Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Introduction

Nature of learning and play, categories of play, object play, physical, locomotor, or rough-and-tumble play, outdoor play, social or pretend play alone or with others, development of play, effects on brain structure and functioning, benefits of play, benefits to adults of playing with children, implications for preschool education, modern challenges, role of media in children’s play, barriers to play, role of pediatricians, conclusions, lead authors, contributor, committee on psychosocial aspects of child and family health, 2017–2018, council on communications and media, 2017–2018, the power of play: a pediatric role in enhancing development in young children.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Michael Yogman , Andrew Garner , Jeffrey Hutchinson , Kathy Hirsh-Pasek , Roberta Michnick Golinkoff , COMMITTEE ON PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF CHILD AND FAMILY HEALTH , COUNCIL ON COMMUNICATIONS AND MEDIA , Rebecca Baum , Thresia Gambon , Arthur Lavin , Gerri Mattson , Lawrence Wissow , David L. Hill , Nusheen Ameenuddin , Yolanda (Linda) Reid Chassiakos , Corinn Cross , Rhea Boyd , Robert Mendelson , Megan A. Moreno , MSEd , Jenny Radesky , Wendy Sue Swanson , MBE , Jeffrey Hutchinson , Justin Smith; The Power of Play: A Pediatric Role in Enhancing Development in Young Children. Pediatrics September 2018; 142 (3): e20182058. 10.1542/peds.2018-2058

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Children need to develop a variety of skill sets to optimize their development and manage toxic stress. Research demonstrates that developmentally appropriate play with parents and peers is a singular opportunity to promote the social-emotional, cognitive, language, and self-regulation skills that build executive function and a prosocial brain. Furthermore, play supports the formation of the safe, stable, and nurturing relationships with all caregivers that children need to thrive.

Play is not frivolous: it enhances brain structure and function and promotes executive function (ie, the process of learning, rather than the content), which allow us to pursue goals and ignore distractions.

When play and safe, stable, nurturing relationships are missing in a child’s life, toxic stress can disrupt the development of executive function and the learning of prosocial behavior; in the presence of childhood adversity, play becomes even more important. The mutual joy and shared communication and attunement (harmonious serve and return interactions) that parents and children can experience during play regulate the body’s stress response. This clinical report provides pediatric providers with the information they need to promote the benefits of play and and to write a prescription for play at well visits to complement reach out and read. At a time when early childhood programs are pressured to add more didactic components and less playful learning, pediatricians can play an important role in emphasizing the role of a balanced curriculum that includes the importance of playful learning for the promotion of healthy child development.

Since the publication of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Clinical Reports on the importance of play in 2007, 1 , 2 newer research has provided additional evidence of the critical importance of play in facilitating parent engagement; promoting safe, stable, and nurturing relationships; encouraging the development of numerous competencies, including executive functioning skills; and improving life course trajectories. 3 , – 5 An increasing societal focus on academic readiness (promulgated by the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001) has led to a focus on structured activities that are designed to promote academic results as early as preschool, with a corresponding decrease in playful learning. Social skills, which are part of playful learning, enable children to listen to directions, pay attention, solve disputes with words, and focus on tasks without constant supervision. 6 By contrast, a recent trial of an early mathematics intervention in preschool showed almost no gains in math achievement in later elementary school. 7 Despite criticism from early childhood experts, the 2003 Head Start Act reauthorization ended the program evaluation of social emotional skills and was focused almost exclusively on preliteracy and premath skills. 8 The AAP report on school readiness includes an emphasis on the importance of whole child readiness (including social–emotional, attentional, and cognitive skills). 9 Without that emphasis, children’s ability to pay attention and behave appropriately in the classroom is disadvantaged.

The definition of play is elusive. However, there is a growing consensus that it is an activity that is intrinsically motivated, entails active engagement, and results in joyful discovery. Play is voluntary and often has no extrinsic goals; it is fun and often spontaneous. Children are often seen actively engaged in and passionately engrossed in play; this builds executive functioning skills and contributes to school readiness (bored children will not learn well). 10 Play often creates an imaginative private reality, contains elements of make believe, and is nonliteral.

Depending on the culture of the adults in their world, children learn different skills through play. Sociodramatic play is when children act out the roles of adulthood from having observed the activities of their elders. Extensive studies of animal play suggest that the function of play is to build a prosocial brain that can interact effectively with others. 11

Play is fundamentally important for learning 21st century skills, such as problem solving, collaboration, and creativity, which require the executive functioning skills that are critical for adult success. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child has enshrined the right to engage in play that is appropriate to the age of the child in Article 21. 12 In its 2012 exhibit “The Century of the Child: 1900–2000,” the Museum of Modern Art noted, “Play is to the 21st century what work was to industrialization. It demonstrates a way of knowing, doing, and creating value.” 13 Resnick 14 has described 4 guiding principles to support creative learning in children: projects, passion, peers, and play. Play is not just about having fun but about taking risks, experimenting, and testing boundaries. Pediatricians can be influential advocates by encouraging parents and child care providers to play with children and to allow children to have unstructured time to play as well as by encouraging educators to recognize playful learning as an important complement to didactic learning. Some studies 15 , – 18 note that the new information economy, as opposed to the older industrial 1, demands more innovation and less imitation, more creativity and less conformity. Research on children’s learning indicates that learning thrives when children are given some agency (control of their own actions) to play a role in their own learning. 19 The demands of today’s world require that the teaching methods of the past 2 centuries, such as memorization, be replaced by innovation, application, and transfer. 18

Bruner et al 20 stressed the fact that play is typically buffered from real-life consequences. Play is part of our evolutionary heritage, occurs in a wide spectrum of species, is fundamental to health, and gives us opportunities to practice and hone the skills needed to live in a complex world. 21 Although play is present in a large swath of species within the animal kingdom, from invertebrates (such as the octopus, lizard, turtle, and honey bee) to mammals (such as rats, monkeys, and humans), 22 social play is more prominent in animals with a large neocortex. 23 Studies of animal behavior suggests that play provides animals and humans with skills that will help them with survival and reproduction. 24 Locomotor skills learned through rough-and-tumble play enables escape from predators. However, animals play even when it puts them at risk of predation. 25 It is also suggested that play teaches young animals what they can and cannot do at times when they are relatively free from the survival pressures of adult life. 26 Play and learning are inextricably linked. 27 A Russian psychologist recognized that learning occurs when children actively engage in practical activities within a supportive social context. The accumulation of new knowledge is built on previous learning, but the acquisition of new skills is facilitated by social and often playful interactions. He was interested in what he called the “zone of proximal development,” which consists of mastering skills that a child could not do alone but could be developed with minimal assistance. 28 Within the zone of proximal development, the “how” of learning occurs through a reiterative process called scaffolding, in which new skills are built on previous skills and are facilitated by a supportive social environment. The construct of scaffolding has been extrapolated to younger children. Consider how a social smile at 6 to 8 weeks of age invites cooing conversations, which leads to the reciprocal dance of social communication even before language emerges, followed by social referencing (the reading of a parent’s face for nonverbal emotional content). The balance between facilitating unstructured playtime for children and encouraging adult scaffolding of play will vary depending on the competing needs in individual families, but the “serve-and-return” aspect of play requires caregiver engagement. 29

Early learning and play are fundamentally social activities 30 and fuel the development of language and thought. Early learning also combines playful discovery with the development of social–emotional skills. It has been demonstrated that children playing with toys act like scientists and learn by looking and listening to those around them. 15 , – 17 However, explicit instructions limit a child’s creativity; it is argued that we should let children learn through observation and active engagement rather than passive memorization or direct instruction. Preschool children do benefit from learning content, but programs have many more didactic components than they did 20 years ago. 31 Successful programs are those that encourage playful learning in which children are actively engaged in meaningful discovery. 32 To encourage learning, we need to talk to children, let them play, and let them watch what we do as we go about our everyday lives. These opportunities foster the development of executive functioning skills that are critically important for the development of 21st century skills, such as collaboration, problem solving, and creativity, according to the 2010 IBM’s Global CEO Study. 33

Play has been categorized in a variety of ways, each with its own developmental sequence. 32 , 34

This type of play occurs when an infant or child explores an object and learns about its properties. Object play progresses from early sensorimotor explorations, including the use of the mouth, to the use of symbolic objects (eg, when a child uses a banana as a telephone) for communication, language, and abstract thought.

This type of play progresses from pat-a-cake games in infants to the acquisition of foundational motor skills in toddlers 35 and the free play seen at school recess. The development of foundational motor skills in childhood is essential to promoting an active lifestyle and the prevention of obesity. 36 , – 39 Learning to cooperate and negotiate promotes critical social skills. Extrapolation from animal data suggests that guided competition in the guise of rough-and-tumble play allows all participants to occasionally win and learn how to lose graciously. 40 Rough-and-tumble play, which is akin to the play seen in animals, enables children to take risks in a relatively safe environment, which fosters the acquisition of skills needed for communication, negotiation, and emotional balance and encourages the development of emotional intelligence. It enables risk taking and encourages the development of empathy because children are guided not to inflict harm on others. 25 , 30 , 40 The United Kingdom has modified its guidelines on play, arguing that the culture has gone too far by leaching healthy risks out of childhood: new guidelines on play by the national commission state, “The goal is not to eliminate risk.” 41

Outdoor play provides the opportunity to improve sensory integration skills. 36 , 37 , 39 These activities involve the child as an active participant and address motor, cognitive, social, and linguistic domains. Viewed in this light, school recess becomes an essential part of a child’s day. 42 It is not surprising that countries that offer more recess to young children see greater academic success among the children as they mature. 42 , 43 Supporting and implementing recess not only sends a message that exercise is fundamentally important for physical health but likely brings together children from diverse backgrounds to develop friendships as they learn and grow. 42

This type of play occurs when children experiment with different social roles in a nonliteral fashion. Play with other children enables them to negotiate “the rules” and learn to cooperate. Play with adults often involves scaffolding, as when an adult rotates a puzzle to help the child place a piece. Smiling and vocal attunement, in which infants learn turn taking, is the earliest example of social play. Older children can develop games and activities through which they negotiate relationships and guidelines with other players. Dress up, make believe, and imaginary play encourage the use of more sophisticated language to communicate with playmates and develop common rule-bound scenarios (eg, “You be the teacher, and I will be the student”).

Play has also been grouped as self-directed versus adult guided. Self-directed play, or free play, is crucial to children’s exploration of the world and understanding of their preferences and interests. 19 , 32 , 44 Guided play retains the child agency, such that the child initiates the play, but it occurs either in a setting that an adult carefully constructs with a learning goal in mind (eg, a children’s museum exhibit or a Montessori task) or in an environment where adults supplement the child-led exploration with questions or comments that subtly guide the child toward a goal. Board games that have well-defined goals also fit into this category. 45 For example, if teachers want children to improve executive functioning skills (see the “Tools of the Mind” curriculum), 46 they could create drum-circle games, in which children coregulate their behavior. Familiar games such as “Simon Says” or “Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes” ask children to control their individual actions or impulses and have been shown to improve executive functioning skills. 47 Guided play has been defined as a child-led, joyful activity in which adults craft the environment to optimize learning. 4 , 48 This approach harkens back to Vygotsky 28 and the zone of proximal development, which represents the skills that children are unable to master on their own but are able to master in the context of a safe, stable, and nurturing relationship with an adult. The guidance and dialogue provided by the adult allow the child to master skills that would take longer to master alone and help children focus on the elements of the activity to guide learning. One way to think about guided play is as “constrained tinkering.” 14 , 48 This logic also characterizes Italy’s Emilio Reggio approach, which emphasizes the importance of teaching children to listen and look.

According to Vygotsky, 28 the most efficient learning occurs in a social context, where learning is scaffolded by the teacher into meaningful contexts that resonate with children’s active engagement and previous experiences. Scaffolding is a part of guided play; caregivers are needed to provide the appropriate amount of input and guidance for children to develop optimal skills.

How does play develop? Play progresses from social smiling to reciprocal serve-and-return interactions; the development of babbling; games, such as “peek-a-boo”; hopping, jumping, skipping, and running; and fantasy or rough-and-tumble play. The human infant is born immature compared with infants of other species, with substantial brain development occurring after birth. Infants are entirely dependent on parents to regulate sleep–wake rhythms, feeding cycles, and many social interactions. Play facilitates the progression from dependence to independence and from parental regulation to self-regulation. It promotes a sense of agency in the child. This evolution begins in the first 3 months of life, when parents (both mothers and fathers) interact reciprocally with their infants by reading their nonverbal cues in a responsive, contingent manner. 49 Caregiver–infant interaction is the earliest form of play, known as attunement, 50 but it is quickly followed by other activities that also involve the taking of turns. These serve-and-return behaviors promote self-regulation and impulse control in children and form a strong foundation for understanding their interaction with adults. The back-and-forth episodes also feed into the development of language.

Reciprocal games occur with both mothers and fathers 51 and often begin in earnest with the emergence of social smiles at 6 weeks of age. Parents mimic their infant’s “ooh” and “ah” in back-and-forth verbal games, which progress into conversations in which the parents utter pleasantries (“Oh, you had a good lunch!”), and the child responds by vocalizing back. Uncontrollable crying as a response to stress in a 1-year-old is replaced as the child reaches 2 to 3 years of age with the use of words to self-soothe, building on caregivers scaffolding their emotional responses. Already by 6 months of age, the introduction of solid foods requires the giving and receiving of reciprocal signals and communicative cues. During these activities, analyses of physiologic heart rate rhythms of infants with both their mothers and fathers have shown synchrony. 49 , 52

By 9 months of age, mutual regulation is manifested in the way infants use their parents for social referencing. 53 , 54 In the classic visual cliff experiment, it was demonstrated that an infant will crawl across a Plexiglas dropoff to explore if the mother encourages the infant but not if she frowns. Nonverbal communication slowly leads to formal verbal language skills through which emotions such as happiness, sadness, and anger are identified for the child via words. Uncontrollable crying in the 1-year-old then becomes whining in the 2-year-old and verbal requests for assistance in the 3-year-old as parents scaffold the child’s emotional responses and help him or her develop alternative, more adaptive behaviors. Repetitive games, such as peek-a-boo and “this little piggy,” offer children the joy of being able to predict what is about to happen, and these games also enhance the infants’ ability to solicit social stimulation.

By 12 months of age, a child’s experiences are helping to lay the foundation for the ongoing development of social skills. The expression of true joy and mastery on children’s faces when they take their first step is truly a magical moment that all parents remember. Infant memory, in Piagetian terms, develops as infants develop object permanence through visible and invisible displacements, such as repetitive games like peek-a-boo. With the advent of locomotor skills, rough-and-tumble play becomes increasingly available. During the second year, toddlers learn to explore their world, develop the beginnings of self-awareness, and use their parents as a home base (secure attachment), frequently checking to be sure that the world they are exploring is safe. 55 As children become independent, their ability to socially self-regulate becomes apparent: they can focus their attention and solve problems efficiently, they are less impulsive, and they can better manage the stress of strong emotions. 56 With increased executive functioning skills, they can begin to reflect on how they should respond to a situation rather than reacting impulsively. With the development of language and symbolic functioning, pretend play now becomes more prominent. 57 Fantasy play, dress up, and fort building now join the emotional and social repertoire of older children just as playground activities, tag, and hide and seek develop motor skills. In play, children are also solving problems and learning to focus attention, all of which promote the growth of executive functioning skills.

Play is not frivolous; it is brain building. Play has been shown to have both direct and indirect effects on brain structure and functioning. Play leads to changes at the molecular (epigenetic), cellular (neuronal connectivity), and behavioral levels (socioemotional and executive functioning skills) that promote learning and adaptive and/or prosocial behavior. Most of this research on brain structure and functioning has been done with rats and cannot be directly extrapolated to humans.

Jaak Panksepp, 11 a neuroscientist and psychologist who has extensively studied the neurologic basis of emotion in animals, suggests that play is 1 of 7 innate emotional systems in the midbrain. 58 Rats love rough-and-tumble play and produce a distinctive sound that Panksepp labeled “rat laughter.” 42 , 59 , – 64 When rats are young, play appears to initiate lasting changes in areas of the brain that are used for thinking and processing social interaction.

The dendritic length, complexity, and spine density of the medial prefrontal cortex (PFC) are refined by play. 64 , – 67 The brain-derived neurotrophic factor ( BDNF ) is a member of the neurotrophin family of growth factors that acts to support the survival of existing neurons and encourage the growth and differentiation of new neurons and synapses. It is known to be important for long-term memory and social learning. Play stimulates the production of BDNF in RNA in the amygdala, dorsolateral frontal cortex, hippocampus, and pons. 65 , 68 , – 70 Gene expression analyses indicate that the activities of approximately one-third of the 1200 genes in the frontal and posterior cortical regions were significantly modified by play within an hour after a 30-minute play session. 69 , 70 The gene that showed the largest effect was BDNF . Conversely, rat pup adversity, depression, and stress appear to result in the methylation and downregulation of the BDNF gene in the PFC. 71

Two hours per day of play with objects predicted changes in brain weight and efficiency in experimental animals. 11 , 66 Rats that were deprived of play as pups (kept in sparse cages devoid of toys) not only were less competent at problem solving later on (negotiating mazes) but the medial PFC of the play-deprived rats was significantly more immature, suggesting that play deprivation interfered with the process of synaptogenesis and pruning. 72 Rat pups that were isolated during peak play periods after birth (weeks 4 and 5) are much less socially active when they encounter other rats later in life. 73 , 74

Play-deprived rats also showed impaired problem-solving skills, suggesting that through play, animals learn to try new things and develop behavioral flexibility. 73 Socially reared rats with damage to their PFC mimic the social deficiencies of rats with intact brains but who were deprived of play as juveniles. 66 The absence of the play experience leads to anatomically measurable changes in the neurons of the PFC. By refining the functional organization of the PFC, play enhances the executive functioning skills derived from this part of the brain. 66 Whether these effects are specific to play deprivation or merely reflect the generic effect of a lack of stimulation requires further study. Rats that were raised in experimental toy-filled cages had bigger brains and thicker cerebral cortices and completed mazes more quickly. 67 , 75

Brain neurotransmitters, such as dopamine made by cells in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmentum, are also related to the reward quality of play: drugs that activate dopamine receptors increase play behavior in rats. 76

Play and stress are closely linked. High amounts of play are associated with low levels of cortisol, suggesting either that play reduces stress or that unstressed animals play more. 23 Play also activates norepinephrine, which facilitates learning at synapses and improves brain plasticity. Play, especially when accompanied by nurturing caregiving, may indirectly affect brain functioning by modulating or buffering adversity and by reducing toxic stress to levels that are more compatible with coping and resilience. 77 , 78

In human children, play usually enhances curiosity, which facilitates memory and learning. During states of high curiosity, functional MRI results showed enhanced activity in healthy humans in their early 20s in the midbrain and nucleus accumbens and functional connectivity to the hippocampus, which solidifies connections between intrinsic motivation and hippocampus-dependent learning. 79 Play helps children deal with stress, such as life transitions. When 3- to 4-year-old children who were anxious about entering preschool were randomly assigned to play with toys or peers for 15 minutes compared with listening to a teacher reading a story, the play group showed a twofold decrease in anxiety after the intervention. 24 , 80 In another study, preschool children with disruptive behavior who engaged with teachers in a yearlong 1-to-1 play session designed to foster warm, caring relationships (allowing children to lead, narrating the children’s behavior out loud, and discussing the children’s emotions as they played) showed reduced salivary cortisol stress levels during the day and improved behavior compared with children in the control group. 81 The notable exception is with increased stress experienced by children with autism spectrum disorders in new or social circumstances. 82 Animal studies suggest the role of play as a social buffer. Rats that were previously induced to be anxious became relaxed and calm after rough-and-tumble play with a nonanxious playful rat. 83 Extrapolating from these animal studies, one can suggest that play may serve as an effective buffer for toxic stress.

The benefits of play are extensive and well documented and include improvements in executive functioning, language, early math skills (numerosity and spatial concepts), social development, peer relations, physical development and health, and enhanced sense of agency. 13 , 32 , 56 , 57 , 84 , – 88 The opposite is also likely true; Panksepp 89 suggested that play deprivation is associated with the increasing prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. 90

Executive functioning, which is described as the process of how we learn over the content of what we learn, is a core benefit of play and can be characterized by 3 dimensions: cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, and working memory. Collectively, these dimensions allow for sustained attention, the filtering of distracting details, improved self-regulation and self-control, better problem solving, and mental flexibility. Executive functioning helps children switch gears and transition from drawing with crayons to getting dressed for school. The development of the PFC and executive functioning balances and moderates the impulsiveness, emotionality, and aggression of the amygdala. In the presence of childhood adversity, the role of play becomes even more important in that the mutual joy and shared attunement that parents and children can experience during play downregulates the body’s stress response. 91 , – 94 Hence, play may be an effective antidote to the changes in amygdala size, impulsivity, aggression, and uncontrolled emotion that result from significant childhood adversity and toxic stress. Future research is needed to clarify this association.

Opportunities for peer engagement through play cultivate the ability to negotiate. Peer play usually involves problem solving about the rules of the game, which requires negotiation and cooperation. Through these encounters, children learn to use more sophisticated language when playing with peers. 95 , 96

Play in a variety of forms (active physical play, pretend play, and play with traditional toys and shape sorters [rather than digital toys]) improves children’s skills. When children were given blocks to play with at home with minimal adult direction, preschool children showed improvements in language acquisition at a 6-month follow-up, particularly low-income children. The authors suggest that the benefits of Reach Out and Play may promote development just as Reach Out and Read does. 97 When playing with objects under minimal adult direction, preschool children named an average of 3 times as many nonstandard uses for an object compared with children who were given specific instructions. 98 In Jamaica, toddlers with growth retardation who were given weekly play sessions to improve mother–child interactions for 2 years were followed to adulthood and showed better educational attainment, less depression, and less violent behavior. 3

Children who were in active play for 1 hour per day were better able to think creatively and multitask. 22 Randomized trials of physical play in 7- to 9-year-olds revealed enhanced attentional inhibition, cognitive flexibility, and brain functioning that were indicative of enhanced executive control. 99 Play with traditional toys was associated with an increased quality and quantity of language compared with play with electronic toys, 100 particularly if the video toys did not encourage interaction. 101 Indeed, it has been shown that play with digital shape sorters rather than traditional shape sorters stunted the parent’s use of spatial language. 102 Pretend play encourages self-regulation because children must collaborate on the imaginary environment and agree about pretending and conforming to roles, which improves their ability to reason about hypothetical events. 56 , 57 , 103 , – 105 Social–emotional skills are increasingly viewed as related to academic and economic success. 106 Third-grade prosocial behavior correlated with eighth-grade reading and math better than with third-grade reading and math. 17 , 107

The health benefits of play involving physical activity are many. Exercise not only promotes healthy weight and cardiovascular fitness but also can enhance the efficacy of the immune, endocrine, and cardiovascular systems. 37 Outdoor playtime for children in Head Start programs has been associated with decreased BMI. 39 Physical activity is associated with decreases in concurrent depressive symptoms. 108 Play decreases stress, fatigue, injury, and depression and increases range of motion, agility, coordination, balance, and flexibility. 109 Children pay more attention to class lessons after free play at recess than they do after physical education programs, which are more structured. 43 Perhaps they are more active during free play.

Play also reflects and transmits cultural values. In fact, recess began in the United States as a way to socially integrate immigrant children. Parents in the United States encourage children to play with toys and/or objects alone, which is typical of communities that emphasize the development of independence. Conversely, in Japan, peer social play with dolls is encouraged, which is typical of cultures that emphasize interdependence. 110

Playing with children adds value not only for children but also for adult caregivers, who can reexperience or reawaken the joy of their own childhood and rejuvenate themselves. Through play and rereading their favorite childhood books, parents learn to see the world from their child’s perspective and are likely to communicate more effectively with their child, even appreciating and sharing their child’s sense of humor and individuality. Play enables children and adults to be passionately and totally immersed in an activity of their choice and to experience intense joy, much as athletes do when they are engaging in their optimal performance. Discovering their true passions is another critical strategy for helping both children and adults cope with adversity. One study documented that positive parenting activities, such as playing and shared reading, result in decreases in parental experiences of stress and enhancement in the parent–child relationship, and these effects mediate relations between the activities and social–emotional development. 111 , – 113

Most importantly, play is an opportunity for parents to engage with their children by observing and understanding nonverbal behavior in young infants, participating in serve-andreturn exchanges, or sharing the joy and witnessing the blossoming of the passions in each of their children.

Play not only provides opportunities for fostering children’s curiosity, 14 self-regulation skills, 46 language development, and imagination but also promotes the dyadic reciprocal interactions between children and parents, which is a crucial element of healthy relationships. 114 Through the buffering capacity of caregivers, play can serve as an antidote to toxic stress, allowing the physiologic stress response to return to baseline. 77 Adult success in later life can be related to the experience of childhood play that cultivated creativity, problem solving, teamwork, flexibility, and innovations. 18 , 52 , 115

Successful scaffolding (new skills built on previous skills facilitated by a supportive social environment) can be contrasted with interactions in which adults direct children’s play. It has been shown that if a caregiver instructs a child in how a toy works, the child is less likely to discover other attributes of the toy in contrast to a child being left to explore the toy without direct input. 38 , 116 , – 118 Adults who facilitate a child’s play without being intrusive can encourage the child’s independent exploration and learning.

Scaffolding play activities facilitated by adults enable children to work in groups: to share, negotiate, develop decision-making and problem-solving skills, and discover their own interests. Children learn to resolve conflicts and develop self-advocacy skills and their own sense of agency. The false dichotomy between play versus formal learning is now being challenged by educational reformers who acknowledge the value of playful learning or guided play, which captures the strengths of both approaches and may be essential to improving executive functioning. 18 , 19 , 34 , 119 Hirsh-Pasek et al 34 report a similar finding: children have been shown to discover causal mechanisms more quickly when they drive their learning as opposed to when adults display solutions for them.

Executive functioning skills are foundational for school readiness and academic success, mandating a frame shift with regard to early education. The goal today is to support interventions that cultivate a range of skills, such as executive functioning, in all children so that the children enter preschool and kindergarten curious and knowing how to learn. Kindergarten should provide children with an opportunity for playful collaboration and tinkering, 14 a different approach from the model that promotes more exclusive didactic learning at the expense of playful learning. The emerging alternative model is to prevent toxic stress and build resilience by developing executive functioning skills. Ideally, we want to protect the brain to enable it to learn new skills, and we want to focus on learning those skills that will be used to buffer the brain from any future adversity. 18 The Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University offers an online resource on play and executive functioning with specific activities suggested for parents and children ( http://developingchild.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Enhancing-and-Practicing-Executive-Function-Skills-with-Children-from-Infancy-to-Adolescence-1.pdf ). 120

Specific curricula have now been developed and tested in preschools to help children develop executive functioning skills. Many innovative programs are using either the Reggio Emilia philosophy or curricula such as Tools of the Mind (developed in California) 121 or Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies–Preschool and/or Kindergarten. 122 Caregivers need to provide the appropriate amount of input and guidance for children to develop optimal problem-solving skills through guided play and scaffolding. Optimal learning can be depicted by a bell-shaped curve, which illustrates the optimal zone of arousal and stress for complex learning. 123

Scaffolding is extensively used to support skills such as buddy reading, in which children take turns being lips and ears and learn to read and listen to each other as an example of guided play. A growing body of research shows that this curriculum not only improves executive functioning skills but also shows improvement in brain functioning on functional MRI. 6 , 124 , – 126

Focusing on cultivating executive functioning and other skills through playful learning in these early years is an alternative and innovative way of thinking about early childhood education. Instead of focusing solely on academic skills, such as reciting the alphabet, early literacy, using flash cards, engaging with computer toys, and teaching to tests (which has been overemphasized to promote improved test results), cultivating the joy of learning through play is likely to better encourage long-term academic success. Collaboration, negotiation, conflict resolution, self-advocacy, decision-making, a sense of agency, creativity, leadership, and increased physical activity are just some of the skills and benefits children gain through play.

For many families, there are risks in the current focus only on achievement, after-school enrichment programs, increased homework, concerns about test performance, and college acceptance. The stressful effects of this approach often result in the later development of anxiety and depression and a lack of creativity. Parental guilt has led to competition over who can schedule more “enrichment opportunities” for their children. As a result, there is little time left in the day for children’s free play, for parental reading to children, or for family meal times. Many schools have cut recess, physical education, art, and music to focus on preparing children for tests. Unsafe local neighborhoods and playgrounds have led to nature deficit disorder for many children. 127 A national survey of 8950 preschool children and parents found that only 51% of children went outside to walk or play once per day with either parent. 128 In part, this may reflect the local environment: 94% of parents have expressed safety concerns about outdoor play, and access may be limited. Only 20% of homes are located within a half-mile of a park. 129 , 130 Cultural changes have also jeopardized the opportunities children have to play. From 1981 to 1997, children’s playtime decreased by 25%. Children 3 to 11 years of age have lost 12 hours per week of free time. Because of increased academic pressure, 30% of US kindergarten children no longer have recess. 42 , 129 An innovative program begun in Philadelphia is using cities (on everyday walks and in everyday neighborhoods) as opportunities for creating learning landscapes that provide opportunities for parents and children to spark conversation and playful learning. 131 , 132 For example, Ridge et al 132 have placed conversational prompts throughout supermarkets and laundromats to promote language and lights at bus stops to project designs on the ground, enabling children to play a game of hopscotch that is specifically designed to foster impulse control. By promoting the learning of social and emotional skills, the development of emotional intelligence, and the enjoyment of active learning, protected time for free play and guided play can be used to help children improve their social skills, literacy, and school readiness. Children can then enter school with a stronger foundation for attentional disposition based on the skills and attitudes that are critical for academic success and the long-term enjoyment of learning and love of school.

Media (eg, television, video games, and smartphone and tablet applications) use often encourages passivity and the consumption of others’ creativity rather than active learning and socially interactive play. Most importantly, immersion in electronic media takes away time from real play, either outdoors or indoors. Real learning happens better in person-to-person exchanges rather than machine-to-person interactions. Most parents are eager to do the right thing for their children. However, advertisers and the media can mislead parents about how to best support and encourage their children’s growth and development as well as creativity. Parent surveys have revealed that many parents see media and technology as the best way to help their children learn. 133 However, researchers contradict this. Researchers have compared preschoolers playing with blocks independently with preschoolers watching Baby Einstein tapes and have shown that the children playing with blocks independently developed better language and cognitive skills than their peers watching videos. 34 , 134 Although active engagement with age-appropriate media, especially if supported by cowatching or coplay with peers or parents, may have some benefits, 135 real-time social interactions remain superior to digital media for home learning. 136

It is important for parents to understand that media use often does not support their goals of encouraging curiosity and learning for their children. 137 , – 141 Despite research that reveals an association between television watching and a sedentary lifestyle and greater risks of obesity, the typical preschooler watches 4.5 hours of television per day, which displaces conversation with parents and the practice of joint attention (focus by the parent and child on a common object) as well as physical activity. For economically challenged families, competing pressures make it harder for parents to find the time to play with children. Encouraging outdoor exercise may be more difficult for such families given unsafe playgrounds. Easy access to electronic media can be difficult for parents to compete with.

In the 2015 symposium, 137 the AAP clarified recommendations acknowledging the ubiquity and transformation of media from primarily television to other modalities, including video chatting. In 2016, the AAP published 2 new policies on digital media affecting young children, school-aged children, and adolescents. These policies included recommendations for parents, pediatricians, and researchers to promote healthy media use. 139 , 140 The AAP has also launched a Family Media Use Plan to help parents and families create healthy guidelines for their children’s media use so as to avoid displacing activities such as active play, and guidelines can also be found on the HealthyChildren.org and Common Sense Media (commonsensemedia.org) Web sites.

There are barriers to encouraging play. Our culture is preoccupied with marketing products to young children. 142 Parents of young children who cannot afford expensive toys may feel left out. 143 Parents who can afford expensive toys and electronic devices may think that allowing their children unfettered access to these objects is healthy and promotes learning. The reality is that children’s creativity and play is enhanced by many inexpensive toys (eg, wooden spoons, blocks, balls, puzzles, crayons, boxes, and simple available household objects) and by parents who engage with their children by reading, watching, playing alongside their children, and talking with and listening to their children. It is parents’ and caregivers’ presence and attention that enrich children, not elaborate electronic gadgets. One-on-one play is a time-tested way of being fully present. Low-income families may have less time to play with their children while working long hours to provide for their families, but a warm caregiver or extended family as well as a dynamic community program can help support parents’ efforts. 144 The importance of playtime with children cannot be overemphasized to parents as well as schools and community organizations. Many children do not have safe places to play. 145 Neighborhood threats, such as violence, guns, drugs, and traffic, pose safety concerns in many neighborhoods, particularly low-income areas. Children in low-income, urban neighborhoods also may have less access to quality public spaces and recreational facilities in their communities. 145 Parents who feel that their neighborhoods are unsafe may also not permit their children to play outdoors or independently.

Public health professionals are increasingly partnering with other sectors, such as parks and recreation, public safety, and community development, to advocate for safe play environments in all communities. This includes efforts to reduce community violence, improve physical neighborhood infrastructure, and support planning and design decisions that foster safe, clean, and accessible public spaces.

Pediatricians can advocate for the importance of all forms of play as well as for the role of play in the development of executive functioning, emotional intelligence, and social skills ( Table 1 ). Pediatricians have a critical role to play in protecting the integrity of childhood by advocating for all children to have the opportunity to express their innate curiosity in the world and their great capacity for imagination. For children with special needs, it is especially important to create safe opportunities for play. A children’s museum may offer special mornings when it is open only to children with special needs. Extra staffing enables these children and their siblings to play in a safe environment because they may not be able to participate during crowded routine hours.

Recommendations From Pediatricians to Parents

Adapted from pathways.org ( https://pathways.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/PlayBrochure_English_LEGAL_FOR-PRINT_2022.pdf ).

The AAP recommends that pediatricians:

Encourage parents to observe and respond to the nonverbal behavior of infants during their first few months of life (eg, responding to their children’s emerging social smile) to help them better understand this unique form of communication. For example, encouraging parents to recognize their children’s emerging social smile and to respond with a smile of their own is a form of play that also teaches the infants a critical social–emotional skill: “You can get my attention and a smile from me anytime you want just by smiling yourself.” By encouraging parents to observe the behavior of their children, pediatricians create opportunities to engage parents in discussions that are nonjudgmental and free from criticism (because they are grounded in the parents’ own observations and interpretations of how to promote early learning);

Advocate for the protection of children’s unstructured playtime because of its numerous benefits, including the development of foundational motor skills that may have lifelong benefits for the prevention of obesity, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes;

Advocate with preschool educators to do the following: focus on playful rather than didactic learning by letting children take the lead and follow their own curiosity; put a premium on building social–emotional and executive functioning skills throughout the school year; and protect time for recess and physical activity;

Emphasize the importance of playful learning in preschool curricula for fostering stronger caregiver–infant relationships and promoting executive functioning skills. Communicating this message to policy makers, legislators, and educational administrators as well as the broader public is equally important; and

Just as pediatricians support Reach Out and Read, encourage playful learning for parents and infants by writing a “prescription for play” at every well-child visit in the first 2 years of life.

A recent randomized controlled trial of the Video Interaction Project (an enhancement of Reach Out and Read) has demonstrated that the promotion of reading and play during pediatric visits leads to enhancements in social–emotional development. 112 In today’s world, many parents do not appreciate the importance of free play or guided play with their children and have come to think of worksheets and other highly structured activities as play. 146 Although many parents feel that they do not have time to play with their children, pediatricians can help parents understand that playful learning moments are everywhere, and even daily chores alongside parents can be turned into playful opportunities, especially if the children are actively interacting with parents and imitating chores. Young children typically seek more attention from parents. 46 Active play stimulates children’s curiosity and helps them develop the physical and social skills needed for school and later life. 32

Cultural shifts, including less parent engagement because of parents working full-time, fewer safe places to play, and more digital distractions, have limited the opportunities for children to play. These factors may negatively affect school readiness, children’s healthy adjustment, and the development of important executive functioning skills;

Play is intrinsically motivated and leads to active engagement and joyful discovery. Although free play and recess need to remain integral aspects of a child’s day, the essential components of play can also be learned and adopted by parents, teachers, and other caregivers to promote healthy child development and enhance learning;

The optimal educational model for learning is for the teacher to engage the student in activities that promote skills within that child’s zone of proximal development, which is best accomplished through dialogue and guidance, not via drills and passive rote learning. There is a current debate, particularly about preschool curricula, between an emphasis on content and attempts to build skills by introducing seat work earlier versus seeking to encourage active engagement in learning through play. With our understanding of early brain development, we suggest that learning is better fueled by facilitating the child’s intrinsic motivation through play rather than extrinsic motivations, such as test scores;

An alternative model for learning is for teachers to develop a safe, stable, and nurturing relationship with the child to decrease stress, increase motivation, and ensure receptivity to activities that promote skills within each child’s zone of proximal development. The emphasis in this preventive and developmental model is to promote resilience in the presence of adversity by enhancing executive functioning skills with free play and guided play;

Play provides ample opportunities for adults to scaffold the foundational motor, social–emotional, language, executive functioning, math, and self-regulation skills needed to be successful in an increasingly complex and collaborative world. Play helps to build the skills required for our changing world; and

Play provides a singular opportunity to build the executive functioning that underlies adaptive behaviors at home; improve language and math skills in school; build the safe, stable, and nurturing relationships that buffer against toxic stress; and build social–emotional resilience.

For more information, see Kearney et al’s Using Joyful Activity To Build Resiliency in Children in Response to Toxic Stress . 147

American Academy of Pediatrics

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

prefrontal cortex

Dr Yogman prepared the first draft of this report and took the lead in reconciling the numerous edits, contributions, and suggestions from the other authors; Drs Garner, Hutchinson, Hirsh-Pasek, and Golinkoff made significant contributions to the manuscript by revising multiple drafts and responding to all reviewer concerns; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University or the Department of Defense.

FUNDING: No external funding.

This document is copyrighted and is property of the American Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors. All authors have filed conflict of interest statements with the American Academy of Pediatrics. Any conflicts have been resolved through a process approved by the Board of Directors. The American Academy of Pediatrics has neither solicited nor accepted any commercial involvement in the development of the content of this publication.

Clinical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics benefit from expertise and resources of liaisons and internal (AAP) and external reviewers. However, clinical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics may not reflect the views of the liaisons or the organizations or government agencies that they represent.

The guidance in this report does not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or serve as a standard of medical care. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate.

All clinical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics automatically expire 5 years after publication unless reaffirmed, revised, or retired at or before that time.

Michael Yogman, MD, FAAP

Andrew Garner, MD, PhD, FAAP

Jeffrey Hutchinson, MD, FAAP

Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, PhD

Roberta Golinkoff, PhD

Virginia Keane, MD, FAAP

Michael Yogman, MD, FAAP, Chairperson

Rebecca Baum, MD, FAAP

Thresia Gambon, MD, FAAP

Arthur Lavin, MD, FAAP

Gerri Mattson, MD, FAAP

Lawrence Wissow, MD, MPH, FAAP

Sharon Berry, PhD, LP – Society of Pediatric Psychology

Amy Starin, PhD, LCSW – National Association of Social Workers

Edward Christophersen, PhD, FAAP – Society of Pediatric Psychology

Norah Johnson, PhD, RN, CPNP-BC – National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners

Abigail Schlesinger, MD – American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Karen S. Smith

David L Hill, MD, FAAP, Chairperson

Nusheen Ameenuddin, MD, MPH, FAAP

Yolanda (Linda) Reid Chassiakos, MD, FAAP

Corinn Cross, MD, FAAP

Rhea Boyd, MD, FAAP

Robert Mendelson, MD, FAAP

Megan A Moreno, MD, MSEd, MPH, FAAP

Jenny Radesky, MD, FAAP

Wendy Sue Swanson, MD, MBE, FAAP

Justin Smith, MD, FAAP

Kristopher Kaliebe, MD – American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Jennifer Pomeranz, JD, MPH – American Public Health Association Health Law Special Interest Group

Brian Wilcox, PhD – American Psychological Association

Thomas McPheron

Competing Interests

Advertising Disclaimer »

Citing articles via

Email alerts.

Affiliations

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Policies

- Journal Blogs

- Pediatrics On Call

- Online ISSN 1098-4275

- Print ISSN 0031-4005

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations, advertising.

- Privacy Statement | Accessibility Statement | Terms of Use | Support Center | Contact Us

- © Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

- Open access

- Published: 22 May 2021

Fostering socio-emotional learning through early childhood intervention

- Christina F. Mondi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1619-6389 1 ,

- Alison Giovanelli 2 &

- Arthur J. Reynolds 3

International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy volume 15 , Article number: 6 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

35k Accesses

19 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Educators and researchers are increasingly interested in evaluating and promoting socio-emotional learning (SEL) beginning in early childhood (Newman & Dusunbury in 2015; Zigler & Trickett in American Psychologist 33(9):789–798 https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.33.9.789 , 1978). Decades of research have linked participation in high-quality early childhood education (ECE) programs (e.g., public prekindergarten, Head Start) to multidimensional wellbeing. ECE programs also have demonstrated potential to be implemented at large scales with strong financial returns on investment. However, relatively few studies have investigated the effects of ECE programs on SEL, particularly compared to smaller-scale, skills-based SEL interventions. Furthermore, among studies that have examined SEL, there is a general lack of consensus about how to define and measure SEL in applied settings. The present paper begins to address these gaps in several ways. First, it discusses conceptual and methodological issues related to developmentally and culturally sensitive assessment of young children’s socio-emotional functioning. Second, it reviews the empirical research literature on the impacts of three types of early childhood programs (general prekindergarten programs; multi-component prekindergarten programs; and universal skills-based interventions) on SEL. Finally, it highlights future directions for research and practice.

Fostering socio-emotional learning through early childhood programming

What are the best ways to assess the effectiveness of early childhood intervention programs? This question has been debated for decades, and the answer has tremendous implications for public policy. During the mid-twentieth century, many research studies primarily examined whether intervention participation led to improvements in children’s IQ scores. Some researchers, however, argued for a more multidimensional approach to assessing intervention outcomes. Edward Zigler, one of the architects of Head Start, notably proposed that the primary outcome of interest in early childhood interventions should be children’s “social competence” (Raver & Zigler, 1997 ; Zigler & Trickett, 1978 ). Interest in social competence grew in the second half of the twentieth century, with numerous studies indicating that socio-emotional and motivational variables exert significant impacts on wellbeing in childhood and beyond (Greenberg et al., 2003 ; Jones et al., 2015 ). By the turn of the twenty-first century, a national sample of teachers reported that they believed that the ability to regulate emotions and behaviors is the most important component of school readiness (Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2000 ).

Today, educators and researchers continue to be interested in evaluating and promoting socio-emotional learning (SEL) starting in early childhood. Early childhood SEL skills develop rapidly, are uniquely malleable, and are strongly associated with later social, academic, cognitive, and health outcomes (Zins et al., 2007 ). Skills-based interventions that specifically target children’s SEL have been a major area of investigation (McClelland et al., 2017 ). However, relatively less is known about the impacts of large-scale early childhood education (ECE) programs on SEL, despite the potential of such programs to effect broad impacts. Furthermore, despite the growing enthusiasm surrounding the concept of SEL, many of the same methodological issues that Zigler and colleagues described in the 1970s still persist. Review of the literature reveals a lack of consensus among researchers and practitioners regarding how to define, evaluate, and promote SEL.

McCabe and Altamura ( 2011 ) previously reviewed the impact of a variety of preschool interventions on SEL, including both skills-based interventions and comprehensive classroom- and home-based programs. The authors reported that many programs were associated with short-term SEL benefits, but that there was a need for additional longitudinal research in this area. Notably, the authors did not explicate their review methodology or inclusion criteria, making it difficult to ascertain the representativeness and comprehensiveness of their findings. This limitation, combined with the publication of a number of studies since 2011, signal the need for an updated review of different intervention strategies for preschool-aged children.

The present paper reviews the most methodologically rigorous research that is available on the relationship between preschool intervention and SEL. We begin by discussing what the construct of SEL is (and is not)—a topic that that has been the subject of some debate and confusion in the literature. Having outlined a conceptual and methodological framework for SEL, we will then describe specific study aims and methods.

Socio-emotional competencies in early childhood

During the early 1990s, the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) attempted to organize decades of empirical research on socio-emotional development into a socio-emotional learning (SEL) framework (Newman & Dusunbury, 2015 ). Since then, the CASEL framework has been widely used by researchers, practitioners, and policymakers alike, informing the development of federal and state state legislation and learning standards.

According to CASEL researchers, SEL is the process of learning to “integrate thinking, feeling, and behaving to achieve important life tasks” (Zins et al., 2007 , p. 194). SEL encompasses children’s emerging abilities to “form close and secure…relationships; experience, regulate, and express emotions in socially and culturally appropriate ways; and explore the environment and learn—all in the context of family, community, and culture” (Yates et al., 2008 , p. 2). CASEL’s SEL framework is grounded in research on typical and atypical socio-emotional development and highlights five core competency areas: (a) self-awareness; (b) self-management; (c) social awareness; (d) relationship skills; and (e) responsible decision-making (Collaborative for Social & Emotional Learning [CASEL], 2012 ; “Core SEL Competencies”, 2019 ; Weissberg et al., 2016 ). These competences are outlined in Table 1 .

Importantly, while CASEL’s five core competency areas are common across most cultures, specific aspects of adaptive SEL functioning may vary based on race/ethnicity, language, socioeconomic status, and other cultural factors. Cognitive, linguistic, and behavioral traits that are considered to be adaptive and desirable in non-majority culture communities may be perceived as problematic or even pathological by majority culture educators (Phillips, 1993 ; West-Olatunji et al., 2008 ). These perceptions may be partially attributed to educators’ own biases, and to disparities between the culture and structure of children’s home and school environments (Boykin, 1983 ; Han & Thomas, 2010 ; Ladson-Billings, 1995 ; McCarthy et al., 2006 ; Webb-Johnson, 2002 ). Thus, when assessing children’s SEL, researchers and educators should carefully consider the role that culture plays in shaping children’s behavior, and avoid conflating cultural behavioral differences with disorder.

Conceptual and measurement issues

Distinguishing sel from executive function.

SEL skills have often been referred to as “non-cognitive” skills in research and practice. Yet many researchers have argued that this designation is a misnomer, given that SEL skills are often grounded in skills related to cognition, learning, and memory. Among the most significant contributors to SEL are executive functioning (EF) skills, which include the cognitive processes necessary for planning, organizing, and problem-solving. Several studies have linked EF deficits to concurrent SEL deficits, and longitudinal work has indicated that EF skills in early childhood predict SEL competence later in life (e.g., Riggs et al., 2006 ). Thus, EF and SEL competencies, (including self-management, as identified by CASEL’s framework) can be conceptualized as distinct but related, and at times overlapping, constructs.

Distinguishing SEL from psychopathology

Psychologists increasingly agree that mental health is most accurately conceptualized on a continuum, ranging from clinically significant psychopathology to psychological wellbeing or flourishing (Keyes, 2002 ). Within this model, mental health or wellbeing is conceptualized not only as the absence of psychopathology symptoms, but as the presence of competencies that enable individuals to withstand adversity and to work towards positive outcomes. As Darling-Churchill and Lippman ( 2016 , p. 3) stated: “Problems and strengths do not fall neatly on a single continuum, and the absence of problems does not guarantee the presence of competencies; thus, it is important to measure both.” From this perspective, it is imperative that researchers and practitioners avoid conflating emergent SEL deficits with psychopathology (Halle & Darling-Churchill, 2016 ).

Children exhibiting emergent SEL deficits may or may not have comorbid psychiatric disorders. Children with diagnosable psychopathology must exhibit symptoms that coalesce into specific patterns and that are associated with significant functional impairment. The latter group would likely benefit from clinical treatment. Meanwhile, many children do not currently meet diagnostic criteria for a disorder, but exhibit emergent deficits in SEL skills relative to same-age peers (Jones et al., 2002 ; Wille et al., 2008 ). A multitude of factors may contribute to lagged SEL, including early deprivation or trauma, inconsistent caregiving, and cultural differences in socio-emotional expression. Children with emergent SEL deficits would likely benefit from broader-based interventions that provide opportunities for them to interact with high-quality caregivers, establish peer relationships, and practice SEL skills in the environments that they are already in (e.g., early care and education settings).

Emergent SEL deficits are distinct from clinical disorder; however, it is important to acknowledge the demonstrated link between early SEL deficits and long-term risk for the development of psychopathology. This link reflects the phenomenon of heterotypic continuity , in which an early behavior predicts the subsequent emergence of a different behavior in the same individual (Rutter et al., 2006 ). The concept of developmental cascades has been invoked as a potential mechanism for heterotypic continuity; in this case, an individual’s early SEL competencies interact with other individual and environmental factors (e.g., genetic, family, school) over time, influencing his or her risk of developing psychopathology (Burke et al., 2005 ). For example, a child who is lagging in SEL may have negative interactions with caregivers and peers and fall behind academically. These experiences may, in turn, increase the child’s probability of academic, psychological, and other difficulties over time. Conversely, a child who exhibits developmentally appropriate SEL will likely experience more social and academic success, which can lay foundations for lifelong wellbeing.

Other measurement issues

As noted above, it is critical that researchers utilize measures that assess children’s SEL skills (as distinguished from EF skills or psychopathology symptoms).

Several additional issues merit consideration when assessing SEL in early childhood (Committee on Developmental Outcomes, 2008 ; Darling-Churchill & Lippman, 2016 ; Halle & Darling-Churchill, 2016 ). Measurement should ideally occur across multiple time-points, as longitudinal assessment allows for stronger inference of causal relationships. Collecting repeated measurements over time will also allow researchers to observe trajectories of socio-emotional development over time. Finally, collecting data from multiple informants is considered ideal in order to gain more comprehensive, reliable pictures of children’s functioning. Integrating reports from different informants, who may perceive children’s behaviors differently or observe different behaviors in different settings (e.g., home versus school), can be challenging; however, several methodological solutions to this problem have been proposed (e.g., Offord et al., 1996 ).

Present review

The present paper reviews the current state of the literature on SEL interventions for preschool-aged children. This review makes several unique contributions. First, whereas previous reviews have primarily focused on skills-based SEL interventions, this review compares and contrasts the effects of three types of early childhood interventions on SEL: (a) general prekindergarten programs; (b) multi-component prekindergarten programs; and (c) skills-based interventions. This review specifically focuses on universal programs in each of the three categories (e.g., programs that are not specifically targeted to children with emergent SEL deficits or psychopathology). Second, whereas several previous reviews have examined the effects of early intervention on child psychopathology (e.g., internalizing, externalizing symptoms), the current review examines SEL outcomes, defined as children’s acquisition of developmentally appropriate social and emotional skills. Finally, rather than reviewing the entire literature, this review focuses on the most methodologically rigorous (e.g., peer-reviewed, longitudinal) extant research. Given these combined foci, the present review offers a thorough, up-to-date overview of the effects of different types of early childhood interventions on young children’s SEL.

Notably, while we believe that it is imperative to evaluate the strength of programs’ evidence bases using specific uniform criteria, our review reveals variable methodology and construct validity across individual studies, making it challenging to assess program efficacy in a reliable or systematic way. As such, we emphasize that the purpose of this review is not to make statements about the efficacy of individual programs, but rather to describe programs that are most promising and to identify knowledge gaps for future research to investigate.

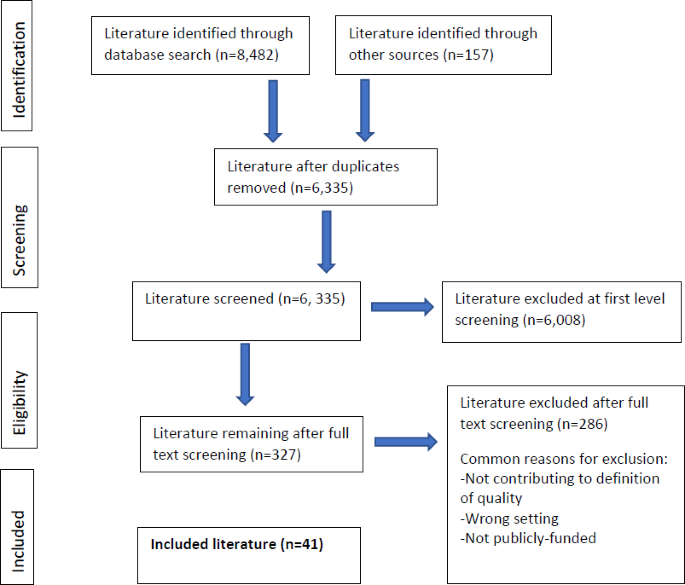

Having reviewed key conceptual and methodological issues, we will now describe our review of universal interventions for preschool-aged children. We conducted searches in Web of Science, PsycInfo, Google Scholar, and PubMed. Numerous search terms were employed, including ones referencing socio-emotional skills (e.g., “socio-emotional”, “emotion regulation”, “non-cognitive”, “prosocial”), early childhood and ECE programming (e.g., “preschool,” “Head Start”), and commonly used SEL measures (e.g., “ Behavior Assessment System ”, “Conners”). Backwards and forward searches were conducted on landmark and highly cited articles.

Studies had to meet six inclusion criteria to be included in the present review. The purpose of these criteria was to identify the most methodologically rigorous studies on modern universal interventions and SEL. (1) studies had to be published in English in peer-reviewed journals by December 31, 2020. (2) Only studies that investigated prekindergarten interventions implemented in 1990 or later were included. (3) Interventions had to be universal (e.g., not specifically targeted to children with baseline SEL deficits or psychopathology) and delivered by laypeople (e.g., not researchers). (4) Critically, given that the focus of the present paper is the relations between intervention and SEL included, studies had to measure one or more SEL skills as previously defined. Studies were not included if they solely measured psychopathology outcomes (e.g., externalizing or internalizing symptoms, problem behaviors) or EF outcomes. (5) Studies had to assess children’s SEL skills at a minimum of two time-points, as skill development over the course of intervention can only be examined within longitudinal research designs. (6) Studies had to include a comparison or control group.

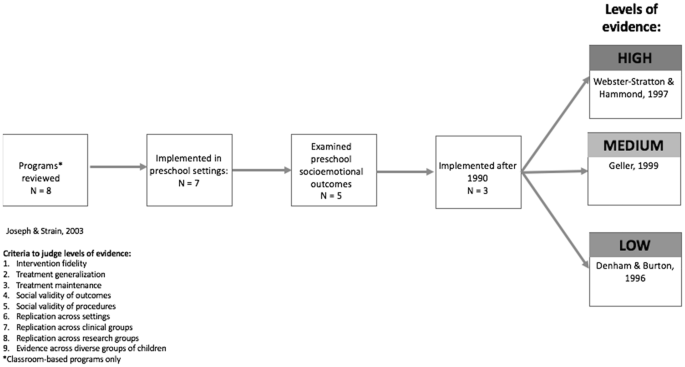

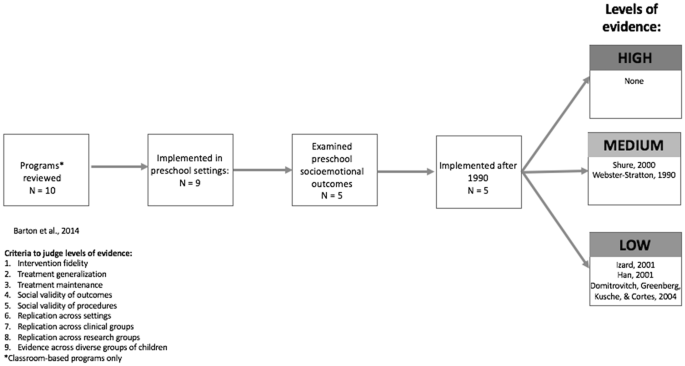

The first and second authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of identified studies to determine whether they met inclusion criteria. During this review process, both authors also determined which intervention category applied to each study. General public prekindergarten programs were defined as publicly funded programs administered by state and local agencies. Multi-component ECE programs were defined as programs which provide multiple academic, family and social support services (e.g., Head Start, the Child–Parent Center (CPC) Program, The High/Scope Perry Preschool Project), typically in center-based settings. Skills-based SEL interventions were defined as discrete interventions aimed at enhancing children’s SEL via direct skills instruction for children and/or their ECE caregivers (e.g., Al’s Pals, The Incredible Years). In cases of disagreement, both authors reviewed and discussed until consensus was reached. Overall, based on these criteria, the following studies are included in the present review: (a) one empirical study of a general public prekindergarten program; (b) three empirical studies of multi-component ECE interventions; (c) 23 empirical studies of skills-based SEL interventions; (d) three systematic reviews or meta-analyses of multi-component ECE interventions; and (e) five systematic reviews or meta-analyses of SEL skills-based interventions. See Tables 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 and 6 for details on these studies, including sample characteristics.

General public prekindergarten and multi-component ECE programs (Tables 2 , 3 , 4 )

General public prekindergarten and multi-component ECE programs (e.g., Head Start, the CPC program) are comprehensive ECE interventions, and stand in contrast to skills-based interventions which primarily target SEL. Nonetheless, there are several important distinctions between general public prekindergarten programs and multi-component ECE programs (e.g., Head Start, the CPC Program). There is often significant variability in general prekindergarten models and populations served, both across and within public school districts in the United States (Phillips et al., 2017 ). Meanwhile, multi-component ECE programs typically incorporate similar program elements and serve comparable populations across sites. Multi-component programs often operate in center-based settings, and typically provide a wider range of support services for children and families than general public prekindergarten programs.

Despite the differences between general public prekindergarten and multi-component ECE programs, we present our findings for both program types simultaneously below. This is because, based on our review and to our knowledge, only one peer-reviewed study (Weiland & Yoshikawa, 2013 ) has examined the effects of general public prekindergarten participation on SEL. A small number of studies have examined the relations between public prekindergarten participation and emotional and behavioral problems in childhood (e.g., internalizing and externalizing symptoms) (e.g., Gormley et al., 2011 ; Magnuson et al., 2007 ); however, as previously discussed, the focus of this review is on the relationship between intervention and SEL, not psychopathology symptoms. The lack of research on SEL in the context of public prekindergarten is a major gap that we will discuss in more depth later in this paper. In the interim, we present our findings on both types of non-SEL-skills-based interventions (general public prekindergarten and multi-component ECE programs).

Meta-analyses and reviews (Table 3 )

Our review did not uncover any peer-reviewed meta-analyses or systematic reviews of the relations between public prekindergarten programming and SEL. On the contrary, several peer-reviewed meta-analyses and systematic reviews have investigated the effects of multi-component ECE programs on SEL. The authors of these publications have typically constructed outcome variables using a combination of measures assessing SEL skills, mental health symptoms, and outcomes from other domains that are related to socio-emotional functioning (e.g., special education placement, criminal justice system involvement). These publications will be briefly reviewed herein.

Nelson et. al. ( 2003 ) published one of the first meta-analyses examining preschool prevention programs for low-income children and families. Inclusion criteria included (1) presence of a prospective research design, (2) control or comparison group, and (3) at least one follow-up assessment in elementary school or beyond. In all, 34 qualifying interventions were identified. The authors reported that preschool programs exerted small to moderate effects on socio-emotional functioning in both the short-term (Kindergarten through eighth grade; d = 0.27) and long-term (high school and beyond; d = 0.33). Age at program entry was not related to program impacts; however, higher program dosage was linked to stronger effects on socio-emotional functioning. Results also indicated that African American children were more likely to participate in the most intensive interventions, and that programs that predominately served the latter group were associated with the greatest socio-emotional benefits.