- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Try unlimited access Only $1 for 4 weeks

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital, weekend print + standard digital, weekend print + premium digital.

Today's FT newspaper for easy reading on any device. This does not include ft.com or FT App access.

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- Videos & Podcasts

- FT App on Android & iOS

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Premium newsletters

- Weekday Print Edition

- FT Weekend Print delivery

- Everything in Premium Digital

Essential digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Everything in Print

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 11 December 2023

The art of rhetoric: persuasive strategies in Biden’s inauguration speech: a critical discourse analysis

- Nisreen N. Al-Khawaldeh 1 ,

- Luqman M. Rababah ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3871-3853 2 ,

- Ali F. Khawaldeh 1 &

- Alaeddin A. Banikalef 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 936 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

3759 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Language and linguistics

This research investigated the main linguistic strategies used in President Biden’s inauguration speech presented in 2021. Data were analyzed in light of Fairclough’s CDA framework: macro-structure (thematic)—intertextually; microstructure in syntax analysis (cohesion); stylistic (lexicon choice to display the speaker’s emphasis); and rhetoric in terms of persuasive function. The thematic analysis of the data revealed that Biden used certain persuasive strategies including creativity, metaphor, contrast, indirectness, reference, and intertextuality, for addressing critical issues. Creative expressions were drawn highlighting and magnifying significant real-life issues. Certain concepts and values (i.e., unity, democracy, and racial justice) were also accentuated as significant elements of America’s status and Biden’s ideology. Intertextuality was employed by resorting to an extract from one of the American presidents in order to convince the Americans and the international community of his ideas, vision, and policy. It appeared that indirect expressions were also used for discussing politically sensitive issues to acquire a political and interactional advantage over his political opponents. His referencing style showed his interest in others and their unity. Significant ideologies encompassing unity, equality, and freedom for US citizens were stated implicitly and explicitly. The study concludes that the effective use of linguistic and rhetorical devices is important to construct meanings in the world, be persuasive, and convey the intended vision and underlying ideologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Worldwide divergence of values

Anger is eliminated with the disposal of a paper written because of provocation

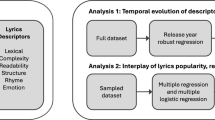

Song lyrics have become simpler and more repetitive over the last five decades

Introduction.

The significance of language in political and academic realms has gained prominence in recent times (Iqbal et al., 2020 ; Kozlovskaya, et al., 2020 ; Moody & Eslami, 2020 ). Language serves as a potent instrument in politics, embodying a crucial role in the struggle for power to uphold and enact specific beliefs and interests. Undeniably, language encompasses elements that unveil diverse intended meanings conveyed through political speeches, influencing, planning, accompanying, and managing every political endeavor. Effectiveness in political speeches relies on meeting criteria such as credibility, logic, and emotional appeal (Nikitina, 2011 ). Credibility is attained through possessing a particular amount of authority and understanding of the selected issue. Logical coherence is evident when the speech is clear and makes sense to the audience. In addition, establishing an emotional connection with the audience is essential to capture and maintain their attention.

Political speech, a renowned genre of discourse, reveals a lot about how power is distributed, exerted, and perceived in a country. Speech is a powerful tool for shaping the political thinking and political “mind” of a nation, allowing the actors and recipients of political activity to acquire a certain political vision (Fairclough, 1989 ). Political scientists are primarily interested in the historical implications of political decisions and acts, and they are interested in the political realities that are formed in and via discourse (Schmidt, 2008 ; Pierson & Skocpol, 2002 ). Linguists, on the other hand, have long been fascinated by language patterns employed to deliver politically relevant messages to certain locations in order to accomplish a specific goal.

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) is a crucial approach for analyzing language in depth so as to reveal certain tendencies within political discourse (Janks, 1997 ). CDA is not the same as other types of discourse analysis. That is why it is said to be “critical.” According to Cameron ( 2001 ), “critical refers to a way of understanding the social world drawn from critical theory” (p. 121). Fairclough ( 1995 ) also says, “Critical implies showing connections and causes which are hidden; it also implies intervention, for example, providing resources for those who may be disadvantaged through change” (p. 9). In short, it can be applied to both talk and text delivered by leaders or politicians who normally have a lot of authority to reveal their hidden agenda (Cameron, 2001 ) and decipher the meaning of the crucial concealed ideas (Fairclough, 1989 ). Therefore, it is a useful technique for analyzing texts like speeches connected with power, conflict, and politics, such as Martin Luther King’s speech (Alfayes, 2009 ). Fairclough concludes that CDA can elucidate the hidden meaning of “I Have a Dream,” the speech that has a strong and profound significance and whose messages concerning black Americans’ poverty and struggle have inspired many people all around the world. The ideological components are enshrined in political speeches since “ideology invests language in various ways at various levels and that ideology is both properties of structures and events” (Fairclough, 1995 , p. 71). Thus, meanings are produced through attainable interpretations of the target speech.

CDA has obtained wide prominence in analyzing language usage beyond word and sentence levels (Almahasees & Mahmoud, 2022 ). CDA, also known as critical language study (Fairclough, 1989 ) or critical linguistics (Fairclough, 1995 ; Chouliaraki & Fairclough, 1999 ), considers language to be a critical component of social and cultural processes (Fairclough, 1992 ; Fairclough, 1995 ; Chouliaraki & Fairclough, 1999 ). The goal of this strategy, according to Fairclough ( 1989 ), is to “contribute to the broad raising of consciousness of exploitative social connections by focusing on language” (p. 4). He also claims that CDA is concerned with studying linkages within language between dominance, discrimination, power, and control (Fairclough, 1992 ; Fairclough, 1995 ) and that the goal of CDA is to link between discourse practice and social practice obvious (Fairclough, 1995 ). The CDA is a type of critical thinking which means, according to Beyer ( 1995 ), “developing reasoned conclusions.” Thus, it might be viewed as a critical perspective and interpretation that focuses on social issues, notably the role of discourse in the production and reproduction of power abuse or dominance (Wodak & Meyer, 2009 ). Furthermore, the ‘Sapir–Whorf hypothesis’ indicates that the goal of critical discourse interpretation is to retrieve the social meanings conveyed in the speech by analyzing language structures considering their interactive and larger social contexts (Fairclough, 1992 ; Kriyantono, 2019 ; Lauwren, 2020 ).

Political communication is generally classified as a persuasive speech since it aims to influence or convince people that they have made the right choice (Nusartlert, 2017 ). Persuasive discourse is a very powerful tool for getting what is needed or intended. In such a type of discourse, people use communicative strategies to convince or urge specific thoughts, actions, and attitudes. Scheidel defines persuasion as “the activity in which the speaker and the listener are conjoined and in which the speaker consciously attempts to influence the behavior of the listener by transmitting audible, visible and symbolic” ( 1967 , p. 1). Thus, persuasive language is used to fulfill various reasons, among which is convincing people to accept a specific standpoint or idea.

Political speeches are considered eloquent pieces of communication oriented toward persuading the target audience (Haider, 2016 ). Politicians often use many persuasive techniques to express their agendas in refined language in order to convince people of their views on certain issues, gain support from the public, and ultimately achieve the envisioned goals (Fairclough, 1992 ). Leaders who control uncertainty, build allies, and generate supportive resources can easily gain enough leverage to lead. This means that their usage of language aims to put their intended political, economic, and social acts into practice. The inaugural speech is a very political discourse to analyze because it marks the inception of the new presidency, mainly focusing on infusing unity among people. In light of the scarcity of research on this significant speech, this study aims to investigate the main linguistic persuasive strategies used in President Biden’s inauguration speech presented in 2021.

Literature review

Political speeches are a significant genre within the realm of political discourse in which politicians use language intentionally to steer people’s mindsets and emotions in order to achieve a specific outcome. Since politics is mainly based on a constant struggle for power among concerned individuals or parties, persuasive techniques are crucial elements politicians use to manipulate others or make them accept their entrenched ideas and plans. Persuasion involves using rhetoric to convince the target audience to embrace certain ideologies, adopt specific attitudes, and control their behavior toward a particular issue (Van Dijk, 2015 ). The inaugural speeches are quite diplomatic and rhetorical, as they constitute a golden chance for the leaders to assert their leadership style. Thus, they are open to different types of interpretations and form a copious source of data for politicians and linguists. The linguistic choices politicians make are rational because of the underlying ideologies that determine the way their speeches should be structured. Considering this idea, it is vital to study the rhetoric of the American presidential inaugural speech since it was presented at a time full of critical political events and scenarios by a very influential political figure in the world, marking the inception of a new phase in the lives of Americans and the world. The significance of studying such a piece of discourse lies in the messages that the new president seeks to deliver to the American nation and the world at large.

Biden’s speeches have attracted researchers’ attention. For example, Renaldo & Arifin ( 2021 ) examined Biden’s ideology evident in his inaugural speech. The analysis of the data revealed three types of presuppositions manifested in his speech, i.e., lexical, existential, and factive, where lexical presupposition is the most frequent one. The underlying ideology was demonstrated in issues regarding immigrants, healthcare, racism, democracy, and climate change.

Prasetio and Prawesti ( 2021 ) analyzed the underlying meanings based on word counts considering three subcategories: hostility, use of auxiliaries, and noun-pronoun discourse analysis. The results revealed Biden’s hope of helping Americans by overcoming problems, developing many fields, and enhancing different aspects. It was evident that his underlying ideology was liberalism and his cherished values were democracy and unity.

Pramadya and Rahmanhadi ( 2021 ) studied the way Biden employed the rhetoric of political language in his inauguration speech in order to show his plans and political views. Each political message conveyed in his inauguration speech revealed his ideology and power. Sociocultural practices that supported the text were explored to view the inherent reality that gave rise to the discourse.

Amir ( 2021 ) investigated Biden’s persuasive strategies and the covert ideology manifested in his inaugural speech. Numerous components including “the rule of three,” the past references, the biblical examples, etc., were analyzed. The results emphasized the strength of America’s heroic past, which requires that Americans mainly focus on American values of tolerance, unity, and love.

Bani-Khaled and Azzam ( 2021 ) examined the linguistic devices used to convey the theme of unity in President Joe Biden’s Inauguration Speech. The qualitative analysis of this theme showed that the speaker used suitable linguistic features to clarify the concept of unity. It revealed that the tone of the speech appeared confident, reconciliatory, and optimistic. Both religion and history were resorted to as sources of rhetorical and persuasive devices.

The review of the literature shows a bi-directional relationship between language and sociocultural practices. Each one of them exerts an influence on the other. Therefore, CDA explores both the socially shaped and constitutive sides of language usage since language is viewed as “social identity, social relations, and systems of knowledge and belief” (Fairclough, 1993 , p. 134). It shows invisible connections and interventions (Fairclough, 1992 ). Consequently, it is significant to disclose such unobserved meanings and intentions to listeners who may not be aware of them.

Despite the plethora of critical discourse analysis research on political speeches, few studies were conducted on Biden’s inauguration speech. Thus, this study aims to enrich the existing research by complementing the analysis and highlighting some other significant aspects of Biden’s inauguration speech. Therefore, it is expected that this study will enrich critical discourse analysis research by focusing mainly on political speech. It can be a helpful source for teachers studying and teaching languages. They will learn how to properly analyze discourses by following a critical thinking approach to fully comprehend the relationship linking individual parts of discourses and creating meaning. Besides, the study casts light on distinctive features of societies manifested in political speech.

Methodology

The present study analyses President Biden’s inauguration speech (Biden, 2021 ). Data were analyzed in light of the CDA framework: macro-structure (thematic)—intertextually; microstructure in syntax analysis (cohesion); stylistic (lexicon choice to display the speaker’s emphasis); and rhetoric in terms of persuasive function. Fairclough’s discourse analysis approach was adopted to analyze the target speech in terms of text analysis, discursive practices, and social practices. The main token and the frequency of the recurring words were statistically analyzed, whereas the persuasive strategies proposed by Obeng ( 1997 ) were analyzed based on Fairclough’s ( 1992 ) CDA mentioned above.

Results and discussion

In the United States, presidents deliver inaugural speeches after taking the presidential oath of office. Presidents use this occasion to address the public and lay forth their vision and objectives. These speeches can also help to unify the United States, especially after difficult times or conflicts. Millions of people in the United States, as well as millions of people throughout the world, listen to the inaugural speeches to gain a glimpse of the new president’s vision for the world. This speech is particularly intriguing to analyze using the CDA framework in many aspects. Fairclough ( 1992 ) emphasizes that language must be regarded as an instrument of power as well as a tool of communication. Actually, there is a technique for utilizing language that seeks to encourage individuals who are engaged to do particular things.

The analysis of the ideological aspect of Biden’s inaugural speech endeavors to link this speech with certain social processes and to decode his invisible ideology. From the opening lines, it is apparent that Biden’s ideology is based on inclusiveness and a citizen-based position. At the beginning of his speech, he uses the first few minutes of his inaugural speech to thank and address his predecessors and audience as ‘my fellow Americans,’ lumping all sorts of nationalities and ethnicities together as one nation.

Biden then continues to mark a successful and smooth transition of power with an emphasis on a citizen-based attitude. He underlines that the victory belongs not only to him but to all Americans who have spoken up for a better life in the United States, saying “We celebrate the triumph not of a candidate, but of a cause. The cause of democracy. The people, the will of the people has been heard and the will of the people has been heeded.” With this victory, he promised to take his position seriously to unify America as a whole, regardless of its diversity by eliminating discrimination and reuniting the country’s divided territories in order to rebuild fresh faith among Americans. People of all races, ethnicities, sexual orientations, faiths, and origins should be treated equally. There is no difference between red and blue states except for the United States. Through this technique, he tries to accentuate that the whole American system depends on grassroots diplomacy, rather than an exclusive system of presidency. The beginning and the end of his speech successfully emphasize the importance of the oath that he took on himself to serve his nation without bias where he begins with “I have just taken a sacred oath each of those patriots took” and reminds the audience of the holiness of this oath at the end of his speech; as he says “ I close today where I began, with a sacred oath ”.

This section is divided into seven parts. Each of these parts analyses the speech in light of the selected persuasive strategies, which are creativity, indirectness, intertextuality, choice of lexis, coherence, modality, and reference. These strategies were selected among others due to their knock-on effect on explicating the core ideas of the speech.

Creativity is an essential part of any successful political speech. That is because it plays a significant role in structuring the facts the speaker wants to convey in a way that is accessible to the audience. It helps political figures persuade the public of their ideas, initiatives, and agendas. Indeed, Biden’s speech abounds with examples of creativity which in turn shapes the policies and expectations he adopts.

By using the expression “ violence sought to shake the Capitol’s very foundation ”. The speaker alluded with some subtlety and shrewdness to the riots made by a pro-Trump crowd that assaulted the US Capitol on Jan. 6 in an attempt to prevent the formal certification of the Electoral College results. Hundreds of fanatics walked onto the same platform where Biden had taken his oath of office, they offended the democracy and prestige of the place and the US reputation. He left unsaid that they were sent to the Capitol by the previous president, and described them in another part of his speech:

Here we stand, just days after a riotous mob thought they could use violence to silence the will of the people, to stop the work of our democracy, and to drive us from this sacred ground.

Biden won the popular vote by a combined (7) million votes and the Electoral College. The election results were frequently confirmed in courts as being free of fraud. Nevertheless, the rioters who attacked the Capitol claimed differently and never completely admitted these results.

The other thing that stood out was Biden’s emphasis on racism. He highlighted the Declaration of Independence’s goals, as he often does, and depicted them as being at odds with reality:

I know the forces that divide us are deep and they are real. But I also know they are not new. Our history has been a constant struggle between the American ideal that we are all created equal and the harsh, ugly reality that racism, nativism, fear, demonization have long torn us apart.

Of all, this isn’t the first time a president has spoken about racism at an inauguration. However, in the backdrop of the (Black Lives Matter) riots and the continued attack on voting rights, Biden’s adoption of that phrase as his own is both strategically and ethically significant. The pursuit of racial justice has previously been mentioned by Biden as a significant government aim. To lend substance to his rhetoric, society will have to take action on criminal justice reform and voting rights.

President Biden also argued that there has been great progress in women’s rights.

Here we stand, where 108 years ago at another inaugural, thousands of protesters tried to block brave women marching for the right to vote. Today we mark the swearing-in of the first woman in American history elected to national office—Vice President Kamala Harris.

In 1913, a huge number of women marched for the right to vote in a massive suffrage parade on the eve of President-elect Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, but the next day crowds of mostly men poured into the street for the following day’s inauguration, making it almost impossible for the marchers to get through. Many women heard ‘indecent epithets’ and ‘barnyard banter,’ and they were jeered, tripped, groped, and shoved. But now the big difference has been achieved. During his primary campaign, Biden promised to make history with his running mate selection, claiming he would exclusively consider women. He followed through on that commitment by choosing a lawmaker from one of the most ardent supporters of his campaign, black women, as well as the fastest-growing minority group in the country, Asian Americans.

On a related note, the president touched on the issue of racism, xenophobia, nativism, and other forms of intolerance in the United States “ And now, a rise in political extremism, white supremacy, domestic terrorism that we must confront and we will defeat .” He stressed that every human being has inherent dignity and deserves to be treated with fairness. That is why, on his first day in office, he signed an order establishing a whole-government approach to equity and racial justice. Biden’s administration talks of “restoring humanity” to the US immigration system and considering immigrants as valuable community members and employees. At the same time, Biden is signaling that the previous administration’s belligerent attitude toward partners is over, that the US’s image has plummeted to new lows, and that America can once again be trusted to uphold its commitments in a clear attempt to heal the rift in America’s foreign relations and rebuild alliances with the rest of the world.

So here is my message to those beyond our borders: America has been tested and we have come out stronger for it. We will repair our alliances and engage with the world once again.

Indirectness

Politicians avoid being obvious and speak indirectly while discussing politically sensitive issues in order to protect and advance their careers as well as acquire a political and interactional advantage over their political opponents. It’s also possible that the indirectness is driven by courtesy. Evasion, circumlocution, innuendoes, metaphors, and other forms of oblique communication can be used to convey this obliqueness. Indirectness is closely connected with politeness as it serves politicians’ agendas by spreading awful stories about their opponents (Van Dijk, 2011 ).

Many presidents have been more inclined to draw comparisons between their policies and those of their predecessors. Therefore, Biden was so adamant about avoiding focusing on the previous president that he didn’t criticize or blame the Trump administration’s shortcomings on the epidemic or anything else. In other words, he does not want to offend Republicans, Trump’s party. When Biden was talking about the attack on the US Capitol by the supporters of Trump, he didn’t mention that Trump had sent them. He talked about the lies of Trump and his followers without naming them, but the idea was clear.

There is truth and there are lies. Lies told for power and for profit” he declared. “Each of us has a duty and responsibility, as citizens, as Americans, and especially as leaders—leaders who have pledged to honor our Constitution and protect our nation—to defend the truth and to defeat the lies.

Of course, such lies were spread not merely by Trump and his horde, but also by the majority of Republicans in Congress, who relentlessly promoted the myth that Trump had won the election. One of the most striking aspects of Biden’s speech is this: while appealing for unity, he admitted that some of his opponents aren’t on the same page as him and that their influence has to be addressed. Biden didn’t use his speech to criticize those who believe his victory was skewed, but he appeared to acknowledge that his plan would be tough to implement without tackling the spread of lies. It was an interesting choice for a man who promotes compromise.

Biden’s speech is enriched with numerous conceptual metaphors and metonymies stemming from various domains. Metaphor is perceived as an effective pervasive technique used frequently in our daily communication (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980 ; Van Dijk, 2006 ). It helps the addressees understand and experience one thing in terms of another. It is closely related to cognition as it affects people’s reasoning and giving opinions and judgments (Thibodeau and Boroditsky, 2011 ). For example, Biden used the metaphor ‘Lower the temperature’ to lessen the tension and chaos caused in the previous presidential period. In another example, he utilized ‘ Politics need not be a raging fire ’ to portray politics as something dangerous and might destroy others.

Biden presents examples of metonymy when he portrays periods of troubles, setbacks, and difficult times as dark winter ‘We will need all our strength to persevere through this dark winter’ to emphasize the gloomy days Americans experience in times of crises and wars. The representation of the concept of ‘unity as the path forward’ implicitly alludes to Biden’s path for the previously created divided America, emphasizing the significance of following and securing the necessary solution, which is unity as the path for moving forward. The depiction of crises facing Americans such as ‘ Anger, resentment, hatred. Extremism, lawlessness, violence, Disease, joblessness, hopelessness’ as foes, make people feel the urgent need to unite in order to combat these foes. The expression of ‘ ugly reality ’ reflects an atrocious world full of problems such as racism, nativism, fear, and demonetization . Integrating such conceptual metaphors and metonymy is conventional and deeply rooted and can lead to promoting ideologies by presenting critical political issues in a specific way (Charteris-Black, 2018 ). They make the speech more persuasive as they facilitate people’s understanding of abstract and intricate ideas through using concrete experienceable objects (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980 ). In other words, they perfectly and politely portray serious issues confronting Americans as well as the course of action required to overcome them. Democracy is depicted as both a precious and fragile object. This metonymy makes people appreciate the value of democracy and encourages them to cherish and protect it. Biden declares that democracy, which has been torn during the previous period, has triumphed over threats. Using this metonymy succeeded in connecting logos with pathos, which is one of the goals of using metaphors in political speeches (Mio, 1997 ).

The metonymy of America as a symbol of good things ‘ An American story of decency and dignity. Of love and of healing. Of greatness and of goodness ’ is deliberately created to represent America as an honest and good country. Through this metaphor, Biden appeals not only to the emotions of all people but also to their minds to persuade them that America has been a source of goodness. This finding supports the researchers’ outcomes (Van Dijk, 2006 ; Charteris-Black, 2011 ; Boussaid, 2022 ) that figurative language reveals how important issues are framed in order to advocate specific ideologies by appealing to people’s emotions. Hence, it is a crucial persuasive technique used in political speeches. This implies that Biden is aware of the significance of metaphor as a persuasive rhetoric component.

Intertextuality

Intertextuality has been defined as “the presence of a text in another text” (Genette, 1983 ). Fairclough claims that all texts are intertextual by their very nature and that they are thus constituents of other texts (Fairclough, 1992 ). It is an indispensable strategic feature politicians employ in their speeches to enhance the strength of the speech and reinforce religious, sociocultural, and historical contexts (Kitaeva & Ozerova, 2019 ). Antecedent texts and names are significant components of rhetoric in politics, especially in presidential speeches, because any leader of a country must follow historical, state, moral, and ethical traditions and conventions; referring to precedent texts is one way to get familiar with them. This linguistic phenomenon is necessary for reaching an accurate interpretation of the text, conveying the intended message (Kitaeva & Ozerova, 2019 ), and increasing the credibility of the text, thus getting the audience’s attention to believe in the speaker’s words (Obeng, 1997 ).

Presidents and political intellectuals in the United States have made plenty of statements that will be remembered for years to come. These previous utterances have been unchangeably repeated by other presidents of the USA in different situations throughout American history and are familiar to all Americans. Presidents of the United States frequently quote their predecessors. Former US presidents are frequently mentioned in the corpus of intertextual instances. The oath taken by all presidents—a set rhetorical act of speech—contains a lot of intertextuality. On a macro-structure level, the speaker utilizes intertextuality to give the general theme an appearance by recalling ‘old’ information. Biden quoted Psalm 30:5: “ Weeping may endure for the night, but joy cometh in the morning .” It is a verse that has great resonance for him, given the loss of his wife and daughter in a car accident and his adult son Beau to cancer. On this occasion, he links it to the suffering, with more than 400,000 Americans having died from COVID-19. This biblical and religious type of intertextuality implies that Biden links people’s intimate connection to God with their social and ethical responsibilities.

Another example is when Biden refers to a saying of President Abraham Lincoln in 1863: “ If my name ever goes down into history, it will be for this act and my whole soul is in it .” Although he leads at a completely different time, much like President Lincoln, Biden is grappling with the challenge of a deeply divided country. Deep political schisms have existed in the United States for a long time, but tensions seem to have been exacerbated lately. These nods to Lincoln bring an element of familiarity back to US politics and, potentially, a sense of return to stability after years of turbulence. The president has also quoted a part of the American Anthem Lyrics. He has recited a few lines of the song that highlight his values of hard work, religious faith, and concern for the nation’s future.

The work and prayers of century have brought us to this day. What shall be our legacy? What will our children say… Let me know in my heart When my days are through America, America I gave my best to you.

Choice of lexis

This choice of lexis may have an impact on the way the listeners think and believe what the speaker says. As Aman ( 2005 ) argues, the use of certain words shows the seriousness of the speech to convince people. Regarding this choice of vocabulary, Denham and Roy ( 2005 ) argue that “the vocabulary provides valuable insight into those words which surround or support a concept” (p. 188).

When you review the entire speech of President Biden, one key theme stands out above all others: Democracy. This was reiterated early in his speech and was repeated several times throughout. He has picked the most under-assaulted ideal: ‘democracy’. This word was used (11) times “We’ve learned again that democracy is precious. Democracy is fragile. And at this hour, my friends, democracy has prevailed,” Biden remarked. This would be evident in another period, but after the 2020 election and the attempt to reverse it, the concept is profound.

The president made lots of appeals to unity in his inaugural speech and ignored the partisan conflicts to achieve the supreme goal of enhancing cooperation between all to serve their country. He repeated the words ‘unity’ and ‘uniting’ (11) times.

And we must meet this moment as the United States of America. If we do that, I guarantee you, we will not fail. We have never, ever, ever, failed in America when we have acted together.

This was Biden’s most forceful call for unity. It would be difficult to achieve, however, not just because of the Trump-supporting Republican Party, but also because of the historically close balance of power in the House and Senate.

Biden’s pledge to bridge the divide on policy and earn the support of those who did not support him, rather than seeing them primarily as political opponents, was a mainstay of his campaign, and it was a major theme of his acceptance speech. “ I will be a president for all Americans .” He also tried to play down the dispute between the two parties (Republican and Democratic) “ We must end this uncivil war that pits red against blue, rural versus urban, conservative versus liberal .” This is evident by addressing his opponents from the Republican Party.

To all of those who did not support us, let me say this:Hear me out as we move forward. Take a measure of me and my heart. And if you still disagree, so be it That’s democracy.That’s America. The right to dissent peaceably, within the guardrails of our Republic, is perhaps our nation’s greatest strength. Yet hear me clearly: Disagreement must not lead to disunion. And I pledge this to you: I will be a President for all Americans. I will fight as hard for those who did not support me as for those who did.

The use of idiomatic expressions is also evident in the speech; Biden says ‘If we’re willing to stand in the other person’s shoes just for a moment’ when talking about overcoming fear about America’s future through unity. This expression encourages the addresses to empathize with the speakers’ circumstances before passing any judgment.

The analysis of syntax helps the addressees sense more specifically cohesion. Within a text or phrase, cohesion is a grammatical and lexical connection that keeps the text together and provides its meaning. Halliday, Hasan ( 1976 ) state that “a good discourse has to take attention in relation between sentences and keep relevance and harmony between sentences. Discourse is a linguistic unit that is bigger than a sentence. A context in discourse is divided into two types; first is cohesion (grammatical context) and second is coherence (lexical context)”.

This was shown with the most frequent form of cohesion for the grammatical section, which is the reference with 140 pieces of evidence. Biden employed a variety of conjunctions in his speech to make it easier for his audience to understand his oration, such as “and” (97) times, “but” (16) times, and “so” (8) times.

The analysis also shows that Biden has used various examples of cohesive lexical devices, repetitions, synonyms, and contrast in order to accomplish particular ends such as emphasis, inter-connectivity, and appealing for public acceptance and support. All of these devices contribute to the accurate interpretation of the discourse. It is evident that Biden used contrast/juxtaposition as in:

‘There is truth and there are lies’; ‘Not to meet yesterday’s challenges, but today’s and tomorrow’s’; ‘Not of personal interest, but of the public good’; ‘Of unity, not division’; ‘Of light, not darkness’; ‘through storm and strife, in peace and in war’, ‘We must end this uncivil war that pits red against blue, rural versus urban, conservative versus liberal’. ‘open our souls instead of hardening our hearts’; ‘ we shall write an American story of hope’ .

The use of juxtaposition makes the scene vivid and enhances the listener’s flexible thinking meta-cognition by focusing on important details drawing conclusions and reaching an accurate interpretation of communication.

The use of synonyms such as ‘ heeded-heard; indivisible-one nation; battle-war; victory-triumph; manipulated-manufactured; great nation-our nation-the country; repair-restore-heal-build; challenging-difficult; bringing America together-uniting our nation; fight-combat; anger-resentment-hatred; extremism-lawlessness-violence-terrorism ’ is evident in Biden’s speech. This type of figurative language helps in building cohesion in the speech, formulating and clarifying thoughts and ideas, emphasizing and asserting certain notions, and expressing emotions and feelings. The results are in line with other researchers’ (Lee, 2017 ; Bader & Badarneh, 2018 ) finding that political speeches are emotive; politicians can express feelings and attitudes toward certain issues. Lexical cohesion has also been established through repetition. The most repeated words and phrases in Biden’s speech are democracy, nation, unity, people, racial justice, and America. The repetitive usage of these concepts highlights them as the main basic themes of his speech.

The speaker employed deontic and epistemic modality, which implies that he has used every obligation, permission, and probability or possibility in the speech to exhibit his power by displaying commands, truth claims, and announcements. The speaker’s ideology can be revealed by the modality of permission, obligation, and possibility.

The usage of medium certainty “will” is the highest in numbers (30) times, but the use of low certainty “can” (16) times, “may” (5) times, and high certainty “must” (10) times was noticeably present. The usage of medium certainty is mainly represented by the usage of “will” to introduce future policies and present goals and visions. In critical linguistics terms, the use of low modality in a presidential address may reflect a lack of confidence in the abilities or possibilities of achieving a goal or a vision. That is, the usage of low modality gives more space to the “actor” to achieve the “goal”. For example, the usage of “can” in “ we can overcome this deadly virus ” and “ we can deliver social justice ” does not reflect strong belief, confidence, and assurance from the actor’s side to achieve the goals (social justice, overcoming the deadly virus). The usage of modal verbs in Biden’s speech reflects a balanced personality.

In modality, by using “will”, the speaker tries to convince the audience by giving a promise, and he may hope that what he says will be followed up. By using “can”, the speaker is expressing his ability. In cohesion, it is well organized, which means the speaker tries to make his speech easier to follow by everyone by using “additive conjunctions” or “transition phrases” that have the function of “listing in order”. Lastly, the generic structure of the speech is well structured.

The use of pronouns in political speeches reveals rich information about references to self, others, and identity, agency (Van Dijk, 1993 ). Biden has used the first and second pronouns meticulously to express his vision. The most frequent pronoun Biden has used is ‘we’ with a frequency of (89) which helps him establish trust and credibility in the speech, and a close relationship between him and his audience. This frequency implies that they are one united nation. Whereas he has used the pronoun ‘ I ’ with a frequency of (32). Using these types of pronouns allows the speaker to convey his ideas directly to his audience and make his intended message comprehensible. This balanced usage of pronouns reflects Fairclough’s ( 1992 ) notion of discourse as a social practice rather than a linguistic practice. The analysis demonstrates that the most prominent themes emphasized by Biden are ‘democracy and unity’. These themes have also been accentuated by the overall dominance of the pronoun “we,” which reflects Biden’s perception of America as a good society that needs to be united to successfully go through difficult times. Such notions represent his policies.

Political speech is functional and directive in its very nature. Thus, the language of politics in inaugural speeches is a significant and unique event since it affects people’s minds and hearts concerning certain pressing issues. It is a powerful tool that newly elected political leaders use to promote their new leadership ideas and strategic plans in order to convince people and attract their support. The analysis of the speech reveals that Biden’s language is easy and understandable. Biden employed a variety of rhetorical features to express his ideology. These figurative devices and techniques include creativity, indirectness, intertextuality, metaphor, repetition, cohesion, reference, and synonymy to achieve his political ideologies; assuring Americans and the world of his good intentions towards uniting Americans and working collaboratively with other nations to persevere through difficult times.

The overall themes expressed in this speech are the timeless values of unity and democracy. They are the cornerstones and key ideological components of Biden’s speech. This value-based orientation indicates their paramount recurrent semantic-cognitive features. The construction of the meaning of such values lies in the sociocultural and political context of the USA and the whole world in general and America in particular. Biden’s speech includes certain ideals, like "unity" to work together for the nation’s development, "democracy" to exhibit the "democracy" that has recently been assaulted, "equality" to treat all American people equally, and "freedom" to let individuals do whatever they want. Such themes are essential, especially in times of the worst crisis of COVID-19 encountering the world since they help him reassure his nation and the world of some improvements and promise them progress and prosperity in the years to come. To sum up, the results showed that the speaker used appropriate language in addressing the theme of unity. The speaker used religion and history as a source of rhetorical persuasive devices. The overall tone of the speech was confident, reconciliatory, and hopeful. We can say that language is central to meaningful political discourse. So, the relationship between language and politics is a very significant one.

The study examined the main linguistic strategies used in President Biden’s inauguration speech presented in 2021. The analysis has revealed that Biden in this speech intends to show his feelings (attitudes), his goals (reviewing the US administration), and his power to take over the US presidential office. It has also disclosed Biden’s ideological standpoint that is based on the central values of democracy, tolerance, and unity. Biden’s speech includes certain ideals, like "unity" to work together for the nation’s development, "democracy" to exhibit the "democracy" that has recently been assaulted, "equality" to treat all American people equally, and "freedom" to let individuals do whatever they want. To convey the intended ideological political stance, Biden used certain persuasive strategies including creativity, metaphor, contrast, indirectness, reference, and intertextuality for addressing critical issues. Creative expressions were drawn, highlighting and magnifying significant real issues concerning unity, democracy, and racial justice. Intertextuality was employed by resorting to an extract from one of the American presidents in order to convince Americans and the international community of his ideas, vision, and policy. It appeared that indirect expressions were also used for discussing politically sensitive issues in order to acquire a political and interactional advantage over his political opponents. His referencing style shows his interest in others and their unity. The choice of these strategies may have an influence on how the listeners think and believe about what the speaker says. Significant ideologies encompassing unity, equality, and freedom for US citizens were stated implicitly and explicitly. The study concluded that the effective use of linguistic and rhetorical devices is recommended to construct meaning in the world, be persuasive, and convey the intended vision and underlying ideologies.

The study suggests some implications for pedagogy and academic research. Researchers, linguists, and students interested in discourse analysis may find the data useful. The study demonstrates a sort of connection between political scientists, linguistics, and discourse analysts by clarifying distinct issues using different ideas and discourse analysis approaches. It has important ramifications for the efficient use of language to advance certain moral principles such as freedom, equality, and unity. It unravels that studying how language is used in a certain context allows people to disclose or analyze more about how things are said or done, or how they might exist in different ways in other contexts. It also shows that studying political language is crucial because it helps language users understand how a language is used by those who want power, seek to exercise it and maintain it to gain public attention, influence people’s attitudes or behaviors, provide information that people are unaware of, explain one’s attitudes or behavior, or persuade people to take certain actions. Getting students engaged in CDA research such as the current study would help them be more adept at navigating and using rhetorical devices and CDA tactics, as well as considering the underlying ideologies that underlie any written piece. Based on the analysis, it is recommended that more research studies be conducted on persuasive strategies in other political speeches.

Data availability

All data analyzed in this study are included in this published article. They are available at this link: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/01/20/inaugural-address-by-president-joseph-r-biden-jr/ .

Alfayes H (2009) Martin Luther King “I have a dream”: Critical discourse analysis. KSU faculty member websites. Retrieved August 28, 2009, from, http://faculty.ksu.edu.sa/Alfayez.H/Pages/CDAofKing’sspeechIhaveadream.aspx

Almahasees Z, Mahmoud S (2022) Persuasive strategies utilized in the political speeches of King Abdullah II: a critical discourse analysis. Cogent Arts Humanit 9(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2022.2082016

Article Google Scholar

Aman I (2005) Language and power: a critical discourse analysis of the Barisan Nasional’s Manifesto in the 2004 Malaysian General Election1. In: Le T, Short M (eds.). Proceedings of the International Conference on Critical Discourse Analysis: Theory into Research, 15–18 November 2005. Tasmania: University of Tasmania, viewed August 20, 2009, from http://www.educ.utas.edu.au/conference/files/proceedings/full-cda-proceedings.pdf

Amir S (2021) Critical discourse analysis of Jo Biden’s inaugural speech as the 46th US president. Period Soc Sci 1(2):1–13

Google Scholar

Bader Y, Badarneh S (2018) The use of synonyms in parliamentary speeches in Jordan. AWEJ Transl Liter Stud 2(3):43–67

Bani-Khaled T, Azzam S (2021) The theme of unity in political discourse: the case of President Joe Biden’s inauguration speech on the 20th of January 2021. Arab World Engl J 12(3):36–50. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3952847

Beyer BK (1995) Critical thinking. Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, Bloomington, IN

Biden J (2021) Inaugural address by President Joseph R. Biden, Jr. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/01/20/inaugural-address-by-president-joseph-r-biden-jr/#:~:text=We%20must%20set%20aside%20the,joy%20cometh%20in%20the%20morning.&text=The%20world%20is%20watching%20today,come%20out%20stronger%20for%20it

Boussaid Y (2022) Metaphor-based analysis of Joe Biden’s and George Washington’s inaugural speeches. Int J Engl Linguist 12(3):1–17

Cameron D (2001) Working with spoken discourse. Sage, London

Charteris-Black J (2011) Politicians and rhetoric: the persuasive power of metaphor. Springer

Charteris-Black J (2018) Analysing political speeches: rhetoric, discourse and metaphor. Bloomsbury Publishing

Chouliaraki L, Fairclough N (1999) Discourse in late modernity: rethinking critical discourse analysis. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh

Denham G, Roy A (2005) A content analysis of three file-selves. In: Le T, Short M (eds.). Proceedings of the International Conference on Critical Discourse Analysis: Theory into Research, 15–18 November 2005. Tasmania: University of Tasmania, viewed August 20, 2009, from http://www.educ.utas.edu.au/conference/Files/proceedings/full-cda-proceedings.pdf

Fairclough N (1989) Language and power. Longman, Harlow

Fairclough N (1992) Discourse and social change. Polity Press, Cambridge

Fairclough N (1993) Critical discourse analysis and the marketization of public discourse: the universities. Discourse Soc 4(2):133–168

Fairclough N (1995) Critical discourse analysis: the critical study of language

Genette G (1983) “Transtextualité”. Magazine Littéraire 192:40–41

Haider AS (2016) A corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis of the representation of Qaddafi in media: evidence from Asharq Al-Awsat and Al-Khaleej newspapers. Int J Linguist Commun 4(2):11–29. https://doi.org/10.15640/ijlc.v4n2a2

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Halliday MAK, Hasan R (1976) Cohesion in English (No. 9). Routledge

Iqbal Z, Aslam MZ, Aslam T, Ashraf R, Kashif M, Nasir H (2020) Persuasive power concerning COVID-19 employed by Premier Imran Khan: a socio-political discourse analysis. Register J 13(1):208–230

Janks H (1997) Critical discourse analysis as a research tool. Discourse Stud Cult Polit Educ 18(3):329–342

Kitaeva E, Ozerova O (2019) Intertextuality in political discourse. In: Language, power, and ideology in political writing: Emerging research and opportunities. IGI Global. pp. 143–170

Kozlovskaya NV, Rastyagaev AV, Slozhenikina JV (2020) The creative potential of contemporary Russian political discourse: from new words to new paradigms. Train Lang Cult 4(4):78–90

Kriyantono R (2019) Syntactic analysis on the consistency of Jokowi’s rhetorical strategy as president and presidential candidate. J Appl Stud Lang 3(2):127–139. https://doi.org/10.31940/jasl.v3i2.1419

Lakoff G, Johnson M (1980) Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago, Chicago, IL

Lauwren S (2020) Interpersonal functions in Greta Thunberg’s “civil society for rEUnaissance” speech. J Appl Stud Lang 4(2):294–305. https://doi.org/10.31940/jasl.v4i2.2084

Lee J (2017) “Constructing educational achievement in political discourse: an analysis of Obama’s Interview at the Education National Summit 2012.” Penn GSE Perspect Urban Educ 13:1–4

Mio JS (1997) Metaphor and politics. Metaphor Symbol 12(2):113–133

Moody S, Eslami ZR (2020) Political discourse, code-switching, and ideology. Russ J Linguist 24(2):325–343

Nikitina A (2011) Successful public speaking. Bookboon

Nusartlert A (2017) Political language in Thai and English: findings and implications for society. J Mekong Soc 13(3):57–75

Obeng SG (1997) Language and politics: indirectness in political discourse. 8(1), 49–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926597008001004

Pierson P, Skocpol T (2002) Historical institutionalism in contemporary political science. Polit Sci State Discip 3(1):1–32

Pramadya TP, Rahmanhadi AD (2021) A day of history and hope: a critical discourse analysis of Joe Biden’s Inauguration speech. Rainbow 10(2):1–10

Prasetio A, Prawesti A (2021) Critical discourse analysis in word count of Joe Biden’s inaugural address. Discourse analysis: a compilation articles on discourse and critical discourse analysis, 1:1–12

Renaldo ZA, Arifin Z (2021) Presupposition and ideology: a critical discourse analysis of Joe Biden’s Inaugural Speech. PROJECT (Prof J Engl Educ) 4(3):497–503

Scheidel TM (1967) Persuasive speaking. Scott Foresman, Glenview

Schmidt VA (2008) Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Ann Rev Polit Sci-Palo Alto 11:303

Thibodeau PH, Boroditsky L (2011) Metaphors we think with: The role of metaphor in reasoning. PLoS ONE 6(2):e16782

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Van Dijk TA (1993) Principles of critical discourse analysis. Discourse Soc 4(2):249–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926593004002006

Van Dijk TA (2006) Discourse and manipulation. Discourse Soc 17(3):359–383

Van Dijk TA (2011) Discourse and ideology. In: Van Dijk (ed) Discourse studies: a multidisciplinary introduction. SAGE, London, p 379-407

Van Dijk TA (2015) Critical discourse analysis. In: Tannen D, Hamilton HE, Schiffrin D (eds) The handbook of discourse analysis, 2nd edn. Wiley, London, p 466–485

Wodak R, Meyer M (2009) Critical discourse analysis: History, agenda, theory and methodology. Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis 2:1-33

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Arts, The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan

Nisreen N. Al-Khawaldeh & Ali F. Khawaldeh

Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Arts and Languages, Jadara University, Irbid, Jordan

Luqman M. Rababah & Alaeddin A. Banikalef

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nisreen N. Al-Khawaldeh .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplemantry data, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Al-Khawaldeh, N.N., Rababah, L.M., Khawaldeh, A.F. et al. The art of rhetoric: persuasive strategies in Biden’s inauguration speech: a critical discourse analysis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 936 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02450-y

Download citation

Received : 20 August 2023

Accepted : 22 November 2023

Published : 11 December 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02450-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Search Menu

- Supplements

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About Digital Scholarship in the Humanities

- About the European Association for Digital Humanities

- About the Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1 introduction, 2 related work, 3 electoral corpus, 4 evaluation of stylistic characteristics of the candidates, 5 evaluation of topical characteristics of the candidates, 6 conclusion, acknowledgments.

- < Previous

Analysis of the style and the rhetoric of the 2016 US presidential primaries

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jacques Savoy, Analysis of the style and the rhetoric of the 2016 US presidential primaries, Digital Scholarship in the Humanities , Volume 33, Issue 1, April 2018, Pages 143–159, https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqx007

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This present article examines the verbal style and rhetoric of the candidates of the 2016 US presidential primary elections. To achieve this objective, this study analyzes the oral communication forms used by the candidates during the TV debates. When considering the most frequent lemmas, the candidates can be split into two groups, one using more frequently the pronoun ‘I’, and the second favoring more the ‘we’ (which corresponds to candidates leaving the presidential run sooner). According to several overall stylistic indicators, candidate Trump clearly adopted a simple and direct communication style, avoiding complex formulation and vocabulary. From a topical perspective, our analysis generates a map showing the affinities between candidates. This investigation results in the presence of three distinct groups of candidates, the first one with the Democrats (Clinton, O’Malley, and Sanders), the second with three Republicans (Bush, Cruz, Rubio), and the last with the duo Trump and Kasich, with, at a small distance, Paul. The over-used terms and typical sentences associated with each candidate reveal their specific topics such as ‘simple flat tax’ for Cruz, ‘balanced budget’ for Kasich, negativity with Trump, or critiques against large corporations and Wall Street for Sanders.

The 2016 US presidential election was characterized by two figures, both unloved by the majority of Americans ( Yourish, 2016 ). Donald Trump seemed sincere, authentic, saying what he thinks, putting aside political correctness. For him, all appearances and comments on the media were an opportunity for self-promotion. He believed that the repetition of a simple message, even if false ( Millbank, 2016 ), is enough to persuade the citizens that it is true. His image was centered around his verbosity, egocentricity, and pomposity. Just after the announcement of his candidacy for President (16 June 2015), his candidacy was mainly viewed as marginal, without pertinent interest, and without a real future. But Trump was able to beat all his opponents and won the nomination for the Republican party (21 July 2016).

Nominated by the Democrats (28 July 2016), Hillary Clinton always appeared as a cold woman, a member of the political establishment rejected by many people. She did not like the press and the media and, in return, they do not like her much either. This aspect could be related to her first years at the White House as an overqualified First Lady who wanted to play a principal role in politics (e.g. health care reform in 1993). For some people, she was even a crook and a liar, or, at least, dishonest ( Sainato, 2016 ). When her campaign starts (14 April 2015), everything seemed simple and the road to the nomination seems without any real problem. The presence of Bernie Sanders occupying a position more on the left demonstrates that the Democratic primaries were more difficult than expected. Finally, her email case and FBI investigations were a real concern for her image in the public, especially during the general election campaign.

Even if Hillary’s candidature appeared more natural, she needed to convince the Democrats and their sympathizers that she was the right person who can win the general election. Inside the Republican party, the outcome of the fight was more uncertain, in part by the larger number of candidates (seventeen vs. six), and the leading position occupied by Jeb Bush in the beginning of the primaries. Despite the now-known election outcome, the candidates’ use of language during the primary season raises some pertinent research questions. How were the respective nominees able to win the primaries according to their speeches? Does the analysis of TV debates make it possible to detect their style and rhetoric? Can one discover the rhetorical features that can explain a Trump or Clinton success? Can one measure the stylistic distance between the candidates in both parties?

To answer these questions, the current study will focus on the US primaries’ TV debates. Here, rhetoric is defined as the art of effective and persuasive speaking, the way to motivate an audience, while language style is presented as pervasive and frequent forms used by an author for mainly esthetical value ( Biber and Conrad, 2009 ). The analysis will use the oral communication form, a more direct and spontaneous way of interacting, reflecting more closely the personal style of each candidate. The style of the written messages (evident in prepared statements by the candidates) differs from the oral dialogue ( Biber et al. , 2002 ). Moreover, the statements are certainly authored, at least in part, by a team of speechwriters. Therefore, the two forms of communication must be analyzed separately.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. The next section presents some related research in computer-based analysis of political speeches. The third section presents briefly some statistics about our corpus. The fourth describes and applies different measurements and methods to define and compare the rhetoric and style of the different candidates. The fifth section visualizes the relative position of each candidate in stylistic and topical spaces. A conclusion draws the main findings of this study.

Political texts have been the subject of various studies discussing different aspects of them. Focusing on governmental speeches written in French, Labbé and Monière (2003 ; 2008a ) have created a set of governmental corpora such as the ‘Speeches from the Throne’ (Canada and Quebec), a corpus of the general policy statements of French governments ( Labbé and Monière, 2003 ; 2008a ) as well as a collection of press releases covering the French presidential campaign of 2012 ( Labbé and Monière, 2013 ; Arnold and Labbé, 2015 ). Similar research has been conducted with other languages, such as Italian ( Pauli and Tuzzi, 2009 ). From these analyses, one can observe, for example, that governmental institutions tend to smooth out the differences between political parties when exercising command. Moreover, the temporal period of the documents constitutes an important factor explaining the variations between presidents or prime ministers. The presence of a strong leader is usually accompanied with a real change in the style and vocabulary of governmental speeches ( Labbé and Monière, 2003 ; Savoy, 2015c ).

Focusing on the USA, recent studies confirm these findings as, for example, using the ‘State of the Union’ ( Savoy, 2015a ) or inaugural addresses ( Kubát and Cech, 2016 ). Beside time frame, exceptional events (e.g. worldwide war, deep economic depression) may change noticeably the style. These results present also the stylistic evolution over more than two centuries and can be compared to those achieved using traditional methods as, for example, by Lim (2002) .

Differentiations between political parties can however be observed as, for example, studies based on tweets ( Sylwester and Purver, 2015 ). Such differences tend to be correlated with psychological factors. For example, positive emotion words occur more frequently in Democrats’ tweets than in Republican ones, as well as swear expressions, or first singular person pronouns (e.g. I, me). In a related study using a training corpus, Laver et al. (2003) describe a methodology to extract political positions from texts. In a similar vein, Yu (2008) demonstrates that machine learning methods (e.g. SVM and naïve Bayes) can be trained to classify congressional speeches according to political parties. Better performance levels can be achieved when the training examples are extracted from the same time period as the test set. In another study, Yu (2013) reveals that (political) feminine figures tend to use emotional words more frequently and employ more personal pronouns than men. A more general overview of using different computer-based strategy to detect and extract topical information from political texts can be found in ( Grimmer and Stewart, 2013 ).

The web-based communication (e.g. tweets, blogs, chats) was used by O’Connor et al. (2010) to estimate the popularity of the Obama administration. This study found a positive correlation between the presidential approval polls and positive tweets containing the hashtag #obama. Such a selection strategy produces a low recall because many tweets about Obama’s administration are not considered). As a tweet is rather short (in mean eleven words), the sentiment estimation is simply the count of the number of positive and negative words appearing in the OpinionFinder dictionary ( Wilson et al. , 2005 ).

Also grounded on several dictionaries (or categories), Young and Soroka (2012) describe how one can detect and measure sentiments appearing in political texts. The suggested approach is rather similar to O’Connor et al. ’s work (2010), counting the frequency of occurrence of words appearing in a dictionary of positive or negative emotion words. Using also some lists of words, Hart (1984) has designed and implemented a political text analyzer called Diction . Based on US presidential speeches, that study presents the rhetorical and stylistic differences between the US presidents from Truman to Reagan, while a more recent book ( Hart et al. , 2013 ) exposes the stylistic variations from G. W. Bush to Obama. Using the Diction system, Bligh et al. (2010) analyze the rhetoric of H. Clinton during the 2008 presidential election. Hillary appears more feminine than the other candidates, using more ‘I’ than ‘we’, and showing a higher frequency in the category ‘Human interest’ (e.g. family, man, person, etc.).

As another example, Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC; Tausczik and Pennebaker, 2010 ) regroups different categories used to evaluate the author’s psychological status (e.g. feminine, emotion, leadership), as well as her/his style (e.g. grounded on personal pronouns ( Pennebaker, 2011 )). The underlying hypothesis is to assume that the words serve as guides to the way the author thinks, acts, or feels. In LIWC, the generation of the word lists was done based on the judgments of three experts instead of simply concatenating various existing lists. Using the LIWC system, Slatcher et al. (2007) were able to determine the personalities of different political candidates (US presidential election in 2004). They defined the psychological portrait both on single measurements (e.g. the relative frequency of different pronouns, positive emotions) and using a set of composite indices reflecting the cognitive complexity, presidentially, or honesty of each candidate. These personality measurements were in agreement with different opinion polls. For example, G. W. Bush used more frequently the pronoun ‘I’, positive emotion words (e.g. happy, truly, win), and the future tense. The public perceived J. Kerry as a kind of depressed person, serious, somber, and cold, adopting more frequently negative emotion expressions (e.g. sad, worthless, cut, lost) and physical words (e.g. head, ache, sleep).

To conclude briefly, previous studies have mainly analyzed governmental speeches, and less frequently the electoral speeches ( Boller, 2004 ) or related messages (e.g. such as press releases; Labbé and Monière, 2013 ). A few studies focus on the legislative level (e.g. the Congress) and these studies are mainly grounded on the written form. More recently, the web-based communication channels have been studied, but in this perspective, those studies are using more often tweets and less frequently blogs, or audio and video media (e.g. YouTube). The present study is focusing on two less explored aspects, namely, the electoral campaign on the one hand, and on the other, the oral form.

To analyze the rhetoric and style adopted by the candidates during the primaries of the 2016 US primary election, the transcripts of the TV debates have been downloaded from the Internet (mainly from the Web site www.presidency.ucsb.edu ). For the Republican candidates (Jeb Bush, Ted Cruz, John Kasich, Rand Paul, Marco Rubio, and Donald Trump), twelve TV debates were organized, from the 1st one held on 6 August 2015 with ten candidates, to the last one organized on 10 March 2016 with four candidates. For the Democrats (Hillary Clinton, Martin O’Malley, and Bernie Sanders), one can count nine TV debates held from 13 October 2015 (with five candidates) to 9 March 2016 (with two candidates).

Due to space limitations, not all possible candidates have been retained. Some persons never appear in a TV debate (e.g. Pataki (R), Jindal (R), Lessig (D)) or just appear in one (e.g. Webb (D)) or two debates (e.g. Walker (R)) while others have been ignored because they have played a minor role during the electoral campaign (e.g. Carson (R) or Christie (R)).

From a stylistic point of view, this corpus is homogenous, corresponding to an oral communication form, extracted from a short period of time, and with the same main objectives (convincing the people, answering questions, presenting their ideas and solutions). Several factors influencing the style are therefore fixed. The remaining variations can be largely explained by the speaker.

Even if the topics are not directly and fully controlled by the candidates, the debate format corresponds to a more spontaneous form of communication, able to reveal more closely the real person behind her/his projected image. Of course, one can raise the question of the speaker’s spontaneity because Donna Brazile, who worked for CNN, provided, at least once, prepared questions to Clinton before a debate. This phenomenon is assumed to be the exception rather than the norm.

One can consider that electoral speeches delivered by the candidates correspond also to an oral communication form and thus can be included in our corpus. However, as mentioned by Biber and Conrad (2009 , p. 262):

Language that has its source in writing but performed in speech does not necessarily follow the generalization [written vs. oral]. That is, a person reading a written text aloud will produce speech that has the linguistic characteristics of the written text. Similarly, written texts can be memorized and then spoken.

Some statistics about candidates’ speeches and comments

As shown in Table 1 , Paul and O’Malley correspond to the smallest values, both being present for a relatively short period of time during this electoral campaign. Clinton appears with the largest number of tokens, followed by Sanders, Trump, Rubio, and Cruz.

To highlight the different styles adopted by the candidates, Biber and Conrad (2009) indicate that such a study should be based on ubiquitous and frequent forms. Thus, the analysis of the most frequent ones is certainly a good starting point, as shown in the first sub-section. The second proposes to consider four overall stylistic measurements and applies them to the different candidates while the last sub-section describes the differences in the distribution of the grammatical categories between candidates.

4.1 Most frequent lemmas

To analyze the rhetoric and style of presidential writings, the first quantitative linguistics studies focused on the word usages and their frequencies. As the English language has a relatively simple morphology, working on inflected forms (e.g. ‘we, us, ours’, or ‘wars, war’) or lemmas (dictionary entries such as ‘we’ or ‘war’ from the previous example) often lead to similar conclusions.

To define the lemma of each token, the part-of-speech (POS) tagger developed by Toutanova et al. (2003) was first applied. Given a sentence as input, this system is able to add the corresponding POS tag to each token. For example, from the sentence ‘But I also know this problem is not going away’, the POS tagger returns ‘But/ cc I/ prp also/ rb know/ vbp this/ dt problem/ nn is/ vbz not/ rb going/ vbg away/ rb ./.’. Tags may be attached to nouns ( nn , noun, singular, nns noun, plural, nnp proper noun, singular), verbs ( vb , lemma, vbg gerund or present participle, vbp non-3rd-person singular present, vbz 3rd-person singular present), adjectives ( jj , jjr adjective in comparative form), personal pronouns ( prp ), prepositions ( in ), and adverbs ( rb ). These morphological tags ( Marcus et al. , 1993 ) correspond mainly to those used in the Brown corpus ( Francis and Kucera, 1982 ). With this information one can derive the lemma by removing the plural form of nouns (e.g. jobs/ nns → job/ nn ) or by substituting inflectional suffixes of verbs (e.g. detects/ vbz → detect/ vb ).

Our first analysis considers the most frequent lemmas occurring in the oral interventions of the candidates during the TV debates of the primaries. Unsurprisingly, the article ‘the’ and the verb ‘be’ (lemma of the word types am, is, are, was, etc.) appear regularly in the first two ranks. Looking at the most frequent lemmas in the Brown corpus ( Francis and Kucera, 1982 ), the first two are the same, but after them the order changes. In the Brown corpus, the top ten most frequent lemmas are as follows: the, be, of, and, to, a, in, he, have, it.

The top ten most frequent lemmas according to TV debates

Note. The personal pronouns are depicted in bold.

In this table, one can see another interesting fact related to the frequencies of the pronouns ‘we’ and ‘I’. Former governors tend to use more frequently the ‘we’ than the ‘I’ (e.g. Bush, Kasich) with O’Malley having a very distinctive style in this point of view. Usually Senators (e.g. Cruz, Paul, Clinton, Sanders) tend to prefer using the pronoun ‘I’, at least during an electoral campaign. The candidates who stayed longer in this campaign have a clear preference for the ‘I’ over the ‘we’. The pronoun ‘we’ stays ambiguous (Who is behind the ‘we’? Myself and the future government? Me and the people? Me and the workers? Me and the Congress?). Finally, the champion in the usage of ‘I’ is Trump who clearly has adopted a distinct style in the campaign, putting the light more on his ego.

4.2 Global stylistic measurements

To define an overall measurement of the style, various studies have proposed different measures. As a first indicator, one can consider the mean sentence length (MSL) reflecting a syntactical choice. The sentence boundaries are defined by the POS tagger ( Toutanova et al. , 2003 ) and correspond to ‘strong’ punctuation symbols (namely, periods, question, and exclamation marks). Usually, a longer sentence is more complex to understand, especially in the oral communication form. Using the ‘State of the Union’ addresses given by the Founding Fathers, this average value is 39.6 (with Madison depicting the highest MSL with 44.8 tokens/sentence). With Obama, the MSL decreases to 18.5 tokens/sentence. These examples indicate clearly that the style is changing over time. Currently, the preference goes to a shorter formulation, simpler to understand for the audience.

Four global stylistic measurements according to TV debates

Note. Extreme values are depicted in bold.

A relatively high LD percentage indicates a more complex text, containing more information. Using the transcripts of the TV debates, the LD values vary from 36.6% (Trump) to 44.6% (Cruz). Trump’s style appears, here too, as distinct from the others, providing his answers and comments around functional words. Cruz adopts an opposite style, focusing more on topical forms and expressions.