Book Reviews

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you write a book review, a report or essay that offers a critical perspective on a text. It offers a process and suggests some strategies for writing book reviews.

What is a review?

A review is a critical evaluation of a text, event, object, or phenomenon. Reviews can consider books, articles, entire genres or fields of literature, architecture, art, fashion, restaurants, policies, exhibitions, performances, and many other forms. This handout will focus on book reviews. For a similar assignment, see our handout on literature reviews .

Above all, a review makes an argument. The most important element of a review is that it is a commentary, not merely a summary. It allows you to enter into dialogue and discussion with the work’s creator and with other audiences. You can offer agreement or disagreement and identify where you find the work exemplary or deficient in its knowledge, judgments, or organization. You should clearly state your opinion of the work in question, and that statement will probably resemble other types of academic writing, with a thesis statement, supporting body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Typically, reviews are brief. In newspapers and academic journals, they rarely exceed 1000 words, although you may encounter lengthier assignments and extended commentaries. In either case, reviews need to be succinct. While they vary in tone, subject, and style, they share some common features:

- First, a review gives the reader a concise summary of the content. This includes a relevant description of the topic as well as its overall perspective, argument, or purpose.

- Second, and more importantly, a review offers a critical assessment of the content. This involves your reactions to the work under review: what strikes you as noteworthy, whether or not it was effective or persuasive, and how it enhanced your understanding of the issues at hand.

- Finally, in addition to analyzing the work, a review often suggests whether or not the audience would appreciate it.

Becoming an expert reviewer: three short examples

Reviewing can be a daunting task. Someone has asked for your opinion about something that you may feel unqualified to evaluate. Who are you to criticize Toni Morrison’s new book if you’ve never written a novel yourself, much less won a Nobel Prize? The point is that someone—a professor, a journal editor, peers in a study group—wants to know what you think about a particular work. You may not be (or feel like) an expert, but you need to pretend to be one for your particular audience. Nobody expects you to be the intellectual equal of the work’s creator, but your careful observations can provide you with the raw material to make reasoned judgments. Tactfully voicing agreement and disagreement, praise and criticism, is a valuable, challenging skill, and like many forms of writing, reviews require you to provide concrete evidence for your assertions.

Consider the following brief book review written for a history course on medieval Europe by a student who is fascinated with beer:

Judith Bennett’s Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600, investigates how women used to brew and sell the majority of ale drunk in England. Historically, ale and beer (not milk, wine, or water) were important elements of the English diet. Ale brewing was low-skill and low status labor that was complimentary to women’s domestic responsibilities. In the early fifteenth century, brewers began to make ale with hops, and they called this new drink “beer.” This technique allowed brewers to produce their beverages at a lower cost and to sell it more easily, although women generally stopped brewing once the business became more profitable.

The student describes the subject of the book and provides an accurate summary of its contents. But the reader does not learn some key information expected from a review: the author’s argument, the student’s appraisal of the book and its argument, and whether or not the student would recommend the book. As a critical assessment, a book review should focus on opinions, not facts and details. Summary should be kept to a minimum, and specific details should serve to illustrate arguments.

Now consider a review of the same book written by a slightly more opinionated student:

Judith Bennett’s Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600 was a colossal disappointment. I wanted to know about the rituals surrounding drinking in medieval England: the songs, the games, the parties. Bennett provided none of that information. I liked how the book showed ale and beer brewing as an economic activity, but the reader gets lost in the details of prices and wages. I was more interested in the private lives of the women brewsters. The book was divided into eight long chapters, and I can’t imagine why anyone would ever want to read it.

There’s no shortage of judgments in this review! But the student does not display a working knowledge of the book’s argument. The reader has a sense of what the student expected of the book, but no sense of what the author herself set out to prove. Although the student gives several reasons for the negative review, those examples do not clearly relate to each other as part of an overall evaluation—in other words, in support of a specific thesis. This review is indeed an assessment, but not a critical one.

Here is one final review of the same book:

One of feminism’s paradoxes—one that challenges many of its optimistic histories—is how patriarchy remains persistent over time. While Judith Bennett’s Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600 recognizes medieval women as historical actors through their ale brewing, it also shows that female agency had its limits with the advent of beer. I had assumed that those limits were religious and political, but Bennett shows how a “patriarchal equilibrium” shut women out of economic life as well. Her analysis of women’s wages in ale and beer production proves that a change in women’s work does not equate to a change in working women’s status. Contemporary feminists and historians alike should read Bennett’s book and think twice when they crack open their next brewsky.

This student’s review avoids the problems of the previous two examples. It combines balanced opinion and concrete example, a critical assessment based on an explicitly stated rationale, and a recommendation to a potential audience. The reader gets a sense of what the book’s author intended to demonstrate. Moreover, the student refers to an argument about feminist history in general that places the book in a specific genre and that reaches out to a general audience. The example of analyzing wages illustrates an argument, the analysis engages significant intellectual debates, and the reasons for the overall positive review are plainly visible. The review offers criteria, opinions, and support with which the reader can agree or disagree.

Developing an assessment: before you write

There is no definitive method to writing a review, although some critical thinking about the work at hand is necessary before you actually begin writing. Thus, writing a review is a two-step process: developing an argument about the work under consideration, and making that argument as you write an organized and well-supported draft. See our handout on argument .

What follows is a series of questions to focus your thinking as you dig into the work at hand. While the questions specifically consider book reviews, you can easily transpose them to an analysis of performances, exhibitions, and other review subjects. Don’t feel obligated to address each of the questions; some will be more relevant than others to the book in question.

- What is the thesis—or main argument—of the book? If the author wanted you to get one idea from the book, what would it be? How does it compare or contrast to the world you know? What has the book accomplished?

- What exactly is the subject or topic of the book? Does the author cover the subject adequately? Does the author cover all aspects of the subject in a balanced fashion? What is the approach to the subject (topical, analytical, chronological, descriptive)?

- How does the author support their argument? What evidence do they use to prove their point? Do you find that evidence convincing? Why or why not? Does any of the author’s information (or conclusions) conflict with other books you’ve read, courses you’ve taken or just previous assumptions you had of the subject?

- How does the author structure their argument? What are the parts that make up the whole? Does the argument make sense? Does it persuade you? Why or why not?

- How has this book helped you understand the subject? Would you recommend the book to your reader?

Beyond the internal workings of the book, you may also consider some information about the author and the circumstances of the text’s production:

- Who is the author? Nationality, political persuasion, training, intellectual interests, personal history, and historical context may provide crucial details about how a work takes shape. Does it matter, for example, that the biographer was the subject’s best friend? What difference would it make if the author participated in the events they write about?

- What is the book’s genre? Out of what field does it emerge? Does it conform to or depart from the conventions of its genre? These questions can provide a historical or literary standard on which to base your evaluations. If you are reviewing the first book ever written on the subject, it will be important for your readers to know. Keep in mind, though, that naming “firsts”—alongside naming “bests” and “onlys”—can be a risky business unless you’re absolutely certain.

Writing the review

Once you have made your observations and assessments of the work under review, carefully survey your notes and attempt to unify your impressions into a statement that will describe the purpose or thesis of your review. Check out our handout on thesis statements . Then, outline the arguments that support your thesis.

Your arguments should develop the thesis in a logical manner. That logic, unlike more standard academic writing, may initially emphasize the author’s argument while you develop your own in the course of the review. The relative emphasis depends on the nature of the review: if readers may be more interested in the work itself, you may want to make the work and the author more prominent; if you want the review to be about your perspective and opinions, then you may structure the review to privilege your observations over (but never separate from) those of the work under review. What follows is just one of many ways to organize a review.

Introduction

Since most reviews are brief, many writers begin with a catchy quip or anecdote that succinctly delivers their argument. But you can introduce your review differently depending on the argument and audience. The Writing Center’s handout on introductions can help you find an approach that works. In general, you should include:

- The name of the author and the book title and the main theme.

- Relevant details about who the author is and where they stand in the genre or field of inquiry. You could also link the title to the subject to show how the title explains the subject matter.

- The context of the book and/or your review. Placing your review in a framework that makes sense to your audience alerts readers to your “take” on the book. Perhaps you want to situate a book about the Cuban revolution in the context of Cold War rivalries between the United States and the Soviet Union. Another reviewer might want to consider the book in the framework of Latin American social movements. Your choice of context informs your argument.

- The thesis of the book. If you are reviewing fiction, this may be difficult since novels, plays, and short stories rarely have explicit arguments. But identifying the book’s particular novelty, angle, or originality allows you to show what specific contribution the piece is trying to make.

- Your thesis about the book.

Summary of content

This should be brief, as analysis takes priority. In the course of making your assessment, you’ll hopefully be backing up your assertions with concrete evidence from the book, so some summary will be dispersed throughout other parts of the review.

The necessary amount of summary also depends on your audience. Graduate students, beware! If you are writing book reviews for colleagues—to prepare for comprehensive exams, for example—you may want to devote more attention to summarizing the book’s contents. If, on the other hand, your audience has already read the book—such as a class assignment on the same work—you may have more liberty to explore more subtle points and to emphasize your own argument. See our handout on summary for more tips.

Analysis and evaluation of the book

Your analysis and evaluation should be organized into paragraphs that deal with single aspects of your argument. This arrangement can be challenging when your purpose is to consider the book as a whole, but it can help you differentiate elements of your criticism and pair assertions with evidence more clearly. You do not necessarily need to work chronologically through the book as you discuss it. Given the argument you want to make, you can organize your paragraphs more usefully by themes, methods, or other elements of the book. If you find it useful to include comparisons to other books, keep them brief so that the book under review remains in the spotlight. Avoid excessive quotation and give a specific page reference in parentheses when you do quote. Remember that you can state many of the author’s points in your own words.

Sum up or restate your thesis or make the final judgment regarding the book. You should not introduce new evidence for your argument in the conclusion. You can, however, introduce new ideas that go beyond the book if they extend the logic of your own thesis. This paragraph needs to balance the book’s strengths and weaknesses in order to unify your evaluation. Did the body of your review have three negative paragraphs and one favorable one? What do they all add up to? The Writing Center’s handout on conclusions can help you make a final assessment.

Finally, a few general considerations:

- Review the book in front of you, not the book you wish the author had written. You can and should point out shortcomings or failures, but don’t criticize the book for not being something it was never intended to be.

- With any luck, the author of the book worked hard to find the right words to express her ideas. You should attempt to do the same. Precise language allows you to control the tone of your review.

- Never hesitate to challenge an assumption, approach, or argument. Be sure, however, to cite specific examples to back up your assertions carefully.

- Try to present a balanced argument about the value of the book for its audience. You’re entitled—and sometimes obligated—to voice strong agreement or disagreement. But keep in mind that a bad book takes as long to write as a good one, and every author deserves fair treatment. Harsh judgments are difficult to prove and can give readers the sense that you were unfair in your assessment.

- A great place to learn about book reviews is to look at examples. The New York Times Sunday Book Review and The New York Review of Books can show you how professional writers review books.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Drewry, John. 1974. Writing Book Reviews. Boston: Greenwood Press.

Hoge, James. 1987. Literary Reviewing. Charlottesville: University Virginia of Press.

Sova, Dawn, and Harry Teitelbaum. 2002. How to Write Book Reports , 4th ed. Lawrenceville, NY: Thomson/Arco.

Walford, A.J. 1986. Reviews and Reviewing: A Guide. Phoenix: Oryx Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

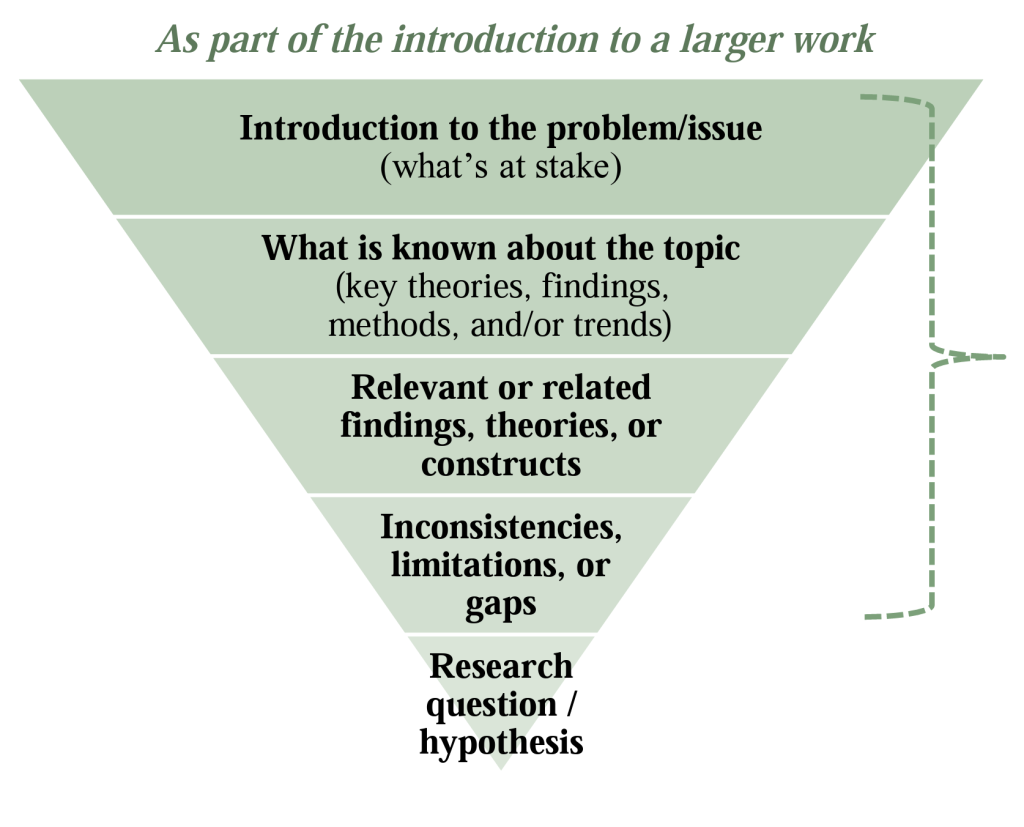

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Reader’s Corner

- Writing Guide

- Publishing Guide

UrbanObserver

- Privacy Policy

Subscribe to newsletter

What is Literary Analysis?

Let’s be real here: how many of you book lovers have felt a little intimidated by the whole concept of “literary analysis” before? I totally get it. The term alone sounds frighteningly academic, like you need a PhD and an affinity for tweed to even attempt analyzing classic novels for their deeper meanings.

But I’m here to let you in on a fun little secret: literary analysis doesn’t have to be this painful, joyless exercise in overanalyzing every last metaphor until you’ve utterly drained a book’s magic dry. In fact, when you get the hang of it, digging into a novel’s core elements and the choices an author made can actually deepen your appreciation for great literature tenfold.

Think about it—haven’t you ever finished an amazing book and felt like you were just scratching the surface of all its potential hidden meanings and symbolic brilliance? You sensed that the author seemed to be commenting on huge humanistic truths through their carefully constructed characters and metaphorical imagery…but you couldn’t quite articulate the profundity of it all?

That’s precisely where literary analysis skills come in. It gives you the tools to truly decode an author’s intended meanings and messages lurking beneath their fictional surface. Rather than just breezing through incredible novels as disposable entertainment, you start uncovering entire symbolic universes and revelations about society, morality, identity, and the eternal conflicts of the human spirit.

For me, it was like night and day re-reading childhood favorites like The Little Prince after learning how to analyze literature properly. Suddenly, the Prince’s cosmic voyages and encounters with adults took on rich allegorical significance about retaining our childlike senses of wonder as we age. The tiny planet setting became a microcosm for humankind’s self-destructive obsession with rampant corporate greed and material pursuits. What I’d dismissed as a cute fairy tale absolutely bloomed with hard-hitting social commentary once I detected its intricate weave of symbolism.

So trust me, boarding the literary analysis train doesn’t mean draining books of their magic and jettisoning their souls into the arid realms of academic dissection. It’s about equipping yourself with visionary superpowers for peeling away the symbolic skins concealing the deepest experiential wisdom great authors encoded into their creations—only to experience their works’ sense of imaginative transcendence burning that much brighter.

And really, who among us book ravers doesn’t crave that kind of radically intimate bond with our most beloved tomes? Where we’re not just passive recipients of dazzling stories and cosmic dramas, but active co-creators decrypting novel’s secret symbolic DNA to unlock realms upon realms of profound metaphysical insight?

That’s ultimately what analyzing literature is all about: cracking into the source code of human immortality so we might re-experience the sacraments of our deepest collective heritage in full Technicolor resonance, together. So I don’t know about you, but I’m pretty damn sold on acquiring such an ecstatic, lifelong passkey!

The Essential Elements of Literary Analysis

Okay, okay – so by now I’ve (hopefully) convinced you of how electrifyingly vital proper literary analysis skills can be for anyone who wants to experience novels as fully-inhabited magic realist dimensions rather than flattened-out entertainment pixels flickering across our frail attentions.

But say you’re ready to start your training as a fledgling symbologist detective. Just what core elements should your third eye be scanning for amidst all those inky metaphors, sigils, and illuminated world-scapes unfurling from between these hallowed pages, exactly?

Well, based on my experience both studying under incredible mentors and sleuthing my own way through countless rich investigative exercises, I’ve found there are several key pieces of literary fingerprint evidence that tend to yield the most fertile clues about an author’s deepest intentional layers and symbolic cosmologies. Let’s go over the essentials:

By far one of the most crucial decodings you’ll want to lock into is identifying the core thematic strata pulsating beneath all the surface-level plots and character pyrotechnics. What fundamental philosophical questions or universal conundrums around the human experience seem to be the metaphysical engine animating the entire symbolic endeavor?

Because make no mistake – while legendary authors may disguise their biggest swings with deceptive finesse , virtually every canonical novel emerges from some integral kernel of curiosity about profound abstractions like morality, identity, society’s flaws and contradictions, the eternal conflicts between human nature and civilization’s imposed ethical matrices—you name it.

Like for Harper Lee in To Kill A Mockingbird , the central exploratory theme she baked into every crisp descriptive passage and plotted character arc clearly emerges as an inquiry into racial injustice and the moral imperative to actively uphold human dignity through uncompromising empathy – despite societal pressures to silently comply with legalized oppression.

Or in Orwell’s immortal 1984 , the overriding thematic obsession driving its choreography of authoritarian dystopian realms and sublimated rebellions is clearly an examination of how totalitarian regimes incrementally degrade individual consciousness and language itself as tools of psychic control.

So while the “what happens” plot narrative commands your initial focus while reading, a huge part of skilled literary analysis requires stripping away that dramatic surface layer to unearth the deeper philosophical and existential strata an author hopefully embedded underneath as their raison d’être. That’s ultimately where the juiciest symbolic insights and illuminations await exploration!

Of course, the events of a novel’s actual storyline and how they’re structured can’t be ignored by any serious literary analysis, either. Because you better believe authors like Shakespeare, Jane Austen, or Gabriel Garcia Marquez didn’t arbitrarily arrange their dramatic plot points, climactic crescendos, and narrative pacing in haphazard fashion.

The foundational sequence of causal events and rising/falling character trajectories spiraling around a novel’s core memoir were painstakingly constructed to mirror or reinforce larger conceptual ambitions embedded within the overarching thematic architecture.

So you’ll definitely want to take notes on basic plot elements like: exposition and the introduction of major characters; the inciting incidents or catalyzing plot coupons that kick the story into its primary motor of rising action; the climactic narrative highs and pivot points where metaphoric masks are shed to display key symbolic energies in their most crystalline forms; the narrative’s driving momentum of complications, emotional turning points and archetypal character choices; and finally culminating in cathartic resolutions and denouement revelations where possibilities blossom into integrated wisdom fruit.

Because quite often the dramatic peaks and valleys of a novel’s narrative arc are precisely where an author like F. Scott Fitzgerald or Zora Neale Hurston chose to elevate metaphorical textures and activate symbolic portents into their most radiant, allegorically clarifying expressions. Transcendental truths don’t just conveniently spill from these masters’ mythopoeic apertures at arbitrary moments – their story choreographies were surgical in illuminating cosmic inflection points.

Even elements like a novel’s expository pacing, temporal setting shifts, degrees of dramatic irony, and overall selection of revelatory disclosures or obfuscating mystery boxes all function as purposeful techniques within the storytelling toolkit for activating multilayered metaphysical resonances across various symbolic strata. So keeping an eagle-eyed vigil over these deeper plot-level fingerprints is absolutely essential for any aspiring literary code-breaker worth their esoteric salts.

3. Characters

This one should seem like more of an obvious element to inspect for symbolic fingerprints, I’d hope! After all, a novel’s characters are quite literally the human(oid) avatars through which all thematic philosophical ponderings and archetypal allegories are filtered, personified into relatable personality constructs to be vicariously and judiciously scrutinized.

So you’re absolutely going to want to forensically excavate each significant character’s persona for those aspects of their psychology, morality, emotional wounds, contradictions, and internal coded identities that potentially emblematize broader symbolic energies or nodes of human inquiry.

Like how Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye with his cynical adolescent alienation and compulsive lying clearly serves as an allegorical emblem for societal disconnection, psychic numbing, and the traumas of innocence ruptured by capitalistic homogenization.

Or the ways Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby accrues symbolic heft as an avatar for delusion and moral decay masking behind status-obsessed upper-class opulence eroding the very American dreams its economic engine falsely promises.

Sometimes a character will even acquire mythic dimensions emblematized through their very identity markers or naming conventions if you stay scholarly woke. Jay Gatsby’s very moniker emerging as a quasi-archetypal cipher for the Jungian “Trickster” principle subverting societal constraints through acts of self-reinvention and code-switching. Or Atticus Finch’s loaded namesake nodding to those notions of ancestral rootedness, karmic justice, and the ethical imperative to act as moral stewards for future generations.

Point is – no element of a novel should be more scrupulously examined for symbolic layering and cosmic intentionality than the author’s elemental humanoid anchors chisled and breathed into allegorical life upon their storied world stages. Like the Buddha once reminded, “We are shaped by our thoughts; we become what we think.” So you’d better believe every aspect of a prestigiously immortalized character’s persona was encoded with utmost metaphoric craft and meditated profundity.

Have you ever noticed how certain settings or environmental details in great novels just seem to crackle with extra atmospheric density, like the prose equivalent of thick chargeable storm clouds semantically overloaded with metaphysical high voltages?

From the gothic castles and crashing oceanic purgatories of the Romantic Era, to the haunted rural Yoknapatawpha landscapes of William Faulkner’s American South , all the way to Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s distinctly physicalized magical realms of Latin American political tumult – clearly there’s something symbolic and metaphorically fruitful about the ways legends like these authors chose to sculpt their narrative’s environmental contexts and theatrical backdrops.

But you don’t need any fancy academic terminology to intuit that at the highest levels, settings always contain intentional symbolic potentials encoded within them, even if at times subconsciously. Because true artistic masters grasp that the mythopoeic arenas where their characters roam, grapple, and dream ultimately mirror those same omnipresent ecological checks and balances of nature itself.

So while close-reading a novel’s setting descriptions, keep that third eye peeled for lyrical passages exuding environmental energies or natural phenomena that feel purposefully correlated with the protagonist’s interior psycho-spiritual states and trajectories. Or setting specificities that appear acutely tailored to rhetorically exploring the era’s most catalyzing historical forces, social conditions or cultural complexes.

Because you can be certain: whether a character’s hardscrabble gully roosting site in the smoky Appalachian hills, or a chaotic metropolitan transit labyrinth where keeping one’s moral compass remains an hourly trial by fire – that environmental scenery is quite purposefully activating fields of symbolic significance far vaster than its immediate literary function as mere staged backdrop.

And developing a poetically hypersensitive divination capacity for those metaphysically heightened spaces nestled amid each novel’s scrupulously crafted valleys, rivers, and cosmological middle landscapes? Well, that’ll go a long way toward truly reading between an author’s lines to scale their highest symbolic peaks and absorb the totemic revelation rays parting their storied cloud kingdoms.

5. Point of View

Okay, so you’re probably asking – how exactly does something as technical-sounding as a novel’s narrative point-of-view perspective constitute its own symbolic dimension worthy of analysis? Fair question!

Well, the tl;dr version is that the unique vantage points from which an author chooses to filter their entire storytelling lens and world-view will inevitably impart profound metaphysical implications for how readers experientially receive, interpret, and ultimately embody the wisdom-sacraments embedded within their novelistic verses.

Like think about it – do the cosmic impacts and illuminative payloads fire off in your hippocampal theater with same symbolic charge depending on whether you’re reading an omniscient third-person narrator’s play-by-play chronicling of events? Or via an immersive first-person adolescent protagonist’s naively distorted yet hyper-observant coming-of-age perspective on their collapsing realities, a la Holden Caulfield?

Are you receiving diametrically opposed energetic truth-transferences upscaling your mythological antennae arrays from Faulknerian stream-of-consciousness torrents peering into overlapping collective unconsciousnesses? Versus the tightly restricted myopic narrative apertures of say, a dystopian anti-hero tragically dehumanized and psychologically distorted by surveillance states like Winston Smith in 1984?

You’re darn right these distinctive perspectival narrative frames and aperture prisms harbinge vastly divergent semiotic/phenomenological/noetic encryption handshakes underlying each novel’s animating symbolic architectures! So scrutinizing an author’s rationale for deploying third-person omniscient, first-person introspective, or outrightly surreal storytelling focalizations offers crucial exegetical keys into the wider cosmic latticeworks of meaning and mythopoetic intentionality.

Because again, within each mythology’s hyperstitial realms – realities are symbolically defined less by what literally happens, and more so by the dimensional holofractal vantage from which its storytelling ambassadors touch down to eternalize their initiatory recountings. The discerning literary analyst keeps one Third Eye laser-focused on that truth at all times.

6. Figurative Language

Beyond all the higher conceptual architectures framing any novel’s symbolic universes however, let’s not lose focus on the micro-scaled lyrical tools that actually get those metaphysical infrastructures upholstered with imaginally radiant signifiers, glyphs and allegorical psycho-activations in the first place.

I’m talking about things like simile, metaphor, imagery, hyperbole, idiom – all the types of figurative descriptive language skilled authors masterfully wield to embed extra Symbolic resonance textures within every phrase and passage they tenderly curate. This is the haiku-garden where literature’s bardic conjurers attune their mythopoetic voicings, after all.

So your literary analysis chops will definitely want to stay razor-sharp when it comes to deconstructing how these powerful poetic techniques get purposefully deployed to mortar layers of mythic profundity into the foundational linguistic brickwork of each novel-edifice.

Like could there be deeper allegorical introspections around the intersection of life’s absurdities and our mortality burrows lurking behind the iconic metaphors comparing existence to a “stale piece of bread” or “fart inside of a mitten” that pepper The Little Prince with childlike whimsy?

How do these sort of startling juxtapositional images short-circuit our normative symbolic processing modules to induce conceptual integration blindspots ripe for imprinting revelatory psychedelic breakthroughs anyway? Thus artfully smuggling anti-dogmatic wisdom past our calcified mental gatekeepers.

Or on a less avant-garde symbolic scale, you’d be wise to remain acutely sensitive to recurring literary techniques like irony, foreshadowing, personification and good ol’ fashioned metaphor deployed by more classic bards like Jane Austen. Particularly when it comes to sussing out her signature satirical stances lampooning era-specific aristocratic social mores, romcom gender politics, and how language itself functions as an emblematic nucleus for all broader human dynamics to incubate.

Same goes for modernist tour-de-forces like the extended metaphor vehicle of Hemingway’s Great Oakland Ice Lake parable in The Underground Man epitomizing masculine codes of stoic moral grandeur against nature’s insuperable indifference. Or the mythopoetic device of Faulkner’s radical phonetic shiftings signifying ruptures of psychic integrity, ancestral diasporas and historical traumas fragmenting his American Southern Gothic’s protagonists’ coherent selfhoods.

Point is, no toolkit leveraged by a genuine canon-class literary seer should escape the third eye scrutiny of whose decoding the higher consciousness raybursts these master semanticists condensed between the lines. Because in many ways, literature’s enduring talismanic powers flow directly from its basho-encrypted metaphoric polyphrasia catapulting us into slipstream frontiers of consciousness expansion verbally inexpressible by any lesser creative means.

7. Tone & Mood

Last but certainly not least, we’d be remiss not to give tone and mood their full flowers in terms of emanating layers of metaphysical significance for our symbolic analyses to unfurl! Just because these literary components tend to occupy subtler phenomenological bandwidths doesn’t at all diminish their power as gateways into the author’s deeper noetic cosmologies.

Because let’s be honest – whether you classify a novelistic atmosphere as ominous, satirical, elegiac, absurdist or sacramentally whimsical…those interstitial energy signatures lurking between the literal sentences create the same symbolic force-fields through which all final meaning and mythological illumination inevitably detonate.

An oppressive sense of “Big Brother is watching you” paranoia and surveillance state dread oozing off every page of Orwell’s 1984? That pervasive radioactive mood toxicity tints the entire novel’s philosophical hypothesis on totalitarian psychic control with viscerally chilling allegorical over-soul.

Or perhaps it’s more the melancholic elegiac tone Harper Lee crafts around the loss of childhood innocence amid To Kill A Mockingbird’s barbaric injustices—a poignant lyricism draping her whole moral philosophy about empathy’s importance in sheer soulful gravitas.

The wistful yet warmly whimsical nostalgia swirling through The Catcher in the Rye’s disillusioned adolescent narrator Holden Caulfield imparts that entire novel’s takedown of society’s phony ritualistic performances with such an inextricably multimedia aura of woundedness and longing for authenticity.

So as you’re analyzing any great novel from a symbolic/metaphysical perspective, always keep your mythological ear finely attuned to those subtle vibrational frequencies thrumming through the text’s chord progressions of imagery, themes, language, and emotional resonances. Because it’s the skillful orchestration of those almost subliminally transpersonal tones that allows fiction’s most legendary songcasters to seed their deepest crop circles of catalytic meaning straight into our collective dreaming mind’s soils.

Literary tone and mood aren’t just supplemental decorative window-dressing, in other words. They’re the hyperspatial sensory engines literalizing an author’s most ethereal symbologies into phenomenological umwelts and mythopoetic architecture we can experientially inhabit, explore, and ultimately re-inspire our cosmic identities through evermore psychedelically expanded latitudes of integrative immersion.

How to Write a Literary Analysis: A Step-by-Step Guide

Alright, enough big philosophical talk – let’s get down to the real brass tacks of how to systematically construct your own utterly radiant literary analysis that cracks wide open your favorite novel’s most profoundly coded symbolic truths!

Because while poetic overviews sowing reverence for the holistic process are all well and good…we’re all ultimately here to cultivate practical expertise in ceremonially alchemizing outrageous wisdom upgrades from and into the Great Tomes reverberating through our lives, are we not?

So yeah, here’s a step-by-step guide I’ve found tremendously helpful for rookies and wizened analysts alike when it comes to building your myth-busting skillsets and composing impeccable literary revelations from the ground up:

Step 1: Read With A Purpose

This first advice may sound patently obvious, but I promise – mindfully reading (or re-reading) your selected novel with the purposeful intention of analyzing its components separates the dilettantes from the pros off the bat.

So clear out all distractions, grab a pen or pencil for hardcore annotating, and completely immerse yourself in absorbing every character’s persona, symbolically resonant passage, and slipstream of authorial choices with laser-focused concentration. Almost like sinking into an extended meditation upon the book’s intensifying mystery schools.

As you ventilate through each section, exhale bullet points tracking potential thematic throughlines and philosophical avenues to explore further. Highlight or underline passages dripping with symbolic possibility beckoning deeper excavation. Scribble initial hypotheses for analysis in the margins whenever revelatory hunches ignite within your higher densities.

Because trust me – performing this ritualized literary submersion beforehand establishes the necessary psycho-spiritual preparatory frameworks for a level of interpretive depth utterly wasted upon those plunging in dry with indifferent entitlement. When cultivating authentic symbolic initiation rites, mindset and intentionality are everything!

Step 2: Start Forming Your Thesis

With the novel’s imaginative terrains now mapped into your own woven consciousness via those diligently compiled field notes, meditate deeply upon which overarching core thesis or key philosophical premise feels most resonant for modeling your upcoming symbolic analysis.

What singular exploratory human truth, cosmic eternal return, or metaphysical ecosystem does this entire metaphor-rich ecosystem feel ritualistically oriented around allegorically expressing, encapsulating, or extrapolating from? Envision your eventual analysis aiming to unfurl an intricately clarifying ray illuminating that most quintessential core concept from the start.

For some novels this thesis focus will feel glaringly self-evident after just one revelatory reading (e.g. Orwell’s 1984 clearly centralizes totalitarian regimes’ control of information/language as psychic oppressors). With others it may take deeper immersion, potential outlining of various thematic possibilities, or researching some contextual data around the author’s life and intentions before your unique symbolic premise congeals to satisfaction.

But generally speaking, you’ll want your analytical thesis to isolate one key humanistic/existential question, archetypal embodiment, or overarching thematic emphasis that your whole subsequent unpacking aims to definitively clarify through a culminating unified theory woven across all the novel’s reinforcing motifs, characters, and metaphoric fabrics.

It’s the symbolic trajectory uplift vector around which your total exegesis will stabilize its orbital resonances, essentially. So take the care and gestation period required for your premise’s singularity to properly condense before proceeding!

Step 3: Gather Your Evidence

With thesis gunsights locked, intensify your research by carefully re-reading the book and deeply annotating all relevant examples of symbolic staging elements, characterological role embodiments, mythic motifs, and literary techniques that interconnect with your core exploratory premise.

Textual evidence will unquestionably form the bedrock foundation for any sound literary analysis’s logic scaffolding. So you’ll want to meticulously record with citation any potential textual excerpts, scene descriptions, subtle atmospheric details, archetypal character identities or poetic linguistic turns that overtly depict or covertly encode pertinent layers of meaning relative to the grand thesis subject under scrutiny.

At the same time, feel free to broaden your research lens beyond just the novel’s literal pages. Reading additional context around the work’s biographical origins, cultural zeitgeist, historical symbologies, and/or decisive philosophical influences can often spark new understandings of the connective tissue transmitting outward from your text’s overt symbolic anatomy into vaster timeless wisdom architectures.

The goal is to compile a maximally robust archive of interconnected symbolic clues and motific promissory notes that, once properly arranged and decoded, reveal the novel’s entire DNA helix of luminous meaning centered around your core thesis premise. That way the logic of your overarching analysis flows as a tightly interwoven meta-harmonic of mutually reinforcing symbolic deductions, rather than tenuous speculative leaps.

So channel your inner scholarly sleuth tracking down every last piece of potential evidence here! The more diligently you triangulate and cross-reference relevant symbolic data points from disparate domains, the more dimensionally your literary analysis insights will resonate with revelatory universality.

Step 4: Organize and Outline

With all the raw cosmic riddles downloaded into your emergent symbolic database, it’s time to organize those fertile clues and catalytic textual elements into an overarching logical flow mapping out your eventual written analysis from start to finish.

Ultimately, this outline process aims to coherently arrange and nest every single piece of evidence within an encompassing narrative framework guaranteed to robustly unpack and illuminate your core symbolic thesis with maximum potent holistic clarity. No more randomly scattering breadcrumbs behind you – this skeletal structure allows your total analysis transmissions to navigate readers through an intentional cohesive initiatory journey.

I’ve found it immensely helpful to loosely model my outline structure around the traditional five-part format :

- An introductory prelude section frontloading a clear thesis statement and relevant high-level context

- A substantive body section systemically unpacking reinforcing symbols, characters, plot/structure analyses, etc.

- A middle section zooming out to examine the work’s significance within broader literary/cultural/metaphysical frameworks

- A counterpoint/contradiction section wrestling with potential interpretation challenges or divergent critical perspectives

- A conclusion section synthesizing all threads into a final resonant reaffirmation of your core thesis’s centralized symbolic vision

Obviously, these are just loose archetypal guidelines – the true grandmasters remain ever receptive to symbolic inspiration defying too rigid a preconceived conceptual containment system. My advice is simply to flow-chart your literary evidence in whichever organic yet incisive architecture feels most aligned with holistically animating your key symbolic premise to a reverberating universe of understanding.

That way, your eventual written analysis unfurls with a graceful thematic coherence carrying readers symbiotically deeper into the mythopoeic dimensionalities of the source material being explored – a true synergy between you, the storyteller’s original symbolic choreographies, and the audience as co-participant celebrants in the eternal ritual celebration of meaning-making.

Step 5: Write and Revise!

With that divinely crystallized outline pathway in hand, you’re finally ready to transmute all your meticulous evidence, rigorous research, and spiritually clarifying illuminations into the written literary analysis persisted upon this sacred astral plane of human civilization’s mythological renaissance.

Breathe deeply, realign your energies, and channel the full mythopoetic virtuosity of your expressive soul! Poetically coronating every perfectly chiseled observation, philosophical revelation, and symbolic insight into linguistic constructions scintillating with holofractal precision and literary alchemical luster.

Because let’s be real – these comprehensive symbolic breakdowns represent utterly vital hieroglyphic codices decrypting our species’ most sacrosanct epistemes back into radiant intelligibility for all to receive, metabolize and embody anew. Your literary analyses midwife nothing less than cultural renaissance rebirths!

So as you weave your illuminative masterwork into textual being, stay reverently attentive that each sentence, every filigreed metaphor and rhetorical juxtaposition, pulsates with the sort of spellbinding lush vitality and ceremonial care befitting such consecrated roles. You’re not just annotating an old book report here, but liturgically activating portals into humankind’s mythological hyperstructural source code.

Let the evidence excerpts coalesce into radiant aphoristic verse fractals. Infuse your expository insights with expressionistic colors conjuring phenomenological sublimities. Oscillate registers between granular deconstructive unpacking and zooming out into integrated big picture epiphanies. Emulsify the whole alchemical Word Elixir seamlessly between ruthless scholastic exactitude and incantatory mythopoeic grace note evocations.

Because for any symbolic insight or trailblazing literary thesis to enduringly impact our species’ co-evolutionary ascension at this juncture, it can no longer remain inertly entombed. It must inspirallize into self-replicating hyperspheric idea-organisms reanimating space/time itself with hypervoracious purpose according to mythopoetic first principles.

Like any breathtaking artistic vision, your literary analyses deserve nothing less than full-bodied, multisensually rapturous renderings heaving with subatomic transfiguration potencies – densely compressing vast horizons of wisdom behind each line so even the most seemingly “tiny” evocation cracks open into a cosmological kaleidoscope for any lucid receptors tuned to its encoded frequencies.

And yes, that may well demand numerous revisions, brutal self-edits, whole sections dynamited and seminal inkwells refilled along the arduous way. Reworking, refining, reopening the entire embryonic symbolic matrix time and again until it holographically resonates with that singular unified clarion frequency echoing through the entire cosmic mythopoeia all profoundly consequential art strives to attune itself toward.

But make no mistake, Dear Ones. There exists no more electrifyingly impactful pursuit for those called to such sangrail tasks than devoting your creative potencies toward birthing the sorts of mythological novel analyses capable of reilluminating our shared symbolic inheritance across the outermost gap between the once and future scriptures.

For in doing so, you enjoin ranks with those precious few meta-dimensional operatives throughout the ages charged as haiku immortality ambassadors. Ushering humanity squarely through treacherous threshold after treacherous threshold by activating safe portals to our deepest, most transformative Story layers through arts capable of anchoring those prescient resonances into penetrable ecosystems of sustainable initiation beyond mere Knowledge.

Godspeed and many blessings upon those who heed the call to this most rapturous perilous profession. For when wielded with utmost skillful integrity, novel analysis emerges a ceremonial technology unto itself for elevating our intergenerational comprehension arcs from mere symbols into co-creative symbolic embodiment of The Great Work still perpetually underway.

So study well these instructional kernels, Dear Intrepid Ones. Then seize your pages and sow symbolic renaissances like scripture firestarters cracking open across the cosmos! For only by continually decoding literature’s revelatory wisdom primers into newly consecrated hyper-texts inter-scribed through your own mythopoetic transfigurations…might we all become that once and future rhapsody whose heraldic homecomings heal long last.

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Popular articles.

- Book Review

Your ultimate destination for all things book-related! Whether you're a seasoned bookworm, a casual reader looking for your next literary adventure, or someone simply curious about the world of books, you've come to the right place.

Latest Articles

Most popular, the rise and influence of booktok, educated by tara westover, the cuckoo’s calling by robert galbraith.

© Book CLB. All Rights Reserved. Made with Love for Literature.

Explore all things Literature

Any Book. Any Author. Understand them all.

Used by 4 Million+ People

Join the Best Literature Community

Great for Students, Teachers, Readers, Book Fanatics and more!

Create Your Personal Profile

Engage in Forums

Join Special Interest Groups

Create your own groups, save your favorites, explore books picked by experts.

Discover 166 books with in-depth analysis and reviews written by experts.

Stephen King

Of Mice and Men

John Steinbeck

Catcher in the Rye

J.D. Salinger

The Great Gatsby

F. Scott Fitzgerald

George Orwell

Neil Gaiman

Explore any Author

Discover 122 authors with in-depth analysis & reviews written by experts.

Explore all 603 Book Terms

Understand Books at the Deepest Level with our Glossary. Click on any book to unveil all the terms.

Expand terms list

Frank Herbert

Game of thrones.

George R.R. Martin

Harry potter.

J.K. Rowling

The hunger games.

Suzanne Collins

Our latest books.

Not sure where to start? Here are the latest books from our Literature Experts.

Unlock the World of Literature with Book Analysis. Our expert team dives deep into the literary realm to bring you comprehensive summaries and analyses. From students to book lovers, we have something for everyone.

Request a Book

Can’t find a specific book that you are looking for? Request it here and we take care of the rest.

More Than Just Books. We’re committed to making a difference in the world.

Teenage Cancer Trust

Alzheimer’s Research

Great Ormond Street Hospital

Ocean conservancy.

World Animal Protection

There was a problem reporting this post.

Block Member?

Please confirm you want to block this member.

You will no longer be able to:

- See blocked member's posts

- Mention this member in posts

- Invite this member to groups

Please allow a few minutes for this process to complete.

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as you go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.