- Milano Cortina 2026

- Brisbane 2032

- Olympic Refuge Foundation

- Olympic Games

- Olympic Channel

- Let's Move

How sport can have a positive impact on mental and physical health

It’s not always easy to start a workout, but research shows that sport and exercise are beneficial not only for your physical health, but your mental well-being, too. Let us help!

Health experts and Olympic athletes agree: Your mental and physical health benefit when you get active and participate in sport – whatever that means for you.

From daily exercise to choosing a sport to practice or play, the body and mind are worked in new and different ways each time you move your body.

On June 23rd every year we come together to celebrate that, as part of Olympic Day.

For the 2020 edition, we connected with Olympians around the world for Olympic Day 2020 at-home workouts – and a reminder: We’re stronger together, especially when we stay active!

And those are still available online to help inspire you today.

Sport benefits: Both the physical and mental

While the physical benefits are numerous (more on that below), the UK's National Health Service (NHS) report that people who take part in regular physical activity have up to a 30 percent lower risk of depression.

Additionally, exercise can help lower anxiety, reduce the risk of illness and increase energy levels. Want better sleep? Work up a good sweat!

Exercise can help you fall asleep faster and sleep for longer, research says.

It was in June 2020 that the IOC partnered with the World Health Organization and United Nations to promote the #HEALTHYTogether campaign , which highlights the benefits of physical activity in the face of the pandemic.

Over 50 at-home workouts are searchable across Olympics.com for you, each which help further the idea that moving and challenging the body can only prove beneficial for your physical and mental well-being.

The athletes' perspective: 'I used this strength to survive'

“If I had sat doing nothing, I would have gone crazy,” says Syria's Sanda Aldass , who fled the trauma of civil war in her country, leaving behind her husband and infant child.

Instead, she had judo - and has been selected for the IOC Refugee Olympic Team Tokyo 2020 for the Games in 2021.

“Running around and doing some exercises filled up my time and also kept me in good mental health,” Sanda said of the impact of sport on her life during nine months spent in a refugee camp in the Netherlands in 2015.

The same power of sport goes for Iranian taekwondo athlete Ali Noghandoost.

"When I had to leave my family and my home in Iran, the first things I packed in my bag were my belt, my dobok, my shoes and my mitt for taekwondo," Noghandoost said . "I took some documents that said I was a champion in Iran and in a national team, so I could prove I was a fighter and continue to train in any city I went to."

"Taekwondo did not only help me physically; mentally, it stopped me from thinking about giving up and that we wouldn’t make it. I used this strength to survive," he added.

Noghandoost has worked as a coach for refugees in Croatia, where he has tried to pass the power of sport on to the next generation.

"When you’re living in a refugee camp, it’s a really hard situation, but when you play sport, you can release any negative energy and feel free. It’s a space – a paradise – for them to be themselves."

A member of the IOC Refugee Olympic Team Rio 2016, Yiech Pur Biel says that the team provided a message of hope for those watching around the world.

"We were ambassadors for a message of hope, that anything is possible," Biel said . "A good thing had come out of our situations. The world understood. I am called a refugee, but you never know when someone else might become a refugee, through war or persecution. We wanted to show that we responded positively. So that made me very happy. Through sport, we can unite and make the world better."

Sport as a tool for much - including mental health

Sport is a powerful tool no matter from what angle you look at it, including mental health. The Olympic Refugee Foundation (ORF) has recently launched two different programs that are aimed at helping young refugees dream of a brighter future - through sport.

One of those programs, Game Connect, is a three-year initiative that was launched in August 2020 and aims to "improve the mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of young refugees by improving their access to safe sport," as explained on Olympics.com last year.

We are "embarking on a three-year project to improve the psychosocial wellbeing and mental health of young refugees, working together with well-trained community-based coaches to deliver a Sport for Protection program and activities," explained Karen Mukiibi of Youth Sport Uganda, which has partnered with the ORF.

Related content

Stay Healthy, Stay Strong, Stay Active with the Olympic Day home workout

Paris 2024 – getting children moving more at school for 30 minutes a day

Daily routine: five things to do - 11 April 2020

Olympic Day Workout | #StayActive with Bryan Clay

Olympic Day Workout | #StayActive with Hong Zhang

You may like.

The health benefits of sport and physical activity

Although research interest on physical activity and health dates back to the 1950s, the breakthrough in the scientific evidence on health benefits of physical activity largely took place during the 1980s and 1990s. There is an overwhelming amount of scientific evidence on the positive effects of sport and physical activity as part of a healthy lifestyle. The positive, direct effects of engaging in regular physical activity are particularly apparent in the prevention of several chronic diseases, including: cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, hypertension, obesity, depression and osteoporosis.

The Report from the United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force on Sport for Development and Peace states that young people can benefit from physical activity as it contributes to developing healthy bones, efficient heart and lung function as well as improved motor skills and cognitive function. Physical activity can help to prevent hip fractures among women and reduce the effects of osteoporosis. Remaining physically active can enhance functional capacity among older people, and can help to maintain quality of life and independence.

Physical activity and psychosocial health

The WHO has estimated that “one in four patients visiting a health service has at least one mental, neurological or behavioural disorder, but most of these disorders are neither diagnosed nor treated”. A number of studies have shown that exercise may play a therapeutic role in addressing a number of psychological disorders . Studies also show that exercise has a positive influence on depression. Physical self-worth and physical self-perception, including body image, has been linked to improved self-esteem. The evidence relating to health benefits of physical activity predominantly focuses on intra-personal factors such as physiological, cognitive and affective benefits, however, that does not exclude the social and inter-personal benefits of sport and physical activity which can also produce positive health effects in individuals and communities.

Sport and physical activity as part of a healthy lifestyle

A number of factors influence the way in which sport and physical activity impacts on health in different populations. Sport and physical activity in itself may not directly lead to benefits but, in combination with other factors, can promote healthy lifestyles. There is evidence to suggest that changes in the environment can have a significant impact on opportunities for participation and in addition, the conditions under which the activity is taking place can heavily impact on health outcomes . Elements that may be determinants on health include nutrition, intensity and type of physical activity, appropriate footwear and clothing, climate, injury, stress levels and sleep patterns.

Sport and physical activity can make a substantial contribution to the well-being of people in developing countries . Exercise, physical activity and sport have long been used in the treatment and rehabilitation of communicable and non-communicable diseases . Physical activity for individuals is a strong means for the prevention of diseases and for nations is a cost-effective method to improve public health across populations.

Key Reading

- Health Benefits of Physical Activity: the evidence

- Health and Development Through Physical Activity and Sport

Steering Board Members

- Systematic review update

- Open access

- Published: 21 June 2023

The impact of sports participation on mental health and social outcomes in adults: a systematic review and the ‘Mental Health through Sport’ conceptual model

- Narelle Eather ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6320-4540 1 , 2 ,

- Levi Wade ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4007-5336 1 , 3 ,

- Aurélie Pankowiak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0178-513X 4 &

- Rochelle Eime ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8614-2813 4 , 5

Systematic Reviews volume 12 , Article number: 102 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

65k Accesses

13 Citations

305 Altmetric

Metrics details

Sport is a subset of physical activity that can be particularly beneficial for short-and-long-term physical and mental health, and social outcomes in adults. This study presents the results of an updated systematic review of the mental health and social outcomes of community and elite-level sport participation for adults. The findings have informed the development of the ‘Mental Health through Sport’ conceptual model for adults.

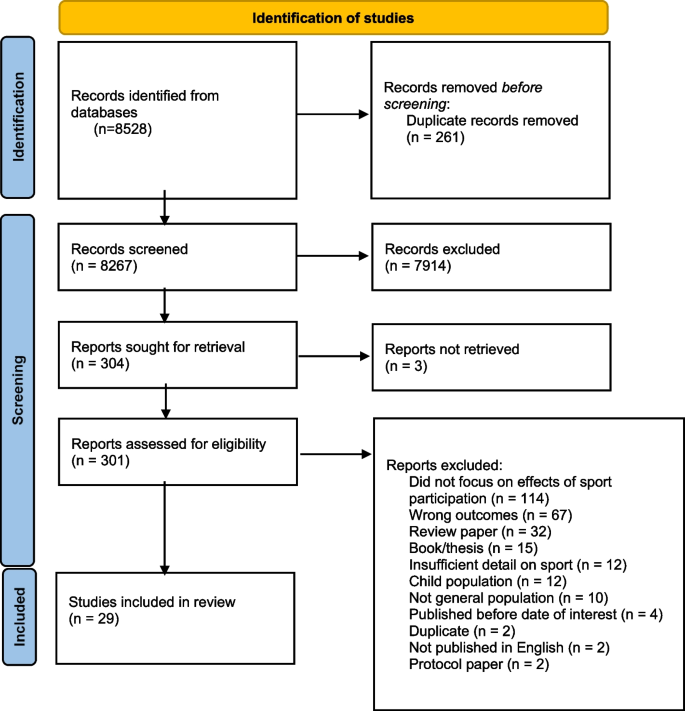

Nine electronic databases were searched, with studies published between 2012 and March 2020 screened for inclusion. Eligible qualitative and quantitative studies reported on the relationship between sport participation and mental health and/or social outcomes in adult populations. Risk of bias (ROB) was determined using the Quality Assessment Tool (quantitative studies) or Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (qualitative studies).

The search strategy located 8528 articles, of which, 29 involving adults 18–84 years were included for analysis. Data was extracted for demographics, methodology, and study outcomes, and results presented according to study design. The evidence indicates that participation in sport (community and elite) is related to better mental health, including improved psychological well-being (for example, higher self-esteem and life satisfaction) and lower psychological ill-being (for example, reduced levels of depression, anxiety, and stress), and improved social outcomes (for example, improved self-control, pro-social behavior, interpersonal communication, and fostering a sense of belonging). Overall, adults participating in team sport had more favorable health outcomes than those participating in individual sport, and those participating in sports more often generally report the greatest benefits; however, some evidence suggests that adults in elite sport may experience higher levels of psychological distress. Low ROB was observed for qualitative studies, but quantitative studies demonstrated inconsistencies in methodological quality.

Conclusions

The findings of this review confirm that participation in sport of any form (team or individual) is beneficial for improving mental health and social outcomes amongst adults. Team sports, however, may provide more potent and additional benefits for mental and social outcomes across adulthood. This review also provides preliminary evidence for the Mental Health through Sport model, though further experimental and longitudinal evidence is needed to establish the mechanisms responsible for sports effect on mental health and moderators of intervention effects. Additional qualitative work is also required to gain a better understanding of the relationship between specific elements of the sporting environment and mental health and social outcomes in adult participants.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The organizational structure of sport and the performance demands characteristic of sport training and competition provide a unique opportunity for participants to engage in health-enhancing physical activity of varied intensity, duration, and mode; and the opportunity to do so with other people as part of a team and/or club. Participation in individual and team sports have shown to be beneficial to physical, social, psychological, and cognitive health outcomes [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Often, the social and mental health benefits facilitated through participation in sport exceed those achieved through participation in other leisure-time or recreational activities [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Notably, these benefits are observed across different sports and sub-populations (including youth, adults, older adults, males, and females) [ 11 ]. However, the evidence regarding sports participation at the elite level is limited, with available research indicating that elite athletes may be more susceptible to mental health problems, potentially due to the intense mental and physical demands placed on elite athletes [ 12 ].

Participation in sport varies across the lifespan, with children representing the largest cohort to engage in organized community sport [ 13 ]. Across adolescence and into young adulthood, dropout from organized sport is common, and especially for females [ 14 , 15 , 16 ], and adults are shifting from organized sports towards leisure and fitness activities, where individual activities (including swimming, walking, and cycling) are the most popular [ 13 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Despite the general decline in sport participation with age [ 13 ], the most recent (pre-COVID) global data highlights that a range of organized team sports (such as, basketball, netball volleyball, and tennis) continue to rank highly amongst adult sport participants, with soccer remaining a popular choice across all regions of the world [ 13 ]. It is encouraging many adults continue to participate in sport and physical activities throughout their lives; however, high rates of dropout in youth sport and non-participation amongst adults means that many individuals may be missing the opportunity to reap the potential health benefits associated with participation in sport.

According to the World Health Organization, mental health refers to a state of well-being and effective functioning in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, is resilient to the stresses of life, and is able to make a positive contribution to his or her community [ 20 ]. Mental health covers three main components, including psychological, emotional and social health [ 21 ]. Further, psychological health has two distinct indicators, psychological well-being (e.g., self-esteem and quality of life) and psychological ill-being (e.g., pre-clinical psychological states such as psychological difficulties and high levels of stress) [ 22 ]. Emotional well-being describes how an individual feels about themselves (including life satisfaction, interest in life, loneliness, and happiness); and social well–being includes an individual’s contribution to, and integration in society [ 23 ].

Mental illnesses are common among adults and incidence rates have remained consistently high over the past 25 years (~ 10% of people affected globally) [ 24 ]. Recent statistics released by the World Health Organization indicate that depression and anxiety are the most common mental disorders, affecting an estimated 264 million people, ranking as one of the main causes of disability worldwide [ 25 , 26 ]. Specific elements of social health, including high levels of isolation and loneliness among adults, are now also considered a serious public health concern due to the strong connections with ill-health [ 27 ]. Participation in sport has shown to positively impact mental and social health status, with a previous systematic review by Eime et al. (2013) indicated that sports participation was associated with lower levels of perceived stress, and improved vitality, social functioning, mental health, and life satisfaction [ 1 ]. Based on their findings, the authors developed a conceptual model (health through sport) depicting the relationship between determinants of adult sports participation and physical, psychological, and social health benefits of participation. In support of Eime’s review findings, Malm and colleagues (2019) recently described how sport aids in preventing or alleviating mental illness, including depressive symptoms and anxiety or stress-related disease [ 7 ]. Andersen (2019) also highlighted that team sports participation is associated with decreased rates of depression and anxiety [ 11 ]. In general, these reviews report stronger effects for sports participation compared to other types of physical activity, and a dose–response relationship between sports participation and mental health outcomes (i.e., higher volume and/or intensity of participation being associated with greater health benefits) when adults participate in sports they enjoy and choose [ 1 , 7 ]. Sport is typically more social than other forms of physical activity, including enhanced social connectedness, social support, peer bonding, and club support, which may provide some explanation as to why sport appears to be especially beneficial to mental and social health [ 28 ].

Thoits (2011) proposed several potential mechanisms through which social relationships and social support improve physical and psychological well-being [ 29 ]; however, these mechanisms have yet to be explored in the context of sports participation at any level in adults. The identification of the mechanisms responsible for such effects may direct future research in this area and help inform future policy and practice in the delivery of sport to enhance mental health and social outcomes amongst adult participants. Therefore, the primary objective of this review was to examine and synthesize all research findings regarding the relationship between sports participation, mental health and social outcomes at the community and elite level in adults. Based on the review findings, the secondary objective was to develop the ‘Mental Health through Sport’ conceptual model.

This review has been registered in the PROSPERO systematic review database and assigned the identifier: CRD42020185412. The conduct and reporting of this systematic review also follows the Preferred Reporting for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 30 ] (PRISMA flow diagram and PRISMA Checklist available in supplementary files ). This review is an update of a previous review of the same topic [ 31 ], published in 2012.

Identification of studies

Nine electronic databases (CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, Informit, Medline, PsychINFO, Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, Scopus, and SPORTDiscus) were systematically searched for relevant records published from 2012 to March 10, 2020. The following key terms were developed by all members of the research team (and guided by previous reviews) and entered into these databases by author LW: sport* AND health AND value OR benefit* OR effect* OR outcome* OR impact* AND psych* OR depress* OR stress OR anxiety OR happiness OR mood OR ‘quality of life’ OR ‘social health’ OR ‘social relation*’ OR well* OR ‘social connect*’ OR ‘social functioning’ OR ‘life satisfac*’ OR ‘mental health’ OR social OR sociolog* OR affect* OR enjoy* OR fun. Where possible, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were also used.

Criteria for inclusion/exclusion

The titles of studies identified using this method were screened by LW. Abstract and full text of the articles were reviewed independently by LW and NE. To be included in the current review, each study needed to meet each of the following criteria: (1) published in English from 2012 to 2020; (2) full-text available online; (3) original research or report published in a peer-reviewed journal; (4) provides data on the psychological or social effects of participation in sport (with sport defined as a subset of exercise that can be undertaken individually or as a part of a team, where participants adhere to a common set of rules or expectations, and a defined goal exists); (5) the population of interest were adults (18 years and older) and were apparently healthy. All papers retrieved in the initial search were assessed for eligibility by title and abstract. In cases where a study could not be included or excluded via their title and abstract, the full text of the article was reviewed independently by two of the authors.

Data extraction

For the included studies, the following data was extracted independently by LW and checked by NE using a customized Google Docs spreadsheet: author name, year of publication, country, study design, aim, type of sport (e.g., tennis, hockey, team, individual), study conditions/comparisons, sample size, where participants were recruited from, mean age of participants, measure of sports participation, measure of physical activity, psychological and/or social outcome/s, measure of psychological and/or social outcome/s, statistical method of analysis, changes in physical activity or sports participation, and the psychological and/or social results.

Risk of bias (ROB) assessment

A risk of bias was performed by LW and AP independently using the ‘Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies’ OR the ‘Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies’ for the included quantitative studies, and the ‘Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Checklist for the included qualitative studies [ 32 , 33 ]. Any discrepancies in the ROB assessments were discussed between the two reviewers, and a consensus reached.

The search yielded 8528 studies, with a total of 29 studies included in the systematic review (Fig. 1 ). Tables 1 and 2 provide a summary of the included studies. The research included adults from 18 to 84 years old, with most of the evidence coming from studies targeting young adults (18–25 years). Study samples ranged from 14 to 131, 962, with the most reported psychological outcomes being self-rated mental health ( n = 5) and depression ( n = 5). Most studies did not investigate or report the link between a particular sport and a specific mental health or social outcome; instead, the authors’ focused on comparing the impact of sport to physical activity, and/or individual sports compared to team sports. The results of this review are summarized in the following section, with findings presented by study design (cross-sectional, experimental, and longitudinal).

Flow of studies through the review process

Effects of sports participation on psychological well-being, ill-being, and social outcomes

Cross-sectional evidence.

This review included 14 studies reporting on the cross-sectional relationship between sports participation and psychological and/or social outcomes. Sample sizes range from n = 414 to n = 131,962 with a total of n = 239,394 adults included across the cross-sectional studies.

The cross-sectional evidence generally supports that participation in sport, and especially team sports, is associated with greater mental health and psychological wellbeing in adults compared to non-participants [ 36 , 59 ]; and that higher frequency of sports participation and/or sport played at a higher level of competition, are also linked to lower levels of mental distress in adults . This was not the case for one specific study involving ice hockey players aged 35 and over, with Kitchen and Chowhan (2016) Kitchen and Chowhan (2016) reporting no relationship between participation in ice hockey and either mental health, or perceived life stress [ 54 ]. There is also some evidence to support that previous participation in sports (e.g., during childhood or young adulthood) is linked to better mental health outcomes later in life, including improved mental well-being and lower mental distress [ 59 ], even after controlling for age and current physical activity.

Compared to published community data for adults, elite or high-performance adult athletes demonstrated higher levels of body satisfaction, self-esteem, and overall life satisfaction [ 39 ]; and reported reduced tendency to respond to distress with anger and depression. However, rates of psychological distress were higher in the elite sport cohort (compared to community norms), with nearly 1 in 5 athletes reporting ‘high to very high’ distress, and 1 in 3 reporting poor mental health symptoms at a level warranting treatment by a health professional in one study ( n = 749) [ 39 ].

Four studies focused on the associations between physical activity and sports participation and mental health outcomes in older adults. Physical activity was associated with greater quality of life [ 56 ], with the relationship strongest for those participating in sport in middle age, and for those who cycled in later life (> 65) [ 56 ]. Group physical activities (e.g., walking groups) and sports (e.g., golf) were also significantly related to excellent self-rated health, low depressive symptoms, high health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and a high frequency of laughter in males and females [ 60 , 61 ]. No participation or irregular participation in sport was associated with symptoms of mild to severe depression in older adults [ 62 ].

Several cross-sectional studies examined whether the effects of physical activity varied by type (e.g., total physical activity vs. sports participation). In an analysis of 1446 young adults (mean age = 18), total physical activity, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, and team sport were independently associated with mental health [ 46 ]. Relative to individual physical activity, after adjusting for covariates and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), only team sport was significantly associated with improved mental health. Similarly, in a cross-sectional analysis of Australian women, Eime, Harvey, Payne (2014) reported that women who engaged in club and team-based sports (tennis or netball) reported better mental health and life satisfaction than those who engaged in individual types of physical activity [ 47 ]. Interestingly, there was no relationship between the amount of physical activity and either of these outcomes, suggesting that other qualities of sports participation contribute to its relationship to mental health and life satisfaction. There was also some evidence to support a relationship between exercise type (ball sports, aerobic activity, weightlifting, and dancing), and mental health amongst young adults (mean age 22 years) [ 48 ], with ball sports and dancing related to fewer symptoms of depression in students with high stress; and weightlifting related to fewer depressive symptoms in weightlifters exhibiting low stress.

Longitudinal evidence

Eight studies examined the longitudinal relationship between sports participation and either mental health and/or social outcomes. Sample sizes range from n = 113 to n = 1679 with a total of n = 7022 adults included across the longitudinal studies.

Five of the included longitudinal studies focused on the relationship between sports participation in childhood or adolescence and mental health in young adulthood. There is evidence that participation in sport in high-school is protective of future symptoms of anxiety (including panic disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, social phobia, and agoraphobia) [ 42 ]. Specifically, after controlling for covariates (including current physical activity), the number of years of sports participation in high school was shown to be protective of symptoms of panic and agoraphobia in young adulthood, but not protective of symptoms of social phobia or generalized anxiety disorder [ 42 ]. A comparison of individual or team sports participation also revealed that participation in either context was protective of panic disorder symptoms, while only team sport was protective of agoraphobia symptoms, and only individual sport was protective of social phobia symptoms. Furthermore, current and past sports team participation was shown to negatively relate to adult depressive symptoms [ 43 ]; drop out of sport was linked to higher depressive symptoms in adulthood compared to those with maintained participation [ 9 , 22 , 63 ]; and consistent participation in team sports (but not individual sport) in adolescence was linked to higher self-rated mental health, lower perceived stress and depressive symptoms, and lower depression scores in early adulthood [ 53 , 58 ].

Two longitudinal studies [ 35 , 55 ], also investigated the association between team and individual playing context and mental health. Dore and colleagues [ 35 ] reported that compared to individual activities, being active in informal groups (e.g., yoga, running groups) or team sports was associated with better mental health, fewer depressive symptoms and higher social connectedness – and that involvement in team sports was related to better mental health regardless of physical activity volume. Kim and James [ 55 ] discovered that sports participation led to both short and long-term improvements in positive affect and life satisfaction.

A study on social outcomes related to mixed martial-arts (MMA) and Brazilian jiu-jitsu (BJJ) showed that both sports improved practitioners’ self-control and pro-social behavior, with greater improvements seen in the BJJ group [ 62 ]. Notably, while BJJ reduced participants’ reported aggression, there was a slight increase in MMA practitioners, though it is worth mentioning that individuals who sought out MMA had higher levels of baseline aggression.

Experimental evidence

Six of the included studies were experimental or quasi-experimental. Sample sizes ranged from n = 28 to n = 55 with a total of n = 239 adults included across six longitudinal studies. Three studies involved a form of martial arts (such as judo and karate) [ 45 , 51 , 52 ], one involved a variety of team sports (such as netball, soccer, and cricket) [ 34 ], and the remaining two focused on badminton [ 57 ] and handball [ 49 ].

Brinkley and colleagues [ 34 ] reported significant effects on interpersonal communication (but not vitality, social cohesion, quality of life, stress, or interpersonal relationships) for participants ( n = 40) engaging in a 12-week workplace team sports intervention. Also using a 12-week intervention, Hornstrup et al. [ 49 ] reported a significant improvement in mental energy (but not well-being or anxiety) in young women (mean age = 24; n = 28) playing in a handball program. Patterns et al. [ 57 ] showed that in comparison to no exercise, participation in an 8-week badminton or running program had no significant improvement on self-esteem, despite improvements in perceived and actual fitness levels.

Three studies examined the effect of martial arts on the mental health of older adults (mean ages 79 [ 52 ], 64 [ 51 ], and 70 [ 45 ] years). Participation in Karate-Do had positive effects on overall mental health, emotional wellbeing, depression and anxiety when compared to other activities (physical, cognitive, mindfulness) and a control group [ 51 , 52 ]. Ciaccioni et al. [ 45 ] found that a Judo program did not affect either the participants’ mental health or their body satisfaction, citing a small sample size, and the limited length of the intervention as possible contributors to the findings.

Qualitative evidence

Three studies interviewed current or former sports players regarding their experiences with sport. Chinkov and Holt [ 41 ] reported that jiu-jitsu practitioners (mean age 35 years) were more self-confident in their lives outside of the gym, including improved self-confidence in their interactions with others because of their training. McGraw and colleagues [ 37 ] interviewed former and current National Football League (NFL) players and their families about its impact on the emotional and mental health of the players. Most of the players reported that their NFL career provided them with social and emotional benefits, as well as improvements to their self-esteem even after retiring. Though, despite these benefits, almost all the players experienced at least one mental health challenge during their career, including depression, anxiety, or difficulty controlling their temper. Some of the players and their families reported that they felt socially isolated from people outside of the national football league.

Through a series of semi-structured interviews and focus groups, Thorpe, Anders [ 40 ] investigated the impact of an Aboriginal male community sporting team on the health of its players. The players reported they felt a sense of belonging when playing in the team, further noting that the social and community aspects were as important as the physical health benefits. Participating in the club strengthened the cultural identity of the players, enhancing their well-being. The players further noted that participation provided them with enjoyment, stress relief, a sense of purpose, peer support, and improved self-esteem. Though they also noted challenges, including the presence of racism, community conflict, and peer-pressure.

Quality of studies

Full details of our risk of bias (ROB) results are provided in Supplementary Material A . Of the three qualitative studies assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP), all three were deemed to have utilised and reported appropriate methodological standards on at least 8 of the 10 criteria. Twenty studies were assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies, with all studies clearly reporting the research question/s or objective/s and study population. However, only four studies provided a justification for sample size, and less than half of the studies met quality criteria for items 6, 7, 9, or 10 (and items 12 and 13 were largely not applicable). Of concern, only four of the observational or cohort studies were deemed to have used clearly defined, valid, and reliable exposure measures (independent variables) and implemented them consistently across all study participants. Six studies were assessed using the Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies, with three studies described as a randomized trial (but none of the three reported a suitable method of randomization, concealment of treatment allocation, or blinding to treatment group assignment). Three studies showed evidence that study groups were similar at baseline for important characteristics and an overall drop-out rate from the study < 20%. Four studies reported high adherence to intervention protocols (with two not reporting) and five demonstrated that.study outcomes were assessed using valid and reliable measures and implemented consistently across all study participants. Importantly, researchers did not report or have access to validated instruments for assessing sport participation or physical activity amongst adults, though most studies provided psychometrics for their mental health outcome measure/s. Only one study reported that the sample size was sufficiently powered to detect a difference in the main outcome between groups (with ≥ 80% power) and that all participants were included in the analysis of results (intention-to-treat analysis). In general, the methodological quality of the six randomised studies was deemed low.

Initially, our discussion will focus on the review findings regarding sports participation and well-being, ill-being, and psychological health. However, the heterogeneity and methodological quality of the included research (especially controlled trials) should be considered during the interpretation of our results. Considering our findings, the Mental Health through Sport conceptual model for adults will then be presented and discussed and study limitations outlined.

Sports participation and psychological well-being

In summary, the evidence presented here indicates that for adults, sports participation is associated with better overall mental health [ 36 , 46 , 47 , 59 ], mood [ 56 ], higher life satisfaction [ 39 , 47 ], self-esteem [ 39 ], body satisfaction [ 39 ], HRQoL [ 60 ], self-rated health [ 61 ], and frequency of laughter [ 61 ]. Sports participation has also shown to be predictive of better psychological wellbeing over time [ 35 , 53 ], higher positive affect [ 55 ], and greater life satisfaction [ 55 ]. Furthermore, higher frequency of sports participation and/or sport played at a higher level of competition, have been linked to lower levels of mental distress, higher levels of body satisfaction, self-esteem, and overall life satisfaction in adults [ 39 ].

Despite considerable heterogeneity of sports type, cross-sectional and experimental research indicate that team-based sports participation, compared to individual sports and informal group physical activity, has a more positive effect on mental energy [ 49 ], physical self-perception [ 57 ], and overall psychological health and well-being in adults, regardless of physical activity volume [ 35 , 46 , 47 ]. And, karate-do benefits the subjective well-being of elderly practitioners [ 51 , 52 ]. Qualitative research in this area has queried participants’ experiences of jiu-jitsu, Australian football, and former and current American footballers. Participants in these sports reported that their participation was beneficial for psychological well-being [ 37 , 40 , 41 ], improved self-esteem [ 37 , 40 , 41 ], and enjoyment [ 37 ].

Sports participation and psychological ill-being

Of the included studies, n = 19 examined the relationship between participating in sport and psychological ill-being. In summary, there is consistent evidence that sports participation is related to lower depression scores [ 43 , 48 , 61 , 62 ]. There were mixed findings regarding psychological stress, where participation in childhood (retrospectively assessed) was related to lower stress in young adulthood [ 41 ], but no relationship was identified between recreational hockey in adulthood and stress [ 54 ]. Concerning the potential impact of competing at an elite level, there is evidence of higher stress in elite athletes compared to community norms [ 39 ]. Further, there is qualitative evidence that many current or former national football league players experienced at least one mental health challenge, including depression, anxiety, difficulty controlling their temper, during their career [ 37 ].

Evidence from longitudinal research provided consistent evidence that participating in sport in adolescence is protective of symptoms of depression in young adulthood [ 43 , 53 , 58 , 63 ], and further evidence that participating in young adulthood is related to lower depressive symptoms over time (6 months) [ 35 ]. Participation in adolescence was also protective of manifestations of anxiety (panic disorder and agoraphobia) and stress in young adulthood [ 42 ], though participation in young adulthood was not related to a more general measure of anxiety [ 35 ] nor to changes in negative affect [ 55 ]). The findings from experimental research were mixed. Two studies examined the effect of karate-do on markers of psychological ill-being, demonstrating its capacity to reduce anxiety [ 52 ], with some evidence of its effectiveness on depression [ 51 ]. The other studies examined small-sided team-based games but showed no effect on stress or anxiety [ 34 , 49 ]. Most studies did not differentiate between team and individual sports, though one study found that adolescents who participated in team sports (not individual sports) in secondary school has lower depression scores in young adulthood [ 58 ].

Sports participation and social outcomes

Seven of the included studies examined the relationship between sports participation and social outcomes. However, very few studies examined social outcomes or tested a social outcome as a potential mediator of the relationship between sport and mental health. It should also be noted that this body of evidence comes from a wide range of sport types, including martial arts, professional football, and workplace team-sport, as well as different methodologies. Taken as a whole, the evidence shows that participating in sport is beneficial for several social outcomes, including self-control [ 50 ], pro-social behavior [ 50 ], interpersonal communication [ 34 ], and fostering a sense of belonging [ 40 ]. Further, there is evidence that group activity, for example team sport or informal group activity, is related to higher social connectedness over time, though analyses showed that social connectedness was not a mediator for mental health [ 35 ].

There were conflicting findings regarding social effects at the elite level, with current and former NFL players reporting that they felt socially isolated during their career [ 37 ], whilst another study reported no relationship between participation at the elite level and social dysfunction [ 39 ]. Conversely, interviews with a group of indigenous men revealed that they felt as though participating in an all-indigenous Australian football team provided them with a sense of purpose, and they felt as though the social aspect of the game was as important as the physical benefits it provides [ 40 ].

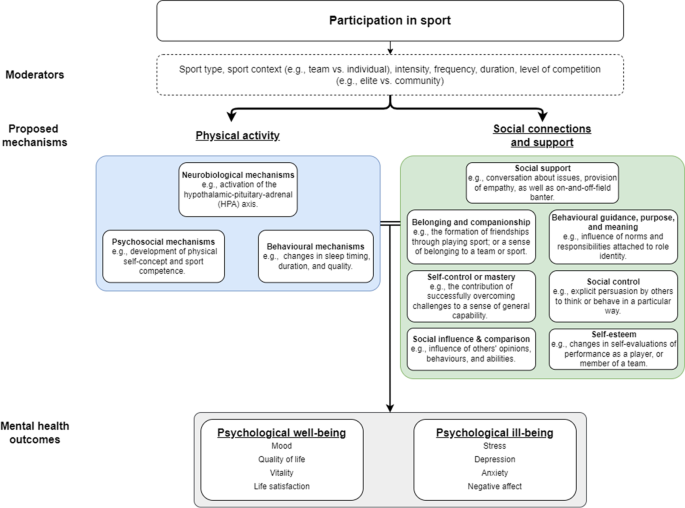

Mental health through sport conceptual model for adults

The ‘Health through Sport’ model provides a depiction of the determinants and benefits of sports participation [ 31 ]. The model recognises that the physical, mental, and social benefits of sports participation vary by the context of sport (e.g., individual vs. team, organized vs. informal). To identify the elements of sport which contribute to its effect on mental health outcomes, we describe the ‘Mental Health through Sport’ model (Fig. 2 ). The model proposes that the social and physical elements of sport each provide independent, and likely synergistic contributions to its overall influence on mental health.

The Mental Health through Sport conceptual model

The model describes two key pathways through which sport may influence mental health: physical activity, and social relationships and support. Several likely moderators of this effect are also provided, including sport type, intensity, frequency, context (team vs. individual), environment (e.g., indoor vs. outdoor), as well as the level of competition (e.g., elite vs. amateur).

The means by which the physical activity component of sport may influence mental health stems from the work of Lubans et al., who propose three key groups of mechanisms: neurobiological, psychosocial, and behavioral [ 64 ]. Processes whereby physical activity may enhance psychological outcomes via changes in the structural and functional composition of the brain are referred to as neurobiological mechanisms [ 65 , 66 ]. Processes whereby physical activity provides opportunities for the development of self-efficacy, opportunity for mastery, changes in self-perceptions, the development of independence, and for interaction with the environment are considered psychosocial mechanisms. Lastly, processes by which physical activity may influence behaviors which ultimately affect psychological health, including changes in sleep duration, self-regulation, and coping skills, are described as behavioral mechanisms.

Playing sport offers the opportunity to form relationships and to develop a social support network, both of which are likely to influence mental health. Thoits [ 29 ] describes 7 key mechanisms by which social relationships and support may influence mental health: social influence/social comparison; social control; role-based purpose and meaning (mattering); self-esteem; sense of control; belonging and companionship; and perceived support availability [ 29 ]. These mechanisms and their presence within a sporting context are elaborated below.

Subjective to the attitudes and behaviors of individuals in a group, social influence and comparison may facilitate protective or harmful effects on mental health. Participants in individual or team sport will be influenced and perhaps steered by the behaviors, expectations, and norms of other players and teams. When individual’s compare their capabilities, attitudes, and values to those of other participants, their own behaviors and subsequent health outcomes may be affected. When others attempt to encourage or discourage an individual to adopt or reject certain health practices, social control is displayed [ 29 ]. This may evolve as strategies between players (or between players and coach) are discussion and implemented. Likewise, teammates may try to motivate each another during a match to work harder, or to engage in specific events or routines off-field (fitness programs, after game celebrations, attending club events) which may impact current and future physical and mental health.

Sport may also provide behavioral guidance, purpose, and meaning to its participants. Role identities (positions within a social structure that come with reciprocal obligations), often formed as a consequence of social ties formed through sport. Particularly in team sports, participants come to understand they form an integral part of the larger whole, and consequently, they hold certain responsibility in ensuring the team’s success. They have a commitment to the team to, train and play, communicate with the team and a potential responsibility to maintain a high level of health, perform to their capacity, and support other players. As a source of behavioral guidance and of purpose and meaning in life, these identities are likely to influence mental health outcomes amongst sport participants.

An individual’s level of self-esteem may be affected by the social relationships and social support provided through sport; with improved perceptions of capability (or value within a team) in the sporting domain likely to have positive impact on global self-esteem and sense of worth [ 64 ]. The unique opportunities provided through participation in sport, also allow individuals to develop new skills, overcome challenges, and develop their sense of self-control or mastery . Working towards and finding creative solutions to challenges in sport facilitates a sense of mastery in participants. This sense of mastery may translate to other areas of life, with individual’s developing the confidence to cope with varied life challenges. For example, developing a sense of mastery regarding capacity to formulate new / creative solutions when taking on an opponent in sport may result in greater confidence to be creative at work. Social relationships and social support provided through sport may also provide participants with a source of belonging and companionship. The development of connections (on and off the field) to others who share common interests, can build a sense of belonging that may mediate improvements in mental health outcomes. Social support is often provided emotionally during expressions of trust and care; instrumentally via tangible assistance; through information such as advice and suggestions; or as appraisal such feedback. All forms of social support provided on and off the field contribute to a more generalised sense of perceived support that may mediate the effect of social interaction on mental health outcomes.

Participation in sport may influence mental health via some combination of the social mechanisms identified by Thoits, and the neurobiological, psychosocial, and behavioral mechanisms stemming from physical activity identified by Lubans [ 29 , 64 ]. The exact mechanisms through which sport may confer psychological benefit is likely to vary between sports, as each sport varies in its physical and social requirements. One must also consider the social effects of sports participation both on and off the field. For instance, membership of a sporting team and/or club may provide a sense of identity and belonging—an effect that persists beyond the immediacy of playing the sport and may have a persistent effect on their psychological health. Furthermore, the potential for team-based activity to provide additional benefit to psychological outcomes may not just be attributable to the differences in social interactions, there are also physiological differences in the requirements for sport both within (team vs. team) and between (team vs. individual) categories that may elicit additional improvements in psychological outcomes. For example, evidence supports that exercise intensity moderates the relationship between physical activity and several psychological outcomes—supporting that sports performed at higher intensity will be more beneficial for psychological health.

Limitations and recommendations

There are several limitations of this review worthy of consideration. Firstly, amongst the included studies there was considerable heterogeneity in study outcomes and study methodology, and self-selection bias (especially in non-experimental studies) is likely to influence study findings and reduce the likelihood that study participants and results are representative of the overall population. Secondly, the predominately observational evidence included in this and Eime’s prior review enabled us to identify the positive relationship between sports participation and social and psychological health (and examine directionality)—but more experimental and longitudinal research is required to determine causality and explore potential mechanisms responsible for the effect of sports participation on participant outcomes. Additional qualitative work would also help researchers gain a better understanding of the relationship between specific elements of the sporting environment and mental health and social outcomes in adult participants. Thirdly, there were no studies identified in the literature where sports participation involved animals (such as equestrian sports) or guns (such as shooting sports). Such studies may present novel and important variables in the assessment of mental health benefits for participants when compared to non-participants or participants in sports not involving animals/guns—further research is needed in this area. Our proposed conceptual model also identifies several pathways through which sport may lead to improvements in mental health—but excludes some potentially negative influences (such as poor coaching behaviors and injury). And our model is not designed to capture all possible mechanisms, creating the likelihood that other mechanisms exist but are not included in this review. Additionally, an interrelationship exits between physical activity, mental health, and social relationships, whereby changes in one area may facilitate changes in the other/s; but for the purpose of this study, we have focused on how the physical and social elements of sport may mediate improvements in psychological outcomes. Consequently, our conceptual model is not all-encompassing, but designed to inform and guide future research investigating the impact of sport participation on mental health.

The findings of this review endorse that participation in sport is beneficial for psychological well-being, indicators of psychological ill-being, and social outcomes in adults. Furthermore, participation in team sports is associated with better psychological and social outcomes compared to individual sports or other physical activities. Our findings support and add to previous review findings [ 1 ]; and have informed the development of our ‘Mental Health through Sport’ conceptual model for adults which presents the potential mechanisms by which participation in sport may affect mental health.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, Charity MJ, Payne WR. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for adults: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:135.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ishihara T, Nakajima T, Yamatsu K, Okita K, Sagawa M, Morita N. Relationship of participation in specific sports to academic performance in adolescents: a 2-year longitudinal study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2020.

Cope E, Bailey R, Pearce G. Why do children take part in, and remain involved in sport?: implications for children’s sport coaches. Int J Coach Sci. 2013;7:55–74.

Google Scholar

Harrison PA, Narayan G. Differences in behavior, psychological factors, and environmental factors associated with participation in school sports and other activities in adolescence. J Sch Health. 2003;73(3):113–20.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Allender S, Cowburn G, Foster C. Understanding particpation in sport and physical activity among children and adults: a review of qualitative studies. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(6):826–35.

Adachi P, Willoughby T. It’s not how much you play, but how much you enjoy the game: The longitudinal associations between adolescents’ self-esteem and the frequency versus enjoyment of involvement in sports. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43(1):137–45.

Malm C, Jakobsson J, Isaksson A. Physical activity and sports-real health benefits: a review with insight into the public health of Sweden. Sports (Basel, Switzerland). 2019;7(5):127.

PubMed Google Scholar

Mills K, Dudley D, Collins NJ. Do the benefits of participation in sport and exercise outweigh the negatives? An academic review. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2019;33(1):172–87.

Howie EK, Guagliano JM, Milton K, Vella SA, Gomersall SR,Kolbe-Alexander TL, et al. Ten research priorities related to youth sport, physical activity, and health. 2020;17(9):920.

Vella SA, Swann C, Allen MS, Schweickle MJ, Magee CA. Bidirectional associations between sport involvement and mental health in adolescence. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(4):687–94.

Andersen MH, Ottesen L, Thing LF. The social and psychological health outcomes of team sport participation in adults: An integrative review of research. Scand J Public Health. 2019;47(8):832–50.

Rice SM, Purcell R, De Silva S, Mawren D, McGorry PD, Parker AG. The mental health of elite athletes: a narrative systematic review. Sports medicine (Auckland, NZ). 2016;46(9):1333–53.

Article Google Scholar

Hulteen RM, Smith JJ, Morgan PJ, Barnett LM, Hallal PC, Colyvas K, et al. Global participation in sport and leisure-time physical activities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2017;95:14–25.

Eime RM, Harvey J, Charity M, Westerbeek H. Longitudinal Trends in Sport Participation and Retention of Women and Girls. Front Sports Act Living. 2020;2:39.

Brooke HL, Corder K, Griffin SJ, van Sluijs EMF. Physical activity maintenance in the transition to adolescence: a longitudinal study of the roles of sport and lifestyle activities in british youth. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2): e89028.

Coll CVN, Knuth AG, Bastos JP, Hallal PC, Bertoldi AD. Time trends of physical activity among Brazilian adolescents over a 7-year period. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:209–13.

Klostermann C, Nagel S. Changes in German sport participation: Historical trends in individual sports. Int Rev Sociol Sport. 2012;49:609–34.

Eime RM, Harvey J, Charity M. Sport participation settings: where and “how” do Australians play sport? BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1344.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lim SY, Warner S, Dixon M, Berg B, Kim C, Newhouse-Bailey M. Sport Participation Across National Contexts: A Multilevel Investigation of Individual and Systemic Influences on Adult Sport Participation. Eur Sport Manag Q. 2011;11(3):197–224.

World Health Organisation. Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020. Geneva: World Health Orgnaisation; 2013.

Keyes C. Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health. Netherlands: Springer Dordrecht; 2014.

Ryff C, Love G, Urry H, Muller D, Rosenkranz M, Friedman E, et al. Psychological well-being and ill-being: Do they have distinct or mirrored biological correlates? Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75:85–95.

Australian Government. Social and emotional wellbeing: Development of a children’s headline indicator information paper. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2013.

Global Burden of Disease Injury IP. Collaborators, Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858.

World Health Organisation. Mental disorders: Fact sheet 2019 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders .

Mental Health [Internet]. 2018 [cited 12 March 2021]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health ' [Online Resource].

Newman MG, Zainal NH. The value of maintaining social connections for mental health in older people. The Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(1):e12–3.

Eime RM, Harvey JT, Brown WJ, Payne WR. Does sports club participation contribute to health-related quality of life? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(5):1022–8.

Thoits PA. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J Health Soc Behav. 2011;52(2):145–61.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021;18(3): e1003583.

Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, Charity MJ, Payne WR. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for adults: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10(1):135.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist2019 1/12/2021]. Available from: https://casp-uk.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf .

National Institutes from Health. Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies 2014 [Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools .

Brinkley A, McDermott H, Grenfell-Essam R. It’s time to start changing the game: a 12-week workplace team sport intervention study. Sports Med Open. 2017;3(1):30–41.

Doré I, O’Loughlin JL, Schnitzer ME, Datta GD, Fournier L. The longitudinal association between the context of physical activity and mental health in early adulthood. Ment Health Phys Act. 2018;14:121–30.

Marlier M, Van Dyck D, Cardon G, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Babiak K, Willem A. Interrelation of sport participation, physical activity, social capital and mental health in disadvantaged communities: A sem-analysis. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2015; 10(10):[e0140196 p.]. Available from: http://ezproxy.newcastle.edu.au/login?url=http://ezproxy.newcastle.edu.au/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med12&AN=26451731 .

McGraw SA, Deubert CR, Lynch HF, Nozzolillo A, Taylor L, Cohen I. Life on an emotional roller coaster: NFL players and their family members’ perspectives on player mental health. J Clin Sport Psychol. 2018;12(3):404–31.

Mickelsson T. Modern unexplored martial arts – what can mixed martial arts and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu do for youth development?. Eur J Sport Sci. 2020;20(3):386–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2019.1629180 .

Purcell R, Rice S, Butterworth M, Clements M. Rates and Correlates of Mental Health Symptoms in Currently Competing Elite Athletes from the Australian National High-Performance Sports System. Sports Med. 2020.

Thorpe A, Anders W, Rowley K. The community network: an Aboriginal community football club bringing people together. Aust J Prim Health. 2014;20(4):356–64.

Appelqvist-Schmidlechner K, Vaara J, Hakkinen A, Vasankari T, Makinen J, Mantysaari M, et al. Relationships between youth sports participation and mental health in young adulthood among Finnish males. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(7):1502–9.

Ashdown-Franks G, Sabiston CM, Solomon-Krakus S, O’Loughlin JL. Sport participation in high school and anxiety symptoms in young adulthood. Ment Health Phys Act. 2017;12:19–24.

Brunet J, Sabiston CM, Chaiton M, Barnett TA, O’Loughlin E, Low NC, et al. The association between past and current physical activity and depressive symptoms in young adults: a 10-year prospective study. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23(1):25–30.

Chinkov AE, Holt NL. Implicit transfer of life skills through participation in Brazilian Jiu-jitsu. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2016;28(2):139–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2015.1086447 .

Ciaccioni S, Capranica L, Forte R, Chaabene H, Pesce C, Condello G. Effects of a judo training on functional fitness, anthropometric, and psychological variables in old novice practitioners. J Aging Phys Act. 2019;27(6):831–42.

Doré I, O’Loughlin JL, Beauchamp G, Martineau M, Fournier L. Volume and social context of physical activity in association with mental health, anxiety and depression among youth. Prev Med. 2016;91:344–50.

Eime R, Harvey J, Payne W. Dose-response of women’s health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and life satisfaction to physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 2014;11(2):330–8.

Gerber M, Brand S, Elliot C, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Pühse U. Aerobic exercise, ball sports, dancing, and weight Lifting as moderators of the relationship between Stress and depressive symptoms: an exploratory cross-sectional study with Swiss university students. Percept Mot Skills. 2014;119(3):679–97.

Hornstrup T, Wikman JM, Fristrup B, Póvoas S, Helge EW, Nielsen SH, et al. Fitness and health benefits of team handball training for young untrained women—a cross-disciplinary RCT on physiological adaptations and motivational aspects. J Sport Health Sci. 2018;7(2):139–48.

Mickelsson T. Modern unexplored martial arts–what can mixed martial arts and Brazilian Jiu-Jiutsu do for youth development? Eur J Sport Sci. 2019.

Jansen P, Dahmen-Zimmer K. Effects of cognitive, motor, and karate training on cognitive functioning and emotional well-being of elderly people. Front Psychol. 2012;3:40.

Jansen P, Dahmen-Zimmer K, Kudielka BM, Schulz A. Effects of karate training versus mindfulness training on emotional well-being and cognitive performance in later life. Res Aging. 2017;39(10):1118–44.

Jewett R, Sabiston CM, Brunet J, O’Loughlin EK, Scarapicchia T, O’Loughlin J. School sport participation during adolescence and mental health in early adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(5):640–4.

Kitchen P, Chowhan J. Forecheck, backcheck, health check: the benefits of playing recreational ice hockey for adults in Canada. J Sports Sci. 2016;34(21):2121–9.

Kim J, James JD. Sport and happiness: Understanding the relations among sport consumption activities, long-and short-term subjective well-being, and psychological need fulfillment. J Sport Manage. 2019.

Koolhaas CH, Dhana K, Van Rooij FJA, Schoufour JD, Hofman A, Franco OH. Physical activity types and health-related quality of life among middle-aged and elderly adults: the Rotterdam study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22(2):246–53.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Patterson S, Pattison J, Legg H, Gibson AM, Brown N. The impact of badminton on health markers in untrained females. J Sports Sci. 2017;35(11):1098–106.

Sabiston CM, Jewett R, Ashdown-Franks G, Belanger M, Brunet J, O’Loughlin E, et al. Number of years of team and individual sport participation during adolescence and depressive symptoms in early adulthood. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2016;38(1):105–10.

Sorenson SC, Romano R, Scholefield RM, Martin BE, Gordon JE, Azen SP, et al. Holistic life-span health outcomes among elite intercollegiate student-athletes. J Athl Train. 2014;49(5):684–95.

Stenner B, Mosewich AD, Buckley JD, Buckley ES. Associations between markers of health and playing golf in an Australian population. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2019;5(1).

Tsuji T, Kanamori S, Saito M, Watanabe R, Miyaguni Y, Kondo K. Specific types of sports and exercise group participation and socio-psychological health in older people. J Sports Sci. 2020;38(4):422–9.

Yamakita M, Kanamori S, Kondo N, Kondo K. Correlates of regular participation in sports groups among Japanese older adults: JAGES cross–sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10):e0141638.

Howie EK, McVeigh JA, Smith AJ, Straker LM. Organized sport trajectories from childhood to adolescence and health associations. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(7):1331–9.

Chinkov AE, Holt NL. Implicit transfer of life skills through participation in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2016;28(2):139–53.

Lubans D, Richards J, Hillman C, Faulkner G, Beauchamp M, Nilsson M, et al. Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: a systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161642.

Lin TW, Kuo YM. Exercise benefits brain function: the monoamine connection. Brain Sci. 2013;3(1):39–53.

Dishman RK, O’Connor PJ. Lessons in exercise neurobiology: the case of endorphins. Ment Health Phys Act. 2009;2(1):4–9.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the work of the original systematic review conducted by Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J., and Payne, W. R. (2013).

No funding associated with this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Active Living and Learning, University of Newcastle, University Drive, Callaghan, NSW, 2308, Australia

Narelle Eather & Levi Wade

College of Human and Social Futures, School of Education, University of Newcastle, University Drive, Callaghan, NSW, 2308, Australia

Narelle Eather

College of Health, Medicine, and Wellbeing, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, University Drive, Callaghan, NSW, 2308, Australia

Institute for Health and Sport, Victoria University, Ballarat Road, Footscray, VIC, 3011, Australia

Aurélie Pankowiak & Rochelle Eime

School of Science, Psychology and Sport, Federation University Australia, University Drive, Mount Helen, VIC, 3350, Australia

Rochelle Eime

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conducting of this study and reporting the findings. The titles of studies identified were screened by LW, and abstracts and full text articles reviewed independently by LW and NE. For the included studies, data was extracted independently by LW and checked by NE, and the risk of bias assessment was performed by LW and AP independently. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Narelle Eather .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: supplementary table a..

Risk of bias.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table B.

PRISMA Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Eather, N., Wade, L., Pankowiak, A. et al. The impact of sports participation on mental health and social outcomes in adults: a systematic review and the ‘Mental Health through Sport’ conceptual model. Syst Rev 12 , 102 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-023-02264-8

Download citation

Received : 30 August 2021

Accepted : 31 May 2023

Published : 21 June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-023-02264-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Experimental

- Observational

- Psychological health

- Mental health

- Social health

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine