Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Eating Disorders: Current Knowledge and Treatment Update

- B. Timothy Walsh , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

Although relatively uncommon, eating disorders remain an important concern for clinicians and researchers as well as the general public, as highlighted by the recent depiction of Princess Diana’s struggles with bulimia in “The Crown.” This brief review will examine recent findings regarding the diagnosis, epidemiology, neurobiology, and treatment of eating disorders.

Eight years ago, DSM-5 made major changes to the diagnostic criteria for eating disorders. A major problem in DSM-IV ’s criteria was that only two eating disorders, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, were officially recognized. Therefore, many patients presenting for treatment received the nonspecific diagnostic label of eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS), which provided little information about the nature of the patient’s difficulties. This problem was addressed in several ways in DSM-5 (see DSM-5 Feeding and Eating Disorder list). The diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa were slightly expanded to capture a few more patients in each category. But two other changes had a greater impact in reducing the use of nonspecific diagnoses.

The first of these was the addition of binge eating disorder (BED), which had previously been described in an appendix of DSM-IV . BED is the most common eating disorder in the United States, so its official recognition in DSM-5 led to a substantial reduction in the need for nonspecific diagnoses.

DSM-5 Feeding and Eating Disorder

Rumination Disorder

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder

Anorexia nervosa

Bulimia nervosa

Binge-eating disorder

Other specified feeding or eating disorder

Unspecified feeding or eating disorder

The second important change was the combination of the DSM-IV section titled “Feeding and Eating Disorders of Infancy or Early Childhood” with “Eating Disorders” to form an expanded section, “Feeding and Eating Disorders.” This change thereby included three diagnostic categories: pica, rumination disorder, and feeding disorder of infancy or early childhood. Pica and rumination disorder are infrequently diagnosed.

The other category, feeding disorder of infancy or early childhood, was rarely used and had been the subject of virtually no research since its inclusion in DSM-IV . The Eating Disorders Work Group responsible for reviewing the criteria for eating disorders for DSM-5 realized that there was a substantial number of individuals, many of them children, who severely restricted their food intake but did not have anorexia nervosa. For example, after a severe bout of vomiting after eating, some individuals attempt to prevent a recurrence by no longer eating at all, leading to potentially serious nutritional disturbances. No diagnostic category in DSM-IV existed for such individuals. Therefore, the DSM-IV category, feeding disorder of infancy or early childhood, was expanded and retitled “avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder” (ARFID). Combined, these changes led to a substantial reduction in the need for nonspecific diagnostic categories for eating disorders.

In the course of assessing the impact of the recommended changes in the diagnostic criteria for eating disorders, the Eating Disorders Work Group became aware of another group of individuals presenting for clinical care whose symptoms did not quite fit any of the existing or proposed categories. These were individuals, many of them previously overweight or obese, who had lost a substantial amount of weight and developed many of the signs and symptoms characteristic of anorexia nervosa. However, at the time of presentation, their weights remained within or above the normal range, therefore not satisfying the first diagnostic criterion for anorexia nervosa. The work group recommended that a brief description of such individuals be included in the DSM-5 diagnostic category that replaced DSM-IV ’s EDNOS: “other specified feeding and eating disorders” (OSFED); this description was labeled atypical anorexia nervosa. The degree to which the symptoms, complications, and course of individuals with atypical anorexia nervosa resemble and differ from those of individuals with typical anorexia nervosa remains an important focus of current research.

Epidemiology

Although eating disorders contribute significantly to the global burden of disease, they remain relatively uncommon. A study published in September 2018 by Tomoko Udo, Ph.D., and Carlos M. Grilo, Ph.D., in Biological Psychiatry examined data from a large, nationally representative sample of over 36,000 U.S. adults 18 years of age and older surveyed using a lay-administered diagnostic interview in 2012-2013. The 12-month prevalence estimates for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and BED were 0.05%, 0.14%, and 0.44%, respectively. Although the relative frequencies of these disorders were similar to those described in prior studies, the absolute estimates were somewhat lower for unclear reasons. Consistent with clinical experience and prior reports, the eating disorders, especially anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, were more prevalent among women (though men are also affected). Although eating disorders occurred across all ethnic and racial groups, there were fewer cases of anorexia nervosa among non-Hispanic and Hispanic Black respondents than among non-Hispanic White respondents. Consistent with long-standing clinical impression, individuals with lifetime anorexia nervosa reported higher incomes.

Finally, when BED was under consideration for official recognition in DSM-5 , some critics suggested that, since virtually everyone occasionally overeats, BED was an example of the misguided tendency of DSM to pathologize normal behavior. The low prevalence of BED reported in the study by Udo and Grilo documents that, when carefully assessed, BED affects only a minority of individuals and is therefore distinct from normality.

A subject of some debate and substantial uncertainty is whether the incidence of eating disorders (the number of new cases a year) is increasing. Some studies, such as that of Udo and Grilo, have found that the lifetime rates of eating disorders among older individuals are lower than those among younger individuals, suggesting that the frequency of eating disorders may be increasing. However, this might also reflect more recent awareness and knowledge of eating disorders. Other studies that conducted multiple examinations of the frequency of eating disorders in the same settings over time appear to suggest that, in the last several decades, the incidence of anorexia nervosa has remained roughly stable, whereas the incidence of bulimia nervosa has decreased. Presumably, this reflects changes in the sociocultural environment such as an increased acceptance of being overweight and reduced pressure to engage in inappropriate compensatory measures such as self-induced vomiting after binge eating.

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted virtually every facet of life across the world and has produced severe financial, medical, and psychological stresses. Preliminary research suggests that such stresses have exacerbated the symptoms of individuals with preexisting eating disorders and have led to increased binge eating in the general population. Hopefully, these trends will improve with successful control of the pandemic.

Neurobiology

Much recent research on the mechanisms underlying the development and persistence of eating disorders has focused on the processing of rewarding and nonrewarding/punishing stimuli. Several studies have suggested that individuals with anorexia nervosa are less able to distinguish among stimuli with varying probabilities of obtaining a reward. Other studies suggest that, when viewing images of food during MRI scanning, individuals with anorexia nervosa tend to show less activation of brain reward areas than do controls. Such deficits may be related to disturbances in dopamine function in areas of the brain known to be involved in reward processing. Research based on emerging methods in computational psychiatry suggests that individuals with anorexia nervosa may be particularly sensitive to learning from punishment; for example, they may be very quick to learn what stimuli lead to a decrease in the amount of a reward. Conceivably, they may learn that eating high-fat foods prevents weight loss and produces undesirable weight gain, and they begin to avoid such foods. These studies, and a range of others, focus on probing basic brain mechanisms and how they may be disrupted in anorexia nervosa. A challenge for this “bottom-up” approach is to determine how exactly disturbances in such mechanisms are related to the eating disturbances characteristic of anorexia nervosa.

Other recent studies take a “top-down” approach, focusing on the neural circuitry underlying the persistent maladaptive choices made by individuals with anorexia nervosa when they decide what foods to eat. Such research successfully captures the well-established avoidance of high-fat foods by individuals with anorexia nervosa and has documented that such individuals utilize different neural circuits in making decisions about what to eat than do healthy individuals. These results are consistent with suggestions that the impressive persistence of anorexia nervosa in many individuals may be due to the establishment of automatic, stereotyped, and habitual behavior surrounding food choice. A challenge for such top-down research strategies is to determine how these maladaptive patterns develop so rapidly and become so ingrained.

Research on the neurobiology underlying bulimia nervosa is broadly similar. Although the results are complex, individuals with bulimia nervosa appear to find food stimuli more rewarding, and there are indications of disturbances in reward responsiveness to sweet tastes. Several studies have documented impairments in impulse control assessed using behavioral paradigms such as the Stroop Task. In this task, individuals are presented with a word naming a color (for example, “red”) but asked to name the color of the letters spelling the word (for example, the letters r, e, and d are green). Increased difficulties in performing such tasks have been described in individuals with bulimia nervosa and linked to reduced prefrontal cortical thickness.

It has long been known that eating disorders tend to run in families, and there has been strong evidence that this in part reflects the genes that individuals inherit from their parents. In recent decades, it has become clear that the risk of developing most complex human diseases, including obesity, hypertension, and eating disorders is related to many genes, each one of which contributes a small amount to the risk. Because the contribution of a single gene is so small, the DNA from a very large number of individuals with and without the disorder needs to be examined. For instance, genomewide association studies (GWAS) in schizophrenia have examined tens of thousands of individuals with schizophrenia and over 100,000 controls and identified well over 100 genetic loci that contribute to the risk of developing schizophrenia.

GWAS examining the genetic risk for eating disorders are under way but to date have focused primarily on anorexia nervosa. The Psychiatric Genetics Consortium has collected information from 10,000 to 20,000 individuals with anorexia nervosa and over 50,000 controls and has, so far, identified eight loci that contribute to the genetic risk for this disorder. In addition, this work has identified genetic correlations between anorexia nervosa and a range of other disorders known to be comorbid with anorexia nervosa such as anxiety disorders as well as a negative genetic correlation with obesity. These data suggest that the genetic risk for anorexia nervosa is based on a complex interplay between loci associated with a range of psychological and metabolic/anthropometric traits.

Although there have been no dramatic developments in our knowledge of how best to treat individuals with eating disorders, there have been some significant and useful advances in recent years.

For anorexia nervosa, arguably the most significant advance in treatment in the last quarter century has been family-based treatment for adolescents. In this approach, sometimes referred to as the “Maudsley method,” the family, guided by the therapist, becomes the primary agent of change and responsible for ensuring that eating behavior normalizes and weight increases. This approach differs markedly from prior treatment strategies that assumed parental involvement was not helpful or even detrimental. Family-based treatment is now widely viewed as a treatment of first choice for adolescents with anorexia nervosa and has also been adapted to treat bulimia nervosa.

Family-based treatment can be quite challenging for parents. The entire family is asked to attend treatment sessions, and one session early in treatment includes a family meal during which the parents are charged with the difficult task of persuading the adolescent to consume more food than he/she had intended. An alternative but related model, termed “parent-focused treatment,” has recently been explored in a few studies. In this approach, parents meet with a therapist without the affected adolescent or other members of the family and receive guidance regarding how to help the adolescent to alter his or her behavior following techniques virtually identical to those provided in traditional family-based treatment. Several small studies have examined this approach, and results suggest similar effectiveness. Although more research is needed, these findings suggest that parent-focused treatment may be an attractive alternative to family-based treatment for many parents and practitioners.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a dramatic acceleration in the provision of psychiatric care remotely, including family-based treatment. Work on providing family-based treatment via videoconference had begun prior to the arrival of COVID-19, as this specialized form of care is not widely available, and its provision via HIPAA-compliant video links would offer a substantial increase in accessibility. Several small studies suggested that remote provision of family-based treatment is feasible and likely to be efficacious. The restrictions imposed by COVID-19 on face-to-face contact have accelerated the remote delivery of family-based treatment; hopefully, new research will document its effectiveness. It should be noted, however, that, in most cases, local contact with a medical professional who can directly measure weight and oversee the patient’s physical state is required.

The treatment of adults with anorexia nervosa, who typically developed the disorder as teenagers and have been ill for five or more years, remains challenging. Structured behavioral interventions, such as those available in specialized inpatient, day program, or residential centers, typically lead to significant weight restoration and psychological and physiological improvement. However, the rate of relapse following acute care remains substantial. Furthermore, most adult patients with anorexia nervosa are very reluctant to accept treatment in such structured programs. A recent helpful development is evidence that olanzapine, at a dose of 5 mg/day to 10 mg/day, assists modestly with weight gain in adult outpatients with anorexia nervosa and is associated with few significant side effects. Unfortunately, it does not address core psychological symptoms and must be viewed as adjunctive to standard care.

There have been fewer recent developments in the treatment of patients with bulimia nervosa and of BED. For bulimia nervosa, cognitive-behavioral therapy remains the mainstay psychological treatment, and SSRIs continue to be the first-choice class of medication. For BED, multiple forms of psychological treatment are associated with substantial improvement in binge eating, and, in 2015, the FDA approved the use of the stimulant lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) for individuals with BED. Unlike most psychological treatments, lisdexamfetamine is associated with modest weight loss but has effects on pulse and blood pressure that may be of concern, especially for older individuals.

Also noteworthy are the development and application of new forms of psychological treatment for individuals with eating disorders. These include dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), and integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT). Although only a few controlled studies have examined the effectiveness of these treatments, anecdotal information and the results of these studies suggest that such methods may be useful alternatives to more established interventions.

Conclusions

Eating disorders remain uncommon but clinically important problems characterized by persistent disturbances in eating or eating-related behavior. Cutting-edge research focuses on neurobiology and genetics, utilizing novel and rapidly evolving methodology. There have been modest advances in treatment approaches, including the COVID-19 pandemic’s acceleration of treatment delivery via video-link. Future studies will hopefully clarify the nature of ARFID and of atypical anorexia nervosa and lead to the development of more effective interventions, especially for individuals with long-standing eating disorders. ■

Additional Resources

Walsh BT. Diagnostic Categories for Eating Disorders: Current Status and What Lies Ahead. Psychiatr Clin North Am . 2019; 42(1):1-10.

Udo T, Grilo CM. Prevalence and Correlates of DSM-5 -Defined Eating Disorders in a Nationally Representative Sample of U.S. Adults. Biol Psychiatry . 2018; 84(5):345-354.

Van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Review of the Burden of Eating Disorders: Mortality, Disability, Costs, Quality of Life, and Family Burden. Curr Opin Psychiatry . 2020; 33(6):521-527.

Bernardoni F, Geisler D, King JA, et al. Altered Medial Frontal Feedback Learning Signals in Anorexia Nervosa. Biol Psychiatry . 2018; 83(3):235-243.

Frank GKW, Shott ME, DeGuzman MC. The Neurobiology of Eating Disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am . 2019; 28(4):629-640.

Steinglass JE, Berner LA, Attia E. Cognitive Neuroscience of Eating Disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am . 2019; 42(1):75-91.

Bulik CM, Blake L, Austin J. Genetics of Eating Disorders: What the Clinician Needs to Know. Psychiatr Clin North Am . 2019; 42(1):59-73.

Attia E, Steinglass JE, Walsh BT, et al. Olanzapine Versus Placebo in Adult Outpatients With Anorexia Nervosa: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Psychiatry . 2019; 176(6):449-456.

Le Grange D, Hughes EK, Court A, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of Parent-Focused Treatment and Family-Based Treatment for Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry . 2016; 55(8):683-92.

Pisetsky EM, Schaefer LM, Wonderlich SA, et al. Emerging Psychological Treatments in Eating Disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am . 2019; 42:219-229.

B. Timothy Walsh, M.D., is a professor of psychiatry at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center and the founding director of the Columbia Center for Eating Disorders at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. He is the co-editor of the Handbook of Assessment and Treatment of Eating Disorders from APA Publishing.

Dr. Walsh reports receiving royalties or honoraria from UpToDate, McGraw-Hill, the Oxford University Press, the British Medical Journal, the Johns Hopkins Press, and Guidepoint Global

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Mentalizing in psychotherapeutic processes of patients with eating disorders.

- 1 Department of Psychosomatic Medicine und Psychotherapy, Center for Mental Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Freiburg, Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany

- 2 Department of Consultation Psychiatry and Psychosomatics, University Hospital Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland

Background: Improvement in the capacity to mentalize (i.e., reflective functioning/RF) is considered both, an outcome variable as well as a possible change mechanism in psychotherapy. We explored variables related to (in-session) RF in patients with an eating disorder (ED) treated in a pilot study on a Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT) - oriented day hospital program. The research questions were secondary and focused on the psychotherapeutic process: What average RF does the group of patients show in sessions and does it change over the course of a single session? Are differences found between sections in which ED symptomatology is discussed and those in which it is not? Does RF increase after MBT-type interventions?

Methods: 1232 interaction segments from 77 therapy sessions of 19 patients with EDs were rated for RF by reliable raters using the In-Session RF Scale. Additionally, content (ED symptomatology yes/no) and certain MBT interventions were coded. Statistical analysis was performed by mixed models.

Results: Patients showed a rather low RF, which increased on average over the course of a session. If ED symptomatology was discussed, this was associated with significantly lower RF, while MBT-type interventions led to a significant increase in RF.

Conclusions: Results suggest that in-session mentalizing can be stimulated by MBT-typical interventions. RF seems to be more impaired when disorder-specific issues are addressed. Further studies have to show if improving a patient´s ability to mentalize their own symptoms is related to better outcomes.

1 Introduction

Mentalizing describes the ability to perceive and understand oneself and others (one’s own behavior/the behavior of others) in relation to inner states, feelings, intentions and desires ( 1 ). The capacity to mentalize is important for self-regulation (including the regulation of impulses and affect), as well as the regulation of relationships ( 1 ). Therefore, improved mentalizing (operationalized as Reflective Functioning/RF) is discussed both as an desirable outcome of psychotherapy as well as a change mechanism in psychotherapeutic processes ( 2 – 4 ). It was also suggested that a better ability to mentalize is associated with better therapeutic alliances and reduces the risk of treatment drop-out ( 5 , 6 ). This is an obvious consideration, as a patient who is able to reflect on the mental state of his/her therapist will find it easier not to experience a behavior or intervention as directed against him/herself. To improve mentalizing is the main focus in Mentalization Based Treatment (MBT), an approach originally developed for the treatment of borderline personality disorder – a disorder in which mentalizing is considerably impaired ( 7 , 8 ). More recently, MBT was adapted for the use in other mental disorders with impairment in mentalizing ( 9 ), including eating disorders ( 10 , 11 ).

RF can be described along different dimensions: It can be related to the self or another person, has a cognitive or affective focus, be implicit or explicit and related to something observable vs. internal mental states ( 4 ). Additionally, RF is not only a skill that people have more or less. Mentalizing in a given situation also depends on the context - for example, on the emotional relevance of a given session or the level of arousal induced in the relationship with another individual, including the therapist ( 7 ). For instance, high emotional arousal will lead to a fight or flight reaction instead of mentalizing. Therefore, the overall capacity to mentalize a person shows (e.g. in a structured interview like the Adult Attachment Interview), might differ from RF in a specific situation. Such a specific situation are psychotherapy sessions, in which RF is expected to be improved by therapeutic interventions. “In-session” RF (which can be measured with the In-Session-RF-Scale, see below) will depend on the relationship between the patient and the therapist, the topics discussed, the interventions of the therapist and several other factors that might influence the situation (e.g. events prior to the session: if a patient had a conflict with her partner) ( 12 ). Furthermore, RF might be impaired concerning the symptoms a patient has. “Symptom specific RF” was defined by Rudden et al. as the ability to reflect on the underlying meaning and affect- or relationship-related function of a symptom ( 13 ).

Overall, RF-related process research is in its infancy, although a better understanding of the factors that stimulate mentalizing in sessions and if and how mentalizing is related to productive psychotherapeutic processes is urgently needed. Previous research was able to find a relationship between interventions that are intended to increase RF and higher RF in the respective session (e.g. 14 – 16 ). Better RF in a session in turn predicted lower emotional arousal in patients with borderline personality disorder ( 14 ). Furthermore, an increase in in-session RF (positive deviation from the individual baseline-level) was shown to be related to less interpersonal problems and a reduction of depressive symptoms in patients with depression and anxiety treated with cognitive-behavior therapy ( 17 ).

Eating disorders (EDs) like anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN) primarily affect girls and women in the first half of their lives. AN and BN can easily become chronic with fluctuating courses, and are associated with serious mental and physical consequences ( 18 ). Treatment outcomes are not satisfactory, with remission rates barely reaching 50% in adults ( 19 ). AN, in particular, carries high mortality rates ( 20 ). At the core of psychopathology are difficulties in regulating negative affect ( 21 ), along with weight and shape concerns ( 22 ). These issues contribute to problematic eating behaviors (restrictive and/or binge eating) and inappropriate compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain. Maintaining factors include affect intolerance, unfavorable interpersonal interactions, consequences of malnutrition, and habit formation ( 23 ). Psychotherapeutic treatment is challenging because of a high ambivalence regarding change ( 24 ) and a strong wish for autonomy, while feeling needy and dependent on important others ( 25 ). In the majority of studies RF in individuals with ED was found to be impaired, including RF as shown in psychotherapy sessions ( 26 , 27 ). This is consistent with the fact that problems with the regulation of self-esteem, emotions and impulses on one hand and relationships on the other are at the core of ED psychopathology ( 18 ). Therefore, an adapted MBT-approach (MBT-ED) which focuses on an improvement in the capacity to mentalize might be helpful also in the treatment of individuals with an ED. However, there are only few pilot studies evaluating such an approach ( 11 , 28 , 29 ) and one randomized controlled study which included patients with an ED and features of a borderline-personality disorder ( 30 ). All of these studies have methodological limitations (observational studies, high drop-out rates) limiting the conclusions which can be drawn from them.

We developed a MBT manual for the treatment of eating disorders ( 11 , 31 ) and - as a first step - conducted an observational proof-of-concept study in a day hospital setting ( 11 ). Results were promising and showed that the program was well accepted by the patients (drop-out rate: 13.2%) and lead to significant reductions in eating pathology (EDE total score) and difficulties with emotion regulation as well as an improvement in RF ( 11 ), although overall outcome in ED symptomatology did not differ when compared to a historical matched control group.

The goal of this study, which followed an exploratory approach, is to support a better understanding of processes related to RF in psychotherapy sessions. To this end, we propose to answer the following questions that may inform future research: What is the average RF score of patients during individual MBT-ED sessions? Does RF change over the course of a single session? Are there differences in RF between parts of a therapy session in which eating disorder symptoms are discussed and those in which they are not? Are certain MBT-type interventions associated with increases in RF during the same during the same session sequence? Although the study - due to the few process studies in patients with eating disorders on this topic - was primarily exploratory in nature, we had some expectations based on previous findings. We expected a level of RF below the average values for health individuals. We further expected that MBT-type interventions will be associated with an increase in RF and that RF in average will increase over the course of a session (as we analyzed MBT-oriented sessions with corresponding objectives).

2.1 Study design – original study

The original “proof-of-concept”-study was prospective and observational. It was approved by the local ethics committee (No 448/17) and conducted in a day hospital, which provides an MBT-ED program for six patients with an ED at a time. All consecutively admitted patients with an ED over a period of 2 years were asked to take part in the study. In this time period, 38 out of 40 ED-patients admitted could be included. Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN) or other specified feeding and eating disorders (OSFED) according to DSM-5 (mental diagnoses were given after a SCID-5 interview), age ≥ 18, BMI ≥ 14.5 kg/m² and an indication for day hospital treatment ( 11 ). Exclusion criteria were psychoses, substance dependency, bipolar disorder, organic brain disease, dementia, severe somatic illness or acute suicidal ideation. The multimodal treatment program includes two MBT individual sessions per week (50 min, 25 min) and a one-weekly MBT-group therapy session besides further components [e.g. art and body therapy, work with an eating diary; for details see ( 11 )]. Therapists were trained in MBT and supervised by a certified MBT supervisor. Individual sessions were videotyped and assessed for MBT adherence which included feed back to the therapist after every 4th session. Main time points of assessment were admission, discharge and follow up assessments three and twelve months after discharge.

2.2 Process study

Every second patient was asked to take part in a process study (not every patient could be included due to the high effort involved). To study psychotherapeutic processes, we focused on individual treatment sessions. The second session and every forth of following sessions were included and transcribed according to the rules of Mergenthaler ( 32 ). Session transcripts were divided into 3-minute sequences. Thus, a therapy session of about 50 minutes yields 17 coded segments, with a time variable ranging from 3 to 51 by 3. Each sequence of the included sessions was rated for RF using the In-Session-Reflective Functioning-Scale ( 12 ). The scale ranges from -1 (refusing to use RF) and 0 (no RF) to values between 1 and 9 (1-4 low RF, 5 = normal RF, 6-9 high RF). The ratings were conducted by two trained and reliable raters (ICC = .81 ( 27 );). In addition to RF, the content of a sequence was coded. It was coded in terms of a focus on eating symptomatology (1 = yes/defined as sequences with a focus on ED symptoms vs. 0 = no/sequences without this focus) and if two types of MBT- interventions were used in the respective time segment: „demand”-interventions (prompting a patient to reflect on or explore a topic in more detail) and empathic validation (actively validating the emotional experience reported by a patient) (1 = yes/sequences with MBT intervention; 0 = no/sequences without MBT intervention).

We decided to exclude the last six minutes of each session from the analysis, because of typically very low RF (tested with mixed model: -0.64 RF compared to the other time segments; p < 0.0001), potentially changing the trajectory to non-linear. We considered the last minutes (talking out/saying goodbye, appointments, organizational issues) therefore as not representative of the psychotherapy process and the capacity of a patient to mentalize.

2.3 Psychometric measures

Eating psychopathology was measured with the Eating Disorder Examination Interview (EDE) interview ( 33 , 34 ) and the Eating Disorder Inventory self-report questionnaire (EDI-2) ( 35 , 36 ), general psychopathology with the Symptom-Check-List (SCL-90-R) ( 37 ), see also ( 11 ). In the original study, time points of measurement were admission, discharge as well as three and twelve month after discharge.

2.4 Statistical analysis

In order to account for the hierarchical structure of the data, we used mixed models to estimate linear trends of RF within sessions and it’s relations to session process. The analyses were computed with R (V4.2.2) and the package lme4 (V.1.1-32; Syntax see Table 1 ; REML estimation).

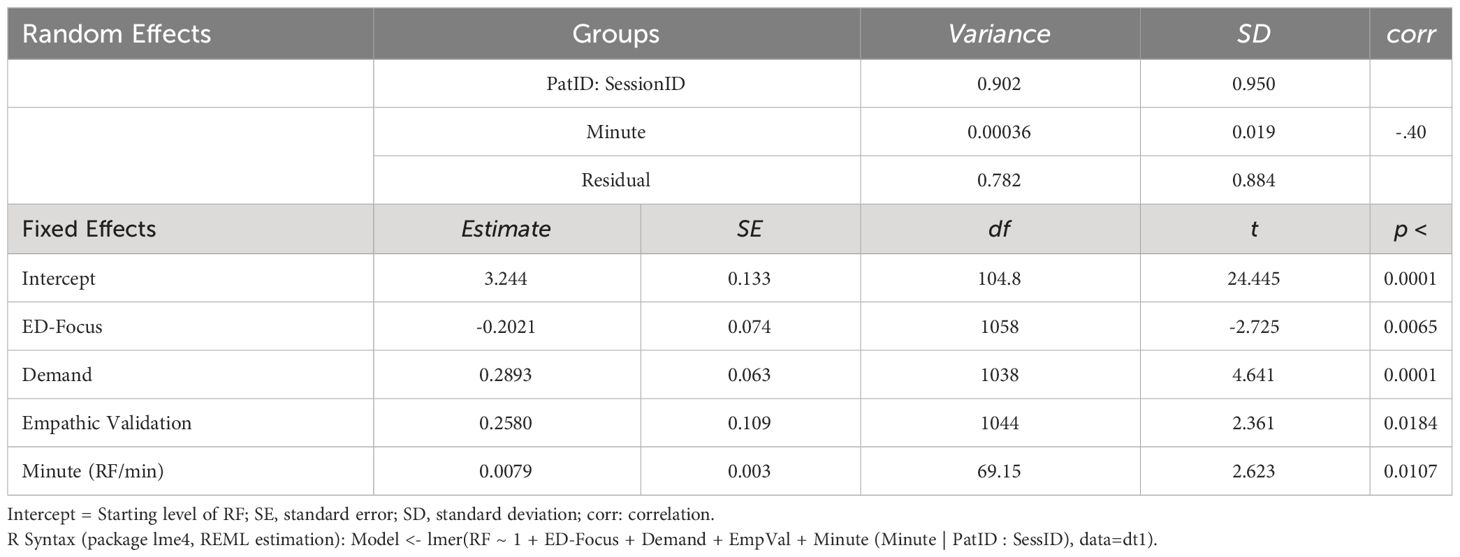

Table 1 Results of mixed model.

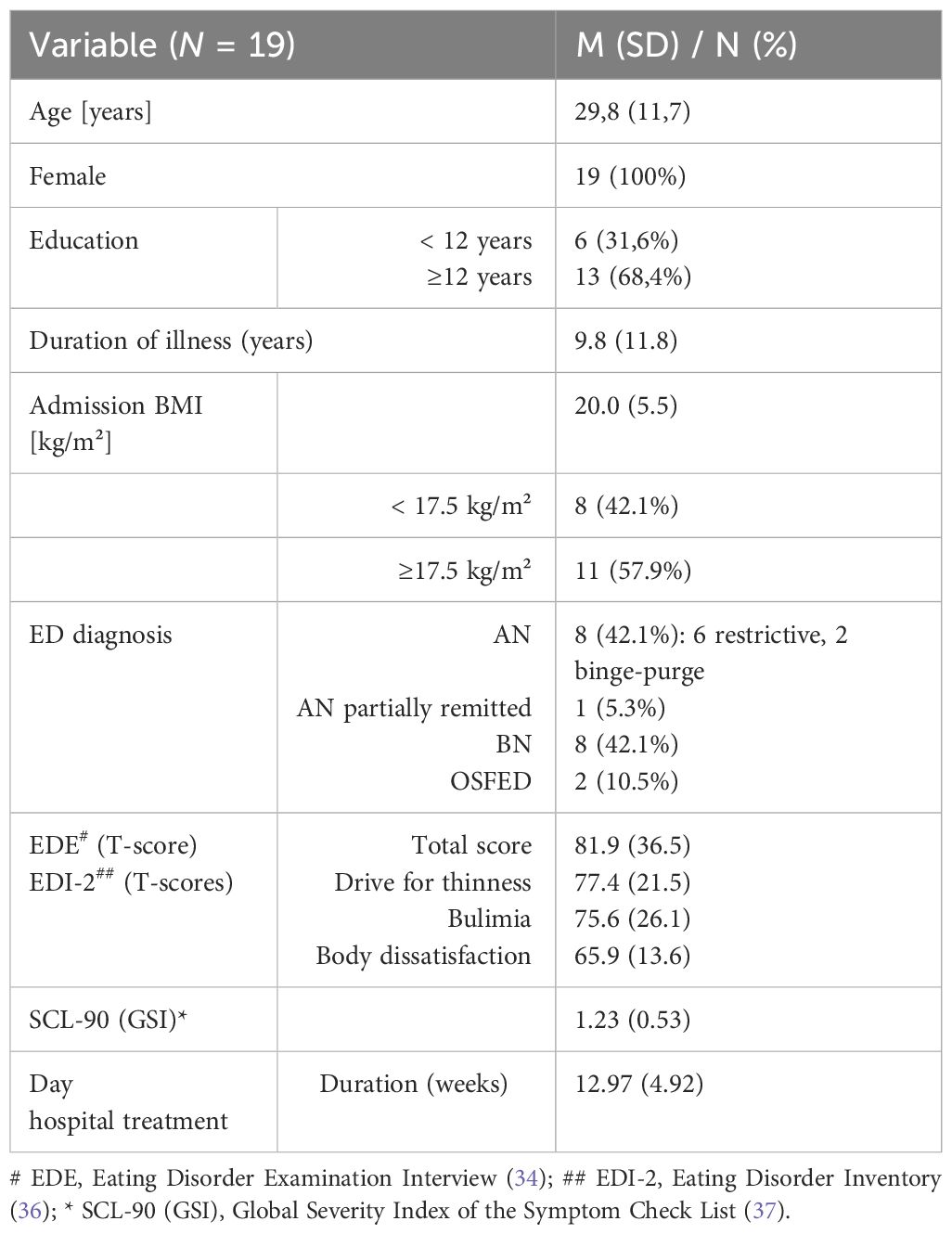

19 patients were included in the study. 77 sessions and 1232 session sequences were available for the analysis. For a sample description see Table 2 .

Table 2 Sample description.

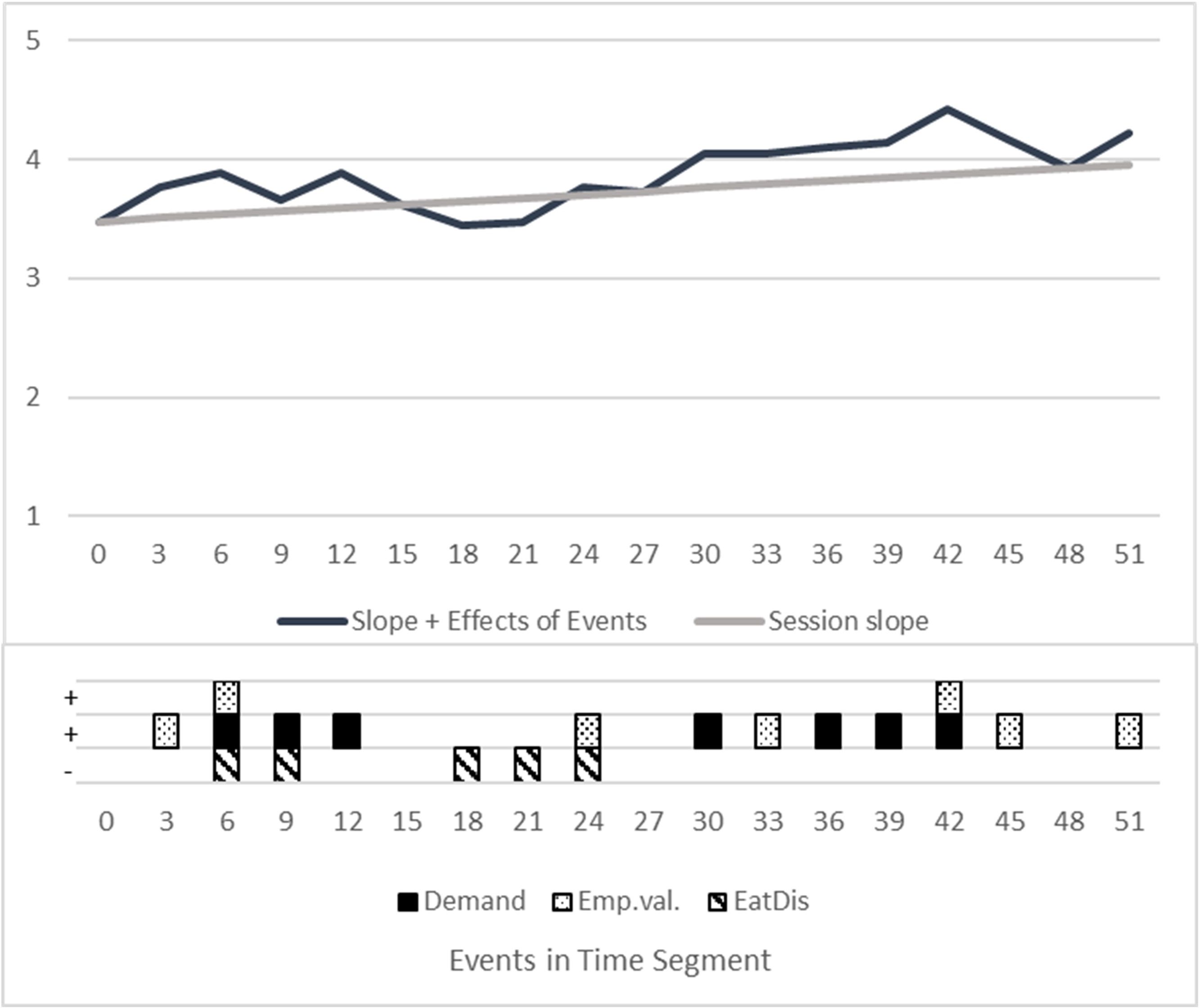

Overall, patients showed a low level of RF in sessions (M = 3.48). It did not differ between patients with a BMI below 18.5 kg/m² (M = 3.54; N = 9) and those with a BMI of 18.5-25 kg/m² (M = 3.47; N = 8). Two patients with a BMI > 25 kg/m² had a lower RF (M = 2.50; N = 2). On average, RF increased over the course of a session (Intercept = 3.24, slope = +0.0079/min = +0.48/50min), see Table 1 . Talking about eating-disorder related themes was associated with significantly lower RF (-0.20) within the respective, 3-minute long sequences of the sessions. Demand-interventions were positively associated with higher RF (+ 0.29) within the respective 3-minute sequence, this also applied to empathic validation (+ 0.26). Table 1 shows the formula and the estimates of the mixed model. For an illustration and better understanding, a constructed trajectory of a singe case is visualized in Figure 1 .

Figure 1 Visualization of a constructed therapy session. Constructed trajectory, showing the estimated impact of interventions on RF with a hypothetical pattern of interventions and ED focus. “Session slope”: RF Mean session trajectory with intercept = 3.48 RF and estimated increase of 0.48 RF (from minute 1 to minute 50). “Events”: Estimation of fixed effects directly in the segment of occurrence. Slope + Effects of Events: Mean course PLUS effects of all events / interventions. X-Axis/Time: Divided into the rated segments of 3 minutes. Squares with patterns: Constructed occurrences of interventions, coded yes=1, no = 0. Random Effects: Not shown, as this is a constructed single case. Random intercepts and slopes differ individually.

4 Discussion

The average RF shown in the sessions was low ( 38 , 39 ). This is consistent with preliminary findings in patients with EDs ( 10 , 26 ). It has to be taken into account that we assessed in-session RF, which depends on the process in each session and interventions used by the therapist. However, if we understand a psychotherapeutic session as a situation in which RF is usually challenged, average in-session RF will be an indicator for the overall capacity to mentalize ( 17 ). Talia et al. ( 12 ) found a moderate correlation between In-Session-RF and RF as assessed with the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI), probably due to the less standardized situation in therapy sessions (the AAI is a structured interview that uses so-called “demand” questions to stimulate RF). Nevertheless, patients with higher RF ratings in the AAI, showed also a better capacity to mentalize in psychotherapy sessions.

We found that RF increased over the course of a session. This might reflect a process of increasing reflection in this session, which would be intended in an MBT-oriented treatment ( 7 , 40 ). However, we cannot rule out that the finding is unspecific and for example due to the typical structure of a psychotherapy session: At the beginning the focus is on getting into contact and establishing a safe atmosphere, before more challenging topics are discussed. However, despite the general increase in RF, there could be fluctuations in RF that depend, for example, on the extent to which a patient feels perceived by their therapist and considers their interventions to be credible and trustworthy ( 41 , 42 ).

In terms of content, RF was lower in transcript sequences in which symptomatology was discussed. This could mean that mentalizing might „break in” when disorder-specific topics are addressed and be interpreted as a reduced capacity to reflect on the function and meaning of symptoms. It is an important question, if this correlation changes over the course of a successful treatment (that psychotherapy leads to an increase in RF in the context of eating-disorder related themes) and if such an improvement in symptom-related RF is finally related to outcome. This would need to be investigated in a larger prospective study in the future. As mentioned in the introduction, symptom-specific RF was previously shown to be relevant for change: A study on patients with panic disorder, the Cornell-Penn-Study, found that an increase in panic-specific RF in cognitive-behavioral as well as psychodynamic psychotherapy mediated a better treatment outcome ( 43 , 44 ).

Finally, we found that sequences with demand interventions or empathic validation showed increased mentalizing in the patient. Although we did not study the time sequence (if patients mentalized directly following these interventions), the finding suggest that both interventions might simulate RF. This would be a replication of previous findings, where could be shown that that MBT-type interventions in cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic treatments of AN were associated with an increase in in-session RF ( 15 ). Interestingly, both interventions are correlated with a similar increase in RF, although they differ in terms of their aim and might work through different mechanisms: While demand-interventions intend to directly stimulate RF, empathic validation is used to give the patient a feeling of being understood and intends to validate his experience emotionally. This is considered to be a necessary base for mentalizing, especially in situations, in which a patient is emotionally challenged ( 42 ).

The study has several limitations, which include the small sample size (which did not allow to analyze for influences of weight status) and the heterogeneous group of patients with an ED. An a priori power analysis was not conducted, power and sample size depended on the design of the primary study. Exploratory data analyses revealed no consistent pattern of non-linear trajectories. Therefore, we decided to model linear trajectories only. The sample consisted of women only. There is no baseline assessment of RF, e. g. with the Adult Attachment Interview and the RF-Rating-Scale, measuring by overall capacity of the patients to mentalize. Interventions like “demand” and “empathic validation” could be considered rather “unspecific” interventions without the context of the situation in which they are used and we did not assess a lot of other therapeutic interventions that might or might not contribute to RF.

In summary, we were able to show that RF in psychotherapy sessions with patients with an ED is not only context-dependent, but also depends on the content discussed. The ability to mentalize appears to be particularly impaired when disorder-specific topics (relating to food, body and weight) are addressed. Future studies should answer the question of whether a therapeutic focus on mentalizing eating disorder-specific experiences and beliefs during a session and an improvement in symptom-specific RF is a significant mediator of treatment success.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Freiburg, No 448/17. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IL: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. KE: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. LS: Resources, Writing – review & editing. SE: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CL: Writing – review & editing. AH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. We are thankful for receiving research grants to conduct the study: The work was supported by the Heidehofstiftung GmbH Stuttgart (Project No 59055.03.1/2.17; 59055.03.2/4.18; 59055.03.3/4.19). We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Freiburg.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Fonagy P, Gergely G, Jurist E, Target M. Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of the self . New York: Other Press (2002).

Google Scholar

2. Katznelson H. Reflective functioning: a review. Clin Psychol Rev . (2014) 34:107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.12.003

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Lüdemann J, Rabung S, Andreas S. Systematic review on mentalization as key factor in psychotherapy. Int J Environ Res Public Health . (2021) 18:9161. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179161

4. Luyten P, Campbell C, Allison E, Fonagy P. The mentalizing approach to psychopathology: state of the art and future directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol . (2020) 16:297–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-071919-015355

5. Ekeblad A, Falkenström F, Holmqvist R. Reflective functioning as predictor of working alliance and outcome in the treatment of depression. J Consult Clin Psychol . (2016) 84:67–78. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000055

6. Katznelson H, Falkenström F, Daniel SIF, Lunn S, Folke S, Pedersen SH, et al. Reflective functioning, psychotherapeutic alliance, and outcome in two psychotherapies for bulimia nervosa. Psychother (Chic) . (2020) 57:129–40. doi: 10.1037/pst0000245

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Bateman A, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment for personality disorders: A practical guide . Oxford: Oxford University Press (2016). doi: 10.1093/med:psych/9780199680375.001.0001

8. Levy KN, Meehan KB, Kelly KM, Reynoso JS, Weber M, Clarkin JF, et al. Change in attachment patterns and reflective function in a randomized control trial of transference-focused psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol . (2006) 74:1027–40. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1027

9. Bateman A, Fonagy P. Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice . 2nd edition. Washington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing (2019).

10. Robinson P, Skaderud F. “Eating disorders.,”. In: Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice . American Psychiatric Association Publishing, Washington (2019). p. 369–86.

11. Zeeck A, Endorf K, Euler S, Schaefer L, Lau I, Flösser K, et al. Implementation of mentalization-based treatment in a day hospital program for eating disorders-A pilot study. Eur Eat Disord Rev . (2021) 29:783–801. doi: 10.1002/erv.2853

12. Talia A, Miller-Bottome M, Katznelson H, Pedersen SH, Steele H, Schröder P, et al. Mentalizing in the presence of another: Measuring reflective functioning and attachment in the therapy process. Psychother Res . (2019) 29:652–65. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2017.1417651

13. Rudden M, Milrod B, Target M, Ackerman S, Graf E. Reflective functioning in panic disorder patients: a pilot study. J Am Psychoanal Assoc . (2006) 54:1339–43. doi: 10.1177/00030651060540040109

14. Kivity Y, Levy KN, Kelly KM, Clarkin JF. In-session reflective functioning in psychotherapies for borderline personality disorder: The emotion regulatory role of reflective functioning. J Consult Clin Psychol . (2021) 89:751–61. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000674

15. Meier AF, Zeeck A, Taubner S, Gablonski T, Lau I, Preiter R, et al. Mentalization-enhancing therapeutic interventions in the psychotherapy of anorexia nervosa: An analysis of use and influence on patients’ mentalizing capacity. Psychother Res . (2023) 33:595–607. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2022.2146542

16. Möller C, Karlgren L, Sandell A, Falkenström F, Philips B. Mentalization-based therapy adherence and competence stimulates in-session mentalization in psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder with co-morbid substance dependence. Psychother Res . (2017) 27:749–65. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2016.1158433

17. Babl A, Berger T, Decurtins H, Gross I, Frey T, Caspar F, et al. A longitudinal analysis of reflective functioning and its association with psychotherapy outcome in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders. J Couns Psychol . (2022) 69:337–47. doi: 10.1037/cou0000587

18. Treasure J, Duarte TA, Schmidt U. Eating disorders. Lancet . (2020) 395:899–911. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30059-3

19. Herpertz S, Fichter M, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Hilbert A, Tuschen-Caffier B, Vocks S, et al. S3-Leitinie Diagnostik und Behandlung der Essstörungen . Zweite Auflage. Berlin: Springer Verlag (2019). doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-59606-7

20. Arcelus J. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders: A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatr . (2011) 68:724. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74

21. Lavender JM, Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Gordon KH, Kaye WH, Mitchell JE. Dimensions of emotion dysregulation in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A conceptual review of the empirical literature. Clin Psychol Rev . (2015) 40:111–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.010

22. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther . (2003) 41:509–28. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00088-8

23. Treasure J, Willmott D, Ambwani S, Cardi V, Clark Bryan D, Rowlands K, et al. Cognitive interpersonal model for anorexia nervosa revisited: the perpetuating factors that contribute to the development of the severe and enduring illness. J Clin Med . (2020) 9(3):630. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030630

24. Zipfel S, Giel KE, Bulik CM, Hay P, Schmidt U. Anorexia nervosa: aetiology, assessment, and treatment. Lancet Psychiatry . (2015) 2:1099–111. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00356-9

25. Jewell T, Collyer H, Gardner T, Tchanturia K, Simic M, Fonagy P, et al. Attachment and mentalization and their association with child and adolescent eating pathology: A systematic review. Int J Eat Disord . (2016) 49:354–73. doi: 10.1002/eat.22473

26. Simonsen CB, Jakobsen AG, Grøntved S, Kjaersdam Telléus G. The mentalization profile in patients with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nord J Psychiatry . (2020) 74:311–22. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2019.1707869

27. Zeeck A, Taubner S, Gablonski TC, Lau I, Zipfel S, Herzog W, et al. In-session-reflective-functioning in anorexia nervosa: an analysis of psychotherapeutic sessions of the ANTOP study. Front Psychiatry . (2022) 13:814441. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.814441

28. Sonntag M, Russell J. The mind-in-mind study: A pilot randomised controlled trial that compared modified mentalisation based treatment with supportive clinical management for patients with eating disorders without borderline personality disorder. Eur Eat Disord Rev . (2022) 30:206–20. doi: 10.1002/erv.2888

29. Balestrieri M, Zuanon S, Pellizzari J, Zappoli-Thyrion E, Ciano R. ResT-MBT. Mentalization in eating disorders: a preliminary trial comparing mentalization-based treatment (MBT) with a psychodynamic-oriented treatment. Eat Weight Disord . (2015) 20:525–8. doi: 10.1007/s40519-015-0204-1

30. Robinson P, Hellier J, Barrett B, Barzdaitiene D, Bateman A, Bogaardt A, et al. The NOURISHED randomised controlled trial comparing mentalisation-based treatment for eating disorders (MBT-ED) with specialist supportive clinical management (SSCM-ED) for patients with eating disorders and symptoms of borderline personality disorder. BMCTrials . (2016) 17(1):549. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1606-8

31. Zeeck A, Floesser K, Euler S. Mentalisierungsbasierte therapie für essstörungen. Psychotherapeut . (2018) 63:129–34. doi: 10.1007/s00278-018-0273-5

32. Mergenthaler E. Die Transkription von Gespraechen- eine Zusammenstellung von Regeln mit einem Beispieltranskript . 4the edition. Ulm: Ulmer Textbank (2017).

33. Fairburn C, Cooper P. The eating disorder examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating. Nature, assessment, and treatment , 12th ed. Guilford Press, New York (1993). p. 317–60.

34. Hilbert A, Tuschen-Caffier B, Karwautz A, Niederhofer H, Munsch S. Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire: Evaluation der deutschsprachigen Übersetzung. Diagnostica . (2007) 53:144–54. doi: 10.1026/0012-1924.53.3.144

35. Garner D. Eating disorder inventory - 2. Professional manual . Odessa Florida, USA: Psychological Assessment Ressources (1991).

36. Meermann R, Napierski CH, Schulenkorf EM. EDI-muenster - selbstbeurteilungsfragebogen fuer essst”rungen. In: Therapie der Magersucht und Bulimia Nervosa. Ein klinischer Leitfaden fuer den Praktiker . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York (1987). doi: 10.1515/9783110859140

37. Franke G. Die symptom-check-liste von derogatis (SCL-90-R). Deutsche version - manual . Goettingen: Hogrefe (2002).

38. Fonagy P, Target M, Steele H, Steele M. Reflective-functioning manual, version 5.0, for application to adult attachment interviews . London: University College London (1998). doi: 10.1037/t03490-000

39. Karlsson R, Kermott A. Reflective-functioning during the process in brief psychotherapies. Psychother (Chic) . (2006) 43:65–84. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.1.65

40. Zeeck A, Euler S. Mentalisieren bei essstoerungen . Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta (2023).

41. Milesi A, De Carli P, Locati F, Campbell C, Fonagy P, Parolin L. How can I trust you? The role of facial trustworthiness in the development of Epistemic and Interpersonal Trust. Hum Dev . (2023) 67(2):57-68. doi: 10.1159/000530248

42. Fonagy P, Allison E. The role of mentalizing and epistemic trust in the therapeutic relationship. Psychother (Chic) . (2014) 51:372–80. doi: 10.1037/a0036505

43. Keefe JR, Huque ZM, DeRubeis RJ, Barber JP, Milrod BL, Chambless DL. In-session emotional expression predicts symptomatic and panic-specific reflective functioning improvements in panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy. Psychother (Chic) . (2019) 56:514–25. doi: 10.1037/pst0000215

44. Barber JP, Milrod B, Gallop R, Solomonov N, Rudden MG, McCarthy KS, et al. Processes of therapeutic change: Results from the Cornell-Penn Study of Psychotherapies for Panic Disorder. J Couns Psychol . (2020) 67:222–31. doi: 10.1037/cou0000417

Keywords: menatlization based treatment, intervention, in-session, eating disorder, psychotherapy

Citation: Zeeck A, Lau I, Endorf K, Schaefer L, Euler S, Lahmann C and Hartmann A (2024) Mentalizing in psychotherapeutic processes of patients with eating disorders. Front. Psychiatry 15:1367863. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1367863

Received: 09 January 2024; Accepted: 04 April 2024; Published: 19 April 2024.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2024 Zeeck, Lau, Endorf, Schaefer, Euler, Lahmann and Hartmann. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Almut Zeeck, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Eating disorders

Affiliations.

- 1 Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King's College London, London, UK. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King's College London, London, UK; Serviço de Psiquiatria e Saúde Mental, Hospital de Santa Maria, Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Norte, Lisbon, Portugal.

- 3 Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King's College London, London, UK; South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK.

- PMID: 32171414

- DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30059-3

Eating disorders are disabling, deadly, and costly mental disorders that considerably impair physical health and disrupt psychosocial functioning. Disturbed attitudes towards weight, body shape, and eating play a key role in the origin and maintenance of eating disorders. Eating disorders have been increasing over the past 50 years and changes in the food environment have been implicated. All health-care providers should routinely enquire about eating habits as a component of overall health assessment. Six main feeding and eating disorders are now recognised in diagnostic systems: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, avoidant-restrictive food intake disorder, pica, and rumination disorder. The presentation form of eating disorders might vary for men versus women, for example. As eating disorders are under-researched, there is a great deal of uncertainty as to their pathophysiology, treatment, and management. Future challenges, emerging treatments, and outstanding research questions are addressed.

Copyright © 2020 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Diagnosis, Differential

- Feeding and Eating Disorders* / diagnosis

- Feeding and Eating Disorders* / physiopathology

- Feeding and Eating Disorders* / psychology

- Feeding and Eating Disorders* / therapy

- Nutritional Status

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 17 March 2022

Binge eating disorder

- Katrin E. Giel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0938-4402 1 , 2 ,

- Cynthia M. Bulik ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7772-3264 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Fernando Fernandez-Aranda ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2968-9898 6 , 7 , 8 ,

- Phillipa Hay 9 , 10 ,

- Anna Keski-Rahkonen 11 ,

- Kathrin Schag 1 , 2 ,

- Ulrike Schmidt 12 , 13 &

- Stephan Zipfel 1 , 2

Nature Reviews Disease Primers volume 8 , Article number: 16 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

7475 Accesses

68 Citations

193 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Feeding behaviour

- Limbic system

- Psychiatric disorders

Binge eating disorder (BED) is characterized by regular binge eating episodes during which individuals ingest comparably large amounts of food and experience loss of control over their eating behaviour. The worldwide prevalence of BED for the years 2018–2020 is estimated to be 0.6–1.8% in adult women and 0.3–0.7% in adult men. BED is commonly associated with obesity and with somatic and mental health comorbidities. People with BED experience considerable burden and impairments in quality of life, and, at the same time, BED often goes undetected and untreated. The aetiology of BED is complex, including genetic and environmental factors as well as neuroendocrinological and neurobiological contributions. Neurobiological findings highlight impairments in reward processing, inhibitory control and emotion regulation in people with BED, and these neurobiological domains are targets for emerging treatment approaches. Psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for BED. Recognition and research on BED has increased since its inclusion into DSM-5; however, continuing efforts are needed to understand underlying mechanisms of BED and to improve prevention and treatment outcomes for this disorder. These efforts should also include screening, identification and implementation of evidence-based interventions in routine clinical practice settings such as primary care and mental health outpatient clinics.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 1 digital issues and online access to articles

92,52 € per year

only 92,52 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Sleep dysregulation in binge eating disorder and “food addiction”: the orexin (hypocretin) system as a potential neurobiological link

Genetics and neurobiology of eating disorders

What pharmacological interventions are effective in binge-eating disorder? Insights from a critical evaluation of the evidence from clinical trials

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 350–353 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

World Health Organization. ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision. ICD https://icd.who.int/ (2019).

Treasure, J. et al. Anorexia nervosa. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 1 , 15074 (2015).

PubMed Google Scholar

Zipfel, S., Giel, K. E., Bulik, C. M., Hay, P. & Schmidt, U. Anorexia nervosa: aetiology, assessment, and treatment. Lancet Psychiatry 2 , 1099–1111 (2015).

Keski-Rahkonen, A. & Mustelin, L. Epidemiology of eating disorders in Europe: prevalence, incidence, comorbidity, course, consequences, and risk factors. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 29 , 340–345 (2016).

Hoek, H. W. Review of the worldwide epidemiology of eating disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 29 , 336–339 (2016).

Udo, T. & Grilo, C. M. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5-defined eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. Biol. Psychiatry 84 , 345–354 (2018).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Agh, T. et al. Epidemiology, health-related quality of life and economic burden of binge eating disorder: a systematic literature review. Eat. Weight. Disord. 20 , 1–12 (2015). This systematic review highlights what is known about quality of life and burden of people affected by BED .

Dawes, A. J. et al. Mental health conditions among patients seeking and undergoing bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis. JAMA 315 , 150–163 (2016).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet 387 , 1377–1396 (2016).

Google Scholar

World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 894 (WHO, 2000).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Eating disorders: recognition and treatment (full guideline). NICE https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng69/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-161214767896 (2017).

Herpertz, S. et al. S3-Leitlinie Diagnostik und Behandlung der Essstörungen. AWMF https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/051-026l_S3_Essstoerung-Diagnostik-Therapie_2020-03.pdf (2018).

Gonzalez-Muniesa, P. et al. Obesity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 3 , 17034 (2017).

Santomauro, D. F. et al. The hidden burden of eating disorders: an extension of estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 8 , 320–328 (2021). This paper, based on studies from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) dataset provides up-to-date evidence on epidemiology and burden caused by eating disorders including BED, providing so far unrepresented GBD data .

Stice, E., Marti, C. N. & Rohde, P. Prevalence, incidence, impairment, and course of the proposed DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses in an 8-year prospective community study of young women. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 122 , 445–457 (2013).

Kessler, R. C. et al. The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol. Psychiatry 73 , 904–914 (2013).

Keski-Rahkonen, A. Epidemiology of binge eating disorder: prevalence, course, comorbidity, and risk factors. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 34 , 525–531 (2021).

Mitchison, D. et al. DSM-5 full syndrome, other specified, and unspecified eating disorders in Australian adolescents: prevalence and clinical significance. Psychol. Med. 50 , 981–990 (2020).

Olsen, E. M., Koch, S. V., Skovgaard, A. M. & Strandberg-Larsen, K. Self-reported symptoms of binge-eating disorder among adolescents in a community-based Danish cohort–a study of prevalence, correlates, and impact. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 54 , 492–505 (2021).

Glazer, K. B. et al. The course of eating disorders involving bingeing and purging among adolescent girls: prevalence, stability, and transitions. J. Adolesc. Health 64 , 165–171 (2019).

Meule, A. The psychology of overeating: food and the culture of consumerism. Food Cult. Soc. 19 , 735–736 (2016).

Streatfeild, J. et al. Social and economic cost of eating disorders in the United States: evidence to inform policy action. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 54 , 851–868 (2021).

Silén, Y. et al. Detection, treatment, and course of eating disorders in Finland: a population-based study of adolescent and young adult females and males. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 29 , 720–732 (2021).

Coffino, J. A., Udo, T. & Grilo, C. M. Rates of help-seeking in US adults with lifetime DSM-5 eating disorders: prevalence across diagnoses and differences by sex and ethnicity/race. Mayo Clin. Proc. 94 , 1415–1426 (2019).

Abbott, S., Dindol, N., Tahrani, A. A. & Piya, M. K. Binge eating disorder and night eating syndrome in adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. J. Eat. Disord. 6 , 36 (2018).

Brownley, K. A. et al. Binge-eating disorder in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 165 , 409–420 (2016).

Wassenaar, E., Friedman, J. & Mehler, P. S. Medical complications of binge eating disorder. Psychiatr. Clin. North. Am. 42 , 275–286 (2019).

Harris, S. R., Carrillo, M. & Fujioka, K. Binge-eating disorder and type 2 diabetes: a review. Endocr. Pract. 27 , 158–164 (2021).

Tate, A. E. et al. Association and familial coaggregation of type 1 diabetes and eating disorders: a register-based cohort study in Denmark and Sweden. Diabetes Care 44 , 1143–1150 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Pilot study of the prevalence of binge eating disorder in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Ann. Gastroenterol. 30 , 664–669 (2017).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Forlano, R. et al. Binge-eating disorder is associated with an unfavorable body mass composition in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 54 , 2025–2030 (2021).

Cremonini, F. et al. Associations among binge eating behavior patterns and gastrointestinal symptoms: a population-based study. Int. J. Obes. 33 , 342–353 (2009).

CAS Google Scholar

Thornton, L. M. et al. Binge-eating disorder in the Swedish national registers: somatic comorbidity. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 50 , 58–65 (2017).

Kimmel, M. C., Ferguson, E. H., Zerwas, S., Bulik, C. M. & Meltzer-Brody, S. Obstetric and gynecologic problems associated with eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 49 , 260–275 (2016).

Udo, T. & Grilo, C. M. Psychiatric and medical correlates of DSM-5 eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of adults in the United States. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 52 , 42–50 (2019). This paper provides a recent and comprehensive description of common co-occurring conditions with eating disorders based on a representative population sample .

Udo, T., Bitley, S. & Grilo, C. M. Suicide attempts in US adults with lifetime DSM-5 eating disorders. BMC Med. 17 , 120–123 (2019).

Fernandez-Aranda, F. et al. Impulse control disorders in women with eating disorders. Psychiatry Res. 157 , 147–157 (2008).

Jimenez-Murcia, S. et al. Pathological gambling in eating disorders: prevalence and clinical implications. Compr. Psychiatry 54 , 1053–1060 (2013).

Nazar, B. P. et al. The risk of eating disorders comorbid with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 49 , 1045–1057 (2016).

Schmidt, F., Körber, S., de Zwaan, M. & Müller, A. Impulse control disorders in obese patients. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 20 , e144–e147 (2012).

Lydecker, J. A. & Grilo, C. M. Psychiatric comorbidity as predictor and moderator of binge-eating disorder treatment outcomes: an analysis of aggregated randomized controlled trials. Psychol. Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721001045 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

West, C. E., Goldschmidt, A. B., Mason, S. M. & Neumark-Sztainer, D. Differences in risk factors for binge eating by socioeconomic status in a community-based sample of adolescents: findings from Project EAT. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 52 , 659–668 (2019).

Braun, J. et al. Trauma exposure, DSM-5 posttraumatic stress, and binge eating symptoms: results from a nationally representative sample. J. Clin. Psychiatry 80 , 19m12813 (2019).

Coffino, J. A., Udo, T. & Grilo, C. M. The significance of overvaluation of shape or weight in binge-eating disorder: results from a national sample of U.S. adults. Obesity 27 , 1367–1371 (2019).

& Borg, S. L. et al. Relationships between childhood abuse and eating pathology among individuals with binge-eating disorder: examining the moderating roles of self-discrepancy and self-directed style. Eat. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2020.1864588 (2021).

Hazzard, V. M., Bauer, K. W., Mukherjee, B., Miller, A. L. & Sonneville, K. R. Associations between childhood maltreatment latent classes and eating disorder symptoms in a nationally representative sample of young adults in the United States. Child. Abus. Negl. 98 , 104171 (2019).

Hazzard, V. M., Loth, K. A., Hooper, L. & Becker, C. B. Food insecurity and eating disorders: a review of emerging evidence. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 22 , 74–70 (2020).

& Hazzard, V. M. et al. Past-year abuse and eating disorder symptoms among U.S. college students. J. Interpers. Violence https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211005156 (2021).

Masheb, R. M. et al. DSM-5 eating disorder prevalence, gender differences, and mental health associations in United States military veterans. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 54 , 1171–1180 (2021).

de Beaurepaire, R. Binge eating disorders in antipsychotic-treated patients with schizophrenia: prevalence, antipsychotic specificities, and changes over time. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 41 , 114–120 (2021).

Goode, R. W. et al. Binge eating and binge-eating disorder in Black women: a systematic review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 53 , 491–507 (2020).

Marques, L. et al. Comparative prevalence, correlates of impairment, and service utilization for eating disorders across US ethnic groups: implications for reducing ethnic disparities in health care access for eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 44 , 412–420 (2011).

Perez, M., Ohrt, T. K. & Hoek, H. W. Prevalence and treatment of eating disorders among Hispanics/Latino Americans in the United States. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 29 , 378–382 (2016).

Kamody, R. C., Grilo, C. M. & Udo, T. Disparities in DSM-5 defined eating disorders by sexual orientation among US adults. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 53 , 278–287 (2020).

Nagata, J. M., Ganson, K. T. & Austin, S. B. Emerging trends in eating disorders among sexual and gender minorities. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 33 , 562–567 (2020).

Beccia, A. L., Baek, J., Austin, S. B., Jesdale, W. M. & Lapane, K. L. Eating-related pathology at the intersection of gender, gender expression, sexual orientation, and weight status: an intersectional Multilevel Analysis of Individual Heterogeneity and Discriminatory Accuracy (MAIHDA) of the Growing Up Today Study cohorts. Soc. Sci. Med. 281 , 114092 (2021).

Cheah, S. L., Jackson, E., Touyz, S. & Hay, P. Prevalence of eating disorder is lower in migrants than in the Australian-born population. Eat. Behav. 37 , 101370 (2020).

Burt, A., Mitchison, D., Doyle, K. & Hay, P. Eating disorders amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: a scoping review. J. Eat. Disord. 8 , 73 (2020).

Puhl, R. & Suh, Y. Health consequences of weight stigma: implications for obesity prevention and treatment. Curr. Obes. Rep. 4 , 182–190 (2015).

Donnelly, B. et al. Neuroimaging in bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: a systematic review. J. Eat. Disord. 6 , 3 (2018).

Strubbe, J. H. & Woods, S. C. The timing of meals. Psychol. Rev. 111 , 128–141 (2004).

Berthoud, H. R. & Morrison, C. The brain, appetite, and obesity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 59 , 55–92 (2008).

Rosenbaum, M. & Leibel, R. L. 20 years of leptin: role of leptin in energy homeostasis in humans. J. Endocrinol. 223 , T83–T96 (2014).

Muller, T. D. et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Mol. Metab. 30 , 72–130 (2019).

Yu, Y., Fernandez, I. D., Meng, Y., Zhao, W. & Groth, S. W. Gut hormones, adipokines, and pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines/markers in loss of control eating: a scoping review. Appetite 166 , 105442 (2021).

Hernandez, D., Mehta, N. & Geliebter, A. Meal-related acyl and des-acyl ghrelin and other appetite-related hormones in people with obesity and binge eating. Obesity 27 , 629–635 (2019).

Munsch, S., Biedert, E., Meyer, A. H., Herpertz, S. & Beglinger, C. CCK, ghrelin, and PYY responses in individuals with binge eating disorder before and after a cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT). Physiol. Behav. 97 , 14–20 (2009).

Voon, V. Cognitive biases in binge eating disorder: the hijacking of decision making. CNS Spectr. 20 , 566–573 (2015).

Avena, N. M., Bocarsly, M. E., Hoebel, B. G. & Gold, M. S. Overlaps in the nosology of substance abuse and overeating: the translational implications of “food addiction”. Curr. Drug Abus. Rev. 4 , 133–139 (2011).

& Steward, T. et al. What difference does it make? Risk-taking behavior in obesity after a loss is associated with decreased ventromedial prefrontal cortex activity. J. Clin. Med. 8 , 1551 (2019).

PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hege, M. A. et al. Attentional impulsivity in binge eating disorder modulates response inhibition performance and frontal brain networks. Int. J. Obes. 39 , 353–360 (2015).

Wolz, I. et al. Subjective craving and event-related brain response to olfactory and visual chocolate cues in binge-eating and healthy individuals. Sci. Rep. 7 , 41736 (2017).

Balodis, I. M. et al. Divergent neural substrates of inhibitory control in binge eating disorder relative to other manifestations of obesity. Obesity 21 , 367–377 (2013).

Frank, G. K. W., Shott, M. E., Stoddard, J., Swindle, S. & Pryor, T. L. Association of brain reward response with body mass index and ventral striatal-hypothalamic circuitry among young women with eating disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 78 , 1123–1133 (2021).

Leehr, E. J. et al. Emotion regulation model in binge eating disorder and obesity–a systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 49 , 125–134 (2015).

Ansell, E. B., Grilo, C. M. & White, M. A. Examining the interpersonal model of binge eating and loss of control over eating in women. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 45 , 43–50 (2012).

Iceta, S. et al. Cognitive function in binge eating disorder and food addiction: a systematic review and three-level meta-analysis. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 111 , 110400 (2021).

Giel, K. E., Teufel, M., Junne, F., Zipfel, S. & Schag, K. Food-related impulsivity in obesity and binge eating disorder–a systematic update of the evidence. Nutrients 9 , 1170 (2017).

Kessler, R. M., Hutson, P. H., Herman, B. K. & Potenza, M. N. The neurobiological basis of binge-eating disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 63 , 223–238 (2016). This review provides a comprehensive synthesis of the neurobiological findings in BED and develops hyopotheses for neurobiological pathomechanisms in the development and maintenance of BED .

Schag, K., Schonleber, J., Teufel, M., Zipfel, S. & Giel, K. E. Food-related impulsivity in obesity and binge eating disorder–a systematic review. Obes. Rev. 14 , 477–495 (2013).

Mallorqui-Bague, N. et al. Impulsivity and cognitive distortions in different clinical phenotypes of gambling disorder: profiles and longitudinal prediction of treatment outcomes. Eur. Psychiatry 61 , 9–16 (2019).

& Lozano-Madrid, et al.Impulsivity, emotional dysregulation and executive function deficits could be associated with alcohol and drug abuse in eating disorders. J. Clin. Med. 9 , 1936 (2020).

CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Grant, J. E. & Chamberlain, S. R. Neurocognitive findings in young adults with binge eating disorder. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 24 , 71–76 (2020).

Oliva, R., Morys, F., Horstmann, A., Castiello, U. & Begliomini, C. Characterizing impulsivity and resting-state functional connectivity in normal-weight binge eaters. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 53 , 478–488 (2020).

Lucas, I. et al. Neuropsychological learning deficits as predictors of treatment outcome in patients with eating disorders. Nutrients 13 , 2145 (2021).

Schag, K. et al. Food-related impulsivity assessed by longitudinal laboratory tasks is reduced in patients with binge eating disorder in a randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 11 , 8225 (2021).

Dingemans, A. E., van Son, G. E., Vanhaelen, C. B. & van Furth, E. F. Depressive symptoms rather than executive functioning predict group cognitive behavioural therapy outcome in binge eating disorder. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 28 , 620–632 (2020).

Mestre-Bach, G., Fernandez-Aranda, F., Jimenez-Murcia, S. & Potenza, M. N. Decision-making in gambling disorder, problematic pornography use, and binge-eating disorder: similarities and differences. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 7 , 97–108 (2020).

Amlung, M. et al. Delay discounting as a transdiagnostic process in psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 76 , 1176–1186 (2019).

Appelhans, B. M. et al. Inhibiting food reward: delay discounting, food reward sensitivity, and palatable food intake in overweight and obese women. Obesity 19 , 2175–2182 (2011).

Tang, J., Chrzanowski-Smith, O. J., Hutchinson, G., Kee, F. & Hunter, R. F. Relationship between monetary delay discounting and obesity: a systematic review and meta-regression. Int. J. Obes. 43 , 1135–1146 (2019).

Steward, T. et al. Delay discounting of reward and impulsivity in eating disorders: from anorexia nervosa to binge eating disorder. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 25 , 601–606 (2017).

Steward, T. et al. Delay discounting and impulsivity traits in young and older gambling disorder patients. Addict. Behav. 71 , 96–103 (2017).

Miranda-Olivos, R. et al. The neural correlates of delay discounting in obesity and binge eating disorder. J. Behav. Addict. 10 , 498–507 (2021).

Fowler, S. & Bulik, C. Family environment and psychiatric history in women with binge eating disorder and obese controls. Behav. Change 14 , 106–112 (1997).

Hudson, J. et al. Familial aggregation of binge-eating disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 63 , 313–319 (2006).

Javaras, K. N. et al. Familiality and heritability of binge eating disorder: results of a case-control family study and a twin study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 41 , 174–179 (2008).

Mitchell, K. S. et al. Binge eating disorder: a symptom-level investigation of genetic and environmental influences on liability. Psychol. Med. 40 , 1899–1906 (2010).