Social and Environmental Responsibility Essay

Difference Between Corporate Social And Environmental Responsibility

Corporate social and environmental responsibility The term corporate social responsibility (CSR) appears for the first time in early 1970. Since then, it continues to develop and have different definitions and perceptions among private and government sector, and civil organizations. Corporate responsibly in relation to internal stakeholders and shareholders on local and national level, as well as, performance in serving the society and global community are the most common perspectives accepted by monument and individuals. “The first perspective includes ensuring good corporate governance, product responsibility, employment conditions, workers’ rights, training and education. The second includes corporate compliance with relevant legislation, and the company’s responsibility as a taxpayer, ensuring that the state can function effectively. The third perspective is multi-layered and may involve the company’s relations with the people and environment in the communities in which it operates, and those to which it exports” (Mazurkiewicz, 2004). Additionally, the protection of environmental resources and its implementation in CSR is…

Apple's Accountability Case Study

Apple’s supplier responsibility is based on the principles of accountability and improvement for the company and its suppliers, which are core business and operational objectives. The principles of accountability and improvement underlying the company’s supplier responsibility are major objectives because of the need to ensure safe and ethical working conditions as well as compliance with various regulations in the global business environment. This is primarily because the company increasingly…

Homer Dixon Argumentative Essay

have one responsibility, and that is to make as much money as possible (Friedman, 33). As the heads in charge of business are given a set of goals to accomplish by the owners, and most of the times the goal is to only increase profits(Friedman, 33). However, being the social animals there are social responsibilities of humans, which they must carry out independently, not involving the business (Friedman, 33). As per Friedman, “A corporation is an artificial person and may have artificial…

New Belgium Brewing Company Case Study

environmentally and socially. It is true that alcoholic beverages can be harmful to the health of the consumers and there are many people believe that a company sells alcoholic beverages is not socially responsible. However, just because the product that they sell might have a harmful effect to the consumers does not make the company automatically irresponsible. Also, the company is promoting responsible drinking and discouraging the sale of alcohol to minors. Moreover, the company is doing a…

Ups Case Analysis Essay

Bree Barnes Professor Barnes BUSN 105 2/12/2017 Case Analysis 1.UPS’s approach toward sustainability impact the triple bottom line by affecting its social and finical performance. UPS doesn’t focus much on the environmental side of it. It really digs deep on the social side of things such as philanthropic, strengths, relationships, building a productive partnership, etc. It could potentially affect them because the things they are doing now might not meet the needs or apply to future generations…

Home Depot Social Responsibility Study

The attributes of the stakeholder can be considered in their power,in their legitimacy & urgency. They possess power as they refuse to shop at a firm that isn’t environmentally responsible, so this compels Home Depot to be endorsed by the Forest Stewardship Council & pushes them to be ‘honest’ as far as their environmental practices are concerned. The stakeholders possess legitimacy as they want to ensure that its appearance of being environmentally friendly isn’t a sham, so they push them to…

New Belgium Brewing Case Study

1. What environmental issues does the New Belgium Brewing Company work to address? How has NBB taken a strategic approach to addressing these issues? Why do you think the company has taken such a strong stance toward sustainability? New Belgium Brewing works to target three environmental issues, cost-efficient energy-saving alternatives for conducting its business and reducing its impact on the environment, recycling, creative reuse strategies, and green building techniques. To manage these…

Business Ethics Of Qantas: Corporate Social Responsibility

Social Performance Corporate social responsibility is the the obligation of an entity for their actions to align with the interest of their stakeholders, the environment and society in general (Birt 2014). Qantas has eight key business principles and group policies in order to maintain a socially responsible business. These policies have been board approved and are non-negotiable. They are presented in a mandatory training program to ensure they are understood and reliably implemented by all…

What Is The Impact On Carbon Footprint Within The Environment

order to accomplish this objective, it is imperative that an action plan is implemented into the organization in order to improve its corporate social responsibility efforts. To maintain its corporate social responsibility, the organization must also take environmental efforts that is not ethical morally satisfying to the public’s eye. The following action plan outlines were major issues that is associated with stakeholders as well as the action of the company. This is an attempt to improve…

Liquid Telecom Corporate Social Responsibility Essay

Liquid Telecom Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy Proposal ‘Lasting and effective answers can only be found if business-working together with other actors including government and civil society-are fully engaged,’ Kofi Annan. All the actions that we make today will affect everything and everyone in future generations. Therefore as part of society it is also then in the interest of all businesses to contribute in addressing social, economical and environmental issues faced by society. A…

Related Topics:

- Business ethics

- Chasing Lights

- Corporate social responsibility

- Corporation

- Environment

- Environmentalism

- Indigenous Australians

- Natural environment

- New Belgium Brewing Company

- Occupational safety and health

- Social responsibility

- Socially responsible investing

- Stakeholder

- Strategic management

- Sustainability

- Sustainable development

Popular Topics:

- Lady Macbeth Essay

- Corruption in South Africa Essay

- My Childhood Memories Essay

- Antigone Essay

- Conservation of Trees Essay

- The Great Depression Essay

- The Kite Runner Essay

- First Day of School Essay

- Good Habits Essay

- Persuasive Essay About Love

- Family Background Essay

- Freedom of Expression Essay

- Essay About Senior High School

- How to Write a Descriptive Essay About a Place

- Philosophy of Education Essay

- Role of Youth in Nation Building Essay

- English Speech Essay

- How to Write a Descriptive Essay

- Gattaca Essay

- Personality Essay

- Digital Technology Essay

- Eating Disorders Essay

- Cyber Crime Essay

- Essay of Love

- Marijuana Essay

Ready To Get Started?

- Create Flashcards

- Mobile apps

- Cookie Settings

Social and Environmental Responsibility Essay

Corporate social responsibility - 1812 Words

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is increasingly discussed and recognized as essential as to existence of the corporations. In this contemporary world corporations are expected to report not only their accounting profits but also their social and environmental responsibility. Corporate social responsibility reporting is an emerging field at the global level, which is on its way of gaining its position as a mandatory business practice. However many of the

Words: 1812 - Pages: 8

The Importance Of Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate social responsibility Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a business approach that contributes to sustainable development by delivering economic, social and environmental benefits for all stakeholders. CSR is a idea with many definition and practices. The way it is understand and implement differs greatly for each company and country. Moreover, CSR is a very broad concept that address many and a variety of topics such as human rights, corporate governance, health and safety, environmental

Words: 1034 - Pages: 5

Marketing: Social Responsibility and Qantas Public Report

Introduction 2 2. Corporate social responsibility and ethical behaviour 2 3.1 social responsibility 2 3.2 environment responsibility 3 3. Reference

Words: 950 - Pages: 4

Corporate Social Responsibility - 1080 Words

Corporate Social Responsibility: What is it? In essence, corporate responsibility entails the operation of a business in such a way that it (business owners) bears responsibility – or accounts – for the environmental or social impacts that arise as a result of its creation. Socially responsible businesses not only develop policies that incorporate responsible “Do's and Don’ts” into their everyday business operations, they also report on the progress made toward the implementation of these practices

Words: 1080 - Pages: 5

coca colA - 517 Words

Apple has done a good job with their social and ethical responsibilities. After the teen suicides at Chinese manufacturer Foxconn last year, Apple has investigated and reported child labor violation, toxic conditions, and other violations of their code of ethics. Using the Pyramid of Social Responsibility, I think it’s safe to say that Apple's actions against unethical and illegal conduct is to better society. Apple has done a tremendous job concerning environmental issues that range from toxic material

Words: 517 - Pages: 3

CSR Report APRIL6 Yousef

Corporate Social Responsibility 3 Archie Carroll’s Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility 4 Advantages of Corporate Social Responsibility 4 Innovation 5 Cost Savings 5 Long-Term Thinking 5 Public Image and Brand Differentiation 5 Employee Engagement 5 Arguments against Corporate Social Responsibility 6 Misalignment with Profit Maximization 6 Accountability and Green-washing 6 Business Mandate and Skill Set 7 Issue Statement 7 Stakeholders 7 Aritiza’s Current CSR Strategy 8 The Social and Environmental

Words: 8336 - Pages: 34

Stakeholder and Social Responsibility - 2111 Words

groups themselves. Some of these requirements are also illustrated in Table 2.3. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) Strongly related to the stakeholder perspective of operations performance is that of corporate social responsibility (generally known as CSR). According to the UK government’s definition, ‘CSR is essentially about how business takes account of its economic, social and environmental impacts in the way it operates – maximizing the benefits and minimizing the downsides. . . .

Words: 2111 - Pages: 9

Howard R. Bowen's Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate Social Responsibility refers to the responsibilities that a company has towards society. CSR can be described as decision making by a business that is linked to the ethical values and respect for individuals, society and the environment, as well as compliance with legal requirement. CSR is based on a concept that a company is a citizen of the society in which it exist and operates. The book “Social Responsibilities of the Businessman” by Howard R. Bowen started the discussion of CSR. Bowen

Words: 1097 - Pages: 5

Csr Critical Essay - 1943 Words

An Examination on Social Performance of BMW AG Corporate Social Responsibility can be defined as performances of businesses in completing good practices and standards to accomplish positive and sustainable results towards business, environment and society (CSR Singapore Compact 2005). Implementation of corporate social responsibility concept within the businesses means the businesses will always try their best to give positive outcomes to the society, which give satisfaction to the people and

Words: 1943 - Pages: 8

Corporate Social Responsibility Presentation Recovered

Corporate Social Responsibility Business School ACCO1084 BY: DAWOOD, DOINA, MUNEERA AND CHANDNI Objectives 1. Define the CSR from different visions; 2. Describe and then proceed to evaluate strengths and weaknesses of CSR; 3. Outline what social obligations and responsibilities should organizations have, providing practical examples; 4. Explain whether companies can satisfy both profit and social needs and obligations. CSR – What is this? Mass layouts and record profits Managers Salary Climate

Words: 1259 - Pages: 6

Ethical: Business Ethics and Ethical Codes

conduct of individuals and entire organisations. Business ethics can arise in relation to human right, corruption, economic growth, investment, corporate governance as well as environmental protection. The behaviours of business may violate with the broader community, human right of their employees and have serious economic and social effects. In the long run, ethical business methods are more profitable than unethical business methods. Unethical methods could seriously incur negative business reputation

Words: 692 - Pages: 3

Low-cost Carrier and Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate Social Responsibility And Ryanair Business Essay This section of the report analyses the reputation of Ryanair as regards corporate social responsibility (CSR) issues in the environment in which the airline operates and also the role of the operation function of Ryanair in addressing CSR issues. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) CSR is the serious consideration of a company’s impact over the company’s environment. (CSR) refers to the responsibility that business organizations have

Words: 1193 - Pages: 5

Sony Group - 658 Words

Sony’s Views on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) The core responsibility of the Sony Group to society is to pursue the enhancement of corporate value through innovation and sound business practices. The Sony Group recognizes that its businesses have direct and indirect impact on the societies in which it operates. Sound business practices require that business decisions give due consideration to the interests of Sony stakeholders, including shareholders, customers, employees, suppliers

Words: 658 - Pages: 3

Corporate Social Responsibility - 747 Words

Corporate Social Responsibility Corporate social responsibility is a corporate incentive to assess the company’s effect on the environment and social welfare and take responsibility for the impact it makes. Corporate social responsible corporations go above the required regulations and want to improve and better the environment or world. This kind of responsibility includes possibly adding extra costs to create positive social and environmental change. Businesses that practice corporate social responsibility

Words: 747 - Pages: 3

Sustainability and Packaging - 4990 Words

9216 8074 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The packaging industry has been under pressure for more than 20 years to reduce the environmental impacts of its products. Despite significant investments in litter reduction and kerbside recycling programs over that period, packaging has maintained its high profile in the public discourse on environmental issues. Specific concerns about packaging are rarely articulated beyond those of waste and litter, but seem to step from deeper unease within

Words: 4990 - Pages: 20

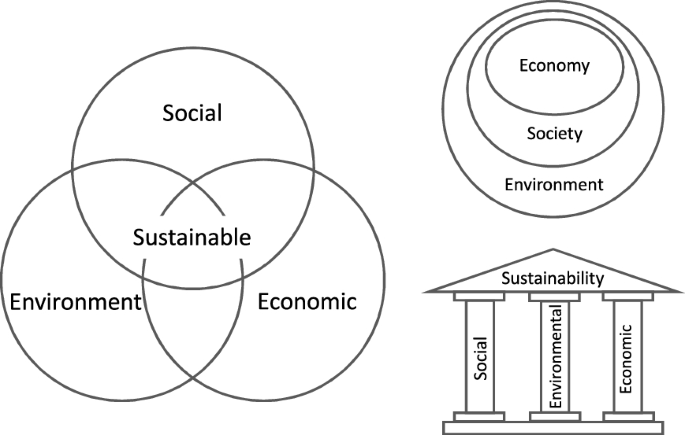

Triple Bottom Line Strategy

Our triple bottom line strategy plans to address factors concerning economic, social, and environmental circumstances. These three key factors are essential in our efforts of striving for long-term financial performance. We are committed to uphold transparent economic, social, and environmental policies that will continually improve our performance. Our business model will always run through every aspect of our business and our products lifecycle. To assure the highest possible

Words: 336 - Pages: 2

Contemporary issues in acounting - 1540 Words

assignment Use a theoretical framework of your choice to explain or predict the corporate social reporting (CSR) practices of five ASX listed companies in Australia and 5 listed companies in another country. Your analysis of CSR practices will be based on an examination of the most recent general purpose financial reports of the relevant companies. 1.1 Introduction This essay endeavours to explain the corporate social reporting practices and the motivations behind such practices of 5 predominant software

Words: 1540 - Pages: 7

Ethics Final Assignment 2 Social Corp

Table of contents Introduction 3 Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) 4 CSR Stakeholders 5 CSR Importance 6 CSR Policies adopted by Robert Bosch GmbH & General Motors Company 7 Robert Bosch GmbH……..……….……………………………………..…….…………7 General Motors Company LLC (GM)……………………….……………….….…..…8 CSR practices at Bosch…………..…………….…………………….……….……..…...8 CSR practices at GM…..………….…………………….…………………….………..9 Discussion…………………………………………..………………...…………..…...…10 Successful CSR Implementation and its potential benefits……

Words: 3758 - Pages: 16

Business Ethic - 846 Words

high-end outdoor clothing. The company is a member of several environmental movements. It was founded by Yvon Chouinard in 1972. Patagonia is a major contributor to environmental groups. Patagonia commits 1% of their total sales or 10% of their profit, whichever is more, to environmental groups. Since 1985, when the program was first started, Patagonia has donated $46 million in cash and in-kind donations to domestic and international grassroots environmental groups making a difference in their local communities

Words: 846 - Pages: 4

Corporate Social Responsibility and Its Role in Community Development: An International Perspective

CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY AND ITS ROLE IN COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT: AN INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE Maimunah ISMAIL• Abstract Corporate social responsibility (CSR) refers to strategies corporations or firms conduct their business in a way that is ethical, society friendly and beneficial to community in terms of development. This article analyses the meaning of CSR based on some theories available in literature. It is argued that three theories namely utilitarian, managerial and relational theories

Words: 6831 - Pages: 28

cpa SER - 3119 Words

Caroline Chaffer & Jill Webb_____________ Essay Title: The Benefits of Social and Environmental Reports and The Usefulness to Users_ Word Count: ____2837________ The Benefits of Social and Environmental Reports and The Usefulness to Users Abstract The increasing emphasis on environment result in a growing number of companies voluntary provide social and environmental reports. This paper brief evaluate the benefits of SERs, from users' perspective

Words: 3119 - Pages: 13

Home Depot Corporate Social Responsibility

Introduction Corporate Responsibility In the United States, social responsibility defines the organization's ability to impart cultural values and traditions that can either have a positive or negative impact on stakeholders. Corporate social responsibility means that the organization is accountable for its own actions that affect people, community, and environment which in turn gives aid and protect its stakeholders when making a business decision (Post, Lawrence & Weber, 2002). Firms engage

Words: 1111 - Pages: 5

Accounting Theory and Practice - 2215 Words

years have saw that listed firms, especially the large organisations, voluntarily disclose their Social and Environmental issues in their annual reports. As a result, a question was come up with by researchers: why managers would choose to undertake the voluntary activities? Although there is no consensus being reached about what perspective theories should be used to explain the Social and Environmental Accounting, and moreover critique voices are from the works of Marx or by the deep-green or feminist

Words: 2215 - Pages: 9

Social Responsibility In New Belgium

the home of New Belgium since the beginning in 1991(New Belgium). Social/environmental responsibility is the cornerstone of the company’s strategic focus. The company wanted to make sure its environmental stewardship, pioneer thinking on management, and broadly sharing equity spoke for the company (Eng, 2014).New Belgium’s focus on social responsibility does provide a key competitive advantage for the company. Social responsibility can be split into four categories; economic, legal, ethical, and voluntary

Words: 255 - Pages: 2

Studying: Corporate Social Responsibility and Csr

Corporate Social Responsibility is important The importance of CSR is increasing in a world strongly influenced by corporate trends and decisions. Corporate social responsibility refers to a company’s policy of protecting consumers, employees, and the environment in addition to its own bottom line. The activities of large corporations often have a far-reaching impact on the environment and in the lives of the people involved with them as consumers or employees. Despite this, some multinational

Words: 663 - Pages: 3

A Small Number Of Innovative And Entrepreneurial Companies And Their Aspiration For Social Change Thedriver Business Repositioning Is To Transform The Economic Success Of The Society As Well As The Best Throughtheir Products

Introduction : 2 Social responsibility : 3 Maritime New Zealand: 5 The Triple Bottom Line theory 8 Malcom Brands : 10 Conclusion : 13 Introduction : A small number of innovative and entrepreneurial companies and their aspiration for social change thedriver business repositioning is to transform the economic success of the society as well as the best throughtheir products. based on some of the faces of this report and business models (CSR-driven) firmsand looks at their corporate social responsibility-driven

Words: 4871 - Pages: 20

Csr Report on Tesco Plc

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) 2 Definition of CSR 2 Development of CSR 2 Approaches to CSR 2 Business Benefits of CSR 3 Critical Analysis of CSR 3 Factors influencing CSR 4 The Business Case for CSR 6 TESCO PLC 8 Tesco and Corporate Social Responsibility 8 Environment 8 Community 9 Suppliers 9 People / Employees 10 Government / Regulators 10 How Tesco manages their Corporate Responsibility (CR) 10 Conclusion 10 Bibliography 13 Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Definition

Words: 3418 - Pages: 14

Case Study 4 - 384 Words

employees and suppliers as stakeholders, but also considers the “earth” as a stakeholder as well. Their commitments to environmental issues are second to none in the apparel industry. It’s not everyday that you hear about a company giving its employees a week’s pay to volunteer in their communities. These days, most companies have policies for sustainability and corporate social responsibilities (CSR), but I think that Timberland actually lives it. Question 2 A) Green products sell. Timberland’s

Words: 384 - Pages: 2

Ethics and Responsibility - 881 Words

Ethics and Social Responsibility Successful companies have well established code of ethics. Members of an organization with high ethical standards are held to these standards, including the decision makers responsible for making strategic plans that affect the organization and its surrounding communities. Maximizing shareholder wealth should not be the only priority when developing strategic plans. However, an organization will need to generate revenues to be profitable and successful. Ethics and

Words: 881 - Pages: 4

Human Resources - 1582 Words

MGMT 4125-01-HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT | Social Responsibility within the NBA | Instructor: Carolyn Brown | By: Montilia Tripp 9/21/2012 | Ever since I was a kid, I have taken a liking to the National Basketball Association better known as the NBA. Like millions of other kids around the world, the NBA caught my attention because of its larger than life athletes. Some of whom are the best athletes on the planet. I wanted to be just like those athletes, and the athletes that I have

Words: 1582 - Pages: 7

All Social and Environmental Responsibility Essays:

- McEthics in Europe and Asia: should McDonald’s extend its response to ethical criticism in Europe?

- Ethical Investment Report on Westpac

- Corporate Social Responsibility and Csr

- Ethics: Coffee and Starbucks - 2002 Words

- Corporate Social Responsibility: Sustainable Responsible Business Or Sustainable Responsible Business

- Launching Pollution Permit Market In China

- Case Study Coca-Cola

- Institutional Theory Of Corporate Social Responsibility

- Oxford Plastics Company - 2660 Words

- Cocacola Nike Case - 972 Words

- Csr Toyota - 1780 Words

- MANAGEMENT ESSAY 666 - 2310 Words

- Sustainable Apparel Coalition: Environmental, Social And Labor Impacts

- strategy management 2 companies4

- Csr Nestle Case Study

- Social Responsibility and Bp - 322 Words

- Responsible Business report 1

- Presentation Chapter 10 - 1017 Words

- Research Methods For Managers - 2449 Words

- Rewarding social responsibility at the top

- Business Evnironment Responsbility Jou

- The Structural Behavioral And Organizat - 951 Words

- Culture: Corporate Social Responsibility

- final paper 685 CSR

- Poverty and Pollution - 1184 Words

- Ethics: Ethics and Social Responsibility

- BU354 Textbook Notes - Chapter 1

- Csr: Corporate Social Responsibility and Csr

- The Body Shop - 1617 Words

- Impact Of Business Ethics - 1626 Words

- Student: Environment and Green Business

- Ethics - British Gas - 1402 Words

- Global Reporting Guidelines (G2) Guideline

- Ben & Jerry Case Analysis

- Ethics and the Consumer - 2475 Words

- BUS 100 Assignmet 2

- Case Study 1 - 636 Words

- Corporate Social Responsibility and Profits

- mr liam birtwsitle - 2848 Words

- Csr Social Responsibility - 1269 Words

- Social Responsibility - 324 Words

- task 1 - 504 Words

- 515531 - 3900 Words

- Sustainable Business Assigment XINGYUN QIAN

- The Influence Of Coal - 1465 Words

- Human Rights and Anz - 1711 Words

- Ben & Jerry's - 642 Words

- Sustainability at Santander - 862 Words

- Dannon Final - 524 Words

- Advantages of Strategic Planning - 2109 Words

- Business And Society Assignment 1

- Outsourcing in India - 1580 Words

- New Balance: Footwear and Apparel Business

- Natural Environment and Nbb - 1529 Words

- E476 Paper - 3820 Words

- Importance Of Reverse Logistics - 991 Words

- Sony - 1151 Words

- LETTER Assignment - 468 Words

- Social Performance - 1304 Words

- operation management - 1338 Words

- Csr: Corporate Social Responsibility

- Fortis Inc - 3537 Words

- Arguments for and Against Corporate Social Responsibility

- Myer Case Study - 667 Words

- Case Study - 670 Words

- Green Washing Critique - 885 Words

- Corporate Social Responsibility - 552 Words

- evaluating report - 1008 Words

- Ge Case Study - 1447 Words

- Report the Role of Accounting in Organizations and Society

- Research: Sociology and Social Work Values

- Green Barrier to China's Export

- Social Determinants Of Health Essay

- Green Criminology Research Paper

- Globalization: A Study Of Business Ethics In Business

- Ethics in International Business - 2965 Words

- Woolworths Essay - 766 Words

- Business Environment - 4616 Words

- Assignment 2 - 1762 Words

- Corporate Social Responsibility - 431 Words

- Asign: Natural Environment and Sustainability

- Case: Chester & Wayne - 18757 Words

- Corporate Social Responsibility - 1684 Words

- Proposal: Industrial Revolution and Relevant Course Themes

- UNIT 400 UNDERSTANDING ORGANISATIONS

- Chapt 4 lecture notes

- mr essay - 644 Words

- Case: Amanco - 7655 Words

- External forces and Trends 1

- Volkswagen Marketing Strategy - 1171 Words

- Social Responsibility - 7367 Words

- The Role of Environment in Walmart's Marketing Decisions

- Exam 1 study guide

- Public Relations and Promotional Writing

- Riddells Creek Landcare - 2290 Words

- Business Ethics and Csr in the Context of Samsung

- Business Ethics Analysis - 4874 Words

- We own the night - 4799 Words

- Advanced Accounting Theory Project

- New Belgium Brewing Case Study

- Scotia Bank - 292 Words

- business ethics - 2189 Words

- Corporations and Corporate Social Responsiblities

- Accuform Case Study - 2155 Words

- Vodacom Vs Stakeholders - 1713 Words

- Ch2 Outline - 2360 Words

- Supply chain mamagement - 2234 Words

- School: Corporate Social Responsibility and Nike

- Mc Donalds - 404 Words

- AussieBum: Impact of Globalization

- Importance Of Good Governance - 1978 Words

- Ethical Reflection 1 - 642 Words

- Ethics and Environmental Impacts - 1129 Words

- By Using Corporate Social Responsibility (Csr) the Tobacco Industry Is Seeking to Change Their Unethical Public Image. Evaluate This Strategy Using Three Ethical Principles of the Global Business Standards Codex.

- operations notes - 3840 Words

- Nescafe Brand Management - 6574 Words

- Acca Governance - 3627 Words

- UNIT BA490 COURSEWORK manage physical resource

- Conscious Capitalism In The Documentary 'Not Business As Usual'

- Oraganizational Plan - 666 Words

- Ikea Csr - 4895 Words

- Immigrant Personal Narrative - 482 Words

- Ch 3 Case Lien

- Assigment 1 - 1644 Words

- Genetics Vs Environment - 958 Words

- climate change - 2545 Words

- Virgin Group and Coca Cola Management Strategies

- Report on International Ethical Issues

- Mgt 498 Week 3 Environmental Scan Paper

- Sustainability and Lululemon - 2523 Words

- The Jack Welch Era at General Electric

- Home Depot's Social Responsibility Approach

- Ikea - Business Ethics - 1855 Words

- Employee Engagement Case Study

- eth 501 mod 4

- Health and Health Continuum - 801 Words

- The Responsibility Project - Greyston Bakery

- Sustainability in Stadium - 2198 Words

- Sustainability and Stewardship - 343 Words

- Business Ethics and Business Stakeholders

- Image of Chnage - 2973 Words

- Mgt 405 Ch 1 Notes

- Sustainable objectives - 5473 Words

- MR wang - 2987 Words

- Mega Foods Case Study

- Recycling and Water Resource Management

- Sustainability: Ethical and Social Responsibility Dimensions

- 1.1 Discuss the Purpose of Corporate Communication Strategies

- Final Case - 1108 Words

- Lynn Patterson - 560 Words

- Marketing Notes - 1296 Words

- Nike Company Analysis - 2944 Words

- CSR Lecture One - 3557 Words

- Trung Nguyen's Case Study in Vietnam

- Social Perspective Paper - 1214 Words

- Marketing Effects - 1287 Words

- Corporate Social Responsibility - 1194 Words

- Chad cameroon - 1056 Words

- managerial accounting - 943 Words

- Essay On Republican Party - 515 Words

- Communication and Program Learning Goals

- Mr Leo - 460 Words

- MURFY 2013 BP - 2968 Words

- Marketing Exam 1 Study Guide

- Ethics: Strategic Planning Process

- Supply Chain study Guide

- Environmental Committee - 1470 Words

- Apple Environmental Responsibility Report 2014

- No Drills Corporate Social Responsibility

- The Rise Of Environmentalism In Canada - 1212 Words

- BP Final Paper - 3260 Words

- Week 8 LeeannaHale Frogsleap

- Behaviorism, The Social Learning Theory And Constructivism

- Case 1 3 - 311 Words

- Sustainability for Business Growth - 1031 Words

- Ethical Strategies - 301 Words

- Ethics Program and Monitoring System v1

- Ikea Global Sourcing Challenge

- Nt1330 Unit 1 Assignment

- BUS475 Week 2 Business Model And Strategic Plan Part II

- Sri Lala Literature Review

- Government Vs Tony Soprano

- Chapter 5 and 13 - 863 Words

- Wii and Corporate Social Responsibility

- Mid-Term (Paint Industry Gone Green)

- Corporate Social Responsibility - 1907 Words

- Startegic Analysis (Sherwin Williams)

- Pepsi: Corporate Social Responsibility

- 19 th Century and Business Messages

- Case Study - Wal Mart: the Main Street Merchant of Doom (Corporate Social Responsibility Case Study)

- Deutsche Bank Sustainability Essay

- Logistis Q 2 - 414 Words

- Market Case Analysis - 1548 Words

- Starbucks & Conservation International - 2042 Words

- Plest Analysis for Tesco's and Water Aid

- CSR Essay - 1625 Words

- Better Health for Individuals - 3561 Words

- Exam 1 Study Guide

- No idea - 1483 Words

- Management: Business Ethics and Dr Ross Spence

- Batm : Ethical Case Study

- President Nixon's Involvement In Vietnam

- Sustainable Enterprise - 3239 Words

- nike awareness - 1196 Words

- Sustainability and Local Governing Bodies

- Organizational Issues - 1026 Words

- Draft: Engineering Activities - 3666 Words

- Triple Bottom Line Report

- Business Ethics and Social Responsibility

- Manage Risk 1 - 1725 Words

- Assignment 2 Nik 123

- maketing case - 1454 Words

- 7060 assg 2 - 645 Words

- Nvq Level 3 - 1684 Words

- Business Ethics and Corporate Governance

- Organizational Paper - 685 Words

- Carbon Dioxide and Esg Data

- Chapter 3 Review Questions

- Defining Privilege - 1477 Words

- Environment Obligation of Chevron Corporation

- Gvm Exploration Limited - 3694 Words

- Dannon Case Study - 2156 Words

- Research: Social Responsibility and L ' Oreal

- Sustainability Culture - 1198 Words

- Exam 3 Review - 743 Words

- Cyp 3.3 1.2

- Organisational behaviour - 3074 Words

- Major Assignment Combined - 2357 Words

- Modes Project - 2281 Words

- Legal notification - 3814 Words

- Marketing Micro and Macro Environmental Factors

- Builing block of culture - 1056 Words

- Difficulties in Disorders - 1457 Words

- Religion: Human Rights and Catholic Social Teaching

- Philosophy Friedman - 2205 Words

- Nokia Media Report - 1041 Words

- The examination of Sony - 1646 Words

- os- homework - 455 Words

- Starbucks: Organizational Culture - 1049 Words

- CSR v3 - 2272 Words

- Environmental Reporting Bill Submission

- Analysing Mcdonalds (Fast Food Outlets) Using the Porters 5 Forces Model – Sometimes Called the Competitive Forces Model.

- Essay plan- altruism - 1389 Words

- Business Management Vbd Report

- Ice Hotel2 - 1254 Words

- Social Determinants Of Health - 453 Words

- Case Study Cocoa Delight

- Apple Inc. and Samsung Electronics Industry

- Sustainability and Management Planning Process

- Looking For Alibrandi Identity Analysis

- Advanatages of Free Newspapers - 664 Words

- John Lewis Case Study Final

- Parse's Human Becoming Theory Analysis

- Intro to Business - 1154 Words

- Terracycle: Case Study - Worm Boy

- Sustainable operations lit review

- Human Services Leadership - 974 Words

- Autism research paper - 3009 Words

- In Business - 532 Words

- A Civil Action Paper - 2114 Words

- Marketing Essay - 1042 Words

- Strategic Initiative - 538 Words

- Emerging Markets - 1534 Words

- Hamburger: Hamburger and Mcdonalds Restaurants

- SLE305 TASK 3

- Human Resource Management Interview

- Sumsung Company - 2049 Words

- Green Consumer Behavior - 621 Words

- Coca Cola Ethics Case

- Is green marketing a fad?

- Human Overpopulation Happens When A Great Number Of People Goes Over The Carrying Capacity Of A Region That The Group Is In

- Mgt230 R3 Student Guide Week1

- Assignment: Corporation and James Hardie

- Consultation Skill Case Study Assignment 2

- Atv Dealership - 692 Words

- final outline PIL - 2847 Words

- Business report on the gla and the mayor of london

- Hongkong Disneyland - 5964 Words

- Mike: Brand and Ann Taylor

- Ib Abnormality Notes - 880 Words

- Ethics: Management and Business Ethics Stakeholder

- Business: Employment and American Mcdonalds Offer

- CSR report of baidu - 3451 Words

- Ethics Case Study - 1046 Words

- Goodyear Tire and Rubber - 1280 Words

- Social Responsiblity as Stewardship - 1395 Words

- HRM 498 Week 1 Individual Assignment; Management Challenges & Concerns

- State Responsibility Vs Night Watchman

- Caterpiller Inc. Vs. World

- CSR Speaker Notes - 369 Words

- Healthy People 2020 Summary

- New Balance Csr Case Study

- Postmodernism: Organization-Environment Relations

- Legal and Ethical Considerations of Marketing

- Assignment: Marketing and Bbc Documentary Primark

- chapter 1 auditing notes

- The Body Shop - 3874 Words

- Rio Tinto's chart of conduct

- Ethical Reasoning In The Workplace - 1561 Words

- Nature of Business - 545 Words

- Assignment One - 2222 Words

- Starbucks Case - 1391 Words

- Quality Management In Bangladesh - 1628 Words

- International Business Environment Challenges and Changes

- Organization and Organisational Effectiveness - 407 Words

- Business: Marketing and Consumer Behavior

- sociology 1 14 - 1758 Words

- Joutnal Set - 1128 Words

- Times Roman and Foreign Market Entry

- Frito-Lay: Sustainability Study and SWOT Analysis

- Commerce: Consumer Protection and Decisions

- Roe V. Wade Case Study

- The Role of a Community Counselor - 1730 Words

- A plan review of Dartmoor National Park Core Strategy

- Pestle Analysis on the Cruise Industry

- Human Source - 1413 Words

- Business Ethics and Woodland Products

- Phase 2 Final - 6121 Words

- Lecture Notes November 11th

- Literature Review - 2205 Words

- Consumption, Carbon, And Toxins: Chapter Analysis

- Portman Hotel - 1698 Words

- Purchasing and Supply Management REPORT

- Nutrition and Main Food Groups

- The Corporation - Ethical Analysis - 2746 Words

- Arcadia Group Pest Analysis

- Intro to Human Resources - 1559 Words

- Holocaust Trauma Case Study

- British American Tobacco - 4316 Words

- CNDV 5311 - 3592 Words

- The Business Environment: Energy and the Economy

- Sustainability Case Assignment 1 1

- Case Study: An Overview Of Pepsico

- Week 3 Starbucks - 791 Words

- MKT Week 5 Environmental Factors

- Susutainability Development in O & G Industry

- Career Plan - 464 Words

- Managerial acct - 1291 Words

- Corporate Responsiblity Powerpoint Presentation 4

- Lecture 1 HR Introduction

- Foster Care System - 1568 Words

- Written Campaign Proposal: Bullying

- Basic in Management - 2140 Words

- Sustainability Is Dead - 1049 Words

- Child Development - 1328 Words

- Muslim Women In Canada - 1371 Words

- Financial Accounting Theory - 1728 Words

- CSX Group Marketing Project

- CSR in singapore - 1639 Words

- McDonald’s Corporation - 1373 Words

- Starbucks Case Study Analysis

- Midterm 1 Sample MC Questions 1

- Human and Self-care Demand

- Ethics In Finance Class 10

- Hydraulic Fracturing Case Study

- What Are the Sources and Limits of Mnc Power

- Economic and Social Effects of Climate Change

- Business Environment - 341 Words

- Barbados: Credit Unions - 1347 Words

- Starbucks Case Analysis - 7766 Words

- Radiance Reconstructive Surgery - 858 Words

- Cedric 1 - 3577 Words

- Child Development Stages - 1087 Words

- Embedded-Sustainability---a-Strategy-for-Market-Leaders

- Ikea Way - 3203 Words

- Marketing Strategy of Burger King

- Evaluating Contemporary Views of Leadership

- case 2 - 512 Words

- Health and Social Care- Case Study- P3/P4/M2/D2

- Responsible Business - 1915 Words

- Education and Positive Learning Environment

- Schizophrenia and Grey Matter Areas

- Economics and Sainsbury Plc Sainsbury

- Costco's Study Case - 1079 Words

- Caprica Energy and Its Choice

- Report on Toshiba and Nintendo - 3480 Words

- Microsoft Word 2 - 935 Words

- Business Ethics and Barclays - 1865 Words

- Chapter 1 - 852 Words

- Bp Oil Spill - 1501 Words

- Corporate Social Responsibility - 2548 Words

- Kathryn Sands Briefing Note

- Case Study: Parker V. Barefoot

- Psy Week1 - 560 Words

- Ethical Behavior in Marketing - 476 Words

- B Corporations Solving Societys Problem

- Sustainability Accounting - 1895 Words

- IFRS Help Sheet - 6334 Words

- Timberland Marketing - 853 Words

- Public Speaking - 345 Words

- What Forces in the Marketing Environment Appear to Pose the Greatest Challenges to Timberland's Marketing Performance?

- Pets & More - 866 Words

- Genetically Modified Organism and Gm Foods

- Why is it important to enhance good corporate governance

- 02 EXAM 3 on India 2015

- img20130415 21261579 - 344 Words

- Pest Analysis on Telenor in Pakistan

- Lesson 1 Legislation Portfolio Evidence

- Moral Leadership And Ethics Randonis Revised

- Economic Impact - 2457 Words

- Ethics: Discrimination and Social Responsibility

- C. Market d. - 1817 Words

- Ecotourism: Improving Sustainability in the Tourism Industry

- Work Skills for effective learning 5

- Sources of Ethics - 20200 Words

- Assignment 2: Challenges in the Global Business Environment

- craneandmatten3e ch01 1

- Leisure Essay - 2450 Words

- BUS670 Week 2 Discussion 1

- Ted Steinberg's Act Of God

- IKEA V2 - 3021 Words

- Assignment 1 ECON 405

- Biosphere Worksheet - 920 Words

- In Cold Blood Nature Vs Nurture Essay

- literature review - 460 Words

- Marketing Plan - 4902 Words

- Soft Drink and Pepsico - 984 Words

- Case Analysis: Wal-Mart Rosemead

- Judith Thomson Abortion - 779 Words

- Ba Business - 898 Words

- Psychology Assignment - 895 Words

- Dissertation: Consumer Behaviour and Ethical Fashion

- Monsanto Case Study - 1564 Words

- Incompatibilism: Do We Have Free Will?

- Tourism; a Blessing or Curse - 1923 Words

- Indigenous Sovereignty Research Paper

- Schizophrenia & OCD - 3482 Words

- Business Report - 1249 Words

- Geog 350 - 2377 Words

- international management - 2497 Words

- Individual Development Plan - 1455 Words

- green computing - 3424 Words

- Abnormality Essay Discuss Two or More Definitions of Abnormality

- Textile Project - 2037 Words

- Business Ethics and Tourism - 5071 Words

- Student: Organic Food and Foods Tactic

- Ethics In Security - 1810 Words

- Sustainability - 4577 Words

- Miller Brewery - 3620 Words

- Leighton Holdings Entry to China

- The Walt Disney Company - 3878 Words

- Lean Six Sigma - 423 Words

- I Just Want to Read Something.

- The Price of Progress: How Much Are We Willing to Pay?

- Teen pregnancy - 879 Words

- Implementation of Sustainability - 3046 Words

- Thanksgiving: Crime and Theory - 1619 Words

- uniform public services - 2417 Words

- Social Sustainability - 890 Words

- Redlining Research Paper - 1296 Words

- Sustainable Development and Ecosystem Services

- Social Performance of Organizations - 2133 Words

- Business Pollution - 1489 Words

- Business ethic ssessement task one

- Corporate Social Responsibility and Ngos

- Joseph Schumpeter - 720 Words

- White dog cafe case

- Monsanto's Moral Obligation - 394 Words

- Zhu 2014 Ecology Updated Supplemental Syllabus Draft 1392564861

- Marketing and Customer Value - 2273 Words

- Operational Definition Of Health - 1168 Words

- 2015 1 Accounting in organisations and society Assignment

- United Kingdom and Northern Ireland assembly

- Astrazeneca and Csr - 1722 Words

- British Petroleum (Bp) Case Study

- Miro: Externality and Pollution - 1267 Words

- 1st reference - 6433 Words

- Audi Research Paper - 1355 Words

- Kiribati: Anote Tong and Kiribati Introduction Kiribati

- Chapter 2 Review Questions

- Operations Notes - 8673 Words

- Management Accounting - 4280 Words

- Creating Good Policy - 3232 Words

- Visitor Enjoyment - 611 Words

- Sustainable Tourism - 1042 Words

- Salt Lake Olympic Bribery Scandal

- The Art - 1123 Words

- International Business - 3481 Words

- Disease Trends and the Delivery of Health Care Services

- Singapore Enviornment - 450 Words

- Psychology Study Guide - 1476 Words

- Kpmg Analysis - 3061 Words

- Nurse Anesthetists Essay - 725 Words

- Alex wangzi outline - 1264 Words

- Management and Strategy Tactics Kpi

- Research Paper - 2580 Words

- Whole Foods Core Value Essay

- Apple Ethics BUS 508

- BBA102 Wk 3 Sustainability Copy

- A Criminal in the Making - 3495 Words

- Classic Study in Social Psychology

- Globalization: Foreign Exchange Market

- Assessment Task 3 - 1172 Words

- Organization and Leadership - 3719 Words

- Pharmaceutical Industry and Drug Cost Vogel

- Final Study Guide for Livanis Intl 1101

- BUS475 Assignment 1

- Welfare and United States - 1969 Words

- Marketing: Marketing and Kraft Foods

Popular Topics:

- Lady Macbeth Essay

- Corruption in South Africa Essay

- My Childhood Memories Essay

- Antigone Essay

- Conservation of Trees Essay

- The Great Depression Essay

- The Kite Runner Essay

- First Day of School Essay

- Good Habits Essay

- Persuasive Essay About Love

- Get involved

Accountability

Social and environmental sustainability in undp.

UNDP is committed to ensuring that our programming and operations are socially and environmentally sustainable.

Sustainable Programme and project management

UNDP recognizes that social and environmental sustainability are fundamental to the achievement of sustainable development outcomes, and therefore must be fully integrated into our Programmes and Projects. To ensure this we have the following key policies, procedures and accountability mechanisms in place to underpin our support to countries:

- Social and Environmental Standards for UNDP Programmes and Projects

- Project-level Social and Environmental Screening Procedure

- Accountability Mechanism with two key functions: 1. A Stakeholder Response Mechanism that ensures individuals, peoples, and communities affected by UNDP projects have access to appropriate procedures for hearing and addressing project-related grievances. 2. A Compliance Review process to respond to claims that UNDP is not in compliance with UNDP’s social and environmental policies.

Environmentally sustainable operations

As a global leader in the fight against climate change, UNDP is committed to being green, sustainable, and just. UNDP has been climate neutral in its global operations since 2015 and has made an ambitious commitment to reduce its carbon footprint by 50% by 2050 through the Greening UNDP Moonshot. Read more ...

Sustainable procurement

To help countries achieve the simultaneous eradication of poverty and significant reduction of inequalities and exclusion, while at the same time address the issues of climate change, UNDP makes a shift to more sustainable production and consumption practices. Sustainable procurement means making sure that the products and services UNDP buys are as sustainable as possible, with the lowest environmental impact and most positive social results. Procurement, therefore, plays a key role in contributing to sustainable development.

Please find more information on the UNDP Procurement Website .

Related resources

- Framework for Advancing Environmental and Social Sustainability in the UN System

- UN Greening the Blue

Explore more

Undp social and environmental standards.

The revised Social and Environmental Standards (SES) came into effect on 1 January 2021 . The SES underpin UNDP's commitment to mainstream social and environmental sustainability in our Programmes and Projects to support sustainable development.

The SES are an integral component of UNDP’s quality assurance and risk management approach to programming. This includes our Social and Environmental Screening Procedure .

Key Elements of the UNDP's Social and Environmental Standards include:

Part A: Programming Principles:

- Leave No One Behind

- Human Rights

- Gender Equality and Women's Empowerment

- Sustainability and Resilience

- Accountability

Part B: Project-Level Standards:

- Standard 1: Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Natural Resource Management

- Standard 2: Climate Change and Disaster Risks

- Standard 3: Community Health, Safety and Security

- Standard 4: Cultural Heritage

- Standard 5: Displacement and Resettlement

- Standard 6: Indigenous Peoples

- Standard 7: Labour and Working Conditions

- Standard 8: Pollution Prevention and Resource Efficiency

Part C: Social and Environmental Management System Requirements:

- Quality Assurance and Risk Management

- Screening and Categorization

- Assessment and Management

- Stakeholder Engagement and Response Mechanism

- Access to Information

- Monitoring, Reporting and Compliance

UNDP's Social and Environmental Screening Procedure (SESP)

Screening and categorization of projects is one of the key requirements of the Social and Environmental Standards (SES) .

In this regard, the objectives of UNDP's Social and Environmental Screening Procedure (SESP) are to:

- Integrate the SES Programming Principles in order to maximize social and environmental opportunities and benefits and strengthen social and environmental sustainability;

- Identify potential social and environmental risks and their significance;

- Determine the project's risk category (Low, Moderate, Substantial, High); and,

- Determine the level of social and environmental assessment and management required to address potential risks and impacts.

News from the Columbia Climate School

The Role of Individual Responsibility in the Transition to Environmental Sustainability

Steven Cohen

We New Yorkers live in a city that is on a gradual transition toward environmental sustainability, but we are a long way from the place we need to end up. A circular economy where there is no waste and where all material outputs become inputs is well beyond our technological and organizational capacity today. But that does not mean we shouldn’t think about how to get from here to there. Much of the work in building environmental sustainability requires the development of systems that enable us to live our lives as we wish while damaging the planet as little as possible. Large-scale institutions are needed to manage sewage treatment and drinking water, to develop renewable energy and build a modern energy grid. Government policy is needed to ensure the conservation of forests, oceans, and biodiversity. Pandemic avoidance requires global, national and local systems of public health. Climate change mitigation and adaptation also require collective action. What then can individuals do?

As individuals, we make choices about our own activities and inevitably, they involve choices about resource consumption. I see little value in criticizing people who fly on airplanes to travel to global climate conferences. (I assume you do remember airplanes and conferences, don’t you?) But I see great value in considering the importance of your attendance at the conference and asking if the trip is an indulgence or if you will have an important opportunity to learn and teach. This year has taught us how to attend events virtually. There is little question that live presence at an event enables a type of communication that can’t be achieved virtually. Many times, you will judge that the financial and environmental cost of the trip is far outweighed by the benefits. Those are the times you should travel. My argument here is that it is the thought process, the analysis of environmental costs and benefits, that is at the heart of an individual’s responsibility for environmental sustainability. Individuals are responsible for thinking about their impact on the environment and, when possible, minimize the damage they do to the planet.

Everyone needs to turn on the lights at night, start the shower in the morning, turn on the air conditioning and possibly drive somewhere on Mother’s Day. I would never argue that you should give up these forms of consumption. Instead, I believe we should all pay attention to the resources we use and the impact it has. We are responsible for that thought process and the related analysis of how we, as individuals, might accomplish the same ends with less environmentally damaging means.

Some say that the fixation on individual responsibility is a distraction from the more important task of compelling government and major institutions to implement systemic change. This perspective was forcefully argued in 2019 in The Guardian by Professor Anders Levermann of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. According to Professor Levermann:

“Personal sacrifice alone cannot be the solution to tackling the climate crisis. There’s no other area in which the individual is held so responsible for what’s going wrong. And it’s true: people drive too much, eat too much meat, and fly too often. But reaching zero emissions requires very fundamental changes. Individual sacrifice alone will not bring us to zero. It can be achieved only by real structural change; by a new industrial revolution. Looking for solutions to the climate crisis in individual responsibilities and actions risks obstructing this. It suggests that all we have to do is pull ourselves together over the next 30 years and save energy, walk, skip holidays abroad, and simply ‘do without.’ But these demands for individual action paralyse people, thereby preventing the large-scale change we so urgently need.”

Perhaps, but I do not see it that way. I consider individual responsibility and the thought process and value shift that stimulates individual action as the foundation of the social learning process required for effective collective action. In other words, individual change and collective system-level change are interconnected. The fact is that on a planet of nearly 8 billion people, it is too late for many of us to get back to the land and live as one with nature. There’s too many of us and not enough nature. There is an absolute limit to our ability as individuals to reduce our impact on the planet. Therefore, system-level change is absolutely needed. But system change requires individuals to understand the need for change along with a well-understood definition of the problem. The cognitive dissonance of identifying a problem but never acting on it is difficult to live with. If you see a poor child on the street begging for food, you can provide that child with food and money while continuing to support public policy that addresses the child poverty issue at the systems level. In fact, the emotional impact of that child’s face may well provide the drive that leads you to fight harder for the policy that would prevent that child from needing to beg. We learn by example, and vivid experiences and cases can lead to transformative systemic change.

While I consider individual and collective responsibility connected, without collective systems and infrastructure supporting environmental sustainability, there are distinct limits to what individual action can achieve. That is why I see no value in shaming individuals for consuming fossil fuels, eating meat, or buying a child a Mylar birthday balloon. I believe an attitude of moral superiority is particularly destructive in any effort to build the political support needed for systemic change.

As my mentor, the late Professor Lester Milbrath, often argued, the only way to save the planet is through social learning that would enable us to “learn our way to a sustainable society.” He made this argument in his pathbreaking work: Envisioning a Sustainable Society: Learning Our Way Out . In Milbrath’s view, the key was to understand environmental perceptions and values and to build on those values and perceptions to change both individual behavior and the institutions their politics generated. To Milbrath, the human effort to dominate nature had worked too well, and a new approach was needed. As he observed in Envisioning a Sustainable Society :

“Learning how to reason together about values is crucial to saving our species. As a society we have to learn better how to learn, I call it social learning; it is the dynamic for change that could lead us to a new kind of society that will not destroy itself from its own excess.”

My view is that one method to pursue social learning is learning by doing — in other words by encouraging the individual behaviors we might each take to reduce our environmental impact. Those behaviors remind us to think about the planet’s wellbeing along with our own. They reinforce and remind us and as they become habit, they impact our values and our shared understanding of how the world works.

There is, therefore, no tradeoff between individual and collective responsibility for protecting the environment unless we insist on creating one. Additionally, in a world of extreme levels of income inequality, wealthy people who have given up eating meat have the resources to consume alternative sources of nourishment. They do not occupy the moral high ground criticizing an impoverished parent proudly serving meat to their hungry child. In our complex world, we should mistrust simple answers and instead work hard to understand the varied cultures, values and perceptions that can contribute to the transition to an environmentally sustainable global economy. The path to environmental sustainability is long and winding and will require decades of listening and learning from each other.

Related Posts

Can Digital Payments Help Countries Adapt to Climate Change?

Alumni Spotlight: A Journey From Climate Conservation to Corporate Consulting

Finding Public Space in a Crowded New York City

Columbia Climate School has once again been selected as university partner for Climate Week NYC, an annual convening of climate leaders to drive the transition, speed up progress and champion change. Join us for events and follow our coverage .

Steve, I appreciate your perspective on individual responsibility. I am developing a similar position and submitted an “OpEd” piece to Times about a month ago but alas it didn’t get published. I would like to share and develop the conversation with you so please reach out.

What are the responsibilities of individuals, governments and the international community in helping people have access to water?

While this highly educated society continues the GDP rat race and decimating all other patterns that create balance in the world we live in, here’s a little story of obvious stupidity for fun and profit. In 1975 my wife and I after several years of college chose to listen to scientists’ warnings about continued expansionism economically. We simplified our lives and did without things like electricity, fancy new vehicles and useless bling. We did without as a plausible direction for a template of living lightly and securing a viable future for more than just humans. We endured countless slurs ( tree huggers, eco-terrorists, hippies,) and were subjected to verbal and realistic abuse . Now at 72 and 68 we are wondering where the hell were the rest of you? Read the book “Small is Beautiful ” to see the wrongheaded direction your politicians and some clergy and certainly all greedy vulture capitalist have led the general public. I have no patience for obvious stupidity .Yeah, we were WOKE long before most people and feel no compulsion to be apologetic as all of you are to blame if you help continue the narrative of GDP unlimited growth and the population explosion. nats remark

“perhaps, but i do not see it that way” sorry but that kinda just means your guile is weak and you’re extremely credulous and succeptable to propeganda, dunno what to tell ya bud but this perspective is a total nothingburger. Of Course we must needs rely on some great measure of personal choice here, but if my choices are: Waste, Waste, Out of my Budget well i dont REALLY have a choice then Do I? which means that for the majority of americans there is no ethical choice list they can follow to fix the problem, only by compelling legislation can those choices be made available to them.

Get the Columbia Climate School Newsletter

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Truth About CSR

- V. Kasturi Rangan,

- Lisa Chase,

- Sohel Karim

Despite the widely accepted ideal of “shared value,” research led by Harvard Business School’s Kasturi Rangan suggests that this is not the norm—and that’s OK. Most companies practice a multifaceted version of CSR that spans theaters ranging from pure philanthropy to environmental sustainability to the explicitly strategic. To maximize their impact, companies must ensure that initiatives in the various theaters form a unified platform. Four steps can help them do so:

Pruning and aligning programs within theaters. Companies must examine their existing programs in each theater, reducing or eliminating those that do not address an important social or environmental problem in keeping with the firm’s business purpose and values.

Developing metrics to gauge performance. Just as the goals of programs vary from theater to theater, so do the definitions of success.

Coordinating programs across theaters. This does not mean that all initiatives necessarily address the same problem; it means that they are mutually reinforcing and form a cogent whole.

Developing an interdisciplinary CSR strategy. The range of purposes underlying initiatives in different theaters and the variation in how those initiatives are managed pose major barriers for many firms. Strategy development can be top-down or bottom-up, but ongoing communication is key.

These practices have helped companies including PNC Bank, IKEA, and Ambuja Cements bring discipline and coherence to their CSR portfolios.

Most of these programs aren’t strategic—and that’s OK.

Idea in Brief

The problem.

Many companies’ CSR initiatives are disparate and uncoordinated, run by a variety of managers without the active engagement of the CEO. Such firms cannot maximize their positive impact on the social and environmental systems in which they operate.

The Solution

Firms must develop coherent CSR strategies, with activities typically divided among three theaters of practice. Theater one focuses on philanthropy, theater two on improving operational effectiveness, and theater three on transforming the business model to create shared value.

Companies must prune existing programs in each theater to align them with the firm’s purpose and values; develop ways of measuring initiatives’ success; coordinate programs across theaters; and create an interdisciplinary management team to drive CSR strategy.

Most companies have long practiced some form of corporate social and environmental responsibility with the broad goal, simply, of contributing to the well-being of the communities and society they affect and on which they depend. But there is increasing pressure to dress up CSR as a business discipline and demand that every initiative deliver business results. That is asking too much of CSR and distracts from what must be its main goal: to align a company’s social and environmental activities with its business purpose and values. If in doing so CSR activities mitigate risks, enhance reputation, and contribute to business results, that is all to the good. But for many CSR programs, those outcomes should be a spillover, not their reason for being. This article explains why firms must refocus their CSR activities on this fundamental goal and provides a systematic process for bringing coherence and discipline to CSR strategies.

- VR V. Kasturi Rangan is a Baker Foundation Professor at Harvard Business School and a cofounder and cochair of the HBS Social Enterprise Initiative.

- Lisa Chase is a research associate at Harvard Business School and a freelance consultant.

- SK Sohel Karim is a cofounder and the managing director of Socient Associates, a social enterprise consulting firm.

Partner Center

- Contributors

Introduction to ESG

Mark S. Bergman , Ariel J. Deckelbaum , and Brad S. Karp are partners at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP. This post is based on a recent Paul Weiss memorandum by Mr. Bergman, Mr. Deckelbaum, Mr. Karp, David Curran , Jeh Charles Johnson , and Loretta E. Lynch . Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here ) and Socially Responsible Firms by Alan Ferrell, Hao Liang, and Luc Renneboog (discussed on the Forum here ).

Interest on the part of investors and other corporate stakeholders in environmental, social and governance (“ESG”) matters has surged in recent years, and the current economic, public health and social justice crises have only intensified this focus. ESG, at its core, is a means by which companies can be evaluated with respect to a broad range of socially desirable ends. ESG describes a set of factors used to measure the non-financial impacts of particular investments and companies. At the same time, ESG also provides a range of business and investment opportunities.

Net flows into ESG funds available to U.S. investors have skyrocketed, totalling $20.6 billion in 2019, nearly four times the previous annual record set in 2018, [1] while ESG funds in Europe also attracted record inflows of $132 billion in 2019. [2] More than 70% of funds focused on ESG investments outperformed their counterparts in the first four months of 2020, [3] and nearly 60% of ESG funds outperformed the wider market over the past decade. [4] Consumers and investors are placing a growing value on ESG, and industry leaders have responded in a number of ways, including issuing comprehensive sustainability reports and expanding ESG disclosures in their annual reports, providing information to ESG rating agencies and publicly communicating ESG commitments.

This post, the first in a series focused on ESG disclosure and regulatory developments, provides an introduction to ESG and identifies several critical issues for companies and their in-house counsel to keep in mind in evaluating and monitoring ESG actions and statements.

The Fundamentals of ESG

ESG grew out of investment philosophies clustered around sustainability and, thereafter, socially responsible investing. Early efforts focused on “screening out” (that is, excluding) companies from portfolios largely due to environmental, social or governance concerns, while more recently ESG has favorably distinguished companies that are making positive contributions to the elements of ESG, premised on treating environmental and social issues as core elements of strategic positioning. While climate figures prominently in ESG discussions, there is no single list of ESG goals or examples, and ESG concepts often overlap. That being said, the three categories of ESG are increasingly integrated into investment analysis, processes and decision-making.

- The “E” captures energy efficiencies, carbon footprints, greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, biodiversity, climate change and pollution mitigation, waste management and water usage.

- The “S” covers labor standards, wages and benefits, workplace and board diversity, racial justice, pay equity, human rights, talent management, community relations, privacy and data protection, health and safety, supply-chain management and other human capital and social justice issues.

- The “G” covers the governing of the “E” and the “S” categories—corporate board composition and structure, strategic sustainability oversight and compliance, executive compensation, political contributions and lobbying, and bribery and corruption.

ESG metrics have evolved in recent years to measure risk as well as opportunity. In his “Dear CEO” letter in 2018, BlackRock Chairman and CEO Larry Fink wrote that:

[s]ociety is demanding that companies, both public and private, serve a social purpose. To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society. Companies must benefit all of their stakeholders, including shareholders, employees, customers, and the communities in which they operate.

He goes on to say that:

Companies must ask themselves: What role do we play in the community? How are we managing our impact on the environment? Are we working to create a diverse workforce? Are we adapting to technological change? Are we providing the retraining and opportunities that our employees and our business will need to adjust to an increasingly automated world? Are we using behavioral finance and other tools to prepare workers for retirement, so that they invest in a way that will help them achieve their goals? [5]

Other leading business leaders have also supported more expansive views regarding the purpose of a corporation. In August 2019, the Business Roundtable, a non-profit organization comprised of corporate CEOs, released a new Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation (the “BRT Statement”). [6] The BRT Statement was signed by the CEOs of nearly 200 leading U.S. companies and identified shareholders as one of five key stakeholders—along with customers, workers, suppliers and communities. The BRT Statement supersedes prior statements that endorsed shareholder primacy (the idea that corporations exist principally to serve shareholders), and “outlines a modern standard for corporate responsibility.” [7]

ESG in Practice

Under the current disclosure regime applicable to public companies listed in the United States, there is no affirmative duty to provide disclosures on ESG matters. As a practical matter, however, it can be anticipated that important stakeholders, such as investors, insurance companies, lenders, regulators and others, will increasingly look to companies’ disclosures to allow them to evaluate whether those companies have embraced ESG agendas. And, even in the absence of an affirmative duty to disclose, the substance of the information that companies do elect to report regarding their actions to identify and manage ESG risks and opportunities will be subject to the securities laws.

As we will discuss in future posts in this series, the ESG regulatory landscape regarding disclosure is rapidly evolving. While there is a general recognition of the value of, and the imperative for, consistent and decision-critical information to more easily evaluate how companies are overseeing and managing ESG-related risks and opportunities, most companies have yet to achieve that level of consistency. Moreover, ESG factors cover a broad range of activities that may or may not be relevant to particular businesses and their performance, or their potential positive effect on communities, or more broadly, societies. These metrics need to be refined. Accordingly, a prudent public company will find it desirable to establish its own criteria for determining the scope and content of its ESG disclosures, both to mitigate legal risk and identify future opportunities that ESG presents in terms of growth and differentiation.

In the absence of international consensus regarding ESG disclosures, a number of frameworks and indices have emerged to guide company disclosures and inform investors. Some of the leading international frameworks include the Global Reporting Initiative standards, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) standards, the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Ratings have also proliferated over the last decade. Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) and specialist firms such as Sustainalytics have recently been joined by traditional credit rating agencies such as Moody’s and S&P Global. A recent estimate suggests that the “global market for ESG ratings is currently worth about $200m and could grow to $500m within five years.” [8] The influence of these frameworks and rating agencies is such that they may shape regulation to come.

ESG is also influenced by public opinion. ESG issues are inherently reputational, especially given recent societal events. As more companies provide ESG disclosures and commitments, and given the speed of social media responses and the news cycle, observations about a company’s ESG actions or inactions are often published and sometimes go viral. Companies that are out of step with public opinion and market demands may face punishing reputational consequences.

Matching Aspiration and Action

We will describe in subsequent alerts the challenges faced by companies in developing a disclosure posture that satisfies the needs of a growing number of stakeholders, as well as the challenges faced by many of those stakeholders in obtaining information that is consistent and decision-critical. While ESG disclosures today are, from an SEC perspective, purely voluntary, over time that could change, and in the meantime there may be increasing pressure from a range of stakeholders to incorporate ESG statements. If a company’s ESG disclosures (for example, those in relation to compliance with legal, regulatory or voluntary standards or a particular commitment to achieve an ESG-positive outcome) later appear to be false or misleading, the company could face reputational backlash, shareholder lawsuits or possibly regulatory enforcement. Putting aside which disclosure standards they adopt, companies should ensure that they take a systematic approach to ESG reporting.

We highlight below considerations that should facilitate tying aspirations to actions and mitigating legal and reputational risks for commitments that cannot realistically be achieved:

- Monitor internal ESG disclosures and commitments . Management should appoint a team tasked with monitoring the company’s ESG disclosures and commitments, recognizing that these statements can appear in a variety of formal communications ( g. , SEC filings, or in documents incorporated by reference in SEC filings, sustainability reports and corporate responsibility reports) as well as informal communications ( e.g. , communications to employees, social media posts, media interviews and website postings). The team should identify existing ESG commitments to establish a baseline. Thereafter, the team should have a procedure in place to monitor ESG disclosures of the company as well as of peer firms.

- ESG statements made publicly should be vetted for factual accuracy and context in the same way as any other statement of fact.

- Forward-looking commitments should be qualified as such, much as other forward-looking statements are (with aspirational qualifiers and appropriate disclaimers).

- Management should consider extending the internal disclosure controls and procedures process to ESG statements, since some statements may well find their way into SEC filings.

- Even though ESG disclosure standards are not mandatory, the SEC has noted that it will be comparing information that is voluntarily provided with disclosures made in SEC reports and registration statements, which is consistent with its general approach of monitoring analyst and investor calls as well as other statements made outside of SEC filings (for example, to police the use of non-GAAP financial measures and selective disclosure rules).

- As with all material statements that are included in public disclosure, coordination among the relevant internal constituencies is critical and collaboration should be encouraged.

- Educate employees on the risks associated with ESG disclosures . Employees responsible for preparing and updating ESG disclosures should be sensitized to the risks associated with public disclosures and to the importance of ensuring that ESG statements are consistent with the company’s description of its business, its MD&A and its risk factors in annual and quarterly reports, even if those latter disclosures have no apparent ESG themes.

- Measure ESG performance . The ESG team should establish procedures to determine whether the company’s actions match its public ESG goals, the standards set by industry leaders and the frameworks established by third parties that the company has committed to—or is required to—follow. Doing so can help a company identify any vulnerabilities in order to mitigate potential legal and reputational risks.