Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

1. americans’ views on whether, and in what circumstances, abortion should be legal.

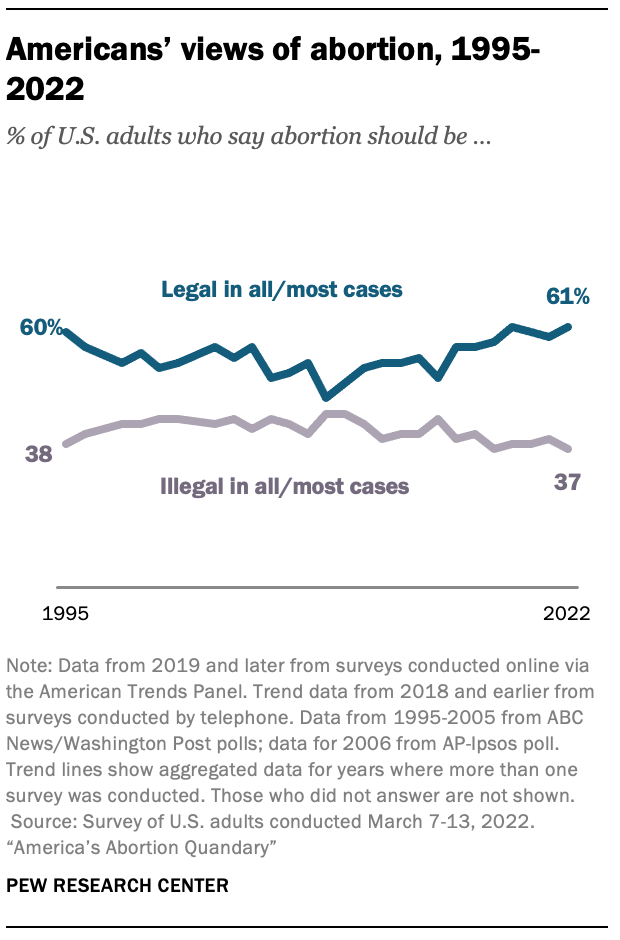

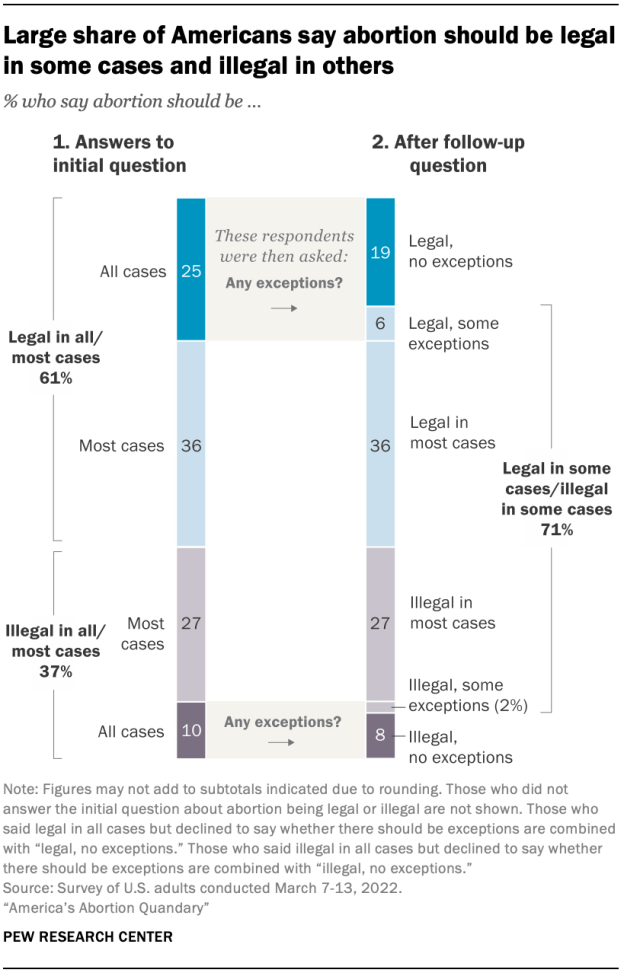

As the long-running debate over abortion reaches another key moment at the Supreme Court and in state legislatures across the country , a majority of U.S. adults continue to say that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. About six-in-ten Americans (61%) say abortion should be legal in “all” or “most” cases, while 37% think abortion should be illegal in all or most cases. These views have changed little over the past several years: In 2019, for example, 61% of adults said abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while 38% said it should be illegal in all or most cases. Most respondents in the new survey took one of the middle options when first asked about their views on abortion, saying either that abortion should be legal in most cases (36%) or illegal in most cases (27%).

Respondents who said abortion should either be legal in all cases or illegal in all cases received a follow-up question asking whether there should be any exceptions to such laws. Overall, 25% of adults initially said abortion should be legal in all cases, but about a quarter of this group (6% of all U.S. adults) went on to say that there should be some exceptions when abortion should be against the law.

One-in-ten adults initially answered that abortion should be illegal in all cases, but about one-in-five of these respondents (2% of all U.S. adults) followed up by saying that there are some exceptions when abortion should be permitted.

Altogether, seven-in-ten Americans say abortion should be legal in some cases and illegal in others, including 42% who say abortion should be generally legal, but with some exceptions, and 29% who say it should be generally illegal, except in certain cases. Much smaller shares take absolutist views when it comes to the legality of abortion in the U.S., maintaining that abortion should be legal in all cases with no exceptions (19%) or illegal in all circumstances (8%).

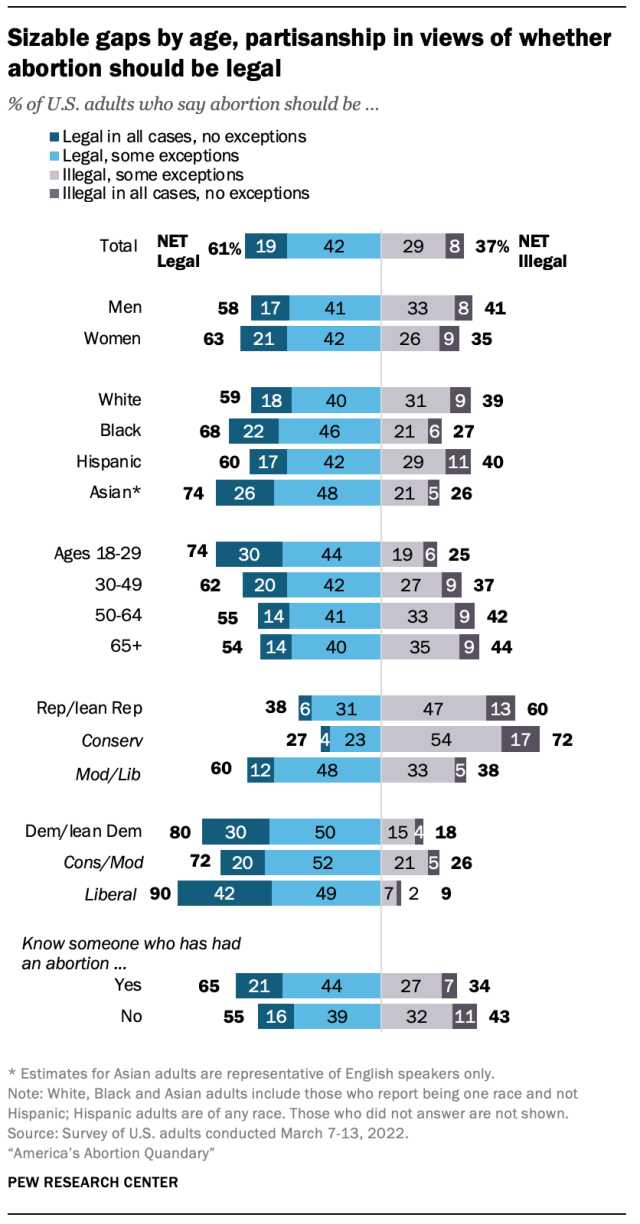

There is a modest gender gap in views of whether abortion should be legal, with women slightly more likely than men to say abortion should be legal in all cases or in all cases but with some exceptions (63% vs. 58%).

Younger adults are considerably more likely than older adults to say abortion should be legal: Three-quarters of adults under 30 (74%) say abortion should be generally legal, including 30% who say it should be legal in all cases without exception.

But there is an even larger gap in views toward abortion by partisanship: 80% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, compared with 38% of Republicans and GOP leaners. Previous Center research has shown this gap widening over the past 15 years.

Still, while partisans diverge in views of whether abortion should mostly be legal or illegal, most Democrats and Republicans do not view abortion in absolutist terms. Just 13% of Republicans say abortion should be against the law in all cases without exception; 47% say it should be illegal with some exceptions. And while three-in-ten Democrats say abortion should be permitted in all circumstances, half say it should mostly be legal – but with some exceptions.

There also are sizable divisions within both partisan coalitions by ideology. For instance, while a majority of moderate and liberal Republicans say abortion should mostly be legal (60%), just 27% of conservative Republicans say the same. Among Democrats, self-described liberals are twice as apt as moderates and conservatives to say abortion should be legal in all cases without exception (42% vs. 20%).

Regardless of partisan affiliation, adults who say they personally know someone who has had an abortion – such as a friend, relative or themselves – are more likely to say abortion should be legal than those who say they do not know anyone who had an abortion.

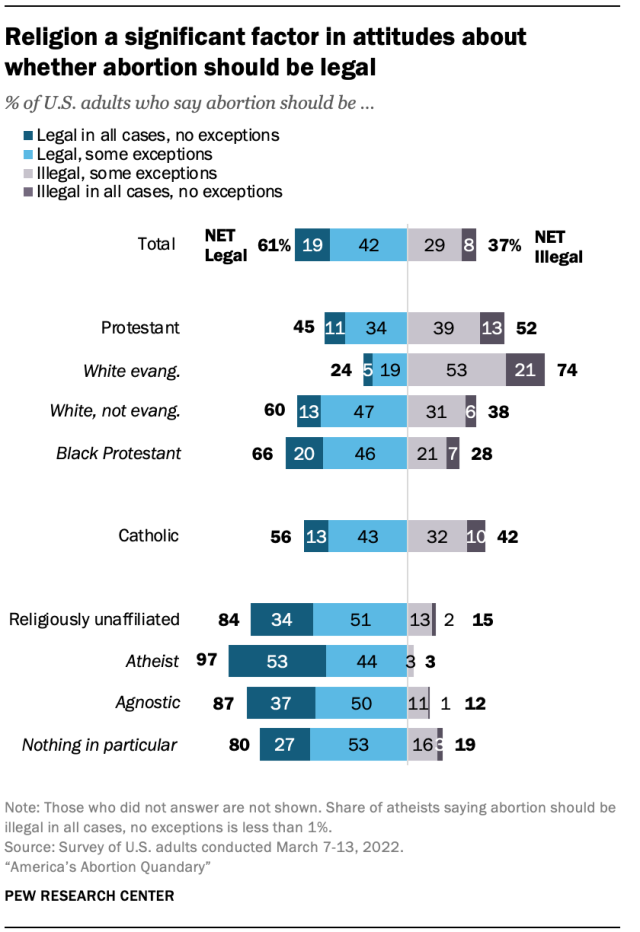

Views toward abortion also vary considerably by religious affiliation – specifically among large Christian subgroups and religiously unaffiliated Americans.

For example, roughly three-quarters of White evangelical Protestants say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases. This is far higher than the share of White non-evangelical Protestants (38%) or Black Protestants (28%) who say the same.

Despite Catholic teaching on abortion , a slim majority of U.S. Catholics (56%) say abortion should be legal. This includes 13% who say it should be legal in all cases without exception, and 43% who say it should be legal, but with some exceptions.

Compared with Christians, religiously unaffiliated adults are far more likely to say abortion should be legal overall – and significantly more inclined to say it should be legal in all cases without exception. Within this group, atheists stand out: 97% say abortion should be legal, including 53% who say it should be legal in all cases without exception. Agnostics and those who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” also overwhelmingly say that abortion should be legal, but they are more likely than atheists to say there are some circumstances when abortion should be against the law.

Although the survey was conducted among Americans of many religious backgrounds, including Jews, Muslims, Buddhists and Hindus, it did not obtain enough respondents from non-Christian groups to report separately on their responses.

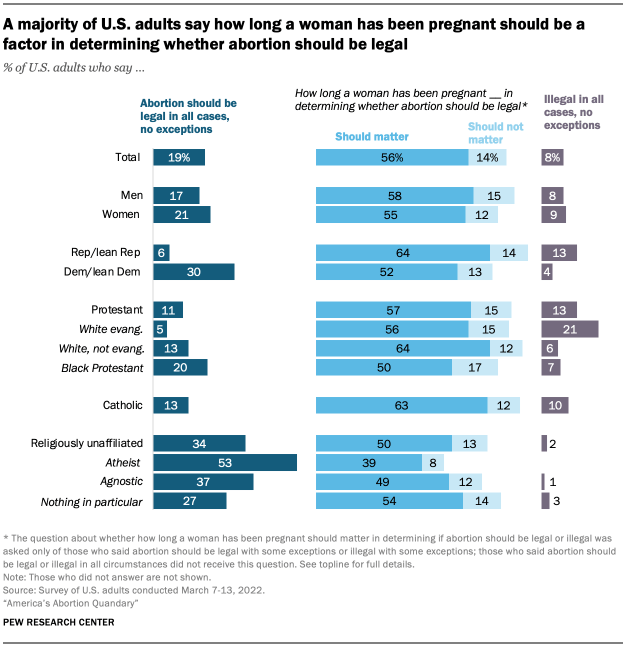

Abortion at various stages of pregnancy

As a growing number of states debate legislation to restrict abortion – often after a certain stage of pregnancy – Americans express complex views about when abortion should generally be legal and when it should be against the law. Overall, a majority of adults (56%) say that how long a woman has been pregnant should matter in determining when abortion should be legal, while far fewer (14%) say that this should not be a factor. An additional one-quarter of the public says that abortion should either be legal (19%) or illegal (8%) in all circumstances without exception; these respondents did not receive this question.

Among men and women, Republicans and Democrats, and Christians and religious “nones” who do not take absolutist positions about abortion on either side of the debate, the prevailing view is that the stage of the pregnancy should be a factor in determining whether abortion should be legal.

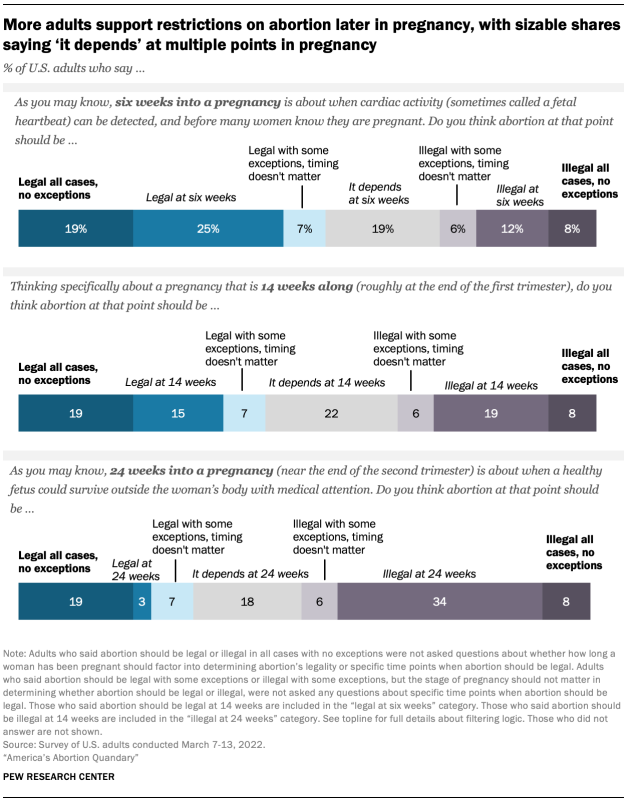

Americans broadly are more likely to favor restrictions on abortion later in pregnancy than earlier in pregnancy. Many adults also say the legality of abortion depends on other factors at every stage of pregnancy.

One-in-five Americans (21%) say abortion should be illegal at six weeks. This includes 8% of adults who say abortion should be illegal in all cases without exception as well as 12% of adults who say that abortion should be illegal at this point. Additionally, 6% say abortion should be illegal in most cases and how long a woman has been pregnant should not matter in determining abortion’s legality. Nearly one-in-five respondents, when asked whether abortion should be legal six weeks into a pregnancy, say “it depends.”

Americans are more divided about what should be permitted 14 weeks into a pregnancy – roughly at the end of the first trimester – although still, more people say abortion should be legal at this stage (34%) than illegal (27%), and about one-in-five say “it depends.”

Fewer adults say abortion should be legal 24 weeks into a pregnancy – about when a healthy fetus could survive outside the womb with medical care. At this stage, 22% of adults say abortion should be legal, while nearly twice as many (43%) say it should be illegal . Again, about one-in-five adults (18%) say whether abortion should be legal at 24 weeks depends on other factors.

Respondents who said that abortion should be illegal 24 weeks into a pregnancy or that “it depends” were asked a follow-up question about whether abortion at that point should be legal if the pregnant woman’s life is in danger or the baby would be born with severe disabilities. Most who received this question say abortion in these circumstances should be legal (54%) or that it depends on other factors (40%). Just 4% of this group maintained that abortion should be illegal in this case.

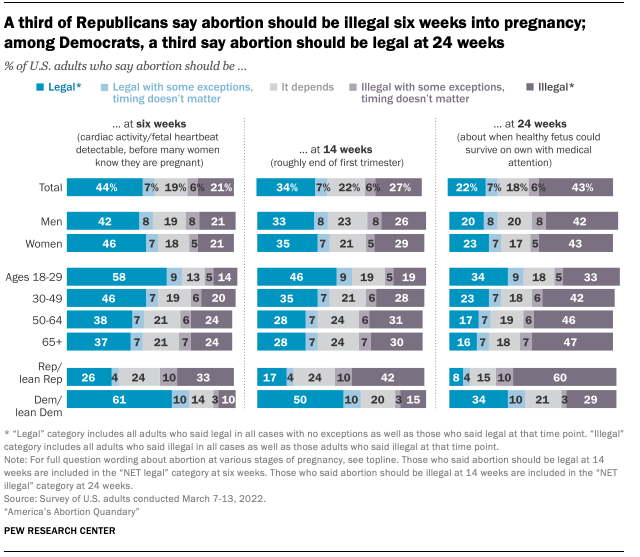

This pattern in views of abortion – whereby more favor greater restrictions on abortion as a pregnancy progresses – is evident across a variety of demographic and political groups.

Democrats are far more likely than Republicans to say that abortion should be legal at each of the three stages of pregnancy asked about on the survey. For example, while 26% of Republicans say abortion should be legal at six weeks of pregnancy, more than twice as many Democrats say the same (61%). Similarly, while about a third of Democrats say abortion should be legal at 24 weeks of pregnancy, just 8% of Republicans say the same.

However, neither Republicans nor Democrats uniformly express absolutist views about abortion throughout a pregnancy. Republicans are divided on abortion at six weeks: Roughly a quarter say it should be legal (26%), while a similar share say it depends (24%). A third say it should be illegal.

Democrats are divided about whether abortion should be legal or illegal at 24 weeks, with 34% saying it should be legal, 29% saying it should be illegal, and 21% saying it depends.

There also is considerable division among each partisan group by ideology. At six weeks of pregnancy, just one-in-five conservative Republicans (19%) say that abortion should be legal; moderate and liberal Republicans are twice as likely as their conservative counterparts to say this (39%).

At the same time, about half of liberal Democrats (48%) say abortion at 24 weeks should be legal, while 17% say it should be illegal. Among conservative and moderate Democrats, the pattern is reversed: A plurality (39%) say abortion at this stage should be illegal, while 24% say it should be legal.

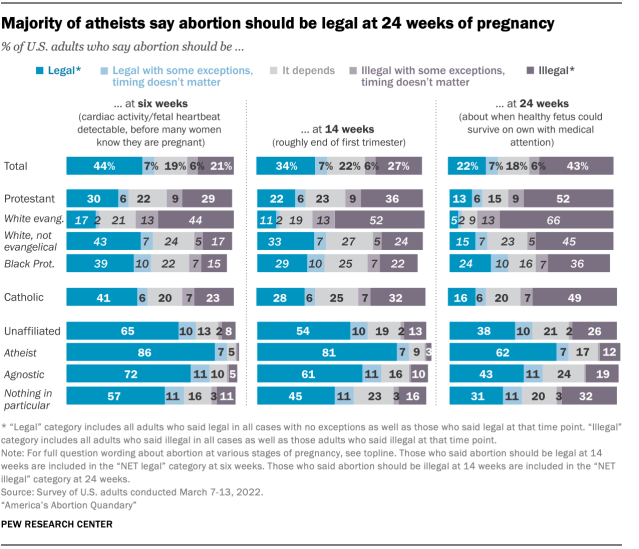

Christian adults are far less likely than religiously unaffiliated Americans to say abortion should be legal at each stage of pregnancy.

Among Protestants, White evangelicals stand out for their opposition to abortion. At six weeks of pregnancy, for example, 44% say abortion should be illegal, compared with 17% of White non-evangelical Protestants and 15% of Black Protestants. This pattern also is evident at 14 and 24 weeks of pregnancy, when half or more of White evangelicals say abortion should be illegal.

At six weeks, a plurality of Catholics (41%) say abortion should be legal, while smaller shares say it depends or it should be illegal. But by 24 weeks, about half of Catholics (49%) say abortion should be illegal.

Among adults who are religiously unaffiliated, atheists stand out for their views. They are the only group in which a sizable majority says abortion should be legal at each point in a pregnancy. Even at 24 weeks, 62% of self-described atheists say abortion should be legal, compared with smaller shares of agnostics (43%) and those who say their religion is “nothing in particular” (31%).

As is the case with adults overall, most religiously affiliated and religiously unaffiliated adults who originally say that abortion should be illegal or “it depends” at 24 weeks go on to say either it should be legal or it depends if the pregnant woman’s life is in danger or the baby would be born with severe disabilities. Few (4% and 5%, respectively) say abortion should be illegal at 24 weeks in these situations.

Abortion and circumstances of pregnancy

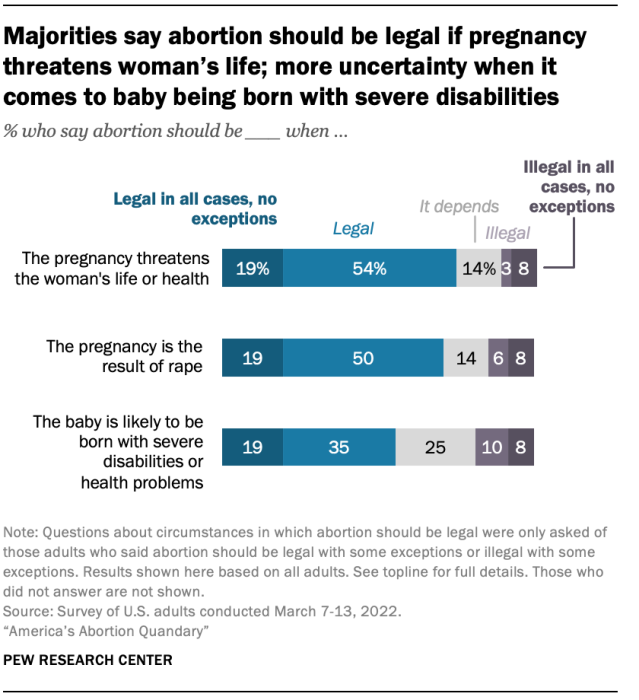

The stage of the pregnancy is not the only factor that shapes people’s views of when abortion should be legal. Sizable majorities of U.S. adults say that abortion should be legal if the pregnancy threatens the life or health of the pregnant woman (73%) or if pregnancy is the result of rape (69%).

There is less consensus when it comes to circumstances in which a baby may be born with severe disabilities or health problems: 53% of Americans overall say abortion should be legal in such circumstances, including 19% who say abortion should be legal in all cases and 35% who say there are some situations where abortions should be illegal, but that it should be legal in this specific type of case. A quarter of adults say “it depends” in this situation, and about one-in-five say it should be illegal (10% who say illegal in this specific circumstance and 8% who say illegal in all circumstances).

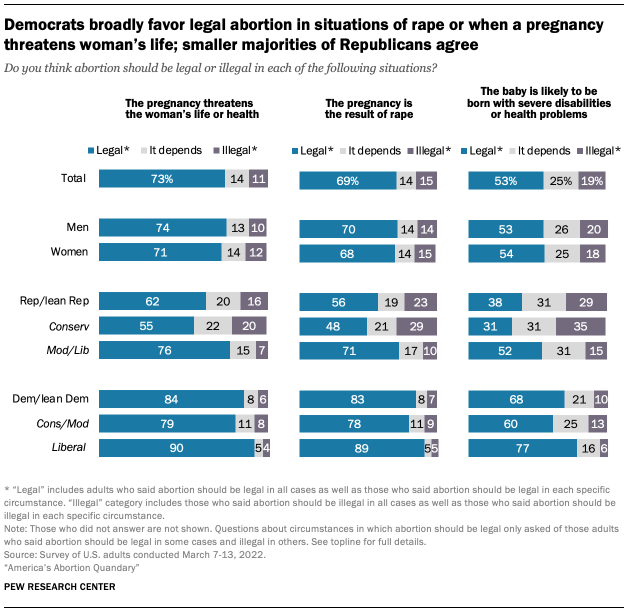

There are sizable divides between and among partisans when it comes to views of abortion in these situations. Overall, Republicans are less likely than Democrats to say abortion should be legal in each of the three circumstances outlined in the survey. However, both partisan groups are less likely to say abortion should be legal when the baby may be born with severe disabilities or health problems than when the woman’s life is in danger or the pregnancy is the result of rape.

Just as there are wide gaps among Republicans by ideology on whether how long a woman has been pregnant should be a factor in determining abortion’s legality, there are large gaps when it comes to circumstances in which abortions should be legal. For example, while a clear majority of moderate and liberal Republicans (71%) say abortion should be permitted when the pregnancy is the result of rape, conservative Republicans are more divided. About half (48%) say it should be legal in this situation, while 29% say it should be illegal and 21% say it depends.

The ideological gaps among Democrats are slightly less pronounced. Most Democrats say abortion should be legal in each of the three circumstances – just to varying degrees. While 77% of liberal Democrats say abortion should be legal if a baby will be born with severe disabilities or health problems, for example, a smaller majority of conservative and moderate Democrats (60%) say the same.

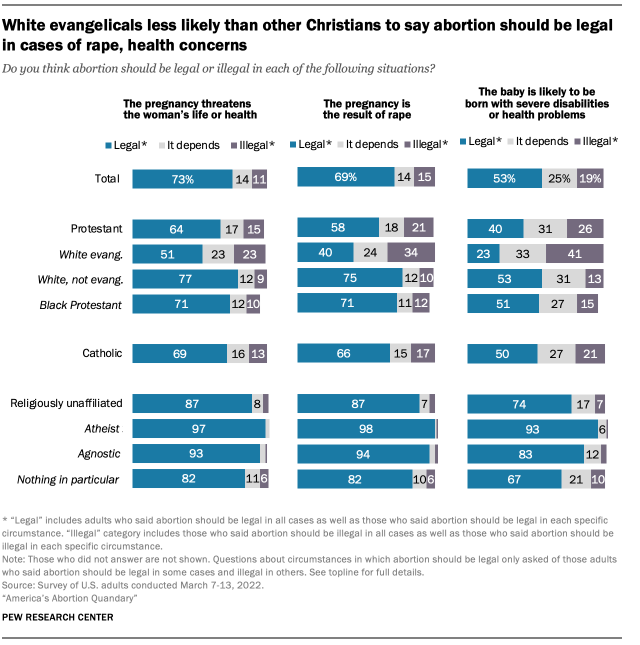

White evangelical Protestants again stand out for their views on abortion in various circumstances; they are far less likely than White non-evangelical or Black Protestants to say abortion should be legal across each of the three circumstances described in the survey.

While about half of White evangelical Protestants (51%) say abortion should be legal if a pregnancy threatens the woman’s life or health, clear majorities of other Protestant groups and Catholics say this should be the case. The same pattern holds in views of whether abortion should be legal if the pregnancy is the result of rape. Most White non-evangelical Protestants (75%), Black Protestants (71%) and Catholics (66%) say abortion should be permitted in this instance, while White evangelicals are more divided: 40% say it should be legal, while 34% say it should be illegal and about a quarter say it depends.

Mirroring the pattern seen among adults overall, opinions are more varied about a situation where a baby might be born with severe disabilities or health issues. For instance, half of Catholics say abortion should be legal in such cases, while 21% say it should be illegal and 27% say it depends on the situation.

Most religiously unaffiliated adults – including overwhelming majorities of self-described atheists – say abortion should be legal in each of the three circumstances.

Parental notification for minors seeking abortion

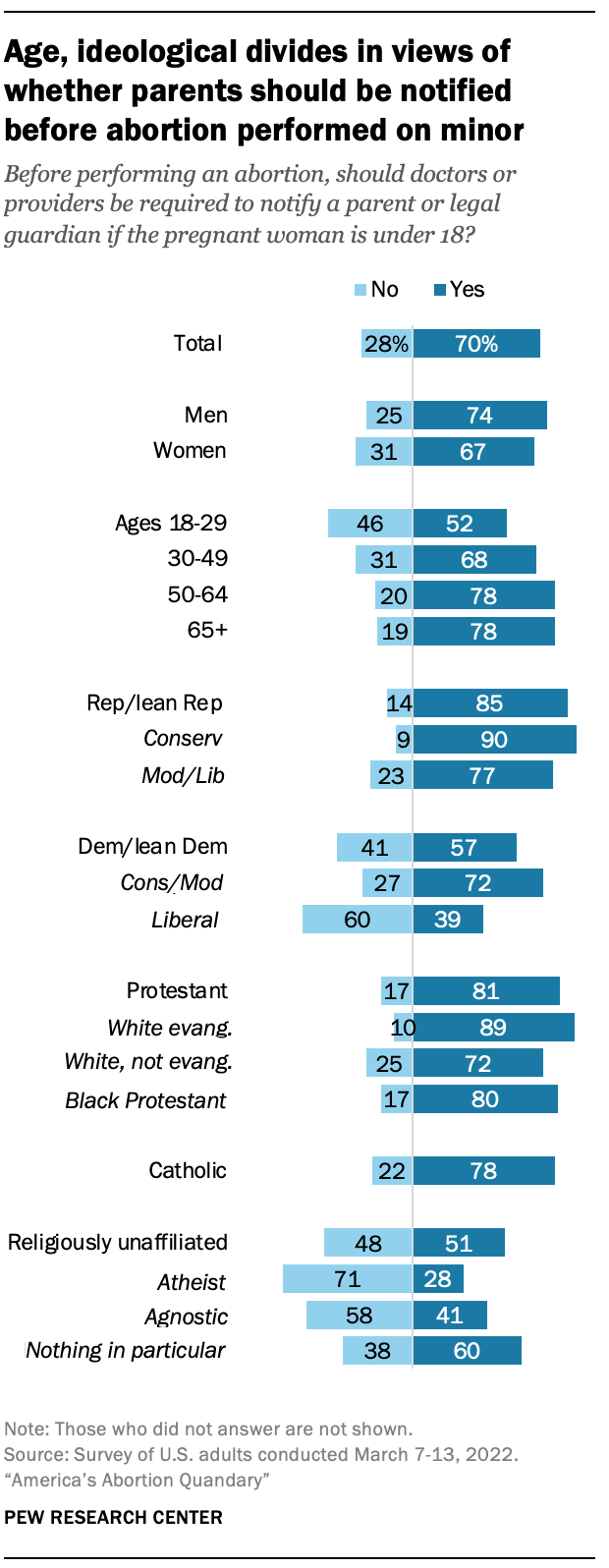

Seven-in-ten U.S. adults say that doctors or other health care providers should be required to notify a parent or legal guardian if the pregnant woman seeking an abortion is under 18, while 28% say they should not be required to do so.

Women are slightly less likely than men to say this should be a requirement (67% vs. 74%). And younger adults are far less likely than those who are older to say a parent or guardian should be notified before a doctor performs an abortion on a pregnant woman who is under 18. In fact, about half of adults ages 18 to 24 (53%) say a doctor should not be required to notify a parent. By contrast, 64% of adults ages 25 to 29 say doctors should be required to notify parents of minors seeking an abortion, as do 68% of adults ages 30 to 49 and 78% of those 50 and older.

A large majority of Republicans (85%) say that a doctor should be required to notify the parents of a minor before an abortion, though conservative Republicans are somewhat more likely than moderate and liberal Republicans to take this position (90% vs. 77%).

The ideological divide is even more pronounced among Democrats. Overall, a slim majority of Democrats (57%) say a parent should be notified in this circumstance, but while 72% of conservative and moderate Democrats hold this view, just 39% of liberal Democrats agree.

By and large, most Protestant (81%) and Catholic (78%) adults say doctors should be required to notify parents of minors before an abortion. But religiously unaffiliated Americans are more divided. Majorities of both atheists (71%) and agnostics (58%) say doctors should not be required to notify parents of minors seeking an abortion, while six-in-ten of those who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” say such notification should be required.

Penalties for abortions performed illegally

Americans are divided over who should be penalized – and what that penalty should be – in a situation where an abortion occurs illegally.

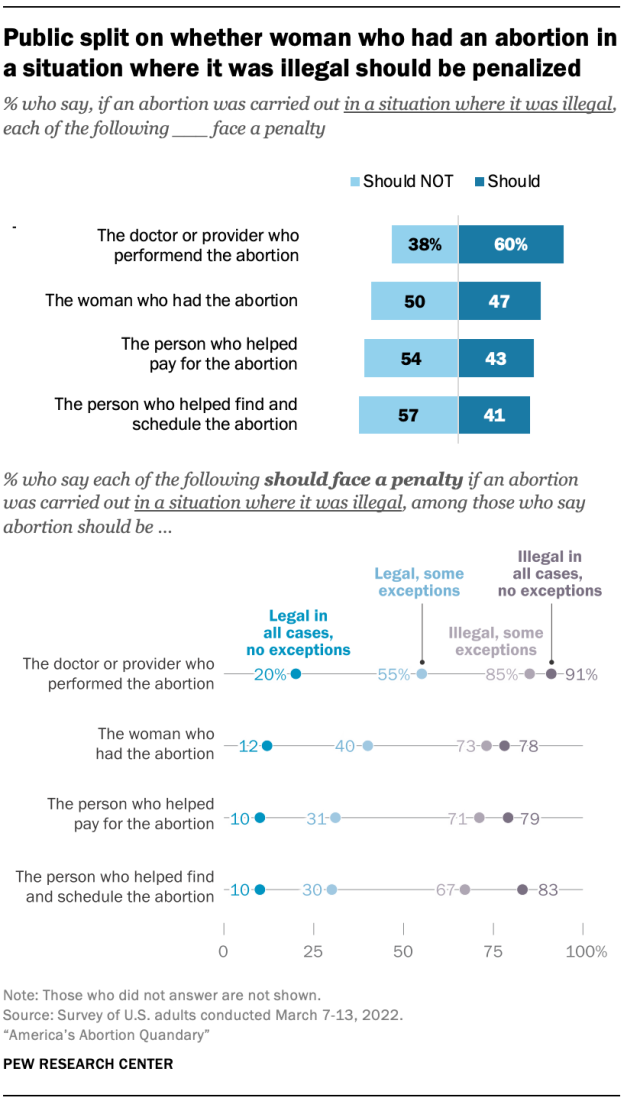

Overall, a 60% majority of adults say that if a doctor or provider performs an abortion in a situation where it is illegal, they should face a penalty. But there is less agreement when it comes to others who may have been involved in the procedure.

While about half of the public (47%) says a woman who has an illegal abortion should face a penalty, a nearly identical share (50%) says she should not. And adults are more likely to say people who help find and schedule or pay for an abortion in a situation where it is illegal should not face a penalty than they are to say they should.

Views about penalties are closely correlated with overall attitudes about whether abortion should be legal or illegal. For example, just 20% of adults who say abortion should be legal in all cases without exception think doctors or providers should face a penalty if an abortion were carried out in a situation where it was illegal. This compares with 91% of those who think abortion should be illegal in all cases without exceptions. Still, regardless of how they feel about whether abortion should be legal or not, Americans are more likely to say a doctor or provider should face a penalty compared with others involved in the procedure.

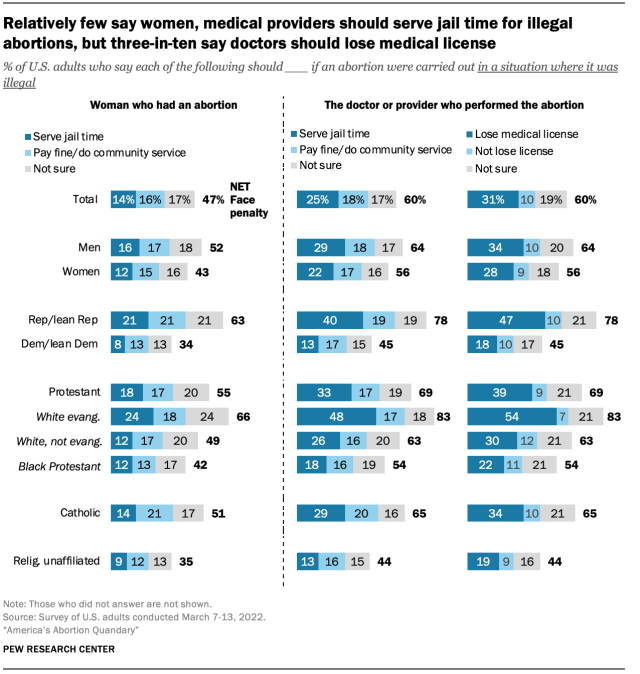

Among those who say medical providers and/or women should face penalties for illegal abortions, there is no consensus about whether they should get jail time or a less severe punishment. Among U.S. adults overall, 14% say women should serve jail time if they have an abortion in a situation where it is illegal, while 16% say they should receive a fine or community service and 17% say they are not sure what the penalty should be.

A somewhat larger share of Americans (25%) say doctors or other medical providers should face jail time for providing illegal abortion services, while 18% say they should face fines or community service and 17% are not sure. About three-in-ten U.S. adults (31%) say doctors should lose their medical license if they perform an abortion in a situation where it is illegal.

Men are more likely than women to favor penalties for the woman or doctor in situations where abortion is illegal. About half of men (52%) say women should face a penalty, while just 43% of women say the same. Similarly, about two-thirds of men (64%) say a doctor should face a penalty, while 56% of women agree.

Republicans are considerably more likely than Democrats to say both women and doctors should face penalties – including jail time. For example, 21% of Republicans say the woman who had the abortion should face jail time, and 40% say this about the doctor who performed the abortion. Among Democrats, far smaller shares say the woman (8%) or doctor (13%) should serve jail time.

White evangelical Protestants are more likely than other Protestant groups to favor penalties for abortions in situations where they are illegal. Fully 24% say the woman who had the abortion should serve time in jail, compared with just 12% of White non-evangelical Protestants or Black Protestants. And while about half of White evangelicals (48%) say doctors who perform illegal abortions should serve jail time, just 26% of White non-evangelical Protestants and 18% of Black Protestants share this view.

- Only respondents who said that abortion should be legal in some cases but not others and that how long a woman has been pregnant should matter in determining whether abortion should be legal received questions about abortion’s legality at specific points in the pregnancy. ↩

Sign up for our Religion newsletter

Sent weekly on Wednesday

Report Materials

Table of contents, majority of public disapproves of supreme court’s decision to overturn roe v. wade, wide partisan gaps in abortion attitudes, but opinions in both parties are complicated, key facts about the abortion debate in america, about six-in-ten americans say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, fact sheet: public opinion on abortion, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Princeton Legal Journal

The First Amendment and the Abortion Rights Debate

Sofia Cipriano

Following Dobbs v. Jackson ’s (2022) reversal of Roe v. Wade (1973) — and the subsequent revocation of federal abortion protection — activists and scholars have begun to reconsider how to best ground abortion rights in the Constitution. In the past year, numerous Jewish rights groups have attempted to overturn state abortion bans by arguing that abortion rights are protected by various state constitutions’ free exercise clauses — and, by extension, the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. While reframing the abortion rights debate as a question of religious freedom is undoubtedly strategic, the Free Exercise Clause is not the only place to locate abortion rights: the Establishment Clause also warrants further investigation.

Roe anchored abortion rights in the right to privacy — an unenumerated right with a long history of legal recognition. In various cases spanning the past two centuries, t he Supreme Court located the right to privacy in the First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth, and Fourteenth Amendments . Roe classified abortion as a fundamental right protected by strict scrutiny, meaning that states could only regulate abortion in the face of a “compelling government interest” and must narrowly tailor legislation to that end. As such, Roe ’s trimester framework prevented states from placing burdens on abortion access in the first few months of pregnancy. After the fetus crosses the viability line — the point at which the fetus can survive outside the womb — states could pass laws regulating abortion, as the Court found that “the potentiality of human life” constitutes a “compelling” interest. Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey (1992) later replaced strict scrutiny with the weaker “undue burden” standard, giving states greater leeway to restrict abortion access. Dobbs v. Jackson overturned both Roe and Casey , leaving abortion regulations up to individual states.

While Roe constituted an essential step forward in terms of abortion rights, weaknesses in its argumentation made it more susceptible to attacks by skeptics of substantive due process. Roe argues that the unenumerated right to abortion is implied by the unenumerated right to privacy — a chain of logic which twice removes abortion rights from the Constitution’s language. Moreover, Roe’s trimester framework was unclear and flawed from the beginning, lacking substantial scientific rationale. As medicine becomes more and more advanced, the arbitrariness of the viability line has grown increasingly apparent.

As abortion rights supporters have looked for alternative constitutional justifications for abortion rights, the First Amendment has become increasingly more visible. Certain religious groups — particularly Jewish groups — have argued that they have a right to abortion care. In Generation to Generation Inc v. Florida , a religious rights group argued that Florida’s abortion ban (HB 5) constituted a violation of the Florida State Constitution: “In Jewish law, abortion is required if necessary to protect the health, mental or physical well-being of the woman, or for many other reasons not permitted under the Act. As such, the Act prohibits Jewish women from practicing their faith free of government intrusion and thus violates their privacy rights and religious freedom.” Similar cases have arisen in Indiana and Texas. Absent constitutional protection of abortion rights, the Christian religious majorities in many states may unjustly impose their moral and ethical code on other groups, implying an unconstitutional religious hierarchy.

Cases like Generation to Generation Inc v. Florida may also trigger heightened scrutiny status in higher courts; The Religious Freedom Restoration Act (1993) places strict scrutiny on cases which “burden any aspect of religious observance or practice.”

But framing the issue as one of Free Exercise does not interact with major objections to abortion rights. Anti-abortion advocates contend that abortion is tantamount to murder. An anti-abortion advocate may argue that just as religious rituals involving human sacrifice are illegal, so abortion ought to be illegal. Anti-abortion advocates may be able to argue that abortion bans hold up against strict scrutiny since “preserving potential life” constitutes a “compelling interest.”

The question of when life begins—which is fundamentally a moral and religious question—is both essential to the abortion debate and often ignored by left-leaning activists. For select Christian advocacy groups (as well as other anti-abortion groups) who believe that life begins at conception, abortion bans are a deeply moral issue. Abortion bans which operate under the logic that abortion is murder essentially legislate a definition of when life begins, which is problematic from a First Amendment perspective; the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment prevents the government from intervening in religious debates. While numerous legal thinkers have associated the abortion debate with the First Amendment, this argument has not been fully litigated. As an amicus brief filed in Dobbs by the Freedom From Religion Foundation, Center for Inquiry, and American Atheists points out, anti-abortion rhetoric is explicitly religious: “There is hardly a secular veil to the religious intent and positions of individuals, churches, and state actors in their attempts to limit access to abortion.” Justice Stevens located a similar issue with anti-abortion rhetoric in his concurring opinion in Webster v. Reproductive Health Services (1989) , stating: “I am persuaded that the absence of any secular purpose for the legislative declarations that life begins at conception and that conception occurs at fertilization makes the relevant portion of the preamble invalid under the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the Federal Constitution.” Judges who justify their judicial decisions on abortion using similar rhetoric blur the line between church and state.

Framing the abortion debate around religious freedom would thus address the two main categories of arguments made by anti-abortion activists: arguments centered around issues with substantive due process and moral objections to abortion.

Conservatives may maintain, however, that legalizing abortion on the federal level is an Establishment Clause violation to begin with, since the government would essentially be imposing a federal position on abortion. Many anti-abortion advocates favor leaving abortion rights up to individual states. However, in the absence of recognized federal, constitutional protection of abortion rights, states will ban abortion. Protecting religious freedom of the individual is of the utmost importance — the United States government must actively intervene in order to uphold the line between church and state. Protecting abortion rights would allow everyone in the United States to act in accordance with their own moral and religious perspectives on abortion.

Reframing the abortion rights debate as a question of religious freedom is the most viable path forward. Anchoring abortion rights in the Establishment Clause would ensure Americans have the right to maintain their own personal and religious beliefs regarding the question of when life begins. In the short term, however, litigants could take advantage of Establishment Clauses in state constitutions. Yet, given the swing of the Court towards expanding religious freedom protections at the time of writing, Free Exercise arguments may prove better at securing citizens a right to an abortion.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

There Are More Than Two Sides to the Abortion Debate

Readers share their perspectives.

Sign up for Conor’s newsletter here.

Earlier this week I curated some nuanced commentary on abortion and solicited your thoughts on the same subject. What follows includes perspectives from several different sides of the debate. I hope each one informs your thinking, even if only about how some other people think.

We begin with a personal reflection.

Cheryl was 16 when New York State passed a statute legalizing abortion and 19 when Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973. At the time she was opposed to the change, because “it just felt wrong.” Less than a year later, her mother got pregnant and announced she was getting an abortion.

She recalled:

My parents were still married to each other, and we were financially stable. Nonetheless, my mother’s announcement immediately made me a supporter of the legal right to abortion. My mother never loved me. My father was physically abusive and both parents were emotionally and psychologically abusive on a virtually daily basis. My home life was hellish. When my mother told me about the intended abortion, my first thought was, “Thank God that they won’t be given another life to destroy.” I don’t deny that there are reasons to oppose abortion. As a feminist and a lawyer, I can now articulate several reasons for my support of legal abortion: a woman’s right to privacy and autonomy and to the equal protection of the laws are near the top of the list. (I agree with Ruth Bader Ginsburg that equal protection is a better legal rationale for the right to abortion than privacy.) But my emotional reaction from 1971 still resonates with me. Most people who comment on the issue, on both sides, do not understand what it is to go through childhood unloved. It is horrific beyond my powers of description. To me, there is nothing more immoral than forcing that kind of life on any child. Anti-abortion activists often like to ask supporters of abortion rights: “Well, what if your mother had decided to abort you?” All I can say is that I have spent a great portion of my life wishing that my mother had done exactly that.

Steven had related thoughts:

I have respect for the idea that there should be some restrictions on abortion. But the most fundamental, and I believe flawed, unstated assumptions of the anti-choice are that A) they are acting on behalf of the fetus, and more importantly B) they know what the fetus would want. I would rather not have been born than to have been born to a mother who did not want me. All children should be wanted children—for the sake of all concerned. You can say that different fetuses would “want” different things—though it’s hard to say a clump of cells “wants” anything. How would we know? The argument lands, as it does generally, with the question of who should be making that decision. Who best speaks in the fetus’s interests? Who is better positioned morally or practically than the expectant mother?

Geoff self-describes as “pro-life” and guilty of some hypocrisy. He writes:

I’m pro-life because I have a hard time with the dehumanization that comes with the extremes of abortion on demand … Should it be okay to get an abortion when you find your child has Down syndrome? What of another abnormality? Or just that you didn’t want a girl? Any argument that these are legitimate reasons is disturbing. But so many of the pro-life just don’t seem to care about life unless it’s a fetus they can force a woman to carry. The hypocrisy is real. While you can argue that someone on death row made a choice that got them to that point, whereas a fetus had no say, I find it still hard to swallow that you can claim one life must be protected and the other must be taken. Life should be life. At least in the Catholic Church this is more consistent. I myself am guilty of a degree of hypocrisy. My wife and I used IVF to have our twins. There were other embryos created and not inserted. They were eventually destroyed. So did I support killing a life? Maybe? I didn’t want to donate them for someone else to give birth to—it felt wrong to think my twins may have brothers or sisters in the world they would never know about. Yet does that mean I was more willing to kill my embryos than to have them adopted? Sure seems like it. So I made a morality deal with myself and moved the goal post—the embryos were not yet in a womb and were so early in development that they couldn’t be considered fully human life. They were still potential life.

Colleen, a mother of three, describes why she ended her fourth pregnancy:

I was young when I first engaged this debate. Raised Catholic, anti-choice, and so committed to my position that I broke my parents’ hearts by giving birth during my junior year of college. At that time, my sense of my own rights in the matter was almost irrelevant. I was enslaved by my body. One husband and two babies later I heard a remarkable Jesuit theologian (I wish I could remember his name) speak on the matter and he, a Catholic priest, framed it most directly. We prioritize one life over another all the time. Most obviously, we justify the taking of life in war with all kinds of arguments that often turn out to be untrue. We also do so as we decide who merits access to health care or income support or other life-sustaining things. So the question of abortion then boils down to: Who gets to decide? Who gets to decide that the life of a human in gestation is actually more valuable than the life of the woman who serves as host—or vice versa? Who gets to decide when the load a woman is being asked to carry is more than she can bear? The state? Looking back over history, he argued that he certainly had more faith in the person most involved to make the best decision than in any formalized structure—church or state—created by men. Every form of birth control available failed me at one point or another, so when yet a 4th pregnancy threatened to interrupt the education I had finally been able to resume, I said “Enough.” And as I cried and struggled to come to that position, the question that haunted me was “Doesn’t MY life count?” And I decided it did.

Florence articulates what it would take to make her anti-abortion:

What people seem to miss is that depriving a woman of bodily autonomy is slavery. A person who does not control his/her own body is—what? A slave. At its simplest, this is the issue. I will be anti-abortion when men and women are equal in all facets of life—wages, chores, child-rearing responsibilities, registering for the draft, to name a few obvious ones. When there is birth control that is effective, where women do not bear most of the responsibility. We need to raise boys who are respectful to girls, who do not think that they are entitled to coerce a girl into having sex that she doesn’t really want or is unprepared for. We need for sex education to be provided in schools so young couples know what they are getting into when they have sex. Especially the repercussions of pregnancy. We need to raise girls who are confident and secure, who don’t believe they need a male to “complete” them. Who have enough agency to say “no” and to know why. We have to make abortion unnecessary … We have so far to go. If abortion is ruled illegal, or otherwise curtailed, we will never know if the solutions to women’s second-class status will work. We will be set back to the 50s or worse. I don’t want to go back. Women have fought from the beginning of time to own their bodies and their lives. To deprive us of all of the amazing strides forward will affect all future generations.

Similarly, Ben agrees that in our current environment, abortion is often the only way women can retain equal citizenship and participation in society, but also agrees with pro-lifers who critique the status quo, writing that he doesn’t want a world where a daughter’s equality depends on her right “to perform an act of violence on their potential descendents.” Here’s how he resolves his conflictedness:

Conservatives arguing for a more family-centered society, in which abortion is unnecessary to protect the equal rights of women, are like liberals who argue for defunding the police and relying on addiction, counselling, and other services, in that they argue for removing what offends them without clear, credible plans to replace the functions it serves. I sincerely hope we can move towards a world in which armed police are less necessary. But before we can remove the guardrails of the police, we need to make the rest of the changes so that the world works without them. Once liberal cities that have shown interest in defunding the police can prove that they can fund alternatives, and that those alternatives work, then I will throw my support behind defunding the police. Similarly, once conservative politicians demonstrate a credible commitment to an alternative vision of society in which women are supported, families are not taken for granted, and careers and short-term productivity are not the golden calves they are today, I will be willing to support further restrictions on abortion. But until I trust that they are interested in solving the underlying problem (not merely eliminating an aspect they find offensive), I will defend abortion, as terrible as it is, within reasonable legal limits.

Two readers objected to foregrounding gender equality. One emailed anonymously, writing in part:

A fetus either is or isn’t a person. The reason I’m pro-life is that I’ve never heard a coherent defense of the proposition that a fetus is not a person, and I’m not sure one can be made. I’ve read plenty of progressive commentary, and when it bothers to make an argument for abortion “rights” at all, it talks about “the importance of women’s healthcare” or something as if that were the issue.

Christopher expanded on that last argument:

Of the many competing ethical concerns, the one that trumps them all is the status of the fetus. It is the only organism that gets destroyed by the procedure. Whether that is permissible trumps all other concerns. Otherwise important ethical claims related to a woman’s bodily autonomy, less relevant social disparities caused by the differences in men’s and women’s reproductive functions, and even less relevant differences in partisan commitments to welfare that would make abortion less appealing––all of that is secondary. The relentless strategy by the pro-choice to sidestep this question and pretend that a woman’s right to bodily autonomy is the primary ethical concern is, to me, somewhere between shibboleth and mass delusion. We should spend more time, even if it’s unproductive, arguing about the status of the fetus, because that is the question, and we should spend less time indulging this assault-on-women’s-rights narrative pushed by the Left.

Jean is critical of the pro-life movement:

Long-acting reversible contraceptives, robust, science-based sex education for teens, and a stronger social safety net would all go a remarkable way toward decreasing the number of abortions sought. Yet all the emphasis seems to be on simply making abortion illegal. For many, overturning Roe v. Wade is not about reducing abortions so much as signalling that abortion is wrong. If so-called pro-lifers were as concerned about abortion as they seem to be, they would spend more time, effort, and money supporting efforts to reduce the need for abortion—not simply trying to make it illegal without addressing why women seek it out. Imagine, in other words, a world where women hardly needed to rely on abortion for their well-being and ability to thrive. Imagine a world where almost any woman who got pregnant had planned to do so, or was capable of caring for that child. What is the anti-abortion movement doing to promote that world?

Destiny has one relevant answer. She writes:

I run a pro-life feminist group and we often say that our goal is not to make abortion illegal, but rather unnecessary and unthinkable by supporting women and humanizing the unborn child so well.

Robert suggests a different focus:

Any well-reasoned discussion of abortion policy must include contraception because abortion is about unwanted children brought on by poorly reasoned choices about sex. Such choices will always be more emotional than rational. Leaving out contraception makes it an unrealistic, airy discussion of moral philosophy. In particular, we need to consider government-funded programs of long-acting reversible contraception which enable reasoned choices outside the emotional circumstances of having sexual intercourse.

Last but not least, if anyone can unite the pro-life and pro-choice movements, it’s Errol, whose thoughts would rankle majorities in both factions as well as a majority of Americans. He writes:

The decision to keep the child should not be left up solely to the woman. Yes, it is her body that the child grows in, however once that child is birthed it is now two people’s responsibility. That’s entirely unfair to the father when he desired the abortion but the mother couldn’t find it in her heart to do it. If a woman wants to abort and the man wants to keep it, she should abort. However I feel the same way if a man wants to abort. The next 18+ years of your life are on the line. I view that as a trade-off that warrants the male’s input. Abortion is a conversation that needs to be had by two people, because those two will be directly tied to the result for a majority of their life. No one else should be involved with that decision, but it should not be solely hers, either.

Thanks to all who contributed answers to this week’s question, whether or not they were among the ones published. What subjects would you like to see fellow readers address in future installments? Email [email protected].

By submitting an email, you’ve agreed to let us use it—in part or in full—in this newsletter and on our website. Published feedback includes a writer’s full name, city, and state, unless otherwise requested in your initial note.

share this!

June 23, 2022

Abortion and bioethics: Principles to guide US abortion debates

by Nancy S. Jecker, The Conversation

The U.S. Supreme Court will soon decide the fate of Roe v. Wade , the landmark 1973 decision that established the nationwide right to choose an abortion. If the court's decision hews close to the leaked draft opinion first published by Politico in May 2022, the court's new conservative majority will overturn Roe.

Rancorous debate about the ruling is often dominated by politics . Ethics garners less attention, although it lies at the heart of the legal controversy. As a philosopher and bioethicist , I study moral problems in medicine and health policy , including abortion.

Bioethical approaches to abortion often appeal to four principles : respect patients' autonomy; nonmaleficence, or "do no harm"; beneficence, or provide beneficial care; and justice. These principles were first developed during the 1970s to guide research involving human subjects . Today, they are essential guides for many doctors and ethicists in challenging medical cases .

Patient autonomy

The ethical principle of autonomy states that patients are entitled to make decisions about their own medical care when able. The American Medical Association's Code of Medical Ethics recognizes a patient's right to " receive information and ask questions about recommended treatments " in order to "make well-considered decisions about care." Respect for autonomy is enshrined in laws governing informed consent , which protect patients' right to know the medical options available and make an informed voluntary decision.

Some bioethicists regard respect for autonomy as lending firm support to the right to choose abortion, arguing that if a pregnant person wishes to end their pregnancy, the state should not interfere. According to one interpretation of this view, the principle of autonomy means that a person owns their body and should be free to decide what happens in and to it .

Abortion opponents do not necessarily challenge the soundness of respecting people's autonomy, but may disagree about how to interpret this principle. Some regard a pregnant person as " two patients "—the pregnant person and the fetus .

One way to reconcile these views is to say that as an immature human being becomes " increasingly self-conscious, rational and autonomous it is harmed to an increasing degree ," as philosopher Jeff McMahan writes. In this view, a late-stage fetus has more interest in its future than a fertilized egg, and therefore the later in pregnancy an abortion takes place, the more it may hinder the fetus's developing interests. In the U.S., where 92.7% of abortions occur at or before 13 weeks' gestation , a pregnant person's rights may often outweigh those attributed to the fetus. Later in pregnancy, however, rights attributed to the fetus may assume greater weight. Balancing these competing claims remains contentious.

Nonmaleficence and beneficence

The ethical principle of "do no harm" forbids intentionally harming or injuring a patient. It demands medically competent care that minimizes risks. Nonmaleficence is often paired with a principle of beneficence, a duty to benefit patients. Together, these principles emphasize doing more good than harm .

Minimizing the risk of harm figures prominently in the World Health Organization's opposition to bans on abortion because pregnant people facing barriers to abortion often resort to unsafe methods, which represent a leading cause of avoidable maternal deaths and morbidities worldwide .

Although 97% of unsafe abortions occur in developing countries , developed countries that have narrowed abortion access have produced unintended harms. In Poland , for example, doctors fearing prosecution have hesitated to administer cancer treatments during pregnancy or remove a fetus after a pregnant person's water breaks early in the pregnancy, before the fetus is viable. In the U.S., restrictive abortion laws in some states, like Texas, have complicated care for miscarriages and high-risk pregnancies , putting pregnant people's lives at risk.

However, Americans who favor overturning Roe are primarily concerned about fetal harm. Regardless of whether or not the fetus is considered a person, the fetus might have an interest in avoiding pain. Late in pregnancy, some ethicists think that humane care for pregnant people should include minimizing fetal pain irrespective of whether a pregnancy continues. Neuroscience teaches that the human capacity to experience feeling or sensation requires consciousness, , which develops between 24 and 28 weeks gestation.

Justice, a final principle of bioethics, requires treating similar cases similarly. If the pregnant person and fetus are moral equals, many argue that it would be unjust to kill the fetus except in self-defense, if the fetus threatens the pregnant person's life. Others hold that even in self-defense, terminating the fetus's life is wrong because a fetus is not morally responsible for any threat it poses .

Yet defenders of abortion point out that even if abortion results in the death of an innocent person, that is not its goal. If the ethics of an action is judged by its goals, then abortion might be justified in cases where it realizes an ethical aim, such as saving a woman's life or protecting a family's ability to care for their current children. Defenders of abortion also argue that even if the fetus has a right to life, a person does not have a right to everything they need to stay alive . For example, having a right to life does not entail a right to threaten another's health or life, or ride roughshod over another's life plans and goals.

Justice also deals with the fair distribution of benefits and burdens. Among wealthy countries, the U.S. has the highest rate of deaths linked to pregnancy and childbirth. Without legal protection for abortion, pregnancy and childbirth for Americans could become even more risky. Studies show that women are more likely to die while pregnant or shortly thereafter in states with the most restrictive abortion policies .

Minority groups may have the most to lose if the right to choose abortion is not upheld because they utilize a disproportionate share of abortion services . In Mississippi, for example, people of color represent 44% of the population, but 81% of those receiving abortions . Other states follow a similar pattern, leading some health activists to conclude that "abortion restrictions are racist."

Other marginalized groups, including low-income families, could also be hard hit by abortion restrictions because abortions are expected to get pricier .

Politics aside, abortion raises profound ethical questions that remain unsettled, which courts are left to settle using the blunt instrument of law. In this sense, abortion " begins as a moral argument and ends as a legal argument ," in the words of law and ethics scholar Katherine Watson .

Putting to rest legal controversies surrounding abortion would require reaching moral consensus. Short of that, articulating our own moral views and understanding others' can bring all sides closer to a principled compromise .

Provided by The Conversation

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Tropical cyclones may be an unlikely ally in the battle against ocean hypoxia

26 minutes ago

JWST observations explore molecular outflows of a nearby merging galaxy

27 minutes ago

Simple equations clarify cloud climate conundrum

4 hours ago

Romania center explores world's most powerful laser

Mar 31, 2024

A cosmic 'speed camera' just revealed the staggering speed of neutron star jets in a world first

Mar 30, 2024

Saturday Citations: 100-year-old milk, hot qubits and another banger from the Event Horizon Telescope project

Curiosity rover searches for new clues about Mars' ancient water

Study says since 1979 climate change has made heat waves last longer, spike hotter, hurt more people

Scientist taps into lobsters' unusual habits to conquer the more than 120-year quest to farm them

Mar 29, 2024

Blind people can hear and feel April's total solar eclipse with new technology

Relevant physicsforums posts, cover songs versus the original track, which ones are better.

14 hours ago

How did ‘concern’ semantically shift to mean ‘commercial enterprise' ?

Interesting anecdotes in the history of physics.

23 hours ago

The new Shogun show

History of railroad safety - spotlight on current derailments.

Mar 27, 2024

Metal, Rock, Instrumental Rock and Fusion

More from Art, Music, History, and Linguistics

Related Stories

Less than 1% of abortions take place in the third trimester: Here's why people get them

May 17, 2022

Michigan limits reproductive health services that midwives, nurses can provide

Apr 28, 2022

What is 'personhood?' The ethics question that needs a closer look in abortion debates

May 13, 2022

Limits on early abortion drive more women to get them later

Jun 2, 2022

US abortion trends have changed since landmark 1973 ruling

May 3, 2022

Supreme court allows legal challenges to Texas abortion law, but doesn't overturn it

Dec 10, 2021

Recommended for you

Song lyrics have become simpler and more repetitive since 1980, study finds

Mar 28, 2024

Low resting heart rate in women is associated with criminal offending, unintentional injuries

Your emotional reaction to climate change may impact the policies you support, study finds

Value-added tax data could help countries prepare better for crises

Survey study shows workers with more flexibility and job security have better mental health

Mar 26, 2024

We have revealed a unique time capsule of Australia's first coastal people from 50,000 years ago

Mar 25, 2024

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

A concise history of the US abortion debate

Professor of Women's, Gender and Sexuality Studies, The Ohio State University

Disclosure statement

Treva B. Lindsey does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Ohio State University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

On Nov. 14, 1972, a controversial two-part episode of the groundbreaking television show, “Maude” aired.

Titled “Maude’s Dilemma,” the episodes chronicled the decision by the main character to have an abortion.

The landmark Supreme Court ruling in Roe v. Wade was issued two months after these episodes. The ruling affirmed the right to have an abortion during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. “Maude’s Dilemma” brought the battle over abortion from the streets and courthouses to prime-time television.

Responses to the episodes ranged from celebration to fury , which mirrored contemporary attitudes about abortion.

In the almost 50 years since Roe v. Wade, the debate over abortion has pervaded politics in the U.S.

While many may think that the political arguments over abortion now are fresh and new, scholars of women’s, medical and legal history note that this debate has a long history in the U.S.

It began at more than a century before Roe v. Wade.

The era of ‘The Pill’

Less than 10 years before “Maude’s Dilemma” aired, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first commercially produced birth control pill , Enovid-10.

Although various forms of birth control predate the birth control pill, the FDA’s approval of Enovid-10 was a watershed in the national debate around family planning and reproductive choice.

Commonly known as “The Pill,” the wider accessibility of birth control is seen as an early victory of the nascent women’s liberation movement.

Abortion also emerged as a prominent issue within this burgeoning movement. For many feminist activists of the 1960s and 1970s, women’s right to control their own reproductive lives became inextricable from the larger platform of gender equality.

From unregulated to criminalized

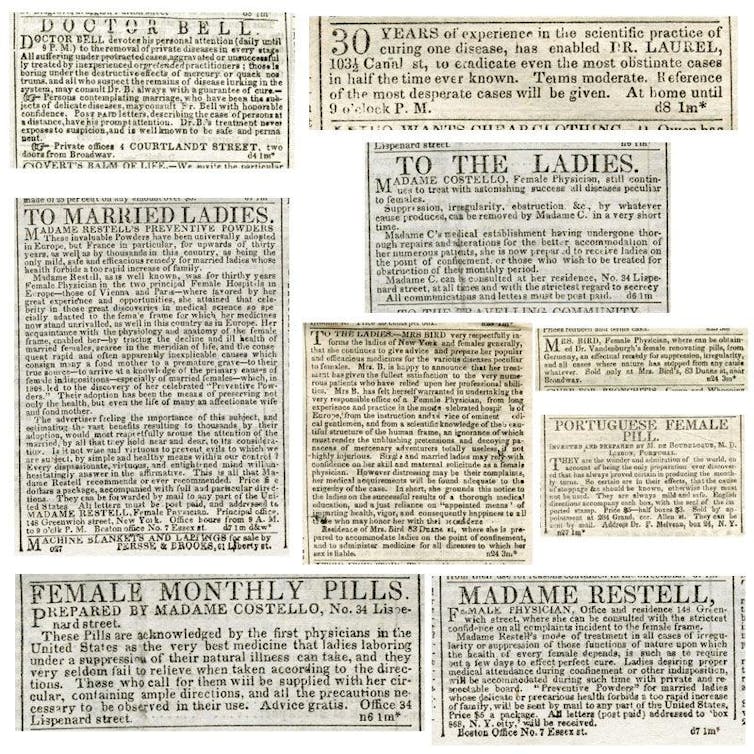

From the nation’s founding through the early 1800s, pre-quickening abortions – that is, abortions before a pregnant person feels fetal movement – were fairly common and even advertised.

Women from various backgrounds sought to end unwanted pregnancies before and during this period both in the U.S. and across the world. For example, enslaved black women in the U.S. developed abortifacients – drugs that induce abortions – and abortion practices as means to stop pregnancies after rapes by, and coerced sexual encounters with, white male slave owners.

In the mid- to late-1800s, an increasing number of states passed anti-abortion laws sparked by both moral and safety concerns. Primarily motivated by fears about high risks for injury or death, medical practitioners in particular led the charge for anti-abortion laws during this era.

By 1860, the American Medical Association sought to end legal abortion. The Comstock Law of 1873 criminalized attaining, producing or publishing information about contraception, sexually transmitted infections and diseases, and how to procure an abortion.

A spike in fears about new immigrants and newly emancipated black people reproducing at higher rates than the white population also prompted more opposition to legal abortion.

There’s an ongoing dispute about whether famous women’s activists of the 1800s such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony opposed abortion.

The anti-abortion movement references statements made by Anthony that appear to denounce abortion. Abortion rights advocates reject this understanding of Stanton, Anthony and other early American women’s rights activists’ views on abortion. They assert that statements about infanticide and motherhood have been misrepresented and inaccurately attributed to these activists.

These differing historical interpretations offer two distinct framings for both historical and contemporary abortion and anti-abortion activism.

Abortion in the sixties

By the turn of the 20th century, every state classified abortion as a felony , with some states including limited exceptions for medical emergencies and cases of rape and incest.

Despite the criminalization, by the 1930s , physicians performed almost a million abortions every year. This figure doesn’t account for abortions performed by non-medical practitioners or through undocumented channels and methods.

Nevertheless, the commonality of abortions didn’t become a hotly contested political issue until the women’s liberation movement and the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. These movements brought renewed interest in public discussions about reproductive rights, family planning, and access to legal and safe abortion services.

In 1962, the story of Sherri Finkbine , the local Phoenix, Arizona host of the children’s program, “Romper Room,” became national news.

Finkbine had four children, and had taken a drug, thalidomide, before she realized she was pregnant with her fifth child. Worried that the drug could cause severe birth defects, she tried to get an abortion in her home state, Arizona, but could not. She then traveled to Sweden for a legal abortion. Finkbine’s story is credited with helping to shift public opinion on abortion and was central to a growing, national call for abortion reform laws.

Two years after Finkbine’s story made headlines, the death of Gerri Santoro , a woman who died seeking an illegal abortion in Connecticut, ignited a renewed fervor among those seeking to legalize abortion.

Santoro’s death, along with many other reported deaths and injuries also sparked the founding of underground networks such as The Jane Collective to offer abortion services to those seeking to end pregnancies.

In 1967, Colorado became the first state to legalize abortion in cases of rape, incest, or if the pregnancy would cause permanent physical disability to the birth parent.

By the time “Maude’s Dilemma” aired, abortion was legal under specific circumstances in 20 states. A rapid growth in the number of pro- and anti-abortion organizations occurred in the 1960s and 1970s.

On Jan. 22, 1973, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Roe v. Wade nullified existing state laws that banned abortions and provided guidelines for abortion availability based upon trimesters and fetal viability. This ruling remains the most important legal statute for abortion access in modern U.S. history.

With numerous states recently passing bills banning abortions after six to eight weeks – a challenge to Roe’s legalization of abortions up to 12 weeks of pregnancy – it is unsurprising that many people are asking questions about both the history and future of abortion in the U.S. Due to current legal challenges , these bills are not yet in effect.

The legal battle to overturn or uphold Roe v. Wade is in full swing. Regardless of whether Roe v. Wade stands, history suggests that this will not be the last chapter in the political struggle over legal abortion.

- Birth control

- Abortion law

- US Supreme Court

- Abortion rights

- right to life

- Abortion pills

- women's liberation movement

Biocloud Project Manager - Australian Biocommons

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Deputy Editor - Technology

A better abortion debate is possible. Here’s where we can start.

Editor’s note: The Supreme Court overturned Roe v Wade on June 24 in a 6 to 3 decision, returning the issue of abortion restrictions to the states. America has published several essays on the decision, which was first leaked to the press in May. Read other views on abortion and the reversal of Roe v. Wade here .

In 2016, I opened my doors for what I expected would be the worst event I would ever host. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, my husband and I invited about a dozen pro-choice and pro-life friends over to eat cookies and talk about abortion.

I had been part of terrible conversations on this topic, online and off-line, and I knew I wanted something different. I had friends on both sides of the divide, and it was surreal to be in a position where we all thought the other side was complicit in grave evil.

In my work at Braver Angels, I help design debates that bring people together across the political divide . When I do my opening spiel on our format and rules, I often ask people to raise their hands if they have had a bad conversation on that night’s topic before. Whatever the topic of our debate, nearly all the hands go up. Sometimes, when a topic has been in the news, I ask people to raise their hands if they have had a bad conversation about this topic in the past week ; a majority of hands go up.

I had friends on both sides of the abortion divide, and it was surreal to be in a position where we all thought the other side was complicit in grave evil.

I ask because I want everyone in the room to see that their opponents are here as an act of trust. Even though these conversations may have never gone well in the past, the attendees at a Braver Angels debate show up because they think it is possible that disagreement can be fruitful. And the higher the stakes of the issue, the more urgency they feel to find a better way to talk about what divides us.

When I asked people to come together in my living room on that night in 2016, I didn’t rely on the parliamentary structures I use at my job; I wanted to find a way to mark this night out as different from other arguments we had had. I asked my friends to look over two readings before coming over so we would have something we all shared to ground our discussion.

The essays I chose were “Thanksgiving in Mongolia,” by Ariel Levy, and “The Empathy Exams,” by Leslie Jamison. Both authors, to the best of my knowledge, identify as pro-choice. Levy’s essay narrates her miscarriage at 19 weeks; Jamison’s essay blends her experiences as both a fake patient helping doctors in training and a real patient having an abortion. I picked these two essays because they weren’t written as salvos in the abortion debate but as attempts to reckon with what it means to care for each other.

The higher the stakes of the issue, the more urgency they feel to find a better way to talk about what divides us.

If I were making my reading list now—and if I felt I could get away with asking people to read whole books, not just articles—I’d suggest a few other works.

The first is Defenders of the Unborn: The Pro-Life Movement before Roe v. Wade, by Daniel K. Williams, a history covering the period before pro-life activism became sharply polarized. Advocating for children before birth was an important cause for progressives, who saw it as part and parcel with advocating for those who could not speak for themselves.

Another book I would recommend is The Girls Who Went Away: The Hidden History of Women Who Surrendered Children for Adoption in the Decades Before Roe v. Wade, by Ann Fessler. I picked up Fessler’s book because I wanted to know what adoption as an alternative to abortion looked like. Her interviews with mothers who surrendered their children make it clear that a post-Roe world must not be a return to pre-Roe norms. Many mothers wanted to raise their children, but they were coerced into adoption because no one was willing to support them as mothers. The partings were traumatic and created lasting wounds where there should have been families.

And most of all, I would want people to read What It Means to Be Human , by O. Carter Snead. Snead’s book on law and bioethics explores how we respond to vulnerability and dependence. It covers abortion extensively but not exclusively. Snead writes about how the logic of abortion is seeded throughout our culture, which is quick to write off the humanity of anyone in need.

When the final Dobbs ruling comes out, our conversations will be better if they are an image of hope, even when we are angry or afraid.

Each of these three books exposes what must change in tandem with abortion law to create a humane culture.

I run Other Feminisms, a Substack newsletter that aims to foster a culture that values mutual dependence instead of demanding autonomy. In the wake of the leak of the possible Dobbs opinion, I asked my readers, who span the gamut from pro-choice to pro-life, what they would ask people to read to begin a conversation .

Their suggestions were marked by the tenderness and precarity that had drawn me to Levy and Jamison. People’s biggest fear is that there is not enough care to go around. Pregnancy makes babies dependent on their mothers and mothers dependent on everyone around them. A culture that takes autonomy as the norm will neglect both mother and child. Thus, it can feel like any care for a child comes at the mother’s expense since we do not trust each other or our policymakers to respond justly to her need.

At the gathering in my living room, I do not think anyone’s mind was changed on the spot, but there were some surprising moments. Some pro-lifers were surprised by how willing pro-choice friends were to consider that a child in the womb had some moral claims, even if they did not see a way to honor them without harming women. Another moment that stuck with me was when one pro-choice attendee explained he had become a vegan a few years ago because he had concluded, “If it looks like suffering, I should err on the side of assuming it is suffering.”

He knew what the pro-life rejoinder was going to be, and the tension of being so tender with a chicken or a fish but not a fetus worried him, too. But he felt stuck. He saw suffering all around, and it felt more possible to give up meat than to give up abortion, which he considered a backstop. He had found room for a little mercy for animals, but he had trouble imagining there was enough to go around for all humans.

When the final Dobbs ruling comes out, our conversations will be better if they are an image of hope, even when we are angry or afraid. Moving a conversation from online to off-line, from public venue to private, from a large group to an intimate one—all of these make it easier to ask and answer questions honestly. Ask yourself: If I were complicit in a grave, widespread evil, what would I need to be able to recognize that, repent and avoid despair? Try to give your friends the welcome and patience you would require in order to so profoundly change your life.

Leah Libresco Sargeant is the author of Building the Benedict Option , and she runs the Substack newsletter Other Feminisms . She will be helping Braver Angels host a debate on abortion on May 19th .

Most popular

Your source for jobs, books, retreats, and much more.

The latest from america

Things you buy through our links may earn Vox Media a commission.

Everything You Need to Know About the Abortion Debate

During the 49 years since the U.S. Supreme Court legalized abortion , the issue has run hot and cold in the political realm, sometimes dominating the national conversation and at other times simmering in the background as conservatives chipped away at reproductive rights and laid the groundwork for the repeal of Roe v. Wade . Now, with the leak of a draft Supreme Court majority opinion that would do just that, the issue has exploded. Pro-choice Americans are bracing for the loss of reproductive rights, and the anti-abortion movement is preparing to celebrate its long-awaited victory — and set its next targets .

If you are new to abortion politics , jumping into the decades-old debate can be overwhelming. Here are the key terms and fault lines you’ll need to know.

What was the legal standard set by Roe v. Wade?

The 1973 Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade (along with the lesser-known companion case Doe v. Bolton ) codified nationally a woman’s right to have an abortion under certain circumstances. The majority opinion, written by Nixon appointee Harry Blackmun with six other justices concurring, found the right to an abortion is an implied constitutional protection of privacy. It held that women had an absolute right to a first-trimester abortion (up to 14 weeks). In the second trimester (14–27 weeks), the government could impose medical regulations, strictly to protect the woman’s health. Then in the third trimester, abortions could be banned outright, reflecting the state’s interest in protecting the “potential life” of the fetus — but exceptions for physician-defined threats to the life or health of the woman had to be allowed.

The decision swept away state bans on most abortions in 33 states, while liberalizing abortion laws in 13 other states. It is annually commemorated on January 22 by both pro-choice and anti-abortion organizations. (Most notably, the March for Life in D.C. has taken place on this date every year since 1974.)

What is fetal viability?

Fetal viability is the point in the development of the human fetus when it has the capacity to survive outside the womb. The medical rule of thumb (which many states and courts follow) is that viability occurs at the earliest at about 24 weeks of pregnancy. Less than one percent of abortions occur after fetal viability, which is why the anti-abortion movement has been determined to shift the line back to earlier stages of pregnancy.

In all the Supreme Court precedents on abortion, women have a very clear right to an abortion prior to viability, subject to limited regulations. However, in 2021 the Court refused a petition to put a hold Texas law that bans on abortions performed after 6 weeks of pregnancy, which blatantly ignores this precedent. Idaho and Oklahoma passed copycat laws in 2022.

How did Planned Parenthood v. Casey change the legal standard set by Roe v. Wade ?

The currently prevailing Supreme Court precedent was set in 1992 by Planned Parenthood v. Casey , a 5-4 decision that both reaffirmed and modified Roe v. Wade . Authored jointly by three Republican-appointed justices (Anthony Kennedy, Sandra Day O’Connor, and David Souter), with two other Republican-appointed justices concurring (Harry Blackmun and John Paul Stevens), Casey scrapped the trimester system, replacing it with a simple right to pre-viability abortions. However, Casey also allowed states to regulate abortions that occurred pre-viability, as long as those regulations did not “unduly burden” a woman’s right to an abortion. ( Roe had barred all government interference in the first trimester.)

Reproductive rights advocates feared the very subjective “undue burden” standard would create a big opening for abortion restrictions, but at the time, most were relieved that the Court had not, as many expected, simply reversed Roe . For the same reason, it was perceived as a bitter defeat for anti-abortion advocates, although it opened up new avenues for abortion restrictions much earlier in pregnancy.

What is fetal personhood?

Many, and perhaps most, anti-abortion activists embrace the idea that from the moment of conception (or fertilization) the fetus is morally and metaphysically a “person” who deserves full citizenship rights that should be constitutionally protected. In other words, while the anti-abortion movement’s immediate goal is reversal of Roe v. Wade and a state-controlled landscape of abortion laws, it generally favors a national law (or constitutional amendment) entrenching fetal rights. A Human Life Amendment to the Constitution has been endorsed in national Republican platforms dating back to 1980.

A state-based “personhood movement” has aimed to enshrine fetal rights in state constitutions, leading to unsuccessful ballot initiatives in Colorado, Mississippi, and North Dakota, and a successful (if vaguer) initiative in Alabama . The “personhood movement” tends to take particularly extreme positions on fetal and embryonic life, often opposing IV-fertilization practices that lead to the destruction of unused embryos, along with birth control methods (e.g., IUDs and morning-after pills) it regards as abortifacient rather than contraceptive. Significantly, the “sanctuary city for the unborn” movement in Texas, which led to the state’s abortion ban, often sought local ordinances banning the sale of morning-after pills and all abortions.

What are pain-capable abortion bans?

One type of state law (and congressional proposal ) has aimed to chip away at abortion rights by shifting the dividing line between legal and potentially illegal abortions from fetal viability to some earlier point in pregnancy — most popularly a scientifically unsubstantiated point at which a fetus is alleged to be capable of experiencing pain (typically 20 or 22 weeks into pregnancy).

Why are some states banning abortion when a heartbeat can be detected?

The most popular current model for state abortion bans is an even more dubious proposition: prohibiting abortion when, in theory, a fetal heartbeat can be detected. (Though cardiac activity — or pulsing cells — can be detected via ultrasound as early as six weeks, this term is misleading because embryos don’t have hearts.) Typically these “heartbeat bills” ban abortion after six weeks of pregnancy, which is before many women know they are pregnant. Like the fetal-pain bans, these laws are intended to supply agitprop to the anti-abortion cause, and provide a suggested new standard for future abortion restrictions. So far eleven states have enacted “heartbeat” laws.

Why do many abortion bans include exceptions for rape and incest?

Within the anti-abortion movement, there is a perpetually raging debate over whether it’s immoral to accept exceptions to proposed abortion bans for pregnancies resulting from rape and incest. Such exceptions are extremely popular, and Republican politicians (including Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump) tend to support them. There’s so much talk about these exceptions in conservative circles that those who embrace them have been able to cultivate a “moderate” image despite supporting bans on the estimated 98.5 percent of abortions that do not involve rape or incest.

Several recently passed state laws – including the Texas 6-week ban that the Supreme Court allowed to take effect, and the Mississippi 15-week ban at issue in Dobbs – have no rape or incest exceptions .

What are TRAP laws?

Largely frustrated in their efforts to directly ban or restrict abortions after Casey , Republican-controlled states increasingly focused their efforts on making abortion services unavailable. The idea behind TRAP (Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers) laws was to devise ostensibly reasonable-sounding requirements, usually rationalized as being for the benefit of the women involved, that had the effect of shutting down abortion clinics. As the Guttmacher Institute explains :