- Terms & Condition

- Privacy policy

- _Multi Dropdown

- __Dropdown 1

- __Dropdown 2

- __Dropdown 3

- ApplicationLetter

मेरो देश नेपाल बारे निबन्ध | Essay on my country nepal in nepali

मेरो देश नेपाल बारे निबन्ध | essay on my country nepal in nepali , मेरो देश नेपाल बारे निबन्ध (१५० शब्दहरु ) mero desh essay in nepali language, मेरो देश को बारेमा निबन्ध 200 शब्दमा essay on my country in nepali in 200, मेरो देश नेपाल बारे निबन्ध (२५० शब्दहरु ) mero desh nepal essay in nepali, मेरो देश को बारेमा निबन्ध 300 शब्दमा essay on my country in nepali in 300, मेरो देश नेपाल बारे निबन्ध ( ५०० शब्दहरु) essay on my country nepal in nepali in 500 words, recommended posts, post a comment.

Thanks for visit our site, please do not comment any spam link in comment box.

एक टिप्पणी भेजें

Contact form.

- Lalitpur-14, Bishalchwok, Nepal

- [email protected]

- _Graphic Design

- _Web Design

- _Banner Advertisement

- Digital Marketing

- __Facebook Marketing

- __Google Ads

- __Boosting & Promotion

- Get A Quote

Nepali Society: Past Present and Future

The Nepali Society: Past, Present and Future

By society, we mean a long-standing group of people sharing cultural aspects such as language, dress, norms of behaviour and artistic forms. Nepali society has a mixed culture. Even though different cultures live together, cultural practices are often mixed and one cultural group can be seen practising the traditions of another. People are free to choose their own cultural practices and no one is forced to follow any particular pattern. As a Nepali citizen, I like Nepali society much. I have seen as well as read about Nepali society and its change.

Over time, many changes have been seen in the context of Nepali society. The condition of Nepali society wasn't good in the past time. Nepali society was so rigid in the past time. Most people were uneducated and there was a lack of awareness among the people. Patriarchal norms and values were at their height. Class, as well as sex subjection, had played a vital role in every society.

The concept of Feudalism was prevalent everywhere. Ordinary people had to face miserable life under the feudalists. They were quite a way from the concept of rights and opportunities of lives. Life was so difficult for most of the peasants. There was a lack of facilities in people's lives. In most societies, there were feudalists or lords who used to determine others fate. Talking about women's lives during that time, women had very bad conditions. They were living being dependent on males. The patriarchal norms and values had made them remain limited within the boundaries of their houses. Child marriage was so common. Life in the past was really not favourable for ordinary people including women. In the present time, different changes are seen in various sectors of Nepal.

Nepali societies seem quite different from that of past Nepalese societies. In the present, Nepali society is on the way to development. In the matter of facilities as electricity, drinking water, roads and transportation, education etc, Nepali society has been changed. People in the present time have various rights regarding various things. If there is one thing that upsets me about Nepali society is the political aspect. People in the present time are totally involved in the dirty game of politics. Due to this, Nepali society is facing disorders every single day. At present, the condition of Nepali women is much better than expected.

Over time, Nepali women have got many rights according to the constitution of Nepal. I think the future of Nepali society will be so good if we all Nepali citizens choose the right candidates for the betterment of Nepalese society. We should be away from this dirty game of politics and think about the bright future of Nepali people and society.

Post a Comment

We would be happy to receive constructive feedback and suggestion. Thank You in Advance.

Related Posts

Slider partner.

Subscribe Text

Offered for educational organizations.

- Sign into Account

- Register Account

- Reference Notes

- Faculties & Levels

- Subject Notes

- Notice Board

- Question Papers

- Ask Questions

- Public Articles

- General Articles

- Buy & Sell Books

- Find Colleges

- Condition of Women in Nepali Society - Essay | Free Writing

Essay Writing

Letter writing, essay (free writing).

Essay Writing Unit: Essay (Free Writing) Subject: English Grade XI

Share article, share on social media.

- English Grade XI

Essay | Free Writing The Position of Woman in Nepali Society

The status of women in Nepal cannot be said to be good. More than 60% of women are illiterate. The status of women is different according to regions, castes, economy, religion, and structure of the community. The women of higher castes have been more suppressed though they have got more facilities and opportunities of education and employment. The women of lower castes have got more freedom than the former ones but they have got less chance of education and employment. Most of Nepalese women do not have right to the property. They are not often involved in making policies and decisions of family as well as nation.

Nowadays some reservation and empowerment programmes are being held to encourage the women. Though they have they have equal right in the articles of constitution but in the field it has not been followed. They are however unable to participate into the public affairs due to the dominant ideology of culture being practiced. While the latter women have no autonomy even within the private sphere, but enjoy limited position in the public sphere. Their suppression stems from the concepts of hierarchy the caste system, traditional though about food, and the high value of chastity. Although the women belonging to different caste, religion, and culture have different status, one thing is certain that they are being suppressed with respect to economic, socio-cultural, political and legal status which can’t be analyzed in isolation because each is intrinsically tied to the next. But for the clarity, each category is discussed separately. Economically the status of Nepalese women is also not good. The dominant Hindu religion and culture have popularized a belief that women should be dependent on the males for income from cradle to grave. Men are considered the sole breadwinners of families; and women are viewed only as domestic and maternal. Women’s work is confined to the household. Their responsibilities are thought to include cooking, washing, maternity, collecting fuel and firewood, fetching water, engaging in agriculture, and service to males and other family members. Although their works plays vital role, it is generally left uncounted.

The workload of Nepalese women is immense. They work about 16 hours every day. Nepalese women are mainly engaged in agricultural works, carpet Industries, and wage labour activities. Furthermore, Nepalese women are compelled to resort to prostitution and to be sold as commercial sex-workers. Because of modernization, their work load has certainly increased. Thus they are now forced to perform triple roles; that of mother, of traditional wife and of community participant. Generally, Nepalese women have much less access to institutional credit, both an individual and household enterprise level irrespective of ecological regions, urban of rural increasing feminization of poverty. To remedy this situation, women should need full economic rights.

Dowry system has also decreased the status of women especially in Terai and urban areas. Women have been bargained as fancy good in a shop.

You may also like to read:

Popular subjects.

Meaning Into Words Grade XI

Grade xi 1 unit, 19 articles.

The Magic of Words

Grade xi 6 units, 21 articles.

The Heritage of Words

Grade xii 8 units, 21 articles.

Flax-Golden Tales

Bachelor's level 13 units, 38 articles.

Meaning Into Words Grade XII

Grade xii 1 unit, 12 articles.

Major English Grade XII

Grade xii 5 units, 31 articles.

Link English

Grade xi 1 unit, 8 articles.

Adventures in English Volume II

Bachelor's level 7 units, 27 articles.

Major English Grade XI

Grade xi 4 units, 18 articles.

Economics Grade XI

Grade xi 17 units, 66 articles.

Sabaiko Nepali Grade XI, XII

Foundations of Human Resource Management

Bachelor's level 9 units, 23 articles.

- [email protected]

- Login / Register

Culture and Traditions of Nepal: A Journey Through the Heart of Nepalese Heritage

Article 12 Feb 2023 4774 0

Nepal is a country steeped in rich cultural heritage and traditions. With a unique blend of Hindu and Buddhist influences, Nepalese culture is a vibrant and colorful tapestry of festivals, customs, music, and art. In this article, we'll explore the diverse cultural landscape of Nepal, from its religious roots to the unique traditions of its ethnic groups.

A Brief History of Nepal and its Cultural Influences

Nepal has a long and storied history, with influences from Hindu and Buddhist cultures and the presence of various ethnic groups. The country was ruled by a Hindu monarchy until the late 18th century, when it became a Hindu state. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Buddhism gained popularity, and today both religions coexist in Nepal. This fusion of Hindu and Buddhist beliefs and practices has shaped the country's culture and traditions.

Nepal is a landlocked country located in South Asia and is bordered by India and Tibet (China). Its history is rich and diverse, with cultural influences from the Hindu and Buddhist religions. The country has been ruled by various dynasties and kingdoms throughout its history, and its culture has been shaped by these influences as well as by its geographic location and contact with neighboring countries.

The earliest inhabitants of Nepal were likely animist tribes who worshipped nature and natural elements. Over time, Hinduism and Buddhism were introduced to the country, and these religions have played a major role in shaping its culture and traditions. Nepal was officially declared a Hindu kingdom in the 19th century, but the influence of Buddhism has remained strong, particularly in the northern regions of the country.

Today, Nepal is a diverse country with many different ethnic and cultural groups, each with its own unique customs and traditions. Despite this diversity, there is a strong sense of national identity in Nepal, and its people take great pride in their cultural heritage.

Overview of the Major Religions in Nepal and Their Impact on the Country's Culture and Traditions

The majority of Nepalese people practice Hinduism, and it is the dominant religion in the country. Hinduism has had a profound impact on Nepalese culture and traditions, with many customs, festivals, and rituals being rooted in this religion. The festivals of Dashain and Tihar, for example, are celebrated by Hindus in Nepal and are closely tied to Hindu mythology.

Buddhism is also widely practiced in Nepal, particularly in the northern regions of the country. The Kathmandu Valley is home to many Buddhist monasteries, and the Stupa of Swayambhunath is one of the most important Buddhist pilgrimage sites in the world. Buddhism has influenced Nepalese culture in many ways, including the traditional art and architecture of the country.

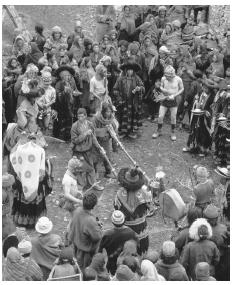

Traditional Festivals and Celebrations

Nepal is a country with many colorful and vibrant traditional festivals and celebrations. Some of the most important and widely celebrated festivals include:

- Dashain: Dashain is the biggest and most important festival in Nepal and is celebrated by Hindus across the country. The festival celebrates the victory of good over evil and is marked by feasting, dancing, and the exchange of gifts. The festival lasts for 15 days, and families come together to participate in the celebrations.

- Tihar: Tihar is another major festival in Nepal, and it is also celebrated by Hindus. The festival is also known as the Festival of Lights, and it is marked by the lighting of oil lamps and the decoration of homes with flowers and other decorations. During the festival, families come together to offer prayers, sing songs, and exchange gifts.

- Holi: Holi is a spring festival that is celebrated by Hindus and is known as the Festival of Colors. The festival is marked by the throwing of colored powders and the singing of traditional songs. Holi is a time of joy and celebration and is a time when people put aside their differences and come together to celebrate.

- Gai Jatra: Gai Jatra is a traditional festival that is celebrated by the Newar community in Kathmandu. The festival is a time of celebration and remembrance, and it involves the procession of people dressed in cow costumes. The festival is believed to bring comfort to the families of those who have died in the previous year.

These are just a few of the many traditional festivals and celebrations that take place in Nepal. Each festival has its own unique customs and traditions, and they serve as an important part of the country's cultural heritage.

Unique Customs and Traditions of the Ethnic Groups in Nepal

Nepal is home to a rich tapestry of ethnic groups, each with their own unique customs and traditions. These ethnic groups are an important part of Nepalese culture and contribute to the country's diverse heritage.

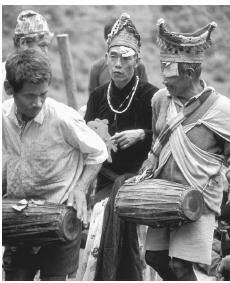

- Gurungs: The Gurungs are an ethnic group native to the western region of Nepal and are known for their hospitality and bravery. They have a rich tradition of music and dance and are famous for the Ghantu dance, which is performed during festivals and celebrations. The Gurungs are also known for their traditional woven textiles and handicrafts, which are popular among tourists visiting Nepal.

- Tamangs: The Tamangs are an ethnic group native to the central region of Nepal and are known for their rich cultural heritage. They have a tradition of storytelling, passed down from generation to generation, and are famous for their unique instruments like the Madal drum. The Tamangs also have a rich tradition of metalwork, including the creation of traditional knives and other tools.

- Newars: The Newars are an ethnic group native to the Kathmandu Valley and are known for their elaborate wood carvings, metalwork, and traditional festivals. The Newars have a rich history, dating back to the time of the ancient kingdoms in the Kathmandu Valley, and are known for their distinctive architecture and art. The Newars are also famous for their traditional food, which is a fusion of Nepalese, Tibetan, and Indian cuisine.

The customs and traditions of each of these ethnic groups add to the rich cultural heritage of Nepal and provide a unique insight into the country's diverse history. From the traditional music and dance of the Gurungs to the intricate wood carvings of the Newars, each ethnic group offers a unique glimpse into the customs and traditions of Nepal.

An examination of how modern Nepalese society is impacting traditional cultural practices

With the advancement of technology and globalization, modern Nepalese society has brought about changes to traditional cultural practices. The younger generation is becoming more westernized, and traditional customs and beliefs are slowly being replaced by modern ideas. For instance, the younger generation is more likely to celebrate Western holidays like Christmas, rather than traditional festivals like Dashain and Tihar.

Additionally, with the rise of urbanization, many rural Nepalese are moving to cities, and as a result, traditional practices are being lost. Many of the younger generation do not have access to or the opportunity to learn traditional practices from their elders. The influence of modern society has also led to a decline in traditional crafts like wood carving and metalwork.

However, the Nepalese government and cultural organizations are taking steps to preserve and promote traditional cultural practices. The preservation of cultural heritage is seen as an important aspect of Nepalese identity and is necessary for the continuation of traditional practices.

"Nepal has a rich cultural heritage that has been passed down from generation to generation. It is our responsibility to preserve and promote these traditions so that they can continue to be a part of our identity," says a cultural expert from Nepal.

Preservation and promotion of Nepalese culture and traditions

The preservation and promotion of Nepalese culture and traditions are crucial for ensuring the longevity and relevance of this rich cultural heritage. There are several organizations and initiatives aimed at promoting Nepalese culture and traditions, both domestically and internationally.

For instance, the National Museum of Nepal, located in Kathmandu, serves as a hub for showcasing the country's cultural heritage through its exhibits and cultural programs. The museum works to preserve traditional Nepalese artifacts and promote the country's cultural heritage to both domestic and international audiences.

Similarly, the Nepalese government, along with local communities, have been working to preserve traditional festivals and celebrations. For example, the Gai Jatra festival in Kathmandu has been officially recognized as an important cultural event and is protected by the government, ensuring its continuation for future generations.

In addition to these efforts, cultural exchange programs have been established between Nepal and other countries, promoting the country's unique traditions and customs globally. The Gurkha Museum in Winchester, England, for example, showcases the cultural heritage of the Gurkha soldiers and their contributions to the British Army.

Moreover, there are numerous non-government organizations that are working to preserve and promote the cultural heritage of Nepal. These organizations aim to raise awareness about Nepalese culture and traditions, particularly among the younger generation, to ensure that these customs and traditions continue to be passed down from one generation to the next.

In conclusion, Nepal is a country with a rich and diverse cultural heritage that is shaped by its history, religion, and traditions. From the elaborate wood carvings of the Newars to the traditional festivals and celebrations of Dashain, Tihar, and Holi, Nepalese culture is a tapestry of fascinating customs, practices, and art forms. With a focus on preservation and promotion, Nepalese culture will continue to thrive and provide a unique and rich experience for future generations.

"Nepalese culture is like a treasure trove, with something new to discover at every turn. It is our duty to preserve and promote it, so that future generations can experience and appreciate its richness and diversity," says cultural historian, Dr. Bhagat Singh.

- Latest Articles

9 Practical Tips to Start Reading More Every Day

Top study strategies for student success, top study tips for exam success: effective strategies for academic achievement, what do colleges look for in an applicant: top qualities and traits , how to study smarter, not harder: tips for success, top strategies & tips for effective exam preparation, 10 important roles of technology in education, the real reason why you can’t learn something new, how to make learning mathematics easier and more effective, 20 essential tools every student needs for success, understanding the psychology of shame: causes and solutions, how to enjoy reading even when you hate it, why you should consider tuition classes to help improve your test scores, brain vs. consciousness: a new perspective, why financial literacy is vital for young adults, understanding how agi will work, theory of intelligence without purpose: a comprehensive exploration, apply online.

Find Detailed information on:

- Top Colleges & Universities

- Popular Courses

- Exam Preparation

- Admissions & Eligibility

- College Rankings

Sign Up or Login

Not a Member Yet! Join Us it's Free.

Already have account Please Login

- Culture & Lifestyle

- Madhesh Province

- Lumbini Province

- Bagmati Province

- National Security

- Koshi Province

- Gandaki Province

- Karnali Province

- Sudurpaschim Province

- International Sports

- Brunch with the Post

- Life & Style

- Entertainment

- Investigations

- Climate & Environment

- Science & Technology

- Visual Stories

- Crosswords & Sudoku

- Corrections

- Letters to the Editor

- Today's ePaper

Without Fear or Favour UNWIND IN STYLE

What's News :

- Blueprint for free education

- Festive season sale

- MCC implementation achievement

- Nepali Congress

- SAFF-U20 Championship

Inclusivity is an important discourse in Nepali literature

Kshitiz Pratap Shah

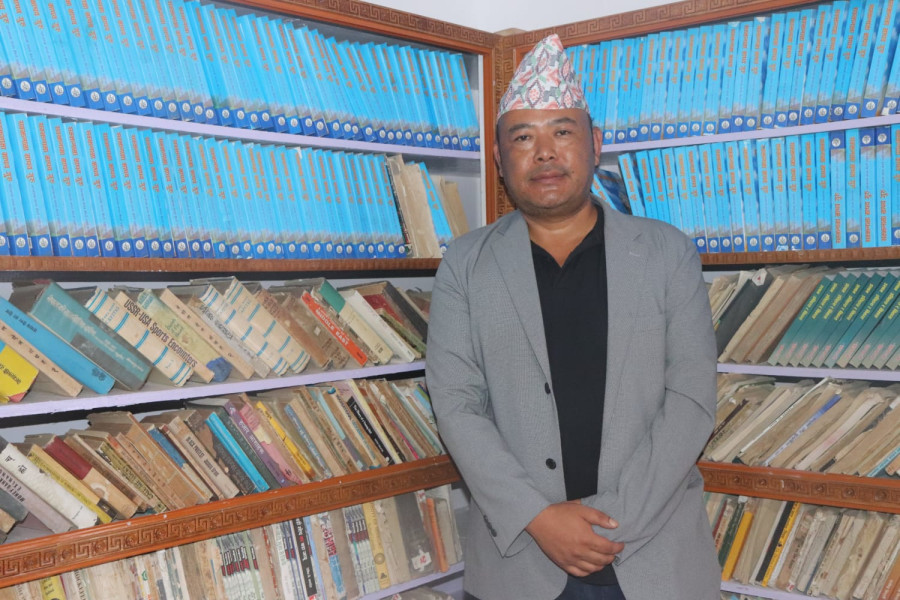

Prakash Thamsuhang is an Ilam-based poet and essayist. He has been working in the literary field for the past three decades and has published ‘Palamko Murchana’, a poetry collection and ‘Sabdathum’, an essay collection.

Thamsuhang is currently the chairperson of the Yakthung Writer’s Association and Ilam Nagar Sahitya Kala Sangit Pratisthan.

In this talk with the Post ’s Kshitiz Pratap Shah , Thamsuhang discusses his literary inspirations, writing in various forms and genres, and the importance of his locale to his writing.

What was your early reading experience? Tell us about your first read.

I remember reading comic books when I was younger. In Ilam bazaar, there was this comic store called Srijana Store, where I would eagerly wait for new editions of Chacha Chowdhary comics.

When I got older, I started buying issues of magazines like Muna and Yuva Mancha from the same shop. I loved reading Khagendra Sangraula's works in Yuva Mancha. My brothers also bought me books, like Prakash Kovind’s novels and Hindi detective stories. I also recall reading Garima magazines and Sajha Prakashan’s Sajha Katha.

I still remember one book I couldn’t finish reading as a kid: Robinson Crusoe. The book is about a sailor whose ship got wrecked and was stuck on a remote island. I believed that story to be true and was thoroughly excited by the adventures of the stranded sailor.

Unfortunately, the Nepali translation was incomplete. I still wonder if that sailor is still stuck on the island or if he was rescued eventually.

How has your experience been with reading as a writer and an essayist? What things prompted you to write essays and poem writing?

From my early school days, I have been interested in literature. I always thought of myself as a reader with an author hidden within me.

Writing helped me expand my vocabulary substantially. My belief in dedicating myself to critical, reflective and analytical writing came through the books I read. These texts made me realise our duty to read humanity itself.

Through my readings, I realised how writing can be used to criticise and illuminate the discriminations and wrongdoings in our society.

What is your favourite text or book that had the most impact on you, personally and professionally?

My writings have been heavily inspired by Bairagi Kaila’s poetry. His poems are philosophical and culturally aware, and they make great use of myths.

I aspire to write poetry in Kaila’s style, but it would be difficult to emulate such heights, even with lots of experience and study.

Through Shankar Lamichhane’s writings, I am also learning how to make my writings even more relatable to readers. His writings inspire me.

How inclusive would you say Nepal’s writing space has been for you in terms of opportunity, language, and other aspects?

Nepali literature in the past was limited, and there was little representation of the actual state of Nepali society. Diversity is an intrinsic part of Nepal’s social identity. Yet, our literature kept presenting the reflections, myths and cliches of only one ethnic group and culture, that of the politically dominant community. Due to this one-tone focus of Nepali literature, many of us started on the path of identity-focused writing.

Even then, the mainstream literary society labelled us as a minority and attempted to sideline us. Marginalised writing and the diverse corners of Nepali literature have historically been treated unfairly.

Yet, our repeated intervention and many literary movements have helped establish inclusivity as an important discourse in Nepali literature. No one can attempt to discredit or interrupt writers who want to write about their identity.

Still, we need to include more writings of different mother tongues in Nepali literature.

What text are you reading currently? Tell us something about your reading preferences.

I am currently reading historian and former journalist Rajkumar Dikpal’s ‘Prithvi Narayan Shah: Alochnatmak Itihaas’. This book tells of the hidden or lost historical truths from the famous king’s time.

In the context of most Nepali historians idolising Pritvi Narayan Shah, this text’s attempt to see things more critically has been refreshing to read.

Currently, my focus is on reading texts focused on the Mundhum, cultural and historical matters.

How do you think your hometown and your experiences in Ilam have helped you in your academic and other written works?

Ilam has a significant literary heritage. Prominent local authors like Santa Gyandil Das, Raharsingh Rai, Mahananda Sapkota, Dr Tana Sharma, and Janaklal Sharma have continuously inspired my writing.

I hope that my works and writings inspire the younger generation in some way. This is my current goal.

We recently opened a community library with the help of the Ilam Municipality to develop a reading culture among the local youth and remind them that technology alone cannot fulfil their quest for knowledge.

The annual Ilam Literature Festival is also held here to encourage literature-inclined students of Ilam and guide them through the contemporary literary landscape.

I have found that this helps young writers in their understanding of the field.

Prakash Thamsuhang’s Book Recommendations

Nawacoit Mundhum

Author: Bairagi Kainla

This compilation of texts belongs to the oral tradition of the Yakthung Limbus, handed down through generations for centuries. It discusses the universe, the earth, and the origins of humanity, emphasising that words were the first creation.

Abstract Chintan Pyaj

Author: Shankar Lamichhane

Publisher: Sajha Prakashan

I frequently recommend this classic literary masterpiece by Shankar Lamichhane to readers. It showcases his exceptional writing skills and provides a deep understanding of his articulation of ideas through essays.

Damini Bhir

Author: Rajan Mukarung

Publisher: Phoenix Books

Mukarung’s writings are extremely helpful for understanding Kirati culture, and he is good at writing about them. He excels at capturing local tales and the essence of the region, vividly portraying the roots of common people.

Author: Raja Punayani

Publisher: Book Hill

The poems in this book are about climate change and nature conservation. They examine the relationship between human institutions and nature through the lens of Kirati culture.

Prithviko Avishkar

Author: Sundar Kurup

Publisher: Shangri-La Books

The poems in this collection have an organic flavour. They artistically portray the movements of life and the minute elements of society.

Author: Shyam Shah

This collection of stories highlights the untapped potential of tales from Madhesh. Shah’s writing helps us appreciate the novelty and beauty of Madheshi stories.

Kshitiz Pratap Shah Kshitiz Pratap Shah was a Culture and Lifestyle intern. He is an undergraduate student at Ashoka University, pursuing an English & Media Studies major.

Related News

How reading shaped this global citizen

The enigma of the golden trails

Reading influences the direction of films

Applying a filter of conscience

Balancing business, diplomacy and reading

‘Ananda Samhita’ launched

Most read from books.

Editor's Picks

Nepal has a long way to go before it is Olympics-ready

As RSP expands, it is following in the footsteps of the old parties it despised

India’s foreign policy misalignment

Barred from screen: How Nepal’s films are failing blind, deaf viewers

It’s official: Chinese drones will fly trash out of Everest slopes

E-paper | august 22, 2024.

- Read ePaper Online

- Countries and Their Cultures

- Culture of Nepal

Culture Name

Alternative name, orientation.

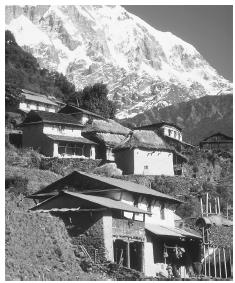

Identification. Nepal is named for the Kathmandu Valley, where the nation's founder established a capital in the late eighteenth century. Nepali culture represents a fusion of Indo-Aryan and Tibeto-Mongolian influences, the result of a long history of migration, conquest, and trade.

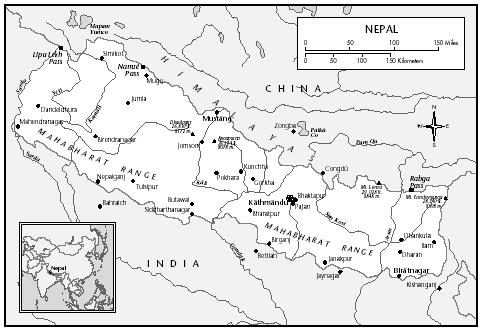

Location and Geography. Nepal is a roughly rectangular country with an area of 147,181 square miles (381,200 square kilometers). To the south, west, and east it is bordered by Indian states; to the north lies Tibet. Nepal is home to the Himalayan Mountains, including Mount Everest. From the summit of Everest, the topography plunges to just above sea level at the Gangetic Plain on the southern border. This drop divides the country into three horizontal zones: the high mountains, the lush central hills, and the flat, arid Terai region in the south. Fast-moving, snow-fed rivers cut through the hills and mountains from north to south, carving deep valleys and steep ridges. The rugged topography has created numerous ecological niches to which different ethnic groups have adapted. Although trade has brought distinct ethnic groups into contact, the geography has created diversity in language and subsistence practices. The result is a country with over thirty-six ethnic groups and over fifty languages.

Demography. The population in 1997 was just over 22.6 million. Although infant mortality rates are extremely high, fertility rates are higher. High birth rates in rural areas have led to land shortages, forcing immigration to the Terai, where farmland is more plentiful, and to urban areas, where jobs are available. Migration into cities has led to over-crowding and pollution. The Kathmandu Valley has a population of approximately 700,000.

Linguistic Affiliation. After conquering much of the territory that constitutes modern Nepal, King Prithvi Narayan Shah (1743–1775) established Gorkhali (Nepali) as the national language. Nepali is an Indo-European language derived from Sanskrit with which it shares and most residents speak at least some Nepali, which is the medium of government, education, and most radio and television broadcasts. For many people Nepali is secondary to the language of their ethnic group or region. This situation puts certain groups at a disadvantage in terms of education and civil service positions. Since the institution of a multiparty democracy in 1990, linguistic issues have emerged as hotly debated topics.

Symbolism. The culture has many symbols from Hindu and Buddhist sources. Auspicious signs, including the ancient Hindu swastika and Shiva's trident, decorate buses, trucks, and walls. Other significant symbols are the emblems (tree, plow, sun) used to designate political parties.

Prominent among symbols for the nation as a whole are the national flower and bird, the rhododendron and danfe; the flag; the plumed crown worn by the kings; and the crossed kukhris (curved knives) of the Gurkhas, mercenary regiments that have fought for the British Army in a number of wars. Images of the current monarch and the royal family are displayed in many homes and places of business. In nationalistic rhetoric the metaphor of a garden with many different kinds of flowers is used to symbolize national unity amid cultural diversity.

History and Ethnic Relations

The birth of the nation is dated to Prithvi Narayan Shah's conquest of the Kathmandu Valley kingdoms in 1768. The expansionist reigns of Shah and his successors carved out a territory twice the size of modern Nepal. However, territorial clashes with the Chinese in the late eighteenth century and the British in the early nineteenth century pushed the borders back to their current configuration.

National Identity. To unify a geographically and culturally divided land, Shah perpetuated the culture and language of high-caste Hindus and instituted a social hierarchy in which non-Hindus as well as Hindus were ranked according to caste-based principles. Caste laws were further articulated in the National Code of 1854.

By privileging the language and culture of high-caste Hindus, the state has marginalized non-Hindu and low-caste groups. Resentment in recent years has led to the organization of ethnopolitical parties, agitation for minority rights, and talk about the formation of a separate state for Mongolian ethnic groups.

Despite ethnic unrest, Nepalis have a strong sense of national identity and pride. Sacred Hindu and Buddhist sites and the spectacular mountains draw tourists and pilgrims and give citizens a sense of importance in the world. Other natural resources, such as rivers and flora and fauna are a source of national pride.

Hindu castes and Buddhist and animist ethnic groups were historically collapsed into a single caste hierarchy. At the top are high-caste Hindus. Below them are alcohol-drinking ( matwali ) castes, which include Mongolian ethnic groups. At the bottom are untouchable Hindu castes that have traditionally performed occupations considered defiling by higher castes. The Newars of the Kathmandu Valley have a caste system that has been absorbed into the national caste hierarchy.

Historically, members of the highest castes have owned the majority of land and enjoyed the greatest political and economic privileges. Members of lower castes have been excluded from political representation and economic opportunities. The untouchable castes were not permitted to own land, and their civil liberties were circumscribed by law. Caste discrimination is officially illegal but has not disappeared. In 1991, 80 percent of positions in the civil service, army, and police were occupied by members of the two highest castes.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

Nepal historically was one of the least urbanized countries in the world, but urbanization is accelerating, especially in the capital, and urban sprawl and pollution have become serious problems. Kathmandu and the neighboring cities of Patan and Bhaktapur are known for pagoda-style and shikhara temples, Buddhist stupas, palaces, and multistory brick houses with elaborately carved wooden door frames and screened windows. Although the largest and most famous buildings are well maintained, many smaller temples and older residential buildings are falling into disrepair.

At the height of British rule in India, the Rana rulers incorporated Western architectural styles into palaces and public buildings. Rana palaces convey a sense of grandeur and clear separation from the peasantry. The current king's palace's scale and fortress-like quality illustrate the distance between king and commoner.

Rural architecture is generally very simple, reflecting the building styles of different caste and ethnic groups, the materials available, and the climate. Rural houses generally have one or two stories and are made of mud brick with a thatched roof. Village houses tend to be clustered in river valleys or along ridge tops.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Many Nepalis do not feel that they have eaten a real meal unless it has included a sizable helping of rice. Most residents eat a large rice meal twice a day, usually at midmorning and in the early evening. Rice generally is served with dal, a lentil dish, and tarkari, a cooked vegetable. Often, the meal includes a pickle achar, made of a fruit or vegetable. In poorer and higher-altitude areas, where rice is scarce, the staple is dhiro, a thick mush made of corn or millet. In areas where wheat is plentiful, rice may be supplemented by flat bread, roti. Most families eat from individual plates while seated on the floor. Though some urbanites use Western utensils, it is more common to eat with the hands.

Conventions regarding eating and drinking are tied to caste. Orthodox high-caste Hindus are strictly vegetarian and do not drink alcohol. Other castes may drink alcohol and eat pork and even beef. Traditionally, caste rules also dictate who may eat with or accept food from whom. Members of the higher castes were particularly reluctant to eat food prepared by strangers. Consequently, eating out has not been a major part of the culture. However, caste rules are relaxing to suit the modern world, and the tourist economy is making restaurants a common feature of urban life.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. At weddings and other important life-cycle events, feasts are generally hosted by the families directly involved, and numerous guests are invited. At such occasions, it is customary to seat guests on woven grass mats on the ground outside one's home, often in lines separating castes and honoring people of high status. Food is served on leaf plates, which can be easily disposed of. These customs, however, like most others, vary by caste-ethnic groups, and are changing rapidly to suit modern tastes.

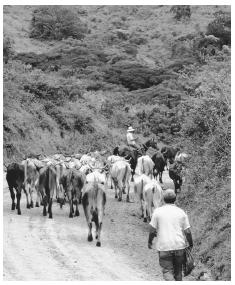

Basic Economy. The large majority of the people are subsistence farmers who grow rice, maize, millet, barley, wheat, and vegetables. At low altitudes, agriculture is the principal means of subsistence, while at higher altitudes agropastoralism prevails. Many households maintain chickens and goats. However, few families own more than a small number of cows, water buffalo, or yaks because the mountainous topography does not provide grazing land for large animals.

Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world. This poverty can be attributed to scarce natural resources, a difficult terrain, landlocked geography, and a weak infrastructure but also to feudal land tenure systems, government corruption, and the ineffectiveness of development efforts. Foreign aid rarely goes to the neediest sectors of the population but is concentrate in urban areas, providing jobs for the urban middle class. The name of the national currency is rupee.

Land Tenure and Property. Historically, a handful of landlords held most agricultural land. Civil servants often were paid in land grants, governing their land on an absentee basis and collecting taxes from tenant-farming peasants. Since the 1950s, efforts have been made to protect the rights of tenants, but without the redistribution of land.

Overpopulation has exacerbated land shortages. Nearly every acre of arable land has been farmed intensively. Deforestation for wood and animal fodder has created serious erosion.

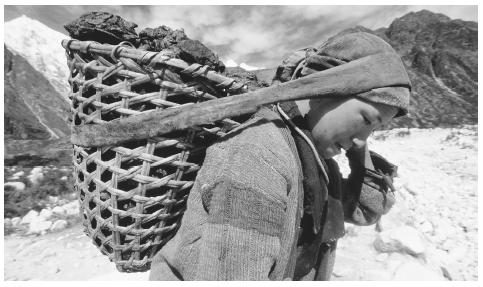

Commercial Activities. The majority of commercial activity takes place at small, family-owned shops or in the stalls of sidewalk vendors. With the exception of locally grown fruits and vegetables, many products are imported from India and, to a lesser extent, China and the West. Jute, sugar, cigarettes, beer, matches, shoes, chemicals, cement, and bricks are produced locally. Carpet and garment manufacturing has increased significantly, providing foreign exchange. Since the late 1950s, tourism has increased rapidly; trekking, mountaineering, white-water rafting, and canoeing have drawn tourists from the West and other parts of Asia. The tourism industry has sparked the commercial production of crafts and souvenirs and created a number of service positions, such as trekking guides and porters. Tourism also has fueled the black market, where drugs are sold and foreign currency is exchanged.

Major Industries. There was no industrial development until the middle of the twentieth century. Much of earliest industrial development was accomplished with the help of private entrepreneurs from India and foreign aid from the Soviet Union, China, and the West. Early development focused on the use of jute, sugar, and tea; modern industries include the manufacturing of brick, tile, and construction materials; paper making; grain processing; vegetable oil extraction; sugar refining; and the brewing of beer.

Trade. Nepal is heavily dependent on trade from India and China. The large majority of imported goods pass through India. Transportation of goods is limited by the terrain. Although roads connect many major commercial centers, in much of the country goods are transported by porters and pack animals. The few roads are difficult to maintain and subject to landslides and flooding. Railroads in the southern flatlands connect many Terai cities to commercial centers in India but do not extend into the hills. Nepal's export goods include carpets, clothing, leather goods, jute, and grain. Tourism is another primary export commodity. Imports include gold, machinery and equipment, petroleum products, and fertilizers.

Division of Labor. Historically, caste was loosely correlated with occupational specialization. Tailors, smiths, and cobblers were the lowest, untouchable castes, and priests and warriors were the two highest Hindu castes. However, the large majority of people are farmers, an occupation that is not caste-specific.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Historically, caste and class status paralleled each other, with the highest castes having the most land, capital, and political influence. The lowest castes could not own property or receive an education. Although caste distinctions are no longer supported by law, caste relations have shaped present-day social stratification: Untouchables continue to be the poorest sector of society, while the upper castes tend to be wealthy and politically dominant. While land is still the principal measure of wealth, some castes that specialize in trade and commerce have fared better under modern capitalism than have landowning castes. Changes in the economic and political system have opened some opportunities for members of historically disadvantaged castes.

Political Life

Government. The Shah dynasty has ruled the country since its unification, except during the Rana period from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century. During the Rana administration, the Shah monarchs were stripped of power and the country was ruled by a series of prime ministers from the Rana noble family. In 1950, the Shah kings were restored to the throne and a constitutional monarchy was established that eventually took the form of the panchayat system. Under this system, political parties were illegal and the country was governed by local and national assemblies controlled by the palace. In 1990, the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (People's Movement) initiated a series of popular demonstrations for democratic reforms, eventually forcing the king to abolish the panchayat system and institute a multiparty democracy.

The country is divided administratively into fourteen zones and seventy-five districts. Local and district-level administers answer to national ministries that are guided by policies set by a bicameral legislature made up of a House of Representatives and a National Council. The majority party in the House of Representatives appoints the prime minister. The executive branch consists of the king and the Council of Ministers.

Leadership and Political Officials. The government is plagued by corruption, and officials often rely on bribes to supplement their income. It is widely believed that influence and employment in government are achieved through personal and family connections. The king is viewed with ambivalence. He and his family have been criticized for corruption and political repression, but photos of the royal family are a popular symbol of national identity and many people think of the king as the living embodiment of the nation and an avatar of the god Vishnu.

Social Problems and Control. International attention has focused on the plight of girls who have been lured or abducted from villages to work as prostitutes in Indian cities and child laborers in carpet factories. Prostitution has increased the spread of AIDS. Foreign boycotts of Nepali carpets have helped curb the use of child labor but have not addressed the larger social problems that force children to become family wage earners.

Military Activity. The military is small and poorly equipped. Its primary purpose is to reinforce the police in maintaining domestic stability. Some Royal Nepal Army personnel have served in United Nations peacekeeping forces. A number of Nepalis, particularly of the hill ethnic groups, have served in Gurkha regiments. To many villagers, service in the British Army represents a significant economic opportunity, and in some areas soldiers' remittances support the local economy.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Aid organizations are involved in health care, family planning, community development, literacy, women's rights, and economic development for low castes and tribal groups. However, many projects are initiated without an understanding of the physical and cultural environment and serve the interests of foreign companies and local elites.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Only men plow, while fetching water is generally considered women's work. Women cook, care for children, wash clothes, and collect firewood and fodder. Men perform the heavier agricultural tasks and often engage in trade, portering, and other work outside the village. Both men and women perform physically demanding labor, but women tend to work longer hours, have less free time, and die younger. In urban areas, men are far more likely to work outside the home. Increasingly, educational opportunities are available to both men and women, and there are women in professional positions. Women also frequently work in family businesses as shopkeepers and seamstresses.

Children and older people are a valuable source of household labor. In rural families, young children collect firewood, mind animals, and watch younger children. Older people may serve on village councils. In urban areas and larger towns, children attend school; rural children may or may not, depending on the proximity of schools, the availability of teachers, and the work required of them at home.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Women often describe themselves as "the lower caste" in relation to men and generally occupy a subordinate social position. However, the freedoms and opportunities available to women vary widely by ethnic group and caste. Women of the highest castes have their public mobility constrained, for their reputation is critical to family and caste honor. Women of lower castes and classes often play a larger wage-earning role, have greater mobility, and are more outspoken around men. Gender roles are slowly shifting in urban areas, where greater numbers of women are receiving an education and joining the work force.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Hindu castes do not generally approve of cross-cousin marriage, which is preferred among some Mongolian ethnic groups. Among some groups, a brideprice substitutes for a dowry. In others, clan exogamy is an important feature of marriages. Until recently, polygyny was legal and relatively common. Now it is illegal and found only in the older generation and in remote areas. Child marriages were considered especially auspicious, and while they continue to be practiced in rural areas, they are now prohibited by law. Love marriage is gaining in popularity in the cities, where romantic films and music inform popular sentiment and the economy offers younger people economic independence from the extended family.

Domestic Unit. Among landholding Hindu castes, a high value is placed on joint family arrangements in which the sons of a household, along with their parents, wives, and children, live together, sharing resources and expenses. Within the household, the old have authority over the young, and men over women. Typically, new daughters-in-law occupy the lowest position. Until a new bride has produced children, she is subject to the hardest work and often the harshest criticism in her husband's household. Older women, often wield a great deal of influence within the household.

The emphasis in joint families is on filial loyalty and agnatic solidarity over individualism. In urban areas, an increasing number of couples are opting for nuclear family arrangements.

Inheritance. Fathers are legally obligated to leave equal portions of land to each son. Daughters do not inherit paternal property unless they remain unmarried past age thirty-five. Although ideally sons manage their father's land together as part of a joint family, familial land tends to be divided, with holdings diminishing in every generation.

Kin Groups. Patrilineal kin groups form the nucleus of households, function as corporate units, and determine inheritance patterns. A man belongs permanently to the kinship group of his father, while a woman changes membership from her natal kin group to the kin group of her husband at the time of marriage. Because family connections are critical in providing access to political influence and economic opportunities, marriage alliances are planned carefully to expand kinship networks and strengthen social ties. Although women join the husband's household, they maintain emotional ties and contact with their families. If a woman is mistreated in her husband's household, she may escape to her father's house or receive support from her male kin. Consequently, women often prefer to marry men from the same villages.

Socialization

Infant Care. Infants are carried on the mothers' back, held by a shawl tied tightly across her chest. Babies are breast-fed on demand, and sleep with their mothers until they are displaced by a new baby or are old enough to share a bed with siblings. Infants and small children often wear amulets and bracelets to protect them from supernatural forces. Parents sometimes line a baby's eyes with kohl to prevent eye infections.

Child Rearing and Education. Mothers are the primary providers of child care, but children also are cared for and socialized by older siblings, cousins, and grandparents. Often children as young as five or six mind younger children. Neighbors are entitled to cuddle, instruct, and discipline children, who are in turn expected to obey and defer to senior members of the family and community. Children address their elders by using the honorific form of Nepali, while adults speak to children using more familiar language. Because authority in households depends on seniority, the relative ages of siblings is important and children are often addressed by birth order.

Certain household rituals mark key stages in child's development, including the first taste of rice and the first haircut. When a girl reaches puberty, she goes through a period of seclusion in which she is prohibited from seeing male family members. Although she may receive special foods and is not expected to work, the experience is an acknowledgment of the pollution associated with female sexuality and reproductivity.

From an early age, children are expected to contribute labor to the household. The law entitles both girls and boys to schooling; however, if a family needs help at home or cannot spare the money for uniforms, books, and school fees, only the sons are sent to school. It is believed that education is wasted on girls, who will marry and take their wage-earning abilities to another household. Boys marry and stay at home, and their education is considered a wise investment.

The customary greeting is to press one's palms together in front of the chest and say namaste ("I greet the god within you"). Men in urban areas have adopted the custom of shaking hands. In the mainstream culture, physical contact between the sexes is not appropriate in public. Although men may be openly affectionate with men and women with women, even married couples do not demonstrate physical affection in public. Some ethnic groups permit more open contact between the sexes.

Hospitality is essential. Guests are always offered food and are not permitted to help with food preparation or cleaning after a meal. It is polite to eat with only the right hand; the hand used to eat food must not touch anything else until it has been thoroughly washed, for saliva is considered defiling. When drinking from a common water vessel, people do not touch the rim to their lips. It is insulting to hit someone with a shoe or sandal, point the soles of one's feet at someone, and step over a person.

Religious Beliefs. Eighty-six percent of Nepalis are Hindus, 8 percent are Buddhists, 4 percent are Muslims, and just over 1 percent are Christians. On a day-to-day level, Hindus practice their religion by "doing puja, " making offerings and prayers to particular deities. While certain days and occasions are designated as auspicious, this form of worship can be performed at any time.

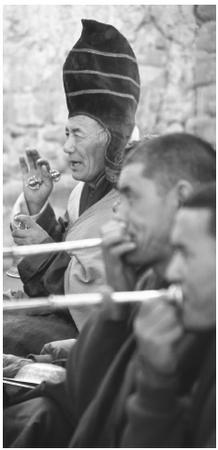

Buddhism is practiced in the Theravadan form. There are two primary Buddhist traditions: the Buddhism of Tibetan refugees and high-altitude ethnic groups with cultural roots in Tibet and the Tantric form practiced by Newars.

There is a strong animistic and shamanic tradition. Belief in ghosts, spirits, and witchcraft is widespread, especially in rural areas. Spiteful witches, hungry ghosts, and angry spirits are thought to inflict illness and misfortune. Shamans mediate between the human and supernatural realms to discover the cause of illness and recommend treatment.

Religious Practitioners. Many forms of Hindu worship do not require the mediation of a priest. At key rites of passage such as weddings and funerals, Brahmin priests read Vedic scriptures and ensure the correct performance of rituals. At temples, priests care for religious icons, which are believed to contain the essence of the deities they represent. They are responsible for ensuring the purity of the temple and overseeing elaborate pujas.

Buddhist monasteries train young initiates in philosophy and meditation. Lay followers gain religious merit by making financial contributions to monasteries, where religious rites are performed on behalf of the general population. Within Buddhism there is a clerical hierarchy, with highly esteemed lamas occupying the positions of greatest influence. Monks and nuns of all ranks shave their heads, wear maroon robes, and embrace a life of celibacy and religious observance.

Rituals and Holy Places. Nepal occupies a special place in both Hindu and Buddhist traditions. According to Hindu mythology, the Himalayas are the abode of the gods, and are specifically associated with Shiva, one of the three principal Hindu deities. Pashupatinath, a large Shiva temple in Kathmandu, is among the holiest sites in Nepal and attracts Hindu pilgrims from all over South Asia. Pashupatinath is only one of thousands of temples and shrines scattered throughout Nepal, however. In the Kathmandu Valley alone, there are hundreds of such shrines, large and small, in which the major gods and goddesses of the Hindu pantheon, as well as local and minor divinities, are worshiped. Many of these shrines are constructed near rivers or at the base of pipal trees, which are themselves considered sacred. For Buddhists, Nepal is significant as the birthplace of Lord Buddha. It is also home to a number of important Buddhist monasteries and supas, including Boudha and Swayambhu, whose domeshaped architecture and painted all-seeing eyes have become symbols of the Kathamandu Valley.

Death and the Afterlife. Hindus and Buddhists believe in reincarnation. An individual's meritorious actions in life will grant him or her a higher rebirth. In both religions the immediate goal is to live virtuously in order to move progressively through higher births and higher states of consciousness. Ultimately, the goal is to attain enlightenment, stopping the cycle of rebirth.

In the Hindu tradition, the dead are cremated, preferably on the banks of a river. It is customary for a son to perform the funeral rites. Some Buddhists also cremate bodies. Others perform what are called "sky burials," in which corpses are cut up and left at sacred sites for vultures to carry away.

Medicine and Health Care

Infant mortality is high, respiratory and intestinal diseases are endemic, and malnutrition is widespread in a country where life expectancy is fifty-seven years. Contributing to this situation are poverty, poor hygiene, and lack of health care. There are hospitals only in urban areas, and they are poorly equipped and unhygienic. Rural health clinics often lack personnel, equipment, and medicines. Western biomedical practices have social prestige, but many poor people cannot afford this type of health care. Many people consult shamans and other religious practitioners. Others look to Ayurvedic medicine, in which illness is thought to be caused by imbalances in the bodily humors. Treatment involves correcting these imbalances, principally through diet. Nepalis combine Ayurvedic, shamanic, biomedical, and other systems.

Although health conditions are poor, malaria has been eradicated. Development efforts have focused on immunization, birth control, and basic medical care. However, the success of all such projects seems to correlate with the education levels of women, which are extremely low.

The Arts and Humanities

Graphic Arts. Much of Nepali art is religious. Newari artisans create cast-bronze statuary of Buddhist and Hindu deities as well as intricately painted tangkas that describe Buddhist cosmology. The creation and contemplation of such art constitutes a religious act.

Performance Arts. Dramatic productions often focus on religious themes drawn from Hindu epics, although political satire and other comedic forms are also popular. There is a rich musical heritage, with a number of distinctive instruments and vocal styles, and music has become an marker of identity for the younger generation. Older people prefer folk and religious music; younger people, especially in urban areas, are attracted to romantic and experimental film music as well as fusions of Western and Asian genres.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Universities are underfunded, faculties are poorly paid, and library resources are meager. Nepalis accord less respect to degrees from universities than to degrees obtained abroad and many scholars seek opportunities to study overseas or in India. Despite these limitations, some fine scholarship has emerged, particularly in the social sciences. In the post-1990 period, political reforms have permitted a more open and critical intellectual environment.

Bibliography

Acharya, Meena, and Lynn Bennett. "The Rural Women of Nepal: An Aggregate Analysis and Summary of Eight Village Studies." The Status of Women in Nepal, 1981.

Adams, Vincanne. Tigers of the Snow and Other Virtual Sherpas: An Ethnography of Himalayan Encounters, 1996.

Ahearn, Laura Marie. "Consent and Coercion: Changing Marriage Practices Among Magars in Nepal." Ph.D. dissertation. University of Michigan, 1994.

Allen, Michael, and S. N. Mukherjee, eds. Women in India and Nepal, 1990.

Bennett, Lynn. Dangerous Wives and Sacred Sisters: Social and Symbolic Roles of High-Caste Women in Nepal, 1983.

Bista, Dor Bahadur. Fatalism and Development: Nepal's Struggle for Modernization, 1991.

Blaikie, Piers, John Cameron, and David Seddon. Nepal in Crisis: Growth and Stagnation at the Periphery, 1978.

Borgstrom, Bengt-Erik. The Patron and the Panca: Village Values and Pancayat Democracy in Nepal, 1980.

Borre, Ole, Sushil R. Pandey, and Chitra K. Tiwari. Nepalese Political Behavior, 1994.

Brown, T. Louise. The Challenge to Democracy in Nepal: A Political History, 1996.

Burghart, Richard. "The Formation of the Concept of Nation-State in Nepal." Journal of Asian Studies, 1984.

Cameron, Mary Margaret. On the Edge of the Auspicious, 1993.

Caplan, Lionel. "Tribes in the Ethnography of Nepal: Some Comments on a Debate." Contributions to Nepalese Studies 17 (2): 129–145, 1990.

Caplan, Patricia. Priests and Cobblers: A Study of Social Change in a Hindu Village in Western Nepal, 1972.

Des Chene, Mary. "Ethnography in the Janajati-yug: Lessons from Reading Rodhi and other Tamu Writings." Studies in Nepali History and Society 1: 97–162, 1996.

Desjarlais, Robert. Body and Emotion: The Aesthetics of Illness and Healing in the Nepal Himalaya, 1992.

Doherty, Victor S. "Kinship and Economic Choice: Modern Adaptations in West Central Nepal." Ph.D. dissertation. University of Wisconsin, Madison, 1975.

Fisher, James F. Sherpas: Reflections on Change in Himalayan Nepal, 1990.

Fricke, Tom. Himalayan Households: Tamang Demography and Domestic Processes, 1994.

——, William G. Axinn, and Arland Thornton. "Marriage, Social Inequality, and Women's Contact with Their Natal Families in Alliance Societies: Two Tamang Examples." American Anthropologist 95 (2): 395–419, 1993.

Furer-Haimendorf, Christoph von. The Sherpas Transformed. Delhi: Sterling, 1984.

——, ed. Caste and Kin in Nepal, India and Ceylon, 1966.

Gaige, Frederick H. Regionalism and National Unity in Nepal, 1975.

Gellner, David N., Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka, and John Whelpton. Nationalism and Ethnicity in a Hindu Kingdom: The Politics of Culture in Contemporary Nepal, 1997.

Ghimire, Premalata. "An Ethnographic Approach to Ritual Ranking Among the Satar." Contributions to Nepalese Studie 17 (2): 103–121, 1990.

Gilbert, Kate. "Women and Family Law in Modern Nepal: Statutory Rights and Social Implications." New York University Journal of International Law and Politics 24: 729–758, 1992.

Goldstein, Melvyn C. "Fraternal Polyandry and Fertility in a High Himalayan Valley in Northwest Nepal." Human Ecology 4 (2): 223–233, 1976.

Gray, John N. The Householder's World: Purity, Power and Dominance in a Nepali Village, 1995.

Gurung, Harka Bahadur. Vignettes of Nepal. Kathmandu: Sajha Prakashan, 1980.

Hagen, Toni. Nepal: The Kingdom in the Himalayas, 1961.

Hitchcock, John. The Magars of Bunyan Hill, 1966.

Hofer, Andras. The Caste Hierarchy and the State in Nepal: A Study of the Muluki Ain of 1854, 1979.

Holmberg, David. Order in Paradox: Myth, Ritual and Exchange among Nepal's Tamang, 1989.

Hutt, Michael. "Drafting the 1990 Constitution." In Michael Hutt, ed., Nepal in the Nineties, 1994.

Iijima, Shigeru. "Hinduization of a Himalayan Tribe in Nepal." Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers 29: 43– 52, 1963.

Jones, Rex, and Shirley Jones. The Himalayan Woman: A Study of Limbu Women in Marriage and Divorce, 1976.

Justice, Judith. Policies, Plans and People: Culture and Health Development in Nepal, 1985.

Karan, Pradyumna P., and Hiroshi Ishii. Nepal: A Himalayan Kingdom in Transition, 1996.

Kondos, Alex. "The Question of 'Corruption' in Nepal." Mankind 17 (1): 15–29, 1987.

Kumar, Dhruba, ed. State Leadership and Politics in Nepal, 1995.

Landan, Perceval. Nepal, 1976.

Levine, Nancy. The Dynamics of Polyandry: Kinship, Domesticity, and Population on the Tibetan Border, 1988.

Levy, Robert I. Mesocosm: Hinduism and the Organization of a Traditional Newar City in Nepal, 1990.

Liechty, Mark. "Paying for Modernity: Women and the Discourse of Freedom in Kathmandu." Studies in Nepali History and Society 1: 201–230, 1996.

MacFarland, Alan. Resources and Population: A Study of the Gurungs of Nepal, 1976.

Manzardo, Andrew E. "To Be Kings of the North: Community, Adaptation, and Impression Management in the Thakali of Western Nepal." Ph.D. dissertation. University of Wisconsin, Madison, 1978.

Messerschmidt, Donald A. "The Thakali of Nepal: Historical Continuity and Socio-Cultural Change." Ethnohistory 29 (4): 265–280, 1982.

Molnar, Augusta. "Women and Politics: Case of the Kham Magar of Western Nepal." American Ethnologist 9 (3): 485–502, 1982.

Nepali, Gopal Singh. The Newars, 1965.

Oldfield, Henry Ambrose. Sketches from Nepal, Historical and Descriptive, 1880, 1974.

Ortner, Sherry B. High Religion: A Cultural and Political History of Sherpa Buddhism, 1989.

Pigg, Stacy Leigh. "Inventing Social Categories through Place: Social Representations and Development in Nepal." Comparative Studies in Society and History 34: 491–513, 1992.

Poudel, P. C., and Rana P. B. Singh. "Pilgrimage and Tourism at Muktinath, Nepal: A Study of Sacrality and Spatial Structure." National Geographical Journal of India 40: 249–268, 1994.

Regmi, Mahesh C. Thatched Huts and Stucco Palaces: Peasants and Landlords in 19th Century Nepal, 1978.

Rosser, Colin. "Social Mobility in the Newar Caste System." In Christoph von Furer-Haimendorf, ed. Caste and Kin in Nepal, India, and Ceylon, 1966.

Shaha, Rishikesh. Politics of Nepal, 1980–1991: Referendum, Stalemate, and Triumph of People Power, 1993.

Shrestha, Nirakar Man. "Alcohol and Drug Abuse in Nepal." British Journal of Addiction 87: 1241–1248, 1992.

Slusser, Mary S. Nepal Mandala: A Cultural Study of the Kathmandu Valley, 1982.

Stevens, Stanley F. Claiming the High Ground: Sherpas, Subsistence and Environmental Change in the Highest Himalaya, 1993.

Stone, Linda. Illness Beliefs and Feeding the Dead in Hindu Nepal: An Ethnographic Analysis, 1988.

Thompson, Julia J. "'There are Many Words to Describe Their Anger': Ritual and Resistance among High-Caste Hindu Women in Kathmandu." In Michael Allen, ed., Anthropology of Nepal: Peoples, Problems, and Processes, 1994.

Tingey, Carol. Auspicious Music in a Changing Society, 1994.

Vansittart, Eden. The Gurkhas, 1890, 1993.

Vinding, Michael. "Making a Living in the Nepal Himalayas: The Case of the Thakali of Mustang District." Contributions to Nepalese Studies 12 (1): 51–105, 1984.

—M ARIE K AMALA N ORMAN

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

Nepali Educate - Educational Resources for Class 11 & 12 Students

Essay on : the socio cultural importance of dashain.

“The socio-cultural importance of Dashain”

D ashain is the biggest festival that Nepal Observe every year a wonderful socio-cultural celebration that allows people time to time reunites and refresh. Socially the same festival is celebrated for 15 days where different cultural rituals take place every day. The Hindu society of Nepal gives huge Priority to this festival. Dashain is the grand celebration from the first day to the fifteenth day.

Culturally Dashain festival signifies the victory of truth and the inspection of happiness. Dashain generally falls on the month of Ashoj (October). Every day has special rituals and activities to be performed. Socio Culturally the festival starts from Ghatasthapana and ends at Vijaya Dashami. On Ghatasthapana people sow rice and barely seeds on the pious corner of their house to grow seedling called Jamara.

The seventh day Phulpati, traditionally on this day the royal Kalash, banana stick, Jamara and sugarcane is carried from Gorkha to Kathmandu by Brahmins. The Eighth day is called as the bloody day of the festival. In this day people cut off the head of 108 goat and 8 buffaloes at the courtyard near the durbar square. Those meats were bought I home and taken as “Parshad”. The ninth day is known a as “Maha Navami”. This day is known as the demon hunting day because member of the defeated demon army try to save themselves by hiding in the bodies of animal and fowls. The tenth day is called as “Vijaya Dashami”. On this day tika is prepared along with Jamara. Elder put tika and Jamara (shown on Ghatsthapna) on the forehead of younger relative to bless them with abundance in upcoming year. Dashain festival is purely a religious celebration. The festival is observed as the victory of truth (goddess) over the devil.

Dashain festival is purely a religious celebration. This is the festival is observed as the victory of truth (goddess) over the devil in ten-day battle. During Navaratri almost all the temple over the country get animal sacrifice. This symbolize the battle between goddess and devil. As the goddess comes victorious over the devil on the tenth day. So, it is observed as the great joy and happiness. Socio Culturally the victory celebration goes until fifteenth day.

Although the festival has rich cultural importance it also has great religious importance. The Hindus in Nepal consider this festival as occasion to bring people together. The Nepalese people living and working in the different part of the world return back to their home in Dashain to be with their family. Dashain festival is also an occasion when you enjoy the cultural impression as traveller it’s certainly a great chance to see and experience thee Nepalese life and culture from close.

Enthusiastic Nepalese often celebrate Dashain festival to celebrate the victory of truth. Dashain has emphasized the importance of family reunion which is helpful to ease social contradiction. All the government agencies, educational institution and other public sectors are closed down during the festival period so as the worker can stay with their family member and increase the happiness among families during the festival. So, it is said that the festival Dashain has the religious and cultural and social importance. It is an occasion of peace and goodwill.

Despite this, Dashain has dark side too. Numerous birds, animals are killed mercifully. People engaged themselves in taking drinks, different beverage and gambling and so on. Some people even celebrate in an expensive and pompous style being in prolonged debt. Due to which social hazard may takes place. This may create a sadful movement for the people who can’t afford all the luxurious event. There is a popular saying in Nepali society “!!! आयो दशैं ढोल बजाइ , गयो दशैं ऋण बोकाई !!!”. So Dashain is just a festival so everyone should make expenses according to their capacity. This will help to make people of all class happy during this great Festival.

About the Author

Post a comment.

Essay on Culture Of Nepal

Students are often asked to write an essay on Culture Of Nepal in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Culture Of Nepal

Introduction.

Nepal, a small country in South Asia, is known for its rich cultural diversity. It is a blend of various ethnic groups, each with unique customs, traditions and languages. This makes the culture of Nepal colorful and fascinating.

Religions in Nepal

Nepal is a religious country with Hinduism and Buddhism being the main faiths. There are also followers of Islam, Christianity, and other religions. These religions influence the daily lives, festivals, and rituals of the Nepalese people.

Languages of Nepal

Nepal is a multilingual country. The official language is Nepali, but more than 123 languages are spoken. Each ethnic group has its own language, adding to the cultural richness.

Traditional Clothing

Nepalese people wear traditional clothing. Men wear ‘Daura Suruwal’ and women wear ‘Sari’ or ‘Kurta Suruwal’. The clothing reflects their ethnic identity and is worn during festivals and special occasions.

Festivals of Nepal

Art and architecture.

Nepalese art and architecture is influenced by Hinduism and Buddhism. Temples, palaces, and sculptures display intricate designs and craftsmanship. This showcases the artistic skills of the Nepalese people.

Cuisine of Nepal

Nepalese cuisine is a mix of flavors. Dal Bhat, a lentil soup with rice, is the staple food. Momos, Gundruk, and Dhido are other popular dishes. Each region has its own special dish, reflecting the diversity.

The culture of Nepal is a beautiful mix of various elements. It is a symbol of unity in diversity. Despite the differences, the people of Nepal live in harmony, respecting each other’s cultures.

250 Words Essay on Culture Of Nepal

Introduction to nepal’s culture.

Nepal, a small country in South Asia, is famous for its rich and diverse culture. It is home to various ethnic groups, each with its unique traditions, languages, and customs. This makes Nepal a place where different cultures blend together, creating a beautiful mix.

Religion and Beliefs

Religion is a big part of life in Nepal. Most people follow Hinduism or Buddhism. These religions influence many aspects of daily life, like food, clothing, and festivals. People visit temples and shrines regularly, showing their deep faith.

Language and Communication

Festivals and celebrations.

Festivals are a major part of Nepal’s culture. They bring joy and unity among people. Dashain, Tihar, and Holi are some of the main festivals. During these times, people gather with family, exchange gifts, and enjoy special meals.

Nepal’s art and architecture are unique and beautiful. You can see this in the temples and old buildings. They are often decorated with detailed carvings and colourful paintings. This highlights the artistic skills of the Nepalese people.

Food and Cuisine

In conclusion, Nepal’s culture is a colourful mix of traditions, beliefs, and customs. It is a symbol of unity in diversity, making Nepal a truly special place.

500 Words Essay on Culture Of Nepal

Introduction to nepalese culture.

Nepal, a small country nestled in the heart of the Himalayas, is known for its rich and vibrant culture. The culture of Nepal is a unique mix of tradition and novelty. It is a fusion of ancient history and modern influences. The culture is deeply rooted in the people, their rituals, their beliefs, and their daily lives.

Religions and Festivals

Language and literature.

Language is an essential part of any culture, and Nepal is no exception. The official language is Nepali, but more than 123 languages are spoken here. This shows the cultural richness and diversity of the country. Nepalese literature is also diverse, with works ranging from ancient scriptures and epics to modern novels and poetry.

Nepal is famous for its distinctive art and architecture. The country is full of ancient temples, palaces, and monuments that reflect the skills of the Newar artisans. Kathmandu Valley, in particular, is a treasure trove of such architectural wonders. The intricate woodwork, stone carvings, and metal crafts are a testament to the artistic prowess of the Nepalese people.

Nepalese cuisine is as diverse as its culture. The food varies from region to region. Dal Bhat (lentil soup with rice), Gundruk (fermented leafy greens), and Momo (dumplings) are some popular dishes. The food is not just about taste but also carries cultural and religious significance.

Music and Dance

Music and dance form an integral part of Nepalese culture. Folk music and dances are popular, with each ethnic group having its unique music and dance forms. Instruments like Madal and Sarangi are commonly used. The dances are usually performed during festivals and special occasions, adding color and rhythm to the celebrations.

Clothing and Attire

Traditional Nepalese clothing is unique and varied. Men typically wear Daura Suruwal while women wear Gunyu Cholo. These outfits are often worn during festivals and special occasions. The clothing reflects the country’s cultural heritage and identity.

In conclusion, the culture of Nepal is a beautiful blend of various elements. It is a culture that respects diversity and celebrates unity. It is a culture that values tradition while embracing change. The culture of Nepal is a mirror of its people – warm, welcoming, and vibrant.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Status of Women in Nepal: A Critical Analysis of Transformational Trajectories

- December 2020

- Nepalese Journal of Development and Rural Studies 17:123-127

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Aashiyana Adhikari

- Cindy Davis

- Madhu Koirala Dhital

- Govind Kamal Dhital

- Kamala Bhandari

- Sally E. Wier

- Binda Pandey

- Margaret Becker

- Ruth Vanita

- AM ANTHROPOL

- I. C. Jarvie

- Kimberly Rubenfeld

- Asian Development Bank

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

A Devoted Son Exercise : Summary and Question Answers

Share this article, a devoted son, understanding the text, answer the following questions., a. how did the morning papers bring an ambience of celebration to the varma family, b. how did the community celebrate rakesh’s success, c. why was rakesh’s success a special matter of discussion in the neighbourhood, d. how does the author make fun with the words ‘america’ and ‘the usa’, e. how does the author characterize rakesh’s wife, f. describe how rakesh rises in his career., g. how does the author describe rakesh’s family background, h. what is the impact of rakesh’s mother’s death on his father, i. what did rakesh do to make his father’s old age more comfortable, j. why did the old man try to bribe his grandchildren, k. are mr. varma’s complaints about his diets reasonable how.

You can download our android app using below button to get offline access to the notes directly from your phone.

Reference to the Context