Cognitive Approach to Psychology: Definition and Examples

Categories Cognition

Sharing is caring!

The cognitive approach to psychology focuses on internal mental processes. Such processes include thinking, decision-making, problem-solving , language, attention, and memory. The cognitive approach in psychology is often considered part of the larger field of cognitive science. This branch of psychology is also related to several other disciplines, including neuroscience, philosophy, and linguistics.

The core focus of the cognitive approach to psychology is on how people acquire, process, and store information. Cognitive psychologists are interested in studying what happens inside people’s minds.

Table of Contents

What Is the Cognitive Approach to Psychology?

While the cognitive approach to psychology is a popular branch of psychology today, it is actually a relatively young field of study. Until the 1950s, behaviorism was the dominant school of thought in psychology.

Between 1950 and 1970, the tide began to shift against behavioral psychology to focus on topics such as attention, memory, and problem-solving.

Often referred to as the cognitive revolution, this period generated considerable research on subjects, including processing models, cognitive research methods , and the first use of the term “cognitive psychology.”

The term “cognitive psychology” was first used in 1967 by American psychologist Ulric Neisser in his book Cognitive Psychology . According to Neisser, cognition involves “all processes by which the sensory input is transformed, reduced, elaborated, stored, recovered, and used.” Neisser also suggested that given such a broad and sweeping definition, cognition was involved in anything and everything that people do.

Essentially, all psychological events are cognitive events. Today, the American Psychological Association defines cognitive psychology as the “study of higher mental processes such as attention, language use, memory, perception, problem solving, and thinking.”

Understanding the Emergence of the Cognitive Approach

Some factors that contributed to the rise of the cognitive approach to psychology. These include:

- Dissatisfaction with the behaviorist approach : Behaviorism largely focused on looking at external influences on behavior. What the behavioral perspective failed to account for was the internal processes that influence human behavior. The cognitive approached emerged to fill this void.

- The increased use of computers : Scientists began comparing the way the human mind works to how a computer stores information on a hard drive. The information-processing model became popular as a result.

Thanks to these influences, the cognitive approach became an increasingly important branch of psychology. Behaviorism lost its hold as a dominant perspective, and psychologists began to look more intensely at memory, learning, language, and other internal processes.

Research Methods Used in the Cognitive Approach

Psychologists who use the cognitive approach rely on rigorous scientific methods to research the human mind. In many cases, this involves using experiments to determine if changes in an independent variable result in changes in the dependent variable.

Some of the main research methods used in the cognitive approach include:

Experimental Research

This involves conducting controlled experiments to manipulate variables and observe their effects on cognitive processes. Experiments are often conducted in laboratory settings to maintain control over extraneous variables.

For example, a memory experiment might involve randomly assigning participants to take a series of memory tests to determine if a certain change in conditions led to changes in memory abilities.

By using rigorous empirical methods, psychologists can accurately determine that it is the independent variable causing the changes rather than some other factor.

Cognitive Neuropsychology

This approach studies cognitive function by examining individuals with brain injuries or neurological disorders. By observing how damage to specific brain areas affects cognitive processes, researchers can infer the functions of those areas.

Neuroimaging Techniques

Cognitive neuroscientists use techniques to examine brain activity during cognitive tasks. Some of these neuroimaging tools include:

- Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)

- Positron emission tomography (PET)

- Electroencephalography (EEG)

Eye-Tracking Studies

Eye-tracking technology is used to study visual attention and perception by recording eye movements as participants view stimuli. This method provides insights into how people process visual information and allocate attention.

Areas of Study in the Cognitive Approach

As mentioned previously, any mental event is considered a cognitive event. There are a number of larger topics that have held the interest of cognitive psychologists over the last few decades. These include:

Information-Processing

As you might imagine, studying what’s happening in a person’s thoughts is not always the easiest thing to do.

Very early in psychology’s history, Wilhelm Wundt attempted to use a process known as introspection to study what was happening inside a person’s mind. This involved training people to focus on their internal states and write down what they were feeling, thinking, or experiencing. This approach was extremely subjective, so it did not last long as a cognitive research tool.

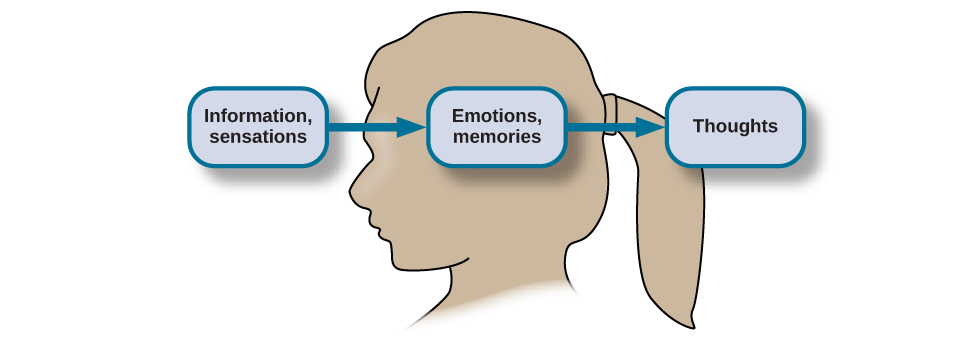

Cognitive psychologists have developed different models of thinking to study the human mind. One of the most popular of these is the information-processing approach .

In this approach, the mind is thought of as a computer. Thoughts and memories are broken down into smaller units of knowledge. As information enters the mind through the senses, it is manipulated by the brain, which then determines what to do with it.

Some information triggers an immediate response. Other units of information are transferred into long-term memory for future use.

Units of Knowledge

Cognitive psychologists often break down the units of knowledge into three different types: concepts, prototypes, and schemas.

A concept is basically a larger category of knowledge. A broad category exists inside your mind for these concepts where similar items are grouped together. You have concepts for things that are concrete such as a dog or cat, as well as concepts for abstract ideas such as beauty, gravity, and love.

A prototype refers to the most recognizable example of a particular concept. For example, what comes to mind when you think of a chair. If a large, comfy recliner immediately springs to mind, that is your prototype for the concept of a chair. If a bench, office chair, or bar stool pops into your mind, then that would be your prototype for that concept.

A schema is a mental framework you utilize to make sense of the world around you. Concepts are essentially the building blocks that are used to construct schemas, which are mental models for what you expect from the world around you. You have schemas for a wide variety of objects, ideas, people, and situations.

So what happens when you come across information that does not fit into one of your existing schemas? In some cases, you might even encounter things in the world that challenges or completely upend the ideas you already hold.

When this happens, you can either assimilate or accommodate the information. Assimilating the information involves broadening your current schema or even creating a new one. Accommodating the information requires changing your previously held ideas altogether. This process allows you to learn new things and develop new and more complex schemas for the world around you.

The Cognitive Approach to Attention

Attention is another major topic studied in the field of cognitive psychology. Attention is a state of focused awareness of some aspect of the environment. This ability to focus your attention allows you to take in knowledge about relevant stimuli in the world around you while at the same time filtering out things that are not particularly important.

At any given moment in time, you are taking in an immense amount of information from your visual, auditory, olfactory, tactile, and taste senses. Because the human brain has a limited capacity for handling all of this information, attention is both limited and selective.

Your attentional processes allow you to focus on the things that are relevant and essential for your survival while filtering out extraneous details.

The Cognitive Approach to Memory

How people form, recall, and retain memories is another important focus in the cognitive approach. The two major types of memory that researchers tend to look at are known as short-term memory and long-term memory.

Short-Term Memory

Short-term memories are all the things that you are actively thinking about and aware of at any given moment. This type of memory is both limited and very brief.

Estimates suggest that you can probably hold anywhere from 5 to 9 items in short-term memory for approximately 20 to 30 seconds.

Long-Term Memory

If this information is actively rehearsed and attended to, it may be transferred to what is known as long-term memory. As the name suggests, this type of memory is much more durable. While these longer-lasting memories are still susceptible to forgetting , the information retained in your long-term memory can last anywhere from days to decades.

Cognitive psychologists are interested in the various processes that influence how memories are formed, stored, and later retrieved. They also look at things that might interfere with the formation and storage of memories as well as various factors that might lead to memory errors or even false memories.

The Cognitive Approach to Intelligence

Human intelligence is also a major topic of interest within cognitive psychology, but it is also one of the most hotly debated and sometimes controversial. Not only has there been considerable questioning over how intelligence is measured (or if it can even be measured), but experts also disagree on exactly how to define intelligence itself.

One survey of psychologists found that experts provided more than 70 different definitions of what made up intelligence. While exact definitions vary, many agree that two important themes include both the ability to learn and the capacity to adapt as a result of experience.

Researchers have found that more intelligent people tend to perform better on tasks that require working memory , problem-solving, selective attention , concept formation, and decision-making. When looking at intelligence, cognitive psychologists often focus on understanding the mental processes that underlie these critical abilities.

Cognitive Development

Cognitive development refers to the changes in cognitive abilities that occur over the lifespan, from infancy through old age. Cognitive psychologists study the development of perception, attention, memory, language, and reasoning skills.

Research in cognitive development explores factors that influence cognitive growth, such as genetics, environment, and social interactions.

Language is a complex cognitive ability that enables communication through the use of symbols and grammatical rules. Cognitive psychologists study the cognitive processes involved in language comprehension, production, and acquisition.

Research in language examines topics such as syntax, semantics, pragmatics, and the neurobiological basis of language processing.

Reasons to Study the Cognitive Approach

Because cognitive psychology touches on many other disciplines, this branch of psychology is frequently studied by people in different fields. Even if you are not a psychology student, learning some of the basics of cognitive psychology can be helpful.

The following are just a few of those who may benefit from studying cognitive psychology.

- Students interested in behavioral neuroscience, linguistics, industrial-organizational psychology, artificial intelligence, and other related areas.

- Teachers, curriculum designers, instructional developers, and other educators may find it helpful to learn more about how people process, learn, and remember information.

- Engineers, scientists, artists, architects, and designers can all benefit from understanding internal mental states and processes.

Key Points to Remember About Cognitive Approach

- The cognitive approach emerged during the 1960s and 70s and has become a major force in the field of psychology.

- Cognitive psychologists are interested in mental processes, including how people take in, store, and utilize information.

- The cognitive approach to psychology often relies on an information-processing model that likens the human mind to a computer.

- Findings from the field of cognitive psychology apply in many areas, including our understanding of learning, memory, moral development, attention, decision-making, problem-solving, perceptions, and therapy approaches such as cognitive-behavior therapy and rational emotive behavior therapy.

Airenti G. (2019). The place of development in the history of psychology and cognitive science . Frontiers in Psychology , 10 , 895. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00895

Legg S, Hutter M. A collection of definitions of intelligence. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications . 2007;157:17-24.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical n u mber seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information . Psychological Review, 63 (2), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0043158

Neisser U. Cognitive Psychology . Meredith Publishing Company; 1967.

Image: Julia Freeman-Woolpert / freeimages.com

What Is Cognitive Development? 3 Psychology Theories

But don’t worry, we will try our best to help you with the essentials of this complex field of study.

We’ll start with some background, then show you how cognitive skills are used every day. In addition, we will explain a few theories and describe fascinating studies.

Since cognitive development goes beyond childhood and into adolescence, we are sure you will want to know all about this, too.

To end this article, we provide some helpful resources. You can use these to support the cognitive skills of your students or clients.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What is cognitive development in psychology, cognitive development skills & important milestones, 5 real-life examples of cognitive development, 3 ground-breaking cognitive development theories, a look at cognitive development in adolescence, 3 fascinating research studies, helpful resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

Cognitive development is how humans acquire, organize, and learn to use knowledge (Gauvain & Richert, 2016).

In psychology, the focus of cognitive development has often been only on childhood. However, cognitive development continues through adolescence and adulthood. It involves acquiring language and knowledge, thinking, memory, decision making, problem solving, and exploration (Von Eckardt, 1996).

Much of the research within cognitive development in children focuses on thinking, developing knowledge, exploring, and solving problems (Carpendale & Lewis, 2015).

Nature vs nurture debate

The nature versus nurture debate refers to how much an individual inherits compared to how much they are influenced by the environment. How do nature and nurture shape cognitive development?

American psychologist Arthur Jensen (1969, 1974) emphasized the role of genetics within intelligence, arguing for a genetic difference in the intelligence of white and Black people.

Jensen (1969) made some very bold assertions, stating that Black people have lower cognitive abilities. His research was heavily criticized for being discriminatory. He did not consider the inbuilt bias of psychometric testing (Ford, 1996). The lower test scores of Black individuals were more likely to be a result of a lack of resources and poor-quality life opportunities (Ford, 2004).

In an enormous cross-sample of 11,000 adolescent twins, Brant et al. (2013) found that those with a higher intelligence quotient (IQ) appeared to be more influenced by nurture and stimulation. The researchers suggested this may be because of their heightened attention and arousal system, absorbing more information from the environment, being more open to new experiences, and allowing brain plasticity and changes to occur.

They also found that adolescents with a lower IQ showed more genetic influence on their IQ from their parents. The researchers suggested that their lower levels of intelligence may result in lower motivation levels and an inability to seek out new experiences.

This study highlights the need for those with lower IQ levels to be supported with positive interventions to increase their cognitive abilities and capacity.

These milestones reflect skill achievement and take into account genetic makeup and environmental influence (Dosman, Andrews, & Goulden, 2012).

Here are a few of these important milestones, the associated skills, and the age at which they are typically achieved. The following table is modified from the Child Development Institute .

Table 1. Children’s cognitive milestones and skill development

Language and other cognitive skills

Language skills are essential for a child’s ability to communicate and engage with others. These skills support other areas of a child’s development, such as cognitive, literacy, and social development (Roulstone, Loader, Northstone, & Beveridge, 2002).

The modified table below was sourced from the Australian parenting website raisingchildren.net.au and describes how language develops in children.

Table 2. Language development from 0 to 8 years

Thinking skills

Thinking concerns manipulating information and is related to reasoning, decision making, and problem solving (Kashyap & Minda, 2016). It is required to develop language, because you need words to think.

Cognitive development activities helps thinking and reasoning to grow. Thinking is a skill that does not commence at birth. It develops gradually through childhood and advances more rapidly when children are around two years old. Reasoning develops around six. By the time they’re 11, children’s thinking becomes much more abstract and logical (Piaget, 1936).

Developing knowledge

Knowledge is essential for cognitive development and academic achievement. Increased knowledge equates to better speaking, reading, listening, and reasoning skills. Knowledge is not only related to language. It can also be gained by performing a task (Bhatt, 2000). It starts from birth as children begin to understand the world around them through their senses (Piaget, 1951).

Building knowledge is important for children to encode and retrieve new information. This makes them able to learn new material. Knowledge helps to facilitate critical thinking (Piaget, 1936). Clearly, the development of children’s knowledge base is a critical part of cognitive development.

Memory development

The development of memory is lifelong and related to personal experiences.

Explicit memory, which refers to remembering events and facts of everyday life, develops in the first two years (Stark, Yassa, & Stark, 2010). Explicit memory develops around 8 to 10 months.

Working memory and its increase in performance can be seen from three to four years through adolescence (Ward, Berry, & Shanks, 2013). This is demonstrated through increased attention, the acquisition of language, and increased knowledge.

Implicit memory, which is unconscious and unintentional, is an early developing memory system in infants and develops as the brain matures (Ward et al., 2013).

Perceptual skills

Perceptual skills develop from birth. They are an important aspect of cognitive development. Most children are born with senses of sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell (Karasik, Tamis-LeMonda, & Adolph, 2014).

As children develop, they learn to communicate by interacting with their environment and using their sensory and motor skills (Karasik et al., 2014).

When visual, tactile, and auditory skills are combined, they emerge as perceptual skills. These perceptual skills are then used to gauge spatial relationships, discriminate between figure and ground, and develop hand–eye coordination (Libertus & Hauf, 2017).

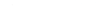

Exploring and solving problems

Problem solving can be seen in very young children when they play with blocks, objects, and balls. It is entwined with perceptual skills and memory. Very young children playing with blocks, picking up a spoon, or even looking for objects demonstrate the development of problem solving skills (Goldschmied & Jackson, 1994). This is known as heuristic play (Auld, 2002).

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

To understand how people think and process information, it is important to look at how cognitive skills are used in everyday life. Here are some real-life examples of cognitive development.

Decision making

To make a decision, a person needs to weigh up information and make the best choice. As an example, think about a restaurant menu. There is a lot of information on the menu about food options. Reading the menu requires you to analyze the data then reduce it to make a specific meal choice.

Recognition of faces

Have you ever wondered why it is possible to recognize a person even when they have grown a beard, wear makeup or glasses, or change their hair color?

Cognitive processing is used in facial recognition and explains why we still recognize people we meet after a long time, despite sometimes drastic changes in their physical appearance.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

This widely used therapeutic intervention is based on an understanding of cognition and how it changes behavior.

It is based on the premise that cognition and behavior are linked, and this theory is often used to help individuals overcome negative thinking patterns . CBT provides them with alternative positive thinking patterns to promote positive behavior.

The cognitive processes of short-term and long-term memory explain forgetting. An example of forgetting can be seen in students who do not study for exams. If they do not transfer the information from short-term to long-term memory, they forget the knowledge required for the examination and may fail.

Thinking and cognition are required for reasoning. Reasoning involves intellect and an attempt to search for the truth from new or existing information. An example of this activity can be seen in political debates on television.

They all attempt to explain how cognitive development occurs.

Piaget’s cognitive development theory

Jean Piaget (1936) is famous for his theory of cognition that considers four specific stages of development .

The sensorimotor stage (0–2 years) is when infants build an understanding of the world through their senses and movement (touching, feeling, listening, and watching). This is when children develop object permanence.

The pre-operational stage (2–7 years) is when language and abstract thinking arise. This is the stage of symbolic play.

When a child is 7 years old, they enter Piaget’s concrete-operational stage , which goes up to 11 years. This is when logical and concrete thought come into action.

At the age of 11 onward, children learn logical and abstract rules and solve problems. Piaget described this as the formal operational stage.

Vygotsky’s theory

Lev Vygotsky described an alternative theory. He believed that children’s cognitive development arises through their physical interaction with the world (Vygotsky, 1932). Vygotsky’s theory is based on the premise that the support of adults and peers enables the development of higher psychological functions. His is known as the sociocultural theory (Yasnitsky, 2018).

Vygotsky believed that a child’s initial social interactions prompt development, and as the child internalizes learning, this shifts their cognition to an individual level.

Vygotsky (1932) considered children akin to apprentices, learning from the more experienced, who understand their needs.

There are two main themes of Vygotsky’s theory.

The zone of proximal development is described as the distance between the actual development level and the level of potential. This is determined by independent problem solving when children are collaborating with more able peers or under the guidance of an adult (Vygotsky, 1931).

This may explain why some children perform better in the presence of others who have more knowledge and skills but more poorly on their own. These skills, displayed in a social context but not in an isolated setting, are within the zone of proximal development. This highlights how a more knowledgeable person can provide support to a child’s cognitive development (Vygotsky, 1932).

Thinking and speech are considered essential. Vygotsky described a connected relationship between language development and the thinking process. His theory explains how younger children use speech to think out loud. Gradually, they evolve silent inner speech once mental concepts and cognitive awareness are developed (Vygotsky, 1931).

Ecological systems theory

Another more modern theory, similar in some sense to Vygotsky’s, is one by American psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner (1974). He suggested that a child’s environment, within an arrangement of structures, has a differing impact on the child (Bronfenbrenner, 1974).

Bronfenbrenner’s five structures are the micro-system, mesosystem, ecosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem. These concern the surrounding environment, family, school, values, customs, and cultures. They are interrelated, with each system influencing others to impact the child’s development (Bronfenbrenner, 1977).

Bronfenbrenner (1974) considered the micro-system as the most influential. This system contains the developing child, family, and educational environment, and impacts a child’s cognitive development the most.

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development – Sprouts

Adolescence is a period of transition between late childhood and the beginning of adulthood.

Based on Inhelder and Piaget’s (1958) stage theory of cognitive growth, adolescence is when children become self-conscious and concerned with other people’s opinions as they go through puberty (Steinberg, 2005). The psychosocial context of adolescents is considerably different from that of children and adults.

The brain goes through a dramatic remodeling process in adolescence. Neural plasticity facilitates the development of social cognitive skills (Huttenlocher, 1979). Structural development of cortical regions of the brain may significantly influence cognitive functioning during adolescence (Huttenlocher, De Courten, Garey, & Van der Loos, 1983).

Recognition of facial expressions and emotion is one area of social cognition that has been investigated in adolescence (Herba & Phillips, 2004). The amygdala, a part of the brain associated with emotion processing, was found to be significantly activated in response to fearful facial expressions in a study of adolescents (Baird et al., 1999). This highlights that the development of emotional cognition is prominent in this age group.

Here are three we find most interesting.

1. A cognitive habilitation program for children

Millians and Coles (2014) studied five children who had experienced learning and academic deficits because of prenatal alcohol exposure. Before and after an intervention, researchers gave standardized tests of nonverbal reasoning and academic achievement to the children.

Four of the five children showed increases to the average range of scores on measures of nonverbal, reasoning, reading, and mathematics. This study highlighted the benefit of interventions to address children’s cognitive difficulties and learning problems, even when the cognitive difficulties are apparent from birth.

2. Bilingual babies and enhanced learning

Introducing babies to two languages has been shown to improve cognitive abilities, especially problem solving (Ramírez-Esparza, García-Sierra, & Kuhl, 2017).

Spanish babies between 7 and 33.5 months were given one hour of English sessions for 18 weeks. By the end of the 18 weeks, the children produced an average of 74 English words and phrases. This study showed that the age between 0 and 3 years is the best time to learn a second language and gain excellent proficiency. However, languages can be learned at any time in life.

3. Unusual autobiographical memory

In an unusual case study, a woman described as ‘AJ’ was found to have highly superior autobiographical memory, a condition that dominated her life (Parker, Cahill, & McGaugh, 2006).

Her memory was described as ‘nonstop, uncontrollable and automatic.’ AJ did not use any mnemonic devices to recall. She could tell you what she was doing on any day of her life.

AJ could also recall her past with a high level of accuracy. This study provided some insightful details of the neurobiology of autobiographical memory and changes in the prefrontal cortex that cause these superior cognitive abilities.

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

If this article has piqued your interest and you wish to know more about improving cognitive function, take a look at these related posts.

How to Improve Cognitive Function: 6 Mental Fitness Exercises

This article describes ways to test your clients’ cognitive abilities. There are several exercises and games you may wish to use with your clients to help them improve their cognitive health and functioning, and help them maintain this throughout their lifespan.

10 Neurological Benefits of Exercise

Physical exercise is an excellent way to boost brain functioning. This fascinating article explains the benefits of exercise to buffer stress and aging, and maintain positive mental health and cognition.

Sleep Hygiene Tips

Alongside exercise, sleep is an essential component for the brain to function properly. This article has excellent sleep hygiene ideas , and you can use the checklists and worksheets to support your clients’ sleep, enabling them to boost their brain functioning.

17 Positive Psychology Exercises

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others enhance their wellbeing, this signature collection contains 17 validated positive psychology tools for practitioners. Use them to help others flourish and thrive.

The first few years of a child’s life show rapid changes in brain development. This is part of the child’s cognitive development. There are a number of different theories of how and when this occurs. These are not set in stone, but are a guide to the cognitive development of children.

If children are not achieving their milestones at the approximate times they should, extra support can help make a difference. Even children with fetal alcohol syndrome can achieve considerably improved cognition with specialized support.

Remember, cognitive development does not end in childhood, as Piaget’s schema theory first suggested. It continues through adolescence and beyond. Cognitive development changes carry on through much of a teenager’s life as the brain is developing.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- Auld, S. (2002). Five key principles of heuristic play. The First Years: Nga Tau Tuatahi . New Zealand Journal of Infant and Toddler Education , 4 (2), 36–37.

- Baird, A. A., Gruber, S. A., Fein, D. A., Maas, L. C., Steingard, R. J., Renshaw, P. F., … Yurgelun-Todd, D. A. (1999). Functional magnetic resonance imaging of facial affect recognition in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry , 38 , 195–199.

- Bhatt, G.D. (2000). Organizing knowledge in the knowledge development cycle. Journal of Knowledge Management , 4 (1), 15–26.

- Brant, A. M., Munakata, Y., Boomsma, D. I., DeFries, J. C., Haworth, C. M. A., Keller, M. C., … Hewitt, J. K. (2013). The nature and nurture of high IQ: An extended sensitive period for intellectual development. Psychological Science , 28 (8), 1487–1495.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1974). Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood. Child Development , 45 (1), 1–5.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist , 32 (7), 513–531.

- Carpendale, J. I. M., & Lewis, C. (2015). The development of social understanding. In L. S. Liben, U. Müller, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.). Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Cognitive Processes (7th ed.) (pp. 381–424). John Wiley & Sons.

- Dosman, C. F., Andrews, D., & Goulden, K. J. (2012). Evidence-based milestone ages as a framework for developmental surveillance. Paediatrics & Child Health , 17 (10), 561–568.

- Ford, D. Y. (1996). Reversing underachievement among gifted Black students: Promising practices and programs . Teachers College Press.

- Ford, D. Y. (2004). Intelligence testing and cultural diversity: Concerns, cautions and considerations (RM04204). The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented.

- Gauvain, M., & Richert, R. (2016). Cognitive development. In H.S. Friedman (Ed.) Encyclopedia of mental health (2nd ed.) (pp. 317–323). Academic Press.

- Goldschmied, E., & Jackson, S. (1994). People under three. Young children in daycare . Routledge.

- Herba, C., & Phillips, M. (2004). Annotation: Development of facial expression recognition from childhood to adolescence: Behavioural and neurological perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 45 (7), 1185–1198.

- Huttenlocher, P. R. (1979). Synaptic density in human frontal cortex – developmental changes and effects of aging. Brain Research , 163 , 195–205.

- Huttenlocher, P. R., De Courten, C., Garey, L. J., & Van der Loos, H. (1983). Synaptic development in human cerebral cortex. International Journal of Neurology , 16–17 , 144–54.

- Inhelder, B., & Piaget, J. (1958). The growth of logical thinking from childhood to adolescence . Basic Books.

- Jensen, A. R. (1969). Intelligence, learning ability and socioeconomic status. The Journal of Special Education , 3 (1), 23–35.

- Jensen, A. R. (1974). Ethnicity and scholastic achievement. Psychological Reports , 34(2), 659–668.

- Karasik, L. B., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., & Adolph, K. E. (2014). Crawling and walking infants elicit different verbal responses from mothers. Developmental Science , 17 , 388–395.

- Kashyap, N., & Minda, J. P. (2016). The psychology of thinking: Reasoning, decision-making, and problem-solving. Psychology Learning & Teaching , 15 (3), 384–385.

- Libertus, K., & Hauf, P. (2017). Editorial: Motor skills and their foundational role for perceptual, social, and cognitive development. Frontiers in Psychology , 8 .

- Millians, M. N., & Coles, C. D. (2014). Case study: Saturday cognitive habilitation program children with prenatal alcohol exposure. Psychological Neuroscience , 7 , 163–173.

- Needham, A., Barrett, T., & Peterman, K. (2002). A pick-me-up for infants’ exploratory skills: Early simulated experiences reaching for objects using ‘sticky mittens’ enhances young infants’ object exploration skills. Infant Behavior and Development , 25 , 279–295.

- Parker, E. S., Cahill, L., & McGaugh, J. L. (2006). A case of unusual autobiographical remembering. Neurocase , 12 (1), 35–49.

- Piaget, J. (1936). Origins of intelligence in the child . Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Piaget, J. (1951). Play, dreams and imitation in childhood (vol. 25). Routledge.

- Ramírez-Esparza, N., García-Sierra, A., & Kuhl, K. P. (2017). The impact of early social interaction on later language development in Spanish–English bilingual infants. Child Development , 88 (4), 1216–1234.

- Roulstone, S., Loader, S., Northstone, K., & Beveridge, M. (2002). The speech and language of children aged 25 months: Descriptive date from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Early Child Development and Care , 172 , 259–268.

- Stark, S. M., Yassa, M. A., & Stark, C. E. L. (2010). Individual differences in spatial pattern separation performance associated with healthy aging in humans. Learning and Memory , 17 (6), 284–288.

- Steinberg, L. (2005). Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences , 9 , 69–74.

- Von Eckardt, B. (1996). What is cognitive science? MIT Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1931). Adolescent pedagogy: The development of thinking and concept formation in adolescence . Marxists.org.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1932). Thought and language. Chapter 6: The development of scientific concepts in childhood . Marxists.org.

- Yasnitsky, A. (2018). Vygotsky’s science of superman: from utopia to concrete psychology. In A. Yasnitsky (Ed.). Questioning Vygotsky’s legacy: Scientific psychology or heroic cult . Routledge.

- Ward, E. V., Berry, C. J., & Shanks, D. R. (2013). An effect of age on implicit memory that is not due to explicit contamination: Implications for single and multiple-systems theories. Psychology and Aging , 28 (2), 429–442.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

As a teacher in Primary School, I have found this article to be of great value. I sincerely appreciate your outstanding work.

The article was excellent. I am a student doing research. This article went into key details, which is what I was looking for.

This article has tremendously helped me to come up with precise teaching notes for my educational psychology class. It is mu fervent hope that I will get more useful notes on social development.

Where did she learn her hypnotherapy? I am interested in learning as part of my holistic therapy.

Hi Ricardo, Thank you for asking. I undertook my hypnotherapy training with The London College of Clinical Hypnosis (LCCH) in the UK. It is defined as ‘Clinical Hypnosis’ given that the course very much focused on medical conditions and treatment, but not entirely. They have been up and running since 1984 and are still course providers and a well recognised school globally. I am not sure where you are based in the world. Looking at their present website, I have noticed they also now provide online courses. Nevertheless there are many more organisations who provide Clinical Hypnosis training than when I undertook my course. I hope that helps you.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

What Is the Health Belief Model? An Updated Look

Early detection through regular screening is key to preventing and treating many diseases. Despite this fact, participation in screening tends to be low. In Australia, [...]

Positive Pain Management: How to Better Manage Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is a condition that causes widespread, constant pain and distress and fills both sufferers and the healthcare professionals who treat them with dread. [...]

Mental Health in Teens: 10 Risk & Protective Factors

31.9% of adolescents have anxiety-related disorders (ADAA, n.d.). According to Solmi et al. (2022), the age at which mental health disorders most commonly begin to [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Module 7: Thinking, Reasoning, and Problem-Solving

This module is about how a solid working knowledge of psychological principles can help you to think more effectively, so you can succeed in school and life. You might be inclined to believe that—because you have been thinking for as long as you can remember, because you are able to figure out the solution to many problems, because you feel capable of using logic to argue a point, because you can evaluate whether the things you read and hear make sense—you do not need any special training in thinking. But this, of course, is one of the key barriers to helping people think better. If you do not believe that there is anything wrong, why try to fix it?

The human brain is indeed a remarkable thinking machine, capable of amazing, complex, creative, logical thoughts. Why, then, are we telling you that you need to learn how to think? Mainly because one major lesson from cognitive psychology is that these capabilities of the human brain are relatively infrequently realized. Many psychologists believe that people are essentially “cognitive misers.” It is not that we are lazy, but that we have a tendency to expend the least amount of mental effort necessary. Although you may not realize it, it actually takes a great deal of energy to think. Careful, deliberative reasoning and critical thinking are very difficult. Because we seem to be successful without going to the trouble of using these skills well, it feels unnecessary to develop them. As you shall see, however, there are many pitfalls in the cognitive processes described in this module. When people do not devote extra effort to learning and improving reasoning, problem solving, and critical thinking skills, they make many errors.

As is true for memory, if you develop the cognitive skills presented in this module, you will be more successful in school. It is important that you realize, however, that these skills will help you far beyond school, even more so than a good memory will. Although it is somewhat useful to have a good memory, ten years from now no potential employer will care how many questions you got right on multiple choice exams during college. All of them will, however, recognize whether you are a logical, analytical, critical thinker. With these thinking skills, you will be an effective, persuasive communicator and an excellent problem solver.

The module begins by describing different kinds of thought and knowledge, especially conceptual knowledge and critical thinking. An understanding of these differences will be valuable as you progress through school and encounter different assignments that require you to tap into different kinds of knowledge. The second section covers deductive and inductive reasoning, which are processes we use to construct and evaluate strong arguments. They are essential skills to have whenever you are trying to persuade someone (including yourself) of some point, or to respond to someone’s efforts to persuade you. The module ends with a section about problem solving. A solid understanding of the key processes involved in problem solving will help you to handle many daily challenges.

7.1. Different kinds of thought

7.2. Reasoning and Judgment

7.3. Problem Solving

READING WITH PURPOSE

Remember and understand.

By reading and studying Module 7, you should be able to remember and describe:

- Concepts and inferences (7.1)

- Procedural knowledge (7.1)

- Metacognition (7.1)

- Characteristics of critical thinking: skepticism; identify biases, distortions, omissions, and assumptions; reasoning and problem solving skills (7.1)

- Reasoning: deductive reasoning, deductively valid argument, inductive reasoning, inductively strong argument, availability heuristic, representativeness heuristic (7.2)

- Fixation: functional fixedness, mental set (7.3)

- Algorithms, heuristics, and the role of confirmation bias (7.3)

- Effective problem solving sequence (7.3)

By reading and thinking about how the concepts in Module 6 apply to real life, you should be able to:

- Identify which type of knowledge a piece of information is (7.1)

- Recognize examples of deductive and inductive reasoning (7.2)

- Recognize judgments that have probably been influenced by the availability heuristic (7.2)

- Recognize examples of problem solving heuristics and algorithms (7.3)

Analyze, Evaluate, and Create

By reading and thinking about Module 6, participating in classroom activities, and completing out-of-class assignments, you should be able to:

- Use the principles of critical thinking to evaluate information (7.1)

- Explain whether examples of reasoning arguments are deductively valid or inductively strong (7.2)

- Outline how you could try to solve a problem from your life using the effective problem solving sequence (7.3)

7.1. Different kinds of thought and knowledge

- Take a few minutes to write down everything that you know about dogs.

- Do you believe that:

- Psychic ability exists?

- Hypnosis is an altered state of consciousness?

- Magnet therapy is effective for relieving pain?

- Aerobic exercise is an effective treatment for depression?

- UFO’s from outer space have visited earth?

On what do you base your belief or disbelief for the questions above?

Of course, we all know what is meant by the words think and knowledge . You probably also realize that they are not unitary concepts; there are different kinds of thought and knowledge. In this section, let us look at some of these differences. If you are familiar with these different kinds of thought and pay attention to them in your classes, it will help you to focus on the right goals, learn more effectively, and succeed in school. Different assignments and requirements in school call on you to use different kinds of knowledge or thought, so it will be very helpful for you to learn to recognize them (Anderson, et al. 2001).

Factual and conceptual knowledge

Module 5 introduced the idea of declarative memory, which is composed of facts and episodes. If you have ever played a trivia game or watched Jeopardy on TV, you realize that the human brain is able to hold an extraordinary number of facts. Likewise, you realize that each of us has an enormous store of episodes, essentially facts about events that happened in our own lives. It may be difficult to keep that in mind when we are struggling to retrieve one of those facts while taking an exam, however. Part of the problem is that, in contradiction to the advice from Module 5, many students continue to try to memorize course material as a series of unrelated facts (picture a history student simply trying to memorize history as a set of unrelated dates without any coherent story tying them together). Facts in the real world are not random and unorganized, however. It is the way that they are organized that constitutes a second key kind of knowledge, conceptual.

Concepts are nothing more than our mental representations of categories of things in the world. For example, think about dogs. When you do this, you might remember specific facts about dogs, such as they have fur and they bark. You may also recall dogs that you have encountered and picture them in your mind. All of this information (and more) makes up your concept of dog. You can have concepts of simple categories (e.g., triangle), complex categories (e.g., small dogs that sleep all day, eat out of the garbage, and bark at leaves), kinds of people (e.g., psychology professors), events (e.g., birthday parties), and abstract ideas (e.g., justice). Gregory Murphy (2002) refers to concepts as the “glue that holds our mental life together” (p. 1). Very simply, summarizing the world by using concepts is one of the most important cognitive tasks that we do. Our conceptual knowledge is our knowledge about the world. Individual concepts are related to each other to form a rich interconnected network of knowledge. For example, think about how the following concepts might be related to each other: dog, pet, play, Frisbee, chew toy, shoe. Or, of more obvious use to you now, how these concepts are related: working memory, long-term memory, declarative memory, procedural memory, and rehearsal? Because our minds have a natural tendency to organize information conceptually, when students try to remember course material as isolated facts, they are working against their strengths.

One last important point about concepts is that they allow you to instantly know a great deal of information about something. For example, if someone hands you a small red object and says, “here is an apple,” they do not have to tell you, “it is something you can eat.” You already know that you can eat it because it is true by virtue of the fact that the object is an apple; this is called drawing an inference , assuming that something is true on the basis of your previous knowledge (for example, of category membership or of how the world works) or logical reasoning.

Procedural knowledge

Physical skills, such as tying your shoes, doing a cartwheel, and driving a car (or doing all three at the same time, but don’t try this at home) are certainly a kind of knowledge. They are procedural knowledge, the same idea as procedural memory that you saw in Module 5. Mental skills, such as reading, debating, and planning a psychology experiment, are procedural knowledge, as well. In short, procedural knowledge is the knowledge how to do something (Cohen & Eichenbaum, 1993).

Metacognitive knowledge

Floyd used to think that he had a great memory. Now, he has a better memory. Why? Because he finally realized that his memory was not as great as he once thought it was. Because Floyd eventually learned that he often forgets where he put things, he finally developed the habit of putting things in the same place. (Unfortunately, he did not learn this lesson before losing at least 5 watches and a wedding ring.) Because he finally realized that he often forgets to do things, he finally started using the To Do list app on his phone. And so on. Floyd’s insights about the real limitations of his memory have allowed him to remember things that he used to forget.

All of us have knowledge about the way our own minds work. You may know that you have a good memory for people’s names and a poor memory for math formulas. Someone else might realize that they have difficulty remembering to do things, like stopping at the store on the way home. Others still know that they tend to overlook details. This knowledge about our own thinking is actually quite important; it is called metacognitive knowledge, or metacognition . Like other kinds of thinking skills, it is subject to error. For example, in unpublished research, one of the authors surveyed about 120 General Psychology students on the first day of the term. Among other questions, the students were asked them to predict their grade in the class and report their current Grade Point Average. Two-thirds of the students predicted that their grade in the course would be higher than their GPA. (The reality is that at our college, students tend to earn lower grades in psychology than their overall GPA.) Another example: Students routinely report that they thought they had done well on an exam, only to discover, to their dismay, that they were wrong (more on that important problem in a moment). Both errors reveal a breakdown in metacognition.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

In general, most college students probably do not study enough. For example, using data from the National Survey of Student Engagement, Fosnacht, McCormack, and Lerma (2018) reported that first-year students at 4-year colleges in the U.S. averaged less than 14 hours per week preparing for classes. The typical suggestion is that you should spend two hours outside of class for every hour in class, or 24 – 30 hours per week for a full-time student. Clearly, students in general are nowhere near that recommended mark. Many observers, including some faculty, believe that this shortfall is a result of students being too busy or lazy. Now, it may be true that many students are too busy, with work and family obligations, for example. Others, are not particularly motivated in school, and therefore might correctly be labeled lazy. A third possible explanation, however, is that some students might not think they need to spend this much time. And this is a matter of metacognition. Consider the scenario that we mentioned above, students thinking they had done well on an exam only to discover that they did not. Justin Kruger and David Dunning examined scenarios very much like this in 1999. Kruger and Dunning gave research participants tests measuring humor, logic, and grammar. Then, they asked the participants to assess their own abilities and test performance in these areas. They found that participants in general tended to overestimate their abilities, already a problem with metacognition. Importantly, the participants who scored the lowest overestimated their abilities the most. Specifically, students who scored in the bottom quarter (averaging in the 12th percentile) thought they had scored in the 62nd percentile. This has become known as the Dunning-Kruger effect . Many individual faculty members have replicated these results with their own student on their course exams, including the authors of this book. Think about it. Some students who just took an exam and performed poorly believe that they did well before seeing their score. It seems very likely that these are the very same students who stopped studying the night before because they thought they were “done.” Quite simply, it is not just that they did not know the material. They did not know that they did not know the material. That is poor metacognition.

In order to develop good metacognitive skills, you should continually monitor your thinking and seek frequent feedback on the accuracy of your thinking (Medina, Castleberry, & Persky 2017). For example, in classes get in the habit of predicting your exam grades. As soon as possible after taking an exam, try to find out which questions you missed and try to figure out why. If you do this soon enough, you may be able to recall the way it felt when you originally answered the question. Did you feel confident that you had answered the question correctly? Then you have just discovered an opportunity to improve your metacognition. Be on the lookout for that feeling and respond with caution.

concept : a mental representation of a category of things in the world

Dunning-Kruger effect : individuals who are less competent tend to overestimate their abilities more than individuals who are more competent do

inference : an assumption about the truth of something that is not stated. Inferences come from our prior knowledge and experience, and from logical reasoning

metacognition : knowledge about one’s own cognitive processes; thinking about your thinking

Critical thinking

One particular kind of knowledge or thinking skill that is related to metacognition is critical thinking (Chew, 2020). You may have noticed that critical thinking is an objective in many college courses, and thus it could be a legitimate topic to cover in nearly any college course. It is particularly appropriate in psychology, however. As the science of (behavior and) mental processes, psychology is obviously well suited to be the discipline through which you should be introduced to this important way of thinking.

More importantly, there is a particular need to use critical thinking in psychology. We are all, in a way, experts in human behavior and mental processes, having engaged in them literally since birth. Thus, perhaps more than in any other class, students typically approach psychology with very clear ideas and opinions about its subject matter. That is, students already “know” a lot about psychology. The problem is, “it ain’t so much the things we don’t know that get us into trouble. It’s the things we know that just ain’t so” (Ward, quoted in Gilovich 1991). Indeed, many of students’ preconceptions about psychology are just plain wrong. Randolph Smith (2002) wrote a book about critical thinking in psychology called Challenging Your Preconceptions, highlighting this fact. On the other hand, many of students’ preconceptions about psychology are just plain right! But wait, how do you know which of your preconceptions are right and which are wrong? And when you come across a research finding or theory in this class that contradicts your preconceptions, what will you do? Will you stick to your original idea, discounting the information from the class? Will you immediately change your mind? Critical thinking can help us sort through this confusing mess.

But what is critical thinking? The goal of critical thinking is simple to state (but extraordinarily difficult to achieve): it is to be right, to draw the correct conclusions, to believe in things that are true and to disbelieve things that are false. We will provide two definitions of critical thinking (or, if you like, one large definition with two distinct parts). First, a more conceptual one: Critical thinking is thinking like a scientist in your everyday life (Schmaltz, Jansen, & Wenckowski, 2017). Our second definition is more operational; it is simply a list of skills that are essential to be a critical thinker. Critical thinking entails solid reasoning and problem solving skills; skepticism; and an ability to identify biases, distortions, omissions, and assumptions. Excellent deductive and inductive reasoning, and problem solving skills contribute to critical thinking. So, you can consider the subject matter of sections 7.2 and 7.3 to be part of critical thinking. Because we will be devoting considerable time to these concepts in the rest of the module, let us begin with a discussion about the other aspects of critical thinking.

Let’s address that first part of the definition. Scientists form hypotheses, or predictions about some possible future observations. Then, they collect data, or information (think of this as making those future observations). They do their best to make unbiased observations using reliable techniques that have been verified by others. Then, and only then, they draw a conclusion about what those observations mean. Oh, and do not forget the most important part. “Conclusion” is probably not the most appropriate word because this conclusion is only tentative. A scientist is always prepared that someone else might come along and produce new observations that would require a new conclusion be drawn. Wow! If you like to be right, you could do a lot worse than using a process like this.

A Critical Thinker’s Toolkit

Now for the second part of the definition. Good critical thinkers (and scientists) rely on a variety of tools to evaluate information. Perhaps the most recognizable tool for critical thinking is skepticism (and this term provides the clearest link to the thinking like a scientist definition, as you are about to see). Some people intend it as an insult when they call someone a skeptic. But if someone calls you a skeptic, if they are using the term correctly, you should consider it a great compliment. Simply put, skepticism is a way of thinking in which you refrain from drawing a conclusion or changing your mind until good evidence has been provided. People from Missouri should recognize this principle, as Missouri is known as the Show-Me State. As a skeptic, you are not inclined to believe something just because someone said so, because someone else believes it, or because it sounds reasonable. You must be persuaded by high quality evidence.

Of course, if that evidence is produced, you have a responsibility as a skeptic to change your belief. Failure to change a belief in the face of good evidence is not skepticism; skepticism has open mindedness at its core. M. Neil Browne and Stuart Keeley (2018) use the term weak sense critical thinking to describe critical thinking behaviors that are used only to strengthen a prior belief. Strong sense critical thinking, on the other hand, has as its goal reaching the best conclusion. Sometimes that means strengthening your prior belief, but sometimes it means changing your belief to accommodate the better evidence.

Many times, a failure to think critically or weak sense critical thinking is related to a bias , an inclination, tendency, leaning, or prejudice. Everybody has biases, but many people are unaware of them. Awareness of your own biases gives you the opportunity to control or counteract them. Unfortunately, however, many people are happy to let their biases creep into their attempts to persuade others; indeed, it is a key part of their persuasive strategy. To see how these biases influence messages, just look at the different descriptions and explanations of the same events given by people of different ages or income brackets, or conservative versus liberal commentators, or by commentators from different parts of the world. Of course, to be successful, these people who are consciously using their biases must disguise them. Even undisguised biases can be difficult to identify, so disguised ones can be nearly impossible.

Here are some common sources of biases:

- Personal values and beliefs. Some people believe that human beings are basically driven to seek power and that they are typically in competition with one another over scarce resources. These beliefs are similar to the world-view that political scientists call “realism.” Other people believe that human beings prefer to cooperate and that, given the chance, they will do so. These beliefs are similar to the world-view known as “idealism.” For many people, these deeply held beliefs can influence, or bias, their interpretations of such wide ranging situations as the behavior of nations and their leaders or the behavior of the driver in the car ahead of you. For example, if your worldview is that people are typically in competition and someone cuts you off on the highway, you may assume that the driver did it purposely to get ahead of you. Other types of beliefs about the way the world is or the way the world should be, for example, political beliefs, can similarly become a significant source of bias.

- Racism, sexism, ageism and other forms of prejudice and bigotry. These are, sadly, a common source of bias in many people. They are essentially a special kind of “belief about the way the world is.” These beliefs—for example, that women do not make effective leaders—lead people to ignore contradictory evidence (examples of effective women leaders, or research that disputes the belief) and to interpret ambiguous evidence in a way consistent with the belief.

- Self-interest. When particular people benefit from things turning out a certain way, they can sometimes be very susceptible to letting that interest bias them. For example, a company that will earn a profit if they sell their product may have a bias in the way that they give information about their product. A union that will benefit if its members get a generous contract might have a bias in the way it presents information about salaries at competing organizations. (Note that our inclusion of examples describing both companies and unions is an explicit attempt to control for our own personal biases). Home buyers are often dismayed to discover that they purchased their dream house from someone whose self-interest led them to lie about flooding problems in the basement or back yard. This principle, the biasing power of self-interest, is likely what led to the famous phrase Caveat Emptor (let the buyer beware) .

Knowing that these types of biases exist will help you evaluate evidence more critically. Do not forget, though, that people are not always keen to let you discover the sources of biases in their arguments. For example, companies or political organizations can sometimes disguise their support of a research study by contracting with a university professor, who comes complete with a seemingly unbiased institutional affiliation, to conduct the study.

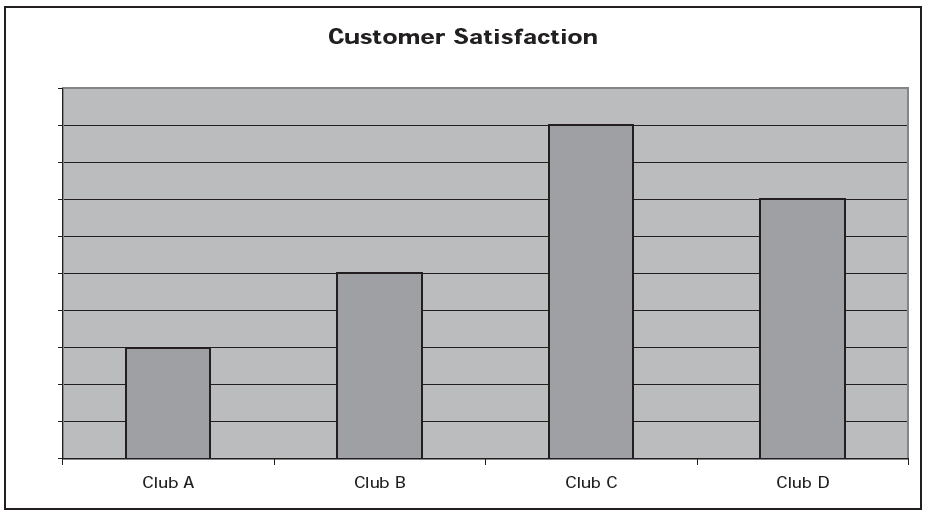

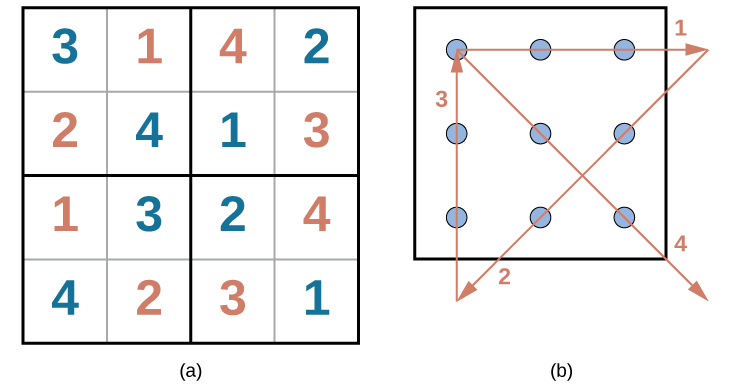

People’s biases, conscious or unconscious, can lead them to make omissions, distortions, and assumptions that undermine our ability to correctly evaluate evidence. It is essential that you look for these elements. Always ask, what is missing, what is not as it appears, and what is being assumed here? For example, consider this (fictional) chart from an ad reporting customer satisfaction at 4 local health clubs.

Clearly, from the results of the chart, one would be tempted to give Club C a try, as customer satisfaction is much higher than for the other 3 clubs.

There are so many distortions and omissions in this chart, however, that it is actually quite meaningless. First, how was satisfaction measured? Do the bars represent responses to a survey? If so, how were the questions asked? Most importantly, where is the missing scale for the chart? Although the differences look quite large, are they really?

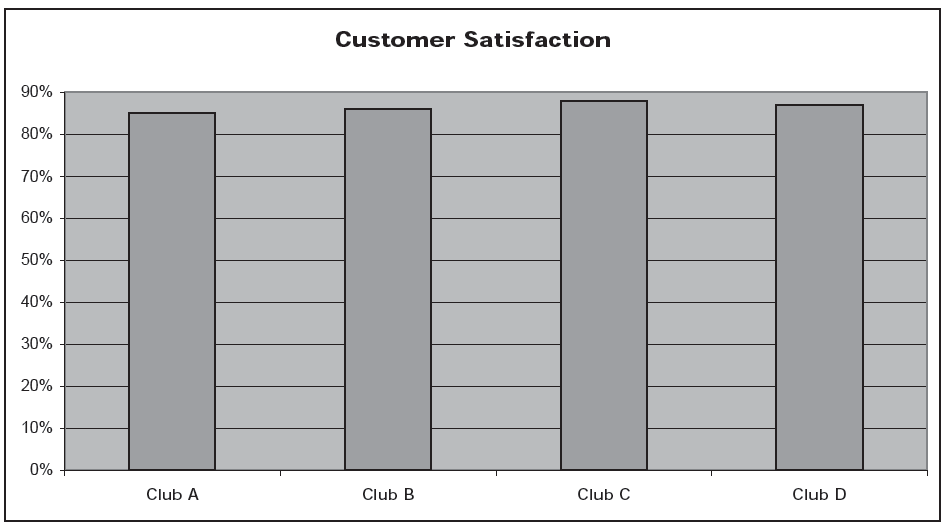

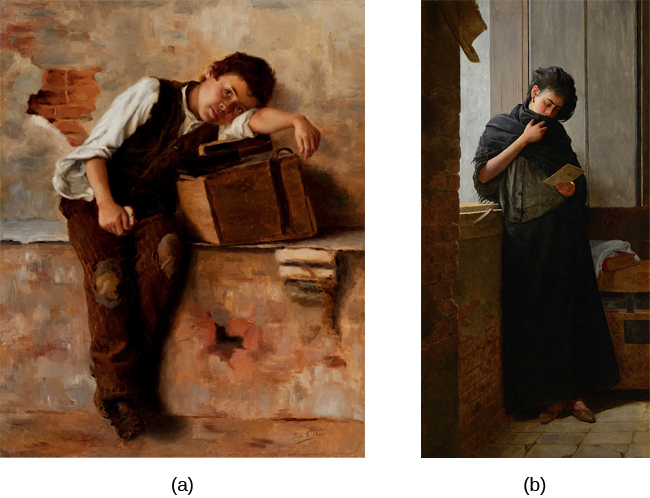

Well, here is the same chart, with a different scale, this time labeled:

Club C is not so impressive any more, is it? In fact, all of the health clubs have customer satisfaction ratings (whatever that means) between 85% and 88%. In the first chart, the entire scale of the graph included only the percentages between 83 and 89. This “judicious” choice of scale—some would call it a distortion—and omission of that scale from the chart make the tiny differences among the clubs seem important, however.

Also, in order to be a critical thinker, you need to learn to pay attention to the assumptions that underlie a message. Let us briefly illustrate the role of assumptions by touching on some people’s beliefs about the criminal justice system in the US. Some believe that a major problem with our judicial system is that many criminals go free because of legal technicalities. Others believe that a major problem is that many innocent people are convicted of crimes. The simple fact is, both types of errors occur. A person’s conclusion about which flaw in our judicial system is the greater tragedy is based on an assumption about which of these is the more serious error (letting the guilty go free or convicting the innocent). This type of assumption is called a value assumption (Browne and Keeley, 2018). It reflects the differences in values that people develop, differences that may lead us to disregard valid evidence that does not fit in with our particular values.

Oh, by the way, some students probably noticed this, but the seven tips for evaluating information that we shared in Module 1 are related to this. Actually, they are part of this section. The tips are, to a very large degree, set of ideas you can use to help you identify biases, distortions, omissions, and assumptions. If you do not remember this section, we strongly recommend you take a few minutes to review it.

skepticism : a way of thinking in which you refrain from drawing a conclusion or changing your mind until good evidence has been provided

bias : an inclination, tendency, leaning, or prejudice

- Which of your beliefs (or disbeliefs) from the Activate exercise for this section were derived from a process of critical thinking? If some of your beliefs were not based on critical thinking, are you willing to reassess these beliefs? If the answer is no, why do you think that is? If the answer is yes, what concrete steps will you take?

7.2 Reasoning and Judgment

- What percentage of kidnappings are committed by strangers?

- Which area of the house is riskiest: kitchen, bathroom, or stairs?

- What is the most common cancer in the US?

- What percentage of workplace homicides are committed by co-workers?

An essential set of procedural thinking skills is reasoning , the ability to generate and evaluate solid conclusions from a set of statements or evidence. You should note that these conclusions (when they are generated instead of being evaluated) are one key type of inference that we described in Section 7.1. There are two main types of reasoning, deductive and inductive.

Deductive reasoning

Suppose your teacher tells you that if you get an A on the final exam in a course, you will get an A for the whole course. Then, you get an A on the final exam. What will your final course grade be? Most people can see instantly that you can conclude with certainty that you will get an A for the course. This is a type of reasoning called deductive reasoning , which is defined as reasoning in which a conclusion is guaranteed to be true as long as the statements leading to it are true. The three statements can be listed as an argument , with two beginning statements and a conclusion:

Statement 1: If you get an A on the final exam, you will get an A for the course

Statement 2: You get an A on the final exam

Conclusion: You will get an A for the course

This particular arrangement, in which true beginning statements lead to a guaranteed true conclusion, is known as a deductively valid argument . Although deductive reasoning is often the subject of abstract, brain-teasing, puzzle-like word problems, it is actually an extremely important type of everyday reasoning. It is just hard to recognize sometimes. For example, imagine that you are looking for your car keys and you realize that they are either in the kitchen drawer or in your book bag. After looking in the kitchen drawer, you instantly know that they must be in your book bag. That conclusion results from a simple deductive reasoning argument. In addition, solid deductive reasoning skills are necessary for you to succeed in the sciences, philosophy, math, computer programming, and any endeavor involving the use of logic to persuade others to your point of view or to evaluate others’ arguments.

Cognitive psychologists, and before them philosophers, have been quite interested in deductive reasoning, not so much for its practical applications, but for the insights it can offer them about the ways that human beings think. One of the early ideas to emerge from the examination of deductive reasoning is that people learn (or develop) mental versions of rules that allow them to solve these types of reasoning problems (Braine, 1978; Braine, Reiser, & Rumain, 1984). The best way to see this point of view is to realize that there are different possible rules, and some of them are very simple. For example, consider this rule of logic:

therefore q

Logical rules are often presented abstractly, as letters, in order to imply that they can be used in very many specific situations. Here is a concrete version of the of the same rule:

I’ll either have pizza or a hamburger for dinner tonight (p or q)

I won’t have pizza (not p)

Therefore, I’ll have a hamburger (therefore q)

This kind of reasoning seems so natural, so easy, that it is quite plausible that we would use a version of this rule in our daily lives. At least, it seems more plausible than some of the alternative possibilities—for example, that we need to have experience with the specific situation (pizza or hamburger, in this case) in order to solve this type of problem easily. So perhaps there is a form of natural logic (Rips, 1990) that contains very simple versions of logical rules. When we are faced with a reasoning problem that maps onto one of these rules, we use the rule.

But be very careful; things are not always as easy as they seem. Even these simple rules are not so simple. For example, consider the following rule. Many people fail to realize that this rule is just as valid as the pizza or hamburger rule above.

if p, then q

therefore, not p

Concrete version:

If I eat dinner, then I will have dessert

I did not have dessert

Therefore, I did not eat dinner

The simple fact is, it can be very difficult for people to apply rules of deductive logic correctly; as a result, they make many errors when trying to do so. Is this a deductively valid argument or not?

Students who like school study a lot

Students who study a lot get good grades

Jane does not like school

Therefore, Jane does not get good grades

Many people are surprised to discover that this is not a logically valid argument; the conclusion is not guaranteed to be true from the beginning statements. Although the first statement says that students who like school study a lot, it does NOT say that students who do not like school do not study a lot. In other words, it may very well be possible to study a lot without liking school. Even people who sometimes get problems like this right might not be using the rules of deductive reasoning. Instead, they might just be making judgments for examples they know, in this case, remembering instances of people who get good grades despite not liking school.

Making deductive reasoning even more difficult is the fact that there are two important properties that an argument may have. One, it can be valid or invalid (meaning that the conclusion does or does not follow logically from the statements leading up to it). Two, an argument (or more correctly, its conclusion) can be true or false. Here is an example of an argument that is logically valid, but has a false conclusion (at least we think it is false).

Either you are eleven feet tall or the Grand Canyon was created by a spaceship crashing into the earth.

You are not eleven feet tall

Therefore the Grand Canyon was created by a spaceship crashing into the earth

This argument has the exact same form as the pizza or hamburger argument above, making it is deductively valid. The conclusion is so false, however, that it is absurd (of course, the reason the conclusion is false is that the first statement is false). When people are judging arguments, they tend to not observe the difference between deductive validity and the empirical truth of statements or conclusions. If the elements of an argument happen to be true, people are likely to judge the argument logically valid; if the elements are false, they will very likely judge it invalid (Markovits & Bouffard-Bouchard, 1992; Moshman & Franks, 1986). Thus, it seems a stretch to say that people are using these logical rules to judge the validity of arguments. Many psychologists believe that most people actually have very limited deductive reasoning skills (Johnson-Laird, 1999). They argue that when faced with a problem for which deductive logic is required, people resort to some simpler technique, such as matching terms that appear in the statements and the conclusion (Evans, 1982). This might not seem like a problem, but what if reasoners believe that the elements are true and they happen to be wrong; they will would believe that they are using a form of reasoning that guarantees they are correct and yet be wrong.

deductive reasoning : a type of reasoning in which the conclusion is guaranteed to be true any time the statements leading up to it are true

argument : a set of statements in which the beginning statements lead to a conclusion

deductively valid argument : an argument for which true beginning statements guarantee that the conclusion is true

Inductive reasoning and judgment

Every day, you make many judgments about the likelihood of one thing or another. Whether you realize it or not, you are practicing inductive reasoning on a daily basis. In inductive reasoning arguments, a conclusion is likely whenever the statements preceding it are true. The first thing to notice about inductive reasoning is that, by definition, you can never be sure about your conclusion; you can only estimate how likely the conclusion is. Inductive reasoning may lead you to focus on Memory Encoding and Recoding when you study for the exam, but it is possible the instructor will ask more questions about Memory Retrieval instead. Unlike deductive reasoning, the conclusions you reach through inductive reasoning are only probable, not certain. That is why scientists consider inductive reasoning weaker than deductive reasoning. But imagine how hard it would be for us to function if we could not act unless we were certain about the outcome.

Inductive reasoning can be represented as logical arguments consisting of statements and a conclusion, just as deductive reasoning can be. In an inductive argument, you are given some statements and a conclusion (or you are given some statements and must draw a conclusion). An argument is inductively strong if the conclusion would be very probable whenever the statements are true. So, for example, here is an inductively strong argument:

- Statement #1: The forecaster on Channel 2 said it is going to rain today.

- Statement #2: The forecaster on Channel 5 said it is going to rain today.

- Statement #3: It is very cloudy and humid.

- Statement #4: You just heard thunder.

- Conclusion (or judgment): It is going to rain today.