- INTERPERSONAL SKILLS

- Decision-Making and Problem Solving

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Interpersonal Skills:

- A - Z List of Interpersonal Skills

- Interpersonal Skills Self-Assessment

- Communication Skills

- Emotional Intelligence

- Conflict Resolution and Mediation Skills

- Customer Service Skills

- Team-Working, Groups and Meetings

Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

- Effective Decision Making

- Decision-Making Framework

- Introduction to Problem Solving

Identifying and Structuring Problems

Investigating Ideas and Solutions

Implementing a Solution and Feedback

- Creative Problem-Solving

Social Problem-Solving

- Negotiation and Persuasion Skills

- Personal and Romantic Relationship Skills

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

The SkillsYouNeed Guide to Interpersonal Skills

Making decisions and solving problems are two key areas in life, whether you are at home or at work. Whatever you’re doing, and wherever you are, you are faced with countless decisions and problems, both small and large, every day.

Many decisions and problems are so small that we may not even notice them. Even small decisions, however, can be overwhelming to some people. They may come to a halt as they consider their dilemma and try to decide what to do.

Small and Large Decisions

In your day-to-day life you're likely to encounter numerous 'small decisions', including, for example:

Tea or coffee?

What shall I have in my sandwich? Or should I have a salad instead today?

What shall I wear today?

Larger decisions may occur less frequently but may include:

Should we repaint the kitchen? If so, what colour?

Should we relocate?

Should I propose to my partner? Do I really want to spend the rest of my life with him/her?

These decisions, and others like them, may take considerable time and effort to make.

The relationship between decision-making and problem-solving is complex. Decision-making is perhaps best thought of as a key part of problem-solving: one part of the overall process.

Our approach at Skills You Need is to set out a framework to help guide you through the decision-making process. You won’t always need to use the whole framework, or even use it at all, but you may find it useful if you are a bit ‘stuck’ and need something to help you make a difficult decision.

Decision Making

Effective Decision-Making

This page provides information about ways of making a decision, including basing it on logic or emotion (‘gut feeling’). It also explains what can stop you making an effective decision, including too much or too little information, and not really caring about the outcome.

A Decision-Making Framework

This page sets out one possible framework for decision-making.

The framework described is quite extensive, and may seem quite formal. But it is also a helpful process to run through in a briefer form, for smaller problems, as it will help you to make sure that you really do have all the information that you need.

Problem Solving

Introduction to Problem-Solving

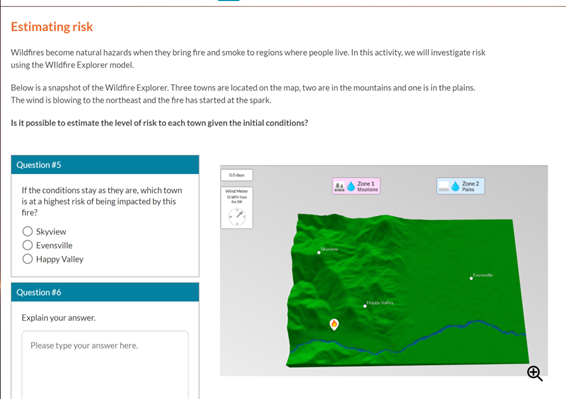

This page provides a general introduction to the idea of problem-solving. It explores the idea of goals (things that you want to achieve) and barriers (things that may prevent you from achieving your goals), and explains the problem-solving process at a broad level.

The first stage in solving any problem is to identify it, and then break it down into its component parts. Even the biggest, most intractable-seeming problems, can become much more manageable if they are broken down into smaller parts. This page provides some advice about techniques you can use to do so.

Sometimes, the possible options to address your problem are obvious. At other times, you may need to involve others, or think more laterally to find alternatives. This page explains some principles, and some tools and techniques to help you do so.

Having generated solutions, you need to decide which one to take, which is where decision-making meets problem-solving. But once decided, there is another step: to deliver on your decision, and then see if your chosen solution works. This page helps you through this process.

‘Social’ problems are those that we encounter in everyday life, including money trouble, problems with other people, health problems and crime. These problems, like any others, are best solved using a framework to identify the problem, work out the options for addressing it, and then deciding which option to use.

This page provides more information about the key skills needed for practical problem-solving in real life.

Further Reading from Skills You Need

The Skills You Need Guide to Interpersonal Skills eBooks.

Develop your interpersonal skills with our series of eBooks. Learn about and improve your communication skills, tackle conflict resolution, mediate in difficult situations, and develop your emotional intelligence.

Guiding you through the key skills needed in life

As always at Skills You Need, our approach to these key skills is to provide practical ways to manage the process, and to develop your skills.

Neither problem-solving nor decision-making is an intrinsically difficult process and we hope you will find our pages useful in developing your skills.

Start with: Decision Making Problem Solving

See also: Improving Communication Interpersonal Communication Skills Building Confidence

Decision Making vs. Problem Solving

What's the difference.

Decision making and problem solving are two closely related concepts that are essential in both personal and professional settings. While decision making refers to the process of selecting the best course of action among various alternatives, problem solving involves identifying and resolving issues or obstacles that hinder progress towards a desired outcome. Decision making often involves evaluating different options based on their potential outcomes and consequences, while problem solving requires analyzing the root causes of a problem and developing effective strategies to overcome it. Both skills require critical thinking, creativity, and the ability to weigh pros and cons. Ultimately, decision making and problem solving are interconnected and complementary processes that enable individuals to navigate complex situations and achieve desired goals.

| Attribute | Decision Making | Problem Solving |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The process of selecting the best course of action among available alternatives. | The process of finding solutions to complex or difficult issues or challenges. |

| Goal | To make a choice that leads to a desired outcome or solution. | To find a solution or resolution to a specific problem or challenge. |

| Approach | Based on evaluating options and making a rational decision. | Based on analyzing the problem, identifying possible solutions, and selecting the most appropriate one. |

| Process | Includes gathering information, evaluating alternatives, and making a decision. | Includes problem identification, analysis, generating solutions, and implementing the chosen solution. |

| Focus | Primarily on making choices among available alternatives. | Primarily on finding solutions to specific problems or challenges. |

| Timeframe | Can be short-term or long-term decision making. | Can be short-term or long-term problem solving. |

| Complexity | Can involve complex decision-making models and frameworks. | Can involve complex problem-solving techniques and methodologies. |

| Outcome | Results in a decision or choice being made. | Results in a solution or resolution to the problem. |

Further Detail

Introduction.

Decision making and problem solving are two essential cognitive processes that individuals and organizations engage in to navigate through various challenges and achieve desired outcomes. While they are distinct processes, decision making and problem solving share several attributes and are often interconnected. In this article, we will explore the similarities and differences between decision making and problem solving, highlighting their key attributes and how they contribute to effective problem-solving and decision-making processes.

Definition and Purpose

Decision making involves selecting a course of action from multiple alternatives based on available information, preferences, and goals. It is a cognitive process that individuals use to make choices and reach conclusions. On the other hand, problem solving refers to the process of finding solutions to specific issues or challenges. It involves identifying, analyzing, and resolving problems to achieve desired outcomes.

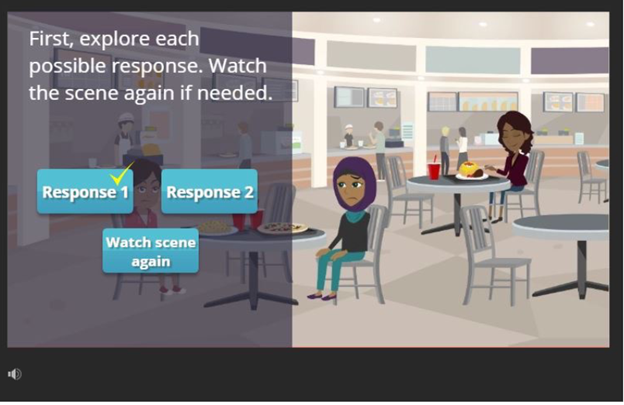

Both decision making and problem solving share the purpose of achieving a desired outcome or resolving a particular situation. They require individuals to think critically, evaluate options, and consider potential consequences. While decision making focuses on choosing the best course of action, problem solving emphasizes finding effective solutions to specific problems or challenges.

Attributes of Decision Making

Decision making involves several key attributes that contribute to its effectiveness:

- Rationality: Decision making is often based on rational thinking, where individuals evaluate available information, weigh pros and cons, and make logical choices.

- Subjectivity: Decision making is influenced by personal preferences, values, and biases. Individuals may prioritize certain factors or options based on their subjective judgment.

- Uncertainty: Many decisions are made under conditions of uncertainty, where individuals lack complete information or face unpredictable outcomes. Decision makers must assess risks and make informed judgments.

- Time Constraints: Decision making often occurs within time constraints, requiring individuals to make choices efficiently and effectively.

- Trade-offs: Decision making involves considering trade-offs between different options, as individuals must prioritize certain factors or outcomes over others.

Attributes of Problem Solving

Problem solving also encompasses several key attributes that contribute to its effectiveness:

- Analytical Thinking: Problem solving requires individuals to analyze and break down complex problems into smaller components, facilitating a deeper understanding of the issue at hand.

- Creativity: Effective problem solving often involves thinking outside the box and generating innovative solutions. It requires individuals to explore alternative perspectives and consider unconventional approaches.

- Collaboration: Problem solving can benefit from collaboration and teamwork, as diverse perspectives and expertise can contribute to more comprehensive and effective solutions.

- Iterative Process: Problem solving is often an iterative process, where individuals continuously evaluate and refine their solutions based on feedback and new information.

- Implementation: Problem solving is not complete without implementing the chosen solution. Individuals must take action and monitor the outcomes to ensure the problem is effectively resolved.

Interconnection and Overlap

While decision making and problem solving are distinct processes, they are interconnected and often overlap. Decision making is frequently a part of the problem-solving process, as individuals must make choices and select the most appropriate solution to address a specific problem. Similarly, problem solving is inherent in decision making, as individuals must identify and analyze problems or challenges before making informed choices.

Moreover, both decision making and problem solving require critical thinking skills, the ability to evaluate information, and the consideration of potential consequences. They both involve a systematic approach to gather and analyze relevant data, explore alternatives, and assess the potential risks and benefits of different options.

Decision making and problem solving are fundamental cognitive processes that individuals and organizations engage in to navigate through challenges and achieve desired outcomes. While decision making focuses on selecting the best course of action, problem solving emphasizes finding effective solutions to specific problems or challenges. Both processes share attributes such as rationality, subjectivity, uncertainty, time constraints, and trade-offs (in decision making), as well as analytical thinking, creativity, collaboration, iterative process, and implementation (in problem solving).

Understanding the similarities and differences between decision making and problem solving can enhance our ability to approach complex situations effectively. By leveraging the attributes of both processes, individuals and organizations can make informed choices, address challenges, and achieve desired outcomes.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

How to master the seven-step problem-solving process

In this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , Simon London speaks with Charles Conn, CEO of venture-capital firm Oxford Sciences Innovation, and McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin about the complexities of different problem-solving strategies.

Podcast transcript

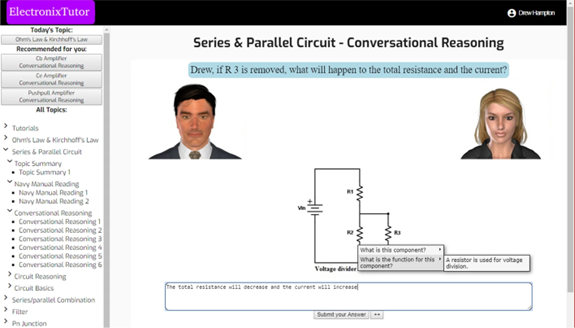

Simon London: Hello, and welcome to this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , with me, Simon London. What’s the number-one skill you need to succeed professionally? Salesmanship, perhaps? Or a facility with statistics? Or maybe the ability to communicate crisply and clearly? Many would argue that at the very top of the list comes problem solving: that is, the ability to think through and come up with an optimal course of action to address any complex challenge—in business, in public policy, or indeed in life.

Looked at this way, it’s no surprise that McKinsey takes problem solving very seriously, testing for it during the recruiting process and then honing it, in McKinsey consultants, through immersion in a structured seven-step method. To discuss the art of problem solving, I sat down in California with McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin and also with Charles Conn. Charles is a former McKinsey partner, entrepreneur, executive, and coauthor of the book Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything [John Wiley & Sons, 2018].

Charles and Hugo, welcome to the podcast. Thank you for being here.

Hugo Sarrazin: Our pleasure.

Charles Conn: It’s terrific to be here.

Simon London: Problem solving is a really interesting piece of terminology. It could mean so many different things. I have a son who’s a teenage climber. They talk about solving problems. Climbing is problem solving. Charles, when you talk about problem solving, what are you talking about?

Charles Conn: For me, problem solving is the answer to the question “What should I do?” It’s interesting when there’s uncertainty and complexity, and when it’s meaningful because there are consequences. Your son’s climbing is a perfect example. There are consequences, and it’s complicated, and there’s uncertainty—can he make that grab? I think we can apply that same frame almost at any level. You can think about questions like “What town would I like to live in?” or “Should I put solar panels on my roof?”

You might think that’s a funny thing to apply problem solving to, but in my mind it’s not fundamentally different from business problem solving, which answers the question “What should my strategy be?” Or problem solving at the policy level: “How do we combat climate change?” “Should I support the local school bond?” I think these are all part and parcel of the same type of question, “What should I do?”

I’m a big fan of structured problem solving. By following steps, we can more clearly understand what problem it is we’re solving, what are the components of the problem that we’re solving, which components are the most important ones for us to pay attention to, which analytic techniques we should apply to those, and how we can synthesize what we’ve learned back into a compelling story. That’s all it is, at its heart.

I think sometimes when people think about seven steps, they assume that there’s a rigidity to this. That’s not it at all. It’s actually to give you the scope for creativity, which often doesn’t exist when your problem solving is muddled.

Simon London: You were just talking about the seven-step process. That’s what’s written down in the book, but it’s a very McKinsey process as well. Without getting too deep into the weeds, let’s go through the steps, one by one. You were just talking about problem definition as being a particularly important thing to get right first. That’s the first step. Hugo, tell us about that.

Hugo Sarrazin: It is surprising how often people jump past this step and make a bunch of assumptions. The most powerful thing is to step back and ask the basic questions—“What are we trying to solve? What are the constraints that exist? What are the dependencies?” Let’s make those explicit and really push the thinking and defining. At McKinsey, we spend an enormous amount of time in writing that little statement, and the statement, if you’re a logic purist, is great. You debate. “Is it an ‘or’? Is it an ‘and’? What’s the action verb?” Because all these specific words help you get to the heart of what matters.

Want to subscribe to The McKinsey Podcast ?

Simon London: So this is a concise problem statement.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah. It’s not like “Can we grow in Japan?” That’s interesting, but it is “What, specifically, are we trying to uncover in the growth of a product in Japan? Or a segment in Japan? Or a channel in Japan?” When you spend an enormous amount of time, in the first meeting of the different stakeholders, debating this and having different people put forward what they think the problem definition is, you realize that people have completely different views of why they’re here. That, to me, is the most important step.

Charles Conn: I would agree with that. For me, the problem context is critical. When we understand “What are the forces acting upon your decision maker? How quickly is the answer needed? With what precision is the answer needed? Are there areas that are off limits or areas where we would particularly like to find our solution? Is the decision maker open to exploring other areas?” then you not only become more efficient, and move toward what we call the critical path in problem solving, but you also make it so much more likely that you’re not going to waste your time or your decision maker’s time.

How often do especially bright young people run off with half of the idea about what the problem is and start collecting data and start building models—only to discover that they’ve really gone off half-cocked.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah.

Charles Conn: And in the wrong direction.

Simon London: OK. So step one—and there is a real art and a structure to it—is define the problem. Step two, Charles?

Charles Conn: My favorite step is step two, which is to use logic trees to disaggregate the problem. Every problem we’re solving has some complexity and some uncertainty in it. The only way that we can really get our team working on the problem is to take the problem apart into logical pieces.

What we find, of course, is that the way to disaggregate the problem often gives you an insight into the answer to the problem quite quickly. I love to do two or three different cuts at it, each one giving a bit of a different insight into what might be going wrong. By doing sensible disaggregations, using logic trees, we can figure out which parts of the problem we should be looking at, and we can assign those different parts to team members.

Simon London: What’s a good example of a logic tree on a sort of ratable problem?

Charles Conn: Maybe the easiest one is the classic profit tree. Almost in every business that I would take a look at, I would start with a profit or return-on-assets tree. In its simplest form, you have the components of revenue, which are price and quantity, and the components of cost, which are cost and quantity. Each of those can be broken out. Cost can be broken into variable cost and fixed cost. The components of price can be broken into what your pricing scheme is. That simple tree often provides insight into what’s going on in a business or what the difference is between that business and the competitors.

If we add the leg, which is “What’s the asset base or investment element?”—so profit divided by assets—then we can ask the question “Is the business using its investments sensibly?” whether that’s in stores or in manufacturing or in transportation assets. I hope we can see just how simple this is, even though we’re describing it in words.

When I went to work with Gordon Moore at the Moore Foundation, the problem that he asked us to look at was “How can we save Pacific salmon?” Now, that sounds like an impossible question, but it was amenable to precisely the same type of disaggregation and allowed us to organize what became a 15-year effort to improve the likelihood of good outcomes for Pacific salmon.

Simon London: Now, is there a danger that your logic tree can be impossibly large? This, I think, brings us onto the third step in the process, which is that you have to prioritize.

Charles Conn: Absolutely. The third step, which we also emphasize, along with good problem definition, is rigorous prioritization—we ask the questions “How important is this lever or this branch of the tree in the overall outcome that we seek to achieve? How much can I move that lever?” Obviously, we try and focus our efforts on ones that have a big impact on the problem and the ones that we have the ability to change. With salmon, ocean conditions turned out to be a big lever, but not one that we could adjust. We focused our attention on fish habitats and fish-harvesting practices, which were big levers that we could affect.

People spend a lot of time arguing about branches that are either not important or that none of us can change. We see it in the public square. When we deal with questions at the policy level—“Should you support the death penalty?” “How do we affect climate change?” “How can we uncover the causes and address homelessness?”—it’s even more important that we’re focusing on levers that are big and movable.

Would you like to learn more about our Strategy & Corporate Finance Practice ?

Simon London: Let’s move swiftly on to step four. You’ve defined your problem, you disaggregate it, you prioritize where you want to analyze—what you want to really look at hard. Then you got to the work plan. Now, what does that mean in practice?

Hugo Sarrazin: Depending on what you’ve prioritized, there are many things you could do. It could be breaking the work among the team members so that people have a clear piece of the work to do. It could be defining the specific analyses that need to get done and executed, and being clear on time lines. There’s always a level-one answer, there’s a level-two answer, there’s a level-three answer. Without being too flippant, I can solve any problem during a good dinner with wine. It won’t have a whole lot of backing.

Simon London: Not going to have a lot of depth to it.

Hugo Sarrazin: No, but it may be useful as a starting point. If the stakes are not that high, that could be OK. If it’s really high stakes, you may need level three and have the whole model validated in three different ways. You need to find a work plan that reflects the level of precision, the time frame you have, and the stakeholders you need to bring along in the exercise.

Charles Conn: I love the way you’ve described that, because, again, some people think of problem solving as a linear thing, but of course what’s critical is that it’s iterative. As you say, you can solve the problem in one day or even one hour.

Charles Conn: We encourage our teams everywhere to do that. We call it the one-day answer or the one-hour answer. In work planning, we’re always iterating. Every time you see a 50-page work plan that stretches out to three months, you know it’s wrong. It will be outmoded very quickly by that learning process that you described. Iterative problem solving is a critical part of this. Sometimes, people think work planning sounds dull, but it isn’t. It’s how we know what’s expected of us and when we need to deliver it and how we’re progressing toward the answer. It’s also the place where we can deal with biases. Bias is a feature of every human decision-making process. If we design our team interactions intelligently, we can avoid the worst sort of biases.

Simon London: Here we’re talking about cognitive biases primarily, right? It’s not that I’m biased against you because of your accent or something. These are the cognitive biases that behavioral sciences have shown we all carry around, things like anchoring, overoptimism—these kinds of things.

Both: Yeah.

Charles Conn: Availability bias is the one that I’m always alert to. You think you’ve seen the problem before, and therefore what’s available is your previous conception of it—and we have to be most careful about that. In any human setting, we also have to be careful about biases that are based on hierarchies, sometimes called sunflower bias. I’m sure, Hugo, with your teams, you make sure that the youngest team members speak first. Not the oldest team members, because it’s easy for people to look at who’s senior and alter their own creative approaches.

Hugo Sarrazin: It’s helpful, at that moment—if someone is asserting a point of view—to ask the question “This was true in what context?” You’re trying to apply something that worked in one context to a different one. That can be deadly if the context has changed, and that’s why organizations struggle to change. You promote all these people because they did something that worked well in the past, and then there’s a disruption in the industry, and they keep doing what got them promoted even though the context has changed.

Simon London: Right. Right.

Hugo Sarrazin: So it’s the same thing in problem solving.

Charles Conn: And it’s why diversity in our teams is so important. It’s one of the best things about the world that we’re in now. We’re likely to have people from different socioeconomic, ethnic, and national backgrounds, each of whom sees problems from a slightly different perspective. It is therefore much more likely that the team will uncover a truly creative and clever approach to problem solving.

Simon London: Let’s move on to step five. You’ve done your work plan. Now you’ve actually got to do the analysis. The thing that strikes me here is that the range of tools that we have at our disposal now, of course, is just huge, particularly with advances in computation, advanced analytics. There’s so many things that you can apply here. Just talk about the analysis stage. How do you pick the right tools?

Charles Conn: For me, the most important thing is that we start with simple heuristics and explanatory statistics before we go off and use the big-gun tools. We need to understand the shape and scope of our problem before we start applying these massive and complex analytical approaches.

Simon London: Would you agree with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: I agree. I think there are so many wonderful heuristics. You need to start there before you go deep into the modeling exercise. There’s an interesting dynamic that’s happening, though. In some cases, for some types of problems, it is even better to set yourself up to maximize your learning. Your problem-solving methodology is test and learn, test and learn, test and learn, and iterate. That is a heuristic in itself, the A/B testing that is used in many parts of the world. So that’s a problem-solving methodology. It’s nothing different. It just uses technology and feedback loops in a fast way. The other one is exploratory data analysis. When you’re dealing with a large-scale problem, and there’s so much data, I can get to the heuristics that Charles was talking about through very clever visualization of data.

You test with your data. You need to set up an environment to do so, but don’t get caught up in neural-network modeling immediately. You’re testing, you’re checking—“Is the data right? Is it sound? Does it make sense?”—before you launch too far.

Simon London: You do hear these ideas—that if you have a big enough data set and enough algorithms, they’re going to find things that you just wouldn’t have spotted, find solutions that maybe you wouldn’t have thought of. Does machine learning sort of revolutionize the problem-solving process? Or are these actually just other tools in the toolbox for structured problem solving?

Charles Conn: It can be revolutionary. There are some areas in which the pattern recognition of large data sets and good algorithms can help us see things that we otherwise couldn’t see. But I do think it’s terribly important we don’t think that this particular technique is a substitute for superb problem solving, starting with good problem definition. Many people use machine learning without understanding algorithms that themselves can have biases built into them. Just as 20 years ago, when we were doing statistical analysis, we knew that we needed good model definition, we still need a good understanding of our algorithms and really good problem definition before we launch off into big data sets and unknown algorithms.

Simon London: Step six. You’ve done your analysis.

Charles Conn: I take six and seven together, and this is the place where young problem solvers often make a mistake. They’ve got their analysis, and they assume that’s the answer, and of course it isn’t the answer. The ability to synthesize the pieces that came out of the analysis and begin to weave those into a story that helps people answer the question “What should I do?” This is back to where we started. If we can’t synthesize, and we can’t tell a story, then our decision maker can’t find the answer to “What should I do?”

Simon London: But, again, these final steps are about motivating people to action, right?

Charles Conn: Yeah.

Simon London: I am slightly torn about the nomenclature of problem solving because it’s on paper, right? Until you motivate people to action, you actually haven’t solved anything.

Charles Conn: I love this question because I think decision-making theory, without a bias to action, is a waste of time. Everything in how I approach this is to help people take action that makes the world better.

Simon London: Hence, these are absolutely critical steps. If you don’t do this well, you’ve just got a bunch of analysis.

Charles Conn: We end up in exactly the same place where we started, which is people speaking across each other, past each other in the public square, rather than actually working together, shoulder to shoulder, to crack these important problems.

Simon London: In the real world, we have a lot of uncertainty—arguably, increasing uncertainty. How do good problem solvers deal with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: At every step of the process. In the problem definition, when you’re defining the context, you need to understand those sources of uncertainty and whether they’re important or not important. It becomes important in the definition of the tree.

You need to think carefully about the branches of the tree that are more certain and less certain as you define them. They don’t have equal weight just because they’ve got equal space on the page. Then, when you’re prioritizing, your prioritization approach may put more emphasis on things that have low probability but huge impact—or, vice versa, may put a lot of priority on things that are very likely and, hopefully, have a reasonable impact. You can introduce that along the way. When you come back to the synthesis, you just need to be nuanced about what you’re understanding, the likelihood.

Often, people lack humility in the way they make their recommendations: “This is the answer.” They’re very precise, and I think we would all be well-served to say, “This is a likely answer under the following sets of conditions” and then make the level of uncertainty clearer, if that is appropriate. It doesn’t mean you’re always in the gray zone; it doesn’t mean you don’t have a point of view. It just means that you can be explicit about the certainty of your answer when you make that recommendation.

Simon London: So it sounds like there is an underlying principle: “Acknowledge and embrace the uncertainty. Don’t pretend that it isn’t there. Be very clear about what the uncertainties are up front, and then build that into every step of the process.”

Hugo Sarrazin: Every step of the process.

Simon London: Yeah. We have just walked through a particular structured methodology for problem solving. But, of course, this is not the only structured methodology for problem solving. One that is also very well-known is design thinking, which comes at things very differently. So, Hugo, I know you have worked with a lot of designers. Just give us a very quick summary. Design thinking—what is it, and how does it relate?

Hugo Sarrazin: It starts with an incredible amount of empathy for the user and uses that to define the problem. It does pause and go out in the wild and spend an enormous amount of time seeing how people interact with objects, seeing the experience they’re getting, seeing the pain points or joy—and uses that to infer and define the problem.

Simon London: Problem definition, but out in the world.

Hugo Sarrazin: With an enormous amount of empathy. There’s a huge emphasis on empathy. Traditional, more classic problem solving is you define the problem based on an understanding of the situation. This one almost presupposes that we don’t know the problem until we go see it. The second thing is you need to come up with multiple scenarios or answers or ideas or concepts, and there’s a lot of divergent thinking initially. That’s slightly different, versus the prioritization, but not for long. Eventually, you need to kind of say, “OK, I’m going to converge again.” Then you go and you bring things back to the customer and get feedback and iterate. Then you rinse and repeat, rinse and repeat. There’s a lot of tactile building, along the way, of prototypes and things like that. It’s very iterative.

Simon London: So, Charles, are these complements or are these alternatives?

Charles Conn: I think they’re entirely complementary, and I think Hugo’s description is perfect. When we do problem definition well in classic problem solving, we are demonstrating the kind of empathy, at the very beginning of our problem, that design thinking asks us to approach. When we ideate—and that’s very similar to the disaggregation, prioritization, and work-planning steps—we do precisely the same thing, and often we use contrasting teams, so that we do have divergent thinking. The best teams allow divergent thinking to bump them off whatever their initial biases in problem solving are. For me, design thinking gives us a constant reminder of creativity, empathy, and the tactile nature of problem solving, but it’s absolutely complementary, not alternative.

Simon London: I think, in a world of cross-functional teams, an interesting question is do people with design-thinking backgrounds really work well together with classical problem solvers? How do you make that chemistry happen?

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah, it is not easy when people have spent an enormous amount of time seeped in design thinking or user-centric design, whichever word you want to use. If the person who’s applying classic problem-solving methodology is very rigid and mechanical in the way they’re doing it, there could be an enormous amount of tension. If there’s not clarity in the role and not clarity in the process, I think having the two together can be, sometimes, problematic.

The second thing that happens often is that the artifacts the two methodologies try to gravitate toward can be different. Classic problem solving often gravitates toward a model; design thinking migrates toward a prototype. Rather than writing a big deck with all my supporting evidence, they’ll bring an example, a thing, and that feels different. Then you spend your time differently to achieve those two end products, so that’s another source of friction.

Now, I still think it can be an incredibly powerful thing to have the two—if there are the right people with the right mind-set, if there is a team that is explicit about the roles, if we’re clear about the kind of outcomes we are attempting to bring forward. There’s an enormous amount of collaborativeness and respect.

Simon London: But they have to respect each other’s methodology and be prepared to flex, maybe, a little bit, in how this process is going to work.

Hugo Sarrazin: Absolutely.

Simon London: The other area where, it strikes me, there could be a little bit of a different sort of friction is this whole concept of the day-one answer, which is what we were just talking about in classical problem solving. Now, you know that this is probably not going to be your final answer, but that’s how you begin to structure the problem. Whereas I would imagine your design thinkers—no, they’re going off to do their ethnographic research and get out into the field, potentially for a long time, before they come back with at least an initial hypothesis.

Want better strategies? Become a bulletproof problem solver

Hugo Sarrazin: That is a great callout, and that’s another difference. Designers typically will like to soak into the situation and avoid converging too quickly. There’s optionality and exploring different options. There’s a strong belief that keeps the solution space wide enough that you can come up with more radical ideas. If there’s a large design team or many designers on the team, and you come on Friday and say, “What’s our week-one answer?” they’re going to struggle. They’re not going to be comfortable, naturally, to give that answer. It doesn’t mean they don’t have an answer; it’s just not where they are in their thinking process.

Simon London: I think we are, sadly, out of time for today. But Charles and Hugo, thank you so much.

Charles Conn: It was a pleasure to be here, Simon.

Hugo Sarrazin: It was a pleasure. Thank you.

Simon London: And thanks, as always, to you, our listeners, for tuning into this episode of the McKinsey Podcast . If you want to learn more about problem solving, you can find the book, Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything , online or order it through your local bookstore. To learn more about McKinsey, you can of course find us at McKinsey.com.

Charles Conn is CEO of Oxford Sciences Innovation and an alumnus of McKinsey’s Sydney office. Hugo Sarrazin is a senior partner in the Silicon Valley office, where Simon London, a member of McKinsey Publishing, is also based.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Strategy to beat the odds

Five routes to more innovative problem solving

40 problem-solving techniques and processes

All teams and organizations encounter challenges. Approaching those challenges without a structured problem solving process can end up making things worse.

Proven problem solving techniques such as those outlined below can guide your group through a process of identifying problems and challenges , ideating on possible solutions , and then evaluating and implementing the most suitable .

In this post, you'll find problem-solving tools you can use to develop effective solutions. You'll also find some tips for facilitating the problem solving process and solving complex problems.

Design your next session with SessionLab

Join the 150,000+ facilitators using SessionLab.

Recommended Articles

A step-by-step guide to planning a workshop, 54 great online tools for workshops and meetings, how to create an unforgettable training session in 8 simple steps.

- 18 Free Facilitation Resources We Think You’ll Love

What is problem solving?

Problem solving is a process of finding and implementing a solution to a challenge or obstacle. In most contexts, this means going through a problem solving process that begins with identifying the issue, exploring its root causes, ideating and refining possible solutions before implementing and measuring the impact of that solution.

For simple or small problems, it can be tempting to skip straight to implementing what you believe is the right solution. The danger with this approach is that without exploring the true causes of the issue, it might just occur again or your chosen solution may cause other issues.

Particularly in the world of work, good problem solving means using data to back up each step of the process, bringing in new perspectives and effectively measuring the impact of your solution.

Effective problem solving can help ensure that your team or organization is well positioned to overcome challenges, be resilient to change and create innovation. In my experience, problem solving is a combination of skillset, mindset and process, and it’s especially vital for leaders to cultivate this skill.

What is the seven step problem solving process?

A problem solving process is a step-by-step framework from going from discovering a problem all the way through to implementing a solution.

With practice, this framework can become intuitive, and innovative companies tend to have a consistent and ongoing ability to discover and tackle challenges when they come up.

You might see everything from a four step problem solving process through to seven steps. While all these processes cover roughly the same ground, I’ve found a seven step problem solving process is helpful for making all key steps legible.

We’ll outline that process here and then follow with techniques you can use to explore and work on that step of the problem solving process with a group.

The seven-step problem solving process is:

1. Problem identification

The first stage of any problem solving process is to identify the problem(s) you need to solve. This often looks like using group discussions and activities to help a group surface and effectively articulate the challenges they’re facing and wish to resolve.

Be sure to align with your team on the exact definition and nature of the problem you’re solving. An effective process is one where everyone is pulling in the same direction – ensure clarity and alignment now to help avoid misunderstandings later.

2. Problem analysis and refinement

The process of problem analysis means ensuring that the problem you are seeking to solve is the right problem . Choosing the right problem to solve means you are on the right path to creating the right solution.

At this stage, you may look deeper at the problem you identified to try and discover the root cause at the level of people or process. You may also spend some time sourcing data, consulting relevant parties and creating and refining a problem statement.

Problem refinement means adjusting scope or focus of the problem you will be aiming to solve based on what comes up during your analysis. As you analyze data sources, you might discover that the root cause means you need to adjust your problem statement. Alternatively, you might find that your original problem statement is too big to be meaningful approached within your current project.

Remember that the goal of any problem refinement is to help set the stage for effective solution development and deployment. Set the right focus and get buy-in from your team here and you’ll be well positioned to move forward with confidence.

3. Solution generation

Once your group has nailed down the particulars of the problem you wish to solve, you want to encourage a free flow of ideas connecting to solving that problem. This can take the form of problem solving games that encourage creative thinking or techniquess designed to produce working prototypes of possible solutions.

The key to ensuring the success of this stage of the problem solving process is to encourage quick, creative thinking and create an open space where all ideas are considered. The best solutions can often come from unlikely places and by using problem solving techniques that celebrate invention, you might come up with solution gold.

4. Solution development

No solution is perfect right out of the gate. It’s important to discuss and develop the solutions your group has come up with over the course of following the previous problem solving steps in order to arrive at the best possible solution. Problem solving games used in this stage involve lots of critical thinking, measuring potential effort and impact, and looking at possible solutions analytically.

During this stage, you will often ask your team to iterate and improve upon your front-running solutions and develop them further. Remember that problem solving strategies always benefit from a multitude of voices and opinions, and not to let ego get involved when it comes to choosing which solutions to develop and take further.

Finding the best solution is the goal of all problem solving workshops and here is the place to ensure that your solution is well thought out, sufficiently robust and fit for purpose.

5. Decision making and planning

Nearly there! Once you’ve got a set of possible, you’ll need to make a decision on which to implement. This can be a consensus-based group decision or it might be for a leader or major stakeholder to decide. You’ll find a set of effective decision making methods below.

Once your group has reached consensus and selected a solution, there are some additional actions that also need to be decided upon. You’ll want to work on allocating ownership of the project, figure out who will do what, how the success of the solution will be measured and decide the next course of action.

Set clear accountabilities, actions, timeframes, and follow-ups for your chosen solution. Make these decisions and set clear next-steps in the problem solving workshop so that everyone is aligned and you can move forward effectively as a group.

Ensuring that you plan for the roll-out of a solution is one of the most important problem solving steps. Without adequate planning or oversight, it can prove impossible to measure success or iterate further if the problem was not solved.

6. Solution implementation

This is what we were waiting for! All problem solving processes have the end goal of implementing an effective and impactful solution that your group has confidence in.

Project management and communication skills are key here – your solution may need to adjust when out in the wild or you might discover new challenges along the way. For some solutions, you might also implement a test with a small group and monitor results before rolling it out to an entire company.

You should have a clear owner for your solution who will oversee the plans you made together and help ensure they’re put into place. This person will often coordinate the implementation team and set-up processes to measure the efficacy of your solution too.

7. Solution evaluation

So you and your team developed a great solution to a problem and have a gut feeling it’s been solved. Work done, right? Wrong. All problem solving strategies benefit from evaluation, consideration, and feedback.

You might find that the solution does not work for everyone, might create new problems, or is potentially so successful that you will want to roll it out to larger teams or as part of other initiatives.

None of that is possible without taking the time to evaluate the success of the solution you developed in your problem solving model and adjust if necessary.

Remember that the problem solving process is often iterative and it can be common to not solve complex issues on the first try. Even when this is the case, you and your team will have generated learning that will be important for future problem solving workshops or in other parts of the organization.

It’s also worth underlining how important record keeping is throughout the problem solving process. If a solution didn’t work, you need to have the data and records to see why that was the case. If you go back to the drawing board, notes from the previous workshop can help save time.

What does an effective problem solving process look like?

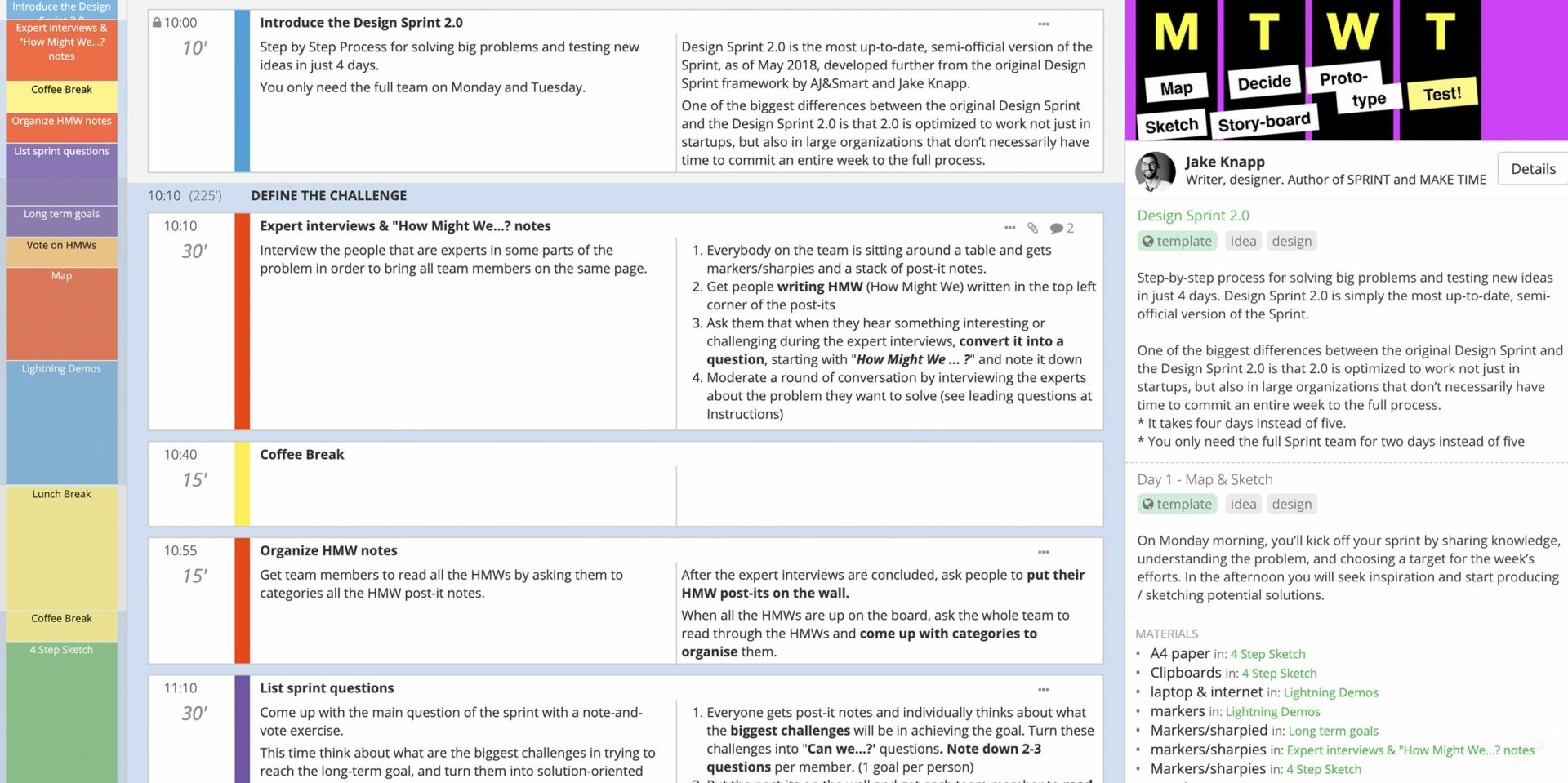

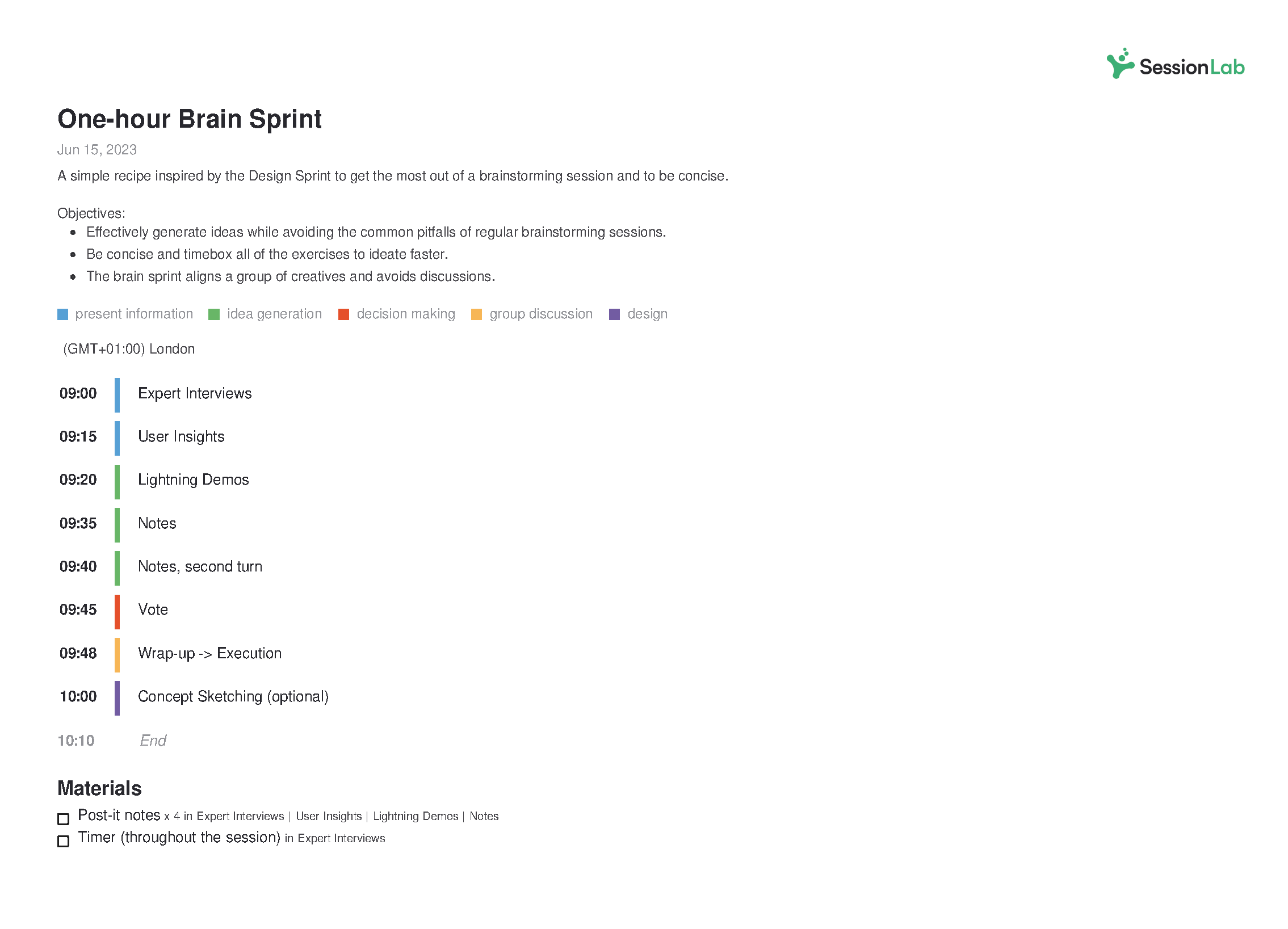

Every effective problem solving process begins with an agenda . In our experience, a well-structured problem solving workshop is one of the best methods for successfully guiding a group from exploring a problem to implementing a solution.

The format of a workshop ensures that you can get buy-in from your group, encourage free-thinking and solution exploration before making a decision on what to implement following the session.

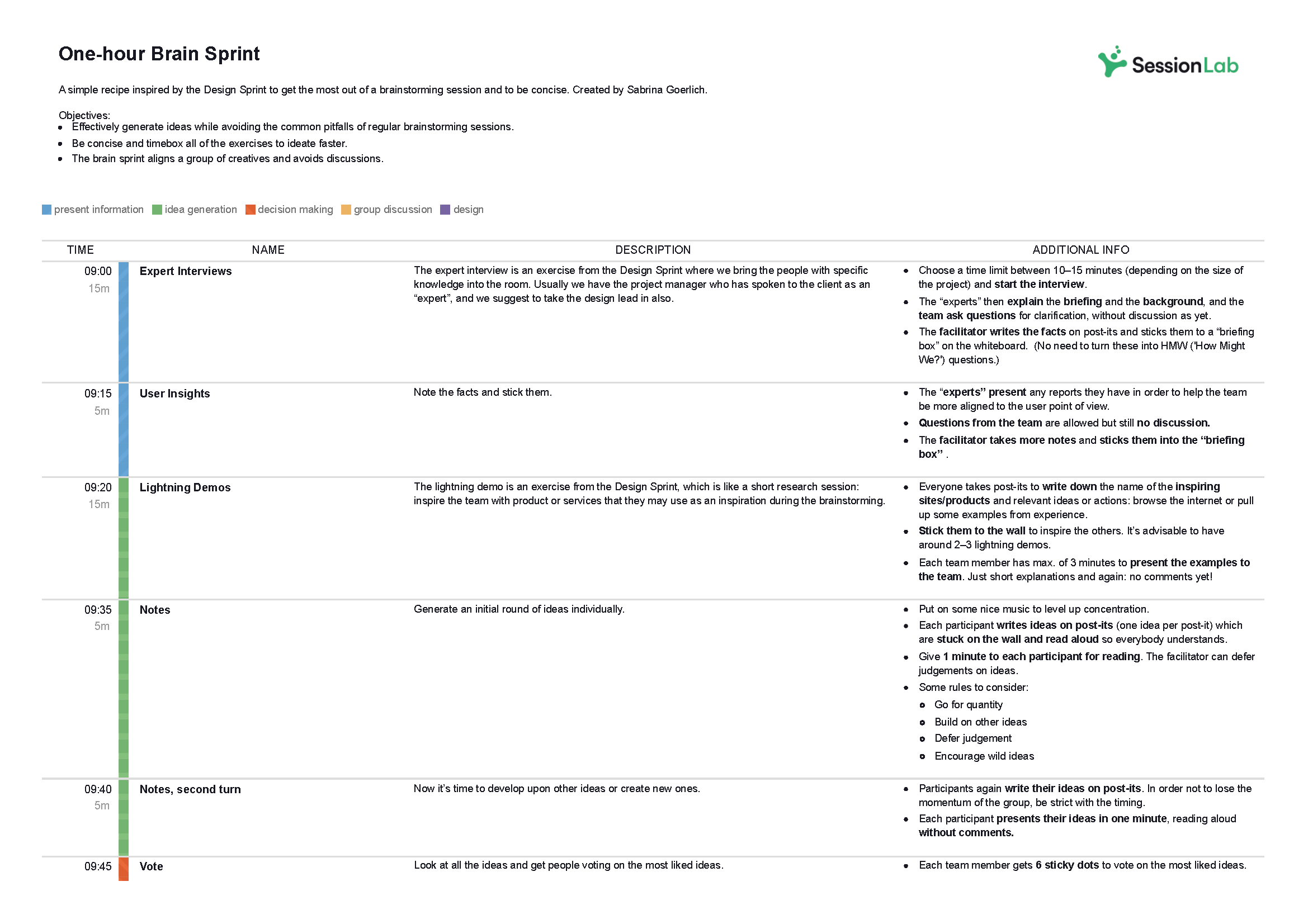

This Design Sprint 2.0 template is an effective problem solving process from top agency AJ&Smart. It’s a great format for the entire problem solving process, with four-days of workshops designed to surface issues, explore solutions and even test a solution.

Check it for an example of how you might structure and run a problem solving process and feel free to copy and adjust it your needs!

For a shorter process you can run in a single afternoon, this remote problem solving agenda will guide you effectively in just a couple of hours.

Whatever the length of your workshop, by using SessionLab, it’s easy to go from an idea to a complete agenda . Start by dragging and dropping your core problem solving activities into place . Add timings, breaks and necessary materials before sharing your agenda with your colleagues.

The resulting agenda will be your guide to an effective and productive problem solving session that will also help you stay organized on the day!

Complete problem-solving methods

In this section, we’ll look at in-depth problem-solving methods that provide a complete end-to-end process for developing effective solutions. These will help guide your team from the discovery and definition of a problem through to delivering the right solution.

If you’re looking for an all-encompassing method or problem-solving model, these processes are a great place to start. They’ll ask your team to challenge preconceived ideas and adopt a mindset for solving problems more effectively.

Six Thinking Hats

Individual approaches to solving a problem can be very different based on what team or role an individual holds. It can be easy for existing biases or perspectives to find their way into the mix, or for internal politics to direct a conversation.

Six Thinking Hats is a classic method for identifying the problems that need to be solved and enables your team to consider them from different angles, whether that is by focusing on facts and data, creative solutions, or by considering why a particular solution might not work.

Like all problem-solving frameworks, Six Thinking Hats is effective at helping teams remove roadblocks from a conversation or discussion and come to terms with all the aspects necessary to solve complex problems.

The Six Thinking Hats #creative thinking #meeting facilitation #problem solving #issue resolution #idea generation #conflict resolution The Six Thinking Hats are used by individuals and groups to separate out conflicting styles of thinking. They enable and encourage a group of people to think constructively together in exploring and implementing change, rather than using argument to fight over who is right and who is wrong.

Lightning Decision Jam

Featured courtesy of Jonathan Courtney of AJ&Smart Berlin, Lightning Decision Jam is one of those strategies that should be in every facilitation toolbox. Exploring problems and finding solutions is often creative in nature, though as with any creative process, there is the potential to lose focus and get lost.

Unstructured discussions might get you there in the end, but it’s much more effective to use a method that creates a clear process and team focus.

In Lightning Decision Jam, participants are invited to begin by writing challenges, concerns, or mistakes on post-its without discussing them before then being invited by the moderator to present them to the group.

From there, the team vote on which problems to solve and are guided through steps that will allow them to reframe those problems, create solutions and then decide what to execute on.

By deciding the problems that need to be solved as a team before moving on, this group process is great for ensuring the whole team is aligned and can take ownership over the next stages.

Lightning Decision Jam (LDJ) #action #decision making #problem solving #issue analysis #innovation #design #remote-friendly It doesn’t matter where you work and what your job role is, if you work with other people together as a team, you will always encounter the same challenges: Unclear goals and miscommunication that cause busy work and overtime Unstructured meetings that leave attendants tired, confused and without clear outcomes. Frustration builds up because internal challenges to productivity are not addressed Sudden changes in priorities lead to a loss of focus and momentum Muddled compromise takes the place of clear decision- making, leaving everybody to come up with their own interpretation. In short, a lack of structure leads to a waste of time and effort, projects that drag on for too long and frustrated, burnt out teams. AJ&Smart has worked with some of the most innovative, productive companies in the world. What sets their teams apart from others is not better tools, bigger talent or more beautiful offices. The secret sauce to becoming a more productive, more creative and happier team is simple: Replace all open discussion or brainstorming with a structured process that leads to more ideas, clearer decisions and better outcomes. When a good process provides guardrails and a clear path to follow, it becomes easier to come up with ideas, make decisions and solve problems. This is why AJ&Smart created Lightning Decision Jam (LDJ). It’s a simple and short, but powerful group exercise that can be run either in-person, in the same room, or remotely with distributed teams.

Problem Definition Process

While problems can be complex, the problem-solving methods you use to identify and solve those problems can often be simple in design.

By taking the time to truly identify and define a problem before asking the group to reframe the challenge as an opportunity, this method is a great way to enable change.

Begin by identifying a focus question and exploring the ways in which it manifests before splitting into five teams who will each consider the problem using a different method: escape, reversal, exaggeration, distortion or wishful. Teams develop a problem objective and create ideas in line with their method before then feeding them back to the group.

This method is great for enabling in-depth discussions while also creating space for finding creative solutions too!

Problem Definition #problem solving #idea generation #creativity #online #remote-friendly A problem solving technique to define a problem, challenge or opportunity and to generate ideas.

The 5 Whys

Sometimes, a group needs to go further with their strategies and analyze the root cause at the heart of organizational issues. An RCA or root cause analysis is the process of identifying what is at the heart of business problems or recurring challenges.

The 5 Whys is a simple and effective method of helping a group go find the root cause of any problem or challenge and conduct analysis that will deliver results.

By beginning with the creation of a problem statement and going through five stages to refine it, The 5 Whys provides everything you need to truly discover the cause of an issue.

The 5 Whys #hyperisland #innovation This simple and powerful method is useful for getting to the core of a problem or challenge. As the title suggests, the group defines a problems, then asks the question “why” five times, often using the resulting explanation as a starting point for creative problem solving.

World Cafe is a simple but powerful facilitation technique to help bigger groups to focus their energy and attention on solving complex problems.

World Cafe enables this approach by creating a relaxed atmosphere where participants are able to self-organize and explore topics relevant and important to them which are themed around a central problem-solving purpose. Create the right atmosphere by modeling your space after a cafe and after guiding the group through the method, let them take the lead!

Making problem-solving a part of your organization’s culture in the long term can be a difficult undertaking. More approachable formats like World Cafe can be especially effective in bringing people unfamiliar with workshops into the fold.

World Cafe #hyperisland #innovation #issue analysis World Café is a simple yet powerful method, originated by Juanita Brown, for enabling meaningful conversations driven completely by participants and the topics that are relevant and important to them. Facilitators create a cafe-style space and provide simple guidelines. Participants then self-organize and explore a set of relevant topics or questions for conversation.

Discovery & Action Dialogue (DAD)

One of the best approaches is to create a safe space for a group to share and discover practices and behaviors that can help them find their own solutions.

With DAD, you can help a group choose which problems they wish to solve and which approaches they will take to do so. It’s great at helping remove resistance to change and can help get buy-in at every level too!

This process of enabling frontline ownership is great in ensuring follow-through and is one of the methods you will want in your toolbox as a facilitator.

Discovery & Action Dialogue (DAD) #idea generation #liberating structures #action #issue analysis #remote-friendly DADs make it easy for a group or community to discover practices and behaviors that enable some individuals (without access to special resources and facing the same constraints) to find better solutions than their peers to common problems. These are called positive deviant (PD) behaviors and practices. DADs make it possible for people in the group, unit, or community to discover by themselves these PD practices. DADs also create favorable conditions for stimulating participants’ creativity in spaces where they can feel safe to invent new and more effective practices. Resistance to change evaporates as participants are unleashed to choose freely which practices they will adopt or try and which problems they will tackle. DADs make it possible to achieve frontline ownership of solutions.

Design Sprint 2.0

Want to see how a team can solve big problems and move forward with prototyping and testing solutions in a few days? The Design Sprint 2.0 template from Jake Knapp, author of Sprint, is a complete agenda for a with proven results.

Developing the right agenda can involve difficult but necessary planning. Ensuring all the correct steps are followed can also be stressful or time-consuming depending on your level of experience.

Use this complete 4-day workshop template if you are finding there is no obvious solution to your challenge and want to focus your team around a specific problem that might require a shortcut to launching a minimum viable product or waiting for the organization-wide implementation of a solution.

Open space technology

Open space technology- developed by Harrison Owen – creates a space where large groups are invited to take ownership of their problem solving and lead individual sessions. Open space technology is a great format when you have a great deal of expertise and insight in the room and want to allow for different takes and approaches on a particular theme or problem you need to be solved.

Start by bringing your participants together to align around a central theme and focus their efforts. Explain the ground rules to help guide the problem-solving process and then invite members to identify any issue connecting to the central theme that they are interested in and are prepared to take responsibility for.

Once participants have decided on their approach to the core theme, they write their issue on a piece of paper, announce it to the group, pick a session time and place, and post the paper on the wall. As the wall fills up with sessions, the group is then invited to join the sessions that interest them the most and which they can contribute to, then you’re ready to begin!

Everyone joins the problem-solving group they’ve signed up to, record the discussion and if appropriate, findings can then be shared with the rest of the group afterward.

Open Space Technology #action plan #idea generation #problem solving #issue analysis #large group #online #remote-friendly Open Space is a methodology for large groups to create their agenda discerning important topics for discussion, suitable for conferences, community gatherings and whole system facilitation

Techniques to identify and analyze problems

Using a problem-solving method to help a team identify and analyze a problem can be a quick and effective addition to any workshop or meeting.

While further actions are always necessary, you can generate momentum and alignment easily, and these activities are a great place to get started.

We’ve put together this list of techniques to help you and your team with problem identification, analysis, and discussion that sets the foundation for developing effective solutions.

Let’s take a look!

Fishbone Analysis

Organizational or team challenges are rarely simple, and it’s important to remember that one problem can be an indication of something that goes deeper and may require further consideration to be solved.

Fishbone Analysis helps groups to dig deeper and understand the origins of a problem. It’s a great example of a root cause analysis method that is simple for everyone on a team to get their head around.

Participants in this activity are asked to annotate a diagram of a fish, first adding the problem or issue to be worked on at the head of a fish before then brainstorming the root causes of the problem and adding them as bones on the fish.

Using abstractions such as a diagram of a fish can really help a team break out of their regular thinking and develop a creative approach.

Fishbone Analysis #problem solving ##root cause analysis #decision making #online facilitation A process to help identify and understand the origins of problems, issues or observations.

Problem Tree

Encouraging visual thinking can be an essential part of many strategies. By simply reframing and clarifying problems, a group can move towards developing a problem solving model that works for them.

In Problem Tree, groups are asked to first brainstorm a list of problems – these can be design problems, team problems or larger business problems – and then organize them into a hierarchy. The hierarchy could be from most important to least important or abstract to practical, though the key thing with problem solving games that involve this aspect is that your group has some way of managing and sorting all the issues that are raised.

Once you have a list of problems that need to be solved and have organized them accordingly, you’re then well-positioned for the next problem solving steps.

Problem tree #define intentions #create #design #issue analysis A problem tree is a tool to clarify the hierarchy of problems addressed by the team within a design project; it represents high level problems or related sublevel problems.

SWOT Analysis

Chances are you’ve heard of the SWOT Analysis before. This problem-solving method focuses on identifying strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats is a tried and tested method for both individuals and teams.

Start by creating a desired end state or outcome and bare this in mind – any process solving model is made more effective by knowing what you are moving towards. Create a quadrant made up of the four categories of a SWOT analysis and ask participants to generate ideas based on each of those quadrants.

Once you have those ideas assembled in their quadrants, cluster them together based on their affinity with other ideas. These clusters are then used to facilitate group conversations and move things forward.

SWOT analysis #gamestorming #problem solving #action #meeting facilitation The SWOT Analysis is a long-standing technique of looking at what we have, with respect to the desired end state, as well as what we could improve on. It gives us an opportunity to gauge approaching opportunities and dangers, and assess the seriousness of the conditions that affect our future. When we understand those conditions, we can influence what comes next.

Agreement-Certainty Matrix

Not every problem-solving approach is right for every challenge, and deciding on the right method for the challenge at hand is a key part of being an effective team.

The Agreement Certainty matrix helps teams align on the nature of the challenges facing them. By sorting problems from simple to chaotic, your team can understand what methods are suitable for each problem and what they can do to ensure effective results.

If you are already using Liberating Structures techniques as part of your problem-solving strategy, the Agreement-Certainty Matrix can be an invaluable addition to your process. We’ve found it particularly if you are having issues with recurring problems in your organization and want to go deeper in understanding the root cause.

Agreement-Certainty Matrix #issue analysis #liberating structures #problem solving You can help individuals or groups avoid the frequent mistake of trying to solve a problem with methods that are not adapted to the nature of their challenge. The combination of two questions makes it possible to easily sort challenges into four categories: simple, complicated, complex , and chaotic . A problem is simple when it can be solved reliably with practices that are easy to duplicate. It is complicated when experts are required to devise a sophisticated solution that will yield the desired results predictably. A problem is complex when there are several valid ways to proceed but outcomes are not predictable in detail. Chaotic is when the context is too turbulent to identify a path forward. A loose analogy may be used to describe these differences: simple is like following a recipe, complicated like sending a rocket to the moon, complex like raising a child, and chaotic is like the game “Pin the Tail on the Donkey.” The Liberating Structures Matching Matrix in Chapter 5 can be used as the first step to clarify the nature of a challenge and avoid the mismatches between problems and solutions that are frequently at the root of chronic, recurring problems.

Organizing and charting a team’s progress can be important in ensuring its success. SQUID (Sequential Question and Insight Diagram) is a great model that allows a team to effectively switch between giving questions and answers and develop the skills they need to stay on track throughout the process.

Begin with two different colored sticky notes – one for questions and one for answers – and with your central topic (the head of the squid) on the board. Ask the group to first come up with a series of questions connected to their best guess of how to approach the topic. Ask the group to come up with answers to those questions, fix them to the board and connect them with a line. After some discussion, go back to question mode by responding to the generated answers or other points on the board.

It’s rewarding to see a diagram grow throughout the exercise, and a completed SQUID can provide a visual resource for future effort and as an example for other teams.

SQUID #gamestorming #project planning #issue analysis #problem solving When exploring an information space, it’s important for a group to know where they are at any given time. By using SQUID, a group charts out the territory as they go and can navigate accordingly. SQUID stands for Sequential Question and Insight Diagram.

To continue with our nautical theme, Speed Boat is a short and sweet activity that can help a team quickly identify what employees, clients or service users might have a problem with and analyze what might be standing in the way of achieving a solution.

Methods that allow for a group to make observations, have insights and obtain those eureka moments quickly are invaluable when trying to solve complex problems.

In Speed Boat, the approach is to first consider what anchors and challenges might be holding an organization (or boat) back. Bonus points if you are able to identify any sharks in the water and develop ideas that can also deal with competitors!

Speed Boat #gamestorming #problem solving #action Speedboat is a short and sweet way to identify what your employees or clients don’t like about your product/service or what’s standing in the way of a desired goal.

The Journalistic Six

Some of the most effective ways of solving problems is by encouraging teams to be more inclusive and diverse in their thinking.

Based on the six key questions journalism students are taught to answer in articles and news stories, The Journalistic Six helps create teams to see the whole picture. By using who, what, when, where, why, and how to facilitate the conversation and encourage creative thinking, your team can make sure that the problem identification and problem analysis stages of the are covered exhaustively and thoughtfully. Reporter’s notebook and dictaphone optional.

The Journalistic Six – Who What When Where Why How #idea generation #issue analysis #problem solving #online #creative thinking #remote-friendly A questioning method for generating, explaining, investigating ideas.

Individual and group perspectives are incredibly important, but what happens if people are set in their minds and need a change of perspective in order to approach a problem more effectively?

Flip It is a method we love because it is both simple to understand and run, and allows groups to understand how their perspectives and biases are formed.

Participants in Flip It are first invited to consider concerns, issues, or problems from a perspective of fear and write them on a flip chart. Then, the group is asked to consider those same issues from a perspective of hope and flip their understanding.

No problem and solution is free from existing bias and by changing perspectives with Flip It, you can then develop a problem solving model quickly and effectively.

Flip It! #gamestorming #problem solving #action Often, a change in a problem or situation comes simply from a change in our perspectives. Flip It! is a quick game designed to show players that perspectives are made, not born.

LEGO Challenge

Now for an activity that is a little out of the (toy) box. LEGO Serious Play is a facilitation methodology that can be used to improve creative thinking and problem-solving skills.

The LEGO Challenge includes giving each member of the team an assignment that is hidden from the rest of the group while they create a structure without speaking.

What the LEGO challenge brings to the table is a fun working example of working with stakeholders who might not be on the same page to solve problems. Also, it’s LEGO! Who doesn’t love LEGO!

LEGO Challenge #hyperisland #team A team-building activity in which groups must work together to build a structure out of LEGO, but each individual has a secret “assignment” which makes the collaborative process more challenging. It emphasizes group communication, leadership dynamics, conflict, cooperation, patience and problem solving strategy.

What, So What, Now What?

If not carefully managed, the problem identification and problem analysis stages of the problem-solving process can actually create more problems and misunderstandings.

The What, So What, Now What? problem-solving activity is designed to help collect insights and move forward while also eliminating the possibility of disagreement when it comes to identifying, clarifying, and analyzing organizational or work problems.

Facilitation is all about bringing groups together so that might work on a shared goal and the best problem-solving strategies ensure that teams are aligned in purpose, if not initially in opinion or insight.

Throughout the three steps of this game, you give everyone on a team to reflect on a problem by asking what happened, why it is important, and what actions should then be taken.

This can be a great activity for bringing our individual perceptions about a problem or challenge and contextualizing it in a larger group setting. This is one of the most important problem-solving skills you can bring to your organization.

W³ – What, So What, Now What? #issue analysis #innovation #liberating structures You can help groups reflect on a shared experience in a way that builds understanding and spurs coordinated action while avoiding unproductive conflict. It is possible for every voice to be heard while simultaneously sifting for insights and shaping new direction. Progressing in stages makes this practical—from collecting facts about What Happened to making sense of these facts with So What and finally to what actions logically follow with Now What . The shared progression eliminates most of the misunderstandings that otherwise fuel disagreements about what to do. Voila!

Journalists

Problem analysis can be one of the most important and decisive stages of all problem-solving tools. Sometimes, a team can become bogged down in the details and are unable to move forward.

Journalists is an activity that can avoid a group from getting stuck in the problem identification or problem analysis stages of the process.

In Journalists, the group is invited to draft the front page of a fictional newspaper and figure out what stories deserve to be on the cover and what headlines those stories will have. By reframing how your problems and challenges are approached, you can help a team move productively through the process and be better prepared for the steps to follow.

Journalists #vision #big picture #issue analysis #remote-friendly This is an exercise to use when the group gets stuck in details and struggles to see the big picture. Also good for defining a vision.

Problem-solving techniques for brainstorming solutions

Now you have the context and background of the problem you are trying to solving, now comes the time to start ideating and thinking about how you’ll solve the issue.

Here, you’ll want to encourage creative, free thinking and speed. Get as many ideas out as possible and explore different perspectives so you have the raw material for the next step.

Looking at a problem from a new angle can be one of the most effective ways of creating an effective solution. TRIZ is a problem-solving tool that asks the group to consider what they must not do in order to solve a challenge.

By reversing the discussion, new topics and taboo subjects often emerge, allowing the group to think more deeply and create ideas that confront the status quo in a safe and meaningful way. If you’re working on a problem that you’ve tried to solve before, TRIZ is a great problem-solving method to help your team get unblocked.

Making Space with TRIZ #issue analysis #liberating structures #issue resolution You can clear space for innovation by helping a group let go of what it knows (but rarely admits) limits its success and by inviting creative destruction. TRIZ makes it possible to challenge sacred cows safely and encourages heretical thinking. The question “What must we stop doing to make progress on our deepest purpose?” induces seriously fun yet very courageous conversations. Since laughter often erupts, issues that are otherwise taboo get a chance to be aired and confronted. With creative destruction come opportunities for renewal as local action and innovation rush in to fill the vacuum. Whoosh!

Mindspin

Brainstorming is part of the bread and butter of the problem-solving process and all problem-solving strategies benefit from getting ideas out and challenging a team to generate solutions quickly.

With Mindspin, participants are encouraged not only to generate ideas but to do so under time constraints and by slamming down cards and passing them on. By doing multiple rounds, your team can begin with a free generation of possible solutions before moving on to developing those solutions and encouraging further ideation.

This is one of our favorite problem-solving activities and can be great for keeping the energy up throughout the workshop. Remember the importance of helping people become engaged in the process – energizing problem-solving techniques like Mindspin can help ensure your team stays engaged and happy, even when the problems they’re coming together to solve are complex.

MindSpin #teampedia #idea generation #problem solving #action A fast and loud method to enhance brainstorming within a team. Since this activity has more than round ideas that are repetitive can be ruled out leaving more creative and innovative answers to the challenge.

The Creativity Dice

One of the most useful problem solving skills you can teach your team is of approaching challenges with creativity, flexibility, and openness. Games like The Creativity Dice allow teams to overcome the potential hurdle of too much linear thinking and approach the process with a sense of fun and speed.

In The Creativity Dice, participants are organized around a topic and roll a dice to determine what they will work on for a period of 3 minutes at a time. They might roll a 3 and work on investigating factual information on the chosen topic. They might roll a 1 and work on identifying the specific goals, standards, or criteria for the session.