Milestone Documents

President John F. Kennedy's Inaugural Address (1961)

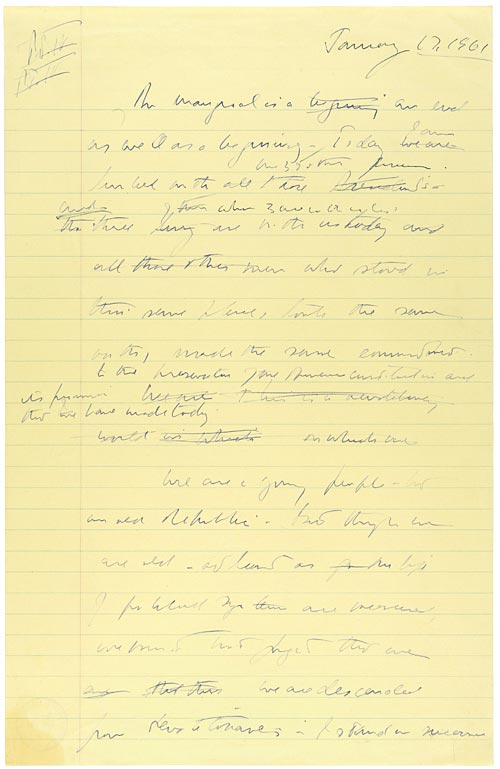

Citation: Inaugural Address, Kennedy Draft, 01/17/1961; Papers of John F. Kennedy: President's Office Files, 01/20/1961-11/22/1963; John F. Kennedy Library; National Archives and Records Administration.

View All Pages in the National Archives Catalog

View Transcript

On January 20, 1961, President John F. Kennedy delivered his inaugural address in which he announced that "we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and success of liberty."

The inaugural ceremony is a defining moment in a president’s career — and no one knew this better than John F. Kennedy as he prepared for his own inauguration on January 20, 1961. He wanted his address to be short and clear, devoid of any partisan rhetoric and focused on foreign policy.

Kennedy began constructing his speech in late November, working from a speech file kept by his secretary and soliciting suggestions from friends and advisors. He wrote his thoughts in his nearly indecipherable longhand on a yellow legal pad.

While his colleagues submitted ideas, the speech was distinctly the work of Kennedy himself. Aides recounted that every sentence was worked, reworked, and reduced. The meticulously crafted piece of oratory dramatically announced a generational change in the White House. It called on the nation to combat "tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself" and urged American citizens to participate in public service.

The climax of the speech and its most memorable phrase – "Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country" – was honed down from a thought about sacrifice that Kennedy had long held in his mind and had expressed in various ways in campaign speeches.

Less than six weeks after his inauguration, on March 1, President Kennedy issued an executive order establishing the Peace Corps as a pilot program within the Department of State. He envisioned the Peace Corps as a pool of trained American volunteers who would go overseas to help foreign countries meet their needs for skilled manpower. Later that year, Congress passed the Peace Corps Act, making the program permanent.

Teach with this document.

Previous Document Next Document

Vice President Johnson, Mr. Speaker, Mr. Chief Justice, President Eisenhower, Vice President Nixon, President Truman, Reverend Clergy, fellow citizens:

We observe today not a victory of party but a celebration of freedom--symbolizing an end as well as a beginning--signifying renewal as well as change. For I have sworn before you and Almighty God the same solemn oath our forbears prescribed nearly a century and three-quarters ago.

The world is very different now. For man holds in his mortal hands the power to abolish all forms of human poverty and all forms of human life. And yet the same revolutionary beliefs for which our forebears fought are still at issue around the globe--the belief that the rights of man come not from the generosity of the state but from the hand of God.

We dare not forget today that we are the heirs of that first revolution. Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans--born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage--and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today at home and around the world.

Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.

This much we pledge--and more.

To those old allies whose cultural and spiritual origins we share, we pledge the loyalty of faithful friends. United there is little we cannot do in a host of cooperative ventures. Divided there is little we can do--for we dare not meet a powerful challenge at odds and split asunder.

To those new states whom we welcome to the ranks of the free, we pledge our word that one form of colonial control shall not have passed away merely to be replaced by a far more iron tyranny. We shall not always expect to find them supporting our view. But we shall always hope to find them strongly supporting their own freedom--and to remember that, in the past, those who foolishly sought power by riding the back of the tiger ended up inside.

To those people in the huts and villages of half the globe struggling to break the bonds of mass misery, we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves, for whatever period is required--not because the communists may be doing it, not because we seek their votes, but because it is right. If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich.

To our sister republics south of our border, we offer a special pledge--to convert our good words into good deeds--in a new alliance for progress--to assist free men and free governments in casting off the chains of poverty. But this peaceful revolution of hope cannot become the prey of hostile powers. Let all our neighbors know that we shall join with them to oppose aggression or subversion anywhere in the Americas. And let every other power know that this Hemisphere intends to remain the master of its own house.

To that world assembly of sovereign states, the United Nations, our last best hope in an age where the instruments of war have far outpaced the instruments of peace, we renew our pledge of support--to prevent it from becoming merely a forum for invective--to strengthen its shield of the new and the weak--and to enlarge the area in which its writ may run.

Finally, to those nations who would make themselves our adversary, we offer not a pledge but a request: that both sides begin anew the quest for peace, before the dark powers of destruction unleashed by science engulf all humanity in planned or accidental self-destruction.

We dare not tempt them with weakness. For only when our arms are sufficient beyond doubt can we be certain beyond doubt that they will never be employed.

But neither can two great and powerful groups of nations take comfort from our present course--both sides overburdened by the cost of modern weapons, both rightly alarmed by the steady spread of the deadly atom, yet both racing to alter that uncertain balance of terror that stays the hand of mankind's final war.

So let us begin anew--remembering on both sides that civility is not a sign of weakness, and sincerity is always subject to proof. Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate.

Let both sides explore what problems unite us instead of belaboring those problems which divide us.

Let both sides, for the first time, formulate serious and precise proposals for the inspection and control of arms--and bring the absolute power to destroy other nations under the absolute control of all nations.

Let both sides seek to invoke the wonders of science instead of its terrors. Together let us explore the stars, conquer the deserts, eradicate disease, tap the ocean depths and encourage the arts and commerce.

Let both sides unite to heed in all corners of the earth the command of Isaiah--to "undo the heavy burdens . . . (and) let the oppressed go free."

And if a beachhead of cooperation may push back the jungle of suspicion, let both sides join in creating a new endeavor, not a new balance of power, but a new world of law, where the strong are just and the weak secure and the peace preserved.

All this will not be finished in the first one hundred days. Nor will it be finished in the first one thousand days, nor in the life of this Administration, nor even perhaps in our lifetime on this planet. But let us begin.

In your hands, my fellow citizens, more than mine, will rest the final success or failure of our course. Since this country was founded, each generation of Americans has been summoned to give testimony to its national loyalty. The graves of young Americans who answered the call to service surround the globe.

Now the trumpet summons us again--not as a call to bear arms, though arms we need--not as a call to battle, though embattled we are-- but a call to bear the burden of a long twilight struggle, year in and year out, "rejoicing in hope, patient in tribulation"--a struggle against the common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease and war itself.

Can we forge against these enemies a grand and global alliance, North and South, East and West, that can assure a more fruitful life for all mankind? Will you join in that historic effort?

In the long history of the world, only a few generations have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger. I do not shrink from this responsibility--I welcome it. I do not believe that any of us would exchange places with any other people or any other generation. The energy, the faith, the devotion which we bring to this endeavor will light our country and all who serve it--and the glow from that fire can truly light the world.

And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you--ask what you can do for your country.

My fellow citizens of the world: ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.

Finally, whether you are citizens of America or citizens of the world, ask of us here the same high standards of strength and sacrifice which we ask of you. With a good conscience our only sure reward, with history the final judge of our deeds, let us go forth to lead the land we love, asking His blessing and His help, but knowing that here on earth God's work must truly be our own.

Help inform the discussion

Presidential Speeches

January 20, 1961: inaugural address, about this speech.

John F. Kennedy

January 20, 1961

In his Inaugural Address, Kennedy pledges to support liberty, commit to allies, avoid tyranny, aid the underprivileged throughout the world, and strengthen the Americas. Kennedy challenges Communist nations to engage in a dialogue with the United States to ensure world peace and stability. The speech is best known for the words: "Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country."

- Download Full Video

- Download Audio

Vice President Johnson, Mr. Speaker, Mr. Chief Justice, President Eisenhower, Vice President Nixon, President Truman, Reverend Clergy, fellow citizens: We observe today not a victory of party but a celebration of freedom—symbolizing an end as well as a beginning—signifying renewal as well as change. For I have sworn before you and Almighty God the same solemn oath our forebears prescribed nearly a century and three quarters ago. The world is very different now. For man holds in his mortal hands the power to abolish all forms of human poverty and all forms of human life. And yet the same revolutionary beliefs for which our forebears fought are still at issue around the globe—the belief that the rights of man come not from the generosity of the state but from the hand of God. We dare not forget today that we are the heirs of that first revolution. Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans—born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage—and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today at home and around the world. Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty. This much we pledge—and more. To those old allies whose cultural and spiritual origins we share, we pledge the loyalty of faithful friends. United, there is little we cannot do in a host of cooperative ventures. Divided, there is little we can do—for we dare not meet a powerful challenge at odds and split asunder. To those new states whom we welcome to the ranks of the free, we pledge our word that one form of colonial control shall not have passed away merely to be replaced by a far more iron tyranny. We shall not always expect to find them supporting our view. But we shall always hope to find them strongly supporting their own' freedom—and to remember that, in the past, those who foolishly sought power by riding the back of the tiger ended up inside. To those peoples in the huts and villages of half the globe struggling to break the bonds of mass misery, we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves, for whatever period is required—not because the communists may be doing it, not because we seek their votes, but because it is right. If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich. To our sister republics south of our border, we offer a special pledge—to convert our good words into good deeds—in a new alliance for progress—to assist free men and free governments in casting off the chains of poverty. But this peaceful revolution of hope cannot become the prey of hostile powers. Let all our neighbors know that we shall join with them to oppose aggression or subversion anywhere in the Americas. And let every other power know that this Hemisphere intends to remain the master of its own house. To that world assembly of sovereign states, the United Nations, our last best hope in an age where the instruments of war have far outpaced the instruments of peace, we renew our pledge of support—to prevent it from becoming merely a forum for invective—to strengthen its shield of the new and the weak—and to enlarge the area in which its writ may run. Finally, to those nations who would make themselves our adversary, we offer not a pledge but a request: that both sides begin anew the quest for peace, before the dark powers of destruction unleashed by science engulf all humanity in planned or accidental self-destruction. We dare not tempt them with weakness. For only when our arms are sufficient, beyond doubt can we be certain beyond doubt that they will never be employed. But neither can two great and powerful groups of nations take comfort from our present course—both sides overburdened by the cost of modern weapons, both rightly alarmed by the steady spread of the deadly atom, yet both racing to alter that uncertain balance of terror that stays the hand of mankind's final war. So let us begin anew—remembering on both sides that civility is not a sign of weakness, and sincerity is always subject to proof. Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate. Let both sides explore what problems unite us instead of belaboring those problems which divide us. Let both sides, for the first time, formulate serious and precise proposals for the inspection and control of arms—and bring the absolute power to destroy other nations under the absolute control of all nations. Let both sides seek to invoke the wonders of science instead of its terrors. Together let us explore the stars, conquer the deserts, eradicate disease, tap the ocean depths and encourage the arts and commerce. Let both sides unite to heed in all corners of the earth the command of Isaiah—to "undo the heavy burdens . . . (and) let the oppressed go free." And if a beach-head of cooperation may push back the jungle of suspicion, let both sides join in creating a new endeavor, not a new balance of power, but a new world of law, where the strong are just and the weak secure and the peace preserved. All this will not be finished in the first one hundred days. Nor will it be finished in the first one thousand days, nor in the life of this Administration, nor even perhaps in our lifetime on this planet. But let us begin. In your hands, my fellow citizens, more than mine, will rest the final success or failure of our course. Since this country was founded, each generation of Americans has been summoned to give testimony to its national loyalty. The graves of young Americans who answered the call to service surround the globe. Now the trumpet summons us again—not as a call to bear arms, though arms we need—not as a call to battle, though embattled we are—but a call to bear the burden of a long twilight struggle, year in and year out, "rejoicing in hope, patient in tribulation"—a struggle against the common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease and war itself. Can we forge against these enemies a grand and global alliance, North and South, East and West, that can assure a more fruitful life for all mankind? Will you join in that historic effort? In the long history of the world, only a few generations have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger. I do not shrink from this responsibility—I welcome it. I do not believe that any of us would exchange places with any other people or any other generation. The energy, the faith, the devotion which we bring to this endeavor will light our country and all who serve it—and the glow from that fire can truly light the world. And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country. My fellow citizens of the world: ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man. Finally, whether you are citizens of America or citizens of the world, ask of us here the same high standards of strength and sacrifice which we ask of you. With a good conscience our only sure reward, with history the final judge of our deeds, let us go forth to lead the land we love, asking His blessing and His help, but knowing that here on earth God's work must truly be our own.

More John F. Kennedy speeches

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

'Ask Not...': JFK's Words Still Inspire 50 Years Later

Nathan Rott

During his inaugural speech on Jan. 20, 1961, U.S. President John F. Kennedy wasn't wearing a coat or hat in freezing weather as he spoke of beginnings and ends, war and peace, disease and poverty. AP hide caption

During his inaugural speech on Jan. 20, 1961, U.S. President John F. Kennedy wasn't wearing a coat or hat in freezing weather as he spoke of beginnings and ends, war and peace, disease and poverty.

It was cold in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 20, 1961 -- a day that would change the lives of many young Americans.

Bruce Birch woke to find the city at a near-standstill. Blanketed by eight inches of snow, the nation's capital reacted to the weather in much the same way it does a half-century later -- by pretty much shutting down.

Birch was a student from Midwestern College in Kansas who was studying at American University in D.C. for a semester. And for him, waiting out the weather wasn't an option.

History would be made that day. John F. Kennedy, the youngest man ever elected U.S. president and the first Roman Catholic, would be sworn in at the Capitol, some seven miles away. And Birch was determined to be there.

Watch a video about the writing of Kennedy's inaugural address.

"Being 19 years old, you sort of think you're invincible, so we figured we'd go anyway," he says.

He and a friend caught a bus from the university in Northwest Washington, got stuck in the snow in downtown D.C., and hiked the final two miles.

"I remember being very, very cold," he says. "It took us a long time to get there. It was literally still snowing and blowing."

Cold as it was, Birch says, "I always felt it was worth it."

A Challenge To America's Youth

Once there, huddled beneath a group of trees facing the Capitol, Birch heard what would become one of the most famous speeches in American history, a speech that would help shape his life -- and his generation.

Kennedy stepped to the podium. Famously, he wasn't wearing a coat or tie. Deeply tanned in the bright winter light, he stood out against the backdrop of bundled politicians and family. From the back of the crowd, Birch and his friend watched, passing a pair of shared binoculars back and forth. But it wasn't the images that stuck with them; it was the words.

John F. Kennedy stands on a platform for his inauguration on the east front of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 20, 1961, accompanied by his parents, Rose and Joseph Kennedy, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird Johnson. Hulton Archive/Getty Images hide caption

John F. Kennedy stands on a platform for his inauguration on the east front of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 20, 1961, accompanied by his parents, Rose and Joseph Kennedy, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird Johnson.

Kennedy started: "We observe today not a victory of party, but a celebration of freedom -- symbolizing an end as well as a beginning -- signifying renewal as well as change."

And he ended with a line that defined a generation: "And so, my fellow Americans: Ask not what your country can do for you -- ask what you can do for your country."

Kennedy's inaugural was as much a challenge to America's youth as it was a speech. And the challenge was not lost on Birch.

"I remember feeling very invigorated by it," Birch says. "Feeling at the end of the speech, man, this really makes me want to do something, to contribute."

That's what Kennedy's speech was intended to do. He touched on inspiration in many ways -- "the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans.… Now the trumpet summons us again.… I do not shrink from this responsibility -- I welcome it."

But none were as direct or memorable as the "Ask Not" line. That was the one that made service an American imperative.

Birch was one of the many listeners who took it to heart. He went on to become a teacher, a professor and, later, dean of Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C. -- positions he held for 38 years before retiring.

Words 'Like A Splash Of Water'

Donna Shalala was sitting on the floor of her residence hall at Western College for Women in Ohio that January day. The room was packed with freshmen, she remembered, but dead silent as everyone watched on a fuzzy black-and-white television set.

Shalala was a 19-year-old freshman with a lot of options.

"I could go to graduate school, I could go to law school," she says. "Before I heard the speech I was thinking of being a journalist, a war correspondent as a matter of fact."

But Kennedy's speech changed all that.

She remembers feeling like Kennedy wasn't addressing the nation, he was addressing her. And "he was talking about public service," she says.

She'd never considered public service until that day, until his words hit her "like a splash of water," as she puts it.

In 1962, Shalala was one of many young Americans who joined the newly-formed Peace Corps, an organization she called, "the embodiment of President Kennedy's call to our generation for service." Its first director, Kennedy's brother-in-law Sargent Shriver, died Tuesday.

Shalala went to a mud village in southern Iran, part of the Peace Corps' first batch of volunteers. It was a learning experience for everyone, she says. All the Iranians knew was that these kids were sent to help by an "energetic young president." And because of that, she says, they were welcomed.

For two years she taught at an agricultural college before returning to the U.S. where she earned her doctorate at Syracuse University.

Shalala went on to serve as a professor, president and chancellor at numerous colleges. In 1993, Bill Clinton made her his Secretary of Health and Human Services.

Today, Shalala is the president of the University of Miami. She's garnered many honors in her career, the most prestigious in 2008, when then-President George W. Bush awarded her the nation's highest civilian award -- the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

'He Spoke To All Of Us'

Gonzalo Barrientos was a freshman at the University of Texas when he heard the speech.

The son of farmers and cotton pickers in central Texas, Barrientos was studying business because it was a way to escape.

"I didn't want to stay in the cotton fields forever," he says. Barrientos wanted more -- not a lot more, just an opportunity to "go out and be a part of a place that had air-conditioning and carpet -- the niceties that life could provide in this country."

Barrientos figured that a business degree was the best way to do that. Kennedy's speech made him reconsider.

"It was what I had always learned about in books in elementary and high school about the American dream, even though I saw that American dream being shattered when I grew up," he says. Barrientos, now 69, dealt with poverty and racism growing up. So when Kennedy, "spoke for all of us, he spoke to all of us whether you were poor, rich, whatever color, whatever background as an American," he says. "That was especially inspiring to me."

Barrientos seized that inspiration. He switched majors, focusing on sociology, economics and government. He went on to train newcomers to the Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA), and in 1974 he became one of the first Mexican-Americans elected to the Texas state legislature.

He served in the House for 10 years and in the Texas Senate for 21 more. His goal: "to help the community, to help the poor people, to help the downtrodden, to empower those people to get the American Dream. All of which, I think, came from John Kennedy."

But the inspiration didn't strike everyone immediately. Bill Hilliard heard Kennedy's speech, but says it wasn't until two years later, on Nov. 22, 1963, that the words inspired him into action.

That morning, around the same time Kennedy was setting out in a motorcade in Dallas, a 21-year-old Hilliard was at work in Jackson, Mich., reading a letter he'd received that morning, "for the third or fourth time," he says.

More On John F. Kennedy

JFK, Digitized: Presidential Archive Debuts Online

The Two-Way

Jfk's assassination: 'changing from memory to history'.

The Picture Show

On jfk's 50th election anniversary, unpublished campaign photos.

"Greetings," it read, "You will report for induction into the U.S. Army at 0530, 5th of December, 1963, at the County Building."

It was a draft letter. But Hilliard didn't want to be a soldier. He was working at a small insurance business. He was in school, just in between semesters. He wanted to be an artist.

There was the anti-war movement, his own moral misgivings. He contemplated running to Canada. And then he heard the news.

Kennedy had been shot. He listened with his co-workers as the events unfolded.

"We just couldn't believe it," Hilliard says. "After it was confirmed, after Walter Cronkite made his announcement, I went upstairs and got an old copy of Life magazine, which had a picture of [Kennedy] on it. And on the page opposite of the photograph it said, 'Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.'"

Hilliard tore off the cover, painted "Closed in Memoriam," on the bottom, and taped it to the front door of the insurance business.

The next day, he enlisted in the Air Force. He traveled around the Pacific Rim for the next two years and in 1965, "The first time I was in Vietnam, we were in Da Nang and the words came back to me again about 'Ask not…'" he says.

"It was the reason I went in," Hilliard says, now 70. "It made me more of a patriot than I had ever been. I really believed in the country you know? It was a turning point, a real change of life and I wouldn't trade it for anything."

'It Still Clicks Today'

Fifty years later, it is another cold and quiet January day in the nation's capital.

From across the river, in Arlington National Cemetery, the white dome of the Capitol building, where Kennedy spoke and 1,038 days later, laid in state, is a blip on the horizon.

It's here, at Kennedy's gravesite, that pieces of his speech are etched in granite. Among them, the infamous "Ask Not," line that inspired Barrientos, Birch, Hilliard, Shalala, and countless others -- teachers, nurses, veterans and volunteers.

But half a century has passed. Those who heard those words and acted on them are reaching the end of their careers. Will Kennedy's challenge fade with the generation that carried it?

Andrew Collier, 21, from Tennessee, doesn't seem to think so. He says he learned the words in school, more times than he can count

"You think about it and it still clicks today, thinking about what you can do instead of trying to see what other people can do for you," he says.

It clicked for him. He's still tan from his most recent trip to New Orleans -- his sixth -- where he's helping to rebuild houses destroyed in Hurricane Katrina.

Laying new floors, putting up walls -- it's Collier's way of giving back, of answering his generation's challenges. And in a way, he's answering Kennedy's.

Even the next generation is familiar with Kennedy's words. Kole Hultgren, 6, was visiting the cemetery with his family and his dad, Randy Hultgren, a freshman Republican congressman from Illinois. The family says Kole knows the words well and asks him to recite them.

"Do not ask what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country," Kole says.

It isn't perfect. But it's close. And in the numbing cold, with the wind and snow, it doesn't seem all that different from what it must have been on that day, 50 years ago.

<strong data-cart-timer="" role="text"></strong>

President John F. Kennedy's Inaugural Address on January 20, 1961

Share This Video

- Copy to Clipboard

More Video to Explore

Digital stage.

Watch extraordinary performances from the Kennedy Center's stages and beyond.

Digital Stage+ Noseda and the NSO Perform Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony

Free to Members and Subscribers

Famed for its four-note opening, Beethoven’s Fifth is imaginative, violent, and brimming with drama.

In-Person and Livestreamed Millennium Stage

Wed. - Sat. at 6 p.m. ET

Experience something extraordinary live from the Kennedy Center. Attend in person or watch our livestreams and explore a video archive from over 20 years of great performances.

The Kennedy Center Honors

Explore our deep archive of video highlights from this annual event paying tribute to our nation's preeminent artists with performances by the great stars of today who have followed in their footsteps.

Watch the Full Show with a free Kennedy Center account.

By using this site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions which describe our use of cookies.

Reserve Tickets

Review cart.

You have 0 items in your cart.

Your cart is empty.

Keep Exploring Proceed to Cart & Checkout

Donate Today

Support the performing arts with your donation.

To join or renew as a Member, please visit our Membership page .

To make a donation in memory of someone, please visit our Memorial Donation page .

- Custom Other

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : January 20

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

John F. Kennedy inaugurated

On January 20, 1961, on the newly renovated east front of the United States Capitol, John Fitzgerald Kennedy is inaugurated as the 35th president of the United States.

It was a cold and clear day, and the nation’s capital was covered with a snowfall from the previous night. The ceremony began with a religious invocation and prayers, and then African American opera singer Marian Anderson sang “ The Star-Spangled Banner ,” and Robert Frost recited his poem “The Gift Outright.” Kennedy was administered the oath of office by Chief Justice Earl Warren .

During his famous inauguration address, Kennedy, the youngest candidate ever elected to the presidency and the country’s first Catholic president, declared that “the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans” and appealed to Americans to “ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

Born in Brookline, Massachusetts , in 1917, Kennedy was the son of Joseph Patrick Kennedy, a wealthy businessman. Both of his grandfathers were politicians, and his father served appointed positions in the Roosevelt administration, most prominently as U.S. ambassador to Britain. Kennedy volunteered to fight in World War II and was decorated for an August 1943 action in which he saved several of his men after the PT torpedo boat he was commanding was sunk in the South Pacific. In 1944, Kennedy’s older brother, Joseph, was killed in a bombing mission over Belgium. Joseph had planned to make a career in politics, and Kennedy, discharged and working as a reporter, decided to enter politics in his place.

He won the Democratic nomination for the 11th Congressional District of Massachusetts, defeated his Republican opponent, and became a U.S. congressman at the age of 29. Twice reelected, he was known in Congress for his foreign policy expertise, often taking a bipartisan stance when it came to issues of national security. In the election of 1952, in which the Republicans won the White House and majorities in Congress, Kennedy captured the Senate seat of Republican Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. after an intensive campaign.

In 1956, he nearly became the running mate of Democratic presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson, winning Kennedy wide national exposure and leading him to consider a bid for the 1960 presidential nomination. In 1957, he won the Pulitzer Prize for his book of biographical essays, Profiles in Courage, and in 1958, he was reelected to the Senate by the largest margin in Massachusetts history. By that time, Kennedy’s presidential campaign was in full swing.

The press embraced the young, idealistic senator and his glamorous wife, Jackie, and Kennedy’s father bought a 40-passenger aircraft to transport the candidate and his staff around the country. By the time the 1960 Democratic National Convention convened, Kennedy had won seven primary victories. On July 13, he was nominated on the first ballot, and the next day Senate majority leader Lyndon Johnson was chosen as his running mate. Opposed by Nixon and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., Kennedy performed well in televised debates with Nixon, a new addition to presidential politics. On November 8, he was elected president.

Kennedy, his wife, and family seemed fitting representatives of the youthful spirit of America during the early 1960s, and the Kennedy White House was idealized by admirers as a modern-day “Camelot.” In foreign policy, Kennedy actively fought communism in the world, ordering the controversial Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba and sending thousands of U.S. military “advisors” to Vietnam. During the Cuban Missile Crisis , he displayed firmness and restraint, exercising an unyielding opposition to the placement of Soviet missiles in Cuba but also demonstrating a level-headedness during negotiations for their removal. On the domestic front, he introduced his “New Frontier” social legislation, calling for a rigorous federal desegregation policy and a sweeping new civil rights bill. On November 22, 1963, after less than three years in office, Kennedy was assassinated while riding in an open-car motorcade with his wife in Dallas, Texas.

Also on This Day in History January | 20

Kamala harris becomes first female vice president.

First confirmed case of COVID-19 found in U.S.

Marvin gaye's hit single "what's going on" released, donald trump is inaugurated, barack obama is inaugurated.

This Day in History Video: What Happened on January 20

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

FDR inaugurated to fourth term

Hong kong ceded to the british, yasser arafat elected leader of palestine, iran hostage crisis ends, nazi officials discuss “final solution” at the wannsee conference, richard nixon takes office, president carter calls for olympics to be moved from moscow, fdr inaugurated to second term, ronald reagan becomes president.

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

JFK’s Inaugural Address

By julie baergen, unit objective.

This lesson on President John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address is part of Gilder Lehrman’s series of Common Core–based units. These units were written to enable students to understand, summarize, and analyze original texts of historical significance. Students will demonstrate this knowledge by writing summaries of selections from the original document and, by the end of the unit, articulating their understanding of the complete document by answering questions in an argumentative writing style to fulfill the Common Core Standards. Through this step-by-step process, students will acquire the skills to analyze any primary or secondary source material.

After completion of this unit, students will be able to:

- Analyze a document for understanding and cite explicit and/or inferred evidence from complex text to support their reasoning.

- Determine main ideas from a text.

- Determine the meaning of general academic words (Tier 2 vocabulary) and domain-specific words (Tier 3 vocabulary) as they relate to the studied document.

- Draw on information from multiple print or digital sources.

- Explain the effectiveness of the structure of President Kennedy’s Inaugural Address.

Unit Overview

A brief biography of President John F. Kennedy and an analysis of his Inaugural Address give students exposure to the thirty-fifth President of the United States, his perspective on the role of the United States as a contributor to global affairs, and US citizens’ responsibility to serve their country.

This study of JFK’s Inaugural Address goes beyond analysis of familiar quotations and explores the entire content of the address, including the structure, and ends with an examination of the speech in the context of events of the day. This series of lessons might be used during a study of American presidents, influential Americans, the Civil Rights Movement, etc., and can be used in English language arts as a model for student writing.

While the unit is intended to flow over a five-day period, it is possible to present and complete the material within a shorter time frame. For example, in a high school class or advanced middle school group, the first and second lessons can be used to ensure an understanding of the process with all of the activity (Sections A and B) completed in class on day one. The teacher can then assign lesson three (Section C) as homework. The concluding lessons four and five are completed in class on day two.

Possible Essential Questions

- "Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans . . . unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed."

What impact did President John F. Kennedy have on preserving human rights in America and the world?

- "Let both sides seek to invoke the wonders of science instead of its terrors. Together let us explore the stars, conquer the deserts, eradicate disease, tap the ocean depths and encourage the arts and commerce."

Do these ideas from the 1960s still have relevance today?

- JFK and speechwriter Ted Sorenson studied Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, as well as other past inaugural speeches, and consulted with friends and others for suggestions when drafting Kennedy’s address.

How are effective speeches constructed?

Introduction

In November 1960, at the age of 43, John Fitzgerald Kennedy (JFK) was the youngest man to be elected President of the United States. His Inaugural Address, given on January 20, 1961, is among the most recognizable presidential speeches and was the first ever to be broadcast on color television.

JFK was born into an influential Boston family of Irish descent in 1917. Following family tradition, he entered public service, first through serving in the US Navy and then in government, beginning with a seat in the US Senate in 1952.

Kennedy was both politically influential and a cultural icon. His family—wife Jacqueline Lee Bouvier and the couple’s two young children—captivated the American public.

Kennedy took office during a time of turbulence and change in the United States. Tensions were rising domestically, with civil rights issues coming to a head, as well as globally in relationships between the US and international powers (especially the Soviet Union, Cuba, and Southeast Asia). The Soviet satellite Sputnik launched the space age in 1957, and the United States was under pressure to compete. This is just a sampling of the challenges facing the Kennedy administration in 1961.

It is in this context that President Kennedy addressed the crowds on the Capitol steps in January 1961. A heavy snowfall the previous night did not stop the ceremony as Washington, DC, street maintenance crews scrambled to clear the path for the more than 20,000 people in attendance. JFK’s address to the American people lasted thirteen minutes and fifty-nine seconds and was well received. (For a complete biography of President John F. Kennedy see the Additional Resources section following this lesson plan.)

President Kennedy’s Inaugural Address provides many learning opportunities for students, but first they must understand the content of the document. Students will first read the document (abridged), then engage in a document analysis of the text. The full transcript of the speech is available at the National Archives . Students will benefit from hearing and seeing President Kennedy deliver his address through links provided in the materials section.

Additionally, Kennedy’s use of literary devices such as metaphor and imagery make this inaugural address an excellent model for students as they engage in their own writing.

In Lesson 1, students will complete an initial reading of JFK’s Inaugural Address. They will participate in a teacher-led shared reading of the text and analysis of the opening paragraphs (Section A) of the document.

- JFK’s Inaugural Address, January 20, 1961 (Abridged) – projected for whole class, and one copy per student

- Section A of JFK’s Inaugural Address Graphic Organizer – projected for whole class, and one copy per student

- Teacher Resource: Section A of JFK’s Inaugural Address Graphic Organizer Teacher Key

- Projection device

- Chart paper and markers for keeping records of class discussions

Procedure (Instruction and Assessment)

- Tell students they will be engaged in a series of lessons to analyze an important document in American history. The class will start out working together, and students will eventually be asked to do their own analysis of part of the document.

- Hand out a copy of JFK’s Inaugural Address, January 20, 1961 (Abridged) to each student and project the document for the class to see. Allow students an opportunity to read the document silently. Some students may not have the stamina to read the entire document. That’s ok; allow them to struggle a bit. Like exercising, the more students practice reading long documents, the longer they will be able to attend to the text. Students may make notes on their paper of questions they might have and/or words they don’t know. At this point try not to answer a lot of questions, but encourage students to ask them. In a later lesson students will be comparing this document to a historical timeline of events that may clear up some of their questions. Write students’ questions on chart paper and revisit them at the end of the lesson to see if any can be answered. After a reasonable period of time ask students to stop reading. Now would be a good time to record any questions students might have and start a list of words they are not familiar with. Try not to define words for students, but encourage them to use context clues to understand the meaning of words. Allow students to discuss the document and words with each other.

- The teacher will now begin a shared reading of the document. To share read the document the teacher begins reading Section A aloud, modeling fluency as the students follow along. After a few sentences the students read out loud with the teacher as the teacher continues to model fluent reading. The teacher may stop and think aloud as he/she reads to model good reader skills.

- After the shared reading, give each student a copy of the JFK’s Inaugural Address Graphic Organizer for Section A and also project it where students can see it as the teacher records responses during the whole class analysis of Section A.

- Explain to students that they will be re-reading this first section to select key words that will be used to create a summary sentence demonstrating understanding of what President Kennedy was saying in the opening paragraphs of the address.

- Key words are those words from the passage that must be there for comprehension of the text. Without them the selection would not make sense. Key words are usually nouns or verbs. They are not "connector" words (are, is, and, so, etc.). The number of key words depends on the length of the original selection. This selection has ninety-one words, so students can pick six or seven key words. The other rule is that students can’t pick words they don’t know. So as the class begins selecting key words, there will be opportunities to teach students how to use context clues, word analysis, and dictionary skills to discover word meanings, which is a more authentic and relevant way to learn.

- Students select the six or seven words from the text they believe are the key words and then write them in the box to the right of the text on their organizers.

- The teacher then asks the class for contributions to the class key word list. Through discussion and negotiation the class chooses their list of six to seven words. This discussion is an important part of the lesson as students are practicing communication skills while the teacher encourages and models cooperative learning behaviors. The discussion is also an opportunity for the teacher to listen carefully to student responses and make an informal check for understanding. Key words for Section A might be Americans, human rights, committed, survival, success, and liberty . (Short word combinations such as human rights are allowed when it makes sense to do so. Whole phrases, however, are not permitted.) Once negotiations are complete and the key words are chosen, or time runs out and the teacher makes the final decision, the students and the teacher write the class list of key words in the provided space on the graphic organizer.

- Next the teacher explains that the class will use the Key Words to write a sentence that restates or summarizes what President Kennedy was saying. For example: Americans are committed to the survival and success of human rights including liberty. This again is a whole-class negotiation process with the discussion being the most important part. The class may decide that some key words should be omitted to streamline the summary. The teacher and the students copy the final negotiated sentence into the designated space on the organizer.

- The final step in this analysis process is for students to put the summary statement using the author’s words into a summary statement using the students’ words. Again, this is a class discussion and negotiation process. For example: Americans will do anything necessary to ensure that all the human rights of all people of the world are protected .

- Using complete sentences and evidence from the text, ask students to answer the Questions to Consider . Solicit possible answers from the students. Use the students’ sentences for lessons in sentence structure, etc. This is also another opportunity to check for understanding.

- Wrap-up: Discuss the process with the students and review any vocabulary words that students found confusing or difficult. Review the questions students have and see if any can be answered at this time. Students may have questions that require some research. Challenge students to do this on their own and bring their findings to the next lesson.

In Lesson 2 students work in pairs or triads to continue their analysis of JFK’s Inaugural Address. Section B of the address identifies six pledges JFK made to the world on behalf of the United States. Students will decode each pledge to identify the essence of the pledge and to whom it was made. For each pledge students will provide a short answer to a comprehension check question.

- JFK’s Inaugural Address, January 20, 1961 (Abridged) – projected for whole class, and one copy per student.

- Section B of JFK’s Inaugural Address Graphic Organizer – projected for whole class, and one copy per student

- Teacher Resource: Section B of JFK’s Inaugural Address Graphic Organizer Teacher Key

- Tell students that today they will be working in small groups to complete analysis of Section B of JFK’s Inaugural Address. Set the stage for learning by reviewing the summary statement created in the first lesson. Allow students an opportunity to share any reflections on the lesson and results of any independent research. Record any student questions generated from the review.

- Using best practices for grouping students, seat students in work groups of two or three and provide each student with a copy of JFK’s Inaugural Address, January 20, 1961 (Abridged) . (The ideal would be for students to continue using their self-annotated copy from the previous lesson so they can add to their notes.)

- Allow students time to read Section B silently and then share read Section B of the address with students as done in Lesson 1. Ask students to work with their partner(s) to identify any patterns of writing they see and provide specific examples from the text. Students may observe that specific groups of people are being addressed, the word pledge is used multiple times usually followed by an action, and there is an explanation following the stated action. Share these patterns with the whole group. As students are working the teacher should be walking around the room listening to students’ conversations, guiding discussions, and keeping everyone on track.

- Provide a copy of Section B of JFK’s Inaugural Address Graphic Organizer to each student and project the organizer for students to see. The organizer for Section B is formatted differently from the organizer for Section A. This section of the address identifies six pledges JFK made to the world on behalf of the United States. Students will decode each pledge, identify the essence of the pledge and to whom it was made, and provide a short answer to a comprehension check question.

- The teacher explains to students that he/she will be modeling what students will be doing by completing the first pledge. After that students will work through each pledge one at a time with their partner(s), stopping after each pledge to check in with the whole class. Depending on the students’ abilities after the first two or three pledges students may continue to work on their own without the whole class check.

- The teacher thinks aloud as he/she first reads what is in the box to the right of the first pledge and identifies what the pledge is and to whom it is pledged, and provides a short answer to the question. Ask students what questions they have about the process. After these have been answered allow students to work with their partner(s) to complete the next pledge. Come together as a class to check responses and answer questions. Continue in this manner with the remaining pledges.

- Wrap-up: Review the list of recorded student questions and make note of any answers or record additional questions discovered during Lesson 2.

Share the limerick The Lady and the Tiger with students and ask students to explain the relationship between this limerick and the address. Explain to students that President Kennedy has used the literary device of allusion to make a point. (An allusion is a figure of speech whereby the author refers to a subject matter such as a place, event, or literary work by way of a passing reference. It is up to the reader to make a connection to the subject being mentioned. See http://literary-devices.com/ .) Challenge students to include an allusion in their next writing.

In Lesson 3 students continue to work in pairs or triads to analyze Section C of JFK’s Inaugural Address. The teacher will move throughout the room assisting students with guided conversations.

In Section C President Kennedy outlines his vision for America moving forward in the world.

- JFK’s Inaugural Address, January 20, 1961 (Abridged) – projected for whole class, and one copy per student

- Section C of JFK’s Inaugural Address Graphic Organizer – projected for whole class, and one copy per student

- Teacher Resource: Section C of JFK’s Inaugural Address Graphic Organizer Teacher Key

- Tell students that today they will continue working with JFK’s Inaugural Address in their work groups. At the end of the lesson groups will share their key words and summary statements with the class. Quickly review the summary statement from Lesson 1 and the pledges from Lesson 2. Record any findings from students’ independent research; record students’ answers or partial answers to the recorded questions from previous lessons.

- Be sure each student has their copy of the abridged inaugural address. Complete a shared reading of Section C with students as done in Lesson 1. Answer any questions students might have about the process for analyzing this section.

- Set a time limit for students to work in their groups to identify the key words. When time is up ask each group to share their list of key words and be ready to tell why they were chosen. This conversation sets the groups up for writing their summary statements.

- Each group will now use their key words to write a summary statement, and then re-state the summary in their own words. The teacher is continually moving from group to group guiding students as needed. Allow students to struggle with the process and coach them with guiding questions to find their own information. Check with the class near the end of the time period. Add more time if needed, or stop the activity and move to the next step if students don’t need the extra time.

- Give each group an opportunity to share their summary statements with the class. This could be done several ways: students share their graphic organizers with a document reader; students record their responses on chart paper and hang on the wall; etc.

- As work groups are sharing their findings, encourage discussion. This discussion will allow the teacher to check for understanding and broaden the understanding of the other groups. There will be a variety of responses. Responses should be accepted if students can reasonably defend them.

- Wrap Up: Kennedy’s descriptive writing paints vivid word pictures. Ask students to choose one or more example in this section and write about how Kennedy’s choice of words is used to persuade his audience. For example: Kennedy uses the phrase "a beachhead of cooperation may push back the jungle of suspicion . " A beachhead is defined in Merriam-Webster’s dictionary as "an area on a hostile shore occupied to secure further landing of troops and supplies." This paints the picture of people standing together against a common foe. The common foe in this case is described as a jungle of suspicion. Jungles are often dangerous, uncomfortable places. The jungle Kennedy describes is full of suspicion. Kennedy seems to be asking America and the world to stand together against these dangers. His reference to jungles and beachheads implies military action (as might be seen in the conflict to stop the spread of communism in Vietnam).

- This might be a good place to allow students to hear and see President Kennedy give his address:

- Video of JFK deliving his Inaugural Address, January 20, 1961 (John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum)

Ask students to listen to and observe President Kennedy as he speaks. Ask them to think about how the audio and visual presentation adds to the meaning of the address and to be prepared to share their ideas with the rest of the class.

Lesson 4 concludes the analysis of JFK’s Inaugural Address by asking students to complete the process individually. The teacher continues to move throughout the room assisting students with guided conversations.

In Sections D and E, President Kennedy challenges American citizens to participate in making his vision a reality. Section E includes the famous quotation "ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country."

- Sections D and E of JFK’s Inaugural Address Graphic Organizer – projected for whole class, and one copy per student

- Teacher Resource: Sections D and E of JFK’s Inaugural Address Graphic Organizer Teacher Key

- Tell students that today they will finish their analysis of JFK’s Inaugural Address by completing the last two, short sections on their own. Quickly review the summary statements from the previous lessons and the pledges from Lesson 2. Record any findings from students’ independent research; record students’ answers or partial answers to the recorded questions from previous lessons.

- Be sure each student has their copy of the abridged inaugural address. Complete a shared reading of Sections D and E with students as done in Lesson 1. Answer any questions students might have about the process for analyzing this section and encouraging them to take notes on their papers.

- Set a time limit for students to identify the key words, use the key words to write a summary statement, and re-state the summary in their own words for Section D. The teacher is continually moving from group to group guiding students as needed. Allow students to struggle with this exercise and coach them with guiding questions to find their own information. Check with the class near the end of the time period. Add more time if needed, or stop the activity and move to the next step if students don’t need the extra time.

- At this point ask students to meet with their work group partner(s) to share what they have accomplished. Give students about ten to fifteen minutes to discuss their responses with each other and make any changes.

- For Section E students return to their individual work and complete the activity as before. Student work is collected and checked for understanding.

In Lesson 5 students will compare a timeline of historical events from the 1950s to JFKs inaugural address. A sample timeline is included with this lesson, but teachers should feel free to add to it or create their own. After reading the events listed on the timeline students will look for references to the events in the inaugural speech, and, using evidence from the text, support their reasoning for the match.

- JFK’s Inaugural Address, January 20, 1961 (Abridged) – projected for whole class, and one copy per student and/or the student’s completed JFK’s Inaugural Address Graphic Organizer

- JFK Inaugural Address Timeline (Use the timeline provided, create your own, or find one available on the Internet.)

- Tell students that on this last day of working with the text they will be looking at the historical context of the inaugural speech. Kennedy’s address speaks to events of the day and what actions his administration planned to take. It is the students’ task to discover what parts of the inaugural address match up with the entries on the timeline. This will be a class project.

- Be sure each student has their copy of the abridged inaugural address and/or their completed graphic organizer. Their notes will help them as they begin the activity.

- Complete a shared reading of the events on the timeline. Answer any questions students might have about the process for analysis.

- Allow students to sit in their work groups to match the timeline entries to portions of the inaugural address and encourage them to make notes about why these texts match as they will be defending their work to the class.

- Follow up with a whole class discussion. Revisit the list of unanswered student generated questions. Now is the time to answer any questions that did not come up in the text analysis and/or assign further research to interested students.

Extension (optional)

Further Study: Students research answers to their questions generated through the document analysis. Possible topics might include anything related to civil rights, the space race, US foreign relations, etc.

Further Study: What impact did President Kennedy have on America and the world? AmeriCorps; Civil Rights; Foreign Policy; assassination; etc.

Writing: Use JFK’s Inaugural Address as a model for good writing. Challenge students to practice the literary devices Kennedy uses in their own writing. For example: replace everyday language with imagery; to make a point, allude to a place, event, or literary work that the writer’s audience would know; use parallelism to make sentences more interesting; use metaphors to clarify a concept; follow Kennedy’s pattern to organize an essay.

Additional Resources

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum : All sorts of resources are available for a study of the thirty-fifth President of the United States, including links to audio/visuals, primary documents, and on-line exhibits.

Literary Devices : An online dictionary of literary devices with detailed descriptions and examples.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

Who Wrote JFK’s Inaugural?

Does it matter.

I n my childhood imagination, John F. Kennedy slotted somewhere below DiMaggio and above De Niro in a loose ranking of latter-day American deities. When I was just a toddler, the late president left a lasting impression on me, literally, after I pulled a terracotta reproduction of Robert Berks’ iconic sculpture—weighing considerably less, thankfully, than the 3,000-pound original—down from a sideboard and onto my head. On my bedroom wall hung two plaques, one a list of “coincidences”—many trivial, some factually incorrect—between the political careers and assassinations of Kennedy and Abraham Lincoln. The other, also arguably incorrect, was a portrait of Kennedy embossed on black metal, staring out above his famous entreaty in all caps:

“ASK NOT WHAT YOUR COUNTRY CAN DO FOR YOU … ASK WHAT YOU CAN DO FOR YOUR COUNTRY.” J.F.K.

It’s no secret that presidents often speak words they themselves did not write. When George Washington delivered the very first inaugural address, on Apr. 30, 1789, he was reading from a reworked draft composed by his friend and frequent ghostwriter James Madison. In 1861, with the country on the brink of civil war, Lincoln pitched his address to a restive South and planned to end on the crudely formed question, “Shall it be peace or sword?” That is, until his soon-to-be Secretary of State William Seward suggested a less combative, more poetic conjuring of “mystic chords” and “the better angel guardian angel of the nation,” which Lincoln then uncrossed and altered to “the better angels of our nature.” Small matter, perhaps. We don’t require that our politicians be great writers, after all, only effective communicators, and they in turn sometimes benefit from a misattribution in perpetuity of someone else’s eloquence.

In Kennedy’s case, the gift of rhetoric was owed largely to his longtime counsel and legislative aide, Ted Sorensen, who later became his principal speechwriter after the two developed a simpatico understanding of oratory. In his 1965 biography Kennedy , Sorensen wrote:

As the years went on, and I came to know what he thought on each subject as well as how he wished to say it, our style and standard became increasingly one. When the volume of both his speaking and my duties increased in the years before 1960, we tried repeatedly but unsuccessfully to find other wordsmiths who could write for him in the style to which he was accustomed. The style of those whom we tried may have been very good. It may have been superior. But it was not his.

Kennedy believed his inaugural address should “set a tone for the era about to begin,” an era in which he imagined foreign policy and global issues—not least the specter of nuclear annihilation—would be his chief concern. But while Sorensen may have been the only person who could reliably give voice to Kennedy’s ideas, the coming speech was too historic to entrust to merely one man. On Dec. 23, 1960, less than a month before Kennedy would stand on the East Portico of the Capitol to take the oath of office, Sorensen sent a block telegram to 10 men, soliciting “specific themes” and “language to articulate these themes whether it takes one page or ten pages.”

Although Sorensen was without question the chief architect of Kennedy’s inaugural, the final draft contained contributions or borrowings from, among others, the Old Testament, the New Testament, Lincoln, Kennedy rival and two-time Democratic presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson, Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith, historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., and, we believe, Kennedy himself.

But an unequivocal puzzling out of exactly who wrote what is, with some exceptions, impossible. Late in his life, Sorensen, who died in 2010, admitted to destroying his own hand-written first draft of the speech at the request of Jacqueline Kennedy, who was deeply protective of her husband’s legacy. When pressed further, Sorensen was famously coy. If asked whether he wrote the speech’s most enduring line, for example, he would answer simply, “Ask not.” During an interview with Richard Tofel, author of Sounding the Trumpet: The Making of John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address , Sorensen seemed to suggest that preservation of the myth was more essential than any single truth about the man:

I recognize that I have some obligation to history, but all these years I have tried to make clear that President Kennedy was the principal author of all his speeches and articles. If I say otherwise, that diminishes him, and I don’t want to diminish him.

If Jacqueline Kennedy and Ted Sorensen were willing to tear up what may have been the only categorical proof of Sorensen’s primary authorship, President Kennedy—in an incident that can only be described as out-and-out deception—was willing to lie. On Jan. 16 and 17, 1961, at the Kennedy vacation compound in Palm Beach, Fla., Sorensen and JFK polished a near-final draft of the inaugural address and even typed it up on carbon paper. Later on the 17 th , the two flew back to Washington aboard Kennedy’s private plane, the Caroline , with Time correspondent Hugh Sidey, whose reporting on the president veered between the credulous and the hagiographic.

At some point during the flight, Kennedy began scribbling on a yellow legal pad in front of Sidey, as if working out just then his thoughts about the speech. What Kennedy in fact wrote was some of the precise language that had already been committed to typescript. During an interview with historian Thurston Clarke, author of Ask Not: The Inauguration of John F. Kennedy and the Speech that Changed America , Sidey recalled thinking, “My God! It’s three days before the inauguration, and he hasn’t progressed beyond a first draft?”

Not only had Kennedy progressed well beyond that, but he and Sorensen had nailed down what we know to be the penultimate version. Even worse, Kennedy later copied out by hand six or seven more pages—directly, one assumes, from the typewritten copy—and dated it “Jan 17, 1961.” After JFK’s assassination, the pages were displayed in what would become his presidential library and identified as an early draft.

There are a total of 51 sentences in the only text of the inaugural that now matters to the world, the speech as read on Jan. 20, 1961, though it can’t be said, without at least some conjecture, that Kennedy was the principal author of any one of them. I asked Tofel, who is now president of ProPublica, what it means that Kennedy may have been a mere messenger of what many Americans consider to be one of the most pivotal speeches of the 20 th century, second only to Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream”:

Kennedy lives on in our history not because of, frankly, enormous accomplishment—he died, at the most generous, before he could accomplish a great deal—but because of his ability to articulate, I think, our most profound values and highest aspirations much better than anyone has before or since. And that is his. It is not Sorensen’s. It is not Galbraith’s. It is not Schlesinger’s. We are talking about him at great length here 50 years after his death, and I believe we are doing that because of the power of words. And in that sense they are his words.

Should Sorensen’s original draft or other lost fragments ever materialize, whatever they might say is surely no match for the shrine that history has erected and the symbolism that hung on the walls of my childhood bedroom. And in that sense, those words belong to me.

Read more in Slate on the 50 th anniversary of the JFK assassination.

Spokane Mayor Lisa Brown to deliver inaugural State of the City Address on Tuesday

S pokane Mayor Lisa Brown will deliver her inaugural State of the City Address on Tuesday, April 30 at 11 a.m. at the Spokane Convention Center.

According to city officials, Brown's address will highlight her first 100 days in office and the strategies designed by the five transition committees. Overall, the address will give guests an exclusive peel into Mayor Brown's vision for Spokane going forward.

The address comes just one month after Brown revealed the city of Spokane is facing a $50 million deficit in its 2024 budget. Part of that deficit comes rising costs in public safety, with the police budget rising year after year.

Both the mayor and the city council are considering how to make up that deficit, including a levy they claim would raise nearly $200 million over the next five years.

Those interested in attending can register for the luncheon here.

A live stream of the mayor's address will be available on KREM.com, the KREM 2 YouTube channel and KREM 2+.

KREM ON SOCIAL MEDIA: Facebook | Twitter | Instagram | YouTube

DOWNLOAD THE KREM SMARTPHONE APP

DOWNLOAD FOR IPHONE HERE | DOWNLOAD FOR ANDROID HERE

HOW TO ADD THE KREM+ APP TO YOUR STREAMING DEVICE

ROKU: add the channel from the ROKU store or by searching for KREM in the Channel Store.

Fire TV : search for "KREM" to find the free app to add to your account. Another option for Fire TV is to have the app delivered directly to your Fire TV through Amazon.

To report a typo or grammatical error, please email [email protected] .

Gary mayor outlines vision for city’s comeback in State of the City address

GARY, Ind. (WNDU) - There’s no denying the decline of Gary over the last several years, but now the newest mayor plans to bring hope and create necessary change.

Mayor Eddie Melton gave his first 100 days progress report during his inaugural State of the City address on Tuesday at West Side Leadership Academy. He says he is on a mission to make Gary one of the greatest comeback stories ever.

The mayor highlighted some of his newest appointments — like Police Chief Derrick Cannon and Fire Chief Larry Tillman — focusing on safety with 15 new fire recruits, four new police officers graduating the academy soon, and both departments negotiating new union agreements with the city.

According to Mayor Melton, there’s been a 59% decrease in homicides from this time last year and an increase of safety on the water with an established 20-member dive team.

A big initiative for Mayor Melton has been infrastructure and tackling blight, pursuing state matched grants for street pavement, improving local roads and bridges, as well as demolishing rundown and abandoned structures in city neighborhoods.

The city is also working with the school of architecture at the University of Notre Dame about the possibilities for structures in Gary.

Melton says he’s focused on attaining these goals while being fiscally responsible, recently hiring a grant writer to secure as many funds as possible for these changes to attract more families to the area.

“So, the new grant writer that we have and that started about two weeks ago is helping to kind of lock in those federal dollars that’s helping us make those investments to make it more appealing and attractive,” Melton told WNDU 16 News Now after the address. “That’s why we’re investing in the downtown area. Most millennials and young professionals, they want to live around transit development districts, right? So, we’ll be to have a livable, walkable downtown. So, that’s the goal and objective.”

The biggest takeaway from Melton’s address is not to count Gary out.

“We have the world’s largest steel producing company in our backyard,” he explained. “We helped to build this nation. We helped build the bridges, the skyscrapers and things of that nature. We have so much to contribute still to this day.”

Copyright 2024 WNDU. All rights reserved.

2 dead after airplane crash in Bristol

Motorcyclist seriously injured after hitting deer in Marshall County

First Alert Weather: Rain chances on Friday, otherwise warm

Knute Rockne’s grave moved to Notre Dame

Shooting near Prosper Apartments ruled accidental

Latest news.

Wednesday’s Child: Kind Keaton

First Alert Weather

Family identifies 1 victim in Bristol plane crash that killed 2

Democracy under construction and under attack at the same time

A new book surfaces photos that captured the contradictions of a pivotal moment in american history..

A braham Lincoln is so familiar to Americans that it takes a special book to let us see him in a new way. Such a book is “Magnificent Intentions: John Wood, First Federal Photographer, 1856-1863,” freshly issued from Smithsonian Books. Compiled by Adrienne Lundgren, a photo conservator at the Library of Congress, it takes us back, viscerally, to a time when Lincoln’s inaugural was far from certain.

John Wood is not a well-known Civil War photographer. But this book establishes him as a critical eyewitness to our country’s darkest hour. As the first federal photographer, he had the job of taking pictures of infrastructure projects around the capital — especially the expansion of the US Capitol in the late 1850s.

An earlier, smaller version of the Capitol had been designed by a Bostonian, Charles Bulfinch, who also designed the Massachusetts State House. Unfortunately, his dome leaked, and Congress demanded a replacement that would be world-class, to match America’s grandiose ambitions.