256 Research Topics on Criminal Justice & Criminology

Are you a law school student studying criminal behavior or forensic science? Or maybe just looking for good criminal justice topics, questions, and hypotheses? Look no further! Custom-writing.org experts offer a load of criminology research topics and titles for every occasion. Criminological theories, types of crime, the role of media in criminology, and more. Our topics will help you prepare for a college-level assignment, debate, or essay writing.

Our specialists will write a custom essay specially for you!

- ⚖️ Criminology vs. Criminal Justice

- 🔬 120 Criminology Research Topics

- 💂 116 Criminal Justice Research Topics

🔥 Hot Criminology Research Topics

- The role of media in criminology.

- Cultural explanation of crime.

- Benefits of convict criminology.

- Main issues of postmodern criminology.

- Is criminal behavior affected by the politics?

- How does DAWN collect data?

- The limitations of crime mapping.

- Personality traits that trigger criminal behavior.

- Community deterioration and crime rates.

- Does experimental criminology affect social policy?

🔬 120 Criminology Research Topics & Ideas

Here are 100 criminology research topics ideas organized by themes.

Just in 1 hour! We will write you a plagiarism-free paper in hardly more than 1 hour

General Criminology Research Paper Topics

- Criminology as a social science.

- Criminology and its public policies.

- History of criminology.

- Crime commission: legal and social perspectives .

Criminal Psychology Research Topics

- What is the nature of criminal behavior ?

- How does the lack of education affect the incarceration rates?

- Childhood aggression and the impact of divorce

- The effect of the upbringing on antisocial adult behavior

- How do gender and cultural background affect one’s attitude towards drug abuse ?

- Forensic psychology and its impact on the legal system

- What is the role of criminal psychologists?

- Different types of forensic psychological evaluations

- What’s the difference between therapeutic and forensic evaluation?

- Does socioeconomic status impact one’s criminal behavior ?

Criminology Research Topics: Theories

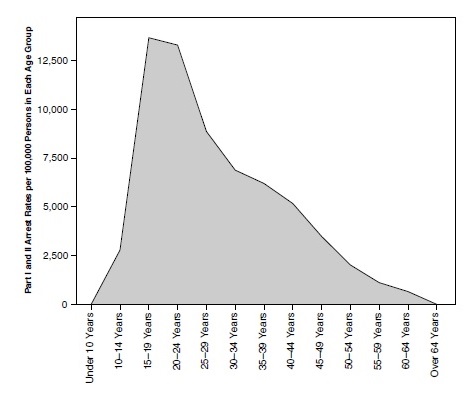

- What crimes are typical for what ages?

- How does the type of crime correspond with the level of exerted aggression ?

- What is the connection between citizenship (or lack thereof) and law violation?

- How does education (or lack thereof) correspond with crime level?

- Does employment (or lack thereof) correspond with law violation?

- What is the connection between family status and law violation?

- Does gender affect on the type of law violation?

- How does ownership of firearms correspond with law violation?

- Does immigrant status correlate with law violation?

- Is there a connection between mental health and law violation?

- What are the causes of violence in the society?

- Does the crime rate depend on the neighborhood ?

- How does race correspond with the type of crime?

- Do religious beliefs correspond with law violation?

- How does social class correlate with crime rate?

- What are the reasons for the homeless’ improsonment?

- How does weather correspond with law violation?

Criminology Topics on Victimization

- Biological theories of crime: how do biological factors correspond with law violation?

- Classical criminology: the contemporary take on crime, economics, deterrence, and the rational choice perspective.

- Convict criminology: what do ex-convicts have to say on the subject?

- Criminal justice theories: punishment as a deterrent to crime.

- Critical criminology : debunking false ideas about crime and criminal justice.

- Cultural criminology: criminality as the product of culture.

- Cultural transmission theory: how criminal norms are transmitted in social interaction.

- Deterrence theory: how people don’t commit crimes out of fear of punishment.

- Rational choice theory : how crime doing is aligned with personal objectives of the perpetrator.

- Feminist Criminology: how the dominant crime theories exclude women.

- Labeling and symbolic interaction theories: how minorities and those deviating from social norms tend to be negatively labeled.

- Life course criminology : how life events affect the actions that humans perform.

- Psychological theories of crime: criminal behavior through the lense of an individual’s personality.

- Routine activities theory : how normal everyday activities affect the tendency to commit a crime.

- The concept of natural legal crime.

- Self-control theory : how the lack of individual self-control results in criminal behavior.

- Social construction of crime: crime doing as social response.

- Social control theory : how positive socialization corresponds with reduction of criminal violation.

- Social disorganization theory : how neighborhood ecological characteristics correspond with crime rates.

- Social learning theory : how (non)criminal behavior can be acquired by observing and imitating others.

- Strain theories : how social structures within society pressure citizens to commit crime.

- Theoretical integration: how two theories are better than one.

Criminology Research and Measurement Topics

- Citation content analysis (CCA): a framework for gaining knowledge from a variety of media.

- Crime classification systems: classification of crime according to the severity of punishment.

- Crime mapping as a way to map, visualize, and analyze crime incident patterns.

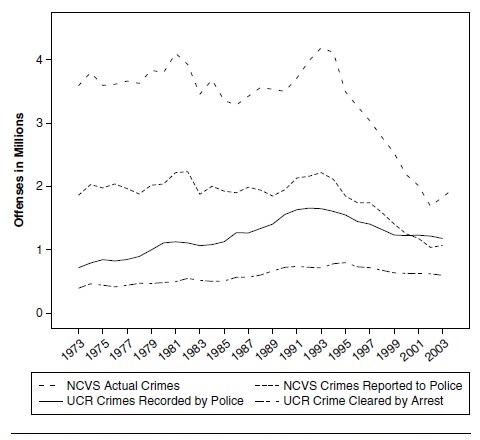

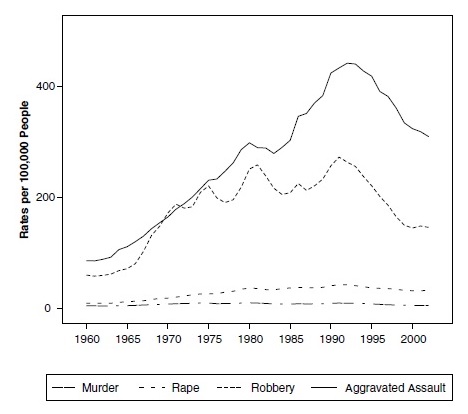

- Reports and statistics of crime: the estimated rate of crime over time. Public surveys.

- Drug abuse warning network (DAWN): predicting trends in drug misuse.

- Arrestee drug abuse monitoring (ADAM): drug use among arrestees.

- Edge ethnography: collecting data undercover in typically closed research settings and groups through rapport development or covert undercover strategy.

- Experimental criminology: experimental and quasi-experimental research in the advancement of criminological theory.

- Fieldwork in criminology: street ethnographers and their dilemmas in the field concerning process and outcomes.

- Program evaluation: collecting and analyzing information to assess the efficiency of projects, policies and programs.

- Quantitative criminology: how exploratory research questions, inductive reasoning , and an orientation to social context help recognize human subjectivity.

Criminology Topics on Types of Crime

- Campus crime: the most common crimes on college campuses and ways of preventing them.

- Child abuse : types, prevalence, risk groups, ways of detection and prevention.

- Cybercrime : cyber fraud, defamation, hacking, bullying, phishing.

- Domestic violence : gender, ways of detection and prevention, activism.

- Domestic violence with disabilities .

- Elder abuse : types, prevalence, risk groups, ways of detection and prevention.

- Environmental crime. Natural resource theft: illegal trade in wildlife and timber, poaching, illegal fishing.

- Environmental crime. Illegal trade in ozone-depleting substances, hazardous waste; pollution of air, water, and soil.

- Environmental crime: local, regional, national, and transnational level.

- Environmental crime: climate change crime and corruption.

- Environmental crime: wildlife harming and exploitation.

- Hate crime : how prejudice motivates violence.

- Homicide : what motivates one person to kill another.

- Human trafficking : methods of deception, risk groups, ways of detection and prevention.

- Identity theft : methods, risk groups, ways of detection and prevention.

- Gambling in America .

- Juvenile delinquency : risk groups, prevention policies, prosecution and punishment.

- Juvenile Delinquency: Causes and Effects

- Organizational crime: transnational, national, and local levels. Ways of disrupting the activity of a group.

- Prostitution : risk groups, different takes on prevention policies, activism.

- Robbery : risk groups, ways of prevention, prosecution and punishment.

- Sex offenses: risk groups, types, prevalence, ways of detection and prevention.

- Terrorism: definition, history, countermeasures .

- Terrorism : individual and group activity, ways of detection and prevention.

- Theft and shoplifting : risk groups, ways of detection, prevention policies, prosecution and punishment.

- Counter-terrorism: constitutional and legislative issues .

- White-collar crime : types, ways of detection, prevention policies, prosecution and punishment.

Criminology Topics on Racism and Discrimination

- How systemic bias affects criminal justice?

- How discriminatory portrayal of minority groups in the media affects criminal justice?

- Racial profiling : targeting minority groups on the basis of race and ethnicity.

- Racism and discrimination towards African-Americans .

- Racial profiling : what are the cons? Are there any pros?

- How discriminatory is the UK Court System?

- How discriminatory is the US Court System?

Other Criminology Research Topics

- Corporate crime : the ruling class criminals.

- Genetics: illegal research and its dangers.

- Hate crime : the implications in criminal justice.

- Serial killers : risk groups, ways of detection and prevention.

- Serial killers: portrayal in media.

- Organized crime : how does it affect criminal justice?

- Crime prevention programs.

- Street lighting: does it reduce crime?

- Terrorism prevention technology.

- Identity theft : risk groups, ways of deception, prevention policies.

- Due process model: procedural and substantive aspects.

- Crime control in criminal justice administration.

- Types of drugs: how do they affect the users?

- Smart handheld devices: their function for security personnel.

- Social media : its impact on crime rate.

- Public health: how does criminal justice affect it?

- Psychometric examinations: what is their role in criminal justice?

- National defense in the US.

- National defense in the UK.

- Sexual harassment : the role of activism, ways of responding, prevention and prosecution.

- Substance abuse : military.

- Criminology and criminal justice jobs: a full list.

🌶️ Hot Criminal Justice Topics

- The history of modern police.

- Different types of prison systems.

- Is situational crime prevention effective?

- How to prevent wrongful convictions.

- Challenges faced by crime victims.

- The advantages of community corrections.

- How do ethics influence criminal justice?

- Disadvantages of felony disenfranchisement.

- Does correctional system in the USA really work?

- Possible problems of prisoner reentry process.

💂 116 Criminal Justice Research Topics & Questions

Here are some of the most typical and interesting criminal justice issues to dazzle your professor.

- Prison system : the main problems and the hidden pitfalls.

- The question of gender: why are there more men who receive capital punishment than women?

- Kidnapping and ransom: common features, motifs, behavior patterns.

- Crime prevention : key principles.

- Firing a gun: what helps professionals understand whether it was deliberate or happened by accident?

- Cybercrime : the legal perspective.

- Internet vigilantism: revenge leaks.

- Hate crime on the Internet: revenge leaks, trolling, defamation.

- Crime and justice in mass media .

- Parental abduction laws.

- Sex offender registry: pros and cons.

- The deterrence theory and the theory of rational choice : are they relevant in the modern world?

- Sexual assault in schools and workplaces.

- Jury selection: how is it performed?

- Experimental criminology: the latest innovations.

- Wildlife crime: areas of prevalence, ways of prevention.

- Felony disenfranchisement laws: when do they apply?

- The relation between organized crime and corruption .

- Victim services: what help can a victim of a crime get?

- Prison rape and violence: the psychological aspect, ways of prevention.

- Juvenile recidivism : what are the risk groups?

- Forensic science : role and functions in modern criminal justice.

- Shoplifting: how to prevent theft?

- Witness Protection Program: who is eligible and how to protect them.

- Date rape : what are the ways for the victims to seek legal assistance?

- Substance abuse and crime: correlation or causation?

- Identity theft: dangers and consequences in the modern world.

- Online predators: what laws can be introduced to protect kids? Real-life examples.

- Civil and criminal cases: how to differentiate?

- Domestic abuse victims: what laws protect them?

- Elder abuse : what can be done to prevent it?

- The strain theory : the unachievable American dream.

- Concepts of law enforcement: pursuing criminal justice .

- Ethics and criminal justice: the unethical sides of law enforcement.

- The top problems to be solved by law enforcement today.

- Information sharing technology: how has it helped in the fight against terrorism ?

- Terrorism in perspective: characteristics, causes, control .

- Serial killers : types.

- Drug use and youth arrests.

- Aggressive behavior : how does it correlate with criminal tendencies?

- Community corrections : are they effective?

- Sentencing: how does it take place?

- Punishment types and the established terms.

- Unwarranted arrest: when is it acceptable?

- Human trafficking in the modern world.

- Human trafficking: current state and counteracts .

- The role of technology in modern forensics .

- Similarities and differences between homicide , murder, and manslaughter.

- Types of offenders: classification.

- Effects of gun control measures in the United States .

- The role of crime mapping in modern criminal justice.

- Male crimes vs female crimes: are they different?

- Prisons : the problems of bad living conditions.

- Victimization : causes and ways of prevention.

- Victimology and traditional justice system alternatives .

- Rape victims: what are their rights?

- Problem-solving courts: what underlying problems do they address?

- Mandatory sentencing and the three-strike rule.

- Have “three-strikes” laws been effective and should they be continued?

- Criminal courts : what can be learned from their history?

- Hate crimes : what motivates people to commit them?

- Youth gangs: what is their danger?

- Fieldwork: how is it done in criminology?

- Distributive justice : its place in criminal justice.

- Capital punishment : what can be learned from history?

- Humanities and justice in Britain during 18th century .

- Abolition of capital punishment .

- Criminals and prisoners’ rights .

- Crime prevention programs and criminal rehabilitation .

- Campus crime: what laws and precautions are there against it?

- Criminal trial process: how does it go?

- Crimes committed on a religious basis: how are they punished?

- The code of ethics in the Texas department of criminal justice .

- Comparison between Florida and Maryland’s legislative frameworks .

- Fraud in the scientific field: how can copyright protect the discoveries of researchers?

- Prosecution laws: how are they applied in practice?

- The classification of crime systems.

- Cyberbullying and cyberstalking: what can parents do to protect their children?

- Forgery cases in educational institutions, offices, and governmental organizations.

- Drug courts : how do they work?

Controversial Topics in Criminal Justice

Want your work to be unconventional? Consider choosing one of the controversial topics. You will need to present a number of opposite points of view. Of course, it’s acceptable to choose and promote an opinion that you think stands the best. Just make sure to provide a thorough analysis of all of the viewpoints.

You can also stay impartial and let the reader make up their own mind on the subject. If you decide to support one of the viewpoints, your decision should be objective. Back it up with plenty of evidence, too. Here are some examples of controversial topics that you can explore.

- Reform vs. punishment: which one offers more benefits?

- Restorative justice model : is it the best criminal justice tool?

- The war on drugs : does it really solve the drug problem?

- Criminal insanity: is it a reason enough for exemption from liability?

- Juvenile justice system : should it be eliminated?

- Drug testing on the school ground.

- Police brutality in the United States .

- How to better gun control ?

- Why Gun Control Laws Should be Scrapped .

- Pornography: is it a type of sexual violence?

- Whether death penalty can be applied fairly?

- Jack the Ripper: who was he?

- The modern justice system: is it racist?

- A false accusation: how can one protect themselves from it?

- Concealed weapons: what are the criminal codes of various states?

- Race and crime: is there a correlation?

- Registering sex offenders: should this information be in public records?

- Juvenile delinquency and bad parenting: is there a relation?

- Assessing juveniles for psychopathy or conduct disorder .

- Should all new employees be checked for a criminal background ?

- Are delinquency cases higher among immigrant children?

- Restrictive housing: can it help decongest prisons?

- Homegrown crimes: is there an effective program against them?

- Prostitution: the controversy around legalization .

- Eyewitness testimony : is it really helpful in an investigation?

- Youthful offenders in boot camps: is this strategy effective?

- Predictive policing : is it effective?

- Selective incapacitation: is it an effective policy for reducing crime?

- Social class and crime: is there a relation?

- Death penalty: is it effective in crime deterrence?

- Extradition law: is it fair?

- Devious interrogations: is deceit acceptable during investigations?

- Supermax prisons: are they effective or just cruel?

- Zero tolerance: is it the best policy for crime reduction?

- Marijuana decriminalization: pros and cons.

- Marijuana legalization in the US .

Now that you have looked through the full list of topics, choose wisely. Remember that sometimes it’s best to avoid sensitive topics. Other times, a clever choice of a topic will win you extra points. It doesn’t depend on just the tastes of your professor, of course. You should also take into account how much relevant information there is on the subject. Anyway, the choice of the topic of your research is up to you. Try to find the latest materials and conduct an in-depth analysis of them. Don’t forget to draw a satisfactory conclusion. Writing may take a lot of your time and energy, so plan ahead. Remember to stay hydrated and good luck!

Now, after we looked through the topic collections on criminology and criminal justice, it is time to turn to the specifics in each of the fields. First, let’s talk more extensively about criminology. If you are training to be a criminologist, you will study some things more deeply. They include the behavior patterns of criminals, their backgrounds, and the latest sociological trends in crime.

Receive a plagiarism-free paper tailored to your instructions. Cut 20% off your first order!

In the field of criminology, the specialties are numerous. That’s why it’s difficult to pinpoint one career that represents a typical member of the profession. It all depends on the background of a criminologist, their education, and experience.

A criminologist may have a number of responsibilities at their position. For example, they might be called forth to investigate a crime scene. Participation in autopsies is unpleasant yet necessary. Interrogation of suspects and subsequent criminal profiling is another essential duty.

Some professionals work solely in research. Others consult government agencies or private security companies. Courts and law firms also cooperate with criminologists. Their job is to provide expert opinion in criminal proceedings. Some of them work in the prison systems in order to oversee the rehabilitation of the convicted.

Regardless of the career specialty , most criminologists are working on profiling and data collection. A criminologist is another word for an analyst. They collect, study, and analyze data on crimes. After conducting the analysis, they provide recommendations and actionable information.

A criminologist seeks to find out the identity of the person who committed the crime. The time point of a crime is also important, as well as the reason for it. There are several areas covered by the analysis of a criminologist. The psychological behavior of the criminal or criminals is closely studied. The socio-economic indicators are taken into account. There are also, of course, the environmental factors that may have facilitated the crime.

Get an originally-written paper according to your instructions!

Some high-profile cases require a criminologist to correspond with media and PR managers extensively. Sometimes criminologists write articles and even books about their findings. However, it should be noted that the daily routine of a professional in the field is not so glamorous. Most criminologists do their work alone, without the attention of the public.

The research a criminologist accumulates during their work is extensive. It doesn’t just sit there in a folder on their desk, of course. The collected statistics are used for developing active criminal profiles that are shared with law enforcement agencies. It helps to understand criminal behavior better and to predict it. That’s why a criminologist’s work must be precise and accurate for it to be practical and useful. Also, criminology professionals must have a good grasp of math and statistics.

Thinking of a career in criminology? You will need to, at the very least, graduate from college. There, you’ll master mathematics, statistics, and, of course, criminology. An associate’s degree may get you an entry-level position. But the minimum entry-level requirement is usually the bachelor’s degree. The best positions, though, are left for the professionals with a master’s degree or a PhD.

Just having a degree is not enough. To succeed as a criminologist, you will require all your intelligence, commitment, and the skill of analyzing intricate situations. An aspiration to better the society will go a long way. You will need to exercise your creative, written, and verbal communication skills, too. An analytical mind will land you at an advantage.

Criminology: Research Areas

Times change and the world of crime never ceases to adapt. The nature of criminal transgression is evolving, and so do the ways of prosecution. Criminal detection, investigation, and prevention are constantly advancing. Criminology studies aim to improve the practices implemented in the field.

There are six unified, coordinated, and interrelated areas of expertise. Within each, the professionals are busy turning their mastery into knowledge and action.

The first research area is the newest worry of criminology – cybercrime. The impact of this type of crime is escalating with every passing day. That’s why it’s crucial for the law enforcement professionals to keep up to date with the evolving technology. Cybercrime research is exploring the growing threat of its subject at all levels of society. Cybercrime may impact people on both personal and governmental levels. Cybercrime research investigates the motivation and methodology behind the offenses and finds new ways to react.

The second research area is counter fraud. Crimes that fall under this category include fraud and corruption. The questions that counter fraud research deals with are many. How widely a crime is spread, what method is best to fight it, and the optimal courses of action to protect people and organizations.

The third research area is that of forensics. The contemporary face of justice has been changed by forensic science beyond recognition. Nowadays, it’s much harder for criminals to conceal their activity due to evolved technologies. The research in forensics is utilizing science in the identification of the crime and in its reconstruction. It employs such techniques as DNA recovery, fingerprinting, and forensic interviewing.

What is forensic interviewing? It helps find new ways to gather quality information from witnesses and crime scenes. It also works on developing protocols that ensure the protection of this human data and its correct interpretation by police.

The fourth research area is policing. Police service is facing a lot of pressing issues nowadays due to budget cuts. At the same time, police officers still need to learn, and there are also individual factors that may influence their work.

The fifth research area is penology. It’s tasked with exploring the role of punishment in the criminal justice system. Does punishment aid the rehabilitation of perpetrators, and to what extent? The answer will help link theory to practice and thus shape how criminal justice practitioners work.

The sixth research area is that of missing persons. Before a person goes missing, they may display a certain pattern of behavior. The study of missing persons helps to identify it. The results will determine the handling of such cases.

Now that we know what criminology is, it’s time to talk about criminal justice.

While criminology focuses on the analysis of crime, criminal justice concentrates on societal systems. Its primary concern is with the criminal behavior of the perpetrators. For example, in the USA, there are three branches of the criminal justice system. They are police (aka law enforcement), courts, and corrections. These branches all work together to punish and prevent unlawful behavior. If you take up a career in criminal justice, expect to work in one of these fields.

The most well-known branch of criminal justice is law enforcement. The police force is at the forefront of defense against crime and misdemeanor. They stand against the criminal element in many ways. For instance, they patrol the streets, investigate crimes, and detain suspects. It’s not just the police officers who take these responsibilities upon themselves. There are also US Marshals, ICE, FBI Agents, DEA, and border patrol. Only after the arrest has been made, the perpetrator enters the court system.

The court system is less visible to the public, but still crucial to the criminal justice system. Its main purpose is to determine the suspect’s innocence or guilt. You can work as an attorney, lawyer, bailiff, judge, or another professional of the field. In the court, if you are a suspect, you are innocent until proven guilty. You are also entitled to a fair trial. However, if they do find you guilty, you will receive a sentence. Your punishment will be the job of the corrections system.

The courts determine the nature of the punishment, and the corrections system enforces it. There are three elements of the corrections system: incarceration, probation, and parole. They either punish or rehabilitate the convicts. Want to uptake a career in corrections? You may work as, including, but not limited to: a parole officer, a prison warden, a probation officer, and a guard.

📈 Criminal Justice: Research Areas

The research areas in criminal justice are similar, if not identical, to those of criminology. After all, those are two very closely related fields. The one difference is that criminal justice research has more practical than theoretical applications. But it’s fair to say that theory is the building blocks that practice bases itself on. One is impossible without the other unless the result you want is complete chaos.

So, the question is – what topic to choose for the research paper? Remember that the world of criminal justice is constantly changing. Choosing a subject for research in criminal justice, consider a relevant topic. There are many pressing issues in the field. Exploring them will undoubtedly win you points from your professor. Just make sure to choose a direction that will give you the opportunity to show off both your knowledge and your analytical skills.

Not sure that your original research direction will be appreciated? Then choose one of the standard topics. Something that is widely discussed in the media. And, of course, make sure that you are truly interested in the subject. Otherwise, your disinterest will translate into your writing, which may negatively affect the overall impression. Also, it’s just more enjoyable to work on something that resonates with you.

What can you do with your research paper? Literally anything. Explore the background of the issue. Make predictions. Compare the different takes on the matter. Maybe there are some fresh new discoveries that have been made recently. What does science say about that?

Also, remember to backup all your arguments with quotes and examples from real life. The Internet is the best library and research ground a student could hope for. The main idea of the paper, aka the thesis, must be proven by enough factual material. Otherwise, it’s best to change your research direction.

And, of course, don’t put it all off till the last minute. Make a plan and stick to it. Consistency and clever distribution of effort will take you a long way. Good luck!

🤔 Criminal Justice Research FAQs

Criminological and criminal justice research are the scientific studies of the causes and consequences, extent and control, nature, management, and prevention of criminal behavior, both on the social and individual levels.

Criminal justice and criminology are sciences that analyze the occurrence and explore the ways of prevention of illegal acts. Any conducted personal research and investigation should be supported by the implemented analytical methods from academic works that describe the given subject.

There are six interrelated areas of criminology research:

- Cybercrime research makes law enforcement professionals keep up to date with the evolving technology.

- Counter fraud research investigates cases of fraud and corruption.

- Forensics research utilizes science: DNA recovery, fingerprinting, and forensic interviewing.

- Research in policing investigates individual factors that may influence the work of police officers.

- Penology explores the role of punishment in the criminal justice system.

- The study of missing persons helps to identify patterns of victims’ behavior.

There are seven research methods in criminology:

- Quantitative research methods measure criminological and criminal justice reality by assigning numerical values to concepts to find patterns of correlation, cause and effect.

- Survey research collects information from a number of persons via their responses to questions.

- Experimental research assesses cause and effect in two comparison groups.

- Cross-sectional research studies one group at one point in time.

- Longitudinal research studies the same group over a period of time.

- Time-series designs study the same group at successive points in time.

- Meta-analysis employs quantitative analysis of findings from multiple studies.

The basis of criminological theory is criminological research. It influences the development of social policies and defines criminal justice practice.

Criminological research doesn’t just enable law students to develop analytical and presentational skills. The works of criminal justice professionals, scholars, and government policymakers dictate the way law enforcement operates. The newest ideas born out of research identify corrections and crime prevention, too.

Here is a step-by-step instruction on how to write a criminal justice research paper:

- Choose a topic

- Read the materials and take notes

- Come up with a thesis

- Create an outline for your work

- Draft the body

- Start with a cover page, an abstract, and an intro

- List the methods you used, and the results you got

- Include a discussion

- Sum it up with a conclusion

- Don’t forget a literature review and appendices

- Revise, proofread, and edit

The most common types of methodologies in criminal justice research include:

- Observation of participants.

- Surveys and interviews.

- Observation of focus groups.

- Conducting experiments.

- Analysis of secondary data and archival study.

- Mixed (a combination of the above methods).

Learn more on this topic:

- 280 Good Nursing Research Topics & Questions

- 204 Research Topics on Technology & Computer Science

- 178 Best Research Titles about Cookery & Food

- 497 Interesting History Topics to Research

- 180 Best Education Research Topics & Ideas

- 110+ Micro- & Macroeconomics Research Topics

- 417 Business Research Topics for ABM Students

- 190+ Research Topics on Psychology & Communication

- 512 Research Topics on HumSS

- 281 Best Health & Medical Research Topics

- 501 Research Questions & Titles about Science

- A List of Research Topics for Students. Unique and Interesting

- Good Research Topics, Titles and Ideas for Your Paper

- The Differences Between Criminal Justice and Criminology: Which Degree Is Right for You? (Concordia St. Paul)

- Corporate Crime: Britannica

- The Development of Delinquency: NAP

- Databases for Research & Education: Gale

- A CS Research Topic Generator: Purdue University

- A Introduction To The Federal Court System: US Department of Justice

- Criminal Justice Research Topics: Broward College

- Research Topics in Criminology: Cambridge Institute of Criminology

- CRIMINOLOGY: University of Portsmouth

- Research: Department of Criminology & Criminal Justice, University of Maryland

- Criminal Justice: RAND

- Research Methods in Criminal Justice: Penn State University Libraries

- Research: School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, Arizona State University

- Criminology – Research Guide: Getting started (Penn Libraries)

- Criminology Research Papers: Academia

- The History & Development of the U.S. Criminal Justice System: Study.com

- CRIMINAL JUSTICE & CRIMINOLOGY: Marshall University

- Criminal Justice: Temple University

- Criminal Justice: University of North Georgia

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

![research essay on criminology Research Proposal Topics: 503 Ideas, Sample, & Guide [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/woman-making-notes-284x153.jpg)

Do you have to write a research proposal and can’t choose one from the professor’s list? This article may be exactly what you need. We will provide you with the most up-to-date undergraduate and postgraduate topic ideas. Moreover, we will share the secrets of the winning research proposal writing. Here,...

A history class can become a jumble of years, dates, odd moments, and names of people who have been dead for centuries. Despite this, you’ll still need to find history topics to write about. You may have no choice! But once in a while, your instructor may let you pick...

![research essay on criminology 150 Argumentative Research Paper Topics [2024 Upd.]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/close-up-magnifier-glass-yellow-background-284x153.jpg)

Argumentative research paper topics are a lot easier to find than to come up with. We always try to make your life easier. That’s why you should feel free to check out this list of the hottest and most controversial argumentative essay topics for 2024. In the article prepared by...

One of the greatest problems of the scholarly world is the lack of funny topics. So why not jazz it up? How about creating one of those humorous speeches the public is always so delighted to listen to? Making a couple of funny informative speech topics or coming up with...

![research essay on criminology Best Childhood Memories Essay Ideas: 94 Narrative Topics [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/child-working-in-cambodia-284x153.jpg)

Many people believe that childhood is the happiest period in a person’s life. It’s not hard to see why. Kids have nothing to care or worry about, have almost no duties or problems, and can hang out with their friends all day long. An essay about childhood gives an opportunity...

![research essay on criminology A List of 272 Informative Speech Topics: Pick Only Awesome Ideas! [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/meeting-room-professional-meeting-284x153.jpg)

Just when you think you’re way past the question “How to write an essay?” another one comes. That’s the thing students desperately Google: “What is an informative speech?” And our custom writing experts are here to help you sort this out. Informative speaking is a speech on a completely new issue....

![research essay on criminology 435 Literary Analysis Essay Topics and Prompts [2024 Upd]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/girl-having-idea-with-copy-space-284x153.jpg)

Literature courses are about two things: reading and writing about what you’ve read. For most students, it’s hard enough to understand great pieces of literature, never mind analyzing them. And with so many books and stories out there, choosing one to write about can be a chore. But you’re in...

![research essay on criminology 335 Unique Essay Topics for College Students [2024 Update]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/smiling-students-walking-after-lessons1-284x153.jpg)

The success of any college essay depends on the topic choice. If you want to impress your instructors, your essay needs to be interesting and unique. Don’t know what to write about? We are here to help you! In this article by our Custom-Writing.org team, you will find 335 interesting...

Social studies is an integrated research field. It includes a range of topics on social science and humanities, such as history, culture, geography, sociology, education, etc. A social studies essay might be assigned to any middle school, high school, or college student. It might seem like a daunting task, but...

If you are about to go into the world of graduate school, then one of the first things you need to do is choose from all the possible dissertation topics available to you. This is no small task. You are likely to spend many years researching your Master’s or Ph.D....

Looking for a good argumentative essay topic? In need of a persuasive idea for a research paper? You’ve found the right page! Academic writing is never easy, whether it is for middle school or college. That’s why there are numerous educational materials on composing an argumentative and persuasive essay, for...

Persuasive speech is the art of convincing the audience to understand and trust your opinion. Are you ready to persuade someone in your view? Our list of sports persuasive speech topics will help you find a position to take and defend. If you need more options quick, apart from contents...

The schools of criminology seems like such a fascinating field — it’s definitely not for the lighthearted though! Here in the Philippines, criminology as a course is highly underrated; hopefully that’ll change!

I understand. Thank you for sharing your thoughts!

158 Criminology Essay Topics

🏆 best essay topics on criminology, ✍️ criminology essay topics for college, 👍 good criminology research topics & essay examples, 🌶️ hot criminology ideas to write about, 🎓 most interesting criminology research titles, 💡 simple criminology essay ideas, ❓ criminology research questions.

- Criminology Discipline and Theories

- Use of Statistics in Criminal Justice and Criminology

- Forensic Science: Killing of JonBenet Ramsey

- Theories of Crime in Forensic Psychology

- Labeling Theory and Critical Criminology: Sociological Research

- Chapter 9 of “Criminology Today” by Schmalleger

- Variance Analysis in Criminal Justice and Criminology

- How the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights Were Influenced by the Classical School of Criminology? In the United States Constitution and bill of rights, many of the fundamental rights used by the citizens originate from classical criminology.

- Robert Merton’s Strain Theory in Criminology Robert Merton’s strain theory explains the link between crime and adverse social conditions and how the former may be precipitated by the latter.

- Criminology and Impact of Automation Technology The sole objective of this study is to determine to what extent automation is embraced by law agencies and authorities to solve crimes with a faster and more accurate technique.

- Feminist Perspectives’ Contribution to Criminology The principles of gender inclusivity, equality, and cultural implications bear fundamental roles in the development of criminology perspectives.

- Criminology as a Science: Cause and Effect Criminology is a study of the nature and degree of the problem of crime in society. For years criminologists have been trying to unravel criminal behavior.

- Correlational Design in Forensic Psychology Correlational designs are actively used in forensic psychology research in order to determine the meaningful relations between different types of variables.

- Criminological Theories on Community-Based Rehabilitation This research study seeks to enhance the collection of integral analysis of human behavior and legal framework that boosts the quality of information for rehabilitation.

- Forensic Psychology and Criminal Profiling The paper seeks to explore insight into the nature of criminal investigative psychology and a comprehensive evaluation of the practice in solving crime.

- Juvenile Forensic Psychology: Contemporary Concern The present juvenile forensic psychology system has many pitfalls that have compromised the wellbeing and development of the young offenders admitted within these institutions.

- Criminology and Victimology: Victim Stereotypes in Criminal Justice The paper shall look at this matter in relation to female perpetrated violence as well as male experiences of sexual violence and racial minority victims.

- Criminology: Femininity and the Upsurge of Ladettes In recent years, women in highly industrialized countries are drinking more and behaving more badly than men. These women are called ladettes.

- Experimental Psychology and Forensic Psychology Psychology is a powerful field of study aimed at addressing a wide range of human problems. The field can be divided into two specialties. These include experimental and forensic psychology.

- Integrity as a Key Value: Criminology and War Integrity is included in the list of the LEADERSHIP values, which exist to direct military servicemembers toward appropriate conduct.

- Chapter 8 of “Criminology Today” by F. Schmalleger According to social process theories, criminal behavior that an individual acquires remains lifelong because it is strengthened by the same social issues that have caused it.

- Full-Service Crime Laboratory: Forensic Science Forensic scientists study and analyze evidence from crime scenes and other locations to produce objective results that can aid in the investigation and prosecution of criminals.

- Three Case Briefs in Criminology This paper gives three case briefs in criminology. Cases are “Macomber v. Dillman Case”, “Isbell v. Brighton Area Schools Case”, and “Wilen v. Falkenstein Case”.

- Ethical Issues in Forensic Psychology Psychologists face many moral dilemmas in law due to the field’s nature because they are responsible for deciding people’s fates, which puts pressure on them.

- Hernando Washington Case. Criminology The history of humanity has seen multiple cases of extreme violence, and such instances can hardly ever be justified by any factors.

- Stabbing Cases in London in Relation to Durkheim’s Criminological Theory The two main questions about criminal and deviant acts are what constitutes such an act and whether it should be punished.

- Classical and Positivist Schools of Criminology General and specific deterrence use the threat of negative consequences for illegal acts to reduce crime rates.

- Criminology: The Peace-Making Model The purpose of this article is to consider the peacekeeping model in criminology as an alternative to the criminal justice system to solve the problem of a growing crime rate.

- Criminological Theory: Crime Theories and Criminal Behavior Criminal behavior is a type of behavior of a person who commits a crime. It is interesting to know what drives people to commit crimes and how to control these intentions.

- Analysis of Forensic Psychology Practice The important feature of the whole sphere of forensic psychology practice is the ability to testify in court, reformulating psychological findings into the legal language, etc

- Contemporary Theories in Criminology This paper discusses three methods of measuring crimes, Classical School of criminology and its impacts on the US criminology, and the causes of crime – individuality and society.

- The Rise of Criminological Conflict Theory Three key factors that explain the emergence of conflict theory are the influence of the Vietnam War, the rise of the counterculture, and anti-discrimination movements.

- “Criminological Theory: Context and Consequences” the Book by Lilly, J., Cullen, F., & Ball, R. Criminological Theory addresses not only the evolving and expanding topic of trends in criminological thought but also tries to achieve a level of explanation.

- Feminism and Criminology in the Modern Justice System Feminist research is a promising method for studying the psychography of crime, motivation, and the introduction of women’s experience in the field of forensic science.

- Criminology Today by Frank Schmalleger This paper discusses the first chapter from the book Criminology Today by Schmalleger that tells about the basic topics and defines the basic term.

- Incorporating Criminological Theories Into Policymaking Criminological theories, primarily behavioral and social learning, are pivotal to the policymaking process. They provide insights into certain situations.

- Researching Environmental Criminology Environmental criminology is the study of crime and criminality in connection with specific places and with how individuals and organizations form their activities in space.

- Chapter 7 of Statistics for Criminology and Criminal Justice Chapter 7 of Statistics for Criminology and Criminal Justice analyzes populations, sampling distributions, and the sample related to criminal-justice statistics and criminology.

- Extinction Rebellion: A Criminological Assessment The paper aims at exploring whether Extinction Rebellion protestors are criminals using the narrative criminology framework, transgression theory, and green criminology theory.

- Forensic Psychology: Subspecialties and Roles Of my specific interests have been basically two subspecialties of forensic psychology. These include correctional psychology as well as police psychology.

- Statistical Significance and Effect Size in Forensic Psychology Nee and Farman evaluated the effectiveness of using dialectical behavior therapy for treating borderline personality disorder in the UK female prisons.

- Forensic Psychology and Its Essential Feature in the Modern World The essay defines the origins of forensic psychology, analyzes its role in various fields and spheres, and identifies its essential feature in the modern world.

- The Use of Statistics in Criminal Justice and Criminology This paper discusses small-sample confidence intervals for means and confidence intervals with proportions and percentages in criminal justice and criminology.

- Criminological Conflict Theory by Sykes Sykes identified three important elements, which he used to elucidate the criminological conflict theory. Sykes highlighted the existence of profound skepticism towards any theory.

- Postmodern Criminology: The Violence of the Language According to Arrigo (2019), postmodern criminology recognizes the specific value of language as a non-neutral, politically charged instrument of communication.

- Forensic Psychology: Graham v. Florida and Sullivan v. Florida The question in the two cases Graham v. Florida and Sullivan v. Florida was juvenile sentencing. The offenders claimed their life prison sentences for rape and robbery.

- Researching of Emerging Technologies in Criminology This paper reviews the advantages and disadvantages of computer technology for crime investigation and law enforcement and concludes that the former outweighs the latter.

- Criminology: Legal Rights Afforded to the Accused The essay discusses the police actions of arrest and the main features of the arrangement process. The case of John Doe shows criminal procedure specifics.

- Statistics for Criminology and Criminal Justice Dispersion is important as it is not enough to merely know the measures of central tendency to make assumptions about a distribution.

- “Introduction to Criminology” Book by Hagan In “Introduction to criminology”, Hagan explains survey research and uses it to investigate essential questions that the criminal justice system faces.

- Overview of the Theories of Criminology Criminology refers to a body that focuses on crime as a social phenomenon. Criminologists adopt several behavioral and social sciences and methods of understanding crime.

- Broken Window Theory In Criminology In criminology, the broken window theory is often used to describe how bringing order into society can help to reduce crime.

- Sexual Assault: Criminology This paper discusses an act of sexual assault. The paper gives the definition of rape, social, personal, and psychosocial factors.

- Marxist Criminological Paradigm The essence of the Marxist criminological paradigm consists of overthrowing the bourgeoisie, as a ruling class, and establishing the so-called dictatorship of the proletariat.

- Theories That Explain Criminal Activities and Criminology Academicians have come up with theories that explain why people engage in crime. The theories are classified which may be psychological, biological, or sociological.

- Criminology: The Aboriginal Crisis The aboriginal people have been living under confinement, in the reserves for a long time. These laws are still under a lot of legal constraints.

- Are Marxist Criminologists Right to See Crime Control as Class Control? Marxist criminology is comparable to functionalist theories, which lay emphasis on the production of continuity and stability in any society.

- Forensic Science: Psychological Analysis Human behavior can be evaluated by studying the functioning of the human mind. This is important information in crime profiling among other operations in forensic psychology.

- Criminology: USA Patriot Act Overview The Act strengthens and gives more authority to the federal agencies over individual privacy and secrecy of information.

- Criminology: About Corporate Fraud This article focuses on fraud: professional fraud and its types, accounting fraud, and conflicts of interest are considered.

- The Due Process: Criminology The due process clause has been a very essential clause to the ordinary citizens since it is a means of assurance that every freeman has the freedom to enjoy his rights.

- Green Criminology: Environmental Harm in the Niger Delta This essay analyzes environmental harm in the Niger Delta, Nigeria using the Green Criminological analysis of victimization and offenders.

- Criminology: Four Types of Evidence There are basically four types of evidence. Every piece of evidence should be analyzed several times throughout the actual investigation by following all the required steps.

- Criminology: The Social Control Theory For criminologists, the social control theory means that an effective approach to reducing crime might be to change not individuals but their social contexts.

- Forensic Psychology Practice Standards for Inmates It is vital for the inmates to have frequent access to psychological assessments because the majority of the inmates end up with psychological problems.

- The Role of Forensic Psychology in the Investigation Confidentiality is an essential feature of a therapeutic bond. Forensic psychologists are bound by a code of ethics to safeguard clients’ information.

- Violence Potential Assessment in Forensic Psychiatric Institutions This paper aims to discuss the ways of predicting violence in forensic psychiatric institutions while focusing on the review of the recent research in the field.

- Legal Insanity in Criminology In America, defendants are said to be legally insane if they suffer from cognitive disorder or lack the capabilities to abstain from criminal behaviors.

- Forensic Psychology in the Correctional Subspecialty Psychological professionals have the role of ensuring that the released convicts have gathered enough knowledge and understanding for them to fit in the society.

- Criminological Theories Assessment and Personal Criminological Theory This essay aims to briefly cover the various criminological theories in vogue and offer the author’s own assessment as to which theory deserves greater credibility.

- Criminological Theory: Context and Consequences. The Notion of Criminality and Crime The exploration of the notion of criminality and crime is essential for the prevention and management thereof.

- Criminological Theory: Context and Consequences The theory of social control seems logical and valid despite controversies and the diversity of theoretical approaches to the reasons of crime.

- “Criminological Theory: Context and Consequences”: Evaluation The criminal law system works in such a way that all offenses are stopped, and corresponding penalties provided by the law are implemented.

- Chapter 10 of “Criminological Theory” by Lilly et al. This paper elaborates on the problem of feminism and criminology. The paper addresses chapter 10 of the book “Criminological Theory” by Lilly et al. as the source material.

- Linguistics and Law: Forensic Letters This paper review articles The Multi-Genre Analysis of Barrister’s Opinion by Hafner and Professional Citation Practices in Child Maltreatment Forensic Letters by Schryer et al.

- Frank Hagan’s Textbook “Introduction to Criminology” Throughout the chapters, Frank Hagan deliberately made reference to positivism criminological theory as such, which was largely discredited.

- Forensic Psychology: Important Issues Forensic psychologists consider that task of determining insanity extremely difficult. There is a difference between insanity as a psychological condition and a legal concept.

- The American Psychological Association: Forensic Field Forensic psychologists are commonly invited to provide expert consultation and share their observations that might be useful to the judicial system.

- Transnational Crime and Global Criminology: Definitional, Typological, and Contextual Conundrums

- Rational Choice, Deterrence, and Social Learning Theory in Criminology

- Comparing Cultures and Crime: Challenges, Prospects, and Problems for a Global Criminology

- The Distinction Between Conflict and Radical Criminology

- How the Study of Political Extremism Has Reshaped Criminology

- Contribution of Positivist Criminology to the Understanding of the Causes of Crime

- Overcoming the Neglect of Social Process in Cross‐National and Comparative Criminology

- The Development of Criminology: From Traditional to Contemporary Views on Crime and Its Causation

- Racism, Ethnicity, and Criminology: Developing Minority Perspectives

- Activist Criminology: Criminologists’ Responsibility to Advocate for Social and Legal Justice

- The Challenges of Doing Criminology in the Big Data Era: Towards a Digital and Data-Driven Approach

- Radical Criminology and Marxism: A Fallible Relationship

- Ontological Shift in Classical Criminology: Engagement With the New Sciences

- Hot Spots of Predatory Crime: Routine Activities and the Criminology of Place

- The Criminology of Genocide: The Death and Rape of Darfur

- Future Applications of Big Data in Environmental Criminology

- Overcoming the Crisis in Critical Criminology: Toward a Grounded Labeling Theory

- Toward an Analytical Criminology: The Micro-Macro Problem, Causal Mechanisms, and Public Policy

- The Utility of the Deviant Case in the Development of Criminological Theory

- In Search of a Critical Mass: Do Black Lives Matter in Criminology?

- Crime and Criminology in the Eye of the Novelist: Trends in the 19th Century Literature

- Income Inequality and Homicide Rates: Cross-National Data and Criminological Theories

- Women & Crime: The Failure of Traditional Theories and the Rise of Feminist Criminology

- Criminology Studies: How Fear of Crime Affects Punitive Attitudes

- Recent Developments in Criminological Theory: Toward Disciplinary Diversity and Theoretical Integration

- Critical Criminology: The Critique of Domination, Inequality, and Injustice

- Anti-racism in Criminology: An Oxymoron?

- Heredity or Milieu: The Foundations of Modern European Criminological Theory

- Classical and Contemporary Criminological Theory in Understanding Young People’s Drug Use

- Theories of Action in Criminology: Learning Theory and Rational Choice Approaches

- Criminalization or Instrumentalism: New Trends in the Field of Border Criminology

- Eco-Justice and the Moral Fissures of Green Criminology

- The Impact of Criminological Theory on Community Corrections Practice

- Feminism and Critical Criminology: Confronting Genealogies

- Learning From Criminals: Active Offender Research for Criminology

- Offending Patterns in Developmental and Life-Course Criminology

- Big Data and Criminology From an AI Perspective

- Psychological and Criminological Factors Associated With Desistance From Violence

- Connecting Criminology and Sociology of Health & Illness

- Assessment of the Current Status and Future Directions in Criminology

- Using Basic Neurobiological Measures in Criminological Research

- Green Criminology: Capitalism, Green Crime & Justice, and Environmental Destruction

- The Foundation and Re‐Emergence of Classical Thought in Criminological Theory

- Conservation Criminology, Environmental Crime, and Risk: An Application to Climate Change

- Feminist and Queer Criminology: A Vital Place for Theorizing LGBTQ Youth

- Criminological Fiction: What Is It Good For?

- Investigating the Applicability of Macro-Level Criminology Theory to Terrorism

- Criminological Theory in Understanding of Cybercrime Offending and Victimization

- The Nurture Versus Biosocial Debate in Criminology

- Developmental Theories and Criminometric Methods in Modern Criminology

- How Does Criminology Cooperate With Other Disciplines to Solve Crimes?

- Is Criminology a Social or Behavioral Science?

- How Does the Study of Criminology Relate to the Detection or Deterrence of Fraud?

- What Are the Types of Norms in Criminology?

- How Do Criminology Schools Differ?

- What Is Criminological Research?

- How Important Is the Role of Punishment in Neoclassical Criminology?

- What Is the Life Course Theory of Criminology?

- Who Is the Father of Modern Criminology?

- What Did Early Criminology Focus On?

- What Is the Difference Between Classical and Positivist Schools of Criminology?

- Why Is Personal Identification Necessary for Criminology?

- What Is the Difference Between Criminology and Applied Criminology?

- What Is Evidence-Based Criminology?

- Are Criminology and Criminal Justice the Same?

- Who Rejected the Doctrine of Free Will in Criminology?

- What Are the Fundamental Propositions of Feminist Criminology?

- Is There a Difference Between Criminology and Victimology?

- What Is the Bell Curve in Criminology?

- Why Do People Commit Crimes, According to Criminology?

- What Is the Difference Between Criminology and Criminal Psychology?

- What Is Contemporary Criminology?

- How Do Criminological Theories Relate to White Collar Crime?

- What Are the Main Features and Concepts of Classical Criminology?

- What Is the Positivist School of Criminology?

- Who Are the Forerunners of Classical Thought in Criminology?

- What Role Does Attachment Theory Play in Criminology?

- Why Do Sociological Criminology Theories Help With Our Understanding of Crimes?

- How Is Victimization Used in Criminology?

- What Is Albert Cohen’s Theory of Subculture Formation in Criminology?

Cite this post

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2023, May 7). 158 Criminology Essay Topics. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/criminology-essay-topics/

"158 Criminology Essay Topics." StudyCorgi , 7 May 2023, studycorgi.com/ideas/criminology-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . (2023) '158 Criminology Essay Topics'. 7 May.

1. StudyCorgi . "158 Criminology Essay Topics." May 7, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/criminology-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "158 Criminology Essay Topics." May 7, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/criminology-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . 2023. "158 Criminology Essay Topics." May 7, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/criminology-essay-topics/.

These essay examples and topics on Criminology were carefully selected by the StudyCorgi editorial team. They meet our highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, and fact accuracy. Please ensure you properly reference the materials if you’re using them to write your assignment.

This essay topic collection was updated on December 27, 2023 .

- Open access

- Published: 12 August 2014

Innovative data collection methods in criminological research: editorial introduction

- Jean-Louis van Gelder 1 &

- Stijn Van Daele 2

Crime Science volume 3 , Article number: 6 ( 2014 ) Cite this article

23k Accesses

11 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Novel technologies, such as GPS, the Internet and virtual environments are not only rapidly becoming an increasingly influential part of our daily lives, they also have tremendous potential for improving our understanding of where, when and why crime occurs. In addition to these technologies, several innovative research methods, such as neuropsychological measurements and time-space budgets, have emerged in recent years. While often highly accessible and relevant for crime research, these technologies and methods are currently underutilized by criminologists who still tend to rely on traditional data-collection methods, such as systematic observation and surveys.

The contributions in this special issue of Crime Science explore the potential of several innovative research methods and novel technologies for crime research to acquaint criminologists with these methods so that they can apply them in their own research. Each contribution deals with a specific technology or method, gives an overview and reviews the relevant literature. In addition, each article provides useful suggestions about new ways in which the technology or method can be applied in future research. The technologies describe software and hardware that is widely available to the consumer (e.g. GPS technology) and that sometimes can even be used free of charge (e.g., Google Street View). We hope this special issue, which has its origins in a recent initiative of the Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement (NSCR) called CRIME Lab, and a collaborative workshop together with the Research consortium Crime, Criminology and Criminal Policy of Ghent University, will inspire researchers to start using innovative methods and novel technologies in their own research.

Issues and challenges facing crime researchers

Applied methods of scientific research depend on a variety of factors that play out at least in part beyond researcher control. One such factor regards the nature and availability of data, which largely determines the research questions that can be addressed: Data that cannot be collected cannot serve to answer a research question. Although this may seem like stating the obvious, it has had and continues to have far-reaching implications for criminological research. Because crime tends to be a covert activity and offenders have every interest in keeping it that way, crime in action can rarely be observed, let alone in such a way as to allow for systematic empirical study. Consequently, our knowledge of the actual offending process is still limited and relies in large part on indirect evidence. The same applies to offender motivations and the offending process; these cannot be measured directly in ways similar to how we can observe say the development of a chemical process or the workings of gravity. This has placed significant restrictions on the way crime research has been performed over the years, and most likely has coloured our view of crime and criminality by directing our gaze towards certain more visible elements such as offender backgrounds, demographics and criminal careers.

Another factor operating outside of researcher control regards the fact that the success of scientific analyses hinges on the technical possibilities to perform them. Even if researchers have access to particular data, this does not guarantee that the technology to perform the analysis in the best possible way is available to them. The complexity of the social sciences and the interconnectivity of various social phenomena, together with the lack of a controlled environment or laboratory, require substantial computational power to test highly complicated models. For instance, the use of space-time budgets, social network analysis or agent-based modelling can be quite resource-intensive. Adding the complexity of social reality to the resulting datasets (e.g. background variables related to social structure, GIS to incorporate actual road networks, etc.) puts high pressure on the available computational power of regular contemporary desktop computers. Addressing these challenges has practical and financial consequences, which brings us to the third issue, which although more mundane in nature is by no means limited to the applied sciences: a researcher requires the financial and non-financial resources to be able to perform his research.

All three factors have a bearing on the contents and goals of the present special issue. More specifically, the methods that are discussed and explained in different articles in this special issue each address one or more of these factors and have, we believe, the potential to radically change the way we think about crime and go about doing crime research. The methods and technologies are available, feasible and affordable. They are, so to speak, there for the taking.

Notes on criminological research methods

The above factors have contributed to a general tendency within criminology to stick to particular research traditions, both in terms of method and analysis. Although these traditions are well-developed and have undergone substantial improvement over the decades, most changes in the way research is performed in the discipline have been of the ’more of the same‘ variety, and most involve gradual improvements, rather than embodying ‘scientific revolutions’ and ‘paradigm shifts’ that have radically changed how criminologists go about doing research and thinking about crime.

With respect to methodology, since the field's genesis in the early 20th century, research in criminology has largely spawned studies using similar methods. In a meta-analysis of articles that have appeared in seven leading criminology and criminal justice journals in 2001-2002, Kleck et al. ([ 2006 ]) demonstrate that survey research is still the dominant method of collecting information (45.1%), followed by the use of archival data (31.8%), and official statistics (25.6%). Other methods, such as interviews, ethnographies and systematic observation, each account for less than 10% (as methods are sometimes combined the percentages add up to more than 100%). Furthermore, the Kleck et al. meta-analysis shows that as far as data analysis is concerned, nearly three quarters (72.5%) of the articles published uses some type of multivariate statistics. As such, it appears that criminology has developed a research tradition that started to dominate the field, though not to everybody's enthusiasm. Berk ([ 2010 ]), for example, states that regression analysis, in its broad conception, has become so dominant that researchers give it more credit than they sometimes should and take some of its possibilities for granted. Whereas certain research traditions may have a strong added value, they run the risk of being used more out of habit than for being the most appropriate method to answer a particular research question. As innovation influences our daily lives and how we perform our daily activities, there is no reason why it should not influence our way of performing science as well.

Innovation and technology in daily life and their application in criminological research

Novel technologies, such as GPS, the Internet, and virtual environments are rapidly establishing themselves as ingrained elements of our daily lives. Think, for example, of smart phones. While unknown to most of us as recently as ten years ago, today few people would leave their home without carrying one with them. Through their ability to, for example, transmit visual and written communication, use social media, locate ourselves and others through apps and GPS, smart phone technology has radically changed the way we go about our daily routines. The research potential of smart phone technology for improving our understanding of social phenomena is enormous and includes a better understanding of where, when and why crime occurs through automated data collection, interactive tests and surveys (Miller [ 2012 ]). Yet, so far surprisingly few crime researchers have picked up on the possibilities this technology has to offer.

A similar point can be made with respect to the Internet. While most researchers have made the transition from paper-and-pencil questionnaires to online surveys and online research panels may have become the norm for collecting community sample data, much of the potential of the Internet for crime research remains untapped. Think, for example, of the possibility of using Google Maps and Google Street View for studying spatial aspects of crime and the ease with which we can virtually travel down most of the roads and streets to examine street corners, buildings and neighbourhoods. The launch of Google Street View in Belgium stirred up controversy because it was perceived by police officers as a catalogue for burglars and was expected to lead to an increase in the number of burglaries. While it is not clear whether this has actually happened, crime studies reporting these tools in their method sections are few and far between.

In addition to novel technologies, several innovative research methods, such as social network analysis, time-space budgets, and neuropsychological measures that can tap into people's physiological and mental state, have emerged in recent years and have become common elements of the tool-set used in some of criminology's sister disciplines, such as sociology, psychology and neuroscience. Again, while often highly accessible and relevant for crime research, these methods are currently underutilized by crime researchers. The promising and emerging field of neurocriminology is an important exception in this respect (see e.g., Glenn & Raine [ 2014 ]).

To revert back to the three issues that have restricted the gaze of criminology mentioned at the outset of this article: accessibility of data, type of data analysis, and availability of resources, the new methods and technologies seem to check all the boxes. Much more data have become accessible for analysis through novel technologies, new methods for data-analysis and data-collection have been developed, and most of it is available at the consumer level. In other words, this allows for collecting and examining data in ways that go far beyond what we are used to in crime research. For example, methods combining neurobiological measurements with virtual environments can tell us a lot about an individual's mental and physical states and how they go about making criminal decisions, which were until recently largely black boxes. Finally, novel technologies are often available on the consumer market, such as smart phones, tablets, and digital cameras, and require only very modest research budgets. In some cases, such as the automated analysis of footage made by security cameras, simulations, or the use of honeypots that lure cyber criminals into hacking them, they even allow for systematically examining crime in action.

Goals of this special issue of Crime Science

The principal aim of the present special issue is to acquaint crime researchers and criminology students with some of these technologies and methods and explain how they can be used in crime research. While widely diverging, what these technologies and methods have in common is their accessibility and potential for furthering our understanding of crime and criminal behavior. The idea, in other words, is to explore the potential of innovative research methods of data-collection and novel technologies for crime research and to acquaint readers with these methods so that they can apply them in their own research.

Each article deals with a specific technology or method and is set-up in such a way as to give readers an overview of the specific technology/method at hand, i.e., what it is about, why to use it and how to do so, and a discussion of relevant literature on the topic. Furthermore, when relevant, articles contain technical information regarding the tools that are currently available and how they can be obtained. Case studies also feature in each article, giving readers a clearer picture of what is at stake. Finally, we have encouraged all contributors to give their views on possible future developments with the specific technology or method they describe and to make a prediction regarding the direction their field could or should develop. We sincerely hope this will inspire readers to apply these methods in their own work.

While not intended as a manual, after reading an article, readers should not only have a clear view of what the method/technology entails but also of how to use it, possibly in combination with one or more of the references that are provided in the annotated bibliography provided at the end of each article. The contributions may also be useful for researchers already working with a specific method or students interested in research methodology.

Article overview

Hoeben, Bernasco and Pauwels discuss the space-time budget method. This method aims at retrospectively recording on an hour-by-hour basis the whereabouts and activities of respondents, including crime and victimization. The method offers a number of advantages over existing methods for data-collection on crime and victimization such as the possibility of studying situational causes of crime or victimization, possibly in combination with individual lifestyles, routine activities and similar theoretical concepts. Furthermore, the space-time budget method offers the possibility of collecting information on spatial location, which enables the study of a respondent's whereabouts, going beyond the traditional focus of ecological criminological studies on residential neighborhoods. Finally, the collected spatial information on the location of individuals can be combined with data on neighborhood characteristics from other sources, which enables the empirical testing of a variety of ecological criminological theories.

The contribution of Gerritsen focuses on the possibilities offered by agent-based modeling, a technique borrowed from the domain of Artificial Intelligence. Agent-based modeling (ABM) is a computational method that enables a researcher to create, analyse and experiment with models composed of agents that interact within a computational environment. Gerritsen explains how modeling and simulation techniques may help gain more insight into (informal) criminological theories without having to experiment with these phenomena in the real world. For example, to study the effect of bystander presence on norm violation, an ‘artificial neighborhood’ can be developed that is inhabited by 'virtual aggressors and victims’, and by manipulating the agents’ parameters different hypothetical scenarios may be explored. This enables criminologists to investigate complex processes in a relatively fast and cheap manner.