Honors Theses

What this handout is about.

Writing a senior honors thesis, or any major research essay, can seem daunting at first. A thesis requires a reflective, multi-stage writing process. This handout will walk you through those stages. It is targeted at students in the humanities and social sciences, since their theses tend to involve more writing than projects in the hard sciences. Yet all thesis writers may find the organizational strategies helpful.

Introduction

What is an honors thesis.

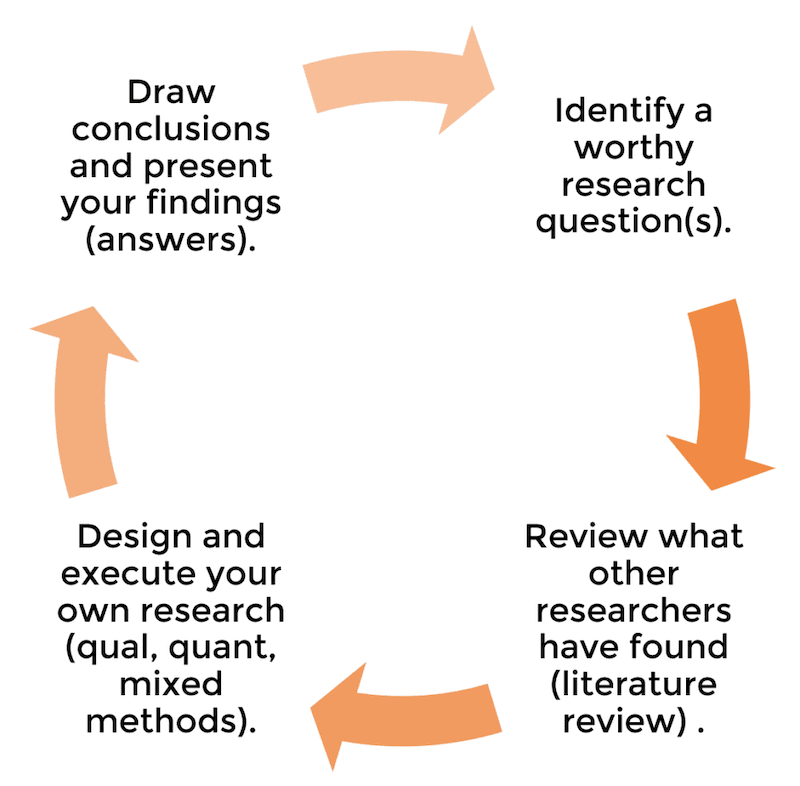

That depends quite a bit on your field of study. However, all honors theses have at least two things in common:

- They are based on students’ original research.

- They take the form of a written manuscript, which presents the findings of that research. In the humanities, theses average 50-75 pages in length and consist of two or more chapters. In the social sciences, the manuscript may be shorter, depending on whether the project involves more quantitative than qualitative research. In the hard sciences, the manuscript may be shorter still, often taking the form of a sophisticated laboratory report.

Who can write an honors thesis?

In general, students who are at the end of their junior year, have an overall 3.2 GPA, and meet their departmental requirements can write a senior thesis. For information about your eligibility, contact:

- UNC Honors Program

- Your departmental administrators of undergraduate studies/honors

Why write an honors thesis?

Satisfy your intellectual curiosity This is the most compelling reason to write a thesis. Whether it’s the short stories of Flannery O’Connor or the challenges of urban poverty, you’ve studied topics in college that really piqued your interest. Now’s your chance to follow your passions, explore further, and contribute some original ideas and research in your field.

Develop transferable skills Whether you choose to stay in your field of study or not, the process of developing and crafting a feasible research project will hone skills that will serve you well in almost any future job. After all, most jobs require some form of problem solving and oral and written communication. Writing an honors thesis requires that you:

- ask smart questions

- acquire the investigative instincts needed to find answers

- navigate libraries, laboratories, archives, databases, and other research venues

- develop the flexibility to redirect your research if your initial plan flops

- master the art of time management

- hone your argumentation skills

- organize a lengthy piece of writing

- polish your oral communication skills by presenting and defending your project to faculty and peers

Work closely with faculty mentors At large research universities like Carolina, you’ve likely taken classes where you barely got to know your instructor. Writing a thesis offers the opportunity to work one-on-one with a with faculty adviser. Such mentors can enrich your intellectual development and later serve as invaluable references for graduate school and employment.

Open windows into future professions An honors thesis will give you a taste of what it’s like to do research in your field. Even if you’re a sociology major, you may not really know what it’s like to be a sociologist. Writing a sociology thesis would open a window into that world. It also might help you decide whether to pursue that field in graduate school or in your future career.

How do you write an honors thesis?

Get an idea of what’s expected.

It’s a good idea to review some of the honors theses other students have submitted to get a sense of what an honors thesis might look like and what kinds of things might be appropriate topics. Look for examples from the previous year in the Carolina Digital Repository. You may also be able to find past theses collected in your major department or at the North Carolina Collection in Wilson Library. Pay special attention to theses written by students who share your major.

Choose a topic

Ideally, you should start thinking about topics early in your junior year, so you can begin your research and writing quickly during your senior year. (Many departments require that you submit a proposal for an honors thesis project during the spring of your junior year.)

How should you choose a topic?

- Read widely in the fields that interest you. Make a habit of browsing professional journals to survey the “hot” areas of research and to familiarize yourself with your field’s stylistic conventions. (You’ll find the most recent issues of the major professional journals in the periodicals reading room on the first floor of Davis Library).

- Set up appointments to talk with faculty in your field. This is a good idea, since you’ll eventually need to select an advisor and a second reader. Faculty also can help you start narrowing down potential topics.

- Look at honors theses from the past. The North Carolina Collection in Wilson Library holds UNC honors theses. To get a sense of the typical scope of a thesis, take a look at a sampling from your field.

What makes a good topic?

- It’s fascinating. Above all, choose something that grips your imagination. If you don’t, the chances are good that you’ll struggle to finish.

- It’s doable. Even if a topic interests you, it won’t work out unless you have access to the materials you need to research it. Also be sure that your topic is narrow enough. Let’s take an example: Say you’re interested in the efforts to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s and early 1980s. That’s a big topic that probably can’t be adequately covered in a single thesis. You need to find a case study within that larger topic. For example, maybe you’re particularly interested in the states that did not ratify the ERA. Of those states, perhaps you’ll select North Carolina, since you’ll have ready access to local research materials. And maybe you want to focus primarily on the ERA’s opponents. Beyond that, maybe you’re particularly interested in female opponents of the ERA. Now you’ve got a much more manageable topic: Women in North Carolina Who Opposed the ERA in the 1970s and 1980s.

- It contains a question. There’s a big difference between having a topic and having a guiding research question. Taking the above topic, perhaps your main question is: Why did some women in North Carolina oppose the ERA? You will, of course, generate other questions: Who were the most outspoken opponents? White women? Middle-class women? How did they oppose the ERA? Public protests? Legislative petitions? etc. etc. Yet it’s good to start with a guiding question that will focus your research.

Goal-setting and time management

The senior year is an exceptionally busy time for college students. In addition to the usual load of courses and jobs, seniors have the daunting task of applying for jobs and/or graduate school. These demands are angst producing and time consuming If that scenario sounds familiar, don’t panic! Do start strategizing about how to make a time for your thesis. You may need to take a lighter course load or eliminate extracurricular activities. Even if the thesis is the only thing on your plate, you still need to make a systematic schedule for yourself. Most departments require that you take a class that guides you through the honors project, so deadlines likely will be set for you. Still, you should set your own goals for meeting those deadlines. Here are a few suggestions for goal setting and time management:

Start early. Keep in mind that many departments will require that you turn in your thesis sometime in early April, so don’t count on having the entire spring semester to finish your work. Ideally, you’ll start the research process the semester or summer before your senior year so that the writing process can begin early in the fall. Some goal-setting will be done for you if you are taking a required class that guides you through the honors project. But any substantive research project requires a clear timetable.

Set clear goals in making a timetable. Find out the final deadline for turning in your project to your department. Working backwards from that deadline, figure out how much time you can allow for the various stages of production.

Here is a sample timetable. Use it, however, with two caveats in mind:

- The timetable for your thesis might look very different depending on your departmental requirements.

- You may not wish to proceed through these stages in a linear fashion. You may want to revise chapter one before you write chapter two. Or you might want to write your introduction last, not first. This sample is designed simply to help you start thinking about how to customize your own schedule.

Sample timetable

| Early exploratory research and brainstorming | Junior Year |

| Basic statement of topic; line up with advisor | End of Junior Year |

| Completing the bulk of primary and secondary research | Summer / Early Fall |

| Introduction Draft | September |

| Chapter One Draft | October |

| Chapter Two Draft | November |

| Chapter Three Draft | December |

| Conclusion Draft | January |

| Revising | February-March |

| Formatting and Final Touches | Early April |

| Presentation and Defense | Mid-Late April |

Avoid falling into the trap of procrastination. Once you’ve set goals for yourself, stick to them! For some tips on how to do this, see our handout on procrastination .

Consistent production

It’s a good idea to try to squeeze in a bit of thesis work every day—even if it’s just fifteen minutes of journaling or brainstorming about your topic. Or maybe you’ll spend that fifteen minutes taking notes on a book. The important thing is to accomplish a bit of active production (i.e., putting words on paper) for your thesis every day. That way, you develop good writing habits that will help you keep your project moving forward.

Make yourself accountable to someone other than yourself

Since most of you will be taking a required thesis seminar, you will have deadlines. Yet you might want to form a writing group or enlist a peer reader, some person or people who can help you stick to your goals. Moreover, if your advisor encourages you to work mostly independently, don’t be afraid to ask them to set up periodic meetings at which you’ll turn in installments of your project.

Brainstorming and freewriting

One of the biggest challenges of a lengthy writing project is keeping the creative juices flowing. Here’s where freewriting can help. Try keeping a small notebook handy where you jot down stray ideas that pop into your head. Or schedule time to freewrite. You may find that such exercises “free” you up to articulate your argument and generate new ideas. Here are some questions to stimulate freewriting.

Questions for basic brainstorming at the beginning of your project:

- What do I already know about this topic?

- Why do I care about this topic?

- Why is this topic important to people other than myself

- What more do I want to learn about this topic?

- What is the main question that I am trying to answer?

- Where can I look for additional information?

- Who is my audience and how can I reach them?

- How will my work inform my larger field of study?

- What’s the main goal of my research project?

Questions for reflection throughout your project:

- What’s my main argument? How has it changed since I began the project?

- What’s the most important evidence that I have in support of my “big point”?

- What questions do my sources not answer?

- How does my case study inform or challenge my field writ large?

- Does my project reinforce or contradict noted scholars in my field? How?

- What is the most surprising finding of my research?

- What is the most frustrating part of this project?

- What is the most rewarding part of this project?

- What will be my work’s most important contribution?

Research and note-taking

In conducting research, you will need to find both primary sources (“firsthand” sources that come directly from the period/events/people you are studying) and secondary sources (“secondhand” sources that are filtered through the interpretations of experts in your field.) The nature of your research will vary tremendously, depending on what field you’re in. For some general suggestions on finding sources, consult the UNC Libraries tutorials . Whatever the exact nature of the research you’re conducting, you’ll be taking lots of notes and should reflect critically on how you do that. Too often it’s assumed that the research phase of a project involves very little substantive writing (i.e., writing that involves thinking). We sit down with our research materials and plunder them for basic facts and useful quotations. That mechanical type of information-recording is important. But a more thoughtful type of writing and analytical thinking is also essential at this stage. Some general guidelines for note-taking:

First of all, develop a research system. There are lots of ways to take and organize your notes. Whether you choose to use note cards, computer databases, or notebooks, follow two cardinal rules:

- Make careful distinctions between direct quotations and your paraphrasing! This is critical if you want to be sure to avoid accidentally plagiarizing someone else’s work. For more on this, see our handout on plagiarism .

- Record full citations for each source. Don’t get lazy here! It will be far more difficult to find the proper citation later than to write it down now.

Keeping those rules in mind, here’s a template for the types of information that your note cards/legal pad sheets/computer files should include for each of your sources:

Abbreviated subject heading: Include two or three words to remind you of what this sources is about (this shorthand categorization is essential for the later sorting of your sources).

Complete bibliographic citation:

- author, title, publisher, copyright date, and page numbers for published works

- box and folder numbers and document descriptions for archival sources

- complete web page title, author, address, and date accessed for online sources

Notes on facts, quotations, and arguments: Depending on the type of source you’re using, the content of your notes will vary. If, for example, you’re using US Census data, then you’ll mainly be writing down statistics and numbers. If you’re looking at someone else’s diary, you might jot down a number of quotations that illustrate the subject’s feelings and perspectives. If you’re looking at a secondary source, you’ll want to make note not just of factual information provided by the author but also of their key arguments.

Your interpretation of the source: This is the most important part of note-taking. Don’t just record facts. Go ahead and take a stab at interpreting them. As historians Jacques Barzun and Henry F. Graff insist, “A note is a thought.” So what do these thoughts entail? Ask yourself questions about the context and significance of each source.

Interpreting the context of a source:

- Who wrote/created the source?

- When, and under what circumstances, was it written/created?

- Why was it written/created? What was the agenda behind the source?

- How was it written/created?

- If using a secondary source: How does it speak to other scholarship in the field?

Interpreting the significance of a source:

- How does this source answer (or complicate) my guiding research questions?

- Does it pose new questions for my project? What are they?

- Does it challenge my fundamental argument? If so, how?

- Given the source’s context, how reliable is it?

You don’t need to answer all of these questions for each source, but you should set a goal of engaging in at least one or two sentences of thoughtful, interpretative writing for each source. If you do so, you’ll make much easier the next task that awaits you: drafting.

The dread of drafting

Why do we often dread drafting? We dread drafting because it requires synthesis, one of the more difficult forms of thinking and interpretation. If you’ve been free-writing and taking thoughtful notes during the research phase of your project, then the drafting should be far less painful. Here are some tips on how to get started:

Sort your “evidence” or research into analytical categories:

- Some people file note cards into categories.

- The technologically-oriented among us take notes using computer database programs that have built-in sorting mechanisms.

- Others cut and paste evidence into detailed outlines on their computer.

- Still others stack books, notes, and photocopies into topically-arranged piles.There is not a single right way, but this step—in some form or fashion—is essential!

If you’ve been forcing yourself to put subject headings on your notes as you go along, you’ll have generated a number of important analytical categories. Now, you need to refine those categories and sort your evidence. Everyone has a different “sorting style.”

Formulate working arguments for your entire thesis and individual chapters. Once you’ve sorted your evidence, you need to spend some time thinking about your project’s “big picture.” You need to be able to answer two questions in specific terms:

- What is the overall argument of my thesis?

- What are the sub-arguments of each chapter and how do they relate to my main argument?

Keep in mind that “working arguments” may change after you start writing. But a senior thesis is big and potentially unwieldy. If you leave this business of argument to chance, you may end up with a tangle of ideas. See our handout on arguments and handout on thesis statements for some general advice on formulating arguments.

Divide your thesis into manageable chunks. The surest road to frustration at this stage is getting obsessed with the big picture. What? Didn’t we just say that you needed to focus on the big picture? Yes, by all means, yes. You do need to focus on the big picture in order to get a conceptual handle on your project, but you also need to break your thesis down into manageable chunks of writing. For example, take a small stack of note cards and flesh them out on paper. Or write through one point on a chapter outline. Those small bits of prose will add up quickly.

Just start! Even if it’s not at the beginning. Are you having trouble writing those first few pages of your chapter? Sometimes the introduction is the toughest place to start. You should have a rough idea of your overall argument before you begin writing one of the main chapters, but you might find it easier to start writing in the middle of a chapter of somewhere other than word one. Grab hold where you evidence is strongest and your ideas are clearest.

Keep up the momentum! Assuming the first draft won’t be your last draft, try to get your thoughts on paper without spending too much time fussing over minor stylistic concerns. At the drafting stage, it’s all about getting those ideas on paper. Once that task is done, you can turn your attention to revising.

Peter Elbow, in Writing With Power, suggests that writing is difficult because it requires two conflicting tasks: creating and criticizing. While these two tasks are intimately intertwined, the drafting stage focuses on creating, while revising requires criticizing. If you leave your revising to the last minute, then you’ve left out a crucial stage of the writing process. See our handout for some general tips on revising . The challenges of revising an honors thesis may include:

Juggling feedback from multiple readers

A senior thesis may mark the first time that you have had to juggle feedback from a wide range of readers:

- your adviser

- a second (and sometimes third) faculty reader

- the professor and students in your honors thesis seminar

You may feel overwhelmed by the prospect of incorporating all this advice. Keep in mind that some advice is better than others. You will probably want to take most seriously the advice of your adviser since they carry the most weight in giving your project a stamp of approval. But sometimes your adviser may give you more advice than you can digest. If so, don’t be afraid to approach them—in a polite and cooperative spirit, of course—and ask for some help in prioritizing that advice. See our handout for some tips on getting and receiving feedback .

Refining your argument

It’s especially easy in writing a lengthy work to lose sight of your main ideas. So spend some time after you’ve drafted to go back and clarify your overall argument and the individual chapter arguments and make sure they match the evidence you present.

Organizing and reorganizing

Again, in writing a 50-75 page thesis, things can get jumbled. You may find it particularly helpful to make a “reverse outline” of each of your chapters. That will help you to see the big sections in your work and move things around so there’s a logical flow of ideas. See our handout on organization for more organizational suggestions and tips on making a reverse outline

Plugging in holes in your evidence

It’s unlikely that you anticipated everything you needed to look up before you drafted your thesis. Save some time at the revising stage to plug in the holes in your research. Make sure that you have both primary and secondary evidence to support and contextualize your main ideas.

Saving time for the small stuff

Even though your argument, evidence, and organization are most important, leave plenty of time to polish your prose. At this point, you’ve spent a very long time on your thesis. Don’t let minor blemishes (misspellings and incorrect grammar) distract your readers!

Formatting and final touches

You’re almost done! You’ve researched, drafted, and revised your thesis; now you need to take care of those pesky little formatting matters. An honors thesis should replicate—on a smaller scale—the appearance of a dissertation or master’s thesis. So, you need to include the “trappings” of a formal piece of academic work. For specific questions on formatting matters, check with your department to see if it has a style guide that you should use. For general formatting guidelines, consult the Graduate School’s Guide to Dissertations and Theses . Keeping in mind the caveat that you should always check with your department first about its stylistic guidelines, here’s a brief overview of the final “finishing touches” that you’ll need to put on your honors thesis:

- Honors Thesis

- Name of Department

- University of North Carolina

- These parts of the thesis will vary in format depending on whether your discipline uses MLA, APA, CBE, or Chicago (also known in its shortened version as Turabian) style. Whichever style you’re using, stick to the rules and be consistent. It might be helpful to buy an appropriate style guide. Or consult the UNC LibrariesYear Citations/footnotes and works cited/reference pages citation tutorial

- In addition, in the bottom left corner, you need to leave space for your adviser and faculty readers to sign their names. For example:

Approved by: _____________________

Adviser: Prof. Jane Doe

- This is not a required component of an honors thesis. However, if you want to thank particular librarians, archivists, interviewees, and advisers, here’s the place to do it. You should include an acknowledgments page if you received a grant from the university or an outside agency that supported your research. It’s a good idea to acknowledge folks who helped you with a major project, but do not feel the need to go overboard with copious and flowery expressions of gratitude. You can—and should—always write additional thank-you notes to people who gave you assistance.

- Formatted much like the table of contents.

- You’ll need to save this until the end, because it needs to reflect your final pagination. Once you’ve made all changes to the body of the thesis, then type up your table of contents with the titles of each section aligned on the left and the page numbers on which those sections begin flush right.

- Each page of your thesis needs a number, although not all page numbers are displayed. All pages that precede the first page of the main text (i.e., your introduction or chapter one) are numbered with small roman numerals (i, ii, iii, iv, v, etc.). All pages thereafter use Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.).

- Your text should be double spaced (except, in some cases, long excerpts of quoted material), in a 12 point font and a standard font style (e.g., Times New Roman). An honors thesis isn’t the place to experiment with funky fonts—they won’t enhance your work, they’ll only distract your readers.

- In general, leave a one-inch inch margin on all sides. However, for the copy of your thesis that will be bound by the library, you need to leave a 1.25-inch margin on the left.

How do I defend my honors thesis?

Graciously, enthusiastically, and confidently. The term defense is scary and misleading—it conjures up images of a military exercise or an athletic maneuver. An academic defense ideally shouldn’t be a combative scene but a congenial conversation about the work’s merits and weaknesses. That said, the defense probably won’t be like the average conversation that you have with your friends. You’ll be the center of attention. And you may get some challenging questions. Thus, it’s a good idea to spend some time preparing yourself. First of all, you’ll want to prepare 5-10 minutes of opening comments. Here’s a good time to preempt some criticisms by frankly acknowledging what you think your work’s greatest strengths and weaknesses are. Then you may be asked some typical questions:

- What is the main argument of your thesis?

- How does it fit in with the work of Ms. Famous Scholar?

- Have you read the work of Mr. Important Author?

NOTE: Don’t get too flustered if you haven’t! Most scholars have their favorite authors and books and may bring one or more of them up, even if the person or book is only tangentially related to the topic at hand. Should you get this question, answer honestly and simply jot down the title or the author’s name for future reference. No one expects you to have read everything that’s out there.

- Why did you choose this particular case study to explore your topic?

- If you were to expand this project in graduate school, how would you do so?

Should you get some biting criticism of your work, try not to get defensive. Yes, this is a defense, but you’ll probably only fan the flames if you lose your cool. Keep in mind that all academic work has flaws or weaknesses, and you can be sure that your professors have received criticisms of their own work. It’s part of the academic enterprise. Accept criticism graciously and learn from it. If you receive criticism that is unfair, stand up for yourself confidently, but in a good spirit. Above all, try to have fun! A defense is a rare opportunity to have eminent scholars in your field focus on YOU and your ideas and work. And the defense marks the end of a long and arduous journey. You have every right to be proud of your accomplishments!

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Atchity, Kenneth. 1986. A Writer’s Time: A Guide to the Creative Process from Vision Through Revision . New York: W.W. Norton.

Barzun, Jacques, and Henry F. Graff. 2012. The Modern Researcher , 6th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Elbow, Peter. 1998. Writing With Power: Techniques for Mastering the Writing Process . New York: Oxford University Press.

Graff, Gerald, and Cathy Birkenstein. 2014. “They Say/I Say”: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing , 3rd ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

Lamott, Anne. 1994. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life . New York: Pantheon.

Lasch, Christopher. 2002. Plain Style: A Guide to Written English. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Turabian, Kate. 2018. A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, Dissertations , 9th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Writing an Honors Thesis

An Honors Thesis is a substantial piece of independent research that an undergraduate carries out over two semesters. Students writing Honors Theses take PHIL 691H and 692H, in two different semesters. What follows answers all the most common questions about Honors Theses in Philosophy.

All necessary forms are fillable and downloadable.

Honors Thesis Application

Honors Thesis Contract

Honors Thesis Learning Contract

Who can write an Honors Thesis in Philosophy?

Any Philosophy major who has a total, cumulative GPA of at least 3.3 and a GPA of at least 3.5 (with a maximum of one course with a PS grade) among their PHIL courses can in principle write an Honors Thesis. In addition, students need to satisfy a set of specific pre-requisites, as outlined below.

What are the pre-requisites for an Honors Thesis in Philosophy?

The requirements for writing an Honors Thesis in Philosophy include

- having taken at least five PHIL courses, including two numbered higher than 299;

- having a total PHIL GPA of at least 3.5 (with a maximum of one course with a PS grade); and

- having done one of the following four things:

- taken and passed PHIL 397;

- successfully completed an Honors Contract associated with a PHIL course;

- received an A or A- in a 300-level course in the same area of philosophy as the proposed thesis ; or

- taken and passed a 400-level course in the same area of philosophy as the proposed thesis .

When should I get started?

You should get started with the application process and search for a prospective advisor the semester before you plan to start writing your thesis – that is, the semester before the one in which you want to take PHIL 691H.

Often, though not always, PHIL 691H and 692H are taken in the fall and spring semesters of the senior year, respectively. It is also possible to start earlier and take 691H in the spring semester of the junior year and PHIL 692H in the fall of the senior year. Starting earlier has some important advantages. One is that it means you will finish your thesis in time to use it as a writing sample, should you decide to apply to graduate school. Another is that it avoids a mad rush near the very end of your last semester.

How do I get started?

Step 1: fill out the honors thesis application.

The first thing you need to do is fill out an Honors Thesis Application and submit it to the Director of Undergraduate Studies (DUS) for their approval.

Step 2: Find an Honors Thesis Advisor with the help of the DUS

Once you have been approved to write an Honors Thesis, you will consult with the DUS about the project that you have in mind and about which faculty member would be an appropriate advisor for your thesis. It is recommended that you reach out informally to prospective advisors to talk about their availability and interest in your project ahead of time, and that you include those suggestions in your application, but it is not until your application has been approved that the DUS will officially invite the faculty member of your choice to serve as your advisor. You will be included in this correspondence and will receive written confirmation from your prospective advisor.

Agreeing to be the advisor for an Honors Thesis is a major commitment, so bear in mind that there is a real possibility that someone asked to be your advisor will say no. Unfortunately, if we cannot find an advisor, you cannot write an Honors Thesis.

Step 3: Fill out the required paperwork needed to register for PHIL 691H

Finally, preferably one or two weeks before the start of classes (or as soon as you have secured the commitment of a faculty advisor), you need to fill out an Honors Thesis Contract and an Honors Thesis Learning Contract , get them both signed by your advisor, and email them to the DUS.

Once the DUS approves both of these forms, they’ll get you registered for PHIL 691H. All of this should take place no later than the 5th day of classes in any given semester (preferably sooner).

What happens when I take PHIL 691H and PHIL 692H?

PHIL 691H and PHIL 692H are the course numbers that you sign up for to get credit for working on an Honors Thesis. These classes have official meeting times and places. In the case of PHIL 691H , those are a mere formality: You will meet with your advisor at times you both agree upon. But in the case of PHIL 692H , they are not a mere formality: The class will actually meet as a group, at least for the first few weeks of the semester (please see below).

When you take PHIL 691H, you should meet with your advisor during the first 5 days of classes and, if you have not done so already, fill out an Honors Thesis Learning Contract and turn in to the Director of Undergraduate Studies (DUS) . This Contract will serve as your course syllabus and must be turned in and approved no later than the 5th day of classes in any given semester (preferably sooner). Once the DUS approves your Honors Thesis Learning Contract, they’ll get you registered for PHIL 691H.

Over the course of the semester, you will meet regularly with your advisor. By the last day of classes, you must turn in a 10-page paper on your thesis topic; this can turn out to be part of your final thesis, but it doesn’t have to. In order to continue working on an Honors Thesis the following semester, this paper must show promise of your ability to complete one, in the opinion of your advisor. Your advisor should assign you a grade of “ SP ” at the conclusion of the semester, signifying “satisfactory progress” (so you can move on to PHIL 692H). Please see page 3 of this document for more information.

When you take PHIL 692H, you’ll still need to work with your advisor to fill out an Honors Thesis Learning Contract . This Contract will serve as your course syllabus and must be turned in to and approved by the DUS no later than the 5th day of classes in any given semester (preferably sooner).

Once the DUS approves your Honors Thesis Learning Contract, they’ll get you registered for PHIL 692H.

At the end of the second semester of senior honors thesis work (PHIL 692H), your advisor should assign you a permanent letter grade. Your advisor should also change your PHIL 691H grade from “ SP ” to a permanent letter grade. Please see page 3 of this document for more information.

The Graduate Course Option

If you and your advisor agree, you may exercise the Graduate Course Option. If you do this, then during the semester when you are enrolled in either PHIL 691H or PHIL 692H, you will attend and do the work for a graduate level PHIL course. (You won’t be officially enrolled in that course.) A paper you write for this course will be the basis for your Honors Thesis. If you exercise this option, then you will be excused from the other requirements of the thesis course (either 691H or 692H) that you are taking that semester.

Who can be my advisor?

Any faculty member on a longer-than-one-year contract in the Department of Philosophy may serve as your honors thesis advisor. You will eventually form a committee of three professors, of which one can be from outside the Department. But your advisor must have an appointment in the Philosophy Department. Graduate Students are not eligible to advise Honors Theses.

Who should be my advisor?

Any faculty member on a longer-than-one-year contract in the Department of Philosophy may serve as your honors thesis advisor. It makes most sense to ask a professor who already knows you from having had you as a student in a class. In some cases, though, this is either not possible, or else there is someone on the faculty who is an expert on the topic you want to write about, but from whom you have not taken a class. Information about which faculty members are especially qualified to advise thesis projects in particular areas of philosophy can be found here .

What about the defense?

You and your advisor should compose a committee of three professors (including the advisor) who will examine you and your thesis. Once the committee is composed, you will need to schedule an oral examination, a.k.a. a defense. You should take the initiative here, communicating with all members of your committee in an effort to find a block of time (a little over an hour) when all three of you can meet. The thesis must be defended by a deadline , set by Honors Carolina , which is usually a couple of weeks before the end of classes. Students are required to upload the final version of their thesis to the Carolina Digital Repository by the final day of class in the semester in which they complete the thesis course work and thesis defense.

What is an Honors Thesis in Philosophy like?

An Honors Thesis in Philosophy is a piece of writing in the same genre as a typical philosophy journal article. There is no specific length requirement, but 30 pages (double-spaced) is a good guideline. Some examples of successfully defended Honors The easiest way to find theses of past philosophy students is on the web in the Carolina Digital Repository . Some older, hard copies of theses are located on the bookshelf in suite 107 of Caldwell Hall. (You may ask the Director of Undergraduate Studies (DUS) , or anyone else who happens to be handy, to show you where it is!)

How does the Honors Thesis get evaluated?

The honors thesis committee will evaluate the quality and originality of your thesis as well as of your defense and then decides between the following three options:

- they may award only course credit for the thesis work if the thesis is of acceptable quality;

- they may designate that the student graduate with honors if the thesis is of a very strong quality;

- they may recommend that the student graduate with highest honors if the thesis is of exceptional quality.

As a matter of best practice, our philosophy department requires that examining committees refer all candidates for highest honors to our Undergraduate Committee chaired by the Director of Undergraduate Studies. This committee evaluates nominated projects and makes the final decision on awarding highest honors. Highest honors should be awarded only to students who have met the most rigorous standards of scholarly excellence.

Honors & Theses

The Honors Thesis: An opportunity to do innovative and in-depth research.

An honors thesis gives students the opportunity to conduct in-depth research into the areas of government that inspire them the most. Although, it’s not a requirement in the Department of Government, the honors thesis is both an academic challenge and a crowning achievement at Harvard. The faculty strongly encourages students to write an honors thesis and makes itself available as a resource to those students who do. Students work closely with the thesis advisor of their choice throughout the writing process. Approximately 30% of Government concentrators each year choose to write a thesis.

| ! |

Guide to Writing a Senior Thesis in Government

You undoubtedly have many questions about what writing a thesis entails. We have answers for you. Please read A Guide to Writing a Senior Thesis in Government , which you can download as a PDF below. If you still have questions or concerns after you have read through this document, we encourage you to reach out to the Director of Undergraduate Studies, Dr. Nara Dillon ( [email protected] ), the Assistant Director of Undergraduate Studies, Dr. Gabriel Katsh ( [email protected] ), or the Undergraduate Program Manager, Karen Kaletka ( [email protected] ).

Honours Thesis Handbook

This handbook, effective September 1, 2016 , is the course outline for PSYCH 499A/B/C (Honours Thesis) from Fall 2016 and onward.

Table of contents

- What is an honours thesis ?

- Who should do an honours thesis ?

Prerequisites for admission to PSYCH 499

Selecting a topic for the honours thesis, finding a thesis supervisor.

- Research interests of the Psychology faculty and recent honours thesis supervised

Class enrolment for PSYCH 499A/B/C

Warnings regarding a decision to discontinue psych 499.

- Course requirements for PSYCH 499A progress report and thesis reviewer nominations

- Course requirements for PSYCH 499B - oral presentation of the thesis proposal

Course requirements for PSYCH 499C - completing the thesis and submitting it for marking

Obtaining ethics clearance for research with human or animal participants, evaluation of the honours thesis, honours thesis award, annual ontario psychology undergraduate thesis conference, avoid academic offences, computing facilities, honours thesis (psych 499a/b/c), what is an honours thesis.

Psychology is a scientific approach to understanding mind and behaviour. Honours Psychology students all learn about the body of knowledge that exists in psychology as well as the scientific procedures for making new discoveries. The honours thesis course (PSYCH 499A/B/C) is an optional course for those who have a strong interest in conducting original research and wish to gain greater experience in research design, data analysis and interpretation.

Students carry out the honours thesis project under the supervision of a faculty member and present the findings in a scholarly paper. An honours thesis can be an empirical research project or more rarely a thesis of a theoretical nature. For an empirical project, the student develops a testable hypothesis and uses scientific procedures to evaluate the hypothesis. For a theoretical project, the student integrates and evaluates existing evidence to offer new interpretations and hypotheses. The difference between the two types of projects is basically the same as the difference between an article in Psychological Review or Psychological Bulletin , and an article in any of the experimental journals. A regular journal article typically reports the result of some empirical investigation and discusses its significance. A Psychological Review paper on the other hand, offers a theoretical contribution (e.g., suggesting a new theoretical approach or a way of revising an old one and showing how the new approach may be tested). A Psychological Bulletin article usually offers a review of an evaluative and integrative character, leading to conclusions and some closure about the state of the issue and future directions for research.

Students who plan to apply for admission to graduate school in psychology are typically advised to do an empirical research project for the honours thesis. Students who choose to do a theoretical paper should discuss their decision with the PSYCH 499 coordinator (see below) early in the PSYCH 499A term.

The topic of investigation for the honours thesis will be based on a combination of the student's and the supervisor's interests .

Students in year two or three who are considering whether or not they want to do an honours thesis can learn more about what is involved in doing an honours thesis by doing any of the following:

- attending an honours thesis orientation meeting. The meeting is typically the first week of classes each academic term. The official date and time of the meeting will be posted on the PSYCH 499 website .

- attending PSYCH 499B oral presentations by other students.

- reading a few of the honours thesis samples that are available online PSYCH 499 SharePoint site (site only accessible to students currently enrolled in PSYCH 499) or via our Learn shell (only available when enrolled).

In addition to the student's honours thesis supervisor, another resource is the PSYCH 499 course coordinator . The PSYCH 499 coordinator conducts the thesis orientation meeting at the start of each term and is available to discuss any course-related or supervisor-related issues with potential students and enrolled students . If students have questions or concerns regarding the procedures for doing an honours thesis that cannot be answered by their thesis supervisor, they should contact the PSYCH 499 coordinator.

The honours thesis course (PSYCH 499A/B/C) is worth 1.5 units (i.e., 3 term courses). The final numerical grade for the thesis will be recorded for each of PSYCH 499A, 499B, and 499C.

Who should I do an honours thesis?

Honours Psychology majors are not required to do an honours thesis.

Good reasons for doing an honours thesis include:

- An honours thesis is a recommended culmination of the extensive training that honours Psychology majors receive in research methods and data analysis (e.g., PSYCH 291, 292, 389, 390, 492). PSYCH 499 is a good choice for students who have a strong interest in, and commitment to, conducting original research and wish to gain greater experience in research design, data analysis and interpretation.

- An honours degree in Psychology that includes a thesis is typically required for admission to graduate programs in Psychology.

- Thesis supervisors are able to write more meaningful reference letters for students' applications for further studies, scholarships, or employment.

The prerequisites for PSYCH 499 are all of the following:

- enrolment in honours Psychology or make-up Psychology

- successful completion of PSYCH 291, 292, 391, and at least one of: PSYCH 389, 390, 483, 484

- 60% cumulative overall average

- 82% cumulative psychology average

* calendar descriptions as well as course outlines

The course prerequisites for enrolment in PSYCH 499A are strictly enforced because the courses provide essential background for success in PSYCH 499, and it is necessary to restrict the number of students enrolling in PSYCH 499. Appeals to enrol in all 3 of the following courses concurrently will not be accepted:

- Advanced research methods course (PSYCH 389, 390, 483, 484)

In addition to the above formal prerequisites, we assume that all students who are enrolling in PSYCH 499 will have completed at least 4 of the "discipline core courses" (i.e., PSYCH 207, 211, 253, 257, 261) prior to the PSYCH 499A enrolment term.

See " Class enrolment for PSYCH 499A/B/C " below for further details regarding course enrolment, and the PSYCH 499 Application for students without the course prerequisites (e.g., PSYCH average between 81%-81.9%).

The topic of the honours thesis will be based on a combination of the interests of the student and his/her thesis supervisor. One approach for selecting an honours thesis topic is for the student to first find a thesis supervisor who has similar interests to his/her own, and then for the student and the thesis supervisor to develop an honours thesis proposal which compliments the faculty member's current research. Alternatively, some students have more specific research interests and will seek an appropriate thesis supervisor. Students are advised against developing an honours thesis project in too much detail before securing a thesis supervisor.

Review some of the honours thesis titles recently supervised by our faculty members.

See research interests of individual faculty members in the next section.

Each student who enrols in PSYCH 499 must find their own supervisor for his/her honours thesis project. A thesis supervisor must be finalized by the eighth day of classes for the PSYCH 499A term.

Full-time faculty members in the UW Psychology Department, and the four Psychology faculty members at St. Jerome's are all potential thesis supervisors. Think carefully about what you want to tell faculty members about yourself before making contact (think 'foot-in-the-door'). For example, inform a potential supervisor of the following:

- for which school terms you are seeking a thesis supervisor (If not planning to do PSYCH 499 over back-to-back school terms, please explain why, e.g., co-op work term).

- why you are interested in doing an honours thesis

- the program that you are enrolled in (e.g., BA versus BSc, co-op versus regular stream)

- your year of study and target date for graduation

- when you will complete the prerequisites for enrolment in PSYCH 499A

- your cumulative overall and psychology average (highlight improvement if applicable)

- your grades for research methods and statistics courses

- your educational and career goals

- your volunteer/work experience that you have had previously and with whom

- Did you work in his/her lab as a volunteer or paid research assistant?

- Did you take a course with him/her previously?

- Have you read articles that he/she wrote?

- Do his/her interests relate to your interests for studies at the graduate level and/or future employment?

- Were you referred by someone and why?

The search for a thesis supervisor will be easier if you establish rapport during second and third year with faculty members who are potential thesis supervisors. Ways to network with faculty members include the following:

- get involved in the faculty member's lab. See ' Research experience ' on the Psychology undergraduate website for further details

- the Associate Chair for Undergraduate Affairs - currently Stephanie Denison

- faculty members who attended the school(s) you are interested in applying to in the future. See the Psychology Department's Faculty listing for details

- faculty members who have interests that relate to your future plans. See Research interests of faculty members in our department.

- faculty members whose labs you worked or volunteered in

- be an active participant in the class discussions for the advanced research methods courses (PSYCH 389, 390) and honours seminars (PSYCH 453-463).

- enrol in a directed studies course (PSYCH 480-486) where you will receive one-on-one supervision from a faculty member. See the course application form for further details

- read articles that the faculty member has written and discuss the material with him/her

- attend departmental colloquia and divisional seminars where students can engage in discussions with faculty members about the material presented. Postings appear on the right sidebar of the Psychology Department home page

You may find that some faculty members that you approach will have already committed to supervising as many honours thesis projects as they feel able to handle for a given year. Be persistent in your search for a thesis supervisor and do not feel discouraged if you need to approach several (i.e., six or eight) people.

If you are unable to obtain a thesis supervisor, please speak to the PSYCH 499 coordinator .

Faculty members other than the thesis supervisor can also be very useful resources during the course of the thesis project. Feel free to discuss your thesis work with any relevant faculty (or graduate students).

Research interests of the faculty members in the Psychology Department and recent honours theses supervised

For research interests of faculty members please refer to the "Our People" page in the main menu and click on the faculty member's name. You can sort the list by "Name" or "Area of Study". Note that faculty members may not be available to supervise honours theses during sabbatical dates indicated on the web site.

For recent honours theses supervised by individual faculty members please refer to the honours theses supervised website.

Refer to the course enrolment information/instructions on the PSYCH 499 website.

The honours thesis (PSYCH 499A/B/C) is worth 1.5 units (i.e., 3 term courses). Students may not enrol for all of PSYCH 499A/B/C in one term. Students should consult with their thesis supervisor regarding the appropriate class enrolment sequence for PSYCH 499. Students can spread the class enrolment for PSYCH 499A, 499B, and 499C over three terms beginning in the 3B term or over two terms beginning in 4A. Those choosing to do the honours thesis over two terms will enrol in PSYCH 499A/B in 4A and PSYCH 499C in 4B. Alternative sequencing (e.g., 499A/B/C over three terms) should be discussed with the thesis supervisor. Although students can start an honours thesis in any term, the Fall term is typically recommended.

Factors that students should consider when deciding which terms to enrol for PSYCH 499A/B/C:

- When will the prerequisites for PSYCH 499 be completed? For example, Honours Psych & Arts and Business Co-op students will not enrol in PSYCH 499A until the 4A term because the prerequisites for PSYCH 499 won't be completed until the 3B term.

- Will the thesis supervisor be available to supervise the project during the terms that the student proposes to enrol for PSYCH 499A/B/C (e.g., is the supervisor planning a sabbatical leave or to retire)?

- For co-op students, how will the work/school sequence interfere with the project?

- The amount of time necessary to obtain ethics clearance varies depending on the participants required and research design.

- When is the optimal timing for data collection? For example, if PSYCH 101 students will be participants for the study, one has to consider the ratio of PSYCH 101 students to researchers that are available in a given term. The Fall term is typically the best time to collect data from this population, Winter term second best, and the Spring term the poorest.

- What other responsibilities does the student have (e.g., course selections, personal circumstances) in a given term?

- The thesis supervisor requires a sufficient amount of time to get to know the student before he/she is asked to write the student reference letters (e.g., for applications for graduate school, scholarships, or employment).

Details are provided in the next 3 sections regarding the course requirements for each of PSYCH 499A, 499B, and 499C.

Students should be diligent about their responsibilities for the honours thesis. Procrastination leads to delays in firming up the research proposal, doing the oral presentation, obtaining ethics clearance, and beginning data collection. Ultimately procrastination can lead to poor quality work and/or a postponement of graduation.

Students should consult with their thesis supervisor and the Psychology undergraduate advisor before dropping any of PSYCH 499A, 499B, or 499C.

- If a student wants to drop any of PSYCH 499A, 499B, and 499C in the current term, the individual course requests are governed by the same course drop deadlines and penalties (e.g., WD and WF grades) as other courses. Refer to important dates on Quest.

- Dropping PSYCH 499B and/or PSYCH 499C in the current term does not remove PSYCH 499A or PSYCH 499B from earlier terms.

- If a student does not complete the honours thesis, any INC (incomplete) grades for PSYCH 499A/B/C will be converted to FTC (Failure to Complete = 32% in the average calculations). Further, any IP (In Progress) grades for PSYCH 499A/B/C will be converted to FTC (=32%).

- Honours students with INC and/or IP grades will be unable to graduate (e.g., with a General BA in Psych) until those grades are replaced by a final grade(s) (e.g., 32%) and the grade(s) has been factored into the average calculation. In such cases, the student must meet all graduation requirements, including overall average, Psychology average and minimum number of courses required.

- Those who want any grades (e.g., INC, IP, WD, WF, FTC, 32%) for PSYCH 499 removed from their records are advised to submit a petition to the Examinations and Standings Committee. Before doing so, they should consult with the Psychology undergraduate advisor.

Course requirements for PSYCH 499A - progress report and thesis reviewer nominations

Students should attend the honours thesis orientation meeting during the PSYCH 499A term even if they attended a meeting during second or third year. The meeting is usually the first week of classes each academic term. The official date and time will be posted on the PSYCH 499 website . At the meeting, the PSYCH 499 coordinator will describe what is involved in doing an honours thesis and answer questions. Students will also receive information regarding library resources and procedures for obtaining ethics clearance.

Students must report the name of their thesis supervisor to the PSYCH 499 course administrator in the Psychology Undergraduate Office by the eighth day of classes for the PSYCH 499A term. During the PSYCH 499A term, students must

- conduct background research on the thesis topic (e.g., formulate a research question, review relevant literature, formulate major hypotheses)

- nominate potential thesis reviewers

- submit a progress report to the PSYCH 499 coordinator .

Progress reports

Progress reports are due the last day classes for the PSYCH 499A term. The thesis supervisor must sign the progress report before it is submitted to the PSYCH 499 coordinator . Submit the progress report directly to the course coordinator's mailbox in PAS 3021A or via email, cc'ing the course administrato r and your supervisor to give confirmation that they have "signed off" on your progress report (this can pose as the signature). Students should keep a copy of their progress report because the reports will not be returned. The PSYCH 499 coordinator will contact individual students by email if there is a problem with their progress report.

The progress report should be about 5-10 pages in length and include the following information:

- a title page identifying the document as a "PSYCH 499A Progress Report", with the proposed title of the project; student's name, address, telephone number, and email address; the student's ID number, the name of the honours thesis supervisor; and the signature of the supervisor indicating that he or she has read the report and approved it;

- a statement of the general topic of the proposed research;

- a brief account of the background literature the student has read, together with a brief explanation of its relevance for the project;

- a clear statement of the research questions and/or the major hypotheses that the study will address;

- a brief statement of the further steps that will be necessary to complete (e.g., settling on a research design, etc.) before the student will be ready to submit a research proposal and do an oral presentation.

PSYCH 499A students who are not concurrently enrolled in PSYCH 499B typically do not have a fully developed research proposal by the end of the first term of PSYCH 499. The progress reports should be submitted on time and should include as much detail regarding the research proposal as possible (see next section for further details).

Some PSYCH 499A students who are not concurrently enrolled in PSYCH 499B will firm up their research proposals earlier than expected and will want to do, and are encouraged to do, the oral presentation of the research proposal in the first term of PSYCH 499 (see next section for further details). In these cases, the IP (In Progress) grade for PSYCH 499B will be applied to the academic term in which the student formally enrols for PSYCH 499B.

Students who submit progress reports will receive an IP (In Progress) grade for PSYCH 499A; those who do not will receive an INC (Incomplete) grade for PSYCH 499A. INC and IP grades for PSYCH 499 do not impact on average calculations and students with either of these grades can be considered for the Dean's honours list. However, students with INC grades are not eligible for scholarship consideration. Note that INC grades convert to FTC (failure to complete = 32%) after 70 days.

Thesis reviewer

The thesis reviewer is due by the last day of classes for the term for students who enrol in PSYCH 499A only and they are due by the end of the third week of the term for students who enrol concurrently in PSYCH 499A/B. You will work with your supervisor to decide who would be a strong reviewer and will plan this out with that reviewer. Once your reviewer is determined, please email the course administrator . The thesis reviewer’s duties will include reading the thesis proposal and attending the oral presentation in the PSYCH 499B term and reading and grading the final thesis at the end of the PSYCH 499C term.

Full-time faculty members in the UW Psychology Department and the four Psychology faculty members at St. Jerome's are all potential thesis reviewers. (Note: the student’s thesis supervisor cannot be the thesis reviewer). Students may consult with their thesis supervisors for advice about which faculty members to request as potential thesis reviewers. Several types of considerations might guide whom students seek as potential reviewers. For example, a student may seek a reviewer who has expertise in the topic they are studying, or they may seek breadth by requesting a reviewer with expertise in a quite distinct area of study, or they may seek a reviewer who has expertise in a relevant type of statistical analysis. It is up to the student, in consultation with their supervisor, to determine what factors to prioritise in selecting potential reviewers.

Course requirements for PSYCH 499B - oral presentation of the thesis proposal

During the PSYCH 499B term, students must finalize the research proposal for their honours thesis project and present this information orally to their thesis reviewer and the student’s thesis supervisor. Although the presentation is not graded, it is a course requirement that must precede the completed thesis. The presentation gives the student an opportunity to discuss their research proposals with a wider audience and to receive feedback regarding their literature review and the scope, design, testing procedures, etc., for their projects.

It is also essential that students who are doing an empirical research project involving human or animal participants formally apply for ethics clearance, and that they receive ethics clearance before beginning data collection (see 'Obtaining Ethics Clearance for Research with Human or Animal Participants' for further details).

Students should contact the PSYCH 499 course administrator in the Psychology Undergraduate Office early in the PSYCH 499B term to book the date and time for their oral presentation. When booking, students are asked to indicate if they will be presenting virtually, or in-person and should mention if the presentation is open to other students to attend. Students are asked to book their presentation as early as possible to ensure space is available The thesis reviewer will attend and conduct the presentation. Presentations occur during the first three months of each term (available dates/times and current presentation schedule are posted on the PSYCH 499 website ). The presentation should be 25 minutes in length followed by a 25 minute period for discussion and questions. Students are encouraged to attend other students' presentations when available.

A written version of the research proposal must be submitted to the mailbox or email of the thesis reviewer at least two business days prior to the scheduled date of the student's oral presentation of the proposal (meaning no later than 4:30pm Thursday for a Tuesday presentation). For empirical research projects, the proposal must include the following: a title page identifying the document as a "PSYCH 499B Research Proposal"; a brief review of the relevant scientific literature; a clear statement of the research question and major hypotheses to be examined; the planned method, including the number and types of participants, the design, the task or tests to be given, and the procedure to be used; the statistical tests and comparisons that are planned; and the expected date for beginning data collection. For a theoretical research project, the proposal must include a clear review of the issues, theories, or constructs to be analyzed; a description of the scholarly database to be used (including a list of important references); and a clear account of the intended contribution of the work (i.e., how it will advance understanding).

The research proposal must be approved and signed by the student's thesis supervisor before the proposal is submitted to the thesis reviewer . Students can get a better idea of the content and format required for the research proposal by referring to the methods section of completed honours theses. Students should keep a copy of their research proposal because the copy that is submitted to the thesis reviewer will not be returned.

All PSYCH 499 students must complete the ' TCPS 2 Tutorial Course on Research Ethics (CORE) ' before the research ethics application on which they are named is submitted for approval. In addition, all PSYCH 499 students must complete a "Researcher Training" session with the REG Coordinator .

Students who have completed the oral presentation requirement will receive an IP (In Progress) grade for PSYCH 499B; those who have not will receive an INC (Incomplete) grade for PSYCH 499B. INC and IP grades for PSYCH 499 do not impact on average calculations and students with either of these grades can be considered for the Dean's honours list. However, students with INC grades are not eligible for scholarship consideration. Note that INC grades convert to FTC (failure to complete = 32%) after 70 days.

Students who enrol in PSYCH 499A and 499B in the same term and satisfy the oral presentation requirement that term will not be required to also submit a progress report.

On-line surveys

Honours thesis students who require assistance regarding research software and the development of on-line surveys, beyond advice from the honours thesis supervisor, may wish to seek advice from Bill Eickmeier (Computer Systems Manager and Research Programmer; PAS 4008; ext 36638; email [email protected] ). Students are expected to manage much of this process independently and will be given access to a self-help website. Most students will be able to work independently using a Qualtrics account provided by the thesis supervisor, or using the web form template notes Bill has posted on the web. However, Bill is available to provide additional guidance if he is given at least three to four weeks advance notice.

Caution regarding off-campus data collection

If you are planning to collect data off-campus, please read carefully the " Field Work Risk Management " requirements provided by the University of Waterloo Safety Office. "Field Work" refers to any activity undertaken by members of the university in any location external to University of Waterloo campuses for the purpose of research, study, training or learning.

We assume that insurance for private vehicles is up to the owners and that insurance for rental vehicles, if applicable, would be through the rental company. Further details of University of Waterloo policies regarding travel .

Please discuss your plans for off-campus data collection with your thesis supervisor and the PSYCH 499 coordinator in advance to ensure that all bases are covered with regards to waivers, insurance, etc.

In the PSYCH 499C term, students will complete the data collection for their project (see the previous paragraphs if using on-line surveys or doing off-campus data collection), analyze/evaluate the data, and finish writing the honours thesis. The honours thesis must be written in the form indicated by the American Psychological Association (APA) Publication Manual (available at the Bookstore), but may be more abbreviated than a regular journal article. Sample honours theses can be found in the Learn shell.

For an empirical research project, the following sections are required in the thesis:

- introduction (literature review and the hypothesis)

- methods (participants, design, task or test to be given, testing procedures, measures)

It is not necessary to append ORE application forms to the completed honours thesis. However, a copy of the formal notification of ethics clearance is required.

The sections and subsections required for theoretical papers will be slightly different than for empirical research projects, and will vary according to the topic being studied. If possible, students should plan the layout for the theoretical paper in the PSYCH 499B term because the plan may guide their literature review. Students should consult with their thesis supervisor and the PSYCH 499 coordinator about the layout.

Normally students will receive feedback from their thesis supervisor on at least one or two (and often more) drafts of the thesis before the final paper is submitted for marking. Be sure to leave adequate time for this process.

Submitting the thesis for marking

The final version of the thesis is due the last day the class period for the PSYCH 499C term. However, due dates do change each term dependent on grade submission deadlines held by the registrar’s office, so it is important to follow the due date on our official due date page. See 'Extensions on the thesis submission deadline' below regarding requests for extensions.

In order for the Psychology Department to track theses that are submitted for marking and ensure that marks are forwarded to the Registrar's Office as quickly as possible, students must submit an electronic copy of the honours thesis to the PSYCH 499 course administrator who will coordinate grading by the thesis supervisor and the thesis reviewer , and will submit PSYCH 499 grades to the Registrar's Office. The honours thesis does not need to be signed by the thesis supervisor. The marking process is as follows:

- Receipt of the thesis will be recorded and an electronic copy of the thesis will be forwarded to the student's thesis supervisor and reviewer with a grading form for comments.

- The thesis supervisor will return the grading form with comments and a grade recommendation to the PSYCH 499 course administrator and the thesis reviewer.

- The thesis reviewer will be responsible for assigning the final grade and will return the completed grading form to the PSYCH 499 course administrator .

- T he PSYCH 499 course administrator will notify the student and the Registrar's Office of the final grade. The final numerical grade for the thesis will be recorded for each of PSYCH 499A, 499B, and 499C.

- Page 2 of the grading form will be returned to the student.

Extensions on the thesis submission deadline

We will do our best to ensure that students graduate at the preferred convocation date; however, we cannot guarantee that students who submit honours theses for marking after the deadline will be able to graduate at the preferred convocation date.

Students should refer to the PSYCH 499 website on a regular basis for information regarding PSYCH 499 deadlines that may affect the target date for submitting the honours thesis for marking (e.g., for getting one's name on the convocation program, for sending transcripts and/or letters regarding completion of the degree to other schools for admission purposes, to be considered for awards, etc.).

We strongly advise that students submit the thesis for marking at least four to six weeks prior to the date of convocation. Further, they should confirm that their thesis supervisor will be available to grade the thesis within a few days following submission of the thesis.

Students who do not submit an honours thesis for marking by the end of the examination period for the PSYCH 499C term require approval for an extension from their thesis supervisor. After speaking with the thesis supervisor, the student must report the revised date of completion to the PSYCH 499 course administrator . They will be given an IP (In Progress) grade for PSYCH 499C if they have done the oral presentation for PSYCH 499B and if they are making reasonable progress on the thesis. Otherwise, an INC (Incomplete) grade will be submitted for PSYCH 499C. INC and IP grades for PSYCH 499 do not impact on average calculations and students with either of these grades can be considered for the Dean's honours list. However, students with INC grades are not eligible for scholarship consideration. Note that INC grades convert to FTC (failure to complete = 32%) after 70 days.

Notes: 1. Honours students with INC and/or IP grades for PSYCH 499ABC will be unable to graduate (e.g., with a General BA in Psychology) until those grades are replaced by final grades (e.g., 32%) and the grades have been factored into the average calculation. In such cases, the student must meet all graduation requirements, including overall average, Psychology average, and minimum number of courses required. 2. If IP grades for all of PSYCH 499ABC remain on the record for 12 months following the PSYCH 499C term, the Registrar's Office will convert the IP grades to FTC (failure to complete = 32%). If this occurs, consult with the Psychology undergraduate advisor regarding your options.

Capture your thesis on video!

As of Fall 2012, we are asking honours thesis students if they'd like to take part in a voluntary "video snapshot" of their work. This is a great way to tell others about your thesis, and your experience at the University of Waterloo.

Upon completion of your thesis and submission of your 499C document, we are asking students to arrange for someone from their supervisor's lab to take a short 1-2 minute video clip of you the student. In that video, we'd like to hear a 'grand summary of what you researched, and what you found out'. We'd also love to hear about 'what you learned in the honours thesis course'.

These video clips can be taken with a smartphone (or other video camera), then emailed to the PSYCH 499 coordinator or the PSYCH 499 course administrator . Alternatively you can arrange a time to be videotaped by the course administrator (ideally when handing in your 499C final thesis document).

Completing a video is optional, and should be done ideally within two weeks of submission of your thesis. Whether or not you choose to capture your thesis on video will in no way affect your grade in the 499 honours thesis course. Once we have reviewed the video we will upload it to our Psychology website for general viewing by the public. Permission forms to release your photo/video on the Department of Psychology’s website will be available from the PSYCH 499 coordinator . The Model Release Form can also be found on Waterloo's Creative Services website.

Convocation awards

Each year the Psychology Department nominates a student(s) for the following awards: Governor General Silver Medal (university level), the Alumni Gold Medal (faculty level), and the Psychology Departmental convocation award. These awards are only given at the June convocation. Typically, only honours students who have final grades for all course work, including the honours thesis, by the first week of May can be considered for these awards. Students whose overall and Psychology averages fall in the 88-100% range are strongly encouraged to adhere to the thesis submission deadlines noted above.

The Office of Research Ethics (ORE) at the University of Waterloo is responsible for the ethics review and clearance of all research conducted on and off-campus by University of Waterloo students, staff, and faculty that involves human and animal (live, non-human vertebrates) participants.

Research involving human or animal participants must not begin until notification of full ethics clearance has been provided by the ORE.

Information regarding the application and ethics review process for research involving human participants is available on the Office of Research Ethics web site. However, specific information regarding the ethics application process for Honours thesis research is provided below.

Information regarding the application and ethics review process for research involving animals is also available on the Office of Research Ethics web site.

For individual contacts in the ORE, see 'Contacts' in this handbook.

Ethics Application: Once the rationale and hypotheses for the thesis project have been formulated and basic design and procedures have been determined, the student may submit the project for ethics review and clearance.

In order to ensure that students have a good understanding of the ethics review process and guidelines they are required to complete the TCPS2 -2022 CORE Tutorial (described below) prior to preparing your ethics application.

Upon completion of the CORE Tutorial, the student may begin the ethics application by signing onto the Kuali System for Ethics located at UWaterloo Ethics either starting the application on their own, or having the Thesis Advisor begin it. Please note that the student will need to have accessed the Kuali system in order for the Advisor to add them to the protocol. The advisor should be listed as the Principal Investigator and the level of research should be Senior Honours Thesis.

All Thesis projects require new ethics unless alternative arrangements have been made to make use of a currently running project. This should be discussed with the thesis advisor and approval should be obtained from the department to create an amendment for the project.

Upon receipt of Full Ethics Clearance, and if the student and supervisor are sure that there will be no revisions to the design or procedures, then data collection may begin. Whenever possible though, we encourage you to complete the Research Proposal and Oral Presentation before you begin data collection.

Note that procedures for applying for ethics clearance vary according to the type of sample -- for example, university students versus children in the Early Childhood Education Centre, etc. Further details are provided below.