A systematic literature review to clarify the concept of vaccine hesitancy

Affiliations.

- 1 Radboud University Medical Center, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Primary and Community Care, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. [email protected].

- 2 Radboud University Medical Center, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Primary and Community Care, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

- 3 Behavioural Science Institute, Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

- 4 Radboud University Medical Center, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, IQ Healthcare, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

- PMID: 35995837

- DOI: 10.1038/s41562-022-01431-6

Vaccine hesitancy (VH) is considered a top-10 global health threat. The concept of VH has been described and applied inconsistently. This systematic review aims to clarify VH by analysing how it is operationalized. We searched PubMed, Embase and PsycINFO databases on 14 January 2022. We selected 422 studies containing operationalizations of VH for inclusion. One limitation is that studies of lower quality were not excluded. Our qualitative analysis reveals that VH is conceptualized as involving (1) cognitions or affect, (2) behaviour and (3) decision making. A wide variety of methods have been used to measure VH. Our findings indicate the varied and confusing use of the term VH, leading to an impracticable concept. We propose that VH should be defined as a state of indecisiveness regarding a vaccination decision.

© 2022. The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Limited.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Patient Acceptance of Health Care*

- Research Design

- Vaccination

- Vaccination Hesitancy*

- Vaccination Refusal

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- News & Views

- Published: 23 November 2022

Defining and measuring vaccine hesitancy

- Heidi J. Larson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8477-7583 1 , 2

Nature Human Behaviour volume 6 , pages 1609–1610 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

5563 Accesses

34 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health policy

- Science, technology and society

When the term ‘vaccine hesitancy’ first appeared, it was deemed ambiguous and difficult to measure. A systematic review of published articles on vaccine hesitancy suggests it should be defined as a state of indecisiveness regarding a vaccination decision, independently of behaviour, and that it needs new modes of analysis and measurement.

Vaccine hesitancy has become a household term in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, with more people in the world thinking about vaccines than perhaps at any time in our history. The term ‘hesitancy’ was already gaining traction in vaccine discussions in the decade before COVID-19 erupted, and had become a growing topic of research and public health concern: the World Health Organization (WHO) had already named vaccine hesitancy as one of the top ten global health threats in 2019.

But what does vaccine hesitancy really mean? And how useful is it in terms of actionable measures to address it? In a recent article in Nature Human Behaviour — an extensive review of over 400 articles — Bussink-Voorend and colleagues 1 investigate how the concept of vaccine hesitancy is characterized and measured. They find that vaccine hesitancy is operationalized in a number of ways, and conclude that it is therefore not a practicable concept.

This comprehensive review and analysis updates the field beyond a previous 2014 systematic review 2 , and is not the first to question the usefulness and specificity of the term vaccine hesitancy — a liminal state of uncertainty in making a vaccination decision. Early references cited in the paper challenged various characterizations of vaccine hesitancy as being an unspecific and ambiguous notion 3 in need of a clear definition 4 . Bussink-Voorend et al. make a strong case for distinguishing between hesitancy and behaviour, and argue that including behaviour within a definition of vaccine hesitancy is not tenable. This disputes the 2014 WHO Sage Working group definition of vaccine hesitancy as a behavioural phenomenon; however, it is also a point made in Maya Goldenberg’s recent book Vaccine Hesitancy 5 , which similarly rejects the definition of vaccine hesitancy as a behaviour. In their conclusion, Bussink-Voorend et al. propose that vaccine hesitancy should be defined as “a state of indecisiveness regarding a vaccination decision.”

For a concrete example of the distinction between vaccine hesitancy as a psychological state and a behaviour, we can look to the recent example of the French health pass 6 . A survey of a representative sample of French adults asked respondents how they felt after getting a COVID-19 vaccine: “Were you relieved? Did you feel regret? Or were you angry?” Between March and September 2021, they discovered a striking increase in the proportion of people feeling regret or anger after COVID-19 vaccination. Even more telling was the finding that the number of people who had doubts about the vaccine — despite being vaccinated — increased from 44% to 61% after the government introduced the health pass. This suggests that many vaccinated people remained in a psychological state of indecisiveness. Thus, the health pass encouraged vaccination but did not reduce hesitancy, confirming the importance of distinguishing between vaccine hesitancy and behaviour.

This is also in agreement with a recent narrative review of vaccine hesitancy, which discusses the many different influencing factors along the path of decision-making towards accepting, delaying or refusing a vaccine 7 . Vaccine hesitancy is not a static state; instead, vaccine decision-making is a journey with ups and downs, and changes over time with different influences and nudges along the path that sometimes prompt hesitancy and sometimes nudge a positive intention to vaccinate. In the case of COVID-19 vaccines, the constantly evolving information environment — including new information (and misinformation), changing guidance and requirements, and a volatile and changing epidemic context that affected risk perceptions and the felt need (or not) for vaccination — were all factors that have prompted changing sentiments around the vaccines, sometimes prompting eagerness and at other times hesitancy, delays or outright refusal of vaccination.

The dynamic nature of vaccine hesitancy is not discussed in Bussink-Voorend et al.’s review. Nonetheless, in their conclusions the authors argue that vaccine hesitancy is “a psychological state of being undecided,” and psychological states are dynamic by nature. This changing, even volatile, and emotive nature of vaccine hesitancy also requires new disciplines of analysis beyond the public health, social science and biomedical studies reviewed in the paper. ‘Big data’ analyses, such as those from computer science and engineering, are crucial when it comes to analysing and measuring the dynamic and viral nature of hesitancy 8 .

Overall, as discussed in Bussink-Voorend’s review and in related literature, the distinction between the affective nature of vaccine hesitancy in the context of decision-making, and it being a behaviour, is crucial. Vaccine hesitancy is not a behaviour.

Where does this leave us in terms of research and measurement of vaccine hesitancy? Maybe we are asking the wrong questions and need to look at the new realities of contested science, challenged governments and publics armed with their own notions of evidence.

Bussink-Voorend, D., Hautvast, J. L. A., Vandeberg, L., Visser, O. & Hulscher, M. E. J. L. Nat. Hum. Behav . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01431-6 (2022).

Larson, H. J., Jarrett, C., Eckersberger, E., Smith, D. M. D. & Paterson, P. Vaccine 32 , 2150–2159 (2014).

Article Google Scholar

Peretti-Watel P., Larson H. J., Ward J. K., Schulz W. S. & Verger P. PLoS Curr . 7 , ecurrents.outbreaks.6844c80ff9f5b273f34c91f71b7fc289 (2015).

Bedford, H. et al. Vaccine 36 , 6556–6558 (2018).

Goldenberg, M. Vaccine Hesitancy: Public Trust, Expertise, and the War on Science (Univ. Pittsburgh Press, 2021).

Ward, J. K. et al. Nat. Med. 28 , 232–235 (2022).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Larson, H. J., Gakidou, E. & Murray, C. J. L. N. Engl. J. Med. 387 , 58–65 (2022).

Sear, R., Leahy, R., Restrepo, N. J., Lupu, Y. & Johnson, N. (2022) Machine learning reveals adaptive COVID-19 narratives in online anti-vaccination network. In Proc. 2021 Conf. of the Computational Social Science Society of the Americas (eds Yang, Z. & von Briesen, E.) 164–175 (Springer, 2022).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK

Heidi J. Larson

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Heidi J. Larson .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

H.J.L.’s research group has received grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, GSK, Hong Kong Government, Johnson & Johnson, MacArthur Foundation, Merck, NIHR (UK) and UNICEF.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Larson, H.J. Defining and measuring vaccine hesitancy. Nat Hum Behav 6 , 1609–1610 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01484-7

Download citation

Published : 23 November 2022

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01484-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Between now and later: a mixed methods study of hpv vaccination delay among chinese caregivers in urban chengdu, china.

- Vivian Wan-Cheong Yim

- Qianyun Wang

BMC Public Health (2024)

Understanding the role of risk preferences and perceptions in vaccination decisions and post-vaccination behaviors among U.S. households

- Jianhui Liu

- Bachir Kassas

- Zhifeng Gao

Scientific Reports (2024)

Social Processes and COVID-19 Vaccination of Children of Hesitant Mothers

- Don E. Willis

- Rachel S. Purvis

- Pearl A. McElfish

Journal of Community Health (2024)

Institutional trust is a distinct construct related to vaccine hesitancy and refusal

- Sekoul Krastev

- Oren Krajden

BMC Public Health (2023)

COVID-19 vaccine refusal associated with health literacy: findings from a population-based survey in Korea

- Inmyung Song

- Soo Hyun Lee

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

Search life-sciences literature (43,904,411 articles, preprints and more)

- Full text links

- Citations & impact

- Similar Articles

A systematic literature review to clarify the concept of vaccine hesitancy.

Author information, affiliations.

- Bussink-Voorend D 1

- Hautvast JLA 1

- Vandeberg L 2

- Hulscher MEJL 3

ORCIDs linked to this article

- Hulscher MEJL | 0000-0002-2160-4810

- Vandeberg L | 0000-0002-7229-2378

- Bussink-Voorend D | 0000-0002-9873-1404

Nature Human Behaviour , 22 Aug 2022 , 6(12): 1634-1648 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01431-6 PMID: 35995837

Abstract

Full text links .

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01431-6

References

Articles referenced by this article (385)

Progress Toward Regional Measles Elimination - Worldwide, 2000-2019.

Patel MK , Goodson JL , Alexander JP Jr , Kretsinger K , Sodha SV , Steulet C , Gacic-Dobo M , Rota PA , McFarland J , Menning L , Mulders MN , Crowcroft NS

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, (45):1700-1705 2020

MED: 33180759

Economic Costs of Measles Outbreak in the Netherlands, 2013-2014.

Suijkerbuijk AW , Woudenberg T , Hahne SJ , Nic Lochlainn L , de Melker HE , Ruijs WL , Lugner AK

Emerg Infect Dis, (11):2067-2069 2015

MED: 26488199

The economic cost of measles: Healthcare, public health and societal costs of the 2012-13 outbreak in Merseyside, UK.

Ghebrehewet S , Thorrington D , Farmer S , Kearney J , Blissett D , McLeod H , Keenan A

Vaccine, (15):1823-1831 2016

MED: 26944712

Inpatient morbidity and mortality of measles in the United States.

Chovatiya R , Silverberg JI

PLoS One, (4):e0231329 2020

MED: 32343688

Resurgence of measles in the United States: how did we get here?

Feemster KA , Szipszky C

Curr Opin Pediatr, (1):139-144 2020

MED: 31790030

Resurgence of Measles in Europe: A Systematic Review on Parental Attitudes and Beliefs of Measles Vaccine.

Wilder-Smith AB , Qureshi K

J Epidemiol Glob Health, (1):46-58 2020

MED: 32175710

Barriers to childhood immunization in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review.

Bangura JB , Xiao S , Qiu D , Ouyang F , Chen L

BMC Public Health, (1):1108 2020

MED: 32664849

Bibliometric analysis of global scientific literature on vaccine hesitancy in peer-reviewed journals (1990-2019).

BMC Public Health, (1):1252 2020

MED: 32807154

The Long Road Toward COVID-19 Herd Immunity: Vaccine Platform Technologies and Mass Immunization Strategies.

Frederiksen LSF , Zhang Y , Foged C , Thakur A

Front Immunol, 1817 2020

MED: 32793245

Herd Immunity: Understanding COVID-19.

Randolph HE , Barreiro LB

Immunity, (5):737-741 2020

MED: 32433946

Citations & impact

Impact metrics, citations of article over time, alternative metrics.

Smart citations by scite.ai Smart citations by scite.ai include citation statements extracted from the full text of the citing article. The number of the statements may be higher than the number of citations provided by EuropePMC if one paper cites another multiple times or lower if scite has not yet processed some of the citing articles. Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been supported or disputed. https://scite.ai/reports/10.1038/s41562-022-01431-6

Article citations, exploring human papillomavirus vaccine hesitancy among college students and the potential of virtual reality technology to increase vaccine acceptance: a mixed-methods study..

Yoon S , Kim H , An J , Jin SW

Front Public Health , 12:1331379, 13 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38414894 | PMCID: PMC10896851

"Every Time It Comes Time for Another Shot, It's a Re-Evaluation": A Qualitative Study of Intent to Receive COVID-19 Boosters among Parents Who Were Hesitant Adopters of the COVID-19 Vaccine.

Moore R , Purvis RS , Willis DE , Li J , Langner J , Gurel-Headley M , Kraleti S , Curran GM , Macechko MD , McElfish PA

Vaccines (Basel) , 12(2):171, 07 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38400154 | PMCID: PMC10892107

Perceived impact of discussions with a healthcare professional on patients' decision regarding COVID-19 vaccine.

Charmasson A , Ecollan M , Jaury P , Partouche H , Frachon A , Pinot J

Hum Vaccin Immunother , 20(1):2307735, 12 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38346925 | PMCID: PMC10863372

COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy among Nurses in Thailand: Implications, Challenges, and Future Prospects for Attitudes and Vaccine Literacy.

Butsing N , Maneesriwongul W , Visudtibhan PJ , Leelacharas S , Kittipimpanon K

Vaccines (Basel) , 12(2):142, 29 Jan 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38400126 | PMCID: PMC10892553

The impact of risk perception and institutional trust on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in China.

Chen G , Yao Y , Zhang Y , Zhao F

Hum Vaccin Immunother , 20(1):2301793, 28 Jan 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38282324 | PMCID: PMC10826627

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Understanding the determinants of vaccine hesitancy and vaccine confidence among adolescents: a systematic review.

Cadeddu C , Castagna C , Sapienza M , Lanza TE , Messina R , Chiavarini M , Ricciardi W , de Waure C

Hum Vaccin Immunother , 17(11):4470-4486, 02 Sep 2021

Cited by: 21 articles | PMID: 34473589 | PMCID: PMC8828162

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Qualitative Assessment of Vaccine Hesitancy in Romania.

Miko D , Costache C , Colosi HA , Neculicioiu V , Colosi IA

Medicina (Kaunas) , 55(6):E282, 17 Jun 2019

Cited by: 17 articles | PMID: 31213037 | PMCID: PMC6631779

Vaccine Hesitancy in Rural Pediatric Primary Care.

Mical R , Martin-Velez J , Blackstone T , Derouin A

J Pediatr Health Care , 35(1):16-22, 01 Oct 2020

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 33010996 | PMCID: PMC7527836

Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and uptake in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review.

Deml MJ , Githaiga JN

BMJ Open , 12(11):e066615, 18 Nov 2022

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 36400736 | PMCID: PMC9676416

COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Pakistan: A Mini Review of the Published Discourse.

Khalid S , Usmani BA , Siddiqi S

Front Public Health , 10:841842, 31 May 2022

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 35712302 | PMCID: PMC9194092

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

ZonMw (1)

Evaluating interventions to stimulate acceptance of nip vaccinations: the role of deliberation on experiences and values..

DR Hautvast, Radboudumc

Grant ID: 839190002

1 publication

Europe PMC is part of the ELIXIR infrastructure

Peer Reviewed

Vaccine hesitancy in online spaces: A scoping review of the research literature, 2000-2020

Article metrics.

CrossRef Citations

Altmetric Score

PDF Downloads

We review 100 articles published from 2000 to early 2020 that research aspects of vaccine hesitancy in online communication spaces and identify several gaps in the literature prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. These gaps relate to five areas: disciplinary focus; specific vaccine, condition, or disease focus; stakeholders and implications; research methodology; and geographical coverage. Our findings show that we entered the global pandemic vaccination effort without a thorough understanding of how levels of confidence and hesitancy might differ across conditions and vaccines, geographical areas, and platforms, or how they might change over time. In addition, little was known about the role of platforms, platforms’ politics, and specific sociotechnical affordances in the spread of vaccine hesitancy and the associated issue of misinformation online.

Media, Inequality and Change Center, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania, USA

Communication, Journalism, & Media, Suffolk University, USA

MINDS (Management in Networked and Digital Societies), Kozminski University, Poland

Center for Constructive Communication, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA

School of Computer Science, University College Dublin, Ireland

Digital Health Lab, Meedan, USA

Tecnologico de Monterrey, Mexico

Digital Democracies Institute, Simon Fraser University, Canada

Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, University of Washington, USA

Research Questions

- RQ1: How was vaccine hesitancy—defined as “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services” (MacDonald & the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy, 2015, p. 4161)—in online spaces studied in the academic literature from 2000 to 2020?

- RQ2: What were the research gaps in the academic literature in relation to this area of investigation as of early 2020?

Essay Summary

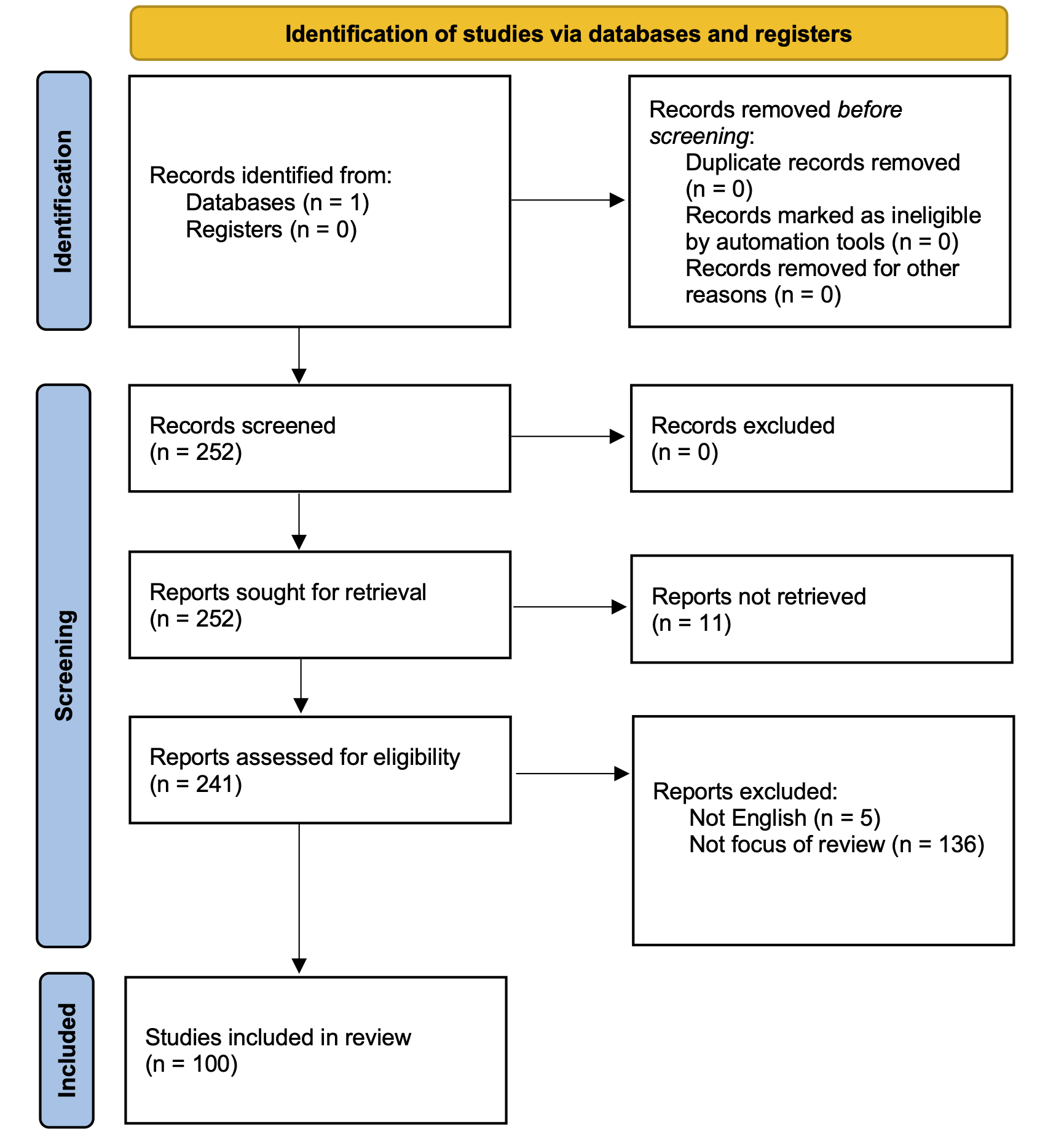

- We searched the Web of Science database for articles researching aspects of vaccine hesitancy in online spaces. Of 236 articles selected for analysis, 100 were determined relevant to our research interest and content analyzed by human coders.

- We identified gaps in the academic literature pertaining to vaccine hesitancy and the associated issue of online misinformation prior to the pandemic in five areas: disciplinary focus; specific vaccine, condition, or disease focus; geographical focus; stakeholders and implications; research methodology.

- Although this literature has greatly expanded, as of early 2020 it had yet to fully grapple with key dimensions of how vaccine hesitancy may be expressed in online discourse, specifically how online vaccine hesitancy differs across diseases, digital spaces, and local contexts, and how it might change over time. In addition, as of early 2020 very little appeared in the literature about the role of social media platforms in preventing and addressing the spread of vaccine hesitancy and online misinformation.

- Most of the articles we analyzed were produced within the field of public health research. In general, more interdisciplinary research is needed.

Implications

Globally and with increasing intensity during the present COVID-19 pandemic, efforts have been taken to address adherence to vaccine implementation across a spectrum of vaccine confidence levels, where low levels can contribute to hesitancy to vaccinate, and, potentially, the spread of related misinformation. Our research examines the lower end of the vaccine confidence spectrum, focusing on vaccine hesitancy and related challenges. 1 Researchers have used both the term “vaccine hesitancy” and the term “vaccine confidence” to refer to sentiments about vaccines, “hesitancy” drawing attention to negative sentiments and “confidence” inclusive of positive sentiments. We use the term “vaccine hesitancy,” which we operationalize as search terms used in our scoping review, such as “refusal,” “skepticism,” and “critical” (see Methods), referring to sentiments expressing the lower end of what has been studied as a spectrum of confidence levels (de Figueiredo et al., 2020; Larson, 2020; Orenstein et al., 2015).

Though vaccine hesitancy, misinformation, and online environments offer different sets of issues, health officials and researchers acknowledge important overlaps, as achieving broad acceptance of vaccines requires understanding information ecosystems (Berman, 2020; Larson, 2020). Vaccine hesitancy also has associated challenges that are specific to different vaccines, including COVID-19 vaccines, yet the persistence of varying degrees of confidence in vaccines more broadly is an ongoing challenge, and online environments have long been gathering points where vaccine rumors and myths are shared (Burki, 2020).

In this article, we conduct a scoping review 2 Unlike systematic reviews, scoping reviews seek to identify concepts and characteristics across extant literature rather than seeking to answer a specific question about a topic related to that literature (Munn et al., 2018). of the existing academic research on online vaccine hesitancy and suggest directions for future research. Though we acknowledge that vaccine hesitancy and the related issue of vaccine misinformation are not exclusively or most importantly online problems, our review provides a valuable snapshot of the state of research on this growing area of concern (RQ1), including potential research gaps (RQ2), prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the impact of the pandemic on global dialogues about vaccination adherence, including effective communication to promote vaccination among diverse communities, it is useful to create a baseline for future research that can address challenges to vaccine uptake related to the present pandemic and future diseases. Our review also can serve as a point of comparison for understanding how the present pandemic tests prior research findings and influences future research.

Our review covers two decades in which research focusing on vaccine hesitancy online emerged and steadily evolved. In the early 2000s, researchers studied vaccine information on websites and even at this earliest stage of online research noted the prevalence of “misleading or inaccurate information” (article ID 19), the spread of anecdotal accounts of vaccine dangers, and the misrepresentation of the science behind vaccines (ID 6). Though we did not use the term “misinformation” in our database search string (see Methods), search results show that the relationship between online vaccine hesitancy and the quality of online information is a persistent concern in the research literature, and our review frequently encountered articles referencing “misinformation” (e.g., IDs 21, 60, 98, 104, 106, 138, 195) or expressing concerns for the accuracy of information (IDs 15, 23, 157).

With the emergence of participatory “Web 2.0” websites and technologies enabling Internet users to generate content and interact with each other via social media, researchers recognized the potential for the public spread of private concerns about vaccines (ID 10), which challenges the information-gatekeeping power of health professionals (ID 3). Research in the 2010s increasingly examined the sources of information about vaccines and network dynamics that help these sources spread information, finding that vaccine hesitancy is prevalent online (IDs 21, 73, 131) but often circulates in small but active and cohesive subgroups of Internet users (IDs 60, 92, 109, 244, 225). Researchers also have increasingly recognized nuances among different forms of vaccine hesitancy (IDs 34, 98) and have explored the power of storytelling vs. the power of facts and statistics prevalent on official health sites (IDs 23, 45, 138, 165, 187). Conclusions increasingly have urged monitoring and moderating social media platforms to stop the spread of misinformation (IDs 178, 243).

Our review identifies gaps in this literature in five areas:

- Disciplinary focus

- Disease and vaccine focus

- Geographical focus

- Stakeholders and implications

- Research methodology

In terms of disciplinary focus, a majority of the articles we analyzed were published in journals in the field of public health and medicine and focus on understanding how people share information about vaccines online. Articles identified online discourse that may contribute to vaccine hesitancy (ID 127); analyzed which subpopulations of users are likely to amplify vaccine misinformation (ID 15); investigated whether search engines return quality information sources (ID 83). These analyses aim to develop tactics and tools to help public health officials surveil in real-time public opinions and attitudes toward immunization and leverage online media to better communicate their messages.

Only 35 of the 100 articles we looked at examined vaccine hesitancy in relation to a specific disease and vaccine, most prominently measles, mumps, rubella (MMR), and the human papillomavirus (HPV), while 65 analyzed generic vaccine hesitancy or hesitancy across multiple diseases. The predominance of general studies is concerning because interventions should take account of the unique characteristics of specific vaccines and diseases.

Most articles we reviewed were conducted by Western research institutions and focused on vaccine hesitancy within Western contexts. We removed non-English articles prior to content analysis, but even considering this limitation of our review, the predominately Western focus in the extant research is clear. One consequence of this Western focus in the available research may be that the field becomes primarily aimed at developing vaccine-related digital communication strategies while overlooking issues of access to vaccines. Also, such strategies may be inappropriate in regions grappling with diseases not prominent in the West, such as polio.

In part due to the prominence of the field of public health in the extant research, health authorities and professionals are most often identified as top stakeholders in addressing vaccine hesitancy and online misinformation. Proposed actions for this category of stakeholders include getting involved in online groups that spread misinformation (ID 60); including stories alongside scientific facts in communication efforts (ID 209); and adopting “vaccine ambassador” programs, in which community members or health professionals share reliable information with select audiences to promote vaccine confidence and adherence (ID 23).

Though health professionals intervene at the nexus of vaccines, information, and patients, the dynamics of how information spreads involve a broader set of issues, such as online platforms’ politics and sociotechnical affordances and coordinated efforts by actors external to the doctor-patient relationship. These dynamics also involve a broader set of stakeholders, such as platforms, news media organizations, and policymakers who can intervene at a structural level. These stakeholders are prominent in media studies, sociology, human-computer interaction, political science, and other fields positioned to make valuable contributions to research on vaccine hesitancy and misinformation online.

In terms of research methodology, few of the articles we reviewed made causal inferences. It is therefore difficult to confirm underlying factors in the online spread of vaccine hesitancy and related misinformation, or to recommend concrete strategies. We also found few studies focused on changes in expressions of vaccine hesitancy over time, beyond the ebb and flow (volume) of online activity, a finding that is likely connected to platform restrictions on access to data. Yet, in order to identify effective interventions, it is imperative to understand the long-term growth of online communities, how they connect to other communities, and how issue framings evolve.

Finally, as of early 2020, little attention had been paid to social media platforms beyond Facebook and Twitter that are well-known for playing major roles in the distribution and amplification of online misinformation, such as YouTube and Reddit (Cinelli et al., 2020; Kaiser et al., 2021; Li et al., 2020). Research has begun to fill this gap, but more work needs to be done to understand persistent, platform-specific challenges, though recommendations for action abound: enhancing surveillance of misinformation; removing sources, as well as information; stepping up platform self-regulation; and engaging lawmakers, activists, and others in policy interventions (see, for example, Chou et al., 2020; Rutschman, 2020).

The core takeaway of this review is that research on vaccine hesitancy in online spaces would benefit from the continued and strengthened participation of disciplines that can offer a range of research approaches to online communication dynamics, including but not limited to anthropology, media and communications, human-computer interaction, information science, sociology, STS, and political science. Such participation would harness the strengths of these disciplines in research on specific practices, sociotechnical affordances, and structural factors—such as media policymaking, platform and media economics, and socioeconomic variables—that play roles in addressing and adequately responding to vaccine hesitancy and related misinformation in online and offline spaces during the present pandemic and future health crises. After presenting our findings, we suggest and elaborate five directions for future research.

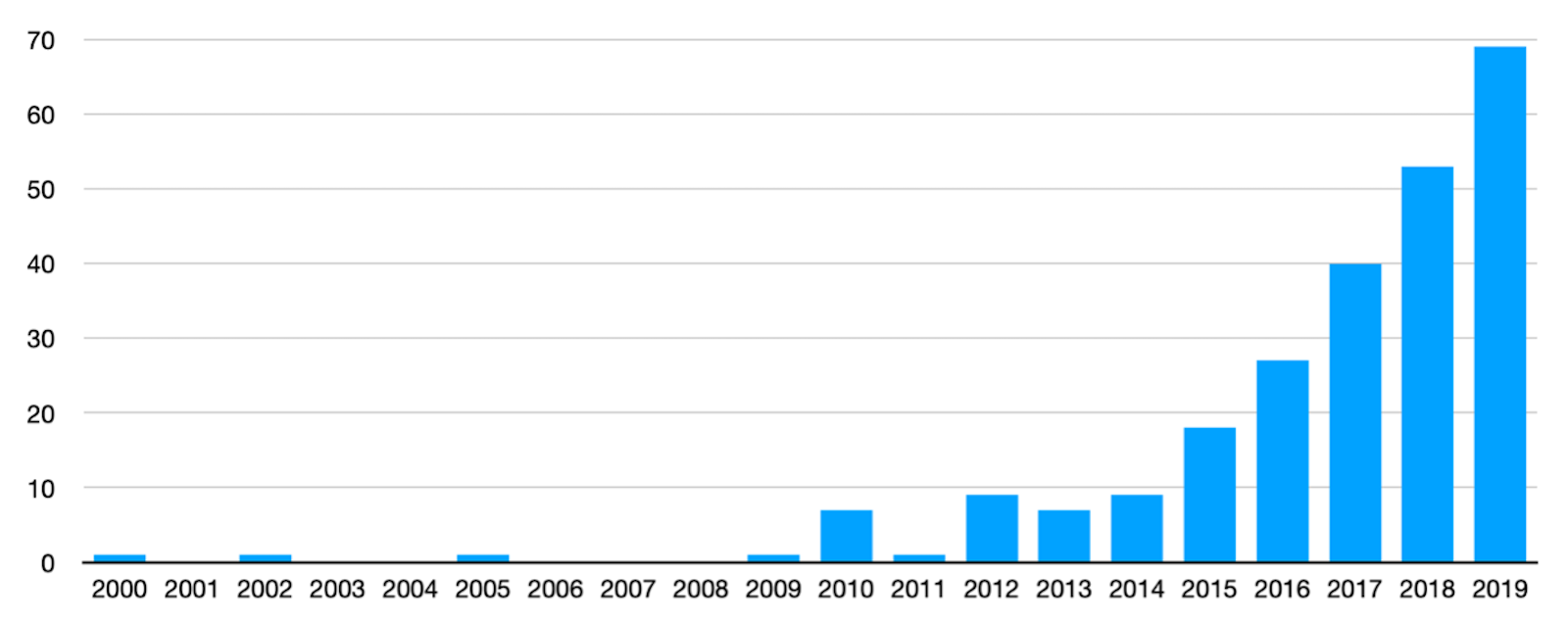

Finding 1: Research on vaccine hesitancy is a rapidly growing field.

Our search of the Web of Science database surfaced 252 articles researching aspects of vaccine hesitancy that referenced online spaces, the earliest of which was published in 2000. We note that the publication rate begins to climb in 2010, rising to 69 articles in 2019. 3 A search using the same terms on April 17, 2021, showed that 182 articles were published between 2020 and early 2021, more than double the pace of publications in 2019. The rise to prominence of social media platforms Facebook and Twitter (both launched to the general public in 2006) coincides with this increased research interest in online spaces.

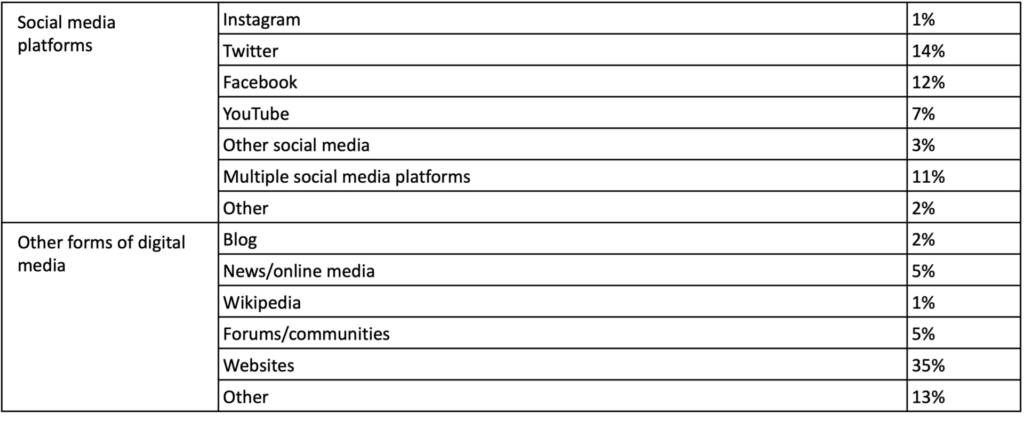

Of 236 articles selected for analysis (see Methods), 100 were determined relevant to our research interest as primarily focused on vaccine hesitancy in online spaces. Table 1 breaks down these 100 articles by digital platform analyzed.

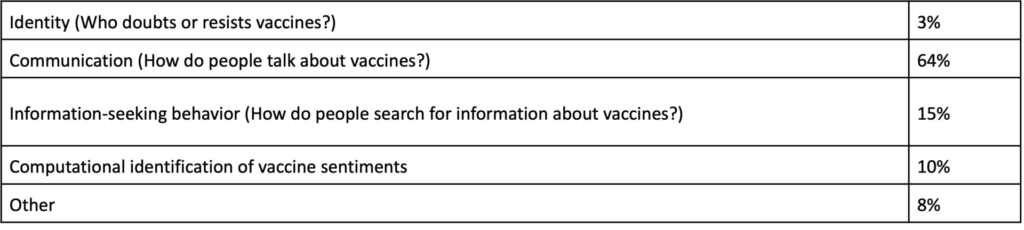

Finding 2: Research is dominated by public health field, with a focus on how people talk about vaccines.

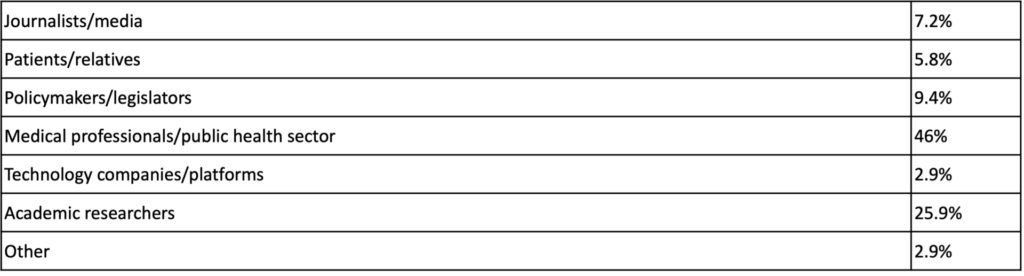

The majority of these articles appear in academic journals focusing on public health and medicine (76 percent). Few articles make causal inferences (9 percent). Table 2 shows the research focus 5 Intercoder reliability testing resulted in low coder agreement for “research focus” and “stakeholders” variables; see Methods. of the articles, which most often demonstrates interest in how people in online spaces talk about vaccines and vaccinations.

Table 3 shows the main stakeholders (n = 139) in the articles. Researchers most often indicate that their studies have conclusions relevant to medical professionals and the public health sector. These conclusions often focus on steps medical practitioners should take to counter misinformation about vaccines.

The majority of stakeholders identified in articles published by public health journals are medical professionals (51 percent; n = 110), with academic researchers comprising 22 percent of stakeholders in these articles. In journals from other fields, academic researchers are identified as stakeholders 41 percent of the time, while medical professionals are identified as stakeholders only 28 percent of the time (n = 29).

Finding 3: Additional gaps include demographic groups, terminology, geography, and disease- or vaccine-specific research.

Very few articles include a focus on gender (11 percent), ethnicity (4 percent), or age (7 percent). When authors focus on gender, they usually study women’s communication around vaccinations (e.g., in the context of Facebook groups). More research focused on these demographics and others would aid efforts to develop more relevant response approaches tailored to different social contexts.

We also note a wide variance in the terminology used for people who are doubtful of or otherwise resistant to vaccines. “Anti-vaccine” or “anti-vaccination” is the most common term found in these articles (55 percent), followed by “vaccine hesitancy” (25 percent) and “vaccine critical” (7 percent). Authors occasionally use the terms interchangeably although they represent different concepts: “Vaccine hesitancy” reflects individuals or communities who may experience challenges related to confidence, complacency, or knowledge and awareness, while “anti-vaccination” reflects active opposition to vaccines. A preferable framework involves terminology broader than these categorizations but not often used in social media contexts: the spectrum of “vaccine confidence” (Larson, 2020).

Seventy-eight percent of the time, countries listed by Web of Science as the origin for the 252 articles originally returned by our search are located in North America or Western Europe (254 out of 325 instances). 6 Web of Science uses addresses of author institutions to populate a “countries/regions” field used in our assessment.

Finally, 35 percent of the articles relevant for our review (n = 100) focus on a specific vaccine or disease, with the most prominent diseases being the human papillomavirus (HPV) and the vaccine for mumps, measles, and rubella (MMR).

Directions for research

This scoping review suggests multiple directions for research to address online vaccine hesitancy and related vaccine misinformation. At a minimum, future reviews should examine how the present pandemic has changed the state of this research. In addition, we suggest the following directions for research.

- Broadening the scope . One direction of research that would address multiple gaps in the present literature is interdisciplinary comparative research on online vaccine hesitancy across national, regional, local, and cultural contexts. Not only would such research help close gaps in our understanding of how vaccine hesitancy in online spaces differs from one vaccine and disease to another, but it also would provide opportunities for new research beyond Western contexts. Such research, well established in political science and media and cultural studies, also is capable of denaturalizing structural influences, such as economic, political, and media system dynamics, that encourage and amplify the online sharing of misinformation. Our review has noted that the extant research has over the years begun to engage more with the online sources of information rather than the quality of the information itself; interdisciplinary, comparative research is capable of bringing into view an additional set of structural sources or influences that can be addressed through policy interventions.

- Methods . The existing research would be enhanced by qualitative, ethnographic fieldwork. Our review shows that information sharing behaviors rather than the identities of those who share information, including social milieus important to those identities, have been the most prominent focus of research. Researchers have used surveys to gather views on vaccines, but ethnographic fieldwork is capable of enhancing our understanding of how vaccine hesitancy relates, on a day-to-day basis, to a variety of social factors and how these factors relate to the online sharing of vaccine information. This fine-grained, nuanced fieldwork could inform intervention strategies that complement or even move beyond the prominent debate in the extant research over the effectiveness of facts vs. stories in encouraging vaccine uptake.

- Different communities . More research is needed on the different communities that exist within every society and that differ with regard to their vulnerability to vaccine misinformation, as well as where and how they encounter it. Investigations into the role of gender, race, religious/spiritual beliefs and political ideology could highlight different online information pathways. These communities are not necessarily clearly delineated from one another but overlap; understanding these intersections is important when it comes to effective communication and outreach.

- Longitudinal research . Most studies in our review that analyzed social media focused on a certain point in time or excluded time from their analyses. Longitudinal research is needed in order to highlight changes over time, identify patterns and discursive moments, and assess the impact of platform actions such as de-platforming bad actors.

- Access and data. The gaps that our review finds in research on certain types of social media, research over time, and research on platform specific-interventions point to the broader, persistent issue of constraints on researcher access to online spaces and the challenges posed by frequently changing data formats and algorithms. These issues – so ubiquitous that they risk becoming invisible and uncritically accepted – often are left unsaid in research; by cataloging how researchers have encountered and addressed them, future literature reviews could contribute to the development of better research strategies and methods.

For our scoping review of the academic literature, we follow procedures outlined by Moher et al. (2009): identify relevant articles in a database; check these articles against other sources; screen out duplicates; assess articles for eligibility; and include the final list in the meta-assessment. Figure 2 shows our process as a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart (Page et al., 2021).

Through discussion, experimentation, and comparison with different libraries of articles, we developed a string of search terms that surfaced a list of articles roughly commensurate with articles found in other databases. This search string operationalizes the concept of vaccine hesitancy by including terms related to research on the lower end of the spectrum of vaccine confidence, such as “refusal,” “denial,” and “skepticism:”

((“anti-vaccination” OR “anti-vaccine” OR “anti-vax” OR “vaccine hesitancy” OR “vaccine reluctance” OR “vaccine refusal” OR “anti-vaxxer” OR “anti-vaxx” OR “vaccine denial” OR “vaccine skepticism” OR “vaccine critical”) AND (“internet” OR “online” OR “social network analysis” OR “social network sites” OR “social media” OR “social networking” OR “Web 2.0” OR “websites”))

We chose the Web of Science Core Collection database for our scoping review due to its widely recognized quality, providing some assurance that the articles included in our review are well-researched and impactful. 7 Web of Science developed the “impact factor” commonly used to assess the academic influence of journals (Garfield, 1994). However, the Scopus database also is prominent in literature reviews. As there are differences in coverage (Martín-Martín et al., 2021; Visser et al., 2021), we compared search results between the two databases and found 20 additional items indexed by Scopus from 2000 to the end of 2019 (roughly corresponding to our Web of Science search’s time period) relevant to our study, three of which could not be accessed. A content analysis of these items found nothing that would significantly alter our findings, though we note a higher prevalence of articles from the field of computer science – most published in conference and workshop proceedings – among the additional Scopus articles (7 of 17 items) than among our relevant Web of Science articles (5 of 100 items).

Using our search string in Web of Science’s title, abstract, and keywords field surfaced 252 articles on Feb. 12, 2020, approximately one month prior to the beginning of widespread COVID-19 precautions in the United States. After removing from this list inaccessible articles and articles not written in English, our final list for analysis included 236 articles. The full text of each of these articles was screened for inclusion in our findings.

Our codebook includes 24 variables, 11 of which require manual coding. Intercoder reliability testing involved 10 coders. Due to the difficulty of achieving high levels of agreement with such a large number of coders, a subset of three coders developed a shared codesheet for a 10 percent subsample of the articles. The other seven coders coded each of these articles separately, without access to the shared codesheet, and checked their coding against it, making changes when they agreed with the shared codesheet.

Final intercoder agreement (Holsti’s) exceeded 0.75 for most variables, except for “stakeholders” (0.51 and 0.64 for two categorical variables sharing the same set of categories, as multiple stakeholders were allowed, coded in order of appearance in each article); and “research focus” (0.6). Coding for multiple stakeholders was complicated by requiring coders to enter codes in the order in which stakeholders appeared in each article; this complication does not affect the coders’ ability to categorize stakeholders, and so we believe reliability for the stakeholders variable is higher than indicated. With regard to research focus, although articles focusing on how people talk about vaccines (communication) clearly dominated our corpus of research articles, at times coders found that some of these articles aimed to shed light on who these people are (identity) or primarily were about computational methods used to study them. We include findings for these two variables in our article, with the caution that intercoder reliability fell short of high confidence for them.

After intercoder reliability testing concluded, we randomly distributed the remaining 90 percent of the articles to our coders for final coding. We used SPSS software to generate descriptive statistics from the results of this coding.

- / Public Health

Cite this Essay

Neff, T., Kaiser, J., Pasquetto, I., Jemielniak, D., Dimitrakopoulou, D., Grayson, S., Gyenes, N., Ricaurte, P., Ruiz-Soler, J., & Zhang, A. (2021). Vaccine hesitancy in online spaces: A scoping review of the research literature, 2000-2020. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review . https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-82

Bibliography

Berman, J. M. (2020). Anti-vaxxers: How to challenge a misinformed movement . MIT Press.

Burki, T. (2020). The online anti-vaccine movement in the age of COVID-19. The Lancet Digital Health, 2 (10), e504-e505. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30227-2

Chou, W. S., & Gaysynsky, A., & Cappella, J. N. (2020). Where we go from here: Health misinformation on social media. American Journal of Public Health, 110 (S3), S273–S275. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305905

Cinelli, M., Quattrociocchi, W., Galeazzi, A., Valensise, C. M., Brugnoli, E., Schmidt, A. L., Zola, P., Zollo, F., & Scala, A. (2020). The COVID-19 social media infodemic. Nature Scientific Reports , 10 , 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73510-5

de Figueiredo, A., Simas, C., Karafillakis, E., Paterson, P., & Larson, H. J. (2020). Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: A large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet, 396 (10255), 898–908. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31558-0

Garfield, E. (1994). The Clarivate Analytics impact factor. Clarivate. https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/essays/impact-factor/

Kaiser, J., Rauchfleisch, A., & Córdova, Y. (2021). Fighting Zika with honey: An analysis of YouTube’s video recommendations on Brazilian YouTube. International Journal of Communication, 15 , 1244–1262. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/14802

Larson, H. J. (2020). Stuck: How vaccine rumours start – and why they don’t go away. Oxford University Press.

Li, H. O., Bailey, A., Huynh, D., & Chan, J. (2020). YouTube as a source of information on COVID-19: A pandemic of misinformation? BMJ Global Health , 5 (5), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002604

MacDonald, N. E., & the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine, 33 (34), 4161–4164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036

Martín-Martín, A., Thelwall, M., Orduna-Malea, E., & López-Cózar, E. D. (2021). Google Scholar, Microsoft Academic, Scopus, Dimensions, Web of Science, and OpenCitations’ COCI: A multidisciplinary comparison of coverage via citations. Scientometrics , 126 , 871–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03690-4

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine, 6 (7), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18 (143), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Orenstein, W. A., Gellin, B. G., Beigi, R. H., Despres, S., Lynfield, R., Maldonado, Y., Mouton, C., Rawlins, W., Rothholz, M. C., Smith, N., Thompson, K., Torres, C., Kasisomayajula, V., & Hosbach, P. (2015). Assessing the state of vaccine confidence in the United States: Recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Public Health Reports, 150 (6), 573–595. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491513000606

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffman, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., Stewart, L. A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A. C., Welch, V. A., Whiting, P., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372 (71), 1–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Rutschman, A. S. (2020). Facebook’s latest attempt to address vaccine misinformation – and why it’s not enough (Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2020-35). Health Affairs Blog, Saint Louis University. https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/faculty/544/

Visser, M., van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2021). Large-scale comparison of bibliographic data sources: Scopus, Web of Science, Dimensions, Crossref, and Microsoft Academic. Quantitative Science Studies, 2 (1), 20–41. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00112

Dariusz Jemielniak’s work on this project was possible thanks to a grant No. OSPOSTRATEG-II/0007/2020-00 from Polish National Center for Research and Development.

Javier Ruiz-Soler’s work was supported by funding from the Canada 150 Research Chairs Program and the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Dimitra Dimitrakopoulou received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 844167.

Siobhan Grayson’s contributions were made possible thanks to an Irish-U.S. Fulbright scholarship awarded by the Fulbright Commission.

Competing Interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

The authors have no ethics approvals to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/MACUIS

Acknowledgements

This project emerged from the Misinformation Working Group at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, Harvard University. This article also greatly benefited from our reviewers’ insightful comments and suggestions.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Public Health

COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the United States: A Systematic Review

Farah yasmin.

1 Department of Internal Medicine, Dow University of Health Sciences, Karachi, Pakistan

Hala Najeeb

Abdul moeed, unaiza naeem, muhammad sohaib asghar.

2 Department of Internal Medicine, Dow University Ojha Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan

Najeeb Ullah Chughtai

3 Department of General Surgery, Liaquat National Hospital and Medical College, Karachi, Pakistan

Zohaib Yousaf

4 Department of Internal Medicine, Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar

Binyam Tariku Seboka

5 Department of Public Health, Dilla University, Dilla, Ethiopia

Irfan Ullah

6 Department of Community Medicine, Kabir Medical College, Peshawar, Pakistan

Chung-Ying Lin

7 Institute of Allied Health Sciences, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan

Amir H. Pakpour

8 Department of Nursing, School of Health and Welfare, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden

Associated Data

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material , further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Vaccine hesitancy in the US throughout the pandemic has revealed inconsistent results. This systematic review has compared COVID-19 vaccine uptake across US and investigated predictors of vaccine hesitancy and acceptance across different groups. A search of PUBMED database was conducted till 17th July, 2021. Articles that met the inclusion criteria were screened and 65 studies were selected for a quantitative analysis. The overall vaccine acceptance rate ranged from 12 to 91.4%, the willingness of studies using the 10-point scale ranged from 3.58 to 5.12. Increased unwillingness toward COVID-19 vaccine and Black/African Americans were found to be correlated. Sex, race, age, education level, and income status were identified as determining factors of having a low or high COVID-19 vaccine uptake. A change in vaccine acceptance in the US population was observed in two studies, an increase of 10.8 and 7.4%, respectively, between 2020 and 2021. Our results confirm that hesitancy exists in the US population, highest in Black/African Americans, pregnant or breastfeeding women, and low in the male sex. It is imperative for regulatory bodies to acknowledge these statistics and consequently, exert efforts to mitigate the burden of unvaccinated individuals and revise vaccine delivery plans, according to different vulnerable subgroups, across the country.

Introduction

Vaccines are critical in lowering disease-specific mortality rates ( 1 ) and the long-standing control of the COVID-19 pandemic is pivoted upon the development and uptake of the vaccine ( 2 ). Vaccines currently recommended and authorized in the US are BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech), mRNA-1273 (Moderna), Johnson & Johnson/Janssen ( 3 ) with the challenge now shifting from finding an effective cure to ensuring its implementation ( 4 ).

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention acclaims vaccination as one of the leading success stories of public health in the twentieth century ( 1 ) and a similar feat is now being aimed for the novel coronavirus. As part of Operation Warp Speed, the US administration alongside manufacturers and developers exerted efforts and by January 2021, hoped to deliver 300 million doses of a safe and effective vaccine for COVID-19 ( 5 ). By mid-January 2021, there were around 13 million persons who had COVID-19 vaccine initiated in the US ( 6 ) and while these numbers were promising, the vaccination process has been met with an undesirable, although not unusual, phenomenon well-known as “vaccine hesitancy.” Defined by the World Health Organization as “the delay in the acceptance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccine services” ( 7 ), the term vaccine “hesitant” is preferred over “pro” and “anti” vaccination to avoid polarization and, as it insinuates that the minds can be persuaded toward acceptance ( 8 ).

Since the inception of vaccines in medical practice in the 1800s ( 9 ), the public has not always concurred to getting vaccinated albeit many people have complied in face of apparent death and indisposition ( 1 ). Frequent outbreak of vaccine-preventable diseases in the US, such as 1,282 confirmed cases of measles in the United States in 2019 ( 8 ), can be ascribed to reduced vaccination and hence vaccine hesitancy, the latter ranked by the WHO as the top threat to global health in 2019 ( 1 ).

According to a global study, 72% of people would take the COVID-19 vaccine if deemed safe and effective, but willingness varies between countries ( 10 ). When studied under the framework of the 5C model of psychological antecedents that drive vaccine acceptance: confidence, constraints, complacency, calculation, and collective responsibility, the US population indicated 54% vaccine acceptance, a value that divulges vaccine skepticism ( 11 ). The US population has demonstrated inconsistent results over the period as between April 1–14 and November 25–December 8, 2020, the percentage who stated they were somewhat or very likely to get vaccinated declined from 74 to 56% ( 12 ). The percentage of US adults intending to get vaccinated has seen a u-shaped pattern with results showing changes between September and December 2020, which correspond to pre-authorization and post-authorization dates in the US, respectively ( 7 ). Conversely, another national representative survey revealed the vaccine hesitancy to have a longitudinal decline of 10.8% points between October 2020 and March 2021 ( 13 ).

COVID-19 vaccine receptivity in the US has varied between states and subgroups. In mid-October 2020, acceptance rates ranged from 38% in the Northeast to 49% in the West ( 14 ). Vaccine hesitancy in the general population has been correlated with certain factors including gender, age, race, socioeconomic status, education level, and US-based surveys disclose important findings. Women have lower intentions than men to be vaccinated ( 14 ) and as of a study from April to December 2020, the self-reported likelihood of getting COVID-19 vaccination was lower among females than males (51 vs. 62%) ( 12 ).

The cohort comprising of vaccine-hesitant individuals can be large enough to diminish the COVID-19 vaccine's potential to provide population immunity ( 15 ). Impediments to vaccination involve concerns including fear of side effects, inadequate information, short duration of immunity ( 14 ) forgoing vaccination due to lack of insurance or financial resources ( 16 ). Safety and effectiveness of the vaccine are the most pivotal detriments of hesitancy ( 4 ) while for some, especially marginalized factions, dissatisfaction with the health system owing to past experiences of discrimination, systematic racism deters them from vaccination ( 17 ).

Vaccine hesitancy is not a singular problem but attributed to various underlying causes that differ across time and communities ( 1 ). Recent results have shown somewhat reduced hesitancy, corresponding to the dates of vaccine approval and mass roll-out ( 13 ) and it is speculated that as the pandemic becomes more “real” to the Americans, vaccine acceptance can improve. Being one of the representative countries hardest hit by COVID-19, estimating vaccine hesitancy in the U.S could be important for future vaccine promotion and herd immunity ( 18 ). This systematic review aims to broaden the scope of discussion by studying factors coupled with vaccine hesitancy in the US population and the study's findings will be beneficial not only for COVID-19 vaccination coverage but also improving the existing healthcare system's preparedness for routine and emergency vaccination. Furthermore, our results will be imperative in helping strategize policies for tackling antagonism and for developing a thorough vaccine delivery plan.

The review was performed following PRISMA guidelines. Papers published in MEDLINE (PubMed), Cochrane library, and Google Scholar assessing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy/vaccine uptake/ vaccine acceptance in the English language were eligible for inclusion in the review. The inclusion criteria were: (1) peer-reviewed published articles indexed in PubMed; (2) survey studies among the general population, healthcare workers, minority and religious communities, students, or patients (3) the major aim of the study was to evaluate COVID-19 vaccine acceptance/uptake/hesitancy in the US population only and (4) publication language was English. The exclusion criteria were: (1) the article did not aim to evaluate COVID-19 vaccine acceptance/hesitancy/uptake in the US population; (2) publication language was not English.

A search was carried out till 17th July 2021 using the following search strategy: (COVID * vaccine * hesitancy [Title/Abstract]) OR (COVID * vaccine acceptance [Title/Abstract])) OR (COVID * vaccine * hesitancy [Title/Abstract])) OR (COVID * intention to vaccinate * [Title/Abstract]) OR (COVID vaccine * accept * [Title/Abstract]).

Articles were screened by abstracts and titles. Studies shortlisted were cohort studies and cross-sectional studies that assessed COVID-19 vaccine acceptance over a certain time period, specific for each study, respectively. Studies drew comparison between vaccine acceptance and vaccine hesitance in the population surveyed. After selection, data extraction for the following items was conducted: title and date of the study, study period/duration, the target population of the study (e.g., general public, students, healthcare workers, patients, religious groups, and minority groups), region of US where the study took place, population characteristics i.e., sample size, % female, mean age, % Whites, the definition of vaccine acceptance in the study, overall acceptance rate, acceptance rate by education level, factors relating to vaccine acceptance, and factors relating to vaccine hesitancy. Overall vaccine acceptance (%) was taken from each study as deduced, corresponding to the definition of vaccine acceptance presented in the study. A forest plot was also constructed using Microsoft Excel version 2018 to demonstrate the overall prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the United States.

The search string provided in the Supplementary Material retrieved 784 records, of which 65 were included in the quantitative synthesis of observational studies on vaccine acceptance in the United States (US). Figure 1 illustrates the four-step selection process as per the PRISMA guidelines ( 19 ).

PRISMA guidelines flow chart.

Characteristics of the Literature

The sample size of the selected studies ranged from 25 to 73,650, with a total of 3,13,998 individuals. Out of the 65 studies (67 surveys), 31 of them reported the study region, of which nine were conducted in New York City (NYC). Of the 50 studies reporting female sex %, 38 of them had a percentage >50. Acceptance was measured as somewhat likely, extremely likely, and willingness to take the vaccine. The majority of the surveys that reported race and ethnicity, had a predominant non-Hispanic white population. Vaccine acceptance was presented as percentages in 61 studies, whereas the remaining four studies reported means. Four of the studies used a point scale system to measure the likelihood of receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. Silva et al. ( 20 ) made use of a 10-point scale ranging from 1- extremely unlikely and 10- extremely likely, whereas Meier et al. ( 21 ), Rhodes et al. ( 22 ), and Dorman et al. ( 7 ) used a 7-point scale. Detailed studies characteristics are present in Table 1 .

Characteristics of the literature.

COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Rates

Vaccine acceptance rates varied from a low of 12% to a high of 91.4%. In 48 from 63 surveys, readiness to get vaccinated was ≥50%. The mean and standard deviation of acceptance rate by Silva et al. was 7 (3.12); meanwhile, the willingness of studies using the 10-point scale ranged from 3.58 to 5.12.

COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Stratified per Region

A total of 32 studies included the geographical location of the survey, comprising data of 20 states out of a possible 50. Overall, a low of 12% was observed in New York City in the Orthodox Jewish community, whereas a high of 90.1% was reported in Kansas among employees and students at the University of Kansas Medical Centre. Figure 2 illustrates the geographical average COVID-19 vaccine acceptance percentage reported in each state. Classifying vaccine acceptance per the four regions in the United States shows New England division of Northeast, West North Central of Midwest, Mountain division of West, and the whole of the South, except West South Central, had a low percentage of states with vaccine acceptance figures, however, in the Mid Atlantic division of Northeast, all three states had surveys conducted, making it the only division with 100 percent data availability. Supplementary Table 1 states the percentage acceptance by each state, with Kansas reporting a high of 89.6%.

COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rates of United States.

COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Stratified per Respondents' Population

Apart from the studies with the general population, 18 surveys took place in a healthcare setting, including patients, workers and, students. From these 18, eight highlighted patients' attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine. Amongst patients, two surveys on solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients showed their hesitance toward the vaccine owing to lack of data and concerns of its safety in transplant recipients (56.10 and 31.63% acceptance). Other than SOT recipients, studies report willingness in patients with chronic disease, multiple sclerosis, dialysis, and cancer which showed a positive response toward the COVID-19 vaccine. Of these, patients suffering from chronic disease reported the highest acceptance rate of 85%. Healthcare workers and students (dental and medical) showed a varying attitude toward the vaccine as acceptance ranged from a low of 45% in nursing home staff to a high of 90.10% in staff and students at the University of Kansas Medical Centre.

Three surveys were carried out in religious communities, two in Jewish and one in the Amish community. The Amish community had an alarmingly low acceptance rate of 25%, whereas the Jewish people had 12 and 65.3%, with the latter being of greater significance due to the large sample size. Two surveys carried out in New York highlighted the increased hesitance toward the vaccine by pregnant women. Amongst pregnant women, an acceptance rate of 44.3 and 58.35% was reported, whereas 76.2% of non-pregnant women were inclined to take up the COVID-19 vaccine. Studies on vaccine acceptance in inmates and those discharged from prison found a 20, 44.9, and, 66.5% acceptance rate in women recently released from prison, inmates from four states, and a California state prison, respectively, with the latter being significant with a sample size of 97,779. Furthermore, a survey on tobacco and marijuana users showed a low vaccine uptake rate of 49.1%. In all four of these studies, Blacks/African Americans were correlated with increased unwillingness toward the COVID-19 vaccine. Figure 3 summarizes the percentage of vaccine acceptance in different population groups. Figure 4 demonstrates the pooled prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the United States with the pooled prevalence being 71.42%.

COVID-19 vaccine acceptance stratified per-respondents' population.

Pooled prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the United States.

Factors Associated With Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitance

Several factors were identified as leading to low or high vaccine acceptance. From the 65 studies, sex was mentioned in 22 surveys, race in 31, age in 16, education level in 19, and income status in 4. The male sex and individuals with a college degree or higher education were significantly associated with higher vaccine acceptance rates in all surveys reporting these variables. Furthermore, non-Hispanic Blacks were correlated with having the lowest vaccine acceptance in all 31 surveys whereas Whites and Asians showed a positive attitude toward uptake of the COVID-19 vaccination. People aged >45 years were linked with an increased approval of the vaccine compared to the younger population in 15 out of the 16 surveys. Respondents from lower-income backgrounds were less inclined to get vaccinated in all four studies. Apart from these significant predictors of behavior toward a vaccine, other factors that contributed to vaccine hesitancy included uncertainty about the vaccine safety and side effects entailing after its administration, religious reasons, and a lack of trust in the healthcare system. A comprehensive data evaluation of the studies is included in Table 1 .

Changes in COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Over Time

Two studies investigated the change in acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine by surveying the population twice. Daly et al. conducted the first round of the survey in October 2020, followed by the second one in March 2021. Percentage acceptance rose by 10.8% from 54 to 64.8%. Furthermore, Szilagyi et al. carried out their surveys in November-December 2020 and April 2021 with 56.2 and 74.1% accepting the vaccine, respectively, marking a rise of 7.9%. However, an overall change in readiness for uptake of the vaccine was notable; the predictors of hesitance remained the same throughout time. African/American Blacks and females were the leading predictors of low acceptance in both studies. Daly et al. also correlated younger age and lower-income with the increased unwillingness of the COVID-19 vaccine.

The emergence of the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant has put the United States on the forefront in the total number of COVID-19 cases countrywide ( 76 ). Studies have shown that a two-dose regime of any available vaccine significantly reduces a poor prognosis of COVID-19 ( 77 ). The rapid advent of efficacious vaccines for coronavirus is a projection of leaps in the field of medicine toward the goal of herd immunity. This, however, is threatened by the globally persistent but a re-emerging phenomenon of vaccine hesitancy and anti-vaccination, as experienced for vaccine-preventable diseases such as poliovirus and rubella. Despite a population of 59.9% receiving at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine ( 78 ), analyzing vaccine hesitancy is imperative to strategize vaccine delivery plans to procure maximum vaccine coverage and limit the spread of pathogens to the immunocompromised individuals and children who cannot be vaccinated.

In this systematic review, predictors of vaccine hesitancy and acceptance are studied across the U.S in the general population, pregnant women, immunocompromised individuals, students, healthcare workers, racial groups, and demographic characteristics. Factors associated with vaccine hesitancy are vastly different before and after the availability of vaccines. Before the roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines in mid-December 2020, major concerns across all the population groups were focused on the safety, effectiveness, and cost of the vaccine ( 38 , 63 ). As the death toll peaked in the US, and with more publicly available data of vaccine trials, there was a considerable trend shift in the attitudes toward receiving a vaccination ( 33 ).

Thirty-three studies from a pool of 62 gathered vaccine acceptance rates from the general population, ranging from 91.4% ( 52 ) to a surprising low of 4.6% ( 7 ). Besides the difference in the timeline of each study, hesitancy was mainly driven by the lack of education and understanding of the process of vaccine development. As pharmaceutical companies develop multiple vaccines for the emerging strains, the expedited process of approval has raised concerns about its effectiveness ( 52 ), explaining their preferred choice of mRNA vaccines as opposed to any available vaccines ( 18 ).

Eleven studies report ethical and racial groups' unwillingness which stems from the deep-seated mistrust in the healthcare system. A study by Willis et al. conducted between July and August 2020 showed that one in every four Blacks/African Americans and Hispanics were hesitant to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, while COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was highest among Black/African American respondents (50.00%), followed by Hispanic/Latinx respondents (19.18%), and White respondents (18.37%) ( 15 ). An online survey from March 2021 revealed a significant decline in vaccine hesitancy amongst the Black race ( 14 ). Black/African Americans have been reported to consistently depict suspicion toward the vaccine, with similar patterns observed previously with the influenza vaccines. These can be traced back to the Tuskegee Syphilis study which mishandled hundreds of Black individuals and has institutionalized racial discrimination since then ( 34 , 79 ). Consistent with the findings of observational studies, Blacks/African American race were more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 than White Americans race; if contracted, the percentage of hospitalization and mortality was significantly higher ( 80 ). A survey that studied COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in sexual and gender minority (SGM) group reported the least willingness in individuals who identified as Black; insensitivity from government representatives toward movements such as Black Lives Matter has deepened racial and economic disparity ( 20 ). Vaccine hesitancy in this minority group can be further explained by the pre-existing disparities with healthcare professionals, unavailability of healthcare services, and underrepresentation in clinical trials ( 7 , 38 , 64 ). Maximum vaccine coverage can be achieved by building trust in the government and medical services; Black/African Americans and Hispanic healthcare workers can contribute to foster trust in the system. As many belong to the low-income strata, health insurance can help recover the losses. Providing maximum transparency in COVID-19 trials through informed consent, ensuring maximum representation, and consistent access to healthcare during and after the pandemic is likely to improve turnout at vaccination centers. Entrusting distribution and vaccine manufacturing to businesses owned by Blacks will be a step toward positive vaccine trends. However, Blacks and Hispanics can only be freed from centuries of structural racism and classism in fields outside of medicine through consistent cultural policies across the US ( 34 , 64 , 79 ).

Two studies report COVID-19 vaccine acceptance percentages in religious minorities in the US; an average willingness of 25% in Amish families of the Holmes County in Ohio ( 56 ) and 12% in Jewish Orthodox individuals in NY ( 30 ). Previous studies have shown that outbreaks of measles, rubella, and poliovirus have significantly affected the Amish community in Ohio, reflecting their lack of concern regarding the severity of the disease ( 81 ). Similar to findings of previous surveys conducted for Amish families, concerns about the adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccines were recognized as a major factor for vaccine hesitancy. Other predictors of unwillingness included avoiding dependence on the government, while some conservative families were not convinced as the bishop did not levy importance to it ( 56 , 82 ). Local governments in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana have set up vaccination facilities at health departments to increase turnout ( 30 ). However, an effective approach to spreading COVID-19 vaccine awareness and destigmatizing it in the Amish community will have to be in conjunction with the church leadership, and the Old Order Amish families which were unaffected by the religious doctrine ( 82 ). On the contrary, shared accommodation amongst the Jewish community in NY has increased the incidence of COVID-19, especially in the Chasidish sect. Regardless of the likelihood of contracting coronavirus, negative vaccine trends in Chasidish respondents in Brooklyn were observed ( 83 ). However, factors affecting their vaccination status; the belief that natural immunity was more beneficial, and the mistrust in physicians in the US, among other reasons put them on the priority list of strategizing distribution plans and approaches ( 30 ).

Individuals from ethnic minority groups or persons suffering from substance use disorders or mental illnesses are frequently incarcerated. The lack of stable housing, food supplies, and subpar treatment facilities delay diagnosis, which increases the risk of diseases like COVID-19 ( 68 ). Vaccine acceptance rates were relatively moderately high, ranging from 44 to 66% ( 45 , 68 ) in prisons while 49% in smokers ( 29 ). Consistent with previous surveys, hesitancy in prisoners originated from health illiteracy and the perception that a COVID-19 vaccine was unnecessary ( 68 ). In individuals who have been exposed to marijuana and/or tobacco, low acceptance was governed by demographic characteristics and if they lived alone or with a family of more than 5 people. This could be explained by the notion that living alone meant no exposure to SARS-CoV-2 while living with a larger family meant greater coronavirus exposure, and hence natural immunity ( 29 ). Although California, Washington, and Texas have recognized the importance of vaccinating detained residents and have put them on the priority list, distrust in government facilities revokes any efforts made.

As experienced in the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, a survey administered among reproductive-aged women from January 7, 2021, to January 29, 2021, established non-pregnant respondents to be most likely to accept vaccination, followed by breastfeeding responders with pregnant responders had the lowest vaccine acceptance ( 43 ). The lack of research of COVID-19 vaccines in pregnant women and females has raised major concerns related to its safety to the fetus, with many non-pregnant women considering disruption to the menstrual cycle and infertility a side effect ( 43 ). Future research should be geared toward pregnant and breastfeeding women who make up a large proportion of the population of the US.