- Scholarly Community Encyclopedia

- Log in/Sign up

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | handwiki | -- | 1044 | 2022-10-31 01:38:44 |

Video Upload Options

- MDPI and ACS Style

- Chicago Style

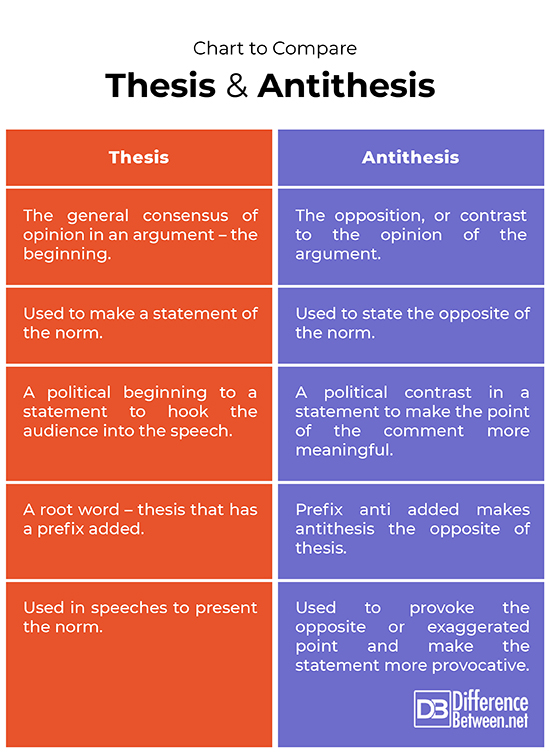

In philosophy, the triad of thesis, antithesis, synthesis (German: These, Antithese, Synthese; originally: Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis) is a progression of three ideas or propositions. The first idea, the thesis, is a formal statement illustrating a point; it is followed by the second idea, the antithesis, that contradicts or negates the first; and lastly, the third idea, the synthesis, resolves the conflict between the thesis and antithesis. It is often used to explain the dialectical method of German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, but Hegel never used the terms himself; instead his triad was concrete, abstract, absolute. The thesis, antithesis, synthesis triad actually originated with Johann Fichte.

1. History of the Idea

Thomas McFarland (2002), in his Prolegomena to Coleridge's Opus Maximum , [ 1 ] identifies Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (1781) as the genesis of the thesis/antithesis dyad. Kant concretises his ideas into:

- Thesis: "The world has a beginning in time, and is limited with regard to space."

- Antithesis: "The world has no beginning and no limits in space, but is infinite, in respect to both time and space."

Inasmuch as conjectures like these can be said to be resolvable, Fichte's Grundlage der gesamten Wissenschaftslehre ( Foundations of the Science of Knowledge , 1794) resolved Kant's dyad by synthesis, posing the question thus: [ 1 ]

- No synthesis is possible without a preceding antithesis. As little as antithesis without synthesis, or synthesis without antithesis, is possible; just as little possible are both without thesis.

Fichte employed the triadic idea "thesis–antithesis–synthesis" as a formula for the explanation of change. [ 2 ] Fichte was the first to use the trilogy of words together, [ 3 ] in his Grundriss des Eigentümlichen der Wissenschaftslehre, in Rücksicht auf das theoretische Vermögen (1795, Outline of the Distinctive Character of the Wissenschaftslehre with respect to the Theoretical Faculty ): "Die jetzt aufgezeigte Handlung ist thetisch, antithetisch und synthetisch zugleich." ["The action here described is simultaneously thetic, antithetic, and synthetic." [ 4 ] ]

Still according to McFarland, Schelling then, in his Vom Ich als Prinzip der Philosophie (1795), arranged the terms schematically in pyramidal form.

According to Walter Kaufmann (1966), although the triad is often thought to form part of an analysis of historical and philosophical progress called the Hegelian dialectic, the assumption is erroneous: [ 5 ]

Whoever looks for the stereotype of the allegedly Hegelian dialectic in Hegel's Phenomenology will not find it. What one does find on looking at the table of contents is a very decided preference for triadic arrangements. ... But these many triads are not presented or deduced by Hegel as so many theses, antitheses, and syntheses. It is not by means of any dialectic of that sort that his thought moves up the ladder to absolute knowledge.

Gustav E. Mueller (1958) concurs that Hegel was not a proponent of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, and clarifies what the concept of dialectic might have meant in Hegel's thought. [ 6 ]

"Dialectic" does not for Hegel mean "thesis, antithesis, and synthesis." Dialectic means that any "ism" – which has a polar opposite, or is a special viewpoint leaving "the rest" to itself – must be criticized by the logic of philosophical thought, whose problem is reality as such, the "World-itself".

According to Mueller, the attribution of this tripartite dialectic to Hegel is the result of "inept reading" and simplistic translations which do not take into account the genesis of Hegel's terms:

Hegel's greatness is as indisputable as his obscurity. The matter is due to his peculiar terminology and style; they are undoubtedly involved and complicated, and seem excessively abstract. These linguistic troubles, in turn, have given rise to legends which are like perverse and magic spectacles – once you wear them, the text simply vanishes. Theodor Haering's monumental and standard work has for the first time cleared up the linguistic problem. By carefully analyzing every sentence from his early writings, which were published only in this century, he has shown how Hegel's terminology evolved – though it was complete when he began to publish. Hegel's contemporaries were immediately baffled, because what was clear to him was not clear to his readers, who were not initiated into the genesis of his terms. An example of how a legend can grow on inept reading is this: Translate "Begriff" by "concept," "Vernunft" by "reason" and "Wissenschaft" by "science" – and they are all good dictionary translations – and you have transformed the great critic of rationalism and irrationalism into a ridiculous champion of an absurd pan-logistic rationalism and scientism. The most vexing and devastating Hegel legend is that everything is thought in "thesis, antithesis, and synthesis." [ 7 ]

Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) adopted and extended the triad, especially in Marx's The Poverty of Philosophy (1847). Here, in Chapter 2, Marx is obsessed by the word "thesis"; [ 8 ] it forms an important part of the basis for the Marxist theory of history. [ 9 ]

2. Writing Pedagogy

In modern times, the dialectic of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis has been implemented across the world as a strategy for organizing expositional writing. For example, this technique is taught as a basic organizing principle in French schools: [ 10 ]

The French learn to value and practice eloquence from a young age. Almost from day one, students are taught to produce plans for their compositions, and are graded on them. The structures change with fashions. Youngsters were once taught to express a progression of ideas. Now they follow a dialectic model of thesis-antithesis-synthesis. If you listen carefully to the French arguing about any topic they all follow this model closely: they present an idea, explain possible objections to it, and then sum up their conclusions. ... This analytical mode of reasoning is integrated into the entire school corpus.

Thesis, Antithesis, and Synthesis has also been used as a basic scheme to organize writing in the English language. For example, the website WikiPreMed.com advocates the use of this scheme in writing timed essays for the MCAT standardized test: [ 11 ]

For the purposes of writing MCAT essays, the dialectic describes the progression of ideas in a critical thought process that is the force driving your argument. A good dialectical progression propels your arguments in a way that is satisfying to the reader. The thesis is an intellectual proposition. The antithesis is a critical perspective on the thesis. The synthesis solves the conflict between the thesis and antithesis by reconciling their common truths, and forming a new proposition.

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge: Opus Maximum. Princeton University Press, 2002, p. 89.

- Harry Ritter, Dictionary of Concepts in History. Greenwood Publishing Group (1986), p.114

- Williams, Robert R. (1992). Recognition: Fichte and Hegel on the Other. SUNY Press. p. 46, note 37.

- Fichte, Johann Gottlieb; Breazeale, Daniel (1993). Fichte: Early Philosophical Writings. Cornell University Press. p. 249.

- Walter Kaufmann (1966). "§ 37". Hegel: A Reinterpretation. Anchor Books. ISBN 978-0-268-01068-3. OCLC 3168016. https://archive.org/details/hegelreinterpret00kauf.

- Mueller, Gustav (1958). "The Hegel Legend of "Thesis-Antithesis-Synthesis"". Journal of the History of Ideas 19 (4): 411–414. doi:10.2307/2708045. https://dx.doi.org/10.2307%2F2708045

- Mueller 1958, p. 411.

- marxists.org: Chapter 2 of "The Poverty of Philosophy", by Karl Marx https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/poverty-philosophy/ch02.htm

- Shrimp, Kaleb (2009). "The Validity of Karl Marx's Theory of Historical Materialism". Major Themes in Economics 11 (1): 35–56. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/mtie/vol11/iss1/5/. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- Nadeau, Jean-Benoit; Barlow, Julie (2003). Sixty Million Frenchmen Can't Be Wrong: Why We Love France But Not The French. Sourcebooks, Inc.. p. 62. https://archive.org/details/sixtymillionfren00nade_041.

- "The MCAT writing assignment.". Wisebridge Learning Systems, LLC. http://www.wikipremed.com/mcat_essay.php. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Advisory Board

A Beginner’s guide to Fundamental Principles of Marxism

Marxist thought primarily critiques capitalism. It was founded by the renowned German philosopher, theorist and revolutionist Karl Hein Marx (1818-1883) and Fredrich Engels. Besides being a globally adapted and practised social and political theory, Marxism has influenced prominent modern literary theories like historicism, feminism, deconstruction, postcolonialism and cultural studies. This article discusses the fundamental principles of Marxism as established by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

What are the Fundamental Principles of Marx’s Thought?

The foremost step towards understanding marxist literary theory is to be familiar with the basic principles of Marxism.

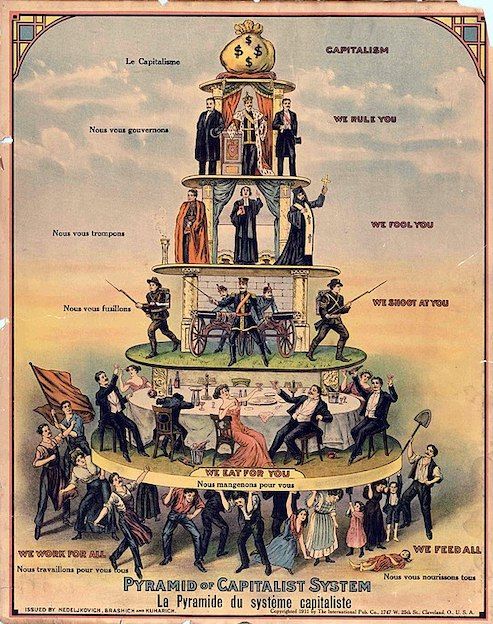

I. Critique of Capitalism

A capitalistic society is characterised by features such as private ownership of means of production, minimal governmental intervention, and profit. For example, the United States is a typical capitalist society. Most of the means of production in the U.S. are privately owned by individual entrepreneurs or private corporations. The economy of the nation is primarily driven by profit and has minimal governmental intervention. One of the most significant and foremost principles of marxism is the critique of capitalism.

Karl Marx objected to Capitalism on the basis of four factors:

- Capitalism concentrated the means of production, property, and wealth in the hands of a particular class, the bourgeoisie.

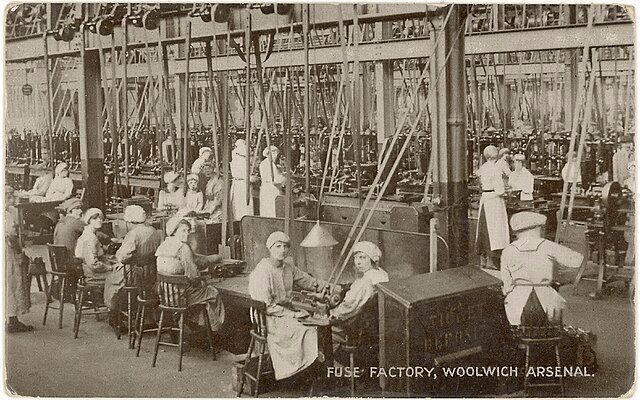

- Since wealth belongs exclusively to the bourgeoisie, the proletariat or the working class is constantly exploited and oppressed. Capitalism generates a working class that exists only as long as they are able to find work. The workers are employable as long as they generate profit for the bourgeoisie and increase their capital. Thus, the working class is reduced to a commodity serving for the benefits of the capitalist class.

- Capitalism possesses an imperialistic nature. In order to perpetuate their wealth, the bourgeoisie exploits globally and “creates a world after its own image”.

- Capitalism reduces all human relationships to a cash nexus that are driven by self-interest and monetary calculations. Even a family is reduced to an economic commodity. A bourgeois man in a capitalistic society reduces the wife to a source of production. Within a capitalistic society, it is the capital that has a character or an individuality. All individuals are completely chained to it and are robbed off their identities.

II. Dialectic of History is motivated by material forces- Impact of Hegel on Marx

Vladimir Lenin has accurately pointed out that “I t is impossible completely to understand Marx’s Capital, and specially its first chapter, without having thoroughly studied and understood the whole of Hegel’s Logic. ” Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel or G.W.F Hegel (1770-1831) was one of the most influential German philosophers who significantly shaped Marx’s philosophy. Hegel regarded dialectics as the hallmark of his philosophy and used it in his Encyclopedia of Philosophical Sciences (1817) and Elements of the Philosophy of Right (1820)

Understanding Hegel’s Dialectics

Hegel’s concept of dialectics is primarily a synthesis of opposites. It is popularly known as the triad of thesis, antithesis and synthesis . It is a process where tensions are eventually resolved throughout history. In the first stage, a thesis is proposed, or an idea is defined. This initial thesis is a simplistic and individualistic definition of an idea. During the second stage, there is an antithesis that opposes the definition of the proposed initial thesis, and in the process provides a wider scope to the initial idea. The final stage or the synthesis is the reconciliation between the thesis and the antithesis. It acts as a union between the particular and the universal. Hegel employed dialectical methodology while exploring the concept of freedom in the Philosophy of Right. We can utilise this to understand the dialectical methodology.

- Thesis: The concept of Freedom: This would include the simple and individual definition of freedom. Freedom means that one is free to do whatever they want to without considering any external factors.

- Antithesis : The antithesis criticises the definition of freedom. It points out that if everyone began to do as they pleased and practised absolute freedom without any social consciousness, it would inevitably result in chaos. Thus, it attempts to situate the concept of freedom against a wider social context.

- Synthesis: The final stage unites the thesis and the antithesis while providing a wider scope to the meaning of freedom. The abstract and absolute idea of freedom eventually gets synthesised to ‘freedom within a civil society’. Thus, synthesis not only reconciles thesis and antithesis, but also generates a new definition of freedom where individuals can do as they please as long as they are in harmony with societal peace. There exists a balance between absolute freedom and restriction.

Even though the triad of Thesis-Antithesis-Synthesis is famously attributed to Hegel, he never employed these terms for his dialectical methodology. The triad of thesis-antithesis-synthesis was coined by the German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fitche . Nevertheless, it provides an outline to his philosophy of dialectics. Hegel extensively explains his dialectical method in Encyclopedia Logic , the first part of his Encyclopedia of Philosophical Sciences . According to him, a logic has three moments:

- The moment of Understanding : This is the first moment, and is that of absolute fixity where a concept has a fixed definition.

- Negatively Rational : This is the second moment. It is the instance of instability in which exists the process of self-sublation (aufheben). This is a significant stage in Hegel’s dialectical process. Self-sublation or aufheben carries a double meaning. It means both to negate (cancel) as well as to preserve. The first moment of understanding sublates itself because its one-sided or absoluteness destabilises and pushes it towards the opposite. The moment of understanding or fixity simultaneously cancels and preserves itself.

- The speculative or the positively rational : This is the third moment in a logic. It unites the conflict between the moment of understanding and the moment of negatively rational. This speculative or positive rational is the negation of certain determinations and creates a new form.

Thus, Hegel uses the abstract-negative-concrete scheme where something concrete forms through the reconciliation between the abstract and the negative.

Hegel perceived dialectic operating throughout history - from the Oriental world through the Greek and Roman, to the modern German world. According to him, the underlying principles of one society eventually created successive new societies. Although a new society is based on entirely new principles, they still absorb and adapt certain values of the previous society. One of the most significant features of Hegel’s dialectics is the thought that every concept must be situated in a historical context, and as a product of certain historic relations.

Differences between the dialectical approaches of Marx and Hegel

For Karl Marx, dialectics was significant and relevant. It was Hegel’s concept of freedom that drove the bourgeoisie to revolt and bring down feudalism whose social hierarchy was based on irrational theology and superstition. They eventually established a free economy based on rationality and a free individual. Thus, for Marx, dialectic was a powerful political tool that could negate the state of affairs. Like Hegel, Marx also established that earlier phases in history were sublated during their negation by subsequent phases. However, where Hegel believed that the dialectical movement of history was driven by divine spirit, for Marx, the dialectic of history was driven by material forces and relations of economic production. Particularly, Marxism states that history is driven by class struggle: “ The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle ”. (The Communist Manifesto)

Marxism emphasises that dialectic in history is a combination of theory and practice. An established system and society cannot be overthrown by thought and theory alone. Marx states that “ The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it ”.

Marxism theory inverts Hegel’s dialectical methodology. In his Capital Volume I Marx remarks that Hegel’s dialectic was “ standing on its head. It must be turned right side up again, if you would discover the rational kernel within the mystical shell. ”

For Hegel, progress or societal change was the product of the conflict in ideas. For Karl Marx, ideas were shaped by material forces throughout history.

"My dialectic method is not only different from the Hegelian, but is its direct opposite. To Hegel, the life process of the human brain, i.e., the process of thinking, which, under the name of “the Idea,” he even transforms into an independent subject, is the demiurgos of the real world, and the real world is only the external, phenomenal form of “the Idea.” With me, on the contrary, the ideal is nothing else than the material world reflected by the human mind, and translated into forms of thought."

In his A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859) Marx points out that

“At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production…Then begins an era of social revolution. The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the transformation of the whole immense superstructure”

He highlights the class struggles between the slaves and the freemen, patricians and plebeians, lords and serfs throughout history. He states that at present the class struggle is between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. Just like the capitalistic society had sublated the feudal society, socialism would eventually negate and sublate capitalism. Capitalism would continue to cause economic crisis and oppression when eventually the working class would unite and revolt against the bourgeoisie. Thus, capitalistic exploitation would inevitably end once the masses would have suffered perpetually.

With time, as the wealth and property will get concentrated in the hands of fewer and fewer people, the working class or the proletariat will continue to grow in number. Eventually, the oppressed labour class that is forced into discipline will organise, revolt and overthrow the capitalists. For Marx, this is the dialectical movement from feudalism through capitalism to communism. Thus, the capitalistic stage represents the negation of feudalism. Similarly, communalism becomes the negation of negation where the conflict between private property and socialised production is resolved by the establishment of socialised property. We must keep in mind that Marx did not mean that communism will completely overtake capitalism. Instead, it will grow out of capitalism while retaining its ideals of freedom and democracy.

III. The Division of Labour

Division of labour is the process in which a production is broken down into multiple separate tasks for efficiency. Each task is then assigned to different individuals or groups of individuals. As a result, the workers are alienated and detached from the final product. Marxism emphasises that there have been various forms of ownership throughout history. For him, there were three significant consequences of social division of labour.

- Since the division of labour distributes work unequally, it results in private property.

- Emergence of State that forms like an illusionary communal life detached from individuals and community. Marx emphasises that all struggles within a state are various disguised versions of class struggles.

- The division of labour leads to alienation of social activity.

IV. Concept of Ideology

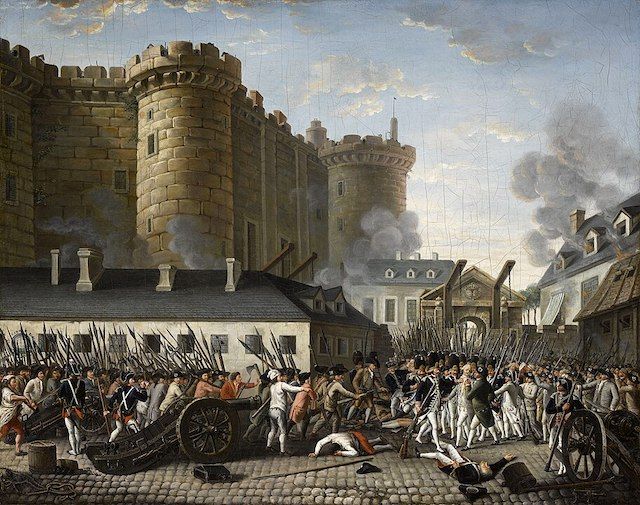

Ideology is a set of beliefs and ideas that legitimises and validates the existence and the dominance of the ruling class. It is through ideology that the capitalist class is able to skew the true and exploitative nature of prevalent social and economic relations. The class in power must gain political agency inorder to maintain its power position and project its interest as general interest. This is where the concept of ideology arrives. According to Marxism, the class that possesses the material forces in a society also rules its intellectual domain. Since it is a class that is in possession of property and wealth, it can promulgate its ideas in the fields of law, morality, religion and art and advertise them as universal. For example, before the French revolution (1789-1799) it was the monarchy and the nobility that enjoyed the most economic and social power. In order to maintain their position, the ruling class perpetuated ideologies such as the divine rights of kings where the kings were declared to be chosen by God. This ensured minimal conflict and opposition. The French Revolution was the result of perpetual economic crisis, social injustices, and political oppression inflicted by aristocracy and monarchy. As a result, it overthrew monarchy and its ideologies of feudalism and divinity. In its place rose the bourgeoisie or the capitalistic middle class and their ideologies of equality, liberty, and fraternity.

According to Marxism, the ideology of the ruling class is always projected as the ideology and interest of people as a whole. Moreover, the modern state is nothing “but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie”

The fundamental principles of Marxism have been extremely impactful in social and economic spheres. Even today, when it is perceived to be obsolete, we must realise that the principles of marxism are dialectical. As our world changes, these principles too continue to change, adapt and extend to the evolving societies. Just like other critical theories, Marxism is not a complete and static system but is a dynamic critical theory that is still crucial and relevant to our world.

Barlas, Baran. "What do Hegel and Marx Have in Common?" TheCollector.com, December 15, 2022, https://www.thecollector.com/what-do-hegel-and-marx-have-in-common/ .

Cuddon, John A. The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory. London, England, Penguin Books, 2014

Economic Manuscripts: Preface to a Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy.” Www.marxists.org, www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1859/critique-pol-economy/preface.htm#005

Marx, Karl. “Economic Manuscripts: Capital Vol. I - 1873 Afterword.” Marxists.org, 2019, www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/p3.htm .

Rafey Habib. A History of Literary Criticism and Theory : From Plato to the Present. Malden, Mass., Blackwell Publ, 2009

What is Dialectic Materialism: Basic Methodology of Marx

Karl Marx is one of the most influential thinkers in the history of sociology, and his concept of dialectic materialism is a central aspect of his political and economic philosophy. Dialectical materialism refers to the theory that human history is shaped by the interaction between the material conditions of society and the ideas, values, and beliefs of individuals.

Marx believed that the material conditions of society, including the means of production, the distribution of wealth and resources, and the structure of the economy, are the primary determinants of social and political life. These material conditions are not fixed or eternal, but are constantly in flux, subject to change and development over time.

The material conditions of society, according to Marx, give rise to conflicting social classes, each with its own interests and objectives. The struggle between these classes, in turn, drives the process of historical development and leads to the transformation of social and economic systems. This struggle is the dialectical process, which involves the synthesis of opposing forces and the creation of something new and different.

Marx’s concept of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis is a central aspect of his theory of dialectical materialism. This concept refers to a process of change and development in which an existing idea, system, or condition (thesis) is challenged by an opposing force (antithesis) and the two are ultimately synthesized into a new, integrated, and higher-level idea or condition (synthesis).

The concept of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis is based on the idea that change and development occur through the resolution of contradictions. The thesis represents the existing state of affairs, while the antithesis represents the opposing forces that challenge it. The synthesis is the result of the resolution of the contradictions between the thesis and antithesis.

For Marx, the material conditions of society, including the means of production, the distribution of wealth and resources, and the structure of the economy, are the primary determinants of social and political life. These material conditions give rise to conflicting social classes, each with its own interests and objectives. The struggle between these classes is the dialectical process, which involves the synthesis of opposing forces and the creation of something new and different.

For example, Marx viewed the capitalist system as the thesis, and the working class as the antithesis. The struggle between the capitalist class and the working class leads to the synthesis of a new and higher-level social and economic system, such as socialism.

Marx argued that the process of historical development is not linear or predictable, but is shaped by the contradictions and conflicts that arise from the contradictions between the material conditions of society and the ideas and values of individuals. He saw history as a process of continuous change and development, driven by the struggle between different classes and the contradictions that arise from the material conditions of society.

Marx also believed that the ideas, values, and beliefs of individuals are shaped by the material conditions of society. He argued that individuals’ consciousness is determined by their social and economic conditions, and that ideas and beliefs are products of material reality, rather than the other way around.

Marx’s theory of dialectical materialism was developed in response to the idealist philosophical traditions of the time, which saw ideas and beliefs as the primary determinants of social and political life. Marx rejected this view and argued that it was the material conditions of society that shaped ideas, rather than the other way around.

Marx’s concept of dialectical materialism was central to his political and economic philosophy. He believed that the exploitation of the working class by the ruling class was the result of the material conditions of capitalism, and that the only way to achieve a fair and just society was to overthrow the capitalist system and establish a socialist society based on collective ownership of the means of production.

Marx’s ideas have had a profound impact on sociology and other social sciences, and his concept of dialectical materialism continues to be a subject of debate and discussion among scholars. Some view his ideas as outdated and irrelevant, while others see them as a powerful tool for understanding the complexities of contemporary society and the challenges facing the world today.

In conclusion, Karl Marx’s concept of dialectical materialism is a central aspect of his political and economic philosophy and continues to be a subject of debate and discussion among scholars. Marx believed that the material conditions of society are the primary determinants of social and political life, and that the struggle between conflicting social classes drives the process of historical development. He saw history as a process of continuous change and development, driven by the contradictions and conflicts that arise from the material conditions of society and the ideas and values of individuals. Despite its controversies, Marx’s concept of dialectical materialism remains an important part of the intellectual heritage of sociology and continues to shape our understanding of the social and political world.

Related Posts

Discourse, power and knowledge – by michel foucault (2022), talcott parsons: the social system, and general action theory (1952), leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Anatomy & Physiology

- Astrophysics

- Earth Science

- Environmental Science

- Organic Chemistry

- Precalculus

- Trigonometry

- English Grammar

- U.S. History

- World History

... and beyond

- Socratic Meta

- Featured Answers

What are thesis, antithesis, synthesis? In what ways are they related to Marx?

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Hegel’s Dialectics

“Dialectics” is a term used to describe a method of philosophical argument that involves some sort of contradictory process between opposing sides. In what is perhaps the most classic version of “dialectics”, the ancient Greek philosopher, Plato (see entry on Plato ), for instance, presented his philosophical argument as a back-and-forth dialogue or debate, generally between the character of Socrates, on one side, and some person or group of people to whom Socrates was talking (his interlocutors), on the other. In the course of the dialogues, Socrates’ interlocutors propose definitions of philosophical concepts or express views that Socrates challenges or opposes. The back-and-forth debate between opposing sides produces a kind of linear progression or evolution in philosophical views or positions: as the dialogues go along, Socrates’ interlocutors change or refine their views in response to Socrates’ challenges and come to adopt more sophisticated views. The back-and-forth dialectic between Socrates and his interlocutors thus becomes Plato’s way of arguing against the earlier, less sophisticated views or positions and for the more sophisticated ones later.

“Hegel’s dialectics” refers to the particular dialectical method of argument employed by the 19th Century German philosopher, G.W.F. Hegel (see entry on Hegel ), which, like other “dialectical” methods, relies on a contradictory process between opposing sides. Whereas Plato’s “opposing sides” were people (Socrates and his interlocutors), however, what the “opposing sides” are in Hegel’s work depends on the subject matter he discusses. In his work on logic, for instance, the “opposing sides” are different definitions of logical concepts that are opposed to one another. In the Phenomenology of Spirit , which presents Hegel’s epistemology or philosophy of knowledge, the “opposing sides” are different definitions of consciousness and of the object that consciousness is aware of or claims to know. As in Plato’s dialogues, a contradictory process between “opposing sides” in Hegel’s dialectics leads to a linear evolution or development from less sophisticated definitions or views to more sophisticated ones later. The dialectical process thus constitutes Hegel’s method for arguing against the earlier, less sophisticated definitions or views and for the more sophisticated ones later. Hegel regarded this dialectical method or “speculative mode of cognition” (PR §10) as the hallmark of his philosophy and used the same method in the Phenomenology of Spirit [PhG], as well as in all of the mature works he published later—the entire Encyclopaedia of Philosophical Sciences (including, as its first part, the “Lesser Logic” or the Encyclopaedia Logic [EL]), the Science of Logic [SL], and the Philosophy of Right [PR].

Note that, although Hegel acknowledged that his dialectical method was part of a philosophical tradition stretching back to Plato, he criticized Plato’s version of dialectics. He argued that Plato’s dialectics deals only with limited philosophical claims and is unable to get beyond skepticism or nothingness (SL-M 55–6; SL-dG 34–5; PR, Remark to §31). According to the logic of a traditional reductio ad absurdum argument, if the premises of an argument lead to a contradiction, we must conclude that the premises are false—which leaves us with no premises or with nothing. We must then wait around for new premises to spring up arbitrarily from somewhere else, and then see whether those new premises put us back into nothingness or emptiness once again, if they, too, lead to a contradiction. Because Hegel believed that reason necessarily generates contradictions, as we will see, he thought new premises will indeed produce further contradictions. As he puts the argument, then,

the scepticism that ends up with the bare abstraction of nothingness or emptiness cannot get any further from there, but must wait to see whether something new comes along and what it is, in order to throw it too into the same empty abyss. (PhG-M §79)

Hegel argues that, because Plato’s dialectics cannot get beyond arbitrariness and skepticism, it generates only approximate truths, and falls short of being a genuine science (SL-M 55–6; SL-dG 34–5; PR, Remark to §31; cf. EL Remark to §81). The following sections examine Hegel’s dialectics as well as these issues in more detail.

1. Hegel’s description of his dialectical method

2. applying hegel’s dialectical method to his arguments, 3. why does hegel use dialectics, 4. is hegel’s dialectical method logical, 5. syntactic patterns and special terminology in hegel’s dialectics, english translations of key texts by hegel, english translations of other primary sources, secondary literature, other internet resources, related entries.

Hegel provides the most extensive, general account of his dialectical method in Part I of his Encyclopaedia of Philosophical Sciences , which is often called the Encyclopaedia Logic [EL]. The form or presentation of logic, he says, has three sides or moments (EL §79). These sides are not parts of logic, but, rather, moments of “every concept”, as well as “of everything true in general” (EL Remark to §79; we will see why Hegel thought dialectics is in everything in section 3 ). The first moment—the moment of the understanding—is the moment of fixity, in which concepts or forms have a seemingly stable definition or determination (EL §80).

The second moment—the “ dialectical ” (EL §§79, 81) or “ negatively rational ” (EL §79) moment—is the moment of instability. In this moment, a one-sidedness or restrictedness (EL Remark to §81) in the determination from the moment of understanding comes to the fore, and the determination that was fixed in the first moment passes into its opposite (EL §81). Hegel describes this process as a process of “self-sublation” (EL §81). The English verb “to sublate” translates Hegel’s technical use of the German verb aufheben , which is a crucial concept in his dialectical method. Hegel says that aufheben has a doubled meaning: it means both to cancel (or negate) and to preserve at the same time (PhG §113; SL-M 107; SL-dG 81–2; cf. EL the Addition to §95). The moment of understanding sublates itself because its own character or nature—its one-sidedness or restrictedness—destabilizes its definition and leads it to pass into its opposite. The dialectical moment thus involves a process of self -sublation, or a process in which the determination from the moment of understanding sublates itself , or both cancels and preserves itself , as it pushes on to or passes into its opposite.

The third moment—the “ speculative ” or “ positively rational ” (EL §§79, 82) moment—grasps the unity of the opposition between the first two determinations, or is the positive result of the dissolution or transition of those determinations (EL §82 and Remark to §82). Here, Hegel rejects the traditional, reductio ad absurdum argument, which says that when the premises of an argument lead to a contradiction, then the premises must be discarded altogether, leaving nothing. As Hegel suggests in the Phenomenology , such an argument

is just the skepticism which only ever sees pure nothingness in its result and abstracts from the fact that this nothingness is specifically the nothingness of that from which it results . (PhG-M §79)

Although the speculative moment negates the contradiction, it is a determinate or defined nothingness because it is the result of a specific process. There is something particular about the determination in the moment of understanding—a specific weakness, or some specific aspect that was ignored in its one-sidedness or restrictedness—that leads it to fall apart in the dialectical moment. The speculative moment has a definition, determination or content because it grows out of and unifies the particular character of those earlier determinations, or is “a unity of distinct determinations ” (EL Remark to §82). The speculative moment is thus “truly not empty, abstract nothing , but the negation of certain determinations ” (EL-GSH §82). When the result “is taken as the result of that from which it emerges”, Hegel says, then it is “in fact, the true result; in that case it is itself a determinate nothingness, one which has a content” (PhG-M §79). As he also puts it, “the result is conceived as it is in truth, namely, as a determinate negation [ bestimmte Negation]; a new form has thereby immediately arisen” (PhG-M §79). Or, as he says, “[b]ecause the result, the negation, is a determinate negation [bestimmte Negation ], it has a content ” (SL-dG 33; cf. SL-M 54). Hegel’s claim in both the Phenomenology and the Science of Logic that his philosophy relies on a process of “ determinate negation [ bestimmte Negation]” has sometimes led scholars to describe his dialectics as a method or doctrine of “determinate negation” (see entry on Hegel, section on Science of Logic ; cf. Rosen 1982: 30; Stewart 1996, 2000: 41–3; Winfield 1990: 56).

There are several features of this account that Hegel thinks raise his dialectical method above the arbitrariness of Plato’s dialectics to the level of a genuine science. First, because the determinations in the moment of understanding sublate themselves , Hegel’s dialectics does not require some new idea to show up arbitrarily. Instead, the movement to new determinations is driven by the nature of the earlier determinations and so “comes about on its own accord” (PhG-P §79). Indeed, for Hegel, the movement is driven by necessity (see, e.g., EL Remarks to §§12, 42, 81, 87, 88; PhG §79). The natures of the determinations themselves drive or force them to pass into their opposites. This sense of necessity —the idea that the method involves being forced from earlier moments to later ones—leads Hegel to regard his dialectics as a kind of logic . As he says in the Phenomenology , the method’s “proper exposition belongs to logic” (PhG-M §48). Necessity—the sense of being driven or forced to conclusions—is the hallmark of “logic” in Western philosophy.

Second, because the form or determination that arises is the result of the self-sublation of the determination from the moment of understanding, there is no need for some new idea to show up from the outside. Instead, the transition to the new determination or form is necessitated by earlier moments and hence grows out of the process itself. Unlike in Plato’s arbitrary dialectics, then—which must wait around until some other idea comes in from the outside—in Hegel’s dialectics “nothing extraneous is introduced”, as he says (SL-M 54; cf. SL-dG 33). His dialectics is driven by the nature, immanence or “inwardness” of its own content (SL-M 54; cf. SL-dG 33; cf. PR §31). As he puts it, dialectics is “the principle through which alone immanent coherence and necessity enter into the content of science” (EL-GSH Remark to §81).

Third, because later determinations “sublate” earlier determinations, the earlier determinations are not completely cancelled or negated. On the contrary, the earlier determinations are preserved in the sense that they remain in effect within the later determinations. When Being-for-itself, for instance, is introduced in the logic as the first concept of ideality or universality and is defined by embracing a set of “something-others”, Being-for-itself replaces the something-others as the new concept, but those something-others remain active within the definition of the concept of Being-for-itself. The something-others must continue to do the work of picking out individual somethings before the concept of Being-for-itself can have its own definition as the concept that gathers them up. Being-for-itself replaces the something-others, but it also preserves them, because its definition still requires them to do their work of picking out individual somethings (EL §§95–6).

The concept of “apple”, for example, as a Being-for-itself, would be defined by gathering up individual “somethings” that are the same as one another (as apples). Each individual apple can be what it is (as an apple) only in relation to an “other” that is the same “something” that it is (i.e., an apple). That is the one-sidedness or restrictedness that leads each “something” to pass into its “other” or opposite. The “somethings” are thus both “something-others”. Moreover, their defining processes lead to an endless process of passing back and forth into one another: one “something” can be what it is (as an apple) only in relation to another “something” that is the same as it is, which, in turn, can be what it is (an apple) only in relation to the other “something” that is the same as it is, and so on, back and forth, endlessly (cf. EL §95). The concept of “apple”, as a Being-for-itself, stops that endless, passing-over process by embracing or including the individual something-others (the apples) in its content. It grasps or captures their character or quality as apples . But the “something-others” must do their work of picking out and separating those individual items (the apples) before the concept of “apple”—as the Being-for-itself—can gather them up for its own definition. We can picture the concept of Being-for-itself like this:

Later concepts thus replace, but also preserve, earlier concepts.

Fourth, later concepts both determine and also surpass the limits or finitude of earlier concepts. Earlier determinations sublate themselves —they pass into their others because of some weakness, one-sidedness or restrictedness in their own definitions. There are thus limitations in each of the determinations that lead them to pass into their opposites. As Hegel says, “that is what everything finite is: its own sublation” (EL-GSH Remark to §81). Later determinations define the finiteness of the earlier determinations. From the point of view of the concept of Being-for-itself, for instance, the concept of a “something-other” is limited or finite: although the something-others are supposed to be the same as one another, the character of their sameness (e.g., as apples) is captured only from above, by the higher-level, more universal concept of Being-for-itself. Being-for-itself reveals the limitations of the concept of a “something-other”. It also rises above those limitations, since it can do something that the concept of a something-other cannot do. Dialectics thus allows us to get beyond the finite to the universal. As Hegel puts it, “all genuine, nonexternal elevation above the finite is to be found in this principle [of dialectics]” (EL-GSH Remark to §81).

Fifth, because the determination in the speculative moment grasps the unity of the first two moments, Hegel’s dialectical method leads to concepts or forms that are increasingly comprehensive and universal. As Hegel puts it, the result of the dialectical process

is a new concept but one higher and richer than the preceding—richer because it negates or opposes the preceding and therefore contains it, and it contains even more than that, for it is the unity of itself and its opposite. (SL-dG 33; cf. SL-M 54)

Like Being-for-itself, later concepts are more universal because they unify or are built out of earlier determinations, and include those earlier determinations as part of their definitions. Indeed, many other concepts or determinations can also be depicted as literally surrounding earlier ones (cf. Maybee 2009: 73, 100, 112, 156, 193, 214, 221, 235, 458).

Finally, because the dialectical process leads to increasing comprehensiveness and universality, it ultimately produces a complete series, or drives “to completion” (SL-dG 33; cf. SL-M 54; PhG §79). Dialectics drives to the “Absolute”, to use Hegel’s term, which is the last, final, and completely all-encompassing or unconditioned concept or form in the relevant subject matter under discussion (logic, phenomenology, ethics/politics and so on). The “Absolute” concept or form is unconditioned because its definition or determination contains all the other concepts or forms that were developed earlier in the dialectical process for that subject matter. Moreover, because the process develops necessarily and comprehensively through each concept, form or determination, there are no determinations that are left out of the process. There are therefore no left-over concepts or forms—concepts or forms outside of the “Absolute”—that might “condition” or define it. The “Absolute” is thus unconditioned because it contains all of the conditions in its content, and is not conditioned by anything else outside of it. This Absolute is the highest concept or form of universality for that subject matter. It is the thought or concept of the whole conceptual system for the relevant subject matter. We can picture the Absolute Idea (EL §236), for instance—which is the “Absolute” for logic—as an oval that is filled up with and surrounds numerous, embedded rings of smaller ovals and circles, which represent all of the earlier and less universal determinations from the logical development (cf. Maybee 2009: 30, 600):

Since the “Absolute” concepts for each subject matter lead into one another, when they are taken together, they constitute Hegel’s entire philosophical system, which, as Hegel says, “presents itself therefore as a circle of circles” (EL-GSH §15). We can picture the entire system like this (cf. Maybee 2009: 29):

Together, Hegel believes, these characteristics make his dialectical method genuinely scientific. As he says, “the dialectical constitutes the moving soul of scientific progression” (EL-GSH Remark to §81). He acknowledges that a description of the method can be more or less complete and detailed, but because the method or progression is driven only by the subject matter itself, this dialectical method is the “only true method” (SL-M 54; SL-dG 33).

So far, we have seen how Hegel describes his dialectical method, but we have yet to see how we might read this method into the arguments he offers in his works. Scholars often use the first three stages of the logic as the “textbook example” (Forster 1993: 133) to illustrate how Hegel’s dialectical method should be applied to his arguments. The logic begins with the simple and immediate concept of pure Being, which is said to illustrate the moment of the understanding. We can think of Being here as a concept of pure presence. It is not mediated by any other concept—or is not defined in relation to any other concept—and so is undetermined or has no further determination (EL §86; SL-M 82; SL-dG 59). It asserts bare presence, but what that presence is like has no further determination. Because the thought of pure Being is undetermined and so is a pure abstraction, however, it is really no different from the assertion of pure negation or the absolutely negative (EL §87). It is therefore equally a Nothing (SL-M 82; SL-dG 59). Being’s lack of determination thus leads it to sublate itself and pass into the concept of Nothing (EL §87; SL-M 82; SL-dG 59), which illustrates the dialectical moment.

But if we focus for a moment on the definitions of Being and Nothing themselves, their definitions have the same content. Indeed, both are undetermined, so they have the same kind of undefined content. The only difference between them is “something merely meant ” (EL-GSH Remark to §87), namely, that Being is an undefined content, taken as or meant to be presence, while Nothing is an undefined content, taken as or meant to be absence. The third concept of the logic—which is used to illustrate the speculative moment—unifies the first two moments by capturing the positive result of—or the conclusion that we can draw from—the opposition between the first two moments. The concept of Becoming is the thought of an undefined content, taken as presence (Being) and then taken as absence (Nothing), or taken as absence (Nothing) and then taken as presence (Being). To Become is to go from Being to Nothing or from Nothing to Being, or is, as Hegel puts it, “the immediate vanishing of the one in the other” (SL-M 83; cf. SL-dG 60). The contradiction between Being and Nothing thus is not a reductio ad absurdum , or does not lead to the rejection of both concepts and hence to nothingness—as Hegel had said Plato’s dialectics does (SL-M 55–6; SL-dG 34–5)—but leads to a positive result, namely, to the introduction of a new concept—the synthesis—which unifies the two, earlier, opposed concepts.

We can also use the textbook Being-Nothing-Becoming example to illustrate Hegel’s concept of aufheben (to sublate), which, as we saw, means to cancel (or negate) and to preserve at the same time. Hegel says that the concept of Becoming sublates the concepts of Being and Nothing (SL-M 105; SL-dG 80). Becoming cancels or negates Being and Nothing because it is a new concept that replaces the earlier concepts; but it also preserves Being and Nothing because it relies on those earlier concepts for its own definition. Indeed, it is the first concrete concept in the logic. Unlike Being and Nothing, which had no definition or determination as concepts themselves and so were merely abstract (SL-M 82–3; SL-dG 59–60; cf. EL Addition to §88), Becoming is a “ determinate unity in which there is both Being and Nothing” (SL-M 105; cf. SL-dG 80). Becoming succeeds in having a definition or determination because it is defined by, or piggy-backs on, the concepts of Being and Nothing.

This “textbook” Being-Nothing-Becoming example is closely connected to the traditional idea that Hegel’s dialectics follows a thesis-antithesis-synthesis pattern, which, when applied to the logic, means that one concept is introduced as a “thesis” or positive concept, which then develops into a second concept that negates or is opposed to the first or is its “antithesis”, which in turn leads to a third concept, the “synthesis”, that unifies the first two (see, e.g., McTaggert 1964 [1910]: 3–4; Mure 1950: 302; Stace, 1955 [1924]: 90–3, 125–6; Kosek 1972: 243; E. Harris 1983: 93–7; Singer 1983: 77–79). Versions of this interpretation of Hegel’s dialectics continue to have currency (e.g., Forster 1993: 131; Stewart 2000: 39, 55; Fritzman 2014: 3–5). On this reading, Being is the positive moment or thesis, Nothing is the negative moment or antithesis, and Becoming is the moment of aufheben or synthesis—the concept that cancels and preserves, or unifies and combines, Being and Nothing.

We must be careful, however, not to apply this textbook example too dogmatically to the rest of Hegel’s logic or to his dialectical method more generally (for a classic criticism of the thesis-antithesis-synthesis reading of Hegel’s dialectics, see Mueller 1958). There are other places where this general pattern might describe some of the transitions from stage to stage, but there are many more places where the development does not seem to fit this pattern very well. One place where the pattern seems to hold, for instance, is where the Measure (EL §107)—as the combination of Quality and Quantity—transitions into the Measureless (EL §107), which is opposed to it, which then in turn transitions into Essence, which is the unity or combination of the two earlier sides (EL §111). This series of transitions could be said to follow the general pattern captured by the “textbook example”: Measure would be the moment of the understanding or thesis, the Measureless would be the dialectical moment or antithesis, and Essence would be the speculative moment or synthesis that unifies the two earlier moments. However, before the transition to Essence takes place, the Measureless itself is redefined as a Measure (EL §109)—undercutting a precise parallel with the textbook Being-Nothing-Becoming example, since the transition from Measure to Essence would not follow a Measure-Measureless-Essence pattern, but rather a Measure-(Measureless?)-Measure-Essence pattern.

Other sections of Hegel’s philosophy do not fit the triadic, textbook example of Being-Nothing-Becoming at all, as even interpreters who have supported the traditional reading of Hegel’s dialectics have noted. After using the Being-Nothing-Becoming example to argue that Hegel’s dialectical method consists of “triads” whose members “are called the thesis, antithesis, synthesis” (Stace 1955 [1924]: 93), W.T. Stace, for instance, goes on to warn us that Hegel does not succeed in applying this pattern throughout the philosophical system. It is hard to see, Stace says, how the middle term of some of Hegel’s triads are the opposites or antitheses of the first term, “and there are even ‘triads’ which contain four terms!” (Stace 1955 [1924]: 97). As a matter of fact, one section of Hegel’s logic—the section on Cognition—violates the thesis-antithesis-synthesis pattern because it has only two sub-divisions, rather than three. “The triad is incomplete”, Stace complains. “There is no third. Hegel here abandons the triadic method. Nor is any explanation of his having done so forthcoming” (Stace 1955 [1924]: 286; cf. McTaggart 1964 [1910]: 292).

Interpreters have offered various solutions to the complaint that Hegel’s dialectics sometimes seems to violate the triadic form. Some scholars apply the triadic form fairly loosely across several stages (e.g. Burbidge 1981: 43–5; Taylor 1975: 229–30). Others have applied Hegel’s triadic method to whole sections of his philosophy, rather than to individual stages. For G.R.G. Mure, for instance, the section on Cognition fits neatly into a triadic, thesis-antithesis-synthesis account of dialectics because the whole section is itself the antithesis of the previous section of Hegel’s logic, the section on Life (Mure 1950: 270). Mure argues that Hegel’s triadic form is easier to discern the more broadly we apply it. “The triadic form appears on many scales”, he says, “and the larger the scale we consider the more obvious it is” (Mure 1950: 302).

Scholars who interpret Hegel’s description of dialectics on a smaller scale—as an account of how to get from stage to stage—have also tried to explain why some sections seem to violate the triadic form. J.N. Findlay, for instance—who, like Stace, associates dialectics “with the triad , or with triplicity ”—argues that stages can fit into that form in “more than one sense” (Findlay 1962: 66). The first sense of triplicity echoes the textbook, Being-Nothing-Becoming example. In a second sense, however, Findlay says, the dialectical moment or “contradictory breakdown” is not itself a separate stage, or “does not count as one of the stages”, but is a transition between opposed, “but complementary”, abstract stages that “are developed more or less concurrently” (Findlay 1962: 66). This second sort of triplicity could involve any number of stages: it “could readily have been expanded into a quadruplicity, a quintuplicity and so forth” (Findlay 1962: 66). Still, like Stace, he goes on to complain that many of the transitions in Hegel’s philosophy do not seem to fit the triadic pattern very well. In some triads, the second term is “the direct and obvious contrary of the first”—as in the case of Being and Nothing. In other cases, however, the opposition is, as Findlay puts it, “of a much less extreme character” (Findlay 1962: 69). In some triads, the third term obviously mediates between the first two terms. In other cases, however, he says, the third term is just one possible mediator or unity among other possible ones; and, in yet other cases, “the reconciling functions of the third member are not at all obvious” (Findlay 1962: 70).

Let us look more closely at one place where the “textbook example” of Being-Nothing-Becoming does not seem to describe the dialectical development of Hegel’s logic very well. In a later stage of the logic, the concept of Purpose goes through several iterations, from Abstract Purpose (EL §204), to Finite or Immediate Purpose (EL §205), and then through several stages of a syllogism (EL §206) to Realized Purpose (EL §210). Abstract Purpose is the thought of any kind of purposiveness, where the purpose has not been further determined or defined. It includes not just the kinds of purposes that occur in consciousness, such as needs or drives, but also the “internal purposiveness” or teleological view proposed by the ancient Greek philosopher, Aristotle (see entry on Aristotle ; EL Remark to §204), according to which things in the world have essences and aim to achieve (or have the purpose of living up to) their essences. Finite Purpose is the moment in which an Abstract Purpose begins to have a determination by fixing on some particular material or content through which it will be realized (EL §205). The Finite Purpose then goes through a process in which it, as the Universality, comes to realize itself as the Purpose over the particular material or content (and hence becomes Realized Purpose) by pushing out into Particularity, then into Singularity (the syllogism U-P-S), and ultimately into ‘out-thereness,’ or into individual objects out there in the world (EL §210; cf. Maybee 2009: 466–493).

Hegel’s description of the development of Purpose does not seem to fit the textbook Being-Nothing-Becoming example or the thesis-antithesis-synthesis model. According to the example and model, Abstract Purpose would be the moment of understanding or thesis, Finite Purpose would be the dialectical moment or antithesis, and Realized Purpose would be the speculative moment or synthesis. Although Finite Purpose has a different determination from Abstract Purpose (it refines the definition of Abstract Purpose), it is hard to see how it would qualify as strictly “opposed” to or as the “antithesis” of Abstract Purpose in the way that Nothing is opposed to or is the antithesis of Being.

There is an answer, however, to the criticism that many of the determinations are not “opposites” in a strict sense. The German term that is translated as “opposite” in Hegel’s description of the moments of dialectics (EL §§81, 82)— entgegensetzen —has three root words: setzen (“to posit or set”), gegen , (“against”), and the prefix ent -, which indicates that something has entered into a new state. The verb entgegensetzen can therefore literally be translated as “to set over against”. The “ engegengesetzte ” into which determinations pass, then, do not need to be the strict “opposites” of the first, but can be determinations that are merely “set against” or are different from the first ones. And the prefix ent -, which suggests that the first determinations are put into a new state, can be explained by Hegel’s claim that the finite determinations from the moment of understanding sublate (cancel but also preserve) themselves (EL §81): later determinations put earlier determinations into a new state by preserving them.

At the same time, there is a technical sense in which a later determination would still be the “opposite” of the earlier determination. Since the second determination is different from the first one, it is the logical negation of the first one, or is not -the-first-determination. If the first determination is “e”, for instance, because the new determination is different from that one, the new one is “not-e” (Kosek 1972: 240). Since Finite Purpose, for instance, has a definition or determination that is different from the definition that Abstract Purpose has, it is not -Abstract-Purpose, or is the negation or opposite of Abstract Purpose in that sense. There is therefore a technical, logical sense in which the second concept or form is the “opposite” or negation of—or is “not”—the first one—though, again, it need not be the “opposite” of the first one in a strict sense.

Other problems remain, however. Because the concept of Realized Purpose is defined through a syllogistic process, it is itself the product of several stages of development (at least four, by my count, if Realized Purpose counts as a separate determination), which would seem to violate a triadic model. Moreover, the concept of Realized Purpose does not, strictly speaking, seem to be the unity or combination of Abstract Purpose and Finite Purpose. Realized Purpose is the result of (and so unifies) the syllogistic process of Finite Purpose, through which Finite Purpose focuses on and is realized in a particular material or content. Realized Purpose thus seems to be a development of Finite Purpose, rather than a unity or combination of Abstract Purpose and Finite Purpose, in the way that Becoming can be said to be the unity or combination of Being and Nothing.

These sorts of considerations have led some scholars to interpret Hegel’s dialectics in a way that is implied by a more literal reading of his claim, in the Encyclopaedia Logic , that the three “sides” of the form of logic—namely, the moment of understanding, the dialectical moment, and the speculative moment—“are moments of each [or every; jedes ] logically-real , that is each [or every; jedes ] concept” (EL Remark to §79; this is an alternative translation). The quotation suggests that each concept goes through all three moments of the dialectical process—a suggestion reinforced by Hegel’s claim, in the Phenomenology , that the result of the process of determinate negation is that “a new form has thereby immediately arisen” (PhG-M §79). According to this interpretation, the three “sides” are not three different concepts or forms that are related to one another in a triad—as the textbook Being-Nothing-Becoming example suggests—but rather different momentary sides or “determinations” in the life, so to speak, of each concept or form as it transitions to the next one. The three moments thus involve only two concepts or forms: the one that comes first, and the one that comes next (examples of philosophers who interpret Hegel’s dialectics in this second way include Maybee 2009; Priest 1989: 402; Rosen 2014: 122, 132; and Winfield 1990: 56).

For the concept of Being, for example, its moment of understanding is its moment of stability, in which it is asserted to be pure presence. This determination is one-sided or restricted however, because, as we saw, it ignores another aspect of Being’s definition, namely, that Being has no content or determination, which is how Being is defined in its dialectical moment. Being thus sublates itself because the one-sidedness of its moment of understanding undermines that determination and leads to the definition it has in the dialectical moment. The speculative moment draws out the implications of these moments: it asserts that Being (as pure presence) implies nothing. It is also the “unity of the determinations in their comparison [ Entgegensetzung ]” (EL §82; alternative translation): since it captures a process from one to the other, it includes Being’s moment of understanding (as pure presence) and dialectical moment (as nothing or undetermined), but also compares those two determinations, or sets (- setzen ) them up against (- gegen ) each other. It even puts Being into a new state (as the prefix ent - suggests) because the next concept, Nothing, will sublate (cancel and preserve) Being.

The concept of Nothing also has all three moments. When it is asserted to be the speculative result of the concept of Being, it has its moment of understanding or stability: it is Nothing, defined as pure absence, as the absence of determination. But Nothing’s moment of understanding is also one-sided or restricted: like Being, Nothing is also an undefined content, which is its determination in its dialectical moment. Nothing thus sublates itself : since it is an undefined content , it is not pure absence after all, but has the same presence that Being did. It is present as an undefined content . Nothing thus sublates Being: it replaces (cancels) Being, but also preserves Being insofar as it has the same definition (as an undefined content) and presence that Being had. We can picture Being and Nothing like this (the circles have dashed outlines to indicate that, as concepts, they are each undefined; cf. Maybee 2009: 51):

In its speculative moment, then, Nothing implies presence or Being, which is the “unity of the determinations in their comparison [ Entgegensetzung ]” (EL §82; alternative translation), since it both includes but—as a process from one to the other—also compares the two earlier determinations of Nothing, first, as pure absence and, second, as just as much presence.

The dialectical process is driven to the next concept or form—Becoming—not by a triadic, thesis-antithesis-synthesis pattern, but by the one-sidedness of Nothing—which leads Nothing to sublate itself—and by the implications of the process so far. Since Being and Nothing have each been exhaustively analyzed as separate concepts, and since they are the only concepts in play, there is only one way for the dialectical process to move forward: whatever concept comes next will have to take account of both Being and Nothing at the same time. Moreover, the process revealed that an undefined content taken to be presence (i.e., Being) implies Nothing (or absence), and that an undefined content taken to be absence (i.e., Nothing) implies presence (i.e., Being). The next concept, then, takes Being and Nothing together and draws out those implications—namely, that Being implies Nothing, and that Nothing implies Being. It is therefore Becoming, defined as two separate processes: one in which Being becomes Nothing, and one in which Nothing becomes Being. We can picture Becoming this way (cf. Maybee 2009: 53):

In a similar way, a one-sidedness or restrictedness in the determination of Finite Purpose together with the implications of earlier stages leads to Realized Purpose. In its moment of understanding, Finite Purpose particularizes into (or presents) its content as “ something-presupposed ” or as a pre-given object (EL §205). I go to a restaurant for the purpose of having dinner, for instance, and order a salad. My purpose of having dinner particularizes as a pre-given object—the salad. But this object or particularity—e.g. the salad—is “inwardly reflected” (EL §205): it has its own content—developed in earlier stages—which the definition of Finite Purpose ignores. We can picture Finite Purpose this way:

In the dialectical moment, Finite Purpose is determined by the previously ignored content, or by that other content. The one-sidedness of Finite Purpose requires the dialectical process to continue through a series of syllogisms that determines Finite Purpose in relation to the ignored content. The first syllogism links the Finite Purpose to the first layer of content in the object: the Purpose or universality (e.g., dinner) goes through the particularity (e.g., the salad) to its content, the singularity (e.g., lettuce as a type of thing)—the syllogism U-P-S (EL §206). But the particularity (e.g., the salad) is itself a universality or purpose, “which at the same time is a syllogism within itself [ in sich ]” (EL Remark to §208; alternative translation), in relation to its own content. The salad is a universality/purpose that particularizes as lettuce (as a type of thing) and has its singularity in this lettuce here—a second syllogism, U-P-S. Thus, the first singularity (e.g., “lettuce” as a type of thing)—which, in this second syllogism, is the particularity or P —“ judges ” (EL §207) or asserts that “ U is S ”: it says that “lettuce” as a universality ( U ) or type of thing is a singularity ( S ), or is “this lettuce here”, for instance. This new singularity (e.g. “this lettuce here”) is itself a combination of subjectivity and objectivity (EL §207): it is an Inner or identifying concept (“lettuce”) that is in a mutually-defining relationship (the circular arrow) with an Outer or out-thereness (“this here”) as its content. In the speculative moment, Finite Purpose is determined by the whole process of development from the moment of understanding—when it is defined by particularizing into a pre-given object with a content that it ignores—to its dialectical moment—when it is also defined by the previously ignored content. We can picture the speculative moment of Finite Purpose this way:

Finite Purpose’s speculative moment leads to Realized Purpose. As soon as Finite Purpose presents all the content, there is a return process (a series of return arrows) that establishes each layer and redefines Finite Purpose as Realized Purpose. The presence of “this lettuce here” establishes the actuality of “lettuce” as a type of thing (an Actuality is a concept that captures a mutually-defining relationship between an Inner and an Outer [EL §142]), which establishes the “salad”, which establishes “dinner” as the Realized Purpose over the whole process. We can picture Realized Purpose this way:

If Hegel’s account of dialectics is a general description of the life of each concept or form, then any section can include as many or as few stages as the development requires. Instead of trying to squeeze the stages into a triadic form (cf. Solomon 1983: 22)—a technique Hegel himself rejects (PhG §50; cf. section 3 )—we can see the process as driven by each determination on its own account: what it succeeds in grasping (which allows it to be stable, for a moment of understanding), what it fails to grasp or capture (in its dialectical moment), and how it leads (in its speculative moment) to a new concept or form that tries to correct for the one-sidedness of the moment of understanding. This sort of process might reveal a kind of argument that, as Hegel had promised, might produce a comprehensive and exhaustive exploration of every concept, form or determination in each subject matter, as well as raise dialectics above a haphazard analysis of various philosophical views to the level of a genuine science.

We can begin to see why Hegel was motivated to use a dialectical method by examining the project he set for himself, particularly in relation to the work of David Hume and Immanuel Kant (see entries on Hume and Kant ). Hume had argued against what we can think of as the naïve view of how we come to have scientific knowledge. According to the naïve view, we gain knowledge of the world by using our senses to pull the world into our heads, so to speak. Although we may have to use careful observations and do experiments, our knowledge of the world is basically a mirror or copy of what the world is like. Hume argued, however, that naïve science’s claim that our knowledge corresponds to or copies what the world is like does not work. Take the scientific concept of cause, for instance. According to that concept of cause, to say that one event causes another is to say that there is a necessary connection between the first event (the cause) and the second event (the effect), such that, when the first event happens, the second event must also happen. According to naïve science, when we claim (or know) that some event causes some other event, our claim mirrors or copies what the world is like. It follows that the necessary, causal connection between the two events must itself be out there in the world. However, Hume argued, we never observe any such necessary causal connection in our experience of the world, nor can we infer that one exists based on our reasoning (see Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature , Book I, Part III, Section II; Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding , Section VII, Part I). There is nothing in the world itself that our idea of cause mirrors or copies.

Kant thought Hume’s argument led to an unacceptable, skeptical conclusion, and he rejected Hume’s own solution to the skepticism (see Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason , B5, B19–20). Hume suggested that our idea of causal necessity is grounded merely in custom or habit, since it is generated by our own imaginations after repeated observations of one sort of event following another sort of event (see Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature , Book I, Section VI; Hegel also rejected Hume’s solution, see EL §39). For Kant, science and knowledge should be grounded in reason, and he proposed a solution that aimed to reestablish the connection between reason and knowledge that was broken by Hume’s skeptical argument. Kant’s solution involved proposing a Copernican revolution in philosophy ( Critique of Pure Reason , Bxvi). Nicholas Copernicus was the Polish astronomer who said that the earth revolves around the sun, rather than the other way around. Kant proposed a similar solution to Hume’s skepticism. Naïve science assumes that our knowledge revolves around what the world is like, but, Hume’s criticism argued, this view entails that we cannot then have knowledge of scientific causes through reason. We can reestablish a connection between reason and knowledge, however, Kant suggested, if we say—not that knowledge revolves around what the world is like—but that knowledge revolves around what we are like . For the purposes of our knowledge, Kant said, we do not revolve around the world—the world revolves around us. Because we are rational creatures, we share a cognitive structure with one another that regularizes our experiences of the world. This intersubjectively shared structure of rationality—and not the world itself—grounds our knowledge.

However, Kant’s solution to Hume’s skepticism led to a skeptical conclusion of its own that Hegel rejected. While the intersubjectively shared structure of our reason might allow us to have knowledge of the world from our perspective, so to speak, we cannot get outside of our mental, rational structures to see what the world might be like in itself. As Kant had to admit, according to his theory, there is still a world in itself or “Thing-in-itself” ( Ding an sich ) about which we can know nothing (see, e.g., Critique of Pure Reason , Bxxv–xxvi). Hegel rejected Kant’s skeptical conclusion that we can know nothing about the world- or Thing-in-itself, and he intended his own philosophy to be a response to this view (see, e.g., EL §44 and the Remark to §44).

How did Hegel respond to Kant’s skepticism—especially since Hegel accepted Kant’s Copernican revolution, or Kant’s claim that we have knowledge of the world because of what we are like, because of our reason? How, for Hegel, can we get out of our heads to see the world as it is in itself? Hegel’s answer is very close to the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle’s response to Plato. Plato argued that we have knowledge of the world only through the Forms. The Forms are perfectly universal, rational concepts or ideas. Because the world is imperfect, however, Plato exiled the Forms to their own realm. Although things in the world get their definitions by participating in the Forms, those things are, at best, imperfect copies of the universal Forms (see, e.g., Parmenides 131–135a). The Forms are therefore not in this world, but in a separate realm of their own. Aristotle argued, however, that the world is knowable not because things in the world are imperfect copies of the Forms, but because the Forms are in things themselves as the defining essences of those things (see, e.g., De Anima [ On the Soul ], Book I, Chapter 1 [403a26–403b18]; Metaphysics , Book VII, Chapter 6 [1031b6–1032a5] and Chapter 8 [1033b20–1034a8]).

In a similar way, Hegel’s answer to Kant is that we can get out of our heads to see what the world is like in itself—and hence can have knowledge of the world in itself—because the very same rationality or reason that is in our heads is in the world itself . As Hegel apparently put it in a lecture, the opposition or antithesis between the subjective and objective disappears by saying, as the Ancients did,

that nous governs the world, or by our own saying that there is reason in the world, by which we mean that reason is the soul of the world, inhabits it, and is immanent in it, as it own, innermost nature, its universal. (EL-GSH Addition 1 to §24)

Hegel used an example familiar from Aristotle’s work to illustrate this view:

“to be an animal”, the kind considered as the universal, pertains to the determinate animal and constitutes its determinate essentiality. If we were to deprive a dog of its animality we could not say what it is. (EL-GSH Addition 1 to §24; cf. SL-dG 16–17, SL-M 36-37)

Kant’s mistake, then, was that he regarded reason or rationality as only in our heads, Hegel suggests (EL §§43–44), rather than in both us and the world itself (see also below in this section and section 4 ). We can use our reason to have knowledge of the world because the very same reason that is in us, is in the world itself as it own defining principle. The rationality or reason in the world makes reality understandable, and that is why we can have knowledge of, or can understand, reality with our rationality. Dialectics—which is Hegel’s account of reason—characterizes not only logic, but also “everything true in general” (EL Remark to §79).