English Composition I - ENGL 1113

- Find eBooks

- Find Articles

- Search Tips

- Write It, Cite It

- Ask a Librarian

- This I Believe Invention Strategy

- The Annotated Bibliography

Requirements

Suggested writing prompt in "this i believe" format.

- Essay 2 - The Informative Essay

- Essay 3 - The Classical Argument Essay

The purpose of Essay 1 is to compose an essay that relates your prior experience and assumptions to new perspectives about a larger issue. Your connections should provide deeper insight to your audience. For this assignment you will identify something you believe to be true. You will then tell a story about how you came to believe it to be true.

- 2-3 pages (double-spaced), not including the Works Cited page, if required

- Utilize invention techniques : Before writing the essay, begin identifying your issue through a series of invention techniques, including but not limited to the following: brainstorming, listing, clustering, questioning, and conducting preliminary research.

- Plan and organize your essay : After the invention process, it is important to begin planning the organizational pattern for the essay. Planning includes identifying your thesis, establishing main ideas (or topic sentences) for each paragraph, supporting each paragraph with appropriate evidence, and creating ideas for the introductory and concluding paragraphs.

- Draft and revise your essay : Once you have completed the planning process, write a rough draft of your essay. Next, take steps to improve, polish, and revise your draft before turning it in for a final grade. The revision process includes developing ideas, ensuring the thesis statement connects to the main ideas of each paragraph, taking account of your evidence and supporting details, checking for proper use of MLA citation style, reviewing source integration, avoiding plagiarism, and proofreading for formatting and grammatical errors.

Your instructor may suggest another prompt and/or format. Follow your instructor's directions.

- Tell your story: Be specific. Take your belief out of the ether and ground it in the events that have shaped your core values. Consider moments when belief was formed or tested or changed. Think of your own experience, work, and family, and tell of the things your know that no one else does. Your story need not be heart-warming or gut wrenching - it can even be funny - but it should be real. Make sure your story ties to the essence of your daily life philosophy and the shaping of your beliefs.

- Be brief: Your statement should be between 500 and 800 words. That's about 2 to 3 pages double-spaced.

- Name your belief: If you can't name it in a sentence or two, your essay might not be about belief. Also, rather than writing a list, consider focusing on one core belief. For example: "I believe humans are essentially good." "I believe professors are really mentors." "I believe getting a college education is the key to success." "I believe everyone has a soul."

- Use chronological order: Narratives have a beginning, a middle, and an end.

- Be positive: Write about what you do believe, not what you don't believe. Avoid statements of religious dogma, preaching, or editorializing. This isn't an essay to "teach" someone.

- Be personal: Make your essay about you; speak in the fist person. Avoid speaking in the editorial "we." Tell a story from your own life; this is not an opinion piece about social ideals. Write in words and phrases that are comfortable for you to speak. We recommend you read your essay aloud to yourself several times, and each time edit it and simplify it until you find the words, tone, and story that truly echo your belief and the way you speak. Yes, you may use first person in this essay only.

This assignment helps you practice the following skills that are essential to your success in school and your professional life beyond school. In this assignment you will:

- Utilize descriptive language effectively to tell a story

- Describe things using sensory details and figurative language

- Compose a well-organized essay that includes an introduction, body, and conclusion.

- << Previous: The Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Essay 2 - The Informative Essay >>

- Last Updated: Mar 1, 2024 4:41 PM

- URL: https://libguides.occc.edu/comp1

Unit 4: Fundamentals of Academic Essay Writing

20 Exploring the Essay

Parts of an essay.

An essay typically has three basic parts, the introduction, the body, and the conclusion.

Student Model for Essay 1

The essay below is an authentic student essay. This essay was chosen as a model because it effectively demonstrates the characteristics of academic writing and has an important message for the reader.

Student name ESL 117 Essay #1, Draft #3

The Value of Peer Review in Improving Students’ Writing

The process of writing academic papers involves many steps: exploring a topic through reading and writing, narrowing a topic, organizing the ideas, writing multiple drafts, getting feedback and making revisions. Over multiple drafts, the writer refines his/her ideas in part by getting feedback from readers. In a classroom, the teacher and the classmates, or peers, can serve as easily accessible readers. Peer feedback, also called peer review or peer response, is widely used in writing classes for both native speakers and English as a Second Language (ESL) students. Peer review benefits both the writer and the reviewer, and it can be just as useful as teacher feedback.

Peer review is used in ESL classes to improve student’s English writing or get better grades on writing assignments. Many ESL programs involve international students in peer review to improve their writing skills, and many studies support the idea that peer review is essential to improve students’ writing skills. Bijami, Kashef and Nejad (2013) state that critical and specific peer comments can be utilized to enhance students’ writing skills and help students become competent writers (p.93). Peer comments can address specific aspects of writing. For example, peer comments help students improve their writing ability in terms of organization and content (Zeqiri, 2012, p. 50). Moreover, helping the writer identify the strengths and weaknesses in their writing helps the writer develop self-awareness. According to Tsui and Ng (2000), it is often difficult for students to see their own weaknesses, but peers can point out these problems (p. 166). These examples illustrate how ESL students’ writing skills can be enhanced through peer review because it helps them improve awareness of their papers’ strengths and weaknesses.

Not only does peer review benefit the writer, identifying strengths and weaknesses in another student’s writing plays an important role in improving the reviewer’s own writing ability. An important writing skill is to be able to recognize good writing by critically evaluating writing. By reading their classmates’ papers critically, students learn more about what makes writing successful and effective (Bijami et al., 2013, p. 94). In this way, reading other’s papers and being given criteria to look for allows students have a chance to develop these skills.

Furthermore, peer review seems to have some unexpected benefits for the reviewer. There are some studies that show that students who review peers’ papers are more likely to improve their writing ability than students who receive peers’ comments. Lundstrom and Baker (2009) conducted a study which compared the improvements in writing between givers and receivers of peer feedback and found that of the two groups, the giver group made more progress in writing than the receiver group (p. 32). This finding shows the givers (or reviewers) learned to judge their own work self-critically by evaluating their peers’ writing and transferring this knowledge to their own writing, resulting in significant improvements on their own papers. Thus, responding to a peer’s paper is an important way for a student to improve his/her own writing.

There are additional advantages of peer review for both the writer and the reviewer in terms of language skills, classroom environment, and confidence. Peer review not only helps students improve their writing skills but also helps them develop language skills. Language skills are developed through interaction and communication. Lundstrom and Baker (2009) write that peer review enhances not only students’ writing skills but also students’ speaking and listening skills (p. 31). Such research suggests that peer review can improve ESL students’ oral skills because they are involved in meaningful discussion and negotiations. Furthermore, peer review creates a student-centered classroom environment where students work together. Peer review encourages collaborative learning, in which students learn from and support each other (Tsui & Ng, 2000, p. 167). This collaborative group work helps to form a community of learners. In addition, peer review can increase a student’s interest and confidence in writing. Rather than relying on the teacher, the student is actively involved in the writing process (Bijami et al., 2013, p. 94). Such emphasis on learning independently further demonstrates the claim that as students take more responsibility for their writing, from developing their topic to writing drafts, they become more confident and inspired.

Although many students tend to prefer teacher feedback to peer feedback, there is evidence that peer review can be as helpful and meaningful as teacher feedback. In fact, recent studies reveal that there is no significant difference between teacher feedback and peer feedback in terms of improvement in students’ writing skills. In their study, Ruegg (2015) found that even though students who received teacher comments showed better performance on grammar than students who received peer comments, there was little difference between teacher comments and peer comments with regard to students’ improvements in areas such as organization, content, vocabulary, academic style and final grades (pp. 79-80). That is, peer feedback can be as effective as teacher feedback in revising students’ compositions and covers a wide range of writing skills. Based on their research which compared students who received peer comments to students who received teacher comments, Eksi’s findings (2012) also support Ruegg’s point that peer feedback enabled students to make significant writing improvements (p. 43). In sum, both teacher feedback and peer feedback helped students improve the quality of their writing.

In addition, teacher feedback and peer feedback can complement each other. To demonstrate this, Tsui and Ng (2000) cite a study in which 90% of the ESL students gave peer feedback that was judged to be valid by the teacher, and 60% of the students gave appropriate advice on aspects that had not been pointed out by the teacher (p. 149). These results mean that the vast majority of the student feedback was useful and accurate, and the students got additional feedback from peers that they would not have had if only the teacher had read the paper. Thus, peer feedback can expand the amount of useful feedback that the writer receives.

Many studies have shown the advantages of peer review such as improving students’ writing ability and language skills, developing students’ critical thinking skills and creating a student-centered classroom environment. That peer review is a time-consuming activity for both writing teachers and students is an undeniable fact, and students who are inexperienced in peer review will need training and guidance. Nevertheless, this investment in time and training gives students a powerful way to improve not only their writing skills, but also their abilities as thinkers and problem-solvers.

Bijami, M., Kashef, S., & Nejad, M. (2013). Peer feedback in learning English writing: Advantages and disadvantages. Journal of Studies in Education 3 (4), 91-7. doi: 10.5296/jse.v3i4.4314

Eksi, G. (2012). Peer review versus teacher feedback in process writing: How effective? International Journal of Applied Educational Studies 13 (1), 33-48.

Lundstrom, K., & Baker, W. (2009). To give is better than to receive: The benefits of peer review to the reviewer’s own writing. Journal of Second Language Writing 18 (1), 30-43. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2008.06.002

Ruegg, R. (2015). The relative effects of peer and teacher feedback on improvement in EFL students’ writing ability. Linguistics and Education 29 , 73-82 . doi: 10.1016/j.linged.2014.12.001

Tsui, A., & Ng, M. (2000). Do secondary L2 writers benefit from peer comments? Journal of Second Language Writing 9 (2), 147-170. doi: 10.1016/S1060-3743(00)00022-9

Zeqiri, L. (2012). The role of peer feedback in developing better writing skills. SEEU Review 8 (1), 43-62. doi: 10.2478/v10306-012-0003-8

Academic Writing I Copyright © by UW-Madison ESL Program is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.5: The Writing Process

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 53675

- Edgar Perez, Jenell Rae, Jacob Skelton, Lisa Horvath, & Sara Behseta

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The Writing Process

If you think that a blank sheet of paper or a blinking cursor on the computer screen is a scary sight, you are not alone. Many writers, students, and employees find that beginning to write can be intimidating. When faced with a blank page, however, experienced writers remind themselves that writing, like other everyday activities, is a process. Every process, from writing to cooking, bike riding, and learning to use a new cell phone, will get significantly easier with practice .

Just as you need a recipe, ingredients, and the proper tools to cook a delicious meal, you also need a plan , resources , and adequate time to create a well-written composition. In other words, writing is a process that requires following steps and using strategies to accomplish your goals.

Effective writing can be simply described as good ideas that are expressed well and arranged in the proper order. This chapter will give you the chance to work on all these important aspects of writing. In this chapter, we will be using the Proces s of writing an essay to illustrate the idea of of process writing.

Prewriting Home

Loosely defined, prewriting includes all the writing strategies employed before writing your first draft. Although many more prewriting strategies exist, the following section covers: using experience and observations, reading, freewriting, asking questions, listing, and clustering/idea mapping. Using the strategies in the following section can help you overcome the fear of the blank page and confidently begin the writing process.

C hoosing a Topic/Theme

In addition to understanding that writing is a process, writers also understand that choosing a good general topic for an assignment is an essential first step. Sometimes your instructor will give you an idea to begin an assignment, and other times your instructor will ask you to come up with a topic on your own. A good topic not only covers what an assignment will be about, but it also fits the assignment’s purpose and its audience . This textbook is theme-based, which means that each chapter has an underlying set of thematic readings.

In the next few sections, you will follow a writer named Romina as she explores and develops her essay’s topic and focus. You will also be planning one of your own. The first important step is for you to tell yourself why you are writing (to inform, to explain, or some other purpose) and for whom you are writing. Write your purpose and your audience on your own sheet of paper, and keep the paper close by as you read and complete exercises in this chapter and write the first draft.

- My purpose: ____________________________________________

- My audience: ___________________________________________

Prewriting Techniques: Brainstorming Home

Brainstorming refers to writing techniques used to:

- Generate topic ideas

- Transfer your abstract thoughts on a topic into more concrete ideas on paper (or digitally on a computer screen)

- Organize the ideas you have generated to discover a focus and develop a working thesis

Although brainstorming techniques can be helpful in all stages of the writing process, you will have to find the techniques that are most effective for your writing needs. The following general strategies can be used when initially deciding on a topic, or for narrowing the focus for a topic: Freewriting , Asking questions , Listing , and Clustering/Idea Mapping .

In the initial stage of the writing process, it is fine if you choose a general topic. Later you can use brainstorming strategies to narrow the focus of the topic.

Experience and Observations

When selecting a topic, you may want to consider something that interests you or something based on your own life and personal experiences. Even everyday observations can lead to interesting topics. After writers think about their experiences and observations, they often take notes on paper to better develop their thoughts. These notes help writers discover what they have to say about their topic.

Reading plays a vital role in all the stages of the writing process, but it first figures in the development of ideas and topics. Different kinds of documents can help you choose and develop a topic. For example, a magazine cover advertising the latest research on the threat of global warming may catch your eye in the supermarket. This subject may interest you, and you may consider global warming as a topic. Or maybe a novel’s courtroom drama sparks your curiosity of a particular lawsuit or legal controversy.

After you choose a topic, critical reading is essential to the development of a topic. While reading almost any document, you evaluate the author’s point of view by thinking about his main idea and his support. When you judge the author’s argument, you discover more about not only the author’s opinion but also your own. If this step already seems daunting, remember that even the best writers need to use prewriting strategies to generate ideas.

Prewriting strategies depend on your critical reading skills. Reading, prewriting and brainstorming exercises (and outlines and drafts later in the writing process) will further develop your topic and ideas. As you continue to follow the writing process, you will see how Romina uses critical reading skills to assess her own prewriting exercises.

Freewriting

Freewriting is an exercise in which you write freely about any topic for a set amount of time (usually five to seven minutes). During the time limit, you may jot down any thoughts that come to your mind. Try not to worry about grammar, spelling, or punctuation. Instead, write as quickly as you can without stopping. If you get stuck, just copy the same word or phrase over and over again until you come up with a new thought.

Writing often comes easier when you have a personal connection with the topic you have chosen. Remember, to generate ideas in your freewriting, you may also think about readings that you have enjoyed or that have challenged your thinking. Doing this may lead your thoughts in interesting directions.

Quickly recording your thoughts on paper will help you discover what you have to say about a topic. When writing quickly, try not to doubt or question your ideas. Allow yourself to write freely and unselfconsciously. Once you start writing with few limitations, you may find you have more to say than you first realized. Your flow of thoughts can lead you to discover even more ideas about the topic. Freewriting may even lead you to discover another topic that excites you even more.

Look at Romina’s example below. The instructor allowed the members of the class to choose their own topics, and Romina thought about her experiences as a communications major. She used this freewriting exercise to help her generate more concrete ideas from her own experience.

Freewriting Example

Last semester my favorite class was about mass media. We got to study radio and television. People say we watch too much television, and even though I try not to, I end up watching a few reality shows just to relax. Everyone has to relax! It’s too hard to relax when something like the news (my husband watches all the time) is on because it’s too scary now. Too much bad news, not enough good news. News. Newspapers I don’t read as much anymore. I can get the headlines on my homepage when I check my email. Email could be considered mass media too these days. I used to go to the video store a few times a week before I started school, but now the only way I know what movies are current is to listen for the Oscar nominations. We have cable but we can’t afford movie channels, so I sometimes look at older movies late at night. UGH. A few of them get played again and again until you’re sick of them. My husband thinks I’m crazy, but sometimes there are old black-and-whites on from the 1930s and ‘40s. I could never live my life in black-and-white. I like the home decorating shows and love how people use color on their walls. Makes rooms look so bright. When we buy a home, if we ever can, I’ll use lots of color. Some of those shows even show you how to do major renovations by yourself. Knock down walls and everything. Not for me–or my husband. I’m handier than he is. I wonder if they could make a reality show about us?

EXERCISE 1 Home

Freewrite about one event you have recently experienced. With this event in mind, write without stopping for five minutes. After you finish, read over what you wrote. Does anything stand out to you as a good general topic to write about? One of the following prompts may help you get started:

- A celebration

- The first day of a job or the first day of school

- The loss of a friend or relative

- Finding a place to live

Asking Questions

Who? What? Where? When? Why? How?

In everyday situations, you pose these kinds of questions to get more information. Who will be my partner for the project? When is the next meeting? Why is my car making that odd noise? When faced with a writing assignment, you might ask yourself, “How do I begin?”

You seek the answers to these questions to gain knowledge, to better understand your daily experiences, and to plan for the future. Asking these types of questions will also help you with the writing process. As you choose your topic, answering these questions can help you revisit the ideas you already have and generate new ways to think about your topic. You may also discover aspects of the topic that are unfamiliar to you and that you would like to learn more about. All these idea-gathering techniques will help you plan for future work on your assignment.

When Romina reread her freewriting notes, she found she had rambled and her thoughts were disjointed. She realized that the topic that interested her most was the one she started with, the media. She then decided to explore that topic by asking herself questions about it. Her purpose was to refine media into a topic she felt comfortable writing about. To see how asking questions can help you choose a topic, take a look at the following chart that Romina completed to record her questions and answers. She asked herself the questions that reporters and journalists use to gather information for their stories. The questions are often called the 5WH questions, after their initial letters.

Example of “Asking Questions”

Who? I use media. Students teachers, parents, employers and employees– almost everyone uses media.

What? The media can be a lot of things– television, radio, email (I think), newspapers, magazines, books.

Where? The media is almost everywhere now. It’s at home, at work, in cars, and even on cell phones.

When? The media has been around for a long time, but it seems a lot more important now.

Why? Hmm. This is a good question. I don’t know why there is mass media. Maybe we have it because we have the technology now. Or people live far away from their families and have to stay in touch.

How? Well, media is possible because of the technology inventions, but I don’t know how they all work.

EXERCISE 2 Home

Using the prompt you chose to practice freewriting in Exercise 1 , continue to explore the topic by answering the 5 WH questions, as Romina does in the above example.

Narrowing the focus

After rereading her essay assignment, Romina realized her general topic, mass media, is too broad for her class’s short paper requirement. Three pages are not enough to cover all the concerns in mass media today. Romina also realized that although her readers are other communications majors who are interested in the topic, they might want to read a paper about a particular issue in mass media.

The prewriting techniques of brainstorming by freewriting and asking questions helped Romina think more about her topic, but the following prewriting strategies can help her (and you) narrow the focus of the topic:

- Clustering/Idea Mapping

Narrowing the focus means breaking up the topic into subtopics, or more specific points. Generating lots of subtopics will help you eventually select the ones that fit the assignment and appeal to you and your audience.

Listing is a term often applied to describe any prewriting technique writers use to generate ideas on a topic, including freewriting and asking questions. You can make a list on your own or in a group with your classmates. Start with a blank sheet of paper (or a blank computer screen) and write your general topic across the top. Underneath your topic, make a list of more specific ideas. Think of your general topic as a broad category and the list items as things that fit in that category. Often you will find that one item can lead to the next, creating a flow of ideas that can help you narrow your focus to a more specific paper topic. The following is Romina’s brainstorming list:

From this list, Romina could narrow her focus to a particular technology under the broad category of “mass media.”

Idea Mapping

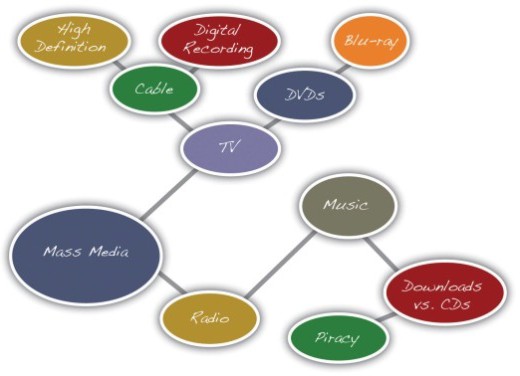

Idea mapping, sometimes called clustering or webbing, allows you to visualize your ideas on paper using circles, lines, and arrows. This technique is also known as clustering because ideas are broken down and clustered, or grouped together. Many writers like this method because the shapes show how the ideas relate or connect, and writers can find a focused topic from the connections mapped. Using idea mapping, you might discover interesting connections between topics that you had not thought of before.

To create an idea map:

- Start by writing your general topic in a circle in the center of a blank sheet of paper. Moving out from the main circle, write down as many concepts and terms ideas you can think of related to your general topic in blank areas of the page. Jot down your ideas quickly–do not overthink your responses. Try to fill the page.

- Once you’ve filled the page, circle the concepts and terms that are relevant to your topic. Use lines or arrows to categorize and connect closely related ideas. Add and cluster as many ideas as you can think of.

To continue brainstorming, Romina tried idea mapping. Review the following idea map that Romina created:

Notice Romina’s largest circle contains her general topic, mass media. Then, the general topic branches into two subtopics written in two smaller circles: television and radio. The subtopic television branches into even more specific topics: cable and DVDs. From there, Romina drew more circles and wrote more specific ideas: high definition and digital recording from cable and Blu-ray from DVDs. The radio topic led Romina to draw connections between music, downloads versus CDs, and, finally, piracy. From this idea map, Romina saw she could consider narrowing the focus of her mass media topic to the more specific topic of music piracy.

Topic Checklist: Developing a Good Topic

- Am I interested in this topic?

- Would my audience be interested?

- Do I have prior knowledge or experience with this topic? If so, would I be comfortable exploring this topic and sharing my experience?

- Do I want to learn more about this topic?

- Is this topic specific?

- Does it fit the length of the assignment

Prewriting strategies are a vital first step in the writing process. First, they help you choose a broad topic, and then they help you narrow the focus of the topic to a more specific idea. An effective topic ensures that you are ready for the next step: Developing a working thesis and planning the organization of your essay by creating an outline.

EXERCISE 3 Home

Return to the topic explored in Exercise 2 through the prewriting technique of answering questions (5 WH). Explore and narrow the topic further by practicing the prewriting techniques of Brainstorming (listing) and Idea Mapping. Allow yourself no more than five to seven minutes for each technique.

Collaboration: Share your results with a classmate or in small groups, and compare answers. Offer feedback to your classmate(s) on what you find interesting about his or her topic.

Key Takeaways

- All writers rely on steps and strategies to begin the writing process.

- The steps in the writing process are prewriting, outlining, writing a rough draft, revising, and editing.

- Writers often choose a general topic first and then narrow the focus to a more specific topic.

- Prewriting includes any brainstorming technique used to generate ideas, narrow the focus of abstract thoughts and ideas, and transfer them into written form.

- A good topic interests the writer, appeals to the audience, and fits the purpose of the writing project.

Purpose of an Outline

Once your topic has been chosen, your ideas have been generated through brainstorming techniques, and you’ve developed a working thesis, the next step in the prewriting stage is to create an outline. Sometimes called a “blueprint,” or “plan” for your paper, an outline helps writers organize their thoughts and categorize the main points they wish to make in an order that makes sense.

Creating an outline is an important step in the writing process!

The purpose of an outline is to help you organize your paper by checking to see if and how your ideas connect to each other, or whether you need to flesh out a point or two.

No matter the length of the paper, from a three-page weekly assignment to a 50-page senior thesis, outlines can help you see the overall picture.

Having an outline also helps prevent writers from “getting stuck” when writing the first draft of an essay.

A well-developed outline will show the essential elements of an essay:

- thesis of essay

- main idea of each body paragraph

- evidence/support offered in each paragraph to substantiate the main points

A well-developed outline breaks down the parts of your thesis in a clear, hierarchical manner. Writing an outline before beginning an essay helps the writer organize ideas generated through brainstorming and/or research. In short, a well-developed outline makes your paper easier to write.

The formatting of any outline is not arbitrary; the system of formatting and number/letter designations creates a visual hierarchy of the ideas, or points, being made in the essay.

Major points, in other words, should not be buried in subtopic levels.

Types of Outlines

Alphanumeric Outlines

This is the most common type of outline used and is usually instantly recognizable to most people. The formatting follows these characters, in this order:

Level 1: Roman Numerals (I, II, III, IV, V, etc.)

Level 2: Capitalized Letters (A, B, C, D, E, etc.)

Level 3: Arabic Numerals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.)

Level 4: Lowercase Letters (a, b, c, d, e, etc.)

Alphanumeric Example

I. (Main point) Lowering the speed limit to 55 mph on Interstate highways is a cost effective way to reduce pollution and greenhouse gases

A. (Supporting detail) Gas mileage significantly decreases at speeds over 55 mph

1. (Supporting detail for sub-point) Slowing down from 65 mph to 55 mph can increase MPG by as much as 15 percent

a. (Additional explanation/support for supporting detail) Each 5 mph driven over 60 mph is like paying an additional $0.21 per gallon for gas (at $3.00 per gallon).

If the outline needs to subdivide beyond these divisions, use Arabic numerals inside parentheses and then lowercase letters inside parentheses.

Decimal Outlines

The decimal outline follows the same levels of indentation when formatting to indicate the hierarchy of ideas/points as the alphanumeric outline. The added benefit of decimal notation, however, is that it clearly shows, through the decimal breakdown, how each progressive level relates to the larger whole.

Decimal Example

1. (Main point) Lowering the speed limit on all Interstate highways to 55 mph would create a significant, cost free reduction in air pollution

1.1 (Supporting detail) Gas consumption significantly increases at speeds over 55 mph

1.2 (Supporting detail for sub-point) Slowing down from 65 mph to 55 mph can increase your MPG by as much as 15 percent, and thereby eliminate 15 percent of carbon emissions

1.3 (Additional explanation/support for supporting detail) According to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), “as a rule of thumb, each 5 mph driven over 60 mph is like paying an additional $0.21 per gallon for gas (at $3.00 per gallon).”

Micro and Macro Outlines

The indentation/formatting of a micro (full sentence) or macro (topic) outline is essentially the same as alphanumeric/decimal outlines. The difference between micro and macro outlines lies in the specificity and depth of the content.

Micro outlines focus on the “micro,” the drilled-down specific details of the essay’s content. They are particularly useful when the topic you are discussing is complex in nature. When creating a micro outline, it can also be useful to insert the quotations you plan to include in the essay (with citations) and subsequent analyses of quotes. Taking this extra step helps ensure that you have enough support for your ideas, as well as reminding writers to actually analyze and discuss quotations, rather than simply inserting quotes and moving on. While time-consuming to create, micro outlines can be seen as basically creating the first rough draft of an essay.

Macro outlines, in contrast, focus on the “big picture” of an essay’s main points and support by using short phrases or keywords to indicate the focus and content at each level of the essay’s development. A macro outline is useful when writing about a variety of ideas and issues where the ordering of points is more flexible. Macro outlines are also especially helpful when writing timed essays, or essay exam questions–or any rhetorical situation where writers need to quickly get their ideas down in an organized essay format.

Micro/Full-Sentence Outline Example

I. (Main point) Lowering the speed limit on all Interstate highways to 55 mph would create a significant, cost free reduction in air pollution.

A. (Supporting detail) Gas consumption significantly increases at speeds over 55 mph.

(Supporting detail for sub-point) Slowing down from 65 mph to 55 mph can increase your car’s MPG by as much as 15 percent, and thereby eliminate 15 percent of carbon emissions.

a. (Additional explanation/support for supporting detail) According to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), “as a rule of thumb, each 5 mph driven over 60 mph is like paying an additional $0.21 per gallon for gas (at $3.00 per gallon)”.

Macro/Topic Outline Example

A. (Supporting detail) Increase of Consumption over 55 mph

1. (Supporting detail for sub-point) Consumption and carbon emissions

a. (Additional explanation/support for supporting detail) Amount of money saved

Creating an Outline

Identify your topic: Put the topic in your own words in with a single sentence or phrase to help you stay on topic.

Determine your main points. What are the main points you want to make to convince your audience? Refer back to the prewriting/brainstorming exercise of answering 5 WH questions: “why or how is the main topic important?” Using your brainstorming notes, you should be able to create a working thesis.

List your main points/ideas in a logical order. You can always change the order later as you evaluate your outline.

Create sub-points for each major idea. Typically, each time you have a new number or letter, there need to be at least two points (i.e. if you have an A, you need a B; if you have a 1, you need a 2; etc.). Though perhaps frustrating at first, it is indeed useful because it forces you to think hard about each point; if you can’t create two points, then reconsider including the first in your paper, as it may be extraneous information that may detract from your argument.

Evaluate: Review your organizational plan, your blueprint for your paper. Does each paragraph have a controlling idea/topic sentence? Is each point adequately supported? Look over what you have written. Does it make logical sense? Is each point suitably fleshed out? Is there anything included that is unnecessary?

EXERCISE 4 Home

1. Create a sentence outline from the following introductory paragraph in alphanumeric format:

The popularity of knitting is cyclical, rising and falling according to the prevailing opinion of women’s places in society. Though internationally a unisex hobby, knitting is pervasively thought of as a woman’s hobby in the United States. Knitting is currently enjoying a boost in popularity as traditionally minded women pick up the craft while women who enjoy subverting traditional gender roles have also picked up the needles to reclaim “the lost domestic arts” and give traditionally feminine crafts the proper respect. American men are also picking up the needles in greater numbers, with men’s knitting guilds and retreats nationwide. This rise in popularity has made the receiving of hand-knit items special, and many people enjoy receiving these long-lasting, painstakingly crafted items. For any knitters, the perfect gift starts by choosing the perfect yarn. Choosing the perfect yarn for a knitting project relies on the preferences of the person for whom the project is being made, the availability of the yarn, and the type of yarn recommended by the pattern.

What is the thesis? How is the topic introduced? Is there a hierarchy of supporting points?

2. Now create your own outline based on the topic you developed in Exercise 3 .

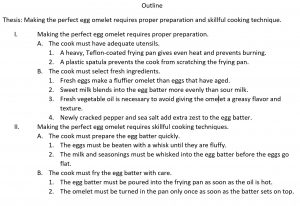

Sample of 3-Level Alphanumeric Outline

Drafting is the stage of the writing process in which you develop a complete first version of a piece of writing. Even professional writers admit that an empty page scares them because they feel they need to come up with something fresh and original every time they open a blank document on their computers. Because you have completed the first two steps in the writing process, you have already recovered from empty page syndrome. You have prewriting and planning already done, so you know what will go on that blank page: what you wrote in your outline.

Goals and Strategies for Drafting

Your objective at this stage of the writing process is to draft an essay with at least three body paragraphs, which means that the essay will contain a minimum of five paragraphs, including an introduction and a conclusion. A draft is a complete version of a piece of writing, but it is not the final version. The step in the writing process after drafting, as you may remember, is revising. During revising, you will have the opportunity to make changes to your first draft before you put the finishing touches on it during the editing and proofreading stage. A first draft gives you a working version that you can later improve.

If you are more comfortable starting on paper than on the computer, you can start on paper and then type it before you revise. You can also use a voice recorder to get yourself started, dictating a paragraph or two to get you thinking. In this lesson, Romina does all her work on the computer, but you may use pen and paper or the computer to write a rough draft.

Making the Writing Process Work for You

The following approaches, done alone or in combination with others, may improve your writing and help you move forward in the writing process:

- Begin writing with the part you know the most about: You can start with the third paragraph in your outline if ideas come easily to mind. You can start with the second paragraph or the first paragraph, too. Although paragraphs may vary in length, keep in mind that short paragraphs may contain insufficient support. Readers may also think the writing is abrupt. Long paragraphs may be wordy and may lose your reader’s interest. As a guideline, try to write paragraphs longer than one sentence but shorter than the length of an entire double-spaced page.

- Write one paragraph at a time and then stop: As long as you complete the assignment on time, you may choose how many paragraphs you complete in one sitting. Pace yourself. On the other hand, try not to procrastinate. Writers should always meet their deadlines.

- Take short breaks to refresh your mind: This tip might be most useful if you are writing a multi-page report or essay. Still, if you are antsy or cannot concentrate, take a break to let your mind rest. But do not let breaks extend too long. If you spend too much time away from your essay, you may have trouble starting again. You may forget key points or lose momentum. Try setting an alarm to limit your break, and when the time is up, return to your desk to write.

- Be reasonable with your goals: If you decide to take ten-minute breaks, try to stick to that goal. If you told yourself that you need more facts, then commit to finding them. Holding yourself to your own goals will create successful writing assignments.

- Keep your audience and purpose in mind as you write: These aspects of writing are just as important when you are writing a single paragraph for your essay as when you are considering the direction of the entire essay.

Of all of these considerations, keeping your purpose and your audience at the front of your mind is the most important key to writing success. If your purpose is to persuade, for example, you will present your facts and details in the most logical and convincing way you can. Your purpose will guide your mind as you compose your sentences. Your audience will guide word choice. Are you writing for experts, for a general audience, for other college students, or for people who know very little about your topic? Keep asking yourself what your readers, with their background and experience, need to be told in order to understand your ideas. How can you best express your ideas so they are totally clear and your communication is effective?

You may want to identify your purpose and audience on an index card that you clip to your paper (or keep next to your computer). On that card, you may want to write notes to yourself—perhaps about what that audience might not know or what it needs to know—so that you will be sure to address those issues when you write. It may be a good idea to also state exactly what you want to explain to that audience, or to inform them of, or to persuade them about.

Using the topic for the essay that you outlined in the second step of Exercise 4 , describe your purpose and your audience as specifically as you can. Use your own sheet of paper to record your responses. Then keep these responses near you during future stages of the writing process.

Purpose: ______________________________________________

Audience: _____________________________________________

Discovering the Basic Elements of a First Draft

If you have been using the information in the previous chapters step by step to help you develop an assignment, you already have both a formal topic outline and a formal sentence outline to direct your writing. Knowing what a first draft looks like will help you make the creative leap from the outline to the first draft

A first draft should include the following elements:

- An introduction that piques the audience’s interest, tells what the essay is about, and motivates readers to keep reading.

- A thesis statement that presents the main point, or controlling idea, of the entire piece of writing.

- A topic sentence in each paragraph that states the main idea of the paragraph and implies how that main idea connects to the thesis statement.

- Supporting sentences in each paragraph that develop or explain the topic sentence. These can be specific facts, examples, anecdotes, or other details that elaborate on the topic sentence.

- A conclusion that reinforces the thesis statement and leaves the audience with a feeling of completion.

The Bowtie Method

There are many ways to think about the writing process as a whole. One way to imagine your essay is to see it like a bowtie. In the figure below, you will find a visual representation of this metaphor. The left side of the bow is the introduction, which begins with a hook and ends with the thesis statement. In the center, you will find the body paragraphs, which grow with strength as the paper progresses, and each paragraph contains a supported topic sentence. On the right side, you will find the conclusion. Your conclusion should reword your thesis and then wrap up the paper with a summation, clinch, or challenge. In the end, your paper should present itself as a neat package, like a bowtie.

Figure of the “Bowtie Method”

Starting Your First Draft Home

Now we are finally ready to look over Romina’s shoulder as she begins to write her essay about digital technology and the confusing choices that consumers face. As she does, you should have in front of you your outline, with its thesis statement and topic sentences, and the notes you wrote earlier in this lesson on your purpose and audience. Reviewing these will put both you and Romina in the proper mind-set to start.

The following is Romina’s thesis statement:

E-book readers are changing the way people read.

Here are the notes that Romina wrote to herself to characterize her purpose and audience:

Everyone wants the newest and the best digital technology, but the choices are many, and the specifications are often confusing.

Purpose: My purpose is to inform readers about the wide variety of consumer digital technology available in stores and to explain why the specifications for these products, expressed in numbers that average consumers don’t understand, often cause bad or misinformed buying decisions.

Audience: My audience is my instructor and members of this class. Most of them are not heavy into technology except for the usual laptops, cell phones, and MP3 players, which are not topics I’m writing about. I’ll have to be as exact and precise as I can be when I explain possibly unfamiliar product specifications. At the same time, they’re more with it electronically than my grandparents’ VCR-flummoxed generation, so I won’t have to explain every last detail.

Romina chose to begin by writing a quick introduction based on her thesis statement. She knew that she would want to improve her introduction significantly when she revised. Right now, she just wanted to give herself a starting point. Remember that she could have started directly with any of the body paragraphs. You will learn more about writing attention-getting introductions and effective conclusions later in this chapter.

With her thesis statement and her purpose and audience notes in front of her, Romina then looked at her sentence outline. She chose to use that outline because it includes the topic sentences. The following is the portion of her outline for the first body paragraph. The Roman numeral I identifies the topic sentence for the paragraph, capital letters indicate supporting details, and Arabic numerals label sub-points.

I. Ebook readers are changing the way people read.

A. Ebook readers make books easy to access and to carry.

1. Books can be downloaded electronically.

2. Devices can store hundreds of books in memory.

B. The market expands as a variety of companies enter it.

1. Booksellers sell their own ebook readers.

2. Electronics and computer companies also sell ebook readers.

C. Current ebook readers have significant limitations.

1. The devices are owned by different brands and may not be compatible.

2. Few programs have been made to duplicate the way Americans borrow and read printed books.

Romina then began to expand the ideas in her outline into a paragraph. Notice how the outline helped her guarantee that all her sentences in the body of the paragraph develop the topic sentence.

Ebook readers are changing the way people read, or so ebook developers hope. The main selling point for these handheld devices, which are sort of the size of a paperback book, is that they make books easy to access and carry. Electronic versions of printed books can be downloaded online for a few bucks or directly from your cell phone. These devices can store hundreds of books in memory and, with text-to-speech features, can even read the texts. The market for ebooks and ebook readers keeps expanding as a lot of companies enter it. Online and traditional booksellers have been the first to market ebook readers to the public, but computer companies, especially the ones already involved in cell phone, online music, and notepad computer technology, will also enter the market. The problem for consumers, however, is which device to choose. Incompatibility is the norm. Ebooks can be read-only on the devices they were intended for. Furthermore, use is restricted by the same kind of DRM systems that restrict the copying of music and videos. So, book buyers are often unable to lend books to other readers, as they can with a read book. Few accommodations have been made to fit the other way Americans read: by borrowing books from libraries. What is a buyer to do?

If you write your first draft on the computer, consider creating a new file folder for each course with a set of sub-folders inside the course folders for each assignment you are given. Label the folders clearly with the course names, and label each assignment folder and word processing document with a title that you will easily recognize. The assignment name is a good choice for the document. Then use that sub-folder to store all the drafts you create. When you start each new draft, do not just write over the last one. Instead, save the draft with a new tag after the title—draft 1, draft 2, and so on—so that you will have a complete history of drafts in case your instructor wishes you to submit them. In your documents, observe any formatting requirements—for margins, headers, placement of page numbers, and other layout matters—that your instructor requires.

Study how Romina made the transition from her sentence outline to her first draft. First, copy her outline onto your own sheet of paper. Leave a few spaces between each part of the outline. Then copy sentences from Romina’s paragraph to align each sentence with its corresponding entry in her outline.

Continuing the First Draft

Romina continued writing her essay, moving to the second and third body paragraphs. She had supporting details but no numbered sub-points in her outline, so she had to consult her prewriting notes for specific information to include.

If you decide to take a break between finishing your first body paragraph and starting the next one, do not start writing immediately when you return to your work. Put yourself back in context and in the mood by rereading what you have already written. This is what Romina did. If she had stopped writing in the middle of writing the paragraph, she could have jotted down some quick notes to herself about what she would write next.

Preceding each body paragraph that Romina wrote is the appropriate section of her sentence outline. Notice how she expanded Roman numeral II from her outline into a first draft of the second body paragraph. As you read, ask yourself how closely she stayed on purpose and how well she paid attention to the needs of her audience.

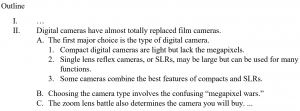

Digital cameras have almost totally replaced film cameras in amateur photographers’ gadget bags. My father took hundreds of slides when his children were growing up, but he had more and more trouble getting them developed. So, he decided to go modern. But, what kind of camera should he buy? The small compact digital cameras could slip right in his pocket, but if he tried to print a photograph larger than an 8 x 10, the quality would be poor. When he investigated buying a single lens reflex camera, or SLR, he discovered that they were as versatile as his old film camera, also an SLR, but they were big and bulky. Then he discovered yet a third type, which combined the smaller size of the compact digital cameras with the zoom lenses available for SLRs. His first thought was to buy one of those, but then he realized he had a lot of decisions to make. How many megapixels should the camera be? Five? Ten? What is the advantage of each? Then came the size of the zoom lens. He knew that 3x was too small, but what about 25x? Could he hold a lens that long without causing camera shake? He read many photography magazines and buying guides, and he still wasn’t sure he was right.

Romina then began her third and final body paragraph using Roman numeral III from her outline.

Nothing is more confusing to me than choosing among televisions. It confuses lots of people who want a new high-definition digital television (HDTV) with a large screen to watch sports and DVDs on. You could listen to the guys in the electronics stores, but word has it they know little more than you do. They want to sell you what they have in stock, not what best fits your needs. You face decisions you never had to make with the old, bulky picture-tube televisions. Screen resolution means the number of horizontal scan lines the screen can show. This resolution is often 1080p, or full HD, or 768p. The trouble is that if you have a smaller screen, 32 inches or 37 inches, you won’t be able to tell the difference with the naked eye. The 1080p televisions cost more, though, so those are what the salespeople want you to buy. They get bigger commissions. The other important decision you face as you walk around the sales floor is whether to get a plasma screen or an LCD screen. Now here the salespeople may finally give you decent info. Plasma flat-panel television screens can be much larger in diameter than their LCD rivals. Plasma screens show decent lacks and can be viewed at a wider angle than current LCD screens. But be careful and tell the salesperson you have budget constraints. Large flat- panel plasma screens are much more expensive than flat-screen LCD models. Don’t buy more television than you need.

Reread body paragraphs two and three of the essay that Romina is writing. Then answer the questions on your own sheet of paper.

- In body paragraph two, Romina decided to develop her paragraph as a nonfiction narrative. Do you agree with her decision? Explain. How else could she have chosen to develop the paragraph? Why is that better?

- Compare the writing styles of paragraphs two and three. What evidence do you have that Romina was getting tired or running out of steam? What advice would you give her? Why?

- Choose one of these two body paragraphs. Write a version of your own that you think better fits Romina’s audience and purpose.

Writing a Title

A writer’s best choice for a title is one that alludes to the main point of the entire essay. Like the headline in a newspaper or the big, bold title in a magazine, an essay’s title gives the audience a first peek at the content. If readers like the title, they are likely to keep reading.

Following her outline carefully, Romina crafted each paragraph of her essay. Moving step by step in the writing process, Romina finished the draft and even included a brief concluding paragraph which you will read later. She then decided, as the final touch for her writing session, to add an engaging title.

Thesis Statement:

Working Title:

Digital Technology: The Newest and the Best at What Price?

- Make the writing process work for you. Use any and all of the strategies that help you move forward in the writing process.

- Always be aware of your purpose for writing and the needs of your audience. Cater to those needs in every sensible way.

- Remember to include all the key structural parts of an essay: a thesis statement that is part of your introductory paragraph, three or more body paragraphs as described in your outline, and a concluding paragraph. Then add an engaging title to draw in readers.

- Write paragraphs of an appropriate length for your writing assignment. Paragraphs in college-level writing can be a page long, as long as they cover the main topics in your outline.

- Use your topic outline or your sentence outline to guide the development of your paragraphs and the elaboration of your ideas. Each main idea, indicated by a Roman numeral in your outline, becomes the topic of a new paragraph. Develop it with the supporting details and the sub-points of those details that you included in your outline.

- Generally speaking, write your introduction and conclusion last, after you have fleshed out the body paragraphs.

Drafting Body Paragraphs Home

If your thesis gives the reader a roadmap to your essay, then body paragraphs should closely follow that map. The reader should be able to predict what follows your introductory paragraph by simply reading the thesis statement. The body paragraphs present the evidence you have gathered to confirm your thesis. Before you begin to support your thesis in the body, you must find information from a variety of sources that support and give credit to what you are trying to prove.

Select Primary Support for Your Thesis

Without primary support, your argument is not likely to be convincing.

Primary support can be described as the major points you choose to expand on your thesis. It is the most important information you select to argue for your point of view. Each point you choose will be incorporated into the topic sentence for each body paragraph you write. Your primary supporting points are further supported by supporting details within the paragraphs.

Remember that a worthy argument is backed by examples. In order to construct a valid argument, good writers conduct lots of background research and take careful notes.

They also talk to people knowledgeable about a topic in order to understand its implications before writing about it. For guidance on incorporating research into your paragraphs, see the section “Using Sources.”

Identify the Characteristics of Good Primary Support

In order to fulfill the requirements of good primary support, the information you choose must meet the following standards:

- Be relevant to the thesis: Primary support is considered strong when it relates directly to the thesis. Primary support should show, explain, or prove your main argument without delving into irrelevant details. When faced with lots of information that could be used to prove your thesis, you may think you need to include it all in your body paragraphs. But effective writers resist the temptation to lose focus. Choose your supporting points wisely by making sure they directly connect to your thesis.

- Be specific: The main points you make about your thesis and the examples you use to expand on those points need to be more specific than the thesis. Use specific examples to provide the evidence and to build upon your general ideas. These types of examples give your reader something narrow to focus on, and if used properly, they leave little doubt about your claim. General examples, while they convey the necessary information, are not nearly as compelling or useful in writing because they are too obvious and typical.

- Be detailed: Remember that your thesis, while specific, should not be very detailed. The body paragraphs are where you develop the discussion that a thorough essay requires. Using detailed support shows readers that you have considered all the facts and chosen only the most precise details to enhance your point of view.

Pre-write to Identify Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

Recall that when you pre-write you essentially make a list of examples or reasons why you support your stance. Stemming from each point, you further provide details to support those reasons. After prewriting, you are then able to look back at the information and choose the most compelling pieces you will use in your body paragraphs.

Select the Most Effective Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

As you developed a working thesis through prewriting techniques, you may have generated a lot of information, which may be edited out later. Remember that your primary support must be relevant to your thesis. Remind yourself of your main argument, and delete any ideas that do not directly relate to it. Omitting unrelated ideas ensures that you will use only the most convincing information in your body paragraphs. Choose at least three of only the most compelling points. These will serve as the topic sentences for your body paragraphs.

When you support your thesis, you are revealing evidence. Evidence includes anything that can help support your stance. The following are the kinds of evidence you will encounter as you conduct your research:

- Facts: Facts are the best kind of evidence to use because they often cannot be disputed. They can support your stance by providing background information on or a solid foundation for your point of view. However, some facts may still need explanation. For example, the sentence “The most populated state in the United States is California” is a pure fact, but it may require some explanation to make it relevant to your specific argument.

- Judgments: Judgments are conclusions drawn from the given facts. Judgments are more credible than opinions because they are founded upon careful reasoning and examination of a topic.

- Testimony: Testimony consists of direct quotations from either an eyewitness or an expert witness. An eyewitness is someone who has direct experience with a subject; he adds authenticity to an argument based on facts. An expert witness is a person who has extensive experience with a topic. This person studies the facts and provides commentary based on either facts or judgments, or both. An expert witness adds authority and credibility to an argument.

- Personal observation: Personal observation is similar to testimony, but personal observation consists of your testimony. It reflects what you know to be true because you have experiences and have formed either opinions or judgments about them. For instance, if you are one of five children and your thesis states that being part of a large family is beneficial to a child’s social development, you could use your own experience to support your thesis.

You can consult a vast pool of resources to gather support for your stance. Citing relevant information from reliable sources ensures that your reader will take you seriously and consider your assertions. Use any of the following sources for your essay: newspapers or news organization websites, magazines, encyclopedias, and scholarly journals, which are periodicals that address topics in a specialized field. When using sources, you are responsible for properly documenting the borrowed information properly. Refer to the section “ Using Sources” for more information.

Choose Supporting Topic Sentences

Each body paragraph contains a topic sentence that states one aspect of your thesis and then expands upon it. Like the thesis statement, each topic sentence should be specific and supported by concrete details, facts, or explanations.

Each body paragraph should comprise the following elements: topic sentence + supporting details (examples, reasons, or arguments)

As you read in Writing Paragraphs , topic sentences indicate the location and main points of the basic arguments of your essay. These sentences are vital to writing your body paragraphs because they always refer back to and support your thesis statement. Topic sentences are linked to the ideas you have introduced in your thesis, thus reminding readers what your essay is about. A paragraph without a clearly identified topic sentence may be unclear and scattered, just like an essay without a thesis statement.

Unless your professor instructs otherwise, you should include at least three body paragraphs in your essay. A five-paragraph essay, including the introduction and conclusion, is commonly the standard for exams and essay assignments because it is meant to help students create fully developed essays; however, writers should maintain flexibility and not expect all essays to conform to that model. The emphasis is on creating an essay that provides enough support to tell a story, create an image or idea, or inform or persuade the audience.

Consider the following example of a thesis statement:

Author J.D. Salinger relied primarily on his personal life and belief system as the foundation for the themes in the majority of his works.

The following topic sentence is a primary supporting point for the thesis. The topic sentence states exactly what the controlling idea of the paragraph is .

Salinger, a World War II veteran, suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, a disorder that influenced themes in many of his works.

The following paragraph contains supporting detail sentences for the primary support sentence (the topic sentence), which is underlined.

Salinger, a World War II veteran, suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, a disorder that influenced the themes in many of his works. He did not hide his mental anguish over the horrors of war and once told his daughter, “You never really get the smell of burning flesh out of your nose, no matter how long you live.” His short story “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” details a day in the life of a WWII veteran who was recently released form an army hospital for psychiatric problems. The man acts questionably with a little girl he meets on the beach before he returns to his hotel room and commits suicide. Another short Story, “For Esme – with Love and Squalor,” is narrated by a traumatized soldier who sparks an unusual relationship with a young girl he meets before he departs to partake in D-Day. Finally, in Salinger’s only novel, the Catcher in The Rye, he continues with the theme of posttraumatic stress, though not directly related to war. From a rest home for the mentally ill, sixteen-year-old Holden Caulfield narrates the story of his nervous breakdown following the death of his younger brother.

Draft Supporting Detail Sentences for Each Primary Support Sentence

After deciding which primary support points you will use as your topic sentences, you must add details to clarify and demonstrate each of those points. These supporting details provide examples, facts, or evidence that support the topic sentence. The writer drafts possible supporting detail sentences for each primary support sentence based on the thesis statement:

Thesis: Unleashed dogs on city streets are a dangerous nuisance.

I. Dogs can scare cyclists.

A. Cyclists are forced to zigzag on the roads.

B. School children panic and turn wildly on their bikes.

C. People walking at night freeze in fear.

II. Loose dogs are traffic hazards.

A. Dogs in the street make people swerve their cars.

B. To avoid dogs, drivers run into other cars or pedestrians.

C. Children coaxing dogs across city streets create danger.

III. Unleashed dogs damage gardens.

A. They step on flowers and vegetables.

B. They destroy hedges by urinating on them.

C. They mess up lawns by digging holes.

You have the option of writing your topic sentences in one of three ways. You can state it at the beginning of the body paragraph, or at the end of the paragraph, or you do not have to write it at all. This is called an implied topic sentence . An implied topic sentence lets readers form the main idea for themselves. For beginning writers, it is best to not use implied topic sentences because it makes it harder to focus your writing. Your instructor may also want to clearly identify the sentences that support your thesis.

- Your body paragraphs should closely follow the path set forth by your thesis statement.

- Strong body paragraphs contain evidence that supports your thesis.

- Primary support comprises the most important points you use to support your thesis. Strong primary support is specific, detailed, and relevant to the thesis.

- Prewriting helps you determine your most compelling primary support.

- Evidence includes facts, judgments, testimony, and personal observation.

- Reliable sources may include newspapers, magazines, academic journals, books, encyclopedias, and firsthand testimony.

- A topic sentence presents one point of your thesis statement while the information in the rest of the paragraph supports that point.

- A body paragraph comprises a topic sentence plus supporting details.

Print out the first draft of your essay and use a highlighter to mark your topic sentences in the body paragraphs. Make sure they are clearly stated and accurately present your paragraphs, as well as accurately reflect your thesis. If your topic sentence contains information that does not exist in the rest of the paragraph, rewrite it to more accurately match the rest of the paragraph.

EXERCISE 9 Home

Choose one of the following working thesis statements. On a separate sheet of paper, write for at least five minutes using one of the prewriting techniques you learned in Chapter 2, “Pre-Writing Techniques.”

- Unleashed dogs on city streets are a dangerous nuisance.

- Students cheat for many different reasons.

- Drug use among teens and young adults is a problem.

- The most important change that should occur at my college or university is _______________________________________________

EXERCISE 10 Home

Refer to the previous Exercise 9 and select three of your most compelling reasons to support the thesis statement. Remember that the points you choose must be specific and relevant to the thesis. The statements you choose will be your primary support points, and you will later incorporate them into the topic sentences for the body paragraphs.

Collaboration : Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

EXERCISE 11 Home

In the previous Exercise 10 , you chose three of your most convincing points to support the thesis statement you selected from the list. Take each point and incorporate it into a topic sentence for each body paragraph.

EXERCISE 12

Using the three topic sentences you composed for the thesis statement in Exercise 11 , draft at least three supporting details for each point.

Drafting Introductory and Concluding Paragraphs

Picture your introduction as a storefront window: You have a certain amount of space to attract your customers (readers) to your goods (subject) and bring them inside your store (discussion). Once you have enticed them with something intriguing, you then point them in a specific direction and try to make the sale (convince them to accept your thesis). Your introduction is an invitation to your readers to consider what you have to say and then to follow your train of thought as you expand upon your thesis statement.

Writing an Introduction

An introduction serves the following purposes:

- Establishes your voice and tone, or your attitude, toward the subject

- Introduces the general topic of the essay

- States the thesis that will be supported in the body paragraphs

First impressions are crucial and can leave lasting effects in your reader’s mind, which is why the introduction is so important to your essay. If your introductory paragraph is dull or disjointed, your reader probably will not have much interest in continuing with the essay.

Attracting Interest in Your Introductory Paragraph

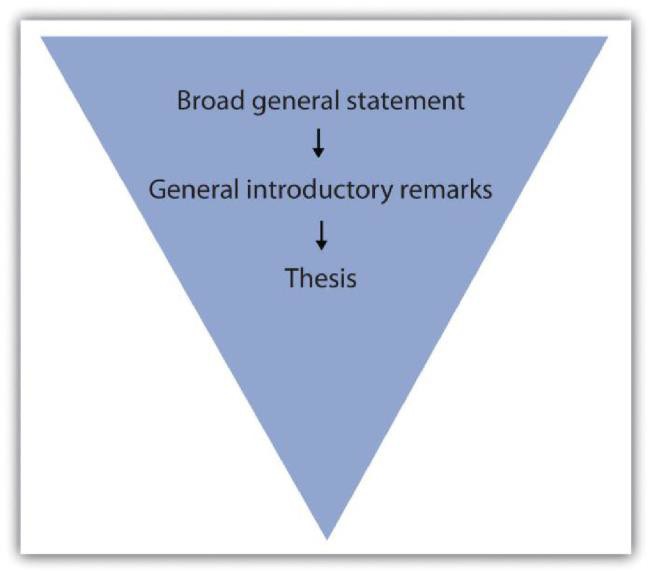

Your introduction should begin with an engaging statement devised to provoke your readers’ interest. In the next few sentences, introduce them to your topic by stating general facts or ideas about the subject. As you move deeper into your introduction, you gradually narrow the focus, moving closer to your thesis. Moving smoothly and logically from your introductory remarks to your thesis statement can be achieved using a funnel technique, as illustrated in the diagram “Funnel Technique.”

Immediately capturing your readers’ interest increases the chances of having them read what you are about to discuss. You can garner curiosity for your essay in a number of ways. Try to get your readers personally involved by doing any of the following:

- Appealing to their emotions

- Using logic

- Beginning with a provocative question or opinion

- Opening with a startling statistic or surprising fact

- Raising a question or series of questions

- Presenting an explanation or rationalization for your essay

- Opening with a relevant quotation or incident

- Opening with a striking image

- Including a personal anecdote

Remember that your diction, or word choice, while always important, is most crucial in your introductory paragraph. Boring diction could extinguish any desire a person might have to read through your discussion. Choose words that create images or express action.

Earlier in this chapter we followed Romina as she moved through the writing process. In this section, Romina writes her introduction and conclusion for the same essay. Romina incorporates some of the introductory elements into her introductory paragraph, which she previously outlined. Her thesis statement is underlined.

Play Atari on a General Electric brand television set? Maybe watch Dynasty? Or read old newspaper articles on microfiche at the library? Twenty-five years ago, the average college student did not have many options when it came to entertainment in the form of technology. Fast forward to the twenty-first century, and the digital age has revolutionized the way people entertain themselves. In today’s rapidly evolving world of digital technology, consumers are bombarded with endless options for how they do most everything, from buying and reading books to taking and developing photographs. In a society that is obsessed with digital means of entertainment, it is easy for the average person to become baffled. Everyone wants the newest and best digital technology, but the choices are many and the specifications are often confusing.

Writing a Conclusion

It is not unusual to want to rush when you approach your conclusion, and even experienced writers may fade. But what good writers remember is that it is vital to put just as much attention into the conclusion as in the rest of the essay. After all, a hasty ending can undermine an otherwise strong essay.

A conclusion that does not correspond to the rest of your essay, has loose ends, or is unorganized can unsettle your readers and raise doubts about the entire essay.

However, if you have worked hard to write the introduction and body, your conclusion can often be the most logical part to compose.

The Anatomy of a Strong Conclusion

Keep in mind that the ideas in your conclusion must conform to the rest of your essay. In order to tie these components together, restate your thesis at the beginning of your conclusion. This helps you assemble, in an orderly fashion, all the information you have explained in the body. Repeating your thesis reminds your readers of the major arguments you have been trying to prove and also indicates that your essay is drawing to a close. A strong conclusion also reviews your main points and emphasizes the importance of the topic.