Skip navigation

- Log in to UX Certification

World Leaders in Research-Based User Experience

Design thinking in practice: research methodology.

January 10, 2021 2021-01-10

- Email article

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Twitter

Project Overview

Over the last decade, we have seen design thinking gain popularity across industries. Nielsen Norman Group conducted a long-term research project to understand design thinking in practice. The research project included 3 studies involving more than 1000 participants and took place from 2018 to 2020:

- Intercepts and interviews with 87 participants

- Digital survey with 1067 respondents

- In-depth case study at an institution practicing design thinking

The primary goals of the project were to investigate the following:

- How do practitioners learn and use design thinking?

- How does design thinking provide value to individuals and organizations?

- What makes design thinking successful or unsuccessful?

This description of what we did may be useful in helping you interpret our results and apply them to your own design-thinking practice.

Project Findings

The findings from this research are shared in the following articles and videos:

- What Is Design Thinking, Really? (What Practitioners Say) (Article)

- How UX Professionals Define Design Thinking in Practice (Video)

- Design Thinking: The Learner’s Journey (Article)

In This Article:

Study 1: intercepts and interviews , study 2: digital survey, study 3: case study .

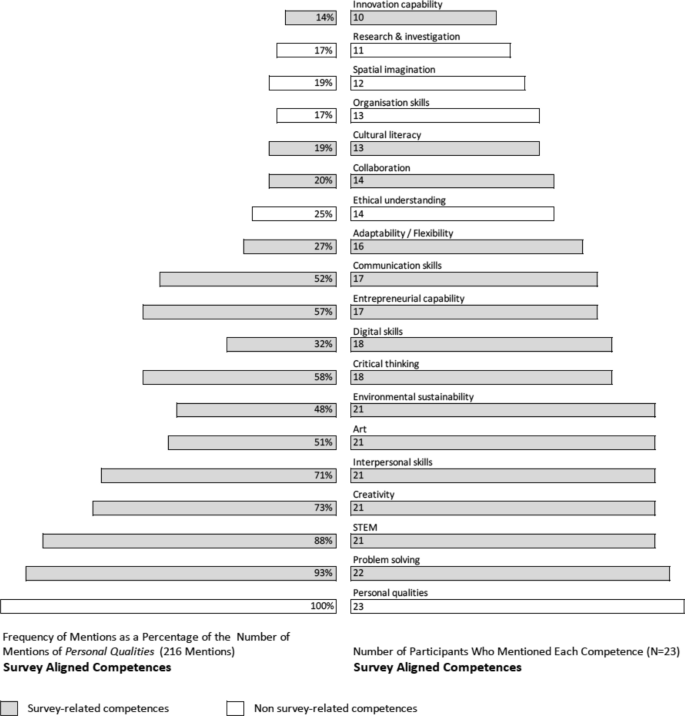

In the first study we investigated how UX and design professionals define design thinking.

This study consisted of 71 in-person intercepts in Washington DC, San Francisco, Boston, and North Carolina and 16 remote interviews over the phone and via video conferencing. These 87 participants were UX professionals from a diverse range of countries with varying roles and experience.

Intercepts consisted of two questions:

- What do think of when you hear the phrase “design thinking”?

- How would you define design thinking?

Interviews consisted of 10 questions, excluding demographic-related questions:

- What are the first words that come to mind when I say “design thinking”?

- Can you tell me more about [word they supplied in response to question 1]?

- How would you define design thinking? Why?

- What does it mean to practice design thinking?

- What are the positive or negative effects of design thinking?

- Products and services

- Clients/customers

- Using this scale, what is your experience using design thinking?

- Using this same scale, how successful has design thinking been in your experience?

- What could have been better?

- What is good about design thinking? What is bad about design thinking?

Our second study consisted of a qualitative digital survey that ran for two months and had 1067 professional respondents primarily from UX-related fields. The survey had 14 questions, excluding demographic-related questions. An alternative set of 4 questions was shown to those with little to no experience using design thinking.

- Which of the following best describes your experience with design thinking?

- Where did you learn design thinking?

- UX maturity

- Frequency of crossteam collaboration

- User-centered approach

- Research-driven decision making

- How often do you, yourself, practice design thinking?

- In your own words, what does it mean to practice design thinking?

- When do you use design thinking?

- What methods or exercises are used?

- In what situations is each one used and why?

- Which ones are done individually versus as a group?

- How is each exercise executed?

- Gives your organization a competitive advantage

- Drives innovation

- Fosters collaboration

- Provides structure to the organization

- Increases likelihood of success

- Please describe a situation where design thinking positively influenced your organization and why it was successful.

- Please describe a situation where design thinking may have negatively influenced your organization and why it was negative.

- Design thinking negatively affects efficiency.

- Design thinking requires a collaborative environment to work well.

- Anyone can learn and practice design thinking.

- Design thinking is rigid.

- Design thinking requires all involved to be human-centered.

- Design thinking takes a lot of time.

- Design thinking has low return on investment.

- Design thinking empowers personal growth.

- Design thinking grows interpersonal relationships.

- Design thinking improves organizational progress.

The 1067 survey participants had diverse backgrounds: they held varying roles across industries and were located across the globe. 94 responses were invalid, so we excluded them from our analysis.

The majority of participants (33%) were UX designers, followed by UX researchers (13%) and UX consultants (12%).

Of participants who responded “Other”, the most common response provided was an executive role (n=20). This included roles such as CEO, VP, director, founder, and “head of.” Other mentioned roles included service designer (n=17), manager (n=14), business designer or business analyst (n=11), and educator (including teacher, instructor, and curriculum designer) (n=11).

Geographically, we had respondents from 67 different countries. The majority of survey participants work in the United States (34%), followed by India (8%), United Kingdom (7%), and Canada (5%).

Our survey participants also represented diverse industries, with the majority in software (22%) and finance or insurance (14%).

Of participants who responded Other , the most common response provided was agency or consulting (n=26), followed by telecommunications (n=17), marketing (n=8), and tourism (n=7).

Our third and final study consisted of an in-person case study at a large, public ecommerce company. The case study involved 9 interviews with company employees, 6 observation sessions of design-thinking (or related) workshops, and an internal resource and literature audit.

The interviews were 1-hour long and semistructured. Of the 8 participants, 3 were on the same team but had different roles: 1 UX designer, 1 product manager, and 1 engineer. The other 5 interviewees (3 design leaders and 2 UX designers) worked in different groups across the organization. Each participant completed the same digital survey from the second study prior to interviewing.

In addition to interviews, we conducted 6 observation sessions: 3 design-thinking workshops, 2 meetings, and 1 lunch-and-learn. After the workshops, all participants were invited to fill out a survey about the workshop. The survey had 5 questions:

- We achieved our goal of [x].

- The time and resources spent to conduct the workshop were worth it.

- What aspects were of greatest value to you, and why?

- Where there any aspects you felt were not useful, and why?

- Will the workshop or its output impact any of your future work? If so, how?

- What is your role?

Lastly, we conducted a resource and literature audit of the company’s internal resources related to design thinking available to employees.

Related Courses

Generating big ideas with design thinking.

Unearthing user pain points to drive breakthrough design concepts

Interaction

Effective Ideation Techniques for UX Design

Systematic methods for creative solutions to any UX design or redesign challenge

Personas: Turn User Data Into User-Centered Design

Successfully turn user data into user interfaces. Learn how to create, maintain and utilize personas throughout the UX design process.

Related Topics

- Design Process Design Process

- Research Methods

Learn More:

The Role of Design

Don Norman · 5 min

Design Thinking Activities

Sarah Gibbons · 5 min

Design Thinking: Top 3 Challenges and Solutions

Related Articles:

Crafting Product-Specific Design Principles to Support Better Decision Making

Maria Rosala · 5 min

Design Thinking 101

Sarah Gibbons · 7 min

The 6 Steps to Roadmapping

Sarah Gibbons · 8 min

3 Types of Roadmaps in UX and Product Design

User Need Statements: The ‘Define’ Stage in Design Thinking

Sarah Gibbons · 9 min

What Is Design Thinking, Really? (What Practitioners Say)

⚡️ Get 30% off EVERYTHING ⚡️

Use coupon:

A Complete Guide to Primary and Secondary Research in UX Design

To succeed in UX design, you must know what UX research methods to use for your projects.

This impacts how you:

- Understand and meet user needs

- Execute strategic and business-driven solutions

- Differentiate yourself from other designers

- Be more efficient in your resources

- Innovate within your market

Primary and secondary research methods are crucial to uncovering this. The former is when you gather firsthand data directly from sources, while the latter synthesizes existing data and translates them into insights and recommendations.

Let's dive deep into each type of research method and its role in UX research.

If you are still hungry to learn more, specifically how to apply it practically in the real world, you should check out Michael Wong's UX research course . He teaches you the exact process and tactics he used that helped him build a UX agency that generated over $10M+ million in revenue.

What is p rimary research in UX design

Primary UX research gathers data directly from the users to understand their needs, behaviors, and preferences.

It's done through interviews, surveys, and observing users as they interact with a product.

Primary research in UX: When and why to use it

Primary research typically starts at the start of a UX project. This is so that the design process is grounded in a deep understanding of user needs and behaviors.

By collecting firsthand information early on, teams can tailor their designs to address real user problems.

Here are the reasons why primary research is important in UX design:

1. It fast-tracks your industry understanding

Your knowledge about the industry may be limited at the start of the project. Primary research helps you get up to speed because you interact directly with real customers. As a result, this allows you to work more effectively.

Example: Imagine you're designing an app for coffee lovers. But you're not a coffee drinker yourself. Through user interviews, you learn how they prefer to order their favorite drink, what they love or hate about existing coffee apps, and their "wishlist" features by talking directly to them.

This crucial information will guide you on what to focus on in later stages when you do the actual designing.

2. You'll gain clarity and fill knowledge gaps

There are always areas we know less about than we'd like. Primary research helps fill these gaps by observing user preferences and needs directly.

Example: Let's say you're working on a website for online learning. You might assume that users prefer video lessons over written content, but your survey results show that many users prefer written material because they can learn at their own pace.

With that in mind, you'll prioritize creating user-friendly design layouts for written lessons.

3. You get to test and validate any uncertainties

When unsure about a feature, design direction, or user preference, primary research allows you to test these elements with real users.

This validation process helps you confidently move forward since you have data backing your decisions.

Example: You're designing a fitness app and can't decide between a gamified experience (with points and levels) or a more straightforward tracking system.

By prototyping both options and testing them with a group of users, you discover that the gamified experience concept resonates more.

Users are more motivated when they gain points and progress levels. As a result, you pivot to designing a better-gamified experience.

Types of primary research methods in UX design

Here's a detailed look at common primary research methods in UX:

1. User interviews

- What is it: User interviews involve one-on-one conversations with users to gather detailed insights, opinions, and feedback about their experiences with a product or service.

- Best used for: Gathering qualitative insights on user needs, motivations, and pain points.

- Tools: Zoom and Google Meet for remote interviews; Calendly for scheduling; Otter.ai for transcription.

- What is it: Surveys are structured questionnaires designed to collect quantitative data on user preferences, behaviors, and demographics.

- Best used for: Collecting data from many users to identify patterns and trends.

- Tools: Google Forms, SurveyMonkey, and Typeform for survey creation; Google Sheets and Notion for note taking.

3. Usability testing

- What is it: Usability testing involves observing users interact with a prototype or the actual product to identify usability issues and areas for improvement.

- Best used for: Identifying and addressing usability problems.

- Tools: FigJam, Lookback.io , UserTesting, Hotjar for conducting and recording sessions; InVision, Figma for prototype testing; Google Sheets to log usability issues and track task completion rates.

4. Contextual inquiry

- What is it: This method involves observing and interviewing users in their natural environment to understand how they use a product in real-life situations.

- Best used for: Gaining deep insights into user behavior and the context in which a product is used.

- Tools: GoPro or other wearable cameras for in-field recording; Evernote for note-taking; Miro for organizing insights.

5. Card sorting

- What is it: Card sorting is when users organize and categorize content or information.

- Best used for: Designing or evaluating the information architecture of a website or application.

- Tools: FigJam, Optimal Workshop, UXPin, and Trello for digital card sorting; Mural for collaborative sorting sessions.

6. Focus groups

- What is it: Group discussions with users that explore their perceptions, attitudes, and opinions about a product.

- Best used for: Gathering various user opinions and ideas in an interactive setting.

- Tools: Zoom, Microsoft Teams for remote focus groups; Menti or Slido for real-time polling and feedback.

7. Diary studies

- What is it: A method where users record their experiences, thoughts, and frustrations while interacting with a product over a certain period of time.

- Best used for: Understanding long-term user behavior, habits, and needs.

- Tools: Dscout, ExperienceFellow for mobile diary entries; Google Docs for simple text entries.

8. Prototype testing

- What is it: Prototype testing is when users evaluate the usability and design of early product prototypes with users.

- Best used for: Identifying usability issues and gathering feedback on design concepts

- Tools: Figma for creating and sharing prototypes; Maze for unmoderated testing and analytics.

9. Eye-tracking

- What is it: A method that analyzes where and how long users look at different areas on a screen.

- Best used for: Understanding user attention, readability, and visual hierarchy effectiveness.

- Tools: Tobii, iMotions for hardware; Crazy Egg for website heatmaps as a simpler alternative.

10. A/B testing

- What is it: A/B testing compares two or more versions of a webpage or app feature to determine which performs better in achieving specific goals.

- Best used for: Making data-driven decisions on design elements that impact user behavior.

- Tools: Optimizely, Google Optimize for web-based A/B testing; VWO for more in-depth analysis and segmentation.

11. Field studies

- What is it: Research done in real-world settings to observe and analyze user behavior and interactions in their natural environment.

- Best used for: Gaining insights into how products are used in real-world contexts and identifying unmet user needs.

- Tools: Notability, OneNote for note-taking; Voice Memos for audio recording; Trello for organizing observations.

12. Think-aloud protocols

- What is it: A method involves users verbalizing their thought process while interacting with a product. It helps uncover their decision-making process and pain points.

- Best used for: Understanding user reasoning, expectations, and experiences when using the product.

- Tools: UsabilityHub, Morae for recording think-aloud sessions; Zoom for remote testing with screen sharing.

Challenges of primary research in UX

Here are the obstacles that UX professionals may face with primary research:

- Time-consuming : Primary research requires significant planning, conducting, and analyzing. This is particularly relevant for methods that involve a lot of user interaction.

- Resource intensive : A considerable amount of resources is needed, including specialized tools or skills for data collection and analysis.

- Recruitment difficulties : Finding and recruiting suitable participants willing to put in the effort can be challenging and costly.

- Bias and validity : The risk of bias in collecting and interpreting data highlights the importance of carefully designing the research strategy. This is so that the findings are accurate and reliable.

What is secondary research in UX design

Once primary research is conducted, secondary research analyzes and converts this data into insights. They may also find common themes and ideas and convert them into meaningful recommendations.

Using journey maps, personas, and affinity diagrams can help them better understand the problem.

Secondary research also involves reviewing existing research, published books, articles, studies, and online information. This includes competitor websites and online analytics to support design ideas and concepts.

Secondary research in UX: Knowing when and why to use it

Secondary research is a flexible method in the design process. It fits in both before and after primary research.

At the project's start, looking at existing research and what's already known can help shape your design strategy. This groundwork helps you understand the design project in a broader context.

After completing your primary research, secondary research comes into play again. This time, it's about synthesizing your findings and forming insights or recommendations for your stakeholders.

Here's why it's important in your design projects:

1. It gives you a deeper understanding of your existing research

Secondary research gathers your primary research findings to identify common themes and patterns. This allows for a more informed approach and uncovers opportunities in your design process.

Example: When creating personas or proto-personas for a fitness app, you might find common desires for personalized workout plans and motivational features.

This data shapes personas like "Fitness-focused Fiona," a detailed profile that embodies a segment of your audience with her own set of demographics, fitness objectives, challenges, and likes.

2. Learn more about competitors

Secondary research in UX is also about leveraging existing data in the user landscape and competitors.

This may include conducting a competitor or SWOT analysis so that your design decisions are not just based on isolated findings but are guided by a comprehensive overview. This highlights opportunities for differentiation and innovation.

Example: Suppose you're designing a budgeting app for a startup. You can check Crunchbase, an online database of startup information, to learn about your competitors' strengths and weaknesses.

If your competitor analysis reveals that all major budgeting apps lack personalized advice features, this shows an opportunity for yours to stand out by offering customized budgeting tips and financial guidance.

Types of secondary research methods in UX

1. competitive analysis.

- What is it: Competitive analysis involves systematically comparing your product with its competitors in the market. It's a strategic tool that helps identify where your product stands about the competition and what unique value proposition it can offer.

- Best used for: Identifying gaps in the market that your product can fill, understanding user expectations by analyzing what works well in existing products, and pinpointing areas for improvement in your own product.

- Tools: Google Sheets to organize and visualize your findings; Crunchbase and SimilarWeb to look into competitor performance and market positioning; and UserVoice to get insights into what users say about your competitors.

2. Affinity mapping

- What is it: A collaborative sorting technique used to organize large sets of information into groups based on their natural relationships.

- Best used for: Grouping insights from user research, brainstorming sessions, or feedback to identify patterns, themes, and priorities. It helps make sense of qualitative data, such as user interview transcripts, survey responses, or usability test observations.

- Tools: Miro and FigJam for remote affinity mapping sessions.

3. Customer journey mapping

- What is it: The process of creating a visual representation of the customer's experience with a product or service over time and across different touchpoints.

- Best used for: Visualizing the user's path from initial engagement through various interactions to the final goal.

- Tools: FigJam and Google Sheets for collaborative journey mapping efforts.

4. Literature and academic review

- What is it: This involves examining existing scholarly articles, books, and other academic publications relevant to your design project. The goal is to deeply understand your project's theoretical foundations, past research findings, and emerging trends.

- Best used for: Establishing a solid theoretical framework for your design decisions. A literature review can uncover insights into user behavior and design principles that inform your design strategy.

- Tools: Academic databases like Google Scholar, JSTOR, and specific UX/UI research databases. Reference management tools like Zotero and Mendeley can help organize your sources and streamline the review process.

Challenges of secondary research in UX design

These are the challenges that UX professionals might encounter when carrying out secondary research:

- Outdated information : In a world where technology changes fast, the information you use must be current, or it might not be helpful.

- Challenges with pre-existing data : Using data you didn't collect yourself can be tricky because you have less control over its quality. Always review how it was gathered to avoid mistakes.

- Data isn't just yours : Since secondary data is available to everyone, you won't be the only one using it. This means your competitors can access similar findings or insights.

- Trustworthiness : Look into where your information comes from so that it's reliable. Watch out for any bias in the data as well.

The mixed-method approach: How primary and secondary research work together

Primary research lays the groundwork, while secondary research weaves a cohesive story and connects the findings to create a concrete design strategy.

Here's how this mixed-method approach works in a sample UX project for a health tech app:

Phase 1: Groundwork and contextualization

- User interviews and surveys (Primary research) : The team started their project by interviewing patients and healthcare providers. The objective was to uncover the main issues with current health apps and what features could enhance patient care.

- Industry and academic literature review (Secondary research) : The team also reviewed existing literature on digital health interventions, industry reports on health app trends, and case studies on successful health apps.

Phase 2: Analysis and strategy formulation

- Affinity mapping (Secondary research) : Insights from the interviews and surveys were organized using affinity mapping. It revealed key pain points like needing more personalized and interactive care plans.

- Competitive benchmarking (Secondary research) : The team also analyzed competitors’ apps through secondary research to identify common functionalities and gaps. They noticed a lack of personalized patient engagement and, therefore, positioned their app to fill this void in the market.

Phase 3: Design and validation

- Prototyping (Secondary research) : With a good grasp of what users need and the opportunities in the market, the startup created prototypes. These prototypes include AI-powered personalized care plans, reminders for medications, and interactive tools to track health.

- Usability testing (Primary research) : The prototypes were tested with a sample of the target user group, including patients and healthcare providers. Feedback was mostly positive, especially for the personalized care plans. This shows that the app has the potential to help patients get more involved in their health.

Phase 4: Refinement and market alignment

- Improving design through iterations: The team continuously refined the app's design based on feedback from ongoing usability testing.

- Ongoing market review (Secondary research) : The team watched for new studies, healthcare reports, and competitors' actions. This helped them make sure their app stayed ahead in digital health innovation.

Amplify your design impact and impress your stakeholders in 10+ hours

Primary and secondary research methods are part of a much larger puzzle in UX research.

However, understanding the theoretical part is not enough to make it as a UX designer nowadays.

The reason?

UX design is highly practical and constantly evolving. To succeed in the field, UX designers must do more than just design.

They understand the bigger picture and know how to deliver business-driven design solutions rather than designs that look pretty.

Sometimes, the best knowledge comes from those who have been there themselves. That's why finding the right mentor with experience and who can give practical advice is crucial.

In just 10+ hours, the Practical UX Research & Strategy Course dives deep into strategic problem-solving. By the end, you'll know exactly how to make data-backed solutions your stakeholders will get on board with.

Master the end-to-end UX research workflow, from formulating the right user questions to executing your research strategy and effectively presenting your findings to stakeholders.

Learn straight from Mizko—a seasoned industry leader with a track record as a successful designer, $10M+ former agency owner, and advisor for tech startups.

This course equips you with the skills to:

- Derive actionable insights through objective-driven questions.

- Conduct unbiased, structured interviews.

- Select ideal participants for quality data.

- Create affinity maps from research insights.

- Execute competitor analysis with expertise.

- Analyze large data sets and user insights systematically.

- Transform research and data into actionable frameworks and customer journey maps.

- Communicate findings effectively and prioritize tasks for your team.

- Present metrics and objectives that resonate with stakeholders.

Designed for flexible and independent learning, this course allows you to progress independently.

With 4000+ designers from top tech companies like Google, Meta, and Squarespace among its alumni, this course empowers UX designers to integrate research skills into their design practices.

Here's what students have to say about the 4.9/5 rated course:

"I'm 100% more confident when talking to stakeholders about User Research & Strategy and the importance of why it needs to be included in the process. I also have gained such a beautiful new understanding of my users that greatly influences my designs. All of the "guesswork" that I was doing is now real, meaningful work that has stats and research behind it." - Booking.com Product Designer Alyssa Durante

"I had no proper clarity of how to conduct a research in a systematically form which actually aligns to the project. Now I have a Step by Step approach from ground 0 to final synthesis." - UX/UI Designer Kaustav Das Biswas

"The most impactful element has been the direct application of the learnings in my recent projects at Amazon. Integrating the insights gained from the course into two significant projects yielded outstanding results, significantly influencing both my career and personal growth. This hands-on experience not only enhanced my proficiency in implementing UX strategies but also bolstered my confidence in guiding, coaching, mentoring, and leading design teams." - Amazon.com UX designer Zohdi Rizvi

Gain expert UX research skills and outshine your competitors.

Related blogs

Discover the most practical UX research courses available in 2024. Choose the best program to enhance your skills and prepare for a career in user experience design.

Master the art of UX research with our ultimate guide. Explore methodologies, utilize the best tools, and adopt industry best practices for impactful user experience research.

Discover the 16 best UX research tools in 2024. From analytics to user testing, our guide helps you choose the right tools to elevate your user experience research and design.

Join our newsletter

Get exclusive content and become a part of the Designership community

The modern guide to web accessibility

The 4 types of research methods in ui/ux design (and when to use them).

- User Experience

- 4 minute read

- by, Rich Staats

Design research is a necessary part of creating a user-centered product. When done right, you’re able to gather data that helps you:

- Identify and solve relevant design problems.

- Better understand the product’s end users.

- Improve your designs based on data-driven research.

Though there are many different ways to collect data and do design research, they can broadly be categorized as either primary, secondary, exploratory, or evaluative research. In this article, we’ll explain these four types of research methods in the context of UI/UX design and when you should use them in your design process.

Primary research

Primary research is the simplest (and perhaps most effective) way to come up with data to get a better understanding of the audience for which you’re designing. The purpose of primary research is to validate design ideas and concepts early on in the design process. The data you collect from primary research allows you to design meaningful, user-centered solutions.

Let’s take a look at some examples of primary research:

Conducting interviews with individuals or in small groups is a great starting point, and there are many ways to go about it. Depending on your project, you might conduct direct interviews or indirect interviews. Direct interviews are simple question-answer format interviews whereas indirect interviews are set up in a more conversational style. You’ll also have to decide whether you’ll interview people in-person or remotely.

Focus groups

Focus groups are structured, group interviews in which a moderator guides the discussion. As a UI/UX designer, you might consider using this research method when you need to gather user insight quickly.

Usability testing

Once you develop a prototype, you can recruit test participants and conduct usability tests to uncover foundational issues with the product’s user experience and gather user feedback. The idea is to define user goals and turn them into realistic task scenarios that the test participants would have to complete using your prototype.

Secondary research

Secondary research is when you use existing books, articles, or research material to validate your design ideas and concepts or support your primary research. For example, you might want to use the material you gather from secondary research to:

- Explain the context behind your UI design.

- Build a case for your design decisions.

- Reinforce the data you gathered from primary research.

Generally speaking, secondary research is much easier (and faster) to do than primary research. You’ll be able to find most of the information you need on the internet, in the library, or your company’s archives. Here are some places you can collect secondary research from:

- Your company’s internal data, which may include information contained in your company’s files, databases and project reports.

- Client’s research department, e.g. the data your client has regarding user behavior with previous versions of the website/application, user interests, etc.

- Industry statistics, i.e. the industry’s general consensus, standards and conventions.

- Relevant books, articles, case studies and magazines.

Websites have evolved a great deal over the last two decades, and so has the way users interact with them. This is why one of the most common challenges with secondary research in UI/UX design is outdated data. In such cases, UI/UX designers resort to other research methods (such as primary research or exploratory research) to gather the data they need.

Exploratory research

Exploratory research is usually conducted at the start of the design process with a purpose to help designers understand the problem they’re trying to solve. As such, it focuses on gathering a thorough understanding of the end user’s needs and goals.

In the Define the Problem stage of the design thinking process , you can use exploratory research techniques to develop a design hypothesis and validate it with the product’s intended user base. By doing so, you’ll be in a better position to make hypothesis-driven design decisions throughout the design process.

You can validate your hypothesis by running experiments. Here are some of the ways you can validate your assumptions depending on where you are in the design process:

- Conducting interviews and surveys

- Organizing focus groups

- Conducting usability tests

- Running various A/B tests

Essentially, you’re combining exploratory research and primary research techniques to define the problem accurately. You can do this by asking questions that encourage interview participants to explore different design concepts and think outside the box.

Before you begin collecting data, remember to write down the experiment you’re running and define the outcomes that validate your design hypothesis. After doing exploratory research, you should have enough data to begin designing a solution.

Evaluative research

Exploratory research gives you enough data to begin designing a solution. Once you have a prototype on hand, you can use evaluative research to test that solution with real users. The goal of evaluative research is to help designers gather feedback that allows them to improve their product’s design.

There are two main functions of evaluative research: summative and formative .

- Summative evaluation is all about making a judgment regarding the efficacy of the product once it’s complete.

- Formative evaluation, on the other hand, focuses on evaluating the product and making improvements (i.e., detecting and eliminating usability problems) during the development process.

For example, you can conduct usability tests in which you ask test participants to use the product to perform a set of tasks. Keep in mind that the purpose of evaluative research is to gather feedback from users regarding your product’s design. In case you’re short on time or low on budget, you can choose to conduct usability studies that fit in your time and budget constraints (such as guerrilla usability testing ).

Deciding which research method to use depends on what data you’re trying to gather and where you are in the design process. The information you collect through your design research will enable you to make informed design decisions and create better user-centered products.

Let’s quickly recap the four types of research methods UI/UX designers can use in the design process:

- Primary research is used to generate data by conducting interviews, surveys, and usability tests and/or organizing focus group sessions.

- With secondary research, you’re able to use existing research material to validate your design ideas and support your primary research.

- Exploratory research is when you come up with a design hypothesis and run experiments to validate it.

- Once you have a prototype, you can use evaluative research to see if there’s any room for improvement.

Which of these research methods do you use in your design process and how? Let us know in the comments section below.

An adventure awaits...

- Full Name *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Business Email *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Primary and Secondary Research

You may be hearing and reading a lot about the terms “primary and secondary research.” Actually, they are fancy terms to describe very simple concepts. This video does a nice job of explaining the concepts.

So basically…

If you heard it from someone else , as “second-hand” information, it’s secondary research .

If you were the first person (the primary person) to discover something, then it’s primary research .

Secondary research is important because it allows you to catch up on what everyone else has already found and researched (hopefully thoroughly). After a literature review or other form of secondary research, you will be prepared to venture into the topic with confidence because you will know the existing knowledge on the topic.

Primary research is special because you are the first (or one of the few) people to study the phenomena. Considering design is always changing and the ways people react to it are seldom the same (depending on culture, time period, context, and many other factors), it’s very likely your research may be exploring uncharted territory.

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

Color Theory

What is color theory.

Color theory is the study of how colors work together and how they affect our emotions and perceptions. It's like a toolbox for artists, designers, and creators to help them choose the right colors for their projects. Color theory enables you to pick colors that go well together and convey the right mood or message in your work.

- Transcript loading…

Color is in the Beholders’ Eyes

“Color! What a deep and mysterious language, the language of dreams.” — Paul Gauguin, Famous post-Impressionist painter

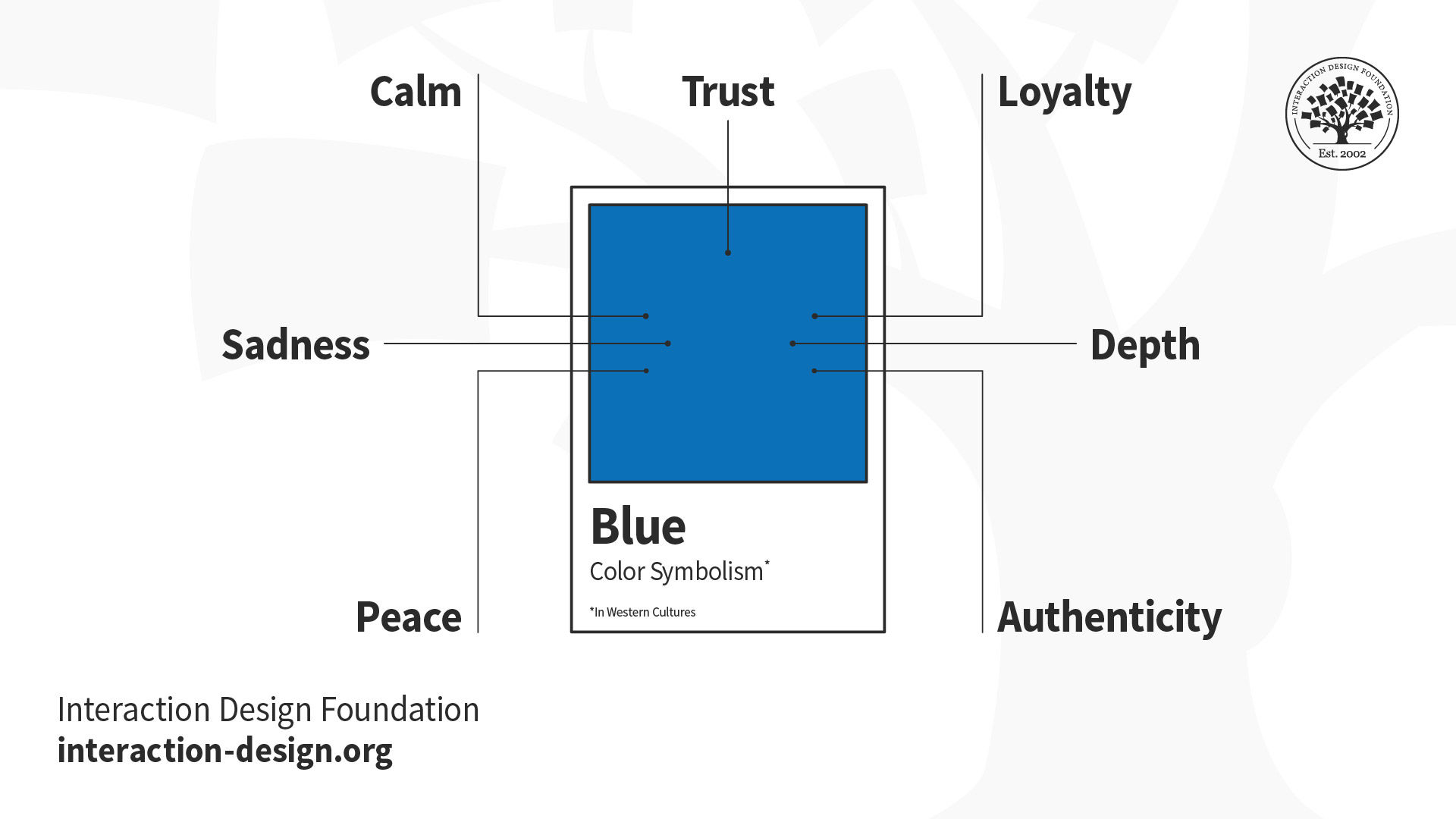

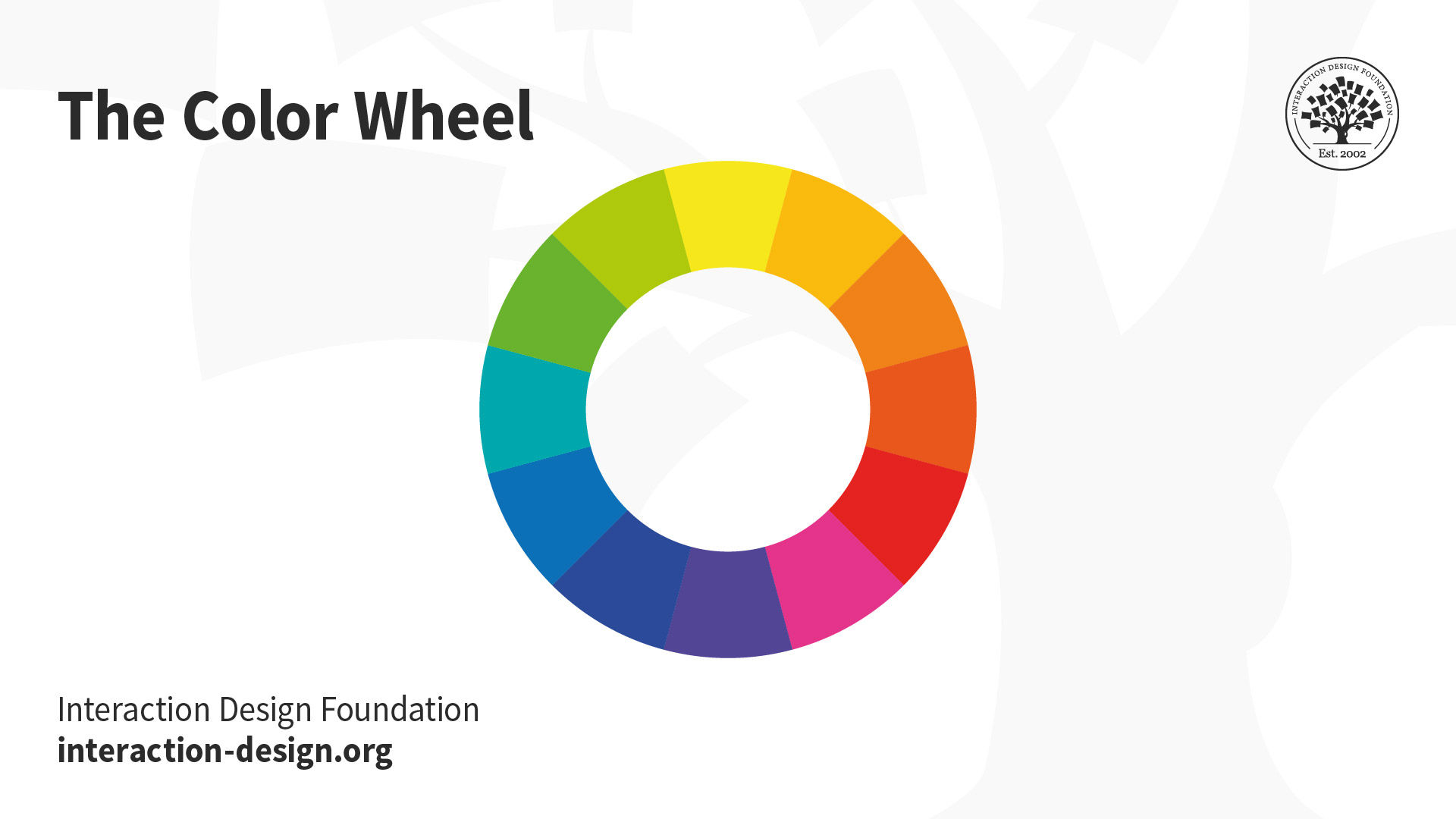

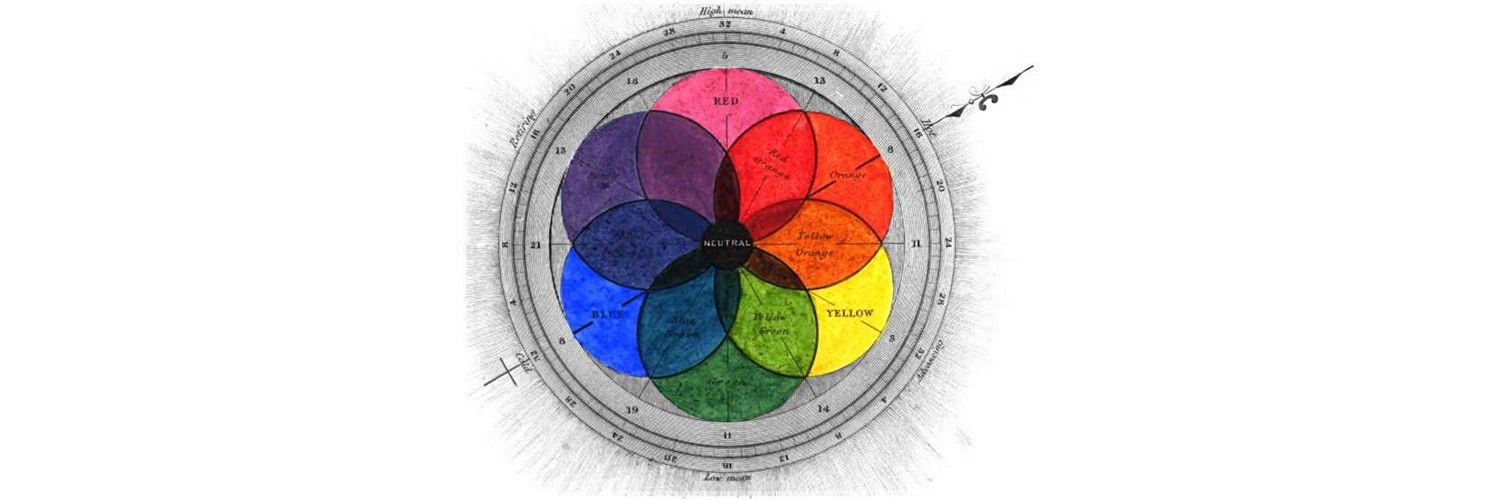

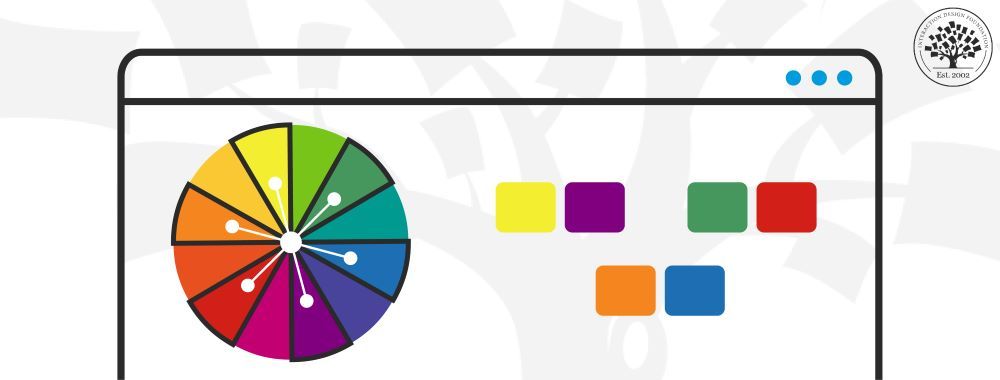

Sir Isaac Newton established color theory when he invented the color wheel in 1666. Newton understood colors as human perceptions —not absolute qualities—of wavelengths of light . By systematically categorizing colors, he defined three groups:

Primary (red, blue, yellow).

Secondary (mixes of primary colors).

Tertiary (or intermediate —mixes of primary and secondary colors).

What Are Hue, Value and Saturation?

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

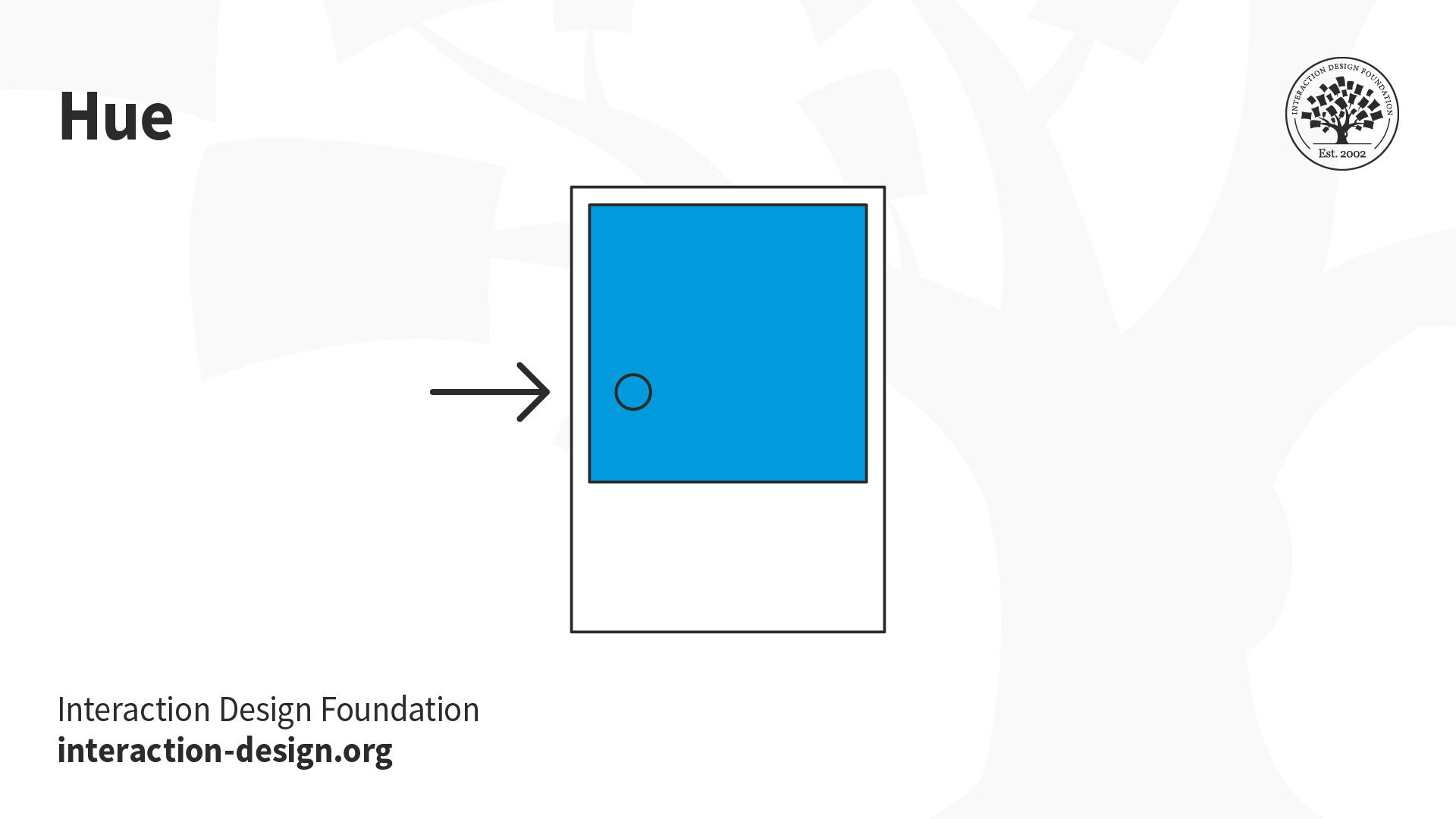

Hue is the attribute of color that distinguishes it as red, blue, green or any other specific color on the color wheel.

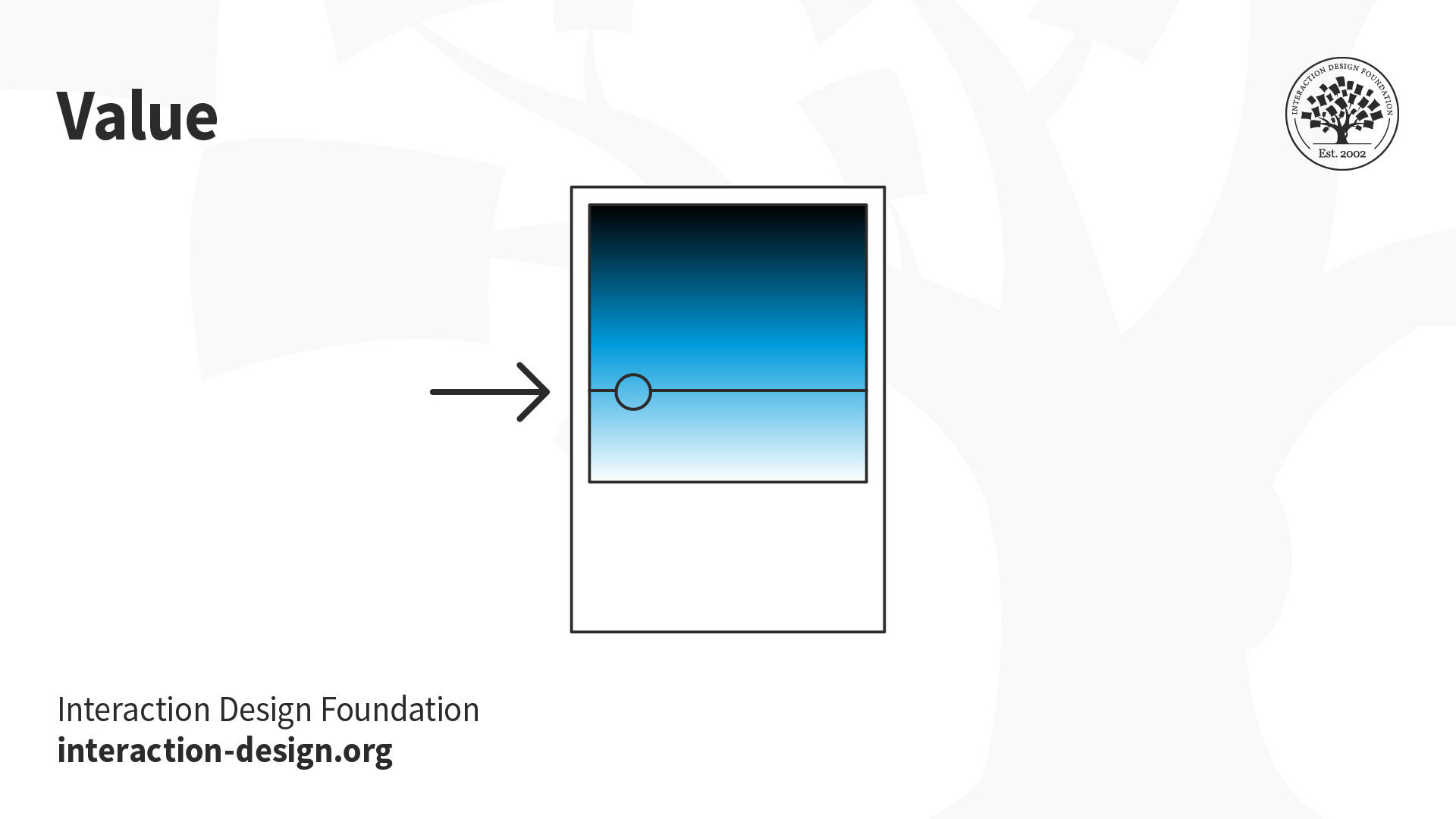

Value represents a color's relative lightness or darkness or grayscale and it’s crucial for creating contrast and depth in visual art.

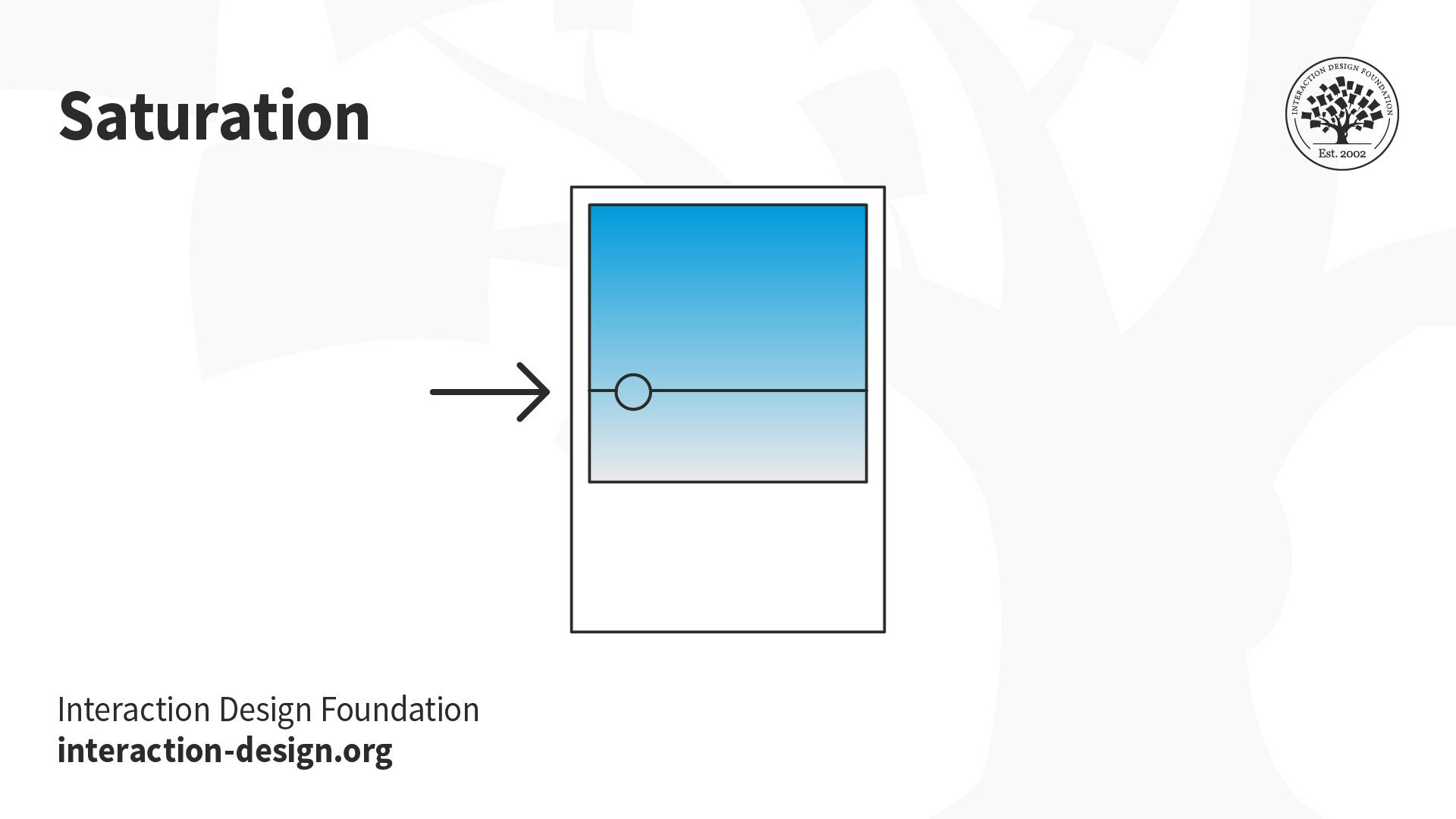

Saturation , also known as chroma or intensity, refers to the purity and vividness of a color, ranging from fully saturated (vibrant) to desaturated (grayed).

In user experience (UX) design , you need a firm grasp of color theory to craft harmonious, meaningful designs for your users.

Use a Color Scheme and Color Temperature for Design Harmony

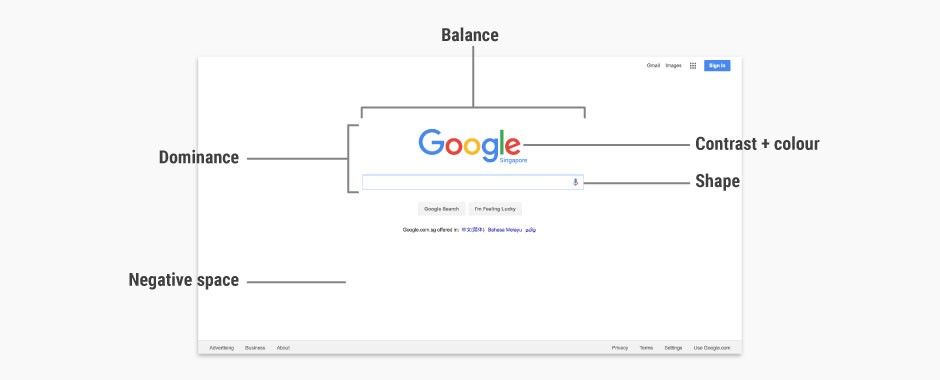

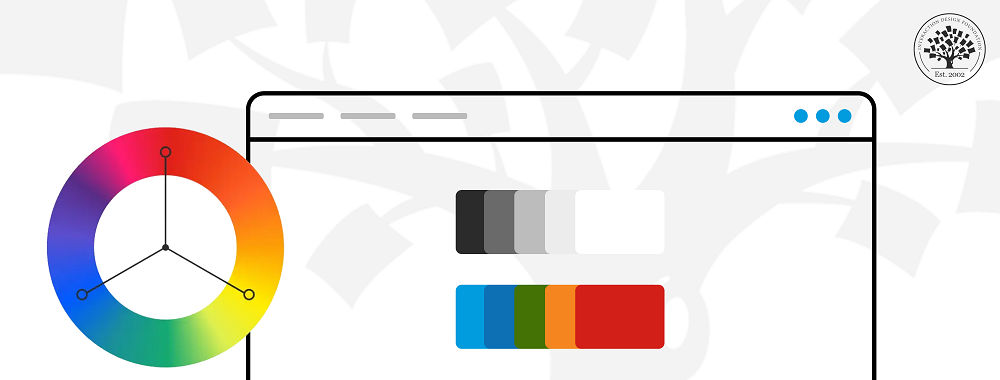

In screen design, designers use the additive color model , where red, green and blue are the primary colors. Just as you need to place images and other elements in visual design strategically, your color choices should optimize your users’ experience in attractive interfaces with high usability . When starting your design process, you can consider using any of these main color schemes:

Monochromatic : Take one hue and create other elements from different shades and tints of it.

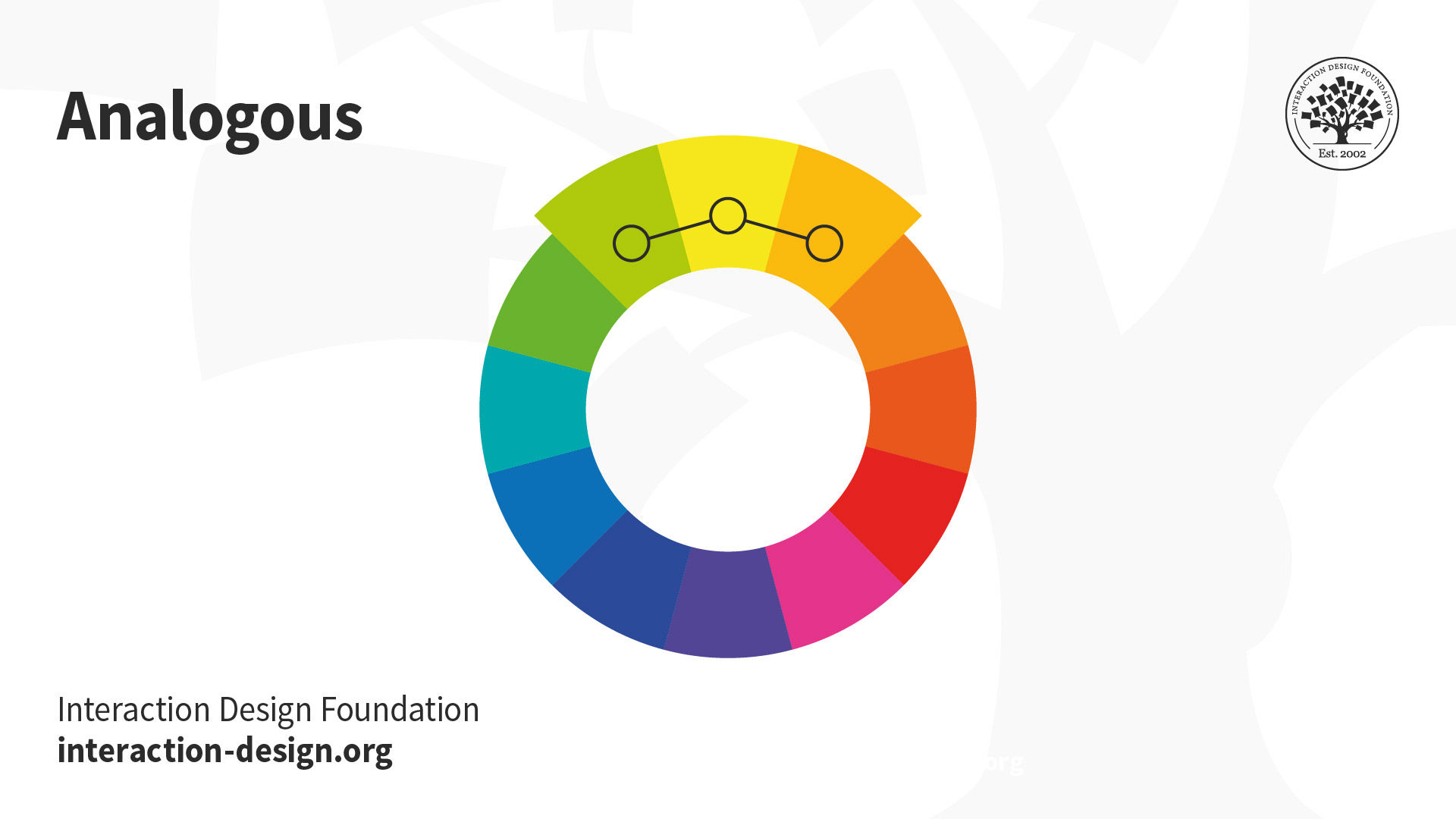

Analogous : Use three colors located beside one another on the color wheel (e.g., orange, yellow-orange and yellow to show sunlight). A variant is to mix white with these to form a “high-key” analogous color scheme (e.g., flames).

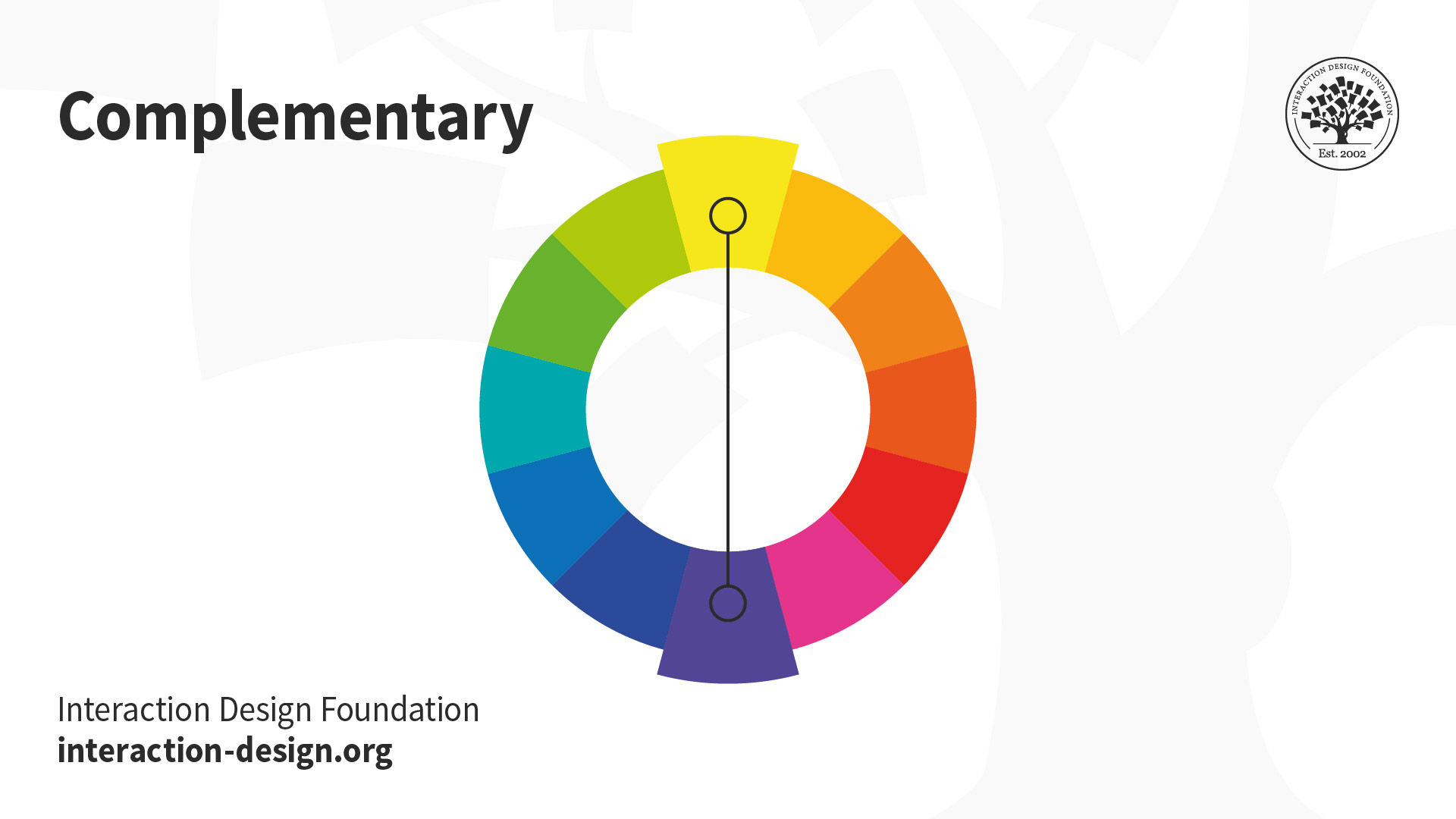

Complementary : Use “opposite color” pairs—e.g., blue/yellow—to maximize contrast.

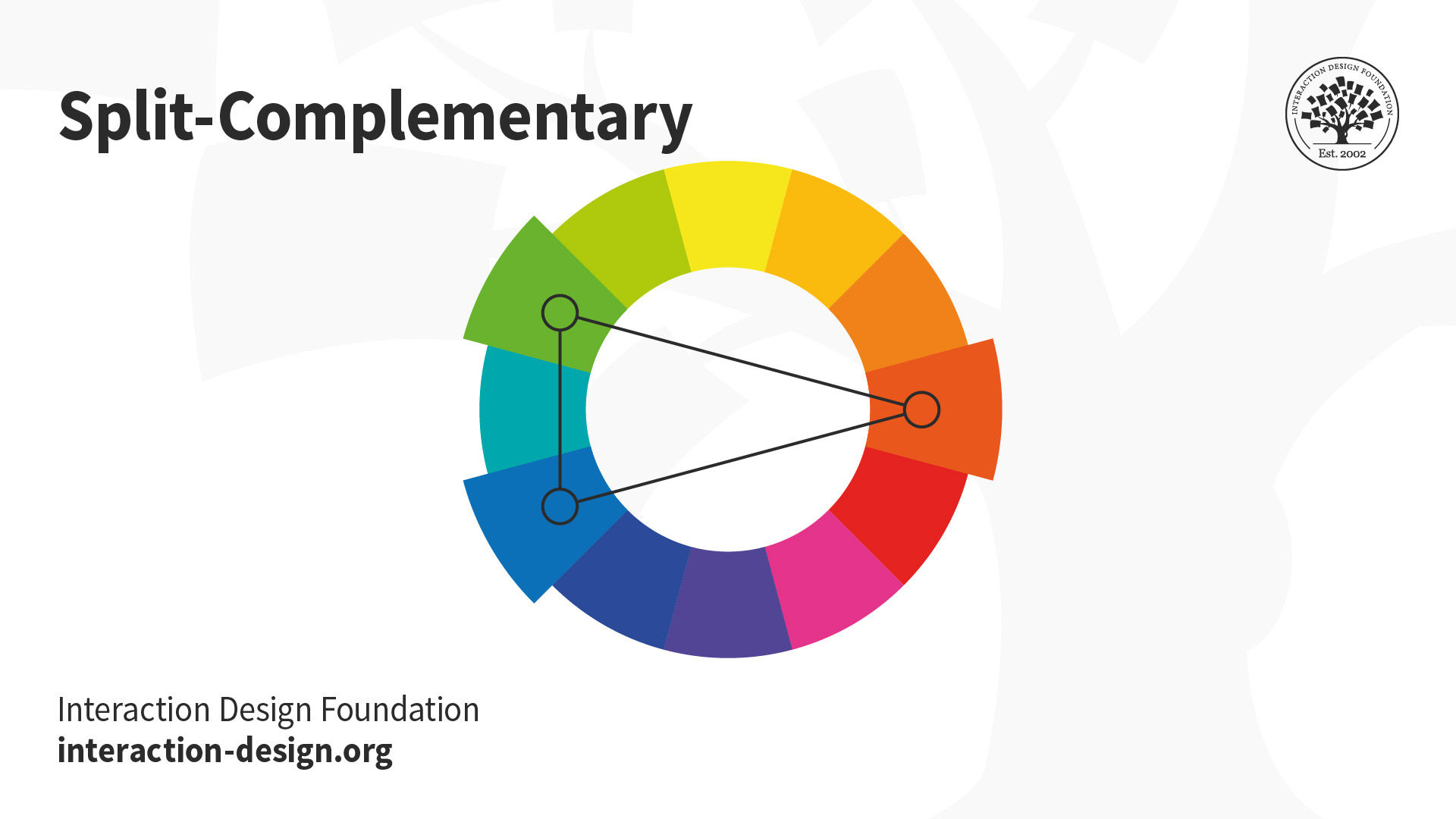

Split-Complementary (or Compound Harmony ): Add colors from either side of your complementary color pair to soften the contrast.

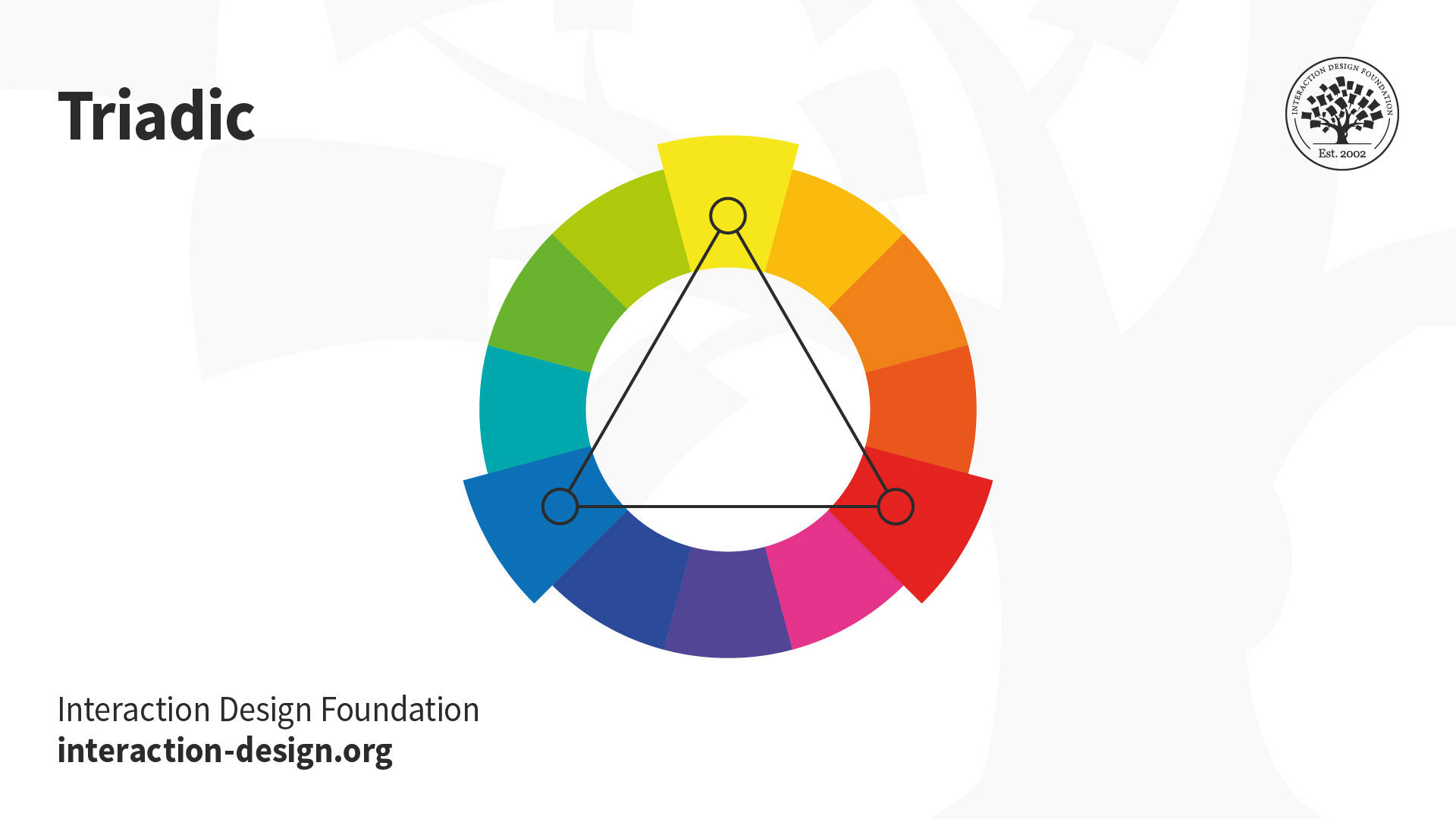

Triadic : Take three equally distant colors on the color wheel (i.e., 120° apart: e.g., red/blue/yellow). These colors may not be vibrant, but the scheme can be as it maintains harmony and high contrast. It’s easier to make visually appealing designs with this scheme than with a complementary scheme.

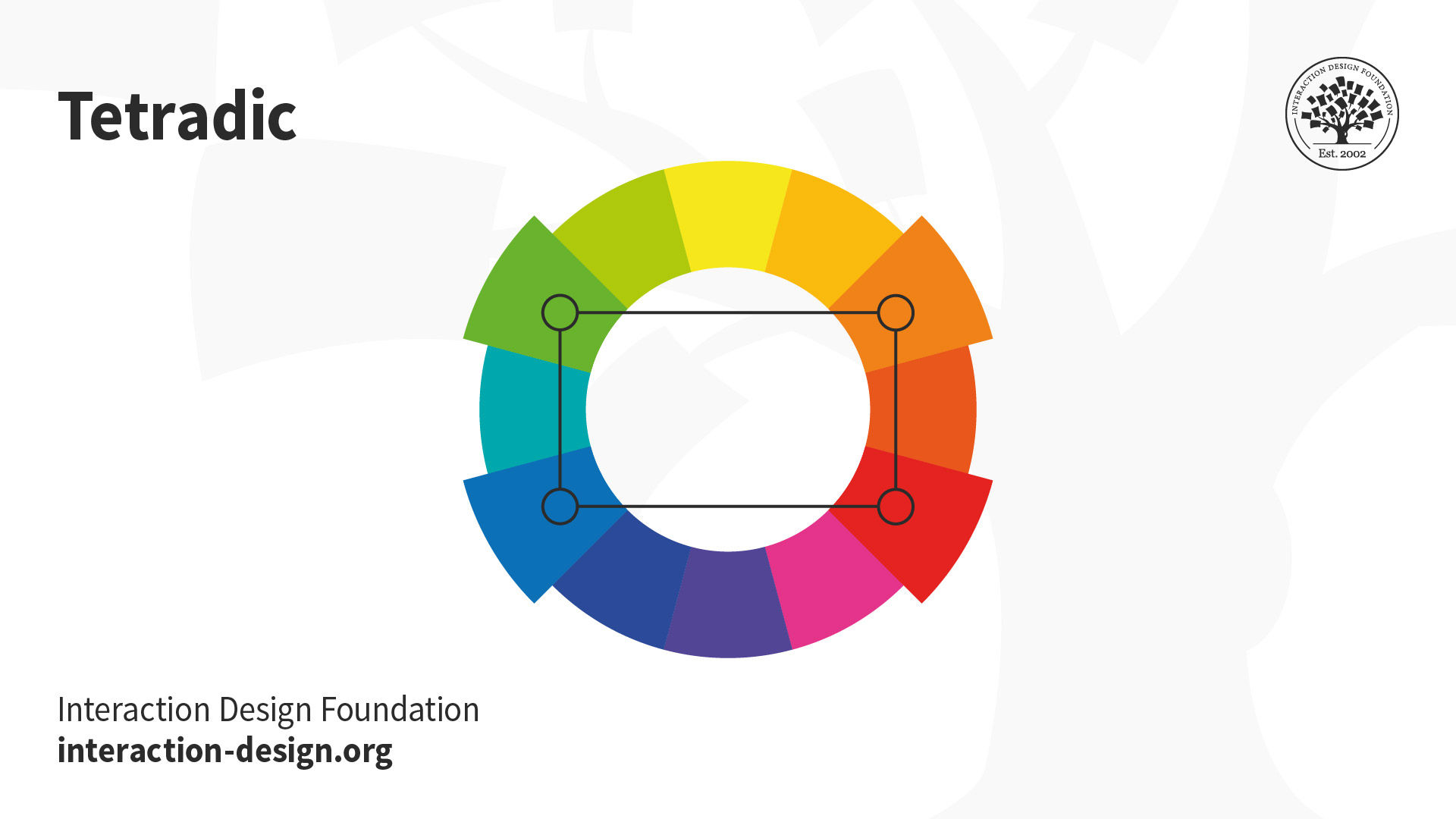

Tetradic : Take four colors that are two sets of complementary pairs (e.g., orange/yellow/blue/violet) and choose one dominant color. This allows rich, interesting designs. However, watch the balance between warm and cool colors.

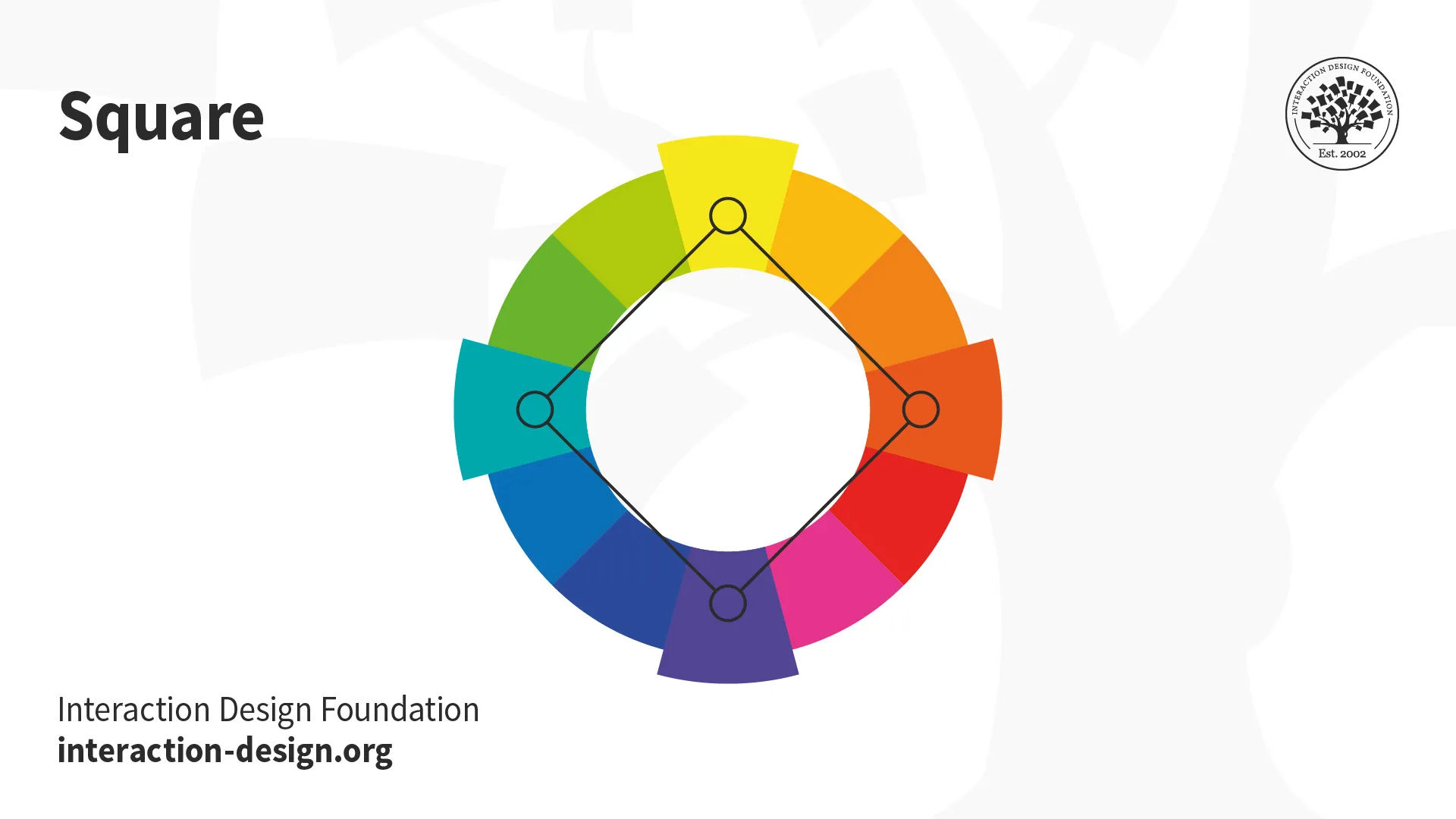

Square : A variant of tetradic; you find four colors evenly spaced on the color wheel (i.e., 90° apart). Unlike tetradic, square schemes can work well if you use all four colors evenly.

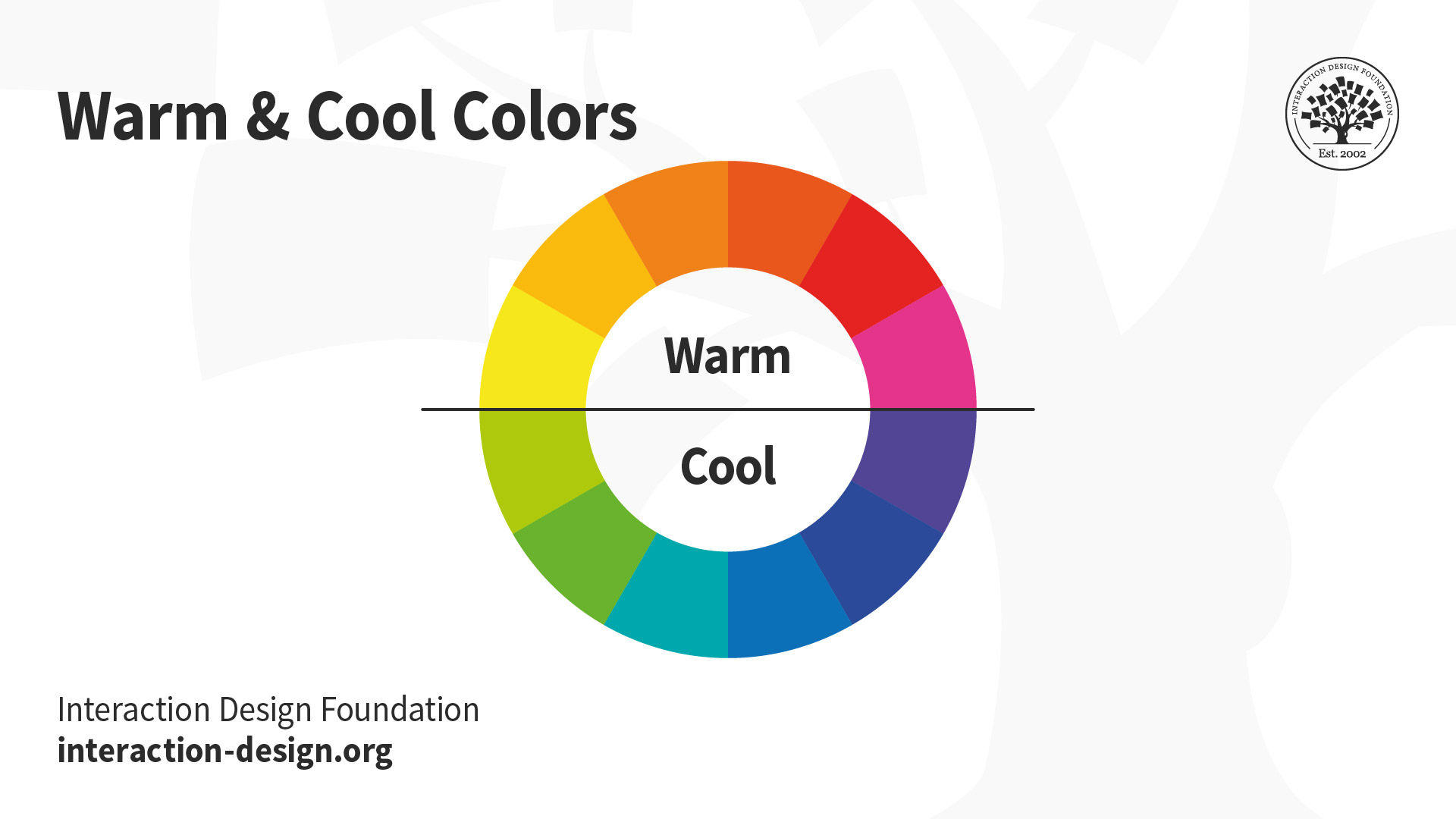

Your colors must reflect your design’s goal and the brand’s personality . You should also apply color theory to optimize a positive psychological impact on users . So, you should carefully determine how the color temperature (i.e., your use of warm, neutral and cool colors) reflects your message.

For example, you can make a neutral color such as grey warm or cool depending on factors such as your organization’s character and the industry.

Use Color Theory to Match What Your Users Want to See

The right contrast is vital to catching users’ attention in the first place. The vibrancy you choose for your design is likewise crucial to provoking desired emotional responses from users. How they react to color choices depends on factors such as gender, experience, age and culture. In all cases, you should design for accessibility —e.g., regarding red-green color blindness. You can fine-tune color choices through UX research to resonate best with specific users. Your users will encounter your design with their expectations of what a design in a certain industry should look like. That’s why you must also design to meet your market’s expectations geographically . For example, blue, an industry standard for banking in the West, has positive associations in other cultures.

However, some colors can evoke contradictory feelings from certain nationalities (e.g., red: good fortune in China, mourning in South Africa, danger/sexiness in the USA). Overall, you should use usability testing to confirm your color choices.

Learn More about Color Theory

Take our course Visual Design: The Ultimate Guide .

Register for the How To Use Color Theory To Enhance Your Designs Master Class webinar with color experts Arielle Eckstut and Joann Eckstut.

See designer and author Cameron Chapman’s in-depth piece for insights, tips and examples of color theory at work.

For more on concepts associated with color theory and color scheme examples, read Tubik Studio’s guide .

Questions related to Color Theory

As an artist, it's important to have a solid understanding of color theory. This framework allows you to explore how colors interact and can be combined to achieve specific effects or reactions. It involves studying hues, tints, tones, and shades, as well as the color wheel and classifications of primary, secondary, and tertiary colors.

The Color Wheel © Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Complementary and analogous colors are also important concepts to understand, as they can be used to create stunning color combinations. Additionally, color theory delves into the psychological effects of color, which can greatly impact the aesthetic and emotional impact of your art. By utilizing color theory, you can make informed decisions about color choices in your work and create art that truly resonates with your audience.

Color theory is a concept used in visual arts and design that explains how colors interact with each other and how they can be combined to create certain feelings, moods, and reactions. Arielle Eckstut, co-author of 'What Is Color? 50 Questions and Answers on the Science of Color,' explains that color does not exist outside of our perception, and different brains process visual information differently. Our retina, a part of the brain, plays a crucial role in color vision, and our brains constantly take in information from the outside world to inform us about our surroundings.

Watch this video for a deeper understanding of the science behind color:

To learn color theory, enroll in the ' Visual Design: The Ultimate Guide ' course on Interaction Design Foundation. This comprehensive course covers all aspects of visual design, including color theory. You will learn how colors interact with each other, how to combine them to create specific feelings and reactions, and how to use them effectively in your designs.

The course includes video lectures, articles, and interactive exercises that will help you master color theory and other key concepts of visual design. Start your journey to becoming a color theory expert by signing up for the course today !

Color theory helps us make sense of the world around us by providing a shorthand for using products, distinguishing objects, and interpreting information. For instance, colors can help us quickly identify pills in a bottle or different dosages.

Designers also consider cultural, personal, and biological influences on color perception to ensure the design communicates the right information. Ultimately, color helps us navigate the world safely, quickly, and with joy. Find out more about the significance of color in design by watching this video:

To use color theory effectively, consider the following tips from Joann Eckstut, co-author of 'What Is Color? 50 Questions and Answers on the Science of Color, in this video:

Understand the effect of light: Daylight constantly changes, affecting the colors we see. Changing the light source will change the color appearance of objects.

Consider the surroundings: Colors appear to change depending on the colors around them, a phenomenon known as simultaneous contrast.

Be aware of metamerism: Colors that match under one light source may not fit under another.

Remember that various factors such as light source and surrounding colors influence color, which is not a fixed entity. Being aware of these factors will prepare you to work effectively with color. Watch the full video for more insights and examples.

Color theory, as we know it today, is a culmination of ideas developed over centuries by various artists and scientists. However, one key figure in its development is Sir Isaac Newton, who, in 1666, discovered the color spectrum by passing sunlight through a prism. He then arranged these colors in a closed loop, creating the first color wheel. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe later expanded on this with his book "Theory of Colours" in 1810, exploring the psychological effects of colors.

Modern color theory has since evolved, incorporating principles from both Newton and Goethe, along with contributions from numerous other artists and researchers. To learn more about color theory, consider enrolling in the Visual Design - The Ultimate Guide course.

Understanding color theory might seem daunting at first, but it is manageable. Michal Malewicz emphasizes in the video below, that initially, a UX designer only needs three colors: a background color, a foreground (text) color, and an accent color.

It's advisable to start with fewer colors and gradually incorporate more as you become comfortable. Also, avoid color combinations like red mixed with saturated blue or green, and always test your colors for contrast and accessibility. Mastering color theory ultimately comes down to practice and observation. If it looks good, then it is good. For a comprehensive learning experience, consider enrolling in the Visual Design - The Ultimate Guide course on Interaction Design Foundation. Enroll now

Literature on Color Theory

Here’s the entire UX literature on Color Theory by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Learn more about Color Theory

Take a deep dive into Color Theory with our course Visual Design: The Ultimate Guide .

In this course, you will gain a holistic understanding of visual design and increase your knowledge of visual principles , color theory , typography , grid systems and history . You’ll also learn why visual design is so important, how history influences the present, and practical applications to improve your own work. These insights will help you to achieve the best possible user experience.

In the first lesson, you’ll learn the difference between visual design elements and visual design principles . You’ll also learn how to effectively use visual design elements and principles by deconstructing several well-known designs.

In the second lesson, you’ll learn about the science and importance of color . You’ll gain a better understanding of color modes, color schemes and color systems. You’ll also learn how to confidently use color by understanding its cultural symbolism and context of use.

In the third lesson, you’ll learn best practices for designing with type and how to effectively use type for communication . We’ll provide you with a basic understanding of the anatomy of type, type classifications, type styles and typographic terms. You’ll also learn practical tips for selecting a typeface, when to mix typefaces and how to talk type with fellow designers.

In the final lesson, you’ll learn about grid systems and their importance in providing structure within design . You’ll also learn about the types of grid systems and how to effectively use grids to improve your work.

You’ll be taught by some of the world’s leading experts . The experts we’ve handpicked for you are the Vignelli Distinguished Professor of Design Emeritus at RIT R. Roger Remington , author of “American Modernism: Graphic Design, 1920 to 1960”; Co-founder of The Book Doctors Arielle Eckstut and leading color consultant Joann Eckstut , co-authors of “What Is Color?” and “The Secret Language of Color”; Award-winning designer and educator Mia Cinelli , TEDx speaker of “The Power of Typography”; Betty Cooke and William O. Steinmetz Design Chair at MICA Ellen Lupton , author of “Thinking with Type”; Chair of the Graphic + Interactive communication department at the Ringling School of Art and Design Kimberly Elam , author of "Grid Systems: Principles of Organizing Type.”

Throughout the course, we’ll supply you with lots of templates and step-by-step guides so you can go right out and use what you learn in your everyday practice.

In the “ Build Your Portfolio Project: Redesign ,” you’ll find a series of fun exercises that build upon one another and cover the visual design topics discussed. If you want to complete these optional exercises, you will get hands-on experience with the methods you learn and in the process you’ll create a case study for your portfolio which you can show your future employer or freelance customers.

You can also learn with your fellow course-takers and use the discussion forums to get feedback and inspire other people who are learning alongside you. You and your fellow course-takers have a huge knowledge and experience base between you, so we think you should take advantage of it whenever possible.

You earn a verifiable and industry-trusted Course Certificate once you’ve completed the course. You can highlight it on your resume , your LinkedIn profile or your website .

All open-source articles on Color Theory

The key elements & principles of visual design.

- 1.1k shares

Recalling Color Theory Keywords: a way to refresh your memories!

- 3 years ago

Dressing Up Your UI with Colors That Fit

UI Color Palette 2024: Best Practices, Tips, and Tricks for Designers

Everything You Need To Know About Triadic Colors

Complementary Colors: The Ultimate Guide in 2024

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this page , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share the knowledge!

Share this content on:

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this page.

New to UX Design? We’re Giving You a Free ebook!

Download our free ebook The Basics of User Experience Design to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Another way to categorize information is by whether the information is in its original format or has been reinterpreted.

Another information category is publication mode and has to do with whether the information is

- Firsthand information (information in its original form, not translated or published in another form).

- Secondhand information (a restatement, analysis, or interpretation of original information).

- Third-hand information (a summary or repackaging of original information, often based on secondary information that has been published).

The three labels for information sources in this category are, respectively, primary sources, secondary sources, and tertiary sources.

When you make distinctions between primary, secondary, and tertiary sources, you are relating the information to the context in which it was created. Understanding this relationship is an important skill that you’ll need in college, as well as in the workplace. The relationship between creation and context helps us understand the “big picture” in which information operates and helps us figure out which information we can depend on. That’s a big part of thinking critically, a major benefit of actually becoming an educated person.

Primary Sources – Because it is in its original form, the information in primary sources has reached us from its creators without going through any filter. We get it firsthand. Here are some examples that are often used as primary sources:

- Any literary work, including novels, plays, and poems.

- Breaking news.

- Advertisements.

- Music and dance performances.

- Eyewitness accounts, including photographs and recorded interviews.

- Blog entries that are autobiographical.

- Scholarly blogs that provide data or are highly theoretical, even though they contain no autobiography.

- Artifacts such as tools, clothing, or other objects.

- Original documents such as tax returns, marriage licenses, and transcripts of trials.

- Websites, although many are secondary.

- Correspondence, including email.

- Records of organizations and government agencies.

- Journal articles that report research for the first time (at least the parts about the new research, plus their data).

Secondary Source – These sources are translated, repackaged, restated, analyzed, or interpreted original information that is a primary source. Thus, the information comes to us secondhand, or through at least one filter. Here are some examples that are often used as secondary sources:

- All nonfiction books and magazine articles except autobiography.

- An article or website that critiques a novel, play, painting, or piece of music.

- An article or web site that synthesizes expert opinion and several eyewitness accounts for a new understanding of an event.

- The literature review portion of a journal article.

Tertiary Source – These sources further repackage the original information because they index, condense, or summarize the original.

Typically, by the time tertiary sources are developed, there have been many secondary sources prepared on their subjects, and you can think of tertiary sources as information that comes to us “third-hand.” Tertiary sources are usually publications that you are not intended to read from cover to cover but to dip in and out of for the information you need. You can think of them as a good place for background information to start your research but a bad place to end up. Here are some examples that are often used as tertiary sources:

- Dictionaries.

- Guide books, including the one you are now reading.

- Survey articles.

- Bibliographies.

- Encyclopedias, including Wikipedia.

- Most textbooks.

Tertiary sources are usually not acceptable as cited sources in college research projects because they are so far from firsthand information. That’s why most professors don’t want you to use Wikipedia as a citable source: the information in Wikipedia is far from the original information. Other people have considered it, decided what they think about it, rearranged it, and summarized it–all of which is actually what your professors want you , not another author, to do with the information in your research projects.

The Details Are Tricky — A few things about primary or secondary sources might surprise you:

- Sources become primary rather than always exist as primary sources.

It’s easy to think that it is the format of primary sources that makes them primary. But that’s not all that matters. So when you see lists like the one above of sources that are often used as primary sources, it’s wise to remember that the ones listed are not automatically already primary sources. Firsthand sources get that designation only when researchers actually find their information relevant and use it.

For instance: Records that could be relevant to those studying government are created every day by federal, state, county, and city governments as they operate. But until those raw data are actually used by a researcher, they cannot be considered primary sources.

Another example: A diary about his flying missions kept by an American helicopter pilot in the Viet Nam War is not a primary source until, say, a researcher uses it in her study of how the war was carried out. But it will never be a primary source for a researcher studying the U.S. public’s reaction to the war because it does not contain information relevant to that study.

- Primary sources, even eyewitness accounts, are not necessarily accurate. Their accuracy has to be evaluated, just like that of all sources.

- Something that is usually considered a secondary source can be considered a primary source, depending on the research project.

For instance, movie reviews are usually considered secondary sources. But if your research project is about the effect movie reviews have on ticket sales, the movie reviews you study would become primary sources.

- Deciding whether to consider a journal article a primary or a secondary source can be complicated for at least two reasons.

First, journal articles that report new research for the first time are usually based on data. So some disciplines consider the data to be the primary source, and the journal article that describes and analyzes them is considered a secondary source.

However, particularly in the sciences, the original researcher might find it difficult or impossible (he or she might not be allowed) to share the data. So sometimes you have nothing more firsthand than the journal article, which argues for calling it the relevant primary source because it’s the closest thing that exists to the data.

Second, even journal articles that announce new research for the first time usually contain more than data. They also typically contain secondary source elements, such as a literature review, bibliography, and sections on data analysis and interpretation. So they can actually be a mix of primary and secondary elements. Even so, in some disciplines, a journal article that announces new research findings for the first time is considered to be, as a whole, a primary source for the researchers using it.

Under What Circumstances?

Consider the sources below and the potential circumstances under which each could become a primary source for you to use in your research.

Despite their trickiness, what primary sources usually offer is too good not to consider using because:

- They are original. This unfiltered, firsthand information is not available anywhere else.

- Their creator was a type of person unlike others in your research project, and you want to include that perspective.

- Their creator was present at an event and shares an eyewitness account.

- They are objects that existed at the particular time your project is studying.

Particularly in humanities courses, your professor may require you to use a certain number of primary sources for your project. In other courses, particularly in the sciences, you may be required to use only primary sources.

What sources are considered primary and secondary sources can vary from discipline to discipline. If you are required to use primary sources for your research project, before getting too deep into your project check with your professor to make sure he or she agrees with your choices. After all, it’s your professor who will be grading your project. A librarian, too, can verify your choices. Just remember to take a copy of your assignment with you when you ask because the librarian will want to see the original assignment. After all, that’s a primary source!

Critical Thinking in Academic Research Copyright © 2022 by Cindy Gruwell and Robin Ewing is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Clifton Fowler Library

- Subject Guide

Creation, Intelligent Design, & Evolution

- Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Sources

- Dictionaries and Encyclopedias

- Websites and Video Resources

- Writing Resources This link opens in a new window

- Philosophy & Theology Related Guides

- Science & Engineering Related Guides

This guide introduces you to resources for this subject area. The resources listed here are a small number of those available. For more information, contact a librarian at 303-963-3250, through Chat, or the Book a Librarian service.

Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Sources: definitions

When searching for information on a topic, it is important to understand the value of primary, secondary, and tertiary sources.

Primary sources allow researchers to get as close as possible to original ideas, events, and empirical research as possible. Such sources may include creative works, first hand or contemporary accounts of events, and the publication of the results of empirical observations or research.

Secondary sources analyze, review, or summarize information in primary resources or other secondary resources. Even sources presenting facts or descriptions about events are secondary unless they are based on direct participation or observation. Moreover, secondary sources often rely on other secondary sources and standard disciplinary methods to reach results, and they provide the principle sources of analysis about primary sources.

Tertiary sources provide overviews of topics by synthesizing information gathered from other resources. Tertiary resources often provide data in a convenient form or provide information with context by which to interpret it.

The distinctions between primary, secondary, and tertiary sources can be ambiguous. An individual document may be a primary source in one context and a secondary source in another. Encyclopedias are typically considered tertiary sources, but a study of how encyclopedias have changed on the Internet would use them as primary sources. Time is a defining element. While these definitions are clear, the lines begin to blur in the different discipline areas.

Hard Sciences

In the sciences, primary sources are documents that provide full description of the original research. For example, a primary source would be a journal article where scientists describe their research on the genetics of tobacco plants. A secondary source would be an article commenting or analyzing the scientists' research on tobacco.

Primary sources

- Conference proceedings

- Lab notebooks

- Technical reports

- Theses and dissertations

These are where the results of original research are usually first published in the sciences. This makes them the best source of information on cutting edge topics. However the new ideas presented may not be fully refined or validated yet.

Secondary sources

These tend to summarize the existing state of knowledge in a field at the time of publication. Secondary sources are good to find comparisons of different ideas and theories and to see how they may have changed over time.

Tertiary sources

- Compilations

- Dictionaries

- Encyclopedias

These types of sources present condensed material, generally with references back to the primary and/or secondary literature. They can be a good place to look up data or to get an overview of a subject, but they rarely contain original material.

Source for content provided by Virginia Tech Libraries, under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

Quick Links

Call us 303-963-3250

Text-a-Librarian 303-622-5333

- << Previous: Dictionaries and Encyclopedias

- Next: Websites and Video Resources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 5, 2024 1:16 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ccu.edu/creationidevo

Primary, Secondary & Tertiary Sources

What they are and how they compare (with examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Kerryn Warren (PhD) | January 2023

If you’re new to the wild world of research, you’re bound to encounter the terrible twins, “ primary source ” and “ secondary source ” sooner or later. With any luck, “ tertiary sources ” will get thrown into the mix too! In this post, we’ll unpack both what this terminology means and how to apply it to your research project.

Overview: Source Types

- Primary sources

- Examples of primary sources

- Pros and cons of primary data

- Secondary sources

- Examples of secondary sources

- Pros and cons of secondary data

- Tertiary sources

- Summary & recap

What are primary sources?

Simply put, primary sources (also referred to as primary data) are the original raw materials, evidence or data collected in a study. Primary sources can include interview transcripts, quantitative survey data, as well as other media that provide firsthand accounts of events or phenomena. Primary sources are often considered to be the purest sources because they provide direct, unfiltered data which has not been processed or interpreted in any way.

In addition to the above, examples of primary sources can include

- Results from a social media poll

- Letters written by a historical figure

- Photographs taken during a specific time period

- Government documents such as birth certificates and census records

- Artefacts like clothing and tools from past cultures

Naturally, working with primary data has both benefits and drawbacks. Some of the main advantages include

- Purity : primary sources provide firsthand accounts of events, ideas, and experiences, which means you get access to the rawest, purest form of data.

- Perspective : primary sources allow you to gain a deeper understanding of the perspectives of the people who created them, providing insights into how different groups of people viewed an event or phenomenon.

- Richness : primary data often provide a wealth of detail and nuance that can be missed in secondary data (we’ll cover that shortly). This can provide you with a more complete and nuanced understanding of their topic.

On the flip side, some of the main disadvantages include

- Bias : given their “rawness”, primary sources can often contain biases that can skew or limit your understanding of the issue at hand.

- Inaccessibility : sometimes, collecting fresh primary data can be difficult or even impossible. For example, photographs held in private collections or letters written in a language that you’re not fluent in.

- Fragility : physical artefacts such as manuscripts may be fragile and require special handling, which can make them difficult for you to access or study.

- Limited scope : primary sources often only provide a glimpse of a particular event, person, or period of time, so you may need to rely on multiple primary sources to gain a more complete understanding of a topic.

As you can see, the strengths and weaknesses of primary sources are oftentimes two sides of the same coin . For example, primary data allow you to gain insight into peoples’ unique perspectives, but at the same time, it bakes in a significant level of each participant’s personal bias. So, it’s important to carefully consider what your research aim is and whether it lends itself to this type of data source.

Now that you’ve got a clearer picture of what primary sources/data are, let’s take a look at secondary sources.

What are secondary sources?

Secondary sources are materials that provide an analysis or interpretation of primary sources (primary data). For example, secondary sources of information can include books, journal articles and documentaries . Unlike primary sources (which are raw and uninterpreted), secondary sources provide a distilled, interpreted view of the data.

Other examples of secondary sources include

- A book that provides an analysis of an event

- A biography of a pop icon

- An article that provides an interpretation of a public opinion poll

- A blog post that reviews and compares the performance of competing products

As with primary sources, secondary sources have their own set of pros and cons. Some of the main advantages include:

- Convenience: secondary sources are often easier to access and use than primary sources, as they are widely available in libraries, journal databases, etc.

- Interpretation and synthesis : secondary sources provide a synthesis of the topic of interest, which can help you to quickly understand the most important takeaways from a data set.

- Time-saving : secondary sources can save you time, as you don’t need to analyse primary sources yourself – you can just read summaries or interpretations provided by experts in the field.

At the same time, it’s important to be aware of the disadvantages of secondary sources. Some of the main ones to consider are

- Distance from original sources : secondary sources are based on primary data, but the information has been filtered through the lens of the author, which will naturally carry some level of bias and perhaps even a hidden agenda.

- Limited context: secondary sources may not provide the same level of contextual information or detail as primary sources, which can limit your understanding of the situation and contribute toward a warped understanding.

- Inaccuracies : since secondary sources are the product of human efforts, they may contain inaccuracies or errors, especially if the author has misinterpreted primary data.

- Outdated information : secondary sources may be based on primary sources that are no longer valid or accurate, or they may not take into account more recent research or discoveries.

It’s important to mention that primary and secondary data are not mutually exclusive . In other words, it doesn’t always need to be one or the other. Secondary sources can be used to supplement primary data by providing additional information or context for a particular topic.

For example, if you were researching Martin Luther King Jr., your primary source could be transcripts of the speeches he gave during the civil rights movement. To supplement this information, you could then use secondary sources such as biographies written about him or newspaper articles from the time period in which he was active.

So, once again, it’s important to think about what you’re trying to achieve with your research – that is to say, what are your research aims? As with all methodological choices, your decision to make use of primary or secondary data (or both), needs to be informed by your overall research aims .

Before we wrap up though, it’s important to look at one more source type – tertiary sources.

Need a helping hand?

What are tertiary sources?

Last but not least, we’ve got tertiary sources . Simply put, tertiary sources are materials that provide a general overview of a topic . They often summarise or synthesise information from a combination of primary and secondary sources, such as books, articles, and other documents.

Some examples of tertiary sources include

- Encyclopedias

- Study guides

- Dictionaries

Tertiary sources can be useful when you’re just starting to learn about a completely new topic , as they provide an overview of the subject matter without getting too in-depth into specific details. For example, if you’re researching the history of World War II, but don’t know much about it yet, reading an encyclopedia article (or Wikipedia article) on the war would be helpful in providing you with some basic facts and background information.

Tertiary sources are also useful in terms of providing a starting point for citations to primary and secondary source material which can help guide your search for more detailed, credible information on a particular topic. Additionally, these types of resources may also contain lists of related topics or keywords which you can use to find more information regarding your topic of interest.

Importantly, while tertiary sources are a valuable starting point for your research, they’re not ideal sources to cite in your dissertation, thesis or research project. Instead, you should aim to cite high-quality, credible secondary sources such as peer-reviewed journal articles and research papers . So, remember to only use tertiary sources as a starting point. Don’t make the classic mistake of citing Wikipedia as your main source!

Let’s recap

In this post, we’ve explored the trinity of sources: primary, secondary and tertiary.