How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

Premedical programs: what to know.

Sarah Wood May 21, 2024

How Geography Affects College Admissions

Cole Claybourn May 21, 2024

Q&A: College Alumni Engagement

LaMont Jones, Jr. May 20, 2024

10 Destination West Coast College Towns

Cole Claybourn May 16, 2024

Scholarships for Lesser-Known Sports

Sarah Wood May 15, 2024

Should Students Submit Test Scores?

Sarah Wood May 13, 2024

Poll: Antisemitism a Problem on Campus

Lauren Camera May 13, 2024

Federal vs. Private Parent Student Loans

Erika Giovanetti May 9, 2024

14 Colleges With Great Food Options

Sarah Wood May 8, 2024

Colleges With Religious Affiliations

Anayat Durrani May 8, 2024

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Footnote leads to exploration of start of for-profit prisons in N.Y.

Should NATO step up role in Russia-Ukraine war?

It’s on Facebook, and it’s complicated

Rubén Rodriguez/Unsplash

Time to fix American education with race-for-space resolve

Harvard Staff Writer

Paul Reville says COVID-19 school closures have turned a spotlight on inequities and other shortcomings

This is part of our Coronavirus Update series in which Harvard specialists in epidemiology, infectious disease, economics, politics, and other disciplines offer insights into what the latest developments in the COVID-19 outbreak may bring.

As former secretary of education for Massachusetts, Paul Reville is keenly aware of the financial and resource disparities between districts, schools, and individual students. The school closings due to coronavirus concerns have turned a spotlight on those problems and how they contribute to educational and income inequality in the nation. The Gazette talked to Reville, the Francis Keppel Professor of Practice of Educational Policy and Administration at Harvard Graduate School of Education , about the effects of the pandemic on schools and how the experience may inspire an overhaul of the American education system.

Paul Reville

GAZETTE: Schools around the country have closed due to the coronavirus pandemic. Do these massive school closures have any precedent in the history of the United States?

REVILLE: We’ve certainly had school closures in particular jurisdictions after a natural disaster, like in New Orleans after the hurricane. But on this scale? No, certainly not in my lifetime. There were substantial closings in many places during the 1918 Spanish Flu, some as long as four months, but not as widespread as those we’re seeing today. We’re in uncharted territory.

GAZETTE: What lessons did school districts around the country learn from school closures in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, and other similar school closings?

REVILLE: I think the lessons we’ve learned are that it’s good [for school districts] to have a backup system, if they can afford it. I was talking recently with folks in a district in New Hampshire where, because of all the snow days they have in the wintertime, they had already developed a backup online learning system. That made the transition, in this period of school closure, a relatively easy one for them to undertake. They moved seamlessly to online instruction.

Most of our big systems don’t have this sort of backup. Now, however, we’re not only going to have to construct a backup to get through this crisis, but we’re going to have to develop new, permanent systems, redesigned to meet the needs which have been so glaringly exposed in this crisis. For example, we have always had large gaps in students’ learning opportunities after school, weekends, and in the summer. Disadvantaged students suffer the consequences of those gaps more than affluent children, who typically have lots of opportunities to fill in those gaps. I’m hoping that we can learn some things through this crisis about online delivery of not only instruction, but an array of opportunities for learning and support. In this way, we can make the most of the crisis to help redesign better systems of education and child development.

GAZETTE: Is that one of the silver linings of this public health crisis?

REVILLE: In politics we say, “Never lose the opportunity of a crisis.” And in this situation, we don’t simply want to frantically struggle to restore the status quo because the status quo wasn’t operating at an effective level and certainly wasn’t serving all of our children fairly. There are things we can learn in the messiness of adapting through this crisis, which has revealed profound disparities in children’s access to support and opportunities. We should be asking: How do we make our school, education, and child-development systems more individually responsive to the needs of our students? Why not construct a system that meets children where they are and gives them what they need inside and outside of school in order to be successful? Let’s take this opportunity to end the “one size fits all” factory model of education.

GAZETTE: How seriously are students going to be set back by not having formal instruction for at least two months, if not more?

“The best that can come of this is a new paradigm shift in terms of the way in which we look at education, because children’s well-being and success depend on more than just schooling,” Paul Reville said of the current situation. “We need to look holistically, at the entirety of children’s lives.”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

REVILLE: The first thing to consider is that it’s going to be a variable effect. We tend to regard our school systems uniformly, but actually schools are widely different in their operations and impact on children, just as our students themselves are very different from one another. Children come from very different backgrounds and have very different resources, opportunities, and support outside of school. Now that their entire learning lives, as well as their actual physical lives, are outside of school, those differences and disparities come into vivid view. Some students will be fine during this crisis because they’ll have high-quality learning opportunities, whether it’s formal schooling or informal homeschooling of some kind coupled with various enrichment opportunities. Conversely, other students won’t have access to anything of quality, and as a result will be at an enormous disadvantage. Generally speaking, the most economically challenged in our society will be the most vulnerable in this crisis, and the most advantaged are most likely to survive it without losing too much ground.

GAZETTE: Schools in Massachusetts are closed until May 4. Some people are saying they should remain closed through the end of the school year. What’s your take on this?

REVILLE: That should be a medically based judgment call that will be best made several weeks from now. If there’s evidence to suggest that students and teachers can safely return to school, then I’d say by all means. However, that seems unlikely.

GAZETTE: The digital divide between students has become apparent as schools have increasingly turned to online instruction. What can school systems do to address that gap?

REVILLE: Arguably, this is something that schools should have been doing a long time ago, opening up the whole frontier of out-of-school learning by virtue of making sure that all students have access to the technology and the internet they need in order to be connected in out-of-school hours. Students in certain school districts don’t have those affordances right now because often the school districts don’t have the budget to do this, but federal, state, and local taxpayers are starting to see the imperative for coming together to meet this need.

Twenty-first century learning absolutely requires technology and internet. We can’t leave this to chance or the accident of birth. All of our children should have the technology they need to learn outside of school. Some communities can take it for granted that their children will have such tools. Others who have been unable to afford to level the playing field are now finding ways to step up. Boston, for example, has bought 20,000 Chromebooks and is creating hotspots around the city where children and families can go to get internet access. That’s a great start but, in the long run, I think we can do better than that. At the same time, many communities still need help just to do what Boston has done for its students.

Communities and school districts are going to have to adapt to get students on a level playing field. Otherwise, many students will continue to be at a huge disadvantage. We can see this playing out now as our lower-income and more heterogeneous school districts struggle over whether to proceed with online instruction when not everyone can access it. Shutting down should not be an option. We have to find some middle ground, and that means the state and local school districts are going to have to act urgently and nimbly to fill in the gaps in technology and internet access.

GAZETTE : What can parents can do to help with the homeschooling of their children in the current crisis?

“In this situation, we don’t simply want to frantically struggle to restore the status quo because the status quo wasn’t operating at an effective level and certainly wasn’t serving all of our children fairly.”

More like this

The collective effort

Notes from the new normal

‘If you remain mostly upright, you are doing it well enough’

REVILLE: School districts can be helpful by giving parents guidance about how to constructively use this time. The default in our education system is now homeschooling. Virtually all parents are doing some form of homeschooling, whether they want to or not. And the question is: What resources, support, or capacity do they have to do homeschooling effectively? A lot of parents are struggling with that.

And again, we have widely variable capacity in our families and school systems. Some families have parents home all day, while other parents have to go to work. Some school systems are doing online classes all day long, and the students are fully engaged and have lots of homework, and the parents don’t need to do much. In other cases, there is virtually nothing going on at the school level, and everything falls to the parents. In the meantime, lots of organizations are springing up, offering different kinds of resources such as handbooks and curriculum outlines, while many school systems are coming up with guidance documents to help parents create a positive learning environment in their homes by engaging children in challenging activities so they keep learning.

There are lots of creative things that can be done at home. But the challenge, of course, for parents is that they are contending with working from home, and in other cases, having to leave home to do their jobs. We have to be aware that families are facing myriad challenges right now. If we’re not careful, we risk overloading families. We have to strike a balance between what children need and what families can do, and how you maintain some kind of work-life balance in the home environment. Finally, we must recognize the equity issues in the forced overreliance on homeschooling so that we avoid further disadvantaging the already disadvantaged.

GAZETTE: What has been the biggest surprise for you thus far?

REVILLE: One that’s most striking to me is that because schools are closed, parents and the general public have become more aware than at any time in my memory of the inequities in children’s lives outside of school. Suddenly we see front-page coverage about food deficits, inadequate access to health and mental health, problems with housing stability, and access to educational technology and internet. Those of us in education know these problems have existed forever. What has happened is like a giant tidal wave that came and sucked the water off the ocean floor, revealing all these uncomfortable realities that had been beneath the water from time immemorial. This newfound public awareness of pervasive inequities, I hope, will create a sense of urgency in the public domain. We need to correct for these inequities in order for education to realize its ambitious goals. We need to redesign our systems of child development and education. The most obvious place to start for schools is working on equitable access to educational technology as a way to close the digital-learning gap.

GAZETTE: You’ve talked about some concrete changes that should be considered to level the playing field. But should we be thinking broadly about education in some new way?

REVILLE: The best that can come of this is a new paradigm shift in terms of the way in which we look at education, because children’s well-being and success depend on more than just schooling. We need to look holistically, at the entirety of children’s lives. In order for children to come to school ready to learn, they need a wide array of essential supports and opportunities outside of school. And we haven’t done a very good job of providing these. These education prerequisites go far beyond the purview of school systems, but rather are the responsibility of communities and society at large. In order to learn, children need equal access to health care, food, clean water, stable housing, and out-of-school enrichment opportunities, to name just a few preconditions. We have to reconceptualize the whole job of child development and education, and construct systems that meet children where they are and give them what they need, both inside and outside of school, in order for all of them to have a genuine opportunity to be successful.

Within this coronavirus crisis there is an opportunity to reshape American education. The only precedent in our field was when the Sputnik went up in 1957, and suddenly, Americans became very worried that their educational system wasn’t competitive with that of the Soviet Union. We felt vulnerable, like our defenses were down, like a nation at risk. And we decided to dramatically boost the involvement of the federal government in schooling and to increase and improve our scientific curriculum. We decided to look at education as an important factor in human capital development in this country. Again, in 1983, the report “Nation at Risk” warned of a similar risk: Our education system wasn’t up to the demands of a high-skills/high-knowledge economy.

We tried with our education reforms to build a 21st-century education system, but the results of that movement have been modest. We are still a nation at risk. We need another paradigm shift, where we look at our goals and aspirations for education, which are summed up in phrases like “No Child Left Behind,” “Every Student Succeeds,” and “All Means All,” and figure out how to build a system that has the capacity to deliver on that promise of equity and excellence in education for all of our students, and all means all. We’ve got that opportunity now. I hope we don’t fail to take advantage of it in a misguided rush to restore the status quo.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

Share this article

You might like.

Historian traces 19th-century murder case that brought together historical figures, helped shape American thinking on race, violence, incarceration

National security analysts outline stakes ahead of July summit

‘Spermworld’ documentary examines motivations of prospective parents, volunteer donors who connect through private group page

Everything counts!

New study finds step-count and time are equally valid in reducing health risks

Five alumni elected to the Board of Overseers

Six others join Alumni Association board

Glimpse of next-generation internet

Physicists demo first metro-area quantum computer network in Boston

COVID-19 and education: The lingering effects of unfinished learning

As this most disrupted of school years draws to a close, it is time to take stock of the impact of the pandemic on student learning and well-being. Although the 2020–21 academic year ended on a high note—with rising vaccination rates, outdoor in-person graduations, and access to at least some in-person learning for 98 percent of students—it was as a whole perhaps one of the most challenging for educators and students in our nation’s history. 1 “Burbio’s K-12 school opening tracker,” Burbio, accessed May 31, 2021, cai.burbio.com. By the end of the school year, only 2 percent of students were in virtual-only districts. Many students, however, chose to keep learning virtually in districts that were offering hybrid or fully in-person learning.

Our analysis shows that the impact of the pandemic on K–12 student learning was significant, leaving students on average five months behind in mathematics and four months behind in reading by the end of the school year. The pandemic widened preexisting opportunity and achievement gaps, hitting historically disadvantaged students hardest. In math, students in majority Black schools ended the year with six months of unfinished learning, students in low-income schools with seven. High schoolers have become more likely to drop out of school, and high school seniors, especially those from low-income families, are less likely to go on to postsecondary education. And the crisis had an impact on not just academics but also the broader health and well-being of students, with more than 35 percent of parents very or extremely concerned about their children’s mental health.

The fallout from the pandemic threatens to depress this generation’s prospects and constrict their opportunities far into adulthood. The ripple effects may undermine their chances of attending college and ultimately finding a fulfilling job that enables them to support a family. Our analysis suggests that, unless steps are taken to address unfinished learning, today’s students may earn $49,000 to $61,000 less over their lifetime owing to the impact of the pandemic on their schooling. The impact on the US economy could amount to $128 billion to $188 billion every year as this cohort enters the workforce.

Federal funds are in place to help states and districts respond, though funding is only part of the answer. The deep-rooted challenges in our school systems predate the pandemic and have resisted many reform efforts. States and districts have a critical role to play in marshaling that funding into sustainable programs that improve student outcomes. They can ensure rigorous implementation of evidence-based initiatives, while also piloting and tracking the impact of innovative new approaches. Although it is too early to fully assess the effectiveness of postpandemic solutions to unfinished learning, the scope of action is already clear. The immediate imperative is to not only reopen schools and recover unfinished learning but also reimagine education systems for the long term. Across all of these priorities it will be critical to take a holistic approach, listening to students and parents and designing programs that meet academic and nonacademic needs alike.

What have we learned about unfinished learning?

As the 2020–21 school year began, just 40 percent of K–12 students were in districts that offered any in-person instruction. By the end of the year, more than 98 percent of students had access to some form of in-person learning, from the traditional five days a week to hybrid models. In the interim, districts oscillated among virtual, hybrid, and in-person learning as they balanced the need to keep students and staff safe with the need to provide an effective learning environment. Students faced multiple schedule changes, were assigned new teachers midyear, and struggled with glitchy internet connections and Zoom fatigue. This was a uniquely challenging year for teachers and students, and it is no surprise that it has left its mark—on student learning, and on student well-being.

As we analyze the cost of the pandemic, we use the term “unfinished learning” to capture the reality that students were not given the opportunity this year to complete all the learning they would have completed in a typical year. Some students who have disengaged from school altogether may have slipped backward, losing knowledge or skills they once had. The majority simply learned less than they would have in a typical year, but this is nonetheless important. Students who move on to the next grade unprepared are missing key building blocks of knowledge that are necessary for success, while students who repeat a year are much less likely to complete high school and move on to college. And it’s not just academic knowledge these students may miss out on. They are at risk of finishing school without the skills, behaviors, and mindsets to succeed in college or in the workforce. An accurate assessment of the depth and extent of unfinished learning will best enable districts and states to support students in catching up on the learning they missed and moving past the pandemic and into a successful future.

Students testing in 2021 were about ten points behind in math and nine points behind in reading, compared with matched students in previous years.

Unfinished learning is real—and inequitable

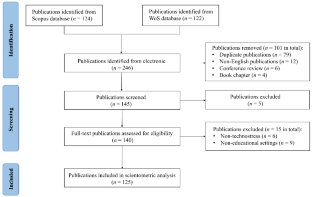

To assess student learning through the pandemic, we analyzed Curriculum Associates’ i-Ready in-school assessment results of more than 1.6 million elementary school students across more than 40 states. 2 The Curriculum Associates in-school sample consisted of 1.6 million K–6 students in mathematics and 1.5 million in reading. The math sample came from all 50 states, but 23 states accounted for 90 percent of the sample. The reading sample came from 46 states, with 21 states accounting for 90 percent of the sample. Florida accounted for 29 percent of the math and 30 percent of the reading sample. In general, states that had reopened schools are overweighted given the in-school nature of the assessment. We compared students’ performance in the spring of 2021 with the performance of similar students prior to the pandemic. 3 Specifically, we compared spring 2021 results to those of historically matched students in the springs of 2019, 2018, and 2017. Students testing in 2021 were about ten points behind in math and nine points behind in reading, compared with matched students in previous years.

To get a sense of the magnitude of these gaps, we translated these differences in scores to a more intuitive measure—months of learning. Although there is no perfect way to make this translation, we can get a sense of how far students are behind by comparing the levels students attained this spring with the growth in learning that usually occurs from one grade level to the next. We found that this cohort of students is five months behind in math and four months behind in reading, compared with where we would expect them to be based on historical data. 4 The conversion into months of learning compares students’ achievement in the spring of one grade level with their performance in the spring of the next grade level, treating this spring-to-spring difference in historical scores as a “year” of learning. It assumes a ten-month school year with a two-month summer vacation. Actual school schedules vary significantly, and i-Ready’s typical growth numbers for a “year” of learning are based on 30 weeks of actual instruction between the fall and the spring rather than on a spring-to-spring calendar-year comparison.

Unfinished learning did not vary significantly across elementary grades. Despite reports that remote learning was more challenging for early elementary students, 5 Marva Hinton, “Why teaching kindergarten online is so very, very hard,” Edutopia, October 21, 2020, edutopia.org. our results suggest the impact was just as meaningful for older elementary students. 6 While our analysis only includes results from students who tested in-school in the spring, many of these students were learning remotely for meaningful portions of the fall and the winter. We can hypothesize that perhaps younger elementary students received more help from parents and older siblings, and that older elementary students were more likely to be struggling alone.

It is also worth remembering that our numbers capture the “average” progress by grade level. Especially in early reading, this average can conceal a wide range of outcomes. Another way of cutting the data looks instead at which students have dropped further behind grade levels. A recent report suggests that more first and second graders have ended this year two or more grade levels below expectations than in any previous year. 7 Academic achievement at the end of the 2020–2021 school year , Curriculum Associates, June 2021, curriculumassociates.com. Given the major strides children at this age typically make in mastering reading, and the critical importance of early reading for later academic success, this is of particular concern.

While all types of students experienced unfinished learning, some groups were disproportionately affected. Students of color and low-income students suffered most. Students in majority-Black schools ended the school year six months behind in both math and reading, while students in majority-white schools ended up just four months behind in math and three months behind in reading. 8 To respect students’ privacy, we cannot isolate the race or income of individual students in our sample, but we can look at school-level demographics. Students in predominantly low-income schools and in urban locations also lost more learning during the pandemic than their peers in high-income rural and suburban schools (Exhibit 1).

In fall 2020, we projected that students could lose as much as five to ten months of learning in mathematics, and about half of that in reading, by the end of the school year. Spring assessment results came in toward the lower end of these projections, suggesting that districts and states were able to improve the quality of remote and hybrid learning through the 2020–21 school year and bring more students back into classrooms.

Indeed, if we look at the data over time, some interesting patterns emerge. 9 The composition of the fall student sample was different from that of the spring sample, because more students returned to in-person assessments in the spring. Some of the increase in unfinished learning from fall to spring could be because the spring assessment included previously virtual students, who may have struggled more during the school year. Even so, the spring data are the best reflection of unfinished learning at the end of the school year. Taking math as an example, as schools closed their buildings in the spring of 2020, students fell behind rapidly, learning almost no new math content over the final few months of the 2019–20 school year. Over the summer, we assume that they experienced the typical “summer slide” in which students lose some of the academic knowledge and skills they had learned the year before. Then they resumed learning through the 2020–21 school year, but at a slower pace than usual, resulting in five months of unfinished learning by the end of the year (Exhibit 2). 10 These lines simplify the pattern of typical learning through the year. In a typical year, students learn more in the fall and less in the spring, and only learn during periods of instruction (the chart includes the well-documented learning loss that happens during the summer, but does not include shorter holidays when students are not in school receiving instruction).

In reading, however, the story is somewhat different. As schools closed their buildings in March 2020, students continued to progress in reading, albeit at a slower pace. During the summer, we assume that students’ reading level stayed roughly flat, as in previous years. The pace of learning increased slightly over the 2020–21 school year, but the difference was not as great as it was in math, resulting in four months of unfinished learning by the end of the school year (Exhibit 3). Put another way, the initial shock in reading was less severe, but the improvements to remote and hybrid learning seem to have had less impact in reading than they did in math.

Before we celebrate the improvements in student trajectories between the initial school shutdowns and the subsequent year of learning, we should remember that these are still sobering numbers. On average, students who took the spring assessments in school are half a year behind in math, and nearly that in reading. For Black and Hispanic students, the losses are not only greater but also piled on top of historical inequities in opportunity and achievement (Exhibit 4).

Furthermore, these results likely represent an optimistic scenario. They reflect outcomes for students who took interim assessments in the spring in a school building 11 Students who took the assessment out of school are not included in our sample because we could not guarantee fidelity and comparability of results, given the change in the testing environment. Out-of-school students represent about a third of the students taking i-Ready assessments in the spring, and we will not have an accurate understanding of the pandemic’s impact on their learning until they return to school buildings, likely in the fall. —and thus exclude students who remained remote throughout the entire school year, and who may have experienced the most disruption to their schooling. 12 Initial results from Texas suggest that districts with mostly virtual instruction experienced more unfinished learning than those with mostly in-person instruction. The percent of students meeting math expectations dropped 32 percent in mostly virtual districts but just 9 percent in mostly in-person ones. See Reese Oxner, “Texas students’ standardized test scores dropped dramatically during the pandemic, especially in math,” Texas Tribune , June 28, 2021, texastribune.org. The Curriculum Associates data cover a broad variety of schools and states across the country, but are not fully representative, being overweighted for rural and southeastern states that were more likely to get students back into the classrooms this year. Finally, these data cover only elementary schools. They are silent on the academic impact of the pandemic for middle and high schoolers. However, data from school districts suggest that, even for older students, the pandemic has had a significant effect on learning. 13 For example, in Salt Lake City, the percentage of middle and high school students failing a class jumped by 60 percent, from 2,500 to 4,000, during the pandemic. To learn about increased failure rates across multiple districts from the Bay Area to New Mexico, Austin, and Hawaii, see Richard Fulton, “Failing Grades,” Inside Higher Ed , March 8, 2021, insidehighered.com.

The harm inflicted by the pandemic goes beyond academics

Students didn’t just lose academic learning during the pandemic. Some lost family members; others had caregivers who lost their jobs and sources of income; and almost all experienced social isolation.

These pressures have taken a toll on students of all ages. In our recent survey of 16,370 parents across every state in America, 35 percent of parents said they were very or extremely concerned about their child’s mental health, with a similar proportion worried about their child’s social and emotional well-being. Roughly 80 percent of parents had some level of concern about their child’s mental health or social and emotional health and development since the pandemic began. Parental concerns about mental health span grade levels but are slightly lower for parents of early elementary school students. 14 While 30.7% percent of all K–2 parents were very or extremely concerned, a peak of 37.6% percent of eighth-grade parents were.

Parents also report increases in clinical mental health conditions among their children, with a five-percentage-point increase in anxiety and a six-percentage-point increase in depression. They also report increases in behaviors such as social withdrawal, self-isolation, lethargy, and irrational fears (Exhibit 5). Despite increased levels of concern among parents, the amount of mental health assessment and testing done for children is 6.1 percent lower than it was in 2019 —the steepest decline in assessment and testing rates of any age group.

Broader student well-being is not independent of academics. Parents whose children have fallen significantly behind academically are one-third more likely to say that they are very or extremely concerned about their children’s mental health. Black and Hispanic parents are seven to nine percentage points more likely than white parents to report higher levels of concern. Unaddressed mental-health challenges will likely have a knock-on effect on academics going forward as well. Research shows that trauma and other mental-health issues can influence children’s attendance, their ability to complete schoolwork in and out of class, and even the way they learn. 15 Satu Larson et al., “Chronic childhood trauma, mental health, academic achievement, and school-based health center mental health services,” Journal of School Health , 2017, 87(9), 675–86, escholarship.org.

In our recent survey of 16,370 parents across every state in America, 35 percent of parents said they were very or extremely concerned about their child’s mental health.

The impact of unfinished learning on diminished student well-being seems to be playing out in the choices that students are making. Some students have already effectively dropped out of formal education entirely. 16 To assess the impact of the pandemic on dropout rates, we have to look beyond official enrollment data, which are only published annually, and which only capture whether a child has enrolled at the beginning of the year, not whether they are engaged and attending school. Chronic absenteeism rates provide clues as to which students are likely to persist in school and which students are at risk of dropping out. Our parent survey suggests that chronic absenteeism for eighth through 12th graders has increased by 12 percentage points, and 42 percent of the students who are new to chronic absenteeism are attending no school at all, according to their parents. Scaled up to the national level, this suggests that 2.3 million to 4.6 million additional eighth- to 12th-grade students were chronically absent from school this year, in addition to the 3.1 million who are chronically absent in nonpandemic years. State and district data on chronic absenteeism are still emerging, but data released so far also suggest a sharp uptick in absenteeism rates nationwide, particularly in higher grades. 17 A review of available state and district data, including data released by 14 states and 11 districts, showed increases in chronic absenteeism of between three and 16 percentage points, with an average of seven percentage points. However, many states changed the definition of absenteeism during the pandemic, so a true like-for-like comparison is difficult to obtain. According to emerging state and district data, increases in chronic absenteeism are highest among populations with historically low rates. This is reflected also in our survey results. Black students, with the highest historical absenteeism rates, saw more modest increases during the pandemic than white or Hispanic students (Exhibit 6).

It remains unclear whether these pandemic-related chronic absentees will drop out at rates similar to those of students who were chronically absent prior to the pandemic. Some students could choose to return to school once in-person options are restored; but some portion of these newly absent students will likely drop out of school altogether. Based on historical links between chronic absenteeism and dropout rates, as well as differentials in absenteeism between fully virtual and fully in-person students, we estimate that an additional 617,000 to 1.2 million eighth–12th graders could drop out of school altogether because of the pandemic if efforts are not made to reengage them in learning next year. 18 The federal definition of chronic absenteeism is missing more than 15 days of school each year. According to the Utah Education Policy Center’s research brief on chronic absenteeism, the overall correlation between one year of chronic absence between eighth and 12th grade and dropping out of school is 0.134. For more, see Utah Education Policy Center, Research brief: Chronic absenteeism , July 2012, uepc.utah.edu. We then apply the differential in chronic absenteeism between fully virtual and fully in-person students to account for virtual students reengaging when in-person education is offered. For students who were not attending school at all, we assumed that 50 to 75 percent would not return to learning. This estimation is partly based on The on-track indicator as a predictor of high school graduation from the UChicago Consortium on School Research, which estimates that up to 75 percent of high school students who are “off track”—either failing or behind in credits—do not graduate in five years. For more, see Elaine Allensworth and John Q. Easton, The on-track indicator as a predictor of high school graduation , UChicago Consortium on School Research, 2005, consortium.uchicago.edu.

Even among students who complete high school, many may not fulfill their dreams of going on to postsecondary education. Our survey suggests that 17 percent of high school seniors who had planned to attend postsecondary education abandoned their plans—most often because they had joined or were planning to join the workforce or because the costs of college were too high. The number is much higher among low-income high school seniors, with 26 percent abandoning their plans. Low-income seniors are more likely to state cost as a reason, with high-income seniors more likely to be planning to reapply the following year or enroll in a gap-year program. This is consistent with National Student Clearinghouse reports that show overall college enrollment declines, with low-income, high-poverty, and high-minority high schools disproportionately affected. 19 Todd Sedmak, “Fall 2020 college enrollment update for the high school graduating class of 2020,” National Student Clearinghouse, March 25, 2021, studentclearinghouse.org; Todd Sedmak, “Spring 2021 college enrollment declines 603,000 to 16.9 million students,” National Student Clearinghouse, June 10, 2021, studentclearinghouse.org.

Unfinished learning has long-term consequences

The cumulative effects of the pandemic could have a long-term impact on an entire generation of students. Education achievement and attainment are linked not only to higher earnings but also to better health, reduced incarceration rates, and greater political participation. 20 See, for example, Michael Grossman, “Education and nonmarket outcomes,” in Handbook of the Economics of Education, Volume 1 , ed. Eric Hanushek and Finis Welch (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2006), 577–633; Lance Lochner and Enrico Moretti, “The effect of education on crime: Evidence from prison inmates, arrests, and self-reports,” American Economic Review , 2004, Volume 94, Number 1, pp. 155–89; Kevin Milligan, Enrico Moretti, and Philip Oreopoulos, “Does education improve citizenship? Evidence from the United States and the United Kingdom,” Journal of Public Economics , August 2004, Volume 88, Number 9–10, pp. 1667–95; and Education transforms lives , UNESCO, 2013, unesdoc.unesco.org. We estimate that, without immediate and sustained interventions, pandemic-related unfinished learning could reduce lifetime earnings for K–12 students by an average of $49,000 to $61,000. These costs are significant, especially for students who have lost more learning. While white students may see lifetime earnings reduced by 1.4 percent, the reduction could be as much as 2.4 percent for Black students and 2.1 percent for Hispanic students. 21 Projected earnings across children’s lifetimes using current annual incomes for those with at least a high school diploma, discounting the earnings by a premium established in Murnane et al., 2000, which tied cognitive skills and future earnings. See Richard J. Murnane et al., “How important are the cognitive skills of teenagers in predicting subsequent earnings?,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management , September 2000, Volume 19, Number 4, pp. 547–68.

Lower earnings, lower levels of education attainment, less innovation—all of these lead to decreased economic productivity. By 2040 the majority of this cohort of K–12 students will be in the workforce. We anticipate a potential annual GDP loss of $128 billion to $188 billion from pandemic-related unfinished learning. 22 Using Hanushek and Woessmann 2008 methodology to map national per capita growth associated with decrease in academic achievement, then adding additional impact of pandemic dropouts on GDP. For more, see Eric A. Hanushek and Ludger Woessmann, “The role of cognitive skills in economic development,” Journal of Economic Literature , September 2008, Volume 46, Number 3, pp. 607–68.

This increases by about one-third the existing hits to GDP from achievement gaps that predated COVID-19. Our previous research indicated that the pre-COVID-19 racial achievement gap was equivalent to $426 billion to $705 billion in lost economic potential every year (Exhibit 7). 23 This is the increase in GDP that would result if Black and Hispanic students achieved the same levels of academic performance as white students. For more information on historical opportunity and achievement gaps, please see Emma Dorn, Bryan Hancock, Jimmy Sarakatsannis, and Ellen Viruleg, “ COVID-19 and student learning in the United States: The hurt could last a lifetime ,” June 1, 2020.

What is the path forward for our nation’s students?

There is now significant funding in place to address these critical issues. Through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act); the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSAA); and the American Rescue Plan (ARP), the federal government has already committed more than $200 billion to K–12 education over the next three years, 24 The CARES Act provided $13 billion to ESSER and $3 billion to the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief (GEER) Fund; CRRSAA provided $54 billion to ESSER II, $4 billion to Governors (GEER II and EANS); ARP provided $123 billion to ESSER III, $3 billion to Governors (EANS II), and $10 billion to other education programs. For more, see “CCSSO fact sheet: COVID-19 relief funding for K-12 education,” Council of Chief State School Officers, 2021, https://753a0706.flowpaper.com/CCSSOCovidReliefFactSheet/#page=2. a significant increase over the approximately $750 billion spent annually on public schooling. 25 “The condition of education 2021: At a glance,” National Center for Education Statistics, accessed June 30, 2021, nces.ed.gov. The majority of these funds are routed through the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER), of which 90 percent flows to districts and 10 percent to state education agencies. These are vast sums of money, particularly in historical context. As part of the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), the Obama administration committed more than $80 billion toward K–12 schools—at the time the biggest federal infusion of funds to public schools in the nation’s history. 26 “The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009: Saving and Creating Jobs and Reforming Education,” US Department of Education, March 7, 2009, ed.gov. Today’s funding more than doubles that previous record and gives districts much more freedom in how they spend the money. 27 Andrew Ujifusa, “What Obama’s stimulus had for education that the coronavirus package doesn’t,” Education Week , March 31, 2020, www.edweek.org.

However, if this funding can mitigate the impact of unfinished learning, it could prevent much larger losses to the US economy. Given that this generation of students will likely spend 35 to 40 years in the workforce, the cumulative impact of COVID-19 unfinished learning over their lifetimes could far exceed the investments that are being made today.

Furthermore, much of today’s federal infusion will likely be spent not only on supporting students in catching up on the unfinished learning of the pandemic but also on tackling deeper historical opportunity and achievement gaps among students of different races and income levels.

As districts consider competing uses of funding, they are juggling multiple priorities over several time horizons. The ARP funding needs to be obligated by September 2023. This restricts how monies can be spent. Districts are balancing the desire to hire new personnel or start new programs with the risk of having to close programs because of lack of sustained funds in the future. Districts are also facing decisions about whether to run programs at the district level or to give more freedom to principals in allocating funds; about the balance between academics and broader student needs; about the extent to which funds should be targeted to students who have struggled most or spread evenly across all students; and about the balance between rolling out existing evidence-based programs and experimenting with innovative approaches.

It is too early to answer all of these questions decisively. However, as districts consider this complex set of decisions, leading practitioners and thinkers have come together to form the Coalition to Advance Future Student Success—and to outline priorities to ensure the effective and equitable use of federal funds. 28 “Framework: The Coalition to Advance Future Student Success,” Council of Chief State School Officers, accessed June 30, 2021, learning.ccsso.org.

These priorities encompass four potential actions for schools:

- Safely reopen schools for in-person learning.

- Reengage students and reenroll them into effective learning environments.

- Support students in recovering unfinished learning and broader needs.

- Recommit and reimagine our education systems for the long term.

Across all of these actions, it is important for districts to understand the changing needs of parents and students as we emerge from the pandemic, and to engage with them to support students to learn and to thrive. The remainder of this article shares insights from our parent survey of more than 16,000 parents on these changing needs and perspectives, and highlights some early actions by states and districts to adapt to meet them.

1. Safely reopen schools for in-person learning

The majority of school districts across the country are planning to offer traditional five-days-a-week in-person instruction in the fall, employing COVID-19-mitigation strategies such as staff and student vaccination drives, ongoing COVID-19 testing, mask mandates, and infrastructure updates. 29 “Map: Where Were Schools Required to Be Open for the 2020-21 School Year?,” Education Week , updated May 2021, edweek.org. The evidence suggests that schools can reopen buildings safely with the right protocols in place, 30 For a summary of the evidence on safely reopening schools, see John Bailey, Is it safe to reopen schools? , CRPE, March 2021, crpe.org. but health preparedness will likely remain critical as buildings reopen. Indeed, by the end of the school year, a significant subset of parents remain concerned about safety in schools, with nearly a third still very or extremely worried about the threat of COVID-19 to their child’s health. Parents also want districts to continue to invest in safety—39 percent say schools should invest in COVID-19 health and safety measures this fall.

2. Reengage and reenroll students in effective learning environments

Opening buildings safely is hard enough, but encouraging students to show up could be even more challenging. Some students will have dropped out of formal schooling entirely, and those who remain in school may be reluctant to return to physical classrooms. Our survey results suggest that 24 percent of parents are still not convinced they will choose in-person instruction for their children this fall. Within Black communities, that rises to 34 percent. But many of these parents are still open to persuasion. Only 4 percent of parents (and 6 percent of Black parents) say their children will definitely not return to fully in-person learning—which is not very different from the percentage of parents who choose to homeschool or pursue other alternative education options in a typical year. For students who choose to remain virtual, schools should make continual efforts to improve virtual learning models, based on lessons from the past year.

For parents who are still on the fence, school districts can work to understand their needs and provide effective learning options. Safety concerns remain the primary reason that parents remain hesitant about returning to the classroom; however, this is not the only driver. Some parents feel that remote learning has been a better learning environment for their child, while others have seen their child’s social-emotional and mental health improve at home.

Still, while remote learning may have worked well for some students, our data suggest that it failed many. In addition to understanding parent needs, districts should reach out to families and build confidence not just in their schools’ safety precautions but also in their learning environment and broader role in the community. Addressing root causes will likely be more effective than punitive measures, and a broad range of tactics may be needed, from outreach and attendance campaigns to student incentives to providing services families need, such as transportation and childcare. 31 Roshon R. Bradley, “A comprehensive approach to improving student attendance,” St. John Fisher College, August 2015, Education Doctoral, Paper 225, fisherpub.sjfc.edu; a 2011 literature review highlights how incentives can effectively be employed to increase attendance rates. Across all of these, a critical component will likely be identifying students who are at risk and ensuring targeted outreach and interventions. 32 Elaine M. Allensworth and John Q. Easton, “What matters for staying on-track and graduating in Chicago Public Schools: A close look at course grades, failures, and attendance in the freshman year,” Consortium on Chicago School Research at the University of Chicago, July 2007, files.eric.ed.gov.

Chicago Public Schools, in partnership with the University of Chicago, has developed a student prioritization index (SPI) that identifies students at highest risk of unfinished learning and dropping out of school. The index is based on a combination of academic, attendance, socio-emotional, and community vulnerability inputs. The district is reaching out to all students with a back-to-school marketing campaign while targeting more vulnerable students with additional support. Schools are partnering with community-based organizations to carry out home visits, and with parents to staff phone banks. They are offering various paid summer opportunities to reduce the trade-offs students may have to make between summer school and summer jobs, recognizing that many have found paid work during the pandemic. The district will track and monitor the results to learn which tactics work. 33 “Moving Forward Together,” Chicago Public Schools, June 2021, cps.edu.

In Florida’s Miami-Dade schools, each school employee was assigned 30 households to contact personally, starting with a phone call and then showing up for a home visit. Superintendent Alberto Carvalho personally contacted 30 families and persuaded 23 to return to in-person learning. The district is starting the transition to in-person learning by hosting engaging in-person summer learning programs. 34 Hannah Natanson, “Schools use home visits, calls to convince parents to choose in-person classes in fall,” Washington Post , July 7, 2021, washingtonpost.com.

3. Support students in recovering unfinished learning and in broader needs

Even if students reenroll in effective learning environments in the fall, many will be several months behind academically and may struggle to reintegrate into a traditional learning environment. School districts are therefore creating strategies to support students as they work to make up unfinished learning, and as they work through broader mental health issues and social reintegration. Again, getting parents and students to show up for these programs may be harder than districts expect.

Our research suggests that parents underestimate the unfinished learning caused by the pandemic. In addition, their beliefs about their children’s learning do not reflect racial disparities in unfinished learning. In our survey, 40 percent of parents said their child is on track and 16 percent said their child is progressing faster than in a usual year. Black parents are slightly more likely than white parents to think their child is on track or better, Hispanic parents less so. However, across all races, more than half of parents think their child is doing just fine. Only 14 percent of parents said their child has fallen significantly behind.

Even if programs are offered for free, many parents may not take advantage of them, especially if they are too academically oriented. Only about a quarter of parents said they are very likely to enroll their child in tutoring, after-school, or summer-school programs, for example. Nearly 40 percent said they are very likely to enroll their students in enrichment programs such as art or music. Districts therefore should consider not only offering effective evidence-based programs, such as high-dosage tutoring and vacation academies, but also ensuring that these programs are attractive to students.

In Rhode Island, for example, the state is taking a “Broccoli and Ice Cream” approach to summer school to prepare students for the new school year, combining rigorous reading and math instruction with fun activities provided by community-based partners. Enrichment activities such as sailing, Italian cooking lessons, and Olympic sports are persuading students to participate. 35 From webinar with Angélica Infante-Green, Rhode Island Department of Education, https://www.ewa.org/agenda/ewa-74th-national-seminar-agenda. The state-run summer program is open to students across the state, but the Rhode Island Department of Education has also provided guidance to district-run programs, 36 Learning, Equity & Accelerated Pathways Task Force Report , Rhode Island Department of Education, April 2021, ride.ri.gov. encouraging partnerships with community-based organizations, a dual focus on academics and enrichment, small class sizes, and a strong focus on relationships and social-emotional support.

In Louisiana, the state has provided guidance and support 37 Staffing and scheduling best practices guidance , Louisiana Department of Education, June 3, 2021, louisianabelieves.com. to districts in implementing recovery programs to ensure evidence-based approaches are rolled out state-wide. The guidance includes practical tips on ramping up staffing, and on scheduling high-dosage tutoring and other dedicated acceleration blocks. The state didn’t stop at guidance, but also flooded districts with support and two-way dialogue through webinars, conferences, monthly calls, and regional technical coaching. By scheduling acceleration blocks during the school day, rather than an add-on after school, districts are not dependent on parents signing up for programs.

For students who have experienced trauma, schools will likely need to address the broader fallout from the pandemic. In southwest Virginia, the United Way is partnering with five school systems to establish a trauma-informed schools initiative, providing teachers and staff with training and resources on trauma recovery. 38 Mike Still, “SWVA school districts partner to help students in wake of pandemic,” Kingsport Times News, June 26, 2021, timesnews.net. San Antonio is planning to hire more licensed therapists and social workers to help students and their families, leveraging partnerships with community organizations to place a licensed social worker on every campus. 39 Brooke Crum, “SAISD superintendent: ‘There are no shortcuts’ to tackling COVID-related learning gaps,” San Antonio Report, April 12, 2021, sanantonioreport.org.

4. Recommit and reimagine our education systems for the long term

Opportunity gaps have existed in our school systems for a long time. As schools build back from the pandemic, districts are also recommitting to providing an excellent education to every child. A potential starting point could be redoubling efforts to provide engaging, high-quality grade-level curriculum and instruction delivered by diverse and effective educators in every classroom, supported by effective assessments to inform instruction and support.

Beyond these foundational elements, districts may consider reimagining other aspects of the system. Parents may also be open to nontraditional models. Thirty-three percent of parents said that even when the pandemic is over, the ideal fit for their child would be something other than five days a week in a traditional brick-and-mortar school. Parents are considering hybrid models, remote learning, homeschooling, or learning hubs over the long term. Even if learning resumes mostly in the building, parents are open to the use of new technology to support teaching.

Edgecombe County Public Schools in North Carolina is planning to continue its use of learning hubs this fall to better meet student needs. In the district’s hub-and-spoke model, students will spend half of their time learning core content (the “hub”). For the other half they will engage in enrichment activities aligned to learning standards (the “spokes”). For elementary and middle school students, enrichment activities will involve interest-based projects in science and social studies; for high schoolers, activities could include exploring their passions through targeted English language arts and social studies projects or getting work experience—either paid or volunteer. The district is redeploying staff and leveraging community-based partnerships to enable these smaller-group activities with trusted adults who mirror the demographics of the students. 40 “District- and community-driven learning pods,” Center on Reinventing Public Education, crpe.org.

In Tennessee, the new Advanced Placement (AP) Access for All program will provide students across the state with access to AP courses, virtually. The goal is to eliminate financial barriers and help students take AP courses that aren’t currently offered at their home high school. 41 Amy Cockerham, “TN Department of Education announces ‘AP Access for All program,’” April 28, 2021, WJHL-TV, wjhl.com.

The Dallas Independent School District is rethinking the traditional school year, gathering input from families, teachers, and school staff to ensure that school communities are ready for the plunge. More than 40 schools have opted to add five additional intercession weeks to the year to provide targeted academics and enrichment activities. A smaller group of schools will add 23 days to the school year to increase time for student learning and teacher planning and collaboration. 42 “Time to Learn,” Dallas Independent School District, dallasisd.org.

It is unclear whether all these experiments will succeed, and school districts should monitor them closely to ensure they can scale successful programs and sunset unsuccessful ones. However, we have learned in the pandemic that some of the innovations born of necessity met some families’ needs better. Continued experimentation and fine-tuning could bring the best of traditional and new approaches together.

Thanks to concerted efforts by states and districts, the worst projections for learning outcomes this past year have not materialized for most students. However, students are still far behind where they need to be, especially those from historically marginalized groups. Left unchecked, unfinished learning could have severe consequences for students’ opportunities and prospects. In the long term, it could exact a heavy toll on the economy. It is not too late to mitigate these threats, and funding is now in place. Districts and states now have the opportunity to spend that money effectively to support our nation’s students.

Emma Dorn is a senior expert in McKinsey’s Silicon Valley office; Bryan Hancock and Jimmy Sarakatsannis are partners in the Washington, DC, office; and Ellen Viruleg is a senior adviser based in Providence, Rhode Island.

The authors wish to thank Alice Boucher, Ezra Glenn, Ben Hayes, Cheryl Healey, Chauncey Holder, and Sidney Scott for their contributions to this article.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Teacher survey: Learning loss is global—and significant

COVID-19 and learning loss—disparities grow and students need help

Reimagining a more equitable and resilient K–12 education system

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

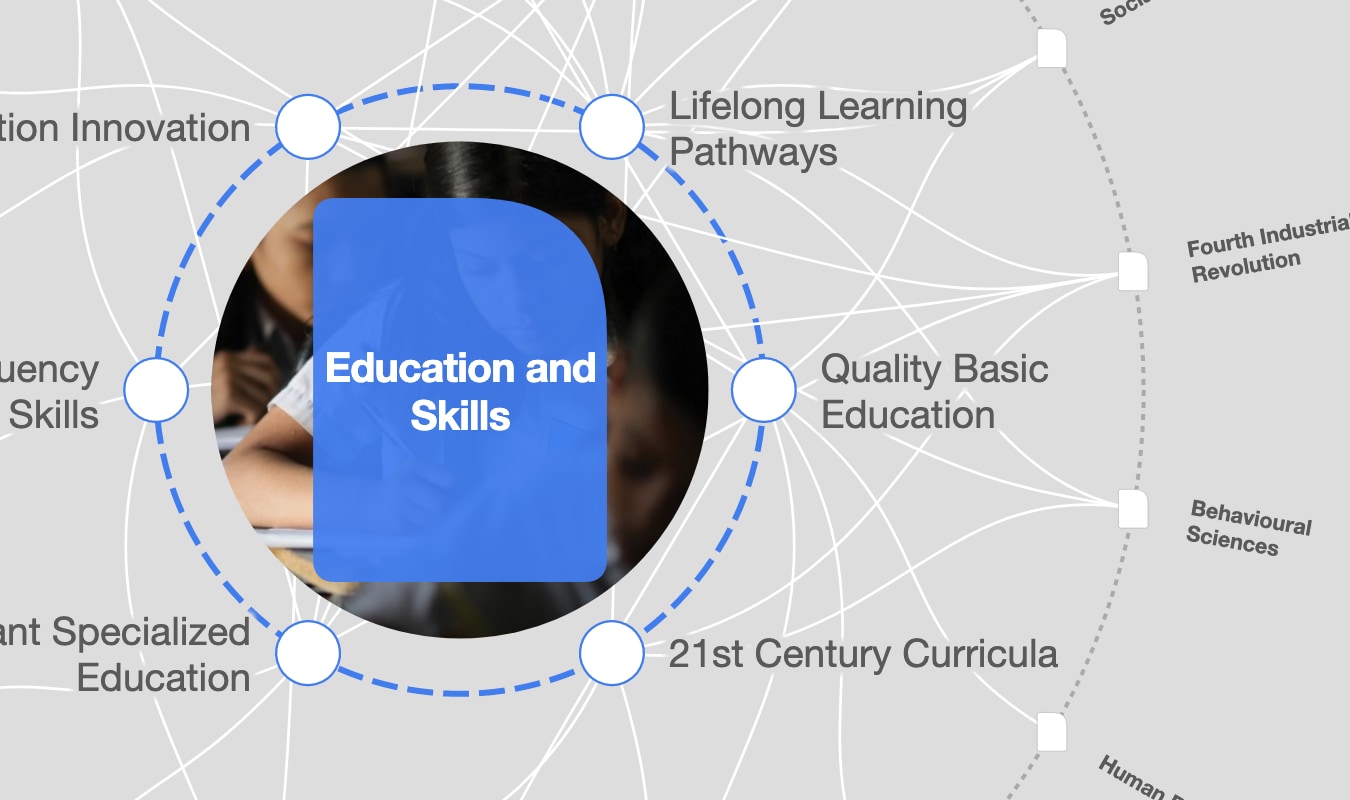

The changes we need: Education post COVID-19

1 Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia

2 School of Education, University of Kansas, 419 JRP, Lawrence, KS 66049 USA

Jim Watterston

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused both unprecendented disruptions and massive changes to education. However, as schools return, these changes may disappear. Moreover, not all of the changes are necessarily the changes we want in education. In this paper, we argue that the pandemic has created a unique opportunity for educational changes that have been proposed before COVID-19 but were never fully realized. We identify three big changes that education should make post COVID: curriculum that is developmental, personalized, and evolving; pedagogy that is student-centered, inquiry-based, authentic, and purposeful; and delivery of instruction that capitalizes on the strengths of both synchronous and asynchronous learning.

Introduction

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on education is both unprecedented and widespread in education history, impacting nearly every student in the world (UNICEF 2020 ; United Nations 2020 ). The unexpected arrival of the pandemic and subsequent school closures saw massive effort to adapt and innovate by educators and education systems around the world. These changes were made very quickly as the prevailing circumstances demanded. Almost overnight, many schools and education systems began to offer education remotely (Kamanetz 2020 ; Sun et al. 2020 ). Through television and radio, the Internet, or traditional postal offices, schools shifted to teach students in very different ways. Regardless of the outcomes, remote learning became the de facto method of education provision for varying periods. Educators proactively responded and showed great support for the shifts in lesson delivery. Thus, it is clear and generally accepted that “this crisis has stimulated innovation within the education sector” (United Nations 2020 , p. 2).

However, the changes or innovations that occurred in the immediate days and weeks when COVID-19 struck are not necessarily the changes education needs to make in the face of massive societal changes in a post-COVID-19 world. By and large, the changes were more about addressing the immediate and urgent need of continuing schooling, teaching online, and finding creative ways to reach students at home rather than using this opportunity to rethink education. While understandable in the short term, these changes will very likely be considered insubstantial for the long term.

The COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to be a once in a generation opportunity for real change a number of reasons. First, the pandemic was global and affected virtually all schools. As such, it provides the opportunity for educators and children to come together to rethink the education we actually need as opposed to the inflexible and outdated model that we are likely to feverishly cling to. Second, educators across the world demonstrated that they could collectively change en masse. The pandemic forced closure of schools, leaving teachers, children and adults to carry out education in entirely different situations. Governments, education systems, and schools offered remote learning and teaching without much preparation, planning, and in some cases, digital experience (Kamanetz 2020 ; Sun et al. 2020 ). Third, when schools were closed, most of the traditional regulations and exams that govern schools were also lifted or minimally implemented. Traditional accountability examinations and many other high stakes tests were cancelled. Education was given the room to rapidly adapt to the prevailing circumstances.

It is our hope that as we transition out of the COVID-19 pandemic and into an uncertain future that we can truly reimagine education. In light of this rare opportunity, we wish to urge scholars, policy makers, and educators to have the courage to make bold changes beyond simply changing instructional delivery. The changes that we advocate in this paper are not new but they never managed to gain traction in the pre-COVID-19 educational landscape. Our most recent experience, however, has exacerbated the need for us to rethink what is necessary, desirable, and even possible for future generations.

Changes we need

It is incumbant upon all educators to use this crisis-driven opportunity to push for significant shifts in almost every aspect of education: what, how, where, who, and when. In other words, education, from curriculum to pedagogy, from teacher to learner, from learning to assessment, and from location to time, can and should radically transform. We draw on our own research and that of our colleagues to suggest what this transformation could look like.

Curriculum: What to teach

It has been widely acknowledged that to thrive in a future globalized world, traditionally valued skills and knowledge will become less important and a new set of capabilities will become more dominant and essential (Barber et al. 2012 ; Florida 2012 ; Pink 2006 ; Wagner 2008 ; Wagner and Dintersmith 2016 ). While the specifics vary, the general agreement is that repetition, pattern-prediction and recognition, memorization, or any skills connected to collecting, storing, and retrieving information are in decline because of AI and related technologies (Muro et al. 2019 ). On the rise is a set of contemporary skills which includes creativity, curiosity, critical thinking, entrepreneurship, collaboration, communication, growth mindset, global competence, and a host of skills with different names (Duckworth and Yeager, 2015 ; Zhao et al. 2019 ).

For humans to thrive in the age of smart machines, it is essential that they do not compete with machines. Instead, they need to be more human. Being unique and equipped with social-emotional intelligence are distinct human qualities (Zhao 2018b , 2018c ) that machines do not have (yet). In an AI world individual creativity, artistry and humanity will be important commodities that distinguish us from each other.

Moreover, given the rapidity of changes we are already experiencing, it is clear that lifelong careers and traditional employment pathways will not exist in the way that they have for past generations. Jobs and the way we do business will change and the change will be fast. Thus there are almost no knowledge or skills that can be guaranteed to meet the needs of the unknown, uncertain, and constantly changing future. For this reason, schools can no longer preimpose all that is needed for the future before students graduate and enter the world.

While helping students develop basic practical skills is still needed, education should also be about development of humanity in citizens of local, national, and global societies. Education must be seen as a pathway to attaining lifelong learning, satisfaction, happiness, wellbeing, opportunity and contribution to humanity. Schools therefore need to provide comprehensive access and deep exposure to all learning areas across all years in order to enable all students to make informed choices and develop their passions and unique talents.

A new curriculum that responds to these needs must do a number of things. First, it needs to help students develop the new competencies for the new age (Barber et al. 2012 ; Wagner 2008 , 2012 ; Wagner and Dintersmith 2016 ). To help students thrive in the age of smart machines and a globalized world, education must teach students to be creative, entrepreneurial, and globally competent (Zhao 2012a , 2012b ). The curriculum needs to focus more on developing students’ capabilities instead of focusing only on ‘template’ content and knowledge. It needs to be concerned with students’ social and emotional wellbeing as well. Moreover, it needs to make sure that students have an education experience that is globally connected and environmentally connected. As important is the gradual disappearance of school subjects such as history and physics for all students. The content is still important, but it should be incorporated into competency-based curriculum.