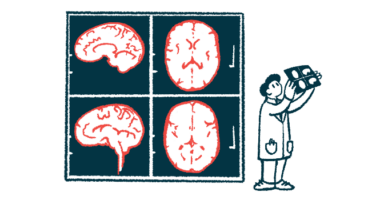

Clinical Presentation: Case History # 1 Ms. C is a 35 year old white female. She came to Neurology Clinic for evaluation of her long-term neurologic complaints. The patient relates that for many years she had noticed some significant changes in neurologic functions, particularly heat intolerance precipitating a stumbling gait and a tendency to fall. Her visual acuity also seemed to change periodically during several years. Two months ago the patient was working very hard and was under a lot of stress. She got sick with a flu and her neurologic condition worsened. At that time, she could not hold objects in her hands, had significant tremors and severe exhaustion. She also had several bad falls. Since that time she had noticed arthralgia on the right and subsequently on the left side of her body. Then, the patient abruptly developed a right hemisensory deficit after several days of work. The MRI scan was performed at that time and revealed a multifocal white matter disease - areas of increased T2 signal in both cerebral hemispheres. Spinal tap was also done which revealed the presence of oligoclonal bands in CSF. Visual evoked response testing was abnormal with slowed conduction in optic nerves. (Q.1) (Q. 2) (Q.3) Today, the patient has multiple problems related to her disease: she remains weak and numb on the right side; she has impaired urinary bladder function which requires multiple voids in the mornings, and nocturia times 3. She became incontinent and now has to wear a pad during the day. (Q.4) She also has persistent balance problems with some sensation of spinning, and she is extremely fatigued. REVIEW OF SYSTEMS is also significant for a number of problems related to her suspected MS. The patient has a tendency to aspirate liquids and also solids. (Q.5) (Q.6) She complains of tinnitus which is continuous and associated with hearing loss, more prominent on the left. She has decreased finger dexterity and weakness of the hands bilaterally. She also complains of impaired short-term memory and irritability. FAMILY HISTORY is significant for high blood pressure, cancer and heart disease in the immediate family. PERSONAL HISTORY is significant for mumps and chicken pox as a child, and anemia and allergies with hives later in life. She also had a tubal ligation. NEUROLOGIC EXAMINATION: Cranial Nerve II - disks are sharp and of normal color. Funduscopic examination is normal. Cranial Nerves III, IV, VI - no extraocular motor palsy or difficulties with smooth pursuit or saccades are seen. Remainder of the cranial nerve exam is normal except for decreased hearing on the left, and numbness in the right face, which extends down into the entire right side. The Weber test reveals greater conductance to the right. Rinne's test reveals air greater than bone bilaterally. (Q.7) The palate elevates well. Swallow appears to be intact. Tongue movements are slowed, but tongue power appears to be intact. Motor examination reveals relatively normal strength in the upper extremities throughout. However, rapid alternating movements are decreased in both upper extremities and the patient has dysdiadochokinesia in the left hand. (Q.8) Mild paraparesis is noted in both legs without severe spasticity. Deep tendon reflexes are +2 and symmetrical in the arms, +3 at the ankles and at the knees. Bilateral extensor toe sign are present. Sensory exam reveals paresthesia on the right to touch and decreased pin sensation on the right diffusely. The patient has mild vibratory sense loss in the distal lower extremities. Romberg's is negative. (Q.9) Tandem gait is mildly unstable. Ambulation index is 7.0 seconds for 25 feet. (The patient takes 7.0 seconds to walk 25 feet.) Diagnosis: Multiple Sclerosis with laboratory support. © John W.Rose, M.D., Maria Houtchens, MSIII, Sharon G. Lynch, M.D.

Diagnosis and management of multiple sclerosis: case studies

Affiliation.

- 1 Multiple Sclerosis Program, Department of Neurology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, TX 75390-9036, USA.

- PMID: 16684629

- DOI: 10.1016/j.ncl.2006.01.002

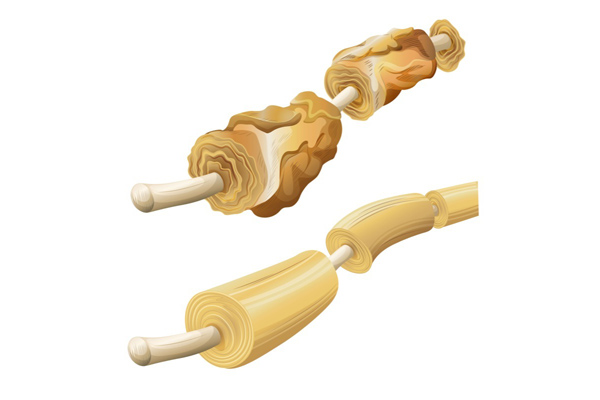

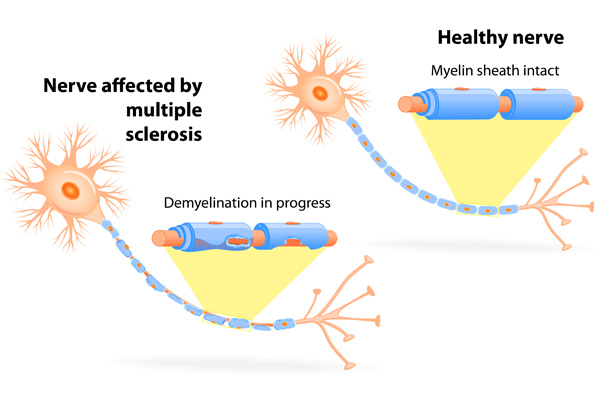

Although substantial capabilities have emerged in the ability to globally manage patients who have MS, clinicians continue to be confronted with formidable challenges. Reduction in disease activity and its impact on dis-ability progression remains the central objective of disease-modifying therapy and most current MS research initiatives. Nevertheless, the principal factors that determine the day-to-day limitations on functional capabilities(activities of daily living, work performance, quality of life, and so forth)are a derivative of the pathophysiology of the disease process itself. The substrate for these limitations is inherent in the pathology of demyelination and axonal dysfunction. Identifying measures that can optimize the performance and fidelity of axonal conduction mechanisms may translate into a reduction in MS-related symptoms. Chronic neurologic disease management (with MS representing a signature example) can be optimized when all members of the care team (including patients and their families) collaborate in the co-ordination of interdisciplinary care models that address all aspects of suffering.

Publication types

- Case Reports

- Adjuvants, Immunologic / therapeutic use*

- Anti-Inflammatory Agents / therapeutic use*

- Brain / pathology

- Diagnosis, Differential

- Disease Progression

- Interferon beta-1b

- Interferon-beta / therapeutic use*

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- Middle Aged

- Multiple Sclerosis / drug therapy*

- Multiple Sclerosis / pathology*

- Multiple Sclerosis, Relapsing-Remitting / pathology

- Multiple Sclerosis, Relapsing-Remitting / therapy

- Optic Neuritis / pathology

- Adjuvants, Immunologic

- Anti-Inflammatory Agents

- Interferon-beta

- © 2017

Case Studies in Multiple Sclerosis

- Paul S. Giacomini 0

McGill University , MONTREAL, Canada

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

- A collection of case studies illustrating the complex, unpredictable nature of multiple sclerosis and its many presentations and disease courses

- Case studies submitted from clinicians from some of the world's leading neurology departments

- Edited by Dr Paul Giacomini of McGill University, a leading expert in the field of multiple sclerosis

- Includes supplementary material: sn.pub/extras

19k Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

- Table of contents

About this book

Editors and affiliations, about the editor, bibliographic information.

- Publish with us

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check for access.

Table of contents (19 chapters)

Front matter, clinically isolated syndrome, optic neuritis.

- Mahtab Ghadiri

Early Multiple Sclerosis

Disease-modifying therapies.

- Anne-Marie Trudelle

Management of relapses with corticosteroids

Established relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, breakthrough disease.

- Chris Eckstein

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Induction therapy, primary progressive multiple sclerosis, diagnosing primary progressive multiple sclerosis.

- Scott D. Newsome

Symptomatic care in primary progressive multiple sclerosis

Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis, diagnosing secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

- Sarah Morrow

Walking disability in multiple sclerosis

Cognitive impairment, pediatric multiple sclerosis and related disorders, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis.

- Sunita Venkateswaran

- Case studies

- Clinically isolated syndrome

- Multiple sclerosis

- Primary progressive multiple sclerosis

- Relapse remitting multiple sclerosis

Paul S. Giacomini

Book Title : Case Studies in Multiple Sclerosis

Editors : Paul S. Giacomini

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31190-6

Publisher : Adis Cham

eBook Packages : Medicine , Medicine (R0)

Copyright Information : Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2017

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-319-31188-3 Published: 21 October 2016

eBook ISBN : 978-3-319-31190-6 Published: 06 October 2016

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XVII, 149

Number of Illustrations : 14 b/w illustrations

Topics : Neurology , Neuroradiology , Primary Care Medicine

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Campus Directory

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

Multiple Sclerosis Case Study

Janet has experienced periodic episodes of tingling in her extremities, dizziness, and even episodes of blindness. After 12 years, doctors have finally given her a diagnosis. Follow Janet through her journey and find out why her disease is so difficult to diagnose.

Module 3: Multiple Sclerosis

Janet, age 22, was preparing for her 6-week postpartum checkup...

MS - Page 1

Three years later, at 34, Janet awoke to a prickly tingling feeling...

MS - Page 2

The neurologist made a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis based on the MRI...

MS - Page 3

Case Summary

Summary of the Case

MS - Summary

Answers to Case Questions

MS - Answers

Professionals

Health Professionals Introduced in Case

MS - Professionals

Additional Links

Optional Links to Explore Further

- Future Leaders in Neurology

- ACTRIMS 2024

- Treating NMOSD: What's Next?

- Conferences

- Publications

Patient Case #1: 37-Year-Old Female With RRMS

- Gabriel Pardo, MD, FAAN

Expert neurologists review treatment options for a young female with relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS).

EP: 1 . Advances in the Management of Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis (RRMS)

EP: 2 . Unmet Needs in the RRMS Treatment Landscape

EP: 3 . Generic Disease-Modifying Therapies (DMTs) in RRMS

Ep: 4 . fda approval process for rrms therapies, ep: 5 . treatment selection in rrms.

EP: 6 . Generic DMTs as First-Line Treatment in RRMS

Ep: 7 . patient case #1: 37-year-old female with rrms, ep: 8 . switching dmts in patients with rrms, ep: 9 . patient case #2: 36-year-old female with rrms with lesions in the spine and brain, ep: 10 . treatment options for a patient with rrms and psoriasis, ep: 11 . use of generic dmts in clinical practice in rrms, ep: 12 . challenges in use of generic dmts for treatment of ms, ep: 13 . the future of rrms treatment, ep: 14 . recommendations for rrms management.

Ahmed Zayed Obeidat MD, PhD: The first case we’re going to talk about is a 37-year-old female with 2 young children. We’re going to talk about some factors about what you would select as a treatment. The patient presented to the neurology clinic for first time with fatigue, weakness, tremors in the right hand, so that’s 1 side. And then medical history was significant for previous numbness and tingling in the lower extremity which was both and the result spontaneously about 2 years ago—not an uncommon scenario where people had maybe a pinched disc or something and they didn’t get medical attention because it went away on a physical exam. She had mild right upper extremity weakness and then increased tone in her right hand, already with increased tone, and some mild intention tremor. That’s important to keep in mind. And then gait was stable but had some hyperreflexia on examination. So those are some of the symptoms she presented with.

You did an MRI, and there were some lesions consistent with demyelination, and then spinal fluid showed unique oligoclonal bands. So, the diagnosis was consistent with what appears to be a relapsing remitting MS [multiple sclerosis].I’ll start with you, Dr Dukkipati. What’s your impression of this case and the initial treatment recommendation? How would you treat this patient?

Ravi Dukkipati, MD: Based on the vignette given, this is a relatively young woman, still of childbearing age with 2 young children, who I’m presuming is fairly active, and by all means has relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis based on the clinical presentation. And the brain MRI demonstrates multiple areas of demyelination, which is concerning, and I would characterize this woman as having a moderate disease burden both clinically and radiographically.

This is the type of patient whom I would not hesitate in terms of being aggressive from the beginning because the concern is that time is brain matter. And so, I generally don’t start new patients on platform therapies any longer, so the real decision-making in my mind would be between one of the oral therapies vs monoclonal antibodies with a patient like this or natalizumab.

Ahmed Zayed Obeidat MD, PhD: Dr Pardo?

Gabriel Pardo, MD, FAAN: Yes, I completely agree. I think there are some concerning signs already in this patient. I assume she’s right-hand dominant just by statistics and that’s where she has most of her symptoms. She already has dexterity problems spasticity problems weakness problems, and it’s not harboring good things for the future. The burden of disease seems to be high, and the diagnosis is straightforward. So, I am concerned about this patient. I think that there is no time to waste with platform therapies; there is no doubt about that.

Other elements we were discussing to individualize the decision-making along with the patient will be, as Dr Dukkipati mentioned, as she is still of childbearing age, is she planning on having more children? That will be a very important aspect in the counseling of this patient regarding the selection of the different agents that we have. And each one of them will have different characteristics in that regard. Some of them will allow her to be treated with 4 courses and then be free of treatment if she is able to delay pregnancy for 2 years, for example, maybe 2½ years 1½ years, or 18 months. Or she might imply the decision of having to stop treatment to pursue pregnancy with the risk of a potential rebound if she does not become pregnant promptly. So, a lot of elements again become important in individual patients, and for this patient, we’ll have to get that in the conversation to be able to counsel her in addition. But from the get-go, I am concerned about the patient, and she should definitely be on high-efficacy therapies. There’s no time to beat around the bush.

Ahmed Zayed Obeidat MD, PhD: Yes, and I agree because as you mentioned, there are already signs of incomplete recovery. There are signs of maybe brain stem involvement here, right? There’s a tremor, there is maybe cerebellar involvement. And that’s concerning when we think about her young age and that it was previously untreated for probably over 2 years because the first episode was over 2 years ago with what appears to be transgressed myelitis, which is again another spinal cord involvement which carries a poor prognosis sometimes. So I would do the same. I would start with a highly effective therapy for her. And then maybe, again, considering other factors; when she wants, if she wants more children, when the plan is. And we’ll work around many of these factors.

So I’m going to tell you a little bit of what happened. Maybe she was not started on highly effective therapy. So despite receiving disease-modifying therapy [DMT], she had 2 more relapses in the past year. She reported increased fatigue, difficulty with memory and concentration. And her exam showed right-sided weakness and wrist reflexes are still there, but more weakness. Another MRI of the brain shows multiple new and enhancing lesions while on a disease-modifying therapy, suggestive of ongoing disease activity. Her fatigue and memory issues are interfering with job performance. Now her symptoms are starting to affect her day-to-day and then maybe threatening her job or maybe could result in her losing her job. So this is now even more concerning. So now the patient comes back to you and asks, “How would you monitor? How would you treat me? What else can I do?" Dr Dukkipati, I’ll start with you for this one now, and then we’ll see what Dr Pardo has to say.

Ravi Dukkipati, MD: Well, this is clearly the worst-case scenario, what we had talked about earlier. This woman unfortunately is progressing. Clinically she’s had several relapses. She’s exhibiting signs of progression and her MRI studies clearly demonstrate a very active disease, involving both the brain and the spinal cord. Now, we don’t necessarily know what her initial disease-modifying therapy was, but clearly, she’s failing with that initial therapy. And this patient would need close monitoring both clinically and radiographically and imminent or immediate change or escalation of therapy to a different class.

Ahmed Zayed Obeidat MD, PhD: Dr Pardo, do you agree, and do you have any other additional thoughts?

Gabriel Pardo, MD, FAAN: Absolutely. I agree completely. And just this case highlights the fact that in addition to our selection of the disease-modifying therapy, we need to be always in tune with the patient’s needs and the fact that MS is multifaceted, it has a lot of manifestations, and that it does require comprehensive management of the disease. We need to go beyond the selection of the DMT. We need to explore all these other possibilities.

The threat of potentially losing her job has tremendous social, familial, and personal implications. And it brings then the conversation of the complementary things that we do to the DMTs, which are symptom management and trying to improve function, something that we also need to monitor closely. It is not just the markers that we use for failing a treatment as clearly evident in this case with relapses, and new MRI additions, but all these other ancillary ways of assessing how the patient is functioning and what else should we do, and can we do to improve that function, and to improve the ability of the patient to continue to live their life the best they can?

Ahmed Zayed Obeidat MD, PhD: Yes, and what strikes me in this case is also that she had 2 relapses in the past year, so she was left to relapse again after 1 relapse. So we didn’t have to even wait for that, right? You see 1 relapse, and for me, it’s sufficient to just switch to a different mechanism of action, and in this case, perhaps going higher; something with known higher efficacy.

Transcript edited for clarity

Episode 112: Exploring Dimethyl Fumarate to Treat Friedreich Ataxia

NeurologyLive® Friday 5 — April 5, 2024

Episode 111: Reviewing ACTRIMS 2024

NeuroVoices: Francesco Saccà, MD, PhD, on Crossing Over Dimethyl Fumarate in Friedriech Ataxia

Kyverna Publishes Promising First Case Reports of CAR-T Cell Therapy in Progressive Multiple Sclerosis

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

- Open access

- Published: 10 April 2024

“So at least now I know how to deal with things myself, what I can do if it gets really bad again”—experiences with a long-term cross-sectoral advocacy care and case management for severe multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study

- Anne Müller ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2456-2492 1 ,

- Fabian Hebben ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0003-6401-3433 1 ,

- Kim Dillen 1 ,

- Veronika Dunkl 1 ,

- Yasemin Goereci 2 ,

- Raymond Voltz 1 , 3 , 4 ,

- Peter Löcherbach 5 ,

- Clemens Warnke ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3510-9255 2 &

- Heidrun Golla ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4403-630X 1

on behalf of the COCOS-MS trial group represented by Martin Hellmich

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 453 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Persons with severe Multiple Sclerosis (PwsMS) face complex needs and daily limitations that make it challenging to receive optimal care. The implementation and coordination of health care, social services, and support in financial affairs can be particularly time consuming and burdensome for both PwsMS and caregivers. Care and case management (CCM) helps ensure optimal individual care as well as care at a higher-level. The goal of the current qualitative study was to determine the experiences of PwsMS, caregivers and health care specialists (HCSs) with the CCM.

In the current qualitative sub study, as part of a larger trial, in-depth semi-structured interviews with PwsMS, caregivers and HCSs who had been in contact with the CCM were conducted between 02/2022 and 01/2023. Data was transcribed, pseudonymized, tested for saturation and analyzed using structuring content analysis according to Kuckartz. Sociodemographic and interview characteristics were analyzed descriptively.

Thirteen PwsMS, 12 caregivers and 10 HCSs completed interviews. Main categories of CCM functions were derived deductively: (1) gatekeeper function, (2) broker function, (3) advocacy function, (4) outlook on CCM in standard care. Subcategories were then derived inductively from the interview material. 852 segments were coded. Participants appreciated the CCM as a continuous and objective contact person, a person of trust (92 codes), a competent source of information and advice (on MS) (68 codes) and comprehensive cross-insurance support (128 codes), relieving and supporting PwsMS, their caregivers and HCSs (67 codes).

Conclusions

Through the cross-sectoral continuous support in health-related, social, financial and everyday bureaucratic matters, the CCM provides comprehensive and overriding support and relief for PwsMS, caregivers and HCSs. This intervention bears the potential to be fine-tuned and applied to similar complex patient groups.

Trial registration

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Cologne (#20–1436), registered at the German Register for Clinical Studies (DRKS00022771) and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most frequent and incurable chronic inflammatory and degenerative disease of the central nervous system (CNS). Illness awareness and the number of specialized MS clinics have increased since the 1990s, paralleled by the increased availability of disease-modifying therapies [ 1 ]. There are attempts in the literature for the definition of severe MS [ 2 , 3 ]. These include a high EDSS (Expanded disability Status Scale [ 4 ]) of ≥ 6, which we took into account in our study. There are also other factors to consider, such as a highly active disease course with complex therapies that are associated with side effects. These persons are (still) less disabled, but may feel overwhelmed with regard to therapy, side effects and risk monitoring of therapies [ 5 , 6 ].

Persons with severe MS (PwsMS) develop individual disease trajectories marked by a spectrum of heterogeneous symptoms, functional limitations, and uncertainties [ 7 , 8 ] manifesting individually and unpredictably [ 9 ]. This variability can lead to irreversible physical and mental impairment culminating in complex needs and daily challenges, particularly for those with progressive and severe MS [ 5 , 10 , 11 ]. Such challenges span the spectrum from reorganizing biographical continuity and organizing care and everyday live, to monitoring disease-specific therapies and integrating palliative and hospice care [ 5 , 10 ]. Moreover, severe MS exerts a profound of social and economic impact [ 9 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. PwsMS and their caregivers (defined in this manuscript as relatives or closely related individuals directly involved in patients’ care) often find themselves grappling with overwhelming challenges. The process of organizing and coordinating optimal care becomes demanding, as they contend with the perceived unmanageability of searching for, implementing and coordinating health care and social services [ 5 , 15 , 16 , 17 ].

Case management (CM) proved to have a positive effect on patients with neurological disorders and/or patients with palliative care needs [ 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ]. However, a focus on severe MS has been missed so far Case managers primarily function as: (1) gatekeeper involving the allocation of necessary and available resources to a case, ensuring the equitable distribution of resources; as (2) broker assisting clients in pursuing their interests, requiring negotiation to provide individualized assistance that aligns as closely as possible with individual needs and (3) advocate working to enhance clients’ individual autonomy, to advocate for essential care offers, and to identify gaps in care [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ].

Difficulties in understanding, acting, and making decisions regarding health care-related aspects (health literacy) poses a significant challenge for 54% of the German population [ 30 ]. Additionally acting on a superordinate level as an overarching link, a care and case management (CCM) tries to reduce disintegration in the social and health care system [ 31 , 32 ]. Our hypothesis is that a CCM allows PwsMS and their caregivers to regain time and resources outside of disease management and to facilitate the recovery and establishment of biographical continuity that might be disrupted due to severe MS [ 33 , 34 ].

Health care specialists (HCSs) often perceive their work with numerous time and economic constraints, especially when treating complex and severely ill individuals like PwsMS and often have concerns about being blamed by patients when expectations could not be met [ 35 , 36 ]. Our hypothesis is that the CCM will help to reduce time constraints and free up resources for specialized tasks.

To the best of our knowledge there is no long-term cross-sectoral and outreaching authority or service dedicated to assisting in the organization and coordination of the complex care concerns of PwsMS within the framework of standard care addressing needs in health, social, financial, every day and bureaucratic aspects. While some studies have attempted to design and test care programs for persons with MS (PwMS), severely affected individuals were often not included [ 37 , 38 , 39 ]. They often remain overlooked by existing health and social care structures [ 5 , 9 , 15 ].

The COCOS-MS trial developed and applied a long-term cross-sectoral CCM intervention consisting of weekly telephone contacts and monthly re-assessments with PwsMS and caregivers, aiming to provide optimal care. Their problems, resources and (unmet) needs were assessed holistically including physical health, mental health, self-sufficiency and social situation and participation. Based on assessed (unmet) needs, individual care plans with individual actions and goals were developed and constantly adapted during the CCM intervention. Contacts with HCSs were established to ensure optimal care. The CCM intervention was structured through and documented in a CCM manual designed for the trial [ 40 , 41 ].

Our aim was to find out how PwsMS, caregivers and HCSs experienced the cross-sectoral long-term, outreaching patient advocacy CCM.

This study is part of a larger phase II, randomized, controlled clinical trial “Communication, Coordination and Security for people with severe Multiple Sclerosis (COCOS-MS)” [ 41 ]. This explorative clinical trial, employing a mixed-method design, incorporates a qualitative study component with PwsMS, caregivers and HCSs to enrich the findings of the quantitative data. This manuscript focuses on the qualitative data collected between February 2022 and January 2023, following the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines [ 42 ].

Research team

Three trained authors AM, KD and FH (AM, female, research associate, M.A. degree in Rehabilitation Sciences; KD, female, researcher, Dr. rer. medic.; FH, male, research assistant, B.Sc. degree in Health Care Management), who had no prior relationship with patients, caregivers or HCSs conducted qualitative interviews. A research team, consisting of clinical experts and health services researchers, discussed the development of the interview guides and the finalized category system.

Theoretical framework

Interview data was analyzed with the structuring content analysis according to Kuckartz. This method enables a deductive structuring of interview material, as well as the integration of new aspects found in the interview material through the inductive addition of categories in an iterative analysis process [ 43 ].

Sociodemographic and interview characteristics were analyzed descriptively (mean, median, range, SD). PwsMS, caregivers and HCSs were contacted by the authors AM, KD or FH via telephone or e-mail after providing full written informed consent. Participants had the option to choose between online interviews conducted via the GoToMeeting 10.19.0® Software or face-to-face. Peasgood et al. (2023) found no significant differences in understanding questions, engagement or concentration between face-to-face and online interviews [ 44 , 45 ]. Digital assessments were familiar to participants due to pandemic-related adjustments within the trial.

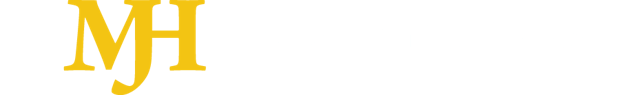

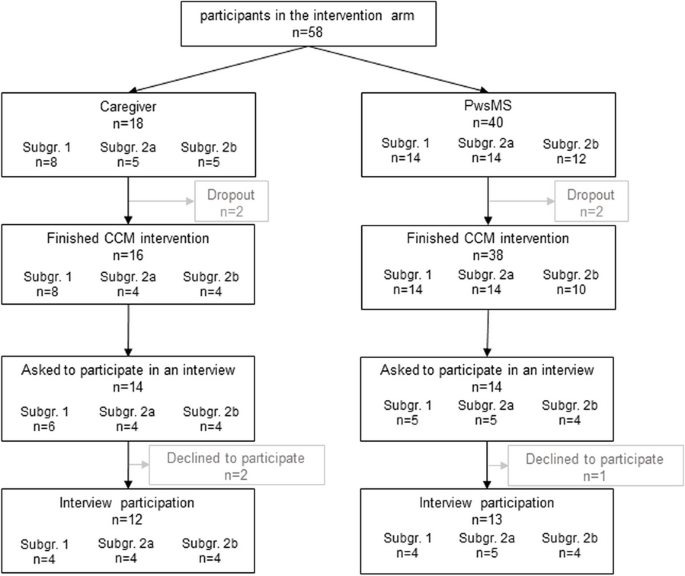

Out of 14 PwsMS and 14 caregivers who were approached to participate in interviews, three declined to complete interviews, resulting in 13 PwsMS (5 male, 8 female) and 12 caregiver (7 male, 5 female) interviews, respectively (see Fig. 1 ). Thirty-one HCSs were contacted of whom ten (2 male, 8 female) agreed to be interviewed (see Fig. 2 ).

Flowchart of PwsMS and caregiver participation in the intervention group of the COCOS-MS trial. Patients could participate with and without a respective caregiver taking part in the trial. Therefore, number of caregivers does not correspond to patients. For detailed inclusion criteria see also Table 1 in Golla et al. [ 41 ]

Flowchart of HCSs interview participation

Setting and data collection

Interviews were carried out where participants preferred, e.g. at home, workplace, online, and no third person being present. In total, we conducted 35 interviews whereof 7 interviews face-to-face (3 PwsMS, 3 caregivers, 1 HCS).

The research team developed a topic guide which was meticulously discussed with research and clinical staff to enhance credibility. It included relevant aspects for the evaluation of the CCM (see Tables 1 and 2 , for detailed topic guides see Supplementary Material ). Patient and caregiver characteristics (covering age, sex, marital status, living situation, EDSS (patients only), subgroup) were collected during the first assessment of the COCOS-MS trial and HCSs characteristics (age, sex, profession) as well as interview information (length and setting) were collected during the interviews. The interview guides developed for this study addressed consistent aspects both for PwsMS and caregivers (see Supplementary Material ):

For HCSs it contained the following guides:

Probing questions were asked to get more specific and in-depth information. Interviews were carried out once and recorded using a recording device or the recording function of the GoToMeeting 10.19.0® Software. Data were pseudonymized (including sensitive information, such as personal names, dates of birth, or addresses), audio files were safely stored in a data protection folder. The interview duration ranged from 11 to 56 min (mean: 23.9 min, SD: 11.1 min). Interviews were continued until we found that data saturation was reached. Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by an external source and not returned to participants.

Data analysis

Two coders (AM, FH) coded the interviews. Initially, the first author (AM) thoroughly reviewed the transcripts to gain a sense of the interview material. Using the topic guide and literature, she deductively developed a category system based on the primary functions of CM [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Three interviews were coded repeatedly for piloting, and inductive subcategories were added when new themes emerged in the interview material. This category system proved suitable for the interview material. The second coder (FH) familiarized himself with the interview material and category system. Both coders (AM, FH) independently coded all interviews, engaging in discussions and adjusting codes iteratively. The finalized category system was discussed and consolidated in a research workshop and within the COCOS-MS trial group and finally we reached an intercoder agreement of 90% between the two coders AM and FH, computed by the MAXQDA Standard 2022® software.

We analyzed sociodemographic and interview characteristics using IBM SPSS Statistics 27® and Excel 2016®. Transcripts were managed and analyzed using MAXQDA Standard 2022®.

Participants were provided with oral and written information about the trial and gave written informed consent. Ethical approvals were obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Cologne (#20–1436). The trial is registered in the German Register for Clinical Studies (DRKS) (DRKS00022771) and is conducted under the Declaration of Helsinki.

Characteristics of participants and interviews

PwsMS participating in an interview were mainly German (84.6%), had a mean EDSS of 6.8 (range: 6–8) and MS for 13.5 years (median: 14; SD: 8.1). For detailed characteristics see Table 3 .

Most of the interviewed caregivers (9 caregivers) were the partners of the PwsMS with whom they lived in the same household. For further details see Table 3 .

HCSs involved in the study comprised various professions, including MS-nurse (3), neurologist (2), general physician with further training in palliative care (1), physician with further training in palliative care and pain therapist (1), housing counselling service (1), outpatient nursing service manager (1), participation counselling service (1).

Structuring qualitative content analysis

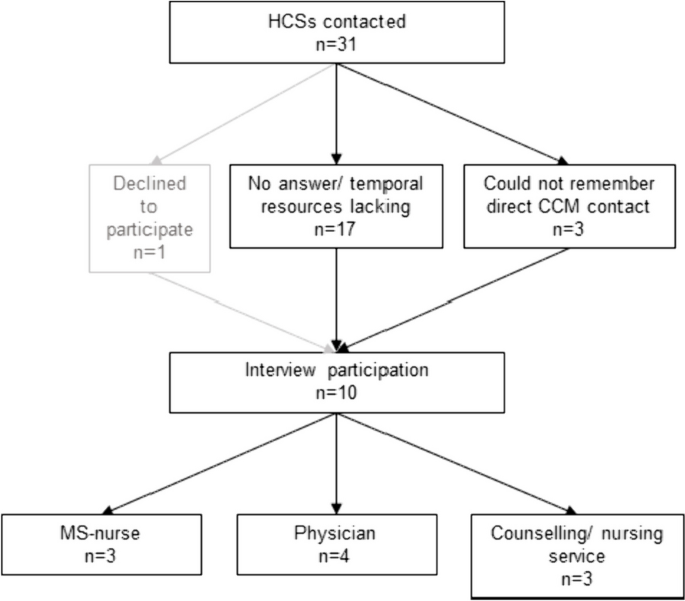

The experiences of PwsMS, caregivers and HCSs were a priori deductively assigned to four main categories: (1) gatekeeper function, (2) broker function, (3) advocacy function [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ] and (4) Outlook on CCM in standard care, whereas the subcategories were developed inductively (see Fig. 3 ).

Category system including main and subcategories of the qualitative thematic content analysis

The most extensive category, housing the highest number of codes and subcodes, was the “ Outlook on CCM in standard care ” (281 codes). Following this, the category “ Advocacy Function ” contained 261 codes. The “ Broker Function ” (150 codes) and the “ Gatekeeper Function ” (160 codes) constituted two smaller categories. The majority of codes was identified in the caregivers’ interviews, followed by those of PwsMS (see Table 4 ). Illustrative quotes for each category and subcategory can be found in Table 5 .

Persons with severe multiple sclerosis

In the gatekeeper function (59 codes), PwsMS particularly valued the CCM as a continuous contact person . They appreciated the CCM as a person of trust who was reliably accessible throughout the intervention period. This aspect, with 41 codes, held significant importance for PwsMS.

Within the broker function (44 codes), establishing contact was most important for PwsMS (22 codes). This involved the CCM as successfully connecting PwsMS and caregivers with physicians and therapists, as well as coordinating and arranging medical appointments, which were highly valued. Assistance in authority and health and social insurance matters (10 codes) was another subcategory, where the CCM encompassed support in communication with health insurance companies, such as improving the level of care, assisting with retirement pension applications, and facilitating rehabilitation program applications. Optimized care (12 codes) resulted in improved living conditions and the provision of assistive devices through the CCM intervention.

The advocacy function (103 codes) emerged as the most critical aspect for PwsMS, representing the core of the category system. PwsMS experienced multidimensional, comprehensive, cross-insurance system support from the CCM. This category, with 43 statements, was the largest within all subcategories. PwsMS described the CCM as addressing their concerns, providing help, and assisting with the challenges posed by the illness in everyday life. The second-largest subcategory, regaining, maintaining and supporting autonomy (25 codes), highlighted the CCM’s role in supporting self-sufficiency and independence. Reviving personal wellbeing (17 codes) involved PwsMSs’ needs of regaining positive feelings, improved quality of life, and a sense of support and acceptance, which could be improved by the CCM. Temporal relief (18 codes) was reported, with the CCM intervention taking over or reducing tasks.

Within the outlook on CCM in standard care (84 codes), eight subcategories were identified. Communications was described as friendly and open (9 codes), with the setting of communication (29 codes) including the frequency of contacts deemed appropriate by the interviewed PwsMS, who preferred face-to-face contact over virtual or telephone interactions. Improvement suggestions for CCM (10 codes) predominantly revolved around the desire for the continuation of the CCM beyond the trial, expressing intense satisfaction with the CCM contact person and program. PwsMS rarely wished for better cooperation with the CCM. With respect to limitations (7 codes), PwsMS distinguished between individual limitations (e.g. when not feeling ready for using a wheelchair) and overriding structural limitations (e.g. unsuccessful search for an accessible apartment despite CCM support). Some PwsMS mentioned needing the CCM earlier in the course of the disease and believed it would beneficial for anyone with a chronic illness (6 codes).

In the gatekeeper function (75 codes), caregivers highly valued the CCM as a continuous contact partner (33 codes). More frequently than among the PwsMS interviewed, caregivers valued the CCM as a source of consultation/ information on essential individual subjects (42 codes). The need for basic information about the illness, its potential course, treatment and therapy options, possible supportive equipment, and basic medical advice/ information could be met by the CCM.

Within the broker function (63 codes), caregivers primarily experienced the subcategory establish contacts (24 codes). They found the CCM as helpful in establishing and managing contact with physicians, therapists and especially with health insurance companies. In the subcategory assistance in authority and health and social insurance matters (22 codes), caregivers highlighted similar aspects as the PwsMS interviewed. However, there was a particular emphasis on assistance with patients' retirement matters. Caregivers also valued the optimization of patients’ care and living environment (17 codes) in various life areas during the CCM intervention, including improved access to assistive devices, home modification, and involvement of a household support and/ or nursing services.

The advocacy function, with 115 codes, was by far the broadest category . The subcategory multidimensional, comprehensive, cross-insurance system support represented the largest subcategory of caregivers, with 70 statements. In summary, caregivers felt supported by the CCM in all domains of life. Regaining, maintaining and supporting autonomy (11 codes) and reviving personal wellbeing (8 codes) in the form of an improved quality of life played a role not only for patients but also for caregivers, albeit to a lower extend. Caregivers experienced temporal relief (26 codes) as the CCM undertook a wide range of organizational tasks, freeing up more needed resources for their own interests.

For the Outlook on CCM in standard care , caregivers provided various suggestions (81 codes). Similar to PwsMS, caregivers felt that setting (home based face-to-face, telephone, virtual) and frequency of contact were appropriate (10 codes, communication setting ) and communications (7 codes) were recognized as open and friendly. However, to avoid conflicts between caregiver and PwsMS, caregivers preferred meeting the CCM separately from the PwsMS in the future. Some caregivers wished the CCM to specify all services it might offer at the beginning, while others emphasized not wanting this. Like PwsMS, caregivers criticized the CCM intervention being (trial-related) limited to one year, regardless of whether further support was needed or processes being incomplete (13 codes, improvement suggestions ). After the CCM intervention time had expired, the continuous contact person and assistance were missed and new problems had arisen and had to be managed with their own resources again (9 codes, effects of CCM discontinuation ), which was perceived as an exhausting or unsolvable endeavor. Caregivers identified analogous limitations (8 codes), both individual and structural. However, the largest subcategory, was the experienced potential of CCM (27 codes), reflected in extremely high satisfaction with the CCM intervention. Like PwsMS, caregivers regarded severe chronically ill persons in general as target groups for a CCM (7 codes) and would implement it even earlier, starting from the time of diagnosis. They considered a CCM to be particularly helpful for patients without caregivers or for caregivers with limited (time) resources, as it was true for most caregivers.

Health care specialists

In the gatekeeper function (26 codes) HCSs particularly valued the CCM as a continuous contact partner (18 codes). They primarily described their valuable collaboration with the CCM, emphasizing professional exchange between the CCM and HCSs.

Within the broker function (43 codes), the CCM was seen as a connecting link between patients and HCSs, frequently establishing contacts (18 codes). This not only improved optimal care on an individual patient level (case management) but also at a higher, superordinate care level (care management). HCSs appreciated the optimized care and living environment (18 codes) for PwsMS, including improved medical and therapeutic access and the introduction of new assistive devices. The CCM was also recognized as providing assistance in authority and health and social matters (7 codes) for PwsMS and their caregivers.

In the advocacy function (43 codes), HCSs primarily reported temporal relief through CCM intervention (23 codes). They experienced this relief, especially as the CCM provided multidimensional, comprehensive, and cross-insurance system support (15 codes) for PwsMS and their caregivers. Through this support, HCSs felt relieved from time intensive responsibilities that may not fall within their area of expertise, freeing up more time resources for their actual professional tasks.

The largest category within the HCSs interviews was the outlook on CCM in standard care (116 codes). In the largest subcategory, HCSs made suggestions for further patient groups who could benefit (38 codes) from a CCM. Chronic neurological diseases like neurodegenerative diseases (e.g. amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), typical and atypical Parkinson syndromes were mentioned. HCSs considered the enrollment of the CCM directly after the diagnosis of these complex chronic diseases. Additionally, chronic progressive diseases in general or oncological diseases, which may also run chronically, were regarded worthwhile for this approach. HCSs also provided suggestions regarding improvement (21 codes). They wished e.g. for information or contact when patients were enrolled to the CCM, regular updates, exchange and collaborative effort. On the other hand, HCSs reported, that their suggestions for improvement would hardly be feasible due to their limited time resources. Similar to patients and caregivers, HCSs experienced structural limits (13 codes), which a CCM could not exceed due to overriding structural limitations (e.g. insufficient supply of (household) aids, lack of outreach services like psychotherapists, and long processing times on health and pension insurers' side). HCSs were also asked about their opinions on financial resources (14 codes) of a CCM in standard care. All interviewed HCSs agreed that CCM would initially cause more costs for health and social insurers, but they were convinced of cost savings in the long run. HCSs particularly perceived the potential of the CCM (20 codes) through the feedback of PwsMS, highlighting the trustful relationship enabling individualized help for PwsMS and their caregivers.

Persons with severe multiple sclerosis and their caregivers

The long-term cross-sectoral CCM intervention implemented in the COCOS-MS trial addressed significant unmet needs of PwsMS and their caregivers which previous research revealed as burdensome and hardly or even not possible to improve without assistance [ 5 , 6 , 9 , 10 , 33 , 35 , 46 ]. Notably, the CCM service met the need for a reliable, continuous contact partner, guiding patients through the complexities of regulations, authorities and the insurance system. Both, PwsMS and their caregivers highly valued the professional, objective perspective provided by the CCM, recognizing it as a source of relief, support and improved care in line with previous studies [ 37 , 47 ]. Caregivers emphasized the CCM’s competence in offering concrete assistance and information on caregiving and the fundamentals of MS, including bureaucratic, authority and insurances matters. On the other hand, PwsMS particularly appreciated the CCMs external reflective and advisory function, along with empathic social support tailored to their individual concerns. Above all, the continuous partnership of trust, available irrespective of the care sector, was a key aspect that both PwsMS and their caregivers highlighted. This consistent support was identified as one of the main components in the care of PwsMS in previous studies [ 5 , 33 , 35 ].

As the health literacy is inadequate or problematic for 54% of the German population and disintegration in the health and social care system is high [ 30 , 31 , 32 ], the CCM approach serves to enhance health literacy and reduce disintegration of PwsMS and their caregivers by providing cross-insurance navigational guidance in the German health and social insurance sector on a superordinate level. Simultaneously PwsMS and caregivers experienced relief and gained more (time) resources for all areas of life outside of the disease and its management, including own interests and establishing biographical continuity. This empowerment enables patients to find a sense of purpose beyond their illness, regain autonomy, and enhance social participation, reducing the feeling of being a burden to those closest to them. Such feelings are often experienced as burdensome and shameful by PwsMS [ 6 , 48 , 49 , 50 ]. Finding a sense of purpose beyond the illness also contributes to caregivers perceiving their loved ones not primarily as patient but as individuals outside of the disease, reinforcing valuable relationships such as partners, siblings, or children, strengthening emotional bonds. These factors are also highly relevant and well-documented in a suicide-preventive context, as the suicide rate is higher in persons diagnosed with neurological disorders [ 19 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ] and the feeling of being a burden to others, loss of autonomy, and perceived loss of dignity are significant factors in patients with severe chronic neurological diseases for suicide [ 50 , 57 ].

The temporal relief experienced by the CCM was particularly significant for HCSs and did not only improve the satisfaction of HCSs but also removed unfulfilled expectations and concerns about being blamed by patients when expectations could not be met, which previous studied elaborated [ 35 , 36 ]. Moreover, the CCM alleviated the burden on HCSs by addressing patients’ concerns, allowing them to focus on their own medical responsibilities. This aspect probably reduced the dissatisfaction that arises when HCSs are expected to address issues beyond their medical expertise, such as assistive devices, health and social insurance, and the organization and coordination of supplementary therapies, appointments, and contacts [ 35 , 36 , 61 ]. Consequently, the CCM reduced difficulties of HCSs treating persons with neurological or chronical illnesses, which previous research identified as problematic.

HCSs perceive their work as increasingly condensed with numerous time and economic constraints, especially when treating complex and severely ill individuals like PwsMS [ 36 ]. This constraint was mentioned by HCSs in the interviews and was one of the main reasons why they were hesitant to participate in interviews and may also be an explanation for a shorter interview duration than initially planned in the interview guides. The CCM’s overarching navigational competence in the health and social insurance system was particularly valued by HCSs. The complex and often small-scale specialties in the health and social care system are not easily manageable or well-known even for HCSs, and dealing with them can exceed their skills and time capacities [ 61 ]. The CCM played a crucial role in keeping (temporal) resources available for what HCSs are professionally trained and qualified to work on. However, there remains a challenge in finding solutions to the dilemma faced by HCSs regarding their wish to be informed about CCM procedures and linked with each other, while also managing the strain of additional requests and contact with the CCM due to limited (time) resources [ 62 ]. Hudon et al. (2023) suggest that optimizing time resources and improving exchange could involve meetings, information sharing via fax, e-mail, secure online platforms, or, prospectively, within the electronic patient record (EPR). The implementation of an EPR has shown promise in improving the quality of health care and time resources, when properly implemented [ 63 , 64 ]. The challenge lies ineffective information exchange between HCSs and CCM for optimal patient care. The prospect of time saving in the long run and at best for a financial incentive, e.g., when anchoring in the Social Security Code, will help best to win over the HCSs.If this crucial factor can be resolved, there is a chance that HCSs will thoroughly accept the CCM as an important pillar, benefiting not only PwsMS but also other complex patient groups, especially those with long-term neurological or complex oncological conditions that might run chronically.

Care and case management and implications for the health care system

The results of our study suggest that the cross-sectoral long-term advocacy CCM in the COCOS-MS trial, with continuous personal contacts at short intervals and constant reevaluation of needs, problems, resources and goals, is highly valued by PwsMS, caregivers, and HCSs. The trial addresses several key aspects that may have been overlooked in previous studies which have shown great potential for the integration of case management [ 17 , 47 , 62 , 65 , 66 ]. However, they often excluded the overriding care management, missed those patient groups with special severity and complexity who might struggle to reach social and health care structures independently or the interventions were not intended for long-term [ 22 , 37 ]. Our results indicate that the CCM intervention had a positive impact on PwsMS and caregivers as HCSs experienced them with benefits such as increased invigoration, reduced demands, and enhanced self-confidence. However, there was a notable loss experienced by PwsMS and caregivers after the completion of the CCM intervention, even if they had stabilized during the intervention period. The experiences of optimized social and health care for the addressed population, both at an individual and superordinate care level, support the integration of this service into standard care. Beyond the quantitatively measurable outcomes and economic considerations reported elsewhere [ 16 , 20 , 21 ], our results emphasize the importance of regaining control, self-efficacy, self-worth, dignity, autonomy, and social participation. These aspects are highlighted as preventive measures in suicidal contexts, which is particularly relevant for individuals with severe and complex illnesses [ 19 , 50 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ]. Our findings further emphasize the societal responsibilities to offer individuals with severe and complex illnesses the opportunity to regain control and meaningful aspects of life, irrespective of purely economic considerations. This underscores the need for a comprehensive evaluation that not only takes into account quantitative measures but also the qualitative aspects of well-being and quality of life when making recommendations of a CCM in standard care.

The study by J. Y. Joo and Huber (2019) highlighted that CM interventions aligned with the standards of the Case Management Society of America varied in duration, ranging from 1 month to 15.9 years, and implemented in community- or hospital-based settings. However, they noted a limitation in understanding how CM processes unfold [ 67 ]. In contrast, our trial addressed this criticism by providing transparent explanations of the CCM process, which also extends to a superordinate care management [ 40 , 41 ]. Our CCM manual [ 40 ] outlines a standardized and structured procedure for measuring and reevaluating individual resources, problems, and unmet needs on predefined dimensions. It also identifies goals and actions at reducing unmet needs and improving the individual resources of PwsMS and caregivers. Importantly, the CCM manual demonstrates that the CCM process can be structured and standardized, while accounting for the unique aspects of each individual’s serious illness, disease courses, complex needs, available resources, and environmental conditions. Furthermore, the adaptability of the CCM manual to other complex chronically ill patient groups suggests the potential for a standardized approach in various health care settings. This standardized procedure allows for consistency in assessing and addressing the individual needs of patients, ensuring that the CCM process remains flexible while maintaining a structured and goal-oriented framework.

The discussion about the disintegration in the social and health care system and the increasing specialization dates back to 2009 [ 31 , 32 ]. Three strategies were identified to address this issue: (a) “driver-minimizing” [Treiberminimierende], (b) “effect-modifying” [Effektmodifizierende] and (c) “disintegration-impact-minimizing” [Desintegrationsfolgenminimierende] strategies. “Driver-minimizing strategies” involve comprehensive and radical changes within the existing health and social care system, requiring political and social pursuit. “Disintegration-impact-minimizing strategies” are strategies like quality management or tele-monitoring, which are limited in scope and effectiveness. “Effect-modifying strategies”, to which CCM belongs, acknowledges the segmentation within the system but aims to overcome it through cooperative, communicative, and integrative measures. CCM, being an “effect-modifying strategy”, operates the “integrated segmentation model” [Integrierte Segmentierung] rather than the “general contractor model” [Generalunternehmer-Modell] or “total service provider model” [Gesamtdienstleister-Modell] [ 31 , 32 ]. In this model, the advantage lies in providing an overarching and coordinating service to link different HCSs and services cross-sectorally. The superordinate care management aspect of the CCM plays a crucial role in identifying gaps in care, which is essential for future development strategies within the health and social care system. It aims to find or develop (regional) alternatives to ensure optimal care [ 17 , 23 , 24 , 68 , 69 ], using regional services of existing health and social care structures. Therefore, superordinate care management within the CCM process is decisive for reducing disintegration in the system.

Strengths and limitations

The qualitative study results of the explorative COCOS-MS clinical trial, which employed an integrated mixed-method design, provide valuable insights into the individual experiences of three leading stakeholders: PwsMS, caregivers and HCSs with a long-term cross-sectoral CCM. In addition to in-depth interviews, patient and caregiver reported outcome measurements were utilized and will be reported elsewhere. The qualitative study’s strengths include the inclusion of patients who, due to the severity of their condition (e.g. EDSS mean: 6.8, range: 6–8, highly active MS), age (mean: 53.9 years, range: 36–73 years) family constellations, are often underrepresented in research studies and often get lost in existing social and health care structures. The study population is specific to the wider district region of Cologne, but the broad inclusion criteria make it representative of severe MS in Germany. The methodological approach of a deductive and inductive structuring content analysis made it possible to include new findings into an existing theoretical framework.

However, the study acknowledges some limitations. While efforts were made to include more HCSs, time constraints on their side limited the number of interviews conducted and might have biased the results. Some professions are underrepresented in the interviews. Complex symptoms (e.g. fatigue, ability to concentrate), medical or therapeutic appointments and organization of the everyday live may have been reasons for the patients’ and caregivers’ interviews lasting shorter than initially planned.

The provision of functions of a CCM, might have pre-structured the answers of the participants.

At current, there is no support system for PwsMS, their caregivers and HCSs that addresses their complex and unmet needs comprehensively and continuously. There are rare qualitative insights of the three important stakeholders: PwsMS, caregivers and HCSs in one analysis about a supporting service like a CCM. In response to this gap, we developed and implemented a long-term cross-sectoral advocacy CCM and analyzed it qualitatively. PwsMS, their caregivers and HCSs expressed positive experiences, perceiving the CCM as a source of relief and support that improved care across various aspects of life. For patients, the CCM intervention resulted in enhanced autonomy, reviving of personal wellbeing and new established contacts with HCSs. Caregivers reported a reduced organizational burden and felt better informed, and HCSs experienced primarily temporal relief, allowing them to concentrate on their core professional responsibilities. At a higher level of care, the study suggests that the CCM contributed to a reduction in disintegration within the social and health care system.

The feedback from participants is seen as valuable for adapting the CCM intervention and the CCM manual for follow-up studies, involving further complex patient groups such as neurological long-term diseases apart from MS and tailoring the duration of the intervention depending on the complexity of evolving demands.

Availability of data and materials

Generated and/or analyzed datasets of participants are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request to protect participants. Preliminary partial results have been presented as a poster during the EAPC World Congress in June 2023 and the abstract has been published in the corresponding abstract booklet [ 70 ].

Abbreviations

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Care and case management

Case management

Central nervous system

Communication, Coordination and security for people with multiple sclerosis

Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research

German register for clinical studies

Extended disability status scale

Electronic patient record

Quality of life

Multiple sclerosis

Koch-Henriksen N, Magyari M. Apparent changes in the epidemiology and severity of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17:676–88. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-021-00556-y .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ellenberger D, Flachenecker P, Fneish F, Frahm N, Hellwig K, Paul F, et al. Aggressive multiple sclerosis: a matter of measurement and timing. Brain. 2020;143:e97. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaa306 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Edmonds P, Vivat B, Burman R, Silber E, Higginson IJ. Loss and change: experiences of people severely affected by multiple sclerosis. Palliat Med. 2007;21:101–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216307076333 .

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: An expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33(11):1444–52.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Galushko M, Golla H, Strupp J, Karbach U, Kaiser C, Ernstmann N, et al. Unmet needs of patients feeling severely affected by multiple sclerosis in Germany: a qualitative study. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:274–81. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0497 .

Borreani C, Bianchi E, Pietrolongo E, Rossi I, Cilia S, Giuntoli M, et al. Unmet needs of people with severe multiple sclerosis and their carers: qualitative findings for a home-based intervention. PLoS One. 2014:e109679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109679 .

Yamout BI, Alroughani R. Multiple Sclerosis. Semin Neurol. 2018;38:212–25. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1649502 .

Nissen N, Lemche J, Reestorff CM, Schmidt M, Skjerbæk AG, Skovgaard L, et al. The lived experience of uncertainty in everyday life with MS. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44:5957–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1955302 .

Strupp J, Hartwig A, Golla H, Galushko M, Pfaff H, Voltz R. Feeling severely affected by multiple sclerosis: what does this mean? Palliat Med. 2012;26:1001–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216311425420 .

Strupp J, Voltz R, Golla H. Opening locked doors: Integrating a palliative care approach into the management of patients with severe multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J. 2016;22:13–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kraft AK, Berger K. Kernaspekte einer bedarfsgerechten Versorgung von Patienten mit Multipler Sklerose : Inanspruchnahme ambulanter Leistungen und „shared decision making“ [Core aspects of a needs-conform care of patients with multiple sclerosis : Utilization of outpatient services and shared decision making]. Nervenarzt. 2020;91:503–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-020-00906-z .

Doshi A, Chataway J. Multiple sclerosis, a treatable disease. Clin Med (Lond). 2017;17:530–6. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.17-6-530 .

Kobelt G, Thompson A, Berg J, Gannedahl M, Eriksson J. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Mult Scler. 2017;23:1123–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517694432 .

Conradsson D, Ytterberg C, Engelkes C, Johansson S, Gottberg K. Activity limitations and participation restrictions in people with multiple sclerosis: a detailed 10-year perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43:406–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1626919 .

Sorensen PS, Giovannoni G, Montalban X, Thalheim C, Zaratin P, Comi G. The Multiple Sclerosis Care Unit. Mult Scler J. 2019;5:627–36.

Article Google Scholar

Tan H, Yu J, Tabby D, Devries A, Singer J. Clinical and economic impact of a specialty care management program among patients with multiple sclerosis: a cohort study. Mult Scler. 2010;16:956–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458510373487 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Oeseburg B, Wynia K, Middel B, Reijneveld SA. Effects of case management for frail older people or those with chronic illness: a systematic review. Nurs Res. 2009;58:201–10.

Aiken LS, Butner J, Lockhart CA, Volk-Craft BE, Hamilton G, Williams FG. Outcome evaluation of a randomized trial of the PhoenixCare intervention: program of case management and coordinated care for the seriously chronically ill. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:111–26. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2006.9.111 .

Kuhn U, Düsterdiek A, Galushko M, Dose C, Montag T, Ostgathe C, Voltz R. Identifying patients suitable for palliative care—a descriptive analysis of enquiries using a Case Management Process Model approach. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:611. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-5-611 .

Leary A, Quinn D, Bowen A. Impact of proactive case management by multiple sclerosis specialist nurses on use of unscheduled care and emergency presentation in multiple sclerosis: a case study. Int J MS Care. 2015;17:159–63. https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2014-011 .

Strupp J, Dose C, Kuhn U, Galushko M, Duesterdiek A, Ernstmann N, et al. Analysing the impact of a case management model on the specialised palliative care multi-professional team. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:673–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3893-3 .

Wynia K, Annema C, Nissen H, de Keyser J, Middel B. Design of a Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) on the effectiveness of a Dutch patient advocacy case management intervention among severely disabled Multiple Sclerosis patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:142. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-142 .

Ewers M, Schaeffer D, editors. Case Management in Theorie und Praxis. Bern: Huber; 2005.

Google Scholar

Neuffer M. Case Management: Soziale Arbeit mit Einzelnen und Familien. 5th ed. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Juventa; 2013.

Case Management Society of America. The standards of practice for case management. 2022.

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Care und Case Management e.V., editor. Case Management Leitlinien: Rahmenempfehlung, Standards und ethische Grundlagen. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: Medhochzwei; 2020.

Monzer M. Case Management Grundlagen. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: Medhochzwei; 2018.

Wissert M. Grundfunktionen und fachliche Standards des Unterstützungsmanagements. Z Gerontol Geriat. 1998;31(5):331–7.

Wissert M. Tools und Werkzeuge beim Case Management: Die Hilfeplanung. Case Manag. 2007;1:35–7.

Schaeffer D, Berens E-M, Vogt D. Health literacy in the German population. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114:53–60. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2017.0053 .

Pfaff H, Schulte H. Der onkologische Patient der Zukunft. Onkologe. 2012;18:127–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00761-011-2201-y .

Pfaff H, Kowalski C, Ommen O. Modelle zur Analyse von Integration und Koordination im Versorgungssystem. In: Ameldung, Sydow, Windeler, editor. Vernetzung im Gesundheitswesen: Wettbewerb und Kooperation. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag; 2009. p. 75–90.

Golla H, Mammeas S, Galushko M, Pfaff H, Voltz R. Unmet needs of caregivers of severely affected multiple sclerosis patients: A qualitative study. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(6):1685–93.

Golla H, Galushko M, Pfaff H, Voltz R. Multiple sclerosis and palliative care - perceptions of severely affected multiple sclerosis patients and their health professionals: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684x-13-11 .

Golla H, Galushko M, Pfaff H, Voltz R. Unmet needs of severely affected multiple sclerosis patients: the health professionals’ view. Palliat Med. 2012;26:139–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216311401465 .

Methley AM, Chew-Graham CA, Cheraghi-Sohi S, Campbell SM. A qualitative study of patient and professional perspectives of healthcare services for multiple sclerosis: implications for service development and policy. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25:848–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12369 .

Kalb R, Costello K, Guiod L. Case management services to meet the complex needs of patients with multiple sclerosis in the community—the successes and challenges of a unique program from the national multiple sclerosis society. US Neurology. 2019;15:27–31.

Krüger K, Fricke LM, Dilger E-M, Thiele A, Schaubert K, Hoekstra D, et al. How is and how should healthcare for people with multiple sclerosis in Germany be designed?-The rationale and protocol for the mixed-methods study Multiple Sclerosis-Patient-Oriented Care in Lower Saxony (MS-PoV). PLoS One. 2021;16:e0259855. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259855 .

Ivancevic S, Weegen L, Korff L, Jahn R, Walendzik A, Mostardt S, et al. Effektivität und Kosteneffektivät von Versorgungsmanagement-Programmen bei Multipler Sklerose in Deutschland – Eine Übersichtsarbeit. Akt Neurol. 2015;42:503–8. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1564111 .

Müller A, Dillen K, Dojan T, Ungeheuer S, Goereci Y, Dunkl V, et al. Development of a long-term cross-sectoral case and care management manual for patients with severe multiple sclerosis and their caregivers. Prof Case Manag. 2023;28:183–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCM.0000000000000608 .

Golla H, Dillen K, Hellmich M, Dojan T, Ungeheuer S, Schmalz P, et al. Communication, Coordination, and Security for People with Multiple Sclerosis (COCOS-MS): a randomised phase II clinical trial protocol. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e049300. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049300 .

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 .

Kuckartz U. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. 4th ed. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa; 2018.

Akyirem S, Ekpor E, Aidoo-Frimpong GA, Salifu Y, Nelson LE. Online interviews for qualitative health research in Africa: a scoping review. Int Health. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihad010 .

Peasgood T, Bourke M, Devlin N, Rowen D, Yang Y, Dalziel K. Randomised comparison of online interviews versus face-to-face interviews to value health states. Soc Sci Med. 2023;323:115818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115818 .

Giordano A, Cimino V, Campanella A, Morone G, Fusco A, Farinotti M, et al. Low quality of life and psychological wellbeing contrast with moderate perceived burden in carers of people with severe multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2016;366:139–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2016.05.016 .

Joo JY, Liu MF. Experiences of case management with chronic illnesses: a qualitative systematic review. Int Nurs Rev. 2018;65(1):102–1113.

Freeman J, Gorst T, Gunn H, Robens S. “A non-person to the rest of the world”: experiences of social isolation amongst severely impaired people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42:2295–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1557267 .

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Multiple sclerosis: Management of multiple sclerosis in primary and secondary care. 2014.

Erdmann A, Spoden C, Hirschberg I, Neitzke G. The wish to die and hastening death in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A scoping review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021;11:271–87. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002640 .

Erlangsen A, Stenager E, Conwell Y, Andersen PK, Hawton K, Benros ME, et al. Association between neurological disorders and death by suicide in Denmark. JAMA. 2020;323:444–54. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.21834 .

Kalb R, Feinstein A, Rohrig A, Sankary L, Willis A. Depression and suicidality in multiple sclerosis: red flags, management strategies, and ethical considerations. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2019;19:77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-019-0992-1 .

Feinstein A, Pavisian B. Multiple sclerosis and suicide. Mult Scler. 2017;23:923–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517702553 .

Marrie RA, Salter A, Tyry T, Cutter GR, Cofield S, Fox RJ. High hypothetical interest in physician-assisted death in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2017;88:1528–34. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003831 .

Gauthier S, Mausbach J, Reisch T, Bartsch C. Suicide tourism: a pilot study on the Swiss phenomenon. J Med Ethics. 2015;41:611–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2014-102091 .

Fischer S, Huber CA, Imhof L, MahrerImhof R, Furter M, Ziegler SJ, Bosshard G. Suicide assisted by two Swiss right-to-die organisations. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:810–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2007.023887 .

Strupp J, Ehmann C, Galushko M, Bücken R, Perrar KM, Hamacher S, et al. Risk factors for suicidal ideation in patients feeling severely affected by multiple sclerosis. J Palliat Med. 2016;19:523–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0418 .

Spence RA, Blanke CD, Keating TJ, Taylor LP. Responding to patient requests for hastened death: physician aid in dying and the clinical oncologist. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:693–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2016.019299 .

Monforte-Royo C, Villavicencio-Chávez C, Tomás-Sábado J, Balaguer A. The wish to hasten death: a review of clinical studies. Psychooncology. 2011;20:795–804. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1839 .

Blanke C, LeBlanc M, Hershman D, Ellis L, Meyskens F. Characterizing 18 years of the death with dignity act in Oregon. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1403–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0243 .

Methley A, Campbell S, Cheraghi-Sohi S, Chew-Graham C. Meeting the mental health needs of people with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study of patients and professionals. Disabil Rehab. 2017;39(11):1097-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1180547 .

Hudon C, Bisson M, Chouinard M-C, Delahunty-Pike A, Lambert M, Howse D, et al. Implementation analysis of a case management intervention for people with complex care needs in primary care: a multiple case study across Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23:377. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09379-7 .

Beckmann M, Dittmer K, Jaschke J, Karbach U, Köberlein-Neu J, Nocon M, et al. Electronic patient record and its effects on social aspects of interprofessional collaboration and clinical workflows in hospitals (eCoCo): a mixed methods study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:377. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06377-5 .

Campanella P, Lovato E, Marone C, Fallacara L, Mancuso A, Ricciardi W, Specchia ML. The impact of electronic health records on healthcare quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26:60–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv122 .

García-Hernández M, González de León B, Barreto-Cruz S, Vázquez-Díaz JR. Multicomponent, high-intensity, and patient-centered care intervention for complex patients in transitional care: SPICA program. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1033689. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.1033689 .

Meisinger C, Stollenwerk B, Kirchberger I, Seidl H, Wende R, Kuch B, Holle R. Effects of a nurse-based case management compared to usual care among aged patients with myocardial infarction: results from the randomized controlled KORINNA study. BMC Geriatr. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-13-115 .

Joo JY, Huber DL. Case management effectiveness on health care utilization outcomes: a systematic review of reviews. West J Nurs Res. 2019;41:111–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945918762135 .

Stergiopoulos V, Gozdzik A, Misir V, Skosireva A, Connelly J, Sarang A, et al. Effectiveness of housing first with intensive case management in an ethnically diverse sample of homeless adults with mental illness: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130281. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130281 .

Löcherbach P, Wendt R, editors. Care und Case Management: Transprofessionelle Versorgungsstrukturen und Netzwerke. 1st ed. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer; 2020.

EAPC2023 Abstract Book. Palliat Med. 2023;37:1–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163231172891 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the patients, caregivers and health care specialists who volunteered their time to participate in an interview and the trial, Carola Janßen for transcribing the interviews, Fiona Brown for translating the illustrative quotes and Beatrix Münzberg, Kerstin Weiß and Monika Höveler for data collection in the quantitative study part.

COCOS-MS Trial Group

Anne Müller 1 , Fabian Hebben 1 , Kim Dillen 1 , Veronika Dunkl 1 , Yasemin Goereci 2 , Raymond Voltz 1,3,4 , Peter Löcherbach 5 , Clemens Warnke 2 , Heidrun Golla 1 , Dirk Müller 6 , Dorthe Hobus 1 , Eckhard Bonmann 7 , Franziska Schwartzkopff 8 , Gereon Nelles 9 , Gundula Palmbach 8 , Herbert Temmes 10 , Isabel Franke 1 , Judith Haas 10 , Julia Strupp 1 , Kathrin Gerbershagen 7 , Laura Becker-Peters 8 , Lothar Burghaus 11 , Martin Hellmich 12 , Martin Paus 8 , Solveig Ungeheuer 1 , Sophia Kochs 1 , Stephanie Stock 6 , Thomas Joist 13 , Volker Limmroth 14

1 Department of Palliative Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

2 Department of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

3 Center for Integrated Oncology Aachen Bonn Cologne Düsseldorf (CIO ABCD), University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

4 Center for Health Services Research (ZVFK), University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

5 German Society of Care and Case Management e.V. (DGCC), Münster, Germany

6 Institute for Health Economics and Clinical Epidemiology (IGKE), Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

7 Department of Neurology, Klinikum Köln, Cologne, Germany

8 Clinical Trials Centre Cologne (CTCC), Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

9 NeuroMed Campus, MedCampus Hohenlind, Cologne, Germany

10 German Multiple Sclerosis Society Federal Association (DMSG), Hannover, Germany

11 Department of Neurology, Heilig Geist-Krankenhaus Köln, Cologne, Germany

12 Institute of Medical Statistics and Computational Biology (IMSB), Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

13 Academic Teaching Practice, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

14 Department of Neurology, Klinikum Köln-Merheim, Cologne, Germany

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the Innovation Funds of the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA), grant number: 01VSF19029.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Palliative Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

Anne Müller, Fabian Hebben, Kim Dillen, Veronika Dunkl, Raymond Voltz & Heidrun Golla

Department of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

Yasemin Goereci & Clemens Warnke

Center for Integrated Oncology Aachen Bonn Cologne Düsseldorf (CIO ABCD), University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

Raymond Voltz