- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- HIV and AIDS

- Hypertension

- Mental disorders

- Top 10 causes of death

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- Data collection tools

- Global Health Observatory

- Insights and visualizations

- COVID excess deaths

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

Impact of COVID-19 on people's livelihoods, their health and our food systems

Joint statement by ilo, fao, ifad and who.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a dramatic loss of human life worldwide and presents an unprecedented challenge to public health, food systems and the world of work. The economic and social disruption caused by the pandemic is devastating: tens of millions of people are at risk of falling into extreme poverty, while the number of undernourished people, currently estimated at nearly 690 million, could increase by up to 132 million by the end of the year.

Millions of enterprises face an existential threat. Nearly half of the world’s 3.3 billion global workforce are at risk of losing their livelihoods. Informal economy workers are particularly vulnerable because the majority lack social protection and access to quality health care and have lost access to productive assets. Without the means to earn an income during lockdowns, many are unable to feed themselves and their families. For most, no income means no food, or, at best, less food and less nutritious food.

The pandemic has been affecting the entire food system and has laid bare its fragility. Border closures, trade restrictions and confinement measures have been preventing farmers from accessing markets, including for buying inputs and selling their produce, and agricultural workers from harvesting crops, thus disrupting domestic and international food supply chains and reducing access to healthy, safe and diverse diets. The pandemic has decimated jobs and placed millions of livelihoods at risk. As breadwinners lose jobs, fall ill and die, the food security and nutrition of millions of women and men are under threat, with those in low-income countries, particularly the most marginalized populations, which include small-scale farmers and indigenous peoples, being hardest hit.

Millions of agricultural workers – waged and self-employed – while feeding the world, regularly face high levels of working poverty, malnutrition and poor health, and suffer from a lack of safety and labour protection as well as other types of abuse. With low and irregular incomes and a lack of social support, many of them are spurred to continue working, often in unsafe conditions, thus exposing themselves and their families to additional risks. Further, when experiencing income losses, they may resort to negative coping strategies, such as distress sale of assets, predatory loans or child labour. Migrant agricultural workers are particularly vulnerable, because they face risks in their transport, working and living conditions and struggle to access support measures put in place by governments. Guaranteeing the safety and health of all agri-food workers – from primary producers to those involved in food processing, transport and retail, including street food vendors – as well as better incomes and protection, will be critical to saving lives and protecting public health, people’s livelihoods and food security.

In the COVID-19 crisis food security, public health, and employment and labour issues, in particular workers’ health and safety, converge. Adhering to workplace safety and health practices and ensuring access to decent work and the protection of labour rights in all industries will be crucial in addressing the human dimension of the crisis. Immediate and purposeful action to save lives and livelihoods should include extending social protection towards universal health coverage and income support for those most affected. These include workers in the informal economy and in poorly protected and low-paid jobs, including youth, older workers, and migrants. Particular attention must be paid to the situation of women, who are over-represented in low-paid jobs and care roles. Different forms of support are key, including cash transfers, child allowances and healthy school meals, shelter and food relief initiatives, support for employment retention and recovery, and financial relief for businesses, including micro, small and medium-sized enterprises. In designing and implementing such measures it is essential that governments work closely with employers and workers.

Countries dealing with existing humanitarian crises or emergencies are particularly exposed to the effects of COVID-19. Responding swiftly to the pandemic, while ensuring that humanitarian and recovery assistance reaches those most in need, is critical.

Now is the time for global solidarity and support, especially with the most vulnerable in our societies, particularly in the emerging and developing world. Only together can we overcome the intertwined health and social and economic impacts of the pandemic and prevent its escalation into a protracted humanitarian and food security catastrophe, with the potential loss of already achieved development gains.

We must recognize this opportunity to build back better, as noted in the Policy Brief issued by the United Nations Secretary-General. We are committed to pooling our expertise and experience to support countries in their crisis response measures and efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. We need to develop long-term sustainable strategies to address the challenges facing the health and agri-food sectors. Priority should be given to addressing underlying food security and malnutrition challenges, tackling rural poverty, in particular through more and better jobs in the rural economy, extending social protection to all, facilitating safe migration pathways and promoting the formalization of the informal economy.

We must rethink the future of our environment and tackle climate change and environmental degradation with ambition and urgency. Only then can we protect the health, livelihoods, food security and nutrition of all people, and ensure that our ‘new normal’ is a better one.

Media Contacts

Kimberly Chriscaden

Communications Officer World Health Organization

Nutrition and Food Safety (NFS) and COVID-19

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

student opinion

How Is the Coronavirus Outbreak Affecting Your Life?

How are you staying connected and sane in a time of social distancing?

By Jeremy Engle

Find all our Student Opinion questions here.

Note: The Times Opinion section is working on an article about how the coronavirus outbreak has disrupted the lives of high school students. To share your story, fill out this form .

The coronavirus has changed how we work , play and learn : Schools are closing, sports leagues have been canceled, and many people have been asked to work from home.

On March 16, the Trump administration released new guidelines to slow the spread of the coronavirus, including closing schools and avoiding groups of more than 10 people, discretionary travel, bars, restaurants and food courts.

How are you dealing with these sudden and dramatic changes to how we live? Are you practicing social distancing — and are you even sure what that really means?

In “ Wondering About Social Distancing? ” Apoorva Mandavilli explains the term and offers practical guidance from experts:

What is social distancing? Put simply, the idea is to maintain a distance between you and other people — in this case, at least six feet. That also means minimizing contact with people. Avoid public transportation whenever possible, limit nonessential travel, work from home and skip social gatherings — and definitely do not go to crowded bars and sporting arenas. “Every single reduction in the number of contacts you have per day with relatives, with friends, co-workers, in school will have a significant impact on the ability of the virus to spread in the population,” said Dr. Gerardo Chowell, chair of population health sciences at Georgia State University. This strategy saved thousands of lives both during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 and, more recently, in Mexico City during the 2009 flu pandemic.

The article continues with expert responses to some common questions about social distancing. Here are excerpts from three:

I’m young and don’t have any risk factors. Can I continue to socialize? Please don’t. There is no question that older people and those with underlying health conditions are most vulnerable to the virus, but young people are by no means immune. And there is a greater public health imperative. Even people who show only mild symptoms may pass the virus to many, many others — particularly in the early course of the infection, before they even realize they are sick. So you might keep the chain of infection going right to your own older or high-risk relatives. You may also contribute to the number of people infected, causing the pandemic to grow rapidly and overwhelm the health care system. If you ignore the guidance on social distancing, you will essentially put yourself and everyone else at much higher risk. Experts acknowledged that social distancing is tough, especially for young people who are used to gathering in groups. But even cutting down the number of gatherings, and the number of people in any group, will help. Can I leave my house? Absolutely. The experts were unanimous in their answer to this question. It’s O.K. to go outdoors for fresh air and exercise — to walk your dog, go for a hike or ride your bicycle, for example. The point is not to remain indoors, but to avoid being in close contact with people. You may also need to leave the house for medicines or other essential resources. But there are things you can do to keep yourself and others safe during and after these excursions. When you do leave your home, wipe down any surfaces you come into contact with, disinfect your hands with an alcohol-based sanitizer and avoid touching your face. Above all, frequently wash your hands — especially whenever you come in from outside, before you eat or before you’re in contact with the very old or very young. How long will we need to practice social distancing? That is a big unknown, experts said. A lot will depend on how well the social distancing measures in place work and how much we can slow the pandemic down. But prepare to hunker down for at least a month, and possibly much longer. In Seattle, the recommendations on social distancing have continued to escalate with the number of infections and deaths, and as the health system has become increasingly strained. “For now, it’s probably indefinite,” Dr. Marrazzo said. “We’re in uncharted territory.”

Abdullah Shihipar writes in an Opinion essay, “ Coronavirus and the Isolation Paradox ,” that while social distancing is required to prevent infection, loneliness can make us sick:

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

8 Lessons We Can Learn From the COVID-19 Pandemic

BY KATHY KATELLA May 14, 2021

Note: Information in this article was accurate at the time of original publication. Because information about COVID-19 changes rapidly, we encourage you to visit the websites of the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), and your state and local government for the latest information.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed life as we know it—and it may have changed us individually as well, from our morning routines to our life goals and priorities. Many say the world has changed forever. But this coming year, if the vaccines drive down infections and variants are kept at bay, life could return to some form of normal. At that point, what will we glean from the past year? Are there silver linings or lessons learned?

“Humanity's memory is short, and what is not ever-present fades quickly,” says Manisha Juthani, MD , a Yale Medicine infectious diseases specialist. The bubonic plague, for example, ravaged Europe in the Middle Ages—resurfacing again and again—but once it was under control, people started to forget about it, she says. “So, I would say one major lesson from a public health or infectious disease perspective is that it’s important to remember and recognize our history. This is a period we must remember.”

We asked our Yale Medicine experts to weigh in on what they think are lessons worth remembering, including those that might help us survive a future virus or nurture a resilience that could help with life in general.

Lesson 1: Masks are useful tools

What happened: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) relaxed its masking guidance for those who have been fully vaccinated. But when the pandemic began, it necessitated a global effort to ensure that everyone practiced behaviors to keep themselves healthy and safe—and keep others healthy as well. This included the widespread wearing of masks indoors and outside.

What we’ve learned: Not everyone practiced preventive measures such as mask wearing, maintaining a 6-foot distance, and washing hands frequently. But, Dr. Juthani says, “I do think many people have learned a whole lot about respiratory pathogens and viruses, and how they spread from one person to another, and that sort of old-school common sense—you know, if you don’t feel well—whether it’s COVID-19 or not—you don’t go to the party. You stay home.”

Masks are a case in point. They are a key COVID-19 prevention strategy because they provide a barrier that can keep respiratory droplets from spreading. Mask-wearing became more common across East Asia after the 2003 SARS outbreak in that part of the world. “There are many East Asian cultures where the practice is still that if you have a cold or a runny nose, you put on a mask,” Dr. Juthani says.

She hopes attitudes in the U.S. will shift in that direction after COVID-19. “I have heard from a number of people who are amazed that we've had no flu this year—and they know masks are one of the reasons,” she says. “They’ve told me, ‘When the winter comes around, if I'm going out to the grocery store, I may just put on a mask.’”

Lesson 2: Telehealth might become the new normal

What happened: Doctors and patients who have used telehealth (technology that allows them to conduct medical care remotely), found it can work well for certain appointments, ranging from cardiology check-ups to therapy for a mental health condition. Many patients who needed a medical test have also discovered it may be possible to substitute a home version.

What we’ve learned: While there are still problems for which you need to see a doctor in person, the pandemic introduced a new urgency to what had been a gradual switchover to platforms like Zoom for remote patient visits.

More doctors also encouraged patients to track their blood pressure at home , and to use at-home equipment for such purposes as diagnosing sleep apnea and even testing for colon cancer . Doctors also can fine-tune cochlear implants remotely .

“It happened very quickly,” says Sharon Stoll, DO, a neurologist. One group that has benefitted is patients who live far away, sometimes in other parts of the country—or even the world, she says. “I always like to see my patients at least twice a year. Now, we can see each other in person once a year, and if issues come up, we can schedule a telehealth visit in-between,” Dr. Stoll says. “This way I may hear about an issue before it becomes a problem, because my patients have easier access to me, and I have easier access to them.”

Meanwhile, insurers are becoming more likely to cover telehealth, Dr. Stoll adds. “That is a silver lining that will hopefully continue.”

Lesson 3: Vaccines are powerful tools

What happened: Given the recent positive results from vaccine trials, once again vaccines are proving to be powerful for preventing disease.

What we’ve learned: Vaccines really are worth getting, says Dr. Stoll, who had COVID-19 and experienced lingering symptoms, including chronic headaches . “I have lots of conversations—and sometimes arguments—with people about vaccines,” she says. Some don’t like the idea of side effects. “I had vaccine side effects and I’ve had COVID-19 side effects, and I say nothing compares to the actual illness. Unfortunately, I speak from experience.”

Dr. Juthani hopes the COVID-19 vaccine spotlight will motivate people to keep up with all of their vaccines, including childhood and adult vaccines for such diseases as measles , chicken pox, shingles , and other viruses. She says people have told her they got the flu vaccine this year after skipping it in previous years. (The CDC has reported distributing an exceptionally high number of doses this past season.)

But, she cautions that a vaccine is not a magic bullet—and points out that scientists can’t always produce one that works. “As advanced as science is, there have been multiple failed efforts to develop a vaccine against the HIV virus,” she says. “This time, we were lucky that we were able build on the strengths that we've learned from many other vaccine development strategies to develop multiple vaccines for COVID-19 .”

Lesson 4: Everyone is not treated equally, especially in a pandemic

What happened: COVID-19 magnified disparities that have long been an issue for a variety of people.

What we’ve learned: Racial and ethnic minority groups especially have had disproportionately higher rates of hospitalization for COVID-19 than non-Hispanic white people in every age group, and many other groups faced higher levels of risk or stress. These groups ranged from working mothers who also have primary responsibility for children, to people who have essential jobs, to those who live in rural areas where there is less access to health care.

“One thing that has been recognized is that when people were told to work from home, you needed to have a job that you could do in your house on a computer,” says Dr. Juthani. “Many people who were well off were able do that, but they still needed to have food, which requires grocery store workers and truck drivers. Nursing home residents still needed certified nursing assistants coming to work every day to care for them and to bathe them.”

As far as racial inequities, Dr. Juthani cites President Biden’s appointment of Yale Medicine’s Marcella Nunez-Smith, MD, MHS , as inaugural chair of a federal COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force. “Hopefully the new focus is a first step,” Dr. Juthani says.

Lesson 5: We need to take mental health seriously

What happened: There was a rise in reported mental health problems that have been described as “a second pandemic,” highlighting mental health as an issue that needs to be addressed.

What we’ve learned: Arman Fesharaki-Zadeh, MD, PhD , a behavioral neurologist and neuropsychiatrist, believes the number of mental health disorders that were on the rise before the pandemic is surging as people grapple with such matters as juggling work and childcare, job loss, isolation, and losing a loved one to COVID-19.

The CDC reports that the percentage of adults who reported symptoms of anxiety of depression in the past 7 days increased from 36.4 to 41.5 % from August 2020 to February 2021. Other reports show that having COVID-19 may contribute, too, with its lingering or long COVID symptoms, which can include “foggy mind,” anxiety , depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder .

“We’re seeing these problems in our clinical setting very, very often,” Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh says. “By virtue of necessity, we can no longer ignore this. We're seeing these folks, and we have to take them seriously.”

Lesson 6: We have the capacity for resilience

What happened: While everyone’s situation is different (and some people have experienced tremendous difficulties), many have seen that it’s possible to be resilient in a crisis.

What we’ve learned: People have practiced self-care in a multitude of ways during the pandemic as they were forced to adjust to new work schedules, change their gym routines, and cut back on socializing. Many started seeking out new strategies to counter the stress.

“I absolutely believe in the concept of resilience, because we have this effective reservoir inherent in all of us—be it the product of evolution, or our ancestors going through catastrophes, including wars, famines, and plagues,” Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh says. “I think inherently, we have the means to deal with crisis. The fact that you and I are speaking right now is the result of our ancestors surviving hardship. I think resilience is part of our psyche. It's part of our DNA, essentially.”

Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh believes that even small changes are highly effective tools for creating resilience. The changes he suggests may sound like the same old advice: exercise more, eat healthy food, cut back on alcohol, start a meditation practice, keep up with friends and family. “But this is evidence-based advice—there has been research behind every one of these measures,” he says.

But we have to also be practical, he notes. “If you feel overwhelmed by doing too many things, you can set a modest goal with one new habit—it could be getting organized around your sleep. Once you’ve succeeded, move on to another one. Then you’re building momentum.”

Lesson 7: Community is essential—and technology is too

What happened: People who were part of a community during the pandemic realized the importance of human connection, and those who didn’t have that kind of support realized they need it.

What we’ve learned: Many of us have become aware of how much we need other people—many have managed to maintain their social connections, even if they had to use technology to keep in touch, Dr. Juthani says. “There's no doubt that it's not enough, but even that type of community has helped people.”

Even people who aren’t necessarily friends or family are important. Dr. Juthani recalled how she encouraged her mail carrier to sign up for the vaccine, soon learning that the woman’s mother and husband hadn’t gotten it either. “They are all vaccinated now,” Dr. Juthani says. “So, even by word of mouth, community is a way to make things happen.”

It’s important to note that some people are naturally introverted and may have enjoyed having more solitude when they were forced to stay at home—and they should feel comfortable with that, Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh says. “I think one has to keep temperamental tendencies like this in mind.”

But loneliness has been found to suppress the immune system and be a precursor to some diseases, he adds. “Even for introverted folks, the smallest circle is preferable to no circle at all,” he says.

Lesson 8: Sometimes you need a dose of humility

What happened: Scientists and nonscientists alike learned that a virus can be more powerful than they are. This was evident in the way knowledge about the virus changed over time in the past year as scientific investigation of it evolved.

What we’ve learned: “As infectious disease doctors, we were resident experts at the beginning of the pandemic because we understand pathogens in general, and based on what we’ve seen in the past, we might say there are certain things that are likely to be true,” Dr. Juthani says. “But we’ve seen that we have to take these pathogens seriously. We know that COVID-19 is not the flu. All these strokes and clots, and the loss of smell and taste that have gone on for months are things that we could have never known or predicted. So, you have to have respect for the unknown and respect science, but also try to give scientists the benefit of the doubt,” she says.

“We have been doing the best we can with the knowledge we have, in the time that we have it,” Dr. Juthani says. “I think most of us have had to have the humility to sometimes say, ‘I don't know. We're learning as we go.’"

Information provided in Yale Medicine articles is for general informational purposes only. No content in the articles should ever be used as a substitute for medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician. Always seek the individual advice of your health care provider with any questions you have regarding a medical condition.

More news from Yale Medicine

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

In Their Own Words, Americans Describe the Struggles and Silver Linings of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The outbreak has dramatically changed americans’ lives and relationships over the past year. we asked people to tell us about their experiences – good and bad – in living through this moment in history..

Pew Research Center has been asking survey questions over the past year about Americans’ views and reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic. In August, we gave the public a chance to tell us in their own words how the pandemic has affected them in their personal lives. We wanted to let them tell us how their lives have become more difficult or challenging, and we also asked about any unexpectedly positive events that might have happened during that time.

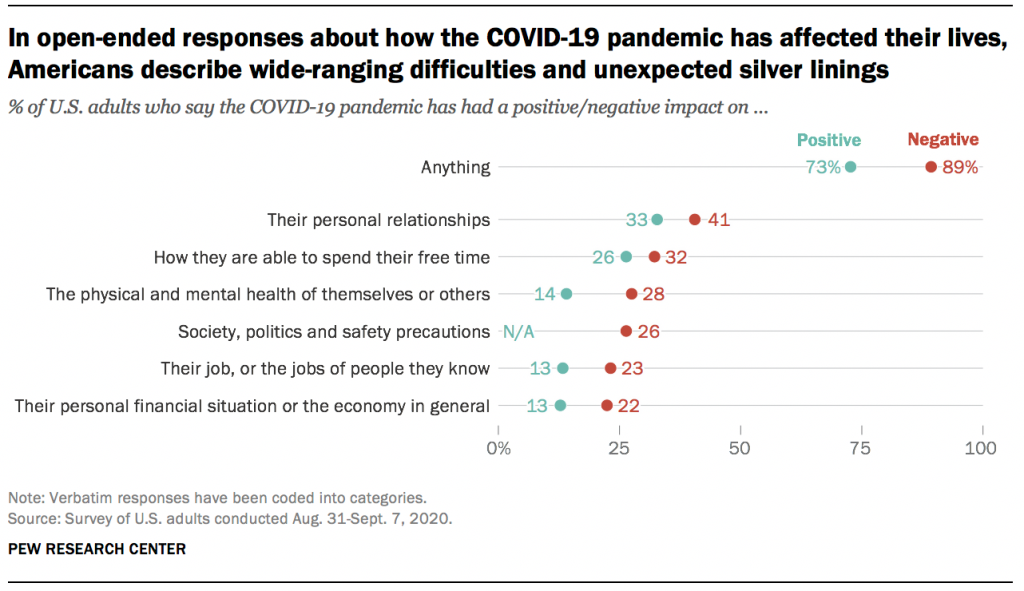

The vast majority of Americans (89%) mentioned at least one negative change in their own lives, while a smaller share (though still a 73% majority) mentioned at least one unexpected upside. Most have experienced these negative impacts and silver linings simultaneously: Two-thirds (67%) of Americans mentioned at least one negative and at least one positive change since the pandemic began.

For this analysis, we surveyed 9,220 U.S. adults between Aug. 31-Sept. 7, 2020. Everyone who completed the survey is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Respondents to the survey were asked to describe in their own words how their lives have been difficult or challenging since the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak, and to describe any positive aspects of the situation they have personally experienced as well. Overall, 84% of respondents provided an answer to one or both of the questions. The Center then categorized a random sample of 4,071 of their answers using a combination of in-house human coders, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service and keyword-based pattern matching. The full methodology and questions used in this analysis can be found here.

In many ways, the negatives clearly outweigh the positives – an unsurprising reaction to a pandemic that had killed more than 180,000 Americans at the time the survey was conducted. Across every major aspect of life mentioned in these responses, a larger share mentioned a negative impact than mentioned an unexpected upside. Americans also described the negative aspects of the pandemic in greater detail: On average, negative responses were longer than positive ones (27 vs. 19 words). But for all the difficulties and challenges of the pandemic, a majority of Americans were able to think of at least one silver lining.

Both the negative and positive impacts described in these responses cover many aspects of life, none of which were mentioned by a majority of Americans. Instead, the responses reveal a pandemic that has affected Americans’ lives in a variety of ways, of which there is no “typical” experience. Indeed, not all groups seem to have experienced the pandemic equally. For instance, younger and more educated Americans were more likely to mention silver linings, while women were more likely than men to mention challenges or difficulties.

Here are some direct quotes that reveal how Americans are processing the new reality that has upended life across the country.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Illustration by Tomi Um

The Pandemic's Effects on Everyday Life

Boston College researchers are exploring COVID-19's impact on life as we know it. Here’s a look at just some of the important questions they’re asking—and answering.

Is remote work here to stay?

As many as 60 percent of U.S. employees are estimated to have worked remotely at some point during the pandemic, a shift that could lead to “profound transformations in mindsets around work and life as we know it,” said Assistant Professor of Sociology Wen Fan. In a project funded by the National Science Foundation, Fan is exploring the changing nature of work and remote workers’ experiences and preferences, as well as disparities in remote-working conditions and work-family balance by gender, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity, which could inform social policies moving forward. Though the team has just begun analyzing the data, Fan says one respondent’s thoughts—“It’s a fickle thing, sometimes you love it, sometimes you hate it”— captures the overall sentiment so far.

Are kids now spending too much time with screens?

When schools and daycares closed abruptly, kids began spending much more time engaged with cell phones and computers.“Screens are the babysitter of last resort,” said BC psychologist Joshua Hartshorne, coauthor of the study “Screen Time as an Index of Family Distress.” Whereas lower screen-time rates before the pandemic were thought to be a function of well- informed parenting, it’s now clear that they were also due to well-resourced parenting, he said. The next phase of the project, funded by the National Science Foundation, will examine whether screen time is actually problematic for child development.

Can we safely reuse PPE?

The pandemic revealed a severe national shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE). So when the CDC made the unprecedented recommendation to reuse N95 respirators, a team from the Connell School’s new Doctor of Nursing Practice program— Jacqueline Sly, Beth McNutt-Clarke, Nanci Haze, and Allan Thomas—created a three-minute YouTube video and guide illustrating how to don, doff, store, and then redon the masks. Their materials are now part of clinical orientation for nursing students, and the team also shared their guidelines and experiences training their colleagues in them in American Nurse and Nursing Management .

What does science say about masks?

Masks are the most important public-health tool for containing the pandemic, according to BC Law School Associate Professor Dean Hashimoto. His new book, The Case for Masks , presents situations in which wearing (or not wearing) face coverings directly affected how many people got sick. One case study focuses on the Mass General Brigham healthcare network, where Hashimoto is the chief medical officer for occupational health services. When the network required patients and 78,000 employees at its hospitals to mask up last March, there was a linear decline in COVID-19 cases among healthcare workers.

Has language development been affected?

For kids, the pandemic has meant time away from school and friends. To find out if this would affect language development, BC psychologist Joshua Hartshorne and a University of Maryland colleague created the KidTalk app ( kidtalkscrapbook.org ), a tool that allows parents to record conversations and track their children’s speech development. The data could be used by policymakers to support families after the pandemic. “The more we understand how this affects children,” Hartshorne said, “the better we can plan.”

What happens when the earth goes quiet?

There’s been much less human activity during the pandemic lockdowns—so much so that scientists recorded a drop of up to 50 percent in human-induced seismic vibrations of the earth beneath us in early 2020. Associate Professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences Alan Kafka was one of seventy-six scientists from two dozen countries who reported these results in Science . “It is culturally quieter, so we can explore the finer details of natural seismic phenomena that might otherwise be hidden,” said Kafka, who shared data from BC’s Weston Observatory, as well as from two seismometers on campus.

For more pandemic-related research from across Boston College, see sites.bc.edu/responding-to-covid-19 .

More Stories

Menstrual Care with a Conscience

Katie Diasti ’19 is creating earth-friendly and toxin-free pads and tampons.

Breaking the Cycle

Professor Catherine Taylor is testing strategies to prevent spanking and its negative outcomes.

A Billion to None

Reeves Wiedeman ’08 traces the rise and fall of the new-economy darling WeWork.

Hockey for All

Former NWHL player Blake Bolden ’13 is determined to diversify the sport she loves.

- COVID-19 and your mental health

Worries and anxiety about COVID-19 can be overwhelming. Learn ways to cope as COVID-19 spreads.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, life for many people changed very quickly. Worry and concern were natural partners of all that change — getting used to new routines, loneliness and financial pressure, among other issues. Information overload, rumor and misinformation didn't help.

Worldwide surveys done in 2020 and 2021 found higher than typical levels of stress, insomnia, anxiety and depression. By 2022, levels had lowered but were still higher than before 2020.

Though feelings of distress about COVID-19 may come and go, they are still an issue for many people. You aren't alone if you feel distress due to COVID-19. And you're not alone if you've coped with the stress in less than healthy ways, such as substance use.

But healthier self-care choices can help you cope with COVID-19 or any other challenge you may face.

And knowing when to get help can be the most essential self-care action of all.

Recognize what's typical and what's not

Stress and worry are common during a crisis. But something like the COVID-19 pandemic can push people beyond their ability to cope.

In surveys, the most common symptoms reported were trouble sleeping and feeling anxiety or nervous. The number of people noting those symptoms went up and down in surveys given over time. Depression and loneliness were less common than nervousness or sleep problems, but more consistent across surveys given over time. Among adults, use of drugs, alcohol and other intoxicating substances has increased over time as well.

The first step is to notice how often you feel helpless, sad, angry, irritable, hopeless, anxious or afraid. Some people may feel numb.

Keep track of how often you have trouble focusing on daily tasks or doing routine chores. Are there things that you used to enjoy doing that you stopped doing because of how you feel? Note any big changes in appetite, any substance use, body aches and pains, and problems with sleep.

These feelings may come and go over time. But if these feelings don't go away or make it hard to do your daily tasks, it's time to ask for help.

Get help when you need it

If you're feeling suicidal or thinking of hurting yourself, seek help.

- Contact your healthcare professional or a mental health professional.

- Contact a suicide hotline. In the U.S., call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline , available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Or use the Lifeline Chat . Services are free and confidential.

If you are worried about yourself or someone else, contact your healthcare professional or mental health professional. Some may be able to see you in person or talk over the phone or online.

You also can reach out to a friend or loved one. Someone in your faith community also could help.

And you may be able to get counseling or a mental health appointment through an employer's employee assistance program.

Another option is information and treatment options from groups such as:

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Self-care tips

Some people may use unhealthy ways to cope with anxiety around COVID-19. These unhealthy choices may include things such as misuse of medicines or legal drugs and use of illegal drugs. Unhealthy coping choices also can be things such as sleeping too much or too little, or overeating. It also can include avoiding other people and focusing on only one soothing thing, such as work, television or gaming.

Unhealthy coping methods can worsen mental and physical health. And that is particularly true if you're trying to manage or recover from COVID-19.

Self-care actions can help you restore a healthy balance in your life. They can lessen everyday stress or significant anxiety linked to events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Self-care actions give your body and mind a chance to heal from the problems long-term stress can cause.

Take care of your body

Healthy self-care tips start with the basics. Give your body what it needs and avoid what it doesn't need. Some tips are:

- Get the right amount of sleep for you. A regular sleep schedule, when you go to bed and get up at similar times each day, can help avoid sleep problems.

- Move your body. Regular physical activity and exercise can help reduce anxiety and improve mood. Any activity you can do regularly is a good choice. That may be a scheduled workout, a walk or even dancing to your favorite music.

- Choose healthy food and drinks. Foods that are high in nutrients, such as protein, vitamins and minerals are healthy choices. Avoid food or drink with added sugar, fat or salt.

- Avoid tobacco, alcohol and drugs. If you smoke tobacco or if you vape, you're already at higher risk of lung disease. Because COVID-19 affects the lungs, your risk increases even more. Using alcohol to manage how you feel can make matters worse and reduce your coping skills. Avoid taking illegal drugs or misusing prescriptions to manage your feelings.

Take care of your mind

Healthy coping actions for your brain start with deciding how much news and social media is right for you. Staying informed, especially during a pandemic, helps you make the best choices but do it carefully.

Set aside a specific amount of time to find information in the news or on social media, stay limited to that time, and choose reliable sources. For example, give yourself up to 20 or 30 minutes a day of news and social media. That amount keeps people informed but not overwhelmed.

For COVID-19, consider reliable health sources. Examples are the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Other healthy self-care tips are:

- Relax and recharge. Many people benefit from relaxation exercises such as mindfulness, deep breathing, meditation and yoga. Find an activity that helps you relax and try to do it every day at least for a short time. Fitting time in for hobbies or activities you enjoy can help manage feelings of stress too.

- Stick to your health routine. If you see a healthcare professional for mental health services, keep up with your appointments. And stay up to date with all your wellness tests and screenings.

- Stay in touch and connect with others. Family, friends and your community are part of a healthy mental outlook. Together, you form a healthy support network for concerns or challenges. Social interactions, over time, are linked to a healthier and longer life.

Avoid stigma and discrimination

Stigma can make people feel isolated and even abandoned. They may feel sad, hurt and angry when people in their community avoid them for fear of getting COVID-19. People who have experienced stigma related to COVID-19 include people of Asian descent, health care workers and people with COVID-19.

Treating people differently because of their medical condition, called medical discrimination, isn't new to the COVID-19 pandemic. Stigma has long been a problem for people with various conditions such as Hansen's disease (leprosy), HIV, diabetes and many mental illnesses.

People who experience stigma may be left out or shunned, treated differently, or denied job and school options. They also may be targets of verbal, emotional and physical abuse.

Communication can help end stigma or discrimination. You can address stigma when you:

- Get to know people as more than just an illness. Using respectful language can go a long way toward making people comfortable talking about a health issue.

- Get the facts about COVID-19 or other medical issues from reputable sources such as the CDC and WHO.

- Speak up if you hear or see myths about an illness or people with an illness.

COVID-19 and health

The virus that causes COVID-19 is still a concern for many people. By recognizing when to get help and taking time for your health, life challenges such as COVID-19 can be managed.

- Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. National Institutes of Health. https://covid19.nih.gov/covid-19-topics/mental-health. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Mental Health and COVID-19: Early evidence of the pandemic's impact: Scientific brief, 2 March 2022. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mental_health-2022.1. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Mental health and the pandemic: What U.S. surveys have found. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/03/02/mental-health-and-the-pandemic-what-u-s-surveys-have-found/. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Taking care of your emotional health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://emergency.cdc.gov/coping/selfcare.asp. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- #HealthyAtHome—Mental health. World Health Organization. www.who.int/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/healthyathome/healthyathome---mental-health. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Coping with stress. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/stress-coping/cope-with-stress/. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Manage stress. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/myhealthfinder/topics/health-conditions/heart-health/manage-stress. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- COVID-19 and substance abuse. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/covid-19-substance-use#health-outcomes. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- COVID-19 resource and information guide. National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/Support-Education/NAMI-HelpLine/COVID-19-Information-and-Resources/COVID-19-Resource-and-Information-Guide. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Negative coping and PTSD. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/gethelp/negative_coping.asp. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Health effects of cigarette smoking. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/index.htm#respiratory. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- People with certain medical conditions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Your healthiest self: Emotional wellness toolkit. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/health-information/emotional-wellness-toolkit. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- World leprosy day: Bust the myths, learn the facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/leprosy/world-leprosy-day/. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- HIV stigma and discrimination. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/hiv-stigma/. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Diabetes stigma: Learn about it, recognize it, reduce it. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/features/diabetes_stigma.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Phelan SM, et al. Patient and health care professional perspectives on stigma in integrated behavioral health: Barriers and recommendations. Annals of Family Medicine. 2023; doi:10.1370/afm.2924.

- Stigma reduction. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/od2a/case-studies/stigma-reduction.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Nyblade L, et al. Stigma in health facilities: Why it matters and how we can change it. BMC Medicine. 2019; doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1256-2.

- Combating bias and stigma related to COVID-19. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19-bias. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Yashadhana A, et al. Pandemic-related racial discrimination and its health impact among non-Indigenous racially minoritized peoples in high-income contexts: A systematic review. Health Promotion International. 2021; doi:10.1093/heapro/daab144.

- Sawchuk CN (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. March 25, 2024.

Products and Services

- A Book: Endemic - A Post-Pandemic Playbook

- Begin Exploring Women's Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- A Book: Future Care

- Antibiotics: Are you misusing them?

- COVID-19 and vitamin D

- Convalescent plasma therapy

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

- COVID-19: How can I protect myself?

- Herd immunity and respiratory illness

- COVID-19 and pets

- COVID-19 antibody testing

- COVID-19, cold, allergies and the flu

- Long-term effects of COVID-19

- COVID-19 tests

- COVID-19 drugs: Are there any that work?

- COVID-19 in babies and children

- Coronavirus infection by race

- COVID-19 travel advice

- COVID-19 vaccine: Should I reschedule my mammogram?

- COVID-19 vaccines for kids: What you need to know

- COVID-19 vaccines

- COVID-19 variant

- COVID-19 vs. flu: Similarities and differences

- COVID-19: Who's at higher risk of serious symptoms?

- Debunking coronavirus myths

- Different COVID-19 vaccines

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)

- Fever: First aid

- Fever treatment: Quick guide to treating a fever

- Fight coronavirus (COVID-19) transmission at home

- Honey: An effective cough remedy?

- How do COVID-19 antibody tests differ from diagnostic tests?

- How to measure your respiratory rate

- How to take your pulse

- How to take your temperature

- How well do face masks protect against COVID-19?

- Is hydroxychloroquine a treatment for COVID-19?

- Loss of smell

- Mayo Clinic Minute: You're washing your hands all wrong

- Mayo Clinic Minute: How dirty are common surfaces?

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Pregnancy and COVID-19

- Safe outdoor activities during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Safety tips for attending school during COVID-19

- Sex and COVID-19

- Shortness of breath

- Thermometers: Understand the options

- Treating COVID-19 at home

- Unusual symptoms of coronavirus

- Vaccine guidance from Mayo Clinic

- Watery eyes

Related information

- Mental health: What's normal, what's not - Related information Mental health: What's normal, what's not

- Mental illness - Related information Mental illness

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

by Alissa Wilkinson

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

- The Vox guide to navigating the coronavirus crisis

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

- A syllabus for the end of the world

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

- What day is it today?

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

- Vox is starting a book club. Come read with us!

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Most Popular

The caribbean has a defense system against deadly hurricanes — but it’s vanishing, the supreme court’s disastrous trump immunity decision, explained, the supreme court also handed down a hugely important first amendment case today, do other democrats actually poll better against trump than biden, 5 terrible reasons for biden to stay in the race, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Culture

Chappell Roan spent 7 years becoming an overnight success

The Spotify conspiracy theories about "Espresso," explained

Tiktok is full of bad health “tricks”

How the UFC explains the USA

Kevin Costner’s ego and the strange road to Horizon

Hawk Tuah Girl, explained by straight dudes

What about Kamala?

Food is no longer a main character on The Bear

Should Biden drop out? The debate, explained.

How white victimhood is shaping a second Trump term

If it’s 100 degrees out, does your boss have to give you a break? Probably not.

I Thought We’d Learned Nothing From the Pandemic. I Wasn’t Seeing the Full Picture

M y first home had a back door that opened to a concrete patio with a giant crack down the middle. When my sister and I played, I made sure to stay on the same side of the divide as her, just in case. The 1988 film The Land Before Time was one of the first movies I ever saw, and the image of the earth splintering into pieces planted its roots in my brain. I believed that, even in my own backyard, I could easily become the tiny Triceratops separated from her family, on the other side of the chasm, as everything crumbled into chaos.

Some 30 years later, I marvel at the eerie, unexpected ways that cartoonish nightmare came to life – not just for me and my family, but for all of us. The landscape was already covered in fissures well before COVID-19 made its way across the planet, but the pandemic applied pressure, and the cracks broke wide open, separating us from each other physically and ideologically. Under the weight of the crisis, we scattered and landed on such different patches of earth we could barely see each other’s faces, even when we squinted. We disagreed viciously with each other, about how to respond, but also about what was true.

Recently, someone asked me if we’ve learned anything from the pandemic, and my first thought was a flat no. Nothing. There was a time when I thought it would be the very thing to draw us together and catapult us – as a capital “S” Society – into a kinder future. It’s surreal to remember those early days when people rallied together, sewing masks for health care workers during critical shortages and gathering on balconies in cities from Dallas to New York City to clap and sing songs like “Yellow Submarine.” It felt like a giant lightning bolt shot across the sky, and for one breath, we all saw something that had been hidden in the dark – the inherent vulnerability in being human or maybe our inescapable connectedness .

More from TIME

Read More: The Family Time the Pandemic Stole

But it turns out, it was just a flash. The goodwill vanished as quickly as it appeared. A couple of years later, people feel lied to, abandoned, and all on their own. I’ve felt my own curiosity shrinking, my willingness to reach out waning , my ability to keep my hands open dwindling. I look out across the landscape and see selfishness and rage, burnt earth and so many dead bodies. Game over. We lost. And if we’ve already lost, why try?

Still, the question kept nagging me. I wondered, am I seeing the full picture? What happens when we focus not on the collective society but at one face, one story at a time? I’m not asking for a bow to minimize the suffering – a pretty flourish to put on top and make the whole thing “worth it.” Yuck. That’s not what we need. But I wondered about deep, quiet growth. The kind we feel in our bodies, relationships, homes, places of work, neighborhoods.

Like a walkie-talkie message sent to my allies on the ground, I posted a call on my Instagram. What do you see? What do you hear? What feels possible? Is there life out here? Sprouting up among the rubble? I heard human voices calling back – reports of life, personal and specific. I heard one story at a time – stories of grief and distrust, fury and disappointment. Also gratitude. Discovery. Determination.

Among the most prevalent were the stories of self-revelation. Almost as if machines were given the chance to live as humans, people described blossoming into fuller selves. They listened to their bodies’ cues, recognized their desires and comforts, tuned into their gut instincts, and honored the intuition they hadn’t realized belonged to them. Alex, a writer and fellow disabled parent, found the freedom to explore a fuller version of herself in the privacy the pandemic provided. “The way I dress, the way I love, and the way I carry myself have both shrunk and expanded,” she shared. “I don’t love myself very well with an audience.” Without the daily ritual of trying to pass as “normal” in public, Tamar, a queer mom in the Netherlands, realized she’s autistic. “I think the pandemic helped me to recognize the mask,” she wrote. “Not that unmasking is easy now. But at least I know it’s there.” In a time of widespread suffering that none of us could solve on our own, many tended to our internal wounds and misalignments, large and small, and found clarity.

Read More: A Tool for Staying Grounded in This Era of Constant Uncertainty

I wonder if this flourishing of self-awareness is at least partially responsible for the life alterations people pursued. The pandemic broke open our personal notions of work and pushed us to reevaluate things like time and money. Lucy, a disabled writer in the U.K., made the hard decision to leave her job as a journalist covering Westminster to write freelance about her beloved disability community. “This work feels important in a way nothing else has ever felt,” she wrote. “I don’t think I’d have realized this was what I should be doing without the pandemic.” And she wasn’t alone – many people changed jobs , moved, learned new skills and hobbies, became politically engaged.

Perhaps more than any other shifts, people described a significant reassessment of their relationships. They set boundaries, said no, had challenging conversations. They also reconnected, fell in love, and learned to trust. Jeanne, a quilter in Indiana, got to know relatives she wouldn’t have connected with if lockdowns hadn’t prompted weekly family Zooms. “We are all over the map as regards to our belief systems,” she emphasized, “but it is possible to love people you don’t see eye to eye with on every issue.” Anna, an anti-violence advocate in Maine, learned she could trust her new marriage: “Life was not a honeymoon. But we still chose to turn to each other with kindness and curiosity.” So many bonds forged and broken, strengthened and strained.

Instead of relying on default relationships or institutional structures, widespread recalibrations allowed for going off script and fortifying smaller communities. Mara from Idyllwild, Calif., described the tangible plan for care enacted in her town. “We started a mutual-aid group at the beginning of the pandemic,” she wrote, “and it grew so quickly before we knew it we were feeding 400 of the 4000 residents.” She didn’t pretend the conditions were ideal. In fact, she expressed immense frustration with our collective response to the pandemic. Even so, the local group rallied and continues to offer assistance to their community with help from donations and volunteers (many of whom were originally on the receiving end of support). “I’ve learned that people thrive when they feel their connection to others,” she wrote. Clare, a teacher from the U.K., voiced similar conviction as she described a giant scarf she’s woven out of ribbons, each representing a single person. The scarf is “a collection of stories, moments and wisdom we are sharing with each other,” she wrote. It now stretches well over 1,000 feet.

A few hours into reading the comments, I lay back on my bed, phone held against my chest. The room was quiet, but my internal world was lighting up with firefly flickers. What felt different? Surely part of it was receiving personal accounts of deep-rooted growth. And also, there was something to the mere act of asking and listening. Maybe it connected me to humans before battle cries. Maybe it was the chance to be in conversation with others who were also trying to understand – what is happening to us? Underneath it all, an undeniable thread remained; I saw people peering into the mess and narrating their findings onto the shared frequency. Every comment was like a flare into the sky. I’m here! And if the sky is full of flares, we aren’t alone.

I recognized my own pandemic discoveries – some minor, others massive. Like washing off thick eyeliner and mascara every night is more effort than it’s worth; I can transform the mundane into the magical with a bedsheet, a movie projector, and twinkle lights; my paralyzed body can mother an infant in ways I’d never seen modeled for me. I remembered disappointing, bewildering conversations within my own family of origin and our imperfect attempts to remain close while also seeing things so differently. I realized that every time I get the weekly invite to my virtual “Find the Mumsies” call, with a tiny group of moms living hundreds of miles apart, I’m being welcomed into a pocket of unexpected community. Even though we’ve never been in one room all together, I’ve felt an uncommon kind of solace in their now-familiar faces.

Hope is a slippery thing. I desperately want to hold onto it, but everywhere I look there are real, weighty reasons to despair. The pandemic marks a stretch on the timeline that tangles with a teetering democracy, a deteriorating planet , the loss of human rights that once felt unshakable . When the world is falling apart Land Before Time style, it can feel trite, sniffing out the beauty – useless, firing off flares to anyone looking for signs of life. But, while I’m under no delusions that if we just keep trudging forward we’ll find our own oasis of waterfalls and grassy meadows glistening in the sunshine beneath a heavenly chorus, I wonder if trivializing small acts of beauty, connection, and hope actually cuts us off from resources essential to our survival. The group of abandoned dinosaurs were keeping each other alive and making each other laugh well before they made it to their fantasy ending.

Read More: How Ice Cream Became My Own Personal Act of Resistance

After the monarch butterfly went on the endangered-species list, my friend and fellow writer Hannah Soyer sent me wildflower seeds to plant in my yard. A simple act of big hope – that I will actually plant them, that they will grow, that a monarch butterfly will receive nourishment from whatever blossoms are able to push their way through the dirt. There are so many ways that could fail. But maybe the outcome wasn’t exactly the point. Maybe hope is the dogged insistence – the stubborn defiance – to continue cultivating moments of beauty regardless. There is value in the planting apart from the harvest.

I can’t point out a single collective lesson from the pandemic. It’s hard to see any great “we.” Still, I see the faces in my moms’ group, making pancakes for their kids and popping on between strings of meetings while we try to figure out how to raise these small people in this chaotic world. I think of my friends on Instagram tending to the selves they discovered when no one was watching and the scarf of ribbons stretching the length of more than three football fields. I remember my family of three, holding hands on the way up the ramp to the library. These bits of growth and rings of support might not be loud or right on the surface, but that’s not the same thing as nothing. If we only cared about the bottom-line defeats or sweeping successes of the big picture, we’d never plant flowers at all.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Melinda French Gates Is Going It Alone

- What to Do if You Can’t Afford Your Medications

- How to Buy Groceries Without Breaking the Bank

- Sienna Miller Is the Reason to Watch Horizon

- Why So Many Bitcoin Mining Companies Are Pivoting to AI

- The 15 Best Movies to Watch on a Plane

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

What Life Was Like for Students in the Pandemic Year

- Share article

In this video, Navajo student Miles Johnson shares how he experienced the stress and anxiety of schools shutting down last year. Miles’ teacher shared his experience and those of her other students in a recent piece for Education Week. In these short essays below, teacher Claire Marie Grogan’s 11th grade students at Oceanside High School on Long Island, N.Y., describe their pandemic experiences. Their writings have been slightly edited for clarity. Read Grogan’s essay .

“Hours Staring at Tiny Boxes on the Screen”

By Kimberly Polacco, 16

I stare at my blank computer screen, trying to find the motivation to turn it on, but my finger flinches every time it hovers near the button. I instead open my curtains. It is raining outside, but it does not matter, I will not be going out there for the rest of the day. The sound of pounding raindrops contributes to my headache enough to make me turn on my computer in hopes that it will give me something to drown out the noise. But as soon as I open it up, I feel the weight of the world crash upon my shoulders.

Each 42-minute period drags on by. I spend hours upon hours staring at tiny boxes on a screen, one of which my exhausted face occupies, and attempt to retain concepts that have been presented to me through this device. By the time I have the freedom of pressing the “leave” button on my last Google Meet of the day, my eyes are heavy and my legs feel like mush from having not left my bed since I woke up.

Tomorrow arrives, except this time here I am inside of a school building, interacting with my first period teacher face to face. We talk about our favorite movies and TV shows to stream as other kids pile into the classroom. With each passing period I accumulate more and more of these tiny meaningless conversations everywhere I go with both teachers and students. They may not seem like much, but to me they are everything because I know that the next time I am expected to report to school, I will be trapped in the bubble of my room counting down the hours until I can sit down in my freshly sanitized wooden desk again.

“My Only Parent Essentially on Her Death Bed”

By Nick Ingargiola, 16

My mom had COVID-19 for ten weeks. She got sick during the first month school buildings were shut. The difficulty of navigating an online classroom was already overwhelming, and when mixed with my only parent essentially on her death bed, it made it unbearable. Focusing on schoolwork was impossible, and watching my mother struggle to lift up her arm broke my heart.