How to Write a Bibliography for a Research Paper

Do not try to “wow” your instructor with a long bibliography when your instructor requests only a works cited page. It is tempting, after doing a lot of work to research a paper, to try to include summaries on each source as you write your paper so that your instructor appreciates how much work you did. That is a trap you want to avoid. MLA style, the one that is most commonly followed in high schools and university writing courses, dictates that you include only the works you actually cited in your paper—not all those that you used.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, assembling bibliographies and works cited.

- If your assignment calls for a bibliography, list all the sources you consulted in your research.

- If your assignment calls for a works cited or references page, include only the sources you quote, summarize, paraphrase, or mention in your paper.

- If your works cited page includes a source that you did not cite in your paper, delete it.

- All in-text citations that you used at the end of quotations, summaries, and paraphrases to credit others for their ideas,words, and work must be accompanied by a cited reference in the bibliography or works cited. These references must include specific information about the source so that your readers can identify precisely where the information came from.The citation entries on a works cited page typically include the author’s name, the name of the article, the name of the publication, the name of the publisher (for books), where it was published (for books), and when it was published.

The good news is that you do not have to memorize all the many ways the works cited entries should be written. Numerous helpful style guides are available to show you the information that should be included, in what order it should appear, and how to format it. The format often differs according to the style guide you are using. The Modern Language Association (MLA) follows a particular style that is a bit different from APA (American Psychological Association) style, and both are somewhat different from the Chicago Manual of Style (CMS). Always ask your teacher which style you should use.

A bibliography usually appears at the end of a paper on its own separate page. All bibliography entries—books, periodicals, Web sites, and nontext sources such radio broadcasts—are listed together in alphabetical order. Books and articles are alphabetized by the author’s last name.

Most teachers suggest that you follow a standard style for listing different types of sources. If your teacher asks you to use a different form, however, follow his or her instructions. Take pride in your bibliography. It represents some of the most important work you’ve done for your research paper—and using proper form shows that you are a serious and careful researcher.

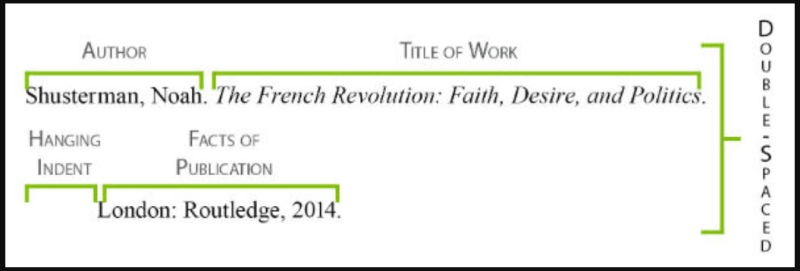

Bibliography Entry for a Book

A bibliography entry for a book begins with the author’s name, which is written in this order: last name, comma, first name, period. After the author’s name comes the title of the book. If you are handwriting your bibliography, underline each title. If you are working on a computer, put the book title in italicized type. Be sure to capitalize the words in the title correctly, exactly as they are written in the book itself. Following the title is the city where the book was published, followed by a colon, the name of the publisher, a comma, the date published, and a period. Here is an example:

Format : Author’s last name, first name. Book Title. Place of publication: publisher, date of publication.

- A book with one author : Hartz, Paula. Abortion: A Doctor’s Perspective, a Woman’s Dilemma . New York: Donald I. Fine, Inc., 1992.

- A book with two or more authors : Landis, Jean M. and Rita J. Simon. Intelligence: Nature or Nurture? New York: HarperCollins, 1998.

Bibliography Entry for a Periodical

A bibliography entry for a periodical differs slightly in form from a bibliography entry for a book. For a magazine article, start with the author’s last name first, followed by a comma, then the first name and a period. Next, write the title of the article in quotation marks, and include a period (or other closing punctuation) inside the closing quotation mark. The title of the magazine is next, underlined or in italic type, depending on whether you are handwriting or using a computer, followed by a period. The date and year, followed by a colon and the pages on which the article appeared, come last. Here is an example:

Format: Author’s last name, first name. “Title of the Article.” Magazine. Month and year of publication: page numbers.

- Article in a monthly magazine : Crowley, J.E.,T.E. Levitan and R.P. Quinn.“Seven Deadly Half-Truths About Women.” Psychology Today March 1978: 94–106.

- Article in a weekly magazine : Schwartz, Felice N.“Management,Women, and the New Facts of Life.” Newsweek 20 July 2006: 21–22.

- Signed newspaper article : Ferraro, Susan. “In-law and Order: Finding Relative Calm.” The Daily News 30 June 1998: 73.

- Unsigned newspaper article : “Beanie Babies May Be a Rotten Nest Egg.” Chicago Tribune 21 June 2004: 12.

Bibliography Entry for a Web Site

For sources such as Web sites include the information a reader needs to find the source or to know where and when you found it. Always begin with the last name of the author, broadcaster, person you interviewed, and so on. Here is an example of a bibliography for a Web site:

Format : Author.“Document Title.” Publication or Web site title. Date of publication. Date of access.

Example : Dodman, Dr. Nicholas. “Dog-Human Communication.” Pet Place . 10 November 2006. 23 January 2014 < http://www.petplace.com/dogs/dog-human-communication-2/page1.aspx >

After completing the bibliography you can breathe a huge sigh of relief and pat yourself on the back. You probably plan to turn in your work in printed or handwritten form, but you also may be making an oral presentation. However you plan to present your paper, do your best to show it in its best light. You’ve put a great deal of work and thought into this assignment, so you want your paper to look and sound its best. You’ve completed your research paper!

Back to How To Write A Research Paper .

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

- Try for free

How to Write a Bibliography (MLA, APA Examples)

Learn how to easily write a bibliography by following the format outlined in this article.

This resource will help your students properly cite different resources in the bibliography of a research paper, and how to format those citations, for books, encyclopedias, films, websites, and people.

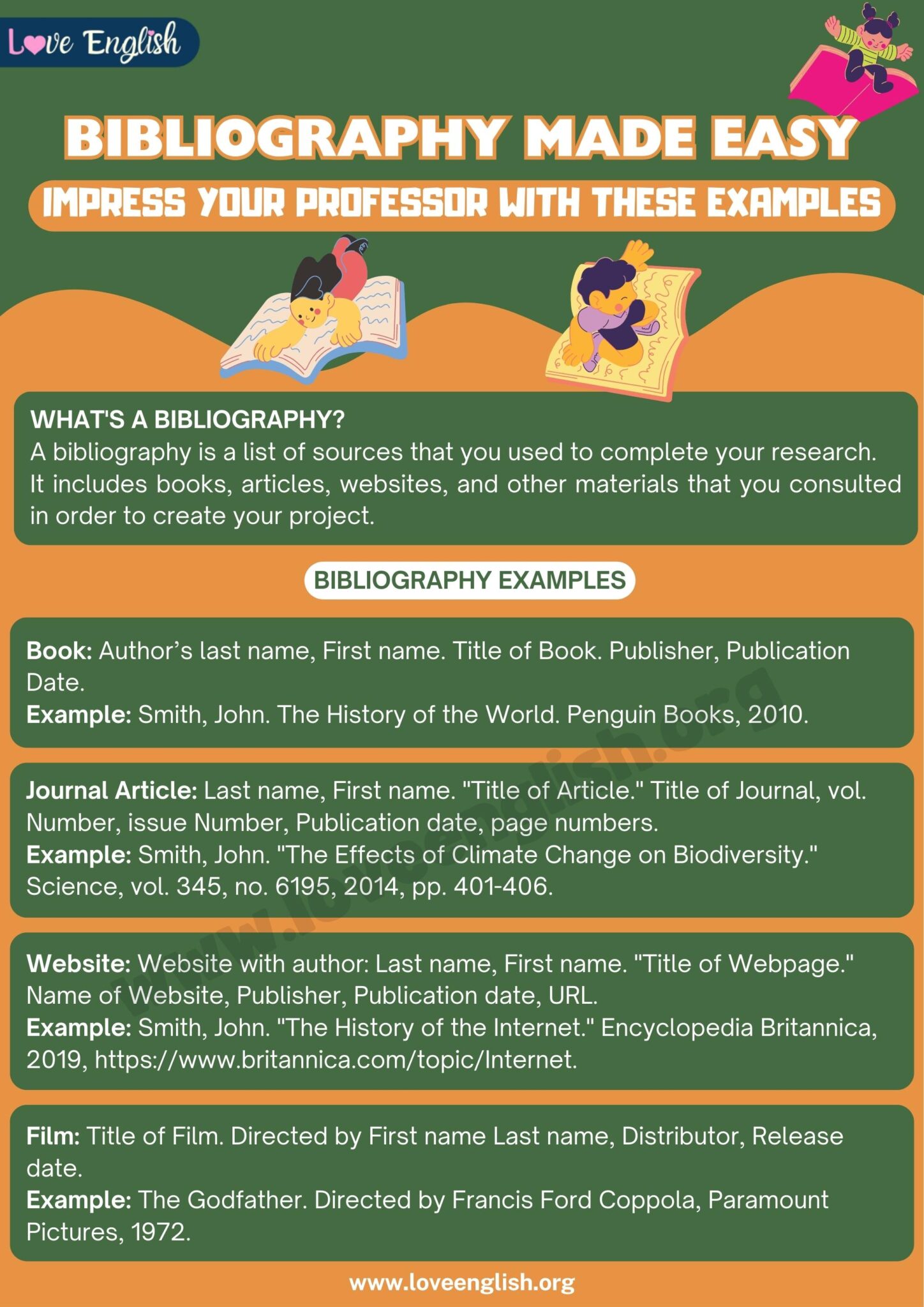

What is a bibliography?

According to Infoplease.com, A bibliography is a list of the types of sources you used to get information for your report. It is included at the end of your report, on the last page (or last few pages).

What are the types of bibliography styles (MLA, APA, etc.)?

The 3 most common bibliography/citation styles are:

- MLA Style: The Modern Language Association works cited page style

- APA Style: The American Psychological Association style

- Chicago Style: The bibliography style defined by the Chicago Manual of Style

We’ll give examples of how to create bibliography entries in various styles further down in this article.

What sources do you put in a bibliography?

An annotated bibliography should include a reference list of any sources you use in writing a research paper. Any printed sources from which you use a text citation, including books, websites, newspaper articles, journal articles, academic writing, online sources (such as PDFs), and magazines should be included in a reference list. In some cases, you may need or want to cite conversations or interviews, works of art, visual works such as movies, television shows, or documentaries - these (and many others) can also be included in a reference list.

How to get started writing your bibliography

You will find it easier to prepare your MLA, APA, or Chicago annotated bibliography if you keep track of each book, encyclopedia, journal article, webpage or online source you use as you are reading and taking notes. Start a preliminary, or draft, bibliography by listing on a separate sheet of paper all your sources. Note down the full title, author’s last name, place of publication, web address, publisher, and date of publication for each source.

Haven't started your paper yet and need an outline? These sample essay outlines include a research paper outline from an actual student paper.

How to write a bibliography step-by-step (with examples)

General Format: Author (last name first). Title of the book. Publisher, Date of publication.

MLA Style: Sibley, David Allen. What It’s Like to Be a Bird. From Flying to Nesting, Eating to Singing, What Birds Are Doing, and Why. Alfred A. Knopf, 2020.

APA Style: Sibley, D.A. (2020). What It’s Like to Be a Bird. From Flying to Nesting, Eating to Singing, What Birds Are Doing, and Why . Alfred A. Knopf.

Notes: Use periods, not commas, to separate the data in the entry. Use a hanging indent if the entry is longer than one line. For APA style, do not use the full author’s first name.

Websites or webpages:

MLA Style: The SB Nation Family of Sites. Pension Plan Puppets: A Toronto Maple Leafs Blog, 2022, www.pensionplanpuppets.com. Accessed 15 Feb. 2022.

APA Style: American Heart Association. (2022, April 11). How to keep your dog’s heart healthy. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2022/04/11/how-to-keep-your-dogs-heart-healthy

Online news article from a newspaper site:

APA Style: Duehren, A. (2022, April 9). Janet Yellen faces challenge to keep pressure on Russia. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/janet-yellen-faces-challenge-to-keep-pressure-on-russia-while-addressing-global-consequences-11650366000

Print journal articles:

MLA Style: Booch, Grady. "Patterns in Object-Oriented Design." IEEE Software Engineering, vol. 6, no. 6, 2006, pp. 31-50.

APA Style: Booch, G. (2006). Patterns in object-oriented design. IEEE Software Engineering, 6(6), 31–50.

Note: It is suggested that you include a DOI and a webpage address when referencing either a printed journal article, and electronic journal article, or an journal article that appears in both formats.

MLA Style: Gamma, Eric, and Peter A. Coad. “Exceptions to the Unified Modeling Language in Python Patterns.” IEEE Software Engineering, vol. 2, no. 6, 8 Mar. 2006, pp. 190-194. O’Reilly Software Engineering Library, https://doi.org/10.1006/se.20061. Accessed 26 May 2009.

APA Style: Masters, H., Barron, J., & Chanda, L. (2017). Motivational interviewing techniques for adolescent populations in substance abuse counseling. NAADAC Notes, 7(8), 7–13. https://www.naadac.com/notes/adolescent-techniques

ML:A Style: @Grady_Booch. “That’s a bold leap over plain old battery power cars.” Twitter, 13 Mar. 2013, 12:06 p.m., https://twitter.com/Grady_Booch/status/1516379006727188483.

APA Style: Westborough Library [@WestboroughLib]. (2022, April 12). Calling all 3rd through 5th grade kids! Join us for the Epic Writing Showdown! Winner receives a prize! Space is limited so register, today. loom.ly/ypaTG9Q [Tweet; thumbnail link to article]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/WestboroughLib/status/1516373550415896588.

Print magazine articles:

General format: Author (last name first), "Article Title." Name of magazine. Volume number, (Date): page numbers.

MLA Style: Stiteler, Sharon. "Tracking Red-Breasted Grosbeak Migration." Minnesota Bird Journal, 7 Sept. 2019, pp. 7-11.

APA Style: Jordan, Jennifer, "Filming at the Top of the World." Museum of Science Magazine. Volume 47, No. 1, (Winter 1998): p. 11.

Print newspaper articles:

General format: Author (last name first), "Article Title." Name of newspaper, city, state of publication. (date): edition if available, section, page number(s).

MLA Style: Adelman, Martin. "Augustus Announces Departure from City Manager Post." New York Times, late ed., 15 February 2020, p. A1

APA Style: Adelman, M. (2020, February 15). Augustus announced departure from city manager post. New York Times, A1.

Encyclopedias:

General Format: Encyclopedia Title, Edition Date. Volume Number, "Article Title," page numbers.

MLA Style: “Gorillas.” The Encyclopedia Brittanica. 15th ed. 2010.

APA Style: Encyclopedia Brittanica, Inc. (1997.) Gorillas. In The Encyclopedia Brittanica (15th ed., pp. 50-51). Encyclopedia Brittanica, Inc.

Personal interviews:

General format: Full name (last name first). Personal Interview. (Occupation.) Date of interview.

MLA Style: Smithfield, Joseph. Personal interview. 19 May 2014.

APA Style: APA does not require a formal citation for a personal interview. Published interviews from other sources should be cited accordingly.

Films and movies:

General format: Title, Director, Distributor, Year.

MLA Style: Fury. Directed by David Ayer, performances by Brad Pitt, Shia LaBeouf, Jon Bernthal, Sony Pictures, 2014.

APA Style: Ayer, D. (Director). (2014). Fury [Film]. Sony Pictures.

Featured High School Resources

Related Resources

About the author

TeacherVision Editorial Staff

The TeacherVision editorial team is comprised of teachers, experts, and content professionals dedicated to bringing you the most accurate and relevant information in the teaching space.

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

FREE Poetry Worksheet Bundle! Perfect for National Poetry Month.

How To Write a Bibliography (Three Styles, Plus Examples)

Give credit where credit is due.

Writing a research paper involves a lot of work. Students need to consult a variety of sources to gather reliable information and ensure their points are well supported. Research papers include a bibliography, which can be a little tricky for students. Learn how to write a bibliography in multiple styles and find basic examples below.

IMPORTANT: Each style guide has its own very specific rules, and they often conflict with one another. Additionally, each type of reference material has many possible formats, depending on a variety of factors. The overviews shown here are meant to guide students in writing basic bibliographies, but this information is by no means complete. Students should always refer directly to the preferred style guide to ensure they’re using the most up-to-date formats and styles.

What is a bibliography?

When you’re researching a paper, you’ll likely consult a wide variety of sources. You may quote some of these directly in your work, summarize some of the points they make, or simply use them to further the knowledge you need to write your paper. Since these ideas are not your own, it’s vital to give credit to the authors who originally wrote them. This list of sources, organized alphabetically, is called a bibliography.

A bibliography should include all the materials you consulted in your research, even if you don’t quote directly from them in your paper. These resources could include (but aren’t limited to):

- Books and e-books

- Periodicals like magazines or newspapers

- Online articles or websites

- Primary source documents like letters or official records

Bibliography vs. References

These two terms are sometimes used interchangeably, but they actually have different meanings. As noted above, a bibliography includes all the materials you used while researching your paper, whether or not you quote from them or refer to them directly in your writing.

A list of references only includes the materials you cite throughout your work. You might use direct quotes or summarize the information for the reader. Either way, you must ensure you give credit to the original author or document. This section can be titled “List of Works Cited” or simply “References.”

Your teacher may specify whether you should include a bibliography or a reference list. If they don’t, consider choosing a bibliography, to show all the works you used in researching your paper. This can help the reader see that your points are well supported, and allow them to do further reading on their own if they’re interested.

Bibliography vs. Citations

Citations refer to direct quotations from a text, woven into your own writing. There are a variety of ways to write citations, including footnotes and endnotes. These are generally shorter than the entries in a reference list or bibliography. Learn more about writing citations here.

What does a bibliography entry include?

Depending on the reference material, bibliography entries include a variety of information intended to help a reader locate the material if they want to refer to it themselves. These entries are listed in alphabetical order, and may include:

- Author/s or creator/s

- Publication date

- Volume and issue numbers

- Publisher and publication city

- Website URL

These entries don’t generally need to include specific page numbers or locations within the work (except for print magazine or journal articles). That type of information is usually only needed in a footnote or endnote citation.

What are the different bibliography styles?

In most cases, writers use one of three major style guides: APA (American Psychological Association), MLA (Modern Language Association), or The Chicago Manual of Style . There are many others as well, but these three are the most common choices for K–12 students.

Many teachers will state their preference for one style guide over another. If they don’t, you can choose your own preferred style. However, you should also use that guide for your entire paper, following their recommendations for punctuation, grammar, and more. This will ensure you are consistent throughout.

Below, you’ll learn how to write a simple bibliography using each of the three major style guides. We’ve included details for books and e-books, periodicals, and electronic sources like websites and videos. If the reference material type you need to include isn’t shown here, refer directly to the style guide you’re using.

APA Style Bibliography and Examples

Source: Verywell Mind

Technically, APA style calls for a list of references instead of a bibliography. If your teacher requires you to use the APA style guide , you can limit your reference list only to items you cite throughout your work.

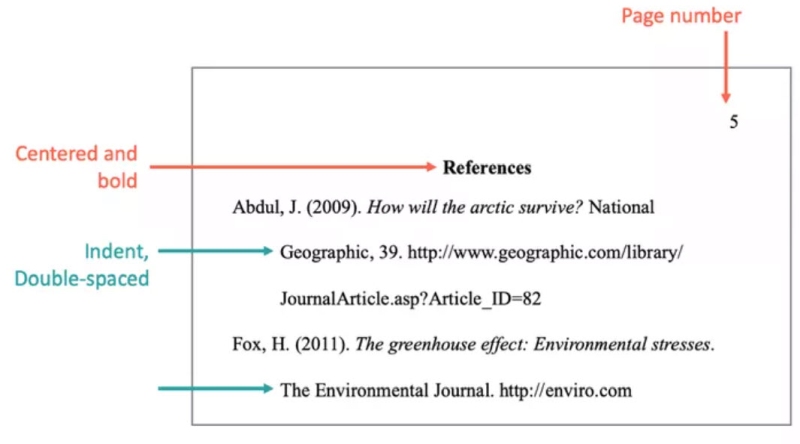

How To Write a Bibliography (References) Using APA Style

Here are some general notes on writing an APA reference list:

- Title your bibliography section “References” and center the title on the top line of the page.

- Do not center your references; they should be left-aligned. For longer items, subsequent lines should use a hanging indent of 1/2 inch.

- Include all types of resources in the same list.

- Alphabetize your list by author or creator, last name first.

- Do not spell out the author/creator’s first or middle name; only use their initials.

- If there are multiple authors/creators, use an ampersand (&) before the final author/creator.

- Place the date in parentheses.

- Capitalize only the first word of the title and subtitle, unless the word would otherwise be capitalized (proper names, etc.).

- Italicize the titles of books, periodicals, or videos.

- For websites, include the full site information, including the http:// or https:// at the beginning.

Books and E-Books APA Bibliography Examples

For books, APA reference list entries use this format (only include the publisher’s website for e-books).

Last Name, First Initial. Middle Initial. (Publication date). Title with only first word capitalized . Publisher. Publisher’s website

- Wynn, S. (2020). City of London at war 1939–45 . Pen & Sword Military. https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/City-of-London-at-War-193945-Paperback/p/17299

Periodical APA Bibliography Examples

For journal or magazine articles, use this format. If you viewed the article online, include the URL at the end of the citation.

Last Name, First Initial. Middle Initial. (Publication date). Title of article. Magazine or Journal Title (Volume number) Issue number, page numbers. URL

- Bell, A. (2009). Landscapes of fear: Wartime London, 1939–1945. Journal of British Studies (48) 1, 153–175. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25482966

Here’s the format for newspapers. For print editions, include the page number/s. For online articles, include the full URL.

Last Name, First Initial. Middle Initial. (Year, Month Date) Title of article. Newspaper title. Page number/s. URL

- Blakemore, E. (2022, November 12) Researchers track down two copies of fossil destroyed by the Nazis. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/2022/11/12/ichthyosaur-fossil-images-discovered/

Electronic APA Bibliography Examples

For articles with a specific author on a website, use this format.

Last Name, First Initial. Middle Initial. (Year, Month Date). Title . Site name. URL

- Wukovits, J. (2023, January 30). A World War II survivor recalls the London Blitz . British Heritage . https://britishheritage.com/history/world-war-ii-survivor-london-blitz

When an online article doesn’t include a specific author or date, list it like this:

Title . (Year, Month Date). Site name. Retrieved Month Date, Year, from URL

- Growing up in the Second World War . (n.d.). Imperial War Museums. Retrieved May 12, 2023, from https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/growing-up-in-the-second-world-war

When you need to list a YouTube video, use the name of the account that uploaded the video, and format it like this:

Name of Account. (Upload year, month day). Title [Video]. YouTube. URL

- War Stories. (2023, January 15). How did London survive the Blitz during WW2? | Cities at war: London | War stories [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/uwY6JlCvbxc

For more information on writing APA bibliographies, see the APA Style Guide website.

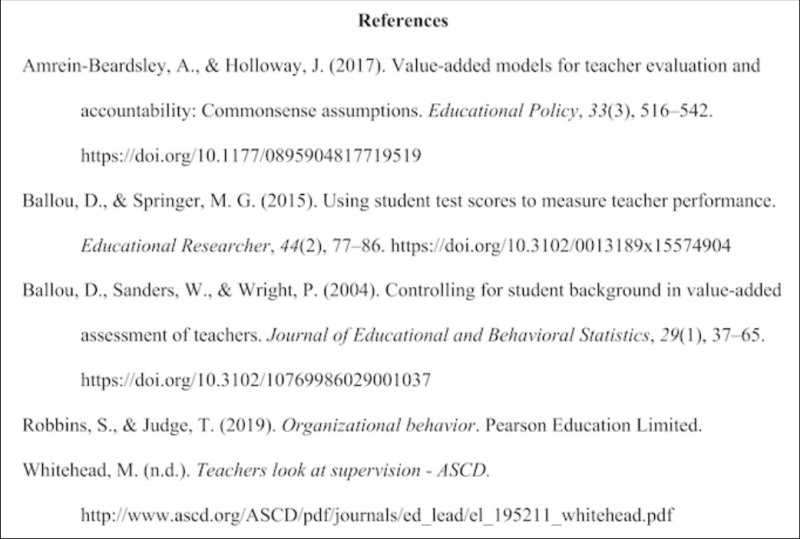

APA Bibliography (Reference List) Example Pages

Source: Simply Psychology

More APA example pages:

- Western Australia Library Services APA References Example Page

- Ancilla College APA References Page Example

- Scribbr APA References Page Example

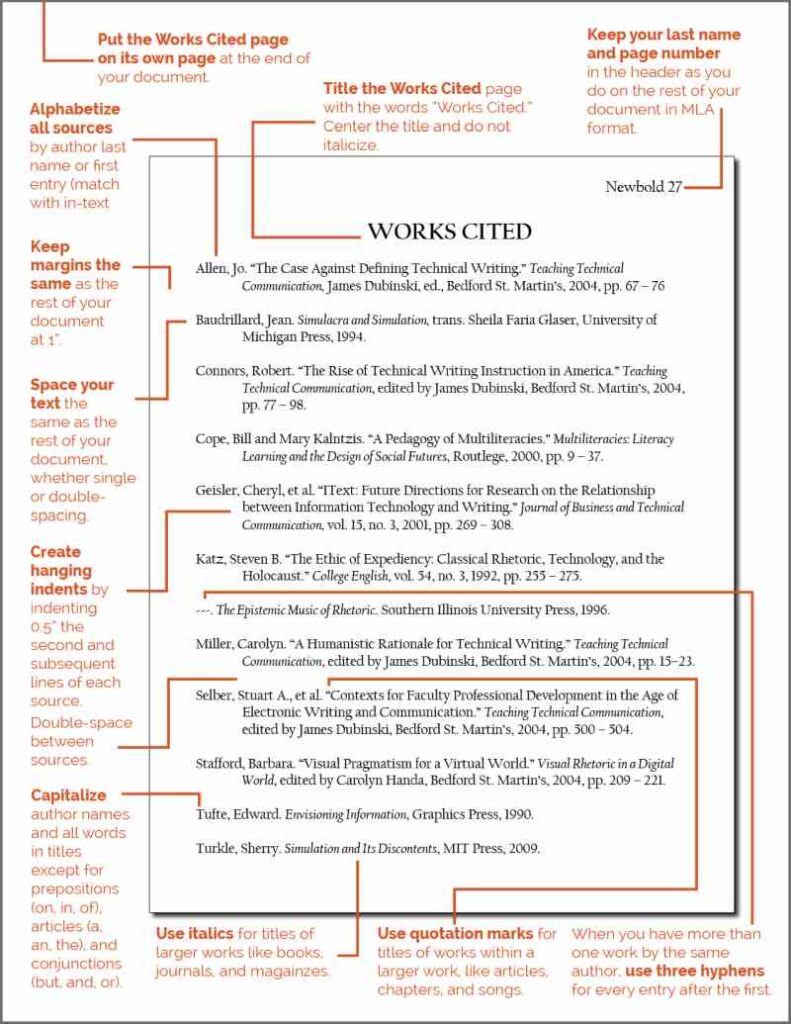

MLA Style Bibliography Examples

Source: PressBooks

MLA style calls for a Works Cited section, which includes all materials quoted or referred to in your paper. You may also include a Works Consulted section, including other reference sources you reviewed but didn’t directly cite. Together, these constitute a bibliography. If your teacher requests an MLA Style Guide bibliography, ask if you should include Works Consulted as well as Works Cited.

How To Write a Bibliography (Works Cited and Works Consulted) in MLA Style

For both MLA Works Cited and Works Consulted sections, use these general guidelines:

- Start your Works Cited list on a new page. If you include a Works Consulted list, start that on its own new page after the Works Cited section.

- Center the title (Works Cited or Works Consulted) in the middle of the line at the top of the page.

- Align the start of each source to the left margin, and use a hanging indent (1/2 inch) for the following lines of each source.

- Alphabetize your sources using the first word of the citation, usually the author’s last name.

- Include the author’s full name as listed, last name first.

- Capitalize titles using the standard MLA format.

- Leave off the http:// or https:// at the beginning of a URL.

Books and E-Books MLA Bibliography Examples

For books, MLA reference list entries use this format. Add the URL at the end for e-books.

Last Name, First Name Middle Name. Title . Publisher, Date. URL

- Wynn, Stephen. City of London at War 1939–45 . Pen & Sword Military, 2020. www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/City-of-London-at-War-193945-Paperback/p/17299

Periodical MLA Bibliography Examples

Here’s the style format for magazines, journals, and newspapers. For online articles, add the URL at the end of the listing.

For magazines and journals:

Last Name, First Name. “Title: Subtitle.” Name of Journal , volume number, issue number, Date of Publication, First Page Number–Last Page Number.

- Bell, Amy. “Landscapes of Fear: Wartime London, 1939–1945.” Journal of British Studies , vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 153–175. www.jstor.org/stable/25482966

When citing newspapers, include the page number/s for print editions or the URL for online articles.

Last Name, First Name. “Title of article.” Newspaper title. Page number/s. Year, month day. Page number or URL

- Blakemore, Erin. “Researchers Track Down Two Copies of Fossil Destroyed by the Nazis.” The Washington Post. 2022, Nov. 12. www.washingtonpost.com/science/2022/11/12/ichthyosaur-fossil-images-discovered/

Electronic MLA Bibliography Examples

Last Name, First Name. Year. “Title.” Month Day, Year published. URL

- Wukovits, John. 2023. “A World War II Survivor Recalls the London Blitz.” January 30, 2023. https://britishheritage.com/history/world-war-ii-survivor-london-blitz

Website. n.d. “Title.” Accessed Day Month Year. URL.

- Imperial War Museum. n.d. “Growing Up in the Second World War.” Accessed May 9, 2023. https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/growing-up-in-the-second-world-war.

Here’s how to list YouTube and other online videos.

Creator, if available. “Title of Video.” Website. Uploaded by Username, Day Month Year. URL.

- “How did London survive the Blitz during WW2? | Cities at war: London | War stories.” YouTube . Uploaded by War Stories, 15 Jan. 2023. youtu.be/uwY6JlCvbxc.

For more information on writing MLA style bibliographies, see the MLA Style website.

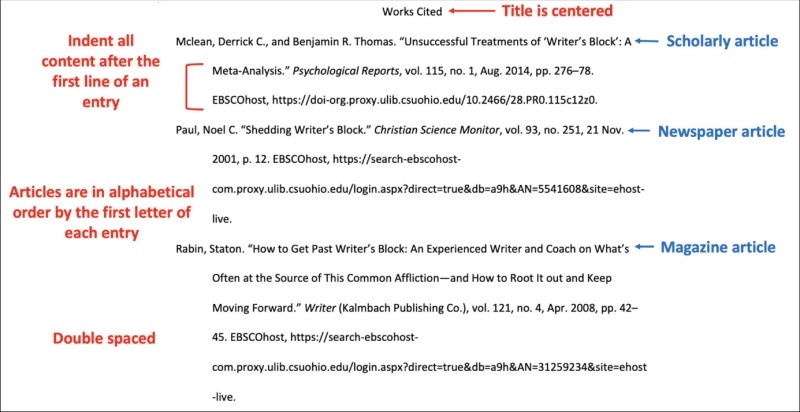

MLA Bibliography (Works Cited) Example Pages

Source: The Visual Communication Guy

More MLA example pages:

- Writing Commons Sample Works Cited Page

- Scribbr MLA Works Cited Sample Page

- Montana State University MLA Works Cited Page

Chicago Manual of Style Bibliography Examples

The Chicago Manual of Style (sometimes called “Turabian”) actually has two options for citing reference material : Notes and Bibliography and Author-Date. Regardless of which you use, you’ll need a complete detailed list of reference items at the end of your paper. The examples below demonstrate how to write that list.

How To Write a Bibliography Using The Chicago Manual of Style

Source: South Texas College

Here are some general notes on writing a Chicago -style bibliography:

- You may title it “Bibliography” or “References.” Center this title at the top of the page and add two blank lines before the first entry.

- Left-align each entry, with a hanging half-inch indent for subsequent lines of each entry.

- Single-space each entry, with a blank line between entries.

- Include the “http://” or “https://” at the beginning of URLs.

Books and E-Books Chicago Manual of Style Bibliography Examples

For books, Chicago -style reference list entries use this format. (For print books, leave off the information about how the book was accessed.)

Last Name, First Name Middle Name. Title . City of Publication: Publisher, Date. How e-book was accessed.

- Wynn, Stephen. City of London at War 1939–45 . Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military, 2020. Kindle edition.

Periodical Chicago Manual of Style Bibliography Examples

For journal and magazine articles, use this format.

Last Name, First Name. Year of Publication. “Title: Subtitle.” Name of Journal , Volume Number, issue number, First Page Number–Last Page Number. URL.

- Bell, Amy. 2009. “Landscapes of Fear: Wartime London, 1939–1945.” Journal of British Studies, 48 no. 1, 153–175. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25482966.

When citing newspapers, include the URL for online articles.

Last Name, First Name. Year of Publication. “Title: Subtitle.” Name of Newspaper , Month day, year. URL.

- Blakemore, Erin. 2022. “Researchers Track Down Two Copies of Fossil Destroyed by the Nazis.” The Washington Post , November 12, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/2022/11/12/ichthyosaur-fossil-images-discovered/.

Electronic Chicago Manual of Style Bibliography Examples

Last Name, First Name Middle Name. “Title.” Site Name . Year, Month Day. URL.

- Wukovits, John. “A World War II Survivor Recalls the London Blitz.” British Heritage. 2023, Jan. 30. britishheritage.com/history/world-war-ii-survivor-london-blitz.

“Title.” Site Name . URL. Accessed Day Month Year.

- “Growing Up in the Second World War.” Imperial War Museums . www.iwm.org.uk/history/growing-up-in-the-second-world-war. Accessed May 9, 2023.

Creator or Username. “Title of Video.” Website video, length. Month Day, Year. URL.

- War Stories. “How Did London Survive the Blitz During WW2? | Cities at War: London | War Stories.” YouTube video, 51:25. January 15, 2023. https://youtu.be/uwY6JlCvbxc.

For more information on writing Chicago -style bibliographies, see the Chicago Manual of Style website.

Chicago Manual of Style Bibliography Example Pages

Source: Chicago Manual of Style

More Chicago example pages:

- Scribbr Chicago Style Bibliography Example

- Purdue Online Writing Lab CMOS Bibliography Page

- Bibcitation Sample Chicago Bibliography

Now that you know how to write a bibliography, take a look at the Best Websites for Teaching & Learning Writing .

Plus, get all the latest teaching tips and ideas when you sign up for our free newsletters .

You Might Also Like

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Referencing

A Quick Guide to Harvard Referencing | Citation Examples

Published on 14 February 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 15 September 2023.

Referencing is an important part of academic writing. It tells your readers what sources you’ve used and how to find them.

Harvard is the most common referencing style used in UK universities. In Harvard style, the author and year are cited in-text, and full details of the source are given in a reference list .

Harvard Reference Generator

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Harvard in-text citation, creating a harvard reference list, harvard referencing examples, referencing sources with no author or date, frequently asked questions about harvard referencing.

A Harvard in-text citation appears in brackets beside any quotation or paraphrase of a source. It gives the last name of the author(s) and the year of publication, as well as a page number or range locating the passage referenced, if applicable:

Note that ‘p.’ is used for a single page, ‘pp.’ for multiple pages (e.g. ‘pp. 1–5’).

An in-text citation usually appears immediately after the quotation or paraphrase in question. It may also appear at the end of the relevant sentence, as long as it’s clear what it refers to.

When your sentence already mentions the name of the author, it should not be repeated in the citation:

Sources with multiple authors

When you cite a source with up to three authors, cite all authors’ names. For four or more authors, list only the first name, followed by ‘ et al. ’:

Sources with no page numbers

Some sources, such as websites , often don’t have page numbers. If the source is a short text, you can simply leave out the page number. With longer sources, you can use an alternate locator such as a subheading or paragraph number if you need to specify where to find the quote:

Multiple citations at the same point

When you need multiple citations to appear at the same point in your text – for example, when you refer to several sources with one phrase – you can present them in the same set of brackets, separated by semicolons. List them in order of publication date:

Multiple sources with the same author and date

If you cite multiple sources by the same author which were published in the same year, it’s important to distinguish between them in your citations. To do this, insert an ‘a’ after the year in the first one you reference, a ‘b’ in the second, and so on:

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

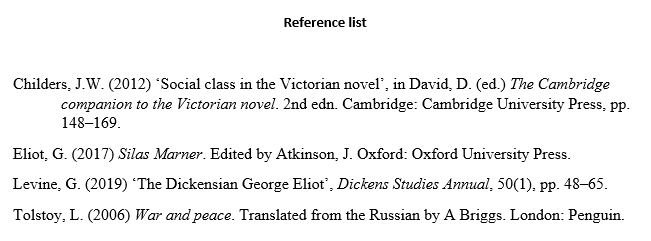

A bibliography or reference list appears at the end of your text. It lists all your sources in alphabetical order by the author’s last name, giving complete information so that the reader can look them up if necessary.

The reference entry starts with the author’s last name followed by initial(s). Only the first word of the title is capitalised (as well as any proper nouns).

Sources with multiple authors in the reference list

As with in-text citations, up to three authors should be listed; when there are four or more, list only the first author followed by ‘ et al. ’:

Reference list entries vary according to source type, since different information is relevant for different sources. Formats and examples for the most commonly used source types are given below.

- Entire book

- Book chapter

- Translated book

- Edition of a book

Journal articles

- Print journal

- Online-only journal with DOI

- Online-only journal with no DOI

- General web page

- Online article or blog

- Social media post

Sometimes you won’t have all the information you need for a reference. This section covers what to do when a source lacks a publication date or named author.

No publication date

When a source doesn’t have a clear publication date – for example, a constantly updated reference source like Wikipedia or an obscure historical document which can’t be accurately dated – you can replace it with the words ‘no date’:

Note that when you do this with an online source, you should still include an access date, as in the example.

When a source lacks a clearly identified author, there’s often an appropriate corporate source – the organisation responsible for the source – whom you can credit as author instead, as in the Google and Wikipedia examples above.

When that’s not the case, you can just replace it with the title of the source in both the in-text citation and the reference list:

Harvard referencing uses an author–date system. Sources are cited by the author’s last name and the publication year in brackets. Each Harvard in-text citation corresponds to an entry in the alphabetised reference list at the end of the paper.

Vancouver referencing uses a numerical system. Sources are cited by a number in parentheses or superscript. Each number corresponds to a full reference at the end of the paper.

A Harvard in-text citation should appear in brackets every time you quote, paraphrase, or refer to information from a source.

The citation can appear immediately after the quotation or paraphrase, or at the end of the sentence. If you’re quoting, place the citation outside of the quotation marks but before any other punctuation like a comma or full stop.

In Harvard referencing, up to three author names are included in an in-text citation or reference list entry. When there are four or more authors, include only the first, followed by ‘ et al. ’

Though the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, there is a difference in meaning:

- A reference list only includes sources cited in the text – every entry corresponds to an in-text citation .

- A bibliography also includes other sources which were consulted during the research but not cited.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, September 15). A Quick Guide to Harvard Referencing | Citation Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/referencing/harvard-style/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, harvard in-text citation | a complete guide & examples, harvard style bibliography | format & examples, referencing books in harvard style | templates & examples, scribbr apa citation checker.

An innovative new tool that checks your APA citations with AI software. Say goodbye to inaccurate citations!

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

31 Bibliography

Annotated bibliography.

A bibliography is an alphabetized list of sources showing the author, date, and publication information for each source.

An annotation is like a note; it’s a brief paragraph that explains what the writer learned from the source.

Annotated bibliographies combine bibliographies and brief notes about the sources.

Writers often create annotated bibliographies as a part of a research project, as a means of recording their thoughts and deciding which sources to actually use to support the purpose of their research. Some writers include annotated bibliographies at the end of a research paper as a way of offering their insights about the source’s usability to their readers.

Instructors in college often assign annotated bibliographies as a means of helping students think through their source’s quality and appropriateness to their research question or topic. (23)

Formatting the Annotated Bibliography

The citations (bibliographic information – title, date, author, publisher, etc.) in the annotated bibliography are formatted using the particular style manual (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.) that your discipline requires.

Annotations are written in paragraph form, usually 3-7 sentences (or 80-200 words). Depending on your assignment your annotations will generally include the following:

- Summary: Summarize the information given in the source. Note the intended audience. What are the main arguments? What is the point of this book or article? What topics are covered? If someone asked what this article/book is about, what would you say?

- Evaluate/Assess: Is this source credible? Who wrote it? What are their credentials? Who is the publisher? Is it a useful source? How does it compare with other sources in your bibliography? Is the information reliable? Is this source biased or objective? What is the goal of this source?

- Reflect/React: Once you’ve summarized and assessed a source, you need to ask how it fits into your research. State your reaction and any additional questions you have about the information in your source. Was this source helpful to you? How does it help you shape your argument? How can you use this source in your research project? Has it changed how you think about your topic? Compare each source to other sources in your annotated bibliography in terms of its usefulness and thoroughness in helping answer your research question. (24)

Annotated Bibliography Examples

In the following examples, the bold font indicates the reflection component of the annotation that is sometimes required in an assignment.

APA style 6 th edition for the journal citation:

Waite, L. J., Goldschneider, F. K., & Witsberger, C. (1986). Nonfamily living and the erosion of traditional family orientations among young adults. American Sociological Review , 51, 541-554.

The authors, researchers at the Rand Corporation and Brown University, use data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Young Women and Young Men to test their hypothesis that nonfamily living by young adults alters their attitudes, values, plans, and expectations, moving them away from their belief in traditional sex roles. They find their hypothesis strongly supported in young females, while the effects were fewer in studies of young males. Increasing the time away from parents before marrying increased individualism, self-sufficiency, and changes in attitudes about families. In contrast, an earlier study by Williams cited below shows no significant gender differences in sex role attitudes as a result of nonfamily living. (25)

MLA 8 style for a website citation:

Anderson, L.V. “Can You Libel Someone on Twitter?” Slate.com, The Slate Group, A Graham Holdings. Company, 26 Nov. 2012, http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/explainer/2012/11/libel_on_twitter_you_can_be_sued_for_libel_for_what_you_write_on_facebook.html . Accessed 2 Apr. 2018.

This article provides an overview of defamation law in the United States compared to the United Kingdom, in layman’s terms. It also explains how defamation law applies to social media platforms and individuals who use social media. Libelous comments posted on social media can be subject to lawsuit, depending on the content of the statement, and whether the person is a public or private figure. The article is found on the website, Slate.com, which is a web-based daily magazine that focuses on general interest topics. While the writer’s credentials are unavailable, she does thank Sandra S. Baron, Executive Director of the Media Law Resource Center and Jeff Hermes, director of the Digital Media Law Project for providing information. She also links to the United States laws that she cites. I would use the article to compare United States law to United Kingdom law and for background information. (1)

Information creation is a process. Scholars produce information in the forms of peer-reviewed journal articles, books, and conference presentations, to name a few. As a student researcher, you will be expected to create research projects such as essays, reports, visual presentations, and annotated bibliographies. Most scholarly writing makes an argument—whether it is to persuade your readers that your claim is true or to act on it. In order to create a sound argument, you must gather sources that will argue and counter-argue your claims.

When creating an argument, the researcher typically organizes their report or presentation with the claim/thesis at the beginning, which answers their research question. Then they provide reasons and supporting evidence to validate their claim. They acknowledge and respond to counter-arguments by citing sources that disagree with them, and refuting or conceding those counter-claims. Their conclusion restates their thesis and discusses why their research is important to the scholarly conversation, as well as potential areas for further research.

A Roman numeral outline is one way to organize your argument before you begin writing. It helps to identify sources for each section of your outline, so you know if you need further research to support your argument.

An annotated bibliography is one way to present research, and can be used as a cumulative assignment, or a precursor to your actual research paper. A good annotated bibliography will provide a variety of sources that met all your research needs—background, evidence, argument, and method. In other words, you should be able to take your annotated bibliography and write a complete research report based on those sources. (1)

Introduction to College Research Copyright © by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The Quintessence of Basic and Clinical Research and Scientific Publishing pp 657–665 Cite as

How to Create a Bibliography

- Rohan Reddy 4 ,

- Samuel Sorkhi 4 ,

- Saager Chawla 4 &

- Mahadevan Raj Rajasekaran 5

- First Online: 01 October 2023

618 Accesses

This chapter describes the fundamental principles and practices of referencing sources in scientific writing and publishing. Understanding plagiarism and improper referencing of the source material is paramount to producing original work that contains an authentic voice. Citing references helps authors to avoid plagiarism, give credit to the original author, and allow potential readers to refer to the legitimate sources and learn more information. Furthermore, quality references serve as an invaluable resource that can enlighten future research in a field. This chapter outlines fundamental aspects of referencing as well as how these sources are formatted as per recommended citation styles. Appropriate referencing is an important tool that can be utilized to develop the credibility of the author and the arguments presented. Additionally, online software can be useful in helping the author organize their sources and promote proper collaboration in scientific writing.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

AWELU (2022) The functions of references. Lund University. https://www.awelu.lu.se/referencing/the-functions-of-references/ . Accessed 28 Dec 2022

Masic I (2013) The importance of proper citation of references in biomedical articles. Acta Inform Med 21(3):148–155

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Neville C (2012) Referencing: principles, practice and problems. RGUHS J Pharm Sci 2(2):1–8

Google Scholar

Horkoff T (2015) Writing for success 1st Canadian edition: BCcampus. Chapter 7. Sources: choosing the right ones. https://opentextbc.ca/writingforsuccess/chapter/chapter-7-sources-choosing-the-right-ones/ . Accessed 28 Dec 2022

A guide to database and catalog searching: bibliographic elements. Northwestern State University. https://libguides.nsula.edu/howtosearch/bibelements . Updated 5 Aug 2021; Accessed 28 Dec 2022

Research process: step 7: citing and keeping track of sources. University of Rio Grande. https://libguides.rio.edu/c.php?g=620382&p=4320145 . Updated 12 Dec 2022; Accessed 28 Dec 2022

Pears R, Shields G (2022) Cite them right. Bloomsbury Publishing

Harvard system (1999) Bournemouth University. http://ibse.hk/Harvard_System.pdf . Accessed 28 Dec 2022

Gitanjali B (2004) Reference styles and common problems with referencing: Medknow. https://www.jpgmonline.com/documents/author/24/11_Gitanjali_3.pdf . Accessed 28 Dec 2022

Williams K, Spiro J, Swarbrick N (2008) How to reference Harvard referencing for Westminster Institute students. Westminster Institute of Education Oxford Brookes University

Harvard: reference list and bibliography: University of Birmingham. 2022. https://intranet.birmingham.ac.uk/as/libraryservices/library/referencing/icite/harvard/referencelist.aspx . Accessed 28 Dec 2022

Limited SN (2017) Responsible referencing. Nat Methods 14(3):209

Article Google Scholar

Hensley MK (2011) Citation management software: features and futures. Ref User Serv Q 50(3):204–208

Ramesh A, Rajasekaran MR (2014) Zotero: open-source bibliography management software. RGUHS J Pharm Sci 4:3–6

Shapland M (2000) Evaluation of reference management software on NT (comparing Papyrus with Procite, Reference Manager, Endnote, Citation, GetARef, Biblioscape, Library Master, Bibliographica, Scribe, Refs). University of Bristol

EndNote 20. Clarivate. 2022. https://endnote.com/product-details . Accessed 28 Dec 2022

Angélil-Carter S (2014) Stolen language? Plagiarism in writing. Routledge

Book Google Scholar

Howard RM (1995) Plagiarisms, authorships, and the academic death penalty. Coll Engl 57(7):788–806

Barrett R, Malcolm J (2006) Embedding plagiarism education in the assessment process. Int J Educ Integr 2(1):38–45

Introna L, Hayes N, Blair L, Wood E (2003) Cultural attitudes towards plagiarism. University of Lancaster, Lancaster, pp 1–57

Neville C (2016) The complete guide to referencing and avoiding plagiarism. McGraw-Hill Education (UK), London, p 43

Campion EW, Anderson KR, Drazen JM (2001) Internet-only publication. N Engl J Med 345(5):365

Li X, Crane N (1996) Electronic styles: a handbook for citing electronic information. Information Today, Inc.

APA (2005) Concise rules of APA style. APA, Washington, DC

Snyder PJ, Peterson A (2002) The referencing of internet web sites in medical and scientific publications. Brain Cogn 50(2):335–337

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Barroga EF (2014) Reference accuracy: authors’, reviewers’, editors’, and publishers’ contributions. J Korean Med Sci 29(12):1587–1589

Standardization IOf (1997) Information and documentation—bibliographic references—part 2: electronic documents or parts thereof, ISO 690-2: 1997. ISO

Download references

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Urology, University of California at San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA

Rohan Reddy, Samuel Sorkhi & Saager Chawla

Department of Urology, University of California and VA San Diego Healthcare System, San Diego, CA, USA

Mahadevan Raj Rajasekaran

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mahadevan Raj Rajasekaran .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Retired Senior Expert Pharmacologist at the Office of Cardiology, Hematology, Endocrinology, and Nephrology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA

Gowraganahalli Jagadeesh

Professor & Director, Research Training and Publications, The Office of Research and Development, Periyar Maniammai Institute of Science & Technology (Deemed to be University), Vallam, Tamil Nadu, India

Pitchai Balakumar

Division Cardiology & Nephrology, Office of Cardiology, Hematology, Endocrinology and Nephrology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA

Fortunato Senatore

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Reddy, R., Sorkhi, S., Chawla, S., Rajasekaran, M.R. (2023). How to Create a Bibliography. In: Jagadeesh, G., Balakumar, P., Senatore, F. (eds) The Quintessence of Basic and Clinical Research and Scientific Publishing. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1284-1_39

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1284-1_39

Published : 01 October 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-99-1283-4

Online ISBN : 978-981-99-1284-1

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Biomedical and Life Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Utility Menu

fa3d988da6f218669ec27d6b6019a0cd

A publication of the harvard college writing program.

Harvard Guide to Using Sources

- The Honor Code

- Sample Bibliography

Below you’ll find a Bibliography adapted from a research paper written by Aishani Aatresh for her Technology, Environment, and Society course.

- Citation Management Tools

- In-Text Citations

- Bibliography

- Examples of Commonly Cited Sources

- Frequently Asked Questions about Citing Sources in Chicago Format

PDFs for This Section

- Citing Sources

- Online Library and Citation Tools

APA Citation Style

Citation examples.

- Paper Format

- Style and Grammar Guidelines

- Citation Management Tools

- What's New in the 7th Edition?

- APA Style References Guidelines from the American Psychological Association

- APA Style (OWL - Online Writing Lab, Purdue University)

- Common Reference Examples Handout

- Journal Article

- Magazine Article

- Newspaper Article

- Edited Book Chapter

- Dictionary Entry

- Government Report

- YouTube Video

- Facebook Post

- Webpage on a Website

- Supplemental Reference Examples

- Archival Documents and Collections

Parenthetical citations: (Grady et al., 2019; Jerrentrup et al., 2018)

Narrative citations: Grady et al. (2019) and Jerrentrup et al. (2018)

- If a journal article has a DOI, include the DOI in the reference.

- If the journal article does not have a DOI and is from an academic research database, end the reference after the page range (for an explanation of why, see the database information page). The reference in this case is the same as for a print journal article.

- Do not include database information in the reference unless the journal article comes from a database that publishes original, proprietary content, such as UpToDate (see an example on the database information page).

- If the journal article does not have a DOI but does have a URL that will resolve for readers (e.g., it is from an online journal that is not part of a database), include the URL of the article at the end of the reference.

- If the journal article has an article number instead of a page range, include the article number instead of the page range (as shown in the Jerrentrup et al. example).

Parenthetical citations: (Rabinowitz, 2019; Sapolsky, 2017)

Narrative citations: Rabinowitz (2019) and Sapolsky (2017)

- If the book includes a DOI, include the DOI in the reference after the publisher name.

- Do not include the publisher location.

- If the book does not have a DOI and comes from an academic research database, end the book reference after the publisher name. Do not include database information in the reference. The reference in this case is the same as for a print book.

Parenthetical citations: (Schaefer & Shapiro, 2019; Schulman, 2019)

Narrative citations: Schaefer and Shapiro (2019) and Schulman (2019)

- If a magazine article has a DOI, include the DOI in the reference.

- If the magazine article does not have a DOI and is from an academic research database, end the reference after the page range. Do not include database information in the reference. The reference in this case is the same as for a print magazine article.

- If the magazine article does not have a DOI but does have a URL that will resolve for readers (e.g., it is from an online magazine that is not part of a database), include the URL of the article at the end of the reference.

- If the magazine article does not have volume, issue, and/or page numbers (e.g., because it is from an online magazine), omit the missing elements from the reference (as in the Schulman example).

Parenthetical citation: (Carey, 2019)

Narrative citation: Carey (2019)

- If the newspaper article is from an academic research database, end the reference after the page range. Do not include database information in the reference. The reference in this case is the same as for a print newspaper article.

- If the newspaper article has a URL that will resolve for readers (e.g., it is from an online newspaper), include the URL of the article at the end of the reference.

- If the newspaper article does not have volume, issue, and/or page numbers (e.g., because it is from an online newspaper), omit the missing elements from the reference, as shown in the example.

- If the article is from a news website (e.g., CNN, HuffPost)—one that does not have an associated daily or weekly newspaper—use the format for a webpage on a website instead.

Parenthetical citation: (Aron et al., 2019)

Narrative citation: Aron et al. (2019)

- If the edited book chapter includes a DOI, include the chapter DOI in the reference after the publisher name.

- If the edited book chapter does not have a DOI and comes from an academic research database, end the edited book chapter reference after the publisher name. Do not include database information in the reference. The reference in this case is the same as for a print edited book chapter.

- Do not create references for chapters of authored books. Instead, write a reference for the whole book and cite the chapter in the text if desired (e.g., Kumar, 2017, Chapter 2).

Parenthetical citation: (Merriam-Webster, n.d.)

Narrative citation: Merriam-Webster (n.d.)

- Because entries in Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary are updated over time and are not archived, include a retrieval date in the reference.

- Merriam-Webster is both the author and the publisher, so the name appears in the author element only to avoid repetition.

- To quote a dictionary definition, view the pages on quotations and how to quote works without page numbers for guidance. Additionally, here is an example: Culture refers to the “customary beliefs, social forms, and material traits of a racial, religious, or social group” (Merriam-Webster, n.d., Definition 1a).

Parenthetical citation: (National Cancer Institute, 2019)

Narrative citation: National Cancer Institute (2019)

The specific agency responsible for the report appears as the author. The names of parent agencies not present in the group author name appear in the source element as the publisher. This creates concise in-text citations and complete reference list entries.

Parenthetical citation: (Harvard University, 2019)

Narrative citation: Harvard University (2019)

- Use the name of the account that uploaded the video as the author.

- If the account did not actually create the work, explain this in the text if it is important for readers to know. However, if that would mean citing a source that appears unauthoritative, you might also look for the author’s YouTube channel, official website, or other social media to see whether the same video is available elsewhere.

Parenthetical citations: (APA Databases, 2019; Gates, 2019)

Narrative citations: APA Databases (2019) and Gates (2019)

- Present the name of the individual or group author the same as you would for any other reference. Then provide the Twitter handle (beginning with the @ sign) in square brackets, followed by a period.

- Provide the first 20 words of the tweet as the title. Count a URL, a hashtag, or an emoji as one word each, and include them in the reference if they fall within the first 20 words.

- If the tweet includes an image, a video, a poll, or a thumbnail image with a link, indicate that in brackets after the title: [Image attached], [Video attached], [Thumbnail with link attached].

- The same format used for Twitter is also used for Instagram.

Parenthetical citation: (News From Science, 2019)

Narrative citation: News From Science (2019)

- Provide the first 20 words of the Facebook post as the title. Count a URL or other link, a hashtag, or an emoji as one word each, and include them in the reference if they fall within the first 20 words.

- If a status update includes images, videos, thumbnail links to outside sources, or content from another Facebook post (such as when sharing a link), indicate that in square brackets.

Parenthetical citations: (Fagan, 2019; National Institute of Mental Health, 2018; Woodyatt, 2019; World Health Organization, 2018)

Narrative citations: Fagan (2019), National Institute of Mental Health (2018), Woodyatt (2019), and World Health Organization (2018)

- Provide as specific a date as is available on the webpage. This might be a year only; a year and month; or a year, month, and day.

- Italicize the title of a webpage.

- When the author of the webpage and the publisher of the website are the same, omit the publisher name to avoid repetition (as in the World Health Organization example).

- When contents of a page are meant to be updated over time but are not archived, include a retrieval date in the reference (as in the Fagan example).

- Use the webpage on a website format for articles from news websites such as CNN and HuffPost (these sites do not have associated daily or weekly newspapers). Use the newspaper article category for articles from newspaper websites such as The New York Times or The Washington Post .

- Create a reference to an open educational resources (OER) page only when the materials are available for download directly (i.e., the materials are on the page and/or can be downloaded as PDFs or other files). If you are directed to another website, create a reference to the specific webpage on that website where the materials can be retrieved. Use this format for material in any OER repository, such as OER Commons, OASIS, or MERLOT.

- Do not create a reference or in-text citation for a whole website. To mention a website in general, and not any particular information on that site, provide the name of the website in the text and include the URL in parentheses. For example, you might mention that you used a website to create a survey.

The following supplemental example references are mention in the Publication Manual:

- retracted journal or magazine article

- edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)

- edition of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD)

- religious work

- annotated religious work

Archival document and collections are not presented in the APA Publication Manual, Seventh Edition . This content is available only on the APA Style website . This guidance has been expanded from the 6th edition.

Archival sources include letters, unpublished manuscripts, limited-circulation brochures and pamphlets, in-house institutional and corporate documents, clippings, and other documents, as well as such nontextual materials as photographs and apparatus, that are in the personal possession of an author, form part of an institutional collection, or are stored in an archive such as the Archives of the History of American Psychology at the University of Akron or the APA Archives. For any documents like these that are available on the open web or via a database (subscription or nonsubscription), follow the reference templates shown in Chapter 10 of the Publication Manual.

The general format for the reference for an archival work includes the author, date, title, and source. The reference examples shown on this page may be modified for collections requiring more or less specific information to locate materials, for different types of collections, or for additional descriptive information (e.g., a translation of a letter). Authors may choose to list correspondence from their own personal collections, but correspondence from other private collections should be listed only with the permission of the collector.

Keep in mind the following principles when creating references to archival documents and collections:

- As with any reference, the purpose is to direct readers to the source, despite the fact that only a single copy of the document may be available and readers may have some difficulty actually seeing a copy.

- Include as much information as is needed to help locate the item with reasonable ease within the repository. For items from collections with detailed finding aids, the name of the collection may be sufficient; for items from collections without finding aids, more information (e.g., call number, box number, file name or number) may be necessary to help locate the item.

- If several letters are cited from the same collection, list the collection as a reference and provide specific identifying information (author, recipient, and date) for each letter in the in-text citations (see Example 3).

- Use square brackets to indicate information that does not appear on the document.

- Use “ca.” (circa) to indicate an estimated date (see Example 5).

- Use italics for titles of archival documents and collections; if the work does not have a title, provide a description in square brackets without italics.

- Separate elements of the source (e.g., the name of a repository, library, university or archive, and the location of the university or archive) with commas. End the source with a period.

- If a publication of limited circulation is available in libraries, the reference may be formatted as usual for published material, without the archival source.

- Note that private letters (vs. those in an archive or repository) are considered personal communications and cited in the text only.

1. Letter from a repository

Frank, L. K. (1935, February 4). [Letter to Robert M. Ogden]. Rockefeller Archive Center (GEB Series 1.3, Box 371, Folder 3877), Tarrytown, NY, United States.

- Parenthetical citation: (Frank, 1935)

- Narrative citation: Frank (1935)

- Because the letter does not have a title, provide a description in square brackets.

2. Letter from a private collection

Zacharius, G. P. (1953, August 15). [Letter to William Rickel (W. Rickel, Trans.)]. Copy in possession of Hendrika Vande Kemp.

- Parenthetical citation: (Zacharius, 1953)

- Narrative citation: Zacharius (1953)

- In this example, Hendrika Vande Kemp is either the author of the paper or the author of the paper has received permission from Hendrika Vande Kemp to cite a letter in Vande Kemp’s private collection in this way. Otherwise, cite a private letter as a personal communication .

3. Collection of letters from an archive

Allport, G. W. (1930–1967). Correspondence. Gordon W. Allport Papers (HUG 4118.10), Harvard University Archives, Cambridge, MA, United States.

- Parenthetical citation: (Allport, 1930–1967)

- Narrative citation: Allport (1930–1967)

To cite specific letters in the text, provide the author and range of years as shown in the reference list entry, plus details about who wrote the specific letter to whom and when the specific letter was written.

- Parenthetical citation: (Allport, 1930–1967, G. Boring to Allport, December 26, 1937)

- Narrative citation: Allport (1930–1967, Allport to G. Boring, March 1, 1939)

- Use the parenthetical citation format to cite a letter that E. G. Boring wrote to Allport because Allport is the author in the reference. Use either the parenthetical or narrative citation format to cite letters that Allport wrote.

4. Unpublished papers, lectures from an archive or personal collection

Berliner, A. (1959). Notes for a lecture on reminiscences of Wundt and Leipzig. Anna Berliner Memoirs (Box M50), Archives of the History of American Psychology, University of Akron, Akron, OH, United States.

- Parenthetical citation: (Berliner, 1959)

- Narrative citation: Berliner (1959)

5. Archival/historical source for which the author and/or date is known or is reasonably certain but not stated on the document

Allport, A. (presumed). (ca. 1937). Marion Taylor today—by the biographer [Unpublished manuscript]. Marion Taylor Papers, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe College, Cambridge, MA, United States.

- Parenthetical citation: (Allport, ca. 1937)

- Narrative citation: Allport (ca. 1937)

- Because the author is reasonably certain but not stated on the document, place the word “presumed” in parentheses after the name, followed by a period.

- Because the date is reasonably certain but not stated on the document, the abbreviation “ca.” (which stands for “circa”) appears before the year in parentheses.

6. Archival source with group author

Subcommittee on Mental Hygiene Personnel in School Programs. (1949, November 5–6). Meeting of Subcommittee on Mental Hygiene Personnel in School Programs. David Shakow Papers (M1360), Archives of the History of American Psychology, University of Akron, Akron, OH, United States.

- Parenthetical citation: (Subcommittee on Mental Hygiene Personnel in School Programs, 1949)

- Narrative citation: Subcommittee on Mental Hygiene Personnel in School Programs (1949)

7. Interview recorded and available in an archive

Smith, M. B. (1989, August 12). Interview by C. A. Kiesler [Tape recording]. President’s Oral History Project, American Psychological Association, APA Archives, Washington, DC, United States.

- Parenthetical citation: (Smith, 1989)

- Narrative citation: Smith (1989)

- For interviews and oral histories recorded in an archive, list the interviewee as the author. Include the interviewer’s name in the description.

8. Transcription of a recorded interview, no recording available

Sparkman, C. F. (1973). An oral history with Dr. Colley F. Sparkman/Interviewer: Orley B. Caudill. Mississippi Oral History Program (Vol. 289), University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, MS, United States.

- Parenthetical citation: (Sparkman, 1973)

- Narrative citation: Sparkman (1973)

9. Newspaper article clipping, historical, in personal collection

Psychoanalysis institute to open. (1948, September 18). [Clipping from an unidentified Dayton, OH, United States, newspaper]. Copy in possession of author.

- Parenthetical citation: (“Psychoanalysis Institute to Open,” 1948)

- Narrative citation: “Psychoanalysis Institute to Open” (1948)

- Use this format only if you are the person who is in possession of the newspaper clipping.

10. Historical publication of limited circulation

Sci-Art Publishers. (1935). Sci-Art publications [Brochure]. Roback Papers (HUGFP 104.50, Box 2, Folder “Miscellaneous Psychological Materials”), Harvard University Archives, Cambridge, MA, United States.

- Parenthetical citation: (Sci-Art Publishers, 1935)

- Narrative citation: Sci-Art Publishers (1935)

11. Archived photographs, no author and no title

[Photographs of Robert M. Yerkes]. (ca. 1917–1954). Robert Mearns Yerkes Papers (Box 137, Folder 2292), Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library, New Haven, CT, United States.

- Parenthetical citation: ([Photographs of Robert M. Yerkes], ca. 1917–1954)

- Narrative citation: [Photographs of Robert M. Yerkes] (ca. 1917–1954)

- Because the archived photographs do not have a title, provide a bracketed description instead.

- Because the archived photographs do not have an author, move the bracketed description to the author position of the reference.

12. Microfilm

U.S. Census Bureau. (1880). 1880 U.S. census: Defective, dependent, and delinquent classes schedule: Virginia [Microfilm]. NARA Microfilm Publication T1132 (Rolls 33–34), National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, United States.

- Parenthetical citation: (U.S. Census Bureau, 1880)

- Narrative citation: U.S. Census Bureau (1880)

Read the full APA guidelines on citing ChatGPT

OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT (Mar 14 version) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat

- Parenthetical citation: (OpenAI, 2023)

- Narrative citation: OpenAI (2023)

Author: The author of the model is OpenAI.

Date: The date is the year of the version you used. Following the template in Section 10.10, you need to include only the year, not the exact date. The version number provides the specific date information a reader might need.

Title: The name of the model is “ChatGPT,” so that serves as the title and is italicized in your reference, as shown in the template. Although OpenAI labels unique iterations (i.e., ChatGPT-3, ChatGPT-4), they are using “ChatGPT” as the general name of the model, with updates identified with version numbers.

The version number is included after the title in parentheses. The format for the version number in ChatGPT references includes the date because that is how OpenAI is labeling the versions. Different large language models or software might use different version numbering; use the version number in the format the author or publisher provides, which may be a numbering system (e.g., Version 2.0) or other methods.

Bracketed text is used in references for additional descriptions when they are needed to help a reader understand what’s being cited. References for a number of common sources, such as journal articles and books, do not include bracketed descriptions, but things outside of the typical peer-reviewed system often do. In the case of a reference for ChatGPT, provide the descriptor “Large language model” in square brackets. OpenAI describes ChatGPT-4 as a “large multimodal model,” so that description may be provided instead if you are using ChatGPT-4. Later versions and software or models from other companies may need different descriptions, based on how the publishers describe the model. The goal of the bracketed text is to briefly describe the kind of model to your reader.

Source: When the publisher name and the author name are the same, do not repeat the publisher name in the source element of the reference, and move directly to the URL. This is the case for ChatGPT. The URL for ChatGPT is https://chat.openai.com/chat . For other models or products for which you may create a reference, use the URL that links as directly as possible to the source (i.e., the page where you can access the model, not the publisher’s homepage).

What to include and what to exclude

Works included in a reference list.

The reference list provides a reliable way for readers to identify and locate the works cited in a paper. APA Style papers generally include reference lists, not bibliographies.

In general, each work cited in the text must appear in the reference list, and each work in the reference list must be cited in the text. Check your work carefully before submitting your manuscript or course assignment to ensure no works cited in the text are missing from the reference list and vice versa, with only the following exceptions.

Works Excluded From a Reference List

There are a few kinds of works that are not included in a reference list. Usually a work is not included because readers cannot recover it or because the mention is so broad that readers do not need a reference list entry to understand the use.

Information on works included in a reference list is covered in Sections 2.12 and 8.4 of the APA Publication Manual, Seventh Edition

*This guidance has been expanded from the 6th edition.*

- Personal communications such as emails, phone calls, or text messages are cited in the text only, not in the reference list, because readers cannot retrieve personal communications.

- General mentions of whole websites, whole periodicals, and common software and apps in the text do not require in-text citations or reference list entries because the use is broad and the source is familiar.

- The source of an epigraph does not usually appear in the reference list unless the work is a scholarly book or journal. For example, if you open the paper with an inspirational quotation by a famous person, the source of the quotation does not appear in the reference list because the quotation is meant to set the stage for the work, not substantiate a key point.

- Quotations from research participants in a study you conducted can be presented and discussed in the text but do not need citations or reference list entries. Citations and reference list entries are not necessary because the quotations are part of your original research. They could also compromise participants’ confidentiality, which is an ethical violation.

- References included in a meta-analysis, which are marked with an asterisk in the reference list, may be cited in the text (or not) at the author’s discretion. This exception is relevant only to authors who are conducting a meta-analysis.

DOIs and URLs

The DOI or URL is the final component of a reference list entry. Because so much scholarship is available and/or retrieved online, most reference list entries end with either a DOI or a URL.

- A DOI is a unique alphanumeric string that identifies content and provides a persistent link to its location on the internet. DOIs can be found in database records and the reference lists of published works.

- A URL specifies the location of digital information on the internet and can be found in the address bar of your internet browser. URLs in references should link directly to the cited work when possible.

Follow these guidelines for including DOIs and URLs in references:

- Include a DOI for all works that have a DOI, regardless of whether you used the online version or the print version.

- If a print work does not have a DOI, do not include any DOI or URL in the reference.

- If an online work has both a DOI and a URL, include only the DOI.

- For works without DOIs from websites (not including academic research databases), provide a URL in the reference (as long as the URL will work for readers).

- For works without DOIs from most academic research databases , do not include a URL or database information in the reference because these works are widely available. The reference should be the same as the reference for a print version of the work.

- For works from databases that publish original, proprietary material available only in that database (such as the UpToDate database) or for works of limited circulation in databases (such as monographs in the ERIC database), include the name of the database or archive and the URL of the work. If the URL requires a login or is session-specific (meaning it will not resolve for readers), provide the URL of the database or archive home page or login page instead of the URL for the work. See the page on including database information in references for more information.

- If the URL is no longer working or no longer provides readers access to the content you intend to cite, follow the guidance for works with no source .

- Other alphanumeric identifiers such as the International Standard Book Number (ISBN) and the International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) are not included in APA Style references.

Follow these guidelines to format DOIs and URLs: