- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory

- About the Public Management Research Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, defining collaborative governance: scope and origins, an integrative framework for collaborative governance, discussion and conclusion, an integrative framework for collaborative governance.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Kirk Emerson, Tina Nabatchi, Stephen Balogh, An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory , Volume 22, Issue 1, January 2012, Pages 1–29, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mur011

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Collaborative governance draws from diverse realms of practice and research in public administration. This article synthesizes and extends a suite of conceptual frameworks, research findings, and practice-based knowledge into an integrative framework for collaborative governance. The framework specifies a set of nested dimensions that encompass a larger system context, a collaborative governance regime, and its internal collaborative dynamics and actions that can generate impacts and adaptations across the systems. The framework provides a broad conceptual map for situating and exploring components of cross-boundary governance systems that range from policy or program-based intergovernmental cooperation to place-based regional collaboration with nongovernmental stakeholders to public-private partnerships. The framework integrates knowledge about individual incentives and barriers to collection action, collaborative social learning and conflict resolution processes, and institutional arrangements for cross-boundary collaboration. It is presented as a general framework that might be applied to analyses at different scales, in different policy arenas, and varying levels of complexity. The article also offers 10 propositions about the dynamic interactions among components within the framework and concludes with a discussion about the implications of the framework for theory, research, evaluation, and practice.

Colaborativa gobernanza extrae de diversas esferas de la practica e investigación de la administración pública. Este articulo sintetiza y extiende marcos conceptuales, resultados de investigación y conocimiento basado en la práctica dentro de un marco integrativo de gobernanza colaborativa. El marco específica un conjunto de dimensiones anidadas, abarcando un gran contexto del sistema, un régimen de gobernanza colaborativa, y las dinámicas y acciones colaborativas internas que pueden generar impactos y adaptaciones a través de los sistemas. El marco proporciona un mapa conceptual amplio para situar y explorar los componentes más allá de los límites del sistema de gobernanza los cuales van desde cooperación regional intergubernamental in base a programas o políticas hasta cooperación con interesados non gubernamentales en base a su localización hasta incluir asociaciones entre entes públicas y privadas. El marco integra información acerca de los incentivos y dificultades individuales de acción colectiva, el aprendizaje social y colaborativo, los procesos de resolución de conflicto, y las configuraciones institucionales para colaboración fuera de límites. El marco general que se presenta podría ser aplicado a análisis de escalas diferentes, en diferentes áreas de política, y en diferentes niveles de complejidad. El artículo también proporciona 10 proposiciones acerca de las interacciones dinámicas entre los componentes del marco y concluye con una discusión de las implicaciones del marco para teoría, investigación, evaluación y la práctica.

Translations by Claudia N. Avellaneda, University of North Carolina Charlotte

and Nicolai Petrovsky, University of Kentucky

Collaborative governance has become a common term in the public administration literature, yet its definition remains amorphous and its use inconsistent. Moreover, the variation in the scope and scale of perspectives on collaborative governance restricts the ability of researchers to further develop and test theory. This article addresses some of the conceptual limitations associated with the study of collaborative governance. It synthesizes and extends a suite of conceptual frameworks, research findings, and practice-basedknowledge into an integrative framework for researching, practicing, and evaluating collaborative governance.

The framework for collaborative governance is integrative in several ways. First, our definition of collaborative governance is broader than what is commonly seen in the literature, and our framework draws on and applies knowledge and concepts from a wide range of fields (such as public administration, conflict resolution, and environmental management among others) to collaborative governance. This makes the framework potentially relevant to scholars and practitioners working in several applications and settings, such as collaborative public management, multipartner governance, joined-up or network government, hybrid sectoral arrangements, co-management regimes, participatory governance, and civic engagement, all of which share common characteristics with collaborative governance writ large. Second, the framework integrates numerous components of collaborative governance—from system context and external drivers through collaborative dynamics to actions, impacts, and adaptation. This enables scholars to study a collaborative governance regime (CGR) as a whole, or to focus on its various components and/or elements, while facilitating interdisciplinary research on complex, multilevel systems. Finally, it organizes several variables into a multilevel framework, enabling further analysis of the internal dynamics and causal pathways of collaborative governance and its performance. Together, these attributes can allow for the broad application of the integrative framework across sectors, settings, processes, issues, and time.

In this article, we first define collaborative governance and explore its scope and origins in the public administration and related literatures. We then present the framework for collaborative governance along with 10 propositions to guide future inquiry and theory building. We conclude with a discussion about the implications of the framework for public administration theory, research, and practice.

As a general term, “governance” refers to the act of governing, be it in the public and/or private sector. Within the context of collective action, Ostrom (1990) considers governance as a dimension of jointly determined norms and rules designed to regulate individual and group behavior. O'Leary, Bingham, and Gerard (2006 , 7) define governance as the “means to steer the process that influences decisions and actions within the private, public, and civic sectors.” More specifically, governance is “a set of coordinating and monitoring activities” that enables the survival of the collaborative partnership or institution ( Bryson, Crosby, and Stone 2006 ).

We define collaborative governance broadly as the processes and structures of public policy decision making and management that engage people constructively across the boundaries of public agencies, levels of government, and/or the public, private and civic spheres in order to carry out a public purpose that could not otherwise be accomplished. This definition allows collaborative governance to be used as a broader analytic construct in public administration and enables distinctions among different applications, classes, and scales. It responds, in part, to the observation by Ansell and Gash (2008, 544) that scholars have been focusing more “on the species rather than the genus” of collaborative governance.

Moreover, our definition of collaborative governance captures a fuller range of emergent forms of cross-boundary governance, extending beyond the conventional focus on the public manager or the formal public sector. Thus, it is broader than the definition proposed by Ansell and Gash (2008, 544) : “A governing arrangement where one or more public agencies directly engage non-state stakeholders in a collective decision-making-process that is formal, consensus-oriented, and deliberative and that aims to make or implement public policy or manage public programs or assets.” Unlike the Ansell and Gash definition, our definition does not limit collaborative governance to only formal, state-initiated arrangements, and to engagement between government and nongovernmental stakeholders. For example, our definition encompasses “multipartner governance,” which can include partnerships among the state, the private sector, civil society, and the community, as well as joined-up government and hybrid arrangements such as public-private and private-social partnerships and co-management regimes ( Agrawal and Lemos 2007 ). It also includes the myriad of community-based collaboratives involved in collective resource management (that often invite the participation of public agencies), as well as intergovernmental collaborative structures such as interstate river basin commissions governed by state and federal government representatives, and federal interagency collaboration among on public health policy or climate change science, among other types of collaborative arrangements initiated in the private or civic sectors (Emerson and Murchie 2010) . Finally, it can also be applied to or used to inform participatory governance and civic engagement, although we recognize that the extent of involvement by citizens and the public in collaborative governance can vary considerably.

Recently, several scholars have traced the multifaceted provenance of collaborative governance ( Ansell and Gash 2008 ; Bingham and O'Leary 2008 ; Cooper, Bryer, and Meek 2006 ; Fung 2006 ; Sirianni 2009 ), thus, only a brief review of some of its major connections to public administration is presented here. Specifically, we identify some of its origins in theory, its connection to broader notions of public administration and democracy, and its application to various management practices and in different management settings.

In terms of theory, several scholars connect the concept of collaborative governance with the study of intergovernmental cooperation in the 1960s ( Agranoff and McGuire 2003 ; Elazar 1962 , 1984 ), whereas others trace its roots back to the birth of American federalism itself—“the most enduring model of collaborative problem resolution” ( McGuire 2006 ). Collaborative governance has also been connected to Bentley's (1949) group theory and the subsequent theoretical reaction and evolution from Olsen's (1965) , Logic of Collective Action , to the prisoner's dilemma and game theory ( Axelrod 1984 ; Dawes 1973 ), and to the extensive common-pool resource literature ( Ostrom 1990 ).

Similarly, collaborative governance strikes at the heart of broader concepts of public administration and democracy. For many public administration scholars, collaborative governance is the new paradigm for governing in democratic systems ( Frederickson 1991 ; Jun 2002 ; Kettl 2002 ). Democracy theorists and researchers have long commented on the decline in American civic institutions, voting behavior, and social capital ( Fishkin 1991 ; Nabatchi 2010 ; Putnam 1995 ; Sirianni 2009 ; Skocpol 2002 ). Such observations have inspired new forms of public involvement and civic engagement, referred to by many as the deliberative democracy movement ( Fung and Wright 2001 ; Nabatchi 2010 ; Sirianni 2009 ; Torres 2003 ). Deliberative democracy promises citizens opportunities to exercise voice and a more responsive, citizen-centered government by embedding “governance systems and institutions with greater levels of transparency, accountability and legitimacy” ( Henton, Melville, Amsler, and Kopell 2005 , 5; see also Bryson, Crosby, and Stone 2006 ; Nabatchi 2010 ).

Collaborative governance also has roots in management practices. At its core, Kettl (2006) describes “the collaboration imperative” as cross-boundary . McGuire (2006) points out that the importance of shared administration was recognized at the start of the literature on policy implementation (see also Pressman and Wildavsky 1973 ). Intergovernmental relations and network theory helped give rise to studies about horizontal network management and collaborative public management ( Agranoff and McGuire 2001 ; Kamensky and Burlin 2004 ; Wright 1988 ). Game theory promulgated attention to interest-based negotiation and mutual gains bargaining ( Fisher, Ury, and Patton 1991 ; Raiffa 1982 ) and informed the practice of alternative dispute resolution, conflict management, and consensus building in labor relations, personnel management, contracting, and environmental and public policy ( Goldberg, Sanders, and Rogers 1992 ; O'Leary and Bingham 2003 ; Susskind, McKearnan, and Thomas-Larmer 1999 ).

Within these streams of theory and research, collaborative governance has been applied and studied in several policy contexts. It has been used by law enforcement agencies (e.g., Nicholson-Crotty and O‘Toole 2004 ), the Veteran's Health Administration (e.g., Dudley and Raymer 2001 ), and the Department of Homeland Security (e.g., Jenkins 2006 ; Taylor 2006 ). It has been applied to child and family service delivery (e.g., Berry et al. 2008 ; Graddy and Chen 2006 ; Page 2003 ; Sowa 2008 ) and to government contracting (e.g., Bloomfield 2006 ; Brown, Potoski, and Van Slyke 2007 ; Romzek and Johnston 2005 ). Collaborative governance approaches have been instrumental to local economic policy (e.g., Agranoff and McGuire 1998 ), crisis management (e.g., Farazamand 2007 ; Kettl 2006 ), collaboration between environmental agencies and state and local public health departments (e.g., Daley 2009 ), and on environmental issues such as the protection of open-spaces (e.g., Smith 2009 ), natural resources management (e.g., Durant et al. 2004 ; Koontz and Thomas 2006 ), and forest management in both the United States (e.g., Manring 2005 ) and India (e.g., Ebrahim 2004 ; Kumar, Kant, and Amburgey 2007 ).

In order to develop a useful framework for collaborative governance with which to better understand, develop, and test theory, as well as improve practice, we needed to explore and synthesize a broad array of literature. This included work in many different applied fields, such as public administration, planning, conflict management, and environmental governance among others. We began with literature that speaks directly to collaborative governance, then moved to those literatures that are more tangentially related to collaborative governance, and finally to literatures that connect to particular concepts that we identified and/or developed in the integrative framework. Our goal was to look across various research lenses to see how they might inform collaborative governance, that is, to see how different research streams could illuminate the drivers, engagement processes, motivational attributes, and joint capacities that enable shared decision making, management, implementation, and other activities across organizations, jurisdictions, and sectors.

We also searched for relevant conceptual frameworks that were grounded in empirical studies. Chief among the frameworks we reviewed are those for: cross-sector collaboration ( Bryson, Crosby, and Stone 2006 ), collaborative planning ( Bentrup 2001 ; Innes and Booher 1999 ; Selin and Chavez 1995 ), collaboration processes ( Daniels and Walker 2001 ; Ring and Van de Ven 1994 ; Thomson and Perry 2006 ; Wood and Gray 1991 ), network management ( Koppenjan and Klijn 2004 ; Milward and Provan 2000 ), collaborative public management ( Agranoff and McGuire 2001 ; Cooper, Bryer, and Meek 2006 ; Leach 2006 ), environmental governance and conflict resolution ( Agrawal and Lemos 2007 ; Emerson et al. 2009 ), and collaborative governance ( Ansell and Gash 2008 ).

In comparing these frameworks, we found expected overlap and considerable variation. The variations stem, in part, from the different research traditions, policy arenas, and scales in which these scholars work. 1 Another common challenge we encountered with these frameworks is a lack of generalizability, that is, their inapplicability across different settings, sectors, geographic and temporal scales, policy arenas, and process mechanisms. 2 Despite these variations, each of the above frameworks (and the research streams in which they are located) helped inform and refine our a priori assumptions about categories and variables in the integrative framework and helped to identify important categories and variables that we had missed.

Ostrom (2007) warns about the perils associated with constructing frameworks of this sort and the problems of creating “panaceas,” models that are either overly simplistic or overly specified and burdened with long lists of variables and exacting conditions to meet and test. We approached this dilemma by identifying a relatively small number of dimensions within which components are posited to work together in a nonlinear, interactive fashion to produce actions, which lead to outcomes (actions and impacts), and in turn adaptation.

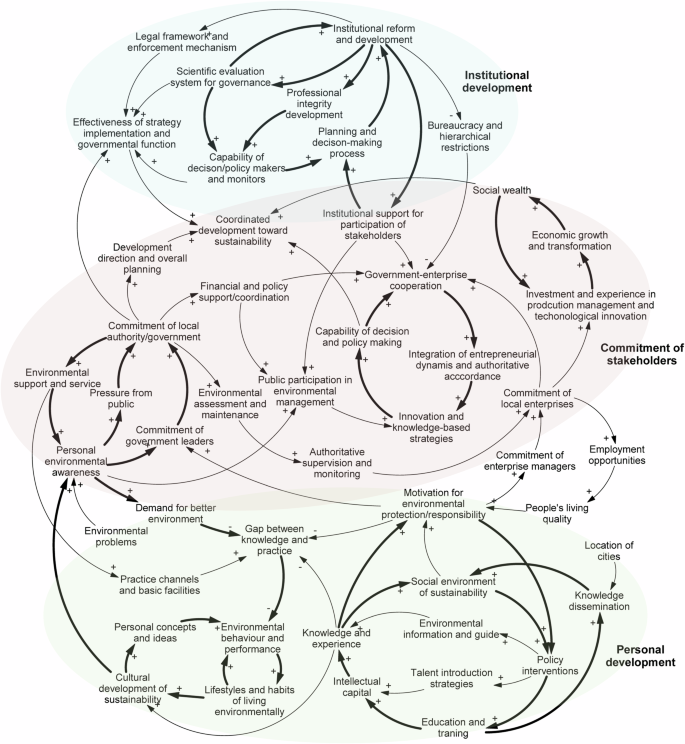

Our integrative framework for collaborative governance is depicted in figure 1 as three nested dimensions, shown as boxes, representing the general system context, the collaborative governance regime (CGR), and its collaborative dynamics and actions. The outermost box, depicted by solid lines, represents the surrounding system context or the host of political, legal, socioeconomic, environmental and other influences that affect and are affected by the CGR. This system context generates opportunities and constraints and influences the dynamics of the collaboration at the outset and over time. From this system context emerge drivers , including leadership, consequential incentives, interdependence, and uncertainty, which help initiate and set the direction for a CGR.

The Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance

The concept of a CGR is a central feature in this framework. We use the term “regime” to encompass the particular mode of, or system for, public decision making in which cross-boundary collaboration represents the prevailing pattern of behavior and activity. Crosby and Bryson (2005, 51) also use this term in their work, drawing on Krasner's (1983, 2) definition of regime as “sets of implicit and explicit principles, rules, norms, and decision-making procedures around which actors’ expectations converge in a given area.” In this framework, the CGR is depicted by the middle box with the dashed lines and contains both the collaborative dynamics and collaborative actions. Together, collaborative dynamics and actions shape the overall quality and extent to which a CGR is developed and effective.

Collaborative dynamics , represented by the innermost box with dotted lines, consist of three interactive components: principled engagement, shared motivation, and capacity for joint action. The three components of collaborative dynamics work together in an interactive and iterative way to produce collaborative actions or the steps taken in order to implement the shared purpose of the CGR. The actions of the CGR can lead to outcomes both within and external to the regime; thus, in the figure, arrows extend from the action box to demonstrate impacts (i.e., the results on the ground) and potential adaptation (the transformation of a complex situation or issue) both within the system context and the CGR itself.

In short, the structure of the integrative framework incorporates nested dimensions and their respective components. Specific elements within the components are listed in table 1 and described in more detail below. It is important to note that our framework incorporates many of the components identified in other frameworks but configures them in a way that posits causal relationships among the dimensions and their components and elements.

A Diagnostic or Logic Model Approach to Collaborative Governance

| Dimension and Components | System Context | Drivers | The Collaborative Governance Regime | Collaborative Outcomes | ||||

| Collaborative Dynamics | Outputs | |||||||

| Principled Engagement | Shared Motivation | Capacity for Joint Action | Collaborative Actions | Impacts | Adaptation | |||

| Elements within Component | - Resource Conditions - PolicyLegal Frameworks - Prior Failure to Address Issues - Political Dynamics/Power Relations - Network Connectedness - Levels of Conflict/Trust - Socio-economic/Cultural Health & Diversity | - Leadership - Consequential Incentives - Interdependence - Uncertainty | - Discovery - Definition - Deliberation - Determinaton | - Mutual Trust - Mutual Understanding - Internal Legitimacy - Shared Commitment | - Procedural/Institutional Arrangements - Leadership - Knowledge - Resources | Will depend on context and charge, but might include: - Securing Endorsements - Enacting Policy, Law, or Rule - Marshalling Resources - Deploying Staff - Siting/Permitting - Building/Cleaning Up - Enacting New Management Practice - Monitoring Implementation - Enforcing Compliance | Will depend on context and charge, but aim is to alter pre-existing or projected conditions in System Context | - Change in System Context - Change in the CGR - Change in Collaboration Dynamics |

| Dimension and Components | System Context | Drivers | The Collaborative Governance Regime | Collaborative Outcomes | ||||

| Collaborative Dynamics | Outputs | |||||||

| Principled Engagement | Shared Motivation | Capacity for Joint Action | Collaborative Actions | Impacts | Adaptation | |||

| Elements within Component | - Resource Conditions - PolicyLegal Frameworks - Prior Failure to Address Issues - Political Dynamics/Power Relations - Network Connectedness - Levels of Conflict/Trust - Socio-economic/Cultural Health & Diversity | - Leadership - Consequential Incentives - Interdependence - Uncertainty | - Discovery - Definition - Deliberation - Determinaton | - Mutual Trust - Mutual Understanding - Internal Legitimacy - Shared Commitment | - Procedural/Institutional Arrangements - Leadership - Knowledge - Resources | Will depend on context and charge, but might include: - Securing Endorsements - Enacting Policy, Law, or Rule - Marshalling Resources - Deploying Staff - Siting/Permitting - Building/Cleaning Up - Enacting New Management Practice - Monitoring Implementation - Enforcing Compliance | Will depend on context and charge, but aim is to alter pre-existing or projected conditions in System Context | - Change in System Context - Change in the CGR - Change in Collaboration Dynamics |

As we describe the framework in more detail below, we relate it to other frameworks and present general propositions about how these dimensions, components, and elements interact. These propositions represent first steps in theory building (and can be used for future theory testing) as they set forth general preliminary working assumptions about what factors lead to collaboration and how the components work together to produce desired states. In this sense, we offer not only an integrative framework (i.e., we identify the overarching variables that are important to the study of collaborative governance and how they generally relate) but also offer some initial pathways for integrating existing theory and building new theory based on the framework (i.e., through the propositions, we begin to develop theory, for example, about what factors lead to collaboration, what leads to the success and effectiveness of collaborative governance, and how a CGR may achieve adaptation). 3

General System Context

Collaborative governance is initiated and evolves within a multilayered context of political, legal, socioeconomic, environmental, and other influences ( Borrini-Feyerabend 1996 ). This external system context creates opportunities and constraints and influences the general parameters within which a CGR unfolds. Not only does the system context shape the overall CGR but the regime itself can also affect the system context through the impact of its collaborative actions. 4

Researchers have recognized several chief elements in the system context that may distinguish or influence the nature and prospects of a CGR, including resource conditions in need of improving, increasing, or limiting (e.g., Ostrom 1990 ); policy and legal frameworks, including administrative, regulatory, or judicial (e.g., Bingham 2008 ); prior failure to address the issues through conventional channels and authorities (e.g., Bryson and Crosby 2008 ); political dynamics and power relations within communities and among/across levels of government (e.g., Ansell and Gash 2008 ); degree of connectedness within and across existing networks (e.g., Selin and Chavez 1995 ); historic levels of conflict among recognized interests and the resulting levels of trust and impact on working relationships (e.g., Ansell and Gash 2008 ; Radin 1996 ; Thomson and Perry 2006 ); and socioeconomic and cultural health and diversity (e.g., Sabatier et al. 2005 ).

The system context is represented in this framework, not as a set of starting conditions but as a surrounding three-dimensional space because external conditions (e.g., an election, economic downturn, extreme weather event, or newly enacted regulation) may influence the dynamics and performance of collaboration not only at the outset but at any time during the life of the CGR, thus opening up new possibilities or posing unanticipated challenges.

Although the literature broadly recognizes that the “conditions present at the outset of collaboration can either facilitate or discourage cooperation among stakeholders and between agencies and stakeholders” ( Ansell and Gash 2008, 550 ), many frameworks tend to conflate system context and conditions with the specific drivers of collaboration (e.g., Ansell and Gash 2008 ; Bentrup 2001 ; Thomson and Perry 2006 ; for an exception, see Bryson, Crosby, and Stone 2006 ). In contrast, our framework separates the contextual variables from essential drivers, without which the impetus for collaboration would not successfully unfold. These drivers include leadership, consequential incentives, interdependence, and uncertainty.

Leadership , the first essential driver, refers to the presence of an identified leader who is in a position to initiate and help secure resources and support for a CGR. The leader may, by virtue of her own stature, be a member of one of the parties or the deciding official or may be located within a trusted boundary organization. Regardless, she should possess a commitment to collaborative problem solving, a willingness not to advocate for a particular solution, and exhibit impartiality with respect to the preferences of participants ( Bryson, Crosby, and Stone 2006 ; Selin and Chavez 1995 ). In addition, the willingness of a leader to absorb the high (and potentially constraining) transaction costs of initiating a collaborative effort, for example, by providing staffing, technologies, and other resources may help reinforce the endeavor (e.g., Schneider et al. 2003 ).

Consequential incentives refer to either internal (problems, resource needs, interests, or opportunities) or external (situational or institutional crises, threats, or opportunities) drivers for collaborative action. Such incentives are consequential in that the presenting issues are salient to participants, the timing or pressure for solutions is ripe, and the absence of attention to the incentives may have negative impacts ( Selin and Chavez 1995 ). It should be noted, however, that not all consequential incentives are negative. For example, the availability of a grant or new funding opportunity may lead to the development of a collaborative initiative. Nevertheless, such incentives (positive or negative) must exist to induce leaders and participants to engage together.

Interdependence , or when individuals and organizations are unable to accomplish something on their own, is a broadly recognized precondition for collaborative action ( Gray 1989 ; Thomson and Perry 2006 ). In a sense, this is the ultimate consequential incentive. This driver is referred to as “sector failure” by Bryson, Crosby, and Stone (2006) and as “constraints on participation” by Ansell and Gash (2008) .

The final driver, uncertainty , is a primary challenge for managing “wicked” societal problems ( Koppenjan and Klijn 2004 ; Rittel and Webber 1973 ). Uncertainty that cannot be resolved internally can drive groups to collaborate in order to reduce, diffuse, and share risk. Collective uncertainty about how to manage societal problems is also related to the driver of interdependence. Were parties or organizations endowed with perfect information about a problem and its solution, they would be able to act independently to pursue their interests or respond to risk ( Bentrup 2001 ). There can also be individual uncertainty about the extent to which conventional avenues for solutions or satisfaction (sometimes referred to as the Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement in conflict management literature) can be relied on to produce the intended result.

One or more of the drivers of leadership, consequential incentives, interdependence, or uncertainty are necessary for a CGR to begin. The more drivers present and recognized by participants, the more likely a CGR will be initiated.

Collaborative Governance Regime

As previously described, the integrative framework introduces the term CGR, to denote a system in which cross-boundary collaboration represents the predominate mode for conduct, decision making, and activity. The form and direction of the CGR is shaped initially by the drivers that emerge from the system context; however, the development of the CGR, as well as the degree to which it is effective, is influenced over time by its two components: collaborative dynamics and collaborative actions. Below, we describe these two components, as well as the various elements embedded within them.

Collaborative Dynamics

Essential drivers energize or induce the convening of participants by reducing the initial formative costs of collective action and setting the collaborative dynamics in motion. These dynamics and the actions they produce over time constitute a CGR. Several scholars portray collaborative processes as a linear sequence of cognitive steps or stages that occur over time from problem definition to direction setting and implementation ( Daniels and Walker 2001 ; Gray 1989 ; Selin and Chavez 1995 ). In contrast, and consistent with Ansell and Gash (2008) and Thomson and Perry (2006) , we view the stages within collaborative dynamics as cyclical or iterative interactions. We focus on three interacting components of collaborative dynamics: principled engagement, shared motivation, and capacity for joint action.

Principled Engagement

Principled engagement occurs over time and may include different stakeholders at different points and take place in face-to-face or virtual formats, cross-organizational networks, or private and public meetings, among other settings. Through principled engagement, people with differing content, relational, and identity goals work across their respective institutional, sectoral, or jurisdictional boundaries to solve problems, resolve conflicts, or create value ( Cahn 1994 ; Cupach and Canary 1997 ; Lulofs and Cahn 2000 ). Although face-to-face dialogue is advantageous at the outset, it is not always essential, particularly when conflict may be low and shared values and objectives quickly surface.

We call this component in our framework “principled” engagement to adhere to the basic espoused principles articulated broadly in both practice and research, including fair and civil discourse, open and inclusive communications, balanced by representation of “all relevant and significant different interests” ( Innes and Booher 1999, 419 ), and informed by the perspectives and knowledge of all participants (see also Ansell and Gash 2008 ; Carlson 2007 ; Henton et al. 2005 ; Leach 2006 ; O'Leary, Bingham, and Gerard 2006 ; Susskind, McKearnan, and Thomas-Larmer 1999 ). 5

Before specifying the nested elements within principled engagement, it is important to discuss the participants. Who the participants are and who they represent are of signal importance to collaboration. Participants may also be called members, stakeholders, parties, partners, or collaborators, depending on the context and objectives of the CGR. They may represent themselves, a client, a constituency, a decision maker, a public agency, an NGO, a business or corporation, a community, or the public at large. Their selection may vary considerably, ranging from state-based participants (e.g., expert administrators and elected representatives), to mini-publics (e.g., professional or lay stakeholders or randomly selected, self-selected, or recruited individuals), and diffuse members of the public ( Fung 2006 ). Their number may range from 2 to 10,000 or more ( Emerson et al. 2009 ). Moreover, each participant brings a set of individual attitudes, values, interests, and knowledge in addition to the cultures, missions, and mandates of the organizations or constituents they represent ( Bardach 2001 ).

There is general agreement in practice and research that getting the “right” people to the table is important ( Ansell and Gash 2008 ; Carlson 2007 ; Carpenter and Kennedy 2001 ; Emerson et al. 2009 ; Susskind, McKearnan, and Thomas-Larmer 1999 ). Inclusion and diversity are valued not only as normative organizing principles but also for instrumental reasons—they give voice to multiple perspectives and different interests, allowing the development of more thoughtful decisions that take a broader view of who will benefit or be harmed by an action ( Beierle and Cayford 2002 ; Sirianni 2009 ). Moreover, the relative and combined power of the participants can enable or disable subsequent agreements or collective courses of action. 6

Principled engagement occurs over time through the iteration of four basic process elements: discovery, definition, deliberation, and determination. These build on collaborative learning phases by Daniels and Walker (2001) and may be thought of as elements of a dynamic social learning process (e.g., Bandura 1977 ). Through this iterative process, collaboration partners develop a shared sense of purpose and a shared theory of action for achieving that purpose. This shared theory of action includes the group's understanding of the size of the problem or challenge it is addressing, as well as the scope and scale of the group's chosen activities or interventions ( Koontz et al. 2004 ; Leach and Pelkey 2001 ).

Discovery refers to the revealing of individual and shared interests, concerns, and values, as well as to the identification and analysis of relevant and significant information and its implications. At the outset, discovery may be focused on identifying shared interests; later, it might be observed in joint fact-finding and more analytic investigation ( Ehrmann and Stinson 1999 ; Ozawa 1991 ). The definition process characterizes the continuous efforts to build shared meaning by articulating common purpose and objectives; agreeing on the concepts and terminology participants will use to describe and discuss problems and opportunities; clarifying and adjusting tasks and expectations of one another; and setting forth shared criteria with which to assess information and alternatives (for discussions, see Bentrup 2001 ; Pahl-Wostl 2007 ).

Deliberation , or candid and reasoned communication, is broadly celebrated as a hallmark and essential ingredient of successful engagement. The quality of deliberation, especially when participants have differing interests and perspectives, depends on both the skillful advocacy of individual and represented interests and the effectiveness of conflict resolution strategies and interventions, described in a recent National Research Council (2009) report as “deliberation with analysis.” Hard conversations, constructive self-assertion, asking and answering challenging questions, and expressing honest disagreements are part and parcel of effective communication across boundaries. Collaborative governance creates the “safe” space for such deliberation to take place. Advocates of deliberative democracy, public engagement, and alternative dispute resolution agree on the importance of enabling the exercise of meaningful “voice” through deliberation. As Roberts (2004 , 332) notes, “Deliberation is not ‘the aggregation of interests.’ It requires thoughtful examination of issues, listening to others' perspectives, and coming to a public judgment on what represents the common good.”

Finally, principled engagement incorporates the processes of making enumerable joint determinations , including procedural decisions (e.g., setting agendas, tabling a discussion, assigning a work group) and substantive determinations (e.g., reaching agreements on action items or final recommendations). Substantive determinations are often considered one of the outputs or end products of collaboration or conflict resolution ( Dukes 2004 ; Emerson et al. 2009 ). In an ongoing CGR, however, many substantive determinations are made over time; these are integrated in the framework as a repeating element within principled engagement.

Collaboration theory and practice suggest that determinations produced through strong engagement processes will be fairer and more durable, robust, and efficacious ( Innes and Booher 1999 ; Sipe and Stiftel 1995 ; Susskind and Cruikshank 1987 ). However, there is limited research on the quality of collaborative determinations and the extent to which they lead to actions required for implementation ( Bingham and O'Leary 2008 ). Most practitioners and researchers, however, advance consensus building as the foundational method for making group determinations (e.g., Innes and Booher, 1999 ; Susskind and Cruikshank 1987 ), although this does not mean that consensus as a decision rule is always required or achieved ( Susskind, McKearnan, and Thomas-Larmer 1999 ).

Principled engagement is generated and sustained by the interactive processes of discovery, definition, deliberation, and determination. The effectiveness of principled engagement is determined, in part, by the quality of these interactive processes.

Shared Motivation

We define shared motivation as a self-reinforcing cycle consisting of four elements: mutual trust, understanding, internal legitimacy, and commitment. All but legitimacy are included in the Ansell and Gash (2008) configuration of collaborative process. Shared motivation highlights the interpersonal and relational elements of the collaborative dynamics and is sometimes referred to as social capital ( Colman 1988 ; Putnam 2000 ; Putnam, Leonardi, and Nanetti 1993 ). Shared motivation is, in part, initiated by principled engagement, and in that sense, it is an intermediate outcome; however, once initiated, shared motivation also reinforces or accelerates the principled engagement process ( Huxham and Vangen 2005 ).

The first element of shared motivation (and the initial outgrowth of principled engagement) is the development of trust , which happens over time as parties work together, get to know each other, and prove to each other that they are reasonable, predictable, and dependable ( Fisher and Brown 1989 ). Trust has been a long-recognized sine qua non of collaboration ( Huxham and Vangen 2005 ; Koppenjan and Klijn 2004 ; Leach and Sabatier 2005 ; Ostrom 1998 ). In networks, for example, trust has been found to be instrumental in reducing transaction costs, improving investments and stability in relations, and stimulating learning, knowledge exchange, and innovation ( Koppenjan and Klijn 2004 ). We conceptualize the mechanism by which trust produces such outcomes as an initial pivotal element within the cycle of shared motivation, that is, trust generates mutual understanding, which in turn generates legitimacy and finally commitment. Trust enables people to go beyond their own personal, institutional, and jurisdictional frames of reference and perspectives toward understanding other peoples’ interests, needs, values, and constraints ( Bardach 1998 ; Ring and Van de Ven 1994 ; Thomson and Perry 2006 ).

This forms the basis of mutual understanding , the second element in shared motivation. At an interpersonal level, trust enables people to see and then appreciate differences in others. It enables people to reveal themselves to others and hence be seen and appreciated by them ( Daniels and Walker 2001 ; Gray 1989 ). Mutual understanding is not “shared understanding” as discussed by Ansell and Gash (2008) where participants agree on a shared set of values or goals; rather, mutual understanding specifically refers to the ability to understand and respect others’ positions and interests even when one might not agree.

Repeated, quality interactions through principled engagement will help foster trust, mutual understanding, internal legitimacy, and shared commitment, thereby generating and sustaining shared motivation.

Once generated, shared motivation will enhance and help sustain principled engagement and vice versa in a “virtuous cycle.”

Capacity for Joint Action

The purpose of collaboration is to generate desired outcomes together that could not be accomplished separately. As Himmelman (1994) describes it, collaboration is engaging in cooperative activities to enhance the capacity of both self and others to achieve a common purpose. Thus, the CGR must generate a new capacity for joint action that did not exist before and sustain or grow that capacity for the duration of the shared purpose. The necessary capacity building is specified during principled engagement, derived from the participants’ explicit or tacit theory of action needed to accomplish their collaborative purpose, and likely to be influenced by the scope and scale of the group's objectives and activities. This new capacity is also the basis for group empowerment, which is frequently discussed as a democratic principle underlying collaboration (e.g., Leach 2006 ).

Borrowing from Saint-Onge and Armstrong's (2004, 17) definition of capabilities for conductive organizations, we view the capacity for joint action as “a collection of cross-functional elements that come together to create the potential for taking effective action” and serve “as the link between strategy and performance” (2004, 19). In our framework, capacity for joint action is conceptualized as the combination of four necessary elements: procedural and institutional arrangements, leadership, knowledge, and resources. All the collaborative frameworks we studied recognize the importance of formal and informal rules and protocols, institutional design, and other structural dimensions to on-going collaboration. Most also identify leadership as an important element. The levels of these elements must be sufficient enough to accomplish agreed upon goals. Moreover, capacity for joint action can be viewed as an intermediate outcome of the interacting cycles of principled engagement and shared motivation. However, as joint capacity develops, it can also strengthen or improve the engagement and shared motivation cycles, and in synergy, assure more effective actions and impacts. One or more of the elements of capacity for joint action may be offered upfront as an inducement to collaboration by the initiating leader and/or be developed over time through the interaction of principled engagement and shared motivation.

Procedural and institutional arrangements encompass the range of process protocols and organizational structures necessary to manage repeated interactions over time. The conflict resolution literature indentifies dimensions such as agreements to mediate ground rules, operating protocols, decision rules, and so forth, but these are insufficient for longer term collaborations where informal norms must be supplemented with more formal institutional design factors such as charters, by-laws, rules, and regulations. In other words, larger, more complex, and long-lived collaborative networks require more explicit structures and protocols for the administration and management of work ( Milward and Provan 2000 , 2006 ).

These procedural and institutional arrangements must be defined at both the intraorganizational level (i.e., how a single group or organization will govern and manage itself in the collaborative initiative) and at the interorganizational level (i.e., how the groups of organizations will govern and manage together in the CGR and integrate with external decision making authorities). In general, the internal authority structure of collaborative institutions tends to be less hierarchical and stable, and more complex and fluid, than those found in traditional bureaucracies ( Bryson, Crosby, and Stone 2006 ; Huxham and Vangen 2005 ). Such structures and protocols may vary by function, for example, taking on the shape of informational, developmental, outreach, or action networks ( Agranoff and McGuire 2003 ), and by form, for example, being administered as a self-managing system, by a designated lead agency or agencies, or with the creation of a new governmental structure ( Milward and Provan 2006 ).

The protocols that govern collaborative endeavors may be informal “norms of reciprocity” and/or more formal rules of network interactions ( Thomson and Perry 2006 ). They may also distinguish interaction rules from arena rules in networks ( Koppenjan and Klijn 2004 ). The common pool resource literature has contributed greatly to our understanding of the importance of rules, including constitutional rules, laying out the basic scope and authorities for joint effort, decision making rules, and operating procedures ( Bingham 2009 ; Ostrom 1990 ).

The second element in capacity for joint action is leadership . The importance of leadership in collaborative governance is widely confirmed ( Ansell and Gash 2008 ; Bingham and O'Leary 2008 ; Carlson 2007 ; Saint-Onge and Armstrong 2004 ; Susskind and Cruikshank 1987 ). Leadership can be an external driver (as we posited earlier), an essential ingredient of collaborative governance itself, and a significant outgrowth of collaboration. Moreover, collaborative governance demands and cultivates multiple opportunities and roles for leadership ( Agranoff and McGuire 2003 ; Bryson, Crosby, and Stone 2006 ). These include the leadership roles of sponsor, convener, facilitator/mediator, representative of an organization or constituency, science translator, technologist, and public advocate, among others. Certain leadership roles are essential at the outset, others more critical during moments of deliberation or conflict, and still others in championing the collaborative determinations through to implementation ( Agranoff 2006 ; Bryson, Crosby, and Stone 2006 ; Carlson 2007 ).

Knowledge is the third element in the capacity for joint action. In many ways, it is the currency of collaboration. It is knowledge, once guarded, that is shared with others; knowledge jointly needed that is generated together. It is contested knowledge that requires full consideration; and incomplete knowledge that must be balanced and enhanced with new knowledge. In essence, collaboration requires the aggregation, separation, and reassembly of data and information, as well as the generation of new, shared knowledge. “Knowledge is information combined with understanding and capability: it lives in the minds of people … Knowledge guides action, whereas information and data can merely inform or confuse” ( Groff and Jones 2003 ). Called part of the assets of human capital by Agranoff (2008, 165) , the term “knowledge” in this framework refers to the social capital of shared knowledge that has been weighed, processed, and integrated with the values and judgments of all participants.

Ansell and Gash (2008, 544) note, “As knowledge becomes increasingly specialized and distributed and as institutional infrastructures become more complex and interdependent, the demand for collaboration increases.” Scholars seem to agree, and several have studied and written explicitly about the importance of knowledge management to collaboration across networks (e.g., Agranoff 2007 , 2008 ; Cross and Parker 2004 ). For Saint-Onge and Armstrong (2004) , the ability to transmit high-quality knowledge effectively within and across organizations is the essence of “conductivity” in high-performance organizations and networks. Knowledge is also the central element in adaptive resource management models, where conditions of scientific or resource uncertainty lead parties to cooperate in management experiments to test and build knowledge for better and more enduring management practices ( Holling 1978 ).

Principled engagement and shared motivation will stimulate the development of institutional arrangements, leadership, knowledge, and resources, thereby generating and sustaining capacity for joint action.

The necessary levels for the four elements of capacity for joint action are determined by the CGR's purpose, shared theory of action, and targeted outcomes.

The quality and extent of collaborative dynamics depends on the productive and self-reinforcing interactions among principled engagement, shared motivation, and the capacity for joint action.

Collaborative Actions

Collaborative governance is “generally initiated with an instrumental purpose in mind” ( Huxham et al. 2000, 340 ), that is, to propel actions that “could not have been attained by any of the organizations acting alone” ( Huxham 2003 , 403; see also Agranoff and McGuire 2003 ; Bingham and O'Leary 2008 ). Collaborative actions should be at the heart of any collaborative governance framework, but they have received limited attention and are often left unspecified ( Thomas and Koontz, 2011 ). When addressed, collaborative action is usually seen as the major outcome of a linear process and is sometimes conflated with impacts. However, “Processes and outcomes cannot be neatly separated in consensus building [and CGRs] because the process matters in and of itself and because the process and outcome are likely to be tied together” ( Innes and Booher 1999, 415 ).

Nevertheless, effective CGRs should provide new mechanisms for collective action (e.g., Donahue 2004 ) determined by collaboration partners in accordance with their expressed or implied theory of action for accomplishing their preferred outcomes. Depending on the context and charge of the CGR, such actions may include, for example, securing endorsements, educating constituents or the public, enacting policy measures (new laws or regulations), marshalling external resources, deploying staff, siting and permitting facilities, building or cleaning up, carrying out new management practices, monitoring implementation, and enforcing compliance. Some CGRs have very broad aims (e.g., taking actions related to strategic development or within a particular policy issue or area), whereas others have narrower goals (e.g., taking action on a particular project or gathering and analyzing specific information) ( Huxham et al. 2000 ). Collaborative actions may be conducted in concert by all the partners or their agents, by individual partners carrying out tasks agreed on through the CGR or by external entities responding to recommendations or directions from the CGR.

The appropriateness of the actions should be viewed in light of the CGR's shared theory of action and understood within the system context, where such actions by individual people or organizations would not otherwise be taken. Collaborative action will be difficult to accomplish, much less assess, if shared goals and an operating rationale for taking action are not made explicit. “Common wisdom” implies “that it is necessary to be clear about the aims of joint working if partners are to work together to operationalize policies … . The common practice, however, appears to be that the variety of organizational and individual agendas that are present in collaborative situations make it difficult to agree on aims in practice” ( Huxham 2003, 404 ).

Collaborative actions are more likely to be implemented if 1) a shared theory of action is identified explicitly among the collaboration partners and 2) the collaborative dynamics function to generate the needed capacity for joint action.

The impacts derived from CGRs have also been challenging to operationalize, in part because of the confusion in the literature about the impacts, effects, outputs, and/or outcomes of collaboration ( Thomas and Koontz, 2011 ). For example, Innes and Booher (1999) refer to a range of direct and indirect impacts as first-, second-, and third-order effects that may emerge from a collaborative initiative. Similarly, Lubell, Leach, and Sabatier (2009) refer to different kinds of first-order, second-order, and third-order outputs. Problematically, these constructions of impacts/effects/outputs tend to conflate collaborative dynamics with the overall CGR and its outcomes. For the theory and practice of collaborative governance to develop, we need to generate better conceptual clarity about impacts.

The impacts resulting from collaborative action are likely to be closer to the targeted outcomes with fewer unintended negative consequences when they are specified and derived from a shared theory of action during collaborative dynamics.

Collaborative governance is frequently advocated because of its potential to transform the context of a complex situation or issue. Indeed, one of the “most important consequences [of collaborative governance] may be to change the direction of a complex, uncertain, evolving situation, and to help move a community toward higher levels of social and environmental importance” ( Innes and Booher 1999, 413 ). In our framework, we identify such potential transformative change as adaptation to impacts fostered by CGRs. For example, based on the impacts of collaborative action, problems are solved (or not), new research findings confirm selected management practices (or do not), and different sets of challenges or opportunities arise. Each of these may alter the general system context.

We also propose in our framework the potential for adaptation in the CGR itself. This may occur indirectly as a result of changes in the system context (e.g., thus changing the drivers to collaboration) or directly in response to the perceived effectiveness of actions and impacts (e.g., leading to a new charge or mandate, the addition of new stakeholders, a new round of knowledge generation or resource leverage, or the decision to disband the collaboration). Innes and Booher (1999) classify many of these adaptations as third-order effects.

CGRs will be more sustainable over time when they adapt to the nature and level of impacts resulting from their joint actions.

A review of the integrative framework for collaborative governance and the resulting propositions is in order. These propositions are a first cut at describing the causal mechanisms that link the components and elements of the nested dimensions in the framework; they are presented as preliminary working assumptions in need of future testing and validation.

We assert that collaborative governance unfolds within a system context that consists of a host of political, legal, socioeconomic, environmental, and other influences. This system context creates opportunities and constraints, and influences the dynamics and performance of collaboration at the outset and over time. Emerging from this system context are drivers , including leadership, consequential incentives, interdependence, and uncertainty. These drivers generate the energy for the initiation of a CGR and set its initial direction. We propose that one or more of these four drivers must be present to start a CGR and that the presence of more drivers increases the likelihood that such a regime will be initiated (Proposition 1).

Once a CGR has been initiated, collaborative dynamics and its three components are set in motion. The first component, principled engagement , encompasses the interaction of four basic process elements: discovery, definition, deliberation, and determination. We posit that the principled engagement is generated and sustained by these four elements and that quality and effectiveness of principled engagement will depend on the nature of the interaction among these four elements over time (Proposition 2). The second component, shared motivation , also consists of four elements: trust, mutual understanding, internal legitimacy, and shared commitment. We posit that principled engagement fosters these four elements, thus generating and sustaining shared motivation (Proposition 3). Moreover, we argue that once generated, shared motivation will further enhance and sustain principled engagement and vice versa in a “virtuous cycle” (Proposition 4). The third component of collaborative dynamics is the generation of capacity for joint action , which is also a function of four elements: procedural and institutional arrangements, leadership, knowledge, and resources. We posit that principled engagement and shared motivation assist with the development of these elements, thus generating and sustaining capacity for joint action (Proposition 5). Moreover, we suggest that the necessary levels of each element will vary based on the CGR's purpose, shared theory of action, and targeted outcomes (Proposition 6). Finally, with regard to collaborative dynamics, our summative proposition asserts that the quality and extent of these dynamics depends on the nature of the self-reinforcing interactions among principled engagement, shared motivation, and the capacity for joint action (Proposition 7).

The components of collaborative dynamics (principled engagement, shared motivation, and capacity for joint action) interact over time synergistically and propel collaborative action by the CGR. We posit that collaborative actions are more likely to be implemented if they are in line with an articulated shared theory of action and supported by the necessary capacity for joint action (Proposition 8). We also propose that the resulting impacts from collaborative action are likely to be closer to those intended and targeted by the regime with fewer unintended negative consequences if they have been specified in a shared theory of action developed through collaborative dynamics (Proposition 9). Finally, the potential for adaptation exists both within the system context and the CGR itself. We suggest that CGRs will be more sustainable over time when they adapt to the nature and level of impacts resulting from their joint actions (Proposition 10).

We recognize that this integrative framework covers a lot of ground. It incorporates concepts from a wide range of literature and broadens the scope of collaborative governance beyond previous constructs. The framework identifies several general sets of variables (i.e., dimensions, components, and elements), as well as the relationships among those variables, that will be of interest to scholars and practitioners of collaborative governance. In addition, derived from the framework are several propositions that both integrate existing theory and seek to build new theory about how the variables of collaborative governance interact to shape events and outcomes. Although the breadth of the framework is a strength, it also makes it difficult to adequately describe within the bounds of this article. By developing a framework that encompasses the context, drivers, engagement processes, motivational attributes, and joint capacities that enable shared decision making, management, implementation, and other activities across organizations, jurisdictions, and sectors, we have limited the space available to cover in depth the elements of each component and develop the full suite of causal pathways proposed.

Nevertheless, the framework itself improves upon existing frameworks for collaborative governance in several ways. First, it examines collaborative governance broadly and treats it as an emergent system, a new kind of regime for cross-boundary governance. In doing so, it encompasses a wider range of collaborative initiatives than other definitions and extends beyond the typical focus on the public sector and the public manager to include the myriad of collaboratives initiated in the public, private, and civic sectors. Second, the framework specifies the components of the CGR in a way that integrates a range of factors identified in research into an operational system and suggests some general and very specific causal linkages. Although several frameworks acknowledge the iterative and dynamic nature of collaboration, this framework more explicitly builds that vibrant nature into its construction. Third, the framework also situates the CGR in the broader context with which it interacts. The regime is influenced by surrounding conditions and initiated by specific drivers, and the regime produces impacts affecting those surrounding conditions, as well as the regime itself and its collaborative dynamics. Finally, the framework goes beyond others in distinguishing actions from impacts and tracing the potential for adaptation of the system context and the CGR itself.

The framework also provides a wealth of opportunities for future empirical research. At the most basic level, the generic nature of the framework should enable comparative analyses of CGRs across different system contexts and policy arenas. The depth of the framework, from the dimensions to individual elements, lends itself to thick description in individual or comparative case studies. The breadth of the framework enables efforts to gather more consistent data on a range of indicators from a large set of cases to test the propositions or specific hypotheses relating to the components, their elements, and their interactions.

More specifically, there are numerous research opportunities at the framework, theory, and model levels articulated by Ostrom (2005) . First, the framework itself would benefit from critical applications to cases and examples of collaborative governance. It would be useful to closely examine the components and their interrelationships to describe their strengths and weaknesses, limits of applicability, areas where we have the most and least empirical evidence, and the potential role of various disciplines in contributing to pieces of the framework. Doing so could help identify the pieces of the framework that have the most empirical or practical support, as opposed to the pieces that are, at this point, more speculative. In turn, such research could help confirm or adjust the more speculative pieces. Moreover, we believe that the integrative framework can be applied usefully at different scales, in diverse policy arenas, and various levels of complexity. Future research can examine these assumptions, for example, by exploring how certain pieces of the framework apply in different settings such as community policing, environmental issues, or social services. Typologies of different kinds of CGRs can be envisioned, which in turn can generate future empirical analyses of the framework overall or of the interactions among different components and elements.

Second, several theory testing possibilities exist. The propositions derived from the framework begin to build a general predictive theory for collaborative governance through an instrumental systems approach, as opposed to a prescriptive theory based on normative assumptions. As noted before, these working assumptions need to be tested and validated or revised. Moreover, although the framework encompasses many interactive components and elements, we do not mean to suggest that all are necessary all the time or at the same level of quality or to the same extent. Additional research is needed to discover which relationships matter in what contexts, that is, researchers need to identify where, when, and why which components are necessary, and to what degree, for collaborative success. For instance, in studying the four specified drivers, one might test which are most important. Our preliminary thought on this is that leadership is an essential driver, without which collaborative regimes would not be initiated. However, without at least one or some combination of the other drivers (consequential incentives, interdependence, and/or uncertainty), a CGR is unlikely to continue. Likewise, scholars could examine which element or elements in each of the components of collaborative dynamics (principled engagement, shared motivation, and capacity for joint action) are essential for collaborative success. In a similar research direction, some of the coauthors are currently working on the relationship between collaborative capacity and adaptation, addressing how collaborative capacity might generate specific adaptive capacity and enhance adaptive action in CGRs addressing natural resource issues.

More work is also needed to identify and explain the causal mechanisms that drive collaborative initiatives. Future research will be helpful in clarifying how the different components and elements in the framework emerge and how they relate to one another. For example, the drivers identified in the framework explain why collaboration might emerge but do not yet explain how specific drivers might affect the nature of the CGR differently or if and how the drivers continue to sustain the CGR as it evolves over time. Likewise, future research can explore the critical factors that influence the sustainability of CGRs. For example, one might examine what many have proposed in the literature that small initial successes (low hanging fruit) are essential to keep a CGR going in the its early stages (or that such successes are not sufficient in the long run). This would require defining different levels of success (e.g., initial development of joint capacity for action, different kinds of actions, actions plus impacts, and so forth), as well as tracking the longevity of the CGR, holding other components and elements constant.

Finally, researchers can develop and test specific models and hypotheses relating to the components, their elements, and their interactions. For example, table 1 suggests a way in which to view the integrative framework as a logic model that can be used to test intermediate outputs (actions) and end outcomes (impacts and adaptation) and become the basis for case evaluation and performance evaluation for program management ( Thomas and Koontz, 2011 ). Similarly, other multilevel modeling methodologies may be employed to test more rigorously the contributions of several interrelated factors to specified outcomes ( Arnold 1992 ; Emerson et al. 2009 ; O'Connell and McCoach 2004 ). For such evaluation to begin, however, additional research is needed to operationalize the components and elements so that they can be tested. Work to develop indicators and measures for the dimensions, components, and elements in the integrative framework is currently underway.

In terms of practice, the framework offers public managers and collaboration and conflict resolution practitioners a conceptual map by which to navigate the various dimensions, components, and elements of collaborative governance. The set of drivers provide useful considerations for deciding whether and when to invest in a CGR. Making the collaborative dynamics dimension explicit with participants at the outset can assist with the codesign of the most effective and appropriate CGR. Drawing attention to the elements within principled engagement, shared motivation, and the capacity for joint action can stimulate a shared perspective on needed strategic directions and on progress made to date. Working to articulate the targeted outcomes and coproduce a shared theory of action to affect those outcomes and the criteria by which to assess effective outcomes can enable participants to sharpen their sights and their pencils. Finally, understanding that a CGR is likely, if not expected, to adapt over time further enables the development of innovative learning systems for government and reflective practice ( Argyris and Schon 1974 ; Schon 1971 ).

There can be little argument that the notion of collaborative governance is attracting considerable attention as a new paradigm in public administration. It is the subject of a growing number of books, articles, and monographs. It is seen by many as the new way of doing the business of government. Despite the popularity of the term in research, and claims of its wide-spread use in practice, the study of collaborative governance continues to suffer from a lack of conceptual clarity and consistency. In this article, we have sought to address this by developing an integrative framework that we hope will engender improvements in the theory, research, evaluation, and practice of collaborative governance.

Morris K. and Stewart L. Udall Foundation; Syracuse University; the State University of New York—College of Environmental Science and Forestry.

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude for the detailed comments and suggestions received from the anonymous reviewers. The quality of their reviews was remarkable and significantly improved the quality of this work. Special thanks to Olivier Barreteau, Charles Curtin, Neda Farahbakhshazad, Peter Murchie, and Marilyn Tenbrink for their formative comments on the framework and to Christine Carlson, Andrea Gerlak, and Rosemary O'Leary for their initial review of this article. We are also indebted to those who provided feedback on earlier presentations of the framework at the Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy at The University of Arizona and at the Collaborative Governance and Climate Change Conference in June 2009 sponsored by the Association for Conflict Resolution's Environment and Public Policy Section.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

For example, Selin and Chavez (1995) focus on environmental planning and management generally, whereas Bentrup (2001) focuses specifically on watershed planning. Koppenjan and Klijn (2004) study problem solving and decision making in networks, whereas Ring and Van de Ven (1994) examine business transactions. Moreover, the frameworks vary by the nature of the conceptual problem addressed. For example, Thomson and Perry (2006) focus on the processes of interorganizational partnerships, whereas Cooper, Bryer and Meek (2006) examine dynamics of engaging stakeholders and the public in community planning.

For example, the conflict resolution research often focuses on short time frames for reaching explicit agreements, thus missing the longer term implementation challenges or institutional dimensions ( Emerson et al. 2009 ). The intergovernmental and network management analyses tend to be focused on delivery of public services, often at local scales ( Agranoff and McGuire 2001 ; Milward and Provan 2000). As noted above, Ansell and Gash (2007) emphasize government-initiated processes with nongovernmental stakeholders.

This discussion is based on Ostrom's (2005) distinctions among frameworks, theories, and models. Frameworks specify general sets of variables (and the relationships among the variables) that are of interest to a researcher. Theories are more specific and provide an interpretive structure for frameworks. Theories enable the researcher to make working assumptions about how the variables in a framework interact, for example, to explain why events occur or to make predictions about relationships or phenomena. Finally, models are even more specific than theories and allow researchers to make precise assumptions about a limited set of variables, for example, to test hypotheses and predict outcomes.

For example, in the absence of federal action on climate change issues, state and local governments began developing their own climate change policies. In 2003, then New York Governor George Pataki invited fellow governors in the Northeast to explore the possibility of a regional climate change strategy. The result was the development of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). In this case, the system context in which collaboration unfolded was shaped by local, state, national, and international politics, the lack of federal law and action, environmental concerns, and other issues. In turn, RGGI changed the landscape of the system context by altering political, legal, regulatory, socioeconomic, environmental, and other forces in multiple northeastern states ( Rabe 2010 ).

We have elevated “principled engagement” to the framework level (as opposed to Ostrom's [2005] theory level) because it is a fundamental component within the definition of collaborative governance. Arguably, not all engagement will in fact be principled, that is, the de jure notion of principled engagement may not be what happens in de facto engagement. Nevertheless, the notion of principled engagement is consistent with the general definitions of collaborative governance, as well as our broader definition of collaborative governance. Moreover, the elements of principled engagement in this framework are articulated broadly enough to allow for different theories of engagement to be applied and different models to be tested.

It should be noted that increasing diversity in participation may have undesired consequences as well. In some situations, more diversity can generate higher levels of conflict and erode principled engagement, whereas in other situations, less diversity can lead to different, though not necessarily inferior actions and accomplishments ( Korfmacher 2000 ; Schlager and Blomquist 2008 ; Steelman and Carmin 2002 ).

Changing conditions in the system context and the collaboration itself also occur for reasons other than in response to the impacts of CGRs. This framework is focused, however, on the resulting from regime impacts.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| November 2016 | 1 |

| December 2016 | 7 |

| January 2017 | 189 |

| February 2017 | 668 |

| March 2017 | 521 |

| April 2017 | 330 |

| May 2017 | 450 |

| June 2017 | 325 |

| July 2017 | 231 |

| August 2017 | 297 |

| September 2017 | 327 |

| October 2017 | 315 |

| November 2017 | 345 |

| December 2017 | 866 |

| January 2018 | 1,006 |

| February 2018 | 1,237 |

| March 2018 | 2,365 |

| April 2018 | 2,437 |

| May 2018 | 1,960 |

| June 2018 | 1,815 |

| July 2018 | 1,410 |

| August 2018 | 1,568 |

| September 2018 | 1,527 |

| October 2018 | 1,528 |

| November 2018 | 1,692 |

| December 2018 | 1,496 |

| January 2019 | 1,258 |

| February 2019 | 1,623 |

| March 2019 | 1,733 |

| April 2019 | 1,833 |

| May 2019 | 1,793 |

| June 2019 | 1,524 |

| July 2019 | 1,522 |

| August 2019 | 1,818 |

| September 2019 | 1,845 |

| October 2019 | 1,903 |

| November 2019 | 1,697 |

| December 2019 | 1,223 |

| January 2020 | 1,185 |

| February 2020 | 1,440 |

| March 2020 | 1,280 |

| April 2020 | 1,714 |

| May 2020 | 972 |

| June 2020 | 1,391 |

| July 2020 | 1,206 |

| August 2020 | 1,287 |

| September 2020 | 1,560 |

| October 2020 | 1,734 |

| November 2020 | 1,545 |

| December 2020 | 1,978 |

| January 2021 | 1,420 |

| February 2021 | 1,745 |

| March 2021 | 2,158 |

| April 2021 | 1,910 |

| May 2021 | 1,663 |

| June 2021 | 1,503 |

| July 2021 | 1,287 |

| August 2021 | 1,332 |

| September 2021 | 1,531 |

| October 2021 | 1,851 |

| November 2021 | 2,046 |

| December 2021 | 1,623 |

| January 2022 | 1,401 |

| February 2022 | 1,648 |

| March 2022 | 2,162 |

| April 2022 | 1,967 |

| May 2022 | 1,767 |

| June 2022 | 1,435 |

| July 2022 | 1,246 |

| August 2022 | 1,417 |

| September 2022 | 1,656 |

| October 2022 | 2,054 |

| November 2022 | 1,675 |

| December 2022 | 1,545 |

| January 2023 | 1,608 |

| February 2023 | 1,910 |

| March 2023 | 2,347 |

| April 2023 | 2,321 |

| May 2023 | 2,088 |

| June 2023 | 1,853 |

| July 2023 | 1,590 |

| August 2023 | 1,687 |

| September 2023 | 2,064 |

| October 2023 | 2,551 |

| November 2023 | 2,269 |

| December 2023 | 2,030 |

| January 2024 | 2,591 |

| February 2024 | 2,393 |

| March 2024 | 3,550 |

| April 2024 | 3,015 |

| May 2024 | 2,813 |

| June 2024 | 2,323 |

| July 2024 | 1,852 |

| August 2024 | 1,407 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1477-9803

- Print ISSN 1053-1858

- Copyright © 2024 Public Management Research Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Advertisement

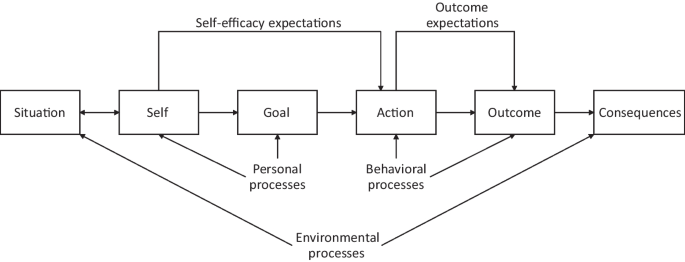

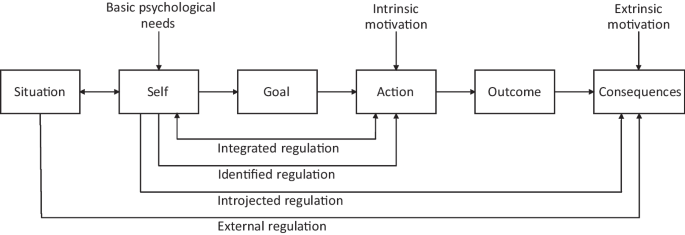

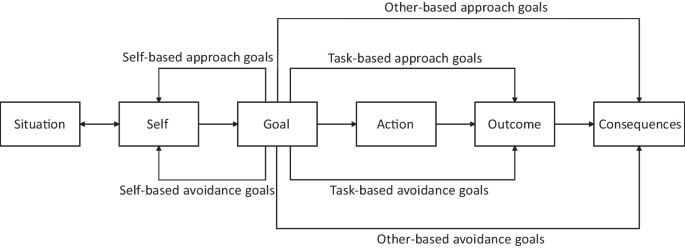

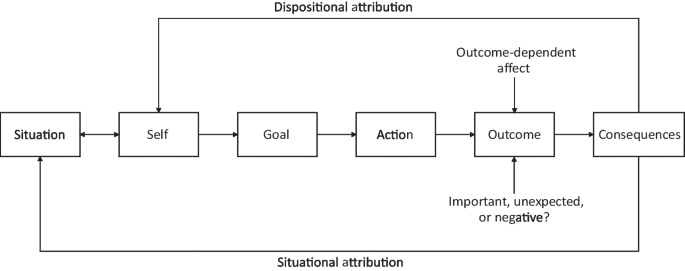

Theories of Motivation in Education: an Integrative Framework

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 30 March 2023

- Volume 35 , article number 45 , ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Detlef Urhahne ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7709-0011 1 &

- Lisette Wijnia ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7395-839X 2

112k Accesses

20 Citations

22 Altmetric

Explore all metrics