Writers and Depression: How to Keep Writing Through the Darkness

by Miriam Nicholson | 61 comments

I feel the chains pull me down as I sink into the dark. Fighting it with fear pulsing through me till despair claims my heart, I can't get out, I can't move, I'm trapped in depression. Writers and depression: not a good combination.

Hey everyone. I'm back, and it's been three more years since my post on self-doubt . Two years, but I've been writing so I guess it's a victory of sorts. However, it has been the hardest thing to keep going.

Through those two years, I've found out that I have anxiety and depression, had to move away from home with no resources, and come to terms with the fact that my childhood was filled with passive aggression and emotional abuse. It has been the hardest thing I've ever had to face, and I now find it affecting my writing.

Writers and Depression and Anxiety: An Endless Cycle

Some people might shrug that off—anxiety, depression, who cares? Just stop being anxious or depressed. What they don't realize is it’s not something you can shrug off. Heck, if you could you’d have done that a long time ago. Why make yourself suffer if it was that easy to get rid of? It affects everything, and for me writing was hit the hardest.

Every time I pick up a writing piece or think about what I want to write next, it comes like a thief in the night to stab me with doubt. “What are you doing? Haven't we already confirmed this? You aren't a writer. You can't do it,” it says and laughs at my pain, my anguish, as I clutch my wounds and try to keep walking.

I am wrapped in chains as the depression follows, each thought adding to my already impossible weight. It's not too long before the wound and weight make me fall, leaving me motionless and alone. I can't get up, and even if I could the effort is too much.

My anxiety and depression watch me and laugh, dancing around me in glee. Everything within me wants to give up, give in, and vanish, but one spark remains in my heavy heart. I focus on it and somehow keep moving because of the spark that got me into the game, the spark that tells me I can't give up. And so, I trudge on with great effort, one step at a time.

Anyone who’s been in it knows the cycle. Rinse and Repeat. A endless cycle of paralyzing doubt, fear, and hopelessness. And yet here we stand, still here, hollow survivors.

Some days it's hard to even get to the writing point, some days it's hard to wake up, and some days it's hard to go to bed. I push on. The only way to fight it is to do what it says you can't —a task so heavy and so great that it is almost bitter sweet.

Sure, you could write something and banish doubt for a time, but it's bound to return when you look at it again. When you start to see the imperfections. The only way to fight it is to keep going.

Writing Through the Pain

Pain is powerful. It breaks us, tears us down, leaving behind tattered emotions and shredded dreams. It’s hard to face; it’s just easier to let it stay, hidden in your soul. Oft times we smile it away, but deep inside it remains.

That is my everyday now. Most days I can't write. Most days that fact drags me deeper into depression. And when depression takes a break, anxiety comes right after, using its sharp knives to convince me to cower from the page and not write at all.

When I get like this, the only thing I can do to break the cycle is vomit on the page. I never know what's going to come out, and starting to write is the hardest part. My pain spews out on the page like blood. I let the words flow; I refuse to look at them.

Sometimes you just have to write.

It doesn't have to be published, it doesn't have to be in a piece you're working on. The point is to get the doubts on the page, and only then can you start to counter them.

Fear Flees From Action

I can see your eyes rolling. I’m sure you’ve heard this before. I can see your yes buts . It’s okay. Action is hard. A four-letter word that makes you shake and curl up inside. Fear so powerful that it’s a presence on your shoulder—how could it just go away?

I’ve been there. I never believed the stories that it fled from action, at least not consciously. Till the one day it just hurt too much to not write. It had been a rough day, anxiety and depression pulling me to my wit's end, but I hadn’t said a word. I was trained out of communicating painful things, but this time it was just too much.

I didn’t want to open a blank page; I didn’t want to start writing; fear pulled at me—but my pain spoke louder. I opened the doc and with trembling fingers started writing. It quickly became nearly gibberish as I wrote with tears flowing down my face, but it felt so good. Anger frustration grief all being taken off my shoulders and thrown on the page. Fear completely gone from my mind within the first paragraph.

I'd like to urge you guys to write anyway. It's going to be hard, it's going to hurt, and in some cases it'll make you cry. Write it anyway. You can't fix a blank page.

Once you write, reward yourself. Anything from watching a favorite movie, to eating a candy bar, or treating yourself in any other way. This is important. Because if you don't reward yourself the doubt can just as easily say that what you made was a fraud. By rewarding yourself you acknowledge that you did something good, something worthwhile.

Don’t allow yourself to feel guilty about a job well done. You earned it.

You Can Do It

I’m not going to start this saying it’ll be easy. It won’t be. It might be the hardest thing you ever do, but of course facing fear is always scary. It was hard to let myself accept what my parents were, and harder still to realize I had anxiety and depression. But I’m still here, still fighting the fight. You can too.

You can take control back in your life. No matter how deep you go, you can make it through even if you're not out yet. You have the power to get up anyway. No matter how many times you’ve done it before, you can do it again and again.

Even if your body gives up on you, even if you’ve had enough, even if it takes all your effort to get out of bed. You can do it. As long as you don’t give up on yourself, nothing can stop you. Even if you don’t believe that and only long to, that is enough. You are enough. All it takes is one step, one choice, one word.

All you need to do is start.

Have you ever experienced anxiety or depression in your writing? How did you overcome it? Let me know in the comments .

For fifteen minutes , I want you to vomit on the page everything that is keeping you from writing, whatever project you are working on. Or, you can simply describe your experience with writing and mental illness. Don't stop to edit; just try to write as much as you can. I won't make you share that piece in the comments if you don't want, although you're more than welcome to. Happy writing!

Miriam Nicholson

Miriam is a dreamer filled with passion for her writing. You can read more of it on her website . You can also connect with her on Facebook and email her .

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Use Writing Therapy to Release Negative Emotions and Trauma

Whether it’s lyrics or journaling—expression through writing can be cathartic

Ayana is the Associate Editor at Verywell Mind, where she aims to publish mental health content that is both engaging and of high quality.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/verywell-Ayana-Underwood1-b3c1567c2c4c4480b6eab25cabb974b1.jpg)

Yolanda Renteria, LPC, is a licensed therapist, somatic practitioner, national certified counselor, adjunct faculty professor, speaker specializing in the treatment of trauma and intergenerational trauma.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/YolandaRenteria_1000x1000_tight_crop-a646e61dbc3846718c632fa4f5f9c7e1.jpg)

Verywell / Julie Bang

- What to Know About Writing Therapy

The Major Benefits of Writing Therapy

- How to Get Started With Expressive Writing

Every Friday on The Verywell Mind Podcast , host Minaa B., a licensed social worker, mental health educator, and author of "Owning Our Struggles," interviews experts, wellness advocates, and individuals with lived experiences about community care and its impact on mental health.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts / Amazon Music

Putting pen to paper feels a bit like an anomaly in a world obsessed with texting, tweeting, and sliding into people’s DMs. But let’s try something different. The next time you’re in your Notes app, give your thumbs a break and grab a pen and piece of paper instead. If you don’t have any paper handy, grab that Starbucks receipt and start writing whatever you were about to type. See how it feels.

It might feel a bit awkward at first, especially if you haven’t had to physically write anything down in a long while. But as you keep writing, you may feel really engaged with the words you’re jotting down. Tapping letters on a screen isn’t the same as drawing out each letter of every word. Writing things down will inherently bond you to the words you write. And because of that, writing becomes quite powerful for the psyche . Aside from being a feel-good activity, writing can also let us process negative emotions and trauma in what turns out to be a pretty soul-cleansing experience.

In fact, singer/songwriter and season three winner of The Voice, Cassadee Pope , seconds this. Pope, who's been in the music industry since she was 11 years old, has been pretty open about her mental health struggles—from bad breakups to the emotional impact of her parent’s divorce. Pope told Minaa B., LMSW , host of The Verywell Mind Podcast, “I needed an outlet with everything that was happening with my family. So that was really what I leaned on most, was songwriting.”

Now, you don’t have to be a gifted songwriter to reap the benefits of writing, but let's talk about why writing can be so good for your mental health.

At a Glance

Writing can be a powerful therapeutic tool. Getting your thoughts down can help you understand them and process them more effectively than keeping them all in your head. People who use writing therapy report better overall mood and fewer depressive symptoms. If you’re struggling with a mental health condition and need to vent your frustrations—consider making a journal your new BFF.

What to Know About Writing Therapy (Write This Down)

Writing therapy (aka emotional disclosure or expressive writing) is pretty much exactly what it sounds like. It involves using writing of any kind, like creative writing, freewriting, and poetry, as a therapeutic tool. Writing therapy can be especially for those who are more withdrawn or have trouble opening up to others.

Writing therapy can be so beneficial to our mental health because it’s basically a form of venting. You know how good it feels to come home after a long day of work and go on and on about how much you dislike that one coworker for a reason you can’t even put your finger on. Or when you spill all of your dating frustrations to your bestie over the phone. It’s a nice release of stress. You can release stress in a similar way when you write, too. Just pretend that piece of paper is your therapist, closest confidante, or even yourself.

No one else has to know whatever you choose to jot down (or rage-write about). Your journal or diary is your personal safe haven, and your innermost thoughts are safe on those pages.

Research shows that writing about painful experiences can even improve your immune system. Getting all of your thoughts out on paper is a big stress reliever. It’s also known that trying to suppress negative emotions can be detrimental to your overall well-being, so verbal release may only help you in the long run. Another advantage of writing therapy is that it gives your emotions and thoughts some structure. For instance, my therapist knows I love writing—especially writing poetry. So, when I was dealing with a particularly traumatic time in my life, she told me that my next few homework assignments would be to write poetry about my feelings. Because poetry is a form of creative writing, I had to really think about the diction and imagery I wanted to convey in the poems.

As a result, I really had to unpack my feelings so that my poem would paint a clear picture of what I was going through. I worked on the poem each night before bed and had it ready for my next weekly session.

The next day, I hopped online to meet with my therapist and tell her I had completed my assignment. In response, she asked me to read it aloud. What?! I quickly grew nervous since I was not expecting that. But, considering she’s never led me astray, I reluctantly recited my poem. It was an emotional experience, and my voice audibly cracked a few times, but it felt really good—euphoric, even. So when Pope says that singing her lyrics is "cathartic," I completely get it. She says her singing can be a bit “disarming” because “ I’m believing every word so intensely, and I feel them so intensely.”

So, not only does writing release some deep-seated feelings, orating them breathes life into them. There’s this particularly beautiful Chinese proverb that says: ‘I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I write and I understand.’ Once our thoughts are written down, we can see them in front of us, through this practice they become real. Then, we can dig in and unpack what it all means to us.

Other Benefits of Writing Therapy

If you’re still not convinced about the power of writing, here are some other amazing benefits of writing to take note of (pun intended):

- Lowered blood pressure

- Reduced anxiety and depression symptoms

- Improved cognition

- Increased antibody production

- Better overall mood

Ready to Get Started With Expressive Writing?—Here’s How

The great thing about writing is that it can be about anything you want. There are zero restrictions on what you can say. If you’ve had an upsetting experience or need to release some frustrations about daily stressors, try writing about it.

Pope talks about how she’s been using songwriting to get more authentic about her life as of late. In fact, she was kind enough to dish on the details about a new song of hers that’s set to release soon titled “Three of Us.” In this track, she details what it’s like being the “third wheel” when you’re in a relationship with someone who’s dealing with a substance use disorder : “It's about me, you, and the drugs.” In describing the lyrics, she says, “It's probably the most revealing song I've ever released.”

Now, if you’ve already got an experience you want to write about, feel free to get started when you’re alone and in a private space. But if you don’t know where to start, here are some prompts to start flexing your writing muscles.

Writing Prompts to Help You Get to Know Yourself Better

When you’re ready, get something to write with and a blank sheet of paper. Here are some prompts you can use to get started:

- What does the perfect day look like for you? Think about the activities you’d engage in and who you would be spending your time with. Try engaging your five senses to dive deep into your imagination.

- Write a story about the last time you were embarrassed. This time, reframe the experience into a positive one where you learn something new about yourself.

- Think about the best piece of advice you've ever received from someone. How has it helped to shape your life?

- Write a song or a poem about what it’s like to eat your favorite dessert. Consider the flavors, textures, and how you feel when you eat this specific treat. Where are you eating it? Did someone special make it for you, or did you make it yourself?

- What does self-love really mean to you? Who taught you what loving yourself looks like? What have you learned to embrace about yourself?

- If you’ve experienced a painful event, free-write about it. Don’t worry about grammar, spelling, or legibility—just write whatever comes to mind. You can even draw if that helps.

These writing prompts should get you more comfortable with expressing your feelings. Once you make sense of your own experiences, you might be ready to share them with friends, significant others, and other people you trust. If you have a therapist or plan to start therapy, you’ll already have some material to share that you can explore in the session.

When you connect through storytelling, you begin to strengthen your support network. Pope shared how much she leaned on her friends after a bad breakup. “ If you have community, lean into it and don't be afraid that someone's gonna judge you if you made a mistake or a bad decision, a poor decision, don't be afraid of that. It's so much more healthy to just let it out,” she says.

Pope also cautions that doing this can also reveal the people who accept you just as you are—flaws included: “ If somebody judges you or tries to make you feel bad about it, then OK, great. That one person is not a safe space for you.”

What This Means For You

If you’re uncomfortable opening up to your friends this way, that’s perfectly fine. Never feel pressured to share some uncomfortable thoughts or experiences. You can keep them to yourself in your journal or reserve them all for your therapist.

Writing is a good place to start when you want to better understand who you are and how your experiences have affected you. If you’re struggling with processing your emotions and feel that you need someone to talk to, consider seeing a mental health professional.

Mugerwa S, Holden JD. Writing therapy: a new tool for general practice? . Br J Gen Pract . 2012;62(605):661-663. doi:10.3399/bjgp12X659457

American Psychological Association. Writing to heal .

Krpan KM, Kross E, Berman MG, Deldin PJ, Askren MK, Jonides J. An everyday activity as a treatment for depression: the benefits of expressive writing for people diagnosed with major depressive disorder . J Affect Disord . 2013;150(3):1148-1151. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.065

By Ayana Underwood Ayana is the Associate Editor at Verywell Mind, where she aims to publish mental health content that is both engaging and of high quality.

Journaling For Mental Health: How To Do It Effectively To Improve Mood And Well-Being

Here's what the science says.

“Journaling can be a powerful way to organize your thoughts, feelings, and ideas, leading to increased self-awareness, self-discovery, and growth,” says Jaci Witmer Lopez, PsyD, a licensed clinical psychologist based in New York City. “In my practice, I've seen firsthand how regular journaling can transform lives.”

Maybe you've kept a fitness journal in the past to help you stay on track toward your wellness goals, or you currently have a gratitude journal to stay grounded. There are travel journals to help you document your adventures, and if you’re less artistically inclined, there are even journaling apps to help you stay mindful on the go. Below, experts share the benefits of journaling for mental health, how to start one yourself, and specific writing prompts for inspiration.

Meet the experts: Jaci Witmer Lopez, PsyD , is a clinical psychologist based in New York City. Marc Campbell, LMHC , is a licensed therapist based in Orlando, Florida, and the author of I Love My Queer Kid .

Common Benefits Of Journaling

Apart from having a dedicated place for juicy diary entries, there are several general benefits of journaling. The practice has been shown to help people process stressful events, according to a study published in Annals of Behavioral Medicine . In another study about college students, researchers found that journaling may improve self-efficacy —in other words, it can help you believe in yourself. Writing has even been studied as a behavioral intervention for children—so if you have kiddos at home, encouraging them to write may not be such a bad idea.

Common benefits of journaling include:

- Finding inspiration

- Creative expression

- Tracking your goals

- Fun freewriting

- General reflection

- Brainstorming ideas

5 Mental Health Benefits Of Journaling

Apart from its general benefits, here's how journaling can impact your mental health, specifically, according to experts.

1. It can help you process (and learn from) your emotions.

“Remembering the events from your day—both the ups and the downs—can help your brain practice processing and regulating your emotions,” says Marc Campbell, LMHC, a licensed therapist based in Orlando, Florida. For instance, if you’re feeling rejected from a recent breakup or you're burned out at work, writing about how you feel and reading it back to yourself can help you process the difficult emotions. Journaling can also help you recognize certain patterns, practice more acceptance, and have more empathy for yourself, Campbell says.

2. It can help you heal from traumatic events.

Journaling can significantly impact your ability to process and heal from trauma, Lopez says. “ Research has shown that writing can reduce symptoms of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),” she says. “When you write things down as opposed to just thinking about them, you hold yourself accountable to reframing or changing your narrative.” Although the mental health effects of trauma won’t disappear by simply writing down how you feel, journaling can be a helpful practice in addition to seeking therapy and trauma treatment .

3. It may help you manage anxiety and depression.

Anxiety and depression are among the most commonly cited mental health struggles in America, per the American Psychological Association (APA). And although having a writing practice won't cure these conditions overnight, journaling may have the potential to decrease depression and anxiety and improve resilience over time, according to a recent study . Plus, if you’re struggling to find meaning in everyday life or you feel generally disengaged—both of which are common experiences when facing mental health challenges— some studies suggest that journaling may help.

4. It can help you track your therapy progress.

If you're seeing a therapist right now, journaling can help you check in with yourself daily or weekly about how it’s going—or even help you hold yourself accountable for certain behaviors you’d like to change, Campbell says. “Through the process of journaling, you can reflect on past entries and potentially learn about any patterns you have,” he says.

You can also use a journal to reflect on what, exactly you speak about during your therapy sessions and begin to process how you’re feeling about it, Lopez adds. An added benefit? One day, you can look back at your journal and celebrate how far you've come.

5. It can help you practice self-compassion.

Whether you're dealing with a specific mental health issue or you're simply feeling overwhelmed, negative self-talk, shame, and embarrassment are common. It can be difficult to be kind to yourself, however, practicing self-compassion can go a long way, experts say. A recent study in the American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology found that daily journaling as a mindfulness practice led to increased levels of self-compassion, and another study on registered nurses found that journaling can boost compassion and help manage burnout.

How To Start Journaling For Mental Health

If you aren't someone who spilled your heart out in a childhood diary, don't worry—journaling can be as simple as jotting things down on your phone, in a notebook, or responding to a specific prompt to get inspiration (more on that soon).

There’s no “right” or “wrong” way to journal, but it should be a personal process, Campbell says. “I recommend starting journaling in the way that feels most authentic to you. If you prefer pen and paper, start with that. If you prefer typing things out in your notes app, that works, too. If you aren’t sure, try both and more—a laptop or even typewriter if you’re feeling adventurous,” he says. Also, writing for mental health is personal, but you shouldn't feel pressured to document your whole life story all at once (unless you want to).

Whether you incorporate journaling into your morning routine or you attempt five minutes before bedtime to free-write, experts recommend starting slow. “If you're new to journaling, my advice is to start small and be patient with yourself. Set aside just a few minutes a day to begin with, and gradually increase the time as you build the habit. It’s important to find a method that you'll stick with consistently," Lopez says. Try to pace yourself and make the practice as manageable as possible so that it becomes a habit formed over time, she adds.

10 Journal Prompts For Mental Health

- What was the highlight of my day?

- What was a lot moment of my day?

- What's a challenge I'm facing right now?

- What people, places, or things am I grateful for and why?

- Who is someone that's inspired me lately and why?

- What are three things I'm proud of myself for, and why?

- What is a small act of kindness I can do for myself this week?

- What is one limiting belief I have about myself? (And is there a way I can begin to reframe it)?

- Describe something you are struggling with. Then, read it from the perspective of someone you care about. What would they have to say about it?

- If I could change an aspect of my mental health and well-being right now, what would it be and why?

When it comes to journaling for mental health, consistency is key. Whatever method, prompt, or format you choose, your mental health will thank you.

Best Journals For Mental Health

The Five Minute Journal

Looking for a simple, sleek journal that will help you practice more mindfulness and gratitude? This popular option might be a good fit for you. It encourages you to cultivate a sense of calm for just five minutes a day, but there are plenty of helpful tools packed into the journal itself—like prompts, daily highlights, weekly challenges, affirmations, and more. If you're brand new to journaling for mental health, this one provides clear cues and outlines to help you self-reflect and feel more confident. Plus, it's aesthetically pleasing. What could be better?

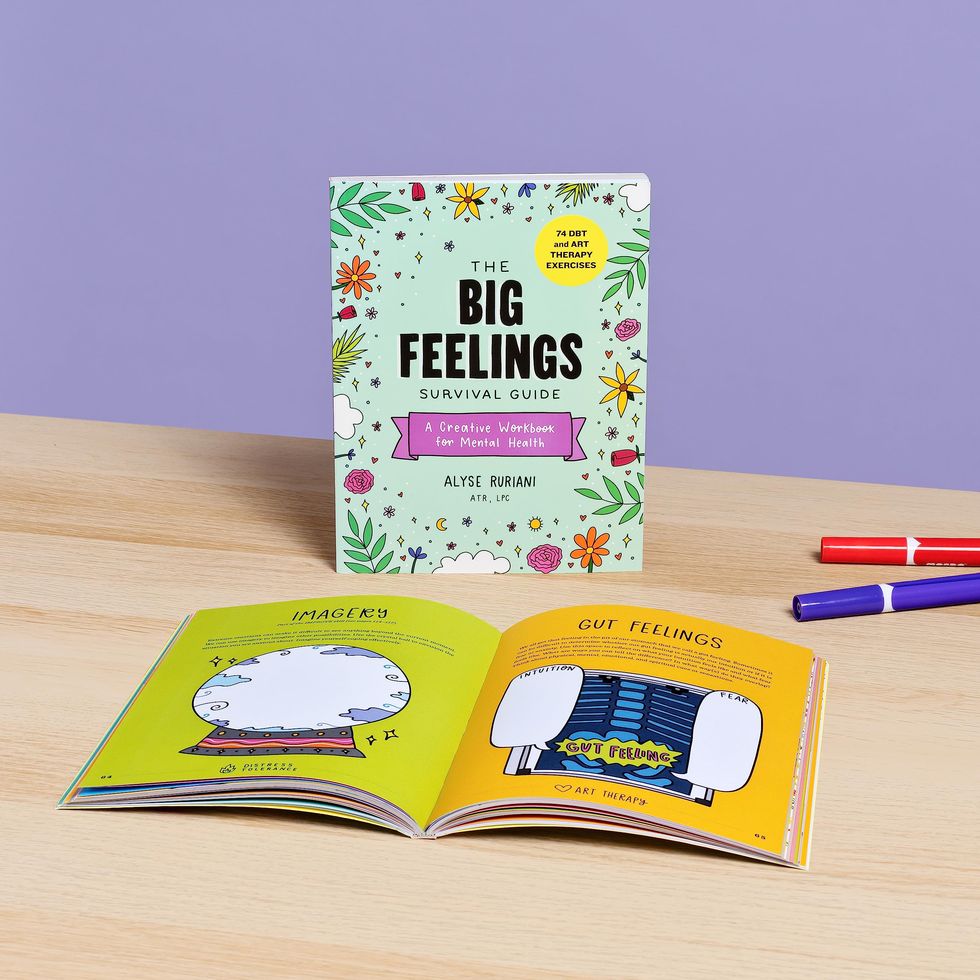

The Big Feelings Survival Guide

This colorful, activity-filled workbook by licensed art therapist Alyse Ruriani, LPC, is a great option if you're ready to dive into mental health in a fun, accessible, yet meaningful way. The workbook includes practical and creative activities that are all rooted in dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), which, ICYMI, is a revolutionary treatment that helps people move through emotions. Not only will you gain major insight about your mental health journey, but the workbook itself is super bright and engaging—the helpful illustrations and eye-opening exercises are sure to help you reflect and gain inspiration.

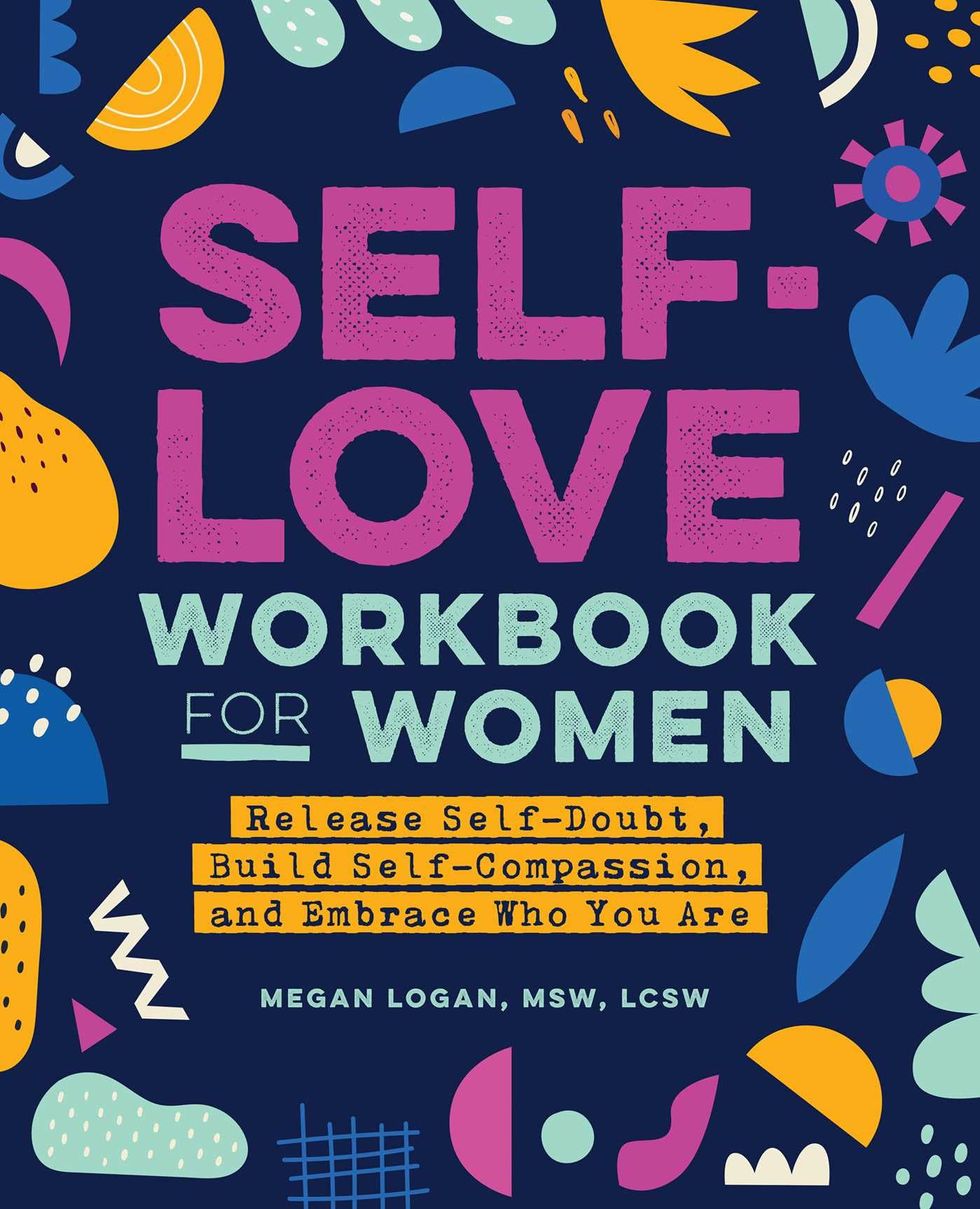

Self-Love Workbook for Women

This self-love workbook by therapist Megan Logan, LCSW, is uniquely designed to help you release self-doubt and have more self-compassion. The journal includes quizzes, writing prompts, and fun activities to help you cultivate more self-love, like writing a message to your younger self and making a "happy playlist." You'll also find empowering affirmations for those days when your mental health isn't so good—plus, the journal provides helpful resources for goal-tracking, identifying emotions, and embracing who you are.

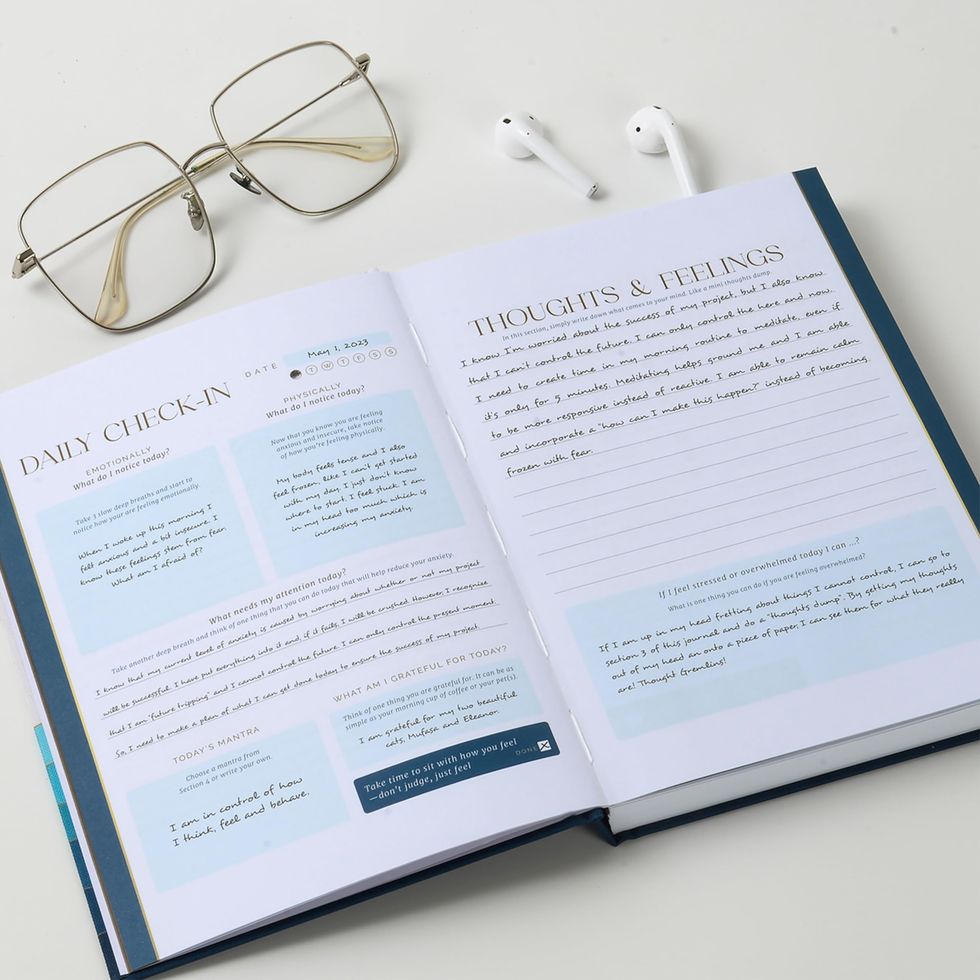

90-Day Mental Health Journal

This easy-to-follow journal encourages you to care for your mental health in a holistic way. If you're dealing with stress, anxiety, or uncertainty about the future, the journal claims to help you self-reflect and gain self-awareness while focusing on the power of the present moment. This journal is ideal for anyone who wants to breathe, reconnect with themselves, and cultivate more mindfulness. It comes with grounding activities and daily check-ins to help you keep track of your emotions—and understand their roots.

Lexi Inks (she/her) is a lifestyle journalist based in Jacksonville, Florida. She has reported on countless topics, including sexual wellness, astrology, relationship issues, non-monogamy, mental health, pop culture, and more. In addition to Women’s Health, her work has been published on Bustle, Cosmopolitan, Well + Good, Byrdie, Popsugar, and others. As a queer and plus-size woman with living with mental illness, Lexi strives for intersectionality and representation in all of her writing. She holds a BFA in Musical Theatre from Jacksonville University, which she has chosen to make everyone’s problem.

Mental Health

20 Best Guided Journals For Your Wellness Journey

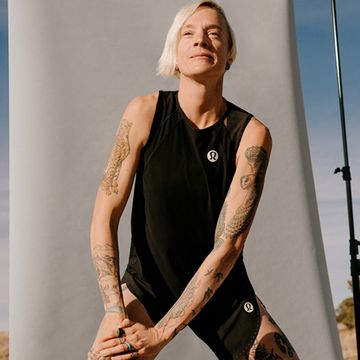

‘I Had SCAD As A Healthy, Fit 36-Year-Old Woman’

'How I Trained For An Ironman With Parkinson's'

WNBA's Diamond DeShields Reflects On Spinal Tumor

'I Did 7 Marathons In 7 Days With Type 1 Diabetes'

'Ultra-Running Helps Me Cope With Lupus Symptoms'

‘What It's Like To Be A Dancer With Hearing Loss’

'How I Progressed To Deadlift 375 Pounds'

What Is Anticipatory Grief?

What Is Body Neutrality, Exactly? Experts Weigh In

Why Don’t We Prescribe Exercise For Mental Health?

- About rtor.org

- Advisory Board

- 2023 Fact Card

- About the Resource Specialists

- Crisis & Recognition

- Understanding & Diagnosis

- Directory of Family-Endorsed Providers

- Getting Help: Treatment & Services

- Recovery Resource Collection

- Best Practices Mental Health Papers

- Recovery & Hope

- Young Adult Resources

- BIPOC Mental Health Fact Sheet

- BIPOC Mental Health Resources

- All Articles

- The Family Side

- Close to Home: The Fairfield County Mental Health Blog

- Contact a Resource Specialist

- Guest Blog With Us

Our Latest Blogs

Provider search, wordpress meta data and taxonomies filter, how writing can boost emotional intelligence and improve mental health.

According to experts, one in every six people experiences a mental health problem at least once a week. It can be one of your friends, colleagues, or even you. For many people, discussing their mental health is taboo. However, it is frequently a debilitating daily struggle with a series of failures and battles with an unseen opponent. Find out about a practice that will help you improve your psycho-emotional state and reduce the frequency of your depression and anxiety.

There are numerous methods for reducing anxiety and stress , relieving pressure on the mind, and achieving internal harmony. Some people turn to breathing exercises and yoga , while others seek less typical ways to improve their mental health.

You might be surprised to learn that writing practice is one of the most effective ways to relieve emotional stress and improve mental health. We’re not talking college essays or business reports – it is more about freely expressing yourself on paper.

How Does Writing Improve Mental Health?

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, surveys revealed that nearly 40% of adults in the United States experience loneliness on a regular or occasional basis. Loneliness and social isolation can exacerbate symptoms of depression , anxiety, and other mental illnesses.

Writing, among other creative activities, has been shown to increase meaningful social connections with others, reduce stress, and assist people in understanding and controlling their emotions.

Why Is Writing Beneficial for Mental Health?

Several studies have found that writing practice can help people’s mental health. Furthermore, one of the skills that the labor market is looking for these days is the ability to clearly express and arrange thoughts. Honing your writing skills can help you improve your well-being and open up new career opportunities.

Here are the top five reasons why writing is good for your mental health:

It Makes You Happier

According to Southern Methodist University research , writing about future goals makes people happier and can help people who work in challenging environments to cope with stress.

Writing Helps You Clear Your Mind

It allows you to clear your mind by writing down your thoughts, emotions, feelings, and ideas. This can be accomplished by keeping a journal, a diary, or simply writing everything down.

It Aids in Being More Mindful

It is a powerful mindfulness technique that allows you to better recognize your emotions and stop restraining yourself from feeling better (even if you are writing about neutral topics).

Writing Practices Improve Your Emotional Well-Being

It improves your ability to manage depression and other mental health conditions by helping you recognize your emotions (directly related to the previous point). Writing is ideal for improving your emotional well-being.

It Makes You More Resilient

Various forms of creative writing (writing down thoughts, ideas, experiences, and feelings, as in a diary) have been shown in studies to help people cope with stressful situations at work. It is natural for our imagination to exaggerate many details, inflate problems, and turn a minor annoyance into a major issue.

Putting the problem down on paper will allow you to properly assess its scope and identify different actions required to resolve it. A quick response to the problem and the planning of solutions saves time and effort while helping you quickly return to work.

Writing Allows You to Hone Your Expressive and Communication Abilities

It is very disappointing when you cannot condense your thoughts and provide a clear answer to a question posed. Regular written exercises aid in emotional and intellectual gathering of information, allowing people to communicate and express complex ideas more effectively. Practice writing helps you overcome a limited vocabulary and enables you to turn what sounds good in your head into ideas that sound just as good when you put them down on paper.

It Improves Your Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence (EQ) is the ability to recognize, comprehend, and evaluate one’s own and other people’s emotions. It enables better mental health, increased happiness, and more effective leadership. People with higher EQ make better writers, but you can also boost your EQ through writing.

Here are five ways to boost your emotional intelligence:

- Recognize and tune into your own emotions. You must first be aware of your emotions in order to control them. Monitoring and examining your emotions, as well as your triggers and activation points, will help you manage them more effectively in the future.

- Seek to comprehend the perspectives of others . Pay close attention to people’s emotions, put yourself in other people’s shoes, and try to imagine what they are thinking and feeling, as well as how they came to their conclusions. You will not only gain a broader perspective, but you will also stretch your own.

- Develop communication skills. Understanding people’s emotions and the intentions behind the information exchanged through verbal and nonverbal communication is essential for effective communication.

- Work on building connections with people. Learning to connect with others is an essential part of developing EQ. Start by listening, showing interest, and making others feel at ease if you are shy or uncomfortable.

- Practice emotional control. Once you are aware of your own emotions, you must learn to control them and respond appropriately to the feelings of others. Try to avoid triggers that make others and you nervous. Breathing exercises can help you relieve stress and prevent emotional outbursts. Learn from others how to respond calmly and constructively in specific situations.

Improving your emotional intelligence will help you in both your personal and professional relationships. Furthermore, it will allow you to understand yourself and others better and find the appropriate tools for effective interactions.

Final Thoughts

As you can see, writing down your feelings is one of the best ways to understand them better. If you suffer from stress or depression, expressive writing can help you gain control of your emotions, get to the root of the problem, and focus on resolving it.

The benefit of writing is that it allows you to focus on one thing while clearing your mind of everything else interfering with your ability to find a solution. Write every day to better understand yourself, your actions, and your behavior.

Get our latest articles direct to your mailbox.

Join our mailing list for more articles written by family members, people with lived experience, and mental health professionals..

About the Author : Janice Gosney is a professional writer with years of experience who works for Writing Judge and Best Writers Online . She is primarily interested in such topics as personal growth, wellness, and motivation.

In her free time, Janice is a passionate traveler and bike rider.

Photo by Brad Neathery on Unsplash

The opinions and views expressed in any guest blog post do not necessarily reflect those of www.rtor.org or its sponsor, Laurel House, Inc. The author and www.rtor.org have no affiliations with any products or services mentioned in the article or linked to therein. Guest Authors may have affiliations to products mentioned or linked to in their author bios.

Recommended for You

Why Games Celebrating Cultural Diversity Matter More Than Ever Now

Finding Purpose Living with Treatment-Resistant Mental Health Conditions

How to Protect Children from the Negative Influence of Drugs and Alcohol Use on Social Media

- Recent Posts

- Why Games Celebrating Cultural Diversity Matter More Than Ever Now - March 28, 2024

- Finding Purpose Living with Treatment-Resistant Mental Health Conditions - March 21, 2024

- How to Protect Children from the Negative Influence of Drugs and Alcohol Use on Social Media - March 18, 2024

Guest Author for www.rtor.org

Leave a reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Stay Up to Date

Fill out the form to get close to home in your inbox..

- First Name *

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Writing Can Help Us Heal from Trauma

- Deborah Siegel-Acevedo

Three prompts to get started.

Why does a writing intervention work? While it may seem counterintuitive that writing about negative experiences has a positive effect, some have posited that narrating the story of a past negative event or an ongoing anxiety “frees up” cognitive resources. Research suggests that trauma damages brain tissue, but that when people translate their emotional experience into words, they may be changing the way it is organized in the brain. This matters, both personally and professionally. In a moment still permeated with epic stress and loss, we need to call in all possible supports. So, what does this look like in practice, and how can you put this powerful tool into effect? The author offers three practices, with prompts, to get you started.

Even as we inoculate our bodies and seemingly move out of the pandemic, psychologically we are still moving through it. We owe it to ourselves — and our coworkers — to make space for processing this individual and collective trauma. A recent op-ed in the New York Times Sunday Review affirms what I, as a writer and professor of writing, have witnessed repeatedly, up close: expressive writing can heal us.

- Deborah Siegel-Acevedo is an author , TEDx speaker, and founder of Bold Voice Collaborative , an organization fostering growth, resilience, and community through storytelling for individuals and organizations. An adjunct faculty member at DePaul University’s College of Communication, her writing has appeared in venues including The Washington Post, The Guardian, and CNN.com.

Partner Center

Creative Writing and the Psyche: Antidote to Depression

The threat of making art: one writer's journey, part 2..

Posted August 26, 2020

I came to writing late in life, and, as a result, I live life with the wind at my back. After several professional detours, including teaching, counseling, and currently a clinical practice in psychology, I returned in my early forties to poetry, my first love at 14.

More specifically, however, I came to writing poetry from the depths of a serious clinical depression . I had come to that place in life where I had everything I had longed for. I was married to a wonderful man whom I deeply loved and trusted; we had given birth to an adored son; I had finished my doctorate and established a robust clinical practice. I even had two wonderful homes — a rambling apartment and a house in the woods. I was deeply blessed.

At the same time, my good friend, Janice, was equally successful in her own quest for her fullest life — just one year behind me in her doctoral studies with two beautiful daughters and a devoted husband. President of her local Board of Education and Director of Guidance and Counseling at a prominent high school, she had just discovered a latent talent for tennis, which she dove into with vigor and delight. She was literally at the top of her game. The third member of our triumvirate was Kathy, a brilliant and zesty life force who more than filled up a room with her laughter and intelligence . All our meetings were celebrations. No one was more proud of us than we were of each other. We were family and they, my sisters.

Then Janice was diagnosed with kidney cancer. She was dead in less than four months.

Kathy and I were devastated. I fell into a depression so deep that I could not get out of bed. I reveled in nothing and no one. I cared for nothing and no one. Worst of all, I felt nothing when I looked at my glorious 2-year-old son. This terrified me. As a clinician, I knew how seriously sick I was. Nothing moved inside me, no life at all; I would have welcomed tangible grief —tears, rage perhaps… but no, only the endless tundra of days… into weeks… The isolation was palpable. I craved sleep. I thought only of death and how it waited for me around every corner. It would take me as it had taken Janice. In fact, it should.

I was already in therapy . I increased my weekly sessions and sought antidepressants from a pharmacologist I referred patients to. What became clear to me and my therapist was that, in addition to Janice’s death, I may well have been arrested by my own psychological inability to accept my full life. I had all that I had dreamed of but never believed I’d have. One who lives so long with a commitment to suffer and a sense that she is unworthy does not go gracefully into a robust and happy life — no matter how hard she works for it consciously. The commitment to leave childhood neuroses behind and to offer oneself greater possibility for fulfillment and pleasure does not take into account the unconscious investment in remaining unfulfilled and unhappy. Sadly, sacrifice and suffering were the bedrock of my self-worth . I’d been battling these issues for years and though progress was evident, the road was long.

I tried, as much as my imprisonment would allow me, to talk to my husband, not only my closest friend but an analyst as well. Alan was gentle but clear-sighted and firm. He raised yet another unresolved issue. I had nothing in my life that was completely my own. All of my activities implied a relationship with another — wife, mother, teacher, therapist, daughter, sister, friend. All were mirrors for me to revel in or castigate myself. My worth was the sum total of what the world thought of me: how I pleased, displeased; how smart I was (was I smart?), how kind, how selfish, how base. Happiness arrived only when the world approved of me. I had no place in my life where I tended to myself alone.

The only thing that had ever come close was my occasional flimsy attempts at writing. Periodically, during one of Alan’s late-night tennis games, I’d light some candles and pour a glass of wine and sit down to write a poem. I had always loved books and had a girlhood wish to write another Gone With the Wind , yet I was drawn to poetry. Given my repressed background, poetry’s pure unmitigated emotion was tantalizing — as were its rich romantic life themes and imagery. The economy of it—the demand for articulation — also lured me. Prose terrified me because of its endless possibilities; my mind was already a quagmire taking endless years to decode; I couldn’t risk the avalanche that a book of prose would bury me in. But a poem struck me as a finite thing. It started, led someplace, and ended — all relatively quickly. It seemed to have rules. Formulas. You used words and lines in seemingly predictable ways. There were things you could do and things you couldn’t in a poem (or so I thought). It was like painting within the lines — very comforting and very much in keeping with my rigorous Catholic background.

But my late-night trysts with poems were very disappointing. In the lucidity of early morning, I’d find that what I’d written was neither profound, nor particularly interesting—nor was the writing itself very good. Dilettante that I was, I’d collapse in a puddle of recrimination insisting that had I any talent, I’d have been able to produce something fine and lasting. Talent meant it was there inside me waiting for me, fully fleshed out. My frustration would keep me from trying again for several months; but then again, the same story. In that conversation, Alan pointed out that though I spoke of wanting to write, I never invested anything of myself in it other than a ceremonial hour or two every few months. I seemed to be waiting to be served. I took in as much of this as I could, given my frozen state, but I knew he was right. He had broken through.

As I attempted to reenter my life, I resolved to see if I could learn to write poetry. I needed to give myself over to something whole and alive — that was mine alone. Thus began my life with the possibility of poems. Therein lay my recovery. Slowly the lights went back on inside me.

Coming: Creative Writing & the Psyche: The Threat of Making Art III: The Beginnings of Speech

Joan Cusack Handler, Ph.D., is a poet, memoirist, and psychologist. Her widely published poems have won five Pushcart nominations.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Support Group

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Reignite Your Creativity: Overcoming Depression and Rediscovering Your Creative Spark

1. understanding depression and its impact on creativity, symptoms of depression, how depression affects creativity, why creativity matters in overcoming depression, 2. embracing self-care to regain your creative spark, physical self-care, emotional self-care, social self-care, 3. engaging in creative activities for depression recovery, art therapy, writing exercises, music therapy, 4. establishing routines to support creativity, creating a schedule, setting goals for creative projects, building creative habits, 5. seeking support to get creativity back after depression, professional help, support groups, connecting with others on the creative journey.

Depression can take a toll on your life, making it difficult to find joy in the things you once loved, including your creativity. But fear not, because it is possible to reignite your creative spark and overcome the challenges brought on by depression. In this blog, we'll explore how to get creativity back after depression, and discuss various strategies and support systems that can help you on your journey to rediscovering your creative spirit.

Before we dive into strategies to boost your creativity, it's important to understand depression and how it affects your creative mind. By gaining a deeper knowledge of this mental health condition, you'll be better equipped to tackle the challenges it presents and find ways to reignite your creative spark.

Depression manifests in various ways, and its symptoms can be different for everyone. Some common signs of depression include:

- Feeling sad, empty, or hopeless

- Loss of interest or pleasure in activities once enjoyed

- Changes in appetite or weight

- Trouble sleeping or sleeping too much

- Feeling tired or lacking energy

- Difficulty concentrating or making decisions

If you're experiencing these symptoms, it's important to reach out to a mental health professional for help.

Depression can negatively impact your creativity in several ways:

- Low energy levels - Depression often leads to fatigue, making it difficult to find the energy to engage in creative pursuits.

- Lack of motivation - Loss of interest in activities you once enjoyed can make it challenging to find motivation to create.

- Difficulty concentrating - Trouble focusing can hinder your ability to think creatively and develop innovative ideas.

Understanding how depression affects your creativity is the first step toward finding ways to overcome these obstacles and rediscover your creative spark.

Although depression can dampen your creative spirit, tapping into your creativity is essential for recovery. Here are a few reasons why:

- Self-expression - Creative activities provide an outlet for expressing your thoughts and emotions, which can help you process and understand your feelings.

- Building self-esteem - Engaging in creative pursuits can boost your confidence, as you see your ideas come to life and gain a sense of accomplishment.

- Creating connections - Sharing your creative work with others can help you form relationships, foster a sense of belonging, and create a support system to aid in your recovery.

Now that we understand the importance of creativity in overcoming depression, let's explore some strategies to help you regain your creative spark.

Now that we've explored the effects of depression on creativity, let's focus on the various self-care practices that can help you get your creativity back after depression. By taking care of your mind, body, and soul, you'll create a solid foundation for reigniting your creative spark.

Physical self-care is all about taking care of your body, which in turn can positively affect your mental health and creativity. Here are some ways you can practice physical self-care:

- Exercise: Engaging in regular physical activity releases feel-good chemicals called endorphins, which can improve your mood and energy levels.

- Sleep: Aim for 7-9 hours of sleep each night to ensure your body and mind are well-rested and ready for creative pursuits.

- Nutrition: Eat a balanced diet full of fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains to fuel your body and brain.

By nurturing your body, you'll be creating a strong foundation for your creative energy to flourish.

Emotional self-care involves addressing your feelings and cultivating a healthy mindset. Here are some ways to practice emotional self-care and help regain your creativity:

- Mindfulness: Practice mindfulness techniques, such as meditation or deep breathing exercises, to help you stay present and focused.

- Journaling: Write down your thoughts and feelings in a journal to better understand your emotions and identify patterns that may be affecting your creativity.

- Positive affirmations: Speak kindly to yourself and use positive affirmations to boost your self-esteem and foster a growth mindset.

By taking care of your emotional well-being, you'll be better equipped to handle the ups and downs of depression and rediscover your creative passions.

Connecting with others is essential to overcoming depression and reigniting your creative spark. Here are some strategies for nurturing your social connections:

- Stay in touch: Reach out to friends and family members regularly to maintain your support network and keep the lines of communication open.

- Join a club or group: Participate in social activities that interest you, such as a book club or an art class. This can help you meet like-minded individuals and expand your social circle.

- Volunteer: Give back to your community by volunteering for a cause you're passionate about. This can create a sense of purpose and help you connect with others who share your values.

By investing time and energy in your relationships, you'll build a supportive network that can help you navigate the challenges of depression and rekindle your creative spirit.

As you continue on your journey to regain your creative spark, it's essential to dive into creative activities that can help you overcome depression. By engaging in various creative pursuits, you'll not only learn how to get creativity back after depression but also find new ways to express yourself and improve your mental well-being. Let's explore some popular creative activities that can help you on this journey.

Art therapy is a powerful tool for self-expression and healing. It allows you to explore your feelings, thoughts, and experiences through different art forms, such as painting, drawing, or sculpting. Here are some ways art therapy can help you regain your creativity after depression:

- Non-verbal communication: Art provides an alternative way to express emotions and thoughts that might be difficult to put into words.

- Stress relief: The process of creating art can be calming and therapeutic, helping you relax and release tension.

- Self-discovery: By exploring different art forms, you might discover new passions or talents, which can boost your confidence and reignite your creative spark.

Writing is another effective way to express yourself and process your emotions. It can be an excellent outlet for creativity and personal growth during your depression recovery. Here are some writing exercises that can help you regain your creative mojo:

- Free writing: Set a timer for 10-15 minutes and write down anything that comes to mind without worrying about grammar, punctuation, or structure. This can help you clear your mind and tap into your subconscious thoughts.

- Poetry: Experiment with different poetic forms to express your emotions and experiences in a creative way. You don't have to be a seasoned poet—just have fun with words and see what resonates with you.

- Storytelling: Craft short stories or personal narratives to explore your feelings, experiences, or fictional worlds. This can help you find meaning in your journey and foster your imagination.

Music can be a powerful force for healing and self-expression. Whether you're listening to your favorite tunes, playing an instrument, or composing your own melodies, music therapy can help you rediscover your creative energy. Here's how:

- Mood regulation: Listening to music can evoke a wide range of emotions and help you process your feelings in a healthy way.

- Active participation: Playing an instrument or singing can be an engaging and enjoyable way to express yourself and build your creative skills.

- Connection: Sharing your musical creations with others or collaborating on projects can foster a sense of community and support, which is crucial in overcoming depression.

By exploring these creative activities, you'll not only learn how to get creativity back after depression but also develop new outlets for self-expression and emotional growth. Remember, the key is to be gentle with yourself, stay open to new experiences, and embrace the creative journey.

Now that you're exploring creative activities, it's time to establish routines that will support your creativity and help you learn how to get creativity back after depression. Routines provide structure and consistency, which can make it easier to prioritize your creative pursuits and track your progress. Let's dive into some ways you can establish routines to nurture your creative spark.

Having a schedule can give you a sense of stability and make it easier to incorporate creativity into your daily life. Here are some tips for creating a schedule that supports your creativity:

- Set aside dedicated time: Carve out specific time slots in your day or week for creative activities, and treat them as non-negotiable appointments with yourself.

- Balance work and play: Ensure that your schedule includes time for both creative pursuits and relaxation, so you don't feel overwhelmed or burnt out.

- Stay flexible: While it's important to have a schedule, it's also essential to be open to change and adapt your routine as needed. Remember, the goal is to support your creativity, not stifle it.

Setting goals can help you stay focused and motivated as you work on your creative projects. Here are some guidelines for setting achievable goals that will inspire you:

- Be specific: Instead of vague goals like "be more creative," aim for something concrete, such as "complete a painting by the end of the month" or "write a poem every week."

- Break it down: Break larger goals into smaller, manageable tasks or milestones to make them less daunting and easier to accomplish.

- Celebrate your wins: Acknowledge and celebrate your victories, no matter how small, to boost your confidence and reinforce your creative progress.

Developing creative habits is an essential part of learning how to get creativity back after depression. Here are some ideas to help you cultivate habits that support your creativity:

- Start small: Begin with small, achievable actions, like setting aside 10 minutes a day to sketch or jot down ideas. Over time, these small habits will grow and become more ingrained in your daily routine.

- Find your rhythm: Identify the times of day when you feel most creative and energized, and try to schedule your creative activities during those periods.

- Stay consistent: Practice your creative habits consistently, even when you don't feel inspired. This will help reinforce the habit and make it easier to tap into your creativity when inspiration strikes.

By establishing routines and building creative habits, you'll create a supportive environment that encourages your creativity to thrive. This, in turn, will help you overcome depression and rediscover your creative spark. Remember to be patient with yourself and trust the process—embracing your creativity is a journey, not a destination.

As you work on rediscovering your creative spark, remember that you don't have to do it alone. Seeking support from others can make a significant difference in your journey to get creativity back after depression. Let's explore some ways you can find help and connect with others who share your creative goals.

Reaching out to mental health professionals is an important step in overcoming depression and reigniting your creativity. Here are some reasons why seeking professional help can be beneficial:

- Expert guidance: Mental health professionals can provide valuable insights and strategies to help you manage your depression and nurture your creativity.

- Personalized treatment: A therapist or counselor can tailor their approach to your specific needs, ensuring that you receive the most effective support for your situation.

Don't be afraid to ask for help—mental health professionals are trained to assist you in your journey to recovery and can play a vital role in helping you learn how to get creativity back after depression.

Joining a support group can be an effective way to connect with others who are also working on overcoming depression and rediscovering their creativity. Here's why support groups can be helpful:

- Shared experiences: Support groups bring together people who have similar experiences, creating a sense of understanding and camaraderie.

- Peer support: Group members can offer encouragement, advice, and empathy, giving you the motivation and confidence to continue your creative journey.

Look for local or online support groups focused on depression, creativity, or both, and remember that sharing your experiences with others can be a powerful tool in your quest to get creativity back after depression.

Building connections with fellow creatives can be both inspiring and supportive as you work to regain your creative spark. Here are some ways to connect with others who share your passion for creativity:

- Join a creative community: Look for local clubs, workshops, or online forums where you can meet like-minded individuals and participate in creative activities together.

- Collaborate on projects: Working with others on a creative project can be a fun and rewarding way to learn from each other, stay motivated, and expand your creative horizons.

By seeking support and connecting with others, you'll find that you're not alone in your journey to learn how to get creativity back after depression. Embrace the power of community and let it be a source of inspiration and strength as you rediscover your creative spark.

In conclusion, overcoming depression and reigniting your creativity is a challenging but rewarding journey. Remember to be patient with yourself, take care of your physical and emotional needs, engage in creative activities, establish supportive routines, and seek help from others along the way. As you practice these strategies, you'll gradually regain your creative spark and learn how to get creativity back after depression. So take a deep breath, trust the process, and let your creativity shine once again.

If you're looking to reignite your creativity and overcome depression, we highly recommend checking out Ana Gomez de Leon's workshop, ' How To Overcome Creative Blocks & Find Inspiration '. This workshop will provide you with valuable insights and techniques to help you break through creative blocks and rediscover your creative spark.

Live classes every day

Learn from industry-leading creators

Get useful feedback from experts and peers

Best deal of the year

* billed annually after the trial ends.

*Billed monthly after the trial ends.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Writing Technique Across Psychotherapies—From Traditional Expressive Writing to New Positive Psychology Interventions: A Narrative Review

Chiara ruini.

Department of Psychology, University of Bologna, Viale Berti Pichat 5, 40127 Bologna, Italy

Cristina C. Mortara

Writing Therapy (WT) is defined as a process of investigation about personal thoughts and feelings using the act of writing as an instrument, with the aim of promoting self-healing and personal growth. WT has been integrated in specific psychotherapies with the aim of treating specific mental disorders (PTSD, depression, etc.). More recently, WT has been included in several Positive Interventions (PI) as a useful tool to promote psychological well-being. This narrative review was conducted by searching on scientific databases and analyzing essential studies, academic books and journal articles where writing therapy was applied. The aim of this review is to describe and summarize the use of WT across various psychotherapies, from the traditional applications as expressive writing, or guided autobiography, to the phenomenological-existential approach (Logotherapy) and, more recently, to the use of WT within Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Finally, the novel applications of writing techniques from a positive psychology perspective will be analyzed. Accordingly, the applications of WT for promoting forgiveness, gratitude, wisdom and other positive dimensions will be illustrated. The results of this review show that WT yield therapeutic effects on symptoms and distress, but it also promotes psychological well-being. The use of writing can be a standalone treatment or it can be easily integrated as supplement in other therapeutic approaches. This review might help clinician and counsellors to apply the simple instrument of writing to promote insight, healing and well-being in clients, according to their specific clinical needs and therapeutic goals.

Introduction

Writing therapy can be defined as the process in which the client uses writing as a means to express and reflect on oneself, whether self- generated or suggested by a therapist/researcher (Wright & Chung, 2001 ). It is characterized by the use of writing as a tool of healing and personal growth. From the first investigations of James Pennebaker (Pennebaker & Beall, 1986 ), writing therapy has shown therapeutic effects in the elaboration of traumatic events. In recent years, expressive and creative writing was found to have beneficial effects on physical and psychological health (Nicholls, 2009 ).

Currently, clinicians have moved from a distress-oriented approach to an educational approach, where writing is used to build personal identity and meaning through the use of autobiographical writing (Hunt, 2010 ). In this vein, autobiographical writing is becoming a widespread technique, which allows people to recall their life path and to better understand the present situation (McAdams, 2008 ). Moreover, it is observed that individuals often tend to report significant life events (positive or negative) in personal journals (Van Deurzen, 2012 ). Keeping a journal is a way of writing spontaneously: it can be considered a sort of logbook where thoughts, ideas, reflections, self-evaluation and self -assurances are recorded in a private way. Journaling is different from therapeutic writing the writer does not receive specific instructions on the contents and methodologies to be followed when writing, as it happens in therapeutic writing. Nowadays journaling can be done also through online blogs and social network (Facebook). In doing so, a private and spontaneous journal can be shared publically.

Writing techniques are often implemented into talking therapies, since both processes (talking and writing) favor the organization, acceptance and the integration of memories in the process of self-understanding (Lyubomirsky et al., 2006 ). However, expressive writing has been found to be beneficial also as a “stand alone” technique for the treatment of depressive, anxious and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms (Reinhold et al., 2018 ). In a recent study, it was found that enhanced expressive writing (i.e., writing with scheduled contacts with a therapist) was as effective as traditional psychotherapy for the treatment of traumatized patients. Expressive writing without additional talking with a therapist was found to be only slightly inferior. Authors concluded that expressive writing could provide a useful tool to promote mental health with only a minimal contact with therapist (Gerger et al., 2021 ). Another recent investigation (Allen et al., 2020 ) highlighted that the beneficial effect of writing techniques may be moderated by individual differences, such as personality trait and dysfunctional attitude (i.e., high level of trait anxiety, avoidance and social inhibition). In these cases, therapeutic writing may be even more beneficial since it avoids the interactions with the therapist or other clients.

This article aims to illustrate and summarize the main psychotherapeutic interventions where writing therapy plays an important role in the healing process. For instance, a common application is the use of a diary in standard Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for promoting patients’ self observation (Butler et al., 2006 ). Similarly, other traditional psychotherapies use writing in their therapeutic process: from the pivotal application of writing to understand and overcome traumatic experiences, to the phenomenological-existential approach where writing has the function of giving meaning to events and of clarifying life goals (King, 2001 ), to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, where writing facilitates the process of thought-defusion (Hayes, 2004 ). This review will also address the novel applications of writing technique to new a psychotherapeutic context: positive psychotherapy where the tool of writing is employed in many effective techniques (i.e. writing gratitude or forgiveness letters). Smyth ( 1998 ) reviewed 13 case-controlled writing therapy studies that showed the positive influence of writing techniques on psychological well-being. The benefits produced in writing activity (self regulation, clarifying life goals, gaining insight, finding meaning, getting a different point of view) can be described under the rubric of psychological and emotional well-being. In accordance with Fredrickson’s Broaden and Build Theory of Positive Emotions ( 2004 ), writing may foster positive emotions since putting feelings and thoughts into words widens scope of attention, opens up to different points of view and allows the mind to be more flexible (King, 2001 ).

Finally, we will describe and explore new contexts where writing activities currently take place: the web and social networks. We will underline important clinical implications for these new applications of writing activities.

Traditional Applications of Writing Techniques

Clinical applications of writing therapy include the method of expressive writing created by Pennebaker (Pennebaker & Beall, 1986 ); the autobiography; and the use of a diary in traditional Cognitive Behavioral Therapy as described in the following sections.

James Pennebaker: The Paradigm of Expressive Writing

James Pennebaker was the first researcher that studied therapeutic effects of writing. He developed a method called expressive writing, which consists of putting feelings and thoughts into written words in order to cope with traumatic events or situations that yield distress (Pennebaker & Chung, 2007 ). In the first writing project, Pennebaker and Beall ( 1986 ) asked fifty college students to write for fifteen minutes per day for four consecutive days. They were randomly instructed to write about traumatic topics or non-emotional topics. Results showed that writing about traumatic events was associated with fewer visits to the health center and improvements in physical and mental health. The experiment was repeated several times with different samples: with people who suffered from physical illnesses, such as arthritis and asthma, and from mental pathologies such as depression (Gortner et al., 2006 ). Individuals with different educational levels or writing skills were examined, but these variables were not found to be significant. At first, studies investigated only traumatic events, but later research expanded the focus to general emotional events or specific experiences (Pennebaker & Evans, 2014 ).

According to Pennebaker, what makes writing therapeutic is that the writer openly acknowledges and accepts their emotions, they become able to give voice to his/her blocked feelings and to construct a meaningful story.

Other therapeutic ingredients of expressive writing concern (1) the ability to make causal links among life events and (2) the increased introspective capacity. The former may be favored through the use of causality terms such as “because”, “cause”, “effect”; the latter through the use of insight words (“consider”, “know” etc.). These emotional and cognitive processes were analyzed through a computerized program (Pennebaker et al., 2015 ) and outcomes showed that the more patients used causation words, the more benefits they derived from the activity. Similarly, using certain causal terms expresses the level of cognitive elaboration of the event achieved by the patient and may indicate that the emotional experience has been analyzed and integrated (Pennebaker et al., 2003 ). Thus, the benefits of writing stem from the activity of making sense of an emotional event, the acquisition of insight about the event, the organization and integration of the upheaval in one’s life path.

Moreover, expressive writing allows a change in the way patients narrate life events. Many studies have highlighted that writing in first or third person alters the emotional tone of the narration (Seih et al., 2011 ). It is common for people who have experienced a severe traumatic event to initially narrate it in the third person and only later, once the elaboration and integration processes have set into motion, are they able to narrate their experience in the first person. This phenomenon occurs because third person narration allows the writer to feel safer and more detached from the experience, while first person perspective reminds them that they were the protagonist of the trauma. While writing using the third person can be easier in the wake of a traumatic event, writing in first person has been demonstrated to be more effective in the elaboration process (Slatcher & Pennebaker, 2006 ).

Another issue examined by Pennebaker and Evans ( 2014 ) concerns the difference between writing and talking about a trauma. In expressive writing, an important element consists of feeling completely honest and free to write anything, in a safe and private context without necessarily share the content with a listener or the therapist. Conversely, talking about trauma implies the presence of a listener, and the crucial aspect lies in the listener’s capability to comprehend and accept the patient’s narrative. Moreover, the interactions with a therapist could be particularly stressful for individuals with high levels of social inhibitions and trait anxiety (Allen et al., 2020 ).

Writing Techniques for Addressing Trauma

Writing is considered a therapeutic strategy to cope with life adversities thanks to the positive effects of putting feelings and thoughts into words. There are various writing techniques used as therapeutic strategies to cope with a trauma which are described in Table Table1 1 .

Writing approaches in clinical interventions

What the aforementioned writing therapies all have in common is a theoretical underpinning: the act of writing as a means to modify one’s life story and reframe elements which survivors want to change. Creating stories and thinking of ways to alter them may emphasize on one hand the possibility of a real change to occur, and on the other, the active role of the individual in their own life (Sandstrom & Cramer, 2003 ). In this way, writing can be also defined as a process of resilience: putting negative feelings into words can spark the search for solutions, with the consequence of having a positive attitude towards life challenges and promoting personal growth.

Besides the numerous positive effects of writing, there can be situations in which writing does not work, or when it can actually cause negative side effects. An example of said situation is when an individual has to deal with issues that arise intense painful emotions. In this case, writing can cause crying, very low mood, or even a breakdown (Pennebaker & Chung, 2007 ). This may occur because analyzing a traumatic experience may trigger a process of cognitive rumination, which is considered a specific symptom of PTSD (Pennebaker & Evans, 2014 ).

In conclusion, the paradigm of expressive writing is frequently used in patients who have had distressing experiences. Writing about traumatic experiences can help to elaborate negative emotions connected to the upheaval, to construct a narrative of the event, and to give it a meaning. However when client’s levels of distress are very intense and/or they are maintained by cognitive rumination, it is not advisable to undergo a writing exercise.

McAdams: The Use of Autobiography in the Construction of Self-identity