Now Reading

TSC Reports THESIS Index Users Represent Almost $1 Trillion in Annual Retail Sales

According to TSC’s 2020 Impact Report, 45 of the top 100 CPG companies performed THESIS assessments in 2019.

- Sustainability

Published 04-30-20

Submitted by The Sustainability Consortium

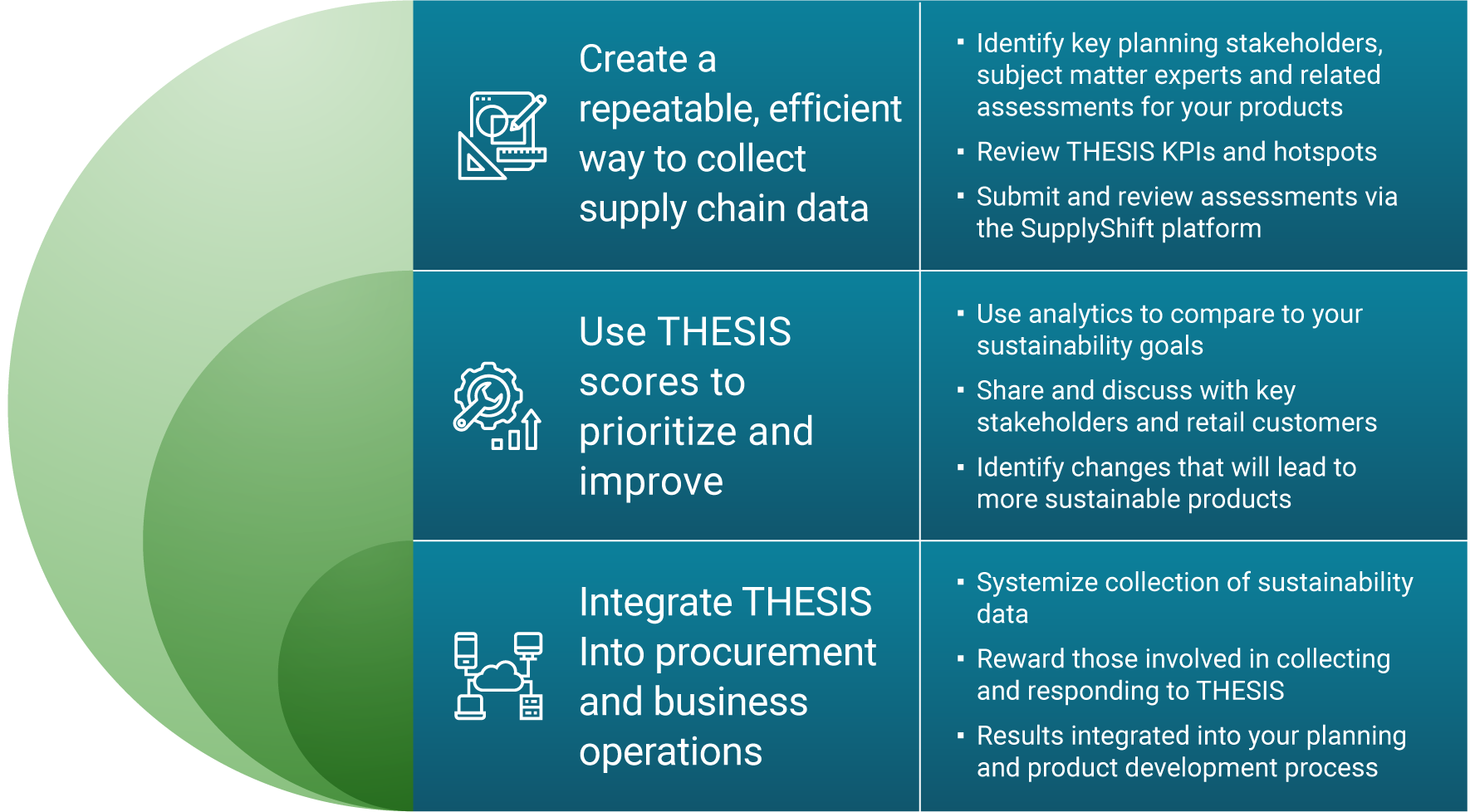

The Sustainability Consortium (TSC) reported today that of the top 100 CPG companies, 45 of these manufacturers performed THESIS assessments in 2019. These companies, plus the over 1,500 suppliers who used THESIS, represent almost $1 trillion in annual sales. The Sustainability Insight System (THESIS), powered by SupplyShift, is the independent, science-based, performance management solution that allows brands and manufacturers to understand the sustainability story of their products, to quickly identify ways to improve, and to communicate that story to retailers, customers, investors and consumers.

The launch of THESIS in 2019 saw the roll-out of a new measurement platform used by retailers and product manufacturers to optimize supply chain transparency. Product manufacturers were able to use new content and functionality to gain insight into their performance and drive improvements of the products they produce.

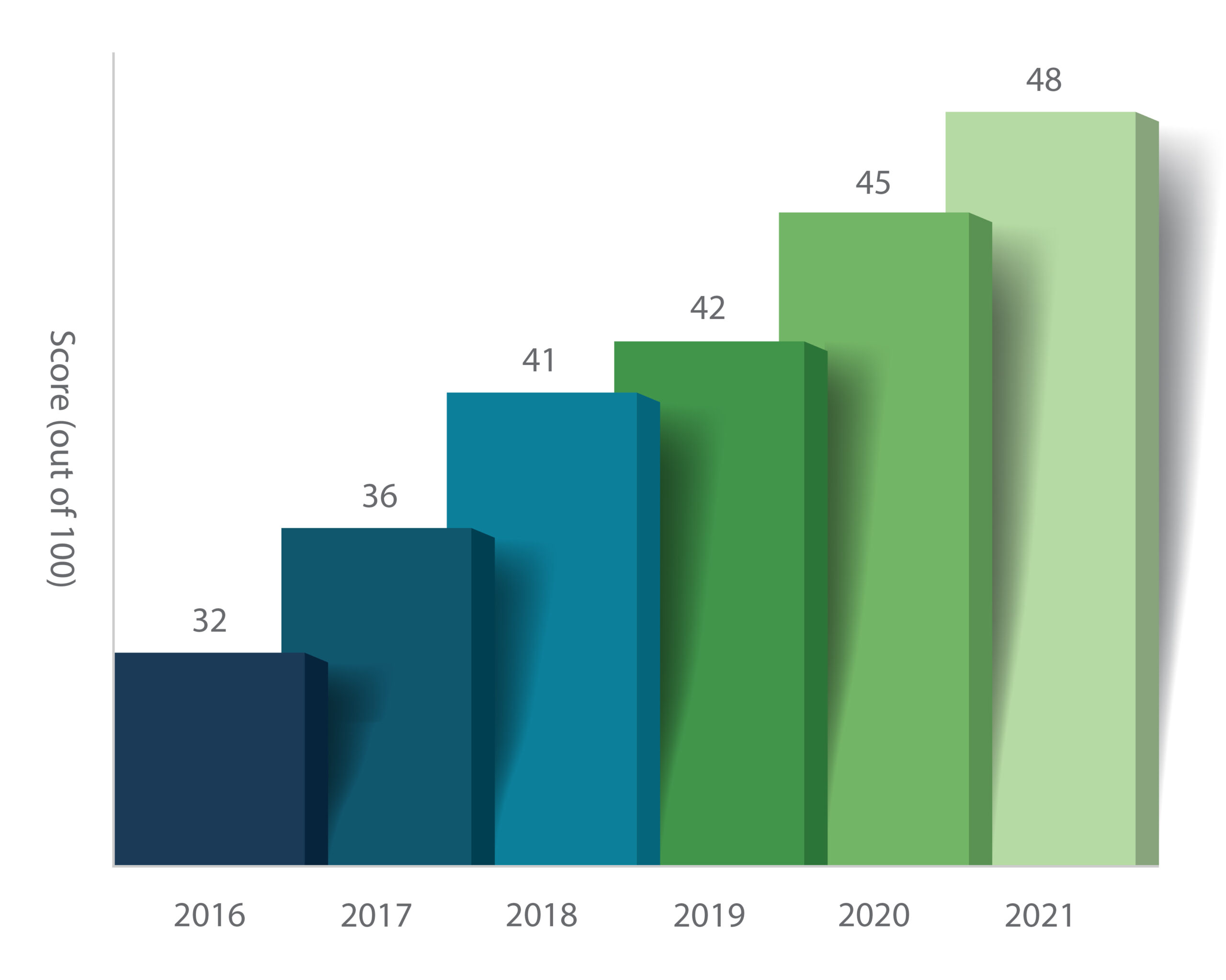

Scores among product manufacturers remained flat from 2018 to 2019 in the first year of the new THESIS index. Scores in the 2019 THESIS Index have improved 23% since baseline year of TSC’s original sustainability index in 2016. Systems and processes put into place by manufacturers over the last several years have led to an improvement in scores, but the unchanging scores from 2018 to 2019 indicate that systemic challenges remain to improve supply chain transparency.

In their 2020 Impact Report, Defining Leadership in Sustainable Supply Chains , TSC details that companies are still struggling with challenges that can include measuring and reporting greenhouse gas emissions, changing to more sustainably sourced or recycled material in product and packaging design, and addressing social responsibility issues like labor rights.

“Gaining transparency into your own operations and your supply chains is an important first step,” says Dr. Kevin Dooley, Chief Scientist of TSC. “Now companies can use THESIS to identify gaps and take steps to change their product, packaging, or processes to become more sustainable. And to get recognition for doing so from their customers.”

Many product categories are featured in TSC’s Impact Report:

Hand tools have doubled THESIS scores since 2016 and performed well on energy efficiency, product design and responsible battery management

Footwear has improved 75% since 2016 and performed well on labor rights, worker health and safety, and protections for homeworkers

In individual assessments, THESIS high scores stand out for:

Activewear for Children, Men and Women scores high on labor rights, worker health and safety, greenhouse gas emissions, water use and wastewater management.

Dishwashing products performed will with high scores in chemical selection, fragrance safety, ingredient disclosure and packaging design.

Overall, plant-based foods scored well because of shorter supply chains and good relationships between buyer and supply chain

Livestock categories had high scores related to similar data already collected for regulatory compliance.

TSC Chief Executive, Euan Murray, states, “This is the year TSC will define sustainability leadership in each category as a part of a multi-year strategy to help brands and manufacturers understand the sustainability story of their products and tell that story to retailers, investors, consumers and NGOs.”

TSC announced in early 2020 that their five year strategy will see THESIS as a tool for retailers and product manufacturers to manage their businesses and communicate with stakeholders, and will see TSC reduce the effort and increase benefits for THESIS users and develop new audiences for results. In addition to THESIS changes, TSC committed to expanding their current Innovation Program to focus on products that translate science and create transparency as well as launch their Leadership Institute, a program to tackle issues collectively and develop the sustainability leaders of tomorrow.

“Walmart encourages suppliers to participate in The Sustainability Consortium’s THESIS Index as part of our efforts to promote sustainability and transparency across our supply chain,” says Jane Ewing, Senior Vice President, Sustainability, Walmart.

TSC is a global organization propelling the consumer goods industry forward to create more sustainability products through science-based assessments and solutions. Their full impact report is available here .

The Sustainability Consortium (TSC) is a global non-profit organization transforming the consumer goods industry to deliver more sustainable consumer products. We work to enable a world where people can lead fulfilled lives in a way that decouples their impacts on people and the planet. Our members and partners include manufacturers, retailers, suppliers, service providers, NGOs, civil society organizations, governmental agencies and academics. TSC convenes our diverse stakeholders to work collaboratively to build science-based decision tools and solutions that address sustainability issues that are materially important throughout a product’s supply chain and lifecycle. TSC also offers a portfolio of services to help drive effective improvement and implementation. Formed in 2009, TSC is jointly administered by Arizona State University and the University of Arkansas and has a European office at Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands. For more information visit www.sustainabilityconsortium.org .

The Sustainability Consortium

The Sustainability Consortium® (TSC®) is a global nonprofit organization working at the intersection of science and business to transform the consumer goods industry to deliver more sustainable products. TSC creates credible, scalable tools, strategies and services that are based in science, informed by stakeholders and focused on impact across the entire lifecycle of consumer products, including environmental, social and economic imperatives. The Sustainability Consortium is comprised of more than 100 members, including manufacturers, retailers, NGOs, civil society and corporations that work collaboratively on innovation for a new generation of products and supply networks. The Sustainability Consortium is jointly administered by Arizona State University and the University of Arkansas, with additional operations at Wageningen UR in the Netherlands and Nanjing University in China.

More from The Sustainability Consortium

Join today and get the latest delivered to your inbox

- Library Home

- General (Summon)

- Books & Media (Catalogue)

- Indexes, Databases & Articles

- Research Guides

- UBC Research

- UBC Open Collections

- UBC Vancouver

- Asian Library

- Biomedical Branch Library

- Chapman Learning Commons Help Desk

- The Chung | Lind Gallery

- David Lam Management Research Library

- Education Library

- Irving K. Barber Learning Centre

- Koerner Library

- Law Library

- Music, Art and Architecture Library

- Rare Books and Special Collections

- Research Commons

- University Archives

- Woodward Library

- X wi7 x wa Library

- UBC Okanagan

- The Commons (Okanagan)

- Okanagan Library

- Special Collections & Archives

- UBC Virtual

- AskAway Chat Services

- Borrowing Services

- My Library Account

- How to Get Library Access

- See More...

- Electronic Access

- Connect to Library Resources

- OpenAthens Login Overview

- Computers & Technology

- Print, Copy, Scan

- Public Computers & Software

- Group & Silent Study Spaces

- Technology Spaces

- Guides for Library Users

- Undergraduate Students

- Faculty & Instructors

- Planning Your Research

- Getting Started on Your Research

- Finding Resources

- Journal Articles

- Evaluating & Citing Sources

- Evaluating Information Sources

- How to Cite

- Publishing Research

- Getting Started with cIRcle

- Building Your Academic Profile

- Collections

- Policies, Procedures and Guidelines

- Work with Us

- Accessing Library Resources?

- OpenAthens Login

- Add Browser Extension for Access

- Managing Your Account?

- My Library Account Login

- Need Citation Management?

- Citation Management Tools

JavaScript is disabled: Site features and functionality may be limited.

- Library Home /

- Search Collections /

- Open Collections /

- Browse Collections /

- UBC Theses and Dissertations /

- Livability and quality of life indexes in planning...

Open Collections

Ubc theses and dissertations, livability and quality of life indexes in planning for sustainable communities lawson, joel --> -->.

This thesis examines issues surrounding the use of Livability and Quality of Life Indicators in a sustainable planning process. Planning literature is rife with references to quality of life and livability, as is other literature dealing with the urban environment. There are numerous existing indexes purporting to measure livability or quality of life, but few do so with any real sense of theoretical rigour or clarity of purpose. An examination of the relevant terms follows, and workable definitions are proposed. An examination of existing indexes highlights many of the potential issues which must be addressed in the development of an index. Finally, a planning framework within which community quality of life and regional livability indexes could be effectively employed will be discussed. Despite the difficulties, there is much potential for the use of quality of life and livability indexes in planning, in terms of both information gathering and equitable information dissemination. Ultimately, however, the true value of an index-centred process might lie in the social learning involved in its development and use.

Item Metadata

- ubc_1992_spring_lawson_joel.pdf -- 4.73MB

Item Citations and Data

Permanent URL: https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0086468

Download Metadata

For non-commercial purposes only, such as research, private study and education. Additional conditions apply, see Terms of Use https://open.library.ubc.ca/terms_of_use.

The Sustainability Consortium at ASU releases 2021 impact report

Science-based thesis tool helps consumer goods companies have a positive impact on the planet.

Many consumers rarely think about where the food and products they buy come from, nor do they understand how harmful the production of these items can be on people and our environment.

In fact, these consumer goods are responsible for 60% of global greenhouse gas emissions, two-thirds of tropical deforestation, 80% of global water use and three-quarters of forced and child labor. That’s a message that Arizona State University’s Sustainability Consortium (TSC) tries to convey to the public in their annual impact report .

This report, released on May 13, shows the work they do is helping consumer goods companies have a positive impact on the planet.

Kevin Dooley

“Our data is showing that our work and engagement with retailers is continuing to make progress on people and the environment,” said Kevin Dooley , TSC’s chief research scientist and a senior sustainability scientist with ASU’s Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation . “We’re not only influencing the big leaders but it’s trickling to the privately owned medium- and small-sized companies that are not usually known for practicing sustainability.”

This year’s report shows that manufacturers' scores have improved 7% from 2019 to 2020 and 38% since 2016.

The scores are based on a TSC-created model called The Sustainability Insight System (THESIS), powered by SupplyShift. THESIS is an independent, science-based performance management solution that allows brands and manufacturers to understand the sustainability story of their products, to quickly identify ways to improve, and to communicate that story to retailers, customers, investors and consumers.

Since 2009, ASU and the University of Arkansas recognized an opportunity for an organization to make it their mission to push consumer products to become more sustainable. It was this common vision the led to the establishment of this groundbreaking organization.

TSC, which counts more than 100 businesses, nonprofits and academic institutions as members, created a science-based system where research insights into nearly 130 product categories are offered to companies. It represents the triple bottom line approach to sustainability that’s not only good for the environment but a way for retailers to work cooperatively with their suppliers and manufacturers to not only make products more sustainable, but to also see into their supply chains very clearly.

Products range anywhere from adhesive tape to toys, root vegetables to refrigerators, cell phones to cherries, and shampoo to stationery.

Manufacturers performing THESIS assessments represent an estimated total of $911 billion in total annual retail sales.

“The breadth and complexity of consumer goods supply chains means there are sustainability impacts left, right and center," said Euan Murray, chief executive of The Sustainability Consortium. "It also means there’s no single solution. So, we have taken the best sustainability science and turned that into the business-friendly THESIS tool.”

Despite a challenging year with the pandemic, Dooley said the companies using TSC’s THESIS index have made significant improvements in greenhouse gas emissions, water use intensity, worker health and safety, and biodiversity in sourcing.

Dooley said consumer attitudes have drastically changed in the last three years; consumers are demanding that manufacturers and retailers adopt new practices and design more environmentally sustainable products.

“Retailers like Walmart, Amazon, Kroger and Walgreens now realize that they need to do this regardless if consumers are interested or not,” Dooley said. “Their reputation is at risk, which in turn means their supply could be at risk. They understand what’s at stake and they are engaged.”

This year’s impact report also disclosed:

- TSC details that some companies are making good progress, especially in textiles and electronics, while several systematic issues remain, like sustainable packaging and deforestation.

- THESIS users, who are made up of suppliers and manufacturers, reported that 45% did not report their sustainability performance publicly, meaning that just about half of companies do not have public sustainability goals, which are in demand by consumers who are researching brands to decide what to purchase (or not purchase).

- 93% of suppliers and manufacturers took actions to improve their products.

- The packaging of products is becoming more sustainable across almost all product categories, meaning that companies are investing not only in packaging that can be recycled, but also in the processes to recycle packaging.

- Companies producing home and personal care products (shampoo, makeup, household cleaners, etc.) are implementing safer ingredients in the formulas of their products – driven by consumer education and demand.

- In electronics, 90% of companies are sourcing minerals from conflict-free smelters.

- Almost all textile and clothing manufacturers were improving rapidly on issues like labor rights and worker health and safety.

Top photo courtesy of iStock/Getty Images.

More Environment and sustainability

ASU sustainability students tackle hotel food waste

Graduating seniors from the School of Sustainability, a unit of the College of Global Futures at Arizona State University, showcased their innovative solutions for real-world sustainability…

Engineering low-carbon building materials

Cement is the strong and versatile binder that holds together sand and aggregates in concrete used to erect the sturdy structures that have long shaped our modern built environments. Cement is also…

Reef restoration program celebrates official opening of state-of-the-art coral reef facility

When the ʻĀkoʻakoʻa reef restoration program was established in 2023, it brought together decades of research, community partnerships and a commitment to healthy coral reefs in West Hawaii. On April…

Advertisement

Financial sustainability: measurement and empirical evidence

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 21 February 2022

- Volume 92 , pages 467–516, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Werner Gleißner 1 , 2 ,

- Thomas Günther ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9860-8668 1 &

- Christian Walkshäusl 3

39k Accesses

21 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

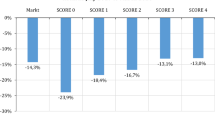

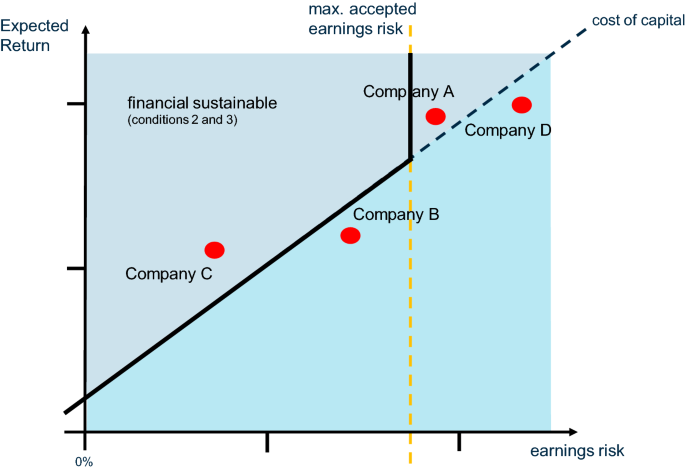

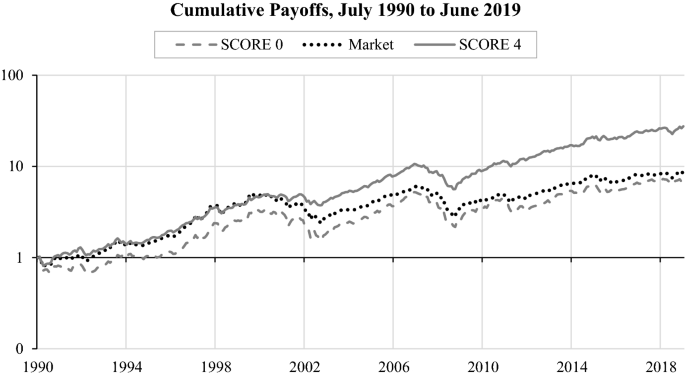

Financial sustainability is underrepresented in both the research on and practice of sustainability management and reporting. This article proposes a conceptual measure of financial sustainability and examines its association with capital market returns. The measure is positioned at the intersection of sustainability management, risk management and risk governance. Financial sustainability is regarded as a crucial control parameter complementing shareholder value and can be viewed by risk-averse investors as a secondary condition of investment decisions. It reduces refinancing and insolvency risks, leading to risk-adjusted excess returns in an imperfect capital market with financing restrictions and insolvency costs. We propose measuring a firm’s financial sustainability in terms of four conditions: (1) firm growth, (2) the company’s ability to survive, (3) an acceptable overall level of earnings risk exposure, and (4) an attractive earnings risk profile. We show that the application of a conditions-based investment strategy to European firms with high financial sustainability (i.e., firms fulfilling all four conditions) over the period from July 1990 to June 2019 results in monthly excess returns of 0.39%. This portfolio’s risk is lower than the risk of market investment. We find that the excess returns increase when incrementally adding each of the four conditions to the investment strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

What happened to financially sustainable firms in the Corona crisis?

Sustainability Reporting in Slovenia: Does Sustainability Reporting Impact Financial Performance?

The impact of sustainability performance indicators on financial stability: evidence from the Russian oil and gas industry

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This article aims to develop a conceptual measure of financial sustainability, which represents a suitable assessment criterion for the purchase of company shares by long-term oriented, risk-averse economic subjects. We examine hypotheses on the relationship between this measure of financial sustainability and stock market returns, in particular the hypothesis that higher financial sustainability leads to higher risk-adjusted equity returns. The measure is positioned at the intersection of sustainability management, risk management and risk governance.

Sustainability has become a widely accepted buzzword in both companies and society at large. However, sustainability is not perfunctory lip service. It has become the main objective of management, as evidenced—in most industrial countries—by corporate governance codes expressing “good governance”, despite implementation differences between countries (for an international overview see Wymeersch 2006 ).

A good example of this change in corporate objectives is the development, over time, of the German Corporate Governance Code (DCGC) that substitutes the primary target “to increase the sustainable value of the enterprise” with the much broader objective of “sustainable value creation”. This imperative replaces the shareholder orientation, present in the original DCGC, with a stakeholder orientation. In the case of Germany—according to Sect. 161 (1) of the German Stock Corporation Act (AktG)—capital market-oriented companies must, in a statement of compliance, explain the extent to which they comply with or justify any deviations from the recommendations of the DCGC (the “comply or explain” rule). This requirement effectively makes the DCGC legally binding. The legal implementation is different in other countries. For example, in the United States (US) and in Spain the corporate governance code is referred to in law and supervised by a government body, more specifically by the securities market supervisor. In Germany, as in the Netherlands, company law contains an explicit reference to the governance code (Wymeersch 2006 ).

In methodological terms, the question arises how to measure “sustainable value creation” or, in general, “sustainability” as the new primary objective of the company. Scholarly research has been dealing with the concept of sustainability for decades: a term that refers to both a time dimension and a scope dimension (Günther et al. 2016 ). In respect of the time dimension, it is possible to differentiate between the ideas of intergenerational and intragenerational justice, presented in the report of the Brundtland Commission of the United Nations (UN). Accordingly, “sustainable development” must “ensure that it meets the needs of the present [generation] without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland Commission 1987 , p. 41).

Furthermore, within any (but especially within a single) generation, economic activities must ensure that both organisations and individuals adequately address all three goals of what is referred to as the triple bottom line (TBL) (creating intragenerational justice): social, ecological and economic (or financial) sustainability (Elkington 2004 ). This constitutes the scope dimension of sustainability. These three sustainability goals are also referred to as the three pillars of sustainability or the 3Ps: people, planet and profit. The related umbrella terms of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate social performance (CSP) cover the simultaneous management of the social and environmental pillars in particular, while the ESG concept (ecological, social, governance) not only captures environmental and social issues but also those of governance. Since it is noted that sustainability management and reporting seldom (if at all) consider economic (or financial) sustainability, this article focuses on financial sustainability. Furthermore, the focus is on the sustainability perspectives of organisations and companies, and not on the macro-economic sustainability perspective of countries.

While economic sustainability covers all topics related to intergenerational and intragenerational economic considerations (with the goal of ensuring the long-term existence of the company)—including a wide range of different management functions such as procurement, production, logistics and marketing—this article considers financial sustainability as dealing solely with the company’s long-term financial security as an important part of the overall goal of sustainability. When applying the basic idea of the Brundtland Commission on sustainable development (Brundtland Commission 1987 ) to financial sustainability, the proposal is that companies’ financial management must ensure present financial success without jeopardising future financial success, including the success of future generations (Günther and Günther 2017 , p. 5).

In addition to sustainability management, a measurement concept for financial sustainability is also important for risk management (Lenssen et al. 2014 ), especially for the strategic and holistic risk governance approach (Stein and Wiedemann 2016 ; Hiebl et al. 2018 ; Hiebl 2019 ). To date, risk management has been assessed in terms of its contribution to company value (e.g., Grace et al. 2015 ; McShane et al. 2011 ). However, company value only partially records risk management goals because it does not incorporate risk-limitation goals. The measure of financial sustainability, presented in this article, remedies this deficiency. Not only is it a common control parameter for risk and sustainability management, but it also suits empirical studies by expressing and proving the benefits of risk governance concepts.

In this article we propose a measurement concept for financial sustainability that is derived from the general understanding of the term. We assume long-term oriented, risk-averse economic agents with an affinity towards sustainability and examine how high financial sustainability affects stock returns.

Our article makes a dual contribution to scholarly literature. Firstly, based on accounting and capital market measures, we develop and propose conditions to operationalise the ambiguous concept of financial sustainability as a formative construct. We expand sustainability accounting and CSR literature—to date focused on social and environmental topics (see, e.g., the meta-analyses of Orlitzky et al. 2003 ; Wang et al. 2016 ; Lu and Taylor 2016 )—by contributing to the operationalisation of economic and (especially) financial sustainability which, in ESG concepts, is viewed as part of governance . Furthermore, we develop conditions to capture and measure the overall objective of “sustainable value creation” as prescribed by regulations (i.e., by the DCGC). In more detail, we propose conditions to measure financial sustainability: (1) a real growth of the firm that prevents its shrinkage or liquidation over time, (2) a significant probability of firm survival, (3) an adequate level of risk exposure by the firm, and (4) an attractive risk–return profile for the owners. These four conditions add to internal and external risk governance approaches as they align with existing approaches to rating, risk management, simulation, company valuation and management control. We therefore establish and develop a link between sustainability and risk management. Thus, we expand financial sustainability literature (e.g., Gregory et al. 2014 ; Gómez-Bezares et al. 2017 ; Henock 2019 ; Zabolotnyy and Wasilewski 2019 ) by including a theory-driven selection of four conditions of financial sustainability despite the fact that a closed theory of “financial sustainability” is missing so far. More specifically, we add earnings risk exposure and an attractive earnings risk profile as conditions, considering that the conditions of growth and insolvency risk have been mentioned and operationalised in prior literature, albeit in a different manner.

Secondly, we test the association between financial sustainability (FS) and stock returns and show that acting upon the suggested conditions results in abnormal future stock market returns. Thus, we expand the literature by analysing a long-term, cross-sectional, international sample of significant size and by associating our financial sustainability measure with an adequate outcome variable of future financial success. We show that an investment strategy which only invests in firms with high financial sustainability (i.e., firms fulfilling all four conditions)—representing 15 European countries and covering the period from July 1990 to June 2019—results in a monthly return of 1.11%, i.e., 0.39% more than the market return. We furthermore find that the abnormal returns increase along with an increase in the number of conditions included in the investment strategy. Robustness tests specifically show that FS best explains stock market returns (and not just real earnings growth) with the inclusion of all four indicators.

Following this introduction, we provide an overview of the literature addressing financial sustainability in Sect. 2 and infer the four conditions of financial sustainability in Sect. 3 . In Sect. 4 , we discuss the operationalisation of these conditions and their relation to risk management, risk governance, simulation and company valuation in detail. In Sect. 5 , we validate our measurement system through an empirical analysis and, in Sect. 6 , reach a conclusion.

2 Financial sustainability in the literature

In the literature, CSR activities—also referred to as corporate social performance (CSP)—have often been related to financial performance as an independent variable, with the latter (financial performance) being the dependent variable, i.e., an outcome of CSR activities. More than four decades ago, Caroll (1979) proposed a three-dimensional CSP model—often addressed in the literature—consisting of social responsibility categories (economic, legal, ethical and discretionary responsibilities), a philosophy of social responsiveness (pro-action, accommodation, defence, reaction) and related social issues (consumerism, environment, discrimination, product safety, occupational safety, shareholder). The economic responsibilities of firms are limited to the “responsibility to produce goods and services that society wants and to sell them as a profit” (Carroll 1979 , p. 500). However, financial sustainability—as defined in our article—is not addressed by any of these three dimensions; a conclusion confirmed by Carroll’s ( 1999 ) review of CSR definitions and their development. The meta-analyses of Orlitzky et al. ( 2003 ) based on 52 empirical studies, of Margolis et al. ( 2009 ) based on 251 studies, of Wang et al. ( 2016 ) based on 42 studies, and of Lu and Taylor ( 2016 ) based on 198 studies aggregate the existing empirical studies of this research stream. Although these meta-analyses do not address financial sustainability as a CSR dimension, they treat financial measures as a consequence of CSR activities and, thus, as a dependent variable. Furthermore, Gómez-Bezares et al. ( 2017 , p. 4) state that “given the variety of viewpoints, it is evident that no single conceptualisation of CSR has dominated past research. Indeed, the literature still lacks a universal definition of this concept”.

Gregory et al.’s ( 2014 ) analysis of the effect of CSR strengths and concerns based on the KLD data base on the financial performance of S&P 500 and Russell 3000 firms, provides a typical example of CSR research. The authors analyse five CSR dimensions (community, diversity, employees, environment, product) but explicitly exclude governance and human rights. As a result, their CSR measure does not include financial sustainability issues. Instead, they use the valuation model proposed by Peasnell ( 1982 ) and Ohlson ( 1995 ) to analyse whether additional CSR information is associated with company value. In addition, they disentangle firm value to explore whether the effects are driven by short-term or long-term profitability, or by growth or changes in the cost of capital. Regarding the overall CSR dimensions, they conclude that CSR strengths are positively valued, whereas CSR weaknesses are negatively valued. When disentangling value into its components, little robust evidence is found of short-term profitability. Subsequently, the risk effects are attributed to industry effects, and the positive growth effects (long-term profitability) for CSR firms are stronger and larger than the cost of capital effects.

In contrast to CSR research, the TBL framework introduces the notion of economic sustainability. The term “Triple Bottom Line” dates to the mid-1990s when the AccountAbility think tank coined and used the term to improve communications with the business world. Elkington ( 1997 and 2004 ) further promoted the term. “In the simplest terms, the TBL agenda focuses corporations not just on the economic value that they add, but also on the environmental and social value that they add—or destroy” (Elkington 2004 , p. 3). In a related step the 3P formulation, “people, planet and profits”, was developed in 1995 and later adopted by Shell in its first Shell Report. In contrast to the CSR concept, the TBL framework explicitly addresses economic sustainability, even though the discussion of environmental and social sustainability is more pronounced.

Inspired by the Brundtland Commission (Brundtland Commission 1987 , p. 41), Basiago ( 1995 ) provides a detailed overview of the development of “sustainability” over time and presents diverse ways of defining the concept. The economic pillar of sustainability addresses the unsustainable way in which goods and services are currently produced. However, our article focuses on the perspective of organisations and companies and not on the macro-economic sustainability perspective of a country. Accordingly, we view financial sustainability as a part of the wider economic sustainability construct, connected to diverse management functions such as procurement, production, sales and logistics. Surprisingly, the definition of financial sustainability as the way in which firms are financially managed to assure that current financial success does not jeopardise future financial success, including the success of future generations (Günther and Günther 2017 , p. 5), is not present in any of the different definition streams addressed by Basiago ( 1995 ). Comparable results are derived when analysing Vos ( 2007 ), who also provides an overview of the definitions of sustainability.

Montiel and Delgado-Ceballos ( 2014 ), in a literature review covering the 1995–2013 period and including both academic and practitioner management journals, analyse different definitions, organisational theories and measures used by management scholars in the field of corporate sustainability. Although they do not explicitly address financial sustainability as a function of economic sustainability, i.e., as one of the three TBL pillars, their list of economic sustainability measures (Montiel and Delgado-Ceballos 2014 , Table 3 ) shows traces of financial sustainability measures. The KLD data base, often used in empirical research, addresses “corporate governance” as one of seven dimensions. The Dow Jones Sustainability Index refers to “corporate governance” and to “risk and crises management” as two of seven dimensions. The Global Reporting Initiative, following Montiel and Delgado-Ceballos ( 2014 ), uses “economic performance” as one of three dimensions. We therefore conclude that financial sustainability is a separate construct, even though its dominant definitions and measurement systems in sustainability research do not specify well-defined and consistent measures.

Despite financial sustainability’s lack of embeddedness in definitions and measures of economic sustainability, it is possible to explicitly differentiate between various research streams that address it on the organisational level. Thus, we find studies on the financial sustainability of specific firms and organisations, such as micro-finance (e.g., Quayes 2012 ; Tehulu 2013 ), local governments (e.g., Dollery and Grant 2011 ; Rodriguez Bolivar et al. 2016 ) and health service institutions (e.g., Birch et al. 2015 ; Thomson et al. 2009 ). Furthermore, financial sustainability is not only addressed by discussing sustainable financing opportunities (e.g., Soppe 2004 ), but also by reorienting the financial sector on sustainability issues, especially through the ongoing sustainable finance project of the European Union (EU) (e.g., European Commission 2021 ) that aims to improve the consideration of ESG criteria in the finance industry.

A rare study that explicitly considers financial sustainability as a dimension of sustainability in the private sector is that of Gómez-Bezares et al. ( 2017 ). Their analysis is based on a content and financial analysis of 65 companies from the FTSE 350 index, covering the 2006–2012 period. It includes financial sustainability as one of nine binary criteria to measure corporate sustainability, which is assessed by comparing the actual growth rate with the sustainable growth rate, namely the Return on Equity (RoE) net of dividends and buybacks. Regarding this period, the authors find that corporate sustainability firms are characterised by higher financial risk exposure, lower asset growth rates, lower book value/market value ratios, lower EVA™ ratios and higher MVA ratios. They conclude that firms incorporating sustainability issues in their business operations can better leverage their resources than other companies, specifically to enhance stronger financial performance and shareholder value creation.

Concerning financial sustainability, Zabolotnyy and Wasilewski ( 2019 ) analyse 12 food companies of Northern Europe for the 2005–2015 period. They define financial sustainability in terms of two dimensions, namely value and continuity. Whereas value is measured by net profit/equity, total assets/current assets, price/book value and revenue/total assets, continuity is measured by current assets/current liabilities, total liabilities/total assets, retained earnings/revenue and interest expense/EBIT. However, they do not explain the choice of the indicators. Aggregated measures of value, continuity and financial sustainability are derived by using fuzzy set logic. In contrast to Gómez-Bezares et al. ( 2017 ), there is also no exploration of an association with an outcome variable.

Finally, Henock ( 2019 ) explores 46 savings and credit cooperative societies (SACCOs) in Eastern Ethiopia for the year 2016. He defines the relationship between adjusted financial revenue and adjusted operating expenses, namely the self-sufficiency of the SACCOs which is a profit measure, as financial sustainability. He also examines whether operational efficiency, return on assets or profitability, the debt equity ratio, deposit mobilisation, donation, yield, interest rate and the size and age of the SACCOs are associated with financial sustainability. He finds that donations, debt to equity ratio, operational efficiency, return on asset and deposit mobilisation are associated with the chosen measure of financial sustainability.

Summarizing the literature on financial sustainability, it is evident that a closed, underlying theory is missing, if a theoretical foundation is addressed at all. The financial sustainability measures cover a wide range of financial indicators, mostly without explaining their derivation or selection. The time frames cover 1 to 10 years, in contrast to the long-term perspective of financial sustainability that, in accordance with the Brundtland Commission, addresses different generations. The sample sizes are relatively small and the underlying samples are limited to single countries or industries. Finally, an outcome variable which measures the effect of financial sustainability is mostly lacking.

To conclude, our study expands the literature on financial sustainability by analysing a long-term, cross-sectional, international sample of significant size. This is done by using a theory-driven selection of four indicators of financial sustainability as a formative construct (adding earnings risk exposure and the attractive earnings risk profile as conditions) and associating our financial sustainability measure with an adequate outcome variable. The conditions, growth, and insolvency risk were mentioned by and operationalised in prior literature, albeit in a different manner.

At present, there is no coherent and closed theory from which financial sustainability can be derived and related to stock market returns. Financial sustainability measures that allow comparison with our measurement concept only exist in a partial and fragmented manner in the literature. What we are looking for is a structure that not only satisfies the properties inherent in the term, but that is ideally "useful" to investors considering that an investment in companies with a high FS also generates above-average risk-adjusted returns.

As the term “Financial sustainability”, emanating from the CSR literature, is thus far neither theoretically classified nor based on a consistent measurement concept, we aim to develop and propose such a concept. Our approach is like that of Piotroski ( 2000 ) who developed a measurement concept with indicator variables for the construct "quality", albeit without an underlying closed theory. Our paper’s basis is the CSR literature’s conceptual understanding of sustainability. This approach views financial sustainability as a hypothetical construct that, for purposes of empirical studies, must be specified by a latent variable with as few parsimonious indicators as possible.

3 Assumptions and conditions of financial sustainability

3.1 assumptions about investors and requirements for financial sustainability.

This study’s main focus is the measurement of financial sustainability as part of the TBL, thereby focusing on sustainable value creation. It subscribes to the application of the Brundtland Commission’s basic idea of sustainable development (Brundtland Commission 1987 ) to financial sustainability, which suggests that companies must be financially managed to ensure present financial success without jeopardising future financial success, including the success of future generations (Günther and Günther 2017 , p. 5). We derive the secondary investment conditions of risk-averse investors with a sustainability preference from this (general) concept of sustainability, which is transferred to the financial sustainability of companies.

Like most economic models, we assume the presence of risk-averse economic subjects, especially risk-averse owners of companies who prefer “less risk” to “more risk”. It is unclear how the amount of risk, e.g., the cash flow of a company, should be measured. Heterogeneous, risk-averse economic subjects will assess the cash flow’s risk amount differently if they use different risk measures. The amount of risk can be expressed by various risk measures, such as the standard deviation, the value at risk or the probability that the cash flow will be interrupted in the event of the company’s possible insolvency. To measure financial sustainability, several risk measures are required as indicators of financial sustainability.

In addition to profitability, liquidity and risk, sustainable investments also consider the criteria of environment, social affairs and good corporate governance (ESG). Concerning companies, the general requirement for sustainability results in direct requirements for their financial sustainability. The Brundtland report’s description of “sustainable development” as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” accentuates two important concepts for understanding sustainability, namely the notions of “needs” and “limitations”. Accordingly, sustainability should provide the goods required to satisfy the resources for as long as possible and, in principle, for an unlimited period.

The central requirement of sustainability is therefore the unlimited, long-term satisfaction of future needs. Present restrictions are acceptable to achieve this, as a result of which secondary conditions emerge for acting in the present. The future satisfaction of needs should not fall below the level of the present satisfaction of needs. To achieve an adequate satisfaction of needs in each individual future period, sustainability implies a limitation of volatility (i.e., the fluctuation of the goods available for the satisfaction of needs) in each period.

These basic requirements can be applied to financial sustainability as a component of sustainability. The focus is on companies whose shares are invested in by risk-averse investors with a sustainability preference. An investment in a company only becomes an option if financial sustainability is given (further aspects of sustainability lead to further constraints).

From the aforesaid explanations of sustainability in general it follows that companies with FS should each have the following characteristics:

The company is set up for an unlimited period and, unless bankruptcy occurs, the expected value of the net income is retained in real terms.

The probability of the company's insolvency, and thus the interruption of the flow of payments to the investor, is limited to an acceptably low level (a zero probability of insolvency is useless to the investor because no company can meet this requirement).

The volatility of the net income is acceptable to the investor in the sense that, from the investor’s viewpoint, a minimum net income requirement is met with sufficient probability.

Beyond these three conditions, financial sustainability can only be assumed if investors endow the company with capital. For risk-averse investors, this is only guaranteed if—as our fourth condition—the expected return on capital exceeds the cost of capital, which in turn can be derived from the company's earnings risks (see condition c). In addition to the level of the return risk, the return requirement depends on the return-risk profile of the alternative investment options available to investors (especially the market price of the risk λ; see the more detailed Sect. 3.2 ). Consequently, the goal of financial sustainability is similar to that of long-term, future-oriented value creation (or value preservation).

The conditions of financial sustainability are also consistent with the so-called principles of capital maintenance in accounting theory, however, financial sustainability as a closed theory is thereby not addressed. In addition to the nominal maintenance of (equity) capital, the principle of real capital maintenance requires that equity capital is also maintained not only nominally, but in real terms by covering inflation (first mentioned by Schmidt 1951 ; see the Anglo-American literature of Edwards and Bell 1961 and Chambers 1966 ). This requirement is consistent with our first condition. The third principle of capital maintenance, i.e., the maintenance of the equity value, is congruent with our fourth condition as it assumes that the net equity value must be maintained before cash streams (e.g., dividends) can flow to shareholders (e.g., Honko 1959 ; Hansen 1962 ; Schneider 1963 ). These principles of capital maintenance form the classical principles of (sustainable) financial management, which can be applied to develop measures for financial sustainability (i.e., to connect capital maintenance principles with enterprise valuation; Günther 1997 ). The aforesaid is based on our assumption that the owners of companies or company shares are, in accordance with the concept of sustainability, interested in the long-term success of the companies.

Standards for sustainable reporting provide a complementary approach to capture financial sustainability. The standards of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) are important in this respect, being the quasi-worldwide standards of sustainability reporting. The 200 series of current GRI standards propose seven reporting areas for economic sustainability, which correspond to the environmental and social sustainability standards (see in the following GRI 2018 ).

In contrast to the reporting areas of standards 201-2 to 207-3, which deal with subproblems of sustainability in terms of their financial impact (e.g., standard 202-1 on gender parity of pay or standard 202-2 on senior management hired from the local community), standard 201-1 proposes a general financial target figure to measure “economic performance”. The direct economic value generated and distributed (EVG&D) is calculated as the difference between revenue (directly generated economic value) and economic value distributed. Indicator 201-1 can be calculated on both the basis of financial accounting figures (“an accrual basis”) and a cash basis. The following expenses are explicitly assigned to the distributed economic value: operational costs, wages, salaries and other payments to employees, payments to investors, payments to governments, and community investments. The EVG&D is an annual figure. Material expenses and purchased services seem to be explicitly excluded so that the EVG&D resembles the concept of value added: a concept that, for decades, has been discussed in accounting and reporting (e.g., Haller and van Staden 2014 ; Haller et al. 2018 ).

Nonetheless, the definition remains unclear and leaves room for discretion. Interestingly, standard 202-1 does not refer to other annual value-added figures such as EVA™ or CVA, even though these figures have been widely discussed in research and practice (e.g., O’Byrne 1996 ; Biddle et al. 1997 ). Multi-year value-oriented performance measures, e.g., book-to-market ratio or Tobin’s Q, are also not considered, thereby ignoring essential economic principles such as accounting for the risk-adjusted cost of capital. The present study differentiates between financial sustainability and economic sustainability within the meaning of the TBL. More specifically, while economic sustainability covers all topics related to intergenerational and intragenerational economic considerations (with the goal of ensuring the long-term existence of the company) for a wide range of different management functions such as procurement, production, logistics and marketing, this article considers financial sustainability as dealing solely with the company’s long-term financial security—as the financial goal derived from the overall sustainability goal.

Gender parity of pay and anti-corruption rules, for example, constitute subject areas of economic sustainability that affect financial sustainability, while financial sustainability primarily deals directly with the maintenance or increase of financial value creation. Reporting area 201-1 of the GRI falls directly in the domain of financial sustainability, while all other areas of the 200 series resort under the domain of economic sustainability. Therefore, the present study focuses on financial sustainability under the umbrella term of economic sustainability.

3.2 Financial sustainability and capital market imperfections

In addition to assumptions about the economic subject, i.e., the risk-averse investor with a preference for sustainability, assumptions must also be made about the environment. A capital market is assumed that offers investors a large number of investment opportunities—by buying shares. The income generated by these companies and distributed to investors is uncertain. We assume that the capital market is imperfect, namely that it is a capital market with financing and rating restrictions, as a result of which companies can become insolvent (distressed risk). Based on empirical research (e.g., Campbell et al. 2008 ; Ang et al. 2009 ; Walkshäusl 2013 ), we also assume that insolvency and earnings risks are not fully included in companies’ share prices, which (c.p.) leads to risk-adjusted excess returns for companies with low earnings and insolvency risks.

A risk-free investment option with a return r f and the option of an investment in the portfolio of all risky assets (companies) with an expected value of return \(r_{m}^{e}\) and risk \(\sigma_{{r_{m} }}\) are available on the capital market. On the capital market, this results in a market price for the risk of

In addition, it is assumed that companies only receive capital from investors on a permanent basis if the expected value of the return corresponds to the cost of capital. Based on the market price of the risk (λ) and the earnings risk of a company, there is a corresponding minimum requirement for its return on investment (Gleißner 2019 ).

FS plays no role for risk-averse investors in the hypothetical world of perfect markets; a world where any increase in risk is countered by an adequate increase in expected returns and where bankruptcies cannot occur due to the lack of funding restrictions. As explained below, we consider FS in a world of imperfect capital markets. Empirical capital market research reveals a number of capital market imperfections (see, e.g., Shleifer 2000 ; De Bondt and Thaler 1987 ; Shleifer and Vishny 1997 ; and Gromb and Vayanos 2010 , as well as the meta-study by Arrfelt et al. 2018 on the link between return and risk). These capital market imperfections, e.g., rating and funding restrictions, lead to additional risks relevant to risk-averse economic subjects, e.g., bankruptcy or distressed risk. These risks are considered when specifying the indicator variables for the financial sustainability construct.

Because of capital market imperfections and the critique of the capital asset pricing model’s (CAPM) assumptions, the financial sustainability approach does not require a perfect capital market accompanied by its underlying assumptions, with the result that investors are not necessarily perfectly diversified. By contrast, there are no financing restrictions or insolvencies (and their associated costs) in a perfect capital market and companies can exist forever, making any discussion of financial sustainability obsolete. The risk management literature also proceeds from the idea of imperfect capital markets, it being the only way to explain the effects of risk management in general and of risk management measures in particular (e.g., McShane et al. 2011 ; Kürsten 2006 ). Risk management that improves financial sustainability reduces the effects of insolvency costs (Kraus and Litzenberger 1973 ) and financing restrictions (Froot et al. 1993 ). It should be noted that, in an imperfect capital mark b et, it is impossible to measure risk solely by means of the CAPM’s beta factor (on the CAPM problems see, e.g., Dempsey 2013a and ; Rossi 2016 ; Subrahmanyam 2010 ). The beta factor can only express a company’s risk exposure—with the exclusion of other financial sustainability aspects such as the probability of survival—in a perfect capital market.

For several years, empirical capital market research has identified a multitude of capital market imperfections and influencing factors on stock returns that cannot be explained by the CAPM on its own. From the viewpoint of sustainability research, it is intriguing that companies with characteristics indicative of a high level of financial sustainability also feature high risk-adjusted excess returns (e.g., Walkshäusl 2018 ). A great deal of evidence exists regarding the volatility and distress anomaly. Empirical studies show that companies with low stock price volatility, a good rating and a low earnings risk produce high returns (e.g., Walkshäusl 2013 ; Campbell et al. 2008 ; Ang et al. 2009 ; and the meta-study by Arrfelt et al. 2018 ). This suggests that companies with a high degree of financial sustainability—specified in the sense below—should have high risk-adjusted, abnormal returns. Hence, the measurement of financial sustainability might be relevant to more than a company’s sustainability management and strategic management: in the long term, an improvement in financial sustainability might also be a way of ensuring the company’s above-average financial performance.

Financial sustainability is relevant from the perspective of risk management. Securinthe empirical analysis, we consideg the going concern of the company, i.e., its financial sustainability, is often seen as the primary goal of risk management. Measurement concepts for financial sustainability are relevant to risk management because they allow the operationalisation of this primary goal. For example in Germany, based on Section 91 of the German Stock Corporation Act in terms of which companies must recognise any “developments that put the continued existence of the company at risk” at an early stage, the continued existence of the company is a core aspect of financial sustainability. However, our study shows that financial sustainability involves more and that it is necessary to consider additional criteria (e.g., the sustainable attractiveness of the company from its owners’ viewpoint). In a value-oriented risk management approach (Gleißner 2019 ; McShane et al. 2011 , 2017 ), financial sustainability may be interpreted as a secondary condition: the objective of corporate management is primarily to maximise company value, taking financial sustainability into account as a secondary condition.

The holistic approach to sustainability management, outlined above, comes close to holistic risk management concepts, particularly the risk governance approach (see Stein and Wiedemann 2016 ; Stein et al. 2019 ; Hiebl 2019 ). The risk governance approach outlines an integrative risk management system that is linked to other fields of corporate governance and considers the interests of both shareholders and other stakeholders (Stein and Wiedemann 2016 ). Measurement concepts for sustainability, especially financial sustainability, are thus particularly useful for the practical implementation of risk governance models (Kim et al. 2014 ).

The measurement of financial sustainability, in particular, is important in “decision-oriented risk management” because the business judgement rule necessitates that any changes to the risk exposure resulting from a “corporate decision” must be identified prior to this decision. The business judgement rule originated in the US where, in contrast to Germany (Section 93 Stock Corporation Act (AktG)), it is not codified in law but influenced by the Principles of Corporate Governance of the American Law Institute and by the jurisdiction of the Delaware Supreme Court. The Companies Act 2006 of the United Kingdom (UK) explicitly requires “reasonable care, skill and diligence” of management, whereas French law addresses the “faute de gestion”. A unique feature of the implementation of the Business Judgement Rule in Germany is that the burden of proof lies with the executive board. Thus, the business decision rule is found in many countries but with different implementations in law (Roth 2009 ; Ponta and Catană 2015 ).

If a decision risks the future viability of the company, it becomes important to point out the decision’s consequences (Graumann et al. 2009 ; Gleißner 2019 ; Hunziker 2019 ). For this reason, the question is posed how financial sustainability can be measured and whether such a measurement system does in fact empirically result in better stock market returns.

The capital market imperfections imply that the owners of (or investors in) firms who hold investments for extended periods are risk-averse actors with financial constraints (i.e., limited equity). Thus, they are potentially interested in the financial sustainability—as opposed to the temporary stock-price volatility—of investments in exchange-listed firms. They assess firms on a rational basis: the flow to equity in relation to the specific risk exposure of the firm. This basis is captured by the conditions of financial sustainability.

3.3 Four indicators for financial sustainability

Because of the properties of “financial sustainability”, derived from the understanding of the term and the CSR literature, four indicator variables result for economical parameterization. Because our measurement model is a formative and not a reflective model, Footnote 1 the four conditions specified by the indicator variables are complementary and not substitutive. Therefore, to speak of financial sustainability, all four must be fulfilled at the same time.

3.3.1 Real preservation of the company (growth > inflation rate)

Accounting theory differentiates between the nominal and the real preservation of a firm’s substance. Condition 1 follows the latter and means that a firm can only be regarded as sustainable if it is not contracting in real terms and if it can sustain its real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) substance. Thus, the company should not disappear “as planned”. Such a disappearance is to be expected only if a negative growth rate is anticipated. In the long term a “steady state”—the so-called “continuation phase”—is assumed to emerge under a consistent capital turnover so that the growth rates of sales and capital are identical (see Schwetzler 2019 on the convergence processes towards a long-term equilibrium). In this case, both a negative nominal growth and a negative real growth are problematic. In other words, a company may be called financially sustainable only if it permanently achieves a growth rate of at least the expected level inflation (also during the continuation phase of company valuation). When the global economy has shown real growth for several years and is likely to show real growth in future due to technological progress, a company’s growth at the level of the inflation rate means that it is losing relevance in relation to the global economy. We specifically address the profit growth rate—unlike a dividend growth rate (Lau 1987 )—to be independent of the distribution policy.

3.3.2 A company’s ability to survive without making demands on its owners (sufficient survival probability of the company)

The assumed risk-averse investors with a preference for the sustainability of a company usually regard company survival as a minimum investment requirement. This is evidenced by the fact that cross-generational family businesses have a particularly high level of resilience and, in addition, an ability to survive (Buchner et al. 2021 ). High survivability means avoiding major crises that could lead to bankruptcy. Such severe crises are the result of previously occurred risks. Early crisis detection and crisis prevention therefore require an analysis of the potential crisis-causing risks, which are regulated in some countries as part of the minimum legal requirements for risk management (e.g., for Germany the 1998 Corporate Sector Supervision and Transparency Act (KonTraG) and the IDW (Institute of Public Auditors in Germany) PS 340 audit standard for the audit of the early risk identification system). The structured identification, quantification, management and monitoring of individual material risks, as well as risk aggregation to determine the overall risk level to a company, are regarded as risk management tasks, especially of the early risk-detection system (for risk management concepts see Froot, Scharfstein and Stein 2004; Vanini 2012 ; Kaplan and Mikes 2016 ; Gleißner 2017a ; Stein and Wiedemann 2018 ; Hunziker 2019 ; Romeike and Hager 2020 ; and the comparative presentation of the scholarly literature on risk management by Braunschmidt et al. 2017 ). Risk aggregation is a central task of the early risk-detection system as developments that threaten the company's existence mainly result from the combined effects of individual risks. Therefore, a company’s ability to survive depends on its aggregate risk exposure (Angermüller et al. 2020 ).

Hence, financial sustainability can be operationalised by the probability of a company’s survival and the avoidance of “developments that put the existence of the company at risk”. This results in points of methodological intersection with insolvency forecasting and an insolvency probability that can be expressed, by a rating, as a measure of the risk to a company’s continued existence. In this context, scholarly literature on company valuation refers to an insolvency risk or distress risk (e.g., Gleißner 2010 ; Saha and Malkiel 2012 ; Friedrich 2015 ; Lahmann et al. 2018 ).

3.3.3 Total earnings risk exposure acceptable to owners

A company’s cash flows to its owners are uncertain. Therefore, from the owners’ perspective, it is insufficient only to consider the probability of survival to assess a company’s total risk exposure. An additional risk-related aspect must be considered. Risk-averse owners prefer less risky investment opportunities to riskier ones. It is necessary to consider the company’s earnings risk, expressed as measures of risk such as the standard deviation, the variation coefficient or the value-at-risk of the cash flows (see Albrecht et al. 1998 for the relevance of downside risk).

A company can be regarded as financially sustainable if its risk exposure is acceptable to its owners. Thus, two questions arise: What risk measure can be used to express the risk preferences of the owners (Renn 2008 ; Slovic 1987 ; Sarin and Weber 1993 )? What level of risk exposure (measured by aggregating all risks of a firm) are owners willing to accept? Limitations on acceptable risk exposure are explained in the safety-first approaches of financial management (Roy 1952 ; Telser 1955 ; Campbell et al. 2008 ), as well as in the risk-tolerance concepts developed by the interpretation of legal requirements, e.g., in Germany by the IDW PS 340 (2020) and the DIIR Revision Standards No. 2 (2018).

Formally, this third condition requires the formulation of a threshold for a specific risk measure. In principle, the threshold can be related to different risk measures. For example, risk of loss (equity capital requirement to buffer potential losses and avoid over-indebtedness operationalised as value-at-risk at a specified probability level p (VaR p ), where variable p depends on the level of security desired by the owners, i.e., the accepted insolvency probability) and earnings volatility (scope of possible deviations of planned annual net earnings) illustrate the range of risk measures. The determination of one or more risk measures and a corresponding acceptable risk exposure limit are required to define financial sustainability.

3.3.4 Economic interests of the owners in a lasting continuation of the company (attractive risk–return profile)

A final condition of financial sustainability is to ensure that the company is likely to survive in the long term, i.e., that it is neither terminated by (1) insolvency, which was addressed as the second condition, nor (2) abandonment by its owners. The latter aspect captures the economic attractiveness of the company for the owners. Sustaining the investment in the company makes economic sense when an investment in one’s own company is profitable—i.e., when the company offers an attractive risk – return profile to its owners or investors, in comparison with alternative investment opportunities. Only an economically attractive company is operated on a long-term basis. The alternative to long-term continuation is liquidation. In a real, imperfect capital market, it makes sense to compare expected returns with the risk-adjusted cost of capital required for that return. The cost of capital should reflect the actual aggregated earnings risks of the company and not the CAPM-reflected, historical stock return fluctuations. It follows that a company’s expected return should be higher than the expected return of alternative investment opportunities with the same risk. In other words, the expected average return must exceed the risk-adjusted cost of capital. In a multi-period context, this leads to a demand for a fundamental capitalised earnings value greater than the net asset value (reproduction or liquidation value) of the equity capital.

The understanding of the term “financial sustainability”, based on the earlier conceptualisation of Günther and Günther ( 2017 ), can therefore be summarised as follows: a financially sustainable company has a positive real growth rate, a high probability of survival (low probability of insolvency), a relatively low earnings risk, and a risk–return profile that makes it a sufficiently attractive investment for its owners.

Considering these four conditions as proposed, it is possible to regard financial sustainability as a subjective construct. Human beings’ different perceptions of and propensities for risk result in different thresholds of financial sustainability, especially when it comes to the second and third conditions. Thus, for a more objective operationalisation of financial sustainability, these thresholds must be discussed and calibrated in a robust and conservative manner.

Financial sustainability can be regarded as a complex latent construct—i.e., a construct which cannot be directly observed but which can be indirectly measured by various indicators (e.g., the four conditions). A detailed discussion of financial sustainability is therefore required to achieve a solid understanding. Effective indicators, thresholds to assess adequacy (especially concerning the second and third conditions), and measurement techniques tailored to each indicator are required to produce a rewarding discussion.

3.4 Hypotheses of the association between financial sustainability and stock market returns

We want to test the relationship between the suggested FS measure and stock market performance. The capital market imperfections summarized in Sect. 3.2 suggest that companies with a high FS and thus a insignificant risk should achieve above-average stock market returns. Over the decades, CSR and sustainability research were driven by the question whether it pays to be “good” (social sustainability) or whether it pays to be “green” (environmental sustainability). The meta-analyses of Orlitzky et al. ( 2003 ), Margolis et al. ( 2009 ), Wang et al. ( 2016 ) and Lu and Taylor ( 2016 ) for CSR and of Endrikat et al. ( 2014 ) for corporate environmental performance (CEP) aggregate existing primary studies and identify moderators for the relationships. All meta-analyses answer both aspects of the aforesaid question with a “yes”. The general idea behind the question is whether a firm’s financial performance is harmed if firms are sustainable. In the same vein, we ask the same question with respect to the third pillar of the TBL, namely financial sustainability, and whether it pays to have sustainable financial management.

Financial sustainability is future oriented to be relevant to investor decisions. Although financial sustainability is an ex-ante figure, its measurement is based on historical data (as is customary practice, e.g., when deriving the CAPM-beta factor as a determinant of future stock returns based on historical stock returns). It is therefore assumed that the evaluated past information on the four conditions is representative of the future. The future representativeness of the historical earnings risks, i.e., the coefficient of variation, does not have to be assumed if insider information is available on the company's plans and related risks, because this information can be used to derive a forecast of a future coefficient of variation using stochastic simulation.

However, for an external evaluation of firms, this data are unavailable for our large, cross-sectional sample. As a result, we can only measure financial sustainability (FS) based on historical data and relate the resulting financial sustainability score portfolios with future stock market returns of the subsequent year. Therefore, the analysis is ex post.

By following the aforesaid considerations, financial sustainability becomes a prerequisite for investment in firms: its absence or inadequacy at a firm makes investors unwilling to invest. Financial sustainability is a potential success factor because it increases firms’ financial leeway and reduces refinancing and insolvency risks, both of which may result in above-average future financial returns in an imperfect capital market. This conclusion results in hypothesis H1 :

Financial sustainability is associated with above-average future stock market returns.

We regard a financially sustainable firm as a firm that fulfils all four conditions of financial sustainability; i.e., in our empirical analysis, a SCORE 4 firm. As the four suggested measures for financial sustainability are derived from the term and general understanding of sustainability and because they represent distinct characteristics of financial sustainability, all four conditions form a formative and not a reflective latent construct of financial sustainability. This means that the four conditions work complementarily and not substitutionally. Thus, we empirically explore whether firms’ financial performance increases with the number of conditions which are met, which results in hypothesis H2 :

Average stock market returns increase with the number of fulfilled conditions of financial sustainability.

4 Operationalisation of the conditions of financial sustainability

4.1 overview.

The conditions relied upon to define financial sustainability address intertwined concepts across the fields of management control, risk management and corporate finance (see Sect. 3.1 ). For this reason, the measurement of financial sustainability is connected to business-related areas such as risk management, rating and risk-adjusted company valuation. Risk management deals with risk-bearing capacity and the statutory requirements for the early identification of “developments threatening the company’s existence", rating constitutes a measure of insolvency risk and other threats to a company’s existence, and risk-adjusted company valuation, which makes company value a key indicator of the risk–return profile, is calculated with the cost of capital being dependent on the earnings risk and by accounting for insolvency risk. Collectively, these areas provide the necessary measuring procedures.

To define financial sustainability, three items are required for all four conditions: (1) a measured variable, (2) an operational measurement method, and (3) a threshold value representing a minimum requirement for companies. Based on the breadth of the term’s meaning, it is assumed that all four conditions must be met for a company to qualify as financially sustainable. No credit is provided if a company fails to meet any single condition; these conditions are assumed to have complementary effects, not substitutional ones. Whereas real growth, the first condition of financial sustainability, does not pose major measurement challenges, the second to fourth conditions are intertwined with the concepts of risk management, rating and risk-adjusted firm valuation. We elaborate on these conditions in more detail.

4.2 Real growth rate

Long-term forecasts of the growth rates of a company’s sales or net earnings (or of their expected value) are extremely problematic: no approach in the academic literature is deemed suitable for such forecasts. In response, a simple and pragmatic solution is proposed to operationalise this criterion of financial sustainability. A positive real growth rate for the company is assumed when:

management forecasts a positive real growth rate of net earnings for a mid-term planning period (e.g., the forthcoming 5 years) and

a positive real growth rate of net earnings was achieved in the recent past (e.g., the last 5 years).

Other characteristics (such as sales) might be considered or required. For them, the expected value of the company’s real growth rate must be positive when considering the probability of insolvency. In the long term, the probability of insolvency acts like a negative growth rate. However, we do not consider this probability in our empirical study. To simplify matters, only the achieved real growth rate over the last 5 years is considered, instead of management’s growth forecasts. The historic real growth rate of net earnings is set as the estimator of the future real growth rate. Alternatively, it is possible to use the growth forecasts of financial analysts. This is usually the case when determining implicit capital costs (e.g., in Daske et al. 2006 ).

4.3 Measurement of the company’s survival probability via rating and developments threatening its existence

To ensure financial sustainability, developments threatening a company’s existence must be avoided as far as possible, thereby implying that they only occur with an acceptable low probability (e.g., a defined p max p.a.). A measurement is made of the degree of threats to the company’s existence, operationalised as the probability of insolvency.

The measuring procedures used in this case are based primarily on the company’s financial figures—return on capital, interest coverage ratio and equity ratio—and usually account for additional qualitative factors (via market position, for instance) (see, e.g., Altman 2000 ; Ohlson 1980 ). The weakness of these measuring systems is that they are incapable of adequately recording the extent of the company’s risks, which historic financial figures do not reflect (see Blum et al. 2005 ; Bemmann 2007 ). However, a more precise evaluation of the threat to a company’s existence (and therefore its financial sustainability) is possible if corporate risks are also considered. These rating approaches, based on risk analysis and risk simulation, also use risk management methods.

To identify developments that threaten the company’s existence by means of risk simulation (Monte Carlo simulation), it is necessary to define the phrase threatening [a company’s] existence . In general terms, as can be seen from the insolvency codes of a country (the InsO for Germany; see Haarmeyer and Frind 2018 ), a development that threatens a company’s existence is assumed when:

equity is negative (over-indebtedness), or

there is impending illiquidity, in the case of which

covenants are infringed, resulting in a termination of loans, or

the minimum rating requirements are no longer met (i.e., they fall below a B rating).

Failure to meet rating requirements (as per 2b) is also an existential threat to unlisted companies. Since the Basel II Agreement, the lending policy of credit institutions are based on (1) company ratings and (2) collateral available from companies or their owners.

A more precise assessment of possible existential threats requires a detailed risk analysis and risk aggregation using a Monte Carlo simulation. The effects of deviations, e.g., on net income, covenants and rating, can be examined by aggregating the quantified risks in the context of planning, in which opportunities and risks are understood as the causes of possible deviations from the plan. Developments that threaten the company’s existence in the simulation are scenarios in which a combination of the effects of various risks leads to an infringement on covenants or a failure to meet minimum rating requirements (Gleißner 2017b ; Grisar and Meyer 2015a and b ).

Without the simultaneous analysis of different corporate risks (i.e., risk aggregation) and their implications for the future rating, threats to a company’s existence are not usually recognisable and, therefore, financial sustainability cannot be assessed.A risk inventory or risk matrix that only considers individual risks in isolation is not productive because multiple risks usually co-exist and may occur in conjunction.