The Research Problem & Statement

What they are & how to write them (with examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | March 2023

If you’re new to academic research, you’re bound to encounter the concept of a “ research problem ” or “ problem statement ” fairly early in your learning journey. Having a good research problem is essential, as it provides a foundation for developing high-quality research, from relatively small research papers to a full-length PhD dissertations and theses.

In this post, we’ll unpack what a research problem is and how it’s related to a problem statement . We’ll also share some examples and provide a step-by-step process you can follow to identify and evaluate study-worthy research problems for your own project.

Overview: Research Problem 101

What is a research problem.

- What is a problem statement?

Where do research problems come from?

- How to find a suitable research problem

- Key takeaways

A research problem is, at the simplest level, the core issue that a study will try to solve or (at least) examine. In other words, it’s an explicit declaration about the problem that your dissertation, thesis or research paper will address. More technically, it identifies the research gap that the study will attempt to fill (more on that later).

Let’s look at an example to make the research problem a little more tangible.

To justify a hypothetical study, you might argue that there’s currently a lack of research regarding the challenges experienced by first-generation college students when writing their dissertations [ PROBLEM ] . As a result, these students struggle to successfully complete their dissertations, leading to higher-than-average dropout rates [ CONSEQUENCE ]. Therefore, your study will aim to address this lack of research – i.e., this research problem [ SOLUTION ].

A research problem can be theoretical in nature, focusing on an area of academic research that is lacking in some way. Alternatively, a research problem can be more applied in nature, focused on finding a practical solution to an established problem within an industry or an organisation. In other words, theoretical research problems are motivated by the desire to grow the overall body of knowledge , while applied research problems are motivated by the need to find practical solutions to current real-world problems (such as the one in the example above).

As you can probably see, the research problem acts as the driving force behind any study , as it directly shapes the research aims, objectives and research questions , as well as the research approach. Therefore, it’s really important to develop a very clearly articulated research problem before you even start your research proposal . A vague research problem will lead to unfocused, potentially conflicting research aims, objectives and research questions .

What is a research problem statement?

As the name suggests, a problem statement (within a research context, at least) is an explicit statement that clearly and concisely articulates the specific research problem your study will address. While your research problem can span over multiple paragraphs, your problem statement should be brief , ideally no longer than one paragraph . Importantly, it must clearly state what the problem is (whether theoretical or practical in nature) and how the study will address it.

Here’s an example of a statement of the problem in a research context:

Rural communities across Ghana lack access to clean water, leading to high rates of waterborne illnesses and infant mortality. Despite this, there is little research investigating the effectiveness of community-led water supply projects within the Ghanaian context. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the effectiveness of such projects in improving access to clean water and reducing rates of waterborne illnesses in these communities.

As you can see, this problem statement clearly and concisely identifies the issue that needs to be addressed (i.e., a lack of research regarding the effectiveness of community-led water supply projects) and the research question that the study aims to answer (i.e., are community-led water supply projects effective in reducing waterborne illnesses?), all within one short paragraph.

Need a helping hand?

Wherever there is a lack of well-established and agreed-upon academic literature , there is an opportunity for research problems to arise, since there is a paucity of (credible) knowledge. In other words, research problems are derived from research gaps . These gaps can arise from various sources, including the emergence of new frontiers or new contexts, as well as disagreements within the existing research.

Let’s look at each of these scenarios:

New frontiers – new technologies, discoveries or breakthroughs can open up entirely new frontiers where there is very little existing research, thereby creating fresh research gaps. For example, as generative AI technology became accessible to the general public in 2023, the full implications and knock-on effects of this were (or perhaps, still are) largely unknown and therefore present multiple avenues for researchers to explore.

New contexts – very often, existing research tends to be concentrated on specific contexts and geographies. Therefore, even within well-studied fields, there is often a lack of research within niche contexts. For example, just because a study finds certain results within a western context doesn’t mean that it would necessarily find the same within an eastern context. If there’s reason to believe that results may vary across these geographies, a potential research gap emerges.

Disagreements – within many areas of existing research, there are (quite naturally) conflicting views between researchers, where each side presents strong points that pull in opposing directions. In such cases, it’s still somewhat uncertain as to which viewpoint (if any) is more accurate. As a result, there is room for further research in an attempt to “settle” the debate.

Of course, many other potential scenarios can give rise to research gaps, and consequently, research problems, but these common ones are a useful starting point. If you’re interested in research gaps, you can learn more here .

How to find a research problem

Given that research problems flow from research gaps , finding a strong research problem for your research project means that you’ll need to first identify a clear research gap. Below, we’ll present a four-step process to help you find and evaluate potential research problems.

If you’ve read our other articles about finding a research topic , you’ll find the process below very familiar as the research problem is the foundation of any study . In other words, finding a research problem is much the same as finding a research topic.

Step 1 – Identify your area of interest

Naturally, the starting point is to first identify a general area of interest . Chances are you already have something in mind, but if not, have a look at past dissertations and theses within your institution to get some inspiration. These present a goldmine of information as they’ll not only give you ideas for your own research, but they’ll also help you see exactly what the norms and expectations are for these types of projects.

At this stage, you don’t need to get super specific. The objective is simply to identify a couple of potential research areas that interest you. For example, if you’re undertaking research as part of a business degree, you may be interested in social media marketing strategies for small businesses, leadership strategies for multinational companies, etc.

Depending on the type of project you’re undertaking, there may also be restrictions or requirements regarding what topic areas you’re allowed to investigate, what type of methodology you can utilise, etc. So, be sure to first familiarise yourself with your institution’s specific requirements and keep these front of mind as you explore potential research ideas.

Step 2 – Review the literature and develop a shortlist

Once you’ve decided on an area that interests you, it’s time to sink your teeth into the literature . In other words, you’ll need to familiarise yourself with the existing research regarding your interest area. Google Scholar is a good starting point for this, as you can simply enter a few keywords and quickly get a feel for what’s out there. Keep an eye out for recent literature reviews and systematic review-type journal articles, as these will provide a good overview of the current state of research.

At this stage, you don’t need to read every journal article from start to finish . A good strategy is to pay attention to the abstract, intro and conclusion , as together these provide a snapshot of the key takeaways. As you work your way through the literature, keep an eye out for what’s missing – in other words, what questions does the current research not answer adequately (or at all)? Importantly, pay attention to the section titled “ further research is needed ”, typically found towards the very end of each journal article. This section will specifically outline potential research gaps that you can explore, based on the current state of knowledge (provided the article you’re looking at is recent).

Take the time to engage with the literature and develop a big-picture understanding of the current state of knowledge. Reviewing the literature takes time and is an iterative process , but it’s an essential part of the research process, so don’t cut corners at this stage.

As you work through the review process, take note of any potential research gaps that are of interest to you. From there, develop a shortlist of potential research gaps (and resultant research problems) – ideally 3 – 5 options that interest you.

Step 3 – Evaluate your potential options

Once you’ve developed your shortlist, you’ll need to evaluate your options to identify a winner. There are many potential evaluation criteria that you can use, but we’ll outline three common ones here: value, practicality and personal appeal.

Value – a good research problem needs to create value when successfully addressed. Ask yourself:

- Who will this study benefit (e.g., practitioners, researchers, academia)?

- How will it benefit them specifically?

- How much will it benefit them?

Practicality – a good research problem needs to be manageable in light of your resources. Ask yourself:

- What data will I need access to?

- What knowledge and skills will I need to undertake the analysis?

- What equipment or software will I need to process and/or analyse the data?

- How much time will I need?

- What costs might I incur?

Personal appeal – a research project is a commitment, so the research problem that you choose needs to be genuinely attractive and interesting to you. Ask yourself:

- How appealing is the prospect of solving this research problem (on a scale of 1 – 10)?

- Why, specifically, is it attractive (or unattractive) to me?

- Does the research align with my longer-term goals (e.g., career goals, educational path, etc)?

Depending on how many potential options you have, you may want to consider creating a spreadsheet where you numerically rate each of the options in terms of these criteria. Remember to also include any criteria specified by your institution . From there, tally up the numbers and pick a winner.

Step 4 – Craft your problem statement

Once you’ve selected your research problem, the final step is to craft a problem statement. Remember, your problem statement needs to be a concise outline of what the core issue is and how your study will address it. Aim to fit this within one paragraph – don’t waffle on. Have a look at the problem statement example we mentioned earlier if you need some inspiration.

Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- A research problem is an explanation of the issue that your study will try to solve. This explanation needs to highlight the problem , the consequence and the solution or response.

- A problem statement is a clear and concise summary of the research problem , typically contained within one paragraph.

- Research problems emerge from research gaps , which themselves can emerge from multiple potential sources, including new frontiers, new contexts or disagreements within the existing literature.

- To find a research problem, you need to first identify your area of interest , then review the literature and develop a shortlist, after which you’ll evaluate your options, select a winner and craft a problem statement .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

I APPRECIATE YOUR CONCISE AND MIND-CAPTIVATING INSIGHTS ON THE STATEMENT OF PROBLEMS. PLEASE I STILL NEED SOME SAMPLES RELATED TO SUICIDES.

Very pleased and appreciate clear information.

Your videos and information have been a life saver for me throughout my dissertation journey. I wish I’d discovered them sooner. Thank you!

Very interesting. Thank you. Please I need a PhD topic in climate change in relation to health.

Your posts have provided a clear, easy to understand, motivating literature, mainly when these topics tend to be considered “boring” in some careers.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Research Objectives | Examples & How To Write Them

Introduction

Why are research objectives important, characteristics of research objectives, what is an example of a research objective, types of research objectives, formulating research objectives.

Research objectives are clear, concise statements that outline what a research project aims to achieve. They guide the direction of the study, ensuring that researchers stay focused and organized. Properly formulated objectives help in identifying the scope of the research and the methods to be used. This article will cover the importance of research objectives, their characteristics, examples, types, and how to write them. By understanding these elements, researchers can develop effective research aims that enhance the clarity and purpose of their studies. This straightforward approach will provide practical guidance for both novice and experienced researchers in crafting clear research objectives.

Research objectives are crucial because they provide a clear focus and direction for a study. A well-defined research aim can help researchers stay on track by outlining specific goals that need to be achieved. This clarity ensures that all aspects of the research are aligned with the intended outcomes.

Having well-defined objectives also facilitates effective planning and execution. Researchers can allocate resources more efficiently, select appropriate methodologies , and set realistic timelines. Moreover, clear objectives help in the assessment and evaluation of the research process and its outcomes, making it easier to determine whether the study has been successful.

Research objectives also enhance communication. They allow researchers to clearly convey the purpose and scope of their study to stakeholders, including funding bodies, academic peers, and participants. This transparency builds credibility and trust, which are essential for the integrity of the research process.

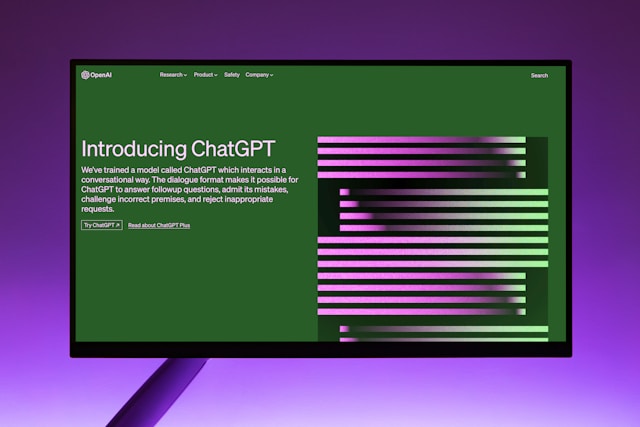

Research objectives possess several key characteristics that make them effective and useful for guiding a study. These characteristics ensure that the objectives are clear, achievable, and relevant to the research problem . Here are the essential characteristics to keep in mind when you develop research objectives for a successful research project.

- Specific : Research objectives focus on what the researcher intends to accomplish in a precise and unambiguous manner. Specific objectives break a research study into discrete and manageable tasks.

- Measurable : Objectives should include criteria for measuring progress and success. This characteristic allows researchers to track their progress and determine whether the objectives have been achieved.

- Achievable : Objectives need to be realistic and attainable within the constraints of the research project, including time, resources, and expertise. Setting achievable goals prevents frustration and ensures steady progress.

- Relevant : Objectives must be aligned with the research problem and the overall purpose of the study. They should contribute directly to addressing the study's research question or research hypothesis.

- Time-bound : Objectives should have a clear timeline for completion. This characteristic helps in planning and managing the research process, ensuring that objectives are met within a specified period.

- Clear and concise : Objectives should be articulated in a straightforward manner, avoiding complex language and jargon. Clarity helps in communicating the objectives to others involved in the research process.

- Focused : Each objective should target a specific aspect of the research problem. Having focused objectives prevents the study from becoming too broad and unmanageable.

- Logical : Objectives should follow a logical sequence that reflects the research process. This characteristic ensures that the objectives build on one another and collectively contribute to the overall research aim.

- Feasible : Consider the availability of resources, including data, equipment, and personnel, when formulating objectives. Feasibility ensures that the objectives can be realistically achieved with the available resources.

- Ethical : Objectives should respect ethical standards and guidelines . They should consider the well-being of participants, confidentiality , and integrity of the research process.

By adhering to these characteristics, researchers can develop objectives that are effective in guiding their study. Clear and well-defined objectives not only enhance the research process but also improve the quality and credibility of the research outcomes.

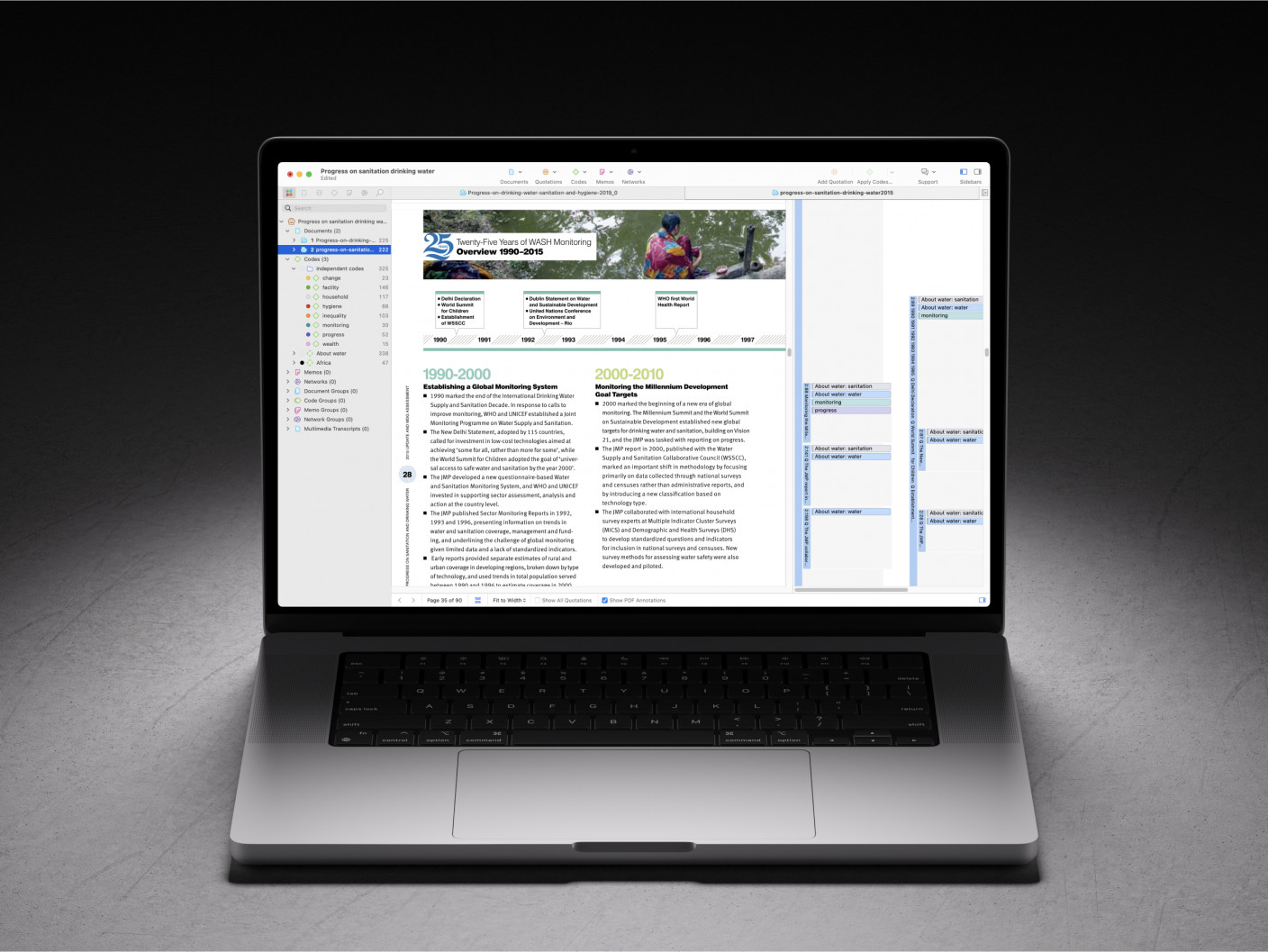

Scientific knowledge is easy to generate with ATLAS.ti

From collecting data to generating insights, do it all with ATLAS.ti. Get started with a free trial.

To illustrate what a well-defined research objective might look like, consider a study focused on improving reading comprehension among elementary school students. The research aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a new instructional strategy designed to enhance students' reading skills. Here is an example of a research objective for this study:

"To assess the impact of the interactive reading program on the reading comprehension scores of third-grade students over a six-month period."

This objective is effective because it meets several key criteria:

- Specific : The objective clearly states what will be assessed (the impact of the interactive reading program) and the target group (third-grade students).

- Measurable : The impact will be measured by changes in reading comprehension scores, providing a clear metric for evaluation.

- Achievable : The objective is realistic and attainable within a six-month period, assuming the necessary resources and support are available.

- Relevant : The objective is directly related to the study's research questions , which is to improve reading comprehension among elementary school students.

- Time-bound : The objective specifies a six-month period for the assessment, ensuring that the study is conducted within a defined timeframe.

By formulating objectives in this manner, researchers can create a clear roadmap for their study from research design to research paper . This example demonstrates how to incorporate the essential characteristics of research objectives into a practical and actionable statement.

Well-defined objectives help in planning the study, selecting an appropriate research methodology , and evaluating the outcomes. They also facilitate effective communication among members of the research team and with stakeholders, ensuring that everyone involved understands the purpose and scope of the research.

Research objectives can be categorized into different types based on their purpose and focus. Understanding these types helps researchers design studies that effectively address their research questions . Here are three common types of research objectives:

Descriptive objectives

Descriptive objectives aim to describe the characteristics or functions of a particular phenomenon or group. These objectives are often used in exploratory studies to gather information and provide a detailed picture of the subject being investigated. For example, a descriptive objective might be, "To describe the dietary habits of teenagers in urban areas." This type of objective helps in understanding the current state or conditions of the research subject.

Exploratory objectives

Exploratory objectives seek to explore new areas of knowledge or investigate relationships between variables. These objectives are often used in the initial stages of research to identify patterns, generate propositions, or uncover insights that can lead to further studies. An example of an exploratory objective is, "To investigate the relationship between social media usage and academic performance among college students." This type of objective is useful for studies that aim to look into new or under-researched areas.

Explanatory objectives

Explanatory objectives aim to explain the causes or reasons behind a particular phenomenon. These objectives often involve verifying a theory or determining relationships among variables. For instance, an explanatory objective could be, "To determine the impact of a structured exercise program on the mental health of elderly individuals." This type of objective is essential for studies that seek to understand the underlying mechanisms or effects of specific interventions or conditions.

Writing research aims is a critical step in the research process . Well-defined objectives provide a roadmap for the study and help ensure that the research stays focused and relevant. Here are some steps to guide the formulation of research objectives:

- Identify the research problem : Start by clearly defining the research problem or question you aim to address. Understanding the core issue helps in developing objectives that are directly related to the research focus.

- Conduct a literature review : Review existing research related to your topic to identify gaps in knowledge and areas that need further investigation. This background information can help in shaping specific and relevant objectives.

- Define the scope : Determine the scope of your study by considering factors such as the population, setting, and time frame. This will help in setting realistic and achievable objectives.

- Use the SMART criteria : Ensure that your objectives are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. This framework helps in creating clear and focused objectives that can guide the research process effectively.

- Break down the main objective : If your research has a broad aim, break it down into smaller, more specific sub-objectives. This makes the research more manageable and allows for a systematic approach to addressing the main research problem.

- Phrase objectives clearly : Write your objectives in clear and concise language, avoiding jargon and complex terms. Each objective should be easy to understand and communicate to others involved in the research.

- Align with research questions : Ensure that each objective aligns with your research question(s). The objectives should directly contribute to answering the key questions posed by your study.

- Seek feedback : Discuss your research objectives with peers, advisors, or experts in the field. Feedback can help refine the objectives and ensure that they are realistic and relevant.

Turn to ATLAS.ti for your research studies

Powerful data analysis with an intuitive interface is just a few clicks away. Download a free trial.

45 Research Problem Examples & Inspiration

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

A research problem is an issue of concern that is the catalyst for your research. It demonstrates why the research problem needs to take place in the first place.

Generally, you will write your research problem as a clear, concise, and focused statement that identifies an issue or gap in current knowledge that requires investigation.

The problem will likely also guide the direction and purpose of a study. Depending on the problem, you will identify a suitable methodology that will help address the problem and bring solutions to light.

Research Problem Examples

In the following examples, I’ll present some problems worth addressing, and some suggested theoretical frameworks and research methodologies that might fit with the study. Note, however, that these aren’t the only ways to approach the problems. Keep an open mind and consult with your dissertation supervisor!

Psychology Problems

1. Social Media and Self-Esteem: “How does prolonged exposure to social media platforms influence the self-esteem of adolescents?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Comparison Theory

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking adolescents’ social media usage and self-esteem measures over time, combined with qualitative interviews.

2. Sleep and Cognitive Performance: “How does sleep quality and duration impact cognitive performance in adults?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Psychology

- Methodology : Experimental design with controlled sleep conditions, followed by cognitive tests. Participant sleep patterns can also be monitored using actigraphy.

3. Childhood Trauma and Adult Relationships: “How does unresolved childhood trauma influence attachment styles and relationship dynamics in adulthood?

- Theoretical Framework : Attachment Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of attachment styles with qualitative in-depth interviews exploring past trauma and current relationship dynamics.

4. Mindfulness and Stress Reduction: “How effective is mindfulness meditation in reducing perceived stress and physiological markers of stress in working professionals?”

- Theoretical Framework : Humanist Psychology

- Methodology : Randomized controlled trial comparing a group practicing mindfulness meditation to a control group, measuring both self-reported stress and physiological markers (e.g., cortisol levels).

5. Implicit Bias and Decision Making: “To what extent do implicit biases influence decision-making processes in hiring practices?

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Dissonance Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design using Implicit Association Tests (IAT) to measure implicit biases, followed by simulated hiring tasks to observe decision-making behaviors.

6. Emotional Regulation and Academic Performance: “How does the ability to regulate emotions impact academic performance in college students?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Theory of Emotion

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys measuring emotional regulation strategies, combined with academic performance metrics (e.g., GPA).

7. Nature Exposure and Mental Well-being: “Does regular exposure to natural environments improve mental well-being and reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression?”

- Theoretical Framework : Biophilia Hypothesis

- Methodology : Longitudinal study comparing mental health measures of individuals with regular nature exposure to those without, possibly using ecological momentary assessment for real-time data collection.

8. Video Games and Cognitive Skills: “How do action video games influence cognitive skills such as attention, spatial reasoning, and problem-solving?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Load Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design with pre- and post-tests, comparing cognitive skills of participants before and after a period of action video game play.

9. Parenting Styles and Child Resilience: “How do different parenting styles influence the development of resilience in children facing adversities?”

- Theoretical Framework : Baumrind’s Parenting Styles Inventory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of resilience and parenting styles with qualitative interviews exploring children’s experiences and perceptions.

10. Memory and Aging: “How does the aging process impact episodic memory , and what strategies can mitigate age-related memory decline?

- Theoretical Framework : Information Processing Theory

- Methodology : Cross-sectional study comparing episodic memory performance across different age groups, combined with interventions like memory training or mnemonic strategies to assess potential improvements.

Education Problems

11. Equity and Access : “How do socioeconomic factors influence students’ access to quality education, and what interventions can bridge the gap?

- Theoretical Framework : Critical Pedagogy

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative data on student outcomes with qualitative interviews and focus groups with students, parents, and educators.

12. Digital Divide : How does the lack of access to technology and the internet affect remote learning outcomes, and how can this divide be addressed?

- Theoretical Framework : Social Construction of Technology Theory

- Methodology : Survey research to gather data on access to technology, followed by case studies in selected areas.

13. Teacher Efficacy : “What factors contribute to teacher self-efficacy, and how does it impact student achievement?”

- Theoretical Framework : Bandura’s Self-Efficacy Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys to measure teacher self-efficacy, combined with qualitative interviews to explore factors affecting it.

14. Curriculum Relevance : “How can curricula be made more relevant to diverse student populations, incorporating cultural and local contexts?”

- Theoretical Framework : Sociocultural Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of curricula, combined with focus groups with students and teachers.

15. Special Education : “What are the most effective instructional strategies for students with specific learning disabilities?

- Theoretical Framework : Social Learning Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing different instructional strategies, with pre- and post-tests to measure student achievement.

16. Dropout Rates : “What factors contribute to high school dropout rates, and what interventions can help retain students?”

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking students over time, combined with interviews with dropouts.

17. Bilingual Education : “How does bilingual education impact cognitive development and academic achievement?

- Methodology : Comparative study of students in bilingual vs. monolingual programs, using standardized tests and qualitative interviews.

18. Classroom Management: “What reward strategies are most effective in managing diverse classrooms and promoting a positive learning environment?

- Theoretical Framework : Behaviorism (e.g., Skinner’s Operant Conditioning)

- Methodology : Observational research in classrooms , combined with teacher interviews.

19. Standardized Testing : “How do standardized tests affect student motivation, learning, and curriculum design?”

- Theoretical Framework : Critical Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative analysis of test scores and student outcomes, combined with qualitative interviews with educators and students.

20. STEM Education : “What methods can be employed to increase interest and proficiency in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields among underrepresented student groups?”

- Theoretical Framework : Constructivist Learning Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing different instructional methods, with pre- and post-tests.

21. Social-Emotional Learning : “How can social-emotional learning be effectively integrated into the curriculum, and what are its impacts on student well-being and academic outcomes?”

- Theoretical Framework : Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of student well-being with qualitative interviews.

22. Parental Involvement : “How does parental involvement influence student achievement, and what strategies can schools use to increase it?”

- Theoretical Framework : Reggio Emilia’s Model (Community Engagement Focus)

- Methodology : Survey research with parents and teachers, combined with case studies in selected schools.

23. Early Childhood Education : “What are the long-term impacts of quality early childhood education on academic and life outcomes?”

- Theoretical Framework : Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

- Methodology : Longitudinal study comparing students with and without early childhood education, combined with observational research.

24. Teacher Training and Professional Development : “How can teacher training programs be improved to address the evolving needs of the 21st-century classroom?”

- Theoretical Framework : Adult Learning Theory (Andragogy)

- Methodology : Pre- and post-assessments of teacher competencies, combined with focus groups.

25. Educational Technology : “How can technology be effectively integrated into the classroom to enhance learning, and what are the potential drawbacks or challenges?”

- Theoretical Framework : Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing classrooms with and without specific technologies, combined with teacher and student interviews.

Sociology Problems

26. Urbanization and Social Ties: “How does rapid urbanization impact the strength and nature of social ties in communities?”

- Theoretical Framework : Structural Functionalism

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative surveys on social ties with qualitative interviews in urbanizing areas.

27. Gender Roles in Modern Families: “How have traditional gender roles evolved in families with dual-income households?”

- Theoretical Framework : Gender Schema Theory

- Methodology : Qualitative interviews with dual-income families, combined with historical data analysis.

28. Social Media and Collective Behavior: “How does social media influence collective behaviors and the formation of social movements?”

- Theoretical Framework : Emergent Norm Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of social media platforms, combined with quantitative surveys on participation in social movements.

29. Education and Social Mobility: “To what extent does access to quality education influence social mobility in socioeconomically diverse settings?”

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking educational access and subsequent socioeconomic status, combined with qualitative interviews.

30. Religion and Social Cohesion: “How do religious beliefs and practices contribute to social cohesion in multicultural societies?”

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys on religious beliefs and perceptions of social cohesion, combined with ethnographic studies.

31. Consumer Culture and Identity Formation: “How does consumer culture influence individual identity formation and personal values?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Identity Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining content analysis of advertising with qualitative interviews on identity and values.

32. Migration and Cultural Assimilation: “How do migrants negotiate cultural assimilation and preservation of their original cultural identities in their host countries?”

- Theoretical Framework : Post-Structuralism

- Methodology : Qualitative interviews with migrants, combined with observational studies in multicultural communities.

33. Social Networks and Mental Health: “How do social networks, both online and offline, impact mental health and well-being?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Network Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys assessing social network characteristics and mental health metrics, combined with qualitative interviews.

34. Crime, Deviance, and Social Control: “How do societal norms and values shape definitions of crime and deviance, and how are these definitions enforced?”

- Theoretical Framework : Labeling Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of legal documents and media, combined with ethnographic studies in diverse communities.

35. Technology and Social Interaction: “How has the proliferation of digital technology influenced face-to-face social interactions and community building?”

- Theoretical Framework : Technological Determinism

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative surveys on technology use with qualitative observations of social interactions in various settings.

Nursing Problems

36. Patient Communication and Recovery: “How does effective nurse-patient communication influence patient recovery rates and overall satisfaction with care?”

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys assessing patient satisfaction and recovery metrics, combined with observational studies on nurse-patient interactions.

37. Stress Management in Nursing: “What are the primary sources of occupational stress for nurses, and how can they be effectively managed to prevent burnout?”

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of stress and burnout with qualitative interviews exploring personal experiences and coping mechanisms.

38. Hand Hygiene Compliance: “How effective are different interventions in improving hand hygiene compliance among nursing staff, and what are the barriers to consistent hand hygiene?”

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing hand hygiene rates before and after specific interventions, combined with focus groups to understand barriers.

39. Nurse-Patient Ratios and Patient Outcomes: “How do nurse-patient ratios impact patient outcomes, including recovery rates, complications, and hospital readmissions?”

- Methodology : Quantitative study analyzing patient outcomes in relation to staffing levels, possibly using retrospective chart reviews.

40. Continuing Education and Clinical Competence: “How does regular continuing education influence clinical competence and confidence among nurses?”

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking nurses’ clinical skills and confidence over time as they engage in continuing education, combined with patient outcome measures to assess potential impacts on care quality.

Communication Studies Problems

41. Media Representation and Public Perception: “How does media representation of minority groups influence public perceptions and biases?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cultivation Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of media representations combined with quantitative surveys assessing public perceptions and attitudes.

42. Digital Communication and Relationship Building: “How has the rise of digital communication platforms impacted the way individuals build and maintain personal relationships?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Penetration Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative surveys on digital communication habits with qualitative interviews exploring personal relationship dynamics.

43. Crisis Communication Effectiveness: “What strategies are most effective in managing public relations during organizational crises, and how do they influence public trust?”

- Theoretical Framework : Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT)

- Methodology : Case study analysis of past organizational crises, assessing communication strategies used and subsequent public trust metrics.

44. Nonverbal Cues in Virtual Communication: “How do nonverbal cues, such as facial expressions and gestures, influence message interpretation in virtual communication platforms?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Semiotics

- Methodology : Experimental design using video conferencing tools, analyzing participants’ interpretations of messages with varying nonverbal cues.

45. Influence of Social Media on Political Engagement: “How does exposure to political content on social media platforms influence individuals’ political engagement and activism?”

- Theoretical Framework : Uses and Gratifications Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys assessing social media habits and political engagement levels, combined with content analysis of political posts on popular platforms.

Before you Go: Tips and Tricks for Writing a Research Problem

This is an incredibly stressful time for research students. The research problem is going to lock you into a specific line of inquiry for the rest of your studies.

So, here’s what I tend to suggest to my students:

- Start with something you find intellectually stimulating – Too many students choose projects because they think it hasn’t been studies or they’ve found a research gap. Don’t over-estimate the importance of finding a research gap. There are gaps in every line of inquiry. For now, just find a topic you think you can really sink your teeth into and will enjoy learning about.

- Take 5 ideas to your supervisor – Approach your research supervisor, professor, lecturer, TA, our course leader with 5 research problem ideas and run each by them. The supervisor will have valuable insights that you didn’t consider that will help you narrow-down and refine your problem even more.

- Trust your supervisor – The supervisor-student relationship is often very strained and stressful. While of course this is your project, your supervisor knows the internal politics and conventions of academic research. The depth of knowledge about how to navigate academia and get you out the other end with your degree is invaluable. Don’t underestimate their advice.

I’ve got a full article on all my tips and tricks for doing research projects right here – I recommend reading it:

- 9 Tips on How to Choose a Dissertation Topic

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Research Problem

Definition:

Research problem is a specific and well-defined issue or question that a researcher seeks to investigate through research. It is the starting point of any research project, as it sets the direction, scope, and purpose of the study.

Types of Research Problems

Types of Research Problems are as follows:

Descriptive problems

These problems involve describing or documenting a particular phenomenon, event, or situation. For example, a researcher might investigate the demographics of a particular population, such as their age, gender, income, and education.

Exploratory problems

These problems are designed to explore a particular topic or issue in depth, often with the goal of generating new ideas or hypotheses. For example, a researcher might explore the factors that contribute to job satisfaction among employees in a particular industry.

Explanatory Problems

These problems seek to explain why a particular phenomenon or event occurs, and they typically involve testing hypotheses or theories. For example, a researcher might investigate the relationship between exercise and mental health, with the goal of determining whether exercise has a causal effect on mental health.

Predictive Problems

These problems involve making predictions or forecasts about future events or trends. For example, a researcher might investigate the factors that predict future success in a particular field or industry.

Evaluative Problems

These problems involve assessing the effectiveness of a particular intervention, program, or policy. For example, a researcher might evaluate the impact of a new teaching method on student learning outcomes.

How to Define a Research Problem

Defining a research problem involves identifying a specific question or issue that a researcher seeks to address through a research study. Here are the steps to follow when defining a research problem:

- Identify a broad research topic : Start by identifying a broad topic that you are interested in researching. This could be based on your personal interests, observations, or gaps in the existing literature.

- Conduct a literature review : Once you have identified a broad topic, conduct a thorough literature review to identify the current state of knowledge in the field. This will help you identify gaps or inconsistencies in the existing research that can be addressed through your study.

- Refine the research question: Based on the gaps or inconsistencies identified in the literature review, refine your research question to a specific, clear, and well-defined problem statement. Your research question should be feasible, relevant, and important to the field of study.

- Develop a hypothesis: Based on the research question, develop a hypothesis that states the expected relationship between variables.

- Define the scope and limitations: Clearly define the scope and limitations of your research problem. This will help you focus your study and ensure that your research objectives are achievable.

- Get feedback: Get feedback from your advisor or colleagues to ensure that your research problem is clear, feasible, and relevant to the field of study.

Components of a Research Problem

The components of a research problem typically include the following:

- Topic : The general subject or area of interest that the research will explore.

- Research Question : A clear and specific question that the research seeks to answer or investigate.

- Objective : A statement that describes the purpose of the research, what it aims to achieve, and the expected outcomes.

- Hypothesis : An educated guess or prediction about the relationship between variables, which is tested during the research.

- Variables : The factors or elements that are being studied, measured, or manipulated in the research.

- Methodology : The overall approach and methods that will be used to conduct the research.

- Scope and Limitations : A description of the boundaries and parameters of the research, including what will be included and excluded, and any potential constraints or limitations.

- Significance: A statement that explains the potential value or impact of the research, its contribution to the field of study, and how it will add to the existing knowledge.

Research Problem Examples

Following are some Research Problem Examples:

Research Problem Examples in Psychology are as follows:

- Exploring the impact of social media on adolescent mental health.

- Investigating the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for treating anxiety disorders.

- Studying the impact of prenatal stress on child development outcomes.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to addiction and relapse in substance abuse treatment.

- Examining the impact of personality traits on romantic relationships.

Research Problem Examples in Sociology are as follows:

- Investigating the relationship between social support and mental health outcomes in marginalized communities.

- Studying the impact of globalization on labor markets and employment opportunities.

- Analyzing the causes and consequences of gentrification in urban neighborhoods.

- Investigating the impact of family structure on social mobility and economic outcomes.

- Examining the effects of social capital on community development and resilience.

Research Problem Examples in Economics are as follows:

- Studying the effects of trade policies on economic growth and development.

- Analyzing the impact of automation and artificial intelligence on labor markets and employment opportunities.

- Investigating the factors that contribute to economic inequality and poverty.

- Examining the impact of fiscal and monetary policies on inflation and economic stability.

- Studying the relationship between education and economic outcomes, such as income and employment.

Political Science

Research Problem Examples in Political Science are as follows:

- Analyzing the causes and consequences of political polarization and partisan behavior.

- Investigating the impact of social movements on political change and policymaking.

- Studying the role of media and communication in shaping public opinion and political discourse.

- Examining the effectiveness of electoral systems in promoting democratic governance and representation.

- Investigating the impact of international organizations and agreements on global governance and security.

Environmental Science

Research Problem Examples in Environmental Science are as follows:

- Studying the impact of air pollution on human health and well-being.

- Investigating the effects of deforestation on climate change and biodiversity loss.

- Analyzing the impact of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems and food webs.

- Studying the relationship between urban development and ecological resilience.

- Examining the effectiveness of environmental policies and regulations in promoting sustainability and conservation.

Research Problem Examples in Education are as follows:

- Investigating the impact of teacher training and professional development on student learning outcomes.

- Studying the effectiveness of technology-enhanced learning in promoting student engagement and achievement.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to achievement gaps and educational inequality.

- Examining the impact of parental involvement on student motivation and achievement.

- Studying the effectiveness of alternative educational models, such as homeschooling and online learning.

Research Problem Examples in History are as follows:

- Analyzing the social and economic factors that contributed to the rise and fall of ancient civilizations.

- Investigating the impact of colonialism on indigenous societies and cultures.

- Studying the role of religion in shaping political and social movements throughout history.

- Analyzing the impact of the Industrial Revolution on economic and social structures.

- Examining the causes and consequences of global conflicts, such as World War I and II.

Research Problem Examples in Business are as follows:

- Studying the impact of corporate social responsibility on brand reputation and consumer behavior.

- Investigating the effectiveness of leadership development programs in improving organizational performance and employee satisfaction.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful entrepreneurship and small business development.

- Examining the impact of mergers and acquisitions on market competition and consumer welfare.

- Studying the effectiveness of marketing strategies and advertising campaigns in promoting brand awareness and sales.

Research Problem Example for Students

An Example of a Research Problem for Students could be:

“How does social media usage affect the academic performance of high school students?”

This research problem is specific, measurable, and relevant. It is specific because it focuses on a particular area of interest, which is the impact of social media on academic performance. It is measurable because the researcher can collect data on social media usage and academic performance to evaluate the relationship between the two variables. It is relevant because it addresses a current and important issue that affects high school students.

To conduct research on this problem, the researcher could use various methods, such as surveys, interviews, and statistical analysis of academic records. The results of the study could provide insights into the relationship between social media usage and academic performance, which could help educators and parents develop effective strategies for managing social media use among students.

Another example of a research problem for students:

“Does participation in extracurricular activities impact the academic performance of middle school students?”

This research problem is also specific, measurable, and relevant. It is specific because it focuses on a particular type of activity, extracurricular activities, and its impact on academic performance. It is measurable because the researcher can collect data on students’ participation in extracurricular activities and their academic performance to evaluate the relationship between the two variables. It is relevant because extracurricular activities are an essential part of the middle school experience, and their impact on academic performance is a topic of interest to educators and parents.

To conduct research on this problem, the researcher could use surveys, interviews, and academic records analysis. The results of the study could provide insights into the relationship between extracurricular activities and academic performance, which could help educators and parents make informed decisions about the types of activities that are most beneficial for middle school students.

Applications of Research Problem

Applications of Research Problem are as follows:

- Academic research: Research problems are used to guide academic research in various fields, including social sciences, natural sciences, humanities, and engineering. Researchers use research problems to identify gaps in knowledge, address theoretical or practical problems, and explore new areas of study.

- Business research : Research problems are used to guide business research, including market research, consumer behavior research, and organizational research. Researchers use research problems to identify business challenges, explore opportunities, and develop strategies for business growth and success.

- Healthcare research : Research problems are used to guide healthcare research, including medical research, clinical research, and health services research. Researchers use research problems to identify healthcare challenges, develop new treatments and interventions, and improve healthcare delivery and outcomes.

- Public policy research : Research problems are used to guide public policy research, including policy analysis, program evaluation, and policy development. Researchers use research problems to identify social issues, assess the effectiveness of existing policies and programs, and develop new policies and programs to address societal challenges.

- Environmental research : Research problems are used to guide environmental research, including environmental science, ecology, and environmental management. Researchers use research problems to identify environmental challenges, assess the impact of human activities on the environment, and develop sustainable solutions to protect the environment.

Purpose of Research Problems

The purpose of research problems is to identify an area of study that requires further investigation and to formulate a clear, concise and specific research question. A research problem defines the specific issue or problem that needs to be addressed and serves as the foundation for the research project.

Identifying a research problem is important because it helps to establish the direction of the research and sets the stage for the research design, methods, and analysis. It also ensures that the research is relevant and contributes to the existing body of knowledge in the field.

A well-formulated research problem should:

- Clearly define the specific issue or problem that needs to be investigated

- Be specific and narrow enough to be manageable in terms of time, resources, and scope

- Be relevant to the field of study and contribute to the existing body of knowledge

- Be feasible and realistic in terms of available data, resources, and research methods

- Be interesting and intellectually stimulating for the researcher and potential readers or audiences.

Characteristics of Research Problem

The characteristics of a research problem refer to the specific features that a problem must possess to qualify as a suitable research topic. Some of the key characteristics of a research problem are:

- Clarity : A research problem should be clearly defined and stated in a way that it is easily understood by the researcher and other readers. The problem should be specific, unambiguous, and easy to comprehend.

- Relevance : A research problem should be relevant to the field of study, and it should contribute to the existing body of knowledge. The problem should address a gap in knowledge, a theoretical or practical problem, or a real-world issue that requires further investigation.

- Feasibility : A research problem should be feasible in terms of the availability of data, resources, and research methods. It should be realistic and practical to conduct the study within the available time, budget, and resources.

- Novelty : A research problem should be novel or original in some way. It should represent a new or innovative perspective on an existing problem, or it should explore a new area of study or apply an existing theory to a new context.

- Importance : A research problem should be important or significant in terms of its potential impact on the field or society. It should have the potential to produce new knowledge, advance existing theories, or address a pressing societal issue.

- Manageability : A research problem should be manageable in terms of its scope and complexity. It should be specific enough to be investigated within the available time and resources, and it should be broad enough to provide meaningful results.

Advantages of Research Problem

The advantages of a well-defined research problem are as follows:

- Focus : A research problem provides a clear and focused direction for the research study. It ensures that the study stays on track and does not deviate from the research question.

- Clarity : A research problem provides clarity and specificity to the research question. It ensures that the research is not too broad or too narrow and that the research objectives are clearly defined.

- Relevance : A research problem ensures that the research study is relevant to the field of study and contributes to the existing body of knowledge. It addresses gaps in knowledge, theoretical or practical problems, or real-world issues that require further investigation.

- Feasibility : A research problem ensures that the research study is feasible in terms of the availability of data, resources, and research methods. It ensures that the research is realistic and practical to conduct within the available time, budget, and resources.

- Novelty : A research problem ensures that the research study is original and innovative. It represents a new or unique perspective on an existing problem, explores a new area of study, or applies an existing theory to a new context.

- Importance : A research problem ensures that the research study is important and significant in terms of its potential impact on the field or society. It has the potential to produce new knowledge, advance existing theories, or address a pressing societal issue.

- Rigor : A research problem ensures that the research study is rigorous and follows established research methods and practices. It ensures that the research is conducted in a systematic, objective, and unbiased manner.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Literature Review – Types Writing Guide and...

Research Contribution – Thesis Guide

Table of Contents – Types, Formats, Examples

Purpose of Research – Objectives and Applications

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Handy Tips To Write A Clear Research Objectives With Examples

Introduction.

Research objectives play a crucial role in any research study. They provide a clear direction and purpose for the research, guiding the researcher in their investigation. Understanding research objectives is essential for conducting a successful study and achieving meaningful results.

In this comprehensive review, we will delve into the definition of research objectives, exploring their characteristics, types, and examples. We will also discuss the relationship between research objectives and research questions , as well as provide insights into how to write effective research objectives. Additionally, we will examine the role of research objectives in research methodology and highlight the importance of them in a study. By the end of this review, you will have a comprehensive understanding of research objectives and their significance in the research process.

Definition of Research Objectives: What Are They?

A research objective is defined as a clear and concise statement that outlines the specific goals and aims of a research study. These objectives are designed to be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART), ensuring they provide a structured pathway to accomplishing the intended outcomes of the project. Each objective serves as a foundational element that summarizes the purpose of your study, guiding the research activities and helping to measure progress toward the study’s goals. Additionally, research objectives are integral components of the research framework , establishing a clear direction that aligns with the overall research questions and hypotheses. This alignment helps to ensure that the study remains focused and relevant, facilitating the systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Characteristics of Effective Research Objectives

Characteristics of research objectives include:

- Specific: Research objectives should be clear about the what, why, when, and how of the study.

- Measurable: Research objectives should identify the main variables of the study that can be measured or observed.

- Relevant: Research objectives should be relevant to the research topic and contribute to the overall understanding of the subject.

- Feasible: Research objectives should be achievable within the constraints of time, resources, and expertise available.

- Logical: Research objectives should follow a logical sequence and build upon each other to achieve the overall research goal.

- Observable: Research objectives should be observable or measurable in order to assess the progress and success of the research project.

- Unambiguous: Research objectives should be clear and unambiguous, leaving no room for interpretation or confusion.

- Measurable: Research objectives should be measurable, allowing for the collection of data and analysis of results.

By incorporating these characteristics into research objectives, researchers can ensure that their study is focused, achievable, and contributes to the body of knowledge in their field.

Types of Research Objectives

Research objective can be broadly classified into general and specific objectives. General objectives are broad statements that define the overall purpose of the research. They provide a broad direction for the study and help in setting the context. Specific objectives, on the other hand, are detailed objectives that describe what will be researched during the study. They are more focused and provide specific outcomes that the researcher aims to achieve. Specific objectives are derived from the general objectives and help in breaking down the research into smaller, manageable parts. The specific objectives should be clear, measurable, and achievable. They should be designed in a way that allows the researcher to answer the research questions and address the research problem.

In addition to general and specific objectives, research objective can also be categorized as descriptive or analytical objectives. Descriptive objectives focus on describing the characteristics or phenomena of a particular subject or population. They involve surveys, observations, and data collection to provide a detailed understanding of the subject. Analytical objectives, on the other hand, aim to analyze the relationships between variables or factors. They involve data analysis and interpretation to gain insights and draw conclusions.

Both descriptive and analytical objectives are important in research as they serve different purposes and contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the research topic.

Examples of Research Objectives

Here are some examples of research objectives in different fields:

1. Objective: To identify key characteristics and styles of Renaissance art.

This objective focuses on exploring the characteristics and styles of art during the Renaissance period. The research may involve analyzing various artworks, studying historical documents, and interviewing experts in the field.

2. Objective: To analyze modern art trends and their impact on society.

This objective aims to examine the current trends in modern art and understand how they influence society. The research may involve analyzing artworks, conducting surveys or interviews with artists and art enthusiasts, and studying the social and cultural implications of modern art.

3. Objective: To investigate the effects of exercise on mental health.

This objective focuses on studying the relationship between exercise and mental health. The research may involve conducting experiments or surveys to assess the impact of exercise on factors such as stress, anxiety, and depression.

4. Objective: To explore the factors influencing consumer purchasing decisions in the fashion industry.

This objective aims to understand the various factors that influence consumers’ purchasing decisions in the fashion industry. The research may involve conducting surveys, analyzing consumer behavior data, and studying the impact of marketing strategies on consumer choices.

5. Objective: To examine the effectiveness of a new drug in treating a specific medical condition.

This objective focuses on evaluating the effectiveness of a newly developed drug in treating a particular medical condition. The research may involve conducting clinical trials, analyzing patient data, and comparing the outcomes of the new drug with existing treatment options.

These examples demonstrate the diversity of research objectives across different disciplines. Each objective is specific, measurable, and achievable, providing a clear direction for the research study.

Aligning Research Objectives with Research Questions

Research objectives and research questions are essential components of a research project. Research objective describe what you intend your research project to accomplish. They summarize the approach and purpose of the project and provide a clear direction for the research. Research questions, on the other hand, are the starting point of any good research. They guide the overall direction of the research and help identify and focus on the research gaps .

The main difference between research questions and objectives is their form. Research questions are stated in a question form, while objectives are specific, measurable, and achievable goals that you aim to accomplish within a specified timeframe. Research questions are broad statements that provide a roadmap for the research, while objectives break down the research aim into smaller, actionable steps.

Research objectives and research questions work together to form the ‘golden thread’ of a research project. The research aim specifies what the study will answer, while the objectives and questions specify how the study will answer it. They provide a clear focus and scope for the research project, helping researchers stay on track and ensure that their study is meaningful and relevant.

When writing research objectives and questions, it is important to be clear, concise, and specific. Each objective or question should address a specific aspect of the research and contribute to the overall goal of the study. They should also be measurable, meaning that their achievement can be assessed and evaluated. Additionally, research objectives and questions should be achievable within the given timeframe and resources of the research project. By clearly defining the objectives and questions, researchers can effectively plan and execute their research, leading to valuable insights and contributions to the field.

Guidelines for Writing Clear Research Objectives

Writing research objective is a crucial step in any research project. The objectives provide a clear direction and purpose for the study, guiding the researcher in their data collection and analysis. Here are some tips on how to write effective research objective:

1. Be clear and specific

Research objective should be written in a clear and specific manner. Avoid vague or ambiguous language that can lead to confusion. Clearly state what you intend to achieve through your research.

2. Use action verbs

Start your research objective with action verbs that describe the desired outcome. Action verbs such as ‘investigate’, ‘analyze’, ‘compare’, ‘evaluate’, or ‘identify’ help to convey the purpose of the study.

3. Align with research questions or hypotheses

Ensure that your research objectives are aligned with your research questions or hypotheses. The objectives should address the main goals of your study and provide a framework for answering your research questions or testing your hypotheses.

4. Be realistic and achievable

Set research objectives that are realistic and achievable within the scope of your study. Consider the available resources, time constraints, and feasibility of your objectives. Unrealistic objectives can lead to frustration and hinder the progress of your research.

5. Consider the significance and relevance

Reflect on the significance and relevance of your research objectives. How will achieving these objectives contribute to the existing knowledge or address a gap in the literature? Ensure that your objectives have a clear purpose and value.

6. Seek feedback

It is beneficial to seek feedback on your research objectives from colleagues, mentors, or experts in your field. They can provide valuable insights and suggestions for improving the clarity and effectiveness of your objectives.

7. Revise and refine

Research objectives are not set in stone. As you progress in your research, you may need to revise and refine your objectives to align with new findings or changes in the research context. Regularly review and update your objectives to ensure they remain relevant and focused.

By following these tips, you can write research objectives that are clear, focused, and aligned with your research goals. Well-defined objectives will guide your research process and help you achieve meaningful outcomes.

The Role of Research Objectives in Research Methodology

Research objectives play a crucial role in the research methodology . In research methodology, research objectives are formulated based on the research questions or problem statement. These objectives help in defining the scope and focus of the study, ensuring that the research is conducted in a systematic and organized manner.

The research objectives in research methodology act as a roadmap for the research project. They help in identifying the key variables to be studied, determining the research design and methodology, and selecting the appropriate data collection methods .

Furthermore, research objectives in research methodology assist in evaluating the success of the study. By setting clear objectives, researchers can assess whether the desired outcomes have been achieved and determine the effectiveness of the research methods employed. It is important to note that research objectives in research methodology should be aligned with the overall research aim. They should address the specific aspects or components of the research aim and provide a framework for achieving the desired outcomes.

Understanding The Dynamic of Research Objectives in Your Study

The research objectives of a study play a crucial role in guiding the research process, ensuring that the study is focused, purposeful, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field. It is important to note that the research objectives may evolve or change as the study progresses. As new information is gathered and analyzed, the researcher may need to revise the objectives to ensure that they remain relevant and achievable.

In summary, research objectives are essential components in writing an effective research paper . They provide a roadmap for the research process, guiding the researcher in their investigation and helping to ensure that the study is purposeful and meaningful. By understanding and effectively utilizing research objectives, researchers can enhance the quality and impact of their research endeavors.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

How to Formulate Research Questions in a Research Proposal? Discover The No. 1 Easiest Template Here!

7 Easy Step-By-Step Guide of Using ChatGPT: The Best Literature Review Generator for Time-Saving Academic Research

Writing Engaging Introduction in Research Papers : 7 Tips and Tricks!

Understanding Comparative Frameworks: Their Importance, Components, Examples and 8 Best Practices

Revolutionizing Effective Thesis Writing for PhD Students Using Artificial Intelligence!

3 Types of Interviews in Qualitative Research: An Essential Research Instrument and Handy Tips to Conduct Them

Highlight Abstracts: An Ultimate Guide For Researchers!

Crafting Critical Abstracts: 11 Expert Strategies for Summarizing Research

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How to Write a Statement of the Problem in Research

Table of Contents

The problem statement is a foundation of academic research writing , providing a precise representation of an existing gap or issue in a particular field of study.

Crafting a sharp and focused problem statement lays the groundwork for your research project.

- It highlights the research's significance .

- Emphasizes its potential to influence the broader academic community.

- Represents the initial step for you to make a meaningful contribution to your discipline.

Therefore, in this article, we will discuss what is a statement of the problem in research and how to craft a compelling research problem statement.

What is a research problem statement?

A research problem statement is a concise, clear, and specific articulation of a gap in current knowledge that your research aims to bridge. It not only sets forth the scope and direction of your research but also establishes its relevance and significance.

Your problem statement in your research paper aims to:

- Define the gap : Clearly identify and articulate a specific gap or issue in the existing knowledge.

- Provide direction : Serve as a roadmap, guiding the course of your research and ensuring you remain focused.

- Establish relevance : Highlight the importance and significance of the problem in the context of your field or the broader world.

- Guide inquiry : Formulate the research questions or hypotheses you'll explore.

- Communicate intent : Succinctly convey the core purpose of your research to stakeholders, peers, and any audience.

- Set boundaries : Clearly define the scope of your research to ensure it's focused and achievable.

When should you write a problem statement in research?

Initiate your research by crafting a clear problem statement. This should be done before any data collection or analysis, serving as a foundational anchor that clearly identifies the specific issue you aim to address.

By establishing this early on, you shape the direction of your research, ensuring it targets a genuine knowledge gap.

Furthermore, an effective and a concise statement of the problem in research attracts collaborators, funders, and supporters, resonating with its clarity and purpose. Remember, as your research unfolds, the statement might evolve, reflecting new insights and staying pertinent.

But how do you distinguish between a well-crafted problem statement and one that falls short?

Effective vs. ineffective research problem statements