Eyewitness Testimony in Psychology

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Eyewitness testimony is a legal term that refers to an account given by people of an event they have witnessed.

For example, they may be required to describe a trial of a robbery or a road accident someone has seen. This includes the identification of perpetrators, details of the crime scene, etc.

Eyewitness testimony is an important area of research in cognitive psychology and human memory.

Juries tend to pay close attention to eyewitness testimony and generally find it a reliable source of information. However, research into this area has found that eyewitness testimony can be affected by many psychological factors:

Anxiety / Stress Reconstructive Memory Weapon Focus Leading Questions ( Loftus and Palmer, 1974 )

Anxiety / Stress

Anxiety or stress is almost always associated with real-life crimes of violence. Deffenbacher (1983) reviewed 21 studies and found that the stress-performance relationship followed an inverted-U function proposed by the Yerkes-Dodson Curve (1908).

This means that for tasks of moderate complexity (such as EWT), performance increases with stress up to an optimal point where it starts to decline.

Clifford and Scott (1978) found that people who saw a film of a violent attack remembered fewer of the 40 items of information about the event than a control group who saw a less stressful version. As witnessing a real crime is probably more stressful than taking part in an experiment, memory accuracy may well be even more affected in real life.

However, a study by Yuille and Cutshall (1986) contradicts the importance of stress in influencing eyewitness memory.

They showed that witnesses of a real-life incident (a gun shooting outside a gun shop in Canada) had remarkable accurate memories of a stressful event involving weapons. A thief stole guns and money, but was shot six times and died.

The police interviewed witnesses, and thirteen of them were re-interviewed five months later. Recall was found to be accurate, even after a long time, and two misleading questions inserted by the research team had no effect on recall accuracy. One weakness of this study was that the witnesses who experienced the highest levels of stress where actually closer to the event, and this may have helped with the accuracy of their memory recall.

The Yuille and Cutshall study illustrates two important points:

1. There are cases of real-life recall where memory for an anxious / stressful event is accurate, even some months later. 2. Misleading questions need not have the same effect as has been found in laboratory studies (e.g. Loftus & Palmer).

Reconstructive Memory

Bartlett’s theory of reconstructive memory is crucial to an understanding of the reliability of eyewitness testimony as he suggested that recall is subject to personal interpretation dependent on our learned or cultural norms and values, and the way we make sense of our world.

Many people believe that memory works something like a videotape. Storing information is like recording and remembering is like playing back what was recorded. With information being retrieved in much the same form as it was encoded.

However, memory does not work in this way. It is a feature of human memory that we do not store information exactly as it is presented to us. Rather, people extract from information the gist, or underlying meaning.

In other words, people store information in the way that makes the most sense to them. We make sense of information by trying to fit it into schemas, which are a way of organizing information.

Schemas are mental “units” of knowledge that correspond to frequently encountered people, objects or situations. They allow us to make sense of what we encounter in order that we can predict what is going to happen and what we should do in any given situation. These schemas may, in part, be determined by social values and therefore prejudice.

Schemas are, therefore capable of distorting unfamiliar or unconsciously ‘unacceptable’ information in order to ‘fit in’ with our existing knowledge or schemas. This can, therefore, result in unreliable eyewitness testimony.

Bartlett tested this theory using a variety of stories to illustrate that memory is an active process and subject to individual interpretation or construction.

In his famous study “War of the Ghosts”, Bartlett (1932) showed that memory is not just a factual recording of what has occurred, but that we make “effort after meaning”.

By this, Bartlett meant that we try to fit what we remember with what we really know and understand about the world. As a result, we quite often change our memories so they become more sensible to us.

His participants heard a story and had to tell the story to another person and so on, like a game of “Chinese Whispers”.

The story was a North American folk tale called “The War of the Ghosts”. When asked to recount the detail of the story, each person seemed to recall it in their own individual way.

With repeating telling, the passages became shorter, puzzling ideas were rationalized or omitted altogether and details changed to become more familiar or conventional.

For example, the information about the ghosts was omitted as it was difficult to explain, whilst participants frequently recalled the idea of “not going because he hadn’t told his parents where he was going” because that situation was more familiar to them.

For this research, Bartlett concluded that memory is not exact and is distorted by existing schema, or what we already know about the world.

It seems, therefore, that each of us ‘reconstructs’ our memories to conform to our personal beliefs about the world.

This clearly indicates that our memories are anything but reliable, ‘photographic’ records of events. They are individual recollections which have been shaped & constructed according to our stereotypes, beliefs, expectations etc.

The implications of this can be seen even more clearly in a study by Allport & Postman (1947).

When asked to recall details of the picture opposite, participants tended to report that it was the black man who was holding the razor.

Clearly this is not correct and shows that memory is an active process and can be changed to “fit in” with what we expect to happen based on your knowledge and understanding of society (e.g. our schemas).

Weapon Focus

This refers to an eyewitness’s concentration on a weapon to the exclusion of other details of a crime. In a crime where a weapon is involved, it is not unusual for a witness to be able to describe the weapon in much more detail than the person holding it.

Loftus et al. (1987) showed participants a series of slides of a customer in a restaurant. In one version, the customer was holding a gun, in the other the same customer held a checkbook.

Participants who saw the gun version tended to focus on the gun. As a result, they were less likely to identify the customer in an identity parade those who had seen the checkbook version

However, a study by Yuille and Cutshall (1986) contradicts the importance of weapon focus in influencing eyewitness memory.

Allport, G. W., & Postman, L. J. (1947). The psychology of rumor . NewYork: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Bartlett, F.C. (1932). Remembering: A Study in Experimental and Social Psychology . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clifford, B.R. and Scott, J. (1978). Individual and situational factors in eyewitness memory. Journal of Applied Psychology , 63, 352-359.

Deffenbacher, K. A. (1983). The influence of arousal on reliability of testimony. In S. M. A. Lloyd-Bostock & B. R. Clifford (Eds.). Evaluating witness evidence . Chichester: Wiley. (pp. 235-251).

Loftus, E.F., Loftus, G.R., & Messo, J. (1987). Some facts about weapon focus. Law and Human Behavior , 11, 55-62.

Yerkes R.M., Dodson JD (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology , 18: 459–482.

Yuille, J.C., & Cutshall, J.L. (1986). A case study of eyewitness memory of a crime. Journal of Applied Psychology , 71, 291-301.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

- Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Eyewitness memory.

- John T. Wixted John T. Wixted University of California San Diego

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.911

- Published online: 22 March 2023

Eyewitness testimony during a criminal trial, even when made in good faith, is widely considered to be unreliable because (a) basic-science research has shown how malleable eyewitness memory can be and (b) many real-world wrongful convictions involve eyewitness misidentifications of innocent defendants. However, like other forms of forensic evidence, there are conditions under which declarations based on eyewitness memory are reliable and conditions under which they are unreliable. Precisely because memory is so malleable, declarations based on eyewitness memory are the most reliable on the first test conducted early in a police investigation. Indeed, the very act of testing memory changes (i.e., contaminates) memory, and this is true whether memory is tested by a police interview (recall of details) or by a police photo lineup (face recognition). For example, because of the contaminating effect of the first test, a witness who initially recalls a detail with low confidence is at risk of later recalling that same detail with higher confidence. Similarly, a witness who initially identifies a suspect from a photo lineup with low confidence is at risk of later identifying that same suspect with higher confidence. In addition, memory can be contaminated by extraneous factors that occur after the first test (e.g., conversations with other people), leading to higher confidence or even to an altogether different memory decision (e.g., initially claiming that a person well known to the witness was not the perpetrator but later remembering that he was). Unbeknownst to police investigators, any change in a witness’s good-faith memory of events after the first test is far more likely to reflect memory contamination than it is to reflect a more successful search of memory. Moreover, and critically, this is true no matter how the witness rationalizes the inconsistency (e.g., “I was nervous on the first test but then I calmed down and searched my memory more carefully, and now I am positive he is the perpetrator”). A witness has no awareness of the insidious effects of memory contamination and certainly has no scientific expertise in the underlying memory mechanisms involved. Therefore, asking why a witness’s memory-based declaration changed from one test to the next is a question for a memory expert, not an eyewitness. A memory expert can explain that the main problem with relying on eyewitness memory is not that it is unreliable. Instead, the main problem is that the criminal justice system ignores the results of the reliable first test of uncontaminated memory and instead relies on the results of subsequent unreliable tests of contaminated memory to win a conviction. Assuming good faith on the part of the eyewitness, this practice should be reversed by relying on the results of the first test of uncontaminated memory and ignoring all later tests, especially the maximally contaminated test of memory that occurs under oath at trial.

- photo lineup

- police interview

- eyewitness memory reliability

- memory contamination

- confidence and accuracy

Is eyewitness memory reliable? In years gone by, the science-based answer to this question was an emphatic “no.” However, a large body of research has accumulated showing that eyewitness memory is a lot like other kinds of forensic evidence: There are conditions under which it is reliable and conditions under which it is unreliable. Therefore, instead of asking whether eyewitness memory is reliable, a better question to ask is the following: When is eyewitness memory reliable and when is it unreliable?

In the legal system, the answer to that question is ultimately a judgment call, one that scientists can inform but cannot make. Instead, for any given case, judges and juries ultimately make that call, ideally with guidance from science. The science-based story summarized here begins with a brief consideration of how memory works followed by a consideration of the two main ways that eyewitness memory can be tested, namely, by recall (a police interview) or by face recognition (an eyewitness identification procedure). Either way, it is important to distinguish between the conditions under which eyewitness memory provides useful information and the conditions under which it does not.

A Brief Tutorial on How Memory Works

At the time of the to-be-remembered experience, memories are formed when sensory information from different modalities (e.g., sights, sounds, smells) simultaneously activates distributed regions of the brain that are each specialized for processing modality-specific information. For example, visual aspects of the experience are initially processed by regions of the brain that are specialized for processing visual information, auditory aspects of the experience are initially processed by regions of the brain that are specialized for processing auditory information, and so on.

Aspects of the multisensory experience that command attention are encoded (i.e., a record is formed in the brain), whereas aspects of an experience that fall outside the focus of attention are not. Thus, encoded memories tend to be fragmentary, not complete representations of an experience. As an example, a witness might attend to the perpetrator’s face but not to what the perpetrator was wearing. In that case, a memory record of his face, but not his clothing, would be formed. Interestingly, according to standard principles of neuroscience, the memory record is formed in the same specialized region of the brain that processed the incoming sensory information ( Brodt & Gais, 2021 ). In this example, the face-processing neurons that are responsible for initially perceiving the face also create a memory record of that face.

Needless to say, after information is encoded, forgetting inevitably occurs. It might therefore seem obvious that the more time that goes by since the information was encoded (before memory is tested), the less reliable any remembered information will be. However, this, too, is a more nuanced story than intuition might suggest. As time goes by and forgetting occurs, less and less information about the crime will be remembered. In that sense, memory becomes less accurate over time. However, the main question of interest to triers of fact (judges and juries) concerns the reliability of any information that is still retained. Sometimes, that information remains reliable even after a long retention interval and sometimes it does not.

At the retrieval stage, memory is usually tested in one of two basic ways, namely, recall or recognition. In a recall test, the witness is asked to recollect details about the crime during a police interview. In a recognition test, the face of a suspect is presented to the witness as part of an eyewitness identification procedure, and the witness is asked whether or not this is the person who committed the crime. Although the principles of memory are similar in some respects for these two ways of testing memory, they also have some key differences, so they are best considered separately.

Testing Recall of Events Using an Interview

When asked to recall events (e.g., “tell me what happened, starting at the beginning”), a witness retrieves the fragmentary memory record while, at the same time, the brain unconsciously “fills in the blanks” with reasonable default assumptions about other details that were likely present at the time of encoding. Until the 1970s, it was generally assumed that such memories were reliable so long as they appeared to be honestly believed and had the qualities of true memories (e.g., they were detailed, confidently reported, and perhaps even accompanied by emotion). However, classic work by Elizabeth Loftus beginning in the 1970s began to change that perspective.

Memory Is Malleable

In early work, Loftus and Palmer (1974) found that altering a single suggestive word during the questioning of a witness can influence the witness’s memory for a video of a car crash. For example, asking “how fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?” resulted in witnesses later (falsely) recalling broken glass much more often than asking “how fast were the cars going when they contacted each other?” A few years later, Loftus et al. (1978) reported that memory for the details of a traffic accident could be distorted by false post-event suggestion (e.g., the misleading suggestion of a stop sign when the witness actually saw a yield sign). Still later, Loftus and her colleagues found that it was possible to implant more elaborate false memories. For example, by providing misleading information, false memories have been implanted of being lost in a shopping mall ( Loftus & Pickrell, 1995 ), of spilling punch on the parents of the bride at a wedding ( Hyman & Billings, 1998 ), and of committing a crime ( Shaw & Porter, 2015 ; see also Shaw, 2018 ; Wade et al., 2018 ). False memories have also been implanted for being hospitalized overnight for an ear infection, for getting one’s hand caught in a mousetrap ( Lindsay et al., 2004 ), and for having received a skin graft as part of a routine medical procedure as a child ( Mazzoni & Memon, 2003 ).

Moral Panics Involving Apparently False Memories

The idea that memory is malleable initially caught the field by surprise, but the fact that detailed false memories can be unintentionally formed is now widely accepted. However, what came as a further surprise to the field in the 1980s and 1990s is the fact that it is even possible for detailed and seemingly believable memories of childhood sexual abuse to be completely false. In addition to basic laboratory research suggesting that nonsexual false memories are easy to create, two separate overreactions by the criminal justice system led to the painful realization that the same is true for highly detailed memories of childhood sexual abuse.

The McMartin Preschool Trial

The first overreaction is known as the “McMartin Preschool trial,” where daycare operators were charged with sexually abusing children under their care. The daycare operators were ultimately acquitted years later after it became clear that the highly detailed memories of sexual abuse (sincerely believed by the children and still believed by some of them now that they are adults) were almost certainly false, having been unintentionally implanted by well-intentioned investigators who repeatedly interviewed them ( Garven et al., 1998 ).

Recovered Memories of Childhood Sexual Abuse

The hope that an unintentionally suggestive interview technique might be a problem only when children were interviewed was dashed shortly thereafter. The second overreaction played out mostly in the 1990s and is sometimes referred to as the “repressed memory epidemic” ( Pendergrast, 2017 ). It was during this time that adult women, often in therapy, would recover long-forgotten memories of childhood sexual abuse. Upon recovering these long-forgotten memories, charges would be filed against the remembered perpetrators, and some were sent to prison based on nothing more than the recovered memory (i.e., with no independent corroborating evidence). In retrospect, it is easy to understand why these memories were considered reliable enough to determine that the alleged perpetrators were guilty. After all, the recovered memories were highly detailed, they seemed to be (and undoubtedly were) emphatically believed by the alleged victim, they were plausible, and they were often accompanied by high levels of emotion. In short, the witnesses appeared to be highly credible. However, because memory is now understood to be malleable, when memories are announced for the first time years after the fact, they cannot be regarded as presumptively reliable. They might be true, but they might be false, and that is the problem.

Structured Interviews

The realization that interviewers and therapists can elicit false recollections that distort memory from that point forward prompted research into what kinds of interview questions have that effect and how to elicit accurate information using better questions. This research found that improper interview technique includes, for example, (a) asking suggestive questions or otherwise introducing postevent misinformation (e.g., Loftus et al., 1978 ), (b) asking an abundance of closed-ended questions (vs. more appropriate open-ended questions; Lamb et al., 2007 ), and (c) encouraging witnesses to guess as opposed to more appropriately providing an option not to respond ( Earhart et al., 2014 ). To avoid problematic questions like these while eliciting as much accurate information as possible, structured interviews have now been developed. For children, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development protocol ( Orbach et al., 2000 ) can be used to elicit accurate information without unintentionally contaminating memory in children. For adults, police departments can instead use the Cognitive Interview ( Fisher & Geiselman, 1992 ) or some variant of it. When such interview protocols are used early in a police investigation, what witnesses recall with high confidence tends to be quite accurate ( Wixted et al., 2018 ).

Whether or not a specific interview protocol is used, a report issued in 1999 by the Department of Justice provided general guidelines for how to interview a witness ( National Institute of Justice, 1999 ). In a section entitled “Section III: Procedures for Interviewing the Witness by the Follow-up Investigator,” the DOJ report recommended that during the interview, the investigator should do the following:

Encourage the witness to volunteer information without prompting.

Encourage the witness to report all details, even if they seem trivial.

Ask open-ended questions (e.g., “What can you tell me about the car?”); augment with closed-ended, specific questions (e.g., “What color was the car?”).

Avoid leading questions (e.g., “Was the car red?”).

Caution the witness not to guess.

Ask the witness to mentally recreate the circumstances of the event (e.g., “Think about your feelings at the time”).

Encourage nonverbal communication (e.g., drawings, gestures, objects).

Avoid interrupting the witness.

Encourage the witness to contact investigators when additional information is recalled.

Instruct the witness to avoid discussing details of the incident with other potential witnesses.

Encourage the witness to avoid contact with the media or exposure to media accounts concerning the incident.

Although a great deal of work has shed light on how to avoid the unintentional implantation of false memories when interviewing witnesses, it is not an easy skill to learn or maintain. The literature shows that someone who has been trained in the use of a structured interview and whose interviewing performance is monitored on a regular basis can obtain accurate information beyond what has been spontaneously reported by the witness. By contrast, interviewers who have not been trained and are not monitored on a regular basis are more likely to unintentionally elicit false information that risks contaminating memory. Price and Roberts (2011) summarized the problem as follows:

Warren et al. (1999) assessed the outcome of a 10-day training session in the U.S. that involved measuring both knowledge gain and interviewer behaviour change. Although interviewer knowledge about the content of the training was significantly increased following training, this newly acquired knowledge did not translate into a change in interviewer practices (see also Aldridge & Cameron, 1999 ; Freeman & Morris, 1999 ). The finding of increased knowledge, but a lack of behaviour change, is concerning and indicates that a simple knowledge assessment test following training is insufficient for determining training effectiveness.

Thus, mere knowledge of how to conduct an interview may not be enough. Proper interview technique appears to be a function of both training and then monitoring to ensure that a learned skill continues to be properly executed. In the absence of monitoring (with corrective feedback), interviewers tend to revert back to asking leading questions that can elicit false information.

Other Sources of Memory Contamination

It is important to also keep in mind that the memory test itself (involving improper interview technique) is not the only source of memory contamination. On the contrary, memory can be contaminated in a wide variety of ways. In this regard, consider some of the additional steps in the DOJ recommendations listed earlier (beyond interview technique) that are designed to avoid memory contamination, such as encouraging the witness to (a) avoid discussing details with other witnesses, (b) avoid contact with the media, and (c) avoid exposure to media accounts concerning the incident. These considerations underscore the importance of conducting a proper interview as soon as possible after the witnessed crime. Doing so minimizes the chances of memory contamination from independent sources (e.g., conversations with other witnesses, news reports, rumors).

Regardless of how memory is contaminated, once it happens, there is no way for the witness to know that it has happened and no way for anyone else to know it either. The reason is that false memories are subjectively experienced as true memories, and when they are described to others, they have all of the attributes of true memories. In a paper entitled “How to Tell If a Particular Memory Is True or False,” Bernstein and Loftus (2009) specifically addressed the striking similarities of true and false memories. They set up their analysis as follows:

Consider the following situation. Mary X sits on the witness stand in court, recounting an emotionally charged memory involving childhood sexual abuse. Her report is both detailed and emotional. She explains how her grandfather molested her and how she had repressed the event for many years before recovering the memory in therapy. Is Mary's report the result of a real memory or a product of suggestion or imagination or some other process? ( Bernstein & Loftus, 2009 , p. 370)

After reviewing the large body of scientific research that has addressed the question posed by the title of their paper, Bernstein and Loftus (2009) reached the following disconcerting conclusion: “If someone believes earnestly that he ate a large spider as a child, but in actuality he did not, how can we spot this falsehood? The simple, yet unsatisfying, answer is that we cannot determine this with certainty” (p. 370), and “the focus on single rich memories presently does not tell us whether a particular memory is true or false” (p. 373).

The qualities of the memories themselves cannot distinguish true from false memories; only independent corroborating evidence can verify if the memories are accurate. When tested by recall, memories of the distant past are not, in and of themselves, particularly diagnostic of the truth no matter how detailed they are, no matter how plausible they seem, no matter how sincerely believed they are, and no matter how much emotion they elicit. The reason is that there are many sources of contamination, and their effects simply cumulate over time. Therefore, the longer the retention interval (i.e., the more time has elapsed between encoding and retrieval), the more independent corroborating or disconfirming evidence is needed to determine whether the memories are true or false.

Even Recollections of Salient Events Become Less Reliable Over Time

The same basic principles emerged from a distinct line of memory research on the nature of forgetting. For example, in an influential study, Talarico and Rubin (2003) investigated memory for the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 . In their study, on September 12, 2001 , 54 participants were asked to record their memory of two events: (a) when they first heard about the terrorist attacks of September 11 and (b) a recent everyday event. They were tested again 1, 6, or 32 weeks later. Although “flashbulb memories” (i.e., memories of shocking events) are subjectively experienced as being forever etched in our brains, the accuracy of memories for the events of 9/11 declined over time in much the same way as the accuracy of memories for everyday events did. They differed only in that the decreasingly accurate memories of shocking events tended to be remembered with high confidence (despite the decline in accuracy), whereas the decreasingly accurate memories of everyday events were more appropriately remembered with decreasing confidence. The authors of this paper concluded that “Flashbulb memories are not special in their accuracy, as previously claimed, but only in their perceived accuracy.”

Precisely because confidently held memories evolve over time due to forgetting plus contamination, it is essential to test memory using a proper interview as soon as possible after the to-be-remembered event. Unfortunately, as time goes by, memories fade and can be contaminated in many ways, such as different witnesses talking to each other during everyday conversations, or seeing details about the event on the news or in the newspaper, or even just mentally rehearsing what might have happened. The latter phenomenon is known as “imagination inflation,” which refers to the fact that simply imagining an event increases the belief that it happened ( Garry & Polaschek, 2000 ; Mazzoni & Memon, 2003 ). For all of these reasons, the longer ago recalled events occurred, the less trustworthy those memories are, no matter how real they appear to be. Not only does the passage of time cause memories to weaken and provide more opportunity for contamination, but (as intuition suggests) the weaker memories become the more vulnerable they are to contamination (e.g., Baym & Gonsalves, 2010 ; Pezdek & Roe, 1995 ). This suggests that memories of very old events are especially susceptible to contamination.

Reminiscence

In another relevant line of research, studies have shown that under certain conditions, when someone is asked on more than one occasion to recall a prior event, information that they failed to recall on one test can be successfully recalled on a subsequent test. This phenomenon (i.e., recalling now what one failed to previously recall) can result in “hypermnesia,” which is an overall increase in the amount of accurately information recalled with successive testing (e.g., Scrivner & Safer, 1988 ). When that happens, it means that some information that was not recalled on the first test is recalled on a later test (a phenomenon known as “reminiscence”). However, and this is the key point, reminiscence has been observed when memory is tested soon after learning and when the interval of time between tests of memory is short. As reported by Wheeler and Roediger (1992) , “In general, when the intervals between successive tests are short, improvement occurs between tests. When these intervals are long, forgetting occurs” (p. 240). Indeed, as they further point out, when the intervals are long, “forgetting and distortion” due to the normal reconstructive processes of memory are to be expected. When sincerely recollected information emerges for the first time when memory is tested again long after the initial test, it raises concerns that the memory might be false. The most reliable information comes from tests conducted early in the police investigation, so the main focus should be placed on what is recollected at that time.

Testing Face Recognition Using a Photo Lineup

Eyewitness identification procedures are tests of face recognition memory. There are several different ways to conduct such tests, but the common denominator of all of them is that they involve a suspect, who is the person the police think may have committed the crime and who is either innocent or guilty. In an eyewitness identification procedure, the suspect’s face is shown to the eyewitness, who then decides whether or not this is the person who committed the crime. The suspect’s face can be tested either alone (a showup) or in a group (a lineup).

The simplest eyewitness identification procedure is known as a “showup,” where the police present a suspect to a witness for a yes/no decision about whether this is the person who committed the crime. A showup is often used soon after the police are called, while they are still actively processing a crime scene. For example, after canvassing the area, they might come across a suspect (e.g., someone who matches the description provided by the eyewitness) a few blocks away. The suspect is detained and brought to the witness, who is asked if this is the person who committed the crime. The key feature of this test is that it involves a single face. Although a showup usually involves an in-person test, memory is sometimes tested later in a police investigation using a single photo (“Is this the person who committed the crime?”). Such a single-photo test is also often referred to as a showup.

One long-standing concern about a showup is that it is inherently “suggestive” because the witness might reasonably conclude that the police have good reason to believe that this is the person who committed the crime. The witness might therefore identify the suspect on that basis alone, not because he matches the witness’s memory of the perpetrator. In technical terms, seeing a single face under suggestive conditions can induce a “response bias” (i.e., a tendency) to make an identification, whether the suspect strongly matches memory or not. For that reason, many believe that a less suggestive eyewitness identification procedure would be preferable.

An alternative eyewitness identification procedure is a lineup. A lineup consists of one suspect (who is either innocent or guilty) along with a number of physically similar “fillers” who are known to be innocent. When presented with a lineup, the witness can (a) identify the suspect, (b) identify a filler, or (c) reject the lineup. Live lineups were once the norm, but, according to a survey conducted in 2013 , photo lineups are used by the large majority of police departments ( Police Executive Research Forum, 2013 ). The photos can be presented all at once (a simultaneous lineup) or they can be presented one at a time for individual yes/no decisions (sequential lineup). One advantage of a well-constructed lineup is that it is much less suggestive than a showup because no single person stands out as the one who the police suspect as having committed the crime.

Conducting a Proper Lineup Procedure

Of course, a lineup is better than a showup only if it is properly constructed and properly administered. Recommendations on how to construct and administer a proper lineup have grown over the years and now include (a) selecting fillers who (at a minimum) match the witness’s description of the perpetrator, (b) including at least five fillers, (c) using a blind lineup administrator (i.e., an administrator who does not know the identity of the suspect), (d) instructing the witness that the perpetrator may or may not be present in the lineup, (e) recording an immediate confidence statement if the witness makes an identification (this applies to a showup as well), and (f) videotaping the entire procedure (see Wells et al., 2020 , for still more recommendations). Lineups are superior to showups not only because they are less suggestive but also because they enhance the ability of eyewitnesses to discriminate (i.e., tell the difference between) innocent and guilty suspects. What does that mean, exactly?

Lineups Increase Discriminability

Using a showup, imagine that out of every 100 innocent suspects, 20 are misidentified (false alarm rate = 20/100 = .20), and out of every 100 guilty suspects, 80 are correctly identified (hit rate = 80/100 = .80). However, using a lineup, imagine that only five out of every 100 innocent suspects are misidentified (false alarm rate = 5/100 = .05), and out of every 100 guilty suspects, 60 are correctly identified (hit rate = 60/100 = .60). This difference between the two procedures—that is, the lower hit and false alarm rates associated with a lineup compared to a showup—reflects a phenomenon known as “filler siphoning” ( Colloff et al., 2018 ; Smith et al., 2018 ); that is, identifications are made to fillers that might otherwise have been made to innocent or guilty suspects. The more fillers there are in a lineup, the lower both the hit rate and the false alarm rate to suspects will be due to filler siphoning.

Next imagine changing the showup procedure in such a way as to lower its false alarm rate to .05 as well (matching that of a lineup). This might be achieved, for example, by instructing witnesses tested using a showup not to make an identification unless they are 100% certain of being correct. Once the two procedures have been equated with respect to the false alarm rate, are they now diagnostically equivalent? That depends on their respective hit rates under the same conditions.

Using the showup procedure in conjunction with the new instruction not to make an identification in the absence of 100% certainty, the hit rate might now be reduced to .50 (from .80 without using that instruction). Thus, in this hypothetical example, although the false alarm rates for the two procedures would be equated at .05, the hit rate for the lineup (.60) would exceed that of the showup (.50). A pattern like that illustrates the general finding that lineups support higher discriminability than showups (e.g., Gronlund et al., 2012 ). The common finding that lineups achieve higher discriminability than showups supports the argument that lineups should be preferred to showups whenever possible. Using a showup, it is harder for eyewitnesses to tell the difference between innocent and guilty suspects, so there is never a reason for preferring a showup to a lineup when the police have the option of using either procedure.

In terms of discriminability, why are lineups superior to showups? One theory holds that witnesses do not appreciate that the face of the suspect, innocent or guilty, will necessarily match certain features of the witness’s memory of the perpetrator. For example, if the witness said that the crime was committed by a clean-shaven 20-year-old White male with dark hair and thick eyebrows (indicating that these features are in the witness’s memory), the suspect—innocent or guilty—will likely have those features. Thus, the memory-match signals generated by those features are nondiagnostic of the perpetrator’s identity and only add noise to the decision-making process. It is the remaining facial features (features that were not described but that are represented in the witness’s memory) that are diagnostic. Theoretically, a simultaneous lineup in which each person contains the features described by the witness immediately teaches the witness to disregard those shared (nondiagnostic) features and to focus instead on the other features to determine which of those match memory of the perpetrator. Doing so enhances discriminability ( Wixted & Mickes, 2014 ).

Maximizing Information

A low false alarm rate is generally regarded as being a desirable property of a lineup procedure because it is protective of innocent suspects. And, as just illustrated, for any given low false alarm rate, a lineup can achieve a higher hit rate than a showup can achieve (i.e., lineups yield higher discriminability). However, not everyone agrees that a low false alarm rate is an inherently desirable property of an eyewitness identification procedure. One price that is paid for keeping the false alarm rate low is that many lineup procedures yield no information at all about the suspect in the lineup because the lineup is often rejected (or a filler is identified). This includes lineups containing a guilty suspect. Imagine, for example, a witness who will not identify someone from the lineup unless they are at least 90% sure of being correct. Further imagine that the guilty suspect is in the lineup and that the witness is 85% sure he is the one who committed the crime. Using a standard lineup procedure, the witness will reject the lineup, and the police will never know that the witness could have told them that there is a good chance that their suspect is in fact the perpetrator.

In an ideal world, the lineup procedure would not miss out on useful information like that. For example, instead of using a lineup, the police might want to use a showup procedure after all, perhaps with instructions that encourage a liberal response bias (e.g., Smith et al., 2019 ). Under those conditions, many suspect identifications would occur with some level of confidence, so information about the suspect would be obtained in most cases. Alternatively, instead of using a showup, witnesses could be asked to provide a confidence rating for everyone in the lineup ( Brewer et al., 2020 ). This procedure ensures that information about the degree to which the suspect matches memory of the perpetrator is obtained from every lineup (because the suspect always receives a confidence rating). Still another possibility would be to take a perceptual scaling approach to reveal the structure of the eyewitness’s memory for the faces in a lineup ( Gepshtein et al., 2020 ). This approach is unique in that it takes the decision out of the hands of the witness and puts into the hands of the memory expert after the degree to which the suspect stands out from the fillers in the eyewitness’s memory is measured.

For the foreseeable future, it seems likely that the police will continue to use lineups. So long as they do, maximizing discriminability is a reasonable goal. This means preferring lineups to showups whenever possible. In addition, according to a review of published and unpublished studies, Mickes and Wixted (in press) found that simultaneous lineups (faces shown all at once) reliably yield higher discriminability than sequential lineups (faces shown one at a time). Theoretically, this might reflect the same feature-discounting process that explains why simultaneous lineups are superior to showups; that is, nondiagnostic facial features are more easily and appropriately discounted when the faces are shown simultaneously compared to when they are shown sequentially. Whether or not that is true, because it empirically achieves higher discriminability, it is reasonable for the police to prefer the simultaneous procedure to the sequential procedure. Eventually, however, should the information maximizing approach be empirically shown to yield superior outcomes, it is possible to imagine one of those approaches (e.g., perceptual scaling) ultimately replacing the standard lineup approach.

Test a Witness’s Memory for a Suspect Only Once

There is one additional recommendation for conducting lineups or showups that warrants special consideration. For the first time in any publication expressing a scientific consensus, the explicit recommendation was made to avoid repeated tests of a suspect beyond the first test ( Wells et al., 2020 ). More specifically, Recommendation #8 is termed the “Avoid Repeated Identifications Recommendation” and reads as follows: “Repeating an identification procedure with the same suspect and same eyewitness should be avoided regardless of whether the eyewitness identified the suspect in the initial identification procedure” (p. 8). The justification for this novel recommendation was described as follows:

This recommendation holds no matter how compelling the argument in favor of a second identification might seem (e.g., the original photo of the suspect was not as good as it could have been; the witness was nervous during the first identification test and is calmer now; the initial identification was made from a social media profile, but it would be more desirable to have an identification made using proper police procedures). The importance of focusing on the first identification test cannot be emphasized strongly enough . . . eyewitness identification evidence has a unique characteristic that makes it unsuitable for what might be called “repeated testing.” Whether the eyewitness is asked to make an identification with a showup or a lineup, there is only one uncontaminated opportunity for a given eyewitness to make an identification of a particular suspect. Any subsequent identification test with that same eyewitness and that same suspect is contaminated by the eyewitness’s experience on the initial test . ( Wells et al., 2020 , p. 25, emphasis added)

In other words, testing memory for a suspect changes the witness’s memory for that suspect. Assuming a recognizable photo of the suspect and a good faith attempt on the part of the eyewitness to make an identification, this is unavoidably true ( Wixted et al., 2021 ). If the suspect is innocent, it is the first time the witness is seeing that face. Moreover, seeing that face creates a new memory record of it in face-processing regions of the brain at a time when the witness happens to be thinking about the crime. As a result, the memory record of the innocent suspect’s face will also be associated with the activated memory of the crime. This occurs even if the witness rejects the lineup or picks a filler. Even then, a memory of the suspect has been formed and associated with memories of the crime. It is why no second test can provide more reliable information than the first. Why rely on a second test that is prejudicial to the potentially innocent suspect when only the first test can provide a clean and fair test of the witness’s uncontaminated memory?

The idea that it is essential to test a witness’s memory for a suspect only once is counterintuitive to many. After all, everyone has had the experience of failing to recall a detail (e.g., someone’s name) and then successfully recalling that detail when trying to do so again at some later point, perhaps even days or weeks later. However, this common experience involves recalling information from memory. Unlike face recognition, recall involves a memory search process. A search process can take a long time to succeed on the first test, or it can fail on the first test and then succeed on a later test. As noted earlier, the latter phenomenon is known as reminiscence. A failed memory search on a first test of recall does not contaminate memory because nothing happened to change the witness’s memory.

However, face recognition is not like that. No search of memory is required because the sought-after information (the face) is physically presented to the witness as part of the photo lineup. As noted earlier, if the suspect is guilty, the sensory information generated by that face will activate the same brain region where the memory of the perpetrator’s face was stored when the facial information was originally processed during the crime. It is not a search process that is extended in time and that can fail on the first try and then succeed on a later try. Because it is not a search process, if it succeeds, it will happen within seconds (not minutes). Moreover, if it fails on the first try, it means that the face of the suspect does not match memory.

To reiterate: Assuming good faith on the part of the witness and a recognizable photo of the suspect, if face recognition does not succeed within seconds of seeing the suspect’s face, it means that the suspect’s face does not match the witness’s memory. Period. This can happen because the witness failed to form a memory of the perpetrator’s face, in which case the suspect’s face would not match memory even if the suspect is guilty, or because the witness did form a memory of the perpetrator’s face, but the suspect is innocent. Either way, if the same suspect’s face that failed to match memory on the first test matches memory on a later test, it is a tell-tale sign that the witness’s memory was contaminated, not a sign that the witness “found” a face memory that they searched for and failed to find on the first test. It is not possible to overstate the importance of this point.

Although the first test of an eyewitness’s memory unavoidably contaminates the witness’s memory for the suspect, once again, it is obviously not the only source of memory contamination. In the weeks and months following the first test, if the police maintain their focus on the suspect, the witness might encounter the suspect’s face again multiple times. For example, the suspect’s face might appear on the news or might be seen in pretrial hearings, or the witness might search for his face in other ways (e.g., on social media). When the witness does finally identify the suspect (perhaps after initially rejecting the lineup), the police might also provide feedback to the witness indicating that it was the correct choice, thereby increasing the witness’s confidence beyond what it otherwise would be ( Wells & Bradfield, 1998 ). Meanwhile, if the suspect is innocent, the memory of the actual perpetrator’s face will be steadily fading away (having been seen only once at the time of the crime).

Again, the key point is that if face recognition of the suspect fails on the first test and then seems to succeed on any later test, it is a tell-tale sign of memory contamination, not a sign of a successful search of memory that previously failed. The failure to appreciate that simple fact appears to be the main reason why so many people are under the impression that eyewitness memory is inherently unreliable. In his book Convicting the innocent: Where criminal prosecutions go wrong , Garrett (2011) analyzed trial materials for 161 DNA exonerees who had been misidentified by one or more eyewitnesses in a court of law. In every case, the eyewitness testified with high confidence at trial that the defendant was the perpetrator. Testifying with high confidence at trial is the norm. However, identifications that occur at trial are not initial identifications, which, as known now, are the uniquely informative identifications. Thus, the question of interest is what happened on the first test (conducted early in the police investigation), not the last test (conducted in front of the judge and jury, at trial, long after memory was contaminated). The first test changes memory, so if the witness made a good faith attempt to recognize the perpetrator from a photo lineup containing a recognizable photo of the suspect, the results of no later test can serve the cause of justice better than the results of the first test.

Critically, in 57% of the DNA exoneration cases in which an innocent defendant was known to have been misidentified in court by an eyewitness, there was testimony about the outcome of the initial memory test. As Garrett (2011) put it:

I expected to read that these eyewitnesses were certain at trial that they had identified the right person. They were. I did not expect, however, to read testimony by witnesses at trial indicating that they earlier had trouble identifying the defendants. Even if there had been problems, eyewitnesses might not recall their hesitance at the time they first identified the defendant. Yet in 57% of these trial transcripts (92 of 161 cases), the witnesses reported that they had not been certain at the time of their earlier identifications. (p. 49, emphasis in original)

Thus, it seems that the key mistake in these cases was not made by the eyewitnesses after all. Instead, the key mistake was made by the criminal justice system, which did not keep its focus on the results of the first (and uniquely informative) test. Had the focus been placed on the outcome of the first test, many of the DNA exoneration cases that are ordinarily attributed to the unreliability of eyewitness memory may not have resulted in a conviction. The reason is that eyewitness identification evidence would not have played a significant role at the trial because, on the first test, that evidence was inconclusive at best.

Disregard the Witness’s Explanation for Why a Face Recognition Decision Changed

Unfortunately, Key et al. (2022) recently found that mock jurors tended to vote “guilty” when the eyewitness’s confidence was high, regardless of when the confidence judgment was made (initially or at trial) or whether there were inconsistencies in the confidence levels. This is consistent with the DNA exonerations cases reviewed by Garrett (2011) . Almost always, jurors focus on how certain the eyewitness appears at trial, long after their memory has been contaminated (unbeknownst either to the eyewitness or to the jury). Research into why that is suggests that jurors believe that virtually any excuse provided by the witness justifies removing the focus from the first test and placing it instead on the last test ( Jones et al., 2008 ). As observed by Key et al. (2022) : “Jurors need a more nuanced appreciation of the role of eyewitness confidence, and we discuss ideas for potential interventions that may aid jurors’ decision making.” The focus should be kept on the first test, regardless of how a witness rationalizes why they are confident now even though they were not confident on the first test.

These considerations underscore another point that also cannot be emphasized strongly enough. As noted earlier, face recognition memory does not fail and later succeed, and this remains true no matter how the witness rationalizes the difference between what they said on the first test and what they later say in court . Witnesses at trial are not aware that they are misidentifying an innocent suspect with high confidence because their memory was contaminated. How could they know? What they do know is their current high confidence was not present on the first test, and coming up with a believable explanation of why that is turns out to be surprisingly easy to do. For example, the witness might say “I was nervous on the first,” or “I did not think carefully on the first test and later searched my memory more carefully,” or “I had an epiphany during a dream” ( Jones et al., 2008 ). Unfortunately, the witness’s rationalization of the apparent discrepancy makes sense not only to the witness but also to the judge and jury ( Key et al., 2022 ).

In light of these considerations, it seems fair to say that the controllable mistake made in many of the wrongful convictions later overturned by DNA evidence was not a mistake made by the eyewitnesses; instead, the controllable mistake was the failure of triers of fact to focus on the results of the first test only.

Under the Right Conditions, Eyewitness Memory Is Highly Reliable

Testing a witness’s memory early in a police investigation (thereby minimizing the chances that memory has been contaminated) using a proper interview or a proper photo lineup yields a benefit that was only recently fully appreciated. The benefit is that under those conditions, eyewitness memory is highly reliable, not unreliable. It is reliable in the sense that what is recalled or recognized with high confidence tends to be highly accurate. Yet, even under these ideal conditions, what is recalled or recognized with low confidence is unreliable. A witness who expresses low confidence is essentially saying “there is a good chance I am wrong,” and the evidence shows that they are right about that. If only the police would listen to them and stop right there (never testing the witness’s memory for the same suspect again), it is possible that no one would have ever come to believe that eyewitness memory is inherently unreliable.

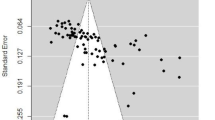

To say that eyewitness memory is reliable on the first, properly conducted test is to say that the relationship between confidence and accuracy is strong (i.e., low confidence implies low accuracy, whereas high confidence implies high accuracy). Consider, for example, studies testing recall using open-ended, nonleading questions, which were recently reviewed by Wixted and Mickes (2022) . In a study by Roberts and Higham (2002) , participants watched a videotape of a simulated robbery and were interviewed a week later about their recollections of the event. Confidence for each recalled detail was collected using a 1 to 7 scale. As shown in figure 1 , confidence was strongly related to accuracy.

Figure 1. Accuracy (percent correct) as a function of confidence for the interview recall data reported by Roberts and Higham (2002) . The overall number of correct details (considered relevant to an investigation) and incorrect details was estimated for each level of confidence from their Figure 1 and then the probability that a recalled detail was correct was computed for each level of confidence. Error bars represent standard error.

In a later study by Odinot et al. (2013) , participants watched a television show about an accident between a car and a motorcycle. One, three, or five weeks later, they completed a questionnaire consisting of 28 open-ended questions, and they rated their confidence in each recalled detail using a 7-point scale. The results showed not only that confidence was strongly indicative of accuracy, but high confidence implied high accuracy in all three conditions (figure 2 ).

Figure 2. Accuracy (percent correct) as a function of confidence estimated from the interview recall data when recall took place 1, 3, or 5 weeks after encoding reported in Figure 1 of Odinot et al. (2013) .

In related work, Spearing and Wade (2021) asked participants to recall details from a mock-crime video they had previously viewed. The participants rated confidence immediately following each freely recalled detail (Immediate) or after all information had first been recalled (Delayed). As usual, the relationship between confidence and accuracy was strong, and this was true of both conditions (figure 3 ).

Figure 3. Accuracy (percent correct) as a function of confidence for the interview recall data reported by Spearing and Wade (2021) . The data were estimated from their Figure 4 (Experiment 3). Experiment 3 was deemed by the authors to be the most forensically relevant of the three experiments they reported because it involved a free recall narrative report. The diagonal line represents a perfect confidence–accuracy relationship.

The studies discussed were laboratory studies. In a study of actual eyewitnesses to a crime, Odinot et al. (2009) interviewed witnesses of an armed robbery that was recorded by multiple security cameras, and the recordings were used to verify the recalled information. The witnesses were interviewed 3 months after the crime, which is not ideal because considerable memory contamination can occur over that period (e.g., from conversations between witnesses or TV coverage). Yet figure 4 shows that proportion correct increased from .61 to .85 as confidence increased from low to high. These numbers might be even more impressive had the interviews been conducted immediately after the crime, minimizing the opportunity for memory contamination.

Figure 4. Observed relationship between percentage of recalled details that were correct and confidence. The data are from Odinot et al. (2009) . Error bars represent standard error.

The same story applies to eyewitness memory initially tested by recognition using a proper lineup procedure ( Wells et al., 2020 ). The attempt to measure that relationship has a long and complicated history, but the short story is that prior efforts using a correlation or calibration approach were misleading. The question of primary interest to triers of fact is the relationship between confidence and accuracy for suspect identifications (leaving out witnesses who identify a filler or reject the lineup). Plotting a confidence–accuracy relationship for suspect identifications is known as a confidence–accuracy characteristic (CAC) plot ( Mickes, 2015 ).

Wixted and Wells (2017) reviewed the literature, replotting all the previously collected correlation and calibration data in terms of CAC. As shown in figure 5 , confidence is strongly predictive of accuracy, with high-confidence suspect identification being very accurate.

Figure 5. Suspect identification accuracy (percent correct) as a function of confidence averaged across 15 studies with comparable scaling on the confidence (x) axis ( Wixted & Wells, 2017 ). Error bars represent standard error.

According to a recent study of actual eyewitnesses making identifications from properly administered fair lineups ( Wixted, Mickes, et al., 2016 ), these results generalize to the real world (figure 6 ).

Figure 6. Estimated suspect identification accuracy (percent correct) as a function of confidence for the data from the Houston Police Department field study ( Wixted, Mickes, et al., 2016 ). The crimes were robberies, the lineups were fair, the lineups were administered by an officer who was blind to the identity of the suspect, and the suspects in the lineups were not previously known to the witnesses.

Interestingly, for tests of eyewitness identification, the confidence–accuracy relationship remains strong whether the retention interval (the time between the witnessed crime and the first eyewitness identification test) is short or long. As noted earlier, when memory is tested by recall, the longer the retention interval, the more opportunity there is for memory to be contaminated (e.g., from conversations with other witnesses, hearing rumors). Although the same principle applies to a test of eyewitness identification, memory is much less likely to be contaminated by the mere passage of time. The reason is that, with regard to eyewitness identification, what contaminates the witness’s memory is encountering the face of the suspect who will later appear in a lineup. Conversations with other witnesses or hearing rumors about the crime usually have no contaminating effect on eyewitness identification because the face of the innocent suspect is not encountered (so a memory of the face is not created in the face processing regions of the brain). Moreover, no matter how long the retention interval is, it is unlikely that the witness will encounter the face of the same innocent suspect who the police will later come to suspect and place in a lineup. In agreement with this way of thinking, the length of the retention interval has little effect on the confidence–accuracy relationship for retention intervals as long as 9 months ( Wixted, Read, et al., 2016 ).

The take-home message seems almost inescapable: Always focus on the first good faith, properly conducted test of an eyewitness’s memory, and never ignore the level of confidence expressed by the witness on that test. Low confidence implies low accuracy, and by expressing low confidence, the witness is making it clear to police investigators that what is being reported from memory stands a good chance of being wrong. But if confidence is high, and if the test was properly conducted, what is remembered by an honest eyewitness on the first test is likely to be highly reliable. Such words have rarely been used to describe eyewitness memory, but the data (some of which was summarized here) are consistent with this more nuanced understanding. As it turns out, as with other types of forensic evidence, eyewitness memory is reliable under some conditions and unreliable under other conditions. The job of judges and jurors is to determine, for any given case, which set of conditions applies. Doing so serves the cause of justice by imperiling the guilty and protecting the innocent.

Further Reading

- Spearing, E. R. , & Wade, K. A. (2021). Providing eyewitness confidence judgements during versus after eyewitness interviews does not affect the confidence-accuracy relationship . Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition , 11 , 54–65.

- Wells, G. L. , Kovera, M. B. , Douglass, A. B. , Brewer, N. , Meissner, C. A. , & Wixted, J. T. (2020). Policy and procedure recommendations for the collection and preservation of eyewitness identification evidence. Law and Human Behavior , 44 , 3–36.

- Wixted, J. T. , & Mickes, L. (2022). Eyewitness memory is reliable, but the criminal justice system is not. Memory , 30 , 67–72.

- Wixted, J. T. , & Wells, G. L. (2017). The relationship between eyewitness confidence and identification accuracy: A new synthesis. Psychological Science in the Public Interest , 18 , 10–65.

- Wixted, J. T. , Wells, G. L. , Loftus, E. F. , & Garrett, B. L. (2021). Test a witness's memory of a suspect only once . Psychological Science in the Public Interest , 22 (1_suppl), 1S–18S.

- Aldridge, J. , & Cameron, S. (1999). Interviewing child witnesses: Questioning techniques and the role of training. Applied Developmental Science , 3 , 136–147.

- Baym, C. L. , & Gonsalves, B. D. (2010). Comparison of neural activity that leads to true memories, false memories, and forgetting: An fMRI study of the misinformation effect. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience , 10 (3), 339–348.

- Bernstein, D. M. , & Loftus, E. F. (2009). How to tell if a particular memory is true or false. Perspectives on Psychological Science , 4 , 370–374.

- Brewer, N. , Weber, N. , & Guerin, N. (2020). Police lineups of the future? American Psychologist , 75 (1), 76–91.

- Brodt, S. , & Gais, S. (2021). Memory engrams in the neocortex. The Neuroscientist , 27 ( 4 ), 427–444.

- Colloff, M. F. , Wade, K. A. , Strange, D. , & Wixted, J. T. (2018). Filler-siphoning theory does not predict the effect of lineup fairness on the ability to discriminate innocent from guilty suspects: Reply to Smith, Wells, Smalarz, and Lampinen (2018). Psychological Science , 29 (9), 1552–1557.

- Earhart, B. , La Rooy, D. J. , Brubacher, S. P. , & Lamb, M. F. (2014). An examination of “don't know” responses in forensic interviews with children. Behavioral Sciences & the Law , 32 , 746–761.

- Fisher, R. P. , & Geiselman, R. E. (1992). Memory-enhancing techniques for investigative interviewing: The cognitive interview . Charles C. Thomas.

- Freeman, K. A. , & Morris, T. L. (1999). Investigative interviewing with children: Evaluation of the effectiveness of a training program for child protective service workers. Child Abuse & Neglect , 23 , 701–713.

- Garrett, B. (2011). Convicting the innocent: Where criminal prosecutions go wrong . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Garry, M. , & Polaschek, D. L. L. (2000). Imagination and memory. Current Directions in Psychological Science , 9 , 6–10.

- Garven, S. , Wood, J. M. , Malpass, R. S. , & Shaw, J. S., III (1998). More than suggestion: The effect of interviewing techniques from the McMartin Preschool case. Journal of Applied Psychology , 83 (3), 347–359.

- Gepshtein, S. , Wang, Y. , He, F. , Diep, D. , & Albright, T. D. (2020). A perceptual scaling approach to eyewitness identification. Nature Communications , 11 (1), 3380.

- Gronlund, S. D. , Carlson, C. A. , Neuschatz, J. S. , Goodsell, C. A. , Wetmore, S. A. , Wooten, A. , & Graham, M. (2012). Showups versus lineups: An evaluation using ROC analysis. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition , 1 (4), 221–228.

- Hyman, I. E. , & Billings, J. F., Jr. (1998). Individual differences and the creation of false childhood memories. Memory , 6 , 1–20.

- Jones, E. E. , Williams, K. D. , & Brewer, N. (2008). “I had a confidence epiphany!”: Obstacles to combating post-identification confidence inflation. Law and Human Behavior , 32 (2), 164–176.

- Key, K. N. , Neuschatz, J. S. , Gronlund, S. D. , Deloach, D. , Wetmore, S. A. , McAdoo, R. M. , & McCollum, D. (2022). High eyewitness confidence is always compelling: That’s a problem . Psychology, Crime & Law . Advance online publication.

- Lamb, M. E. , Orbach, Y. , Hershkowitz, I. , Horowitz, D. , & Abbott, C. B. (2007). Does the type of prompt affect the accuracy of information provided by alleged victims of abuse in forensic interviews? Applied Cognitive Psychology , 21 , 1117–1130.

- Lindsay, D. S. , Hagen, L. , Read, J. D. , Wade, K. A. , & Garry, M. (2004). True photographs and false memories. Psychological Science , 15 , 149–154.

- Loftus, E. F. , Miller, D. G. , & Burns, H. J. (1978). Semantic integration of verbal information into a visual memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory , 4 , 19–31.

- Loftus, E. F. , & Palmer, J. C. (1974). Reconstruction of automobile destruction: An example of the interaction between language and memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior , 13 , 585–589.

- Loftus, E. F. , & Pickrell, J. E. (1995). The formation of false memories. Psychiatric Annals , 25 , 720–725.

- Mazzoni, G. A. L. , & Memon, A. (2003). Imagination can create false autobiographical memories. Psychological Science , 14 , 186–188.

- Mickes, L. (2015). Receiver operating characteristic analysis and confidence-accuracy characteristic analysis in investigations of system variables and estimator variables that affect eyewitness memory. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition , 4 , 93–102.

- Mickes, L. , & Wixted, J. T. (In press). Eyewitness memory. In M. J. Kahana & A. D. Wagner (Eds.), Oxford handbook of human memory . Oxford University Press.

- National Institute of Justice . (1999). Eyewitness evidence a guide for law enforcement .

- Odinot, G. , Wolters, G. , & van Giezen, A. (2013). Accuracy, confidence and consistency in repeated recall of events. Psychology, Crime & Law , 19 , 629–642.

- Odinot, G. , Wolters, G. , & van Koppen, P. J. (2009). Eyewitness memory of a supermarket robbery: A case study of accuracy and confidence after 3 months. Law and Human Behavior , 33 , 506–514.

- Orbach, Y. , Hershkowitz, I. , Lamb, M. E. , Sternberg, K. J. , Esplin, P. W. , & Horowitz, D. (2000). Assessing the value of structured protocols for forensic interviews of alleged abuse victims. Child Abuse & Neglect , 24 , 733–752.

- Pendergrast, M. (2017). The repressed memory epidemic: How it happened and what we need to learn from it . Springer.

- Pezdek, K. , & Roe, C. (1995). The effect of memory trace strength on suggestibility. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology , 60 (1), 116–128.

- Police Executive Research Forum . (2013). A national survey of eyewitness identification procedures in law enforcement agencies .

- Price, H. L. , & Roberts, K. M. (2011). The effects of an intensive training and feedback program on police and social workers’ investigative interviews of children. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science , 43 , 235–244.

- Roberts, W. T. , & Higham, P. A. (2002). Selecting accurate statements from the cognitive interview using confidence ratings. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied , 8 , 33–43.

- Scrivner, E. , & Safer, M. A. (1988). Eyewitnesses show hypermnesia for details about a violent event. Journal of Applied Psychology , 73 (3), 371–377.

- Shaw, J. (2018). How can researchers tell whether someone has a false memory? Coding strategies in autobiographical false-memory research: A reply to Wade, Garry, and Pezdek (2018). Psychological Science , 29 , 477–480.

- Shaw, J. , & Porter, S. (2015). Constructing rich false memories of committing crime. Psychological Science , 26 , 291–301.

- Smith, A. M. , Lampinen, J. M. , Wells, G. L. , Smalarz, L. , & Mackovichova, S. (2019). Deviation from perfect performance measures the diagnostic utility of eyewitness lineups but partial area under the roc curve does not. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition , 8 (1), 50–59.

- Smith, A. M. , Wells, G. L. , Smalarz, L. , & Lampinen, J. M. (2018). Increasing the similarity of lineup fillers to the suspect improves the applied value of lineups without improving memory performance: Commentary on Colloff, Wade, and Strange (2016). Psychological Science , 29 , 1548–1551.

- Spearing, E. R. , & Wade, K. A. (2021). Providing eyewitness confidence judgements during versus after eyewitness interviews does not affect the confidence-accuracy relationship . Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition , 11 , 54–65..

- Talarico, J. M. , & Rubin, D. C. (2003). Confidence, not consistency, characterizes flashbulb memories. Psychological Science , 14 (5), 455–461.

- Wade, K. A. , Garry, M. , & Pezdek, K. (2018). Deconstructing rich false memories of committing crime: Commentary on Shaw and Porter (2015). Psychological Science , 29 , 471–476.

- Warren, A. R. , Woodall, C. E. , Thomas, M. , Nunno, M. , Keeney, J. M. , Larson, S. M. , & Stadfeld, J. A. (1999). Assessing the effectiveness of a training program for interviewing children. Applied Developmental Science , 3 , 128–135.

- Wells, G. L. , & Bradfield, A. L. (1998). "Good, you identified the suspect": Feedback to eyewitnesses distorts their reports of the witnessing experience. Journal of Applied Psychology , 83 (3), 360–376.

- Wheeler, M. A. , & Roediger, H. L. (1992). Disparate effects of repeated testing: Reconciling Ballard’s (1913) and Bartlett’s (1932) results. Psychological Science , 3 (4), 240–245.

- Wixted, J. T. , & Mickes, L. (2014). A signal-detection-based diagnostic feature-detection model of eyewitness identification. Psychological Review , 121 , 262–276.

- Wixted, J. T. , Mickes, L. , Dunn, J. C. , Clark, S. E. , & Wells, W. (2016). Estimating the reliability of eyewitness identifications from police lineups. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , 113 , 304–309.

- Wixted, J. T. , Mickes, L. , & Fisher, R. P. (2018). Rethinking the reliability of eyewitness memory. Perspectives on Psychological Science , 13 , 324–335.

- Wixted, J. T. , Read, J. D. , & Lindsay, D. S. (2016). The effect of retention interval on the eyewitness identification confidence-accuracy relationship. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition , 5 , 192–203.

- Wixted, J. T. , Wells, G. L. , Loftus, E. F. , & Garrett, B. L. (2021). Test a witness’s memory for a suspect only once . Psychological Science in the Public Interest , 22 (1_suppl), 1S–18S.

Related Articles

- Forensic Psychology in Historical Perspective

- Face Perception

- Jury Decision-Making

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Psychology. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 02 September 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [185.148.24.167]

- 185.148.24.167

Character limit 500 /500

June 13, 2017

Eyewitness Memory Is a Lot More Reliable Than You Think

What law enforcement—and the public—needs to know

By John Wixted & Laura Mickes

Getty Images

The ability of a person who witnesses a crime to later pick the perpetrator out of a lineup is atrocious—right? The answer seems like a resounding “yes” if you consider some well-known and rather disconcerting information. Eyewitness misidentifications are known to have played a role in 70 percent of the 349 wrongful convictions that have been overturned based on DNA evidence (so far). Psychologists have learned a lot about why such errors happen. With surprising ease, for example, participants in a memory experiment can be led to believe that they saw a stop sign when they actually saw a yield sign or that they became lost in a shopping mall as a child when no such experience actually occurred. In much the same way, an eyewitness can be led to falsely remember someone committing a crime that was actually committed by someone else.

But there is more to the story. Consider the important, and often overlooked, distinction between malleability and reliability. Just because memory is malleable—for example, it can be contaminated with the trace of an innocent person—does not mean that it has to be unreliable. What it means is that the malleability of memory can harm reliability. Once this fact is appreciated, then proper testing protocols can be put in place to minimize the likelihood that the original memory trace is contaminated.

Current procedures for collecting and assessing evidence from eyewitnesses are often not designed to minimize contamination.This problem does not apply to other kinds of forensic evidence. Imagine if police let unauthorized people have willy-nilly access to a crime scene that is under investigation. What would that mean for the reliability of the blood or fingerprint evidence, for example, collected at that scene? Blood and fingerprint evidence, per se, would not be deemed unreliable. Instead evidence collected at the contaminated crime scene would probably be declared inadmissible. Not so with eyewitness memory.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.