What the Covid-19 Pandemic Revealed About Remote School

The unplanned experiment provided clear lessons on the value—and limitations—of online learning. Are educators listening?

Katherine Reynolds Lewis, Undark Magazine

:focal(512x344:513x345)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/03/d6/03d60640-f6dd-4840-984d-22d3f18f1d73/gettyimages-1282746597.jpg)

The transition to online learning in the United States during the Covid-19 pandemic was, by many accounts, a failure. While there were some bright spots across the country, the transition was messy and uneven — countless teachers had neither the materials nor training they needed to effectively connect with students remotely, while many of those students were bored , isolated, and lacked the resources they needed to learn. The results were abysmal: low test scores, fewer children learning at grade level, increased inequity, and teacher burnout. With the public health crisis on top of deaths and job losses in many families, students experienced increases in depression, anxiety, and suicide risk.

Yet society very well may face new widespread calamities in the near future, from another pandemic to extreme weather, that will require a similarly quick shift to remote school. Success will hinge on big changes, from infrastructure to teacher training, several experts told Undark. “We absolutely need to invest in ways for schools to run continuously, to pick up where they left off. But man, it’s a tall order,” said Heather L. Schwartz, a senior policy researcher at RAND. “It’s not good enough for teachers to simply refer students to disconnected, stand-alone videos on, say, YouTube. Students need lessons that connect directly to what they were learning before school closed.”

More than three years after U.S. schools shifted to remote instruction on an emergency basis, the education sector is still largely unprepared for another long-term interruption of in-person school. The stakes are highest for those who need it most: low-income children and students of color, who are also most likely to be harmed in a future pandemic or live in communities most affected by climate change. But, given the abundance of research on what didn’t work during the pandemic, school leaders may have the opportunity to do things differently next time. Being ready would require strategic planning, rethinking the role of the teacher, and using new technology wisely, experts told Undark. And many problems with remote learning actually trace back not to technology, but to basic instructional quality. Effective remote learning won’t happen if schools aren’t already employing best practices in the physical classroom, such as creating a culture of learning from mistakes, empowering teachers to meet individual student needs, establishing high expectations, and setting clear goals supported by frequent feedback. While it’s ambitious to envision that every school district will create seamless virtual learning platforms — and, for that matter, overcome challenges in education more broadly — the lessons of the pandemic are there to be followed or ignored.

“We haven’t done anywhere near the amount of planning or the development of the instructional infrastructure needed to allow for a smooth transition next time schools need to close for prolonged periods of time,” Schwartz said. “Until we can reach that goal, I don’t have high confidence that the next prolonged school closure will be substantially more successful.”

Before the pandemic, only 3 percent of U.S. school districts offered virtual school, mostly for students with unique circumstances, such as a disability or those intensely pursuing a sport or the performing arts, according to a RAND survey Schwartz co-authored. For the most part, the educational technology companies and developers creating software for these schools promised to give students a personalized experience. But the research on these programs, which focused on virtual charter schools that only existed online, showed poor outcomes . Their students were a year behind in math and nearly a half-year behind in reading, and courses offered less direct time with a teacher each week than regular schools have in a day.

The pandemic sparked growth in stand-alone virtual academies, in addition to the emergency remote learning that districts had to adopt in March 2020. Educators’ interest in online instructional materials exploded, too, according to Schwartz, “and it really put the foot on the gas to ramp them up, expand them, and in theory, improve them.” By June 2021, the number of school districts with a stand-alone virtual school rose to 26 percent. Of the remaining districts, another 23 percent were interested in offering an online school, the report found.

But the sheer magnitude of options for online learning didn’t necessarily mean it worked well, Schwartz said: “It’s the quality part that has to come up in order for this to be a really good, viable alternative to in person instruction.” And individualized, self-directed online learning proved to be a pipe dream — especially for younger children who needed support from a parent or other family member even to get online, much less stay focused.

“The notion that students would have personalized playlists and could curate their own education was proven to be problematic on a couple levels, especially for younger and less affluent students,” said Thomas Toch, director of FutureEd, an education think tank at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. “The social and emotional toll that isolation and those traumas took on students suggest that the social dimension of schooling is hugely important and was greatly undervalued, especially by proponents for an increased role of technology.”

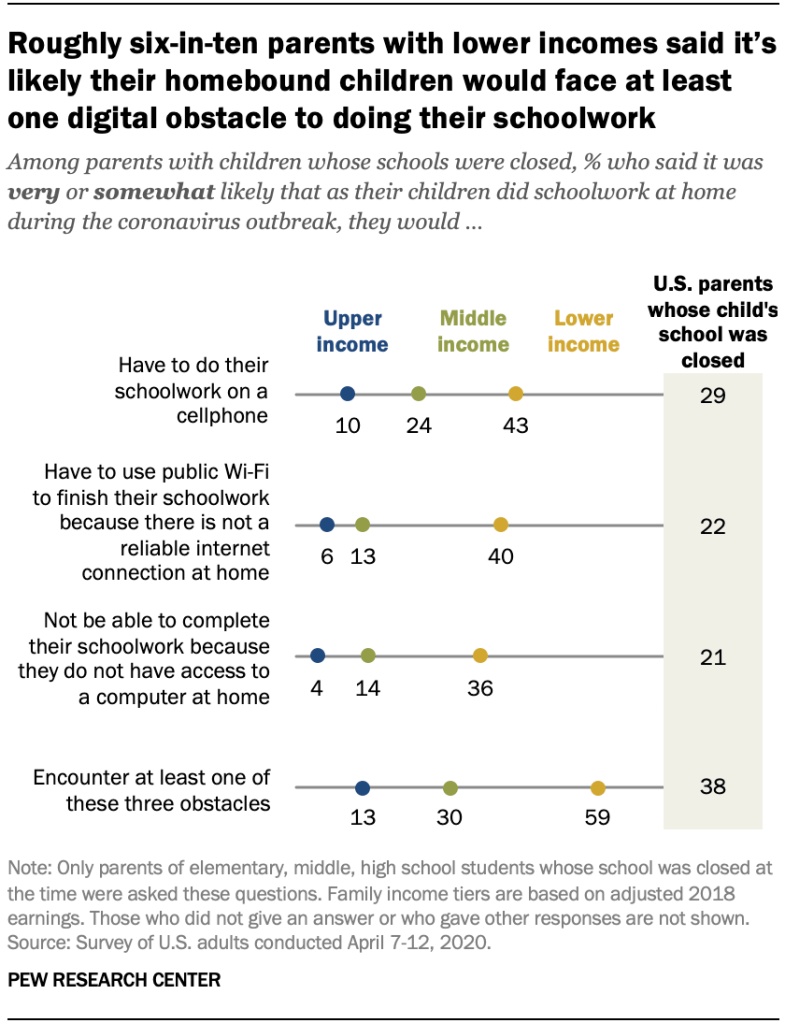

Students also often didn’t have the materials they needed for online school, some lacking computers or internet access at home. Teachers didn’t have the right training for online instruction , which has a unique pedagogy and best practices. As a result, many virtual classrooms attempted to replicate the same lessons over video that would’ve been delivered at school. The results were overwhelmingly bad, research shows. For example, a 2022 study found six consistent themes about how the pandemic affected learning, including a lack of interaction between students and with teachers, and disproportionate harm to low-income students. Numb from isolation and too many hours in front of a screen, students failed to engage in coursework and suffered emotionally .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/05/e1/05e16ea9-bd7f-4fbf-846e-177f05272f72/gettyimages-1229757662.jpg)

After some districts resumed in-person or hybrid instruction in the 2020 fall semester, it became clear that the longer students were remote, the worse their learning delays . For example, national standardized test scores for the 2020-2021 school year showed that passing rates for math declined about 14 percentage points on average, more than three times the drop seen in districts that returned to in-person instruction the earliest, according to a 2021 National Bureau of Economic Research study . Even after most U.S. districts resumed in-person instruction, students who had been online the longest continued to lag behind their peers. The pandemic hit cities hardest and the effects disproportionately harmed low-income children and students of color in urban areas.

“What we did during the pandemic is not the optimal use of online learning in education for the future,” said Ashley Jochim, a researcher at the Center on Reinventing Public Education at Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College. “Online learning is not a full stop substitute for what kids need to thrive and be supported at school.”

Children also largely prefer in-person school. A 2022 Pew Research Center survey suggested that 65 percent of students would rather be in a classroom, 9 percent would opt for online only, and the rest are unsure or prefer a hybrid model. “For most families and kids, full-time online school is actually not the educational solution they want,” Jochim said.

Virtual school felt meaningless to Abner Magdaleno, a 12th grader in Los Angeles. “I couldn’t really connect with it, because I’m more of, like, a social person. And that was stripped away from me when we went online,” recalled Magdaleno. Mackenzie Sheehy, 19, of Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, found there were too many distractions at home to learn. Her grades suffered, and she missed the one-on-one time with teachers. (Sheehy graduated from high school in 2022.)

Many teachers feel the same way. “Nothing replaces physical proximity, whatever the age,” said Ana Silva, a New York City English teacher. She enjoyed experimenting with interactive technology during online school, but is grateful to be back in person. “I like the casual way kids can come to my desk and see me. I like the dynamism — seeing kids in the cafeteria. Those interactions are really positive, and they were entirely missing during the online learning.”

During the 2022-2023 school year, many districts initially planned to continue online courses for snow days and other building closures. But they found that the teacher instruction, student experience, and demands on families were simply too different for in-person versus remote school, said Liz Kolb, an associate professor in the School of Education at the University of Michigan. “Schools are moving away from that because it’s too difficult to quickly transition and blend back and forth among the two without having strong structures in place,” Kolb said. “Most schools don’t have those strong structures.”

In addition, both families and educators grew sick of their screens. “They’re trying to avoid technology a little bit. There’s this fatigue coming out of remote learning and the pandemic,” said Mingyu Feng, a research director at WestEd, a nonprofit research agency. “If the students are on Zoom every day for like, six hours, that seems to be not quite right.”

Despite the bumpy pandemic rollout, online school can serve an important role in the U.S. education system. For one, online learning is a better alternative for some students. Garvey Mortley, 15, of Bethesda, Maryland, and her two sisters all switched to their district’s virtual academy during the pandemic to protect their own health and their grandmother’s. This year, Mortley’s sisters went back to in-person school, but she chose to stay online. “I love the flexibility about it,” she said, noting that some of her classmates prefer it because they have a disability or have demanding schedules. “I love how I can just roll out of bed in the morning, and I can sit down and do school.” Some educators also prefer teaching online, according to reports of virtual schools that were inundated with applications from teachers because they wanted to keep working from home . Silva, the New York high school English teacher, enjoys online tutoring and academic coaching, because it facilitates one-on-one interaction.

And in rural districts and those with low enrollment, some access to online learning ensures students can take courses that could otherwise be inaccessible. “Because of the economies of scale in small rural districts, they needed to tap into online and shared service delivery arrangements in order to provide a full complement of coursework at the high school level,” said Jochim. Innovation in these districts, she added, will accelerate: “We’ll continue to see growth, scalability, and improvement in quality.”

There were also some schools that were largely successful at switching to online at the start of the pandemic, such as Vista Unified School District in California, which pooled and shared innovative ideas for adapting in March 2020; the school quickly put together an online portal so that principals and teachers could share ideas and the district could allot the necessary resources. Digging into examples like this could point the way to the future of online learning, said Chelsea Waite, a senior researcher at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, who was part of a collaborative project studying 70 schools and districts that pivoted successfully to online learning. The project found three factors that made the transition work: a focus on resilience, collaboration, and autonomy for both students and educators; a healthy culture that prioritized relationships; and strong yet flexible systems that were accustomed to adaptation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/60/64/606453dd-d157-45da-a865-5161f95b6f08/gettyimages-1228656332.jpg)

“We investigated schools that did seem to be more prepared for the Covid disruption, not just with having devices in students’ hands or having an online curriculum already, but with a learning culture in the school that really prioritized agency and problem solving as skills for students and adults,” Waite said. “In these schools, kids are learning from a very young age to be a little bit more self-directed, to set goals, and pursue them and pivot when they need to.”

Similarly, many of the takeaways from the pandemic trace back to the basics of effective education, not technological innovation. A landmark report by the National Academies of Sciences called “How People Learn,” most recently updated in 2018, synthesized the body of educational research and identified four key features in the most successful learning environments. First, these schools are designed for, and adapt to, the specific students, building on what they bring to the classroom, such as skills and beliefs. Second, successful schools give their students clear goals, showing them what they need to learn and how they can get there. Third, they provide in-the-moment feedback that emphasizes understanding, not memorization. And finally, the most successful schools are community-centered, with a culture of collaboration and acceptance of mistakes.

“We as humans are social learners, yet some of the tech talk is driven by people who are strong individual learners,” said Jeremy Roschelle, executive director of Learning Sciences Research at Digital Promise, a global education nonprofit. “They’re not necessarily thinking about how most people learn, which is very social.”

Another powerful insight from pandemic-era remote schooling involves the evolving role of teachers, said Kim Kelly, a middle school math teacher at Northbridge Middle School in Massachusetts and a K-8 curriculum coach. Historically, a teacher’s role is the keeper of knowledge who delivers instruction. But in recent years, there has been a shift in approach, where teachers think of themselves as coaches who can intervene based on a student’s individual learning progress. Technology that assists with a coach-like role can be effective — but requires educators to be trained and comfortable interpreting data on student needs.

For example, with a digital learning platform called ASSISTments, teachers can assign math problems, students complete them — potentially receiving in-the-moment feedback on steps they’re getting wrong — and then the teachers can use data from individual students and the entire class to plan instruction and see where additional support is needed.

“A big advantage of these computer-driven products is they really try to diagnose where students are, and try to address their needs. It’s very personalized, individualized,” said WestEd’s Feng, who has evaluated ASSISTments and other educational technologies. She noted that some teachers feel frustrated “when you expect them to read the data and try to figure out what the students’ needs are.”

Teacher’s colleges don’t typically prepare educators to interpret data and change their practices, said Kelly, whose dissertation focused on self-regulated online learning. But professional development has helped her learn to harness technology to improve teaching and learning. “Schools are in data overload; we are oozing data from every direction, yet none of it is very actionable,” she said. Some technology, she added, provided student data that she could use regularly, which changed how she taught and assigned homework.

When students get feedback from the computer program during a homework session, the whole class doesn’t have to review the homework together, which can save time. Educators can move forward on instruction — or if they see areas of confusion, focus more on those topics. The ability of the programs to detect how well students are learning “is unreal,” said Kelly, “but it really does require teachers to be monitoring that data and interpreting.” She learned to accept that some students could drive their own learning and act on the feedback from homework, while others simply needed more teacher intervention. She now does more assessment at the beginning of a course to better support all students.

At the district or even national level, letting teachers play to their strengths can also help improve how their students learn, Toch, of FutureEd, said. For example, if a teacher is better at delivering instruction, they could give a lesson to a larger group of students online, while another teacher who is more comfortable in the coach role could work in smaller groups or one-on-one.

“One thing we saw during the pandemic are smart strategies for using technology to get outstanding teachers in front of more students,” Toch said, describing one effort that recruited exceptional teachers nationally and built a strong curriculum to be delivered online. “The local educators were providing support for their students in their classrooms.”

Remote schooling requires new technology, and already, educators are swamped with competing platforms and software choices — most of which have insufficient evidence of efficacy . Traditional independent research on specific technologies is sparse, Roschelle said. Post-pandemic, the field is so diverse and there are so many technologies in use, it’s almost impossible to find a control group to design a randomized control trial, he added. However, there is qualitative research and evidence that give hints about the quality of technology and online learning, such as case studies and school recommendations.

Educational leaders should ask three key questions about technology before investing, recommended Ryan Baker, a professor of education at the University of Pennsylvania: Is there evidence it works to improve learning outcomes? Does the vendor provide support and training, or are teachers on their own? And does it work with the same types of students as are in their school or district? In other words, educators must look at a technology’s track record in the context of their own school’s demographics, geography, culture, and challenges. These decisions are complicated by the small universe of researchers and evaluators, who have many overlapping relationships. (Over his career, for example, Baker has worked with or consulted for many of the education technology firms that create the software he studies.)

It may help to broaden the definition of evidence. The Center on Reinventing Public Education launched the Canopy project to collect examples of effective educational innovation around the U.S.

“What we wanted to do is build much better and more open and collective knowledge about where schools are challenging old assumptions and redesigning what school is and should be,” she added, noting that these educational leaders are reconceptualizing the skills they want students to attain. “They’re often trying to measure or communicate concepts that we don’t have great measurement tools for yet. So they end up relying on a lot of testimonials and evidence of student work.”

The moment is ripe for innovation in online and in-person education, said Julia Fallon, executive director of the State Educational Technology Directors Association, since the pandemic accelerated the rollout of devices and needed infrastructure. There’s an opportunity and need for technology that empowers teachers to improve learning outcomes and work more efficiently, said Roschelle. Online and hybrid learning are clearly here to stay — and likely will be called upon again during future temporary school closures.

Still, poorly-executed remote learning risks tainting the whole model; parents and students may be unlikely to give it a second chance. The pandemic showed the hard and fast limits on the potential for fully remote learning to be adopted broadly, for one, because in many communities, schools serve more than an educational function — they support children’s mental health, social needs, and nutrition and other physical health needs. The pandemic also highlighted the real challenge in training the entire U.S. teaching corps to be proficient in technology and data analysis. And the lack of a nimble shift to remote learning in an emergency will disproportionately harm low-income children and students of color. So the stakes are high for getting it right, experts told Undark, and summoning the political will.

“There are these benefits in online education, but there are also these real weaknesses we know from prior research and experience,” Jochim said. “So how do we build a system that has online learning as a complement to this other set of supports and experiences that kids benefit from?”

Katherine Reynolds Lewis is an award-winning journalist covering children, race, gender, disability, mental health, social justice, and science.

This article was originally published on Undark . Read the original article .

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Six Online Activities to Help Students Cope With COVID-19

At the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, UNESCO estimates that 91.3% of the world’s students were learning remotely, with 194 governments ordering country-wide closures of their schools and more than 1.3 billion students learning in online classrooms.

Now that the building blocks of remote education have been put into place and classroom learning is underway, more and more teachers are turning their attention to the mental health of their students. Youth anxiety about the coronavirus is rising , and our young people are feeling isolated, disconnected, and confused. While social-emotional education has typically taken place in the bricks and mortar of schools, we must now adapt these curriculums for an online setting.

I have created six well-being activities for teachers to deliver online using the research-based SEARCH framework , which stands for Strengths, Emotional management, Attention and awareness, Relationships, Coping, and Habits and goals. Research suggests that students who cultivate these skills have stronger coping capacity , are more adaptable and receptive to change , and are more satisfied with their lives .

The virtual activities can be used for specific well-being lessons or advisory classes , or can be woven into other curricula you are teaching, such as English, Art, Humanities, and Physical Education. You might consider using the activities in three ways:

- Positive primer: to energize your students at the start of class to kickstart learning, prompt them to think about their well-being in that moment, get them socially connected online, and get their brain focused for learning.

- Positive pause: to re-energize students at a time when you see class dynamics shifting, energy levels dropping, or students being distracted away from the screen.

- Positive post-script: to reward students and finish off the class in a positive way before they log off.

Rather than viewing these activities as another thing you have to fit in, use them as a learning tool that helps your students stay focused, connected, and energized.

1. Strengths

Activity: Staying Strong During COVID-19 Learning goal: To help students learn about their own strengths Time: 50 minutes Age: 10+

Prior to the lesson, have students complete the VIA strengths questionnaire to identify their strengths.

Step 1: In the virtual class, explain the VIA strengths framework to students. The VIA framework is a research-based model that outlines 24 universal character strengths (such as kindness, courage, humor, love of learning, and perseverance) that are reflected in a student’s pattern of thoughts, feelings, and actions. You can learn more about the framework and find a description of each character strength from the VIA Institute on Character .

Step 2: Place students in groups of four into chat rooms on your online learning platform and ask them to discuss these reflection questions:

- What are your top five strengths?

- How can you use your strengths to stay engaged during remote learning?

- How can you use your strengths during home lockdown or family quarantine?

- How do you use your strengths to help your friends during COVID-19?

Step 3: As a whole class, discuss the range of different strengths that can be used to help during COVID times.

Research shows that using a strength-based approach at school can improve student engagement and grades , as well as create more positive social dynamics among students. Strengths also help people to overcome adversity .

2. Emotional management

Activity: Managing Emotions During the Coronavirus Pandemic Learning goal: To normalize negative emotions and to generate ways to promote more positive emotions Time: 50 minutes Age: 8+

Step 1: Show students an “emotion wheel” and lead a discussion with them about the emotions they might be feeling as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. You can use this wheel for elementary school and this wheel for high school.

Step 2: Create an anonymous online poll (with a service like SurveyMonkey ) listing the following 10 emotions: stressed, curious, frustrated, happy, angry, playful, sad, calm, helpless, hopeful.

Step 3: In the survey, ask students to enter the five emotions they are feeling most frequently.

Step 4: Tally the results and show them on your screen for each of the 10 emotions. Discuss the survey results. What emotions are students most often feeling? Talk about the range of emotions experienced. For example, some people will feel sad when others might feel curious; students can feel frustrated but hopeful at the same time.

Step 5: Select the top two positive emotions and the top two negative emotions from the survey. Put students into groups of four in virtual breakout rooms to brainstorm three things they can do to cope with their negative emotions, and three action steps they can take to have more positive emotions.

Supporting Learning and Well-Being During the Coronavirus Crisis

Activities, articles, videos, and other resources to address student and adult anxiety and cultivate connection

Research shows that emotional management activities help to boost self-esteem and reduce distress in students. Additionally, students with higher emotional intelligence also have higher academic performance .

3. Attention and awareness

Activity: Finding Calm During Coronavirus Times Learning goal: To use a mindful breathing practice to calm our heart and clear our mind Time: 10 minutes Age: All

Step 1: Have students rate their levels of stress on a scale of 1-10, with 1 being very calm and 10 being highly stressed.

Step 2: Do three minutes of square breathing, which goes like this:

- Image a square in front of you at chest height.

- Point your index finger away from you and use it to trace the four sides of the imaginary square.

- As you trace the first side of the square, breathe in for four seconds.

- As you trace the next side of the square, breathe out for four seconds.

- Continue this process to complete the next two sides of the square.

- Repeat the drawing of the square four times.

Step 3: Have students rate their levels of stress on a scale of 1-10, with 1 being very calm and 10 being highly stressed. Discuss if this short breathing activity made a difference to their stress.

Step 4: Debrief on how sometimes we can’t control the big events in life, but we can use small strategies like square breathing to calm us down.

Students who have learned mindfulness skills at school report that it helps to reduce their stress and anxiety .

4. Relationships

Activity: Color conversations Purpose: To get to know each other; to deepen class relationships during remote learning Time: 20 minutes Age: 10+

Step 1: Randomly assign students to one of the following four colors: red, orange, yellow, and purple.

Step 2: Put students into a chat room based on their color group and provide the following instructions to each group:

- Red group: Share a happy memory.

- Orange group: Share something new that you have learned recently.

- Yellow group: Share something unique about you.

- Purple group: Share what your favorite food is and why.

Step 3: Come back to the main screen and ask three students to share something new they learned about a fellow student as a result of this fun activity.

Three Good Things for Students

Help students tune in to the positive events in their lives

This is an exercise you can use repeatedly, as long as you ensure that students get mixed up into different groups each time. You can also create new prompts to go with the colors (for example, dream holiday destination, favorite ice cream flavor, best compliment you ever received).

By building up student connections, you are supporting their well-being, as research suggests that a student’s sense of belonging impacts both their grades and their self-esteem .

Activity: Real-Time Resilience During Coronavirus Times Learning goal: To identify opportunities for resilience and promote positive action Time: 30 minutes Age: 10+

Step 1: Have students brainstorm a list of all the changes that have occurred as a result of the coronavirus. As the students are brainstorming, type up their list of responses on your screen.

Step 2: Go through each thing that has changed, and have the students decide if it is something that is within their control (like their study habits at home) or something they cannot control (like not attending school on campus).

Step 3: Choose two things that the students have identified as within their control, and ask students to brainstorm a list of ways to cope with those changes.

You can repeat this exercise multiple times to go through the other points on the list that are within the students’ control.

Developing coping skills during childhood and adolescence has been show to boost students’ hope and stress management skills —both of which are needed at this time.

6. Habits and goals

Activity: Hope Hearts for the Coronavirus Pandemic Learning goal: To help students see the role that hope plays in setting goals during hard times Time: 50 minutes Age: 10+

Step 1: Find a heart image for students to use (with a program like Canva ).

Step 2: Set up an online whiteboard to post the hearts on (with a program like Miro ).

Step 3: Ask students to reflect on what hope means to them.

Step 4: Ask students to write statements on their hearts about what they hope for the world during coronavirus times, and then stick these on the whiteboard. Discuss common themes with the class. Finally, discuss one small action each student can take to create hope for others during this distressing time.

Step 5: Ask students to write statements on their hearts about what they hope for themselves, and then stick these on the whiteboard. Discuss common themes with the class. Finally, discuss one small action each student can take to work toward the goal they’re hoping for.

Helping students to set goals and have hope at this time can support their well-being. Research suggests that goals help to combat student boredom and anxiety , while having hope builds self-worth and life satisfaction .

The six activities above have been designed to help you stay connected with your students during this time of uncertainty—connected beyond the academic content that you are teaching. The intense change we are all facing has triggered heightened levels of stress and anxiety for students and teachers alike. Weaving well-being into online classrooms gives us the opportunity to provide a place of calm and show students they can use adversity to build up their emotional toolkit. In this way, you are giving them a skill set that has the potential to endure beyond the pandemic and lessons that may stay with them for many years to come.

About the Author

Lea Waters , A.M., Ph.D. , is an academic researcher, psychologist, author, and speaker who specializes in positive education, parenting, and organizations. Professor Waters is the author of the Visible Wellbeing elearning program that is being used by schools across the globe to foster social and emotional elearning. Professor Waters is the founding director and inaugural Gerry Higgins Chair in Positive Psychology at the Centre for Positive Psychology , University of Melbourne, where she has held an academic position for 24 years. Her acclaimed book The Strength Switch: How The New Science of Strength-Based Parenting Can Help Your Child and Your Teen to Flourish was listed as a top read by the Greater Good Science Center in 2017.

You May Also Enjoy

How to Reduce the Stress of Homeschooling on Everyone

How Teachers Can Navigate Difficult Emotions During School Closures

How to Teach Online So All Students Feel Like They Belong

Can the Lockdown Push Schools in a Positive Direction?

How to Help Students with Learning Disabilities Focus on Their Strengths

How to Support Teachers’ Emotional Needs Right Now

The pandemic has had devastating impacts on learning. What will it take to help students catch up?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, megan kuhfeld , megan kuhfeld senior research scientist - nwea @megankuhfeld jim soland , jim soland assistant professor, school of education and human development - university of virginia, affiliated research fellow - nwea @jsoland karyn lewis , and karyn lewis director, center for school and student progress - nwea @karynlew emily morton emily morton research scientist - nwea @emily_r_morton.

March 3, 2022

As we reach the two-year mark of the initial wave of pandemic-induced school shutdowns, academic normalcy remains out of reach for many students, educators, and parents. In addition to surging COVID-19 cases at the end of 2021, schools have faced severe staff shortages , high rates of absenteeism and quarantines , and rolling school closures . Furthermore, students and educators continue to struggle with mental health challenges , higher rates of violence and misbehavior , and concerns about lost instructional time .

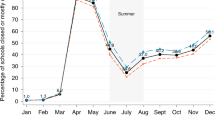

As we outline in our new research study released in January, the cumulative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic achievement has been large. We tracked changes in math and reading test scores across the first two years of the pandemic using data from 5.4 million U.S. students in grades 3-8. We focused on test scores from immediately before the pandemic (fall 2019), following the initial onset (fall 2020), and more than one year into pandemic disruptions (fall 2021).

Average fall 2021 math test scores in grades 3-8 were 0.20-0.27 standard deviations (SDs) lower relative to same-grade peers in fall 2019, while reading test scores were 0.09-0.18 SDs lower. This is a sizable drop. For context, the math drops are significantly larger than estimated impacts from other large-scale school disruptions, such as after Hurricane Katrina—math scores dropped 0.17 SDs in one year for New Orleans evacuees .

Even more concerning, test-score gaps between students in low-poverty and high-poverty elementary schools grew by approximately 20% in math (corresponding to 0.20 SDs) and 15% in reading (0.13 SDs), primarily during the 2020-21 school year. Further, achievement tended to drop more between fall 2020 and 2021 than between fall 2019 and 2020 (both overall and differentially by school poverty), indicating that disruptions to learning have continued to negatively impact students well past the initial hits following the spring 2020 school closures.

These numbers are alarming and potentially demoralizing, especially given the heroic efforts of students to learn and educators to teach in incredibly trying times. From our perspective, these test-score drops in no way indicate that these students represent a “ lost generation ” or that we should give up hope. Most of us have never lived through a pandemic, and there is so much we don’t know about students’ capacity for resiliency in these circumstances and what a timeline for recovery will look like. Nor are we suggesting that teachers are somehow at fault given the achievement drops that occurred between 2020 and 2021; rather, educators had difficult jobs before the pandemic, and now are contending with huge new challenges, many outside their control.

Clearly, however, there’s work to do. School districts and states are currently making important decisions about which interventions and strategies to implement to mitigate the learning declines during the last two years. Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) investments from the American Rescue Plan provided nearly $200 billion to public schools to spend on COVID-19-related needs. Of that sum, $22 billion is dedicated specifically to addressing learning loss using “evidence-based interventions” focused on the “ disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on underrepresented student subgroups. ” Reviews of district and state spending plans (see Future Ed , EduRecoveryHub , and RAND’s American School District Panel for more details) indicate that districts are spending their ESSER dollars designated for academic recovery on a wide variety of strategies, with summer learning, tutoring, after-school programs, and extended school-day and school-year initiatives rising to the top.

Comparing the negative impacts from learning disruptions to the positive impacts from interventions

To help contextualize the magnitude of the impacts of COVID-19, we situate test-score drops during the pandemic relative to the test-score gains associated with common interventions being employed by districts as part of pandemic recovery efforts. If we assume that such interventions will continue to be as successful in a COVID-19 school environment, can we expect that these strategies will be effective enough to help students catch up? To answer this question, we draw from recent reviews of research on high-dosage tutoring , summer learning programs , reductions in class size , and extending the school day (specifically for literacy instruction) . We report effect sizes for each intervention specific to a grade span and subject wherever possible (e.g., tutoring has been found to have larger effects in elementary math than in reading).

Figure 1 shows the standardized drops in math test scores between students testing in fall 2019 and fall 2021 (separately by elementary and middle school grades) relative to the average effect size of various educational interventions. The average effect size for math tutoring matches or exceeds the average COVID-19 score drop in math. Research on tutoring indicates that it often works best in younger grades, and when provided by a teacher rather than, say, a parent. Further, some of the tutoring programs that produce the biggest effects can be quite intensive (and likely expensive), including having full-time tutors supporting all students (not just those needing remediation) in one-on-one settings during the school day. Meanwhile, the average effect of reducing class size is negative but not significant, with high variability in the impact across different studies. Summer programs in math have been found to be effective (average effect size of .10 SDs), though these programs in isolation likely would not eliminate the COVID-19 test-score drops.

Figure 1: Math COVID-19 test-score drops compared to the effect sizes of various educational interventions

Source: COVID-19 score drops are pulled from Kuhfeld et al. (2022) Table 5; reduction-in-class-size results are from pg. 10 of Figles et al. (2018) Table 2; summer program results are pulled from Lynch et al (2021) Table 2; and tutoring estimates are pulled from Nictow et al (2020) Table 3B. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are shown with vertical lines on each bar.

Notes: Kuhfeld et al. and Nictow et al. reported effect sizes separately by grade span; Figles et al. and Lynch et al. report an overall effect size across elementary and middle grades. We were unable to find a rigorous study that reported effect sizes for extending the school day/year on math performance. Nictow et al. and Kraft & Falken (2021) also note large variations in tutoring effects depending on the type of tutor, with larger effects for teacher and paraprofessional tutoring programs than for nonprofessional and parent tutoring. Class-size reductions included in the Figles meta-analysis ranged from a minimum of one to minimum of eight students per class.

Figure 2 displays a similar comparison using effect sizes from reading interventions. The average effect of tutoring programs on reading achievement is larger than the effects found for the other interventions, though summer reading programs and class size reduction both produced average effect sizes in the ballpark of the COVID-19 reading score drops.

Figure 2: Reading COVID-19 test-score drops compared to the effect sizes of various educational interventions

Source: COVID-19 score drops are pulled from Kuhfeld et al. (2022) Table 5; extended-school-day results are from Figlio et al. (2018) Table 2; reduction-in-class-size results are from pg. 10 of Figles et al. (2018) ; summer program results are pulled from Kim & Quinn (2013) Table 3; and tutoring estimates are pulled from Nictow et al (2020) Table 3B. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are shown with vertical lines on each bar.

Notes: While Kuhfeld et al. and Nictow et al. reported effect sizes separately by grade span, Figlio et al. and Kim & Quinn report an overall effect size across elementary and middle grades. Class-size reductions included in the Figles meta-analysis ranged from a minimum of one to minimum of eight students per class.

There are some limitations of drawing on research conducted prior to the pandemic to understand our ability to address the COVID-19 test-score drops. First, these studies were conducted under conditions that are very different from what schools currently face, and it is an open question whether the effectiveness of these interventions during the pandemic will be as consistent as they were before the pandemic. Second, we have little evidence and guidance about the efficacy of these interventions at the unprecedented scale that they are now being considered. For example, many school districts are expanding summer learning programs, but school districts have struggled to find staff interested in teaching summer school to meet the increased demand. Finally, given the widening test-score gaps between low- and high-poverty schools, it’s uncertain whether these interventions can actually combat the range of new challenges educators are facing in order to narrow these gaps. That is, students could catch up overall, yet the pandemic might still have lasting, negative effects on educational equality in this country.

Given that the current initiatives are unlikely to be implemented consistently across (and sometimes within) districts, timely feedback on the effects of initiatives and any needed adjustments will be crucial to districts’ success. The Road to COVID Recovery project and the National Student Support Accelerator are two such large-scale evaluation studies that aim to produce this type of evidence while providing resources for districts to track and evaluate their own programming. Additionally, a growing number of resources have been produced with recommendations on how to best implement recovery programs, including scaling up tutoring , summer learning programs , and expanded learning time .

Ultimately, there is much work to be done, and the challenges for students, educators, and parents are considerable. But this may be a moment when decades of educational reform, intervention, and research pay off. Relying on what we have learned could show the way forward.

Related Content

Megan Kuhfeld, Jim Soland, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek, Karyn Lewis

December 3, 2020

Lindsay Dworkin, Karyn Lewis

October 13, 2021

Education Policy K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Sofoklis Goulas

June 27, 2024

June 20, 2024

Modupe (Mo) Olateju, Grace Cannon, Kelsey Rappe

June 14, 2024

- News & Insights

- All News & Insights

What can we do about COVID-related learning loss?

Experts offer evidence-based methods to close the gap following the pandemic.

Remember when the summer setback or slide among kids was a major concern for educators? Teachers would see a decrease of at least one month’s worth of school-year learning after a three-month summer break. Now imagine that decline after a dramatic shift to online learning and over 14 months of quarantine . Resources are now available to safely bring students back to school, but how do you make up for this much of a disruption in education?

When the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) released test results in the summer of 2022, the data confirmed what many educators had feared: Math and reading scores of 9-year-olds had dropped to levels that hadn’t been seen in two decades. While the decline in performance was noted across the board, the drop has been greater for Black and Brown students, especially those who lacked access to virtual learning or were enrolled in districts that delayed a return to in-person learning.

“This once-in-a-generation virus upended our country in so many ways—and our students cannot be the ones who sacrifice most now or in the long run,” said U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona in comments about the NAEP results. “We must treat the task of catching our children up in reading and math with the urgency this moment demands.”

As educators and district leaders wrestle with a host of other challenges, how can they create a plan to get students, especially the most vulnerable, back on track? What research-backed solutions might be most effective in addressing a problem that could have lasting consequences for the schoolchildren affected and our society at large?

More than math and reading

In March 2020, nearly every school in the nation closed and attempted to transition from in-person to online learning. It was a herculean challenge, but surprisingly most schools managed to pull it off relatively well. That’s the good news.

However, many schools stayed closed for more than a year. The bad news that educators are contending with now is that the prolonged isolation has had devastating consequences, both on the mental health of many children and on their academic progress.

The length of time schools were closed was determined by various factors, among them geographic location (rural schools opened more quickly than urban schools); whether or not the school was public, private or a charter school (public schools generally stayed closed longer); the school board’s political leanings; and student demographics. Parents and caregivers found themselves in the precarious situation of responding to the challenges brought on by the pandemic in addition to simultaneously supporting their children academically. The interruption also saw a loss that extended past the academics.

“We learned pretty quickly that remote learning during the pandemic was not as effective as in-person learning,” said Morgan Polikoff, a USC Rossier associate professor of education. “Student achievement fell off in that first year.

Then a lot of schools were still intermittently open, open and closed, or some were really closed through the duration of the 2021 school year.” Polikoff co-authored a report from the Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) in August 2022 which found that learning delays correlated with the amount of time students were out of the classroom or were in a virtual learning environment.

The recently released NAEP results from October 2022 showed that reading and math achievement declined significantly. Reading scores were steadier and only slipped roughly three points for both grade levels compared to 2019.

However, reading scores have slowly been taking a downward dip. On average, math scores for 4th graders decreased five points to the lowest level since 2005, and the average math scores for 8th graders decreased by eight points to the lowest level since 2003. The drop in scores was found to be more significant for Black and Brown students : Math scores declined five points for White students, 13 points for Black students and eight points for Hispanic students.

“We learned pretty quickly that remote learning during the pandemic was not as effective as in-person learning.” —USC Rossier Associate Professor Morgan Polikoff

Polikoff saw that low-income students, Black and Brown students, and White students who were out of school for more time seem to have borne the brunt of the learning loss. Polikoff pointed out Curriculum Associates’ research from 2020. After over two years since those first school closures, the declines are still there. He added: “I think there’s some evidence that we’re starting to close some of those gaps, but we’re certainly still pretty far away, especially in mathematics.”

Patricia Brent-Sanco EdD ’16 is director of equity, access and instructional services at Lynwood Unified School District, located south of Los Angeles. Her district and the community it serves were severely impacted by the pandemic. With 72,000 residents and a demographic of 94% Latino and 4.5% African American, one out of every 400 residents died of COVID-19.

“We are a four-mile city made up of essential workers. Our parents had to go to work,” said Brent-Sanco. “Our students suffered not only grief and possible loss of parents and grandparents and family members, in addition there was a loss in learning.”

The pandemic also exacerbated pre-existing inequalities . A 2021 report by the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights confirmed that the pandemic “deepened the impact of disparities to access and opportunity facing many students of color in public schools.” A McKinsey analysis found that an alarming 40% of Black and 30% of Hispanic K–12 students received no online instruction when schools were closed during the pandemic, compared with 10% of White students. Preliminary data indicated that the negative effects of the pandemic fell unevenly with regards to educational opportunities and achievements.

The sobering reports have become a call to action for educators, shedding light on how students of color have experienced a decline in academic achievement. The pandemic compounded and widened structural inequalities. “In other words, students who were struggling in school due to complications of poverty, structural racism, language difference and/or learning difference, among other factors, fell further behind during and after the pandemic,” said Patricia Burch, a USC Rossier professor of education.

For many low-income families, surviving the pandemic with their health and financial well-being intact became more important than how well their children were performing academically. Considering the hardships endured by those who were required to report to work in person, it’s hardly surprising that there is no sense of urgency among many families to address the backward slide in achievement.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics , many employees—mainly Black and Brown—worked in person, citing that only 16.2% of Hispanic and 19.7% of Black workers work remotely. And that was before the pandemic. Polikoff says the burden for addressing the problem should not rest on parents or caregivers. “I would say that the system needs to identify students who need the support and provide the support,” he added.

Helpful (or hopeful) solutions: Research and data offer learning loss remedies

Brent-Sanco says that in the Lynwood Unified School District, “the pandemic illuminated what we already knew. We know that there has to be different levels of engagement strategies for those students who face struggles outside of school [and] have environmental factors that they have to deal with when they are outside of our walls.” To address those concerns, Lynwood opened a food bank, distributed computers and wi-fi hotspots, and created a mental health collaborative with a hotline for parents. Other offerings include small-group instructions during the school day, direct instruction and guided and independent practice. In addition, a leadership academy at the elementary and middle schools instructs students on leadership lessons. Several studies have offered evidence-based methods—many overlapping—to mitigate learning loss.

Curriculum Associates conducted a mixed-methods survey with more than 300 schools whose below-level students exceeded expectations. Researchers interviewed those school leaders to understand how they managed to do so during the 2020–2021 school year. Six key practices that were most effective in supporting students emerged from the study: Cultivate educator mindsets to support student success; create a culture of data; prioritize meeting the needs of the whole child (this includes addressing mental health as well as the need for social-emotional learning); create a school environment that engages and inspires students; enhance teacher practice with more resources and support; and strengthen connections with families. A California School Boards Association report from the summer of 2020 offered useful guidelines to address learning interruption echoing similar remedies.

A Learning Policy Institute report , co-authored by USC Rossier Dean Pedro A. Noguera, from May 2021 integrated research on the science of learning and offered six guidelines for educators to address whole-child learning. The research addressed the need for “learning environments that center strong teacher–student relationships, address students’ social and emotional learning, and provide students with opportunities to construct knowledge that builds upon their experiences and social contexts in ways that deepen their academic skills.”

“The biggest mistake schools could make now is to focus narrowly and exclusively on academic achievement,” Noguera said. “They must acknowledge the tremendous social, psychological and emotional challenges that many students and staff experienced, and they must devise strategies to address all of these. This won’t be easy, but it’s the only sensible approach for moving forward.”

What's working?

The research and data reveal the needs that must be addressed. Federal funds have been earmarked to assist schools , and now the question is: How do educators and administrative leaders implement a strategy to address and respond to COVID-19 learning loss? Perhaps the pandemic created a unique opportunity to reimagine how students are taught. Some schools have explored possible options including extending the school day or academic year, summer school and grade retention . The latter, while well-intended, may carry negative consequences . Other options include tutoring , reevaluating curriculum, and teacher professional development.

“High-impact tutoring has emerged as a promising strategy for addressing learning loss,” Burch added. “From years of research, we know that high-quality tutoring can significantly change outcomes for students struggling academically. Tutoring is something that middle- and higher-income families purchase for their children. It needs to be available to all students in public schools. One-on-one or small-group tutoring with highly qualified trained staff, integrated within the school day where possible and focused on literacy and numeracy, is necessary to a functioning public education system. Districts around the country already are spending Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) dollars on this. The challenge is how to sustain and, where appropriate, scale efforts once funds dry up.”

A meta-analysis by the National Bureau of Economic Research reviewed studies of tutoring with control groups and showed that it widely increased student achievement and engagement, was shown to be cost-effective and was responsible for significant gains across the board.

Studies have proved that the combination of “high-dosage tutoring,” culturally and linguistically relevant instructions, and the building of relationships with students and parents, delivers significant gains for students. High-dose tutoring is defined as intensive learning in small groups. Consistent, carefully thought-out in-school tutoring has drastically improved learning, according to a February 2021 EdResearch for Recovery report . Brent-Sanco’s Lynwood district offers an additional layer of support to students through mentoring programs, a social emotional curriculum, homework tutoring and support to prepare students for college and a career. “It fills in the gap for anything that students might be missing,” she said.

Secretary Cardona agrees with this approach. “The evidence is clear. High-impact tutoring works, and I’ve urged our nation’s schools to provide every student who is struggling with extended access to an effective tutor,” he said in a U.S. News & World Report story from April 2022.

In addition to tutoring, improving curriculum should be a focus. “Now is the moment to double down on what we know seems to work,” Polikoff said. Through the Understanding America Study (UAS) Education Project —part of the USC Center for Economic and Social Research—he and his team are working with a nationally representative panel of American families regarding the impact of COVID on their educational experiences. The project focuses on collecting data from the subset of UAS households with at least one pre-K–12 child and/or at least one postsecondary student. “I think high-quality curriculum materials will play a very central role in addressing learning loss,” he said. In a March 2022 paper , Polikoff examined how the pandemic affected how curriculum materials were used. Whether in school, online or in a homeschool setting, his recommendations included providing access for all children to quality core curriculum materials, offering personalized curriculum tailored to student abilities and interests, and supporting teachers’ supplemental core curriculum efforts.

“The biggest mistake schools could make now is to focus narrowly and exclusively on academic achievement. They must acknowledge the tremendous social, psychological and emotional challenges that many students and staff experienced, and they must devise strategies to address all of these.” —USC Rossier Dean Pedro A. Noguera

Throughout the pandemic, teachers have been asked to juggle multiple roles, often balancing educator, mental health provider and technology support. Providing them with quality professional development and support is another option to mitigate student learning loss. Polikoff stresses the importance of equipping teachers with the right tools and providing thoughtful solutions, so they can challenge structural barriers.

Before the pandemic, there was a growing concern for student mental and emotional health and the correlation with learning. In April 2022, The New York Times surveyed school counselors on the effect the pandemic had on student mental health. The participants noted that students were not motivated in the classroom and that “emotional health is necessary for learning to happen.” As the value of the whole student increases, so has the role of student counselors. Schools are spending a portion of their COVID relief funds to address student mental support and hiring counselors.

Carol Kemler Buddin BS ’79 is a fourth-grade teacher in the Poway Unified School District in San Diego County. With 41 schools in the district, 60% of the population are students of color and 10% of students are economically disadvantaged.

When everyone returned to the classroom the previous academic year, her district recognized that students were not at the level they should be. “We saw it across the board with all of our students,” she said. For example, in her school’s beginning weeks of kindergarten, when students gain readiness routines, some were not able to write their name, hold a pencil or sit in a group. In the upper grades, some students were not able to regulate their outdoor and indoor volume or were not able to perceive personal space.

“We looked at all the data, and with that data we were able to decide how to best help our students,” Buddin added. The district used COVID funds to focus on student social and emotional health. To address food insecurity, the district provided free meals to students, and additional counselors were hired for small groups, social emotional lessons and individual student support. Technical and summer training was also provided to educators in the district. Summer school was provided in 2021 and 2022 for students who needed an extended school year for academic instruction.

"Tutoring is something that middle- and higher-income families purchase for their children. It needs to be available to all students in public schools.” —USC Rossier Professor Patricia Burch

In addition, they were able to identify students who needed additional assistance and made recommendations for tutoring. Peer-to-peer tutoring is available three days a week after school, and additional reading teachers were hired for students who needed support. “At the end of the year we just kept saying, We can’t believe what we’ve accomplished,” Buddin said. “At the beginning of the school year, some of our upper-grade students were reading at the second-grade reading level, and we were able to catch them up to their grade level by the end of the school year. We just couldn’t believe it, yet we were joyful about their successes.”

The learning challenges created by the pandemic have provided the opportunity for educators and administrators to reimagine the classroom and reevaluate current educational structures. Buddin said: “We’re all working a lot of hours, and we’re doing a lot of individual instruction right now, because we need to give the kids what they need, and that is what teachers do!”

- Morgan Polikoff

- Professor of Education

Patricia Burch

- Co-director of CEPEG

This story appeared in the USC Rossier Magazine Winter/Spring 2023 issue as “Learning Interrupted."

Article Type

Article topics, related news & insights.

December 11, 2023

The reality of COVID-19 learning loss

New study reveals a surprising parent-expert gap regarding the impact of COVID on the academic well-being of children.

Featured Faculty

November 15, 2022

What are higher education’s responsibilities in times of crisis?

Marcelo Suárez-Orozco, distinguished scholar of education, globalization and migration, spoke with the USC Rossier community on Nov. 2

- Pedro Noguera

October 7, 2022

Does bias exist in online learning?

New study explores whether race and gender of students in virtual spaces impact teacher grading and their recommendations for educational programs.

- Yasemin Copur-Gencturk

COVID Hurt Student Learning: Key Findings From a Year of Research

- Share article

Dozens of studies have come out over the past months concluding that the pandemic had a negative—and uneven—effect on student learning.

National analyses have shown that students who were already struggling fell further behind than their peers, and that Black and Latino students experienced greater declines in test scores than their peers.

But taken together, what implications do they have for school and district leaders looking for a path forward?

Here are four questions and answers, based on what we’ve learned from the most salient studies, that dig into the evidence.

Did students who stayed in remote learning longer fare worse than those who learned in person?

Generally, yes—but not in every single instance.

School buildings shut down in spring 2020 . By fall 2021, most students were back learning in person. But schools took a variety of different approaches in the middle, during the 2020-21 school year.

Several studies have attempted to examine the effects of the choices that districts made during that time period. And they found that students who were mostly in-person fared better than students who were mostly remote.

An analysis of 2021 spring state test data across 12 states found that districts that offered more access to in-person options saw smaller declines in math and reading scores than districts that offered less access. In reading, the effect was much larger in districts with a higher share of Black and Hispanic students.

Assessment experts, as well as the researchers, have urged caution about these results, noting that it’s hard to draw conclusions from results on spring 2021 state tests, given low rates of participation and other factors that affected how the tests were administered.

But it wasn’t just state test scores that were affected. Interim test scores—the more-frequent assessments that schools give throughout the year—saw declines too.

Another study examined scores on the Measures of Academic Progress assessment, or MAP , an interim test developed by NWEA, a nonprofit assessment provider. Researchers at NWEA, the American Institutes for Research, and Harvard examined data from 2.1 million students during the 2020-21 school year.

Students in districts that were remote during this period had lower achievement growth than students in districts that offered in-person learning. The effects were most substantial for high-poverty schools in remote learning districts.

Still, other research introduces some caveats.

The Education Recovery Scorecard, a collaboration between researchers at Stanford and Harvard, analyzed states’ scores on the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress. They compared these scores to the average amount of time that a district in the state spent in remote learning.

For the most part, this analysis confirmed the findings of previous research: In states where districts were remote longer, student achievement was worse. But there were also some outliers, like California. There, students saw smaller declines in math than average, even though the state had the highest closure rates on average. The researchers also noted that even among districts that spent the same amount of time in 2020-21 in remote learning, there were differences in achievement declines.

Are there other factors that could have contributed to these declines?

It’s probable. Remote learning didn’t take place in a vacuum, as educators and experts have repeatedly pointed out. But there’s not a lot of empirical evidence on this question just yet.

Children switched to virtual instruction as the pandemic unfolded around them—parents lost jobs, family members fell sick and died. In many cases, the school districts that chose remote learning served communities that also suffered some of the highest mortality rates from COVID.

The NWEA, AIR, and Harvard researchers—the group that looked at interim test data—note this. “It is possible that the relationships we have observed are not entirely causal, that family stress in the districts that remained remote both caused the decline in achievement and drove school officials to keep school buildings closed,” they wrote.

The Education Recovery Scorecard team plans to investigate the effects of other factors in future research, “such as COVID death rates, broadband connectivity, the predominant industries of employment and occupations for parents in the school district.”

Most of this data is from the 2020-21 school year. What’s happening now? Are students making progress?

They are—but it’s unevenly distributed.

NWEA, the interim assessment provider, recently analyzed test data from spring 2022 . They found that student academic progress during the 2021-22 school did start to rebound.

But even though students at both ends of the distribution are making academic progress, lower-scoring students are making gains at a slower rate than higher-scoring students.

“It’s kind of a double whammy. Lower-achieving students were harder hit in that initial phase of the pandemic, and they’re not achieving as steadily,” Karyn Lewis, the lead author of the brief, said earlier in November .

What should schools do in response? How can they know where to focus their efforts?

That depends on what your own data show—though it’s a good bet that focusing on math, especially for kids who were already struggling, is a good place to start.

Test results across the board, from the NAEP to interim assessment data, show that declines have been larger in math than in reading . And kids who were already struggling fell further behind than their peers, widening gaps with higher-achieving students.

But these sweeping analyses don’t tell individual teachers, or even districts, what their specific students need. That may look different from school to school.

“One of the things we found is that even within a district, there is variability,” Sean Reardon, a professor of poverty and inequality in education at Stanford University and a researcher on the Education Recovery Scorecard, said in a statement.

“School districts are the first line of action to help children catch up. The better they know about the patterns of learning loss, the more they’re going to be able to target their resources effectively to reduce educational inequality of opportunity and help children and communities thrive,” he said.

Experts have emphasized two main suggestions in interviews with Education Week.

- Figure out where students are. Teachers and school leaders can examine interim test data from classrooms or, for a more real-time analysis, samples of student work. These classroom-level data are more useful for targeting instruction than top-line state test results or NAEP scores, experts say.

- Districts should make sure that the students who have been disproportionately affected by pandemic disruptions are prioritized for support.

“The implication for district leaders isn’t just, ‘am I offering the right kinds of opportunities [for academic recovery]?’” Lewis said earlier this month. “But also, ‘am I offering them to the students who have been harmed most?’”

A version of this article appeared in the December 14, 2022 edition of Education Week as COVID Hurt Student Learning: Four Key Findings from A Year of Research

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 27 September 2021

Why lockdown and distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to increase the social class achievement gap

- Sébastien Goudeau ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7293-0977 1 ,

- Camille Sanrey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3158-1306 1 ,

- Arnaud Stanczak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2596-1516 2 ,

- Antony Manstead ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7540-2096 3 &

- Céline Darnon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2613-689X 2

Nature Human Behaviour volume 5 , pages 1273–1281 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

116k Accesses

152 Citations

128 Altmetric

Metrics details

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced teachers and parents to quickly adapt to a new educational context: distance learning. Teachers developed online academic material while parents taught the exercises and lessons provided by teachers to their children at home. Considering that the use of digital tools in education has dramatically increased during this crisis, and it is set to continue, there is a pressing need to understand the impact of distance learning. Taking a multidisciplinary view, we argue that by making the learning process rely more than ever on families, rather than on teachers, and by getting students to work predominantly via digital resources, school closures exacerbate social class academic disparities. To address this burning issue, we propose an agenda for future research and outline recommendations to help parents, teachers and policymakers to limit the impact of the lockdown on social-class-based academic inequality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Large socio-economic, geographic and demographic disparities exist in exposure to school closures

Elementary school teachers’ perspectives about learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

Uncovering Covid-19, distance learning, and educational inequality in rural areas of Pakistan and China: a situational analysis method

The widespread effects of the COVID-19 pandemic that emerged in 2019–2020 have drastically increased health, social and economic inequalities 1 , 2 . For more than 900 million learners around the world, the pandemic led to the closure of schools and universities 3 . This exceptional situation forced teachers, parents and students to quickly adapt to a new educational context: distance learning. Teachers had to develop online academic materials that could be used at home to ensure educational continuity while ensuring the necessary physical distancing. Primary and secondary school students suddenly had to work with various kinds of support, which were usually provided online by their teachers. For college students, lockdown often entailed returning to their hometowns while staying connected with their teachers and classmates via video conferences, email and other digital tools. Despite the best efforts of educational institutions, parents and teachers to keep all children and students engaged in learning activities, ensuring educational continuity during school closure—something that is difficult for everyone—may pose unique material and psychological challenges for working-class families and students.

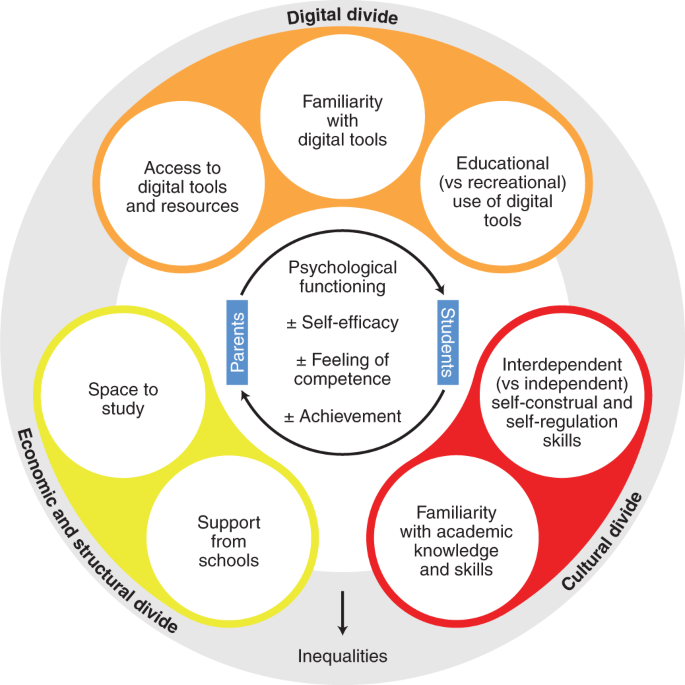

Not only did the pandemic lead to the closure of schools in many countries, often for several weeks, it also accelerated the digitalization of education and amplified the role of parental involvement in supporting the schoolwork of their children. Thus, beyond the specific circumstances of the COVID-19 lockdown, we believe that studying the effects of the pandemic on academic inequalities provides a way to more broadly examine the consequences of school closure and related effects (for example, digitalization of education) on social class inequalities. Indeed, bearing in mind that (1) the risk of further pandemics is higher than ever (that is, we are in a ‘pandemic era’ 4 , 5 ) and (2) beyond pandemics, the use of digital tools in education (and therefore the influence of parental involvement) has dramatically increased during this crisis, and is set to continue, there is a pressing need for an integrative and comprehensive model that examines the consequences of distance learning. Here, we propose such an integrative model that helps us to understand the extent to which the school closures associated with the pandemic amplify economic, digital and cultural divides that in turn affect the psychological functioning of parents, students and teachers in a way that amplifies academic inequalities. Bringing together research in social sciences, ranging from economics and sociology to social, cultural, cognitive and educational psychology, we argue that by getting students to work predominantly via digital resources rather than direct interactions with their teachers, and by making the learning process rely more than ever on families rather than teachers, school closures exacerbate social class academic disparities.

First, we review research showing that social class is associated with unequal access to digital tools, unequal familiarity with digital skills and unequal uses of such tools for learning purposes 6 , 7 . We then review research documenting how unequal familiarity with school culture, knowledge and skills can also contribute to the accentuation of academic inequalities 8 , 9 . Next, we present the results of surveys conducted during the 2020 lockdown showing that the quality and quantity of pedagogical support received from schools varied according to the social class of families (for examples, see refs. 10 , 11 , 12 ). We then argue that these digital, cultural and structural divides represent barriers to the ability of parents to provide appropriate support for children during distance learning (Fig. 1 ). These divides also alter the levels of self-efficacy of parents and children, thereby affecting their engagement in learning activities 13 , 14 . In the final section, we review preliminary evidence for the hypothesis that distance learning widens the social class achievement gap and we propose an agenda for future research. In addition, we outline recommendations that should help parents, teachers and policymakers to use social science research to limit the impact of school closure and distance learning on the social class achievement gap.

Economic, structural, digital and cultural divides influence the psychological functioning of parents and students in a way that amplify inequalities.

The digital divide

Unequal access to digital resources.