Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Published on October 18, 2021 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on May 9, 2024.

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from people.

The goals of human research often include understanding real-life phenomena, studying effective treatments, investigating behaviors, and improving lives in other ways. What you decide to research and how you conduct that research involve key ethical considerations.

These considerations work to

- protect the rights of research participants

- enhance research validity

- maintain scientific or academic integrity

Table of contents

Why do research ethics matter, getting ethical approval for your study, types of ethical issues, voluntary participation, informed consent, confidentiality, potential for harm, results communication, examples of ethical failures, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research ethics.

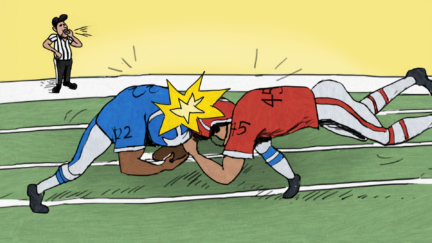

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe for research subjects.

You’ll balance pursuing important research objectives with using ethical research methods and procedures. It’s always necessary to prevent permanent or excessive harm to participants, whether inadvertent or not.

Defying research ethics will also lower the credibility of your research because it’s hard for others to trust your data if your methods are morally questionable.

Even if a research idea is valuable to society, it doesn’t justify violating the human rights or dignity of your study participants.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Before you start any study involving data collection with people, you’ll submit your research proposal to an institutional review board (IRB) .

An IRB is a committee that checks whether your research aims and research design are ethically acceptable and follow your institution’s code of conduct. They check that your research materials and procedures are up to code.

If successful, you’ll receive IRB approval, and you can begin collecting data according to the approved procedures. If you want to make any changes to your procedures or materials, you’ll need to submit a modification application to the IRB for approval.

If unsuccessful, you may be asked to re-submit with modifications or your research proposal may receive a rejection. To get IRB approval, it’s important to explicitly note how you’ll tackle each of the ethical issues that may arise in your study.

There are several ethical issues you should always pay attention to in your research design, and these issues can overlap with each other.

You’ll usually outline ways you’ll deal with each issue in your research proposal if you plan to collect data from participants.

| Voluntary participation | Your participants are free to opt in or out of the study at any point in time. |

|---|---|

| Informed consent | Participants know the purpose, benefits, risks, and funding behind the study before they agree or decline to join. |

| Anonymity | You don’t know the identities of the participants. Personally identifiable data is not collected. |

| Confidentiality | You know who the participants are but you keep that information hidden from everyone else. You anonymize personally identifiable data so that it can’t be linked to other data by anyone else. |

| Potential for harm | Physical, social, psychological and all other types of harm are kept to an absolute minimum. |

| Results communication | You ensure your work is free of or research misconduct, and you accurately represent your results. |

Voluntary participation means that all research subjects are free to choose to participate without any pressure or coercion.

All participants are able to withdraw from, or leave, the study at any point without feeling an obligation to continue. Your participants don’t need to provide a reason for leaving the study.

It’s important to make it clear to participants that there are no negative consequences or repercussions to their refusal to participate. After all, they’re taking the time to help you in the research process , so you should respect their decisions without trying to change their minds.

Voluntary participation is an ethical principle protected by international law and many scientific codes of conduct.

Take special care to ensure there’s no pressure on participants when you’re working with vulnerable groups of people who may find it hard to stop the study even when they want to.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Informed consent refers to a situation in which all potential participants receive and understand all the information they need to decide whether they want to participate. This includes information about the study’s benefits, risks, funding, and institutional approval.

You make sure to provide all potential participants with all the relevant information about

- what the study is about

- the risks and benefits of taking part

- how long the study will take

- your supervisor’s contact information and the institution’s approval number

Usually, you’ll provide participants with a text for them to read and ask them if they have any questions. If they agree to participate, they can sign or initial the consent form. Note that this may not be sufficient for informed consent when you work with particularly vulnerable groups of people.

If you’re collecting data from people with low literacy, make sure to verbally explain the consent form to them before they agree to participate.

For participants with very limited English proficiency, you should always translate the study materials or work with an interpreter so they have all the information in their first language.

In research with children, you’ll often need informed permission for their participation from their parents or guardians. Although children cannot give informed consent, it’s best to also ask for their assent (agreement) to participate, depending on their age and maturity level.

Anonymity means that you don’t know who the participants are and you can’t link any individual participant to their data.

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information—for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, and videos.

In many cases, it may be impossible to truly anonymize data collection . For example, data collected in person or by phone cannot be considered fully anonymous because some personal identifiers (demographic information or phone numbers) are impossible to hide.

You’ll also need to collect some identifying information if you give your participants the option to withdraw their data at a later stage.

Data pseudonymization is an alternative method where you replace identifying information about participants with pseudonymous, or fake, identifiers. The data can still be linked to participants but it’s harder to do so because you separate personal information from the study data.

Confidentiality means that you know who the participants are, but you remove all identifying information from your report.

All participants have a right to privacy, so you should protect their personal data for as long as you store or use it. Even when you can’t collect data anonymously, you should secure confidentiality whenever you can.

Some research designs aren’t conducive to confidentiality, but it’s important to make all attempts and inform participants of the risks involved.

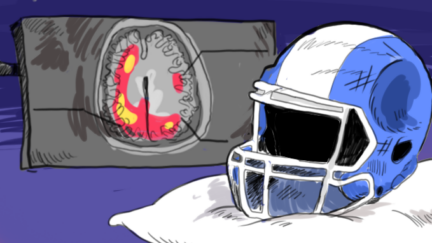

As a researcher, you have to consider all possible sources of harm to participants. Harm can come in many different forms.

- Psychological harm: Sensitive questions or tasks may trigger negative emotions such as shame or anxiety.

- Social harm: Participation can involve social risks, public embarrassment, or stigma.

- Physical harm: Pain or injury can result from the study procedures.

- Legal harm: Reporting sensitive data could lead to legal risks or a breach of privacy.

It’s best to consider every possible source of harm in your study as well as concrete ways to mitigate them. Involve your supervisor to discuss steps for harm reduction.

Make sure to disclose all possible risks of harm to participants before the study to get informed consent. If there is a risk of harm, prepare to provide participants with resources or counseling or medical services if needed.

Some of these questions may bring up negative emotions, so you inform participants about the sensitive nature of the survey and assure them that their responses will be confidential.

The way you communicate your research results can sometimes involve ethical issues. Good science communication is honest, reliable, and credible. It’s best to make your results as transparent as possible.

Take steps to actively avoid plagiarism and research misconduct wherever possible.

Plagiarism means submitting others’ works as your own. Although it can be unintentional, copying someone else’s work without proper credit amounts to stealing. It’s an ethical problem in research communication because you may benefit by harming other researchers.

Self-plagiarism is when you republish or re-submit parts of your own papers or reports without properly citing your original work.

This is problematic because you may benefit from presenting your ideas as new and original even though they’ve already been published elsewhere in the past. You may also be infringing on your previous publisher’s copyright, violating an ethical code, or wasting time and resources by doing so.

In extreme cases of self-plagiarism, entire datasets or papers are sometimes duplicated. These are major ethical violations because they can skew research findings if taken as original data.

You notice that two published studies have similar characteristics even though they are from different years. Their sample sizes, locations, treatments, and results are highly similar, and the studies share one author in common.

Research misconduct

Research misconduct means making up or falsifying data, manipulating data analyses, or misrepresenting results in research reports. It’s a form of academic fraud.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement about data analyses.

Research misconduct is a serious ethical issue because it can undermine academic integrity and institutional credibility. It leads to a waste of funding and resources that could have been used for alternative research.

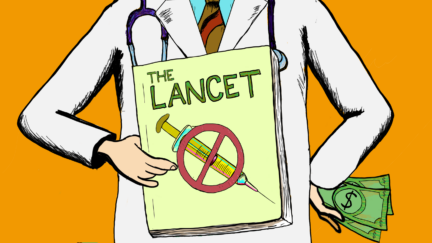

Later investigations revealed that they fabricated and manipulated their data to show a nonexistent link between vaccines and autism. Wakefield also neglected to disclose important conflicts of interest, and his medical license was taken away.

This fraudulent work sparked vaccine hesitancy among parents and caregivers. The rate of MMR vaccinations in children fell sharply, and measles outbreaks became more common due to a lack of herd immunity.

Research scandals with ethical failures are littered throughout history, but some took place not that long ago.

Some scientists in positions of power have historically mistreated or even abused research participants to investigate research problems at any cost. These participants were prisoners, under their care, or otherwise trusted them to treat them with dignity.

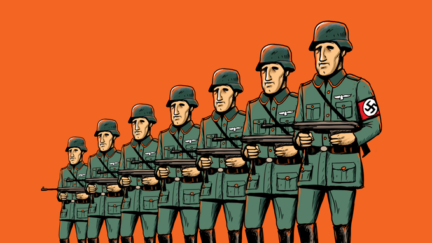

To demonstrate the importance of research ethics, we’ll briefly review two research studies that violated human rights in modern history.

These experiments were inhumane and resulted in trauma, permanent disabilities, or death in many cases.

After some Nazi doctors were put on trial for their crimes, the Nuremberg Code of research ethics for human experimentation was developed in 1947 to establish a new standard for human experimentation in medical research.

In reality, the actual goal was to study the effects of the disease when left untreated, and the researchers never informed participants about their diagnoses or the research aims.

Although participants experienced severe health problems, including blindness and other complications, the researchers only pretended to provide medical care.

When treatment became possible in 1943, 11 years after the study began, none of the participants were offered it, despite their health conditions and high risk of death.

Ethical failures like these resulted in severe harm to participants, wasted resources, and lower trust in science and scientists. This is why all research institutions have strict ethical guidelines for performing research.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Cohort study

- Peer review

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. These principles include voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, potential for harm, and results communication.

Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from others .

These considerations protect the rights of research participants, enhance research validity , and maintain scientific integrity.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe.

Anonymity means you don’t know who the participants are, while confidentiality means you know who they are but remove identifying information from your research report. Both are important ethical considerations .

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information—for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, or videos.

You can keep data confidential by using aggregate information in your research report, so that you only refer to groups of participants rather than individuals.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement but a serious ethical failure.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2024, May 09). Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 8, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/research-ethics/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, data collection | definition, methods & examples, what is self-plagiarism | definition & how to avoid it, how to avoid plagiarism | tips on citing sources, what is your plagiarism score.

5 Common Ethical Dilemmas in User Research

April 23, 2023 2023-04-23

- Email article

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Twitter

Just because user research is applied research, doesn’t mean research ethics isn’t important or necessary! This article covers 5 common ethical dilemmas that can crop up in user-research studies and the best practices around them.

In This Article:

Balancing honest disclosure with study goals, concealment, sensitive research topics causing distress to participants, studying vulnerable groups who cannot consent to participation, participants revealing sensitive personal information, compromising confidentiality due to small participant pool.

In ethical research with human participants, informed consent is crucial as it underpins the principle of respect for persons : the right for everyone to have autonomy over their own decisions. Informed consent means that participants are told about all aspects of the study so they can make an informed decision on whether to take part. We collect evidence of informed consent through a consent form .

However, in some studies, disclosing in advance the goals of the study or the organization conducting the study could jeopardize the validity of the research, as participants may not act naturally or might inadvertently change their behavior. Concealment and deception are tactics to mitigate this effect. Both present ethical challenges.

Concealment refers to the situation where some important information about the study (which would usually be in the consent form) is withheld from research participants during the consent-gathering process.

Concealment is common in health research. To know whether a new drug can effectively treat a disease, clinical researchers recruit people with the disease and randomly assign them to one of two groups: those who try the new drug and those who don’t. After the study is over, the researchers compare the outcomes of the two groups to learn whether the drug is effective and safe. In studies like these, participants are unaware of which group they have been assigned to, but they know they’ll be randomly assigned to one of the two groups. The group that doesn’t receive the new drug receives an identical sugar pill (a placebo). Concealment is used to control for the powerful psychological effects (known as placebo and nocebo effects) that participants can experience when they think they are receiving treatment.

Deception occurs when research participants are misled about the purpose of the research or about the organization sponsoring the research study during the consent-gathering process.

Deception is often used to avoid revealing the true motive of the study or who conducts the study. For example, perhaps a company wants to do competitive testing on its own product and of a competitor product. When recruiting participants and conducting the study, researchers may tell participants that they work for an independent company to prevent biasing participants towards the company’s design. (In this situation, you can replace deception with concealment by hiring an independent UX-research company to do competitive testing for you; for the study to be sound, however, this company will need to conceal who is funding the research to avoid influencing participants’ behavior.)

Although both concealment and deception can be ethically tricky, deception is more problematic , since false information was provided to participants during consent gathering. Studies that utilize deception or concealment require a debrief, where the researcher provides the correct information after the session or study has concluded. During the debrief, researchers give the participant the option to withdraw (i.e., remove their data from the study) after learning the correct information.

UX studies rarely need to use concealment or deception . They should be reserved only for situations where the study could not be performed without one of these tactics and participants won’t be harmed by them. If you use deception or concealment in your study, provide participants with the correct information after the session is over and respect their wish to withdraw from the study.

Sometimes we develop products and services to support people who might experience hard life situations, including:

- A life-altering medical condition

- Loss of a loved one

- Domestic or sexual abuse

- A serious addiction

Speaking to people about these experiences can be upsetting and can cause participants to relive trauma. However, not researching with target users can result in products and services that are poorly designed, don’t meet people’s needs, and, worse, could cause harm.

One principle of research ethics is to do no harm . To avoid harming participants, research sessions should be appropriately designed to ensure that:

- Participants are aware of the nature of the topic.

- Researchers broach sensitive topics without causing harm.

- Researchers are prepared for how to react should participants become upset.

If your study involves a sensitive topic, you should consider:

- Seeking guidance from a subject-matter expert (such as a counselor or an employee of a related charity) on how to broach the topic

- Ensuring that you clearly inform participants of what will and won’t be discussed in the recruitment material, in the consent form, and at the beginning of the session

- Giving participants the option to withdraw or not answer certain questions if they feel uncomfortable

- Preparing leaflets with contact information for free resources, counselors, or support services in the participant’s local community

Some participants are vulnerable because they can be coerced into participating in studies or could be harmed by participating in research. Extra safeguards need to be put in place to ensure that informed consent is possible, and any risks are minimized. Examples of vulnerable participants include:

- People who can’t consent (e.g., children, people with dementia, people with an intellectual disability, people with low literacy)

- People who might experience discrimination or reputational damage if they were to be identified in research

When participants can’t give informed consent, a legal representative or authorized adult should be asked to provide informed consent in addition to the participant’s agreement (assent) to participate.

If you are recruiting vulnerable participants, conduct a simple risk assessment to identify risks and create a plan to mitigate them and seek support from a subject-matter expert.

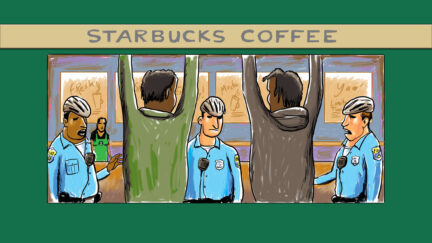

Sometimes in user-research studies participants accidentally reveal sensitive personal information (like names, bank accounts, or credit-card information) and this information is captured in session recordings. Several years ago, during an in-person research session in the Middle East, a participant revealed he was homosexual, which was illegal in his country. Thankfully, only a colleague and I were in the session. We immediately stopped the recording and deleted it, realizing that the participant could be harmed if this information got into the wrong hands.

As UX researchers, our first duty is of care towards our participants: even though we might feel that the session is extremely valuable for our study goals, when information like this is captured on recordings or in our data-collection process, we must ensure that it is swiftly and securely removed, even though we might feel that it compromises the study goals or our ability to persuade stakeholders.

Research is said to be confidential when researchers take steps to ensure that other people inside and outside of their organization are not able to identify participants in the reporting of the research.

While in most user-research studies we can remove references to participants’ personal information (such as their names) to achieve confidentiality, sometimes participants will be identified regardless. For example, if you are performing user research with internal employees from a small team and or if, perhaps, stakeholders helped you to recruit participants for a study, even “anonymous” quotes could be attributed to a person due to the context. In these situations, let participants know that they could be identified before the research occurs. Don’t promise confidentiality if you can’t assure it. Participants should be allowed to withdraw from the study at any point. Consider not inviting stakeholders to the research session and doublechecking with the participant before you begin the recording that they are comfortable with the conditions of the research.

User research, like any other research with humans, can present many ethical dilemmas and challenges. We must design our research studies so that we safeguard our participants’ best interests and do no harm.

Related Courses

Analytics and user experience.

Study your users’ real-life behaviors and make data-informed design decisions

Measuring UX and ROI

Use metrics from quantitative research to demonstrate value

Personas: Turn User Data Into User-Centered Design

Create, maintain, and utilize personas throughout the UX design process

Related Topics

- Research Methods Research Methods

Learn More:

MVP: Why It Isn't Always Release 1

Sara Paul · 4 min

What Is a SWOT Analysis?

Therese Fessenden · 5 min

What Is User Research?

Caleb Sponheim · 3 min

Related Articles:

Ethical Maturity in User Research

Maria Rosala · 7 min

The Vortex: Why Users Feel Trapped in Their Devices

Kate Moran and Kim Flaherty · 12 min

Card Sorting: Pushing Users Beyond Terminology Matches

Samhita Tankala and Jakob Nielsen · 5 min

6 Tips for Better Participant Engagement in Diary Studies

Maria Rosala · 6 min

Obtaining Consent for User Research

Therese Fessenden · 8 min

Recruiting High-Income Participants: Challenges and Tips

Kate Moran · 4 min

Ethical Dilemmas in Scientific Research and Professional Integrity

Welcome to the Georgia CTSA webpage on ethical dilemmas in scientific research and professional integrity. This page presents case scenarios involving responsible conduct in research. Each case is followed by a brief, expert opinion that suggests strategies for resolution.*

View a sample case followed by an expert opinion

We especially hope that these cases can provide useful teaching materials for college or university faculty who present lectures or courses on responsible conduct in research. The cases and expert opinions on this page are intended for instructional use and are copyrighted by Emory University.

Readers interested in submitting a dilemma of their own for possible review, comment, and posting to the website can send their dilemma to Dr. John Banja . The dilemma must relate to research ethics. Submission of a dilemma does not guarantee a review for an expert opinion or posting to the website.

- Georgia CTSA & Winship Cancer Institute Offer Collaborative Research Ethics Consultation Service

- Emory Center for Ethics

- Georgia Tech Ethics, Technology, and Human Interaction Center (ETHICx)

- Morehouse School of Medicine Ethics and Compliance

Spotlight on Ethics

AI, Radiology, and Ethics: A Podcast Series

“ AI, Radiology and Ethics ” is a podcast series featuring internationally recognized thought leaders commenting on the application of artificial intelligence to the imaging sciences. This series is hosted by Dr. John Banja. Examples of featured podcast topics include:

- How Will Artificial Intelligence Affect the Medical Malpractice Experience in Radiology?

- Bias, Fairness, and Generalizability

- Bias: Confronting the Problem

We Wonder Podcast

- Medical Ethics and AI with John Banja

Ethical Dilemmas

Allocating credit.

- Who Gets the Credit? (PDF)

- But That Was My Idea! (PDF)

- Replacing a First Author on a Second Submission (PDF)

- The Tyrannical Principal Investigator (PDF)

- The Overly Nice Advisor (PDF)

- When the Authors Can't Write English (PDF)

- A Conscientious Objection (PDF)

- Unnecessary Animal Use (PDF)

- A Mess of Authors (PDF)

- Author, Author! (PDF)

- But I Don't Want To Be An Author (PDF)

- Deciding First Authorship (PDF)

- I Can't Say No (PDF)

- I Rub Your Back (PDF)

- On First Authorship (PDF)

- Read This, But Don't Tell Anybody (PDF)

- When the Author Can't Write English (PDF)

Confidentiality

- Breach of Confidentiality (PDF)

- Breach of Confidentiality: A Tissue Donor Identified (PDF)

Conflict of Interest

- Uncertainties and Conflicting Interest in Lung Transplantation (PDF)

- When the LAR is also the Investigator (PDF)

- When an Investigator Recruits Himself for a Study (PDF)

Data Interpretation and Management

- Data Torturing (PDF)

- Praying Over the Experiment (PDF)

- Let's Not Mention That in the Report (PDF)

- Which Assay to Believe? (PDF)

- He Took His Notebook (PDF)

- Image Manipulation (PDF)

- Patience is a Virtue (PDF)

- An Instance of Data Manipulation (PDF)

Data Representation

- Deleting Data Points (PDF)

- Mum's the Word (PDF)

Drug Trials

- Ethical Conduction of an International Pediatric Trial (PDF)

- Expediting Approval (PDF)

Genetics Research

- Should Incidental Findings be Returned? (PDF)

Healthcare Inequities

- Concierge Medicine: Ethically Concerning or a Better Care Model? (PDF)

Informed Consent

- First Poke, Then Hope (PDF)

- The Right to Participate in Research (PDF)

- Making it Harder to Say No (PDF)

- Can a Patient Edit their Consent Form before Signing? (PDF)

Intellectual Property

- The Nutty Professor (PDF)

- Would You Do a Post-Doc with this Guy? (PDF)

- Research Misconduct at the High School Level (PDF)

- Who Gets the Credit?

- An Instance of Fraud (PDF)

- Patience is a Virtue

- When the TA Suspects Cheating (PDF)

- A Letter of "Non-Recommendation" (PDF)

- Does the Punishment Fit the Crime? (PDF)

- Handling a Case of Cheating (PDF)

- Playing By the Rules: Multiple Abstract Submissions (PDF)

- We're Not Recruiting Enough Participants! (PDF)

- Sabotage (PDF)

Participant Recruitment

- Should We Interview Bereaved Parents? (PDF)

- When the Legally Authorized Representative is also the Investigator (PDF)

- Should Uninsured Patients be Offered Clinical Trials? (PDF)

- Enrolling One's Own Children in Your Research (PDF)

Protocol Deviation

- Two Protocol Deviations (PDF)

Reproducibility

- Ethics Podcasts in Research

*The cases and expert opinions on this website are intended for instructional use and are copyrighted by Emory University. THEY MAY BE REPRODUCED AND FURTHER DISTRIBUTED FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES, SO LONG AS THE FOLLOWING CONDITIONS ARE FULFILLED: (1) APPROPRIATE ATTRIBUTION IS INCLUDED; (2) THE MATERIALS ARE NOT MODIFIED; (3) THE MATERIALS ARE USED ONLY FOR ACADEMIC AND EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES; AND (4) NO FEE OR OTHER CHARGE IS IMPOSED TO OBTAIN ACCESS TO THE MATERIALS. ALL OTHER RIGHTS, INCLUDING THE RIGHT TO USE THE MATERIALS FOR COMMERCIAL PURPOSES, IS EXPRESSLY RESERVED BY EMORY UNIVERSITY. EMORY UNIVERSITY HOPES THAT THE MATERIALS ON THIS PAGE WILL BE HELPFUL, BUT PLEASE NOTE THAT THE MATERIALS ARE PROVIDED ON AN "AS IS" BASIS, AND ALL WARRANTIES ARE SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIMED.

- Open access

- Published: 29 September 2021

Defining ethical challenge(s) in healthcare research: a rapid review

- Guy Schofield ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9055-292X 1 , 3 ,

- Mariana Dittborn ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2903-6480 2 ,

- Lucy Ellen Selman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5747-2699 3 &

- Richard Huxtable ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5802-1870 1

BMC Medical Ethics volume 22 , Article number: 135 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

17 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

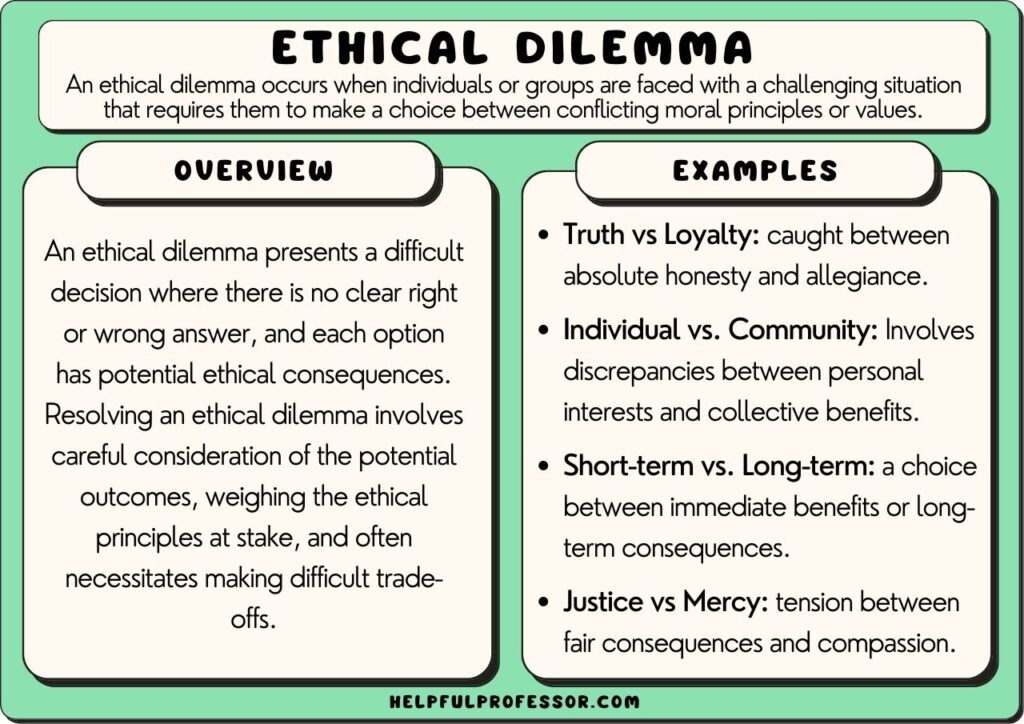

Despite its ubiquity in academic research, the phrase ‘ethical challenge(s)’ appears to lack an agreed definition. A lack of a definition risks introducing confusion or avoidable bias. Conceptual clarity is a key component of research, both theoretical and empirical. Using a rapid review methodology, we sought to review definitions of ‘ethical challenge(s)’ and closely related terms as used in current healthcare research literature.

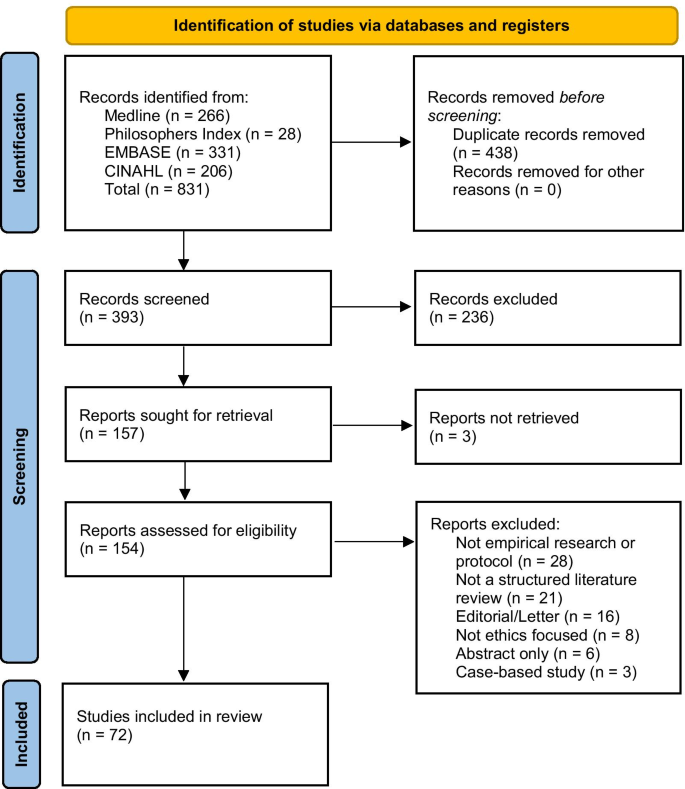

Rapid review to identify peer-reviewed reports examining ‘ethical challenge(s)’ in any context, extracting data on definitions of ‘ethical challenge(s)’ in use, and synonymous use of closely related terms in the general manuscript text. Data were analysed using content analysis. Four databases (MEDLINE, Philosopher’s Index, EMBASE, CINAHL) were searched from April 2016 to April 2021.

393 records were screened, with 72 studies eligible and included: 53 empirical studies, 17 structured reviews and 2 review protocols. 12/72 (17%) contained an explicit definition of ‘ethical challenge(s), two of which were shared, resulting in 11 unique definitions. Within these 11 definitions, four approaches were identified: definition through concepts; reference to moral conflict, moral uncertainty or difficult choices; definition by participants; and challenges linked to emotional or moral distress. Each definition contained one or more of these approaches, but none contained all four. 68/72 (94%) included studies used terms closely related to synonymously refer to ‘ethical challenge(s)’ within their manuscript text, with 32 different terms identified and between one and eight different terms mentioned per study.

Conclusions

Only 12/72 studies contained an explicit definition of ‘ethical challenge(s)’, with significant variety in scope and complexity. This variation risks confusion and biasing data analysis and results, reducing confidence in research findings. Further work on establishing acceptable definitional content is needed to inform future bioethics research.

Peer Review reports

Methodological rigour within research is a cornerstone in the production of high-quality findings and recommendations. Across the range of empirical methodologies, a broad collection of protocol development tools, methodology guidelines, and reporting guidelines have been developed and evidence of their use is increasingly required by journals [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Within both empirical bioethics and descriptive ethics, there has been an accompanying increase in the acknowledgment of the importance of methodological rigour in the empirical elements, including within the recent consensus statement on quality standards in empirical bioethics research by Ives et al. [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Aligned with this aim for rigour, definitional clarity of key terms used within a research project is a component of research quality [ 10 , 11 ]. Improving the quality of empirical bioethics is also itself an ethical imperative [ 9 ].

We recently conducted a systematic review examining ‘ethical challenges’ as reported by specialist palliative care practitioners [ 12 ]. Our review, alongside our initial scoping search findings and reading of the literature, suggested that, although many authors use the term ‘ethical challenge(s)’ in empirical ethics research, there appeared to be no commonly described or accepted definition. Furthermore, papers retrieved rarely defined ‘ethical challenge(s)’ explicitly , which has also been noted by other researchers examining other topic areas [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Our review further suggested that authors frequently use terms closely related to ‘ethical challenge(s)’—such as ‘moral dilemmas’ or ‘ethical issues’—interchangeably with ‘ethical challenge(s)’ throughout manuscripts, rather than staying with the original term. Research shows that non-philosophers may understand these related terms in heterogeneous ways which may additionally affect understanding of texts across different readerships [ 16 , 17 ].

Without a clear definition of an ethical challenge, each researcher must use individual judgement to ascertain whether they have identified an instance of one within their dataset. This potentially generates an unnecessary source of bias, particularly if multiple researchers are involved in data collection, extraction, or analysis. This risks generating misleading ethical analyses, evaluations, or recommendations. Additionally, and more broadly, if primary studies do not define the term, then work based on these—such as systematic reviews of individual studies or those undertaking secondary data analysis—may unknowingly compare different phenomena without a mechanism for mitigating the effects this introduces.

In the hope of prompting a debate on this topic, we therefore undertook a rapid review, which aimed to explore existing definitions of “ethical challenge(s)” and the use of other closely related terms within recent empirical healthcare ethics literature.

We conducted a rapid review examining the usage of the term ‘ethical challenge(s)’ over the last 5 years in published research articles, in order to identify and summarise if, and how, the term was defined. As a secondary aim, we examined authors’ uses of closely related alternative terms within the included article texts separate to their use within any explicit definitions that may be present.

Rapid reviews use abridged systematic review methodology to understand the evidence base on a particular topic in a time and resource efficient manner [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ]. Comparative reviews of topics in which both a rapid review and a systematic review had been undertaken demonstrated that the overall conclusions were similar, although rapid reviews were less likely to contain social and economic data, and systematic reviews contained more detailed recommendations [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 23 , 24 ]. The Cochrane Rapid Review Methods Group has recently released interim methodological guidelines for undertaking rapid reviews [ 6 ], advising authors to describe where their protocol deviates from a systematic review and detail any biases that these deviations may introduce [ 18 , 19 , 21 ]. We have followed the Cochrane recommended methodology [ 6 ]. A rapid review reporting guideline is currently under development [ 25 ] and this review is therefore reported based on the PRISMA 2020 statement for systematic reviews, with justifications provided where our approach deviated [ 26 ].

Prospective review protocol registration on the PROSPERO database is the current gold standard, but, at the time of writing, PROSPERO does not accept records for rapid reviews [ 27 ]. The protocol was therefore not published in advance.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarised in Table 1 . We used Strech et al.’s Methodology, Issues, Participants (MIP) structure for our eligibility criteria, which is recommended for systematic reviews in ‘empirical bioethics’ [ 28 ]. The criteria reflect three assumptions. First, that the inclusion of ‘ethical challenge(s)’ in the title would increase the likelihood that this was the authors’ preferred term for the concept under investigation, and therefore increase the probability of a definition being provided. Second, that studies aiming to describe empirical data and identify ethical challenges in real-world contexts are most likely to contain a definition to guide researchers in identifying these challenges as they collect and analyse data. Third, that structured reviews of studies of ethical challenges are likely to include a definition to allow researchers to reliably recognise an ethical challenge in retrieved records. We used a 5-year timeframe as a date restriction. This reflected a balance between adequately covering recent use of the term and time and resource restrictions of the rapid review.

Information sources

The search strategy was as follows:

‘ethical challenge’.ti OR ‘ethical challenges’.ti.

We searched Medline (Ovid interface), Philosopher’s Index (OVID interface), EMBASE (OVID interface), and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, EBSCO interface) for studies indexed over a five-year period between April 2016 and April 2021. These resources cover the breadth of healthcare research. Including Philosopher’s Index increased coverage of the bioethics literature. We did not search the grey literature [ 6 ]. The search strategy was tested by successfully retrieving three sentinel studies known to the research team.

Study selection

Retrieved studies were imported into Endnote X9.2 [ 29 ]. Records unavailable through institutional subscriptions were requested from corresponding authors. If unavailable 14 days after the request, the record was excluded. A random sample of 20% of records were dual screened at the title/abstract level by GS/MD. After discussion, the remainder were screened by GS. At full-text screening, a further 20% were dual screened by GS/MD and, again after discussion, the remaining studies were screened by GS.

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction was undertaken using a pre-piloted form, with the first 5 records dually extracted by GS and MD. Data from the remaining included studies was then extracted by GS, with correctness and completeness checked by MD. We collected data on date of publication, authors, journal, country (for primary studies), methodology, definition of ‘ethical challenge(s)’ (present (yes/no)) and (where offered) the definition provided, and any closely related terms used, with counts of all terms used in each article. For closely related terms, data was extracted from the authors’ text, but not from direct quotations from qualitative research. Where definitions of ‘ethical challenge(s)’ were offered and/or related terms were identified, these were categorised and counted following the principles of summative content analysis [ 30 ]. Summative content analysis combines both the quantitative counting of specific content or words/terms with latent content analysis to identify and categorise their meanings. We identified keywords (‘ethical challenge(s)’ and closely related terms) deployed by the authors of the included papers, both prior to and during data analysis, and analysed the retrieved definitions. This approach allowed for exploration of both the content of definitions and development of insights into the use of related terms.

Risk of bias assessment

The focus of the rapid review was the definition of the term ‘ethical challenge(s)’ within retrieved records. We therefore did not undertake quality assessment for the included studies and reviews.

831 records were retrieved, reduced to 393 after de-duplication. 238 records were excluded after reviewing the title and/or abstract. 157 records were identified for full text screening, with 3 unavailable [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. 82 records were excluded at full text stage and 72 records were included for analysis. See Fig. 1 for the PRISMA flowchart.

PRISMA flow diagram of record identification

Record characteristics

Of the 72 included records, 53 were empirical studies [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 ], 10 non-systematic reviews [ 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 ], 7 systematic reviews [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 ], 1 systematic review protocol [ 101 ], and 1 non-systematic review protocol [ 102 ]. Of the 53 empirical studies, 42 (79%) were qualitative studies [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 47 , 48 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 60 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 69 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 ], 6 (12%) used a mixed methods approach [ 45 , 46 , 53 , 59 , 61 , 68 ], and 5 (10%) were quantitative [ 37 , 49 , 70 , 78 , 82 ]. 7/56 empirical studies, all qualitative interview studies, recruited participants internationally with no specific location stated [ 40 , 54 , 55 , 58 , 60 , 63 , 73 ]. Of the remaining studies, all but one were single-country studies: Botswana [ 75 ], Canada [ 41 , 65 ], China [ 57 ], Denmark [ 39 , 43 ], Dominican Republic [ 44 ], Germany [ 51 , 84 ], India [ 61 ], Iran [ 38 , 46 , 49 , 68 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 78 , 82 , 98 ], Italy [ 45 ], Mexico [ 87 ], the Netherlands [ 76 ], New Zealand [ 47 ], Norway [ 42 , 52 , 56 , 64 , 80 , 81 , 83 ], Saudi Arabia [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ], Tanzania [ 69 , 74 ], Uganda [ 67 ], UK [ 86 ], and USA [ 50 , 53 , 59 , 62 , 66 , 77 , 79 , 85 , 85 ]. The remaining study was undertaken in both Sierra Leone and the UK [ 48 ]. See Table 2 for a summary.

12/72 (17%) of retrieved studies offered an explicit definition for ‘ethical challenge(s)’ [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 48 , 50 , 56 , 57 , 66 , 69 , 81 , 98 , 101 ]. Definitions were more likely to be found in more recent publications, with 4/12 included studies published in 2016–2018 [ 14 , 48 , 56 , 81 ], and 8/12 published in 2019–2021 [ 12 , 13 , 50 , 57 , 66 , 69 , 98 , 101 ]. The included study locations were evenly distributed, matching the overall pattern of retrieved studies, with studies from high- [ 48 , 50 , 56 , 66 , 81 ], middle- [ 57 , 98 ], and low-income settings [ 48 , 69 ]. The identified studies included eight qualitative studies [ 48 , 50 , 56 , 57 , 66 , 69 , 81 , 98 ], 3 systematic reviews [ 12 , 13 , 14 ], and 1 systematic review protocol [ 101 ]. Two of these records were the systematic review protocol and the report from our group, which accordingly contained the same definition [ 12 , 101 ], leaving 11 unique definitions. Definitions of ‘ethical challenge(s)’ identified in included studies are provided in Table 3 . Additionally, 68/72 (94%) reports used closely related terms synonymously in place of ‘ethical challenge(s)’ throughout their manuscript text, with between 1 and 8 different terms used within each report, and 32 different terms were identified. This occurred in both those reports that contained a definition and those that did not. See Table 4 for terms and frequencies.

Those records that offered explicit definitions used four approaches: (1) definition through concepts [ 12 , 57 , 66 ]; (2) reference to moral conflict, moral uncertainty or difficult choices [ 13 , 14 , 48 , 57 , 69 , 98 ]; (3) definition by study participants [ 12 , 48 , 50 , 56 ]; or (4) challenges as linked to their ability to generate emotional or moral distress within healthcare practitioners [ 14 , 14 , 66 , 81 ]. Each definition was associated with one or more of the identified elements, although none covered all four approaches. We describe these approaches below.

Approach 1: definition through concepts

This approach involves primarily defining ‘ethical challenge(s)’ in terms of related concepts. All three definitions using this approach defined ‘ethical challenge(s)’ as a summative collection of related concepts, including ‘ethical dilemmas’, ‘moral dilemmas’, ‘moral challenges’, ‘ethical issues’, and ‘ethical conflicts’ [ 12 , 57 , 66 ], for example:

‘The expression “ethical challenges” mainly refers to ethical dilemmas and ethical conflicts as well as other scenarios where difficult choices have to be made’ [ 57 ] p34

Only one went on to define the other concepts they utilised, ‘ethical dilemmas’ and ‘ethical conflicts’:

‘Ethical dilemmas are described as situations that cannot be solved; decisions made between two options may be morally plausible but are equally problematic due to the circumstances. Ethical conflicts, on the contrary, arise when one is aware of the necessity of proper actions but he or she may have trouble exercising these actions because of certain internal or external factors.’ [ 57 ] p34

Approach 2: moral conflict, moral uncertainty or difficult choices

This approach anchors an ethical challenge to the requirement for an agent to make a (difficult) choice in a situation where moral principles conflict, or there is moral uncertainty as to the ‘right’ way forward.

‘In this context, ethical challenge refers to the situation whereby every alternative is morally wrong and still one has to make a choice’ [ 69 ] p676 ‘An ethical challenge occurs when one does not know how to behave and act in the best way…’ [ 14 ] p93

Approach 3: definition by study participants

Four of the definitions involved research participants themselves defining something as an ‘ethical challenge’ [ 12 , 48 , 50 , 56 ], with three studies explicitly stating that participants would lead this definitional work [ 48 , 50 , 56 ]. Draper & Jenkins offer a starting definition, adopted from Schwartz et al. [ 103 ] with which to prime participants, while Forbes and Phillips [ 50 ] and Jakobsen and Sørlie [ 56 ] left the definition fully with their participants (Table 3 ). Finally, Schofield et al. proposed a very broad definition (Table 3 ), alongside the specific statement that either participants or researchers could nominate something as an ‘ethical challenge’ [ 12 ].

Approach 4: emotional or moral distress

This final approach was to tie ethical challenges to situations where participants feel ‘discomfort’, emotional distress or more specifically moral distress or moral residue [ 14 , 66 , 81 ]. Larkin et al. are clear that this distress must be tied to moral causes, but Hem et al. and Storaker et al. also refer more broadly to ‘discomfort’ [ 14 ] and ‘emotional stress’ [ 81 ] respectively. For example:

‘In this article, ethical challenges refer to values that entail emotional and moral stress in healthcare personnel.’ [ 81 ] p557

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first rapid review to examine the use of the term ‘ethical challenge(s)’ in empirical healthcare research literature. Notably, only 12/72 (17%) of included studies published in the last 5 years contained a definition for ‘ethical challenge(s)’, despite this being the focus of the research being reported. The definitions identified were found in qualitative studies and systematic reviews and were evenly distributed geographically across high-, middle- and low-income settings. Definitions contained one or more of the identified approaches, although none contained elements from all four. Taken together, these findings suggest that a clear definition of ‘ethical challenge(s)’, and consistent use thereof, is currently lacking.

The four approaches indicate the diverse approaches to understanding ‘ethical challenge(s)’. Approaches 1 and 2 explore the concept from opposite viewpoints, with approach 1 looking from the conceptual perspective, through terms such as ‘dilemmas’ and ‘conflict’, and approach 2 from a participant perspective, specifically in those situations in which someone is trying to make a decision in circumstances where the preferred option is not possible or when they perceive there to be clash in values they feel are important. Within the concept-led definitions (approach 1), the use of a plurality of terms highlights a potential risk of bias, as different readers may interpret these differently. For example, some terms, such as ‘moral dilemma’, have relatively well understood specific meanings for some readers, particularly those with philosophical training [ 104 , 105 , 106 ]. The presence in the literature of specific and multiple meanings for some related terms highlights the importance of empirical studies providing a definition of these additional terms alongside their primary definition for ‘ethical challenge(s)’. This is more likely to be relevant where an a priori definition is used, but may be relevant to any prompting text for studies using a participant-led process, as in the study by Draper and Jenkins [ 48 ]. This clarity is important for both readers and future researchers who may undertake a secondary analysis of the data.

Approach 3 involves facilitating participants to nominate something as an ethical challenge [ 12 , 48 , 50 , 56 ]. This speaks to an important question about who, in a research context, is permitted to define or describe the object of interest, in this case ‘ethical challenge(s)’. Restricting the identification of ‘ethical challenge(s)’ to researchers alone may introduce bias by excluding input from those without bioethical ‘expertise’, but with important lived experience of the context under investigation. There is evidence that although clinicians can be sensitive to major ethical dilemmas, they can be less sensitive to small everyday ethical elements in clinical practice, and that ethical awareness varies between individuals [ 107 , 108 ]. Additionally, there is evidence in healthcare ethics research that patients and carers identify ethical challenges in situations that healthcare workers do not [ 109 ]. Therefore, relying entirely on a particular stakeholders’ perspectives (such as clinicians’) may risk missing important ethical challenges present in a scenario (assuming, of course, that we can settle what counts as an ‘ethical challenge(s)’).

In Approach 4, ethical challenges were linked to situations in which participants felt discomfort [ 14 ], emotional stress [ 81 ], moral distress or moral residue [ 66 ]. These concepts are themselves defined in quite varied ways (see, for example, definitions of ‘moral distress’ in a systematic review by Morley et al. [ 110 ]), potentially leading to additional conceptual confusion. Identifying triggers for moral distress is important, as high levels of moral distress are known to have negative impacts on work environments and lead to increased levels of compassion fatigue, increased staff turnover rates and poorer patient outcomes [ 110 , 111 , 112 ]. However, it is also possible that the requirement that, to be identified as an ethical challenge, the situation must invoke stress or distress might result in the under-identification of ethical challenges. We anticipate that many practitioners will daily manage multiple low-level ethical challenges, many of which will not generate moral distress or leave a moral residue. As such, the presence of moral distress may not be sufficient or even necessary in order to label a moral event an ‘ethical challenge’. However, the relationship between ‘ethical challenge(s)’ and moral distress is complex, and some might argue that the latter has an important relationship to the former. For example, moral distress, as conceived by Jameton and others [ 110 , 113 , 114 ], is linked to the after-effects of having to handle ethical challenge(s), so some researchers might view the generation of moral distress as relevant to identifying ethical challenges.

Although our review revealed these four approaches, the wider literature indicates there may be alternative approaches available. For example, other potential approaches would define ethical challenges as events that interact with moral principles, such as autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence or justice, as proposed by Beauchamp and Childress [ 115 ], or as events in which those principles clash, for example as used by Klingler et al. in their research focusing on ethical issues in health surveillance [ 116 ]. However, these approaches were not seen amongst our included papers.

Returning to our included papers, the high rates of use of closely related terms within included manuscript texts may add to difficulties in understanding the exact object of interest if these terms are being used as synonyms for ‘ethical challenge(s)’. This may be particularly the case if terms used include those such as ‘moral dilemma’, which (as shown above) will have specific meanings for some readers. Interchangeable, undefined usage of these terms by study authors within study texts risks further exacerbating the problems caused by a lack of definitional clarity.

Strengths and limitations

This rapid review is the first systematic attempt to describe the definitions of ‘ethical challenge(s)’ available within the recent published literature.

There are, however, five limitations to note. First, the review only includes results from the past 5 years, which inevitably means that older publications, which may have contained further definitions of ‘ethical challenge(s)’, were excluded. The focus on the previous 5 years does, however, allow for an assessment of the term’s use(s) within a reasonable period of time and was felt to be appropriate given the aims and resources available to this project.

Second, our three assumptions listed in the methodology section may have excluded some records that contained a relevant definition. However, these assumptions, and the resulting focus on two search terms, allowed for a balance between retrieved record numbers and team resources.

Third, the four databases searched were chosen for their focus on the healthcare ethics literature; we may therefore may have missed relevant usage in other fields or disciplines. Similarly, we did not search the grey literature, which might have excluded relevant research.

Fourth, for resource reasons, the assessment as to whether a related term was being used interchangeably in the text was undertaken by a single researcher (GS). This subjective assessment risks miscalculating both the number of interchangeable terms identified and the frequency counts.

Finally, we did not review the theoretical literature for conceptual definitions of ‘ethical challenge(s)’, hence the definitions we identified might not match completely conceptual understandings of the term. However, our review shows how the term is currently being used in the research literature. Indeed, if there are strong conceptual definitions within the theoretical literature, then it is clear that they are currently not reaching the researchers whose work was identified by our review.

This review is the first, to our knowledge, to identify and describe definitions (and uses) of the widely-utilised concept of ‘ethical challenge(s)’ within healthcare research. Only 17% (12/72) of retrieved papers presented an explicit definition of ‘ethical challenge(s)’ before beginning to investigate this concept in context. The definitions found contained one or more of four identified approaches, with significant cross-reference to related terms and concepts which themselves have variation in their accepted meanings. We recommend that researchers define the phenomenon of interest—in this case, ‘ethical challenge(s)’—to help ensure clarity. This should either be a priori, or, if using an approach that includes participant participation in the generation of the definition, reporting their final working definition a posteriori. The choice of definition should be justified, including the decision as to whether to include participants in this process. Additionally, if a definition references other conceptual terms, then consideration should be given to defining these as well.

The results of this rapid review suggest that a common conceptual understanding of the term ‘ethical challenge(s)’ is lacking within empirical bioethical research and that there is a need for researchers in this area to consider what conceptual formulations might be most useful. Again, failure to use definitions of crucial research concepts within empirical bioethics research potentially generates confusion and avoidable bias within research outputs, risking misleading ethical analyses, evaluations, and resulting recommendations. We therefore hope this review will help stimulate debate amongst empirical bioethics researchers on possible definitional content for such a commonly used term and prompt further discussion and research. Additionally, given the central role of patient and public partnership and involvement in research, further thought should be given to who should be involved in nominating something as a challenge worthy of study.

Following on from this work, there would be value in conducting an empirical bioethical project combining a full systematic review of definitions of ‘ethical challenge(s)’ (and related terms) integrated with an exploration of the conceptual literature to generate recommendations for approaches towards the content of potential definitions, perhaps related to the identified approaches above. Such a project could also ask authors who currently use the term ‘ethical challenge(s)’ in their research how they conceptualise this. Furthermore, work to better understand the benefits of including study participants in the definition process is also important. Finally, whilst researchers should justify whatever approach they choose to take, there may be merit in examining whether anything is lost if studies lack a robust or agreed definition, or whether doing so affords a flexibility and openness that allows for a broader range of ethical challenges to be identified.

Availability of data and materials

All data is presented in this manuscript.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist. 2018. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist.pdf . Accessed 16 Aug 2018.

Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups | The EQUATOR Network. https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/coreq/ . Accessed 2 Apr 2020.

Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations | The EQUATOR Network. https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/srqr/ . Accessed 2 Apr 2020.

Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Rashidian A, Wainwright M, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implement Sci. 2018;13:2.

Article Google Scholar

The EQUATOR Network | Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency of Health Research. https://www.equator-network.org/ . Accessed 2 Apr 2020.

Garritty C, Gartlehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, King VJ, Hamel C, Kamel C, et al. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;130:13–22.

Singh I. Evidence, epistemology and empirical bioethics. In: Cribb A, Ives J, Dunn M, editors. Empirical bioethics: theoretical and practical perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2016. p. 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139939829.006 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Ives J, Dunn M, Molewijk B, Schildmann J, Bærøe K, Frith L, et al. Standards of practice in empirical bioethics research: towards a consensus. BMC Med Ethics. 2018;19:68.

Mertz M, Inthorn J, Renz G, Rothenberger LG, Salloch S, Schildmann J, et al. Research across the disciplines: a road map for quality criteria in empirical ethics research. BMC Med Ethics. 2014;15:17.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1.

Cronin P, Ryan F, Coughlan M. Concept analysis in healthcare research. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2010;17:62–8.

Schofield G, Dittborn M, Huxtable R, Brangan E, Selman LE. Real-world ethics in palliative care: a systematic review of the ethical challenges reported by specialist palliative care practitioners in their clinical practice. Palliat Med. 2021;35:315–34.

Heggestad AKT, Magelssen M, Pedersen R, Gjerberg E. Ethical challenges in home-based care: a systematic literature review. Nurs Ethics. 2020;28:628–44.

Hem MH, Gjerberg E, Husum TL, Pedersen R. Ethical challenges when using coercion in mental healthcare: a systematic literature review. Nurs Ethics. 2018;25:92–110.

Lillemoen L, Pedersen R. Ethical challenges and how to develop ethics support in primary health care. Nurs Ethics. 2013;20:96–108.

Saarni SI, Halila R, Palmu P, Vänskä J. Ethically problematic treatment decisions in different medical specialties. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:262–7.

Self D, Skeel J, Jecker N. A comparison of the moral reasoning of physicians and clinical medical ethicists. Acad Med. 1993;68:852–5.

Ganann R, Ciliska D, Thomas H. Expediting systematic reviews: methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implement Sci IS. 2010;5:56.

Cameron A. Rapid versus full systematic reviews: an inventory of current mathods and practice in health technology assessment. Stepney: Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons; 2007.

Google Scholar

Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, Strifler L, Ghassemi M, Ivory J, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13:224.

Haby MM, Chapman E, Clark R, Barreto J, Reveiz L, Lavis JN. What are the best methodologies for rapid reviews of the research evidence for evidence-informed decision making in health policy and practice: a rapid review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2016;14:83.

Gough D, Thomas J, Oliver S. Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Syst Rev. 2012;1:28.

Watt A, Cameron A, Sturm L, Lathlean T, Babidge W, Blamey S, et al. Rapid reviews versus full systematic reviews: an inventory of current methods and practice in health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2008;24:133–9.

Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, Grimshaw J, Moher D. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev. 2012;1:10.

Stevens A, Garritty C, Hersi M, Moher D. Developing PRISMA-RR, a reporting guideline for rapid reviews of primary studies (Protocol). 2018. https://www.equator-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/PRISMA-RRprotocol.pdf . Accessed 6 Oct 2019.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ . Accessed 10 June 2021.

Strech D, Synofzik M, Marckmann G. Systematic reviews of empirical bioethics. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:472–7.

The Endnote Team. Endnote X9.2. Philadelphia, PA: Clarivate Analysis; 2013.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88.

Khalili M. Iranian nurses’ ethical challenges in controlling children’s fever. Int J Pharm Res. 2018;10:337–40.

Rezaee N. Ethical challenges in cancer care: a qualitative analysis of nurses’ perceptions. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2019;33:169–82.

Bartnik E. Ethical challenges in genetics. J Med Liban. 2019;67:138–40.

Alahmad G, Aljohani S, Najjar MF. Ethical challenges regarding the use of stem cells: interviews with researchers from Saudi Arabia. BMC Med Ethics. 2020;21:1–7.

Alahmad G, Al-Kamli H, Alzahrani H. Ethical challenges of pediatric cancer care: interviews with nurses in Saudi Arabia. Cancer Control. 2020;27:1073274820917210.

Alahmad G, Richi H, BaniMustafa A, Almutairi AF. Ethical challenges related to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: interviews with professionals from Saudi Arabia. Front Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.620444 .

Alahmad G, AlSaqabi M, Alkamli H, Aleidan M. Ethical challenges in consent procedures involving pediatric cancer patients in Saudi Arabia: an exploratory survey. Dev World Bioeth. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/dewb.12308 .

Bijani M, Mohammadi F. Ethical challenges of caring for burn patients: a qualitative study. BMC Med Ethics. 2021;22:1–10.

Bladt T, Vorup-Jensen T, Sædder E, Ebbesen M. Empirical investigation of ethical challenges related to the use of biological therapies. J Law Med Ethics. 2020;48:567–78.

Boulanger RF, Komparic A, Dawson A, Upshur REG, Silva DS. Developing and implementing new TB technologies: key informants’ perspectives on the ethical challenges. J Bioeth Inq. 2020;17:65–73.

Bourbonnais A, Rousseau J, Lalonde M-H, Meunier J, Lapierre N, Gagnon M-P. Conditions and ethical challenges that could influence the implementation of technologies in nursing homes: a qualitative study. Int J Older People Nurs. 2019;14:e12266.

Brodtkorb K, Skisland AV-S, Slettebø Å, Skaar R. Preserving dignity in end-of-life nursing home care: some ethical challenges. Nord J Nurs Res. 2017;37:78–84.

Bruun H, Lystbaek SG, Stenager E, Huniche L, Pedersen R. Ethical challenges assessed in the clinical ethics Committee of Psychiatry in the region of Southern Denmark in 2010–2015: a qualitative content analyses. BMC Med Ethics. 2018;19:62.

Canario Guzmán JA, Espinal R, Báez J, Melgen RE, Rosario PAP, Mendoza ER. Ethical challenges for international collaborative research partnerships in the context of the Zika outbreak in the Dominican Republic: a qualitative case study. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15:82.

Carnevale F, Delogu B, Bagnasco A, Sasso L. Correctional nursing in Liguria, Italy: examining the ethical challenges. J Prev Med Hyg. 2018;59:E315.

Delpasand K, Nazari Tavakkoli S, Kiani M, Abbasi M, Afshar L. Ethical challenges in the relationship between the pharmacist and patient in Iran. Int J Hum Rights Healthc. 2020;13:317–23.

Donnelly S, Walker S. Enabling first and second year doctors to negotiate ethical challenges in end-of-life care: a qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002672 .

Draper H, Jenkins S. Ethical challenges experienced by UK military medical personnel deployed to Sierra Leone (operation GRITROCK) during the 2014–2015 Ebola outbreak: a qualitative study. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18:77.

Ebrahimi A, Ebrahimi S. Pediatric residents’ and attending physicians’ perspectives on the ethical challenges of end of life care in children. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2018;11:16.

Forbes S, Phillips C. Ethical challenges encountered by clinical trials nurses: a grounded theory study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2020;47:428–35.

Gágyor I, Heßling A, Heim S, Frewer A, Nauck F, Himmel W. Ethical challenges in primary care: a focus group study with general practitioners, nurses and informal caregivers. Fam Pract. 2019;36:225–30.

Haugom W, Ruud E, Hynnekleiv T. Ethical challenges of seclusion in psychiatric inpatient wards: a qualitative study of the experiences of Norwegian mental health professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:879.

Hawking M, Kim J, Jih M, Hu C, Yoon JD. “Can virtue be taught?”: a content analysis of medical students’ opinions of the professional and ethical challenges to their professional identity formation. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:380.

Hyder A, Krubiner C. Ethical challenges in designing and implementing health systems research: experiences from the field. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2016;7:209–17.

Jackson C, Gardy JL, Shadiloo HC, Silva DS. Trust and the ethical challenges in the use of whole genome sequencing for tuberculosis surveillance: a qualitative study of stakeholder perspectives. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20:43.

Jakobsen R, Sørlie V. Ethical challenges: trust and leadership in dementia care. Nurs Ethics. 2016;23:636–45.

Jia Y, Chen O, Xiao Z, Xiao J, Bian J, Jia H. Nurses’ ethical challenges caring for people with COVID-19: a qualitative study. Nurs Ethics. 2021;28:33–45.

Kalkman S, van Thiel GJMW, Grobbee DE, Meinecke A-K, Zuidgeest MGP, van Delden JJM, et al. Stakeholders’ views on the ethical challenges of pragmatic trials investigating pharmaceutical drugs. Trials. 2016;17:419.

Kasper J, Mulye A, Doobay-Persaud A, Seymour B, Nelson BD. Perspectives and solutions from clinical trainees and mentors regarding ethical challenges during global health experiences. Ann Glob Health. 2020;86:34.

Kelley MC, Brazg T, Wilfond BS, Lengua LJ, Rivin BE, Martin-Herz SP, et al. Ethical challenges in research with orphans and vulnerable children: a qualitative study of researcher experiences. Int Health. 2016;8:187–96.

Kemparaj VM, Panchmal GS, Kadalur UG. The top 10 ethical challenges in dental practice in indian scenario: dentist perspective. Contemp Clin Dent. 2018;9:97.

Klitzman R. Unconventional combinations of prospective parents: ethical challenges faced by IVF providers. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18:18.

Komparic A, Dawson A, Boulanger RF, Upshur REG, Silva DS. A failure in solidarity: ethical challenges in the development and implementation of new tuberculosis technologies. Bioethics. 2019;33:557–67.

Laholt H, McLeod K, Guillemin M, Beddari E, Lorem G. Ethical challenges experienced by public health nurses related to adolescents’ use of visual technologies. Nurs Ethics. 2019;26:1822–33.

Laliberté M, Williams-Jones B, Feldman DE, Hunt M. Ethical challenges for patient access to physical therapy: views of staff members from three publicly-funded outpatient physical therapy departments. Narrat Inq Bioeth. 2017;7:157–69.

Larkin ME, Beardslee B, Cagliero E, Griffith CA, Milaszewski K, Mugford MT, et al. Ethical challenges experienced by clinical research nurses: a qualitative study. Nurs Ethics. 2019;26:172–84.

Mbalinda SN, Bakeera-Kitaka S, Amooti DL, Magongo EN, Musoke P, Kaye DK. Ethical challenges of the healthcare transition to adult antiretroviral therapy (ART) clinics for adolescents and young people with HIV in Uganda. BMC Med Ethics. 2021;22:1–14.

Mehdipour Rabori R, Dehghan M, Nematollahi M. Nursing students’ ethical challenges in the clinical settings: a mixed-methods study. Nurs Ethics. 2019;26:1983–91.

Mlughu TS, Anaeli A, Joseph R, Sirili N. Voluntary HIV counseling and testing among commercial motorcyclist youths: an exploration of ethical challenges and coping mechanisms in Dar es Salaam. HIVAIDS - Res Palliat Care. 2020;12:675–85.

Moeini S, Shahriari M, Shamali M. Ethical challenges of obtaining informed consent from surgical patients. Nurs Ethics. 2020;27:527–36.

Naseri-Salahshour V, Sajadi M. Ethical challenges of novice nurses in clinical practice: Iranian perspective. Int Nurs Rev. 2020;67:76–83.

Naseri-Salahshour V, Sajadi M. From suffering to indifference: reaction of novice nurses to ethical challenges in first year of clinical practice. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2019;24:251.

Nicholls SG, Carroll K, Zwarenstein M, Brehaut JC, Weijer C, Hey SP, et al. The ethical challenges raised in the design and conduct of pragmatic trials: an interview study with key stakeholders. Trials. 2019;20:765.

Pancras G, Shayo J, Anaeli A. Non-medical facilitators and barriers towards accessing haemodialysis services: an exploration of ethical challenges. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19:342.

Sabone M, Mazonde P, Cainelli F, Maitshoko M, Joseph R, Shayo J, et al. Everyday ethical challenges of nurse-physician collaboration. Nurs Ethics. 2020;27:206–20.

Seekles W, Widdershoven G, Robben P, van Dalfsen G, Molewijk B. Inspectors’ ethical challenges in health care regulation: a pilot study. Med Health Care Philos. 2017;20:311–20.

Segal AG, Frasso R, Sisti DA. County jail or psychiatric hospital? Ethical challenges in correctional mental health care. Qual Health Res. 2018;28:963–76.

Shayestefar S, Hamooleh MM, Kouhnavard M, Kadivar M. Ethical challenges in pediatrics from the viewpoints of Iranian pediatric residents. J Compr Pediatr. 2018. https://doi.org/10.5812/compreped.62747 .

Sinow C, Burgart A, Char DS. How anesthesiologists experience and negotiate ethical challenges from drug shortages. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2020;12:84–91.

Slettebø Å, Skaar R, Brodtkorb K, Skisland A. Conflicting rationales: leader’s experienced ethical challenges in community health care for older people. Scand J Caring Sci. 2018;32:645–53.

Storaker A, Nåden D, Sæteren B. From painful busyness to emotional immunization: nurses’ experiences of ethical challenges. Nurs Ethics. 2017;24:556–68.

Taebi M, Bahrami R, Bagheri-Lankarani N, Shahriari M. Ethical challenges of embryo donation in embryo donors and recipients. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2018;23:36.

Tønnessen S, Solvoll B-A, Brinchmann BS. Ethical challenges related to next of kin - nursing staffs’ perspective. Nurs Ethics. 2016;23:804–14.

Ullrich A, Theochari M, Bergelt C, Marx G, Woellert K, Bokemeyer C, et al. Ethical challenges in family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer—a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19:1–13.

Verma A, Smith AK, Harrison KL, Chodos AH. Ethical challenges in caring for unrepresented adults: a qualitative study of key stakeholders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:1724–9.

Morley G, Ives J, Bradbury-Jones C. Moral distress and austerity: an avoidable ethical challenge in healthcare. Health Care Anal. 2019;27:185–201.

Ayala-Yáñez R, Ruíz-López R, McCullough LB, Chervenak FA. Violence against trainees: urgent ethical challenges for medical educators and academic leaders in perinatal medicine. J Perinat Med. 2020;48:728–32.

Binns C, Lee M, Kagawa M. Ethical challenges in infant feeding research. Nutrients. 2017;9:59.

Čartolovni A, Habek D. Guidelines for the management of the social and ethical challenges in brain death during pregnancy. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2019;146:149–56.

Hofmann B. Informing about mammographic screening: ethical challenges and suggested solutions. Bioethics. 2020;34:483–92.

Hunt M, Pal NE, Schwartz L, O’Mathúna D. Ethical challenges in the provision of mental health services for children and families during disasters. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20:60.

Johnson S, Parker M. Ethical challenges in pathogen sequencing: a systematic scoping review. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:119.

MacDonald S, Shemie S. Ethical challenges and the donation physician specialist: a scoping review. Transplantation. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000001697 .

Saigle V, Racine E. Ethical challenges faced by healthcare professionals who care for suicidal patients: a scoping review. Monash Bioeth Rev. 2018;35:50–79.

Saigle V, Séguin M, Racine E. Identifying gaps in suicide research: a scoping review of ethical challenges and proposed recommendations. IRB Ethics Hum Res. 2017;39:1–9.

Wilson E, Kenny A, Dickson-Swift V. Ethical challenges in community-based participatory research: a scoping review. Qual Health Res. 2018;28:189–99.

Martins Pereira S, Hernández-Marrero P. Ethical challenges of outcome measurement in palliative care clinical practice: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Ann Palliat Med. 2018;7:S207–18.

Saghafi A, Bahramnezhad F, Poormollamirza A, Dadgari A, Navab E. Examining the ethical challenges in managing elder abuse: a systematic review. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.18502/jmehm.v12i7.1115 .