presidential nomination.

In the struggle over the platform, the candidates also went through the motions of a fight for delegate votes that virtually everyone at the convention believes will result in the nomination of Mr. Mondale on Wednesday night.

Mr. Hart continued with the dogged predictions of victory that have become an object of humor among many delegates. I think what will probably happen is that the inevitability of Mr. Mondale's nomination will not work out, he said.

In an allusion to his earlier characterization of Mr. Mondale as an unexciting party warhorse, Mr. Hart added that the convention should not hand out this nomination like a gold watch for a being a good, loyal Democrat.

Notwithstanding Mr. Hart's statement, Mr. Mondale seemed to have about 100 more votes than the 1,967 required for nomination. Mr. Hart has over 1,200 delegates and Mr. Jackson around 400, according to The Associated Press.

There were fitfull efforts today to forge an alliance of Hart and Jackson delegates with delegates from some ethnic minorities to deny Mr. Mondale a first-ballot victory.

After an impassioned speech by Mr. Jackson this morning, a gathering of black delegates joined in a voice vote approving support of Mr. Jackson on the first ballot. There are 711 black delegates at the convention, of whom about 400 are pledged to Mr. Mondale. About 500 attended this morning's meeting.

Representative Mickey Leland of Texas, chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus, said the vote was informal, indicating it would produce more symbolic support than delegate switches for Mr. Jackson.

Jefferson, Jackson, and Roosevelt Dinner, Wheeling, West Virginia, October 10, 1959

I have always thought it an interesting commentary on history that all Democratic dinners across the country always link together the two founding fathers of our party, Andrew Jackson and Thomas Jefferson. For we ought to realize that neither of them was beloved by all Democrats in their day.

For example, one prominent Democrat is quoted as saying, in 1824: “I feel much alarmed at the prospect of seeing General Jackson President. He is one of the most unfit men I know of for such a place. He has very little respect for law . . . his passions are terrible . . . he is a dangerous man.”

This was the statement of Thomas Jefferson.

And who do you suppose it was, when Mr. Jefferson was President, who described him as “too cowardly to resent foreign outrage on the republic” – a man willing “to seize peaceable Americans and prosecute them for political purposes” – a man who seemed to hold himself “above the law”.

This statement, of course, was made by General Andrew Jackson.

But while we are devoted to them both, I also think it is appropriate today to invoke the memory of another great Democratic President – the man in whose progressive image our party must be forever molded – Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Every American who lived through the past generation has his own favorite memory of Franklin Roosevelt – some incident in that fabulous career that to him best illustrates F.D.R. ’s character and personality.

But, in sorting out these memories, think back to the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia in 1936 – when F.D.R. was re-nominated by wild acclamation. His acceptance speech inspired a crowd of over 100,000 in Franklin Field. But perhaps the most dramatic moment – portraying more than anything else his courage and determination – occurred just prior to the speech, completely hidden from that huge audience. As the President came forward behind the curtain to the front of the stage, leaning on the arm of his son, Jimmy, he suddenly lost his balance and fell to the ground. Lesser men might have lost their composure or dignity – most would have been visibly shaken. But with the aid of his son and the Secret Service, the President was instantly back on his feet before more than a few had observed what had happened. A few seconds later the curtain opened – and he stood there calm and erect, accepting the tremendous roar of the crowd with the familiar Roosevelt smile; and without hesitation, without any sign of recent distress, he launched confidently into one of his most buoyant, most winning speeches. This is the image of Franklin Roosevelt that we honor here today – the man of determination and steel in an hour of crisis – not only the personal crisis of paralysis but the crisis of a nation in panic, the crisis of a world at war, and all the rest.

I think our best guide to the future is the standard set forth by Franklin Roosevelt on that damp Saturday night in Philadelphia. “Governments can err”, the President said, “Presidents do make mistakes; but the immortal Dante tells us that divine justice weighs the sins of the cold-blooded and the sins of the warm-hearted in different scales. Better the occasional faults of a Government that lives in a spirit of charity than the consistent omissions of a Government frozen in the ice of its own indifference.”

The American people today are confronted in their Executive Branch with the very danger of which Franklin Roosevelt warned – “a Government frozen in the ice of its own indifference.” Where Franklin Roosevelt opened new horizons, this Administration sets ceilings. Where Roosevelt urged a spirit of self-sacrifice, we are now lulled into a spirit of self-satisfaction. F.D.R. in 1936 set before us the unfinished tasks of our society, its new opportunities, its unfulfilled promises. In 1959, on the other hand, the President emphasizes the limitations on our economy – and the limitations on our nation.

And when this Administration does act, it acts not with the faith of Franklin Roosevelt – it acts out of fear – fear of the future, of the new and the untested and the unpopular – fear of our weaknesses and even fear of our strength. It is we of the Democratic Party, on the other hand, who must act out of faith. For we place our trust in the people – and in 1960, the people will place their trust in the Democratic Party.

Source : David F. Powers Personal Papers , Box 32, "Jefferson, Jackson and Roosevelt, Wheeling, WV, 10 October 1959." John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

The Lightning Thief (Percy Jackson & the Olympians) Quotes

Recommended quote pages.

- Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

- The Great Gatsby

- Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

- Mere Christianity

- The Hunger Games

- Where the Crawdads Sing

- The Handmaid's Tale

- The Jungle Book

- Percy Jackson

- Mr. Brunner

- originality

- Sally Jackson

- nervousness

- Grover Underwood

- stubbornness

- point of view

- convincing yourself

- half-blood or demigod

- greek mythology

- Help Center

- Gift a Book Club

- Beautiful Collections

- Schedule Demo

Book Platform

- Find a Book

- Motivate Reading

- Community Editors

Authors & Illustrators

- Get Your Book Reviewed

- Submit Original Work

Follow Bookroo

15 Powerful Speech Opening Lines (And How to Create Your Own)

Hrideep barot.

- Public Speaking , Speech Writing

Powerful speech opening lines set the tone and mood of your speech. It’s what grips the audience to want to know more about the rest of your talk.

The first few seconds are critical. It’s when you have maximum attention of the audience. And you must capitalize on that!

Instead of starting off with something plain and obvious such as a ‘Thank you’ or ‘Good Morning’, there’s so much more you can do for a powerful speech opening (here’s a great article we wrote a while ago on how you should NOT start your speech ).

To help you with this, I’ve compiled some of my favourite openings from various speakers. These speakers have gone on to deliver TED talks , win international Toastmaster competitions or are just noteworthy people who have mastered the art of communication.

After each speaker’s opening line, I have added how you can include their style of opening into your own speech. Understanding how these great speakers do it will certainly give you an idea to create your own speech opening line which will grip the audience from the outset!

Alright! Let’s dive into the 15 powerful speech openings…

Note: Want to take your communications skills to the next level? Book a complimentary consultation with one of our expert communication coaches. We’ll look under the hood of your hurdles and pick two to three growth opportunities so you can speak with impact!

1. Ric Elias

Opening: “Imagine a big explosion as you climb through 3,000 ft. Imagine a plane full of smoke. Imagine an engine going clack, clack, clack. It sounds scary. Well I had a unique seat that day. I was sitting in 1D.”

How to use the power of imagination to open your speech?

Putting your audience in a state of imagination can work extremely well to captivate them for the remainder of your talk.

It really helps to bring your audience in a certain mood that preps them for what’s about to come next. Speakers have used this with high effectiveness by transporting their audience into an imaginary land to help prove their point.

When Ric Elias opened his speech, the detail he used (3000 ft, sound of the engine going clack-clack-clack) made me feel that I too was in the plane. He was trying to make the audience experience what he was feeling – and, at least in my opinion, he did.

When using the imagination opening for speeches, the key is – detail. While we want the audience to wander into imagination, we want them to wander off to the image that we want to create for them. So, detail out your scenario if you’re going to use this technique.

Make your audience feel like they too are in the same circumstance as you were when you were in that particular situation.

2. Barack Obama

Opening: “You can’t say it, but you know it’s true.”

3. Seth MacFarlane

Opening: “There’s nowhere I would rather be on a day like this than around all this electoral equipment.” (It was raining)

How to use humour to open your speech?

When you use humour in a manner that suits your personality, it can set you up for a great speech. Why? Because getting a laugh in the first 30 seconds or so is a great way to quickly get the audience to like you.

And when they like you, they are much more likely to listen to and believe in your ideas.

Obama effortlessly uses his opening line to entice laughter among the audience. He brilliantly used the setting (the context of Trump becoming President) and said a line that completely matched his style of speaking.

Saying a joke without really saying a joke and getting people to laugh requires you to be completely comfortable in your own skin. And that’s not easy for many people (me being one of them).

If the joke doesn’t land as expected, it could lead to a rocky start.

Keep in mind the following when attempting to deliver a funny introduction:

- Know your audience: Make sure your audience gets the context of the joke (if it’s an inside joke among the members you’re speaking to, that’s even better!). You can read this article we wrote where we give you tips on how you can actually get to know your audience better to ensure maximum impact with your speech openings

- The joke should suit your natural personality. Don’t make it look forced or it won’t elicit the desired response

- Test the opening out on a few people who match your real audience. Analyze their response and tweak the joke accordingly if necessary

- Starting your speech with humour means your setting the tone of your speech. It would make sense to have a few more jokes sprinkled around the rest of the speech as well as the audience might be expecting the same from you

4. Mohammed Qahtani

Opening: Puts a cigarette on his lips, lights a lighter, stops just before lighting the cigarette. Looks at audience, “What?”

5. Darren Tay

Opening: Puts a white pair of briefs over his pants.

How to use props to begin your speech?

The reason props work so well in a talk is because in most cases the audience is not expecting anything more than just talking. So when a speaker pulls out an object that is unusual, everyone’s attention goes right to it.

It makes you wonder why that prop is being used in this particular speech.

The key word here is unusual . To grip the audience’s attention at the beginning of the speech, the prop being used should be something that the audience would never expect. Otherwise, it just becomes something that is common. And common = boring!

What Mohammed Qahtani and Darren Tay did superbly well in their talks was that they used props that nobody expected them to.

By pulling out a cigarette and lighter or a white pair of underwear, the audience can’t help but be gripped by what the speaker is about to do next. And that makes for a powerful speech opening.

6. Simon Sinek

Opening: “How do you explain when things don’t go as we assume? Or better, how do you explain when others are able to achieve things that seem to defy all of the assumptions?”

7. Julian Treasure

Opening: “The human voice. It’s the instrument we all play. It’s the most powerful sound in the world. Probably the only one that can start a war or say “I love you.” And yet many people have the experience that when they speak people don’t listen to them. Why is that? How can we speak powerfully to make change in the world?”

How to use questions to open a speech?

I use this method often. Starting off with a question is the simplest way to start your speech in a manner that immediately engages the audience.

But we should keep our questions compelling as opposed to something that is fairly obvious.

I’ve heard many speakers start their speeches with questions like “How many of us want to be successful?”

No one is going to say ‘no’ to that and frankly, I just feel silly raising my hand at such questions.

Simon Sinek and Jullian Treasure used questions in a manner that really made the audience think and make them curious to find out what the answer to that question is.

What Jullian Treasure did even better was the use of a few statements which built up to his question. This made the question even more compelling and set the theme for what the rest of his talk would be about.

So think of what question you can ask in your speech that will:

- Set the theme for the remainder of your speech

- Not be something that is fairly obvious

- Be compelling enough so that the audience will actually want to know what the answer to that question will be

8. Aaron Beverley

Opening: Long pause (after an absurdly long introduction of a 57-word speech title). “Be honest. You enjoyed that, didn’t you?”

How to use silence for speech openings?

The reason this speech opening stands out is because of the fact that the title itself is 57 words long. The audience was already hilariously intrigued by what was going to come next.

But what’s so gripping here is the way Aaron holds the crowd’s suspense by…doing nothing. For about 10 to 12 seconds he did nothing but stand and look at the audience. Everyone quietened down. He then broke this silence by a humorous remark that brought the audience laughing down again.

When going on to open your speech, besides focusing on building a killer opening sentence, how about just being silent?

It’s important to keep in mind that the point of having a strong opening is so that the audience’s attention is all on you and are intrigued enough to want to listen to the rest of your speech.

Silence is a great way to do that. When you get on the stage, just pause for a few seconds (about 3 to 5 seconds) and just look at the crowd. Let the audience and yourself settle in to the fact that the spotlight is now on you.

I can’t put my finger on it, but there is something about starting the speech off with a pure pause that just makes the beginning so much more powerful. It adds credibility to you as a speaker as well, making you look more comfortable and confident on stage.

If you want to know more about the power of pausing in public speaking , check out this post we wrote. It will give you a deeper insight into the importance of pausing and how you can harness it for your own speeches. You can also check out this video to know more about Pausing for Public Speaking:

9. Dan Pink

Opening: “I need to make a confession at the outset here. Little over 20 years ago, I did something that I regret. Something that I’m not particularly proud of. Something that in many ways I wish no one would ever know but that here I feel kind of obliged to reveal.”

10. Kelly McGonigal

Opening: “I have a confession to make. But first I want you to make a little confession to me.”

How to use a build-up to open your speech?

When there are so many amazing ways to start a speech and grip an audience from the outset, why would you ever choose to begin your speech with a ‘Good morning?’.

That’s what I love about build-ups. They set the mood for something awesome that’s about to come in that the audience will feel like they just have to know about.

Instead of starting a speech as it is, see if you can add some build-up to your beginning itself. For instance, in Kelly McGonigal’s speech, she could have started off with the question of stress itself (which she eventually moves on to in her speech). It’s not a bad way to start the speech.

But by adding the statement of “I have a confession to make” and then not revealing the confession for a little bit, the audience is gripped to know what she’s about to do next and find out what indeed is her confession.

11. Tim Urban

Opening: “So in college, I was a government major. Which means that I had to write a lot of papers. Now when a normal student writes a paper, they might spread the work out a little like this.”

12. Scott Dinsmore

Opening: “8 years ago, I got the worst career advice of my life.”

How to use storytelling as a speech opening?

“The most powerful person in the world is the storyteller.” Steve Jobs

Storytelling is the foundation of good speeches. Starting your speech with a story is a great way to grip the audience’s attention. It makes them yearn to want to know how the rest of the story is going to pan out.

Tim Urban starts off his speech with a story dating back to his college days. His use of slides is masterful and something we all can learn from. But while his story sounds simple, it does the job of intriguing the audience to want to know more.

As soon as I heard the opening lines, I thought to myself “If normal students write their paper in a certain manner, how does Tim write his papers?”

Combine such a simple yet intriguing opening with comedic slides, and you’ve got yourself a pretty gripping speech.

Scott Dismore’s statement has a similar impact. However, just a side note, Scott Dismore actually started his speech with “Wow, what an honour.”

I would advise to not start your talk with something such as that. It’s way too common and does not do the job an opening must, which is to grip your audience and set the tone for what’s coming.

13. Larry Smith

Opening: “I want to discuss with you this afternoon why you’re going to fail to have a great career.”

14. Jane McGonigal

Opening: “You will live 7.5 minutes longer than you would have otherwise, just because you watched this talk.”

How to use provocative statements to start your speech?

Making a provocative statement creates a keen desire among the audience to want to know more about what you have to say. It immediately brings everyone into attention.

Larry Smith did just that by making his opening statement surprising, lightly humorous, and above all – fearful. These elements lead to an opening statement which creates so much curiosity among the audience that they need to know how your speech pans out.

This one time, I remember seeing a speaker start a speech with, “Last week, my best friend committed suicide.” The entire crowd was gripped. Everyone could feel the tension in the room.

They were just waiting for the speaker to continue to know where this speech will go.

That’s what a hard-hitting statement does, it intrigues your audience so much that they can’t wait to hear more! Just a tip, if you do start off with a provocative, hard-hitting statement, make sure you pause for a moment after saying it.

Silence after an impactful statement will allow your message to really sink in with the audience.

Related article: 5 Ways to Grab Your Audience’s Attention When You’re Losing it!

15. Ramona J Smith

Opening: In a boxing stance, “Life would sometimes feel like a fight. The punches, jabs and hooks will come in the form of challenges, obstacles and failures. Yet if you stay in the ring and learn from those past fights, at the end of each round, you’ll be still standing.”

How to use your full body to grip the audience at the beginning of your speech?

In a talk, the audience is expecting you to do just that – talk. But when you enter the stage and start putting your full body into use in a way that the audience does not expect, it grabs their attention.

Body language is critical when it comes to public speaking. Hand gestures, stage movement, facial expressions are all things that need to be paid attention to while you’re speaking on stage. But that’s not I’m talking about here.

Here, I’m referring to a unique use of the body that grips the audience, like how Ramona did. By using her body to get into a boxing stance, imitating punches, jabs and hooks with her arms while talking – that’s what got the audience’s attention.

The reason I say this is so powerful is because if you take Ramona’s speech and remove the body usage from her opening, the entire magic of the opening falls flat.

While the content is definitely strong, without those movements, she would not have captured the audience’s attention as beautifully as she did with the use of her body.

So if you have a speech opening that seems slightly dull, see if you can add some body movement to it.

If your speech starts with a story of someone running, actually act out the running. If your speech starts with a story of someone reading, actually act out the reading.

It will make your speech opening that much more impactful.

Related article: 5 Body Language Tips to Command the Stage

Level up your public speaking in 15 minutes!

Get the exclusive Masterclass video delivered to your inbox to see immediate speaking results.

You have successfully joined our subscriber list.

Final Words

So there it is! 15 speech openings from some of my favourite speeches. Hopefully, these will act as a guide for you to create your own opening which is super impactful and sets you off on the path to becoming a powerful public speaker!

But remember, while a speech opening is super important, it’s just part of an overall structure.

If you’re serious about not just creating a great speech opening but to improve your public speaking at an overall level, I would highly recommend you to check out this course: Acumen Presents: Chris Anderson on Public Speaking on Udemy. Not only does it have specific lectures on starting and ending a speech, but it also offers an in-depth guide into all the nuances of public speaking.

Being the founder of TED Talks, Chris Anderson provides numerous examples of the best TED speakers to give us a very practical way of overcoming stage fear and delivering a speech that people will remember. His course has helped me personally and I would definitely recommend it to anyone looking to learn public speaking.

No one is ever “done” learning public speaking. It’s a continuous process and you can always get better. Keep learning, keep conquering and keep being awesome!

Lastly, if you want to know how you should NOT open your speech, we’ve got a video for you:

Enroll in our transformative 1:1 Coaching Program

Schedule a call with our expert communication coach to know if this program would be the right fit for you

How to Negotiate: The Art of Getting What You Want

10 Hand Gestures That Will Make You More Confident and Efficient

Interrupted while Speaking: 8 Ways to Prevent and Manage Interruptions

- [email protected]

- +91 98203 57888

Get our latest tips and tricks in your inbox always

Copyright © 2023 Frantically Speaking All rights reserved

Kindly drop your contact details so that we can arrange call back

Select Country Afghanistan Albania Algeria AmericanSamoa Andorra Angola Anguilla Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Armenia Aruba Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bermuda Bhutan Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Brazil British Indian Ocean Territory Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Canada Cape Verde Cayman Islands Central African Republic Chad Chile China Christmas Island Colombia Comoros Congo Cook Islands Costa Rica Croatia Cuba Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Djibouti Dominica Dominican Republic Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Faroe Islands Fiji Finland France French Guiana French Polynesia Gabon Gambia Georgia Germany Ghana Gibraltar Greece Greenland Grenada Guadeloupe Guam Guatemala Guinea Guinea-Bissau Guyana Haiti Honduras Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iraq Ireland Israel Italy Jamaica Japan Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kiribati Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Latvia Lebanon Lesotho Liberia Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Maldives Mali Malta Marshall Islands Martinique Mauritania Mauritius Mayotte Mexico Monaco Mongolia Montenegro Montserrat Morocco Myanmar Namibia Nauru Nepal Netherlands Netherlands Antilles New Caledonia New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria Niue Norfolk Island Northern Mariana Islands Norway Oman Pakistan Palau Panama Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru Philippines Poland Portugal Puerto Rico Qatar Romania Rwanda Samoa San Marino Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia Seychelles Sierra Leone Singapore Slovakia Slovenia Solomon Islands South Africa South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Suriname Swaziland Sweden Switzerland Tajikistan Thailand Togo Tokelau Tonga Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Turks and Caicos Islands Tuvalu Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates United Kingdom United States Uruguay Uzbekistan Vanuatu Wallis and Futuna Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe land Islands Antarctica Bolivia, Plurinational State of Brunei Darussalam Cocos (Keeling) Islands Congo, The Democratic Republic of the Cote d'Ivoire Falkland Islands (Malvinas) Guernsey Holy See (Vatican City State) Hong Kong Iran, Islamic Republic of Isle of Man Jersey Korea, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Republic of Lao People's Democratic Republic Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Macao Macedonia, The Former Yugoslav Republic of Micronesia, Federated States of Moldova, Republic of Mozambique Palestinian Territory, Occupied Pitcairn Réunion Russia Saint Barthélemy Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan Da Cunha Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint Martin Saint Pierre and Miquelon Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Sao Tome and Principe Somalia Svalbard and Jan Mayen Syrian Arab Republic Taiwan, Province of China Tanzania, United Republic of Timor-Leste Venezuela, Bolivarian Republic of Viet Nam Virgin Islands, British Virgin Islands, U.S.

Help inform the discussion

Presidential Speeches

December 6, 1830: second annual message to congress, about this speech.

Andrew Jackson

December 06, 1830

The President reviews the various pieces of domestic legislation to reform the nation's infrastructure and public works system. Jackson further proposes that all federal surplus money be distributed among the states to be used for internal improvements at the discretion of each, individual state.

Fellow citizens of the Senate and House of Representatives:

The pleasure I have in congratulating you upon your return to your constitutional duties is much heightened by the satisfaction which the condition of our beloved country at this period justly inspires. The beneficent Author of All Good has granted to us during the present year health, peace, and plenty, and numerous causes for joy in the wonderful success which attends the progress of our free institutions.

With a population unparalleled in its increase, and possessing a character which combines the hardihood of enterprise with the considerateness of wisdom, we see in every section of our happy country a steady improvement in the means of social intercourse, and correspondent effects upon the genius and laws of our extended republic.

The apparent exceptions to the harmony of the prospect are to be referred rather to inevitable diversities in the various interests which enter into the composition of so extensive a whole than any want of attachment to the union—interests whose collisions serve only in the end to foster the spirit of conciliation and patriotism so essential to the preservation of that union which I most devoutly hope is destined to prove imperishable.

In the midst of these blessings we have recently witnessed changes in the conditions of other nations which may in their consequences call for the utmost vigilance, wisdom, and unanimity in our councils, and the exercise of all the moderation and patriotism of our people.

The important modifications of their government, effected with so much courage and wisdom by the people of France, afford a happy presage of their future course, and have naturally elicited from the kindred feelings of this nation that spontaneous and universal burst of applause in which you have participated. In congratulating you, my fellow citizens, upon an event so auspicious to the dearest interests of mankind I do no more than respond to the voice of my country, without transcending in the slightest degree that salutary maxim of the illustrious Washington which enjoins an abstinence from all interference with the internal affairs of other nations. From a people exercising in the most unlimited degree the right of self-government, and enjoying, as derived from this proud characteristic, under the favor of Heaven, much of the happiness with which they are blessed; a people who can point in triumph to their free institutions and challenge comparison with the fruits they bear, as well as with the moderation, intelligence, and energy with which they are administered—from such a people the deepest sympathy was to be expected in a struggle for the sacred principles of liberty, conducted in a spirit every way worthy of the cause, and crowned by a heroic moderation which has disarmed revolution of its terrors. Not withstanding the strong assurances which the man whom we so sincerely love and justly admire has given to the world of the high character of the present King of the French, and which if sustained to the end will secure to him the proud appellation of Patriot King, it is not in his success, but in that of the great principle which has borne him to the throne—the paramount authority of the public will—that the American people rejoice.

I am happy to inform you that the anticipations which were indulged at the date of my last communication on the subject of our foreign affairs have been fully realized in several important particulars.

An arrangement has been effected with Great Britain in relation to the trade between the United States and her West India and North American colonies which has settled a question that has for years afforded matter for contention and almost uninterrupted discussion, and has been the subject of no less than six negotiations, in a manner which promises results highly favorable to the parties.

The abstract right of Great Britain to monopolize the trade with her colonies or to exclude us from a participation therein has never been denied by the United States. But we have contended, and with reason, that if at any time Great Britain may desire the productions of this country as necessary to her colonies they must be received upon principles of just reciprocity, and, further, that it is making an invidious and unfriendly distinction to open her colonial ports to the vessels of other nations and close them against those of the United States.

Antecedently to 1794 a portion of our productions was admitted into the colonial islands of Great Britain by particular concessions, limited to the term of one year, but renewed from year to year. In the transportation of these productions, however, our vessels were not allowed to engage, this being a privilege reserved to British shipping, by which alone our produce could be taken to the islands and theirs brought to us in return. From Newfoundland and her continental possessions all our productions, as well as our vessels, were excluded, with occasional relaxations, by which, in seasons of distress, the former were admitted in British bottoms.