Undergraduate Announcement 2023 - 2024

General information, program offerings:, program offerings, goals for student learning.

The Department of Politics expects students to accomplish each of the following key learning goals by the time of graduation:

- Show command of the language of political science and politics in several of its subfields.

- Understand the methods commonly used in several of its subfields.

- Learn the material for one subfield at a level of expertise and practical application necessary to understand the scholarly discourse.

- Command a set of tools appropriate to conduct independent and original research in one subfield. These tools differ by subfield (see below).

- Understand the political, historical, institutional context pertaining to a particular topic of research sufficiently to conduct independent and original research in that subfield.

Prerequisites

Normally, students entering the department must have successfully completed at least two courses offered by the Department of Politics on a graded basis before the end of sophomore year. The first two courses taken in politics are considered prerequisites . Prerequisites may not be taken as pass/D/fail. Courses taken as prerequisites will be counted as departmentals and may be used to fulfill distribution requirements. It is strongly recommended that one or both of the prerequisites be at the 200 level.

In addition, on a case-by-case basis, the DUS will consider counting a course taught by a regular politics faculty in another department that is not cross-listed with politics for departmental credit. If appropriate, such a departmental course may be approved to count as a prerequisite, and toward the 3-2-1 requirement, under the discretion of the DUS.

Effective with the Class of 2025, only one of the two prerequisites may be an analytical course (e.g., POL 345). For example: (1) If a student has taken POL 345 and POL 346 as their first two politics courses, a third politics course will be required — one of which must not include a course that counts as meeting the department's analytical requirement (e.g., POL 250, POL 345, POL 347, etc.), OR (2) A student who has taken SOC 245/POL 245 and POL 345 as their first two politics courses will be required to take a third departmental in order to declare the major by the end of sophomore year.

Program of Study

Course selection.

Class of 2024 : By the end of senior year, all students in the department must complete no fewer than 10 departmental courses , of which two may be cognates. The two prerequisites as well as a course that satisfies the analytical requirement are included within the overall count of 10 departmentals. All departmentals must be taken on a graded basis — pass/D/fail is not allowed. Students must receive a passing grade in at least 10 of the courses that count as departmentals. Students must attain an overall average of C or higher in the 10 or more graded courses that count as departmentals . All departmentals factor into the honors calculation .

Class of 2025 and beyond : By the end of senior year, all students in the department must complete no fewer than 11 departmental courses , of which two may be cognates. The two prerequisites, the completion of POL 300 (see below), as well as a course that satisfies the analytical requirement are included within the overall count of 11 departmentals. Students must attain an overall average of C or higher in the 11 or more graded courses that count as departmentals . For a departmental to fulfill a requirement, it must be taken for a grade. All departmentals factor into the honors calculation .

Politics majors indicate a prospective primary field when they sign into the department in the spring of their sophomore year. Majors must take courses in at least three of the fields listed below — a minimum of three courses in their designated primary field, two courses in a secondary field and one course in a tertiary field. One of three courses in the primary field normally is a 200-level course. Prerequisites may be used to satisfy field distribution requirements. A course taken to satisfy the analytical requirement cannot be used to satisfy a field distribution requirement.

The department's website lists additional courses that will fulfill field requirements in a given year, including one-time-only courses. It also lists topics courses offered by other departments that have POL cross-listings and that therefore can be counted as departmental courses.

- Political Theory : The PT subfield focuses on the nature of justice, democracy, power and other key ideas, and encourages students to develop frameworks for thinking evaluatively about pressing issues of politics and public policy of the day. POL 210, 301, 302, 303, 304, 305, 306, 307, 308, 309, 313, 315, 316, 321, 403, 410, 411, 412, 413, 416.

- American Politics : The AP subfield focuses on the U.S. political system and includes the study of the development of the American system of governance, American political institutions, the attitudes and behaviors of U.S. residents and the relationship between institutions and people. POL 220, 314, 315, 316, 318, 320, 321, 322, 323, 324, 325, 327, 329, 330, 333, 343, 344, 349, 392, 420, 421, 422, 423.

- Comparative Politics : The CP subfield focuses on the similarities and differences in patterns of politics around the world with attention to what happens within states regarding representation, economic development, violence and effective government. POL 230, 349, 351, 352, 355, 356, 360, 362, 364, 366, 367, 374, 375, 378, 386, 430, 431, 432, 433, 434, 479.

- International Relations : The IR subfield focuses on the study of politics among nations and nonstate actors in world affairs, including subjects such as the causes of war, the role of international law and institutions, economic interdependence and cooperation to advance common goals for human rights and environmental protection. POL 240, 313, 380, 381, 385, 386, 388, 392, 393, 440, 441, 442, 443.

- Methods in Political Science (cannot be the primary field): These courses in formal and quantitative methods provide undergraduate students with analytical tools they can use to conduct rigorous social science research. POL 250, 345, 346, 347, 450.

Analytical Requirement

The department maintains a list of politics courses that have an emphasis on methodological tools for research in political science. Majors are required to take a course to fulfill the analytical requirement , normally no later than the first term of their junior year. The courses used to fulfill the analytical requirement cannot be used to fulfill primary, secondary or tertiary field requirements. The analytical requirement may be satisfied by POL 250, POL 345, POL 346, or POL 347. We will also accept ANT 301, ANT 302, ECO 202, ECO 302, ECO 312, ORF 245, PHI 201, SOC 404, or SPI 200.

Politics majors are required to complete POL 300 (Conducting Independent Research in Political Science) in the fall semester of junior year, beginning with the Class of 2025. POL 300 is designed to complement the fall junior independent work requirement and will count for course credit.

Upon course registration, students will need to select one of two tracks for the lecture component of POL 300. The technical track (L01) builds on preparation for political analysis offered by POL 345; it's open to juniors who completed POL 345 or equivalent courses (e.g., ECO 202, ORF 245) before junior year. The conceptual track (L02) has no prerequisites and doesn't presume fulfillment of the analytical requirement. Both tracks cover many of the same topics. L02 focuses less on underlying statistics than L01, and may be more appropriate for students interested in qualitative/historical/political theory work.

Cognates are courses offered in departments other than politics that have a substantial political content, which is defined as having at least 50% politics content. Unless approved for a special program (see below), students are permitted to count up to two cognates as departmental courses. The department maintains a list of all approved cognates for each student. A cognate must be approved by the last day of classes in the semester in which it is taken (except in spring semester of senior year, when the deadline is the second Friday of classes). With the exception of courses taken outside of politics that satisfy the analytical requirement, or upper-level courses taken in economics to fulfill the requirements of the track in political economy, courses taken in the first year or sophomore year cannot be approved as cognates. Cognate courses should not be at the introductory level. Cognates cannot be used to satisfy field distribution requirements. To seek approval for a cognate, students must complete the politics cognate approval application and email it along with a current syllabus to the cognate approval adviser for their review. Once a cognate has been approved, it may not be rescinded. Approved cognates must be taken for a grade and will be used in the departmental honors calculation.

Students who wish to combine the study of politics with the study of another discipline or a specific geographic area may design a special program that would allow them to count three cognates as departmentals. Politics and religion, politics and psychology, public policy and bioethics, and the politics of the Near East are examples of special plans of study. Individual areas of study must be approved by the department. Normally, a student must submit a written proposal to the cognate approval adviser by the end of the junior year. The proposal should demonstrate how the three cognates relate to one another and form a coherent interdisciplinary program.

Graduate Courses

Well-prepared undergraduates may take graduate seminars for full university and departmental credit. To enroll in a graduate seminar, the student must first obtain the signature approval of the instructor in charge, the DUS, and their residential college dean using this form .

Departmental Tracks

The Department of Politics offers four departmental tracks that provide more focused guidance to students who wish to address themes that bridge the subfields. Only students who declare their major in politics are eligible to pursue these tracks. Students should inform the undergraduate program manager of their intention to pursue a track during the sophomore declaration period, and no later than February 1 of their junior year. Students who select a track will still need to fulfill the requirements of a politics major. The tracks provide additional guidance for structuring the program of study as a politics major, but students are not required to select a track to graduate with a degree in politics. Courses may simultaneously fulfill both the track requirements and the politics major requirements. All courses taken to satisfy a track must be a on a graded basis and will factor into the honors calculation. ( Please note: The degree will read A.B. in politics and, unlike university certificates, the departmental track will not appear on the transcript. Majors who successfully complete the track’s requirements will receive a departmental attestation on Class Day .)

Track in American Ideas and Institutions

The Department of Politics, in collaboration with the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions, offers the track in American ideas and institutions (AIIP) for students who wish to further demonstrate their understandings of the three branches of the federal government and the values, ideas and theories that underlie them and are animated by their workings. It draws together a menu of courses from American politics, political theory, public law and other departmental offerings.

Requirements

A student in the track is required to complete five courses, one in each of the four topics listed below, as well as one more chosen from any one of the areas. No individual course number may be counted for more than one track requirement (even if, as in the case of POL 332 for example, the course may be taken by a student more than once as the topic changes annually).

- The Executive Branch: POL 325, POL 330, POL 331/HUM 305, POL 332 (when approved by the track adviser).

- The Legislative Branch: POL 324, POL 329.

- The Constitution and the Courts: POL 314, POL 315, POL 316, POL 318, POL 319/AMS 219/AAS 386, POL 320, POL 326, POL 339.

- American Political, Legal, and Constitutional Thought: SPI 370/POL 308/CHV 301, POL 314, POL 315, POL 316, POL 319/AMS 219/AAS 386, POL 321, POL 331/HUM 305, POL 332 (when approved by the track adviser), POL 488/HUM 488/AMS 488, POL 493, POL 494.

Senior Thesis

While a student in the track must write a thesis on a topic related to the student's primary field, the thesis must also incorporate significant content related to themes in one or more of the topic areas of the track. The student should meet with the AIIP adviser during the fall semester of senior year to confirm the suitability of their thesis topic. On or before the thesis draft deadline, the appropriate content of the thesis must be certified by the AIIP adviser.

Track in Political Economy

The Department of Politics offers the track in political economy (PE) for students who wish to further their understanding of social phenomena and individual behavior by combining the perspectives of its two constituent disciplines. The track allows and encourages students to use analytical tools from game theory, microeconomics and statistics to study political behavior, and to incorporate a thorough analysis of politics and collective decision-making into economic analysis.

To participate in this track, students must complete two politics courses and ECO 100 and ECO 101, and MAT 103 (or higher level) before the end of their sophomore year. All five of these courses should be taken on a graded basis (i.e., not pass/D/fail). (Under special circumstances, students can apply for exceptions or deferrals of these prerequisites. These requests will be considered by the PE adviser.)

It is important for each student to select a combination of economics and politics courses that form a coherent and meaningful track. Before signing up for the first term of junior year, the student should work out a tentative course outline for the next two years; this outline must be approved by the PE adviser.

In addition to the PE prerequisites, a student in the PE track is required to complete the following courses, all of which will be counted as departmentals:

- Political Economy: either Political Economy (POL 349), Comparative Political Economy for Policy Making (SPI 329/POL 350),* or Comparative Political Economy (POL 352)*. (*NOTE: Students may take either SPI 329/POL 350 or POL 352 — not both.)

- Game Theory in Politics: Game Theory in Politics (POL 347/ECO 347).

- Quantitative Methods: POL 345/SOC 305/SPI 211, POL 346, ECO 202, ECO 302, or ECO 312.

- Microeconomics: One of the following intermediate microeconomics courses: ECO 300, ECO 310, or SPI 300.

- Macroeconomics/Topics: One of the following courses: Intermediate Macroeconomics (ECO 301, ECO 311), International Trade (SPI 301/ECO 352), International Development (SPI 302/ECO 359), Public Economics (SPI 307/ECO 349).

Together with five additional courses in the politics department (possibly including POL courses counted as prerequisites), this 10-course combination fulfills the requirements both for the PE track and for the major, and is used in calculating departmental honors.

Students in the PE track must also fulfill the 3-2-1 field distribution requirement of the department, however, the quantitative methods course will satisfy the politics department's analytical requirement, while POL 347/ECO 347 can serve as a course in a third field.

While a student in the track must write a thesis on a topic related to the student's primary field, the thesis must also incorporate significant PE content. On or before the thesis draft deadline, the PE content of the thesis must be certified by the PE adviser. The student should meet with the PE adviser well in advance of this deadline to discuss the PE content of the thesis.

Track in Quantitative and Analytical Political Science

The track in quantitative and analytical political science (QAPS) is designed for students who wish to deepen their understanding of quantitative and analytical methods to study key questions in political science.

Prerequisite

- MAT 175 (or its equivalent EGR 192, MAT 201, MAT 203)

In addition to the prerequisite, students must complete four courses among those listed below along with six other departmental courses. Of the following six courses, students must take four with at least one being in quantitative analysis as well as at least one from the game theory and applications category.

- Quantitative Analysis: SOC 245/POL 245, 345, 346

- Game Theory and Applications: POL 250, 347, 349, SPI 329/POL 350*, 352*. (*NOTE: Students may take either SPI 329/POL 350 or POL 352 — not both.)

Senior Thesis

While a student in the track must write a thesis on a topic related to the student's primary field, the thesis must also incorporate quantitative and/or analytics methods at a level similar or superior to the material covered in the track requirements. The student should meet with the QAPS adviser during the fall semester of senior year to confirm the suitability of their thesis research design. On or before the thesis draft deadline, the appropriate content of the thesis must be certified by the QAPS adviser.

Track in Race and Identity

The Department of Politics offers the track in race and identity (RI) for politics majors seeking a deeper understanding of the politics of race and identity. Completion of the track attests to a student having successfully taken a range of courses examining the role of race and identity in politics. The track offers courses dealing with moral, ethical and legal issues relating to race and identity in the United States and around the world, such as hate speech, discrimination and civil rights. The track also encompasses courses in international relations and comparative politics focusing on human rights, ethnic conflict and social movements.

This track is suitable for students interested in all politics subfields, including political theory, American politics, comparative politics, international relations, political economy and methods. Currently, the widest array of courses in the track is available in the subfield of American politics. As with other department tracks, students enrolled in the RI track must still fulfill other requirements for politics majors, including the 3-2-1 distribution requirement (a primary field, a secondary field and a tertiary field). A single course can simultaneously satisfy a distribution requirement and count toward the track.

The track in race and identity has the following course requirements:

- Core Course. All students in the track must take POL 344/AAS 344/AMS 244 (Race and Politics in the United States).

- Other Courses. Students must complete three other courses dealing with themes of race and identity, in addition to the core course and the six other departmental courses required for the politics major. A menu of courses that can be taken toward completion of the RI track is provided below. (New departmental courses that meet the requirements for this track will be added to the track, as applicable.)

- POL 316 Civil Liberties

- POL 319/AMS 219/AAS 386 Antidiscrimination Law

- POL 339 The Politics of Crime and Punishment

- SPI 331/SOC 312/AFS 317POL 343 Race and Public Policy

- POL 356 Comparative Ethnic Conflict

- POL 357/SPI 314/GSS 399/SAS 357 Gender and Development

- POL 360 Social Movements and Revolutions

- POL 380 Human Rights

- POL 386 Violent Politics

- POL 405/CHV 406 The Ethics of Borders and Migration

- POL 417/CHV 417 Colonialism and Historic Injustice

- POL 422/GSS 422 Gender and American Politics

- SPI 337/POL 424 Black Politics and Public Policy in the U.S.

- POL 477/CHV 477/JRN 477 Expressive Rights and Wrongs: Speech, Offense, and Commemoration

NOTE: The department will consider requests for other courses to apply toward the track on a case-by-case basis with a caveat that students may seek approval for only one nonpolitics course to count as satisfying a requirement for the track. To seek such approval, students must complete the cognate approval application and send a current syllabus to the cognate approval adviser along with the RI track adviser for review, no later than the last day of classes within the semester that the course is offered during junior and senior years. The only exception is during the spring semester of senior year, when the cognate application deadline is the second Friday of classes.

Students in the track must write a senior thesis that incorporates themes relating to race and identity. Students should meet with the RI track adviser during the fall semester of their senior year to confirm the suitability of their thesis topic for the track. On or before the thesis draft deadline, the suitability of the thesis must be certified by the RI track adviser.

Independent Work

Junior year.

The junior independent work (JIW) requirement in politics provides majors with an opportunity to delve into their research interests and conduct a thorough examination. The goal is for students to produce a well-reasoned and analytical essay that scrutinizes a political issue using approaches from political science. Over the course of two semesters, students will undertake two research projects. In the fall, students will be required to submit a research prospectus, while in the spring, they will write a full-length junior paper (JP). The required POL 300 will instruct students in research design and the preparation of their research prospectus. The faculty instructors for the practicum component of POL 300 will serve as fall JIW advisers. The spring JP can either build on the prospectus or explore a new topic. Each semester serves a specific purpose; the fall focuses on teaching students how to plan a research project and refine a question, while the spring is focused on executing the project and exposition. Additional information on topics such as adviser assignment and final deadlines is available in the junior independent work and senior thesis sections of the department's website .

Students will receive one POL 981 grade (worth 2.0) at the end of the spring term that is a weighted average of fall (30%) and spring (70%) JIW grades. Students must achieve a grade of C or better in POL 981. If a student receives a grade below C in POL 981, another JP is required with a grade that brings the average of this additional paper and the POL 981 grade to at least a grade of C. This is a prerequisite for beginning the senior year. For purposes of this requirement, the grades before the application of any late penalties are used.

Senior Year

During the senior year, each student writes a thesis, an essay of generally about 100 double-spaced pages and rarely fewer than 80 pages. The senior thesis normally is written on a topic within a student's primary field. The senior thesis is expected to make an original (or otherwise distinctive) contribution to broader knowledge in the field in which the student is working, and it is important that the thesis be situated explicitly in relation to existing published literature. The department encourages students to use the summer between junior and senior year for work on the senior thesis.

The senior thesis may expand upon ideas that were explored in a student's JP. A student may draw on and cite their own JP just as they would use other resources. In addition, a student may re-use a limited portion of their JP in the senior thesis; for instance, the literature review could be re-used across the two. Whenever material from the JP is re-used, a student must add a footnote noting the duplication across the JP or senior thesis. Note: This policy does not affect the standard University guidelines for attributing ideas and research findings, whenever appropriate. The same policy holds with respect to incorporating the fall junior research prospectus into either the spring JP or senior thesis.

Senior Departmental Examination

Seniors are required to prepare and present a professional poster describing their senior thesis research as the senior comprehensive exam.

Study Abroad

Under normal circumstances, the department encourages students to consider studying abroad during the spring semester of junior year. If a program is approved in advance by the Office of International Programs (OIP), the department will credit as departmentals as many as two courses in political science (or related fields) when they are taken at an overseas university. Normally, the department is willing to substitute no more than one cognate and one departmental or two cognates for majors studying abroad for one semester. In the spring term, students who study abroad will write a JP under the supervision of a politics faculty member who will advise them remotely.

NOTE: Students may not study abroad during the fall semester of junior year as they need to be on campus to take POL 300, as part of completing the Fall JIW requirement — beginning with the Class of 2025.

Students may study abroad in the fall semester of senior year provided that they have the preapproval of both OIP and the study abroad adviser. The department will allow up to four study abroad politics courses to count only in the event a student wants to study abroad in the spring of junior year and then again in the fall of senior year — two for each semester abroad.

Prospective majors who wish to study abroad during sophomore year who intend to declare politics as a major should receive preapproval for departmental course credit from the study abroad adviser. The department will accept up to two politics-related study abroad courses from sophomore year which can be applied toward the major, one of which can count as a politics prerequisite. ( This rule suggests that one of the prerequisites must be a politics course that was taken at Princeton no later than the end of sophomore year.)

- Alan W. Patten

Associate Chair

- Kristopher W. Ramsay

Director of Undergraduate Studies

- Matias Iaryczower

Director of Graduate Studies

- Mark R. Beissinger

- Gary J. Bass

- Charles R. Beitz

- Carles Boix

- Charles M. Cameron

- Rafaela M. Dancygier

- Aaron L. Friedberg

- Paul Frymer

- Robert P. George

- G. John Ikenberry

- John Kastellec

- Melissa Lane

- Frances E. Lee

- John B. Londregan

- Stephen J. Macedo

- Nolan McCarty

- Tali Mendelberg

- Helen V. Milner

- Andrew Moravcsik

- Layna Mosley

- Jan-Werner Müller

- Grigore Pop-Eleches

- Markus Prior

- Jacob N. Shapiro

- Arthur Spirling

- Anna B. Stilz

- Rocío Titiunik

- James Raymond Vreeland

- Leonard Wantchekon

- Ismail K. White

- Keith E. Whittington

- Jennifer A. Widner

- Deborah J. Yashar

Associate Professor

- Jonathan F. Mummolo

- LaFleur Stephens-Dougan

- Hye Young You

Assistant Professor

- Christopher W. Blair

- Gregory A. Conti

- German S. Gieczewski

- Tanushree Goyal

- Naima N. Green-Riley

- Saad A. Gulzar

- Gleason Judd

- Patricia A. Kirkland

- Melissa Megan Lee

- Elizabeth R. Nugent

- Rebecca L. Perlman

- Guadalupe Tuñón

- Andreas B. Wiedemann

Associated Faculty

- Christopher L. Eisgruber, President

- Daniel Garber, Philosophy

- Elizabeth L. Paluck, Psychology

- Philip N. Pettit, Center for Human Values

- Kim Lane Scheppele, Schl of Public & Int'l Affairs

- Michael Smith, Philosophy

- Brandon M. Stewart, Sociology

Lecturer with Rank of Professor

- Allen Carl Guelzo

- Shilo Brooks

- Tolgahan Dilgin

- David R. Hill

- Thomas D. Howes

- Marzenna James

- Corrine M. McConnaughy

Visiting Lecturer

- Mark O'Brien

- Gregory Sullivan

For a full list of faculty members and fellows please visit the department or program website.

POL 210 - Political Theory Fall EM

Pol 220 - american politics (also spi 310) fall sa, pol 230 - introduction to comparative politics (also spi 325) fall sa, pol 240 - international relations (also spi 312) spring sa, pol 250 - introduction to game theory not offered this year sa, pol 301 - political theory, athens to augustine (also cla 301/hls 303/phi 353) fall em, pol 302 - continental political thought not offered this year em, pol 303 - modern political theory spring em, pol 304 - conservative political thought not offered this year em, pol 305 - radical political thought spring em, pol 306 - democratic theory (also chv 306/phi 360) not offered this year em, pol 307 - the just society (also chv 307) not offered this year em, pol 308 - ethics and public policy (also chv 301/spi 370) fall em, pol 309 - politics and religion (also rel 309) not offered this year em, pol 313 - global justice (also chv 313) not offered this year em, pol 314 - american constitutional development not offered this year sa, pol 315 - constitutional interpretation fall sa, pol 316 - civil liberties spring cdem, pol 318 - law and society spring sa, pol 320 - judicial politics spring sa, pol 321 - american political thought spring cdem, pol 322 - public opinion not offered this year sa, pol 323 - party politics not offered this year sa, pol 324 - congressional politics spring sa, pol 325 - the presidency and executive power not offered this year sa, pol 327 - mass media, social media, and american politics (also jrn 327) spring sa, pol 329 - policy making in america not offered this year sa, pol 330 - electing the president: voter psychology and candidate strategy not offered this year sa, pol 332 - topics in american statesmanship spring emla, pol 333 - latino politics in the u.s. (also lao 333/las 333/soc 325) not offered this year sa, pol 343 - race and public policy (also aas 317/soc 312/spi 331) not offered this year sa, pol 344 - race and politics in the united states (also aas 344/ams 244) fall cdsa, pol 345 - introduction to quantitative social science (also soc 305/spi 211) fall qcr, pol 346 - applied quantitative analysis spring qcr, pol 347 - game theory in politics (also eco 347) spring qcr, pol 349 - political economy fall sa, pol 351 - the politics of development (also las 371/spi 311) spring sa, pol 352 - comparative political economy not offered this year sa, pol 353 - the politics of modern islam (also nes 269) not offered this year ha, pol 355 - comparative politics of legislatures not offered this year sa, pol 356 - comparative ethnic conflict not offered this year sa, pol 360 - social movements and revolutions fall sa, pol 362 - chinese politics (also eas 362/spi 323) not offered this year sa, pol 364 - politics of the middle east (also nes 322) fall sa, pol 366 - politics in africa (also afs 366) not offered this year cdsa, pol 367 - latin american politics (also las 367/spi 367) not offered this year sa, pol 368 - modern iran (also nes 365) ha, pol 374 - russian and post-soviet politics not offered this year sa, pol 375 - politics after communism not offered this year sa, pol 378 - politics in india not offered this year sa, pol 380 - human rights (also spi 319) spring sa, pol 381 - theories of international relations not offered this year sa, pol 385 - international political economy fall sa, pol 386 - violent politics fall sa, pol 388 - causes of war (also spi 388) fall sa, pol 392 - american foreign policy fall sa, pol 393 - grand strategy (also spi 315) not offered this year sa, pol 403 - architecture and democracy (also arc 405/chv 403/ecs 402) spring em, pol 410 - seminar in political theory (also chv 410) not offered this year em, pol 411 - seminar in political theory not offered this year sa, pol 412 - seminar in political theory (also hum 411) not offered this year em, pol 413 - seminar in political theory not offered this year sa, pol 416 - moral conflicts in public and private life (also chv 416) not offered this year em, pol 420 - seminar in american politics not offered this year sa, pol 421 - seminar in american politics not offered this year sa, pol 422 - gender and american politics (also gss 422) spring cdsa, pol 423 - seminar in american politics fall sa, pol 430 - seminar in comparative politics (also spi 424) fall sa, pol 431 - seminar in comparative politics (also las 390/spi 425) spring sa, pol 432 - seminar in comparative politics (also spi 426) spring sa, pol 433 - seminar in comparative politics not offered this year sa, pol 434 - seminar in comparative politics fall sa, pol 440 - seminar in international relations not offered this year sa, pol 441 - seminar in international relations not offered this year sa, pol 442 - seminar in international relations spring sa, pol 443 - seminar in international relations not offered this year sa, pol 450 - seminar in methods in political science not offered this year qcr, pol 465 - political and economic development of the middle east and north africa (also afs 465/nes 465) fall sa, pol 479 - comparative constitutional law (also chv 470/spi 421) spring sa.

Senior Thesis Poster Session

The Department requires the production and presentation of a thesis poster in lieu of a comprehensive exam. The poster requirement has deepened students’ learning by requiring them to present their work to a wide audience of their peers and faculty members.

Early in the Spring semester, the Department hosts two poster information sessions. A handout with important guidelines will be distributed at that time. Students who are curious about what a poster looks like are welcome to view exemplary posters which are displayed outside of 127 Corwin Hall.

Students are required to upload a PDF of their thesis poster into the Politics Thesis Poster Database by the stated deadline . A link to the database, along with instructions, will be sent as the deadline nears. An initial penalty of 2/3 of a letter grade and an additional penalty of 1/3 of a letter grade for every 24 hours that a poster is late will be applied, beginning at 4:00 pm on the PDF due date. [NOTE: The Department will order and pay for the posters.]

Students must also attend the Senior Thesis Poster Session , which will be held during Reading Period. Students are required to be at the Poster Session for the full duration.

Seniors’ posters and their oral presentations are evaluated by faculty graders according to the following criteria:

- Visuals & Mechanics: Is the poster visually appealing, legible, uncluttered, and well written (spelling & grammar)? Does it make effective use of visualizations (graphs, charts)?

- Research Question: Does the poster clearly state the main research question? Does it show one or several hypotheses that derive from the research question?

- Methods and Results: Does the poster provide information about the evidence used and link between hypotheses and evidence? Are results presented effectively?

- Structure & Organization: Does the poster have clear sections, a logical flow, and effective use of labels?

- Oral Presentation: Was the oral presentation clear and within the allocated time? Did it effectively and succinctly communicate the main argument made in the poster?

Beginning with the Class of 2022, the Department will award four $500 outstanding senior thesis poster prizes. Three will be determined by faculty graders, and one will be determined by an audience vote.

Questions about the thesis poster session requirement should be directed to the Department Coordinator, Gina Palmisano .

- Skip to search box

- Skip to main content

Princeton University Library

- PUL Quick Answers

- Special Collections

Q. How do I access Princeton University Senior Theses?

- Economics & Finance

- General Library

- Interlibrary Loan & ArticleExpress

- Makerspace - Test

- 1 Appraisals

- 1 Conservation

- 5 Digitization

- 2 Donations

- 5 Princeton University

- 1 Publications

- 10 Research help

- 1 Rights & Permissions

- 6 University Archives

Answered By: Mudd Library Last Updated: Dec 18, 2023 Views: 3494

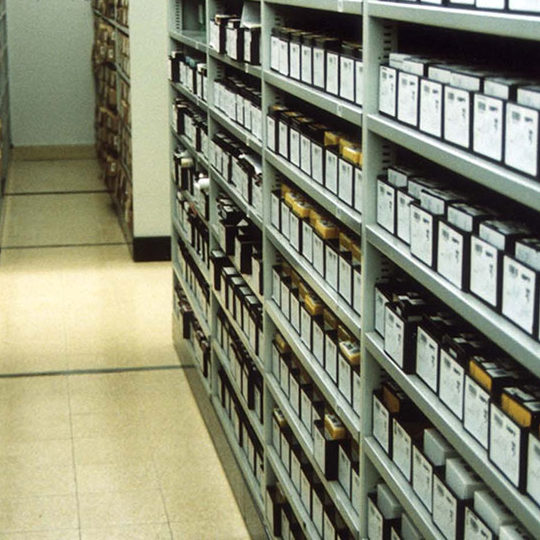

The Princeton University Archives located in the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library is the official repository for Princeton University undergraduate senior theses from 1924 to the present.

Digital and Original Format Senior Theses

Members of the University community with an active NetID can access digital theses in Dataspace when connected to any Princeton-networked computer (if you’re not on campus, please first connect to the campus network via the GlobalProtect or SonicWall desktop applications).

Independent researchers who are not members of the University community (including Princeton alumni) should use the Library Catalog or DataSpace to browse senior theses.

Please create a Special Collections Research Account , if you don’t already have an active account, prior to submitting the Senior Thesis Order Form. In some cases we will be unable to digitize the senior thesis due to an embargo that prohibits digital access. Copyright of the theses are held by the author.

Senior Thesis Order Form

Please note: your order can only be fulfilled if you have completed the Senior Thesis Order Form and have a current Special Collections Research Account. Due to high volume, staff are unable to respond to requests without the necessary information.

Original Format Senior Theses - In person

- You are welcome to view senior theses that have not been scanned or born-digital in our reading room at Mudd Library . No appointment is needed during our academic hours which are Monday through Friday, 9:00 AM - 4:45 PM.

- We recommend researchers create a Special Collections Research Account to submit online requests for material in advance of your visit. Material can be requested through the Princeton University Catalog . We encourage you to submit your requests in advance. Once you have arrived and been signed into the reading room, we will page up to 6 items at a time. If you are having any issues with registering or requesting materials, we can assist you by submitting an Ask Us! or when you arrive in person.

Please note : Researchers will be asked to show a photo ID such as a driver's license or academic/work ID upon arrival to Special Collections reading rooms. While it is not required at Mudd, we do recommend making your way to Firestone Library to obtain an Access Card as it will ease future visits. Should you not obtain an Access Card, you will need to show your photo ID at each visit to Mudd Library. Visitors to Firestone Library are required to obtain an Access Card to make it easy to enter the library's turnstiles.

Laptops, cell phones, cameras and pencils are permitted in the reading room. All other personal belongings can be placed in one of our free, secure lockers. More information about reading room guidelines can be found on our website . If you have accessibility needs that will impact your ability to conduct your research effectively or comfortably, please don’t hesitate to let me know and our team will do our best to accommodate you.

For additional information, please visit Theses & Dissertations page of our website. Please direct any questions you may have to Special Collections staff via Ask Us! .

Links & Files

- How can I access Special Collections?

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 1 No 1

Related Topics

- Princeton University

- Research help

- University Archives

- Digitization

BONUS: What Makes the Senior Thesis So Cool?

The senior thesis requirement is unique to Princeton, providing a memorable opportunity for students to delve into topics of their interest. Essential to this process is a mentor or advisor, and Princeton faculty are among the top experts in their fields, ready to help budding researchers.

In this bonus episode, SPIA faculty talk about their experiences advising student work and how they help students produce their best work. This episode features Marta Tienda , Maurice P. During Professor in Demographic Studies, Emeritus; Rory Truex , assistant professor of politics and international affairs; and Paul Lipton , associate dean for undergraduate education at SPIA.

Tiger Prints is a podcast series highlighting tomorrow’s leaders solving today’s problems. The show features recent SPIA grads and their senior research projects. After four years at Princeton, these students are prepared to take the next step in their careers, with their theses serving as the foundation. The show was produced, hosted, and edited by Hope Perry ’24 , SPIA podcast production intern, with production assistance from B. Rose Huber , communications manager and senior writer at SPIA. The show was supported by summer interns Jenna Thompson and Riis L. Williams with design by Imaan Khasru '23 .

Search form

Inbox inspiring examples of senior theses.

What a wonderful article, with inspiring examples of noteworthy theses. I’m now even prouder to be a Princeton alum. Thank you for highlighting the fact that Princeton alone requires a senior thesis. We’re all indebted to Dean Luther Eisenhart for having such confidence in Princeton’s students that he introduced the thesis opportunity more than a century ago. And it is a wonderful opportunity, not an onerous requirement!

Department of Near Eastern Studies

Senior Thesis Guidelines

Writing in near eastern studies, a guide to independent work.

Jonathan Gribetz, Director of Undergraduate Studies ( [email protected] ) M. Qasim Zaman, Chair (mzaman@)

Table of Contents

Writing in near eastern studies: an overview, goals of the thesis.

- Important Dates for Senior Theses and Comprehensive Exams, 2016–2017 (webpage)

Finding a Topic

Working with your advisor, formulating your research question, putting it together: the prospectus, drafting and time management, revising, proofreading, and copyediting.

- Thesis Writing Group

Formatting, Style, and Mechanics

Submission of the final copy, the comprehensive exam, nes grading standards for theses, sample thesis title page, comprehensive exam form.

Princeton’s Department of Near Eastern Studies (NES) is dedicated to the study of the peoples of the Near East and their histories, societies, politics, languages, literatures, and religions. NES’s chronological coverage is unusually broad, extending from the pre-Islamic period through the present day. Geographically, NES encompasses the area we commonly think of as the Middle East—the Arab lands, Iran, Israel, and Turkey—as well as the Balkans, South and Central Asia, and the Muslim lands of Southeast Asia. NES defines itself by its subject matter, not disciplinary approach or mode of inquiry. Members of the department draw on a wide range of methods and approaches to guide their research, selecting those most suitable to the question they are posing. Concentrators writing in NES thus enjoy extraordinary flexibility in choosing their research questions. Chronology, geography, and methodology constrain the student only in the broadest sense. A student therefore should concentrate on first identifying a research question that truly excites him or her and then select the appropriate methodology to answer that question.

Concentrators in NES write one Junior Paper (JP) in the spring semester of the junior year and one senior thesis. A JP written in the Department of Near Eastern Studies is normally an essay of 20 to 30 double-spaced pages, while a senior thesis is typically a focused essay of 70 to 100 double-spaced pages (or around 25,000 words of text excluding footnotes). Both focus on topics related to the peoples, history, societies, religions, politics and/or cultures of the Near East. Most commonly, independent work in the department addresses topics in Near Eastern history, politics, religion, and literature, but students have also tackled subjects in fields as diverse as medical anthropology and the economics of the energy industry. Although the department does not require students to use sources in a Near Eastern language, it does strongly encourage students who are sufficiently proficient to do so.

While the remainder of this guide is addressed to writers of the thesis, much of its advice and instruction will be helpful to writers of the JP. For more information on the schedule of JP deadlines and departmental expectations, see Junior Work Guidelines .

See a list of Past Senior Thesis Titles .

(return to top)

A senior thesis in NES should perform the following tasks:

- define a research question, and formulate and advance a clear claim (hypothesis) or set of claims;

- gather, present, and analyze evidence in support of its claim(s);

- review and engage the scholarship of others on the subject;

- assess critically the strengths and weaknesses of its own logic, evidence, and findings;

- relate its conclusions to a larger context;

- make an original contribution to knowledge.

A thesis must have an argument. It should not be a passive review of the existing literature, a summary of facts, or a mere description of past events. The question it poses should be significant. In other words, the thesis must have and make clear what Princeton’s Writing Program calls “motive.” Motive, to recall, is what explains to the reader why the thesis is worth reading. Or, in still more direct terms, the thesis should have an answer to the question “so what?” As will be discussed in more detail, motive can come in many different forms. But whatever form the motive may take, a thesis needs it.

Having posed a question and justified why that question deserves to be posed, the thesis should then present an analysis that marshals sound reasoning and evidence to arrive at an answer. To be successful, a thesis need not be entirely comprehensive or convincing in every aspect–the faculty recognizes that this is your first attempt at substantial scholarship–but at its core it must have an argument. A superior thesis, moreover, will address possible counter-arguments and objections, as this reveals clearly the depth and range of the student’s thinking and research.

The presentation of the student's own reasoning and conclusions is thus the central part of the thesis. This is worth emphasizing, because all too often students fret excessively about the amount and detail of the information they put in the thesis, operating under the mistaken assumption that more is better. While a thoroughly researched thesis is always preferable to a poorly researched one, a carefully argued thesis that rests on inconclusive evidence is preferable to a sloppily reasoned or logically confused thesis that presents an abundance of details and citations. Work hard, but do not forget to work smart.

Important deadlines for elements of the thesis, designed to assist you in planning your year’s work and encourage you to work early and smart, may be found on the “ Important Dates: Seniors ” webpage.

Writing a Thesis: The Process

Writing a thesis is a challenge. It requires you, the student, to call upon the knowledge, skills, and insights you have acquired at Princeton to produce a work of original scholarship. Although you will have a faculty advisor and other resources to guide you along the way, the thesis ultimately is yours and yours alone. Working on your own, you are responsible for conceiving, researching, and writing up a piece of research worthy of an academic year’s effort.

Writing a thesis may be a daunting task. But it need not be, and indeed should not be, an overwhelming one. When approached in the right manner, the process is certainly manageable. It can even be pleasant. Many students find the thesis to be the most rewarding academic experience they have at Princeton. If you take to heart the information and suggestions provided herein, this guide will help ensure that your own experience of writing a thesis is a productive and positive one.

As an Arabic proverb teaches, “Knowledge is a sea without shores.” There is no end to the amount of facts and details you can accumulate about the world. The more knowledge you assimilate, the more questions arise. Swimming in the sea of knowledge is exhilarating, but it can also be disorienting and exhausting. The horizon constantly recedes before you as each fact learned and perspective assimilated yields way to more facts, more perspectives. The researcher looking to master a topic simply by reading everything on it soon finds him or herself truly “out at sea.” Floating and without direction, that researcher expends energy as he or she spins in increasingly wider circles, aimlessly adrift.

The smart swimmer avoids drowning in a sea of data by charting a course before reaching the deep waters. The first step toward charting a course is to select your topic early. Sooner is better, but you should certainly know what general topic you wish to work on when you return to campus in September. At the very beginning of the semester, you will be asked to write a one-paragraph description of the topic on which you wish to work. This brief description will serve as the basis on which you will be assigned an advisor.

At this point it is sufficient to have selected a general focus of research, for example British policies toward the Persian Gulf after WWI, the place of Sufism in the lives of contemporary Pakistanis, Ba’athism and minorities, the evolution of Israeli policy on Jerusalem, or the depiction of married women in classical Arabic literature. These are topics narrow enough that one can survey the available published materials and other sources to acquaint oneself with significant debates in the literature, get a sense of the available sources, and begin to hone in on some specific research questions. At this stage, exploration is fine and even encouraged. The summer is a particularly good time for background reading. Regardless of when you start, however, by the middle of the fall semester you should have a concrete idea of what your thesis topic will be.

Once you have been assigned an advisor, you should make an appointment to see him or her. Advisor-advisee relationships vary as much the people that make them up. Nonetheless, there are some basic expectations. First, your advisor is there to provide general guidance and advice. It is not your advisor’s responsibility to assign a research question, find sources for you, or to keep you on track. Researching, writing, and completing the thesis are all your responsibility. Your advisor can work with you to set up a schedule for the completion of your research and writing. Keep in mind, however, that the deadlines are your deadlines, not your advisor’s. You owe it to yourself, not your advisor, to complete your thesis. After all, the final product will bear your name, not your advisor’s name.

Because the schedules, working habits, and projects of students and faculty advisors vary so greatly, there is no standard template for advising. You should meet with your advisor within two weeks of being assigned, and you should plan to meet with your advisor at a minimum of twice each semester. For most students, meeting twice per month works well.

Your advisor is obligated to read and comment on one draft of each of your chapters. Please note the final deadline for submission of rough drafts as listed on the “Important Dates: Seniors” web page . If you submit a draft any time before this deadline, your advisor is responsible for reading, commenting on, and returning it to you in a timely manner. If you miss that deadline, however, you may not necessarily expect your advisor to read your draft materials.

The most critical step in writing a thesis is converting your general topic of interest into a research question. A properly constructed question gives direction to the research and focus to the writing. It provides the kernel of the argument around which the thesis is built. Getting the question right will reduce or eliminate some of the common anxieties that plague thesis writers, such as: where is my research going? Where should my research stop? How should I organize my thesis? What material should I include and what should I leave out?

Some students zero in on a question from the very beginning. More commonly, students make their way to their question gradually, starting off with a general interest or curiosity in a given phenomenon, era, locality, society, etc. As they acquaint themselves more closely with the scholarly literature on a topic, they identify a question.

Perhaps the most common mistake that undergraduates make when writing their theses is to cast their nets far too wide, i.e., selecting broad topics that are worthy of a book or two or three. Students often feel compelled to overreach out of an admirable but misplaced sense that they must come up with a “weighty” topic, and this leads them to select overly ambitious topics. Researching and writing a book can take several years, whereas you have only several months. A thesis question can almost never be too narrow.

There are several ways to narrow your research. The most obvious way to begin is to restrict the scope of research in time and space. Thus, for example, a student interested in the evolution of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt from 1928 to 2008 would perhaps be well advised to address only the years through 1947. A student intrigued by the grand topic of Arab nationalism might be best off concentrating on a relatively narrow sliver of history in a single country, say Iraq between monarchical and Ba‘athist rule, 1958–1968.

Such mechanical measures are helpful in bringing greater focus to a study, but in themselves they are never sufficient. Not unlike fractals, history and human society can grow in complexity the more closely one looks. After all, books and studies are routinely written about individuals, i.e., biography, and single events that unfolded in the space of just a few days or even hours. There is no necessary correlation between the chronological and geographical extent of a study and that study’s length or sophistication. There are books on the so-called “Six Day War” of 1967 that are longer than histories of either Israel or the Arabs.

To bring focus to a thesis, what is needed is a question. A good question will intrigue the reader, address an issue of importance, frame your study, and give it direction. Not least important, that question should excite you. It is the single most important factor in determining whether your experience of writing a thesis proves to be a stimulating, rewarding, and even, yes, a fun one, or instead an exercise in anxious drudgery. When a question provokes you, research and writing can become a welcomed adventure as you work to satisfy your personal curiosity and then express your thoughts. When you are indifferent to your question, research and writing alike become chores. Good, well-formulated questions lead to cogent and provocative theses, whereas bad, half-formed questions invariably lead to stale theses. Only you can know what truly fires your curiosity. Do not be shy in pursuing what intrigues you.

Scholarship, of course, is a public endeavor, not a private indulgence. Thus, when formulating your question you will need to give some thought to motive, i.e., the reason(s) why your research will be worth reading. Motive explains what or how your research contributes to scholarship. Establishing motive should not be onerous or difficult, but it will require you to read carefully and engage with the scholarly literature on your topic. Once you have done that, establishing motive is not difficult. All you need to do is to make clear to yourself and then the reader how your research relates to what has already been published. Motive can take many different forms and combinations, including one, or more, of the below:

- Knowledge on this topic is limited. My thesis adds to that knowledge by…

- A scholarly consensus on this topic does not exist. Interpretations differ or theoretical schools clash. My thesis weighs in on this dispute by comparing the leading interpretations and contends…

- The conventional wisdom on this topic is flawed. My thesis will demonstrate this by…

- The standard theory tells us to expect ‘x’ in such cases, yet here we see ‘y.’ The reasons for this discrepancy are…

- The phenomenon of ‘x’ is an important but a complex and difficult one to study. As this thesis will demonstrate, the study of sub-phenomenon ‘y’ can yield important insights into ‘x’…**

The key to making sure your final thesis has a good motive is to formulate a good research question. Your advisor can help you convert your enthusiasm for a topic into a proper research question. Do not expect, however, that your advisor will hand you a pre-formed research question. The more reading and thinking that you do, the easier you will find it to devise a suitable research question.

The best research questions often come in the form of a puzzle. Counter-intuitive observations are excellent leads to a good research question. When a given outcome or state of affairs defies our common expectation or the prediction of an accepted theory (which are typically very much the same thing), this piques our curiosity. It provokes the question, why this and not that? Such puzzles are all around us. Examples might be: Given Saudi Arabia’s official Wahhabi theology and its status as a monarchy, how does the Saudi regime publicly justify its close alliance to the US? Scholars have established a close correlation between growth in per capita income levels and democratization, yet why is it that in the Arab world the wealthiest Arab societies are proving the most resistant to democratization? The Iranian Revolution has been described by many as an emphatic rejection of Western modernity, yet then, one might ask, how does one explain that under the Islamic Revolutionary Regime the absolute and relative numbers of women receiving higher educations has increased dramatically since 1979? In each case, one must move from a general topic—US-Saudi relations, democratization in the Arab world, the Iranian Revolution and its legacy—toward a question that might focus the thesis and guide the research and writing.

As the three examples stand, they are each too expansive for a thesis. But they can each be narrowed. Thus, for our first example, one might concentrate on the writings of a single religious authority or declarations of a government ministry over a defined period of time, perhaps chosen to overlap with a key moment in US-Saudi relations (e.g., before and after the Arab oil embargo of 1973 or before and after the attacks of September 11). For the second, one might select a single country, such as Qatar. For the third example, one might start by searching policy statements of the Iranian Ministry of Education and/or universities regarding women and higher education and select several universities for collecting data on rates of female enrollment.

A critical step toward completing a thesis is putting together a prospectus. A prospectus lays out your research question, explains the motive, and points the research in the direction it will take in the months ahead with an outlined plan of research and writing. If that sounds like a lot to commit yourself to at the beginning of November, you can relax a little. A prospectus is not a pledge breakable on pain of death. To the contrary, a prospectus is a preliminary map or plan laying out where you think you are, where you wish to go, and how you intend to get there—i.e., the type of evidence that will help you to answer your questions, and your analytical method. Each of these components is distinct, but each is bound to the other. A change in one will necessitate a change in the others. Since it is possible, even probable, that the path your research and writing will take will deviate significantly from that laid out in the prospectus, it is important to think about the relationship between your research questions, your methods, and your collection of evidence early on, so that as you begin to revise one of these elements, you will also make any appropriate changes regarding the other elements. The exercise of drafting a prospectus accomplishes this, and compels you to conceive of the thesis and its research and writing holistically.

By giving structure and direction to the process of research from the beginning, the prospectus can thereby save you a lot of grief. The temptation to postpone writing and conduct more “background” research is always strong, and in instances where the hypothesis is poorly formed and the research question vague, that temptation becomes irresistible. The result is to fritter away precious time going around in circles, piling up reading after reading but getting nowhere with the thesis. Drafting a prospectus will help you identify sooner rather than later whether you have a properly framed research question, a compelling hypothesis, relevant and accessible evidence, and a feasible thesis.

A prospectus should, as a rule, address the following five questions:

- What is my question? i.e., what am I trying to argue? This, obviously, is the heart of the thesis and the most important question.

- Why is it important? Why should the reader care? Or, in other words, what is my motive? As noted above, answers to this question can take many different forms. They can vary tremendously in their stakes. A thesis on food security in Egypt might claim that its findings could help avert the impending mass starvation of millions. A thesis testing the relationship of mass literacy to the rise of Pan-Arabism might promise to refine a theory of nationalism. An analysis of an Arabic poem could claim to resolve a debate over the meaning of a disputed word or phrase. In other words, the perceived magnitude or “real life” significance of the question can take a variety of forms. If the question interests you, it is almost certainly important enough. But you do need to make clear to the reader what is at stake and how the thesis contributes to resolving the given issue.

- Who else has tried to answer this question or written on this topic, and what are their arguments? Scholarship has a paradoxical nature. On the one hand, in its conduct it is generally a very solitary pursuit. On the other hand, it is innately public in its purpose. Research that does not seek to further general knowledge is not scholarship. An essential aspect of scholarly research thus is relating one’s research to that of others. That relationship may take many different forms. Your goal might be to challenge received wisdom head-on, to extend that wisdom further, or to identify and fill in the holes that other scholars have missed. What is important is that you situate your research in relationship to that of others. This is not as dreary an exercise as it might sound, and the good news is that typically it clarifies and sharpens one’s own assumptions and hypotheses, and in the process makes it much easier to write a thesis. Once you know clearly what you are arguing against, you can define more precisely what you are arguing for. That, in turn, tells you how to build your case and arrange your evidence.

- Why is my argument better than the preceding ones? How will this research contribute? Coming up with a new argument, or adding new insights or evidence to a pre-existing one, is an essential objective of scholarship. Your thesis must speak to the existing literature, but it should not merely echo it. Thus the prospectus should explain how or what your argument might add to our current knowledge. The contribution can be modest, and in the case of a senior thesis it almost certainly will be. You are not expected to effect a paradigm shift in your field or to pioneer the use of a hitherto untapped body of sources. It can be enough for a thesis to compare and contrast two competing interpretations of a given event or phenomenon and to conclude in favor or one or to identify the strengths and weaknesses of both. Revisiting old sources and arguments with a different perspective is also acceptable, but you should be explicit about where you make an original contribution.

- Why do I think I am right and why should a reader think I am right?

Novelty by itself, of course, does not make for good scholarship. The conclusions of our research must also be persuasive to others. A prospectus, therefore, should make a brief case for why the research is likely to prove convincing. This part of the prospectus is, like the others, provisional. It can change. In the course of your research you may even find yourself turning one hundred eighty degrees against your original hypothesis. In order to turn against your own hypothesis, however, you must have first formulated that hypothesis. More often than we might expect, we initially arrive at our conclusions only vaguely aware of the reasoning that brought us from our premises to those conclusions. While we may “sense” or “feel” the power of our own argument, others have no access to our intuitions. And so to convince them, we must make our thinking explicit. A happy side effect of this is that this forces us to subject our own thinking to critical review and scrutinize it directly for flaws. Moreover, the more deeply we engage a topic, the more we assimilate knowledge and perspectives accessible only to other experts, and the less transparent our logic and thinking becomes to others. Saying a few words in the prospectus about why someone should buy your argument can go a long way toward clarifying your thinking, and enable you to improve both your logic and the presentation of your argument.

Your prospectus should include a preliminary outline of the structure of the thesis. It should indicate the number of chapters the thesis will consist of, describe the contents of each chapter in a few sentences, and show how the chapters will hang together to present a coherent argument. Most theses will consist of three, perhaps four, chapters plus a short introduction and conclusion. A typical chapter would be around twenty pages in length. You are always free to change the structure of the thesis if you wish later and as many times as you feel necessary. The point of producing an outline at this point is not to settle points of mechanics such as the number of chapters or determine a final table of contents but rather to prod you into thinking about the structure of your argument as a whole.

Finally, your prospectus should include a preliminary bibliography of books and articles. The list need not be extensive, just sufficiently long to demonstrate that you have identified a body of scholarship to which your research responds and accessible sources of evidence. In most cases, about ten books or articles should be sufficient. The extent of the final bibliography will depend on the nature of the thesis, but generally should be substantially larger.

NES is an interdisciplinary department defined by its subject matter. It therefore places no restrictions on the methods or mix of methods that you might use. The question you pursue should determine your method. In some cases numerous methods might be applicable, although here, too, one should be wary of being too ambitious. You should seek guidance from your advisor on your methodology. Methods used in NES in recent years include historical process tracing, textual analysis and hermeneutics, comparative case studies, oral interviews, thick description, and basic quantitative analysis.

Balance is the key to research. You should expect to spend a considerable number of hours gathering, reading, analyzing, and poring over your sources. The conduct of original research is labor intensive. You certainly do not want to skimp on research. Cursory efforts to glean information from the surface reveal themselves even in good writing. At the same time, your time is limited, and you must guard against letting yourself get overwhelmed, lost, or seduced while conducting research. Avoiding the third can be a challenge. Research for most scholars is comparatively painless, even fun. Discovering new facts, ideas, insights, and perspectives can be exhilarating. The danger, however, is that writing is not always so exhilarating and typically is more painful. Be wary, therefore, of the temptation to procrastinate on writing by digging a little bit deeper or extending your research a little bit wider. A precise and properly framed question is the surest guide to navigating between the Scylla of scant research and the Charybdis of excessive research.

There is no single or best way to write a thesis. Ultimately, it depends upon a range of highly individual factors, including the state of your knowledge, the availability of sources, and the exigencies of commitments outside of your thesis. The seemingly most logical and most straightforward way to approach the writing of a thesis would be to research and write each chapter in serial, devoting an equal number of weeks to each and reserving the final weeks to revise and tighten up the various parts. This would undoubtedly be an efficient path to completing a thesis, but few, if any, theses are actually produced in this manner. Too many theses, however, are produced in precisely the opposite manner: written in a mad dash in the final weeks right before the due date. This practice you absolutely want to avoid.

The key to avoiding this practice is simple: start writing early. Alas, simple does not mean easy. Procrastination, by contrast, is all too easy. For many, perhaps most people (including professionals), writing is unpleasant, and it can be agonizing. Thinking carefully and deliberately is hard work and staring at a blank screen is intimidating. The process of writing inevitably reveals gaps in our logic and holes in our research. Facing up to these shortcomings is unpleasant. Perhaps the most common failing of students is to put off the process of writing for as long as possible.

The good news here is that writing does get easier with practice, and that it is the start of the process that is most torturous. In this sense, writing is not unlike jumping into the cold ocean or a cold lake for a swim. The anticipation and initial entry are the worst parts. As you grow acclimated you cease to notice the cold and actually begin to enjoy the process.

Thus another benefit of the prospectus is that it makes you put your thoughts on paper and get started writing in the fall. After the prospectus, the next hard date on the NES calendar is that of the submission of the final thesis. You are urged to submit a draft of the thesis to you advisor by its due date but you are not required to do so. In other words, from November through April you will be free to research and write your thesis as you deem most appropriate. You advisor can guide you, but executing your plan of research and writing is your responsibility. Hence the term “independent research.”

For reasons noted above, there can be no standard writing schedule for senior theses. Nonetheless, four general suggestions can be offered. One is that by the end of December you should have completed a draft of one chapter. It need not be—indeed almost certainly cannot be—refined. But by committing a good chunk of your argument to paper, even if in very rough form, earlier rather than later, you will be far better able to recalibrate your research and schedule as appropriate.

The second suggestion is that you should not start by trying to write the introduction. Indeed, the introduction will almost always be the last section of the thesis that you write. As you will discover through the process of research and writing, your initial assumptions and expectations will be confounded, and you will change them. It is only upon completing the thesis as a whole that you comprehend fully what you have accomplished. Only then can you write a proper introduction that lays out your hypothesis and the structure of your argument with a description of the contents of each chapter.

The third suggestion is that you start writing on whatever point or issue you feel most eager to discuss. In other words, you do not need to start by writing chapter one. It is perfectly legitimate to begin by taking up a question that you project will be covered in the third chapter. Again, the essential thing is to start writing and to start building your argument. If you discover that your argument is moving away from your planned outline, adjust your outline.

A fourth suggestion is to resist the urge to pour into your writing all the details, facts, and information you have accumulated. In the course of your research, you will collect vastly more information than you can possibly use in your writing. Excess detail, even if interesting, only clogs your writing and distracts the reader. Keep the emphasis throughout on your argument. If you have something to say that does not bear directly on the main points of your argument, leave it out.

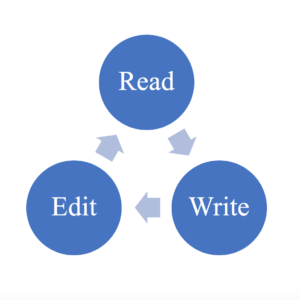

Revision is critical to effective writing. Before submitting any draft to your advisor, be sure to have read it through at least once, preferably twice. Submitting unrevised drafts wastes your time and that of your advisor. It will create a poor impression if reading your draft requires your advisor to struggle to follow your train of thought and unpack one turgid sentence after another. As you read your own work, you should be on the lookout, of course, for typos and grammatical errors, but in the early stages of revision pay especially close attention to the development and presentation of your argument. Above all, strive for clarity. This includes improving the style of your writing by cutting convoluted sentences and purging passive voice constructions that hide rather than show, as well as paying close attention to the development and presentation of your argument.

Once you are confident that the structure and content of your chapters and of the thesis as a whole are sound, you should turn to copyediting. Prior to submitting your thesis, you should proofread it very, very carefully, looking for all manner of mechanical errors. Although flawless copyediting will not turn a mediocre thesis into an outstanding one, sloppy copyediting—incomplete sentences, missing verbs, repeated instances of pronoun-noun agreement, etc.—will mar an otherwise excellent thesis.

Proofreading may not be intellectually demanding, but it does require concentration and attention to detail. This is especially true when you proofread your own writing. Due to your intimate familiarity with the text, you are prone to overlook missing words and other errors by subconsciously substituting what should be there for what actually is, or is not, there in reality. Some ways around this problem are to slowly read the text aloud to yourself or to read it in reverse, from back to front.

The best way to check your work is to have a second or third set of eyes go over your text not only to look for mechanical errors but also to give you feedback on the content and style of your writing. Agreeing with a friend or two to read each other’s drafts is an excellent way to improve the appearance and the content of your writing.

Thesis Writing Support

The Princeton Writing Program and its team of graduate Fellows offers a variety of support for Senior Thesis writers. Opportunities include workshop, peer review groups, and the popular boot camp series.

- Title page : See the example in the appendices.

- Signature : On the last page of the text you need to print the statement, “This thesis represents my own work in accordance with university regulations,” and sign it on each copy.

- ToC : A table of contents listing the title and page number of each chapter should follow the title page. On a page preceding the table of contents, you may wish to acknowledge any special assistance or support that you received in writing your thesis.

- Font : Popular fonts such as Times New Roman, Calibri, Cambria, etc., are the most effective, but there is no rule excluding less common fonts. Do not, however, use a cursive or all-bold font, and avoid fonts that are decorative but hard to read.

- Length : A thesis in NES should normally run between 70 and 100 pages. If you need more space, and your advisor agrees, you may exceed 100 pages, but such instances should be rare.

- If short, from Western languages, with Roman alphabets, include the original language quotation in either the main body of the thesis or in the notes.

- If short, from Near Eastern languages, include the original language being translated within the body of the text or in the notes. You may use the script proper to the language, or transliteration. See also point (13).

- If long, append a copy of the original language text (i.e., it should be bound in with the thesis).

- In transliteration, you are best advised to follow the practice of the International Journal of Middle East Studies , but you may choose another system. Whatever system you choose, be sure to be CONSISTENT and PRECISE.

- Foreign Names and words well known in English may be spelled in their commonly known forms (e.g., sheikh, pasha, ulema, etc.). Be consistent.

- Margins : Leave adequate margins for binding purposes of approximately 1 and 1/4" on the left side and 3/4" on the right side of the page. Number all pages, including endnote pages, consecutively.

- Style : In matters of style, when in doubt, follow the Modern Language Association Style Sheet (available at the bookstore). Be consistent.

- In annotating, even if you have not made a direct quotation but are paraphrasing, give the reference.

- If the annotations appear as endnotes, they should be double-spaced; if they appear as footnotes, they may be single-spaced. It is preferable that long quotations be double-spaced, especially if the quotation is a translation.

- Paper and Printing : Theses must be printed on only one side of standard size (8.5 x 11) paper. The normal 20 lb. printing paper is fine.