Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

Case Studies of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation in India

DOI link for Case Studies of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation in India

Get Citation

This volume brings together a collection of case studies examining wildlife ecology and conservation across India.

The book explores and examines a wide range of fauna across different terrains and habitats in India, revealing key issues and concerns for biodiversity conservation, with a particular emphasis on the impact of humans and climate change. Case-studies are as wide-ranging as tigers, leopards, sloth bears, pheasants, insects, and birds, across a diverse range of landscapes, including forests, wetlands, and nature reserves, and even a university campus. Split into three parts, Part I focuses on how the distribution of animals is influenced by the availability of resources such as food, water, and space. Chapters examine key determinants, such as diet and prey and habitat preferences, with habitat loss also being an important factor. In Part II, chapters examine human-wildlife interactions, dealing with issues such as the impact of urbanisation, the establishment of nature reserves, and competition for resources. The book concludes with an examination of landscape ecology and conservation, with chapters in Part III focusing on habitat degradation, changes in land-use patterns, and ecosystem management. Overall, the volume not only reflects the great breadth and depth of biodiversity in India but offers important insights into the challenges facing biodiversity conservation not only in this region but worldwide.

This volume will be of great interest to students and scholars of wildlife ecology, conservation biology, biodiversity conservation, and the environmental sciences more broadly.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1 | 8 pages, introduction, part i | 102 pages, resource selection in protected and non-protected areas, chapter 2 | 7 pages, prey preferences of the large predators of asia, chapter 3 | 16 pages, habitat use pattern of indian leopard in western himalaya, chapter 4 | 16 pages, insight on the diet of the golden jackal, chapter 5 | 6 pages, blackbuck in agricultural landscape of aligarh, chapter 6 | 20 pages, seasonal variation in the diet of four-horned antelope, chapter 7 | 10 pages, do the niches of sympatric sparrows differ, chapter 8 | 15 pages, avifauna of suru valley, chapter 9 | 10 pages, indian robin, part ii | 86 pages, human-wildlife interaction, chapter 10 | 14 pages, human-tiger conflict in corbett tiger reserve, chapter 11 | 15 pages, ecological drivers of livestock depredation by large predators, chapter 12 | 13 pages, is resource sharing leading to human–bear interaction, chapter 13 | 10 pages, bird community structure in restored and unrestored areas in delhi, india, chapter 14 | 12 pages, impact of grazing on bird community in binsar wildlife sanctuary, chapter 15 | 11 pages, insect diversity in a semi-natural environment, chapter 16 | 9 pages, dipteran flies associated with abuse and neglect, part iii | 84 pages, landscape ecology and conservation, chapter 17 | 9 pages, conservation of pheasants in jammu and kashmir, chapter 18 | 12 pages, avifaunal diversity at baba ghulam shah badshah university campus, chapter 19 | 9 pages, distribution and conservation of kashmir gray langur, chapter 20 | 21 pages, forest classification of panna tiger reserve, chapter 21 | 16 pages, wetland inventory of aligarh district, chapter 22 | 10 pages, web of socioeconomic considerations for nature conservation in manipur, chapter | 5 pages.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

Introduction to Forest Resources in India: Conservation, Management and Monitoring Perspectives

- First Online: 05 August 2022

Cite this chapter

- Mehebub Sahana 5 ,

- G. Areendran 4 ,

- Krishna Raj 4 ,

- Akhil Sivadas 4 ,

- C. S. Abhijitha 4 &

- Kumar Ranjan 4

263 Accesses

India is known to have a vivid array of forests from the rainforests in Kerala to the alpine pastures in Ladakh and the desert pastures in Rajasthan to the evergreen forests situated in the north-east. Numerous parameters determine the type of forest such as climate, soil type, elevation and topography. Forests are categorized into diverse types based on the type of climate in which they are found, their nature and composition and their relationship with the surrounding environment. According to ISFR (2019), the total forest and tree cover of the country accounts for about 24.56% of the geographical area, which is 80.73 million hectares. 99,278 sq.km is covered by very dense forest, 3, 08,472 sq.km area is covered by moderately dense forest and 3,04,499 sq.km area is covered by open forest. According to the assessment in ISFR 2019, there was an observed upsurge of 5188 sq.km in the area covered by forest and tree cover combined, at the national level, as compared to the assessment carried out earlier in 2017. There was an upsurge in the area covered by overall forest and tree cover at the national level, but there was a decrease in the forest area in the country’s north-east region as emphasized in the report. It was also observed that Arunachal Pradesh had maximum species richness in terms of trees, shrubs and herbs followed by Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. Champion and Seth (A revised survey of the forest types of India. Govt. of India Publication, New Delhi, 1968) have used temperature and rainfall data for the classification of Indian forests into five major forest types and 16 minor forest types and more than 200 subgroups. In India, the major forest type groups are tropical semi-evergreen, tropical moist deciduous, littoral and swamp, tropical dry deciduous, tropical thorn, sub-tropical broad-leaved hill forests, sub-tropical dry evergreen, Himalayan moist and dry temperate, sub-alpine, montane wet temperate moist alpine scrub and dry alpine scrub. The tropical moist littoral and swamp forests of Sundarbans are constituted by mangroves. Mangroves are salt-tolerant plant communities that inhabit tropical and sub-tropical intertidal regions of the world and have developed into a good habitat for tigers. Though the diversity of forest resources in India is remarkable, the status of deterioration of these resources should also be monitored. The primary causing serious threats include loss of forest cover due to shifting cultivation, illegal felling, conversion of forest lands for urban expansion and other biotic pressures. Illegitimate cutting of trees has impacted the climatic conditions at a micro-level. It has affected the soil quality, hydrological cycle and biodiversity of the country, thus making the country more exposed to natural calamities and climate change. Most forests are under threat due to strong anthropogenic pressure, extensively due to collection of fuel wood and livestock grazing. Effective management strategies that take into account restoration and also promote judicious use of forest resources would ensure sustainability in the long run.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Forest Ecosystems of Jammu and Kashmir State

Forest Resources in Amhara: Brief Description, Distribution and Status

Sustainable Forestry Under Changing Climate

Addison, P.F.E., Cook, C.N., de Bie, K. (2016). Conservation practitioners’ perspectives on decision triggers for evidence-based management. Journal of Applied Ecology, 53(5), 1351-1357.

Article Google Scholar

Agar, R. (2019, November 22). The Importance of the Forest Ecosystem . Sciencing. Retrieved June 25, 2021 from https://sciencing.com/carbon-dioxide-absorbed-during-photosynthesis-3196.html .

Aggarwal, M. (2020, February 27) . The evolving story of India’s forests. Mongabay. Retrieved June 26, 2021 from https://india.mongabay.com/2020/02/the-evolving-story-of-indias-forests/

Anonymous. (2017). Deforestation Solutions. Retrieved from https://www.indiacelebrating.com/environmental-issues/deforestation-solutions/

Babbar, D., Areendran, G., Sahana, M., Sarma, K., Raj, K., & Sivadas, A. (2021). Assessment and prediction of carbon sequestration using Markov chain and InVEST model in Sariska Tiger Reserve, India. Journal of Cleaner Production, 278, 123333.

Google Scholar

Butler, R.A. (2019, April 01). Consequences of Deforestation . Mongabay. Retrieved June 25, 2021 from https://rainforests.mongabay.com/09-consequences-of-deforestation.html .

Chaitra, A., Upgupta, S., Bhatta, L.D., Mathangi, J., Anitha, D.S., Sindhu, K., Kumar, V., Agrawal, N.K., Murthy, M.S.R., Qamar, F., Murthy, I.K., Sharma, J., Chaturvedi, R.K., Bala, G., Ravindranath, N.H. (2018). Impact of Climate Change on Vegetation Distribution and Net Primary Productivity of Forests of Himalayan River Basins: Brahmaputra, Koshi and Indus. American Journal of Climate Change, 7, 271-294.

Chakravarty, S., Ghosh, S.K., Dey, A.N., Shukla, G. (2012). Deforestation: Causes, effects and control strategies. Retrieved June 28, 2021 from https://www.intechopen.com/books/global-perspectives-on-sustainable-forest-management/deforestation-causes-effects-and-control-strategies

Champion, H., Seth, S.K. (1968). A revised survey of the forest types of India. Govt. of India Publication, New Delhi.

Convention on Conservation of Migratory Species (n.d.). Protected Area Networks of India . Retrieved June 28, 2021 from http://cmscop13india.nic.in/index1.aspx?lsid=1087&lev=2&lid=79&langid=1

ENVIS Centre on Wildlife & Protected Areas (n.d.) Protected Areas of India . Retrieved June 28, 2021 from http://www.wiienvis.nic.in/Database/Protected_Area_854.aspx

Ferraro, P.J. & Pattanayak, S.K. (2006) Money for nothing? A call for empirical evaluation of biodiversity conservation investments. Plos Biology, 4, 482–488.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Forest Cover in Indian States and Union Territories (1987–2013). ENVIS RP on Forestry and Forest Related Livelihoods. Retrieved June 28, 2021 from http://www.frienvis.nic.in/Database/Forest-Cover-in-Indian-States-and-Union-Territories_1825.aspx

Forest Resources in India (n.d.). IndiaNetZone. Retrieved June 25, 2021 from https://www.indianetzone.com/40/forest_resources_india.htm .

Forest Survey of India. India State Forest Report-Volume I (2019). Retrieved June 27, 2021 from https://fsi.nic.in/isfr-volume-i?pgID=isfr-volume-i

Forest Survey of India. India State Forest Report-Volume II (2019). Retrieved June 27, 2021 from https://fsi.nic.in/isfr-volume-ii?pgID=isfr-volume-ii

Forest Survey of India. The State of Forest Report-Volume (1987). Retrieved June 27, 2021 from https://fsi.nic.in/documents/sfr_1987_hindi.pdf

Forest Survey of India. The State of Forest Report-Volume (2003) Retrieved June 27, 2021 from https://fsi.nic.in/documents/sfr_2003_hindi.pdf

GEF IEO. (2019). Evaluation of GEF Support to Scaling up Impact. Global Environment Facility Independent Evaluation Office, Washington, DC, USA.

Geographic Datasets (n.d.). Geoinformatics Resource Website. Retrieved June 28, 2021 from https://sites.google.com/site/georesweb/geographic-datasets

Gullison, R.E. (2003). Does forest certification conserve biodiversity? Oryx, 37(2), 153-165.

Gupta, S.R. (n.d.). Forest ecosystem: Forest Types of India. Pathshala. Retrieved June 26, 2021 from https://www.cusb.ac.in/images/cusb-files/2020/el/evs/forest_ecosystem_forest_types_of_India.pdf .

Kumari, R., Banerjee, A., Kumar, R., Kumar, A., Saikia, P., Latif, M. (2018). Deforestation in India: Consequences and Sustainable Solutions. Retrieved August 27, 2018 from https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/66710

Kumari, R., Banerjee, A., Kumar, R., Kumar, A., Saikia, P., Khan, M.L. (2019). Deforestation in India: Consequences and Sustainable Solutions. Retrieved June 28, 2021 from https://www.intechopen.com/books/forest-degradation-around-the-world/deforestation-in-india-consequences-and-sustainable-solutions

Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (2009). State of Environment Report. Retrieved August 27 from http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/StateofEnvironmentReport2009.pdf

Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (2019). Forest Conservation. Retrieved from: http://envfor.nic.in/division/forest-conservation .

Murcia, C., Guariguata, M.R., Andrade, Á., Andrade, G.I., Aronson, J., Escobar, E.M., Etter, A., Moreno, F.H., Ramírez, W., Montes, E. (2016). Challenges and prospects for scaling-up ecological restoration to meet international commitments: Colombia as a case study. Conserv. Lett., 9, 213-220.

National Forest Policy. (1988). Govt. of India, New Delhi.

Natural Resources—Forests (n.d.). ENVIS-Maharashtra. Retrieved June 25, 2021 from http://mahenvis.nic.in/Pdf/Forests_pdf .

Nichols, J.D. & Williams, B.K. (2006) Monitoring for conservation. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 21, 668–673.

Pawar, K.V., Rothkar, R.V. (2015). Forest Conservation & Environmental Awareness. Procedia Earth and Planetary Science, 11, 212-215.

Pearce, D.W. (2001). The Economic Value of Forest Ecosystems. Ecosystem Health, 7(4).

Pokhriyal, P., Rehman, S., Areendran, G., Raj, K., Pandey, R., Kumar, M., ... & Sajjad, H. (2020). Assessing forest cover vulnerability in Uttarakhand, India using analytical hierarchy process. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment, 6(2), 821-831.

Reserved Forests in India (n.d.). IndiaNetZone. Retrieved June 28, 2021 from https://www.indianetzone.com/50/reserved_forests_india.htm

Roshni S., Sajjad, H., Kumar, P., Masroor, M., Rahaman, M. H., Rehman, S., Ahmed, R., & Sahana, M. (2022). Forest Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Review for Future Research Framework. Forests, 13(6), 917.

Roy, D. (2020). On the Horns of a Dilemma’! Climate Change, Forest Conservation and the Marginal People in Indian Sundarbans. Forum for Development Studies, 47(2), 307-326.

Sahana, M., Sajjad, H., & Ahmed, R. (2015). Assessing spatio-temporal health of forest cover using forest canopy density model and forest fragmentation approach in Sundarban reserve forest, India. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment, 1(4), 1-10.

Sahana, M., Hong, H., Sajjad, H., Liu, J., & Zhu, A. X. (2018). Assessing deforestation susceptibility to forest ecosystem in Rudraprayag district, India using fragmentation approach and frequency ratio model. Science of the Total Environment, 627, 1264-1275.

Sanchez, P.A., Bandy, D.E. (1992). Alternatives of slash and burn: A pragmatic approach to mitigate tropical deforestation. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 64, 7-33.

Scherr, S.J. (1993). The evolution of agroforestry practices over time in the crop-livestock system in Western Kenya. USA: Oxford University Press.

Serageldin, I. (1991). Saving Africa’s Rainforests. Conference on the Conservation of West and Central Africa Rainforests . Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Singh, J.S., and Chaturvedi, R.K. (2017). Diversity of Ecosystem Types in India: A Review. Proc Indian Natn Sci Acad, 83(3), 569-594.

Stephenson, P.J. (2019). The Holy Grail of biodiversity conservation management: Monitoring impact in projects and project portfolios. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation, 17(4), 182-192.

Stephenson, P.J., Bowles-Newark, N., Regan, E., Stanwell-Smith, D., Diagana, M., Hoft, R., Abarchi, H., Abrahamse, T., Akello, C., Allison, H., Banki, O., Batieno, B., Dieme, S., Domingos, A., Galt, R., Githaiga, C.W., Guindol, A.B., Hafashimana, D.L.N., Hirsch, T., Hobern, D., Kaaya, J., Kaggwa, R., Kalemba, M.M., Linjouom, I., Manaka, B., Mbwambo, Z., Musasa, M., Okoree, E., Rwetsiba, A., Siams, A.B., Thiombiano, A. (2017). Unblocking the flow of biodiversity data for decision-making in Africa. Biol. Conserv., 213, 335-340.

Sutherland, W.J., Dicks, L.V., Ockendon, N., Petrovan, S.O., Smith, R.K. (2018). What Works in Conservation. Open Book Publishers, Cambridge, UK.

Tyagi, N., Das, S. (2018). Assessing gender responsiveness of forest policies in India. Forest Policy and Economics, 92, 160-168.

UNECE (n.d.). Carbon Sinks and Sequestration. Retrieved June 25, 2021 from https://unece.org/forests/carbon-sinks-and-sequestration .

United Nations ESCAP. (n.d.). Role of NGOs and major groups. Retrieved August 27 from https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/CH14.PDF .

World Resources Institute. (2014). Forest Legality Initiative. Retrieved from https://forestlegality.org/risk-tool/country/india

WWF ENVIS (n.d.). Core Environmental NGOs List. Retrieved August 27 from http://www.wwfenvis.nic.in/Database/EnvironmentalNGOs_5623.aspx .

WWF-India. (n.d.-a). Legal and Policy Frameworks related to Forest Conservation. Retrieved August 27 from http://awsassets.wwfindia.org/downloads/lecture_notes_session_9_1.pdf .

WWF-India. (n.d.-b). Retrieved August 27 from https://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/critical_regions/sundarbans3/wwf_india_s_interventions/

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Indira Gandhi Conservation Monitoring Centre, WWF-India, New Delhi, India

G. Areendran, Krishna Raj, Akhil Sivadas, C. S. Abhijitha & Kumar Ranjan

Department of Geography, School of Environment, Education and Development, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

Mehebub Sahana

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to C. S. Abhijitha .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Gopala Areendran

Krishna Raj

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Sahana, M., Areendran, G., Raj, K., Sivadas, A., Abhijitha, C.S., Ranjan, K. (2022). Introduction to Forest Resources in India: Conservation, Management and Monitoring Perspectives. In: Sahana, M., Areendran, G., Raj, K. (eds) Conservation, Management and Monitoring of Forest Resources in India. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98233-1_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98233-1_1

Published : 05 August 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-98232-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-98233-1

eBook Packages : Earth and Environmental Science Earth and Environmental Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Steering Committee

- Secretariat

- How to become a member

- Biodiversity

- Current status

- CBD / SEPLS / Satoyama Initiative

- Aichi Targets

- What is biodiversity ?

- Cuurent status

- What is CBD ?

- What is SEPLS ?

- What is Satoyama Initiative ?

- Meetings and events

- IPSI collaborative activities

- Case studies

- Members’ activities

- CASE STUDIES

- IPSI Collaborative Activities

- IPSI Global Conference

- Regional Workshop

- Other events

- ">Announcements

- Announcements

- Publications

- CBD related

TOP CASE STUDY Mainstreaming Community-Conserved Areas (CCAs) for biodiversity conservation in SEPLS - A case study from Nagaland, India

Mainstreaming Community-Conserved Areas (CCAs) for biodiversity conservation in SEPLS - A case study from Nagaland, India

SUBMITTING ORGANIZATION

The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI)

DATE OF SUBMISSION

13 December 2019

India (Nagaland)

CCA; Tizu valley; Sema community; Zunheboto; Nagaland

Siddharth Edake, Pia Sethi, Yatish Lele

Summary Sheet

The summary sheet for this case study is available here .

In Nagaland, located within the Indo-Burma and Himalaya biodiversity hotspots in India, customary rights are protected by the Indian Constitution, and the majority of natural habitats (88.3%) are owned and managed by individuals and clans overseen by village councils, district councils and other traditional institutions. However, in the absence of alternative livelihood options, most of the economic activities in the villages are based upon utilization of natural resources. This has led to over exploitation of forest resources and threats to biodiversity due to the increasing needs of local people. However, in Nagaland, traditional conservation practices have helped protect biodiversity, and there are records of Community-Conserved Areas (CCAs) being declared in the early 1800s, especially in response to forest degradation and loss of wildlife. Thus, the revival of traditional conservation practices through the creation of CCAs offers hope for conservation and ecosystem resilience, as communities set aside parcels of forests within productive, shifting cultivation landscapes. It has been documented that one-third of Nagaland’s villages have constituted CCAs, and as many as 82% of 407 CCAs have completely or partially banned tree felling and/or hunting, and enforce various regulations for conservation. These CCAs, covering more than 1,700 km 2 , also contribute to carbon storage (an estimated 120.77 tonnes per ha), and are an important mitigation and adaptation strategy for climate change.

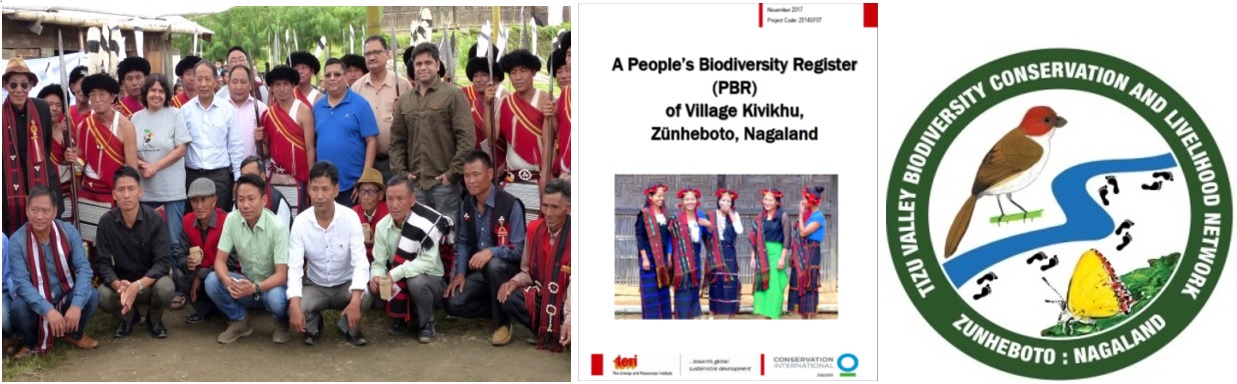

A pilot scale project was initiated in the three villages of Sukhai, Kivikhu and Ghukhuyi in Zunheboto district of Nagaland, which aimed at creating and linking Community-Conserved Areas across the landscape and supporting conservation through livelihood creation. The model adopted aimed at strengthening the resilience of these mountain communities and their forests by rejuvenating traditional conservation practices and providing supplementary livelihoods. Activities included compiling information on Indigenous Ecological Knowledge (IEK), developing long-term ecological monitoring mechanisms, motivation and sensitization on landscape conservation and capacity building of the community members in biodiversity identification, documentation and monitoring, as well as promoting ecotourism as a livelihood option. Today, the project has yielded positive results in terms of sustainable use of biological resources by adopting long-term sustainability, enhanced governance and effective conservation of SEPLs. Around 222 species of birds and 200 species of butterflies have been documented and protected by declaring 939 hectares as CCAs and banning hunting and destructive fishing across the remaining landscape of forests and rivers (total area being 3,751 hectares). The positive impacts of the project activities were evident at the end of the project as communities reported increased protection of natural resources after the formation of a joint CCA and improvement in management of common resources of SEPLs. The elders were satisfied with the documentation of their indigenous knowledge in the People’s Biodiversity Registers (PBRs) while the youth, women’s groups and the marginalized members of the community reported increased household income due to ecotourism. This model of biodiversity conservation is being mainstreamed within the governance mechanism and up-scaled through a multi-pronged approach including financial support, legal recognition and long-term ecological monitoring.

Figure 2. Land use, land cover and contour map of case study sites – CCA (Source: TERI 2017)

1. Introduction

The state of Nagaland in India, which is a part of both the Indo-Burma and Himalaya biodiversity hotspots, has a forest cover of 12,868 km² that accounts for 77.62% of the state’s total geographical area (FSI 2017). It also supports remarkable floral and faunal diversity with high levels of endemism. Naga tribes who inhabit Nagaland follow customary laws and procedures, and their customary rights are protected under Article 371 A of the Constitution of India (see Box 1). These customary laws are plural in nature and differ from tribe to tribe and village to village. The Nagas belong to an oral culture which they have practiced through the ages till present times, where every aspect of life is governed through time-honored customs and practices. These practices have not yet been codified.

Box 1 Article 371 A of the Indian Constitution

Article 371 A: Special provision with respect to the State of Nagaland

Notwithstanding anything in this Constitution, no Act of Parliament in respect of:

– Religious or social practices of Nagas

– Naga customary law and procedure

– Administration of civil & criminal justice involving decisions according to Naga customary law, &

– Ownership and transfer of land and its resources,

… shall apply to the State of Nagaland unless the Legislative Assembly of Nagaland by a resolution so decides.

The governance structure in Nagaland is a combination of customary decision-making processes combined with a statutory system set up by the state and central governments (Pathak and Hazarika, 2012). Hence as per the customary rights, the majority of natural habitats are owned and managed by individuals and clans overseen by village and district councils and other traditional institutions. But, in the absence of alternative livelihood options, most of the economic activity in the villages is based upon utilization of natural resources leading to over exploitation of forest resources. Wildlife hunting has always been a way of life for the Naga tribes, but rampant and unregulated hunting has seriously depleted wildlife populations. Nevertheless, traditional conservation practices help protect biodiversity, and there are records of Community-Conserved Areas being declared in the early 1800s, especially in response to forest degradation and loss of wildlife (Pathak 2009). According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, Community-Conserved Areas (CCAs) are defined as, “natural and/or modified ecosystems containing significant biodiversity values, ecological services and cultural values, voluntarily conserved by indigenous, mobile and local communities through customary laws and other effective means” (IUCN 2009). These CCAs include forests, freshwater resources, grasslands as well as agricultural-forest complexes within their ambit. One of the major characteristics of these CCAs is that the communities are the decision-makers, and have the capability to enforce regulations. Regulations and rules range from provisioning rules like patrolling and social fencing to appropriation rules like regulating collection of different forest products, restrictions on grazing, bans on felling of trees or bans on hunting. These bans may take many forms depending on the local situation. For example, a wide range of practices are in force for regulating hunting, which may range from blanket bans on hunting of all species through the year, to seasonal restrictions (e.g. during the breeding season), to bans on hunting particular species believed to be particularly vulnerable. Furthermore, when populations are perceived to be endangered, then the types of hunting weapons may be specified (e.g. use of only traditional traps and snares that are less detrimental than guns, or of fishing nets and traditional traps, while dynamite, electric currents, use of glue and poison are shunned). Similarly, the local communities may restrict wild meat consumption for subsistence purposes, banning the sale of wildlife or forest products in local markets or for commercial purposes. The motivations for declaring the CCA appear to be multiple—foremost being concern for forest degradation, followed by declining numbers of key wildlife species due to hunting and water scarcity (TERI 2015). However, CCAs face numerous challenges in their creation, effectiveness and sustainability and require sustained efforts for their conservation. This case study highlights the importance of Community-Conserved Areas (CCAs) in the socio-ecological production landscape (SEPL) of Nagaland in India.

2.1 Study site

Three villages, Sukhai, Ghukhuyi and Kivikhu, lying in the southern region of Zunheboto district bordering Phek district in the state of Nagaland, were selected as a pilot site under the work initiated by The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) with support from Conservation International Japan via a Global Environment Facility (GEF) Satoyama grant (see Fig. 1). The pilot site lies in the heart of Nagaland at an altitude of 1,900 m and has sub-tropical wet hill forest primarily overlapping with the sub-tropical pine forest (see Fig. 2). The area acts as an important green corridor between the biodiversity-rich forests of the Satoi range and the Ghosu bird sanctuary and harbors endangered and threatened species like the Blyth’s tragopan ( Tragopan blythii ), fishing cat ( Prionailurus viverrinus ) and Chinese pangolin ( Manis pentadactyla ). The Tizu River, which flows through to these villages, harbors a number of IUCN Red List fish species.

The pilot villages are dominated by the Sema tribe, and the economy is largely agriculture and forest-centered. Though farming is mainly for subsistence, high dependence prevails on the other abundant resources of jhum (shifting cultivation) lands, which include timber, medicinal plants and non-timber forests products. Wildlife is an important resource for the communities and is exploited for various reasons, including food, additional income, cultural practices and as a sport. The overall socio-ecological production landscape (SEPL) comprises of a mosaic of different vegetation types and can be broadly categorized as primary forests, secondary forests, jhum land and plantations.

2.2 Multiple values of the SEPLs and challenging issues faced

The socio-ecological production landscapes of Zunheboto provide the local people with almost all of their daily subsistence and survival needs, apart from contributing to their rich cultural heritage, folklore and traditions. Landscapes of this area are comprised of diverse elements—subtropical forests interspersed with jhum fields and differentially aged, regenerating jhum fallows. Jhum is basically ‘farming the forest’, where patches of forests are cleared for cultivation and then abandoned to fallow for several years. In Nagaland, this system of shifting cultivation ensures that even landless farmers are allocated patches of forest to farm and is perhaps a reason for the high forest cover of Northeast India (Northeastern forests account for 25% of India’s forest cover). Consequently, the people farm in the forest and the two are perceived to be inextricably linked by the local communities. The forests provide enormous benefits to the local communities in terms of ecosystem services such as timber, fuelwood and forest products. Food production is enhanced owing to the location within the forests (for example through enhanced pollination, water flows, nutrient enrichment, and natural fertilizers). The jhum fields sustain a diversity of local varieties of crops (e.g. Miyeghu , which is the local variety of paddy) that feed the people and their livestock. The rivers flowing through their lands irrigate their fields and forests and provide them with fish. In the valley areas adjoining the rivers, the people also grow paddy in a pani-kheti system (water fed agriculture/terrace farming). Local landraces are preferred and grown, including the Naga Mircha ( Capsicum chinense ) and the Nagaland tree tomato or tamarillo ( Cyphomandra betacca ), that have recently acquired the Geographical Indication (GI) tag as directed by the Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement.

Traditionally, the Naga tribes had an intimate relationship with nature and their SEPLs are based on a foundation of the interconnectedness of God, people and nature. This is reflected in their rich folklore on the plants and animals of their forests. Some of these stories underline the ecological role that animals play in the ecosystem and their contribution to ‘ecosystem services’ for human beings. For example, the role of the earthworm in enhancing soil fertility is transmitted through a folktale (TERI 2017). The value of their SEPLs was culturally realized and codified through wise use—for example, the killing of pregnant animals and birds was a taboo that would bring misfortune to the hunter and his family. Fishing and the use of certain poisonous roots and leaves that kill fishes in the rivers or springs during the spawning season were also restricted (Lkr & Martemjen 2014).

The Naga people in general consider all land to be sacred. Jhuming , or shifting cultivation, involves clearing the land and burning the jungle, so people propitiate the spirit with rice, crabs and rice beer to beg for forgiveness for the many animals, plants, birds and reptiles that might be inadvertently harmed. The entire lives of the Sema people revolve around their forest-farm landscape. All the cultural festivals of the local people are linked to their agricultural calendar, and the Sema people’s agricultural calendar in turn is attuned to nature, guided by the movement of the stars or of birds—their migration patterns, breeding seasons and songs. For example, the sowing of paddy is initiated only when the constellation of Orion ( Phogwosiilesipfemi ) is at its zenith or after the kashopapu , a species of cuckoo, is heard calling (Hutton 1921).

For the local Sema communities, a vibrant well-functioning SEPL implies that abundant wild fauna is present in their forests, and easily sighted when they jhum their fields, and that fish catches are abundant, large-sized and diverse, consisting of many species. Forests are protected at the top of hills so that their watershed services are enhanced. For example, in the pilot village of Kivikhu, the main source of water for drinking and household activities is located 2.5 km from the village boundary on a mountain top in an area that is locally called Shoshemi-ghoki ( ghoki meaning stream). Traditionally, lengthening of the jhum cycle provides improved scope for natural biodiversity to regenerate. This is an extremely positive sign as jhuming is an excellent way to protect forests and associated biodiversity and yet produce crops, provided that long fallow periods allow for the forest to regrow (see Fig. 3).

Of the issues currently faced in managing the SEPLs, the main challenge is the decreasing jhum cycles. Earlier when a forest patch was cleared, each patch was cultivated for only one to two years and then left to regenerate for upwards of 15 years. However, the decreasing jhum cycles at present (less than seven years and often only for three to five years) prevent effective regeneration and lead to much soil erosion. Given the dependence of the local community on forest cover for a variety of provisioning and regulating ecosystem services, loss of forest cover has affected agriculture and the availability of water for domestic and agricultural use.

Though wildlife hunting is an age-old practice and a culturally embedded practice in the Naga way of life, the use of guns has become increasingly common, and is popular due to the easier and higher probability of killing prey than traditional ways of hunting. This has led to rapid depletion of wildlife with many species on the brink of local extinction. Aggressive fishing using poisons (such as bleach and lime powder), dynamite and electrocution using battery packs has also led to reduction in fish populations of the Tizu River flowing through the villages. Fear of losing all the fish and the natural ecosystem is one of the reasons that led to local communities to declare a reserve in their mountainscape. As a wise-use practice, they believe that fish and other animal species breed in the reserved areas and their populations are revitalized and replenished over time (see Fig. 4).

2.3 Description of activities

Though a reserve area has been in existence since 2002, it did not contribute to conservation in the absence of a well-delineated program to safeguard ecosystems and conserve SEPLs. To ensure conservation of large contiguous forest areas, it was decided to mobilize support to link the community-conserved areas, revive traditional conservation practices, carry out ecological assessments of these CCAs, develop community-based ecotourism initiatives and formalize and mainstream a network of CCAs along with the Nagaland Government and the State Forest Department.

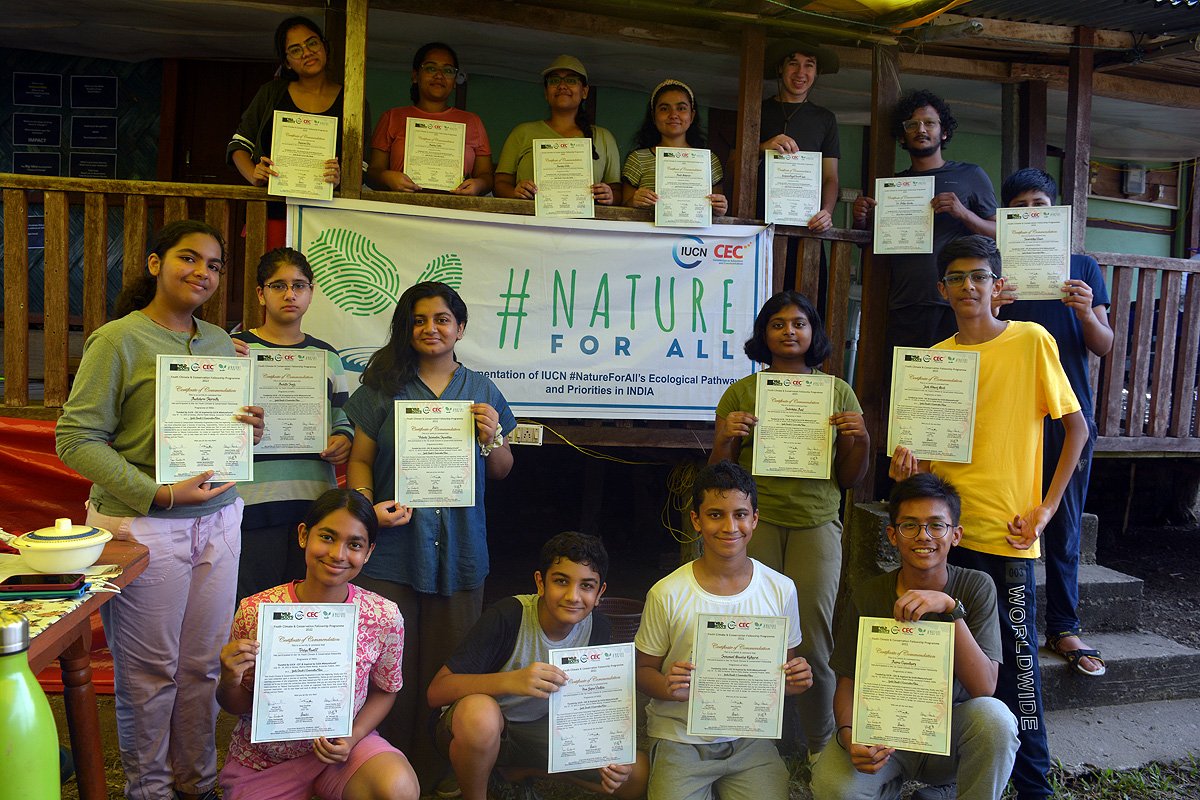

Several deliberations were held with the communities of the three pilot villages of Sukhai, Ghukhuyi, and Kivikhu, to form a joint CCA Management Committee in order to enforce rules that ban hunting, fishing, and logging as well as collection of medicinal plants in the designated CCAs, and to prepare biodiversity registers to document traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). Other activities proposed and carried out by the Tizu Valley Biodiversity Conservation and Livelihood Network (TVBCLN), a formal local CCA body, along with TERI and Titli Trust (an Indian NGO primarily focused on conservation and livelihoods in the Himalayas), were comprised of training the youths in biodiversity assessments and sustainable use of natural resources; preparing resource maps; generating awareness through sensitization campaigns; and promoting ecotourism as an alternative livelihood activity (see Fig. 5 and 6).

3.1 Conservation education and sensitization

Community engagement through consultation, conservation education, and public sensitization approaches was used to increase awareness of threats and integrated approaches at the community and stakeholder level. This was achieved through participatory planning, knowledge sharing, and capacity building. Around 30 sensitization campaigns were organized within the three pilot villages and on other community platforms like the local Ahuna festival, thus reaching out to a total of around 1,200 individuals directly, along with a positive impact on more than 10,000 individuals indirectly living in the vicinity of the project site. This resulted in many more villages urging a replication of these methods to manage their SEPLs, the latest being Chipoketa village, adjoining Kivikhu village, which is dominated by the Chakesang community. Also, scientific publications, popular articles, as well as websites (http://nagalandcca.org/ and http://gef-satoyama.net/) have helped to gain the attention of various stakeholders and boosted the engagement. In addition, exposure visits were undertaken for the community members to the neighboring states to showcase similar case studies, success stories and best practices with respect to community conservation.

3.2 Formation & formalization of joint Community-Conserved Areas

Due to the continuous and intense engagement with the communities, the three villages of Sukhai, Kivikhu and Ghukhuyi in Zunheboto district of Nagaland formally declared around a total of 939 hectares of biodiversity rich forest as community-conserved areas in respective villages, which are now being jointly managed by them (see Figure 1 and Table 1). However, apart from these CCAs, they have also banned hunting and destructive fishing across the entire landscape of their villages, covering 3,751 hectares of forests and rivers. In general, each CCA on average is about 25% of the total landscape area owned by the village, which is quite large. The CCAs were delineated and mapped and the boundaries were well-defined through demarcation, digitization and participatory mapping. This resulted in improved management of common resources. Also, a blanket ban on hunting wild animals and birds, a ban on fishing by use of explosives, chemicals and generators, strict prohibition of cutting of fire-wood/felling of trees, as well as a ban on collection of canes and other non-timber forest products for domestic and/or commercial purposes in the CCAs, have ensured conservation of large contiguous forest areas along with the unique endemic biodiversity they support.

3.3 Biodiversity assessments and preparation of People’s Biodiversity Registers (PBRs)

Regular biodiversity surveys in the designated CCAs found an increase in the diversity of birds, reptiles, butterflies and moths with the current checklist listing 222 species of birds, 31 reptiles, 11 amphibians, 200 species of butterflies and more than 200 species of moths. This diversity is very high in comparison to the nearby patches of forest, which do not receive protection and have been documented in the People’s Biodiversity Registers (PBRs) with local and scientific names. These PBRs prepared for the three villages of Sukhai, Kivikhu and Ghukhuyi document the folklore, traditional knowledge, ecology, biodiversity and cultural practices of the locals and help codify the oral knowledge of the communities.

Biodiversity surveys by local communities have strengthened interest in conservation. The youth share pictures of wildlife snapped by them on a “ WhatsApp group”. Sightings are recorded in field registers and this has created a conservation community amongst the youth. These sightings are also important for research and are uploaded on websites such as “eBird” and “Birds and Butterflies of India”. Regular assessments can provide information on seasonal variations, range extensions and changes in population abundance. The local people can use this knowledge to develop their own resource monitoring methods. Moreover, camera traps can indicate whether RET species such as the tragopan are still sighted in the area. These surveys, by documenting unique, rare or special fauna, have also acted as a catalyst to attract more outsiders to the area as ecotourists. Well-known local bird guides are now including Zunheboto in their travel itineraries. Given that unidentified species of bats and squirrels have been sighted through these surveys suggests that this documentation will be an invaluable resource base in the future and a contribution to scientific research in the area. A paper on the mandarin trinket snake has been jointly published with an active youth member.

3.4 Alternative livelihood opportunities through ecotourism

The training of youth in biodiversity assessments and sustainable use of natural resources, as well as the training and capacity building of local community members as nature guides for ecotourism, has resulted in enhanced livelihood opportunities with the steady flow of tourists that are visiting this area to spot ‘bird and butterfly specials’. These include birds like the Naga wren-babbler ( Spelaeornis chocolatinus ), Hodgson’s frogmouth ( Batrachostomus hodgsoni ), spot-breasted parrotbill ( Paradoxornis guttaticollis ) and the grey-headed parrotbill ( Paradoxornis gularis ), and butterflies like the endemic Naga Emperor ( Chitoria naga ) and Rufous Silverline ( Spindasis evansii ). Ecotourists also engage with the local communities to understand their traditions, culture, food and conservation activities. This has further motivated the communities, including those from neighboring villages, to take up conservation and protect their natural resources (see Fig. 7 and 10).

4. Discussion

An assessment by TERI to document the resilience status of pilot villages at the start of the project concluded that the communities were sensitive to the diversity of landscapes within their village. Due to traditional farming and allied conservation practices, they believed that the landscape has good resilience and can regenerate; however, the loss of biodiversity due to illicit tree felling and rampant hunting is irreversible. There was also a good understanding of ecosystem services provided by community areas mainly in the form of water and wild meat. However, the elders of the village also reported that the traditional taboos and beliefs that encouraged wise-use practices in the past may be becoming increasingly irrelevant, in part because of changes in religion, culture and globalisation. While in the short term these CCAs face problems of rule breaking particularly with regard to hunting, in the long-run threatening the very sanctity of these areas are the lost revenues from timber production. As populations grow, land prices rise and people move away from their villages, more private and clan owners of CCA land may want to manage their forests for timber, rather than for conservation.

One important lesson learned through this project is that if communities are well informed and empowered, they can take steps to protect their natural resources and use them judiciously. The project directly helped the communities to strengthen the age-old practice of conserving community forests through mobilization and building synergies. The project also responded to the critical needs of the pilot area by documenting the traditional knowledge and raising awareness on the impacts of anthropogenic activities on the biodiversity and ecosystem services of the CCAs, as well as the ripple effect on the socio-economic and cultural lifestyle of the Sema people. Again, the project through its effort to generate alternative livelihoods built the capacity of communities on ecotourism and is contributing to biodiversity conservation. The positive impacts of the project activities were evident in the second resilience assessment conducted by TERI at the end of the project. The communities reported increases in the protection of natural resources after the formation of jointly managed CCAs, and improvement in management of common resources. The elders were satisfied with the documentation of their traditional and cultural indigenous knowledge in the People’s Biodiversity Registers (PBRs), while the youth, women’s groups and the marginalized members of the community reported increases in their household income due to ecotourism. The protection of a stretch of Tizu River passing along the boundary of a CCA also resulted in an increase of fish-catch downstream.

Local communities are intimately dependent upon the resources provided by their SEPLs and are well aware of the many benefits they receive from their landscapes. However, over time traditional knowledge has eroded and the folklore and practices that supported the wise use of their landscapes are being lost. Nevertheless, the way people perceive certain elements of their landscapes has shifted after this project. In particular, the importance of stopping hunting to increase wildlife abundance is now well supported. The role of wildlife in promoting forest regeneration, and the interconnections of healthy rivers and fish abundance are clearly understood. Increasingly, though slowly, the people realise that forests and biodiversity can also provide economic benefits through livelihood alternatives like ecotourism. Their fast eroding awareness of the importance of healthy SEPLs to their lives and cultures that were once traditionally embedded in their beliefs and practices is now slowly reviving. These changing perceptions have been captured through the second assessment of the indicators of resilience which further underscores that local people now understand the value of banning hunting and fishing for the benefit of future generations.

This project is just the start of what we hope will be a movement for conservation in the State of Nagaland. To date, impacts of the project have been monitored based on indicators and a baseline developed at project initiation. The project has far exceeded our expectations. Since the project is for only two years, another objective was to ensure sustainability of the initiatives. In January 2019, the local communities independently organised a Chengu (Great Barbet) conservation festival which was a vibrant demonstration that the local people were well on their way to independently carrying out conservation.

Future monitoring in villages will be ensured by the Village Councils themselves. The Village Councils have set in place sets of resolutions, and those failing to comply are heavily fined. The local communities now patrol their forests and prevent both outsiders and people from their own villages from hunting and fishing. They also share pictures of those disobeying their rules on a WhatsApp group for quick action, and educate and motivate the people of other villages to eschew hunting. The Tizu Valley Network further supports education and sensitization and livelihood activities. Moreover, the government has taken notice of this initiative and has come forward to support it by developing the area into a Community Reserve under the Indian (Wildlife) Protection Act, for which limited funding is available.

The value of linking CCAs as a network so that they act as refuges for wildlife and enhance connectivity for wildlife movement has now been recognised by the Government of Nagaland. Enabling joint CCAs as formal institutional mechanisms that promote landscape conservation and facilitate nature-based livelihoods is soon to be supported through externally aided projects to strengthen forest and biodiversity management in the State. TERI has also developed a draft policy on CCAs as institutional frameworks for conservation in the State, which has been shared with the Government of Nagaland.

5. Conclusion

The case study of the Tizu Valley Biodiversity Conservation and Livelihood Network’s (TVBCLN) Community-Conserved Areas has yielded positive results in terms of sustainable use of biological resources by adopting long-term sustainability, enhanced governance and effective conservation of SEPLs. Up-scaling of activities initiated by the communities will involve the formalization and mainstreaming of a network of CCAs in the State which are at par with India’s Protected Area (PA) network in conjunction with the Nagaland Government and Forest Department. This will also require technique, finance and institutional support to encourage and sustain the practice of CCA formation and sustainable management. Given that 88.3% of forests are under the governance of the communities in Nagaland, the Community-Conserved Areas (CCAs) constitute the primary method for forest management and conservation of SEPLs in the State. The government needs to provide the policy, technology and the funding needed to allow these conservation groups to perform their role uninterrupted.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Conservation International (CI) Japan for supporting the project via a GEF-Satoyama grant. Special thanks to the Department of Forests, Ecology, Environment and Wildlife of Nagaland for their guidance and support. Special thanks to Sanjay Sondhi of Titli Trust for his invaluable support and help throughout the project. Thanks to Tshetsholo Naro for his support in the field.

Forest Survey of India (FSI) (2017), State of Forest Report, Forest Survey of India, Dehradun.

Hutton, JH 1921, The Sumi Nagas , Macmillan and Co. Limited, London.

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) 2009, Indigenous and community conserved areas: a bold new frontier for conservation , IUCN, Geneva, Switzerland, viewed 15 February 2019, < https://www.iucn.org/content/indigenous-and-community-conserved-areas-bold-new-frontier-conservation >.

Lkr, L & Martemjen 2014 ‘Biodiversity conservation ethos in Naga folklore and folksongs’, International Journal of Advanced Research , vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 1008-13.

Pathak, N & Hazarika, N 2012, ‘India: Community conservation at a crossroads’ in Protected Landscapes and Wild Biodiversity, eds N Dudley & S. Stolton, Volume 3 in the Values of Protected Landscapes and Seascapes Series, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Pathak, N (ed.) 2009, Community-Conserved Areas in India –A Directory , Kalpavriksh, Pune.

TERI 2015, Documentation of community conserved areas of Nagaland , The Energy and Resources Institute, New Delhi.

TERI 2017, A People’s Biodiversity Register of Kivikhu Village, Zunheboto, Nagaland , The Energy and Resources Institute, New Delhi.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A Case Study: Conservation Strategies Of Biodiversity In Konkan Region Of Coastal Maharashtra, India

The present article is based on the training cum workshop organized by Applied Environmental Research Foundation (AERF), Pune, India, based on field survey in March 2008. In the workshop some strategies for conservation of biodiversity has been developed in Konkan region of coastal Maharashtra, India and were assessed. (New York Science Journal. 2009;2(4):31-32). (ISSN: 1554-0200).

Related Papers

International Research Journal on Advanced Science Hub

Nikhil Agnihotri

anamika agarwal

India is one of the 34 Mega biodiversity hotspots of the world. It is home for threatened and endemic species that have immense ecological and commercial value. Due to increased human population and overexploitation of natural resources biodiversity is under threat worldwide. Threats to species are principally due to decline and fragmentation of their habitat. Biodiversity, as measured by the number of plant and vertebrate species, is greatest in the Western Ghats and North East in India.Biodiversity has several values such as economical, ecological, ethical, medicinal, aesthetical, social and many more. The present need of the hour is the sustainable use of biodiversity. Inventory only will identify the key issues of management of biodiversity which include a continuing process of searching and re-examining the early findings. Conservation of biodiversity is being done in the form of various legislations, the establishment of the protected area, Zoos and botanical gardens, gene Ban...

Photon e Book

Dr. Krishna K U M A R Yadav

Biodiversity, or biological diversity, is variety of all species on earth. It is the different plants, animals and micro-organisms, their genes, and the terrestrial, marine and freshwater ecosystems of which they are a part. Biodiversity is both essential for our existence and intrinsically valuable in its own right because biodiversity provides the fundamental building blocks for the many goods and services a healthy environment provides. These include things that are fundamental to our health, like clean air, fresh water and food products, as well as the many other products such as timber and fiber. Other, important services provided by our biodiversity include recreational, cultural and spiritual nourishment that maintain our personal and social wellbeing. Looking after our biodiversity is therefore an important task for all people. India is one of the 17th megadiverse countries, but it has suffered a rapid decline in biodiversity in last few decades. Despite efforts to manage threats and pressures to biodiversity in India, it is still in decline. This is an attempt to document the status and major threats to the biodiversity in the India, as well as deals with the various conservation strategies which is guiding our government, community, industries and scientists to manage and protect the plants, animals and ecosystems of India.

Biological Conservation

R J Ranjit Daniels

Kanika Ahuja

India woke up to the potential of its immense bio-heritage and took steps to safeguard it by enacting several laws including Biodiversity Act. This is the time to find innovative solutions for conserving biodiversity and to provide effectual revenue models for native populations instead of just passing laws which are good on paper but remain toothless. The onus of safeguarding biodiversity is not just on Government or indigenous communities but on all of us as this is our common heritage. Policies are implemented in true spirit only when there is widespread knowledge about them. This paper explains in brief the concepts of ownership of biodiversity, factors responsible for its loss, economic advantage, access and benefits sharing, legislative measures and suggests ways of conserving biodiversity.

Dr Leonard Polonsky thesis digitisation

Shonil Bhagwat

kanchan kumari

isara solutions

International Research Journal Commerce arts science

Remote sensing, a state of art technology has gained significance due to its capability to map and monitor compositional, structural and functional biodiversity. Remote sensing data provides a perspective on how ecosystems and species are being affected by the multiple disturbances. This paper presents consolidated information of earth observation based biodiversity research and conservation applications in India. Progress achieved for understanding essential biodiversity variables with reference to species populations, species traits, community composition, ecosystem function and ecosystem structure have been reviewed. Studies mostly focused on remote sensing based biodiversity indicators in understanding of land cover, forest cover, forest type, fragmentation, biological richness, carbon stocks, fires and protected area monitoring at multiple spatial and temporal scales.

Research Papers

Diversity of nature, with its bountiful flora and fauna is a source of beauty, enjoyment, understanding and knowledge-a foundation for human creativity and subject for study. Study of animal life is a fascinating subject to say the least and a challenge at best. India is very rich in biological diversity due to its unique biogeographic locations, diversified climatic conditions and enormous ecodiversity and geodiversity. India embraces three major biological realms, via, Indo-Malayan, Eurasian and Afro-tropical and is adorned with 10 biogeographic zone and 26 biotic provinces (Alfred, 1998). India possesses diversified ecosystem from snow clad high mountain ranges to sea coasts of all categories including desert and semi-arid regions, almost all types of forests, grass land, lakes and rivers, estuaries, lagoons, islands and ocean. The climate ranges from artic in the Himalayas to very hot in the thar desert of Rajasthan while annual rainfall varies from 100mm in the desert to 5000mm in the Cherrapunji hills. It is, therefore, quite inevitable that India having only 2 % of the World total landmass and harbours about 89,500 animal species comprising 7.28% of the world known animal species. Thus, India is recognizing as one of the 17-mega diversity countries of the world with four biodiversity Hot Spots, of 34 such sites identified throughout the globe. In fact our countries is very rich in term of not only species diversity but is blessed with an enormous variety and variability (genetic diversity) with in species along with the presence of a large number of endemic species.

Journal of Ecological Society

Vishwas Sawarkar

National wellbeing is dependent on the productivity of its lands. Productivity is central to the interestof natural ecosystems and the systems of farming. Water is essential for sustaining life, for ensuring foodsecurity as well as for effectively driving all development projects. Security of water is ensured by securenatural ecosystems centered on biological diversity. The terms productivity and biological diversity aresynonymous therefore it is essential for all processes and projects of development to internalize the securityof biological diversity/natural ecosystems. The principle at present however is almost non-existent in alldevelopment programmes because had it been so the forest and environmental clearances would not beconsidered loud and clear as hurdles to development. Western Ghats are one of the ecological hotspots of theworld. The northern Western Ghats have diverse forests, protected areas, ecologically sensitive areasdeclared under law, ecologically sensitive tehsils...

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

anita desale

BIODIVERSITY, CONSERVATION AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Principles and Practices with Asian Examples

Clement Tisdell

lead Key Note proceeding Book

laxman maharu ahire , M Ramesh Naik

Samit Ghosal

Advances in Forest Management under Global Change [Working Title]

Anand Narain Singh

Prof.(Dr.) Sobhan Kr. Mukherjee

Vinayak Patil

Aramde Fetene

Dr. Rajesh Gurjwar

Bitopan Sarma

rameshkumar gunasekeran

N. K. Agarwal

Krishna Upadhaya

SocioEconomic Challenges

Medani Bhandari

Udayan Borthakur

Ecology and …

Nick D Brown

International Journal for Research in Applied Science & Engineering Technology (IJRASET)

IJRASET Publication

Conservation …

Evariste Fongnzossie

Bharath Sundaram

Down To Earth

latha jishnu

Anil Markandya

International Journal of Zoology and Animal Biology

Dr.K.Sivachandrabose K

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Español (Spanish)

- Français (French)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Brasil (Portuguese)

- हिंदी (Hindi)

Mongabay Series: The Indian Forest Story

Forests of the islands: Andaman, Nicobar & Lakshadweep deal with development pressures

- Andaman and the Nicobar Islands, as also the Lakshadweep archipelago, both hundreds of kilometres away from mainland India, are battling pressures of climate change, seismic impacts, tourism and developmental activities.

- The 2019 Forest Survey of India report has said the forest cover in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands has increased by 0.78 sq. km. while the mangrove cover has decreased by one square kilometre, relative to their 2017 status report.

- In terms of diversity, density and growth, mangroves of Andaman and Nicobar Islands are best in the country. The Islands also house a diverse array of forest types.

- Any development planned for the Andaman, Nicobar and Lakshadweep islands must be sensitive to impacts on natural systems and should be undertaken based on genuine consultation with the island stakeholders.

They may be hundreds of kilometres away from the Indian mainland, but the rich forests and the biodiversity in the strategically important Andaman and the Nicobar Islands (ANI) face pressures similar to those on forests in the mainland. The condition of Lakshadweep islands, another island group of India, is no different.

Over the past few years, in light of growing naval capabilities of China, the Indian government has had a special focus on the development of ANI as the islands are at the entrance to the Malacca Strait, the world’s busiest shipping route. Now, coupled with tourism and climate change, the forests of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are facing immense pressure.

Andaman and Nicobar Islands comprise 572 islands with a total geographical area of about 8,249 square kilometres, 0.25 percent of the total geographical area of India. Of the 8,249 sq. km, over 80 percent of the land (6,742.78 sq. km.) is recorded as forest land, which includes nine national parks, 96 wildlife sanctuaries and one biosphere reserve.

These forests are important from the ecological point of view as they support luxuriant and rich vegetation with tropical hot and humid climate and abundant rains. The irregular and deeply indented coastline result in innumerable creeks, bays and estuaries which facilitate the development of rich, extensive and luxuriant growth of mangrove forests the archipelago, said mangrove ecologist P. Ragavan.

The recently released India State of Forest Report (ISFR) 2019 noted that nature has provided these islands with unique and varied flora and fauna and the surrounding seas are equally rich in marine biodiversity.

“Due to the geographic isolation of these islands, a large degree of endemism exists, which means that the ecosystems of these islands are vulnerable to disturbances. The forestry practices in these islands have undergone significant changes in the last more than 125 years of scientific forestry, influenced by major policy changes and socioeconomic situations. The current focus of forest management in the islands is towards biodiversity conservation along with sustainable use of forest produce for local inhabitants, to protect the environment for future generations,” said the report.

It also noted that about 2,200 varieties of plants have been recorded in the Islands, out of which 200 are endemic (found nowhere else in the world) and 1,300 do not occur in mainland India.

The importance of forests in this region can be ascertained from their diversity. While south Andamans have a profuse growth of mostly ferns and orchids, the middle and north Andamans are characterised by moist deciduous and wet evergreen forests. “The evergreen forests are dominant in the Central & Southern Islands of the Nicobar group. The moist deciduous forests are common in the Andamans, they are almost absent in the Nicobar Islands. Grasslands occur only in the Nicobars,” noted the report.

The Forest Survey of India, which comes out with the ISFR every two years, has also done an estimation of the dependence of people living in the villages close to the forest for fuelwood, fodder, small timber and bamboo. For Andaman & Nicobar Islands, the estimated quantities of the fuelwood are 22,038 tonnes, fodder is 83,405 tonnes and 3,737 tonnes of bamboo.

Ragavan said in terms of diversity, density and growth, mangroves of ANI are best in the country, adding that periodical information on the extent and status of mangroves in the islands is imperative not only to improve our understanding of phytogeography but also for better management and conservation.

The mangrove cover of ANI consists of 38 true mangrove species belonging to 13 families and 19 genera, according to a study by Ragavan, post-doctoral fellow, Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad.

Of the 38 mangrove species identified in the study, five species are globally considered important with respect to their conservation importance (IUCN 2011). While Sonneratia griffithii is critically endangered, Excoecaria indica is data deficient. The remaining three species, viz. Brownlowia tersa, Phoenix paludosa and Sonneratia ovata are categorized as near threatened.

Extensive floristic surveys in recent times led to a better understanding of the extended distribution of few extant mangrove species and the discovery of new entities from ANI, Ragavan noted.

Significant findings are four new records for India ( Sonneratia lanceolata, S. ovata, S. urama, and S. gulngai ), two new distribution records for the Andaman and Nicobar Islands ( Excoecaria indica and Rhizophora annamalayana ), extended distribution of Rhizophora stylosa, Scyphiphora hydrophyllacea, Xylocarpus granatum from Nicobar Islands.

“And the rediscovery of three species ( Sonneratia griffithii, Brownlowia tersa, and Acanthus volubilis ) after a gap of 90 years,” explained Ragavan.

Pressure on Andaman’s forest and mangroves

Compared to the ISFR 2017, the forest cover in the region has increased by 0.78 sq. km. while the mangrove cover has decreased by one square kilometre . Experts are, however, worried about an increase in the anthropogenic activities in the region and their impact.

Subha Chakraborty, who is from the department of architecture, town and regional planning of the Indian Institute of Engineering Science And Technology , Shibpur (West Bengal), explained that there is a high human impact on the natural resources, including the mangroves, on the islands.

“The archipelago saw a wave of migration of refugees following Independence (in 1947) till 1971 from the mainland, including from Bangladesh. The settlers didn’t have knowledge of the islands’ natural resources; they were using them for their own survival and sustainability,” Chakraborty told Mongabay-India.

He stressed that their studies have found that the Diglipur region in the Andaman and Nicobar islands is most vulnerable. “Both natural and man-made impacts are high in Diglipur. There are two major degradation hotspots identified for 2030 and 2050, and these are Mayabunder and Diglipur region. The major threats of these regions are population growth and the influence of climate change,” Chakraborty said.

“All of the Andaman and Nicobar islands are in the most severe seismic zone. Mangroves are degrading in parts and in others, they are increasing. So the islands are very complex in that sense,” he said.

Based on his research, Chakraborty said that in the last 40 years, around 45-47 percent of the mangrove forests were destroyed in the Andaman Islands and the main reason is the human impact (which was very high between 1950 to 1980) coupled with climate change and seismic effects.

“The human footprint is mainly attributed to the migration during that period. As for seismic impacts, every 72 to 96 hours there’s one earthquake. In 2019, 138 tremors hit the island according to USGS data. The major seismic impact was due to the 2004 earthquake and subsequent tsunami,” he added.

The earthquake uplifted the northern Andaman coast, resulting in a drastic reduction of tidal water influx into the adjoining mangrove-laden mudflats.

A 2020 study that assessed the impact of coastal upliftment on the northern Andaman mangroves based on satellite data analysis of the period from 2003 to 2019 reports a loss of 6500 hectares of northern Andaman mangroves. Superseding initial reports that documented 60 -70 percent mangrove cover loss in the Nicobar islands, a 2018 study revealed that in fact 97 percent of mangrove cover of the islands was razed due to the 2004 event.

His concerns about thousands of hectares of forest land making way for settlers are not ill-founded. It has been estimated that between 1869-1984, over 232,000 hectares of forests were cleared due to plantation, setting of towns, agriculture, fuelwood and encroachments.

Read more: Sentinelese in shadows: A lesson in letting live The mysterious karstland forests of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands

Lakshadweep under ecological stress

Located in the Arabian Sea, off the western coast of India, Lakshadweep is a group of 36 islands and is the smallest union territory of India. Its total geographical area is only 30 sq. km and it has a total population of only 0.064 million.

According to the ISFR 2019 , the forest cover in the union territory is 27.10 sq. km. which is 90.33 percent of its geographical area. About 82 percent of the land mass is covered by privately owned coconut plantations.

It has a vast lagoon of 4,200 sq. km. with sandy beaches and abundance of marine fauna. The livelihood of inhabitants of Lakshadweep is dependent on fishery and tourism but one of the most serious concern the region faces is coastal erosion.

“Lakshwadeep is a densely populated area unlike the general perception that it is a deserted paradise. The biggest stress that the whole ecological system of the area faces is climate change. In maximum, two-three generations it will become inhabitable. One other major concern is the large scale commercial fishing taking place which is emptying the fish stocks. In terms of forests, it is largely coconut plantations,” Rohan Arthur, a senior scientist and founding trustee of the Nature Conservation Foundation, told Mongabay-India.

Unsustainable tourism and development

The Prime Minister Narendra Modi led central government has been focusing on improving tourism facilities in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands for some years now, with the intention of turning it into a world-class tourism destination.

Following the intent, the Indian government’s policy think tank, the NITI Aayog, has been working with different stakeholders to achieve the goal. In January 2020 , India’s Home Minister Amit Shah, chaired a meeting of the Island Development Agency (IDA) wherein the government reviewed the progress made towards the development of islands.

An official statement after the meeting noted that model tourism projects — both land-based and water villas — were planned and bids have been invited for private sector participation.

According to the statement, “As a unique initiative, to spur investment, it was decided to obtain clearances for implementation of the planned projects up-front. All necessary clearances would be in place before bids finalization. Environment and coastal regulation zone (CRZ) clearances have already been obtained for four exemplary tourism projects of Andaman & Nicobar Islands.”

“The proposed airports in Great Nicobar Island of Andaman & Nicobar and Minicoy Island of Lakshadweep would catalyse the development process in the region,” it added.

Conservationists and experts advise caution

Some local experts of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, who did not wish to be named for fear of being targeted, said even though the government is going full throttle to develop tourism facilities in the islands, there are not many takers. Additionally, the encroachment of forests and wetlands is increasing in the region, they say.

Sejal Worah, who is the programme director with the conservation group WWF India, said India’s island chains of Andaman and Nicobar and Lakshadweep are ecologically and socio-culturally unique and distinct from each other.

“What they do share is the fragility and vulnerability of their ecosystems and the people who reside on them. The livelihoods and culture of people living on the islands are intrinsically linked to the ocean and dependent on the health of marine systems. Any development planned for the Andaman & Nicobar and Lakshadweep islands must, therefore, be sensitive to impacts on natural systems and should be undertaken based on genuine consultation with the island stakeholders,” Worah told Mongabay-India.

Manish Chandi, a human ecologist and senior fellow with the Andaman Nicobar Environment Team, said the infrastructure or tourism projects that are being discussed in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are not new.

“They have been part of the discussion in one form or the other from 20-30 years. The difference compared to the past is the way the present administration is moving forward on them overriding concerns and consultation with the local experts and stakeholders. While they may seem as economic development ventures, to whose larger benefit is very questionable. When seen in a macro perspective the rural economy in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands is generally stagnant and stratified not just in the hinterland but even in villages beyond Port Blair,” Chandi told Mongabay-India.

“Apart from the huge dependence on government services, and some involvement, rather than much local investment in tourism, the local population needs much more than just large infrastructural projects for collective benefits. There needs to be a rethink on how not just money can be generated, but rather how local communities can benefit beyond just monetary value. In general, the projects which have been repeatedly discussed and put in cold storage by the earlier administrations for precisely these concerns and ecological stability are now being revived and there is a lot of movement on that front,” said Chandi.

“They have been part of the discussion in one form or the other from 20-30 years. The difference compared to the past is the way the present administration is moving forward on them without any consultation with the local experts and stakeholders. In general, the projects which have been repeatedly discussed and put in cold storage by the earlier administrations are now being revived and there is a lot of movement on that front,” Chandi told Mongabay-India.

Additionally, Ragavan said: “In ANI extensive efforts have been taken to improve the degraded/tsunami impacted areas by forest department through plantation efforts. However, no species-specific efforts have been taken to improve the population of rare/threatened mangroves species.”

Banner image: The mangroves of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Photo by P. Ragavan.

Special series

Wetland champions.

- [Commentary] Wetland champions: Promise from the grassroots

- The story of Jakkur lake sets an example for inclusive rejuvenation projects

- Welcome to Tsomgo lake: Please don’t litter

- Managing waste to save the wetlands of Himachal Pradesh

Environment And Health

- As cities become megacities, their lanes are losing green cover

- Marine plastic pollution is not just a waste problem; reducing production is needed too

- Stitching sustainability amidst climate change challenges

- Gujarat bans exotic Conocarpus tree amid health and environment hazard

Almost Famous Species

- Study finds leopard cats and red foxes cohabit regions in the Western Himalayas

- Civet latrines in the shade puzzle researchers

- Small cats’ ecology review flags declining conservation status

- [Explainer] How are species named?

- [Video] Flowers of worship sow seeds of sustainability

- Rising above the waters with musk melon

- Saving India’s wild ‘unicorns’

- Crafting a sustainable future for artisans using bamboo

India's Iconic Landscapes

- Unchecked shrimp farming transforms land use in the Sundarbans

- [Commentary] Complexities of freshwater availability and tourism growth in Lakshadweep

- Majuli’s shrinking wetlands and their fight for survival

Beyond Protected Areas

- The hispid hare’s habitat in Himalayan grasslands is shrinking fast

- What’s on the menu? Understanding the diverse diet of fishing cats