Rhetorical Analysis of an Image

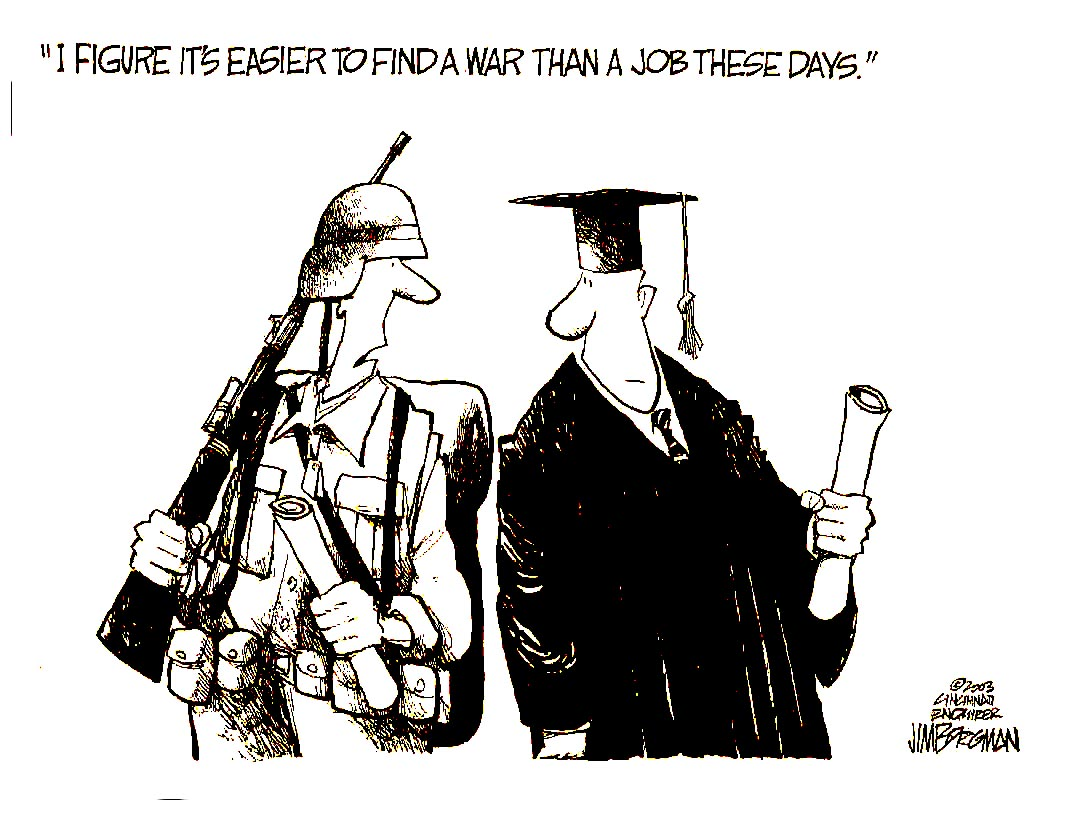

The political cartoon drawn by Jim Borgman eloquently illustrates the problems faced by many young American people nowadays. In particular, it shows that they often do not have any employment opportunities, and some may be forced to join the Army hoping that it can create at least some opportunities for them.

Apart from that, this image can be aimed at criticizing the policies of the government that attaches more importance to military spending, rather than economic development of the country and welfare of its citizens. These are the main argument that the cartoonist puts forward.

By using both imagery and verbal elements, Borgman succeeds in making a very powerful statement about the life contemporary society in which the feeling of insecurity is probably the most dominant one.

The key topic that the author explores is the lack of opportunities for American people, especially those ones who are relatively young. This cartoon was created in 2003 at the time when economic problems began to manifest themselves, and the country was conducting several military operations abroad.

Yet, nowadays when the impacts of recession have not been fully overcome, this issue is even more important for a greater number of people, namely school and college graduates. They may not always be able to achieve success in their social life. The audience of this cartoon is difficult to define, because it can include every person who is interested in the political, social, and economic life of the country.

Yet, one cannot say that there are distinct demographic characteristics of the audience. Overall, it is possible to argue that Jim Borgman supports left-wing ideology which emphasizes the necessity for social change and egalitarian relations in the society 1 . This cartoonist is extremely concerned with future development of American society.

This cartoon is a single-frame image in which the author depicts two characters; one of them is a soldier holding an assault rifle, while the other one is probably a college graduate 2 . It should be noted that Jim Borgman does not portray their faces in much detail. One can only see that these are male characters.

Overall, one can argue that this cartoon is quite realistic, especially as far as clothing of the characters is concerned. This description is supposed to show that these people represent two different social classes. One of them is a former student who is holding either his diploma or resume while the other person is a young man who preferred military career.

They have to represent different options that are available to young people in the contemporary United States. In particular, some of them may choose to get education while other may prefer the Army as a way of climbing social ladder. The main issue is that none of these options can guarantee success to a person.

The author relies on both word and image. The most important element is the textual message included into this cartoon. In particular, the soldier says, “I figure it’s easier to find a war than a job these days”. To a great extent, this sentence can be viewed as a title of the cartoon. This statement shows how difficult it is for a person find ones niche in the contemporary workforce.

This is the most obvious argument that this image contains. Jim Borgman’s tone is both comic and serious at the same time because the author portrays characters in a caricatural way, but this image also makes a viewer feel empathy of these people. The author does not refer to any particular person or specific event, but one can understand that the author describes the life of contemporary Americans.

Apart from that, it is possible to see a hidden or implied message in this cartoon. To a great extent, it is aimed at showing that the government is too concerned with military strength of the country, but not much attention is being paid to the economic welfare of citizens.

As a result, college graduates are often unable to find a job that can best suits their talents and education. Overall, Jim Borgman has been able to show the sense of insecurity that these people experience. To some degree, this situation can be explained by the policies and strategies of the state.

Thus, one can say that Jim Borgman can make several rhetorical statements with the help of this cartoon. Although the author does not calls for a specific change, he skillfully shows that current situation leaves much to be desired.

On the whole, the image drawn by Jim Borgman is excellent example of how visual and verbal messages can convey a deep rhetorical argument that can pose many thought-provoking questions to a person.

The cartoonist relies on both visual and verbal elements in order to express his argument. Through this cartoon, the author highlights some of the most important problems that can be encountered by young people. So, this image can be regarded as an excellent example of a political cartoon.

Picture 1. The cartoon by Jim Borgman

Bibliography

Borgman, Jim. I figure it’s easier to find a war than a job these days . Cartoon. 2003.

Accessed from http://paulocoelhoblog.com/images/image-of-the-day/Borgman.jpg

Hess Stephen and Sandy Northrop. American Political Cartoons: The Evolution of a National Identity, 1754-2010 . New York: Transaction Publishers, 2010.

1 Hess Stephen and Sandy Northrop. American Political Cartoons: The Evolution of a National Identity, 1754-2010 ( New York: Transaction Publishers, 2010), 134.

2 Please refer to the Appendixes, Picture 1.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, November 23). Rhetorical Analysis of an Image. https://ivypanda.com/essays/rhetorical-analysis-of-an-image/

"Rhetorical Analysis of an Image." IvyPanda , 23 Nov. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/rhetorical-analysis-of-an-image/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Rhetorical Analysis of an Image'. 23 November.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Rhetorical Analysis of an Image." November 23, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/rhetorical-analysis-of-an-image/.

1. IvyPanda . "Rhetorical Analysis of an Image." November 23, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/rhetorical-analysis-of-an-image/.

IvyPanda . "Rhetorical Analysis of an Image." November 23, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/rhetorical-analysis-of-an-image/.

- Naji al-Ali, a Palestinian Cartoonist and His Art

- Political Cartoons in Different Countries

- Political Cartoon on Health Care Reform in the United States

- Civil Rights Movements During 1960s

- The Boxer Rebellion in China: History and Impacts

- The role of morphemes in the English language

- How Children's Cartoons Are Politicized

- Cartoons, Young Children, and Parental Involvement

- Race and Ethnicity in Cartoons

- Satiric Cartoons on American Politics

- Role of Gender in "Mulan" by Walt Disney

- Disney's "The Little Mermaid" Adaptation

- Toy Story 1: An animation legend

- The Trilogy "Toy Story"

- Arguments in Who Framed Roger Rabbit

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a rhetorical analysis | Key concepts & examples

How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis | Key Concepts & Examples

Published on August 28, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A rhetorical analysis is a type of essay that looks at a text in terms of rhetoric. This means it is less concerned with what the author is saying than with how they say it: their goals, techniques, and appeals to the audience.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Key concepts in rhetoric, analyzing the text, introducing your rhetorical analysis, the body: doing the analysis, concluding a rhetorical analysis, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about rhetorical analysis.

Rhetoric, the art of effective speaking and writing, is a subject that trains you to look at texts, arguments and speeches in terms of how they are designed to persuade the audience. This section introduces a few of the key concepts of this field.

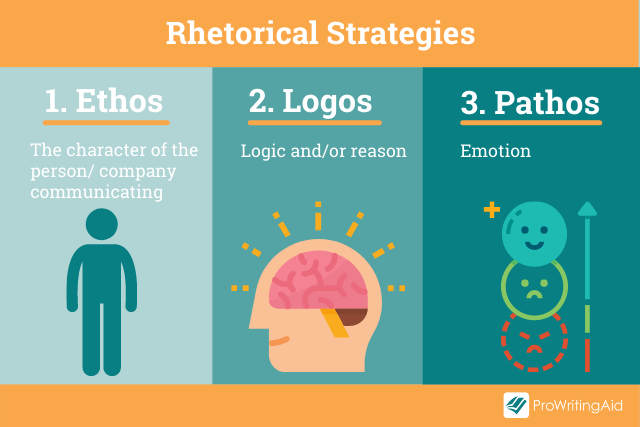

Appeals: Logos, ethos, pathos

Appeals are how the author convinces their audience. Three central appeals are discussed in rhetoric, established by the philosopher Aristotle and sometimes called the rhetorical triangle: logos, ethos, and pathos.

Logos , or the logical appeal, refers to the use of reasoned argument to persuade. This is the dominant approach in academic writing , where arguments are built up using reasoning and evidence.

Ethos , or the ethical appeal, involves the author presenting themselves as an authority on their subject. For example, someone making a moral argument might highlight their own morally admirable behavior; someone speaking about a technical subject might present themselves as an expert by mentioning their qualifications.

Pathos , or the pathetic appeal, evokes the audience’s emotions. This might involve speaking in a passionate way, employing vivid imagery, or trying to provoke anger, sympathy, or any other emotional response in the audience.

These three appeals are all treated as integral parts of rhetoric, and a given author may combine all three of them to convince their audience.

Text and context

In rhetoric, a text is not necessarily a piece of writing (though it may be this). A text is whatever piece of communication you are analyzing. This could be, for example, a speech, an advertisement, or a satirical image.

In these cases, your analysis would focus on more than just language—you might look at visual or sonic elements of the text too.

The context is everything surrounding the text: Who is the author (or speaker, designer, etc.)? Who is their (intended or actual) audience? When and where was the text produced, and for what purpose?

Looking at the context can help to inform your rhetorical analysis. For example, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech has universal power, but the context of the civil rights movement is an important part of understanding why.

Claims, supports, and warrants

A piece of rhetoric is always making some sort of argument, whether it’s a very clearly defined and logical one (e.g. in a philosophy essay) or one that the reader has to infer (e.g. in a satirical article). These arguments are built up with claims, supports, and warrants.

A claim is the fact or idea the author wants to convince the reader of. An argument might center on a single claim, or be built up out of many. Claims are usually explicitly stated, but they may also just be implied in some kinds of text.

The author uses supports to back up each claim they make. These might range from hard evidence to emotional appeals—anything that is used to convince the reader to accept a claim.

The warrant is the logic or assumption that connects a support with a claim. Outside of quite formal argumentation, the warrant is often unstated—the author assumes their audience will understand the connection without it. But that doesn’t mean you can’t still explore the implicit warrant in these cases.

For example, look at the following statement:

We can see a claim and a support here, but the warrant is implicit. Here, the warrant is the assumption that more likeable candidates would have inspired greater turnout. We might be more or less convinced by the argument depending on whether we think this is a fair assumption.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Rhetorical analysis isn’t a matter of choosing concepts in advance and applying them to a text. Instead, it starts with looking at the text in detail and asking the appropriate questions about how it works:

- What is the author’s purpose?

- Do they focus closely on their key claims, or do they discuss various topics?

- What tone do they take—angry or sympathetic? Personal or authoritative? Formal or informal?

- Who seems to be the intended audience? Is this audience likely to be successfully reached and convinced?

- What kinds of evidence are presented?

By asking these questions, you’ll discover the various rhetorical devices the text uses. Don’t feel that you have to cram in every rhetorical term you know—focus on those that are most important to the text.

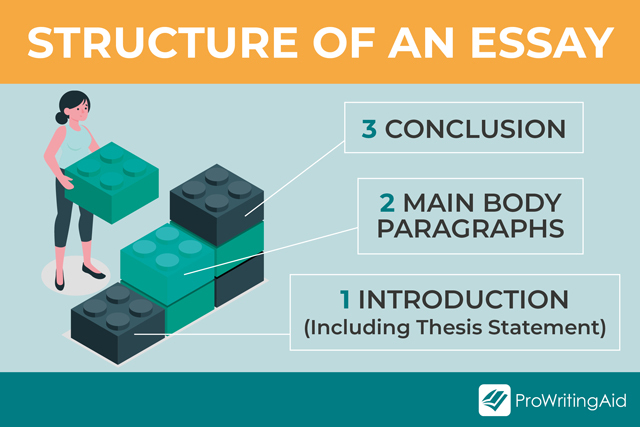

The following sections show how to write the different parts of a rhetorical analysis.

Like all essays, a rhetorical analysis begins with an introduction . The introduction tells readers what text you’ll be discussing, provides relevant background information, and presents your thesis statement .

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how an introduction works.

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech is widely regarded as one of the most important pieces of oratory in American history. Delivered in 1963 to thousands of civil rights activists outside the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the speech has come to symbolize the spirit of the civil rights movement and even to function as a major part of the American national myth. This rhetorical analysis argues that King’s assumption of the prophetic voice, amplified by the historic size of his audience, creates a powerful sense of ethos that has retained its inspirational power over the years.

The body of your rhetorical analysis is where you’ll tackle the text directly. It’s often divided into three paragraphs, although it may be more in a longer essay.

Each paragraph should focus on a different element of the text, and they should all contribute to your overall argument for your thesis statement.

Hover over the example to explore how a typical body paragraph is constructed.

King’s speech is infused with prophetic language throughout. Even before the famous “dream” part of the speech, King’s language consistently strikes a prophetic tone. He refers to the Lincoln Memorial as a “hallowed spot” and speaks of rising “from the dark and desolate valley of segregation” to “make justice a reality for all of God’s children.” The assumption of this prophetic voice constitutes the text’s strongest ethical appeal; after linking himself with political figures like Lincoln and the Founding Fathers, King’s ethos adopts a distinctly religious tone, recalling Biblical prophets and preachers of change from across history. This adds significant force to his words; standing before an audience of hundreds of thousands, he states not just what the future should be, but what it will be: “The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.” This warning is almost apocalyptic in tone, though it concludes with the positive image of the “bright day of justice.” The power of King’s rhetoric thus stems not only from the pathos of his vision of a brighter future, but from the ethos of the prophetic voice he adopts in expressing this vision.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

The conclusion of a rhetorical analysis wraps up the essay by restating the main argument and showing how it has been developed by your analysis. It may also try to link the text, and your analysis of it, with broader concerns.

Explore the example below to get a sense of the conclusion.

It is clear from this analysis that the effectiveness of King’s rhetoric stems less from the pathetic appeal of his utopian “dream” than it does from the ethos he carefully constructs to give force to his statements. By framing contemporary upheavals as part of a prophecy whose fulfillment will result in the better future he imagines, King ensures not only the effectiveness of his words in the moment but their continuing resonance today. Even if we have not yet achieved King’s dream, we cannot deny the role his words played in setting us on the path toward it.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

The goal of a rhetorical analysis is to explain the effect a piece of writing or oratory has on its audience, how successful it is, and the devices and appeals it uses to achieve its goals.

Unlike a standard argumentative essay , it’s less about taking a position on the arguments presented, and more about exploring how they are constructed.

The term “text” in a rhetorical analysis essay refers to whatever object you’re analyzing. It’s frequently a piece of writing or a speech, but it doesn’t have to be. For example, you could also treat an advertisement or political cartoon as a text.

Logos appeals to the audience’s reason, building up logical arguments . Ethos appeals to the speaker’s status or authority, making the audience more likely to trust them. Pathos appeals to the emotions, trying to make the audience feel angry or sympathetic, for example.

Collectively, these three appeals are sometimes called the rhetorical triangle . They are central to rhetorical analysis , though a piece of rhetoric might not necessarily use all of them.

In rhetorical analysis , a claim is something the author wants the audience to believe. A support is the evidence or appeal they use to convince the reader to believe the claim. A warrant is the (often implicit) assumption that links the support with the claim.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis | Key Concepts & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/rhetorical-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an argumentative essay | examples & tips, how to write a literary analysis essay | a step-by-step guide, comparing and contrasting in an essay | tips & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Rhetorical Analysis Essay

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example - Free Samples

11 min read

People also read

Rhetorical Analysis Essay - A Complete Guide With Examples

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Topics – 120+ Unique Ideas

Crafting an Effective Rhetorical Analysis Essay Outline - Free Samples!

Ethos, Pathos, and Logos - Structure, Usage & Examples

Writing a rhetorical analysis essay for academics can be really demanding for students. This type of paper requires high-level analyzing abilities and professional writing skills to be drafted effectively.

As this essay persuades the audience, it is essential to know how to take a strong stance and develop a thesis.

This article will find some examples that will help you with your rhetorical analysis essay writing effortlessly.

- 1. Good Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example

- 2. Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example AP Lang 2023

- 3. Rhetorical Analysis Essay Examples for Students

- 4. Writing a Visual Rhetorical Analysis Essay with Example

- 5. Rhetorical Analysis Essay Writing Tips

Good Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example

The step-by-step writing process of a rhetorical analysis essay is far more complicated than ordinary academic essays. This essay type critically analyzes the rhetorical means used to persuade the audience and their efficiency.

The example provided below is the best rhetorical analysis essay example:

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Sample

In this essay type, the author uses rhetorical approaches such as ethos, pathos, and logos . These approaches are then studied and analyzed deeply by the essay writers to weigh their effectiveness in delivering the message.

Let’s take a look at the following example to get a better idea;

The outline and structure of a rhetorical analysis essay are important.

According to the essay outline, the essay is divided into three sections:

- Introduction

- Ethos

- Logos

A rhetorical analysis essay outline is the same as the traditional one. The different parts of the rhetorical analysis essay are written in the following way:

Rhetorical Analysis Introduction Example

The introductory paragraph of a rhetorical analysis essay is written for the following purpose:

- To provide basic background information about the chosen author and the text.

- Identify the target audience of the essay.

An introduction for a rhetorical essay is drafted by:

- Stating an opening sentence known as the hook statement. This catchy sentence is prepared to grab the audience’s attention to the paper.

- After the opening sentence, the background information of the author and the original text are provided.

For example, a rhetorical analysis essay written by Lee Jennings on“The Right Stuff” by David Suzuki. Lee started the essay by providing the introduction in the following way:

Analysis of the Example:

- Suzuki stresses the importance of high school education. He prepares his readers for a proposal to make that education as valuable as possible.

- A rhetorical analysis can show how successful Suzuki was in using logos, pathos, and ethos. He had a strong ethos because of his reputation.

- He also used pathos to appeal to parents and educators. However, his use of logos could have been more successful.

- Here Jennings stated the background information about the text and highlighted the rhetorical techniques used and their effectiveness.

Thesis Statement Example for Rhetorical Analysis Essay

A thesis statement of a rhetorical analysis essay is the writer’s stance on the original text. It is the argument that a writer holds and proves it using the evidence from the original text.

A thesis statement for a rhetorical essay is written by analyzing the following elements of the original text:

- Diction - It refers to the author’s choice of words and the tone

- Imagery - The visual descriptive language that the author used in the content.

- Simile - The comparison of things and ideas

In Jennings's analysis of “The Right Stuff,” the thesis statement was:

Example For Rhetorical Analysis Thesis Statement

Rhetorical Analysis Body Paragraph Example

In the body paragraphs of your rhetorical analysis essay, you dissect the author's work, analyze their use of rhetorical techniques, and provide evidence to support your analysis.

Let's look at an example that analyzes the use of ethos in David Suzuki's essay:

Rhetorical Analysis Conclusion Example

All the body paragraphs lead the audience towards the conclusion.

For example, the conclusion of “The Right Stuff” is written in the following way by Jennings:

In the conclusion section, Jennings summarized the major points and restated the thesis statement to prove them.

Rhetorical Essay Example For The Right Stuff by David Suzuki

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example AP Lang 2023

Writing a rhetorical analysis for the AP Language and Composition course can be challenging. So drafting it correctly is important to earn good grades.

To make your essay effective and winning, follow the tips provided by professionals below:

Step #1: Understand the Prompt

Understanding the prompt is the first thing to produce an influential rhetorical paper. It is mandatory for this academic writing to read and understand the prompt to know what the task demands from you.

Step #2: Stick to the Format

The content for the rhetorical analysis should be appropriately organized and structured. For this purpose, a proper outline is drafted.

The rhetorical analysis essay outline divides all the information into different sections, such as the introduction, body, and conclusion. The introduction should explicitly state the background information and the thesis statement.

All the body paragraphs should start with a topic sentence to convey a claim to the readers. Provide a thorough analysis of these claims in the paragraph to support your topic sentence.

Step #3: Use Rhetorical Elements to Form an Argument

Analyze the following things in the text to form an argument for your essay:

- Language (tone and words)

- Organizational structure

- Rhetorical Appeals ( ethos, pathos, and logos)

Once you have analyzed the rhetorical appeals and other devices like imagery and diction, you can form a strong thesis statement. The thesis statement will be the foundation on which your essay will be standing.

AP Language Rhetorical Essay Sample

AP Rhetorical Analysis Essay Template

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example AP Lang

AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Examples for Students

Here are a few more examples to help the students write a rhetorical analysis essay:

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example Ethos, Pathos, Logos

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example Outline

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example College

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example APA Format

Compare and Contrast Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example

Comparative Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example

How to Start Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example High School

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example APA Sample

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example Of a Song

Florence Kelley Speech Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example MLA

Writing a Visual Rhetorical Analysis Essay with Example

The visual rhetorical analysis essay determines how pictures and images communicate messages and persuade the audience.

Usually, visual rhetorical analysis papers are written for advertisements. This is because they use strong images to convince the audience to behave in a certain way.

To draft a perfect visual rhetorical analysis essay, follow the tips below:

- Analyze the advertisement deeply and note every minor detail.

- Notice objects and colors used in the image to gather every detail.

- Determine the importance of the colors and objects and analyze why the advertiser chose the particular picture.

- See what you feel about the image.

- Consider the objective of the image. Identify the message that the image is portraying.

- Identify the targeted audience and how they respond to the picture.

An example is provided below to give students a better idea of the concept.

Simplicity Breeds Clarity Visual Rhetorical Analysis Essay Example

Rhetorical Analysis Essay Writing Tips

Follow the tips provided below to make your rhetorical writing compelling.

- Choose an engaging topic for your essay. The rhetorical analysis essay topic should be engaging to grab the reader’s attention.

- Thoroughly read the original text.

- Identify the SOAPSTone. From the text, determine the speaker, occasions, audience, purpose, subject, and tone.

- Develop a thesis statement to state your claim over the text.

- Draft a rhetorical analysis essay outline.

- Write an engaging essay introduction by giving a hook statement and background information. At the end of the introductory paragraph, state the thesis statement.

- The body paragraphs of the rhetorical essay should have a topic sentence. Also, in the paragraph, a thorough analysis should be presented.

- For writing a satisfactory rhetorical essay conclusion, restate the thesis statement and summarize the main points.

- Proofread your essay to check for mistakes in the content. Make your edits before submitting the draft.

Following the tips and the essay's correct writing procedure will guarantee success in your academics.

We have given you plenty of examples of a rhetorical analysis essay. But if you are still struggling to draft a great rhetorical analysis essay, it is suggested to take a professional’s help.

MyPerfectWords.com can assist you with all your academic assignments. The top essay writer service that we provide is reliable. If you are confused about your writing assignments and have difficulty meeting the deadline, get help from the legal essay writing service .

Hire our analytical essay writing service today at the most reasonable prices.

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Nova Allison is a Digital Content Strategist with over eight years of experience. Nova has also worked as a technical and scientific writer. She is majorly involved in developing and reviewing online content plans that engage and resonate with audiences. Nova has a passion for writing that engages and informs her readers.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Get 25% OFF new yearly plans in our Spring Sale

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

What Is a Rhetorical Analysis and How to Write a Great One

Helly Douglas

Do you have to write a rhetorical analysis essay? Fear not! We’re here to explain exactly what rhetorical analysis means, how you should structure your essay, and give you some essential “dos and don’ts.”

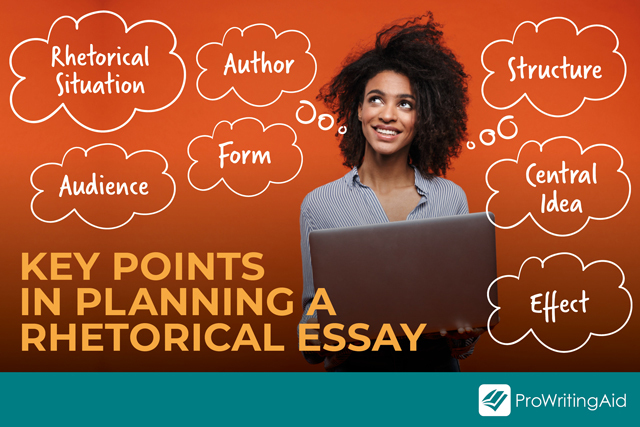

What is a Rhetorical Analysis Essay?

How do you write a rhetorical analysis, what are the three rhetorical strategies, what are the five rhetorical situations, how to plan a rhetorical analysis essay, creating a rhetorical analysis essay, examples of great rhetorical analysis essays, final thoughts.

A rhetorical analysis essay studies how writers and speakers have used words to influence their audience. Think less about the words the author has used and more about the techniques they employ, their goals, and the effect this has on the audience.

In your analysis essay, you break a piece of text (including cartoons, adverts, and speeches) into sections and explain how each part works to persuade, inform, or entertain. You’ll explore the effectiveness of the techniques used, how the argument has been constructed, and give examples from the text.

A strong rhetorical analysis evaluates a text rather than just describes the techniques used. You don’t include whether you personally agree or disagree with the argument.

Structure a rhetorical analysis in the same way as most other types of academic essays . You’ll have an introduction to present your thesis, a main body where you analyze the text, which then leads to a conclusion.

Think about how the writer (also known as a rhetor) considers the situation that frames their communication:

- Topic: the overall purpose of the rhetoric

- Audience: this includes primary, secondary, and tertiary audiences

- Purpose: there are often more than one to consider

- Context and culture: the wider situation within which the rhetoric is placed

Back in the 4th century BC, Aristotle was talking about how language can be used as a means of persuasion. He described three principal forms —Ethos, Logos, and Pathos—often referred to as the Rhetorical Triangle . These persuasive techniques are still used today.

Rhetorical Strategy 1: Ethos

Are you more likely to buy a car from an established company that’s been an important part of your community for 50 years, or someone new who just started their business?

Reputation matters. Ethos explores how the character, disposition, and fundamental values of the author create appeal, along with their expertise and knowledge in the subject area.

Aristotle breaks ethos down into three further categories:

- Phronesis: skills and practical wisdom

- Arete: virtue

- Eunoia: goodwill towards the audience

Ethos-driven speeches and text rely on the reputation of the author. In your analysis, you can look at how the writer establishes ethos through both direct and indirect means.

Rhetorical Strategy 2: Pathos

Pathos-driven rhetoric hooks into our emotions. You’ll often see it used in advertisements, particularly by charities wanting you to donate money towards an appeal.

Common use of pathos includes:

- Vivid description so the reader can imagine themselves in the situation

- Personal stories to create feelings of empathy

- Emotional vocabulary that evokes a response

By using pathos to make the audience feel a particular emotion, the author can persuade them that the argument they’re making is compelling.

Rhetorical Strategy 3: Logos

Logos uses logic or reason. It’s commonly used in academic writing when arguments are created using evidence and reasoning rather than an emotional response. It’s constructed in a step-by-step approach that builds methodically to create a powerful effect upon the reader.

Rhetoric can use any one of these three techniques, but effective arguments often appeal to all three elements.

The rhetorical situation explains the circumstances behind and around a piece of rhetoric. It helps you think about why a text exists, its purpose, and how it’s carried out.

The rhetorical situations are:

- 1) Purpose: Why is this being written? (It could be trying to inform, persuade, instruct, or entertain.)

- 2) Audience: Which groups or individuals will read and take action (or have done so in the past)?

- 3) Genre: What type of writing is this?

- 4) Stance: What is the tone of the text? What position are they taking?

- 5) Media/Visuals: What means of communication are used?

Understanding and analyzing the rhetorical situation is essential for building a strong essay. Also think about any rhetoric restraints on the text, such as beliefs, attitudes, and traditions that could affect the author's decisions.

Before leaping into your essay, it’s worth taking time to explore the text at a deeper level and considering the rhetorical situations we looked at before. Throw away your assumptions and use these simple questions to help you unpick how and why the text is having an effect on the audience.

1: What is the Rhetorical Situation?

- Why is there a need or opportunity for persuasion?

- How do words and references help you identify the time and location?

- What are the rhetoric restraints?

- What historical occasions would lead to this text being created?

2: Who is the Author?

- How do they position themselves as an expert worth listening to?

- What is their ethos?

- Do they have a reputation that gives them authority?

- What is their intention?

- What values or customs do they have?

3: Who is it Written For?

- Who is the intended audience?

- How is this appealing to this particular audience?

- Who are the possible secondary and tertiary audiences?

4: What is the Central Idea?

- Can you summarize the key point of this rhetoric?

- What arguments are used?

- How has it developed a line of reasoning?

5: How is it Structured?

- What structure is used?

- How is the content arranged within the structure?

6: What Form is Used?

- Does this follow a specific literary genre?

- What type of style and tone is used, and why is this?

- Does the form used complement the content?

- What effect could this form have on the audience?

7: Is the Rhetoric Effective?

- Does the content fulfil the author’s intentions?

- Does the message effectively fit the audience, location, and time period?

Once you’ve fully explored the text, you’ll have a better understanding of the impact it’s having on the audience and feel more confident about writing your essay outline.

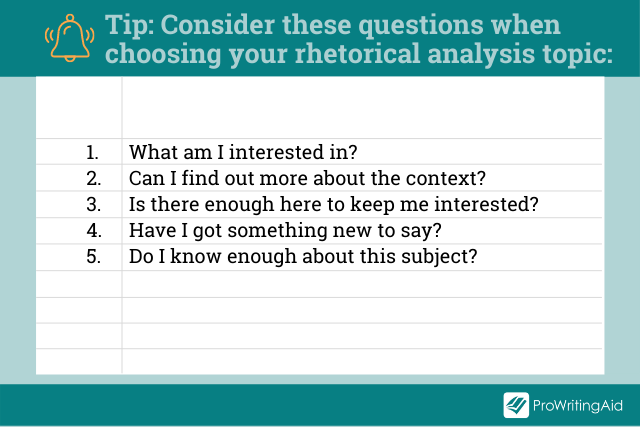

A great essay starts with an interesting topic. Choose carefully so you’re personally invested in the subject and familiar with it rather than just following trending topics. There are lots of great ideas on this blog post by My Perfect Words if you need some inspiration. Take some time to do background research to ensure your topic offers good analysis opportunities.

Remember to check the information given to you by your professor so you follow their preferred style guidelines. This outline example gives you a general idea of a format to follow, but there will likely be specific requests about layout and content in your course handbook. It’s always worth asking your institution if you’re unsure.

Make notes for each section of your essay before you write. This makes it easy for you to write a well-structured text that flows naturally to a conclusion. You will develop each note into a paragraph. Look at this example by College Essay for useful ideas about the structure.

1: Introduction

This is a short, informative section that shows you understand the purpose of the text. It tempts the reader to find out more by mentioning what will come in the main body of your essay.

- Name the author of the text and the title of their work followed by the date in parentheses

- Use a verb to describe what the author does, e.g. “implies,” “asserts,” or “claims”

- Briefly summarize the text in your own words

- Mention the persuasive techniques used by the rhetor and its effect

Create a thesis statement to come at the end of your introduction.

After your introduction, move on to your critical analysis. This is the principal part of your essay.

- Explain the methods used by the author to inform, entertain, and/or persuade the audience using Aristotle's rhetorical triangle

- Use quotations to prove the statements you make

- Explain why the writer used this approach and how successful it is

- Consider how it makes the audience feel and react

Make each strategy a new paragraph rather than cramming them together, and always use proper citations. Check back to your course handbook if you’re unsure which citation style is preferred.

3: Conclusion

Your conclusion should summarize the points you’ve made in the main body of your essay. While you will draw the points together, this is not the place to introduce new information you’ve not previously mentioned.

Use your last sentence to share a powerful concluding statement that talks about the impact the text has on the audience(s) and wider society. How have its strategies helped to shape history?

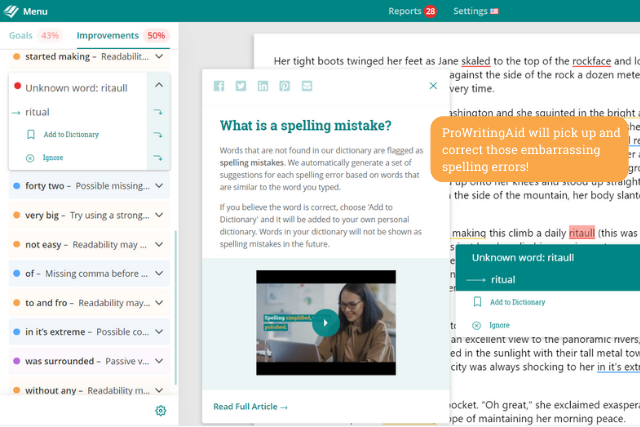

Before You Submit

Poor spelling and grammatical errors ruin a great essay. Use ProWritingAid to check through your finished essay before you submit. It will pick up all the minor errors you’ve missed and help you give your essay a final polish. Look at this useful ProWritingAid webinar for further ideas to help you significantly improve your essays. Sign up for a free trial today and start editing your essays!

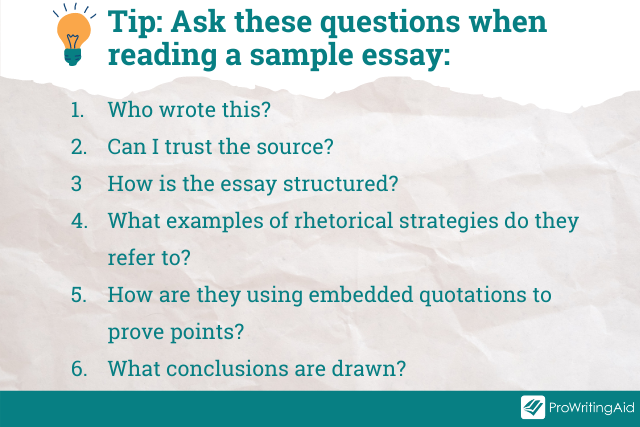

You’ll find countless examples of rhetorical analysis online, but they range widely in quality. Your institution may have example essays they can share with you to show you exactly what they’re looking for.

The following links should give you a good starting point if you’re looking for ideas:

Pearson Canada has a range of good examples. Look at how embedded quotations are used to prove the points being made. The end questions help you unpick how successful each essay is.

Excelsior College has an excellent sample essay complete with useful comments highlighting the techniques used.

Brighton Online has a selection of interesting essays to look at. In this specific example, consider how wider reading has deepened the exploration of the text.

Writing a rhetorical analysis essay can seem daunting, but spending significant time deeply analyzing the text before you write will make it far more achievable and result in a better-quality essay overall.

It can take some time to write a good essay. Aim to complete it well before the deadline so you don’t feel rushed. Use ProWritingAid’s comprehensive checks to find any errors and make changes to improve readability. Then you’ll be ready to submit your finished essay, knowing it’s as good as you can possibly make it.

Try ProWritingAid's Editor for Yourself

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Helly Douglas is a UK writer and teacher, specialising in education, children, and parenting. She loves making the complex seem simple through blogs, articles, and curriculum content. You can check out her work at hellydouglas.com or connect on Twitter @hellydouglas. When she’s not writing, you will find her in a classroom, being a mum or battling against the wilderness of her garden—the garden is winning!

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Visual and Spatial Rhetoric: Analyzing Images

Most texts are more than words on a page. Photographs, works of art, graphic novels, political cartoons, computer or video game screens, television or magazine advertisements, webpages, billboards, and more are all texts composed and designed to communicate ideas.

The texts you encounter in college also have visual or spatial components—an author’s profile picture on a publisher’s website, a reporter’s blog with hyperlinks to recommended websites, embedded videos and podcasts, a scientist’s precise figures and tables within a cutting-edge scientific journal, a business person’s PowerPoint presentation to prospective investors, or the photographic forensic evidence a police detective collects during a routine crime scene investigation.

A viewer or reader will come to many substantial conclusions analyzing a visual or spatial text. There often is not a “right” answer as much as a well-supported approach to a possible idea. Each viewer interprets the image separately (Alfano & O’Brien, 2017).

Whatever discipline you study, chances are you’ll come into contact with images, illustrations, and designs that require a sophisticated and close reading, so you may draw conclusions about the text’s rhetorical significance—its argument—that which the text makes the reader understand or believe.

Audience, Context, Subject, and Purpose

Analyzing a text’s rhetorical significance begins with determining the rhetorical situation—how the communication format, be it visual, written, aural, or any other multimodal form, situates itself on four main concepts: the audience, context, subject, and purpose.

Audience : Who is the intended audience for the text, and how do you know?

Context : What historical, sociological, cultural, political, ideological, or genre situations influence the text? What was happening during the time this text was being created?

Subject and Purpose : What is the author expressing? Why do you think her or she is communicating about this particular idea, issue, or concept?

Visual and spatial rhetoric uses images to communicate ideas. What is Figure 1 communicating?

Visual Rhetoric Sample Analysis: “Cake Batter With Eggs”

Note . From Mixing Bowl With Flour and Eggs and Spatula , by Clipart.com, 2015 ( https://www.clipart.com/download.php?iid=1792295&tl=photos ). Copyright 2015 by Clipart.com. Reprinted with permission.

Subject : What the author wants the audience to explore. Example : Homemade cake batter with fresh eggs.

Purpose : Why is the author creating this text? Example : Perhaps the creator of this photograph wanted to document kitchen adventures or she or he may love to bake.

Audience : Who is the author trying to reach? Example : Possibly food lovers who like to see how ingredients morph into baked goods.

Context : What historical or value-based situation surrounds this text? Example : A personal food blog? Perhaps a cooking website? Something fairly contemporary and American given the style of cooking instruments being used (plastic bowl, spatula, and measuring cups (in cups rather than pints or liters used outside the US).

What to Look for in a Visual Text

Next, you’ll want to look at the grounding, color scheme, medium, and typography of the text:

Grounding or the placement of images within a text : What is the most and least prominent element? The first place the eye focuses may seem the most important, but the background may be influencing your understanding of the text as well.

Color scheme, the colors the artist chooses : Blues and greys are associated with water and stone, so they suggest a cooling and calming mood; greens remind people of living plants as well as money, so they can suggest both health and wealth; yellows are commonly used on hospital walls to evoke a softness (in an otherwise noisy environment); and reds express passion as well as anger, creating feelings of energy and excitement.

Medium, the materials the artist chooses : A painter may use watercolor or oil; a sculptor may choose clay, copper, bronze, or iron; a cartoonist may use pencils on paper; and a writer may use a digital medium. The medium can suggest the intended audience as well as the purpose of the communication.

Typography, the appearance of printed characters : What moods do the fonts create?

Typography on a Bakery and Catering Storefront Window

Heading fonts may be different than body text fonts for the purpose of readability. Depending on the intended reader and purpose, fonts may be chosen to express formality or playfulness or to express a particular cultural or historical context.

Visual Rhetoric and Color Theory

Color theory looks at how colors work together to create effective and appealing designs. Certain colors also act symbolically to affect us emotionally.

The color wheel, first developed by Sir Issac Newton, provides a framework for understanding color harmony. The color wheel depicts the primary colors (red, blue, and yellow) and the secondary colors (green, orange, and purple), which are formed from mixing the primary colors. The tertiary colors (red-orange, yellow-orange, red-violet, blue-violet, blue-green, and yellow-green) are formed when primary and secondary colors are mixed.

The Color Wheel

Color harmony suggests that certain colors together create palates that are pleasing to the eye. These color combinations include analogous colors, or any set of three colors that appear next to each other on the color wheel such as blue, blue-green, and green.

Another formula for pleasing color arrangements is to choose complementary colors, or two colors which appear directly opposite each other on the color wheel such as purple and yellow. Finally, a designer may choose to mimic a combination found in nature such as the yellow, red, orange, and brown colors found in autumn foliage.

Image of Markers, Drafting Tools, and Pantone Color Swatches

Color theory also includes the emotional effect of certain colors through natural association and symbolism.

Visual Rhetoric: Analyzing Pictures

When analyzing the rhetorical significance of a photograph, the goal is to uncover its argument. Does the photograph say something about love? Family? Patriotism? Wellness? Success? What happiness is?

In determining the argument, the first elements to analyze are the audience, context, subject, and purpose . Additionally, you’ll want to consider the following:

- Material context : Where was the picture published? Where is it displayed? Is it the original version or a reproduction (as might be the case for artwork and paintings)?

- Rhetorical Stance : What is the point-of-view of the photographer? Is the photographer a participant in the activity or scene being depicted, or is the photographer an observer? Are the subjects in the picture aware that their photo is being taken? Where is the focus of the image?

- Reality or Abstraction : Is the photograph of a realistic scene, or has it been edited into an abstract piece of art? How do the modifications (if any) affect the meaning of the image? Does the editing serve the purpose of making the people in the picture look younger or more attractive than they might be otherwise?

- Caption and Accompanying Text : Does the photo have a title and/or a caption? Does it accompany written text such as on a website, in a newspaper, or in a magazine? How does the photograph support or illustrate the text? How does the text affect the meaning of the picture? The next section of this resource covers images with text in more detail.

Analyzing Pictures

Photographic elements work together to communicate ideas.

Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima, February 23, 1945

Note. From Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima , by Joe Rosenthal, 1945, Archives.gov ( https://unwritten-record.blogs.archives.gov/2015/02/23/raising-the-flag-over-iwo-jima/ ). In the public domain.

Subject or content : The scene or people the photo is depicting. Example : Five marines and a Navy hospital corpsman raising an American flag on top of Mt. Surabachi, Iwo Jima during World War II.

Purpose : Why is the author creating this text? Example : The photographer was from the Associated Press. He was documenting the battle of Iwo Jima during WWII.

Audience : Who is the author trying to reach? Example : The photographer likely intended to reach the American public who revere the American Flag as a symbol of pride and patriotism and who were awaiting news about the progress of the war.

Cultural Context : What is the cultural or historical context of the photograph, and how does that context affect the photograph’s meaning and importance? Example : This photo was taken during the bloodiest battle of WWII when the American public needed reassurance that they were doing the right thing. The photograph was immediately popular and widely reproduced as a message to support the war.

Visual Rhetoric: Images and Text

Authors and designers carefully consider the inclusion and interplay of visual images with text. For example, consider this picture quote from the Purdue Global Facebook page:

Image of Children in the Rain

Note. From A Loving Heart , by Purdue University Global, 2020 ( https://www.facebook.com/PurdueGlobal ). Copyright 2020 by Purdue University Global.

In this example, the image of the children holding hands sharing an umbrella interacts with the quote from Tomas Carlyle (1795-1891): “A loving heart is the beginning of all knowledge.” The text expresses a possible idea behind the image of the children who appear loving. And as this was a Facebook post by a university, the connection to knowledge fits with the context of the webpage.

Consider how your reaction to this picture would be different if the text were removed? What about if the image were removed? Or if the image were changed? These questions are valuable when analyzing and discussing the visual rhetoric of print advertisements, television commercials, websites, and cartoons too.

Visual and spatial texts make arguments, and readers will have different understandings and beliefs about them. Analyzing a text’s subject, purpose, audience, and context, taking into consideration the colors, design, perspective, and the interplay of visuals and language is critical when it comes to developing your own understandings and beliefs and then communicating your own arguments about them.

Alfano, C. & O’Brien, A. (2017). Envision: Writing and researching arguments (5th ed.). Pierson Education. https://bit.ly/32RxV4x

Share this:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Follow Blog via Email

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive email notifications of new posts.

Email Address

- RSS - Posts

- RSS - Comments

- COLLEGE WRITING

- USING SOURCES & APA STYLE

- EFFECTIVE WRITING PODCASTS

- LEARNING FOR SUCCESS

- PLAGIARISM INFORMATION

- FACULTY RESOURCES

- Student Webinar Calendar

- Academic Success Center

- Writing Center

- About the ASC Tutors

- DIVERSITY TRAINING

- PG Peer Tutors

- PG Student Access

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

- College Writing

- Using Sources & APA Style

- Learning for Success

- Effective Writing Podcasts

- Plagiarism Information

- Faculty Resources

- Tutor Training

Twitter feed

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

So far you have examined how primarily written arguments work rhetorically. But visuals (symbols, paintings, photographs, advertisements, cartoons, etc.) also work rhetorically, and their meaning changes from context to context.

Imagine two straight lines intersecting each other at right angles. One line runs from north to south. The other from east to west. Now think about the meanings that this sign evokes.

What came to mind as you pondered this sign? Crossroads? A first aid sign? The Swiss flag? Your little brother making a cross sign with his forefingers that signals “step away from the hallowed ground that is my bedroom”?

Now think of a circle around those lines so that the ends of the lines hit, or cross over, the circumference of the circle. What is the image’s purpose now?

What did you come up with? The Celtic cross? A surveyor’s target? A pizza cut into really generous sizes?

Did you know that this symbol is also the symbol for our planet Earth? And it’s the symbol for the Norse god, Odin. Furthermore, a quick web search will also tell you that John Dalton, a British chemist who led the way in atomic theory and died in 1844, used this exact same symbol to indicate the element sulfur.

Recently, however, the symbol became the subject of a fiery political controversy. The marketing team of former Alaska governor (and former vice-presidential candidate), Sarah Palin, placed several of these symbols—the lines crossed over the circumference of the circle in this case—on a map of the United States. The symbols indicated where the Republican Party had to concentrate their campaign because these two seemingly innocuous lines encompassed by a circle evoked, in this context, the symbol for crosshairs—which itself invokes a myriad of meanings that range from “focus” to “target.”

However, after the shooting of Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords in Arizona in January 2011, the symbol, and the image it was mapped onto, sparked a vehement nationwide debate about its connotative meaning. Clearly, the image’s rhetorical effectiveness had transformed into something that some considered offensive. Palin’s team withdrew the image from her website.

How we understand symbols rhetorically, and indeed all images, depends on how the symbols work with the words they accompany, and on how we understand and read the image’s context, or the social “landscape” within which the image is situated. As you have learned from earlier chapters, much of this contextual knowledge in persuasive situations is tacit, or unspoken.

Like writing, how we use images has real implications in the world. So when we examine visuals in rhetorical circumstances, we need to uncover this tacit knowledge. Even a seemingly innocuous symbol, like the one above, can denote a huge variety of meanings, and these meanings can become culturally loaded. The same is true for more complex images—something we will examine at length below.

In this chapter, we will explore how context—as well as purpose, audience, and design—render symbols and images rhetorically effective. The political anecdote above may seem shocking, but, nevertheless, it indicates how persuasively potent visuals are, especially when they enhance the meaning of a text’s words or vice versa. Our goal for this chapter, then, is to come to terms with the basics of visual analysis, which can encompass the analysis of words working with images or the analysis of images alone. When you compose your own arguments, you can put to use what you discover in this chapter when you select or consider creating visuals to accompany your own work.

Here is an overview of Visual Rhetoric from the OWL at Purdue:

Rhetorical Analysis of Visual Texts

Let’s start with by reviewing what we mean by analysis. Imagine that your old car has broken down and your Uncle Bob has announced that he will fix it for you. The next day, you go to Uncle Bob’s garage and find the engine of your car in pieces all over the driveway; you are further greeted with a vision of your hapless uncle greasily jabbing at the radiator with a screwdriver. Uncle Bob (whom you may never speak to again) has broken the car engine down into its component parts to try and figure out how your poor old car works and what is wrong with it.

Happy days are ahead, however. Despite the shock and horror that the scene above inspires, there is a method to Uncle Bob’s madness. Amid the wreckage, he finds out how your car works and what is wrong with it, so he can fix it and put it back together.

Likewise, analyzing entails breaking down a text or an image into component parts (like your engine). And while analyzing doesn’t entail fixing per se, it does allow you to figure out how a text or image works to convey the message it is trying to communicate. What constitutes the component parts of an image? How might we analyze a visual? What should we be looking for? To a certain extent we can analyze visuals in the same way we analyze written language; we break down a written text into component parts to figure out just what the creator’s agenda might be and what effect the text might have on its readers.

When we analyze visuals we do take into account the same sorts of things we do when we analyze written texts, with some added features.

Please watch “Visual Rhetoric: How to Analyze Images”:

Genres that use visuals tell us a lot about what we can and can’t do with them. Coming to terms with genre is rather like learning a new dance—certain moves, or conventions, are expected that dictate what kind of dance you have to learn. If you’re asked to moonwalk, for instance, you know you have to glide backwards across the floor like Michael Jackson. It’s sort of the same with visuals and texts; certain moves, or conventions, are expected that dictate what the genre allows and doesn’t allow.

Below is a wonderful old bumper sticker from the 1960s 19. A bumper sticker, as we will discover, is a genre that involves specific conventions.

Bumper stickers today look quite a bit different, but the amount of space that a sticker’s creator has to work with hasn’t really changed. Bumper stickers demand that their creators come up with short phrases that are contextually understandable and accompanied by images that are easily readable—a photograph of an oil painting trying to squeeze itself on a bumper sticker would just be incomprehensible. In short, bumper stickers are an argument in a rush!

A bumper sticker calls for an analysis of images and words working together to create an argument. As for their rhetorical content, bumper stickers can demand that we vote a certain way, pay attention to a problem, act as part of a solution, or even recognize the affiliations of the driver of the car the sticker is stuck to. But their very success, given that their content is minimal, depends wholly on our understanding of the words and the symbols that accompany them in context.

The procedure for doing a rhetorical analysis of a visual text is essentially the same as for a spoken/written text.

Step 1: Read the Text

In the case of a visual text, there might be words or there might not. If there are no words, “read” the image and think about what the creator of the image is trying to portray. Rather than a summary of the text, you might write a description of the image, including what you believe the author’s main intent is. In this case, your description might be fairly short:

Step 2: Define the Rhetorical Situation

Again, this step is very similar to what you would do for a written/spoken text. Simply answer the same questions about the visual text. Remember the acronym SOAP:

In this case, the speaker isn’t as clear as it might be in a spoken or written text. In general, a speech is made by a specific person, and a written text has an author. In some cases, determining the origin of a visual text could be difficult. In this case, we can presume that the bumper sticker was made by the Democratic Party as a campaign effort.

Audience and Medium

In their book Picturing Texts , Lester Faigley et al claim that, when determining the audience for a visual, we must “think about how an author might expect the audience to receive the work” (104). Medium, then, dominates an audience’s reception of an image. For instance, Faigley states that readers will most likely accept a photograph in a newspaper as news—unless of course one thinks that pictures in the tabloids of alien babies impersonating Elvis constitute news. Alien babies aside, readers of the news would expect that the picture on the front page of the New York Times , for instance, is a “faithful representation of something that actually happened” (105). An audience for a political cartoon in the newspaper, on the other hand, would know that the pictures they see in cartoons are not faithful representations of the news but opinions about current events and their participants, caricatured by a cartoonist. The expectations of the audience in terms of medium, then, determine much about how the visual is received.

As for our bumper sticker then, we might argue that the image of JFK speeding down the highway on the bumper of a spiffy new Ford Falcon would be persuasive to those who put their faith in the efficacy of bumper stickers, as well as the image of the man on the bumper sticker. Moreover, given that the Falcon is speeding by, we might assume that the bumper sticker would mostly appeal to those folks who are already thinking of voting for JFK—otherwise there’s a chance that the Falcon’s driver would be the recipient of some 1960s-style road rage.

Today, the audience for our bumper sticker has changed considerably. We might find it in a library collection. Or we might find it collecting bids on eBay. Once again, the audience for this example of images and words working together rhetorically depends largely on its contextual landscape.

Occasion/Context

Thinking about context is crucial when we are analyzing visuals, as it is with analyzing writing. We need to understand the political, social, economic, or historical situations from which the visual emerges. Moreover, we have to remember that the meaning of images change as time passes. For instance, what do we have to understand about the context from which the Kennedy sticker emerged in order to grasp its meaning? Furthermore, how has its meaning changed in the past 50 years?

First, to read the bumper sticker at face value, we have to know that a man named Kennedy is running for president. But president of what? Maybe that’s obvious, but then again, how many know who the Australian prime minister was 50 years ago, or, for that matter, the leading official in China? Of course, we should know that the face on the bumper sticker belongs to John F. Kennedy, a US Democrat, who ran against the Republican nominee Richard Nixon, and who won the US presidential election in 1960. (We hope you know that anyway.)

Now think how someone seeing this bumper sticker, and the image of Kennedy on it, today would react differently than someone in 1960 would have. Since his election, JFK’s status has transformed from American president into an icon of American history. We remember his historic debate with Nixon, the first televised presidential debate.

One wonders how much of a role this event played in his election given that the TV, a visual medium, turned a political underdog into a celebrity. We also remember Kennedy for his part in the Cuban missile crisis, his integral role in the Civil Rights Movement and, tragically, we remember his assassination in 1963. In other words, after the passage of 50 years, we might read the face on the bumper sticker quite differently than we might have in 1960.

While we examine this “text” from 50 years ago, it reminds us that the images we are surrounded by now change in meaning all the time. For instance, we are all familiar with the Apple logo. The image itself, on its own terms, is simply a silhouette of an apple with a bite taken out of it. But, the visual does not now evoke the nourishment of a Granny Smith or a Golden Delicious. Instead, the logo is globally recognized as an icon of computer technology.

Words and images can work together to present a point of view. But, in terms of visuals, that point of view often relies on what isn’t explicit—what, as we noted above, is tacit.

The words on the sticker say quite simply “Kennedy For President.” We know now that this simple statement reveals that John F. Kennedy ran for president in 1960. But what was its rhetorical value back then? What did the bumper sticker want us to do with its message? After all, taken literally, it doesn’t really tell us to do anything.

For now, let’s cheat and jump the gun and guess that the bumper sticker’s argument in 1960 was “Vote to Elect John F Kennedy for United States President.”

Okay. So knowing what we know from history, we can accept that the sticker is urging us to vote for Kennedy. It’s trying to persuade us to do something. And the reason we know what we know about it is because we know how to read its genre and we comprehend its social, political, and historical context. But in order to be persuaded by its purpose, we need to know why voting for JFK is a good thing. We need to understand that its underlying message, “Vote for JFK,” is that to vote for JFK is a good thing for the future of the United States.

So, to be persuaded by the bumper sticker, we must agree with the reasons why voting for JFK is a good thing. But the bumper sticker doesn’t give us any. Instead, it relies on what we are supposed to know about why we should vote for Kennedy. For instance, if we were present for the campaign, we would know that JFK campaigned on a platform of liberal reform as well as increased spending for the military and space travel technology. Moreover, we would be aware of the evidence for why we should vote that way. Consequently, if we voted for JFK, we accepted the above claim, reasons, and evidence driving the bumper sticker’s purpose without being told any of it by the bumper sticker. The claim, reasons and evidence are all tacit.

What about the image itself? How does that further the bumper sticker’s purpose? We see that the image of JFK’s smiling face is projected on top of the words “Kennedy for President.” The image is not placed off to the side; it is right in the middle of the bumper sticker. So for this bumper sticker to be visually persuasive, we need to agree that JFK, here represented by his smiling face, located right in the middle of the bumper sticker, on a backdrop of red, white, and blue, signifies a person we can trust to run the country.

Nowadays, JFK’s face on the bumper sticker—or in any other genre for that matter —might underscore a different purpose. It might encompass nostalgia for an era gone by or it might be used as a resemblance argument, in order to compare President Kennedy with President Obama for example.

Overall then, when we see a visual used for rhetorical purposes, we must first determine the argument (claim, reasons, evidence) from which the visual is situated and then try to grasp why the visual is being used to further its purpose.

To these, we will add one more element–Setting–making our acronym SOAPS.

When analyzing visual texts, the style in which the text is created is important. In rhetorical analysis, you should consider why this particular style was chosen–why use a bumper sticker or a billboard instead of writing an article in the newspaper?

Consider what format or medium the text being made: image? written essay? speech? song? protest sign? meme? sculpture?

- What is gained by having a text composed in a particular format/medium?

- What limitations does that format/medium have?

- What opportunities for expression does that format/medium have (that perhaps other formats do not have?)

3. Identify Rhetorical Strategies

Think through how the creator of the text uses ethos, pathos, logos, and kairos to portray the message. While you might see some rhetorical devices being employed, they might not play as large a role in visual texts. The elements of Design will play a much larger role in a visual analysis.

Design actually involves several factors.

Arrangement

Designers are trained to emphasize certain features of a visual text. And they are also trained to compose images that are balanced and harmonized. Faigley et al suggest that we look at a text that uses images (with or without words) and think about where our eyes are drawn first (34). Moreover, in Western cultures, we are trained to read from left to right and top to bottom—a pattern that often has an impact on what text or image is accentuated in a visual arrangement.

Other arrangements that Faigley et al discuss are closed and open forms (105). A closed-form image means that, like our bumper sticker, everything we need to know about the image is enclosed within its frame. An open form, on the other hand, suggests that the visual’s narrative continues outside the frame of the visual. Many sports ads employ open-frame visuals that suggest the dynamic of physical movement.

Another method of arrangement that is well known to designers is the rule of thirds . Here’s an example of that rule in action:

Note how the illustration above has been cordoned off into 9 sections. The drawings of the sun and the person, as well as the horizon, coincide with those lines. The rule of thirds dictates that this compositional method allows for an interesting and dynamic arrangement as opposed to one that is static. Now, unfortunately, our bumper sticker above doesn’t really obey that rule. Nevertheless, our eye is still drawn to the image of JFK’s head. Many modern bumper stickers do, however, obey the rule of thirds. Next time you see a bumper sticker on a parked car, check if the artist has paid attention to this rule. Or, seek out some landscape photography. The rule of thirds is the golden rule in landscape art and photography and is more or less a comprehensive way to analyze arrangement in design circles because of its focus on where one’s eye is drawn.

Rhetorically speaking, what is accentuated in a visual is the most important thing to remember about arrangement. As far as professional design is concerned, it is never haphazard. Even a great photo, which might be seem to be the result of serendipity, can be cropped to highlight what a newspaper editor, for instance, wants highlighted.

Texts and Image in Play

Is the visual supported by words? How do the words support the visual? What is gained by the words and what would be lost if they weren’t in accompaniment? What if we were to remove the words “Kennedy for President” from our bumper sticker? Would the sticker have the same rhetorical effect?

Moreover, when examining visual rhetoric, we should pinpoint how font emphasizes language. How does font render things more or less important, for instance? Is the font playful, like Comic Sans MS, or formal, like Arial? Is the font blocked, large, or small? What difference does the font make to the overall meaning of the visual? Imagine that our JFK bumper sticker was composed with a swirly- curly font. It probably wouldn’t send the desired message. Why not, do you think?

Alternately, think about the default font in Microsoft Word. What does it look like and why? What happens to the font if it is bolded or enlarged? Does it maintain a sense of continuity with the rest of the text? If you scroll through the different fonts available to you on your computer, which do you think are most appropriate for essay writing, website design, or the poster you may have to compose?

Lastly, even the use of white (or negative) space in relation to text deserves attention in terms of arrangement. The mismanagement of the relation of space to text and/or visual can result in visual overload! For instance, in an essay, double spacing is often advised because it is easier on the reader’s eye. In other words, the blank spaces between the lines of text render reading more manageable than would dense bricks of text. Similarly, one might arrange text and image against the blank space to create a balanced arrangement of both.

While in some situations the arrangement of text and visual (or white space) might not seem rhetorical (in an essay, for example), one could make the argument that cluttering one’s work is not especially rhetorically effective. After all, if you are trying to persuade your instructor to give you an ‘A’, making your essay effortlessly readable seems like a good place to start.

Visual Figures

Faigley et al also ask us to consider the use of figures in a visual argument (32). Figurative language is highly rhetorical, as are figurative images. For instance, visual metaphors abound in visual rhetoric, especially advertising (32). A visual metaphor is at play when you encounter an image that signifies something other than its literal meaning. For instance, think of your favorite cereal: which cartoon character on the cereal box makes you salivate in anticipation of breakfast time? Next time, when you see a cartoon gnome and your tummy start to rumble in anticipation of chocolate-covered rice puffs, you’ll know that the design folks down at ACME cereals have done their job. Let’s hope, however, that you don’t want to chow down on the nearest short fat fellow in a red cap that comes your way.

Visual rhetoric also relies on synecdoche, a trope in which a part of something represents the whole . In England, for instance, a crown is used to represent the British monarchy. The image of JFK’s face on the bumper sticker, then, might suggest his competency to head up the country.

Colors are loaded with rhetorical meaning, both in terms of the values and emotions associated with them and their contextual background. Gunther Kress and Theo Van Leeuwen show how the use of color is as contextually bound as writing and images themselves. For instance, they write, “red is for danger, green for hope. In most parts of Europe, black is for mourning, though in northern parts of Portugal, and perhaps elsewhere in Europe as well, brides wear black gowns for their wedding day. In China, and other parts of East Asia, white is the color of mourning; in most of Europe it is the color of purity, worn by the bride at her wedding. Contrasts like these shake our confidence in the security of meaning of colour and colour terms” (343).

So what colors have seemingly unshakeable meaning in the US? How about red, white, and blue? Red and blue are two out of the three primary colors. They evoke a sense of sturdiness. After all, they are the base colors from which others are formed.

The combined colors of the American flag have come to signal patriotism and American values. But even American values, reflected in the appearance of the red, white, and blue, change in different contexts. To prompt further thought, Faigley shows us that the flag has been used to lend different meaning to a variety of magazine covers—from American Vogue (fashion) to Fortune magazine (money) (91). An image of the red, white and blue on the cover lends a particularly American flavor to each magazine. And this can change the theme of each magazine? For instance, with what would you acquaint a picture of the American flag on the cover of Bon Appétit or Rolling Stone ? Hot dogs and Bruce Springsteen perhaps?

What then does the red, white, and blue lend our bumper sticker? A distinctly patriotic flavor, for sure. Politically patriotic. And that can mean different things for different people. Thus, given that meanings change in a variety of contexts, we can see that the meaning of color can actually be more fluid than we might have originally thought.

Alternately, if our JFK sticker colors were anything other than red, white, and blue, we might read it very differently; indeed, it might seem extremely odd to us.

Kress and Van Leeuwen ask us to consider the modality in which an image is composed. Very simply, this means, how “real” does the image look? And what does this “realness” contribute to its persuasiveness? They write, “visuals can represent people, places, and things as though they are real, as though they actually exist in this way . . . or as though they do not” (161). Photographs are thus considered a more naturalistic representation of the world than clip art, for instance.

We expect photographs to give us a representation of reality. Thus, when a photograph is manipulated to signify something fantastic, like a unicorn or a dinosaur, we marvel at its ability to construct something that looks “real.” And when a visual shifts from one modality to another, it takes on additional meaning.