Essay on Family Businesses

Family Business Overview

Currently, business family is becoming more influential and simpler to manage. This type of business is mainly owned by people with close relation to other forms of business internationally (Aguila and Briozzo, 2020 pp 49). Therefore, a family business can be defined as a business type in which two or more family members or related people form a cartel, thus operating as one firm. In most cases, the business’s complete control lies within the family members since they have common objectives to achieve. According to the research, the family business is recognized as one of the international forms of business contributing to the growth and development of most countries’ economies. Nowadays, the family business is believed as the engine of industrialization in most countries since they have contributed significantly to revenues and tax provision, especially to the governments (Ahmad and Yaseen 2018 pp 345). For any country to achieve its Gross Domestic Product (GDP), micro-business, such as family business and other small operating businesses, should provide taxes and revenues to the government.

Even though family business is categorized as micro, multinational family corporations can operate in more than two countries. Most of these multinationals’ family businesses are located in the United States of America, the United Kingdom, and Colombia. Basing the research conducted by the Institute of Family Business (IFB) 2012, about 5millions micro-businesses operating internationally are private sectors. These macro businesses contribute approximately 76% internationally to create job opportunities for the family members and other none related people (Antcliff et al.; 2020 pp 34 ). In the United States of America, micro-businesses such as family businesses are more considered than governmental sectors. Family businesses are believed to have contributed positively to providing affordable products and services to most unstable people.

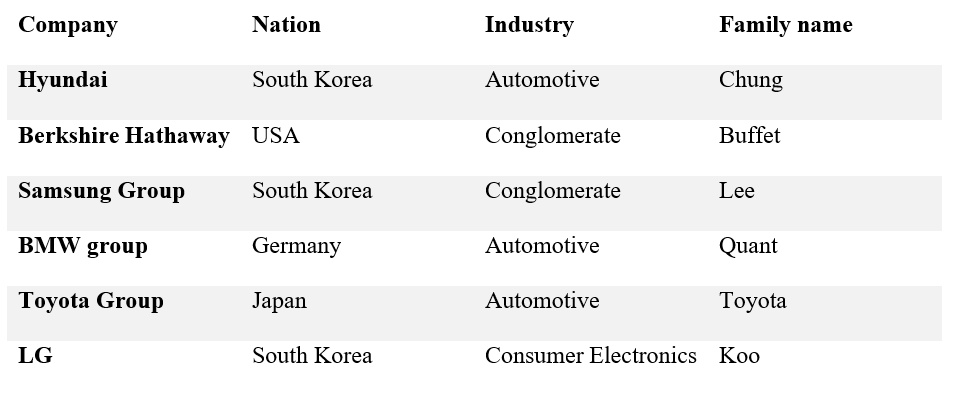

In most cases, the family business is owned and directed by family members, thus minimizing the chances of loss due to poor organization. The main strength of a family business is that there are no interferences since its characterized by monopolistic. Here are some examples of the most successful family business in the world.

Family-owned businesses are believed to be the oldest form of business organizations. Since the 1980s, the research shows that family business has distinct significance, especially in raising the county’s Economy; that’s why most countries consider operating micro-businesses as big firms and companies.

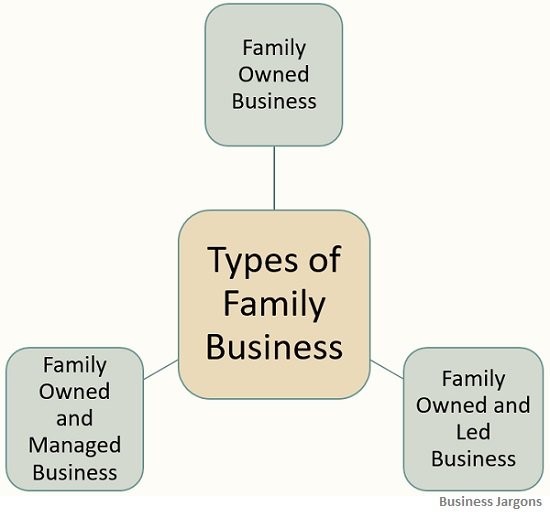

These family businesses are currently recognized as crucial and dynamic participants contributing to the highest world economy (Brenkman, 2020 pp 67-89). Basing U.S statistics, 90 percent of the United States of America owned family business. The growth and development of family business have mainly contributed in some countries such U.K. and Colombia. According to the IFB, the United Kingdom record more than a 4.8million family business which occupies more than 88 percent of the total business conducted within the United Kingdom. Currently, family businesses are the backbone of the United Kingdom economy, thus contributing about $ 150 billion annual tax. Within the age of huge businesses, it is significant to understand why family businesses are emerging to be the most successful than other forms of enterprises. In the United Kingdom, family business is growing at a higher rate, thus tending to outperform other close companies in physical markets. Naturally, United Kingdom is a unique country dominated mainly by heritage and encourages most families to inherit their parents’ work even if they pass away (Caputo et al.; 2018). The aspects of origin in the country elaborates on why the percentage of family businesses is rapidly increasing every year. In most cases, the family businesses are operated depending on the types and complexity of each. For instance, the chart below shows different kinds of family businesses and how they are managed.

The main reasons family businesses are more than other private sectors are that they are easy to perform and operate since they do not need to hire specialists or managers. Instead, they are primarily used and ran by related people. Additionally, these types of businesses do not incur much labor costs since they mostly rely on family members who are always available to offer free assistance (Seaman et al.; 2019 pp 345). According to Bolton Consulting Groups (BCG) arguments, the analysis shows that family businesses contribute about 45 percent of all the companies and organizations. To prove this, Dyson and JCB are good examples of the most prominent family businesses in the United Kingdom, which participate within their country and internationally. In connection to this, family businesses are the largest employers in the United Kingdom. So, it’s clear that family businesses have more benefits since people are derived by their determinations and what they need to achieve after operating their business.

Characteristics of Family Business

Family businesses are characterized by several features, which makes them operate successfully, unlike other companies. Family businesses are monopolistic by nature since only family people, and other relatives can run the business. In most cases, the business will only operate depending on the culture and norms of the family, thus not satisfying customers’ needs. From a perspective, a family business has operating hours and mostly may limit people from purchasing since customers have different times of purchasing. Basing the analysis of 33 countries, family businesses are simple to manage since their structure is less complex than other operating businesses (Chang et al.; 2020 pp 56). The design and characteristics of a family business depend on the number of people involved in the business operations. Concerning this, some features can be tangible while others are intangible. One of the most crucial characteristics of a family business is its strong trust and the inter-relationship between the family members.

In contrast to the other companies, there exist constant ideological differences between the management and other stakeholders within the industry. Regardless of the type of ownership and management team, the entire family members remain the critical participants in the company and can immediately decide to manipulate the nature of products they deal with. Another characteristic of a family business is that the management is always informal, and it’s hard to recognize any mistakes arising from the way of operations.

Most managers of these businesses have no definitive ideas to promote the business’s operations from one level to another.

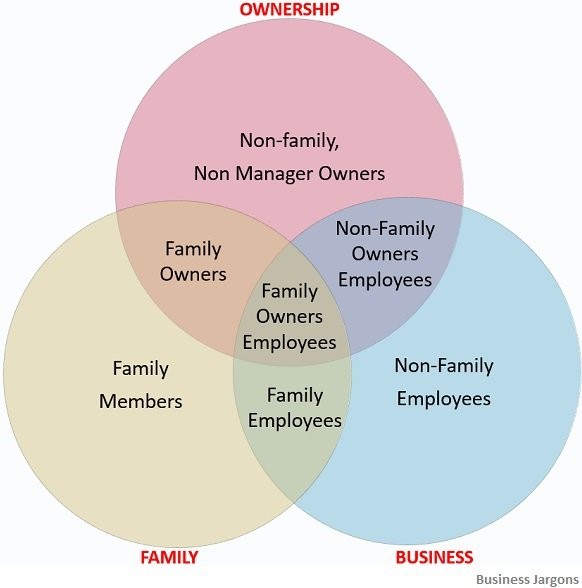

The excessive intermingling between the company and family members may encourage financial problems since most of the business’ capital can be directed to family issues that were not planned in the money. In some family businesses, there is no working time and private hours. Therefore, the operation of the company may become monotonous to some members. Naturally, doing one thing over a long time reduces interests (Pham et al.; 2019). Even though a family business may consist of other non-family members, the ownership and management of the company lie within the family members only. The figure below shows an example of business ownership and its structure. This is one of the main characteristics of family business currently

Therefore, the family business needs more management teams to ensure proper supervision is achieved. In some countries such as Canada and Australia, family business focuses on the companies’ long-term sustainability rather than gaining considerable profits. Most family businesses have limited access to goods and services; therefore, all characteristics of family business are passed from one generation to another. The generation to come will have to use unique features but what they think it’s good. However, according to Ryann’s arguments, family businesses have supported entrepreneurship since most family members another characteristic of a family business is complete control in terms of productions since the family is responsible for any required materials. However, most companies produce limited goods and services, such that there are no suppliers that can benefit none family people. To have a robust business, most families form cartels and partners with other more developed cooperation’s thus getting more chances of thriving in business.

Challenges facing family business

Even though family business is simple to manage, there are several challenges. The main challenge affecting family businesses is a generation gap. When many generations of different families are administering the company, the rate of changing from one technology to another might take long since not all people may understand it (Friar and Clark, 2021). For instance, the founders of some family businesses may resist handing off the management responsibilities to other upcoming families. This action creates characteristics of monopoly since most leaders make decisions based on their perspectives and ignoring the opinions of others. Even though younger generations may have some great ideas on how the business can operate efficiently and accurately, they are never involved in the business operations. This means that the company will continue working within flawed and outdated technologies since they lack the knowledge and skills to implement the new ideas (Heinonen et al .;2020 pp 1-34). Due to this, there may occur conflicts and frustrations since some employees feel that their voices and opinions are not considered in the implementation of the business.

Currently, most family members fail to understand that everybody can contribute positively to the industry. To overcome such challenges, the family should negotiate towards the succession of leadership without chaos. Another challenge associated with family businesses is business culture. In this type of business, it’s tough for the company to accept all cultures and values from different families. Even if related people form the industry, some people have different cultural opinions that may not match other family members involved. For example, Samsung business involves different families with different ideological thinking thus may be difficult to operate within the same culture. In this case, most family businesses use basing the cultural system of the paramount families. The interferences of business can lead to low turnover rates, thus reducing the productivity of the company. Setting up payment strategies can currently face other problems facing family business (Núñez et al., 2018). Determining payments in the industry may raise conflicts because some members cannot be paid equally. The prices should be determined based on the duties and responsibilities of the individuals; however, some family members may demand equal payment, thus building uncertainty and mistrust. Some employees may get annoyed in the reaction to such cases since they don’t expect to work hard and get fewer payments.

When employees are not positively encouraged, they may lose morale, while others may decide to leave the job to look better. Therefore, this means some family members will lose business morale and, with time, will seize supporting business operations. Another challenge affecting family business is mixing business with home life. According to the research, when family members work in the same companies and organizations, it becomes challenging to make definitive decisions without basing personal feelings. (Kanade et al.; 2020) Due to this, family businesses can operate poorly due to family events, whereby families may decide to make frequent holidays that do not concern business operations. The issue of holding every family member in the same standard is another challenge facing family enterprises. For instance, some employees may be spending a lot of time in the breakfast rooms than in the business desk operations. The aspects of some members westing time in the busines may contribute low output thus reducing the business’s productivity.

When some people in the business are not operating according to business formalities, the other employees may develop negative implications. They may not work smart to achieve the objectives and anticipated target of the organization. Additionally, these behaviors will create laxity and mistrust in the organizations. According to the research, the most family business faces interferences and challenges from within the family members especially those in the top management (Michiel et al.; 2017 pp 369). Planning for the future is another upcoming challenge facing the operations of most family businesses. Since most family enterprises are characterized by solid planning, it becomes difficult to modify the planned decisions.

Consequently, making decisions becomes tedious because of the extended channels to be followed. If the business involves more than two families, the decisions are made based on both families’ final discussions. Therefore, before plans and decisions are made, there must be consultations from all the family and relatives. Nowadays, there is a need for family members to understand how the business should be conducted to avoid such challenges.

Recommendations

To overcome the social and economic contributions made by the family businesses, there are crucial aspects that we need to look at. Both characteristics and challenges associated with family businesses can be overcome if the family members get serious with business and stop focusing on things that do not relate to the business (Michiel et al.;, 2017 pp 369). According to the discussions, most family businesses are affected by top management’s ignorance since they think they control everything in the business basing their knowledge. According to my perspective, family businesses can only improve if the management team considers the opinions of others. To have good business, there is a need to involve all the employees in the decision-making process. To have a better understanding of family businesses, the following recommendations should be taken into account. The performance of the business should be optimized and act as a reference to other generations to come. Family businesses are believed to have contributed positively to providing affordable products and services to most unstable people.

In most cases, the family business is owned and directed by family members, thus minimizing the chances of loss due to poor organization. Additionally, the operation of a family business should not base on the specific family since it may promote hatred and non-stoppable conflicts within the related people (Musso et al.; 2020 pp 23). Also, the business should be in the position to serve the general population without considering if the buyers come from the same clan. The family business will act as a catalyst that speeds the growth and development of the Economy. For better family business success, the younger people should be involved in the management team since they might have more technical skills to help family businesses thrive well.

To have peace and harmony within the industry, there should equal distribution of the profits gained from the company since its efforts of every individual performing in the industry. For instance, when some industries are not operating according to business formalities, the other employees may develop negative implications. They may not work smartly to achieve the objectives and anticipated target of the organization (Musso et al.; 2020 pp 23). The family should be considered as the primary influence both on the companies’ operations and strategic orientations. For this reason, the management and combination of the several families will positively contribute to the growth and prosperity of the business even in the future.

Self-reflection on family businesses

The family business is one the best enterprise to operate despite its challenges. Basing the research analysis, the family business is simple to use compared to all other forms of business internationally. Basing my views, the family business has benefited most people worldwide by providing employments to non-employed people. Even though the company operates without physical interference from governments, it faces some challenges which can be solved basing its structure. This reflection is a way of considering all the characteristics and challenges that have been facing family businesses. According to my arguments, a family business can improve if they follow all the above recommendations. Additionally, there is a need for the managers and supervisors to understand that the success of most companies depends on decision-making.

To sum up, the family business has contributed to social-economic growth, especially in European countries. According to the research, these businesses have contributed about 67% of Gross Domestic Products, especially in the United States of American and the United Kingdom. Regardless of the type of ownership and management team, the entire family members remain the critical participants in the company and can immediately decide to manipulate the nature of products they deal with. Another characteristic of a family business is that the management is always informal, and it’s hard to recognize any mistakes arising from the way of operations. Even though family business is categorized as micro, multinational family corporations can operate in more than two countries. Most of these multinationals’ family businesses are located in the United States of America, the United Kingdom, and Colombia. The prosperity of many family businesses depends on their structure and operational structure. Basing the research arguments, the family business will continue been in the top in European’s countries since families believe in amalgamation is more effective than individualism.

Aguilar, V.G. and Briozzo, A., 2020. Family businesses: capital structure and socio-emotional wealth. Investigación administrativa , 49 (125).

Ahmad, Z. and Yaseen, M.R., 2018. Moderating role of education on succession process in small family businesses in Pakistan. Journal of Family Business Management . pp 345

Antcliff, V., Lupton, B. and Atkinson, C., 2020. Why do small businesses seek support for managing people? Implications for theory and policy from an analysis of U.K. small business survey data. International Small Business Journal pp 34

Brenkman, A.R., 2020. Exploring the management succession process in small and medium-sized family businesses (Doctoral dissertation, North-West University (South Africa)). pp 67-89

Caputo, A., Marzi, G., Pellegrini, M.M. and Rialti, R., 2018. Conflict management in family businesses. International Journal of Conflict Management .

Chang, A.A., Mubarik, M.S. and Naghavi, N., 2020. Passing on the legacy: exploring the dynamics of succession in family businesses in Pakistan. Journal of Family Business Management . Pp 56

Friar, J.H., Ippolito, J. and Clark, T., 2021. The challenges of transitioning to professional selling in family businesses. In A Research Agenda for Sales . Edward Elgar Publishing.

Heinonen, J. and Ljunggren, E., 2020. It’s not all about the money: narratives on emotions after a sudden death in family businesses. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship , pp.1-23.

Kandade, K., Samara, G., Parada, M.J. and Dawson, A., 2020. From family successors to successful business leaders: A qualitative study of how high-quality relationships develop in family businesses Journal of Family Business Strategy , p.100334.

Michiels, A. and Molly, V., 2017. Financing decisions in family businesses: a review and suggestions for developing the field. Family Business Review , 30 (4), pp.369-399.

Musso, F. and Francioni, B., 2020. The strategic decision-making process for the internationalization of family businesses. Sinergie Italian Journal of Management , 38 (2), pp.21-43.

Núñez-Cacho, P., Molina-Moreno, V., Corpas-Iglesias, F.A. and Cortés-García, F.J., 2018. Family businesses transitioning to a circular economy model: The case of “Mercadona”. Sustainability , 10 (2), p.538.

Pham, T.T., Bell, R. and Newton, D., 2019. The father’s role in supporting the son’s business knowledge development process in Vietnamese family businesses. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies .

Seaman, C., McQuaid, R. and Pearson, M., 2017. Social networking in family businesses in a local economy. Local Economy , 32 (5), pp.451-466.

Visser, T. and van Scheers, L., 2020. HOW IMPORTANT IS ENTREPRENEURIAL ORIENTATION FOR FAMILY BUSINESSES?. Management: Journal of Contemporary Management Issues , 25 (2), pp.235-250.

Wang, Y. and Shi, H.X., 2020. Particularistic and system trust in family businesses: The role of family influence. Journal of Small Business Management , pp.1-35.

Yoshida, S., Yagi, H. and Garrod, G., 2020. Determinants of farm diversification: entrepreneurship, marketing capability and family management. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship , 32 (6), pp.607-633

Cite this page

Similar essay samples.

- Essay on Information, Technology and HIPAA Act

- Essay on State Income Taxes

- Mild Persistent Asthma: A Discussion

- Exploring groups and their dynamics

- Essay on Evidence-Based Practice

- Is Psychology a science and should it be?

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

107 Family Businesses Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Family businesses are a cornerstone of many communities around the world. These enterprises are often passed down through generations, with family members working together to run and grow the business. Family businesses come in all shapes and sizes, from small mom-and-pop shops to large corporations.

If you are tasked with writing an essay about family businesses, you may be wondering where to start. To help you get your creative juices flowing, we have compiled a list of 107 family business essay topic ideas and examples. Whether you are looking to explore the challenges faced by family businesses, the benefits of working with family members, or the impact of family businesses on the economy, there is a topic on this list for you.

- The history and evolution of family businesses

- The role of family values in shaping a family business

- The challenges of succession planning in family businesses

- The benefits of family businesses for local communities

- The impact of family businesses on the economy

- The unique management styles of family businesses

- The importance of communication in family businesses

- The advantages and disadvantages of working with family members

- The role of women in family businesses

- The impact of technology on family businesses

- The benefits of family businesses for employees

- The role of innovation in family businesses

- The challenges of balancing work and family in a family business

- The impact of globalization on family businesses

- The importance of trust in family businesses

- The role of family dynamics in shaping a family business

- The impact of cultural differences on family businesses

- The challenges of managing conflicts in a family business

- The benefits of having a family business mentor

- The impact of family businesses on the environment

- The role of family businesses in preserving traditions

- The challenges of managing a family business during a crisis

- The benefits of family businesses for customers

- The impact of social media on family businesses

- The importance of ethics in family businesses

- The role of education in preparing the next generation to take over a family business

- The challenges of managing a family business in a competitive market

- The benefits of having a diverse workforce in a family business

- The impact of government regulations on family businesses

- The role of networking in growing a family business

- The challenges of balancing family and business responsibilities in a family business

- The benefits of having a strong company culture in a family business

- The impact of generational differences on family businesses

- The importance of succession planning in ensuring the longevity of a family business

- The role of branding in building a successful family business

- The challenges of managing family business finances

- The benefits of having a clear mission and vision in a family business

- The impact of mergers and acquisitions on family businesses

- The role of social responsibility in family businesses

- The challenges of adapting to change in a family business

- The benefits of having a strong support system in a family business

- The impact of family businesses on employee retention

- The importance of work-life balance in a family business

- The role of conflict resolution in maintaining harmony in a family business

- The challenges of managing a family business in a recession

- The benefits of having a diverse product line in a family business

- The impact of competition on family businesses

- The role of technology in streamlining operations in a family business

- The challenges of expanding a family business into new markets

- The benefits of having a strong marketing strategy in a family business

- The impact of industry trends on family businesses

- The importance of customer feedback in improving a family business

- The role of employee training in a family business

- The challenges of managing a family business with remote employees

- The benefits of having a family business advisory board

- The impact of customer loyalty on family businesses

- The role of family businesses in creating jobs

- The challenges of managing a family business with multiple locations

- The benefits of having a family business succession plan

- The impact of social media marketing on family businesses

- The importance of data analytics in optimizing operations in a family business

- The role of family businesses in promoting economic growth

- The challenges of managing a family business with limited resources

- The benefits of having a strong customer service team in a family business

- The impact of employee morale on family businesses

- The role of employee recognition in motivating staff in a family business

- The challenges of managing a family business with seasonal fluctuations

- The benefits of having a strong sales team in a family business

- The impact of customer reviews on family businesses

- The importance of employee training and

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

The five attributes of enduring family businesses

Family businesses are an often overlooked form of ownership. Yet they are all around us—from neighborhood mom-and-pop stores and the millions of small and midsize companies that underpin many economies to household names such as BMW, Samsung, and Wal-Mart Stores. One-third of all companies in the S&P 500 index and 40 percent of the 250 largest companies in France and Germany are defined as family businesses, meaning that a family owns a significant share and can influence important decisions, particularly the election of the chairman and CEO.

As family businesses expand from their entrepreneurial beginnings, they face unique performance and governance challenges. The generations that follow the founder, for example, may insist on running the company even though they are not suited for the job. And as the number of family shareholders increases exponentially generation by generation, with few actually working in the business, the commitment to carry on as owners can’t be taken for granted. Indeed, less than 30 percent of family businesses survive into the third generation of family ownership. Those that do, however, tend to perform well over time compared with their corporate peers, according to recent McKinsey research. Their performance suggests that they have a story of interest not only to family businesses around the world, of various sizes and in various stages of development, but also to companies with other forms of ownership.

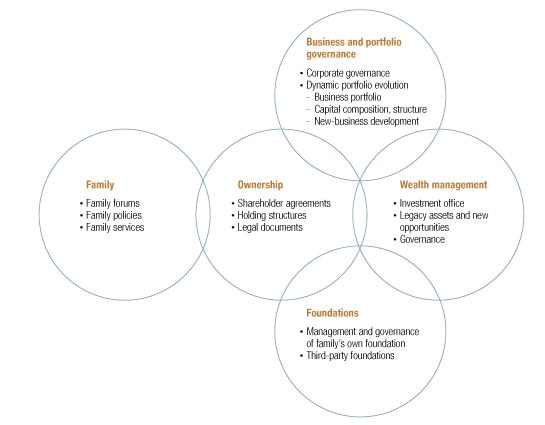

To be successful as both the company and the family grow, a family business must meet two intertwined challenges: achieving strong business performance and keeping the family committed to and capable of carrying on as the owner. Five dimensions of activity must work well and in synchrony: harmonious relations within the family and an understanding of how it should be involved with the business, an ownership structure that provides sufficient capital for growth while allowing the family to control key parts of the business, strong governance of the company and a dynamic business portfolio, professional management of the family’s wealth, and charitable foundations to promote family values across generations (Exhibit 1).

Five dimensions

Family businesses can go under for many reasons, including family conflicts over money, nepotism leading to poor management, and infighting over the succession of power from one generation to the next. Regulating the family’s roles as shareholders, board members, and managers is essential because it can help avoid these pitfalls.

Large family businesses that survive for many generations make sure to permeate their ethos of ownership with a strong sense of purpose. Over decades, they develop oral and written agreements that address issues such as the composition and election of the company’s board, the key board decisions that require a consensus or a qualified majority, the appointment of the CEO, the conditions in which family members can (and can’t) work in the business, and some of the boundaries for corporate and financial strategy. The continual development and interpretation of these agreements, and the governance decisions guided by them, may involve several kinds of family forums. A family council representing different branches and generations of the family, for instance, may be responsible to a larger family assembly used to build consensus on major issues.

Long-term survivors usually share a meritocratic approach to management. There’s no single rule for all, however—policies depend partly on the size of the family, its values, the education of its members, and the industries in which the business competes. For example, the Australia-based investment business ROI Group, which now spans four generations of the Owens family, encourages family members to work outside the business first and gain relevant experience before seeking senior-management positions at ROI. Any appointment to them must be approved both by the owners’ board, which represents the family, and the advisory council, a group of independent business advisers who provide strategic guidance to the board.

As families grow and ownership fragments, family institutions play an important role in making continued ownership meaningful by nurturing family values and giving new generations a sense of pride in the company’s contribution to society. Family offices, some employing less than a handful of professionals, others as many as 40, can bring together family members who want to pursue common interests, such as social work, often through large charity organizations linked to the family. The office may help organize regular gatherings that offer large families a chance to bond, to teach young members how to be knowledgeable and productive shareholders, and to vote formally or informally on important matters. It can also keep the family happy by providing investment, tax, and even concierge services to its members.

Maintaining family control or influence while raising fresh capital for the business and satisfying the family’s cash needs is an equation that must be addressed, since it’s a major source of potential conflict, particularly in the transition of power from one generation to the next. Enduring family businesses regulate ownership issues—for example, how shares can (and cannot) be traded inside and outside the family—through carefully designed shareholders’ agreements that usually last for 15 to 20 years.

Many of these family businesses are privately held holding companies with reasonably independent subsidiaries that might be publicly owned, though in general the family holding company fully controls the more important ones. By keeping the holding private, the family avoids conflicts of interest with more diversified institutional investors looking for higher short-term returns. Financial policies often aim to keep the family in control. Many family businesses pay relatively low dividends because reinvesting profits is a good way to expand without diluting ownership by issuing new stock or assuming big debts.

In fact, some families decide to shut external investors out of the entire business and to fuel growth by reinvesting most of the profits, which requires good profitability and relatively low dividends. Others decide to bring in private equity as a way to inject capital and introduce a more effective corporate governance culture. In 2000, for example, the private-equity investor Kohlberg Kravis Roberts gave Zumtobel, the Austria-based European market leader for professional lighting, a capital infusion (KKR exited in 2006). Such deals can add value, but the downside is that they dilute family control. Others take the IPO route and float a portion of the shares. An IPO can also be a way to provide liquidity at a fair market price for family members wanting to exit as shareholders.

To keep control, many family businesses restrict the trading of shares. Family shareholders who want to sell must offer their siblings and then their cousins the right of first refusal. In addition, the holding often buys back shares from exiting family members. Payout policies are usually long term to avoid decapitalizing the business.

Because exit is restricted and dividends are comparatively low, some family businesses have resorted to “generational liquidity events” to satisfy the family’s cash needs. These may take the form of sales of publicly traded businesses in the holding or of sales of family shares to employees or to the company itself, with the proceeds going to the family. One chairman said of his company, “Every generation has a major liquidity event, and then we can go on with the business.”

Governance and the business portfolio

With clear rules and guidelines as an anchor, family enterprises can get on with their business strategies. Two success factors show up frequently: strong boards and a long-term view coupled with a prudent but dynamic portfolio strategy.

Strong boards

Large and durable family businesses tend to have strong governance. Members of these families avoid the principal–agent issue by participating actively in the work of company boards, where they monitor performance diligently and draw on deep industry knowledge gained through a long history. On average, 39 percent of the board members of family businesses are inside directors (including 20 percent who belong to the family), compared with 23 percent in nonfamily companies, according to an analysis of the S&P 500. 1 1. Ronald C. Anderson and David M. Reeb, “Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500,” The Journal of Finance , 2003, Volume 58, Number 3, pp. 1301–27. “The family is a true asset to the management team, since they have been around the industry for decades,” said the CEO of a family business. "Still, they separate ownership and management in a good way.”

Of course, it’s important to complement the family’s knowledge with the fresh strategic perspectives of qualified outsiders. Even when a family holds all of the equity in a company, its board will most likely include a significant proportion of outside directors. One family has a rule that half of the seats on the board should be occupied by outside CEOs who run businesses at least three times larger than the family one.

Procedures for all nominations to the board—insiders as well as outsiders—differ from company to company. Some boards select new members and then seek consent by an inner family committee and formal approval by a shareholder assembly. Formal mechanisms differ; what counts most is for the family to understand the importance of a strong board, which should be deeply involved in top-executive matters and manage the business portfolio actively. Many have meetings that stretch over several days to discuss corporate strategy in detail.

Family businesses, like their nonfamily peers, face the challenge of attracting and retaining world-class talent to the board and to key executive positions. In this respect, they have a handicap because nonfamily executives might fear that family members make important decisions informally and that a glass ceiling limits the career opportunities of outsiders. Still, family businesses often emphasize caring and loyalty, which some talented people may see as values above and beyond what nonfamily corporations offer.

A long-term portfolio view

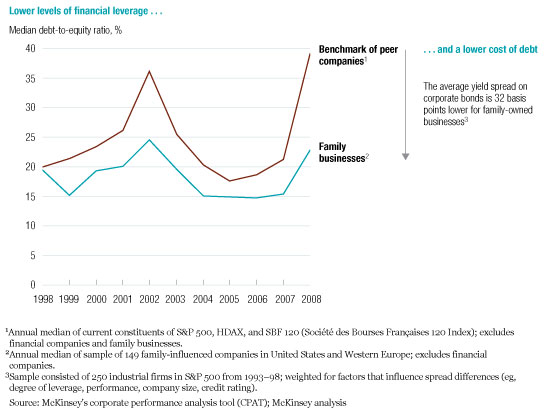

Successful family companies usually seek steady long-term growth and performance to avoid risking the family’s wealth and control of the business. This approach tends to shield them from the temptation—which has recently brought many corporations to their knees—of pursuing maximum short-term performance at the expense of long-term company health. A longer-term planning horizon and more moderate risk taking serve the interests of debt holders too, so family businesses tend to have not only lower levels of financial leverage but also a lower cost of debt than their corporate peers do (Exhibit 2).

Taking the long view

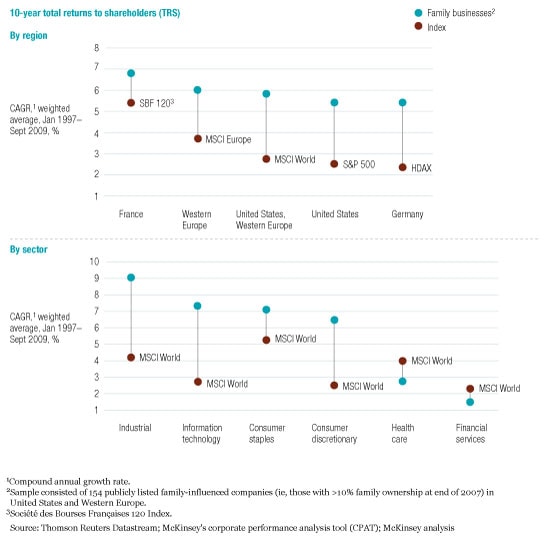

The longer perspective may make family businesses less successful during booms but increases their chances of staying alive in periods of crisis and of achieving healthy returns over time. In fact, despite the unique challenges facing family-influenced businesses, from 1997 to 2009 a broad index of publicly traded ones in the United States and Western Europe achieved total returns to shareholders two to three percentage points higher than those of the MSCI World, the S&P 500, and the MSCI Europe indexes (Exhibit 3). It is difficult to provide statistical proof that the family influence was the main driver. The results were surprisingly stable across geographies and industries, however, and indicate that family businesses have performed at least in line with the market—a finding corroborated by academic research. 2 2. See Ronald C. Anderson; David M. Reeb, “Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500,” The Journal of Finance , 2003, Volume 58, Number 3, pp. 1301–27; and also Roberto Barontini and Lorenzo Caprio, “The effect of family control on firm value and performance: Evidence from continental Europe,” EFA 2005 Moscow Meetings paper, 2005.

Healthy returns over time

This long-term focus implies relatively conservative portfolio strategies based on competencies built over time, coupled with moderate diversification around the core businesses and, in many cases, a natural preference for organic growth. Family-influenced businesses tend to be prudent when they do M&A, making smaller but more value-creating deals than their corporate counterparts do, according to our analysis of M&A deals worth over $500 million in the United States and Western Europe from 2005 to late 2009. The average deal of family businesses was 15 percent smaller, but the total value added through it—measured by market capitalization after the announcement—was 10.5 percentage points, compared with 6.3 points for their nonfamily counterparts. 3 3. The sample includes 78 deals for family-owned businesses and 494 deals for businesses not owned by families. The acquirers (both kinds of companies) were constituents of the US S&P 500, the German HDAX, or the French SBF 120 (Société des Bourses Françaises 120 Index) stock indexes. Value added through the deal is defined as the change in market capitalization, adjusted for market movements, from two days prior to two days after the announcement. The analysis includes all deals completed from 2005 to late 2009 with a value of over $500 million in which the acquirers’ ownership went from nothing to 100 percent.

Nonetheless, too much prudence can be dangerous. Family owners, who usually have a significant part of their wealth associated with the business, face the challenge of preventing an excessive aversion to risk from influencing company decisions. Excessive risk aversion might, for example, unduly limit investments to maintain and build competitive advantage and to diversify the family’s wealth. Diversification is important not only for overall long-term performance but also for control because it helps make it unnecessary for family members to take money out of the business and diversify their assets themselves.

That’s why most large, successful family-influenced survivors are multibusiness companies that renew their portfolios over time. While some have a wide array of unconnected businesses, most focus on two to four main sectors. In general, family businesses seek a mix: companies with stable cash flows and others with higher risk and returns. Many complement a group of core enterprises with venture capital and private-equity arms in which they invest 10 to 20 percent of their equity. The idea is to renew the portfolio constantly so that the family holding can preserve a good mix of investments by shifting gradually from mature to growth sectors.

Wealth management

Beyond the core holdings, families need strong capabilities for managing their wealth, usually held in liquid assets, semiliquid ones (such as investments in hedge funds or private-equity funds), and stakes in other companies. By diversifying risk and providing a source of cash to the family in conjunction with liquidity events, successful wealth management helps preserve harmony.

Success is not a sure thing. Many wealthy families around the world lost a lot of money in the financial crisis—losses that vary by geography but averaged 30 to 60 percent from the second quarter of 2008 to the first quarter of 2009. One European family investor with a portfolio mainly in the money market and in prime income-generating real estate lost less than 5 percent. At the other extreme, a family investor in the same country, with 80 percent of his assets in real-estate developments and hedge funds, both with 50 to 70 percent leverage, lost 30 to 50 percent of the value in these asset classes at the peak of the crisis.

These different outcomes highlight the importance of a professional organization with strong, consolidated, and rigorous risk management to oversee the wealth family businesses generate. For large fortunes, the best solution is a wealth-management office serving a single family—either a separate entity or part of a family office providing a range of family services (described earlier in this article). A wealth-management office that serves a group of unconnected families is an option when individual ones don’t have the scale to justify the cost of a single-family office.

Our work with family wealth-management offices has helped us identify five key factors that increase the chances of success: a high level of professionalism, with institutionalized processes and procedures; rigorous investment and divestment criteria; strict performance management; a strong risk-management culture, with aggregated risk measurement and monitoring; and thoughtful talent management.

Foundations

Charity is an important element in keeping families committed to the business, by providing meaningful jobs for family members who don’t work in it and by promoting family values as the generations come and go. Sharing wealth in an act of social responsibility also generates good will toward the business. Foundations set up by entrepreneurial families represent a huge share of philanthropic giving around the world. In the United States, they include 13 of the 20 largest players, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Money alone does not guarantee a high social impact. In addition to the financial and operational issues facing any charitable activity, families must cope with the critical challenge of nurturing a consensus on the direction of their philanthropic activities from one generation to the next. Some family foundations have tackled the issue by creating a discretionary spending budget allowing family members to finance projects that interest them. Others give them opportunities to serve on the board or staff of the foundation or to participate directly in philanthropic projects through onsite visits and volunteering schemes. This approach is an especially powerful way to engage the next generation early on.

Family foundations also face organizational and operational choices about how best to use their funds. Several have concluded that in today’s complex environment, partnerships—for example, with nonprofits or nongovernmental organizations—can promote the family’s social goals. These foundations build on the experience and local presence of other organizations, particularly when implementing projects in unfamiliar geographies.

To ensure high performance and continual improvement, family foundations must combine passion with professionalism and a strict assessment of their impact. Despite the difficulties of assessing it, this is vital to make progress and allocate resources effectively. In our experience, family foundations should focus their monitoring and evaluation efforts around learning and improved decision making. They must also approach operations with the mind-set of an investor—minimizing operating costs and making prudent investments in strategy, planning, and evaluation as well as in highly qualified staff.

Almost all companies start out as family businesses, but only those that master the challenges intrinsic to this form of ownership endure and prosper over the generations. The work involved is complex, extensive, and never-ending, but the evidence suggests that it is worth the effort for the family, the business, and society at large.

Christian Caspar is a director in McKinsey’s Zurich office; Ana Karina Dias is an associate principal in the São Paulo office, where Heinz-Peter Elstrodt is a director.

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of Andres Maldonado, an alumnus of McKinsey’s São Paulo office.

Explore a career with us

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets and Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Webinars

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

Managing a Family Business for Success and Succession

Exploring the dynamics and decisions of running a family business in Kenya.

May 18, 2021

Meet Naomi Kipkorir and Annette Kimitei, the mother-daughter team leading Senaca East Africa, and Peter Francis, lecturer at Stanford Graduate School of Business, and hear about finding success and navigating succession in a family-run business.

Family dynamics can be challenging, not to mention emotional. But when you add in a business, things can get even more complicated, especially when the entire family is involved. That’s the story behind Senaca EA, a private security company headquartered in Nairobi, Kenya. Founded by Kipkorir’s husband, an ex-policeman, the business started in 2002 as a side hustle and now it’s a full-time, all-in-the-family-of-five affair.

After a failed merger with a European company, the family literally came together to pull their company back from the brink. Thinking about family succession came next. And as Kimitei learned, “Succession is not one event, it’s a process.” Formalizing corporate governance is key to that process, which for Senaca begins with introducing advisory board members who have skill sets the business is missing, and eventually independent directors.

Francis fully supports that plan. And he knows from experience: his family-run business has been going for six generations. Francis uses that firsthand knowledge to teach a class called “The Yin and Yang of Family Business Transition” at Stanford. Because issues that arise in a family business can often turn emotional, Francis advises seeking outside expertise and relying on education, transparency, and communication to handle tough issues.

“If you’re having a conversation about the business at home you might say, ‘You know what, we’re home, we should be wearing our family hat, not our business hat.’ And then communication … I don’t mean just communicating, but also learning how to communicate. That is a muscle that we can strengthen in the family.”

Listen to Kipkorir and Kimitei’s family story and Francis’ business insights to help think about your own company’s succession and governance plans.

Suggested Resources

Grit & Growth is a podcast produced by Stanford Seed , an institute at Stanford Graduate School of Business which partners with entrepreneurs in emerging markets to build thriving enterprises that transform lives.

Hear these entrepreneurs’ stories of trial and triumph, and gain insights and guidance from Stanford University faculty and global business experts on how to transform today’s challenges into tomorrow’s opportunities.

Full Transcript

Naomi Kipkorir: We are not just a family business that is by blood. Even the way we relate with our customers, the way we relate with our suppliers, the way we relate with each other, we came to realize that it was a strength and not a weakness.

Darius Teter: Naomi Kipkorir is the proud CEO of a family business, and she’s been on quite a journey with her company.

Naomi Kipkorir: I used to tell them, “Whatever brought us here won’t take us where we are going. So you have to accept change.” And they are telling me, “Now it’s not change, it’s even transformation.”

Darius Teter: For family businesses, planning for leadership change presents many challenges. But could the act of family succession itself give your business the tools to re-imagine

I’m Darius Teter, and this is Grit & Growth with Stanford Graduate School of Business, the show where Africa and South Asia’s intrepid entrepreneurs share their trials and trials, with insights from Stanford faculty and global experts on how to tackle challenges and grow your business. Today, we meet the mother-daughter team of CEO, Naomi Kipkorir, and managing director, Annette Kimitei, of Senaca East Africa, to hear about how they are facing family succession and board governance issues head-on.

Our story begins in the Republic of Kenya. Here, the traditional economic bases are agriculture, trade, and tourism, but in recent years, tech, manufacturing, and construction industries have accelerated. At the same time, the threat of terrorism and insecurity has spurred the rapid growth and diversification of the private security industry, and that’s where family business Senaca East Africa got its start. Here’s founder and CEO, Naomi Kipkorir.

Naomi Kipkorir: Senaca was started in the year 2002 by my husband who was an ex-policeman. We are in the business of ensuring that the country, families, and businesses are safe as we offer private security. My husband started the company. By that time, I was in full-time employment in a government parastatal. I didn’t join him immediately because initially, it was just a side hustle. Later, I saw the passion and the seriousness he put in the business, and after five years I resigned and I joined him full-time.

Darius Teter: You came onto the business within about a year of your husband’s starting it, and then quite quickly, he handed increasing authority and control over to you. Who else is in the business from the family?

Naomi Kipkorir: I was blessed with three daughters. Annette is my firstborn. She’s in the business now as the managing director. My second born also did finance, a CFA, and she’s also in charge of finance. And my third born, who is the last born, she did legal, and she also takes care of the support services in the business. So all of them are working together.

Darius Teter: Naomi and John’s three daughters all found their place within the family business, and Annette, the oldest, joins us today.

Annette Kimitei: Annette Kimitei, and I’m the MD of Senaca East Africa, a woman very passionate about private security in the East African region.

Darius Teter: What were the security issues like in Kenya when your father started the business?

Annette Kimitei: I do recall private security was not common back then. The Kenyan scenario of a security officer was probably someone who couldn’t speak proper English or Swahili, which are the two national languages. So it’s just someone you get from the village and you put a couple of sweaters with a logo, and that’s it. And then you give them instruction. So yes, security was not really much of a need, but what happened is as a growing economy, of course, people started building homes. There was a little bit more urbanization. Factories started to come up, and then thefts also came in. Right now, the biggest threats we face, for example, are the threats of terrorism, the threats of cybersecurity, technological threats, reputational threats, and risk management. But then that was not the case.

Darius Teter: You’ve grown up in the business from childhood. I’m curious, what are your earliest memories of it?

Annette Kimitei: Well, I didn’t like it, to be honest. When my father was growing up, being a policeman was really cool. That was the career everyone wanted to aspire to. But by the time I was growing up being a lawyer, being an engineer, those were pretty cool courses. But what happened is when dad started the business in 2002, by the time he started growing in 2004, I joined university. So just to keep busy and probably not be naughty around the home, Dad would carry me to work and then just help me help him with filings. So my first encounter with the business was actually helping Dad and mostly was in registry. But I’m really grateful for that opportunity because I believe it’s through registry, through working in the file room, which is not something that many people, particularly family businesses, would appreciate, I actually learned how to do tenders, for example, official letters to customers, appointment letters, promotion letters. And that’s what actually changed my career.

Darius Teter: In time, Annette progressed from administrative tasks all the way to her current role as managing director, and we’re going to explore that succession process later. But to understand the unique dynamics at play here, I wanted to speak to someone with deep knowledge from both inside and outside a family business. Here’s Stanford Graduate School of Business lecturer, Peter Francis.

Peter Francis: My name is Peter Francis. I am a member of a family that has a rather large family business; it’s in the sixth generation. I ran that company as a chairman and CEO for 16 years. Currently, I am investing in small businesses, and I also teach at Stanford at the business school. I teach a course on family business transitions called the Yin and Yang of Family Business Transitions.

Darius Teter: So in Africa, our research has told us that something like 30 to 40% of the largest companies in Africa are family businesses, but I want to start with how would you define a family-run business?

Peter Francis: As far as I’m concerned, there are two key things. The first is that a family needs to have sufficient strategic control, if you will, over that business so that they can make key decisions such as who’s running the business or have very, very strong input to those decisions. And then the second characteristic is they have to have the intent to take their family ownership and move it from one generation to another.

Darius Teter: Interesting. Can we talk a little bit about the advantages and disadvantages of being a family-run business?

Peter Francis: It surprises people oftentimes to hear that family businesses actually perform better than their public counterparts. And it strikes me that there are four really important things. The first is what I call patient capital. The median tenure of a CEO in the Fortune 500, S&P 500 is something around the range of five years. The incentives for an individual who’s in that position, therefore, are on a very short timeframe, and yet investments often pay off over the long term. So what creates the incentive to pursue those things where you have to be patient about the capital, but you can end up with higher annual returns because of it.

The second is speed of decision-making. Oftentimes, people think of family businesses potentially being slow. However, that doesn’t have to be. Indeed, they can make decisions extraordinarily quickly because they may have a smaller shareholder base. The third is the ability to pursue unconventional strategies. You’ll find many family businesses over time end up in what I’m going to call a conglomerate, a multi-business structure because they can mitigate some risks by investing in other places. And the fourth is values-driven, pride of ownership if you will.

Darius Teter: So that’s patient capital, speed of decision-making, unconventional strategies, and values. Four advantages that we’re going to hear play out in Naomi and Annette’s story.

I’m interested in exploring the separation between the mother-daughter relationship and the boss-subordinate relationship. How does that work out for you Annette?

Annette Kimitei: I think with years of practice it switches automatically. The minute I get into the lift in the office, she becomes Madame Naomi. And my dad, even my kids call him chairman as long as they’re in the office. We learned that a lot. And then when you get into the car, she can switch back to mom.

Darius Teter: So you get in the elevator and now you’re in a professional relationship with your mother, with your siblings. You go home, and it’s back to being family. I don’t imagine that happened overnight. What was the effect of working with your sisters? Was that easy? Was it hard? Is it changing over time? I’m really curious.

Annette Kimitei: I came into the business very young, and despite the fact that I had gone to university, I still went and did the very clerical roles for nearly three years. Grew to HR, became an HR assistant, became an HR manager. Again, got HR and training manager, then again became general manager, again became a HR director. So my role changed. What happened is the business no longer remained a family business. As the family was growing, we were hiring professionals, professional accountants, and professional people in operations. So you’re not going to call mom, mom. And believe me, when it comes to work, if I don’t perform, she might look nice and cute right now, but she can bite. And she bites the same if it is myself or at the general manager who’s non-family or another manager or my sisters. There’s no discrimination when it comes to issues of performance.

Darius Teter: I think that’s fascinating. So part of what’s going on here is that for you, Naomi, it was important for you to treat all your staff the same and not to distinguish between family members of staff and non-family members. Is that your philosophy?

Naomi Kipkorir: Annette joined the company even before me. And as the other siblings also joined when I was there, they still had to learn that there’s a difference between being at home and also being in the office. Like now, what I’m doing with my grandchildren, I allow them to come to the office, and they know when you come to the office, if there’s a meeting, you sit and keep quiet. I’m training them when they are still young because that is the opportunity I didn’t have when I was bringing up my children. It is not very easy for us even to hold our board meetings and for them to be purely business issues discussed. So many times my husband has to keep on reminding us, “This is a board meeting, no mom, no dad. Let us be serious.” So it has been a journey. I say that where we have reached it is because of what we have gone through and even the training that we have also undertaken.

Darius Teter: Peter says that proactive engagement and training is key. In fact, although there’s no one antidote to issues that arise in family businesses, Peter believes that many problems can be addressed through three core practices; education, transparency, and communication.

Peter Francis: It’s so powerful for family members and owners to have a language to use so that they can communicate. If you’re having a conversation about the business at home, you might say, “You know what? We’re home, we should be wearing our family hat, not our business hat.” And then finally, communication. By that, I don’t mean just communicating but also learning how to communicate. That is a muscle that we can strengthen in the family. And so, that gives people a chance to be better at this as they go forward.

Darius Teter: Naomi and Annette have undergone training for everything from how to serve on a board, to how to differentiate between the family and the business. And it was during one of these coaching sessions that Naomi first heard about family succession planning.

Naomi Kipkorir: We have held workshops with consultants that are also experts in family businesses. I remember the first time we were told that I was running so many companies at the same time as the CEO, and I needed to let go of some of the responsibilities and the big sister was supposed to take over. I saw emotions arise. My two daughters, one of them was in tears. “Mom, you can’t leave. How is it going to be?” So emotions came and we were able to overcome that, but we took some time for them to digest and know that with or without mom, there at the top, a time had to come that I had to let go of some of the responsibilities.

Darius Teter: Tears from the family at the idea of Madam Naomi leaving might sound extreme, but the family had been through so much together. Senaca prioritized seeking expert advice because the business had been burned once before.

Naomi Kipkorir: There’s a time that we merged with an European company, and we had an independent board, and we had expatriates on the board. We were represented in so many countries, in Canada, in Europe, in Ireland. When it came to the board, we were so naive because we were just running as a small family business that now was almost swallowed by the big company from Ireland.

Darius Teter: They came in and bought a majority share, you are minority owners, but you had no representation on the board.

Naomi Kipkorir: Me, Annette, and my husband, the three of us were on the board, but we were toothless.

Annette Kimitei: It was a very painful lesson, but a lesson we needed to learn all the same because when we merged, we gave, we didn’t even sell, we gave majority shareholding, and we took a step back and some of us went to pursue other businesses.

Darius Teter: Senaca embarked on this journey because they were keen to explore new markets. In Kenya, residential security is less profitable, and late payments from state-owned companies led to cash flow issues. So they figured, “Why not find an international partner and start targeting corporate and multinational clients?”

Annette Kimitei: It started out very well. We started getting high-profile clients. We had expatriates working with us, but what happened is not everything that works in Europe is a copy-paste, that you can just cut it and paste it in Africa. And particularly even what we do in Kenya is not what we do in Uganda. The guards in Uganda we have are armed, in Kenya they are not armed. One of the mistakes we did as a board is we didn’t ask bold questions. We didn’t give that governance element to be able to ask, “Is this the right solution for this market?”

Darius Teter: The European company didn’t understand the local market, but you didn’t feel that you had the voice or the stature to stop these guys in the board meeting and say, “Hey, wait a minute. This idea is not going to work in Kenya.”

Annette Kimitei: We tried to highlight it. We did papers, we did comment, but again, what mom was mentioning was we either did not respect our positions as directors and probably took a backseat like employees giving a report, you know? So the result of all this was that the business ended up being overburdened financially. You have all these megaprojects, technology to run airports like the way it’s done in Europe. In Kenya, the airport is so tiny, and they didn’t care for technology at that time. So you’ve gone into heavy debt. And within no time, that debt caught up. So we were wondering because the management accounts are seeing profits, yet you can tell the cash flow strain is so bad. The clients are paying on time, and that was because we were recording losses. These partners from Europe, when they realized the debt was too much and what they owed the government, especially when it comes to taxes and loans and auctioneers were coming on board, they just packed their bags. Literally, this is a funny story, but they packed their bags and resigned on an email, and sold the shares at a very, very, minimal amount.

Darius Teter: This was a make or break moment, a reckoning for the family and for the business.

Naomi Kipkorir: They left the company under big debts. So by the time we were coming back as a family, we were coming back to a company that was supposed to be a basket case, and we were supposed to be auctioned. But then the family came together and we asked ourselves so many questions. “What was the problem?” The first one was we were not present. We were not even serving on the board as we were just listening to the partners and just doing what they were saying.

Annette Kimitei: We had to hire account consultants, auditors. And when they went through the books, they said, “Throw out this business, you can’t recover it.” I remember one of them, an international firm, actually bought mama a book that said “How To Know When To Give Up.“ But I’m grateful because we had another local auditor who came and said, “The business looks bad, but with the expertise you have, you know this market. Come back together as a family, utilize your different strengths, and it’s going to be a painful six months, but you can naturally help this.”

Darius Teter: What the consultants saw was that with their combined backgrounds; chairman John from the police, Naomi in sales, Annette in strategic management, and the two sisters in legal and accounting, this family had the tools to turn the business around.

Annette Kimitei: The family was the problem in terms of our governance and our lack of knowledge and drive to be able to understand what corporate governance requires out of us. But again, the family spirit and the values and the passion we have for the business and our reputation is, again, what saved the business. Fast-forward to who we are right now, Senaca is one of the most respected security companies across East Africa.

Darius Teter: Those family values that Peter Francis highlighted would prove to be the secret sauce that brought Senaca back from the brink. And along the way, they created a company that would be worth handing down to the next generation. But because of their rollercoaster experience, when the time came to start thinking about family succession planning, Naomi was a little hesitant.

Naomi Kipkorir: My initial reaction was fear after our previous experience of if I let go, maybe we would fail again. I was troubled a lot because I was not ready for that. But by and by, I could try to plan my weeks, my days, it was not adding up, and I saw that I was not adding a lot of value to some of the companies. So I had to let go of two of the companies. It was never taken lightly, but we kept on talking about it over the dinner table, and they have now come to buy in and they are now supporting the plan of me handing over the baton to Annette.

Darius Teter: Annette, I’d love to hear this story from your side. Was it a shock to you that your mother was thinking it was time for you to take over?

Annette Kimitei: I’m always more comfortable as Madame fix-it. I like fixing where there’s a problem, but I didn’t want to take the leadership position. So at this time, yes, when mom said… We had the family business consultant, and he gave us that tough news and said, “I’ve seen your qualifications, I’ve seen your experience, it’s time.” And of course, for me, I said no, I’m not ready for it.

Darius Teter: So you doubted yourself?

Annette Kimitei: Yes, I did doubt myself, I’ll not lie.

Darius Teter: Naomi, did you doubt Annette?

Naomi Kipkorir: I didn’t because I could see beyond what she could see. I knew her capacity, and I knew she was equal to the task.

Darius Teter: That’s interesting. So Annette, did that give you confidence that your mother believed in you?

Annette Kimitei: No, no, no, not too much. I think succession is not an event, it’s a process. What happened is when I was supposed to be called MD, I actually asked that I be called deputy MD just to warm up to the seat. So for around three years, I was a deputy MD, executing everything an MD does, but just wanting to hide. And the reason for that is, number one, from an industry perspective, I’m one of the youngest managing directors. Number two, I have a really tiny frame and this is the security industry. Most of the people running security companies are way older. They are my father’s age. They are brigadiers, majors. And these are the people that I was going to meet with. And then that is even for my voice, I didn’t have that commanding security voice. So I had a bunch of excuses, Darius, very nice excuses as to why to hide.

Darius Teter: I don’t know. Honestly, those don’t sound like excuses, those sound like serious rocks and boulders that you have to push up a hill. Because it was not just about how you felt, your self-confidence, it was about how you felt you would be perceived in the market.

Annette Kimitei: I always joke that the general manager we currently have is an amazing guy, but he’s very big, and he’s ex-police, and he’s ex-CID. So every time we go to a meeting, guys will be like, “Hey, hello, Mr. MD.” It’s always an assumption that I’m probably his secretary because I’m a little bit tinier. And then by the time I introduce myself, somebody will say, “Oh, so you are Annette. Yeah, we’ve heard of Annette. We just thought she’s bigger.”

Darius Teter: The transition of leadership in any business affects more than just the C-suite executives. And Naomi knew that getting employee buy-in would be vital.

Naomi Kipkorir: My leadership style and Annette’s are very different. I remember even the members of staff calling me and saying, “If you go, this company is done.” Annette is very aggressive. Annette is very strict. I think they were used to the way I was leading them. Everybody was afraid, but then I had to let Annette prove that the company also needed to change the way it was led because things were also changing and the market demands were also changing. Annette, she’s a risk-taker, so she could bring in so many other different things, so many products. And some of them are like, “Are we ready for this?” But she was pushing and I could see the results. They are telling me, “Now it’s not change, it’s even transformation.”

Darius Teter: With Annette now in the managing director role, Senaca is diversifying, and they’ve gained a new perspective on the importance of a well-functioning board.

Annette Kimitei: The ideas come from everywhere, but all these ideas have to be conceptualized. And then we place together on the table the different concepts. And it is the board that’s now going to say, “Out of the five ideas, we felt that these two can work. This one can start this year. And once this one is stable, now we can move on to the next one.”

Darius Teter: So you’re trying to make sure that the proposals are supported by analysis to take some of the emotion out of the decisions?

Annette Kimitei: I feel most comfortable with a project if she says yes. Because if I can convince the whole world. But if I convince the chairman and Madame Naomi or mom, then I know I have worked my figures out.

Darius Teter: Has there ever been a proposal that you took to the board where it was shot down and you still are convinced that you’re right?

Annette Kimitei: Of course. This year is when they finally accepted a concept of diversifying to technology and risk when the numbers were shown. I’ll tell you what I did wrong the last two years was, I saw the dream, but I didn’t have the data to back it up to show that it’s not just the product, the expenses associated with this, at this amount. And guess what? The profit is this. I just did a small pilot by bringing in a few of the dogs, a little bit of the technology, and the bottom line really improved. So I’m really excited because they didn’t say no, they said, “Test this business model.” Because we are moving from 93% guarding and only 7% were other services. Now we are moving it to 30% guarding, 30% technology, and 30% risk. Just one year of doing that, our profits grew by nearly 6%.

Darius Teter: I love this story because that’s what a good board should do, is say, “This is an interesting idea, but you haven’t tested it. Go out and test it. Come back to us with the results, and then we’ll decide.” Would you say, Naomi, that this decrease in the guarding business and increase in risk management business and technology could not have happened without Annette’s leadership in driving for change?

Naomi Kipkorir: Yes, we were still calling ourselves the old school, and we just wanted to manage the guarding business. We worked in the government, we have our pension, so we were not really looking for money. We were not greedy for that kind of growth when it comes to a business. But we have seen that through her efforts and her ambition, she has really made the company now look like, “Oh, this is something that even outlives us, and it can even grow bigger.”

Darius Teter: Senaca is now two years into the transition, and they’re putting a major focus on solidifying their corporate governance.

Annette Kimitei: For a long time, we didn’t understand what is manager, what is director, what is shareholder. So when it comes to our corporate governance, we engaged an external consultant again this time. What we are working on is the family constitution, the family office, the shareholders’ agreement. We also want to bring in advisory board members. We’re bringing in three this year as board advisors. And then based on that is now when we move into independent directors. I think because of our previous experience with our European partners, we thought it’s good for us to be able to engage consultants. We’re going to see what are the skills we are missing in the business, what are the skills that we are missing in the board, and how do we bring in the right people. How do we induct them? How do we monitor their performance?

Naomi Kipkorir: We have seen where we’ve always gone wrong, and we are saying, “If we knew what we know today five years ago, we would be having even the independent boards and other boards that would be able to drive and steer the company to different levels.”