An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HCA Healthc J Med

- v.1(2); 2020

- PMC10324782

Introduction to Research Statistical Analysis: An Overview of the Basics

Christian vandever.

1 HCA Healthcare Graduate Medical Education

Description

This article covers many statistical ideas essential to research statistical analysis. Sample size is explained through the concepts of statistical significance level and power. Variable types and definitions are included to clarify necessities for how the analysis will be interpreted. Categorical and quantitative variable types are defined, as well as response and predictor variables. Statistical tests described include t-tests, ANOVA and chi-square tests. Multiple regression is also explored for both logistic and linear regression. Finally, the most common statistics produced by these methods are explored.

Introduction

Statistical analysis is necessary for any research project seeking to make quantitative conclusions. The following is a primer for research-based statistical analysis. It is intended to be a high-level overview of appropriate statistical testing, while not diving too deep into any specific methodology. Some of the information is more applicable to retrospective projects, where analysis is performed on data that has already been collected, but most of it will be suitable to any type of research. This primer will help the reader understand research results in coordination with a statistician, not to perform the actual analysis. Analysis is commonly performed using statistical programming software such as R, SAS or SPSS. These allow for analysis to be replicated while minimizing the risk for an error. Resources are listed later for those working on analysis without a statistician.

After coming up with a hypothesis for a study, including any variables to be used, one of the first steps is to think about the patient population to apply the question. Results are only relevant to the population that the underlying data represents. Since it is impractical to include everyone with a certain condition, a subset of the population of interest should be taken. This subset should be large enough to have power, which means there is enough data to deliver significant results and accurately reflect the study’s population.

The first statistics of interest are related to significance level and power, alpha and beta. Alpha (α) is the significance level and probability of a type I error, the rejection of the null hypothesis when it is true. The null hypothesis is generally that there is no difference between the groups compared. A type I error is also known as a false positive. An example would be an analysis that finds one medication statistically better than another, when in reality there is no difference in efficacy between the two. Beta (β) is the probability of a type II error, the failure to reject the null hypothesis when it is actually false. A type II error is also known as a false negative. This occurs when the analysis finds there is no difference in two medications when in reality one works better than the other. Power is defined as 1-β and should be calculated prior to running any sort of statistical testing. Ideally, alpha should be as small as possible while power should be as large as possible. Power generally increases with a larger sample size, but so does cost and the effect of any bias in the study design. Additionally, as the sample size gets bigger, the chance for a statistically significant result goes up even though these results can be small differences that do not matter practically. Power calculators include the magnitude of the effect in order to combat the potential for exaggeration and only give significant results that have an actual impact. The calculators take inputs like the mean, effect size and desired power, and output the required minimum sample size for analysis. Effect size is calculated using statistical information on the variables of interest. If that information is not available, most tests have commonly used values for small, medium or large effect sizes.

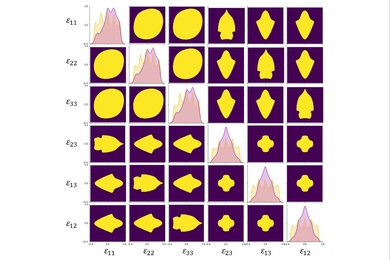

When the desired patient population is decided, the next step is to define the variables previously chosen to be included. Variables come in different types that determine which statistical methods are appropriate and useful. One way variables can be split is into categorical and quantitative variables. ( Table 1 ) Categorical variables place patients into groups, such as gender, race and smoking status. Quantitative variables measure or count some quantity of interest. Common quantitative variables in research include age and weight. An important note is that there can often be a choice for whether to treat a variable as quantitative or categorical. For example, in a study looking at body mass index (BMI), BMI could be defined as a quantitative variable or as a categorical variable, with each patient’s BMI listed as a category (underweight, normal, overweight, and obese) rather than the discrete value. The decision whether a variable is quantitative or categorical will affect what conclusions can be made when interpreting results from statistical tests. Keep in mind that since quantitative variables are treated on a continuous scale it would be inappropriate to transform a variable like which medication was given into a quantitative variable with values 1, 2 and 3.

Categorical vs. Quantitative Variables

Both of these types of variables can also be split into response and predictor variables. ( Table 2 ) Predictor variables are explanatory, or independent, variables that help explain changes in a response variable. Conversely, response variables are outcome, or dependent, variables whose changes can be partially explained by the predictor variables.

Response vs. Predictor Variables

Choosing the correct statistical test depends on the types of variables defined and the question being answered. The appropriate test is determined by the variables being compared. Some common statistical tests include t-tests, ANOVA and chi-square tests.

T-tests compare whether there are differences in a quantitative variable between two values of a categorical variable. For example, a t-test could be useful to compare the length of stay for knee replacement surgery patients between those that took apixaban and those that took rivaroxaban. A t-test could examine whether there is a statistically significant difference in the length of stay between the two groups. The t-test will output a p-value, a number between zero and one, which represents the probability that the two groups could be as different as they are in the data, if they were actually the same. A value closer to zero suggests that the difference, in this case for length of stay, is more statistically significant than a number closer to one. Prior to collecting the data, set a significance level, the previously defined alpha. Alpha is typically set at 0.05, but is commonly reduced in order to limit the chance of a type I error, or false positive. Going back to the example above, if alpha is set at 0.05 and the analysis gives a p-value of 0.039, then a statistically significant difference in length of stay is observed between apixaban and rivaroxaban patients. If the analysis gives a p-value of 0.91, then there was no statistical evidence of a difference in length of stay between the two medications. Other statistical summaries or methods examine how big of a difference that might be. These other summaries are known as post-hoc analysis since they are performed after the original test to provide additional context to the results.

Analysis of variance, or ANOVA, tests can observe mean differences in a quantitative variable between values of a categorical variable, typically with three or more values to distinguish from a t-test. ANOVA could add patients given dabigatran to the previous population and evaluate whether the length of stay was significantly different across the three medications. If the p-value is lower than the designated significance level then the hypothesis that length of stay was the same across the three medications is rejected. Summaries and post-hoc tests also could be performed to look at the differences between length of stay and which individual medications may have observed statistically significant differences in length of stay from the other medications. A chi-square test examines the association between two categorical variables. An example would be to consider whether the rate of having a post-operative bleed is the same across patients provided with apixaban, rivaroxaban and dabigatran. A chi-square test can compute a p-value determining whether the bleeding rates were significantly different or not. Post-hoc tests could then give the bleeding rate for each medication, as well as a breakdown as to which specific medications may have a significantly different bleeding rate from each other.

A slightly more advanced way of examining a question can come through multiple regression. Regression allows more predictor variables to be analyzed and can act as a control when looking at associations between variables. Common control variables are age, sex and any comorbidities likely to affect the outcome variable that are not closely related to the other explanatory variables. Control variables can be especially important in reducing the effect of bias in a retrospective population. Since retrospective data was not built with the research question in mind, it is important to eliminate threats to the validity of the analysis. Testing that controls for confounding variables, such as regression, is often more valuable with retrospective data because it can ease these concerns. The two main types of regression are linear and logistic. Linear regression is used to predict differences in a quantitative, continuous response variable, such as length of stay. Logistic regression predicts differences in a dichotomous, categorical response variable, such as 90-day readmission. So whether the outcome variable is categorical or quantitative, regression can be appropriate. An example for each of these types could be found in two similar cases. For both examples define the predictor variables as age, gender and anticoagulant usage. In the first, use the predictor variables in a linear regression to evaluate their individual effects on length of stay, a quantitative variable. For the second, use the same predictor variables in a logistic regression to evaluate their individual effects on whether the patient had a 90-day readmission, a dichotomous categorical variable. Analysis can compute a p-value for each included predictor variable to determine whether they are significantly associated. The statistical tests in this article generate an associated test statistic which determines the probability the results could be acquired given that there is no association between the compared variables. These results often come with coefficients which can give the degree of the association and the degree to which one variable changes with another. Most tests, including all listed in this article, also have confidence intervals, which give a range for the correlation with a specified level of confidence. Even if these tests do not give statistically significant results, the results are still important. Not reporting statistically insignificant findings creates a bias in research. Ideas can be repeated enough times that eventually statistically significant results are reached, even though there is no true significance. In some cases with very large sample sizes, p-values will almost always be significant. In this case the effect size is critical as even the smallest, meaningless differences can be found to be statistically significant.

These variables and tests are just some things to keep in mind before, during and after the analysis process in order to make sure that the statistical reports are supporting the questions being answered. The patient population, types of variables and statistical tests are all important things to consider in the process of statistical analysis. Any results are only as useful as the process used to obtain them. This primer can be used as a reference to help ensure appropriate statistical analysis.

Funding Statement

This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares he has no conflicts of interest.

Christian Vandever is an employee of HCA Healthcare Graduate Medical Education, an organization affiliated with the journal’s publisher.

This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities.

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Report Statistics

Ensure appropriateness and rigor, avoid flexibility and above all never manipulate results

In many fields, a statistical analysis forms the heart of both the methods and results sections of a manuscript. Learn how to report statistical analyses, and what other context is important for publication success and future reproducibility.

A matter of principle

First and foremost, the statistical methods employed in research must always be:

Appropriate for the study design

Rigorously reported in sufficient detail for others to reproduce the analysis

Free of manipulation, selective reporting, or other forms of “spin”

Just as importantly, statistical practices must never be manipulated or misused . Misrepresenting data, selectively reporting results or searching for patterns that can be presented as statistically significant, in an attempt to yield a conclusion that is believed to be more worthy of attention or publication is a serious ethical violation. Although it may seem harmless, using statistics to “spin” results can prevent publication, undermine a published study, or lead to investigation and retraction.

Supporting public trust in science through transparency and consistency

Along with clear methods and transparent study design, the appropriate use of statistical methods and analyses impacts editorial evaluation and readers’ understanding and trust in science.

In 2011 False-Positive Psychology: Undisclosed Flexibility in Data Collection and Analysis Allows Presenting Anything as Significant exposed that “flexibility in data collection, analysis, and reporting dramatically increases actual false-positive rates” and demonstrated “how unacceptably easy it is to accumulate (and report) statistically significant evidence for a false hypothesis”.

Arguably, such problems with flexible analysis lead to the “ reproducibility crisis ” that we read about today.

A constant principle of rigorous science The appropriate, rigorous, and transparent use of statistics is a constant principle of rigorous, transparent, and Open Science. Aim to be thorough, even if a particular journal doesn’t require the same level of detail. Trust in science is all of our responsibility. You cannot create any problems by exceeding a minimum standard of information and reporting.

Sound statistical practices

While it is hard to provide statistical guidelines that are relevant for all disciplines, types of research, and all analytical techniques, adherence to rigorous and appropriate principles remains key. Here are some ways to ensure your statistics are sound.

Define your analytical methodology before you begin Take the time to consider and develop a thorough study design that defines your line of inquiry, what you plan to do, what data you will collect, and how you will analyze it. (If you applied for research grants or ethical approval, you probably already have a plan in hand!) Refer back to your study design at key moments in the research process, and above all, stick to it.

To avoid flexibility and improve the odds of acceptance, preregister your study design with a journal Many journals offer the option to submit a study design for peer review before research begins through a practice known as preregistration. If the editors approve your study design, you’ll receive a provisional acceptance for a future research article reporting the results. Preregistering is a great way to head off any intentional or unintentional flexibility in analysis. By declaring your analytical approach in advance you’ll increase the credibility and reproducibility of your results and help address publication bias, too. Getting peer review feedback on your study design and analysis plan before it has begun (when you can still make changes!) makes your research even stronger AND increases your chances of publication—even if the results are negative or null. Never underestimate how much you can help increase the public’s trust in science by planning your research in this way.

Imagine replicating or extending your own work, years in the future Imagine that you are describing your approach to statistical analysis for your future self, in exactly the same way as we have described for writing your methods section . What would you need to know to replicate or extend your own work? When you consider that you might be at a different institution, working with different colleagues, using different programs, applications, resources — or maybe even adopting new statistical techniques that have emerged — you can help yourself imagine the level of reporting specificity that you yourself would require to redo or extend your work. Consider:

- Which details would you need to be reminded of?

- What did you do to the raw data before analysis?

- Did the purpose of the analysis change before or during the experiments?

- What participants did you decide to exclude?

- What process did you adjust, during your work?

Even if a necessary adjustment you made was not ideal, transparency is the key to ensuring this is not regarded as an issue in the future. It is far better to transparently convey any non-optimal techniques or constraints than to conceal them, which could result in reproducibility or ethical issues downstream.

Existing standards, checklists, guidelines for specific disciplines

You can apply the Open Science practices outlined above no matter what your area of expertise—but in many cases, you may still need more detailed guidance specific to your own field. Many disciplines, fields, and projects have worked hard to develop guidelines and resources to help with statistics, and to identify and avoid bad statistical practices. Below, you’ll find some of the key materials.

TIP: Do you have a specific journal in mind?

Be sure to read the submission guidelines for the specific journal you are submitting to, in order to discover any journal- or field-specific policies, initiatives or tools to utilize.

Articles on statistical methods and reporting

Makin, T.R., Orban de Xivry, J. Science Forum: Ten common statistical mistakes to watch out for when writing or reviewing a manuscript . eLife 2019;8:e48175 (2019). https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.48175

Munafò, M., Nosek, B., Bishop, D. et al. A manifesto for reproducible science . Nat Hum Behav 1, 0021 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-016-0021

Writing tips

Your use of statistics should be rigorous, appropriate, and uncompromising in avoidance of analytical flexibility. While this is difficult, do not compromise on rigorous standards for credibility!

- Remember that trust in science is everyone’s responsibility.

- Keep in mind future replicability.

- Consider preregistering your analysis plan to have it (i) reviewed before results are collected to check problems before they occur and (ii) to avoid any analytical flexibility.

- Follow principles, but also checklists and field- and journal-specific guidelines.

- Consider a commitment to rigorous and transparent science a personal responsibility, and not simple adhering to journal guidelines.

- Be specific about all decisions made during the experiments that someone reproducing your work would need to know.

- Consider a course in advanced and new statistics, if you feel you have not focused on it enough during your research training.

Don’t

- Misuse statistics to influence significance or other interpretations of results

- Conduct your statistical analyses if you are unsure of what you are doing—seek feedback (e.g. via preregistration) from a statistical specialist first.

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

- EXPLORE Random Article

How to Find Statistics for a Research Paper

Last Updated: March 10, 2024 References

This article was co-authored by wikiHow staff writer, Jennifer Mueller, JD . Jennifer Mueller is a wikiHow Content Creator. She specializes in reviewing, fact-checking, and evaluating wikiHow's content to ensure thoroughness and accuracy. Jennifer holds a JD from Indiana University Maurer School of Law in 2006. There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been viewed 24,724 times.

When you're writing a research paper, particularly in social sciences such as political science or sociology, statistics can help you back up your conclusions with solid data. You typically can find relevant statistics using online sources. However, it's important to accurately assess the reliability of the source. You also need to understand whether the statistics you've found strengthen or undermine your arguments or conclusions before you incorporate them into your writing. [1] X Research source [2] X Trustworthy Source University of North Carolina Writing Center UNC's on-campus and online instructional service that provides assistance to students, faculty, and others during the writing process Go to source

Identifying the Data You Need

- For example, if you're writing a research paper for a sociology class on the effect of crime in inner cities, you may want to make the point that high school graduation rates decrease as the rate of violent crime increases.

- To support that point, you would need data about high school graduation rates in specific inner cities, as well as violent crime rates in the same areas.

- From that data, you would want to find statistics that show the trends in those two rates. Then you can compare those statistics to reach a correlation that would (potentially) support your point.

- Background research also can clue you in to words or phrases that are commonly used by academics, researchers, and statisticians examining the same issues you're discussing in your research paper.

- A basic familiarity with your topic can help you identify additional statistics that you might not have thought of before.

- For example, in reading about the effect of violent crime in inner cities, you may find an article discussing how children coming from high-crime neighborhoods have higher rates of PTSD than children who grow up in peaceful suburbs.

- The issue of PTSD is something you potentially could weave into your research paper, although you'd have to do more digging into the source of the statistics themselves.

- Keep in mind when you're reading on background, this isn't necessarily limited to material that you might use as a source for your research paper. You're just trying to familiarize yourself with the subject generally.

- With a descriptive statistic, those who collected the data got information for every person included in a specific, limited group.

- "Only 2 percent of the students in McKinley High School's senior class have red hair" is an example of a descriptive statistic. All the students in the senior class have been accounted for, and the statistic describes only that group.

- However, if the statisticians used the county high school's senior class as a representative sample of the county as a whole, the result would be an inferential statistic.

- The inferential version would be phrased "According to our study, approximately 2 percent of the people in McKinley County have red hair." The statisticians didn't check the hair color of every person who lived in the county.

- Finding the best key words can be an art form. Using what you learned from your background research, try to use words academics or other researchers in the field use when discussing your topic.

- You not only want to search for specific words, but also synonyms for those words. You also might search for both broader categories and narrower examples of related phenomena.

- For example, "violent crime" is a broad category that may include crimes such as assault, rape, and murder. You may not be able to find statistics that specifically track violent crime generally, but you should be able to find statistics on the murder rate in a given area.

- If you're looking for statistics related to a particular geographic area, you'll need to be flexible there as well. For example, if you can't find statistics that relate solely to a particular neighborhood, you may want to expand outward to the city or even the county.

- While you can run a general internet search using your key words to potentially find statistics you can use in your research paper, knowing specific sources can help you find reliable statistics more quickly.

- For example, if you're looking for statistics related to various demographics in the United States, the U.S. government has many statistics available at www.usa.gov/statistics.

- You also can check the U.S. Census Bureau's website to retrieve census statistics and data.

- The NationMaster website collects data from the CIA World Factbook and other sources to create a wealth of statistics comparing different countries on a number of measures.

Evaluating Sources

- Find out who was responsible for collecting the data, and why. If the organization or group behind the data collection and creation of the statistics has an ideological or political mission, their statistics may be suspect.

- Essentially, if someone is creating statistics to support a particular position or prove their arguments, you cannot trust those statistics. There are many ways raw data can be manipulated to show trends or correlations that don't necessarily reflect reality.

- Government sources typically are highly reliable, as are most university studies. However, even with university studies you want to see if the study was funded in whole or in part by a group or organization with an ideological or political motivation or bias.

- To explore the background adequately, use the journalistic standard of the "5 w's" – who, what, when, where, and why.

- This means you'll want to find out who carried out the study (or, in the case of a poll, who asked the questions), what questions were asked, when was the study or poll conducted, and why the study or poll was conducted.

- The answers to these questions will help you understand the purpose of the statistical research that was conducted, and whether it would be helpful in your own research paper.

- You may find the statistics set forth in a report that describes these statistics and what they mean.

- However, just because someone else has explained the meaning of the statistics doesn't mean you should necessarily take their word for it.

- Draw on your understanding of the background of the study or poll, and look at the interpretation the author presents critically.

- Remove the statistics themselves from the text of the report, for example by copying them into a table. Then you can interpret them on your own without being distracted by the author's interpretation.

- If you create a table of your own from a statistical report, make sure you label it accurately so you can cite the source of the statistics later if you decide to include them in your research paper.

- If you're looking at raw data, you may need to actually calculate the statistics yourself. If you don't have any experience with statistics, talk to someone who does.

- Your teacher or professor may be able to help you understand how to calculate the statistics correctly.

- Even if you have access to a statistics program, there's no guarantee that the result you get actually will be accurate unless you know what information to provide the program. Remember the common phrase with computer programs: "Garbage in, garbage out."

- Don't assume you can just divide two numbers to get a percentage, for example. There are other probability elements that must be taken into account.

Writing with Statistics

- For example, the word "average" is one you often see in everyday writing. However, when you're writing about statistics, the word "average" could mean up to three different things.

- The word "average" can be used to mean the median (the middle value in the set of data), the mean (the result when you add all the values in the set and then divide by the quantity of numbers in the set), or the mode (the number or value in the set that occurs most frequently).

- Therefore, if you read "average," you need to know which of these definitions is meant.

- You also want to make sure that any two or more statistics you're comparing are using the same definition of "average." Not doing so could lead to a significant misinterpretation of your statistics and what they mean in the context of your research.

- Charts and graphs also can be useful even when you are referencing the statistics within your text. Using graphical elements can break up the text and enhance reader understanding.

- Tables, charts, and graphs can be especially beneficial if you ultimately will have to give a presentation of your research paper, either to your class or to teachers or professors.

- As difficult as statistics are to follow in print, they can be even more difficult to follow when someone is merely telling them to you.

- To test the readability of the statistics in your paper, read those paragraphs out loud to yourself. If you find yourself stumbling over them or getting confused as you read, it's likely anyone else will stumble too when reading them for the first time.

- This often has as much to do with how you describe the statistics as the specific statistics you use.

- Keep in mind that numbers themselves are neutral – it is your interpretation of those numbers that gives them meaning.

- For example, if you present the statistic that the murder rate in one neighborhood increased by 500 percent, and in the same period high school graduation rates decreased by 300 percent, these numbers are virtually meaningless without context.

- You don't know what a 500 percent increase entails unless you know what the rate was before the period measured by the statistic.

- When you say "500 percent," it sounds like a large amount, but if there was only one murder before the period measured by the statistic, then what you're actually saying is that during that period there were five murders.

- Additionally, your statistics may be more meaningful if you can compare them to similar statistics in other areas.

- Think of it in terms of a scientific experiment. If scientists are studying the effects of a particular drug to treat a disease, they also include a control group that doesn't take the drug. Comparing the test group to the control group helps show the drug's effectiveness.

- For example, you might write "According to the FBI, violent crime in McKinley County increased by 37 percent between the years 2000 and 2012."

- A textual citation provides immediate authority to the statistics you're using, allowing your readers to trust the statistics and move on to the next point.

- On the other hand, if you don't state where the statistics came from, your reader may be too busy mentally questioning the source of your statistics to fully grasp the point you're trying to make.

Expert Q&A

You might also like.

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/672/1/

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/statistics/

- ↑ https://www.nationmaster.com/country-info/stats

- ↑ https://www.usa.gov/statistics

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/672/02/

- ↑ http://libguides.lib.msu.edu/datastats

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/672/06/

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/672/04/

About this article

Did this article help you?

- About wikiHow

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Faculty of Arts & Sciences Libraries

PHYSCI 10: Quantum and Statistical, and Computational Foundations of Chemistry

How to read a scholarly article.

- Scholarly vs Popular Sources

- Peer Review

- How to get the full text

- Find Dissertations and Theses

- Data Visualization

- Managing Citations

- Writing Help

- How to Read a Scholarly Article - brief video from Western Libraries

- Infographic: How to read a scientific paper "Because scientific articles are different from other texts, like novels or newspaper stories, they should be read differently."

- How to Read and Comprehend Scientific Research Articles brief video from the University of Minnesota Libraries

- << Previous: Peer Review

- Next: Find Articles >>

- Last Updated: Oct 13, 2021 3:19 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/PS10

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

Your Account

Manage your account, subscriptions and profile.

MyKomen Health

ShareForCures

In Your Community

In Your Community

View resources and events in your local community.

Change your location:

Susan G. Komen®

One moment can change everything.

How to Read a Research Table

The tables in this section present the research findings that drive many recommendations and standards of practice related to breast cancer.

Research tables are useful for presenting data. They show a lot of information in a simple format, but they can be hard to understand if you don’t work with them every day.

Here, we describe some basic concepts that may help you read and understand research tables. The sample table below gives examples.

The numbered table items are described below. You will see many of these items in all of the tables.

Sample table – Alcohol and breast cancer risk

Selection criteria.

Studies vary in how well they help answer scientific questions. When reviewing the research on a topic, it’s important to recognize “good” studies. Good studies are well-designed.

Most scientific reviews set standards for the studies they include. These standards are called “selection criteria” and are listed for each table in this section. These selection criteria help make sure well-designed studies are included in the table.

Types of studies

The types of studies (for example, randomized controlled trial, prospective cohort, case-control) included in each table are listed in the selection criteria.

Learn about the strengths and weaknesses of different types of research studies .

Selection criteria for most tables include the minimum number of cases of breast cancer or participants for the studies in the table.

Large studies have more statistical power than small studies. This means the results from large studies are less likely to be due to chance than results from small studies.

The power of large numbers

You can see the power of large numbers if you think about flipping a coin. Say you are trying to figure out whether a coin is fixed so that it lands on “heads” more than “tails.” A fair coin would land on heads half the time. So, you want to test whether the coin lands on heads more than half of the time.

If you flip the coin twice and get 2 heads, you don’t have a lot of evidence. It wouldn’t be surprising to flip a fair coin and get 2 heads in a row. With 2 coin flips, you can’t be sure whether you have a fair coin or not. Even 3 or 4 heads in a row wouldn’t be surprising for a fair coin.

If, however, you flipped the coin 20 times and got mostly heads, you would start to think the coin might be fixed.

With an increasing number of observations, you have more evidence on which to base your conclusions. So, you have more confidence in your conclusions. It’s a similar idea in research.

Example of study size in breast cancer research

Say you’re interested in finding out whether or not alcohol use increases the risk of breast cancer.

If there are only a few cases of breast cancer among the alcohol drinkers and the non-drinkers, you won’t have much confidence drawing conclusions.

If, however, there are hundreds of breast cancer cases, it’s easier to draw firm conclusions about a link between alcohol and breast cancer. With more evidence, you have more confidence in your findings.

The importance of study design and study quality

Study design (the type of research study) and study quality are also important. For example, a small, well-designed study may be better than a large, poorly-designed study. However, when all else is equal, a larger number of people in a study means the study is better able to answer research questions.

Learn about different types of research studies .

The studies

The first column (from the left) lists either the name of the study or the name of the first author of the published article.

Below each table, there’s a reference list so you can find the original published articles.

Sometimes, a table will report the results of only one analysis. This can occur for a few reasons. Either there’s only one study that meets the selection criteria or there’s a report that combines data from many studies into one large analysis.

Study population

The second column describes the people in each study.

- For randomized controlled trials, the study population is the total number of people who were randomized at the start of the study to either the treatment (or intervention) group or the control group.

- For prospective cohort studies, the study population is the number of people at the start of the study (baseline cohort).

- For case-control studies, the study population is the number of cases and the number of controls.

In some tables, more details on the people in the study are included.

Length of follow-up

Randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies follow people forward in time to see who will have the outcome of interest (such as breast cancer).

For these studies, one column shows the length of follow-up time. This is the number or months or years people in the study were followed.

Because case-control studies don’t follow people forward in time, there are no data on follow-up time for these studies.

Tables that focus on cumulative risk may also show the length of follow-up. These tables give the length of time, or age range, used to compute cumulative risk (for example, the cumulative risk of breast cancer up to age 70).

Learn more about cumulative risk .

Other information

Some tables have columns with other information on the study population or the topic being studied. For example, the table Exercise and Breast Cancer Risk has a column with the comparisons of exercise used in the studies.

This extra information gives more details about the studies and shows how the studies are similar to (and different from) each other.

Studies on the same topic can differ in important ways. They may define “high” and “low” levels of a risk factor differently. Studies may look at outcomes among women of different ages or menopausal status.

These differences are important to keep in mind when you review the findings in a table. They may help explain differences in study findings.

Understanding the numbers

All of the information in the tables is important, but the main purpose of the tables is to present the numbers that show the risk, survival or other measures for each topic. These numbers are shown in the remaining columns of the tables.

The headings of the columns tell you what the numbers represent. For example:

- What is the outcome of interest? Is it breast cancer? Is it 5-year survival? Is it breast cancer recurrence?

- Are groups being compared to each other? If so, what groups are being compared?

Relative risks

Most often, findings are reported as relative risks. A relative risk shows how much higher, how much lower or whether there’s no difference in risk for people with a certain risk factor compared to the risk in people without the factor.

A relative risk compares 2 absolute risks.

- The numerator (the top number in a fraction) is the absolute risk among people with the risk factor.

- The denominator (the bottom number) is the absolute risk among those without the risk factor.

The absolute risk of those with the factor divided by the absolute risk of those without the factor gives the relative risk.

The confidence interval around a relative risk helps show whether or not the relative risk is statistically significant (whether or not the finding is likely due to chance).

Learn more about confidence intervals .

Example of relative risk

Say a study shows women who don’t exercise (inactive women) have a 25 percent increase in breast cancer risk compared to women who do exercise (active women).

This statistic is a relative risk (the relative risk is 1.25). It means the inactive women were 25 percent more likely to develop breast cancer than women who exercised.

Learn more about relative risk .

Confidence intervals

A 95 percent confidence interval (95% CI) around a risk measure means there’s a 95 percent chance the “true” measure falls within the interval.

Because there’s random error in studies, and study populations are only samples of much larger populations, a single study doesn’t give the “one” correct answer. There’s always a range of likely answers. A single study gives a “best estimate” along with a 95 % CI of a likely range.

Most scientific studies report risk measures, such as relative risks, odds ratios and averages, with 95% CI.

Confidence intervals and statistical significance

For relative risks and odds ratios, a 95% CI that includes the number 1.0 means there’s no link between an exposure (such as a risk factor or a treatment) and an outcome (such as breast cancer or survival).

When this happens, the results are not statistically significant. This means any link between the exposure and outcome is likely due to chance.

If a 95% CI does not include 1.0, the results are statistically significant. This means there’s likely a true link between an exposure and an outcome.

Examples of confidence intervals

A few examples from the sample table above may help explain statistical significance.

The EPIC study found a relative risk of breast cancer of 1.07, with a 95% CI of 0.96 to 1.19. In the table, you will see 1.07 (0.96-1.19).

Women in the EPIC study who drank 1-2 drinks per day had a 7 percent higher risk of breast cancer than women who did not drink alcohol. The 95% CI of 0.96 to 1.19 includes 1.0. This means these results are not statistically significant and the increased risk of breast cancer is likely due to chance.

The Million Women’s Study found a relative risk of breast cancer of 1.13 with a 95% CI of 1.10 to 1.16. This is shown as 1.13 (1.10-1.16) in the table.

Women in the Million Women’s Study who drank 1-2 drinks per day had a 13 percent higher risk of breast cancer than women who did not drink alcohol. In this case, the 95% CI of 1.10 to 1.16 does not include 1.0. So, these results are statistically significant and suggest there’s likely a true link between alcohol and breast cancer.

For any topic, it’s important to look at the findings as a whole. In the sample table above, most studies show a statistically significant increase in risk among women who drink alcohol compared to women who don’t drink alcohol. Thus, the findings as a whole suggest alcohol increases the risk of breast cancer.

Summary relative risks

Summary relative risks from meta-analyses.

A meta-analysis takes relative risks reported in different studies and “averages” them to come up with a single, summary measure. Findings from a meta-analysis can give stronger conclusions than findings from a single study.

Summary relative risks from pooled analyses

A pooled analysis uses data from multiple studies to give a summary measure. It combines the data from each person in each of the studies into one large data set and analyses the data as if it were one big study. A pooled analysis is almost always better than a meta-analysis.

In a meta-analysis, researchers combine the results from different studies. In a pooled analysis, researchers combine the individual data from the different studies. This usually gives more statistical power than a meta-analyses. More statistical power means it’s more likely the results are not simply due to chance.

Cumulative risk

Sometimes, study findings are presented as a cumulative risk (risk up to a certain age). This risk is often shown as a percentage.

A cumulative risk may show the risk of breast cancer for a certain group of people up to a certain age. Say the cumulative risk up to age 70 for women with a risk factor is 20 percent. This means by age 70, 20 percent of the women (or 1 in 5) with the risk factor will get breast cancer.

Lifetime risk is a cumulative risk. It shows the risk of getting breast cancer during your lifetime (or up to a certain age). Women in the U.S. have a 13 percent lifetime risk of getting breast cancer. This means 1 in 8 women in the U.S. will get breast cancer during their lifetime.

Learn more about lifetime risk .

Sensitivity and specificity

Some tables show study findings on the sensitivity and specificity of screening tests. These measures describe the quality of a breast cancer screening test.

- Sensitivity shows how well the screening test shows who truly has breast cancer. A sensitivity of 90 percent means 90 percent of people tested who truly have breast cancer are correctly identified as having cancer.

- Specificity shows how well the screening test shows who truly does not have breast cancer. A specificity of 90 percent means 90 percent of the people who do not have breast cancer are correctly identified as not having cancer.

The goals of any screening test are:

- To correctly identify everyone who has a certain disease (100 percent sensitivity)

- To correctly identify everyone who does not have the disease (100 percent specificity)

A perfect test would correctly identify everyone with no mistakes. There would be no:

- False negatives (when people who have the disease are missed by the test)

- False positives (when healthy people are incorrectly shown to have the disease)

No screening test has perfect (100 percent) sensitivity and perfect (100 percent) specificity. There’s always a trade-off between the two. When a test gains sensitivity, it loses some specificity.

Learn more about sensitivity and specificity .

Finding studies

You may want more detail about a study than is given in the summary table. To help you find this information, the references for all the studies in a table are listed below the table.

Each reference includes the:

- Authors of the study article

- Title of the article

- Year the article was published

- Title and specific issue of the medical journal where the article appeared

PubMed , the National Library of Medicine’s search engine, is a good source for finding summaries of science and medical journal articles (called abstracts).

For some abstracts, PubMed also has links to the full text articles. Most medical journals have websites and offer their articles either for free or for a fee.

If you live near a university with a medical school or public health school, you may be able to go to the school’s medical library to get a copy of an article. Local public libraries may not carry medical journals, but they may be able to find a copy of an article from another source.

More information on research studies

If you’re interested in learning more about health research, a basic epidemiology textbook may be a good place to start. The National Cancer Institute also has information on epidemiology studies and randomized controlled trials.

Updated 07/25/22

TOOLS & RESOURCES

In Your Own Words

How has having breast cancer changed your outlook?

Share Your Story or Read Others

How To Write a Statistical Research Paper: Tips, Topics, Outline

Working on a research paper can be a bit challenging. Some people even opt for paying online writing companies to do the job for them. While this might seem like a better solution, it can cost you a lot of money. A cheaper option is to search online for the critical parts of your essay. Your data should come from reliable sources for your research paper to be authentic. You will also need to introduce your work to your readers. It should be straightforward and relevant to the topic. With this in mind, here is a guideline to help you succeed in your research writing. But before that, let’s see what the outline should look like.

The Outline

Table of Contents

How to write a statistical analysis paper is a puzzle many people find difficult to crack. It’s not such a challenging task as you might think, especially if you learn some helpful tips to make the writing process easier. It’s just like working on any other essay. You only need to get the format and structure right and study the process. Here is what the general outline should look like:

- introduction;

- problem statement;

- objectives;

- methodology;

- data examination;

- discussion;

- conclusion and recommendations.

Let us now see some tips that can help you become a better statistical researcher.

- Top 99+ Trending Statistics Research Topics for Students

Tips for Writing Statistics Research Paper

If you are wondering how people write their papers, you are in the right place. We’ll take a look at a few pointers that can help you come up with amazing work.

Choose A Topic

Basically, this is the most important stage of your essay. Whether you want to pay for it or not, you need a simple and accessible topic to write about. Usually, the paid research papers have a well-formed and clear topic. It helps your paper to stand out. Start off by explaining to your audience what your papers are all about. Also, check whether there is enough data to support your idea. The weaker the topic is, the harder your work will be. Is the potential theme within the realm of statistics? Can the question at hand be solved with the help of the available data? These are some of the questions someone should answer first. In the end, the topic you opt for should provide sufficient space for independent information collection and analysis.

Collect Data

This stage relies heavily on the quantity of data sources and the method used to collect them. Keep in mind that you must stick to the chosen methodology throughout your essay. It is also important to explain why you opted for the data collection method used. Plus, be cautious when collecting information. One simple mistake can compromise the entire work. You can source your data from reliable sources like google, read published articles, or experiment with your own findings. However, if your instructor provides certain recommendations, follow them instead. Don’t twist the information to fit your interest to avoid losing originality. And in case no recommendations are given, ask your instructor to provide some.

Write Body Paragraphs

Use the information garnered to create the main body of your essay. After identifying an applicable area of interest, use the data to build your paragraphs. You can start off by making a rough draft of your findings and then use it as a guide for your main essay. The next step is to construe numerical figures and make conclusions. This stage requires your proficiency in interpreting statistics. Integrate your math engagement strategies to break down those figures and pinpoint only the most meaningful parts of them. Also, include some common counterpoints and support the information with specific examples.

Create Your Essay

Now that you have all the appropriate materials at hand, this section will be easy. Simply note down all the information gathered, citing your sources as well. Make sure not to copy and paste directly to avoid plagiarism. Your content should be unique and easy to read, too. We recommend proofreading and polishing your work before making it public. In addition, be on the lookout for any grammatical, spelling, or punctuation mistakes.

This section is a summary of all your findings. Explain the importance of what you are doing. You can also include suggestions for future work. Make sure to restate what you mentioned in the introduction and touch a little bit on the method used to collect and analyze your data. In short, sum up everything you’ve written in your essay.

How to Find Statistical Topics for your Paper

Statistics is a discipline that involves collecting, analyzing, organizing, presenting, and interpreting data. If you are looking for the right topic for your work, here are a few things to consider.

● Start by finding out what topics have already been worked on and pick the remaining areas.

● Consider recent developments in your field of study that may inspire a new topic.

● Think about any specific questions or problems that you have come across on your own that could be explored further.

● Ask your advisor or mentor for suggestions.

● Review conference proceedings, journal articles, and other publications.

● Try using a brainstorming technique. For instance, list out related keywords and combine them in different ways to generate new ideas.

Try out some of these tips. Be sure to find something that will work for you.

Working on a statistics paper can be quite challenging to work on. But with the right information sources, everything becomes easy. This guide will help you reveal the secret of preparing such essays. Also, don’t forget to do more reading to broaden your knowledge. You can find statistics research paper examples and refer to them for ideas. Nonetheless, if you’re still not confident enough, you can always hire a trustworthy writing company to get the job done.

Related Posts

Top Useful Applications of Data Mining in Different Fields

What Are The Beneficial Factors Of Renting 1 BHK Flats In Hyderabad?

Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

What the data says about abortion in the u.s..

Pew Research Center has conducted many surveys about abortion over the years, providing a lens into Americans’ views on whether the procedure should be legal, among a host of other questions.

In a Center survey conducted nearly a year after the Supreme Court’s June 2022 decision that ended the constitutional right to abortion , 62% of U.S. adults said the practice should be legal in all or most cases, while 36% said it should be illegal in all or most cases. Another survey conducted a few months before the decision showed that relatively few Americans take an absolutist view on the issue .

Find answers to common questions about abortion in America, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Guttmacher Institute, which have tracked these patterns for several decades:

How many abortions are there in the U.S. each year?

How has the number of abortions in the u.s. changed over time, what is the abortion rate among women in the u.s. how has it changed over time, what are the most common types of abortion, how many abortion providers are there in the u.s., and how has that number changed, what percentage of abortions are for women who live in a different state from the abortion provider, what are the demographics of women who have had abortions, when during pregnancy do most abortions occur, how often are there medical complications from abortion.

This compilation of data on abortion in the United States draws mainly from two sources: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Guttmacher Institute, both of which have regularly compiled national abortion data for approximately half a century, and which collect their data in different ways.

The CDC data that is highlighted in this post comes from the agency’s “abortion surveillance” reports, which have been published annually since 1974 (and which have included data from 1969). Its figures from 1973 through 1996 include data from all 50 states, the District of Columbia and New York City – 52 “reporting areas” in all. Since 1997, the CDC’s totals have lacked data from some states (most notably California) for the years that those states did not report data to the agency. The four reporting areas that did not submit data to the CDC in 2021 – California, Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey – accounted for approximately 25% of all legal induced abortions in the U.S. in 2020, according to Guttmacher’s data. Most states, though, do have data in the reports, and the figures for the vast majority of them came from each state’s central health agency, while for some states, the figures came from hospitals and other medical facilities.

Discussion of CDC abortion data involving women’s state of residence, marital status, race, ethnicity, age, abortion history and the number of previous live births excludes the low share of abortions where that information was not supplied. Read the methodology for the CDC’s latest abortion surveillance report , which includes data from 2021, for more details. Previous reports can be found at stacks.cdc.gov by entering “abortion surveillance” into the search box.

For the numbers of deaths caused by induced abortions in 1963 and 1965, this analysis looks at reports by the then-U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, a precursor to the Department of Health and Human Services. In computing those figures, we excluded abortions listed in the report under the categories “spontaneous or unspecified” or as “other.” (“Spontaneous abortion” is another way of referring to miscarriages.)

Guttmacher data in this post comes from national surveys of abortion providers that Guttmacher has conducted 19 times since 1973. Guttmacher compiles its figures after contacting every known provider of abortions – clinics, hospitals and physicians’ offices – in the country. It uses questionnaires and health department data, and it provides estimates for abortion providers that don’t respond to its inquiries. (In 2020, the last year for which it has released data on the number of abortions in the U.S., it used estimates for 12% of abortions.) For most of the 2000s, Guttmacher has conducted these national surveys every three years, each time getting abortion data for the prior two years. For each interim year, Guttmacher has calculated estimates based on trends from its own figures and from other data.

The latest full summary of Guttmacher data came in the institute’s report titled “Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2020.” It includes figures for 2020 and 2019 and estimates for 2018. The report includes a methods section.

In addition, this post uses data from StatPearls, an online health care resource, on complications from abortion.

An exact answer is hard to come by. The CDC and the Guttmacher Institute have each tried to measure this for around half a century, but they use different methods and publish different figures.

The last year for which the CDC reported a yearly national total for abortions is 2021. It found there were 625,978 abortions in the District of Columbia and the 46 states with available data that year, up from 597,355 in those states and D.C. in 2020. The corresponding figure for 2019 was 607,720.

The last year for which Guttmacher reported a yearly national total was 2020. It said there were 930,160 abortions that year in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, compared with 916,460 in 2019.

- How the CDC gets its data: It compiles figures that are voluntarily reported by states’ central health agencies, including separate figures for New York City and the District of Columbia. Its latest totals do not include figures from California, Maryland, New Hampshire or New Jersey, which did not report data to the CDC. ( Read the methodology from the latest CDC report .)

- How Guttmacher gets its data: It compiles its figures after contacting every known abortion provider – clinics, hospitals and physicians’ offices – in the country. It uses questionnaires and health department data, then provides estimates for abortion providers that don’t respond. Guttmacher’s figures are higher than the CDC’s in part because they include data (and in some instances, estimates) from all 50 states. ( Read the institute’s latest full report and methodology .)

While the Guttmacher Institute supports abortion rights, its empirical data on abortions in the U.S. has been widely cited by groups and publications across the political spectrum, including by a number of those that disagree with its positions .

These estimates from Guttmacher and the CDC are results of multiyear efforts to collect data on abortion across the U.S. Last year, Guttmacher also began publishing less precise estimates every few months , based on a much smaller sample of providers.

The figures reported by these organizations include only legal induced abortions conducted by clinics, hospitals or physicians’ offices, or those that make use of abortion pills dispensed from certified facilities such as clinics or physicians’ offices. They do not account for the use of abortion pills that were obtained outside of clinical settings .

(Back to top)

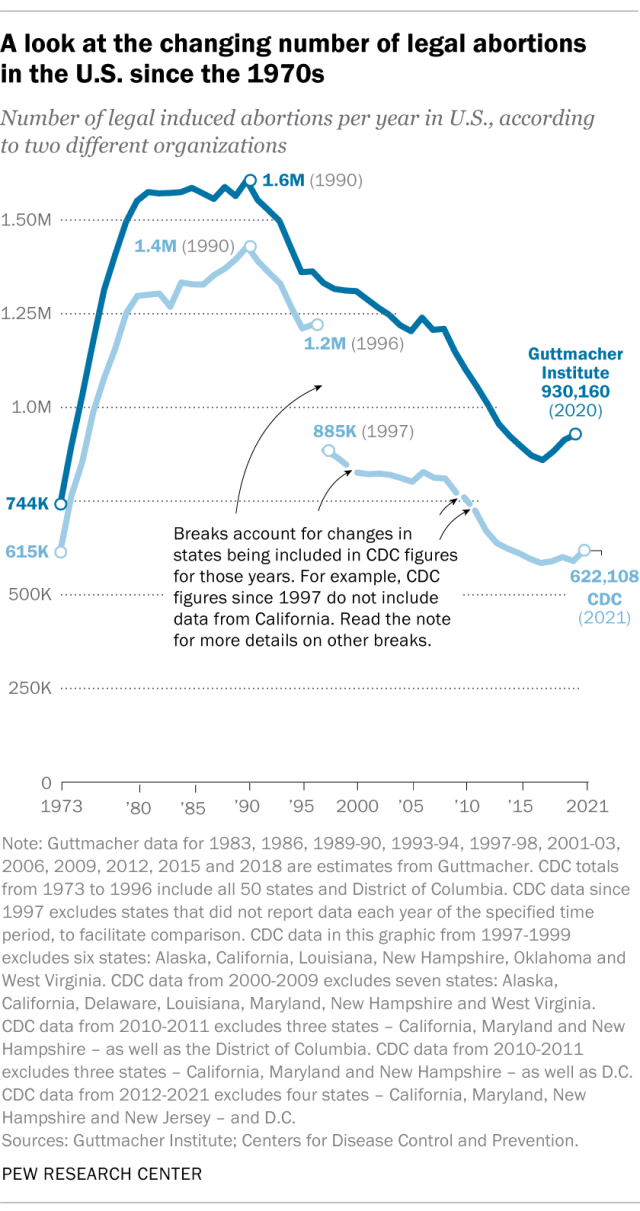

The annual number of U.S. abortions rose for years after Roe v. Wade legalized the procedure in 1973, reaching its highest levels around the late 1980s and early 1990s, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher. Since then, abortions have generally decreased at what a CDC analysis called “a slow yet steady pace.”

Guttmacher says the number of abortions occurring in the U.S. in 2020 was 40% lower than it was in 1991. According to the CDC, the number was 36% lower in 2021 than in 1991, looking just at the District of Columbia and the 46 states that reported both of those years.

(The corresponding line graph shows the long-term trend in the number of legal abortions reported by both organizations. To allow for consistent comparisons over time, the CDC figures in the chart have been adjusted to ensure that the same states are counted from one year to the next. Using that approach, the CDC figure for 2021 is 622,108 legal abortions.)

There have been occasional breaks in this long-term pattern of decline – during the middle of the first decade of the 2000s, and then again in the late 2010s. The CDC reported modest 1% and 2% increases in abortions in 2018 and 2019, and then, after a 2% decrease in 2020, a 5% increase in 2021. Guttmacher reported an 8% increase over the three-year period from 2017 to 2020.

As noted above, these figures do not include abortions that use pills obtained outside of clinical settings.

Guttmacher says that in 2020 there were 14.4 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. Its data shows that the rate of abortions among women has generally been declining in the U.S. since 1981, when it reported there were 29.3 abortions per 1,000 women in that age range.

The CDC says that in 2021, there were 11.6 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. (That figure excludes data from California, the District of Columbia, Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey.) Like Guttmacher’s data, the CDC’s figures also suggest a general decline in the abortion rate over time. In 1980, when the CDC reported on all 50 states and D.C., it said there were 25 abortions per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44.

That said, both Guttmacher and the CDC say there were slight increases in the rate of abortions during the late 2010s and early 2020s. Guttmacher says the abortion rate per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44 rose from 13.5 in 2017 to 14.4 in 2020. The CDC says it rose from 11.2 per 1,000 in 2017 to 11.4 in 2019, before falling back to 11.1 in 2020 and then rising again to 11.6 in 2021. (The CDC’s figures for those years exclude data from California, D.C., Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey.)

The CDC broadly divides abortions into two categories: surgical abortions and medication abortions, which involve pills. Since the Food and Drug Administration first approved abortion pills in 2000, their use has increased over time as a share of abortions nationally, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher.

The majority of abortions in the U.S. now involve pills, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher. The CDC says 56% of U.S. abortions in 2021 involved pills, up from 53% in 2020 and 44% in 2019. Its figures for 2021 include the District of Columbia and 44 states that provided this data; its figures for 2020 include D.C. and 44 states (though not all of the same states as in 2021), and its figures for 2019 include D.C. and 45 states.

Guttmacher, which measures this every three years, says 53% of U.S. abortions involved pills in 2020, up from 39% in 2017.

Two pills commonly used together for medication abortions are mifepristone, which, taken first, blocks hormones that support a pregnancy, and misoprostol, which then causes the uterus to empty. According to the FDA, medication abortions are safe until 10 weeks into pregnancy.

Surgical abortions conducted during the first trimester of pregnancy typically use a suction process, while the relatively few surgical abortions that occur during the second trimester of a pregnancy typically use a process called dilation and evacuation, according to the UCLA School of Medicine.

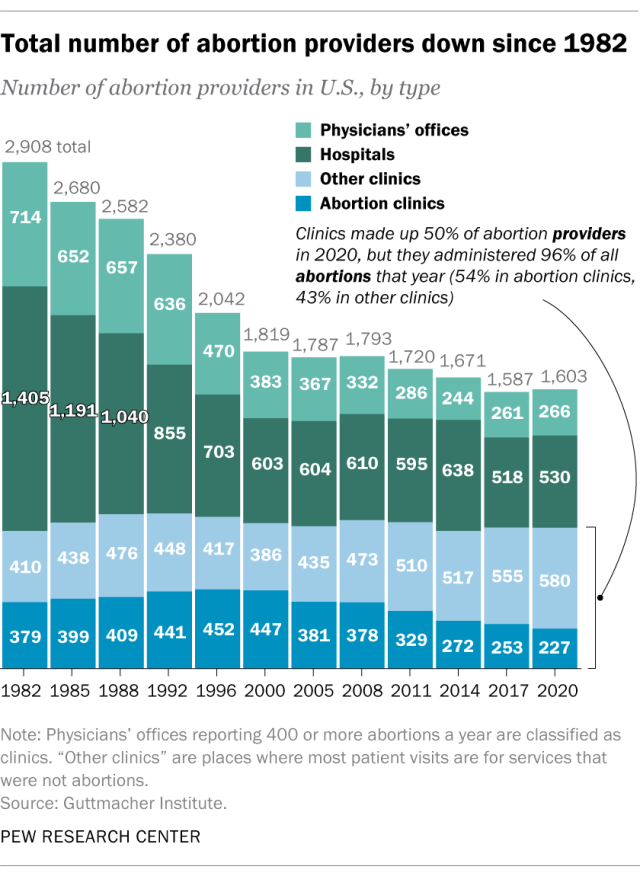

In 2020, there were 1,603 facilities in the U.S. that provided abortions, according to Guttmacher . This included 807 clinics, 530 hospitals and 266 physicians’ offices.

While clinics make up half of the facilities that provide abortions, they are the sites where the vast majority (96%) of abortions are administered, either through procedures or the distribution of pills, according to Guttmacher’s 2020 data. (This includes 54% of abortions that are administered at specialized abortion clinics and 43% at nonspecialized clinics.) Hospitals made up 33% of the facilities that provided abortions in 2020 but accounted for only 3% of abortions that year, while just 1% of abortions were conducted by physicians’ offices.

Looking just at clinics – that is, the total number of specialized abortion clinics and nonspecialized clinics in the U.S. – Guttmacher found the total virtually unchanged between 2017 (808 clinics) and 2020 (807 clinics). However, there were regional differences. In the Midwest, the number of clinics that provide abortions increased by 11% during those years, and in the West by 6%. The number of clinics decreased during those years by 9% in the Northeast and 3% in the South.

The total number of abortion providers has declined dramatically since the 1980s. In 1982, according to Guttmacher, there were 2,908 facilities providing abortions in the U.S., including 789 clinics, 1,405 hospitals and 714 physicians’ offices.

The CDC does not track the number of abortion providers.

In the District of Columbia and the 46 states that provided abortion and residency information to the CDC in 2021, 10.9% of all abortions were performed on women known to live outside the state where the abortion occurred – slightly higher than the percentage in 2020 (9.7%). That year, D.C. and 46 states (though not the same ones as in 2021) reported abortion and residency data. (The total number of abortions used in these calculations included figures for women with both known and unknown residential status.)

The share of reported abortions performed on women outside their state of residence was much higher before the 1973 Roe decision that stopped states from banning abortion. In 1972, 41% of all abortions in D.C. and the 20 states that provided this information to the CDC that year were performed on women outside their state of residence. In 1973, the corresponding figure was 21% in the District of Columbia and the 41 states that provided this information, and in 1974 it was 11% in D.C. and the 43 states that provided data.

In the District of Columbia and the 46 states that reported age data to the CDC in 2021, the majority of women who had abortions (57%) were in their 20s, while about three-in-ten (31%) were in their 30s. Teens ages 13 to 19 accounted for 8% of those who had abortions, while women ages 40 to 44 accounted for about 4%.

The vast majority of women who had abortions in 2021 were unmarried (87%), while married women accounted for 13%, according to the CDC , which had data on this from 37 states.

In the District of Columbia, New York City (but not the rest of New York) and the 31 states that reported racial and ethnic data on abortion to the CDC , 42% of all women who had abortions in 2021 were non-Hispanic Black, while 30% were non-Hispanic White, 22% were Hispanic and 6% were of other races.

Looking at abortion rates among those ages 15 to 44, there were 28.6 abortions per 1,000 non-Hispanic Black women in 2021; 12.3 abortions per 1,000 Hispanic women; 6.4 abortions per 1,000 non-Hispanic White women; and 9.2 abortions per 1,000 women of other races, the CDC reported from those same 31 states, D.C. and New York City.

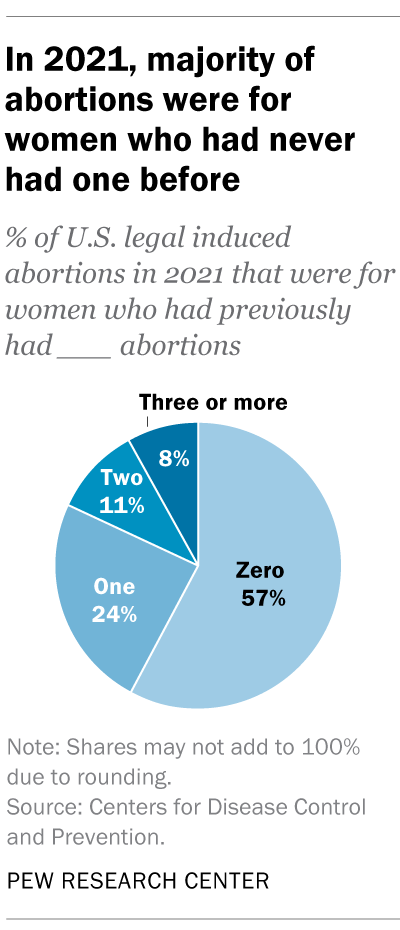

For 57% of U.S. women who had induced abortions in 2021, it was the first time they had ever had one, according to the CDC. For nearly a quarter (24%), it was their second abortion. For 11% of women who had an abortion that year, it was their third, and for 8% it was their fourth or more. These CDC figures include data from 41 states and New York City, but not the rest of New York.

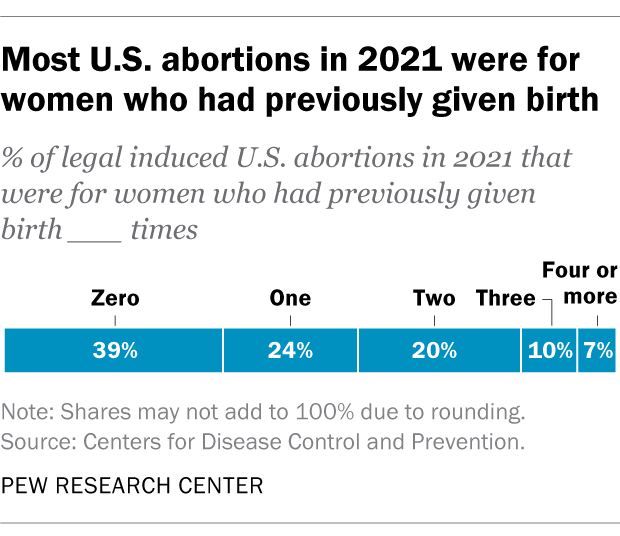

Nearly four-in-ten women who had abortions in 2021 (39%) had no previous live births at the time they had an abortion, according to the CDC . Almost a quarter (24%) of women who had abortions in 2021 had one previous live birth, 20% had two previous live births, 10% had three, and 7% had four or more previous live births. These CDC figures include data from 41 states and New York City, but not the rest of New York.

The vast majority of abortions occur during the first trimester of a pregnancy. In 2021, 93% of abortions occurred during the first trimester – that is, at or before 13 weeks of gestation, according to the CDC . An additional 6% occurred between 14 and 20 weeks of pregnancy, and about 1% were performed at 21 weeks or more of gestation. These CDC figures include data from 40 states and New York City, but not the rest of New York.

About 2% of all abortions in the U.S. involve some type of complication for the woman , according to an article in StatPearls, an online health care resource. “Most complications are considered minor such as pain, bleeding, infection and post-anesthesia complications,” according to the article.

The CDC calculates case-fatality rates for women from induced abortions – that is, how many women die from abortion-related complications, for every 100,000 legal abortions that occur in the U.S . The rate was lowest during the most recent period examined by the agency (2013 to 2020), when there were 0.45 deaths to women per 100,000 legal induced abortions. The case-fatality rate reported by the CDC was highest during the first period examined by the agency (1973 to 1977), when it was 2.09 deaths to women per 100,000 legal induced abortions. During the five-year periods in between, the figure ranged from 0.52 (from 1993 to 1997) to 0.78 (from 1978 to 1982).

The CDC calculates death rates by five-year and seven-year periods because of year-to-year fluctuation in the numbers and due to the relatively low number of women who die from legal induced abortions.

In 2020, the last year for which the CDC has information , six women in the U.S. died due to complications from induced abortions. Four women died in this way in 2019, two in 2018, and three in 2017. (These deaths all followed legal abortions.) Since 1990, the annual number of deaths among women due to legal induced abortion has ranged from two to 12.

The annual number of reported deaths from induced abortions (legal and illegal) tended to be higher in the 1980s, when it ranged from nine to 16, and from 1972 to 1979, when it ranged from 13 to 63. One driver of the decline was the drop in deaths from illegal abortions. There were 39 deaths from illegal abortions in 1972, the last full year before Roe v. Wade. The total fell to 19 in 1973 and to single digits or zero every year after that. (The number of deaths from legal abortions has also declined since then, though with some slight variation over time.)

The number of deaths from induced abortions was considerably higher in the 1960s than afterward. For instance, there were 119 deaths from induced abortions in 1963 and 99 in 1965 , according to reports by the then-U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, a precursor to the Department of Health and Human Services. The CDC is a division of Health and Human Services.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published May 27, 2022, and first updated June 24, 2022.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Key facts about the abortion debate in America

Public opinion on abortion, three-in-ten or more democrats and republicans don’t agree with their party on abortion, partisanship a bigger factor than geography in views of abortion access locally, do state laws on abortion reflect public opinion, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Research: How Different Fields Are Using GenAI to Redefine Roles

- Maryam Alavi

Examples from customer support, management consulting, professional writing, legal analysis, and software and technology.

The interactive, conversational, analytical, and generative features of GenAI offer support for creativity, problem-solving, and processing and digestion of large bodies of information. Therefore, these features can act as cognitive resources for knowledge workers. Moreover, the capabilities of GenAI can mitigate various hindrances to effective performance that knowledge workers may encounter in their jobs, including time pressure, gaps in knowledge and skills, and negative feelings (such as boredom stemming from repetitive tasks or frustration arising from interactions with dissatisfied customers). Empirical research and field observations have already begun to reveal the value of GenAI capabilities and their potential for job crafting.

There is an expectation that implementing new and emerging Generative AI (GenAI) tools enhances the effectiveness and competitiveness of organizations. This belief is evidenced by current and planned investments in GenAI tools, especially by firms in knowledge-intensive industries such as finance, healthcare, and entertainment, among others. According to forecasts, enterprise spending on GenAI will increase by two-fold in 2024 and grow to $151.1 billion by 2027 .

- Maryam Alavi is the Elizabeth D. & Thomas M. Holder Chair & Professor of IT Management, Scheller College of Business, Georgia Institute of Technology .

Partner Center

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

What the Data Says About Pandemic School Closures, Four Years Later