Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.1 Overview of Single-Subject Research

Learning objectives.

- Explain what single-subject research is, including how it differs from other types of psychological research.

- Explain what case studies are, including some of their strengths and weaknesses.

- Explain who uses single-subject research and why.

What Is Single-Subject Research?

Single-subject research is a type of quantitative research that involves studying in detail the behavior of each of a small number of participants. Note that the term single-subject does not mean that only one participant is studied; it is more typical for there to be somewhere between two and 10 participants. (This is why single-subject research designs are sometimes called small- n designs, where n is the statistical symbol for the sample size.) Single-subject research can be contrasted with group research , which typically involves studying large numbers of participants and examining their behavior primarily in terms of group means, standard deviations, and so on. The majority of this book is devoted to understanding group research, which is the most common approach in psychology. But single-subject research is an important alternative, and it is the primary approach in some areas of psychology.

Before continuing, it is important to distinguish single-subject research from two other approaches, both of which involve studying in detail a small number of participants. One is qualitative research, which focuses on understanding people’s subjective experience by collecting relatively unstructured data (e.g., detailed interviews) and analyzing those data using narrative rather than quantitative techniques. Single-subject research, in contrast, focuses on understanding objective behavior through experimental manipulation and control, collecting highly structured data, and analyzing those data quantitatively.

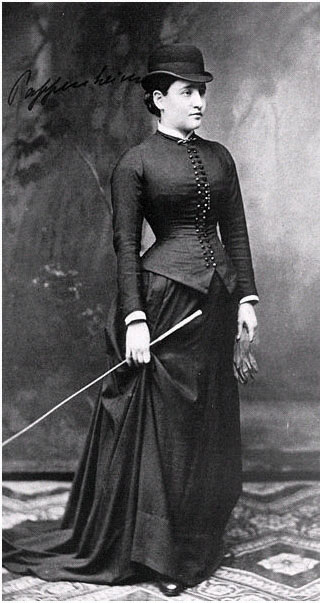

It is also important to distinguish single-subject research from case studies. A case study is a detailed description of an individual, which can include both qualitative and quantitative analyses. (Case studies that include only qualitative analyses can be considered a type of qualitative research.) The history of psychology is filled with influential cases studies, such as Sigmund Freud’s description of “Anna O.” (see Note 10.5 “The Case of “Anna O.”” ) and John Watson and Rosalie Rayner’s description of Little Albert (Watson & Rayner, 1920), who learned to fear a white rat—along with other furry objects—when the researchers made a loud noise while he was playing with the rat. Case studies can be useful for suggesting new research questions and for illustrating general principles. They can also help researchers understand rare phenomena, such as the effects of damage to a specific part of the human brain. As a general rule, however, case studies cannot substitute for carefully designed group or single-subject research studies. One reason is that case studies usually do not allow researchers to determine whether specific events are causally related, or even related at all. For example, if a patient is described in a case study as having been sexually abused as a child and then as having developed an eating disorder as a teenager, there is no way to determine whether these two events had anything to do with each other. A second reason is that an individual case can always be unusual in some way and therefore be unrepresentative of people more generally. Thus case studies have serious problems with both internal and external validity.

The Case of “Anna O.”

Sigmund Freud used the case of a young woman he called “Anna O.” to illustrate many principles of his theory of psychoanalysis (Freud, 1961). (Her real name was Bertha Pappenheim, and she was an early feminist who went on to make important contributions to the field of social work.) Anna had come to Freud’s colleague Josef Breuer around 1880 with a variety of odd physical and psychological symptoms. One of them was that for several weeks she was unable to drink any fluids. According to Freud,

She would take up the glass of water that she longed for, but as soon as it touched her lips she would push it away like someone suffering from hydrophobia.…She lived only on fruit, such as melons, etc., so as to lessen her tormenting thirst (p. 9).

But according to Freud, a breakthrough came one day while Anna was under hypnosis.

[S]he grumbled about her English “lady-companion,” whom she did not care for, and went on to describe, with every sign of disgust, how she had once gone into this lady’s room and how her little dog—horrid creature!—had drunk out of a glass there. The patient had said nothing, as she had wanted to be polite. After giving further energetic expression to the anger she had held back, she asked for something to drink, drank a large quantity of water without any difficulty, and awoke from her hypnosis with the glass at her lips; and thereupon the disturbance vanished, never to return.

Freud’s interpretation was that Anna had repressed the memory of this incident along with the emotion that it triggered and that this was what had caused her inability to drink. Furthermore, her recollection of the incident, along with her expression of the emotion she had repressed, caused the symptom to go away.

As an illustration of Freud’s theory, the case study of Anna O. is quite effective. As evidence for the theory, however, it is essentially worthless. The description provides no way of knowing whether Anna had really repressed the memory of the dog drinking from the glass, whether this repression had caused her inability to drink, or whether recalling this “trauma” relieved the symptom. It is also unclear from this case study how typical or atypical Anna’s experience was.

Figure 10.2

“Anna O.” was the subject of a famous case study used by Freud to illustrate the principles of psychoanalysis.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Assumptions of Single-Subject Research

Again, single-subject research involves studying a small number of participants and focusing intensively on the behavior of each one. But why take this approach instead of the group approach? There are several important assumptions underlying single-subject research, and it will help to consider them now.

First and foremost is the assumption that it is important to focus intensively on the behavior of individual participants. One reason for this is that group research can hide individual differences and generate results that do not represent the behavior of any individual. For example, a treatment that has a positive effect for half the people exposed to it but a negative effect for the other half would, on average, appear to have no effect at all. Single-subject research, however, would likely reveal these individual differences. A second reason to focus intensively on individuals is that sometimes it is the behavior of a particular individual that is primarily of interest. A school psychologist, for example, might be interested in changing the behavior of a particular disruptive student. Although previous published research (both single-subject and group research) is likely to provide some guidance on how to do this, conducting a study on this student would be more direct and probably more effective.

A second assumption of single-subject research is that it is important to discover causal relationships through the manipulation of an independent variable, the careful measurement of a dependent variable, and the control of extraneous variables. For this reason, single-subject research is often considered a type of experimental research with good internal validity. Recall, for example, that Hall and his colleagues measured their dependent variable (studying) many times—first under a no-treatment control condition, then under a treatment condition (positive teacher attention), and then again under the control condition. Because there was a clear increase in studying when the treatment was introduced, a decrease when it was removed, and an increase when it was reintroduced, there is little doubt that the treatment was the cause of the improvement.

A third assumption of single-subject research is that it is important to study strong and consistent effects that have biological or social importance. Applied researchers, in particular, are interested in treatments that have substantial effects on important behaviors and that can be implemented reliably in the real-world contexts in which they occur. This is sometimes referred to as social validity (Wolf, 1976). The study by Hall and his colleagues, for example, had good social validity because it showed strong and consistent effects of positive teacher attention on a behavior that is of obvious importance to teachers, parents, and students. Furthermore, the teachers found the treatment easy to implement, even in their often chaotic elementary school classrooms.

Who Uses Single-Subject Research?

Single-subject research has been around as long as the field of psychology itself. In the late 1800s, one of psychology’s founders, Wilhelm Wundt, studied sensation and consciousness by focusing intensively on each of a small number of research participants. Herman Ebbinghaus’s research on memory and Ivan Pavlov’s research on classical conditioning are other early examples, both of which are still described in almost every introductory psychology textbook.

In the middle of the 20th century, B. F. Skinner clarified many of the assumptions underlying single-subject research and refined many of its techniques (Skinner, 1938). He and other researchers then used it to describe how rewards, punishments, and other external factors affect behavior over time. This work was carried out primarily using nonhuman subjects—mostly rats and pigeons. This approach, which Skinner called the experimental analysis of behavior —remains an important subfield of psychology and continues to rely almost exclusively on single-subject research. For excellent examples of this work, look at any issue of the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior . By the 1960s, many researchers were interested in using this approach to conduct applied research primarily with humans—a subfield now called applied behavior analysis (Baer, Wolf, & Risley, 1968). Applied behavior analysis plays an especially important role in contemporary research on developmental disabilities, education, organizational behavior, and health, among many other areas. Excellent examples of this work (including the study by Hall and his colleagues) can be found in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis .

Although most contemporary single-subject research is conducted from the behavioral perspective, it can in principle be used to address questions framed in terms of any theoretical perspective. For example, a studying technique based on cognitive principles of learning and memory could be evaluated by testing it on individual high school students using the single-subject approach. The single-subject approach can also be used by clinicians who take any theoretical perspective—behavioral, cognitive, psychodynamic, or humanistic—to study processes of therapeutic change with individual clients and to document their clients’ improvement (Kazdin, 1982).

Key Takeaways

- Single-subject research—which involves testing a small number of participants and focusing intensively on the behavior of each individual—is an important alternative to group research in psychology.

- Single-subject studies must be distinguished from case studies, in which an individual case is described in detail. Case studies can be useful for generating new research questions, for studying rare phenomena, and for illustrating general principles. However, they cannot substitute for carefully controlled experimental or correlational studies because they are low in internal and external validity.

- Single-subject research has been around since the beginning of the field of psychology. Today it is most strongly associated with the behavioral theoretical perspective, but it can in principle be used to study behavior from any perspective.

- Practice: Find and read a published article in psychology that reports new single-subject research. (A good source of articles published in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis can be found at http://seab.envmed.rochester.edu/jaba/jabaMostPop-2011.html .) Write a short summary of the study.

Practice: Find and read a published case study in psychology. (Use case study as a key term in a PsycINFO search.) Then do the following:

- Describe one problem related to internal validity.

- Describe one problem related to external validity.

- Generate one hypothesis suggested by the case study that might be interesting to test in a systematic single-subject or group study.

Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis , 1 , 91–97.

Freud, S. (1961). Five lectures on psycho-analysis . New York, NY: Norton.

Kazdin, A. E. (1982). Single-case research designs: Methods for clinical and applied settings . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis . New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology , 3 , 1–14.

Wolf, M. (1976). Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11 , 203–214.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 30 January 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating, and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyse the case.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

Unlike quantitative or experimental research, a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

If you find yourself aiming to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue, consider conducting action research . As its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time, and is highly iterative and flexible.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data .

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis, with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results , and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyse its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, January 30). Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 31 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-studies/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, correlational research | guide, design & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples.

The Advantages and Limitations of Single Case Study Analysis

As Andrew Bennett and Colin Elman have recently noted, qualitative research methods presently enjoy “an almost unprecedented popularity and vitality… in the international relations sub-field”, such that they are now “indisputably prominent, if not pre-eminent” (2010: 499). This is, they suggest, due in no small part to the considerable advantages that case study methods in particular have to offer in studying the “complex and relatively unstructured and infrequent phenomena that lie at the heart of the subfield” (Bennett and Elman, 2007: 171). Using selected examples from within the International Relations literature[1], this paper aims to provide a brief overview of the main principles and distinctive advantages and limitations of single case study analysis. Divided into three inter-related sections, the paper therefore begins by first identifying the underlying principles that serve to constitute the case study as a particular research strategy, noting the somewhat contested nature of the approach in ontological, epistemological, and methodological terms. The second part then looks to the principal single case study types and their associated advantages, including those from within the recent ‘third generation’ of qualitative International Relations (IR) research. The final section of the paper then discusses the most commonly articulated limitations of single case studies; while accepting their susceptibility to criticism, it is however suggested that such weaknesses are somewhat exaggerated. The paper concludes that single case study analysis has a great deal to offer as a means of both understanding and explaining contemporary international relations.

The term ‘case study’, John Gerring has suggested, is “a definitional morass… Evidently, researchers have many different things in mind when they talk about case study research” (2006a: 17). It is possible, however, to distil some of the more commonly-agreed principles. One of the most prominent advocates of case study research, Robert Yin (2009: 14) defines it as “an empirical enquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident”. What this definition usefully captures is that case studies are intended – unlike more superficial and generalising methods – to provide a level of detail and understanding, similar to the ethnographer Clifford Geertz’s (1973) notion of ‘thick description’, that allows for the thorough analysis of the complex and particularistic nature of distinct phenomena. Another frequently cited proponent of the approach, Robert Stake, notes that as a form of research the case study “is defined by interest in an individual case, not by the methods of inquiry used”, and that “the object of study is a specific, unique, bounded system” (2008: 443, 445). As such, three key points can be derived from this – respectively concerning issues of ontology, epistemology, and methodology – that are central to the principles of single case study research.

First, the vital notion of ‘boundedness’ when it comes to the particular unit of analysis means that defining principles should incorporate both the synchronic (spatial) and diachronic (temporal) elements of any so-called ‘case’. As Gerring puts it, a case study should be “an intensive study of a single unit… a spatially bounded phenomenon – e.g. a nation-state, revolution, political party, election, or person – observed at a single point in time or over some delimited period of time” (2004: 342). It is important to note, however, that – whereas Gerring refers to a single unit of analysis – it may be that attention also necessarily be given to particular sub-units. This points to the important difference between what Yin refers to as an ‘holistic’ case design, with a single unit of analysis, and an ’embedded’ case design with multiple units of analysis (Yin, 2009: 50-52). The former, for example, would examine only the overall nature of an international organization, whereas the latter would also look to specific departments, programmes, or policies etc.

Secondly, as Tim May notes of the case study approach, “even the most fervent advocates acknowledge that the term has entered into understandings with little specification or discussion of purpose and process” (2011: 220). One of the principal reasons for this, he argues, is the relationship between the use of case studies in social research and the differing epistemological traditions – positivist, interpretivist, and others – within which it has been utilised. Philosophy of science concerns are obviously a complex issue, and beyond the scope of much of this paper. That said, the issue of how it is that we know what we know – of whether or not a single independent reality exists of which we as researchers can seek to provide explanation – does lead us to an important distinction to be made between so-called idiographic and nomothetic case studies (Gerring, 2006b). The former refers to those which purport to explain only a single case, are concerned with particularisation, and hence are typically (although not exclusively) associated with more interpretivist approaches. The latter are those focused studies that reflect upon a larger population and are more concerned with generalisation, as is often so with more positivist approaches[2]. The importance of this distinction, and its relation to the advantages and limitations of single case study analysis, is returned to below.

Thirdly, in methodological terms, given that the case study has often been seen as more of an interpretivist and idiographic tool, it has also been associated with a distinctly qualitative approach (Bryman, 2009: 67-68). However, as Yin notes, case studies can – like all forms of social science research – be exploratory, descriptive, and/or explanatory in nature. It is “a common misconception”, he notes, “that the various research methods should be arrayed hierarchically… many social scientists still deeply believe that case studies are only appropriate for the exploratory phase of an investigation” (Yin, 2009: 6). If case studies can reliably perform any or all three of these roles – and given that their in-depth approach may also require multiple sources of data and the within-case triangulation of methods – then it becomes readily apparent that they should not be limited to only one research paradigm. Exploratory and descriptive studies usually tend toward the qualitative and inductive, whereas explanatory studies are more often quantitative and deductive (David and Sutton, 2011: 165-166). As such, the association of case study analysis with a qualitative approach is a “methodological affinity, not a definitional requirement” (Gerring, 2006a: 36). It is perhaps better to think of case studies as transparadigmatic; it is mistaken to assume single case study analysis to adhere exclusively to a qualitative methodology (or an interpretivist epistemology) even if it – or rather, practitioners of it – may be so inclined. By extension, this also implies that single case study analysis therefore remains an option for a multitude of IR theories and issue areas; it is how this can be put to researchers’ advantage that is the subject of the next section.

Having elucidated the defining principles of the single case study approach, the paper now turns to an overview of its main benefits. As noted above, a lack of consensus still exists within the wider social science literature on the principles and purposes – and by extension the advantages and limitations – of case study research. Given that this paper is directed towards the particular sub-field of International Relations, it suggests Bennett and Elman’s (2010) more discipline-specific understanding of contemporary case study methods as an analytical framework. It begins however, by discussing Harry Eckstein’s seminal (1975) contribution to the potential advantages of the case study approach within the wider social sciences.

Eckstein proposed a taxonomy which usefully identified what he considered to be the five most relevant types of case study. Firstly were so-called configurative-idiographic studies, distinctly interpretivist in orientation and predicated on the assumption that “one cannot attain prediction and control in the natural science sense, but only understanding ( verstehen )… subjective values and modes of cognition are crucial” (1975: 132). Eckstein’s own sceptical view was that any interpreter ‘simply’ considers a body of observations that are not self-explanatory and “without hard rules of interpretation, may discern in them any number of patterns that are more or less equally plausible” (1975: 134). Those of a more post-modernist bent, of course – sharing an “incredulity towards meta-narratives”, in Lyotard’s (1994: xxiv) evocative phrase – would instead suggest that this more free-form approach actually be advantageous in delving into the subtleties and particularities of individual cases.

Eckstein’s four other types of case study, meanwhile, promote a more nomothetic (and positivist) usage. As described, disciplined-configurative studies were essentially about the use of pre-existing general theories, with a case acting “passively, in the main, as a receptacle for putting theories to work” (Eckstein, 1975: 136). As opposed to the opportunity this presented primarily for theory application, Eckstein identified heuristic case studies as explicit theoretical stimulants – thus having instead the intended advantage of theory-building. So-called p lausibility probes entailed preliminary attempts to determine whether initial hypotheses should be considered sound enough to warrant more rigorous and extensive testing. Finally, and perhaps most notably, Eckstein then outlined the idea of crucial case studies , within which he also included the idea of ‘most-likely’ and ‘least-likely’ cases; the essential characteristic of crucial cases being their specific theory-testing function.

Whilst Eckstein’s was an early contribution to refining the case study approach, Yin’s (2009: 47-52) more recent delineation of possible single case designs similarly assigns them roles in the applying, testing, or building of theory, as well as in the study of unique cases[3]. As a subset of the latter, however, Jack Levy (2008) notes that the advantages of idiographic cases are actually twofold. Firstly, as inductive/descriptive cases – akin to Eckstein’s configurative-idiographic cases – whereby they are highly descriptive, lacking in an explicit theoretical framework and therefore taking the form of “total history”. Secondly, they can operate as theory-guided case studies, but ones that seek only to explain or interpret a single historical episode rather than generalise beyond the case. Not only does this therefore incorporate ‘single-outcome’ studies concerned with establishing causal inference (Gerring, 2006b), it also provides room for the more postmodern approaches within IR theory, such as discourse analysis, that may have developed a distinct methodology but do not seek traditional social scientific forms of explanation.

Applying specifically to the state of the field in contemporary IR, Bennett and Elman identify a ‘third generation’ of mainstream qualitative scholars – rooted in a pragmatic scientific realist epistemology and advocating a pluralistic approach to methodology – that have, over the last fifteen years, “revised or added to essentially every aspect of traditional case study research methods” (2010: 502). They identify ‘process tracing’ as having emerged from this as a central method of within-case analysis. As Bennett and Checkel observe, this carries the advantage of offering a methodologically rigorous “analysis of evidence on processes, sequences, and conjunctures of events within a case, for the purposes of either developing or testing hypotheses about causal mechanisms that might causally explain the case” (2012: 10).

Harnessing various methods, process tracing may entail the inductive use of evidence from within a case to develop explanatory hypotheses, and deductive examination of the observable implications of hypothesised causal mechanisms to test their explanatory capability[4]. It involves providing not only a coherent explanation of the key sequential steps in a hypothesised process, but also sensitivity to alternative explanations as well as potential biases in the available evidence (Bennett and Elman 2010: 503-504). John Owen (1994), for example, demonstrates the advantages of process tracing in analysing whether the causal factors underpinning democratic peace theory are – as liberalism suggests – not epiphenomenal, but variously normative, institutional, or some given combination of the two or other unexplained mechanism inherent to liberal states. Within-case process tracing has also been identified as advantageous in addressing the complexity of path-dependent explanations and critical junctures – as for example with the development of political regime types – and their constituent elements of causal possibility, contingency, closure, and constraint (Bennett and Elman, 2006b).

Bennett and Elman (2010: 505-506) also identify the advantages of single case studies that are implicitly comparative: deviant, most-likely, least-likely, and crucial cases. Of these, so-called deviant cases are those whose outcome does not fit with prior theoretical expectations or wider empirical patterns – again, the use of inductive process tracing has the advantage of potentially generating new hypotheses from these, either particular to that individual case or potentially generalisable to a broader population. A classic example here is that of post-independence India as an outlier to the standard modernisation theory of democratisation, which holds that higher levels of socio-economic development are typically required for the transition to, and consolidation of, democratic rule (Lipset, 1959; Diamond, 1992). Absent these factors, MacMillan’s single case study analysis (2008) suggests the particularistic importance of the British colonial heritage, the ideology and leadership of the Indian National Congress, and the size and heterogeneity of the federal state.

Most-likely cases, as per Eckstein above, are those in which a theory is to be considered likely to provide a good explanation if it is to have any application at all, whereas least-likely cases are ‘tough test’ ones in which the posited theory is unlikely to provide good explanation (Bennett and Elman, 2010: 505). Levy (2008) neatly refers to the inferential logic of the least-likely case as the ‘Sinatra inference’ – if a theory can make it here, it can make it anywhere. Conversely, if a theory cannot pass a most-likely case, it is seriously impugned. Single case analysis can therefore be valuable for the testing of theoretical propositions, provided that predictions are relatively precise and measurement error is low (Levy, 2008: 12-13). As Gerring rightly observes of this potential for falsification:

“a positivist orientation toward the work of social science militates toward a greater appreciation of the case study format, not a denigration of that format, as is usually supposed” (Gerring, 2007: 247, emphasis added).

In summary, the various forms of single case study analysis can – through the application of multiple qualitative and/or quantitative research methods – provide a nuanced, empirically-rich, holistic account of specific phenomena. This may be particularly appropriate for those phenomena that are simply less amenable to more superficial measures and tests (or indeed any substantive form of quantification) as well as those for which our reasons for understanding and/or explaining them are irreducibly subjective – as, for example, with many of the normative and ethical issues associated with the practice of international relations. From various epistemological and analytical standpoints, single case study analysis can incorporate both idiographic sui generis cases and, where the potential for generalisation may exist, nomothetic case studies suitable for the testing and building of causal hypotheses. Finally, it should not be ignored that a signal advantage of the case study – with particular relevance to international relations – also exists at a more practical rather than theoretical level. This is, as Eckstein noted, “that it is economical for all resources: money, manpower, time, effort… especially important, of course, if studies are inherently costly, as they are if units are complex collective individuals ” (1975: 149-150, emphasis added).

Limitations

Single case study analysis has, however, been subject to a number of criticisms, the most common of which concern the inter-related issues of methodological rigour, researcher subjectivity, and external validity. With regard to the first point, the prototypical view here is that of Zeev Maoz (2002: 164-165), who suggests that “the use of the case study absolves the author from any kind of methodological considerations. Case studies have become in many cases a synonym for freeform research where anything goes”. The absence of systematic procedures for case study research is something that Yin (2009: 14-15) sees as traditionally the greatest concern due to a relative absence of methodological guidelines. As the previous section suggests, this critique seems somewhat unfair; many contemporary case study practitioners – and representing various strands of IR theory – have increasingly sought to clarify and develop their methodological techniques and epistemological grounding (Bennett and Elman, 2010: 499-500).

A second issue, again also incorporating issues of construct validity, concerns that of the reliability and replicability of various forms of single case study analysis. This is usually tied to a broader critique of qualitative research methods as a whole. However, whereas the latter obviously tend toward an explicitly-acknowledged interpretive basis for meanings, reasons, and understandings:

“quantitative measures appear objective, but only so long as we don’t ask questions about where and how the data were produced… pure objectivity is not a meaningful concept if the goal is to measure intangibles [as] these concepts only exist because we can interpret them” (Berg and Lune, 2010: 340).

The question of researcher subjectivity is a valid one, and it may be intended only as a methodological critique of what are obviously less formalised and researcher-independent methods (Verschuren, 2003). Owen (1994) and Layne’s (1994) contradictory process tracing results of interdemocratic war-avoidance during the Anglo-American crisis of 1861 to 1863 – from liberal and realist standpoints respectively – are a useful example. However, it does also rest on certain assumptions that can raise deeper and potentially irreconcilable ontological and epistemological issues. There are, regardless, plenty such as Bent Flyvbjerg (2006: 237) who suggest that the case study contains no greater bias toward verification than other methods of inquiry, and that “on the contrary, experience indicates that the case study contains a greater bias toward falsification of preconceived notions than toward verification”.

The third and arguably most prominent critique of single case study analysis is the issue of external validity or generalisability. How is it that one case can reliably offer anything beyond the particular? “We always do better (or, in the extreme, no worse) with more observation as the basis of our generalization”, as King et al write; “in all social science research and all prediction, it is important that we be as explicit as possible about the degree of uncertainty that accompanies out prediction” (1994: 212). This is an unavoidably valid criticism. It may be that theories which pass a single crucial case study test, for example, require rare antecedent conditions and therefore actually have little explanatory range. These conditions may emerge more clearly, as Van Evera (1997: 51-54) notes, from large-N studies in which cases that lack them present themselves as outliers exhibiting a theory’s cause but without its predicted outcome. As with the case of Indian democratisation above, it would logically be preferable to conduct large-N analysis beforehand to identify that state’s non-representative nature in relation to the broader population.

There are, however, three important qualifiers to the argument about generalisation that deserve particular mention here. The first is that with regard to an idiographic single-outcome case study, as Eckstein notes, the criticism is “mitigated by the fact that its capability to do so [is] never claimed by its exponents; in fact it is often explicitly repudiated” (1975: 134). Criticism of generalisability is of little relevance when the intention is one of particularisation. A second qualifier relates to the difference between statistical and analytical generalisation; single case studies are clearly less appropriate for the former but arguably retain significant utility for the latter – the difference also between explanatory and exploratory, or theory-testing and theory-building, as discussed above. As Gerring puts it, “theory confirmation/disconfirmation is not the case study’s strong suit” (2004: 350). A third qualification relates to the issue of case selection. As Seawright and Gerring (2008) note, the generalisability of case studies can be increased by the strategic selection of cases. Representative or random samples may not be the most appropriate, given that they may not provide the richest insight (or indeed, that a random and unknown deviant case may appear). Instead, and properly used , atypical or extreme cases “often reveal more information because they activate more actors… and more basic mechanisms in the situation studied” (Flyvbjerg, 2006). Of course, this also points to the very serious limitation, as hinted at with the case of India above, that poor case selection may alternatively lead to overgeneralisation and/or grievous misunderstandings of the relationship between variables or processes (Bennett and Elman, 2006a: 460-463).

As Tim May (2011: 226) notes, “the goal for many proponents of case studies […] is to overcome dichotomies between generalizing and particularizing, quantitative and qualitative, deductive and inductive techniques”. Research aims should drive methodological choices, rather than narrow and dogmatic preconceived approaches. As demonstrated above, there are various advantages to both idiographic and nomothetic single case study analyses – notably the empirically-rich, context-specific, holistic accounts that they have to offer, and their contribution to theory-building and, to a lesser extent, that of theory-testing. Furthermore, while they do possess clear limitations, any research method involves necessary trade-offs; the inherent weaknesses of any one method, however, can potentially be offset by situating them within a broader, pluralistic mixed-method research strategy. Whether or not single case studies are used in this fashion, they clearly have a great deal to offer.

References

Bennett, A. and Checkel, J. T. (2012) ‘Process Tracing: From Philosophical Roots to Best Practice’, Simons Papers in Security and Development, No. 21/2012, School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University: Vancouver.

Bennett, A. and Elman, C. (2006a) ‘Qualitative Research: Recent Developments in Case Study Methods’, Annual Review of Political Science , 9, 455-476.

Bennett, A. and Elman, C. (2006b) ‘Complex Causal Relations and Case Study Methods: The Example of Path Dependence’, Political Analysis , 14, 3, 250-267.

Bennett, A. and Elman, C. (2007) ‘Case Study Methods in the International Relations Subfield’, Comparative Political Studies , 40, 2, 170-195.

Bennett, A. and Elman, C. (2010) Case Study Methods. In C. Reus-Smit and D. Snidal (eds) The Oxford Handbook of International Relations . Oxford University Press: Oxford. Ch. 29.

Berg, B. and Lune, H. (2012) Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences . Pearson: London.

Bryman, A. (2012) Social Research Methods . Oxford University Press: Oxford.

David, M. and Sutton, C. D. (2011) Social Research: An Introduction . SAGE Publications Ltd: London.

Diamond, J. (1992) ‘Economic development and democracy reconsidered’, American Behavioral Scientist , 35, 4/5, 450-499.

Eckstein, H. (1975) Case Study and Theory in Political Science. In R. Gomm, M. Hammersley, and P. Foster (eds) Case Study Method . SAGE Publications Ltd: London.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006) ‘Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research’, Qualitative Inquiry , 12, 2, 219-245.

Geertz, C. (1973) The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays by Clifford Geertz . Basic Books Inc: New York.

Gerring, J. (2004) ‘What is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?’, American Political Science Review , 98, 2, 341-354.

Gerring, J. (2006a) Case Study Research: Principles and Practices . Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Gerring, J. (2006b) ‘Single-Outcome Studies: A Methodological Primer’, International Sociology , 21, 5, 707-734.

Gerring, J. (2007) ‘Is There a (Viable) Crucial-Case Method?’, Comparative Political Studies , 40, 3, 231-253.

King, G., Keohane, R. O. and Verba, S. (1994) Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research . Princeton University Press: Chichester.

Layne, C. (1994) ‘Kant or Cant: The Myth of the Democratic Peace’, International Security , 19, 2, 5-49.

Levy, J. S. (2008) ‘Case Studies: Types, Designs, and Logics of Inference’, Conflict Management and Peace Science , 25, 1-18.

Lipset, S. M. (1959) ‘Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy’, The American Political Science Review , 53, 1, 69-105.

Lyotard, J-F. (1984) The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge . University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis.

MacMillan, A. (2008) ‘Deviant Democratization in India’, Democratization , 15, 4, 733-749.

Maoz, Z. (2002) Case study methodology in international studies: from storytelling to hypothesis testing. In F. P. Harvey and M. Brecher (eds) Evaluating Methodology in International Studies . University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor.

May, T. (2011) Social Research: Issues, Methods and Process . Open University Press: Maidenhead.

Owen, J. M. (1994) ‘How Liberalism Produces Democratic Peace’, International Security , 19, 2, 87-125.

Seawright, J. and Gerring, J. (2008) ‘Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options’, Political Research Quarterly , 61, 2, 294-308.

Stake, R. E. (2008) Qualitative Case Studies. In N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (eds) Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry . Sage Publications: Los Angeles. Ch. 17.

Van Evera, S. (1997) Guide to Methods for Students of Political Science . Cornell University Press: Ithaca.

Verschuren, P. J. M. (2003) ‘Case study as a research strategy: some ambiguities and opportunities’, International Journal of Social Research Methodology , 6, 2, 121-139.

Yin, R. K. (2009) Case Study Research: Design and Methods . SAGE Publications Ltd: London.

[1] The paper follows convention by differentiating between ‘International Relations’ as the academic discipline and ‘international relations’ as the subject of study.

[2] There is some similarity here with Stake’s (2008: 445-447) notion of intrinsic cases, those undertaken for a better understanding of the particular case, and instrumental ones that provide insight for the purposes of a wider external interest.

[3] These may be unique in the idiographic sense, or in nomothetic terms as an exception to the generalising suppositions of either probabilistic or deterministic theories (as per deviant cases, below).

[4] Although there are “philosophical hurdles to mount”, according to Bennett and Checkel, there exists no a priori reason as to why process tracing (as typically grounded in scientific realism) is fundamentally incompatible with various strands of positivism or interpretivism (2012: 18-19). By extension, it can therefore be incorporated by a range of contemporary mainstream IR theories.

— Written by: Ben Willis Written at: University of Plymouth Written for: David Brockington Date written: January 2013

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Identity in International Conflicts: A Case Study of the Cuban Missile Crisis

- Imperialism’s Legacy in the Study of Contemporary Politics: The Case of Hegemonic Stability Theory

- Recreating a Nation’s Identity Through Symbolism: A Chinese Case Study

- Ontological Insecurity: A Case Study on Israeli-Palestinian Conflict in Jerusalem

- Terrorists or Freedom Fighters: A Case Study of ETA

- A Critical Assessment of Eco-Marxism: A Ghanaian Case Study

Please Consider Donating

Before you download your free e-book, please consider donating to support open access publishing.

E-IR is an independent non-profit publisher run by an all volunteer team. Your donations allow us to invest in new open access titles and pay our bandwidth bills to ensure we keep our existing titles free to view. Any amount, in any currency, is appreciated. Many thanks!

Donations are voluntary and not required to download the e-book - your link to download is below.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Med Libr Assoc

- v.107(1); 2019 Jan

Distinguishing case study as a research method from case reports as a publication type

The purpose of this editorial is to distinguish between case reports and case studies. In health, case reports are familiar ways of sharing events or efforts of intervening with single patients with previously unreported features. As a qualitative methodology, case study research encompasses a great deal more complexity than a typical case report and often incorporates multiple streams of data combined in creative ways. The depth and richness of case study description helps readers understand the case and whether findings might be applicable beyond that setting.

Single-institution descriptive reports of library activities are often labeled by their authors as “case studies.” By contrast, in health care, single patient retrospective descriptions are published as “case reports.” Both case reports and case studies are valuable to readers and provide a publication opportunity for authors. A previous editorial by Akers and Amos about improving case studies addresses issues that are more common to case reports; for example, not having a review of the literature or being anecdotal, not generalizable, and prone to various types of bias such as positive outcome bias [ 1 ]. However, case study research as a qualitative methodology is pursued for different purposes than generalizability. The authors’ purpose in this editorial is to clearly distinguish between case reports and case studies. We believe that this will assist authors in describing and designating the methodological approach of their publications and help readers appreciate the rigor of well-executed case study research.

Case reports often provide a first exploration of a phenomenon or an opportunity for a first publication by a trainee in the health professions. In health care, case reports are familiar ways of sharing events or efforts of intervening with single patients with previously unreported features. Another type of study categorized as a case report is an “N of 1” study or single-subject clinical trial, which considers an individual patient as the sole unit of observation in a study investigating the efficacy or side effect profiles of different interventions. Entire journals have evolved to publish case reports, which often rely on template structures with limited contextualization or discussion of previous cases. Examples that are indexed in MEDLINE include the American Journal of Case Reports , BMJ Case Reports, Journal of Medical Case Reports, and Journal of Radiology Case Reports . Similar publications appear in veterinary medicine and are indexed in CAB Abstracts, such as Case Reports in Veterinary Medicine and Veterinary Record Case Reports .

As a qualitative methodology, however, case study research encompasses a great deal more complexity than a typical case report and often incorporates multiple streams of data combined in creative ways. Distinctions include the investigator’s definitions and delimitations of the case being studied, the clarity of the role of the investigator, the rigor of gathering and combining evidence about the case, and the contextualization of the findings. Delimitation is a term from qualitative research about setting boundaries to scope the research in a useful way rather than describing the narrow scope as a limitation, as often appears in a discussion section. The depth and richness of description helps readers understand the situation and whether findings from the case are applicable to their settings.

CASE STUDY AS A RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Case study as a qualitative methodology is an exploration of a time- and space-bound phenomenon. As qualitative research, case studies require much more from their authors who are acting as instruments within the inquiry process. In the case study methodology, a variety of methodological approaches may be employed to explain the complexity of the problem being studied [ 2 , 3 ].

Leading authors diverge in their definitions of case study, but a qualitative research text introduces case study as follows:

Case study research is defined as a qualitative approach in which the investigator explores a real-life, contemporary bounded system (a case) or multiple bound systems (cases) over time, through detailed, in-depth data collection involving multiple sources of information, and reports a case description and case themes. The unit of analysis in the case study might be multiple cases (a multisite study) or a single case (a within-site case study). [ 4 ]

Methodologists writing core texts on case study research include Yin [ 5 ], Stake [ 6 ], and Merriam [ 7 ]. The approaches of these three methodologists have been compared by Yazan, who focused on six areas of methodology: epistemology (beliefs about ways of knowing), definition of cases, design of case studies, and gathering, analysis, and validation of data [ 8 ]. For Yin, case study is a method of empirical inquiry appropriate to determining the “how and why” of phenomena and contributes to understanding phenomena in a holistic and real-life context [ 5 ]. Stake defines a case study as a “well-bounded, specific, complex, and functioning thing” [ 6 ], while Merriam views “the case as a thing, a single entity, a unit around which there are boundaries” [ 7 ].

Case studies are ways to explain, describe, or explore phenomena. Comments from a quantitative perspective about case studies lacking rigor and generalizability fail to consider the purpose of the case study and how what is learned from a case study is put into practice. Rigor in case studies comes from the research design and its components, which Yin outlines as (a) the study’s questions, (b) the study’s propositions, (c) the unit of analysis, (d) the logic linking the data to propositions, and (e) the criteria for interpreting the findings [ 5 ]. Case studies should also provide multiple sources of data, a case study database, and a clear chain of evidence among the questions asked, the data collected, and the conclusions drawn [ 5 ].

Sources of evidence for case studies include interviews, documentation, archival records, direct observations, participant-observation, and physical artifacts. One of the most important sources for data in qualitative case study research is the interview [ 2 , 3 ]. In addition to interviews, documents and archival records can be gathered to corroborate and enhance the findings of the study. To understand the phenomenon or the conditions that created it, direct observations can serve as another source of evidence and can be conducted throughout the study. These can include the use of formal and informal protocols as a participant inside the case or an external or passive observer outside of the case [ 5 ]. Lastly, physical artifacts can be observed and collected as a form of evidence. With these multiple potential sources of evidence, the study methodology includes gathering data, sense-making, and triangulating multiple streams of data. Figure 1 shows an example in which data used for the case started with a pilot study to provide additional context to guide more in-depth data collection and analysis with participants.

Key sources of data for a sample case study

VARIATIONS ON CASE STUDY METHODOLOGY

Case study methodology is evolving and regularly reinterpreted. Comparative or multiple case studies are used as a tool for synthesizing information across time and space to research the impact of policy and practice in various fields of social research [ 9 ]. Because case study research is in-depth and intensive, there have been efforts to simplify the method or select useful components of cases for focused analysis. Micro-case study is a term that is occasionally used to describe research on micro-level cases [ 10 ]. These are cases that occur in a brief time frame, occur in a confined setting, and are simple and straightforward in nature. A micro-level case describes a clear problem of interest. Reporting is very brief and about specific points. The lack of complexity in the case description makes obvious the “lesson” that is inherent in the case; although no definitive “solution” is necessarily forthcoming, making the case useful for discussion. A micro-case write-up can be distinguished from a case report by its focus on briefly reporting specific features of a case or cases to analyze or learn from those features.

DATABASE INDEXING OF CASE REPORTS AND CASE STUDIES

Disciplines such as education, psychology, sociology, political science, and social work regularly publish rich case studies that are relevant to particular areas of health librarianship. Case reports and case studies have been defined as publication types or subject terms by several databases that are relevant to librarian authors: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and ERIC. Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts (LISTA) does not have a subject term or publication type related to cases, despite many being included in the database. Whereas “Case Reports” are the main term used by MEDLINE’s Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and PsycINFO’s thesaurus, CINAHL and ERIC use “Case Studies.”

Case reports in MEDLINE and PsycINFO focus on clinical case documentation. In MeSH, “Case Reports” as a publication type is specific to “clinical presentations that may be followed by evaluative studies that eventually lead to a diagnosis” [ 11 ]. “Case Histories,” “Case Studies,” and “Case Study” are all entry terms mapping to “Case Reports”; however, guidance to indexers suggests that “Case Reports” should not be applied to institutional case reports and refers to the heading “Organizational Case Studies,” which is defined as “descriptions and evaluations of specific health care organizations” [ 12 ].

PsycINFO’s subject term “Case Report” is “used in records discussing issues involved in the process of conducting exploratory studies of single or multiple clinical cases.” The Methodology index offers clinical and non-clinical entries. “Clinical Case Study” is defined as “case reports that include disorder, diagnosis, and clinical treatment for individuals with mental or medical illnesses,” whereas “Non-clinical Case Study” is a “document consisting of non-clinical or organizational case examples of the concepts being researched or studied. The setting is always non-clinical and does not include treatment-related environments” [ 13 ].

Both CINAHL and ERIC acknowledge the depth of analysis in case study methodology. The CINAHL scope note for the thesaurus term “Case Studies” distinguishes between the document and the methodology, though both use the same term: “a review of a particular condition, disease, or administrative problem. Also, a research method that involves an in-depth analysis of an individual, group, institution, or other social unit. For material that contains a case study, search for document type: case study.” The ERIC scope note for the thesaurus term “Case Studies” is simple: “detailed analyses, usually focusing on a particular problem of an individual, group, or organization” [ 14 ].

PUBLICATION OF CASE STUDY RESEARCH IN LIBRARIANSHIP

We call your attention to a few examples published as case studies in health sciences librarianship to consider how their characteristics fit with the preceding definitions of case reports or case study research. All present some characteristics of case study research, but their treatment of the research questions, richness of description, and analytic strategies vary in depth and, therefore, diverge at some level from the qualitative case study research approach. This divergence, particularly in richness of description and analysis, may have been constrained by the publication requirements.

As one example, a case study by Janke and Rush documented a time- and context-bound collaboration involving a librarian and a nursing faculty member [ 15 ]. Three objectives were stated: (1) describing their experience of working together on an interprofessional research team, (2) evaluating the value of the librarian role from librarian and faculty member perspectives, and (3) relating findings to existing literature. Elements that signal the qualitative nature of this case study are that the authors were the research participants and their use of the term “evaluation” is reflection on their experience. This reads like a case study that could have been enriched by including other types of data gathered from others engaging with this team to broaden the understanding of the collaboration.

As another example, the description of the academic context is one of the most salient components of the case study written by Clairoux et al., which had the objectives of (1) describing the library instruction offered and learning assessments used at a single health sciences library and (2) discussing the positive outcomes of instruction in that setting [ 16 ]. The authors focus on sharing what the institution has done more than explaining why this institution is an exemplar to explore a focused question or understand the phenomenon of library instruction. However, like a case study, the analysis brings together several streams of data including course attendance, online material page views, and some discussion of results from surveys. This paper reads somewhat in between an institutional case report and a case study.

The final example is a single author reporting on a personal experience of creating and executing the role of research informationist for a National Institutes of Health (NIH)–funded research team [ 17 ]. There is a thoughtful review of the informationist literature and detailed descriptions of the institutional context and the process of gaining access to and participating in the new role. However, the motivating question in the abstract does not seem to be fully addressed through analysis from either the reflective perspective of the author as the research participant or consideration of other streams of data from those involved in the informationist experience. The publication reads more like a case report about this informationist’s experience than a case study that explores the research informationist experience through the selection of this case.

All of these publications are well written and useful for their intended audiences, but in general, they are much shorter and much less rich in depth than case studies published in social sciences research. It may be that the authors have been constrained by word counts or page limits. For example, the submission category for Case Studies in the Journal of the Medical Library Association (JMLA) limited them to 3,000 words and defined them as “articles describing the process of developing, implementing, and evaluating a new service, program, or initiative, typically in a single institution or through a single collaborative effort” [ 18 ]. This definition’s focus on novelty and description sounds much more like the definition of case report than the in-depth, detailed investigation of a time- and space-bound problem that is often examined through case study research.

Problem-focused or question-driven case study research would benefit from the space provided for Original Investigations that employ any type of quantitative or qualitative method of analysis. One of the best examples in the JMLA of an in-depth multiple case study that was authored by a librarian who published the findings from her doctoral dissertation represented all the elements of a case study. In eight pages, she provided a theoretical basis for the research question, a pilot study, and a multiple case design, including integrated data from interviews and focus groups [ 19 ].

We have distinguished between case reports and case studies primarily to assist librarians who are new to research and critical appraisal of case study methodology to recognize the features that authors use to describe and designate the methodological approaches of their publications. For researchers who are new to case research methodology and are interested in learning more, Hancock and Algozzine provide a guide [ 20 ].

We hope that JMLA readers appreciate the rigor of well-executed case study research. We believe that distinguishing between descriptive case reports and analytic case studies in the journal’s submission categories will allow the depth of case study methodology to increase. We also hope that authors feel encouraged to pursue submitting relevant case studies or case reports for future publication.

Editor’s note: In response to this invited editorial, the Journal of the Medical Library Association will consider manuscripts employing rigorous qualitative case study methodology to be Original Investigations (fewer than 5,000 words), whereas manuscripts describing the process of developing, implementing, and assessing a new service, program, or initiative—typically in a single institution or through a single collaborative effort—will be considered to be Case Reports (formerly known as Case Studies; fewer than 3,000 words).

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Published: 22 November 2022

Single case studies are a powerful tool for developing, testing and extending theories

- Lyndsey Nickels ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0311-3524 1 , 2 ,

- Simon Fischer-Baum ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6067-0538 3 &

- Wendy Best ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8375-5916 4

Nature Reviews Psychology volume 1 , pages 733–747 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

681 Accesses

5 Citations

26 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neurological disorders

Psychology embraces a diverse range of methodologies. However, most rely on averaging group data to draw conclusions. In this Perspective, we argue that single case methodology is a valuable tool for developing and extending psychological theories. We stress the importance of single case and case series research, drawing on classic and contemporary cases in which cognitive and perceptual deficits provide insights into typical cognitive processes in domains such as memory, delusions, reading and face perception. We unpack the key features of single case methodology, describe its strengths, its value in adjudicating between theories, and outline its benefits for a better understanding of deficits and hence more appropriate interventions. The unique insights that single case studies have provided illustrate the value of in-depth investigation within an individual. Single case methodology has an important place in the psychologist’s toolkit and it should be valued as a primary research tool.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

55,14 € per year

only 4,60 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Comparing meta-analyses and preregistered multiple-laboratory replication projects

The fundamental importance of method to theory

A critical evaluation of the p-factor literature

Corkin, S. Permanent Present Tense: The Unforgettable Life Of The Amnesic Patient, H. M . Vol. XIX, 364 (Basic Books, 2013).

Lilienfeld, S. O. Psychology: From Inquiry To Understanding (Pearson, 2019).

Schacter, D. L., Gilbert, D. T., Nock, M. K. & Wegner, D. M. Psychology (Worth Publishers, 2019).

Eysenck, M. W. & Brysbaert, M. Fundamentals Of Cognition (Routledge, 2018).

Squire, L. R. Memory and brain systems: 1969–2009. J. Neurosci. 29 , 12711–12716 (2009).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Corkin, S. What’s new with the amnesic patient H.M.? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3 , 153–160 (2002).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Schubert, T. M. et al. Lack of awareness despite complex visual processing: evidence from event-related potentials in a case of selective metamorphopsia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 16055–16064 (2020).

Behrmann, M. & Plaut, D. C. Bilateral hemispheric processing of words and faces: evidence from word impairments in prosopagnosia and face impairments in pure alexia. Cereb. Cortex 24 , 1102–1118 (2014).

Plaut, D. C. & Behrmann, M. Complementary neural representations for faces and words: a computational exploration. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 251–275 (2011).

Haxby, J. V. et al. Distributed and overlapping representations of faces and objects in ventral temporal cortex. Science 293 , 2425–2430 (2001).

Hirshorn, E. A. et al. Decoding and disrupting left midfusiform gyrus activity during word reading. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113 , 8162–8167 (2016).

Kosakowski, H. L. et al. Selective responses to faces, scenes, and bodies in the ventral visual pathway of infants. Curr. Biol. 32 , 265–274.e5 (2022).

Harlow, J. Passage of an iron rod through the head. Boston Med. Surgical J . https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.11.2.281 (1848).

Broca, P. Remarks on the seat of the faculty of articulated language, following an observation of aphemia (loss of speech). Bull. Soc. Anat. 6 , 330–357 (1861).

Google Scholar

Dejerine, J. Contribution A L’étude Anatomo-pathologique Et Clinique Des Différentes Variétés De Cécité Verbale: I. Cécité Verbale Avec Agraphie Ou Troubles Très Marqués De L’écriture; II. Cécité Verbale Pure Avec Intégrité De L’écriture Spontanée Et Sous Dictée (Société de Biologie, 1892).

Liepmann, H. Das Krankheitsbild der Apraxie (“motorischen Asymbolie”) auf Grund eines Falles von einseitiger Apraxie (Fortsetzung). Eur. Neurol. 8 , 102–116 (1900).

Article Google Scholar

Basso, A., Spinnler, H., Vallar, G. & Zanobio, M. E. Left hemisphere damage and selective impairment of auditory verbal short-term memory. A case study. Neuropsychologia 20 , 263–274 (1982).

Humphreys, G. W. & Riddoch, M. J. The fractionation of visual agnosia. In Visual Object Processing: A Cognitive Neuropsychological Approach 281–306 (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1987).

Whitworth, A., Webster, J. & Howard, D. A Cognitive Neuropsychological Approach To Assessment And Intervention In Aphasia (Psychology Press, 2014).

Caramazza, A. On drawing inferences about the structure of normal cognitive systems from the analysis of patterns of impaired performance: the case for single-patient studies. Brain Cogn. 5 , 41–66 (1986).

Caramazza, A. & McCloskey, M. The case for single-patient studies. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 5 , 517–527 (1988).

Shallice, T. Cognitive neuropsychology and its vicissitudes: the fate of Caramazza’s axioms. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 32 , 385–411 (2015).

Shallice, T. From Neuropsychology To Mental Structure (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1988).

Coltheart, M. Assumptions and methods in cognitive neuropscyhology. In The Handbook Of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What Deficits Reveal About The Human Mind (ed. Rapp, B.) 3–22 (Psychology Press, 2001).

McCloskey, M. & Chaisilprungraung, T. The value of cognitive neuropsychology: the case of vision research. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 412–419 (2017).

McCloskey, M. The future of cognitive neuropsychology. In The Handbook Of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What Deficits Reveal About The Human Mind (ed. Rapp, B.) 593–610 (Psychology Press, 2001).

Lashley, K. S. In search of the engram. In Physiological Mechanisms in Animal Behavior 454–482 (Academic Press, 1950).

Squire, L. R. & Wixted, J. T. The cognitive neuroscience of human memory since H.M. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 34 , 259–288 (2011).

Stone, G. O., Vanhoy, M. & Orden, G. C. V. Perception is a two-way street: feedforward and feedback phonology in visual word recognition. J. Mem. Lang. 36 , 337–359 (1997).

Perfetti, C. A. The psycholinguistics of spelling and reading. In Learning To Spell: Research, Theory, And Practice Across Languages 21–38 (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1997).

Nickels, L. The autocue? self-generated phonemic cues in the treatment of a disorder of reading and naming. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 9 , 155–182 (1992).

Rapp, B., Benzing, L. & Caramazza, A. The autonomy of lexical orthography. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 14 , 71–104 (1997).

Bonin, P., Roux, S. & Barry, C. Translating nonverbal pictures into verbal word names. Understanding lexical access and retrieval. In Past, Present, And Future Contributions Of Cognitive Writing Research To Cognitive Psychology 315–522 (Psychology Press, 2011).

Bonin, P., Fayol, M. & Gombert, J.-E. Role of phonological and orthographic codes in picture naming and writing: an interference paradigm study. Cah. Psychol. Cogn./Current Psychol. Cogn. 16 , 299–324 (1997).

Bonin, P., Fayol, M. & Peereman, R. Masked form priming in writing words from pictures: evidence for direct retrieval of orthographic codes. Acta Psychol. 99 , 311–328 (1998).

Bentin, S., Allison, T., Puce, A., Perez, E. & McCarthy, G. Electrophysiological studies of face perception in humans. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 8 , 551–565 (1996).

Jeffreys, D. A. Evoked potential studies of face and object processing. Vis. Cogn. 3 , 1–38 (1996).

Laganaro, M., Morand, S., Michel, C. M., Spinelli, L. & Schnider, A. ERP correlates of word production before and after stroke in an aphasic patient. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 , 374–381 (2011).

Indefrey, P. & Levelt, W. J. M. The spatial and temporal signatures of word production components. Cognition 92 , 101–144 (2004).

Valente, A., Burki, A. & Laganaro, M. ERP correlates of word production predictors in picture naming: a trial by trial multiple regression analysis from stimulus onset to response. Front. Neurosci. 8 , 390 (2014).

Kittredge, A. K., Dell, G. S., Verkuilen, J. & Schwartz, M. F. Where is the effect of frequency in word production? Insights from aphasic picture-naming errors. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 25 , 463–492 (2008).

Domdei, N. et al. Ultra-high contrast retinal display system for single photoreceptor psychophysics. Biomed. Opt. Express 9 , 157 (2018).

Poldrack, R. A. et al. Long-term neural and physiological phenotyping of a single human. Nat. Commun. 6 , 8885 (2015).

Coltheart, M. The assumptions of cognitive neuropsychology: reflections on Caramazza (1984, 1986). Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 397–402 (2017).

Badecker, W. & Caramazza, A. A final brief in the case against agrammatism: the role of theory in the selection of data. Cognition 24 , 277–282 (1986).

Fischer-Baum, S. Making sense of deviance: Identifying dissociating cases within the case series approach. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 30 , 597–617 (2013).

Nickels, L., Howard, D. & Best, W. On the use of different methodologies in cognitive neuropsychology: drink deep and from several sources. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 475–485 (2011).

Dell, G. S. & Schwartz, M. F. Who’s in and who’s out? Inclusion criteria, model evaluation, and the treatment of exceptions in case series. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 515–520 (2011).

Schwartz, M. F. & Dell, G. S. Case series investigations in cognitive neuropsychology. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 27 , 477–494 (2010).

Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 112 , 155–159 (1992).

Martin, R. C. & Allen, C. Case studies in neuropsychology. In APA Handbook Of Research Methods In Psychology Vol. 2 Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, And Biological (eds Cooper, H. et al.) 633–646 (American Psychological Association, 2012).

Leivada, E., Westergaard, M., Duñabeitia, J. A. & Rothman, J. On the phantom-like appearance of bilingualism effects on neurocognition: (how) should we proceed? Bilingualism 24 , 197–210 (2021).

Arnett, J. J. The neglected 95%: why American psychology needs to become less American. Am. Psychol. 63 , 602–614 (2008).

Stolz, J. A., Besner, D. & Carr, T. H. Implications of measures of reliability for theories of priming: activity in semantic memory is inherently noisy and uncoordinated. Vis. Cogn. 12 , 284–336 (2005).

Cipora, K. et al. A minority pulls the sample mean: on the individual prevalence of robust group-level cognitive phenomena — the instance of the SNARC effect. Preprint at psyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/bwyr3 (2019).

Andrews, S., Lo, S. & Xia, V. Individual differences in automatic semantic priming. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 43 , 1025–1039 (2017).

Tan, L. C. & Yap, M. J. Are individual differences in masked repetition and semantic priming reliable? Vis. Cogn. 24 , 182–200 (2016).

Olsson-Collentine, A., Wicherts, J. M. & van Assen, M. A. L. M. Heterogeneity in direct replications in psychology and its association with effect size. Psychol. Bull. 146 , 922–940 (2020).

Gratton, C. & Braga, R. M. Editorial overview: deep imaging of the individual brain: past, practice, and promise. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 40 , iii–vi (2021).