How We Redesigned the New York Times Opinion Essay

When a team of editors, designers and strategists teamed up to talk about how times opinion coverage is presented and packaged to readers, they thought of a dinner party..

The NYT Open Team

By Dalit Shalom

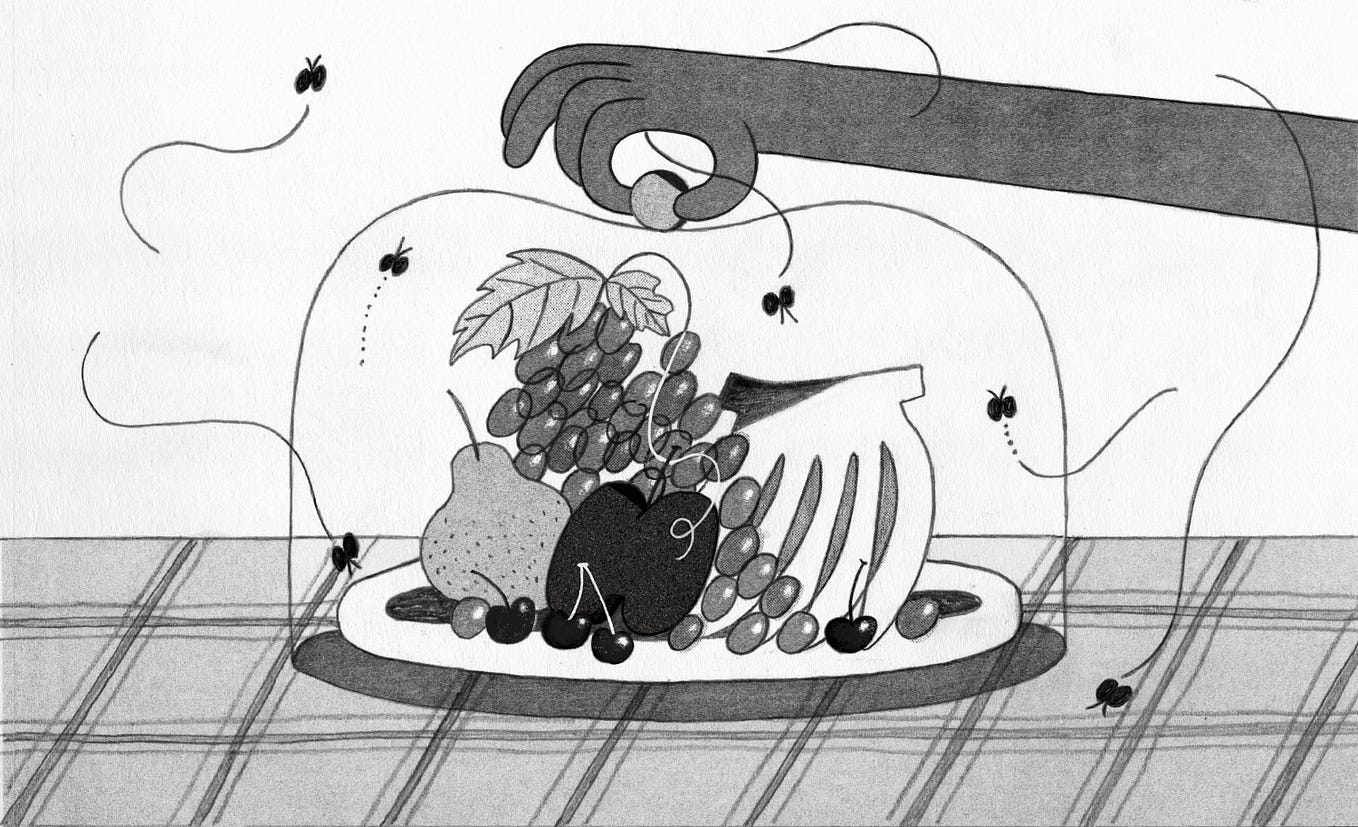

Picture a dinner party. The table is set with a festive meal, glasses full of your favorite drink. A group of your friends gather around to talk and share stories. The conversation swings from topic to topic and everyone is engaged in a lively discussion, excited to share ideas and stories with one another.

This is what we imagined when we — a group of New York Times editors, strategists and designers — teamed up last summer to talk about how to think about how our Opinion coverage is presented and packaged to our readers. We envisioned a forum that facilitated thoughtful discussion and would invite people to participate in vibrant debates.

The team was established after a wave of feedback from our readers showed that many people found it difficult to tell whether a story was an Opinion piece or hard news. This feedback was concerning. The Times publishes fact-based journalism both in our newsroom and on our Opinion desk, but it is very important to our mission that the distinction between the two is clear.

The type of Opinion journalism our group was tasked with rethinking was the Op-Ed, which was first introduced in the Times newspaper in 1970. The Op-Ed was short for “opposite the Editorial Page,” and it contained essays written by both Times columnists and external contributors from across the political, cultural and global spectrum who shared their viewpoints on numerous topics and current events. Because of the Op-Ed’s proximity to the Editorial Page in the printed newspaper, it was clear that published essays were Opinion journalism.

Then The Times began publishing online. Today, most of our readers find our journalism across many different media channels. The Op-Ed lost its clear proximity to the Editorial Page, and the term has been used broadly as a catch-all phrase for Opinion pieces, leaving the definition of what an Op-Ed is unclear.

To learn more about the friction our readership was describing, we held several research sessions with various types of Times readers, including subscribers and non-subscribers. Over the course of these sessions, we learned that readers genuinely crave a diversity of viewpoints. They turn to the Opinion section for a curated conversation that introduces them to ideologies different than their own.

In the divided nature of politics today, many readers are looking for structured arguments that prepare them to converse thoughtfully about complicated topics. Some readers said they want to challenge and interrogate their own beliefs. Others worry that they exist in their own bubbles and they need to understand how the “other side” thinks.

And across the board, readers said they are aware that social media platforms can be echo chambers that help validate their beliefs rather than illuminate different perspectives. They believe The Times can help them look outside those echo chambers.

Considering this feedback, we took a close look at the anatomy of an Op-Ed piece. At a glance, Opinion pieces shared similar, but not necessarily cohesive, properties. They had an “Opinion” label at the top of the page that was sometimes followed by a descriptive sub-label (for example, “The Argument”), as a way to indicate a story belonged to a column. That would be a headline, a summary and a byline, often accompanied by an image or video before the actual text of the story.

By looking at those visual cues, it became clear to us that they could be reconfigured to better communicate the difference between news and opinion.

We created several design provocations and conducted user testing sessions with readers to see how this approach and a new layout might resonate. Some noticeable changes we made include center-aligning the Opinion label and header, labeling the section in red and providing more intentional guidance and art direction for visuals that accommodate Opinion pieces.

While many readers could tell the difference between news and opinion stories, they didn’t understand why certain voices were featured in the Opinion section. They wanted more clarity about the Op-Ed, such as who wrote it and whether the writer was Times staff or an external voice. In the case of external contributors, readers wanted to know why the desk chose to feature their voice.

These questions took our team back to the drawing board. We began to realize that the challenge at hand was not solely a design problem, but a framing issue, as well.

We had long philosophical conversations about the meaning of Op-Ed pieces. We talked about the importance of hosting external voices and how those voices should be presented to our readers. The metaphor of a dinner party figured prominently in our conversations: the Opinion section should be a place where guests gather to engage in an environment that is civil and respectful.

We began to sharpen how we might convey the difference between an endorsement of a particular voice and hosting a guest — one of many who might contribute to a lively debate around a current event.

The more we thought about the Opinion section as a dinner party, the more we felt how crucial it was to communicate this idea to readers.

As we approached the designs, we set out to create an atmosphere for open dialogue and conversation. Two significant editorial changes came out of our group conversations.

After many iterations, we decided to introduce a two-tiered labeling system, so that readers could understand unequivocally the type of Opinion piece they were about to engage with. For external voices, we added the label “ Guest Essay ,” alongside other labels that indicate staff contributors and internal editorials. The label “Guest Essay” not only shifts the tone of a piece — a guest that we are hosting to share their point of view — but it also helps readers distinguish between opinions coming from the voice of The Times and opinions coming from external voices.

The second important editorial change is a more detailed bio about the author whose opinion we are sharing. With the dinner party metaphor in mind, this kind of intentional introduction can be seen as a toast, providing context, clarity and relevance around who someone is and why we chose them to write an essay.

Some of these changes may seem subtle, but sometimes the best dinner conversations are nuanced. This body of work signals an important moment for The New York Times in how we think about expressing opinions on our platform. We believe that one of the things that makes for a healthy society and a functioning democracy is a space for numerous perspectives to be honored and celebrated. We are confident these improvements will help further Times Opinion’s mission of curating debate and discussion around the world’s most pressing issues.

Dalit Shalom is the Design Lead for the Story Formats team at The New York Times, focusing on crafting new storytelling vehicles for Times journalism. Dalit teaches classes on creative thinking and news products at NYU and Columbia, and in her free time you can find her baking tremendous amounts of babka.

Written by The NYT Open Team

We’re New York Times employees writing about workplace culture, and how we design and build digital products for journalism.

More from The NYT Open Team and NYT Open

How to Dox Yourself on the Internet

A step-by-step guide to finding and removing your personal information from the internet..

CJ Robinson

How the New York Times Games Data Team Revamped Its Reporting

Huge amounts of data from wordle and connections changed the way our team approached data infrastructure and design.

Rethinking How We Evaluate The New York Times Subscription Performance

An exploration into the growth data team’s process of designing and building a new subscription reporting model..

Estimation Isn’t for Everyone

The evolution of agility in software development, recommended from medium.

Design at the Speed of News

Our design colleagues, jay guillermo and chen wu spoke at figma’s annual config conference in san francisco and shared what’s it like….

Ameer Omidvar

Apple’s all new design language

My name is ameer, currently the designer of sigma. i’ve been in love with design since i was a kid. it was just my thing. to make things….

Stories to Help You Grow as a Designer

Interesting Design Topics

Icon Design

Matej Latin

UX Collective

90% of designers are unhirable?

Or why your cookie-cutter portfolio doesn’t cut it and how to fix it.

Dylan Babbs

Uber Design

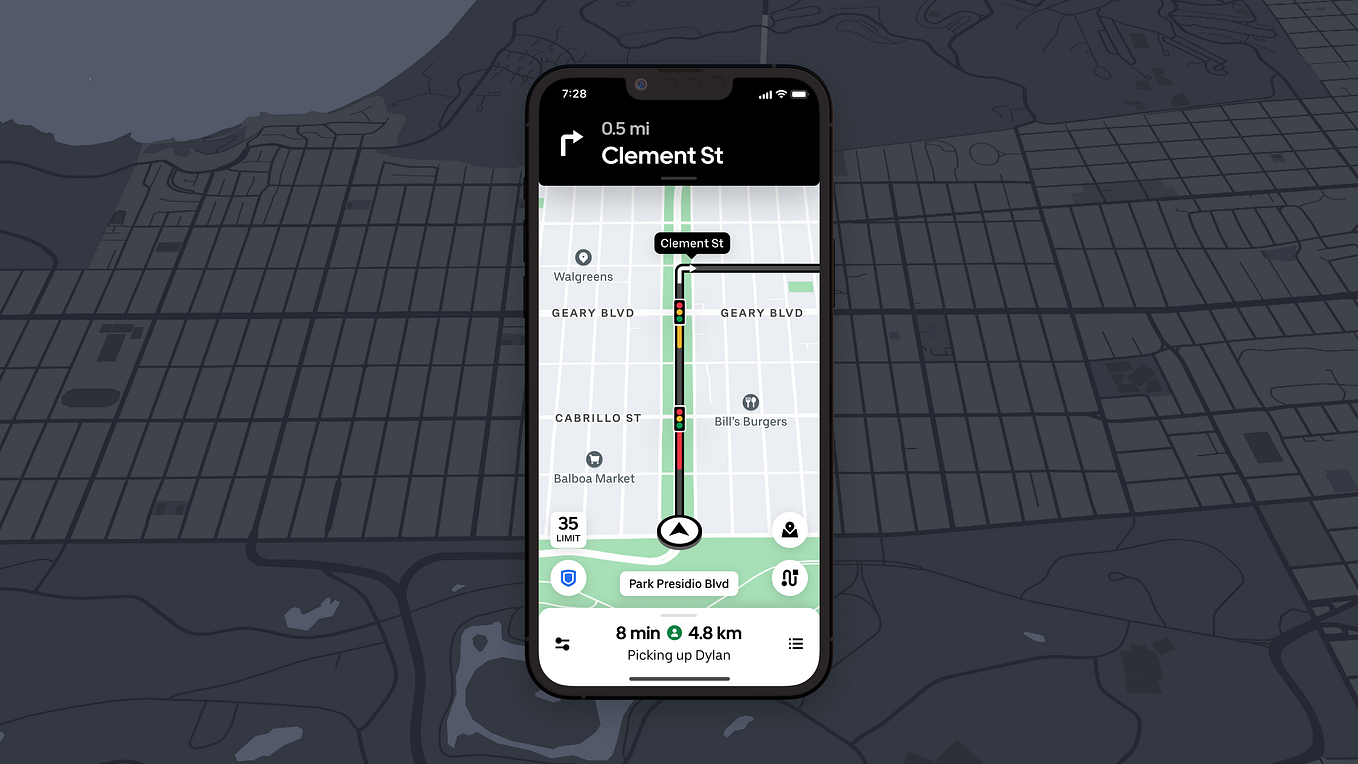

Designing the latest generation of Uber Navigation: maps built for ridesharing

The story of how we redesigned uber navigation from the ground up using rapid prototyping and data-driven design..

Punit Chawla

How Airbnb Became a Leader in UX Design

From a small bed & breakfast to a leader in ux/ui design, this billion dollar startup is a leader in innovation and design thinking.

Mirijam Missbichler

Why Japanese Websites Look So Different

& how to analyze design choices without jumping to conclusions.

Text to speech

Vanessa Mobley Joins Opinion to Lead Op-Ed Team

Opinion announces Vanessa Mobley will join Times Opinion as head of Op-Ed team.

We have exciting news to announce about one of Opinion’s leadership positions vital to shaping our daily report and some of our most influential work.

Starting Feb. 7, Vanessa Mobley will join the Times as Op-Ed editor, overseeing our stellar team of editors in charge of guest essays and contributing writers on politics, culture, international affairs, business, health, climate and much more. She will work with the vertical leaders and our Op-Ed staff to pursue our goals of ever-higher quality in writing, originality in argument, and ambition in the swings we take at the biggest ideas and challenges facing society and the world today.

Having worked with many accomplished writers, including a few of our own, Vanessa brings a fiercely creative mind, an insightful collaborative style, deep editing experience and a competitive hunger for exciting and smart pieces to Times Opinion. She is a clear thinker who loves crystalizing an idea and pairing it with a great author, and she is a thoughtful listener and empathetic colleague who wants the work on her team to be great — but also be a thrill to do.

Most recently, Vanessa was vice president, executive editor at Little, Brown and Co., where she published Clint Smith’s “How the Word Is Passed,” Ronan Farrow’s “Catch and Kill” and Beth Macy’s “Dopesick,” among other acclaimed books. She is widely respected in the publishing industry for her instinct for talent, narrative and excellence in writing, and prized by her authors for her incisive feedback and edits.

Previously, Vanessa worked at Crown, Penguin Press, Henry Holt and Basic Books. She has edited best-selling and prize-winning books from a diverse group of journalists and academics including Pulitzer Prize winners Samantha Power (“A Problem From Hell”), Caroline Elkins (“Imperial Reckoning”) and Liaquat Ahamed (“Lords of Finance”); scholars Peniel Joseph (“Waiting ’Til the Midnight Hour”), Moustafa Bayoumi (“How Does It Feel to Be a Problem?”), Dorothy Roberts (“Shattered Bonds”), Matthew Crawford (“Shop Class as Soulcraft”), Reuben Jonathan Miller (“Halfway Home”); and journalists Chris Hayes (“Twilight of the Elites”), Sheri Fink (“Five Days at Memorial”), Rebecca Mead (“My Life in Middlemarch”), Binyamin Appelbaum (“The Economists’ Hour”), Wesley Lowery (“They Can’t Kill Us All”), Scott Shane (“Objective Troy”), Josh Levin (“The Queen”), Reeves Wiedeman (“Billion Dollar Loser”), Michelle Goldberg (“The Means of Reproduction”), Seyward Darby (“Sisters in Hate”), Bridgett M. Davis (“The World According to Fannie Davis”) and Kate Fagan (“What Made Maddy Run” and “All the Colors Came Out”).

Vanessa is a graduate of Williams College and did graduate coursework in English at the University of California, Berkeley.

The Op-Ed team will also soon enjoy the talents of one of our strongest and most trusted editors: Brian Zittel . In recognition of a job well done launching Opinion’s newsletter portfolio, Brian’s role is expanding to become managing editor for both Op-Ed and newsletters. As an experienced planner and problem solver, Brian will work closely with Vanessa and Patrick to focus on coordinating our daily line-up of guest essays and newsletters to ensure smooth workflow and execution, and help support the Op-Ed team while continuing to oversee our newsletters.

We are looking forward to what’s to come.

— Kathleen Kingsbury and Patrick Healy

Explore Further

Jyoti thottam named editorials editor, more opinion announcements, opinion’s newest team members.

We use cookies and similar technologies to recognize your repeat visits and preferences, as well as to measure and analyze traffic. To learn more about cookies, including how to disable them, view our Cookie Policy . By clicking “I Accept” on this banner, you consent to the use of cookies unless you disable them.

News from the Columbia Climate School

Writing and Submitting an Opinion Piece

Kevin Krajick

The opinion pages are one of the best-read sections of any publication, in print or online—often on par with front-page news. And, some of the most attentive readers are decision makers: top people in government, corporations and nonprofit institutions. Appearing there is a prime way for the nonprofessional writer to get a valuable perspective into the public eye. Here is a how-to guide.

What kind of piece?

There are two basic forms: the essay (often referred to as op-ed), and letter to the editor. (“Op-ed” comes from when all newspapers were actually printed on paper, and outside writers customarily appeared on the page OPposite staff-written EDitorials. The New York Times recently traded this old-fashioned term for “guest essay.”)

Opinion essays don’t normally come from just anyone; the writer usually has some special expertise or credibility on the topic. This might include lawyers, ex-government officials or scientists. A piece may also come from someone with an especially telling or powerful personal experience relating to the topic—for example, an essay on homelessness by someone who has been homeless. They can run 400-1,200 words. Some generate a small fee.

Letters to the editor generally run just 100 to 150 words (or edited, even shorter). They are welcome from pretty much anyone. But those with credentials often stand a better chance of getting published. Whoever you are, don’t expect payment.

What are my chances?

Most publications want only pieces that play off the news of the last few days, or the week. After that, your letter is a dead one. So, in most cases, is your op-ed. Act fast.

That said, something may be going on below the public radar that should be in the news, but has not surfaced. If you know something, you say something; an op-ed can help to break the news. Maybe an invisible threat to public safety, or an unnoticed scientific discovery. Ideally, your topic will be timely, but at the same time have a long shelf life (i.e., the issue won’t be solved in a day or a month). Occasionally, you may find a “peg” for your piece: a holiday, anniversary, election, upcoming conference, report, a pending vote in Congress.

In all cases, depending on where you submit, calibrate expectations accordingly. Major publications, especially big dailies like The New York Times , may receive hundreds of op-eds each day, and even more letters to the editor. They will use only a few. In publications with less competition, your odds increase.

What makes a good op-ed?

It’s not just your opinion. It begins with facts, and makes an argument based on facts. It is informed by logic—not emotion or ideology. You can educate without preaching. And it’s not just a complaint; you must almost always offer next steps or possible solutions for the matter at hand.

Editors want pieces that don’t just wow you with expertise; they want pieces that are colorful, fast-moving and provocative—hallmarks of any good writing. A good op-ed is concise. It hits hard. It marshals vivid images, analogies and, when appropriate, anecdotes. E ditors see the opinion page as a place for advocacy, denunciations, controversy and astonishment. They want to stimulate community discussion and drive public debate. They want people to say, “Wow! Did you see that op-ed today?”

What makes a good letter to the editor?

Same stuff basically, except in a nutshell. OK, maybe a little more pure outrage is acceptable. Just make your case, and make it fast.

How to write it ?

Whether op-ed or letter, your piece must unfold quickly. Focus on a single issue or idea. State what the issue is, and let us know where you stand. That should happen in the first short paragraph or two. Following paragraphs—the meat in the sandwich, so to speak—should back your viewpoint with factual or first-hand information. Near the end, clearly restate your position and issue a call to action.

Some specifics to keep in mind:

- Grab the reader’s attention in the first line. End with a strong, thought-provoking line.

- Come down hard on one side of the argument. Never equivocate.

- Identify and acknowledge the counterargument; then refute it with facts.

- Use active verbs; g o easy on adjectives and adverbs.

- Avoid clichés.

- Avoid acronyms.

- A void technical jargon.

- Cite specific references and easy-to-understand data.

Next step: All writers need editors. You might show your piece to a colleague or two in your field to see if they can poke holes in it. Or, if you know a good writer, ask them how the piece might be strengthened. You can also contact your institution’s communications staff; helping out is often part of their job. (But ghostwriting is not.) No guarantee someone can turn your junky screed into an influential masterpiece—but editing almost always helps.

Finally, include a catchy headline that conveys your message. This will help the editor grasp the idea quickly, and help sell your contribution. (However, expect the publication to write its own headline; that’s just how it works.)

Must someone sign off?

In most workplaces, there is no requirement that you submit a piece to management— especially in academia. It is understood that you’re speaking for yourself, not the institution. That said: your title and affiliation will usually appear with your byline. So in that sense, you indirectly represent the honor and credibility of your institution. A controversial piece that is well articulated, well read and respectful raises the profile of your institution. This is rarely viewed as bad.

Where and how to submit?

Everyone wants their piece in The New York Times . Few will ever see it there. Unless you have something super-strong, consider other options. Some national general-interest outlets with a big demand for copy include The Hill , CNN Opinion , Huffington Post, The Daily Beast and Slate . The Conversation specializes in op-ed-type pieces from academics. Is your piece more regional or specialized? Check regional or specialized media. Local papers are always looking for a local angle on wider issues. Publications that cover energy, law or other topics are of course looking for that kind of piece.

If you or someone you know happens to know the opinion editor, you can send directly to him or her. Otherwise, most publications have a web page telling you where to send, and their particular requirements. Don’t fret if you don’t have an inside line; editors really do read those over-the-transom submissions.

Letters to the editor can often be sent in the body of an email. Most op-ed submissions are made in an emailed Word document. For the subject line in either case, that catchy title mentioned earlier will come in handy. If it’s an op-ed, write the editor a short note in the email body telling her/him what the piece gets at, and why you’re the person to get at it. Include your contact info and, if you want, a brief bio.

In general, submit to one publication at a time. Unfortunately, editors may take days or weeks to get back—and if it’s a rejection, you may not hear at all. ( New York Times policy: if you don’t hear in 3 days, you’re rejected.) If you feel you must submit to more than one, let the editors know. But avoid submitting the same piece to two publications in the same geographical or readership market. Higher-prestige places will require that you offer to them exclusively.

Where can I find more guidance?

Below, some good resources. The OpEd Project in particular has not only advice, but a list of specific contacts and guidelines for submitting pieces. Good luck!

The OpEd Project website

How to Write an Op-ed, Step by Step The Learning Agency

Writing Effective Op-eds Duke University

Writing Letters to the Editor Community Toolbox

Writing Effective Letters to the Editor National Education Association

Tips for Aspiring Op-Ed Writers New York Times

And Now a Word From Op-Ed New York Times

Related Posts

Why the COP28 Loss and Damage Decision Is Historic

How Word Choices in the Mainstream News Media Signal a Country’s Level of Peace

Putting This Summer’s Record Global Heat Into Context

NO MORE BLOOD FOR OIL

While war rages in Eastern Europe, life goes on elsewhere. Yet it is marked by fear and

resentment, especially in the United States, already torn apart by political strife and the

dread of yet another election cycle, with all that it entails. Understandably, the average

person (however one defines that abstraction) is worried about inflation. At the moment,

Americans are complaining vehemently about the high price of gasoline. Yet very little has

been said or written about how high (or low) those fuel prices are. When we compare the

current price at the pump to that in several other countries, including our North American

neighbors, Great Britain, the European Union, and the three nations most affected by the

war in Ukraine, the enormous disparity between our own situation and that facing people

elsewhere becomes apparent. Extrapolating from accurate and up-to-date data available

on the web, here is a table (adjusted for currency values, units of measurement and annual

household income) that makes those differences as precise as they are unmistakable:*

Gas Price Unit Cost Annual Income Relative Cost Purchase Power

U.S. $4.84 1.00 $79,400 1/16,405 (100.00) U.K. $3.70 0.76 $40,040 1/10,822 65.96

E.U. $4.46 0.92 $44,091 1/9,886 60.26 Canada $6.20 1.28 $54,652 1/8,815 53.73

Poland $22.22 4.59 $5,906 1/265.80 1.62 Mexico $103.17 21.32 $7,652 1/74.17 0.45

Ukraine $145.17 29.99 $2,145 1/14.78 0.09

Russia $672.79 139.00 $6,493 1/9.65 0.06

*Currency Rates: 1 USD = $0.92 EU, $0.76 £, $1.28 CAN, $22.80 złoty, $20.92 pesos, $29.66 UAH, $133 roubles Sources: globalpetrolprices.com; worldpopulationreview.com; statista.com; CNNbusiness.com (March 12, 2022)

By a sublime yet tragic irony, Russia, whose proven oil and natural gas reserves are three times larger than those of the United States, has by far the highest petroleum prices in the world. As

Ukraine is suffering from the Russian onslaught, Russians are suffering from the actions of their

government on a scale we can scarcely imagine. Adjusted for income levels, the gap between

both countries and their more affluent counterparts becomes astronomical. Mexico, although

still classed as a developing nation, is much better off than either one; Poland, though besieged

by refugees and threatened by invasion, is downright wealthy compared to the other three. As

the purchasing power index shows, America enjoys a standard of living that (in crude oil terms)

is 1,667 times higher than Russia, 1,111 times that of Ukraine, and 222 times that of Mexico, an

oil producing nation in its own right. That does not imply that we have no right to object to an

increase in gas prices, or that we should be grateful for what we have, and not make noise about

the conditions we face, both as individuals and as a society. It does mean that we must put such

matters in global perspective, and that it is not becoming for us to act beleaguered, put upon, or

oppressed, when our situation is not so much a major hardship as it is a minor inconvenience, or

a mere side effect of an underlying economic disease, caused by the unholy alliance between oil

cartels and political operatives, East and West. The pandemic started two years ago; but OPEC

is nearly half a century old, and shows no signs of abating, despite the routine lip service paid to

alternative energy sources, environmental regulations, and an end to domestic drilling, both on

land and off-shore. “Energy independence” is neither an unattainable ideal nor an inducement

to promote the use of fossil fuels. But if Europe relies on Russian oil, what does Russia rely on?

And for how long can it withstand the misery and suffering that it has inflicted on itself, let alone

those whom it failed to bully into submission? Who will die first—the oligarch, the imperialist,

or the global monopolist? And who will pay the steep price, let alone, clean up the whole mess?

Meanwhile. the U.S. imports nearly half (48%) of its oil, not from Venezuela or the Middle East

but from Canada, which accounts for over 90% of their oil exports. How long can we continue

deceiving ourselves about why trucker convoys swarmed upon Ottawa? Or about the role that

Athabascan sands (in the province of Alberta) play in fiscal diplomacy, never mind the Alaska

pipeline? And how long can either Russia or the United States remain superpowers, while mired

in myths, misconceptions and militarism, while everyone on the ground is caught in a vise, even

as they struggle to survive? Blaming the villain (Putin) is easy; rooting out economic causes

and human consequences of what passes for domestic as well as foreign policy is much harder.

[cf. Vaclav Smil, Energy and Civilization: A History (Cambridge, MA, 2017); Richard Rhodes,

Energy: A Human History (New York, 2018); R. Buckminster Fuller, Critical Path (New York,

1981). Fuller’s warnings are as apt now as they were four decades ago, only far more urgent].

Yet it must be done, or the world will perish in flames, losing its grip while clinging to illusions.

As Adam Smith prophesied on the eve of the American Revolution, “this empire [Great Britain]

. . . has hitherto existed in imagination only . . . it is surely now time that our rulers should either

realize this golden dream . . . or that they should awake from it themselves, and endeavour to

awaken the people. If the project cannot be completed, it ought to be given up” (The Wealth

of Nations [1776], “Of Public Debts,” V.3. ad fin.; ed. Edwin Cannan [1904], new pref. George J.

Stigler (Chicago, 1976), Vol, II, 486). If we don’t change our ways, extinction will be our lot—

our fossils will tell the tarry tale, as it did for all the dinosaurs who once ruled the earth.

I think Putin will go down in history as a waster of young russian lives also a barbarian and for nothing he must not like the russian people ether as thay also suffer mothers losing sons wives losing husband children losing father’s what an a*%*#h##&£#_

That goes without saying, yet it does nothing to change the situation. It also ignores the fact that neither his friends nor his foes among the nations of the world are any less guilty of creating and perpetuating the misery and suffering which you rightly condemn. Invective is neither helpful nor illuminating. As Sam Rayburn used to say, “you can always tell a man to go to hell, but making him go there is another story entirely.” When you find the words to make that happen, let me know.

Get the Columbia Climate School Newsletter →

NY Times Rebrands ‘Op-Eds’ as ‘Guest Essays’: ‘We Are Striving to Be Far More Inclusive’

“It is a relic of an older age and an older print newspaper design,” the Times’ opinion editor says of the term “op-ed”

The New York Times is retiring the term “op-ed” and renaming opinion pieces written by outside writers as “guest essays,” the paper’s opinion editor, Kathleen Kingsbury, said on Monday.

“It’s time to change the name. The reason is simple: In the digital world, in which millions of Times subscribers absorb the paper’s journalism online, there is no geographical ‘Op-Ed,’ just as there is no geographical ‘Ed’ for Op-Ed to be opposite to,” Kingsbury wrote in a piece announcing the changes . “It is a relic of an older age and an older print newspaper design.”

Editorials will still be called the same, but former “op-eds” will now be called “guest essays” — a label that will also appear “prominently above the headline,” Kingsbury said.

The change comes 50 years after the first op-ed was published in the Times and is an effort to be “more inclusive,” according to Kingsbury.

“It may seem strange to link changes in our design to the quality of the conversation we are having today. Terms like Op-Ed are, by their nature, clubby newspaper jargon; we are striving to be far more inclusive in explaining how and why we do our work,” Kingsbury wrote. “In an era of distrust in the media and confusion over what journalism is, I believe institutions — even ones with a lot of esteemed traditions — better serve their audiences with direct, clear language. We don’t like jargon in our articles; we don’t want it above them, either.”

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- About this site

- Fox News Is Not News

- Democracy in Danger

- The Biden Presidency

- Rewrite Desk

- Objectivity

- New York Times

- Washington Post

- False Equivalence

- Campaign Coverage

- Covering Race

- Anonymous Sources

- Trump and the Coronavirus

- Horse-Race Journalism

- Fighting Disinformation

- Donate/Contact

New York Times says goodbye to ‘op-eds’ and hello to ‘guest essays’ — but will it invite in the rest of America?

Changing a label, in and of itself, never solves anything. But the New York Times opinion section’s big announcement last week that “op-eds” will henceforth be known as “guest essays” is a fantastic and important move — if editors there are bold enough to take the next logical steps.

The result could be a brilliant reinvention of the intellectual public square, full of wonderfully diverse voices where the only barrier to entry is a willingness to argue in good faith.

A space currently bounded by conventional establishment wisdom — occasionally breached by trolling — could instead expose the Times audience to the full range of national discourse, with all interesting, relevant and honestly argued viewpoints welcome.

This of course is a best-case scenario. It depends on Times opinion editor Kathleen Kingsbury and her new deputy Patrick Healy (fresh from overseeing the Times’s deeply flawed politics coverage ) openly recognizing the error of their previous ways.

While that might seem almost inconceivable, they do take their marching orders from publisher A.G. Sulzberger, who, at an all-hands staff meeting after he fired Kingsbury’s predecessor James Bennet back in June, bluntly expressed his view that the op-ed format was broken. “I think there’s a structural problem with the form itself,” he said.

So how does this reinvention begin with a label change? Let me explain.

The term “op-ed” was antiquated, opaque and, most importantly, ambiguous. Although the “op-ed” designation was ostensibly intended (since its coinage 50 years ago) to provide views distinct from those of the Times itself — with its essays placed “opposite” the editorial page — the presence of the Times’s own staff “op-ed columnists” muddled the message, effectively giving anything that ran there the imprimatur of the Times.

As University of Maine journalism professor Michael Socolow , who has traced the history of the Time op-ed page, explains: “For many Times readers (and even employees), the page looks like a unified platform or singularly powerful megaphone, and therefore anyone given access must be pre-approved and judged endorsement-worthy.”

So while the Times opinion section was publicly committed to a tolerance for “different views,” it was effectively a space defined by its columnists, who ranged all the way from upper-class center-left to upper-class center-right. Of late, center-right extended to include climate skepticism and anti-Arab racism but not Trumpism. Center-left stopped well short of anti-capitalism. And the voices of the marginalized were off the page almost entirely.

Now, with the “guest essays” label putting non-staff writing clearly at arm’s length, the original mission of the op-ed feels attainable.

Quality control, not opinion control

That would mean an actual diversity of views, not just from across the traditional political spectrum, but across other spectra as well. Kingsbury vowed precisely that in an interview on CNN’s “Reliable Sources” on Sunday, saying: “We want to publish a wide range of opinions, arguments, ideas, whether it’s across the left-right spectrum, but as most Americans, you know, really looking far beyond that spectrum.”

She also said, “We can’t be afraid to hear out and interrogate all ideas, especially bad ones, because in my opinion, that’s the most effective way to knock them down.”

CNN’s Brian Stelter recognized that as a powerful principle: “So, read it, challenge it, rebut it. That’s the opposite of cancel culture, isn’t it?”

“Exactly,” Kingsbury said.

There are still some things that guest essayists shouldn’t be allowed to do on the pages of the New York Times — chief among them inciting violence and advocating genocide. But beyond that, if a view is held by a politically significant portion of the American electorate, it deserves to be part of the mix.

That means explicitly welcoming anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist and pro-Arab arguments that have historically been shunned, as well as writers who are younger, more diverse, less credentialed and less fortunate.

And especially now, the political right has a lot of explaining to do. With the Republican Party unmoored from reality, actively nativist and anti-science, it’s crucial that people who speak for it be invited to at least attempt to articulate what their actual views are and how they arrived at them.

The key for the Times opinion section going forward should be quality control, not opinion control. There should be a near-zero tolerance for bad-faith arguments — those that rely on false statement, hyperbole, unfair descriptions of competing views, absurd straw men, logical fallacies and trolling. But as long as the arguments are honest, I think almost anything goes.

That would be a huge ratcheting up of standards from those the Times opinion page currently applies, which mostly rely on the quaint notion of “ fact-checking ,” which is both anemic and insufficient .

Not every publication could pull this off — in fact, maybe not any publication other than than the Times — but did you know that nearly 150 people work in its opinion section?

This is where editors come in.

Here’s what Sewell Chan, the editorial page editor of the Los Angeles Times — and a former deputy opinion editor at the New York Times — had to say in a recent panel discussion , which I think was dead-on:

Instead of thinking about “Are some ideas acceptable or not acceptable?” … what I think we’re more likely to be encountered with are ideas that are provocative or challenging or difficult or controversial. And our job as editors is to help the writer — whether we personally agree or not is not relevant — our job is to help the writer adduce evidence to make the strongest possible logical and persuasive case. But it ultimately has to be a case that is grounded in logic, persuasion and evidence. And if we do that, I actually think a lot of ideas that are provocative or difficult can enter the discourse. And yes, they’ll provoke people or upset people. But we’ve done our duty as opinion editors because we’ve at least exposed our readers to the broad range of views throughout.

Practically speaking, helping some writers meet those standards will be hard, if not impossible — especially for essayists who are at heart advocating such things as nativism or Christian supremacy, but are accustomed to launching their arguments by denying any such thing.

And it may be impossible for Republicans to honestly address the most important question of the moment: Why they continue to engage in the Big Lie (and so many smaller ones).

But then they’ve opted out; they haven’t been silenced. If they complain about being canceled, just turn over the email chain.

Imagine if a process like this had been in place when Sen. Tom Cotton wrote an op-ed last June full of slippery and dishonest arguments attempting to incite the violent dispersal of Black Lives Matter protesters. Rather than getting published — and then retracted, but only after a newsroom revolt that ended Jim Bennet’s career — it would have been either edited into an honest expression of Cotton’s objection to BLM protests or, more likely, spiked.

Who is this person and why did we invite them?

As part of the “redesign” of Opinion, New York Times lead product designer Dalit Shalom promised a “second important editorial change”: “a more detailed bio about the author whose opinion we are sharing.”

Adopting a “dinner party metaphor,” the designer wrote that “this kind of intentional introduction can be seen as a toast, providing context, clarity and relevance around who someone is and why we chose them to write an essay.”

There’s been no sign of any such thing thus far. Bios remain a couple or three lines long, offering little more than institutional affiliations.

But increased transparency is an essential part of the way forward, as I argued immediately after Bennet’s ouster . Firstly, it would fix the longstanding problem caused by the wildly insufficient identification of opinion writers’ sometimes spectacular conflicts of interests.

Beyond that, it would provide readers with valuable context: Why was this person invited to offer a guest essay in the first place? What do they bring to the table?

In some cases, that could even include a warning: an advisory that the views expressed are potentially highly offensive to those who share the Times editorial board’s devotion to “progress, fairness and shared humanity,” but nevertheless are an important part of the national discourse, and that this writer has been judged to be making their argument in good faith.

That distancing — combined with an honest and defensible reason for publishing — would make it much harder for the Times to amplify something like the Cotton piece, whose only value was to allow the Times to brag that is publishes views from “both sides.”

But let’s be clear: The publishing of performative garbage has not stopped under Kingsbury. When right-wing icon Rush Limbaugh died in February, Kingsbury understandably wanted to showcase a variety of writers, each with “a distinctive and authoritative point of view on Limbaugh’s legacy.”

(The essay from feminist Jill Filipovic – “Cracking open his slobbering hatred of women allows insight into his success, as well as the perversion of the party he championed,” she wrote — was one of the sharpest pieces of opinion journalism I’ve read all year.)

But for the fan-boy view, Kingsbury picked Ben Shapiro, the hard-right provocateur well known for his bad-faith arguments.

In an essay explaining her thinking , Kingsbury acknowledged Shapiro’s “trollish online presence and, to me, unpalatable views.” But she defended her selection by calling him “popular” on the right and “well positioned to carry Limbaugh’s message to a new generation of listeners.”

What Shapiro turned in , predictably, was a stream of offensive, valueless liberal-eye-poking that praised Limbaugh for “fighting back against the predations of a left that seeks institutional and cultural hegemony.”

As political journalist Mehdi Hasan tweeted , Shapiro was allowed to write about Limbaugh, in the New York Times, without having to “mention or grapple with” Limbaugh’s record of misogyny and bigotry.

There might have been some value in hearing Shapiro honestly address Limbaugh’s darkness — and apparently, the Times editors actually asked him to. In a podcast a few days later , after Megyn Kelly mockingly quoted Hasan’s tweet, Shapiro replied that the Times’ editors “wanted me to do some of that stuff too.” But, he said, “I’m not gonna do that.”

Kingsbury published his piece anyway. She shouldn’t have.

How to expand the range

Ironically, considering what a debacle that was, Kingsbury’s concept of featuring a variety of voices on a particular topic should be one of the ways the Times starts to diversify its guest essays going forward — with the ever-present requirement that they actually have something of value to offer, and do so without deceit.

Another good move would be to encourage writers to respond to what they’ve read in the opinion pages, something explicitly discouraged in the current guidelines , which relegate such responses to the Letters page.

When someone like author Heather McGhee writes something as mind-blowing as her Feb. 13 op-ed about how white people turned the U.S. economy into a zero-sum game after the civil rights movement, that’s an occasion to host a multiplicity of views. Admittedly, in this case, Times columnist Michelle Goldberg proceeded to write about it and Times podcaster Ezra Klein interviewed McGhee — but why not get responses from people who have watched this process play out, and for that matter people who defend it?

Immigration policy is a hugely important, complicated and nuanced issue that would benefit from an intelligent debate. Some issues, like voting rights, have only one defensible view, but the opinion page should try to find someone on the opposing side who will be honest about their goals, at least.

I’d like to see open discussion about media narratives and framing. Should the behavior of the Republican Party continue to be normalized by political reporters, no matter how extreme it is? At what point do you declare a politician, or a party, presumptively untrustworthy?

The opinion pages should also address fundamental underlying issues that rarely make it into daily journalism despite their significance in day-to-day life, like wealth inequality, educational inequality, misogyny and the corrupting lure of money.

Professional writers aren’t the only people with opinions. So the Times’s guests should include non-writers. People living incarcerated lives. People living in poverty. The undereducated. Revive the “as told to” format, if necessary. Washington Post reporter Eli Zaslow’s Voices from the Pandemic series reminded us of its incredible power.

The ubiquity of both cell-phone video and Zoom conferences suggests new ways of presenting the voices of real people.

It’s quite possible that only the Times, with its huge opinion staff, could do this right. As I wrote last year, the major investment Bennet made in investigative reporting projects for the opinion section — which seems redundant to me — could be better used finding and raising up underrepresented voices, especially those of oppressed people.

As Sewell Chan has said, “people’s authentic lived experiences” are “often as important a form of authority as traditional research scholarship.”

The key, of course, is not just to look for soundbites that fit a predetermined narrative (an unfortunate hallmark of Kingsbury’s new deputy, the aforementioned Patrick Healy). The key is to find people who lead representative lives and get them to honestly express not just what their views are, but how they came to hold them.

In her essay explaining the opinion redesign, Kingsbury hearkened back to the original goals of the op-ed section — “the allure of clashing opinions well expressed” — and vowed to host a space “where voices can be heard and respected, where ideas can linger a while, be given serious consideration, interrogated and then flourish or perish.”

I wish her godspeed. But doing that will depend on her recognizing how much more there is to do than change a label.

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

Trump’s Third Act? American Gangster.

By Samuel Earle

Mr. Earle is the author of “Tory Nation: How One Party Took Over.”

In recent months, Donald Trump has been trying out a new routine. At rallies and town halls across the country, he compares himself to Al Capone. “He was seriously tough, right?” Mr. Trump told a rally in Iowa in October , in an early rendition of the act. But “he was only indicted one time; I’ve been indicted four times.” (Capone was, in fact, indicted at least six times.) The implication is not just that Mr. Trump is being unfairly persecuted but also that he is four times as tough as Capone. “If you looked at him in the wrong way,” Mr. Trump explained, “he blew your brains out."

Mr. Trump’s eagerness to invoke Capone reflects an important shift in the image he wants to project to the world. In 2016, Mr. Trump played the reality TV star and businessman who would shake up politics, shock and entertain. In 2020, Mr. Trump was the strongman, desperately trying to hold on to power by whatever means possible. In 2024, Mr. Trump is in his third act: the American gangster, heir to Al Capone — besieged by the authorities, charged with countless egregious felonies but surviving and thriving nonetheless, with an air of macho invincibility.

The evidence of Mr. Trump’s mobster pivot is everywhere. He rants endlessly about his legal cases in his stump speeches. On Truth Social, he boasts about having a bigger team of lawyers “than any human being in the history of our Country, including even the late great gangster, Alphonse Capone!” His team has used his mug shot — taken after he was indicted on a charge of racketeering in August — on T-shirts, mugs, Christmas wrapping, bumper stickers, beer coolers and even NFTs. They’ve sold off parts of the blue suit he was wearing in that now-infamous photo for more than $4,000 a piece (it came with a dinner with Mr. Trump at his Mar-a-Lago resort).

Commentators have long pointed out that Mr. Trump behaves like a mob boss: The way he demands loyalty from his followers, lashes out at rivals, bullies authorities and flaunts his impunity are all reminiscent of the wiseguys Americans know so well from movies and television. As a real-estate mogul in New York, he seems to have relished working with mobsters and learned their vernacular before bringing their methods into the White House: telling James Comey, “I expect loyalty”; imploring Volodymyr Zelensky, “Do us a favor”; and pressuring Georgia’s secretary of state, “Fellas, I need 11,000 votes.” But before, he downplayed the mobster act in public. Now he actively courts the comparison.

Mr. Trump’s audacious embrace of a criminal persona flies in the face of conventional wisdom. When Richard Nixon told the American public, “I am not a crook,” the underlying assumption was that voters would not want a crook in the White House. Mr. Trump is testing this assumption. It’s a canny piece of marketing. A violent mobster and a self-mythologizing millionaire, Capone sanitized his crimes by cultivating an aura of celebrity and bravery, grounded in distrust of the state and a narrative of unfair persecution. The public lapped it up. “Everybody sympathizes with him,” Vanity Fair noted of Capone in 1931, as the authorities closed in on him. “Al has made murder a popular amusement.” In similar fashion, Mr. Trump tries to turn his indictments into amusement, inviting his supporters to play along. “They’re not after me, they’re after you — I’m just standing in the way!” he says, a line that greets visitors to his website, as well.

Mr. Trump clearly hopes that his Al Capone act will offer at least some cover from the four indictments he faces. And there is a twisted logic to what he is doing: By adopting the guise of the gangster, he is able to recast his lawbreaking as vigilante justice — a subversive attempt to preserve order and peace — and transform himself into a folk hero. Partly thanks to this framing, it seems unlikely that a criminal conviction will topple his candidacy: not only because Mr. Trump has already taken so many other scandals in his stride but also because, as Capone shows, the convicted criminal can be as much an American icon as the cowboy and the frontiersman. In this campaign, Mr. Trump’s mug shot is his message — and the repeated references to Al Capone are there for anyone who needs it spelled out.

In an essay from 1948, “The Gangster as Tragic Hero,” the critic Robert Warshow sought to explain the unique appeal of gangster fables in American life. He saw the gangster as a quintessentially American figure, the dark shadow of the country’s sunnier self-conception. “The gangster speaks for us,” Warshow wrote, “expressing that part of the American psyche which rejects the qualities and the demands of modern life.”

It is easy to see why gangster fables appeal to so many Republican voters today. They are stories of immigrant assimilation and success, laced with anti-immigrant sentiment and rivalry. Their heroes are creatures of the big city — those nests of Republican neuroses — who tame its excesses through force but never forget God or their family along the way. In many ways, minus the murder, they are ideal conservative citizens: enterprising, loyal, distrustful of government; prone to occasional ethical lapses, but who’s perfect?

Mr. Trump knows that in America, crooks can be the good guys. When the state is seen as corrupt, the crook becomes a kind of Everyman, bravely beating the system at its own game. This is the cynical logic that the gangster and the right-wing populist share: Everyone’s as bad as anyone else, so anything goes. “A crook is a crook,” Capone once said. “But a guy who pretends he is enforcing the law and steals on his authority is a swell snake. The worst type of these punks is the big politician, who gives about half his time to covering up so that no one will know he’s a thief.”

It’s a worldview powerful enough to convince voters that even the prized institutions of liberal democracy — a free press, open elections, the rule of law — are fronts in the biggest racket of them all. This conceit has a rich pedigree in reactionary politics. “Would-be totalitarian rulers usually start their careers by boasting of their past crimes and carefully outlining their future ones,” Hannah Arendt warned.

The gangster’s brutality also taps into what Warshow and others of his generation saw as the sadism in the American mind: the pleasure the public takes in seeing the gangster’s “unlimited possibility of aggression” inflicted upon others. The gangster is nothing without this license for violence, without the simple fact that, as Warshow put it, “he hurts people.” He intimidates his rivals and crushes his enemies. His cruelty is the point. The public can then enjoy “the double satisfaction of participating vicariously in the gangster’s sadism and then seeing it turned against the gangster himself.” “He is what we want to be and what we are afraid we may become,” Warshow wrote. Reverence and repulsion are all wrapped up.

Capone’s rise, demise and exalted afterlife don’t hold happy clues for Mr. Trump’s opponents. Dethroning a mob boss is never easy. “He was the 1920s version of the Teflon man; nothing stuck to him,” Deirdre Bair wrote in a 2016 biography of Capone. After he was arrested in 1931 for tax fraud, his mob continued to prosper for another half-century, and Capone himself, who was released after six and a half years in prison for health reasons and died from a stroke and pneumonia in 1947 at age 48, achieved a type of immortality. Mr. Trump will see in his story many reasons to be cheerful. “I often say Al Capone, he was one of the greatest of all time, if you like criminals,” Mr. Trump said in December. It was an interesting framing: “if you like criminals”? Mr. Trump has a hunch, and it’s more than just projection, that many Americans do.

Samuel Earle is the author of “Tory Nation: How One Party Took Over.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , X and Threads .

N.Y. Times Retires ‘Op-Ed’ Page For Guest Essays

NEW YORK (AP) — The New York Times is retiring its Op-Ed page and inviting guests.

The newspaper said Monday it is eliminating the designation it has been using since 1970 to signal opinion columns written by outsiders. The name, meant to designate opinions that appeared on the page opposite the newspaper’s own viewpoints on issues, doesn’t make much sense at a time many people experience the writing digitally, said Kathleen Kingsbury, the Times’ opinion editor.

Institutions like The Times can better serve their audiences with direct, clear language, she wrote.

She said the Times likes people invited to write guest essays to sometimes be surprised by the offer, and for the editors to be surprised by submissions from writers or on ideas new to them.

Comments (6)

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

LeCouteur says:

June 15, 2022 at 5:53 am

PapersOwl offers many free features for its users. In terms of writing tools, it provides a plagiarism checker, citation generator, and thesis, conclusions, and title page generator. While these tools can’t replace a real writer, they can save you time and money. The site also offers several articles on popular student topics. If you’re not sure whether PapersOwl is right for you, check out this PapersOwl review.

billyroberts says:

July 14, 2022 at 3:07 am

In the R – Result paragraph, you should provide a summary of the points raised in the previous sections. It is important to keep in mind that your scholarship essay is expected to be two pages long, so it is crucial to adhere to the formatting requirements of the scholarship essay. Welcome to EssayMap You should also remember that most scholarship essay formats contain a character limit. In most cases, this limit is 250 words or one typed page double-spaced. When in doubt, you can do a word count using a program such as Google Docs or Microsoft Word. Another option is to use a letter counter. This will help you to estimate how many words you have written.

Finley Campbell says:

August 4, 2022 at 5:02 am

This decision is a major step in the direction of disbanding the boundaries between journalism and opinion.

Kostenlose Aufsatzproben finden Sie hier https://studycorgi.de/

Frikkow says:

August 12, 2022 at 9:22 am

Gaskoin says:

February 3, 2023 at 12:13 am

I appreciate you sharing this important and fascinating information. I can use it to aid with my assignment. And recently, there have been several. I only had to complete a difficult assignment. The write my paper https://paper24.com/ was used to complete this task. It’s simpler for me to ask for help than to waste time on something I’m not sure of.

elizabethgorgon1 says:

October 1, 2023 at 7:53 am

To begin work on your dissertation, you must conduct preliminary research. Depending on your specific field, this may involve visiting archives, studying scientific literature, or conducting laboratory experiments. If you don’t have time for this, you can always get help here https://collegepaper.net/buy-college-papers/

Stay Connected

- Newsletters & Alerts

- Become a Member

- Join TVN Plus

Programming Everywhere: A TVNewsCheck Conference Presented at NAB Show 14 April 2024

Streaming revenue strategies for local tv 16 may 2024.

- View more events

Media Sales

- Inspired Lives

KSBW Reporter

- Monterey / Salinas / Santa Cruz, CA

National Advertising Sales Account Executive

- Get After It Media

NewsTECHForum 2023 Keynote Panel —Democracy, Technology, TV Journalism and the 2024 Election

NewsTECHForum 2023 - Chasing AI: Threatening or Enhancing the News?

NewsTECHForum 2023 - Adapting to a Culture of Continuous Crisis

TV2025 2023 - Collaboration and the Future of Content Creation

TV2025 2023 - Building a Breakout Hit in a Multiplatform World

Webinar: Tech Leaders on Trends in 2024

Talking TV: Emily Barr on Sinclair's Shuttered Newsrooms

TV2025 2023 - Station Group Leaders on the State of the Industry

TVN Webinars

All TVN Videos

Sponsored content.

Drive audience engagement with streaming weather

Navigating the AI revolution in media sales: challenges, trust and harnessing custom AI solutions

Megaphone TV launches new interactive sponsorship platform

Elevate your media sales game: embracing data for a competitive advantage

The 4 walls of television interactive sponsorship sales

The future of cyber insurance: Navigating the complex digital landscape

Why an alerting strategy will help win customers in a multi-platform world

Future-proof compliance with AI speech-to-text technology

Applied AI: An unseen revolution in local TV advertising

Real-time news polls have never been this easy

The year of getting everything connected

Local stations continue to see interactive sponsorship success

What the latest AI breakthroughs mean for live and archive content

How top broadcasters expand compliance logging to embrace OTT monitoring

Delivering creativity on budget and without technological constraints

Byron Allen: Too much talk, not enough action on advertising equity

Market share.

TVNewsCheck’s April Fools Sales Special On Job Postings

Apr 01, 2024

WTAE’s Hour-Long Doc Examines What Happens After Dark In Pittsburgh

Mar 26, 2024

CBS Shows Some Love To Its Station’s News Producers

Mar 25, 2024

Special Reports

Newstechforum: the complete videos, in 2024, spot tv is all about political, updated top 30 station groups: nexstar retains top spot, gray now no. 2 as fcc-rejected standard general drops off.

Things you buy through our links may earn Vox Media a commission.

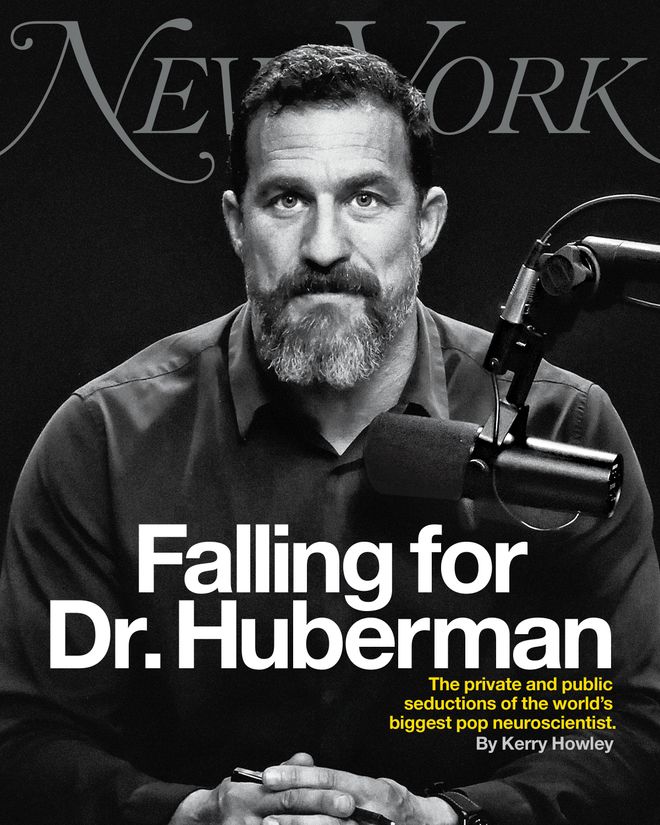

Andrew Huberman’s Mechanisms of Control

The private and public seductions of the world’s biggest pop neuroscientist..

This article was featured in One Great Story , New York ’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

For the past three years, one of the biggest podcasters on the planet has told a story to millions of listeners across half a dozen shows: There was a little boy, and the boy’s family was happy, until one day, the boy’s family fell apart. The boy was sent away. He foundered, he found therapy, he found science, he found exercise. And he became strong.

Today, Andrew Huberman is a stiff, jacked 48-year-old associate professor of neurology and ophthalmology at the Stanford University School of Medicine. He is given to delivering three-hour lectures on subjects such as “the health of our dopaminergic neurons.” His podcast is revelatory largely because it does not condescend, which has not been the way of public-health information in our time. He does not give the impression of someone diluting science to universally applicable sound bites for the slobbering masses. “Dopamine is vomited out into the synapse or it’s released volumetrically, but then it has to bind someplace and trigger those G-protein-coupled receptors, and caffeine increases the number, the density of those G-protein-coupled receptors,” is how he explains the effect of coffee before exercise in a two-hour-and-16-minute deep dive that has, as of this writing, nearly 8.9 million views on YouTube.

In This Issue

Falling for dr. huberman.

Millions of people feel compelled to hear him draw distinctions between neuromodulators and classical neurotransmitters. Many of those people will then adopt an associated “protocol.” They will follow his elaborate morning routine. They will model the most basic functions of human life — sleeping, eating, seeing — on his sober advice. They will tell their friends to do the same. “He’s not like other bro podcasters,” they will say, and they will be correct; he is a tenured Stanford professor associated with a Stanford lab; he knows the difference between a neuromodulator and a neurotransmitter. He is just back from a sold-out tour in Australia, where he filled the Sydney Opera House. Stanford, at one point, hung signs (AUTHORIZED PERSONNEL ONLY) apparently to deter fans in search of the lab.

With this power comes the power to lift other scientists out of their narrow silos and turn them, too, into celebrities, but these scientists will not be Huberman, whose personal appeal is distinct. Here we have a broad-minded professor puppyishly enamored with the wonders of biological function, generous to interviewees (“I love to be wrong”), engaged in endearing attempts to sound like a normal person (“Now, we all have to eat, and it’s nice to eat foods that we enjoy. I certainly do that. I love food, in fact”).

This is a world in which the soft art of self-care is made concrete, in which Goop-adjacent platitudes find solidity in peer review. “People go, ‘Oh, that feels kind of like weenie stuff,’” Huberman tells Joe Rogan. “The data show that gratitude, and avoiding toxic people and focusing on good-quality social interactions … huge increases in serotonin.” “Hmmm,” Rogan says. There is a kindness to the way Huberman reminds his audience always of the possibilities of neuroplasticity: They can change. He has changed. As an adolescent, he says, he endured the difficult divorce of his parents, a Stanford professor who worked in the tech industry and a children’s-book author. The period after the separation was, he says, one of “pure neglect.” His father was gone, his mother “totally checked out.” He was forced, around age 14, to endure a month of “youth detention,” a situation that was “not a jail,” but harrowing in its own right.

“The thing that really saved me,” Huberman tells Peter Attia, “was this therapy thing … I was like, Oh, shit … I do have to choke back a little bit here. It’s a crazy thing to have somebody say, ‘Listen,’ like, to give you the confidence, like, ‘We’re gonna figure this out. We’re gonna figure this out. ’ There’s something very powerful about that. It wasn’t like, you know, ‘Everything will be okay.’ It was like, We’re gonna figure this out. ”

The wayward son would devote himself to therapy and also to science. He would turn Rancid all the way up and study all night long. He would be tenured at Stanford with his own lab, severing optic nerves in mice and noting what grew back.

Huberman has been in therapy, he says, since high school. He has, in fact, several therapists, and psychiatrist Paul Conti appears on his podcast frequently to discuss mental health. Therapy is “hard work … like going to the gym and doing an effective workout.” The brain is a machine that needs tending. Our cells will benefit from the careful management of stress. “I love mechanism, ” says Huberman; our feelings are integral to the apparatus. There are Huberman Husbands (men who optimize), a phenomenon not to be confused with #DaddyHuberman (used by women on TikTok in the man’s thrall).

A prophet must constrain his self-revelation. He must give his story a shape that ultimately tends toward inner strength, weakness overcome. For Andrew Huberman to become your teacher and mine, as he very much was for a period this fall — a period in which I diligently absorbed sun upon waking, drank no more than once a week, practiced physiological sighs in traffic, and said to myself, out loud in my living room, “I also love mechanism”; a period during which I began to think seriously, for the first time in my life, about reducing stress, and during which both my husband and my young child saw tangible benefit from repeatedly immersing themselves in frigid water; a period in which I realized that I not only liked this podcast but liked other women who liked this podcast — he must be, in some way, better than the rest of us.

Huberman sells a dream of control down to the cellular level. But something has gone wrong. In the midst of immense fame, a chasm has opened between the podcaster preaching dopaminergic restraint and a man, with newfound wealth, with access to a world unseen by most professors. The problem with a man always working on himself is that he may also be working on you.

Some of Andrew’s earliest Instagram posts are of his lab. We see smiling undergraduates “slicing, staining, and prepping brains” and a wall of framed science publications in which Huberman-authored papers appear: Nature, Cell Reports, The Journal of Neuroscience. In 2019, under the handle @hubermanlab, Andrew began posting straightforward educational videos in which he talks directly into the camera about subjects such as the organizational logic of the brain stem. Sometimes he would talk over a simple anatomical sketch on lined paper; the impression was, as it is now, of a fast-talking teacher in conversation with an intelligent student. The videos amassed a fan base, and Andrew was, in 2020, invited on some of the biggest podcasts in the world. On Lex Fridman Podcast, he talked about experiments his lab was conducting by inducing fear in people. On The Rich Roll Podcast, the relationship between breathing and motivation. On The Joe Rogan Experience, experiments his lab was conducting on mice.

He was a fluid, engaging conversationalist, rich with insight and informed advice. In a year of death and disease, when many felt a sense of agency slipping away, Huberman had a gentle plan. The subtext was always the same: We may live in chaos, but there are mechanisms of control.

By then he had a partner, Sarah, which is not her real name. Sarah was someone who could talk to anyone about anything. She was dewy and strong and in her mid-40s, though she looked a decade younger, with two small kids from a previous relationship. She had old friends who adored her and no trouble making new ones. She came across as scattered in the way she jumped readily from topic to topic in conversation, losing the thread before returning to it, but she was in fact extremely organized. She was a woman who kept track of things. She was an entrepreneur who could organize a meeting, a skill she would need later for reasons she could not possibly have predicted. When I asked her a question in her home recently, she said the answer would be on an old phone; she stood up, left for only a moment, and returned with a box labeled OLD PHONES.

Sarah’s relationship with Andrew began in February 2018 in the Bay Area, where they both lived. He messaged her on Instagram and said he owned a home in Piedmont, a wealthy city separate from Oakland. That turned out not to be precisely true; he lived off Piedmont Avenue, which was in Oakland. He was courtly and a bit formal, as he would later be on the podcast. In July, in her garden, Sarah says she asked to clarify the depth of their relationship. They decided, she says, to be exclusive.

Both had devoted their lives to healthy living: exercise, good food, good information. They cared immoderately about what went into their bodies. Andrew could command a room and clearly took pleasure in doing so. He was busy and handsome, healthy and extremely ambitious. He gave the impression of working on himself; throughout their relationship, he would talk about “repair” and “healthy merging.” He was devoted to his bullmastiff, Costello, whom he worried over constantly: Was Costello comfortable? Sleeping properly? Andrew liked to dote on the dog, she says, and he liked to be doted on by Sarah. “I was never sitting around him,” she says. She cooked for him and felt glad when he relished what she had made. Sarah was willing to have unprotected sex because she believed they were monogamous.

On Thanksgiving in 2018, Sarah planned to introduce Andrew to her parents and close friends. She was cooking. Andrew texted repeatedly to say he would be late, then later. According to a friend, “he was just, ‘Oh yeah, I’ll be there. Oh, I’m going to be running hours late.’ And then of course, all of these things were planned around his arrival and he just kept going, ‘Oh, I’m going to be late.’ And then it’s the end of the night and he’s like, ‘Oh, I’m so sorry this and this happened.’”

Huberman disappearing was something of a pattern. Friends, girlfriends, and colleagues describe him as hard to reach. The list of reasons for not showing up included a book, time-stamping the podcast, Costello, wildfires, and a “meetings tunnel.” “He is flaky and doesn’t respond to things,” says his friend Brian MacKenzie, a health influencer who has collaborated with him on breathing protocols. “And if you can’t handle that, Andrew definitely is not somebody you want to be close to.” “He in some ways disappeared,” says David Spiegel, a Stanford psychiatrist who calls Andrew “prodigiously smart” and “intensely engaging.” “I mean, I recently got a really nice email from him. Which I was touched by. I really was.”

In 2018, before he was famous, Huberman invited a Colorado-based investigative journalist and anthropologist, Scott Carney, to his home in Oakland for a few days; the two would go camping and discuss their mutual interest in actionable science. It had been Huberman, a fan of Carney’s book What Doesn’t Kill Us, who initially reached out, and the two became friendly over phone and email. Huberman confirmed Carney’s list of camping gear: sleeping bag, bug spray, boots.

When Carney got there, the two did not go camping. Huberman simply disappeared for most of a day and a half while Carney stayed home with Costello. He puttered around Huberman’s place, buying a juice, walking through the neighborhood, waiting for him to return. “It was extremely weird,” says Carney. Huberman texted from elsewhere saying he was busy working on a grant. (A spokesperson for Huberman says he clearly communicated to Carney that he went to work.) Eventually, instead of camping, the two went on a few short hikes.

Even when physically present, Huberman can be hard to track. “I don’t have total fidelity to who Andrew is,” says his friend Patrick Dossett. “There’s always a little unknown there.” He describes Andrew as an “amazing thought partner” with “almost total recall,” such a memory that one feels the need to watch what one says; a stray comment could surface three years later. And yet, at other times, “you’re like, All right, I’m saying words and he’s nodding or he is responding, but I can tell something I said sent him down a path that he’s continuing to have internal dialogue about, and I need to wait for him to come back. ”

Andrew Huberman declined to be interviewed for this story. Through a spokesman, Huberman says he did not become exclusive with Sarah until late 2021, that he was not doted on, that tasks between him and Sarah were shared “based on mutual agreement and proficiency,” that their Thanksgiving plans were tentative, and that he “maintains a very busy schedule and shows up to the vast majority of his commitments.”

In the fall of 2020, Huberman sold his home in Oakland and rented one in Topanga, a wooded canyon enclave contiguous with Los Angeles. When he came back to Stanford, he stayed with Sarah, and when he was in Topanga, Sarah was often with him.

When they fought, it was, she says, typically because Andrew would fixate on her past choices: the men she had been with before him, the two children she had had with another man. “I experienced his rage,” Sarah recalls, “as two to three days of yelling in a row. When he was in this state, he would go on until 11 or 12 at night and sometimes start again at two or three in the morning.”

The relationship struck Sarah’s friends as odd. At one point, Sarah said, “I just want to be with my kids and cook for my man.” “I was like, Who says that? ” says a close friend. “I mean, I’ve known her for 30 years. She’s a powerful, decisive, strong woman. We grew up in this very feminist community. That’s not a thing either of us would ever say.”

Another friend found him stressful to be around. “I try to be open-minded,” she said of the relationship. “I don’t want to be the most negative, nonsupportive friend just because of my personal observations and disgust over somebody.” When they were together, he was buzzing, anxious. “He’s like, ‘Oh, my dog needs his blanket this way.’ And I’m like, ‘Your dog is just laying there and super-cozy. Why are you being weird about the blanket?’”

Sarah was not the only person who experienced the extent of Andrew’s anger. In 2019, Carney sent Huberman materials from his then-forthcoming book, The Wedge, in which Huberman appears. He asked Huberman to confirm the parts in which he was mentioned. For months, Huberman did not respond. Carney sent a follow-up email; if Huberman did not respond, he would assume everything was accurate. In 2020, after months of saying he was too busy to review the materials, Huberman called him and, Carney says, came at him in a rage. “I’ve never had a source I thought was friendly go bananas,” says Carney. Screaming, Huberman threatened to sue and accused Carney of “violating Navy OpSec.”

It had become, by then, one of the most perplexing relationships of Carney’s life. That year, Carney agreed to Huberman’s invitation to swim with sharks on an island off Mexico. First, Carney would have to spend a month of his summer getting certified in Denver. He did, at considerable expense. Huberman then canceled the trip a day before they were set to leave. “I think Andrew likes building up people’s expectations,” says Carney, “and then he actually enjoys the opportunity to pull the rug out from under you.”

In January 2021, Huberman launched his own podcast. Its reputation would be directly tied to his role as teacher and scientist. “I’d like to emphasize that this podcast,” he would say every episode, with his particular combination of formality and discursiveness, “is separate from my teaching and research roles at Stanford. It is, however, part of my desire and effort to bring zero-cost-to-consumer information about science and science-related tools to the general public.”

“I remember feeling quite lonely and making some efforts to repair that,” Huberman would say on an episode in 2024. “Loneliness,” his interviewee said, “is a need state.” In 2021, the country was in the later stages of a need state: bored, alone, powerless. Huberman offered not only hours of educative listening but a plan to structure your day. A plan for waking. For eating. For exercising. For sleep. At a time when life had shifted to screens, he brought people back to their corporeal selves. He advised a “physiological sigh” — two short breaths in and a long one out — to reduce stress. He pulled countless people from their laptops and put them in rhythm with the sun. “Thank you for all you do to better humanity,” read comments on YouTube. “You may have just saved my life man.” “If Andrew were science teacher for everyone in the world,” someone wrote, “no one would have missed even a single class.”

Asked by Time last year for his definition of fun, Huberman said, “I learn and I like to exercise.” Among his most famous episodes is one in which he declares moderate drinking decidedly unhealthy. As MacKenzie puts it, “I don’t think anybody or anything, including Prohibition, has ever made more people think about alcohol than Andrew Huberman.” While he claims repeatedly that he doesn’t want to “demonize alcohol,” he fails to mask his obvious disapproval of anyone who consumes alcohol in any quantity. He follows a time-restricted eating schedule. He discusses constraint even in joy, because a dopamine spike is invariably followed by a drop below baseline; he explains how even a small pleasure like a cup of coffee before every workout reduces the capacity to release dopamine. Huberman frequently refers to the importance of “social contact” and “peace, contentment, and delight,” always mentioned as a triad; these are ultimately leveraged for the one value consistently espoused: physiological health.

In August 2021, Sarah says she read Andrew’s journal and discovered a reference to cheating. She was, she says, “gutted.” “I hear you are saying you are angry and hurt,” he texted her the same day. “I will hear you as much as long as needed for us.”

Andrew and Sarah wanted children together. Optimizers sometimes prefer not to conceive naturally; one can exert more control when procreation involves a lab. Sarah began the first of several rounds of IVF. (A spokesperson for Huberman denies that he and Sarah had decided to have children together, clarifying that they “decided to create embryos by IVF.”)

In 2021, she tested positive for a high-risk form of HPV, one of the variants linked to cervical cancer. “I had never tested positive,” she says, “and had been tested regularly for ten years.” (A spokesperson for Huberman says he has never tested positive for HPV. According to the CDC, there is currently no approved test for HPV in men.) When she brought it up, she says, he told her you could contract HPV from many things.