Argumentative Essay Examples to Inspire You (+ Free Formula)

.webp)

Table of contents

Meredith Sell

Have you ever been asked to explain your opinion on a controversial issue?

- Maybe your family got into a discussion about chemical pesticides

- Someone at work argues against investing resources into your project

- Your partner thinks intermittent fasting is the best way to lose weight and you disagree

Proving your point in an argumentative essay can be challenging, unless you are using a proven formula.

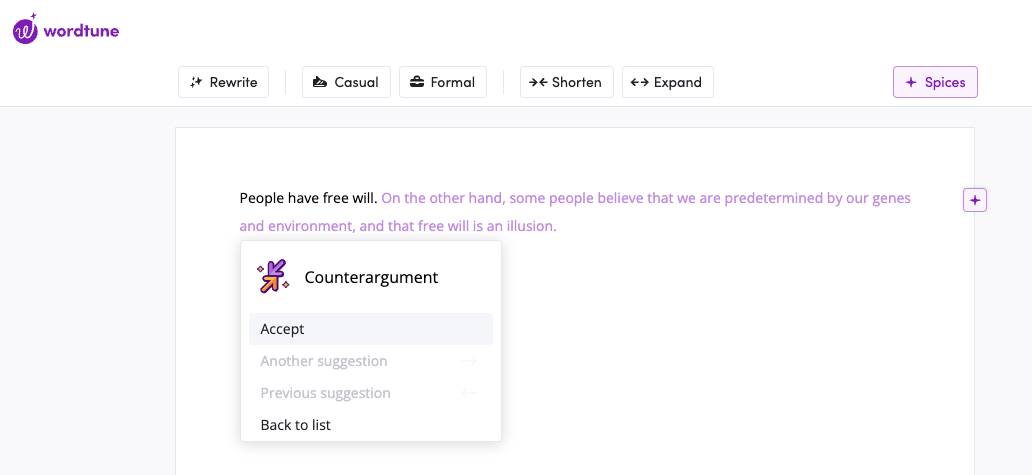

Argumentative essay formula & example

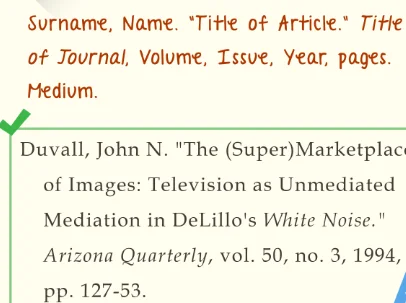

In the image below, you can see a recommended structure for argumentative essays. It starts with the topic sentence, which establishes the main idea of the essay. Next, this hypothesis is developed in the development stage. Then, the rebuttal, or the refutal of the main counter argument or arguments. Then, again, development of the rebuttal. This is followed by an example, and ends with a summary. This is a very basic structure, but it gives you a bird-eye-view of how a proper argumentative essay can be built.

Writing an argumentative essay (for a class, a news outlet, or just for fun) can help you improve your understanding of an issue and sharpen your thinking on the matter. Using researched facts and data, you can explain why you or others think the way you do, even while other reasonable people disagree.

Free AI argumentative essay generator > Free AI argumentative essay generator >

What Is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is an explanatory essay that takes a side.

Instead of appealing to emotion and personal experience to change the reader’s mind, an argumentative essay uses logic and well-researched factual information to explain why the thesis in question is the most reasonable opinion on the matter.

Over several paragraphs or pages, the author systematically walks through:

- The opposition (and supporting evidence)

- The chosen thesis (and its supporting evidence)

At the end, the author leaves the decision up to the reader, trusting that the case they’ve made will do the work of changing the reader’s mind. Even if the reader’s opinion doesn’t change, they come away from the essay with a greater understanding of the perspective presented — and perhaps a better understanding of their original opinion.

All of that might make it seem like writing an argumentative essay is way harder than an emotionally-driven persuasive essay — but if you’re like me and much more comfortable spouting facts and figures than making impassioned pleas, you may find that an argumentative essay is easier to write.

Plus, the process of researching an argumentative essay means you can check your assumptions and develop an opinion that’s more based in reality than what you originally thought. I know for sure that my opinions need to be fact checked — don’t yours?

So how exactly do we write the argumentative essay?

How do you start an argumentative essay

First, gain a clear understanding of what exactly an argumentative essay is. To formulate a proper topic sentence, you have to be clear on your topic, and to explore it through research.

Students have difficulty starting an essay because the whole task seems intimidating, and they are afraid of spending too much time on the topic sentence. Experienced writers, however, know that there is no set time to spend on figuring out your topic. It's a real exploration that is based to a large extent on intuition.

6 Steps to Write an Argumentative Essay (Persuasion Formula)

Use this checklist to tackle your essay one step at a time:

1. Research an issue with an arguable question

To start, you need to identify an issue that well-informed people have varying opinions on. Here, it’s helpful to think of one core topic and how it intersects with another (or several other) issues. That intersection is where hot takes and reasonable (or unreasonable) opinions abound.

I find it helpful to stage the issue as a question.

For example:

Is it better to legislate the minimum size of chicken enclosures or to outlaw the sale of eggs from chickens who don’t have enough space?

Should snow removal policies focus more on effectively keeping roads clear for traffic or the environmental impacts of snow removal methods?

Once you have your arguable question ready, start researching the basic facts and specific opinions and arguments on the issue. Do your best to stay focused on gathering information that is directly relevant to your topic. Depending on what your essay is for, you may reference academic studies, government reports, or newspaper articles.

Research your opposition and the facts that support their viewpoint as much as you research your own position . You’ll need to address your opposition in your essay, so you’ll want to know their argument from the inside out.

2. Choose a side based on your research

You likely started with an inclination toward one side or the other, but your research should ultimately shape your perspective. So once you’ve completed the research, nail down your opinion and start articulating the what and why of your take.

What: I think it’s better to outlaw selling eggs from chickens whose enclosures are too small.

Why: Because if you regulate the enclosure size directly, egg producers outside of the government’s jurisdiction could ship eggs into your territory and put nearby egg producers out of business by offering better prices because they don’t have the added cost of larger enclosures.

This is an early form of your thesis and the basic logic of your argument. You’ll want to iterate on this a few times and develop a one-sentence statement that sums up the thesis of your essay.

Thesis: Outlawing the sale of eggs from chickens with cramped living spaces is better for business than regulating the size of chicken enclosures.

Now that you’ve articulated your thesis , spell out the counterargument(s) as well. Putting your opposition’s take into words will help you throughout the rest of the essay-writing process. (You can start by choosing the counter argument option with Wordtune Spices .)

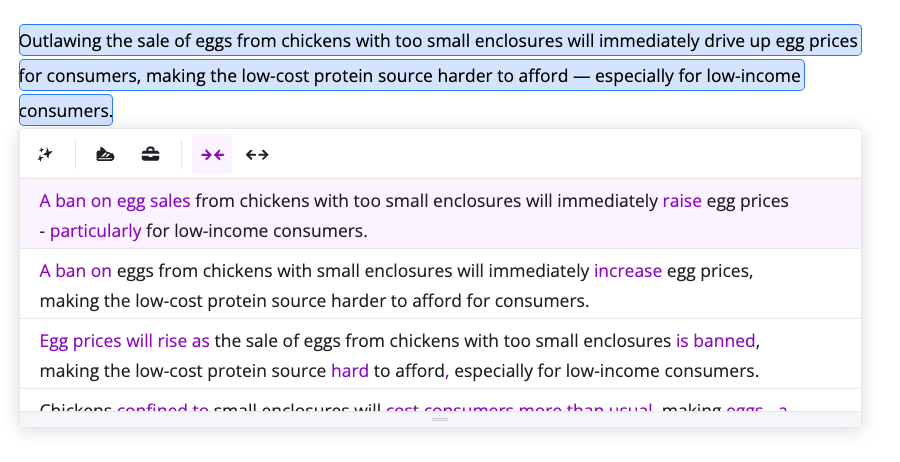

Counterargument: Outlawing the sale of eggs from chickens with too small enclosures will immediately drive up egg prices for consumers, making the low-cost protein source harder to afford — especially for low-income consumers.

There may be one main counterargument to articulate, or several. Write them all out and start thinking about how you’ll use evidence to address each of them or show why your argument is still the best option.

3. Organize the evidence — for your side and the opposition

You did all of that research for a reason. Now’s the time to use it.

Hopefully, you kept detailed notes in a document, complete with links and titles of all your source material. Go through your research document and copy the evidence for your argument and your opposition’s into another document.

List the main points of your argument. Then, below each point, paste the evidence that backs them up.

If you’re writing about chicken enclosures, maybe you found evidence that shows the spread of disease among birds kept in close quarters is worse than among birds who have more space. Or maybe you found information that says eggs from free-range chickens are more flavorful or nutritious. Put that information next to the appropriate part of your argument.

Repeat the process with your opposition’s argument: What information did you find that supports your opposition? Paste it beside your opposition’s argument.

You could also put information here that refutes your opposition, but organize it in a way that clearly tells you — at a glance — that the information disproves their point.

Counterargument: Outlawing the sale of eggs from chickens with too small enclosures will immediately drive up egg prices for consumers.

BUT: Sicknesses like avian flu spread more easily through small enclosures and could cause a shortage that would drive up egg prices naturally, so ensuring larger enclosures is still a better policy for consumers over the long term.

As you organize your research and see the evidence all together, start thinking through the best way to order your points.

Will it be better to present your argument all at once or to break it up with opposition claims you can quickly refute? Would some points set up other points well? Does a more complicated point require that the reader understands a simpler point first?

Play around and rearrange your notes to see how your essay might flow one way or another.

4. Freewrite or outline to think through your argument

Is your brain buzzing yet? At this point in the process, it can be helpful to take out a notebook or open a fresh document and dump whatever you’re thinking on the page.

Where should your essay start? What ground-level information do you need to provide your readers before you can dive into the issue?

Use your organized evidence document from step 3 to think through your argument from beginning to end, and determine the structure of your essay.

There are three typical structures for argumentative essays:

- Make your argument and tackle opposition claims one by one, as they come up in relation to the points of your argument - In this approach, the whole essay — from beginning to end — focuses on your argument, but as you make each point, you address the relevant opposition claims individually. This approach works well if your opposition’s views can be quickly explained and refuted and if they directly relate to specific points in your argument.

- Make the bulk of your argument, and then address the opposition all at once in a paragraph (or a few) - This approach puts the opposition in its own section, separate from your main argument. After you’ve made your case, with ample evidence to convince your readers, you write about the opposition, explaining their viewpoint and supporting evidence — and showing readers why the opposition’s argument is unconvincing. Once you’ve addressed the opposition, you write a conclusion that sums up why your argument is the better one.

- Open your essay by talking about the opposition and where it falls short. Build your entire argument to show how it is superior to that opposition - With this structure, you’re showing your readers “a better way” to address the issue. After opening your piece by showing how your opposition’s approaches fail, you launch into your argument, providing readers with ample evidence that backs you up.

As you think through your argument and examine your evidence document, consider which structure will serve your argument best. Sketch out an outline to give yourself a map to follow in the writing process. You could also rearrange your evidence document again to match your outline, so it will be easy to find what you need when you start writing.

5. Write your first draft

You have an outline and an organized document with all your points and evidence lined up and ready. Now you just have to write your essay.

In your first draft, focus on getting your ideas on the page. Your wording may not be perfect (whose is?), but you know what you’re trying to say — so even if you’re overly wordy and taking too much space to say what you need to say, put those words on the page.

Follow your outline, and draw from that evidence document to flesh out each point of your argument. Explain what the evidence means for your argument and your opposition. Connect the dots for your readers so they can follow you, point by point, and understand what you’re trying to say.

As you write, be sure to include:

1. Any background information your reader needs in order to understand the issue in question.

2. Evidence for both your argument and the counterargument(s). This shows that you’ve done your homework and builds trust with your reader, while also setting you up to make a more convincing argument. (If you find gaps in your research while you’re writing, Wordtune Spices can source statistics or historical facts on the fly!)

Get Wordtune for free > Get Wordtune for free >

3. A conclusion that sums up your overall argument and evidence — and leaves the reader with an understanding of the issue and its significance. This sort of conclusion brings your essay to a strong ending that doesn’t waste readers’ time, but actually adds value to your case.

6. Revise (with Wordtune)

The hard work is done: you have a first draft. Now, let’s fine tune your writing.

I like to step away from what I’ve written for a day (or at least a night of sleep) before attempting to revise. It helps me approach clunky phrases and rough transitions with fresh eyes. If you don’t have that luxury, just get away from your computer for a few minutes — use the bathroom, do some jumping jacks, eat an apple — and then come back and read through your piece.

As you revise, make sure you …

- Get the facts right. An argument with false evidence falls apart pretty quickly, so check your facts to make yours rock solid.

- Don’t misrepresent the opposition or their evidence. If someone who holds the opposing view reads your essay, they should affirm how you explain their side — even if they disagree with your rebuttal.

- Present a case that builds over the course of your essay, makes sense, and ends on a strong note. One point should naturally lead to the next. Your readers shouldn’t feel like you’re constantly changing subjects. You’re making a variety of points, but your argument should feel like a cohesive whole.

- Paraphrase sources and cite them appropriately. Did you skip citations when writing your first draft? No worries — you can add them now. And check that you don’t overly rely on quotations. (Need help paraphrasing? Wordtune can help. Simply highlight the sentence or phrase you want to adjust and sort through Wordtune’s suggestions.)

- Tighten up overly wordy explanations and sharpen any convoluted ideas. Wordtune makes a great sidekick for this too 😉

Words to start an argumentative essay

The best way to introduce a convincing argument is to provide a strong thesis statement . These are the words I usually use to start an argumentative essay:

- It is indisputable that the world today is facing a multitude of issues

- With the rise of ____, the potential to make a positive difference has never been more accessible

- It is essential that we take action now and tackle these issues head-on

- it is critical to understand the underlying causes of the problems standing before us

- Opponents of this idea claim

- Those who are against these ideas may say

- Some people may disagree with this idea

- Some people may say that ____, however

When refuting an opposing concept, use:

- These researchers have a point in thinking

- To a certain extent they are right

- After seeing this evidence, there is no way one can agree with this idea

- This argument is irrelevant to the topic

Are you convinced by your own argument yet? Ready to brave the next get-together where everyone’s talking like they know something about intermittent fasting , chicken enclosures , or snow removal policies?

Now if someone asks you to explain your evidence-based but controversial opinion, you can hand them your essay and ask them to report back after they’ve read it.

Share This Article:

Preparing for Graduate School: 8 Tips to Know

How to Master Concise Writing: 9 Tips to Write Clear and Crisp Content

Title Case vs. Sentence Case: How to Capitalize Your Titles

Looking for fresh content, thank you your submission has been received.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Webinar Transcripts: What About Me? Using Personal Experience in Academic Writing

What about me using personal experience in academic writing.

Presented October 31, 2018

View the webinar recording

Last updated 12/11/2018

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Housekeeping

- Will be available online within 24 hours.

- Polls, files, and links are interactive.

- Now: Use the Q&A box.

- Later: Send to [email protected] or visit our Live Chat Hours .

- Ask in the Q&A box.

- Choose “Help” in the upper right-hand corner of the webinar room

Audio: All right. Well, hello, everyone and thank you so much for joining us today. My name is Beth Nastachowski and I am the Manager of Multimedia Writing instruction here at the Writing Center and I'm just getting us started here with a couple of quick housekeeping notes before I hand this session over to our presenter today, Claire

A couple of things to keep in mind, the first is I have started the recording for the webinar. I'll be posting the regarding in the webinar archive and you can access that later if you have to leave for any reason during the session or if you would like to come back and review the session or access the slides, you can do that from the recording.

I also like to note here that we record all of the webinars in the Writing Center, so if you ever see a webinar being presented live and you can't attend or if you're looking for help on a particular writing topic, we have those recordings available for you 24/7 so you can just take a look at the archive in the categories there to find a recording that would be useful for you

We also hope that you'll interact with us throughout the session, so I know Claire has lots of polls and the chats she'll be using throughout the session, so make sure to interact with her and your fellow students there

But also note that the links throughout the slides that Claire has are also interactive, so you can click on the links and it will open up in a new tab on your browser, and can you also download the slides that she has here in the Files Pod that’s at the bottom right‑hand corner and can you download those slides and they'll save to your computer as well

Finally, we also have a Q&A Box on the right‑hand side of the screen so I'll monitor that box throughout the session and would be happy to answer any questions or respond to any comments that you have, so do let me know as soon as you have a question or comment, I'm happy to hear from you and I know Claire will be stopping for questions and comments to address those aloud throughout certain points of the presentation as well

However, at the very end of the session if we get to a point where we need to close out the session because we're out of time and you still have questions, please feel free to email us or visit the Live Chat Hours and we're happy to respond to you there and I'll display this information at the end of the session as well

Alright. Actually, this is our final point here. If you have any questions or have any technical issues, feel free to let me know in the Q&A Box, I have a couple of tips and tricks I can give you, but the Help Button at the top right‑hand corner is really the place to go if you have any significant issues.

Visual: Slide changes to the title of the webinar, “ What About Me? Using Personal Experience in Academic Writing ” and the speakers name and information: Claire Helakoski, Writing Instructor, Walden University Writing Center.

Audio: Alright, and so with that, Claire, I will hand it over to you.

Claire: Thanks so much, Beth. Hi, everyone, I'm Claire Helakoski a writing instructor here at the Walden Writing Center and I’m coming in from Grand Rapids, Michigan today to present What About Me? Using Personal Experience in Academic Writing today, and also Happy Halloween to those of you that celebrate it.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Learning Objectives

After this session, you will be able to:

- Identify the benefits and drawbacks of using personal experience in writing

- Determine the situations when using personal experience is appropriate

- Integrate personal experience effectively

- Access additional resources

Audio: All right. So first I want to go over our learning objectives today which are that after the session you'll be able to identify the benefits and drawbacks of using personal experience in your academic writing, determine the situations where using personal experience is appropriate, integrate personal experience effectively, and access additional resources.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Caveat

We are specifically talking about

personal experience in coursework ,

meaning discussion posts or weekly

assignments .

Doctoral studies are a whole other thing!

Audio: All right, and I do want to start with a caveat that I'm specifically talking about personal experience in coursework, so discussion posts, or weekly assignments. Doctoral studies are a very different things and if you are beyond your coursework and just working on your doctoral study, this presentation may not be as beneficial to you at your current stage since it does get a little more specific and the requirements are a little bit different in those aspects of your writing.

So today we're going to really focus on that coursework discussion post, weekly paper assignments.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Walden Students

- Are at an advantage!

- In previous education institutions

- In careers in their chosen field of study

- In military , family , or volunteer situations

Audio: All right. So Walden students are at an advantage for talking about personal experience because most of you are already working in your fields or have previous education and careers in your field of study, even if you're not working in that now, you've had some sort of career most likely, and I'm just speaking broadly and statistically here, but also through military family or volunteer situations, our students from my experience, tend to be very passionate and knowledgeable about their topics and that means you're at an advantage to have all of these great personal experiences to inform that passion and your coursework as it applies to your current job, future job, or past work that you've done.

Where does that experience go?

What does it count for?

Audio: So, we might wonder where does that experience go, right, because we're often kind of told to pull back on the personal experience in our coursework. So where does it go? Where does it end up sort of counting for? Sorry. I thought there was a pop‑up there.

That experience doesn't go anywhere in a sense that it's there, it is valuable, it is important, it has informed your decision to pursue your degree and there are many assignments that I have personally seen in the Writing Center that will let you kind of tap into that and express it in your coursework. It doesn't count for anything as far as, you know, a grade or something like that, but it's beneficial because it gives you that sort of starting point, that jumping off place to begin your work, right.

A lot of times even if you're starting an assignment that's not really meant to explore personal experience, you might think of a personal experience that you've had had and decide to pursue that topic, so it counts in a sense that you're mentally kind of already engaged with your subject, you’re invested in it, and that gives you a starting point for any type of writing you're going to do for your coursework.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Poll: How convinced are you?

Paragraph A

By and large, substance abuse in the United States begins during adolescence. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2013) stated that on an average day 881,684 adolescents smoke cigarettes, 646,707 smoke marijuana, and 457,672 drink alcohol. Adult addicts typically report beginning substance use in adolescence. In fact, one in four Americans who started using addictive substances in their teens are addicted now, compared to one in 25 who began using after the age of 21 (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 2011). When teens engage in substance use, their behavior impacts their adult lives.

Paragraph B

By and large, substance abuse in the United States begins during adolescence. As a school paraprofessional, I know this is a problem. I see teenagers every day in the high school library who are drunk or high. Just this past year, five separate students got into serious car accidents (with injuries) due to substance use. We actually have to employ drug-sniffing dogs in the school as well. These teens do not get the help they need, and so addiction becomes something they struggle with as adults as well.

Audio: So, we're going to start with a little poll here. We have Paragraph A and Paragraph B, so I'd like you to read them both and note which option you're most convinced by, and I'm going to not read these aloud because I think it would take longer than you guys reading them through, but I will give you a couple minutes to read them through and consider which of them you find most convincing and then let us know in the poll.

[silence as students respond]

I see the answers still trickling in here. I'm going to give you another minute to go ahead and respond if you have not and then we'll talk over our responses.

All right. It looks like the responses have kind of stopped trickling in so I'm going to go ahead and talk about each of these options. So, a lot of you, most of you, chose Paragraph A and that is probably because we have a lot of great statistics in Paragraph A, right. We're focusing on this kind of overall issue, we have proof that it is an issue, really specific proof, right. We're talking about numbers and statistics, and then we kind of explain what all of that means at the end there. Whereas in Paragraph B, we have kind of the same topic, right. So, we're still talking about substance use in teenagers, but this one is talking about what this writer sees in their work every day. They see these things happening, and they do have some specifics like the five separate students and what's going on in their school, and they have a kind of the same takeaway or opinion, which is that addiction is an issue and, you know, something kind of needs to be done.

So, they really are about the same topic, but Paragraph A is likely a little more convincing to the wider majority of people because it's more neutral, it has facts and statistics, you know, from all over really because it's from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Organization and so it's a big study by an established organization. And in Paragraph B while these personal experiences are great and they definitely do speak to an issue at this person's school, so if that was the assignment, then this would probably be appropriate, but if we're talking about this as a whole issue for the country or like a larger health issue, then talking about it more globally with more global statistics is going to be effective there and a little bit more convincing for an outside reader who isn't a member of this Paragraph B person's school.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Academic Writing

Readers expect

- to see research-based evidence* supporting statements even if the writer has expertise in the area

- to be persuaded through logic and reasoning

*information from course readings, books, scholarly journals, trusted websites

The need for research doesn’t mean your own knowledge is unimportant or wrong

Audio: All right. So as I kind of went over, in academic writing, readers expect to see that research‑based evidence which supports statements even if the writer has expertise in the area, so because none of us are doctors in our field yet, we aren't considered experts in our area, even though we most likely have experiences that inform us on our topic and we might have really great things to say about it, but we're not considered experts yet. And in academic writing, even the experts are still going to find that research‑based evidence to help support what they're saying. So that's just a general expectation of academic writing, and it's one of the things that separates it from other types of writing that you may have done in the past or that you may see in other fields.

Readers also expect to be persuaded through logic and reasoning rather than sort of emotional appeals or those other, you know, tools that people will use in online articles or, you know, commercials and things like that that are really overly persuasive and personal and have lots of emotion. That's not quite the right tone for that academic writing, that scholarly writing. It's not a wrong technique, but it should be saved for different arenas, different places where you're going to write. In academic writing, you want to be logical, objective, fact based, and by evidence, I mean information from your course readings, from books, scholarly journals, trusted website, so research you're doing that's been done by other people in your field and is supported and reviewed.

All right. As I've kind of gone over as well, the need for research doesn't mean your own knowledge is unimportant or wrong. It just means that you need to be a little bit careful about when and where you use that personal knowledge in your course writing because a lot of times it won't meet reader expectation, so while it can inform what you're going to write about, you'll want to use that information to fuel your research, for example.

And as we'll go over in a little bit, there are assignments that specifically ask for your own experiences, opinions, and ideas and so you can look out for those as well.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: When is personal experience okay?

- In the research process

- Thinking ● Researching ● Thinking ● Researching ● Writing

Audio: All right, so as I've sort of gone over, you might be wondering when is personal experience okay? As I mentioned in the research process, we're kind of getting you started and personal experience is a great tool, a really beneficial tool to give you a jumping off point. Like in our paragraph example, this writing has seen these issues with teenage addiction in their school so they can say, I know this is an issue and I don't think it's just an issue in my school so what I want to do is think about that issue, research that issue, and then end up writing about that issue.

And your research and thinking and writing process may go back and forth, and it probably should, right. You think of an idea, do a little research to see what's out there, think about it again, do I have enough points, do I maybe need more, is it maybe going in a different direction than I thought? Maybe do a little more research, and then start your writing. And informing that with your personal experience to help get you started for something that you observe or something that you already know to be true can be really beneficial as a jumping off point for your research.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Type of Assignments

- Assignment instructions might use the term “you” as in “What do you think will be most useful to you…”

- Assignment instructions might say, “Demonstrate your learning…” or “Refer to specific experiences in your workplace…”

- Assignment instructions might say, “Select a topic based on something you have seen, heard, or experienced…”

- Assignment instructions might say, “Describe your educational and professional background…”

Audio: So in your assignments, you may have some assignments, as I mentioned, that are going to ask for you to talk about personal experience and that is a great, great use of personal experience and a place where personal experience is not only okay but it's asked for and it's expected, and one of the key words you can look for in your assignment prompt is you, so look out for assignment prompts that use the word "you." What would you do? What do you think? What experience do you have in this field? And what would you do in this situation? Lots of "you" there but, of course, you're going to use "I," you're going to use your personal experience in those situations.

So, here’s a few that come up. An example in a reflection paper or a post, what do you think will be most useful to you? Right, reflection means you're going to talk about your experience, it's kind of inherent to reflecting on your own writing and ideas.

In a prior learning narrative, the assignment instructions might say something like, demonstrate your learning, refer to experiences in your workplace. I've seen a lot like that so obviously those are really good places to bring out that personal experience.

The assignment instructions might say something like, select a topic based on something you have seen, heard, or experienced. Or I've seen papers that deal with, you know, for example, different leadership styles or something like that and it will ask if you've had any experience with a prior manager that exhibited one of these leadership styles. Those are great places to use that personal experience. And in your professional development plan, if you write one of those, you'll definitely write about personal experience because the assignment instructions will say something like, describe your educational and professional background. So those are all wonderful places to use that personal experience and where you're being asked to use that personal experience.

So, don't feel like we're saying never, ever, ever use personal experience. You're going to have to use your judgment, and that's kind of what this webinar is to help you do, right. So, in your research process, personal experience can be helpful. In assignments that are using "you" and not just this week "you've read," but like asking questions of what do you think, what would you do in your workplace? Those are great questions where you could use some of the experience that you may have.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: To Illustrate a Theory

According to the theory of caring, nurses should be sensitive facilitators of a healing environment (Watson, 1979). I demonstrate this when I talk to patients in a calm voice, listen attentively to their needs, and limit the amount of visitors and noise.

Systems theory looks at a system holistically, with the parts working together (Janson, 2015). An example of this interdependence in my organization is…

Audio: And Sometimes talking about illustrating a theory could be a good place to introduce personal experience as well. Here is an example. According to the theory of caring, nurses should be sensitive facilitators of a healing environment. I demonstrate this when I talk to patients in a calm voice, listen attentively to their needs, and limit the amount of visitors and noise.

So, this assignment probably has something to do with talking about nursing theories and how you do or do not implement them in your nursing practice, right. So, they probably used "you" in the assignment somewhere, but it's not just all personal reflection. It's talking about the reading, talking about how you use these tools, so that's a great place to use that personal experience in a nice specific concrete way.

Here is another example. Systems theory looks at a system holistically with the parts working together and an example of this interdependence in my organization is, and again here we've probably been asked to write about your organization or a past experience in your workplace in the assignment prompt, but when you're combining that with research, demonstrating that theory with personal experience can be really beneficial and helpful for readers because you have that nice evidence and then a concrete example.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Benefits of Personal Experience

- better understanding

- stronger connection with the material

- perhaps more confidence

- more interesting

- helpful to see an example from an insider perspective

Audio: All right, so the benefits of personal experience for you are that better understanding of your topic, a stronger connection with the material. I mentioned that passion before. And maybe more confidence writing about it because you know for sure that this is an issue, this is something that's going on, this is something you've noticed, you've experienced, and so you can go into it with confidence into your research that there is going to be something out there that supports what you've seen and what you've experienced or what practices you have in your workplace.

For your reader, adding that personal experience where appropriate can be more interesting and helpful to see those examples from an insider perspective. As you all know, I'm sure, excuse me. ‑‑ as you all know I'm sure, reading just about theories can be a little dry, so having those concrete examples of what that looks like in practice can be much more engaging for readers.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Questions

Audio: All right. Let's pause for a moment to see if we have any questions.

Beth: Thanks so much, Claire. Something just came in here. Oh, yeah, so you just said this I think a little bit, but could you talk a little more and kind of address the question that the student had had on whether they can use first person in their personal experience when discussing personal experience, and specifically maybe tips for using first person in those cases too. Does that make sense?

Claire: Yes, it does. That's a great question. So, I know that some of you have probably heard beyond just don't use personal experience but you may have heard don't use "I," right, which is the first person. So, don't use "I," but using "I" isn't incorrect per APA, and I'll go over this a little about bit later, but the kinds of "I" statements you want to avoid are those I believe, I feel, I think statements. Unless of course your writing a personal reflection of some kind in which case those would be appropriate. But when you’re talking about personal experience you’re going to have to use "I," right. That just makes sense, it would be really weird to say something like, this this writer has experienced. Instead just say, in my workplace I have done this, I exemplify this theory when I do this really focusing on actions you've taken or things that you've observed in your workplace through the use of "I" is going to be much clearer for the readers and help them out. So, using "I" is not inappropriate for personal experience. It's really those other kind of more feeling‑based statements that you really want to watch out for.

Beth: Thank you so much, Claire. I think you just covered a little bit of examples of when to use that first person, and so I think we're good for now. Yeah. I'll keep watching out for more questions, but I think that covers it for now.

Claire: Thanks, Beth, and yeah, we will go can over some examples of using "I" a little bit further on in this presentation too, so you can look for that or look forward to that, sorry.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: When is using personal experience inappropriate?

- Avoid generalizing

- Our schools are failing. Parents want more individualized support for their children in the classroom.

- My daughter texts constantly, which shows that teenagers use cell phones more than they did in the past.

Audio: All right. So, when is using personal experience inappropriate? So, we talked about when it's appropriate, right, during your research process, when your assignment specifically asked for that reflection, that background information, or when you're exemplifying a theory in an assignment which has kind of asked for how you connect to the source reading for that week.

Right, so those are all great places and appropriate places to use that first person and that personal experience.

When using personal experience is inappropriate is using it as evidence in an argument, it's kind of like our Paragraph B from earlier. I noticed this at my school so all teenagers should go through drug testing and that's just too general, right. It's not backed up enough. You want to avoid generalizing. Personal experience can lead to those generalizations, so here are some examples.

Our schools are failing, parents want more individualized support for their children in the classroom, and so this is just really vague, right? This first one, it's really vague and how do I know that schools are failing, whose opinion is this, it's just the writer's opinion and that's probably not enough to say that our schools are failing, like they might be an authority on if their own school is failing, but that's a whole big other ‑‑ I assume they're talking about schools in the United States but they could be talking about the whole world, so it's important to be really specific and use that evidence to avoid those generalizations.

Our second example is my daughter texts constantly which shows that teenagers use cell phones more than they did in the past. So again, this observation, we can't expand it out to all teenagers or all schools or all anything from one personal experience, right? Even our own hospital or at our own high school that our daughter attends, we would have to actually do research and do some kind of study to make this type of statement because otherwise somebody could say anything they wanted, right. I could say, online students are lazy, which I know to be very untrue since I work with Walden students all the time, but I could just say that if we didn't need to have that evidence, if I was just going to use my own personal biased opinion, I could say whatever I wanted. I could say something like that and I wouldn't need to go find any research. I would just say it like it's true and move on, so to avoid that, to have that credibility, you want to have that research to back up statements and avoid using that personal experience, those personal observations, and stating them as facts that extend beyond your own observation.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Problems with Using Only Experience

- How does one person’s experience compete with verified and reported research involving many people?

- No foundation of knowledge

- No practice with library skills, research, and using sources

Audio: The problems with using only your personal experience in your work are that it's not a very convincing argument. As I sort of just explained, one person's experience, how does that compete with verified research involving many people or across many states or years. You know, one person's opinion just isn't as strong as that. There isn't a clear foundation of knowledge if you're only using personal experience, then you're not explaining, you know, how you contribute to the conversation that's already happening on this topic and that's one of my favorite, favorite things about academic writing is that we're constantly contributing to the conversations that are already happening in our field. And if it's just your opinion and you’re not taking into account what other people have already said or are saying on your topic, then you're not coming off as having a foundation of knowledge or really contributing to that conversation.

Also, the problem with only using experience is you won't get practice with those library skills, research, and using sources effectively. And you're going to need those skills as you progress through your programs, even if maybe you don't need them on your first few discussion posts, for example, you will need them throughout your program and to succeed in your fields.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Example of Effective Integration

By and large, substance abuse in the United States begins during adolescence. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2013) stated that on an average day 881,684 adolescents smoke cigarettes, 646,707 smoke marijuana, and 457,672 drink alcohol. Adult addicts typically report beginning substance use in adolescence. In fact, one in four Americans who started using addictive substances in their teens are addicted now, compared to one in 25 who began using after the age of 21 (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 2011). To address this pattern, school districts should implement prevention and intervention programs.

At my high school in suburban Atlanta, I helped create Clean Matters. The program follows the National Institute on Drug Abuse principles of …

Audio: All right. So, I want to talk about an example of that effective integration of personal experience with research, so this isn't only research, right, it's personal experience and research.

By and large, substance abuse in the United States begins during adolescents. The substance abuse and mental health services administration stated that on average, an average day, oh, man I'm so bad at reading numbers aloud. This many adolescents smoked cigarettes, marijuana, and drank alcohol. Adult addicts typically report beginning substance use in adolescence, and in fact one in four Americans who started using addictive substances in their teens are addicted now compared to 1 in 25 who began using at the age of 21. To address this pattern, school districts should implement prevention intervention programs. At my high school in suburban Atlanta, I helped create Clean Matters and the program follows the National Institute on Drug abuse Principles of ‑‑

So here you can see that we have this great effective paragraph, and this is that you might recognize as our Paragraph A from earlier, and so we have this effective paragraph that has lots of information from a source. We have a clear takeaway at the end, right? We're saying this is information that is true, here is what this means, this is an issue, it needs to be addressed, right? And here is what we can do.

Then we have an example of what someone is doing already, so for example I've seen some paper assignments that say something like establish your health issue, discuss what your community is doing to combat this issue, for example.

So, this would be a great place to establish your issue using that research and then include what you're doing in your community, especially if you do have that personal involvement and the assignment asked about your community, then this is a good place to use that personal experience and talk about the campaign that you personally worked on.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Chat

Chat: Did the author effectively

integrate their personal experience in this reflection paper?

Being an active listener is probably the most challenging part of my face-to-face communication. Although I choose my responses wisely and use skills such as validation and empathic listening, I struggle to be an active listener and easily get distracted by mental noises and perceptual biases. Active listeners are “people who focus on the moment, are aware of interactions as they unfold, respond appropriately, and are aware of distractions” (Dobkin & Pace, 2006, p. 98). To strengthen this skill, I must practice clearing my mind and eliminating distractions so I can fully focus on the messages I am receiving.

Audio: All right, so let's do another practice, now that we've done through an example of that effective integration. Did the author here effectively integrate their personal experience in this reflection paper, and why or why not? I will read it aloud for you. Being an active listening is probably the most challenging part of my face‑to‑face communication. Although, I choose my responses wisely and use skills such as validation and empathic listening, I struggle to be an active listener and easily get distracted by mental noises and perceptual biases Active listeners are people who focus on the moment, are, aware of interactions, respond appropriately and are aware of interactions. To strengthen this skill, I must practice clearing my mind and eliminating distraction so I can fully focus on the message I am receiving.

Go ahead and take a minute and then tell us what you think in the chat box.

[silence as students type]

I can see some people are still typing. I'll give you another minute to go ahead and finish up with your response here.

All right. It looks like our contributors have dried up, so I'm going to go ahead and talk over. If you're still typing, go ahead and keep typing and I'll just begin our discussion.

So, a lot of you said that you did think that this was effective in general because we do have some source information that we're dealing with here and we are tying that in to our personal experience. A few of you suggested having the evidence sort of earlier in the paragraph to help support the observations that the writer is making a little bit sooner rather than necessarily beginning with a personal, a sentence of personal experience. And you know, I think it really depends on what the assignment is, right, which is always the answer with personal experience. What is the assignment? This assignment is probably one that I've seen where you take some sort of, you know, assessment or quiz about your skills and then write a reflection about how you scored and what you can do to have kind of like an improvement plan, so that's what I'm guessing this is here.

And in that case, right, it probably is fine to have that personal experience right away in the paragraph because this is a more personal reflective type of assignment, but it's a good thing to keep in mind that you may want to start with an overall what is this paragraph really going to be about, what is the bigger kind of connection, think about your thesis, and then if there are personal details to add to have them a little bit later can be very effective as well.

So great observations, everybody. Thank you for participating.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Tips for Effectively Using Personal Experience

Audio: All right, so now we're going to go through some tips for effectively using that personal experience.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Effective Integration Tips

DO use the first-person point of view.

- Helps you avoid referring to yourself in the third person or passive voice.

- Unclear: In this writer’s role as an executive assistant, this writer compiles reports on financial transactions.

- Appropriate: In my role as an executive assistant, I compile reports on financial transactions.

Audio: All right, so as we sort of mentioned before with the questions about using "I," you use that first‑person point of view for your first‑person experience, right. It helps avoid referring to yourself in the third person or in passive voice, which can be very confusing for readers.

An example is in this writer's role an as executive assistant this writer compiles reports on financial transactions. That's not only repetitive, but it's a little confusing because in academic writing, right, we write about what other writers think all the time, so if I'm a reader and I'm seeing this, I'm thinking, okay, by this writer, do they mean the researcher they were just talking about in the last paragraph? Who do they mean? Who were they talking about exactly? So that can be really unclear. Whereas, in my role as an executive assistant I compile reports on financial transactions. There is nothing wrong with using first person in that way, right, because it's not biased, it's not opinionated, it's explaining what you do in your role so there is nothing inappropriate about that per APA.

This blog on including relevant details might be helpful!

DO stay on task.

- Ask yourself: Is this experience directly related to the assignment? How much does the reader really need to know?

- Too Much: I want to pursue a degree in social work at Walden. My stepfather kicked me out of the house when I was 14, and I became homeless. On the streets, I was scared and hungry and had to steal or beg to get by. I don’t want other teens to suffer like I did for many years.

- Appropriate: I want to pursue a degree in social work at Walden. The experience of being homeless as a teenager has made me empathetic toward other people in similar situations.

Audio: All right. You do want to stay on task, so what I see sometimes is even in those assignments that are asking for you to write about your own experience, I see some students get a little bit carried away and I know why because you're so excited to be able to write about that personal experience, to be able to share that you might end up getting kind of off topic and maybe sharing more than is strictly needed for the assignment, so you want to stay focused. You want to ask, is this experience directly related to the assignment? How much does the reader really need to know?

So here is an example. I want to pursue a degree in social work at Walden. My step‑father kicked me out of the house when I was 14 and I became homeless. On the streets I was scared and hungry and had to steal or beg to get by and I don't want other teens to suffer like I did for many years. So, do we need all of that information to understand why this person wants to pursue a degree at Walden?

We can probably cut it down, right. I want to pursue a degree in social work at Walden. The experience of being homeless as a teenager has made me empathetic towards other people in similar situations. So, we're taking the ideas and we're sort of paraphrasing ourselves, right. We're shrinking it down and we're focusing on what the point is, what's the importance of these personal details, what's the takeaway for the reader.

And I have a blog post on including relevant details that I wrote for these specific situations, so you can click that active link or if you're watching this as a recording, you can download the slides and you'll be able to review it there as well, so that has some more detailed examples if this sounds like something you maybe do.

DO Use an objective, formal, nonjudgmental voice (even if the content is very personal).

- Ask yourself: Is this voice appropriate for a professional context?

- Too casual: In my opinion, the students were behaving like brats. I couldn’t even get their attention to take attendance! I had to…

- Appropriate: One day at preschool, the students were particularly rambunctious. It was difficult to take attendance, so I …

Audio: Do remain objective, formal and nonjudgmental even if the content is very personal. Ask yourself, is this voice appropriate for professional context. And when I think of a professional context, I like to imagine that you are writing a letter to a person in your field who you greatly respect but have never met in person, so that might be a helpful visual for some of you, really thinking about that tone. You want to be formal, you want to be direct, you want to seem smart, right, so you want to avoid being overly emotional or, you know, judgmental potentially or opinionated.

Example is in my opinion; the students were behaving like brats. I couldn't even get their attention to take attendance, so here is that less appropriate use of "I" that we sort of talked about before, right. My opinion, so unless the prompt specifically asks for your opinion, then you shouldn't have statements like "in my opinion" or "I believe" and then we have, I couldn't even get their attention to take attendance, so we're just kind of complaining, right.

Instead, we can write one day at preschool the students were particularly rambunctious and so it was difficult to take attendance, so really, we're saying the same thing here but we just tweaked it. We made it more objective, more observable, and something you can think about is, if someone was watching you in your situation, would they find your description effective to paint the picture that they saw, right? Whereas like, students were behaving like brats, that's really subjective. Whereas, the students were energetic or rambunctious that's something that someone could easily observe if they were standing outside of the classroom and they could tell it was difficult for you to take attendance, but I couldn't even get their attention is very personal, that's drawing on not only your personal experience of what happened but you're sort of mental and emotional state while it was happening, so that's another thing to help you kind of focus in on remaining objective and clear, is to think about, am I portraying what happened or am I portraying my emotional response to what happened?

DO NOT wear “experience blinders.”

- Remain open

- Consult other sources and viewpoints, even contradictory ones

- Instead: Provide a citation for personal experience

Audio: All right. Don't wear those experience blinders. Remain open. Think about, you know, someone might say your experience just doesn't belong in this paper, you know, and that's not saying that your experience doesn't matter or isn't important or they're not informed and knowledgeable and intelligent about your topic. It's just, you know, it may not be for the assignment or it might just not match kind of that formal scholarly academic tone.

You can consult other sources and viewpoints, even contradictory ones on your topic, to help maintain that kind of neutral tone throughout even if you think you already have an opinion on it, and you can provide a citation instead of just your personal experience, right. You can provide a citation if you have written about it before, for example, or if you're drawing from your personal experience and you want to go look up something that mirrors what you experienced.

Chat: How would you pair personal

experience with this quote from an article?

Write 1-2 sentences.

“About 75% of the online students surveyed

indicated that they were more engaged in courses

that included images, video, and audio” (Sherman

& MacKenzie, 2015, p. 31).

Audio: All right. So here we have our last practice, so how would you pair personal experience with this quote from an article? And assume that this is appropriate, right, your assignment has asked you to pair personal experience, and so here is a quote. About 75% of the online students surveyed indicated they were more engaged in courses that included images, video, and audio. So, what's your personal experience that connects with this quotation? Write one to two sentences in the Chat Box and then we'll talk about some of them.

I'm seeing some great responses so far and I'm going to go ahead and give you guys another minute or so before we talk over these.

All right. I'm going to go ahead and start talking about a few of the examples that I pulled, but if you're still typing, please go ahead and continue typing.

All right, so one example is "I experience better engagement in courses when I start an online degree with Walden University, images, videos, and webinar and presentations helped me stay focused. So, that pairs nicely with our evidence because they found 75% of students were more engaged by this type of content, right, and so this person is adding to that by saying that they agree, right, and that they give some specifics as to what that looked like here at Walden, so that's a great use of personal experience.

All right. We have sort of an introduction, which was from teaching, information, literacy, and public speaking, my experience is that ‑‑ so that's a great introduction to kind of, what your experience was with that engaging content. I would caution you here to not then just have the quotation, right. Because your experience isn't that 75% of online students surveyed indicated their engagement, right. Your experience is that you also were more engaged by those image, video, and audio, right. You can only speak to your own experience and that's something that wasn't in this presentation, but which is important to think about. You don't want to pair a citation with an "I" statement because it doesn't make sense, right. That writer, Sherman and Mackenzie they didn't write about you. They wrote about subjects in their study. So, pairing with an "I" statement is confusing to readers and you want to make that statement separate from the evidence and show how it connects but you don't want to mash it together in the same sentence.

All right. In my experience as an online student, images, video, and audio have been beneficial in keeping me engaged in online courses. So that’s great, right? That's similar to the first one I read, having the nice specifics and they're agreeing with the statistics and supporting them with their own experience.

Personally, I find my attention is drawn to an attraction eye catching image or video, and right so again we're just kind of agreeing with that source information.

Here’s another one that kind of takes what is an "I" statement or personal statement and goes a little bit too far out from their own experience. From personal experience the use of video and images are imperative for effective learning. The only person you really have authority to say that about is yourself, right. So, from personal experience, the uses of videos are imperative for my learning to be effective is something that you are definitely qualified and should say, right, if that's true here, that would be a great use of personal experience. But you don't want to say, I also, like I agree and this is true for everybody. You don't want to go beyond yourself.

Research has proven that a good number of online students are engaged with video and audio learning experiences, and so that's more of a paraphrase of this quotation, right. That's not personal experience. It's not saying that I had this experience that is supported by this research, right, so there were so many great examples there and I really appreciate your input, and it just shows that this is a skill and it takes time and practice and it is way easier when it's an assignment you have in front of you and you know exactly what personal experience you want to use.

But I'm going to go ahead and move on so that we have time for questions at the end.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Additional Resources

- Avoiding Bias web page

- All About Audience podcast episode

- Why You Shouldn’t Wiki blog post

- APA blog post on personal experience

- Prior Learning Portfolio web page (UG students)

Audio: All right. So, I promise to use some additional resources at the beginning of this presentation and here are some great ones. We have an Avoiding Bias web page. We have all about audience podcast episode. We also have a podcast episode called Objectivity and Passion that is really good if you feel or if someone is saying that you are too emotional or too passionate about your topic, or you're getting a little opinionated, that's a good one too.

Why You Shouldn't use Wikipedia Blog Post we have an APA, APA has a blog post on personal experience, and for undergraduate students, there is a Prior Learning Portfolio web page to assist you.

Visual: Slide changes to the following: Questions: Ask Now or Later

[email protected] • Live Chat Hours

Learn More:

Check out the recorded webinars “What Is Academic Writing?”

and “Writing Effective Academic Paragraphs”

Audio: And before I turn it over for questions, I also wanted to note that I think a paper review, which I don't think was linked on a previous page, but a paper review is a really great resource too when you're using this personal experience and you're not sure if you are telling too much or, you know, if you're being too passionate about your topic or how well you're integrating that personal experience with those resources. You can send in your paper for a paper review through our paper review system, My Pass, and a writing instructor like myself will read it, give you feedback, and then attach a draft with comments and links in it the day of or day after your scheduled appointment. So that can be really useful and just let us know on your appointment form that you're kind of nervous about using personal experience effectively or would like some assistance with that, and we will focus on that in your review.

All right. Do we have any lingering questions, Beth?

Beth: Yeah. Thanks so much, Claire. Thank you so much. That was all fantastic first off. But we did have a question from a student who was saying, you know, what if their assignment is asking for their personal experience but they're just not coming up with ideas, like they're kind of having writer's block in that area. Do you have any strategies to help students generate ideas from their own personal experience?

Claire: That's a good question. Yeah, it can certainly be challenging, you know, especially if you're being asked, for example, if you're changing career paths and then you're being asked to sort of write about your experience in that career area. Because I have seen some assignments that are like that so I can see why it would be hard to sort of come up with an experience.

If you're really struggling and your faculty has kind of asked you to talk through a scenario or a leadership situation and you're just not coming up with one, then I would definitely reach out to your faculty and see if maybe you can use a scenario from some reading or talk through something like that because that can happen, right, where you just don't really have an experience that fits the bill.

As far as where you definitely know you have experiences, but you're kind of struggling to figure out which one to talk about, or you feel like there are too many, or you just don't know where to start, I would definitely try free writing, which is where, you know, you ask yourself about the topic and you just write for a given amount of time, so I usually start with like 10 minutes, and you just write about that topic, everything you can remember, everything you can think about related to that topic and your experience, and that can really help like jog your memory and focus in on specific events that might be helpful, but definitely, you know, especially if you're coming back to school from a ‑‑ from a while outside of school, then you might not remember a really clear memory to use for a specific example, and in that case I would definitely just ask your faculty and let them know what's going on because they're not trying to trip you up with that. They're just playing on how a lot of Walden students have relevant, current kind of experiences in their field and they're not meaning for you to not be able to complete the assignment.

Beth: That's fantastic, Claire. Can I provide maybe one other idea? I was just thinking of something that's just something I was thinking about.

Claire: Yeah

Beth: Depending on your assignment too, it's also helpful to sometimes read, I don't know, like other more popular research or just like do a Google Search on a topic. Maybe you know, the theoretical peer review journal articles you're reading about a topic just don't help you connect that top wick your own experience, maybe it's like a leadership style or something, but reading an article about leadership styles in a more informal publication that you wouldn't cite in your paper but that could help you generate ideas, that can sometimes sort of make it more real for you. That's been helpful for me in the past sometimes. I don't know, I just wanted to throw that out there as well. I hope that's okay.

Claire: Yeah, no. That's a great idea too. It doesn't have to be research to like spark your ideas. Maybe you want to go watch a TED Talk or you know find an infographic, Beth loves infographics, so find an infographic or find, you know, a little like life hacker article that kind of breaks it down.

Beth: Something yeah. I like that, and I know this is like, it felt so blasphemous when I just read it but sometimes it will even say go to the Wikipedia page on the topic, you won't cite the Wikipedia page but you might generate ideas from it or find other research that's cited on the page too, so yeah.

Okay. No other questions, Claire, that are coming in. Do you have any last thoughts you want to leave everyone with before we kind of wrap up?

Claire: Just, you know, make sure you're looking over your assignment really carefully when you're deciding if you want to use personal experience or not. And if you are ever unsure, ask your faculty. It is their job and they will know if they want personal experience or not in that paper and they will be able to tell you really clearly if you're not sure.

Beth: Perfect. Thank you so much, Claire. I'm seeing lots of thanks coming into the Q&A Box. Thank you, thank you everyone for attending, if you have any more questions, make sure to reach out and we hope to see you at another webinar coming up soon. Thanks, everyone.

- Previous Page: Welcome to the Writing Center

- Next Page: What Is Academic Writing?

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

What this handout is about

This handout will provide a broad overview of gathering and using evidence. It will help you decide what counts as evidence, put evidence to work in your writing, and determine whether you have enough evidence. It will also offer links to additional resources.

Introduction

Many papers that you write in college will require you to make an argument ; this means that you must take a position on the subject you are discussing and support that position with evidence. It’s important that you use the right kind of evidence, that you use it effectively, and that you have an appropriate amount of it. If, for example, your philosophy professor didn’t like it that you used a survey of public opinion as your primary evidence in your ethics paper, you need to find out more about what philosophers count as good evidence. If your instructor has told you that you need more analysis, suggested that you’re “just listing” points or giving a “laundry list,” or asked you how certain points are related to your argument, it may mean that you can do more to fully incorporate your evidence into your argument. Comments like “for example?,” “proof?,” “go deeper,” or “expand” in the margins of your graded paper suggest that you may need more evidence. Let’s take a look at each of these issues—understanding what counts as evidence, using evidence in your argument, and deciding whether you need more evidence.

What counts as evidence?

Before you begin gathering information for possible use as evidence in your argument, you need to be sure that you understand the purpose of your assignment. If you are working on a project for a class, look carefully at the assignment prompt. It may give you clues about what sorts of evidence you will need. Does the instructor mention any particular books you should use in writing your paper or the names of any authors who have written about your topic? How long should your paper be (longer works may require more, or more varied, evidence)? What themes or topics come up in the text of the prompt? Our handout on understanding writing assignments can help you interpret your assignment. It’s also a good idea to think over what has been said about the assignment in class and to talk with your instructor if you need clarification or guidance.

What matters to instructors?

Instructors in different academic fields expect different kinds of arguments and evidence—your chemistry paper might include graphs, charts, statistics, and other quantitative data as evidence, whereas your English paper might include passages from a novel, examples of recurring symbols, or discussions of characterization in the novel. Consider what kinds of sources and evidence you have seen in course readings and lectures. You may wish to see whether the Writing Center has a handout regarding the specific academic field you’re working in—for example, literature , sociology , or history .

What are primary and secondary sources?

A note on terminology: many researchers distinguish between primary and secondary sources of evidence (in this case, “primary” means “first” or “original,” not “most important”). Primary sources include original documents, photographs, interviews, and so forth. Secondary sources present information that has already been processed or interpreted by someone else. For example, if you are writing a paper about the movie “The Matrix,” the movie itself, an interview with the director, and production photos could serve as primary sources of evidence. A movie review from a magazine or a collection of essays about the film would be secondary sources. Depending on the context, the same item could be either a primary or a secondary source: if I am writing about people’s relationships with animals, a collection of stories about animals might be a secondary source; if I am writing about how editors gather diverse stories into collections, the same book might now function as a primary source.

Where can I find evidence?

Here are some examples of sources of information and tips about how to use them in gathering evidence. Ask your instructor if you aren’t sure whether a certain source would be appropriate for your paper.

Print and electronic sources

Books, journals, websites, newspapers, magazines, and documentary films are some of the most common sources of evidence for academic writing. Our handout on evaluating print sources will help you choose your print sources wisely, and the library has a tutorial on evaluating both print sources and websites. A librarian can help you find sources that are appropriate for the type of assignment you are completing. Just visit the reference desk at Davis or the Undergraduate Library or chat with a librarian online (the library’s IM screen name is undergradref).

Observation

Sometimes you can directly observe the thing you are interested in, by watching, listening to, touching, tasting, or smelling it. For example, if you were asked to write about Mozart’s music, you could listen to it; if your topic was how businesses attract traffic, you might go and look at window displays at the mall.

An interview is a good way to collect information that you can’t find through any other type of research. An interview can provide an expert’s opinion, biographical or first-hand experiences, and suggestions for further research.

Surveys allow you to find out some of what a group of people thinks about a topic. Designing an effective survey and interpreting the data you get can be challenging, so it’s a good idea to check with your instructor before creating or administering a survey.

Experiments

Experimental data serve as the primary form of scientific evidence. For scientific experiments, you should follow the specific guidelines of the discipline you are studying. For writing in other fields, more informal experiments might be acceptable as evidence. For example, if you want to prove that food choices in a cafeteria are affected by gender norms, you might ask classmates to undermine those norms on purpose and observe how others react. What would happen if a football player were eating dinner with his teammates and he brought a small salad and diet drink to the table, all the while murmuring about his waistline and wondering how many fat grams the salad dressing contained?

Personal experience

Using your own experiences can be a powerful way to appeal to your readers. You should, however, use personal experience only when it is appropriate to your topic, your writing goals, and your audience. Personal experience should not be your only form of evidence in most papers, and some disciplines frown on using personal experience at all. For example, a story about the microscope you received as a Christmas gift when you were nine years old is probably not applicable to your biology lab report.

Using evidence in an argument

Does evidence speak for itself.

Absolutely not. After you introduce evidence into your writing, you must say why and how this evidence supports your argument. In other words, you have to explain the significance of the evidence and its function in your paper. What turns a fact or piece of information into evidence is the connection it has with a larger claim or argument: evidence is always evidence for or against something, and you have to make that link clear.

As writers, we sometimes assume that our readers already know what we are talking about; we may be wary of elaborating too much because we think the point is obvious. But readers can’t read our minds: although they may be familiar with many of the ideas we are discussing, they don’t know what we are trying to do with those ideas unless we indicate it through explanations, organization, transitions, and so forth. Try to spell out the connections that you were making in your mind when you chose your evidence, decided where to place it in your paper, and drew conclusions based on it. Remember, you can always cut prose from your paper later if you decide that you are stating the obvious.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself about a particular bit of evidence:

- OK, I’ve just stated this point, but so what? Why is it interesting? Why should anyone care?

- What does this information imply?

- What are the consequences of thinking this way or looking at a problem this way?

- I’ve just described what something is like or how I see it, but why is it like that?